Introduction: The Flowering of Florence

Each of the four series available on this site offers a number of self-contained lectures devoted to famous Italian ‘narrative cycles’ from the Middle Ages and Renaissance, mostly in the medium of fresco.

Each of the narratives is located in one room or chapel in one specific building which you may have visited already, or may be inspired to visit without delay. Hence, the lectures are grouped geographically around four major cultural centres, identified by the name of their major city. The other three series have the short titles: Rome, Siena and Venice.

This series is called simply: Florence.

The lectures are ordered chronologically and pay close attention to change and evolution (both historical, and ‘art-historical’). But please note that they do not add up to a connected account of Florentine art beween c. 1300 and c. 1450, nor a connected study of political and social developments in those 150 years. My focus remains where it has always been: sharing enjoyment of individual works of art (be they paintings or poems) for their own sake.

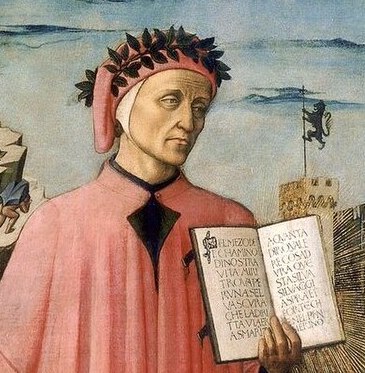

On this site, you are being invited to enjoy stories in pictorial form—stories consisting of multiple scenes. I will not neglect the necessary first stage in that enjoyment; and at the very least, I will ensure that you understand what is happening in the plot. But I am also convinced that aesthetic pleasure is enhanced by a deeper understanding of context and close attention to detail. And this is the point I am making by giving such prominence to a famous detail from a fresco, dated 1465, usually known as Dante and his Book.

The artist shows the exiled poet (dressed as a Florentine), holding open the first page of the Divine Comedy. In the background are scenes from Hell, Purgatory and Heaven. In the foreground—behind the excluding wall—is Florence. (The cit y is defined by its polychrome Duomo (cathedral) and the distinctive tower of Palazzo Vecchio (the seat of government).

Domenico di Michelino was surely right to imply that you need to study Dante’s words closely (not in paraphrase, not in translation), but that you also need to interpret them in the wider context of his love-hate relationship with his ‘native land’, the city that formed him during the ‘first half of Life’s journey’ and then ‘locked him out’ in perpetual banishment: Fiorenza, la mia terra, / che fuor di sé mi serra.

O montanina mia canzon, tu vai:

Forse vedrai Fiorenza, la mia terra,

che fuor di sé mi serra. (Rime, CXVI, 76–78)

The ancient centre of Florence lies on the North bank of the Arno, as you are reminded in these panoramas from different viewpoints on the low hills immediately to the South of the river.

The first is a photograph, dating from 50 years ago. (It was taken from near what is now called the Piazzale Michelangelo.)

The second is a detail from a fresco, dating from nearly 500 years ago, showing Florence under siege in about 1530. (Michelangelo was the engineer in charge of the fortifications.)

The third was painted some 50 years earlier than that, c. 1480, showing the city as it was at the time when Lorenzo de’ Médici was at the height of his power. (He was Michelangelo’s first patron.)

The main point to notice is that, although the modern city has about 500,000 inhabitants, as opposed to about 50,000 in 1480, the appearance of the historic centre remains very much the same—which is perhaps the main reason why we keep going there.

All three panoramas give prominence to Palazzo Vecchio and the Cathedral (which dominate the foreground of Domenico’s fresco) and show the sequence of bridges.

The most important fact to keep in mind is that the major buildings had been under construction 200 years earlier still.

In or about the year 1300 (the fictional date of the Divine Comedy), the population is estimated to have reached 100,000. (In other words, it was twice the size it would be in Lorenzo’s time). And by that year the republic had evolved all the main features of its constitution and laws which were to stay in place with only minor modifications until they were gradually eroded and then destroyed by the Medici.

Great art was produced in Florence in the fifteenth century, as we shall see. But this was the second ‘Flowering of Florence’, the ‘autumnal’ flowering. It sprang from the same stock as had produced the first flowering in the period from about 1250 to 1325—that is, from about fifteen years before the birth of Dante (1265) until a few years after his death (1321).

It would be natural to begin proceedings in this introductory lecture with a purely ‘synchronic’ account of the city-state as it was back in 1250 (i.e. simply describing the ‘state of play’ in the thirteenth century, without trying to explain earlier moves in the game). But there are a number of fruitful tensions even within the commune of Dante’s time, which one cannot understand without grasping the sometimes contradictory myths and values that were inherited from a much earlier past. And this is why I have decided to kick off with a brief ‘diachronic’ survey—a ‘historical’ analysis, if you prefer—in which I shall call attention to elements from the classical and feudal past that persisted, however irrationally, in the medieval republic.

The first phase of Florence’s history runs from its foundation in 59 BC to the fall of the Roman Empire in the West in the year 476. The period may seem incredibly remote, but there are a number of elements in the cultural ‘mix’ which remained the same as they had been in the beginning.

The first of these, and most obvious, is the site.

Florence lies to the south of a major mountain range, at the foot of two routes from Rome to the valley of the Po. It offered a ford or a bridge over a major river running from east to west. It was both a staging post and a crossing point.

The Arno offered good communications both downstream to the sea at Pisa (heavy goods used to go by barge), and, up the valley, towards two passes to the Adriatic coast, and, more importantly, to the headwaters of the river Tiber.

At the foot of the Tiber valley lay the capital of the ancient Empire, which became, later, the ‘capital’ of the medieval Church. (The modern railway lines to Rome—both the high-speed and the slow-speed—still lie close to the natural route dictated by geography).

As well as the site itself, the city retains more or less intact the original street plan of the centre, which was founded as a colonia, a ‘colony’—that is, as a settlement for Roman ex-servicemen. Like all such settlements, it had the standard layout of a military camp, of a castrum.

(The word was normally used in the plural, castra. It is the word preserved in the names of Colchester and Godmanchester, the towns at either end of a military road near Cambridge, which locals still refer to as the ‘Roman Road’.)

The aerial photo clearly reveals the original ground-plan, with the longer axis running due east-west (as it usually did), rather than following the exact line of the river.

A permanent consequence of that original plan are the very narrow streets and high buildings in the modern city.

Pictured here are a typical street (miraculously unclogged by parked cars), as it was in about 1980; and another similar street, as it was five hundred years earlier, in the 1480s. (The detail is from a painting by Filippino Lippi.)

The population was, and is, very dense. To this day, Italians like to live on top of each other. Or, to put it more seriously, Italians were and are convinced that the good life must be lived in a city, a community of at least 15,000 people (as Florence probably had, back in the third century), where there can be diversity of employment and specialisation, and therefore leisure and amenities.

Such a settlement was of course built for defence, and there was no city without a wall.

All these points are conveniently synthesised in this detail of the city, painted in 1352, and labelled Civitas Florentiae.

The image is nowhere near as accurate as the fifteenth-century view on the previous page; but it does vividly convey the idea of the defensive city wall, excluding the outsider (and the exile) and binding together the inhabitants who were squeezed into the densely packed buildings inside.

Notice, in passing, that the building in the foreground which identifies the city as Florence is the octagonal Baptistry, almost exactly the same in appearance as it is today.

(The polychrome façade of the Duomo is shown in the fresco(alongside, as in the modern photo)—but it would take another hundred years for the cathedral to be completed. You may also pick out the sober colours of Palazzo Vecchio and the very prominent Gothic spire of the church of San Pier Maggiore.)

The churches in the centre of the city also go back to the earliest phase. Christianity became the official religion of the Empire in 330, and these churches stand on sites that have been sacred for nearly eighteen hundred years.

There was a continuity of language and customs in the city from those earliest times, but the most important legacies of the Roman period were a myth and a name.

The Florentines were proud that their city had been founded by Romans—significantly unlike other cities in the region, which were founded by earlier peoples (notably, the Etruscans), who preferred to build their towns on the tops of hills (as for example, at Fiesole, just three miles from Florence). For Dante, Florence was, unproblematically, the ‘most famous daughter of Rome’. A century after his death, the early humanists would be arguing only as to whether it had been founded by veterans from the army of Julius Caesar, or by followers of Sulla in the years when Rome was still a republic. Whatever your political sympathies, and whatever meaning you wanted to give to Rome, everyone in Florence was proud of descending from ‘Roman stock’.

Hence, perhaps the most important of the legacies from Rome was the Latin name of the city.

Like the names of other military ‘colonies’ (for example, Piacenza, or Fidenza), Florentia is a feminine noun formed from the present participle of a verb with a meaning of good omen. Florence is the ‘flowering city’, the ‘city of the flower’. Its emblem is the lily; its main coin was stamped with that flower and was called a ‘fiorino, a ‘florin’.

Poets and speech writers constantly played on the etymology. When Dante, writing in the highest Latin style, wanted to say that his native city had banished most of its best citizens (himself included), he began his Epistle with the words: ‘O Florence, having ejected the greater part of your flowers…’.

Hence, the title of this lecture (‘The Flowering of Florence’) reflects something more than a personal weakness for alliteration. ‘By any other name’, the city would not have ‘smelled as sweet’.

After the year 476 came a long period of economic decline, falling population and relative isolation. Italy was invaded successively by Germanic peoples: the Ostrogoths; the Longobards (or ‘Lombards’); and finally, in the eighth century, by the Franks.

They brought their customary law, their personalised hierarchy of ‘vassalage’, their system of holding land and serfs in return for the promise of military service to an overlord—the whole of that complex social and agrarian system which came to be called ‘feudalism’.

By the year 775, Florence was a part of the Frankish marquisate of Tuscany, which had its capital in Lucca.

The marquis (or margrave) held his territories as a fief from the successors of Charlemagne, even though in practice the succession was from father to eldest son.

In 1092, Florence itself became the seat of the marquisate.

At one point, the population of Florence may have sunk to no more than a thousand, and even in the tenth century, when the slow recovery and expansion of Western Europe began, it probably had no more than 2,000–2,500 inhabitants.

One very important permanent legacy was left by these long centuries of feudalism.

The late medieval republic of Dante’s time (with its 100,000 souls) and the Renaissance city (with its 50,000 souls) were dominated by an upper class that had descended from the Germanic invaders.

What you see here is a fifteenth-century imaginary portrait of Farinata degli Uberti, a thirteenth-century representative of this class, who was immortalised by Dante as the very embodiment of the values that were most antagonistic to those of a commune.

Here is the friendly way in which Dante’s Farinata addresses his ‘visitor’ in Hell, whom he has recognised as a fellow Florentine:

Guardommi un poco, e poi, quasi sdegnoso,

mi dimandò: “Chi fuor li maggior tui?”.

Io ch’era d’ubidir disideroso,

non gliel celai, ma tutto gliel’apersi;

ond’ei levò le ciglia un poco in suso;

poi disse: “Fieramente furo avversi

a me e a miei primi e a mia parte,

sì che per due fïate li dispersi”. (Inferno X, 41–48)He looked at me a little, and then, almost contemptuously, he asked me: “Who were your ancestors?”.

And I who was anxious to obey, did not hide it from him, but explained it all; at which he raised his eyebrows a little.

Then he said: “They were fiercely opposed to me and my forbears and my party; so that twice I drove them into exile”.

Men like Farinata considered themselves ‘noble’ or ‘gentle’ (‘gentile’), that is, as being superior by birth to the ‘base born’, the labourers and slaves, the villeins, the ‘vile’. They had an almost ‘caste’-like sense of being set apart, and set above, by their noble blood.

They were essentially fighting men, the officer-class, the ones who fought on horseback, on ‘cavalli’, and who were therefore called ‘cavaliers’ (knights).

Their preferred pastimes were military or para-military—jousting and tournaments, or hunting with hawk and hound—as you can see in these images (both from the fifteenth century), which demonstrate their persistence.

Their immediate loyalties were not to others of their class, however, but to their own family or clan.

The honour of the family was the supreme value. Any insult or injury, real or imagined, had to be ‘avenged’.

The Italian word for ‘vengeance’ is ‘vendetta’; and, as we all know—if only from Shakespeare—vendettas led to family feuds, such as that between Montagues and Capulets in Verona, which persisted over many generations.

Back in the eleventh century, the upper classes still lived on their estates, defending themselves in their remote fortresses or fortified manor houses.

But during the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, they chose—or were compelled—to take up residence in the now expanding cities.

Given the scarcity of land within the walls, they had to be content with towers rather than castles. The sole remaining tower in Florence (in the photograph) was one of about a hundred that used to dominate the skyline.

Today, only San Gimignano, near Siena, looks remotely like how all medieval Tuscan cities used to be.

What the towers in the cities symbolise is that the aristocrats, the ‘gentle men’, remained faithful to the life style of their ancestors—in their idleness, their aggressiveness and class consciousness, and in their code of honour and of physical courage.

They behaved in the city exactly as Shakespeare portrays them in Romeo and Juliet, long after the growth of industry and of European trade, and long after the balance of political power in the state had shifted in favour of the financiers and merchants and even (to a very limited extent), in favour of the artisans in the minor guilds who produced the luxury goods which were the underlying source of prosperity. (In Milan, it had been metalwork and armour; in Florence it was woollen cloth: the most important major guild there was l’Arte della Lana).

More important still, the prestige of the nobility was such that the sons of the newly-powerful burghers wanted to behave exactly like the older upper class.

In Dante’s time (d. 1321), and the time of Boccaccio (d. 1375), the older families and the new sophisticates were still looking to the feudal courts of France for their literary heroes (Arthur, Lancelot, Tristan), for their splendid clothes and heraldic ornaments, for their ideal blonde woman (Guinevere, Isolda), and for their lyric poetry, which we rightly call the poetry of courtly love.

Dante’s poetry sounds quintessentially Italian to our ears, but the themes and implied situations of the lyrics he was writing in the 1280s, no less than their metrical forms and vocabulary, were all derived from the literature of feudal France.

Of course, Dante and his peers would refine and develop the received materials.

For example, the adjective gentile (‘noble’) and the noun donna (from Latin domina, ‘liege-lady’) are among the most common and characteristic words in the lyric genre. But in the octet of his most famous sonnet, Dante is quietly insisting that ‘nobleness’ or ‘gentility’ is inseparable from goodness and virtue; that a ‘lady’ is to be admired for her humility rather than her pride, and that beauty comes from heaven and should direct our thoughts to God, not to the gratification of sensual desire.

Tanto gentile e tanto onesta pare

la donna mia quand’ella altrui saluta,

ch’ogne lingua deven tremando muta,

e li occhi no l’ardiscon di guardare.

Ella si va, sentendosi laudare,

benignamente d’umiltà vestuta;

e par che sia una cosa venuta

da cielo in terra a miracol mostrare (Vita nuova, XXVI = Rime XXII, 1–8)So gentle and so full of goodness does my lady seem in the act of greeting,

that all tongues tremble and fall silent, and eyes dare not look at her.

She goes her way, hearing herself praised, graciously clothed with humility;

and seems a creature come down from heaven to earth to make the miraculous known.

This sonnet is not the least of the ‘flowers’ that Florence produced in the late thirteenth century.

I now want to describe some the main events in the development of Florence as an independent ‘commune’—that is, as an independent city republic—and point out some of the main features of the republican constitution, which reached its classic form in the 1280s and was not abrogated until 1537, when the second Cosimo de’ Medici returned from exile to become Duke of Florence (and, thirty years later, Grand Duke of Tuscany).

You must remember that similar developments were taking place in cities all over the Po valley and Tuscany and that the constitutions were remarkably similar. (I sketch out the constitution of Siena in another series on this site).

You must also remember that, after the Franks in the time of Charlemagne, there was no lasting foreign conquest of Italy and no internal cataclysms. Hence there was no clear-cut break with the political order of the eleventh century.

A ‘commune’ was originally a form of group-vassalage within the feudal system, the distinctive feature being that the fief was granted not to one man (a count or a bishop), but to a group of boni homines—‘good men’ or ‘consuls’—that is, to certain members of the most powerful families in the given city.

As the communes began to grow in size and wealth, they won charters with rights and privileges. This in turn led to their becoming increasingly autonomous and increasingly able to strengthen their economies, until by the middle of the twelfth century, they could (and did) make and enforce their own laws, collect taxes, and defend themselves. Hence—whatever their status de jure might be—de facto it is reasonable to regard them as independent city republics.

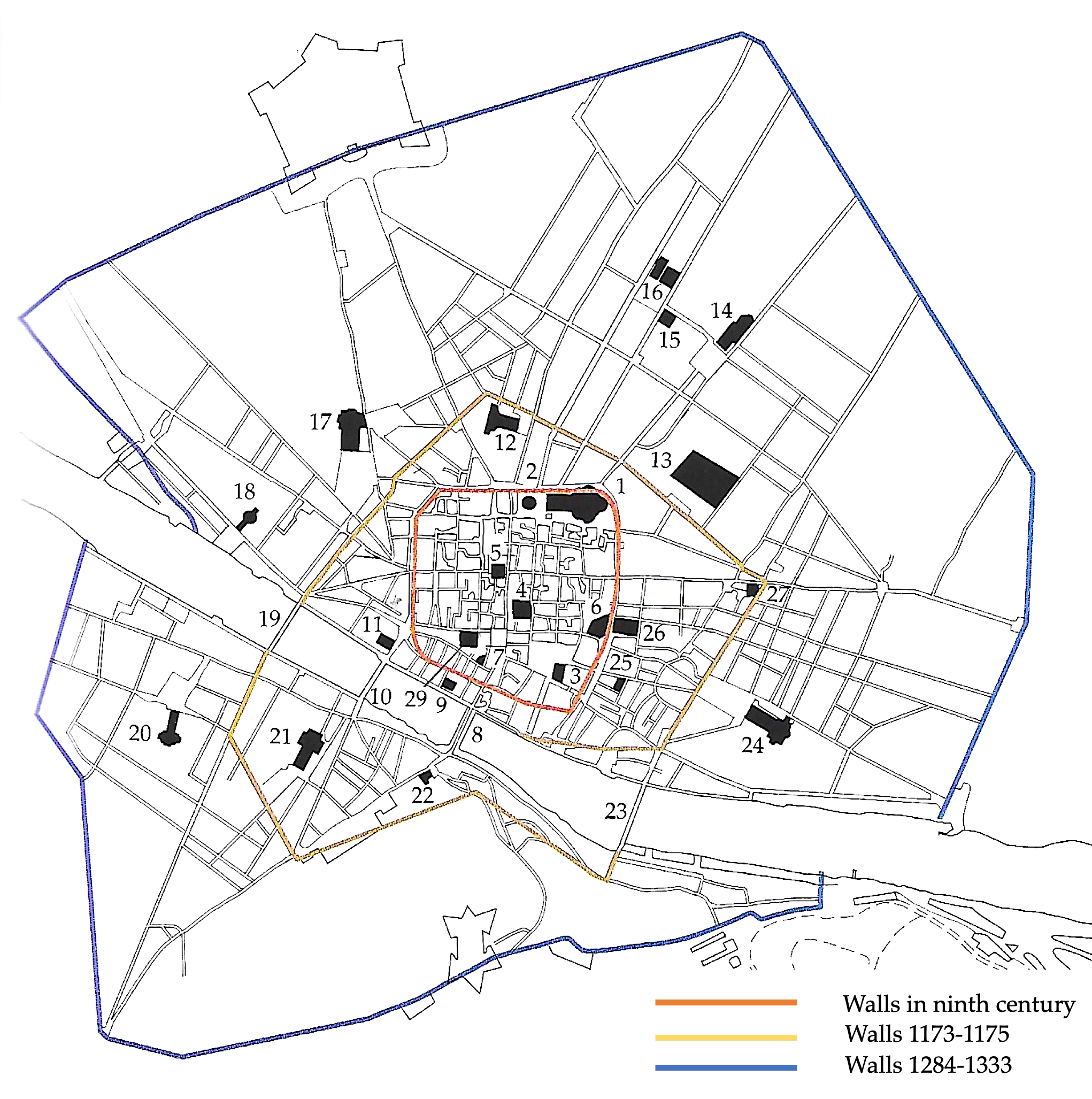

A handful of names, dates and a map may be useful in explaining this slow and uneven transition.

The year 1115 came to be seen as a turning point because of the death of the almost legendary Countess Matelda, who had been the last effective feudal ruler of Tuscany. From that date, Tuscany was virtually free from any lasting military interference; and the individual cities were free to extend their control over the surrounding countryside.

(This area, known as the contado, was where the peasant-farmers lived, the contadini, who supplied the needs of the city-dwellers, the cittadini.)

It was in this context that the republics clashed with the feudal families (as we noted) and compelled them to accept their jurisdiction. And the same process inevitably brought the cities into armed conflict with each other. We know, for example, that Florence defeated Fiesole definitively in 1125, and soon forced all the surrounding townships to become her tributaries.

The rivalry between the city-republics and the increasing concentration of wealth in fewer and larger centres had the desirable consequence—from our point of view—that the cities competed for prestige and status in the size and splendour of their public buildings and principal churches.

If the rich maritime republic of Pisa was the first to build its ‘Field of Miracles’, Siena responded with its two toned cathedral:

The relations between the Italian cities were not only those of individual competition and rivalry.

In the middle years of the twelfth century, a gifted military leader became Holy Roman Emperor as Frederick the First (Frederick Barbarossa, ‘red-beard’) and he tried to assert his ancient rights in Italy, and to collect taxes from his communal vassals.

In the year 1176 (another year beloved of Risorgimento historians), the cities of the North banded together against the German invader and defeated him at the Battle of Legnano (the name may be familiar to you from an opera by the youthful Verdi).

The cities (you see how many there were!) never united again on this scale, but they did of course form alliances among each other—which also means against each other.

In pursuit of these alliances, longer or shorter, they were polarised as they came to align themselves, in the thirteenth century, either with the Holy Roman Emperor (who was for many years, Barbarossa’s grandson, Frederick 2) or with the Pope. They adopted the Italianised names of two much earlier German contenders for the Empire, calling themselves Ghibellines (pro-Emperor), or Guelphs (pro-Pope).

Florence was traditionally Guelph; Siena, Arezzo and Pisa were traditionally Ghibelline.

In the internal politics of all these communes, we find the familiar all-too-human mixture of an occasional willingness to sink individual differences in a common cause and of blindly partisan self-interest.

The internal factions were both a weakness and a strength. A weakness, because constant jockeying would eventually allow the republics to fall into the hands of one dominant family or make them easy prey for the absolute ruler of a nearby state. A strength, because so many people were involved in the exercise of power, and because competition within the commune, between groups and individuals, led to further conspicuous expenditure on buildings, sculpture and painting.

This last point is so important that I would like to call attention briefly to three characteristic results of rivalry within the commune.

When the noble families had settled in the cities, they built first their fortified towers, and later, especially in the fifteenth century, their palazzi. They competed in respect of the height of their tower or the splendour of their palazzo (or the splendour of the frescos in the family chapel in the local church, or the splendour of their funerary monuments in that chapel).

The two photographs show Palazzo Rucellai and Palazzo Medici (Ricciardi) and need no further commentary.

More important, and more sinister, even the families might divide themselves permanently into Ghibellines and Guelphs (or, in Florence, famously, into Black Guelfs and White Guelphs), as they struggled, often violently, for supreme political power in the city.

Dante offers some poignant outbursts against these internal dissensions all over Italy:

Ahi serva Italia,…

…ora in te non stanno sanza guerra

li vivi tuoi, e l’un l’altro si rode

di quei ch’un muro e una fossa serra.

O Alberto tedesco…

Vieni a veder Montecchi e Cappelletti,

Monaldi e Filippeschi,…

color già tristi, e questi con sospetti! (Purgatorio VI, 76, 82–84, 97, 105–08)

Ah Italy enslaved, …your living sons are never free from war, and one gnaws at the other even among those who are bounded by one wall and one moat.

Ah German Albert…come and see the Montagues and Capulets, the Monaldi and Filippeschi,…the first already wretched, and the others living in dread.

The wealthier non-noble families, whose income came not from rents or agricultural produce but from crafts and commerce, sought to protect their interests against the nobles by organising themselves into corporations—guilds, or ‘arti’, as they were called in Italian.

Each guild was like a miniature commune, with its own headquarters, elected head, criteria for admission, constitution, rituals, and procedures for arbitrating between members; and each was able to make provision for helping the widows or orphans of members who died, helping those who had fallen on hard times, or even simply providing a dignified funeral.

(This latter role, however, came to be increasingly assumed by the Confraternities (‘friendly societies’), which were associations of laymen with a religious dimension.

This eloquent detail forms the predella of a small altarpiece from a Flagellant confraternity in Florence.)

The guilds could, and did, band together and act jointly to obtain power on the Councils and priorates in order to curb the power and lawlessness of the nobility, or, later, to regulate the unskilled or less skilled workers, who increasingly came from the countryside and built themselves hovels or houses in the suburbs (borghi) outside the city walls, which would have to be periodically enlarged to enclose them.

This is a good cue to show you a map, illustrating phases in the expansion of Florence in the years up to 1310.

The sixth and final circle of the walls, begun in 1284, was over five miles round, with 73 towers and fifteen gates.

Before the natural, political and economic disasters of the 1330s (including the great flood of 1333, which reduced the population dramatically, even before the coming of the plague in 1348–9, 1360–3 and 1371–4), the population had reached more than 100,000—about half the size of Paris at the time, and twice the size of London.

(After the Black Death of 1348–9, the population fell dramatically by more than 50%, and large areas were returned to nature, or were used as kitchen gardens—as can be clearly seen in the Catena panorama of c. 1480.)

Let us turn now to the commercial activity of the major guilds. (In Florence, the most important were: the Goldsmiths, Silk-weavers, Weavers of Wool (Lana), Apothecaries, and Bankers.)

Like other medieval cities, Florence had always been a centre for many crafts—for all kinds of metal work, leather and parchment, and, later, for sculpture and painting. But by the middle of the thirteenth century, it had become the most important centre in the whole of Italy for the manufacture of high-quality woollen textiles. Unlike Siena (for example), which had no major river, the Arno provided the water and the water power necessary for the many complex operations of fulling and dyeing.

A typical loom (like the one illustrated) required the use of four feet and four hands, making it an ideal occupation for a married couple. So the city became a magnet for vast numbers of weavers.

By the 1320s, there were over 200 workshops, employing a third of the workforce in Florence, feeding about 30,000 mouths, and producing 100,000 rolls of cloth a year.

There were numerous entrepreneurs who organised the many distinct stages of production, ferrying the evolving product round the borghi to each little workshop in turn.

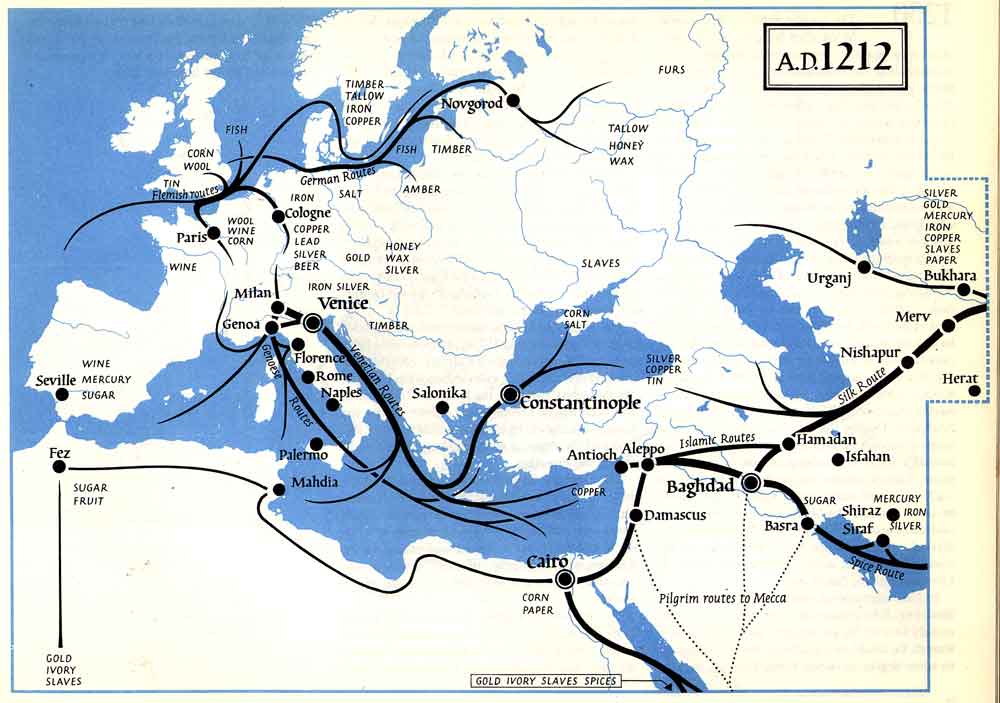

Merchants acquired the very best wool from Flanders and England, and then exported the superb quality cloth all over Europe and the Middle East.

Florentine agents and money-changers followed the pack mules all over this huge trading area, setting up offices and branching out into banking, tax collection, insurance, and even life insurance.

Florence never had a fleet, but it has been calculated that, in Dante’s lifetime, Florentine goods despatched by Florentine companies took up at least half the space in the holds of the ships of Pisa, Genoa and Venice.

With the wealth created by this industry and its spin-offs—there were 80 banks in the early fourteenth century—Florence could afford vocational schools. In 1324, about 1000 boys had been taught to read, of whom about 500 went on to study grammar and rhetoric, thereby creating a reading public for Dante and Boccaccio.

Florence also boasted a studium generale, that is, a minor university. It was a paradise for lawyers, with around 600 notaries practising in the 1320s.

At this time, too, there were 60 doctors, attending 30 hospitals with 1000 beds for the sick and the aged, not to mention a major institution (L’ospedale degli Innocenti) specifically for orphans and trovatelli (‘foundlings’, i.e. illegitimate children who had been abandoned).

Local pride in the city’s achievements was immensely strong.

Back in 1255, a Latin hexameter on the wall of the Palazzo del Bargello (at that time the seat of the chief magistrate, the podestà) celebrated Florence, ‘who possesses the sea, and the earth, and the whole sphere’—‘quae mare, quae terram, quae totum possidet orbem’.

The exiled Dante, expands the line with stinging irony in the terzina which opens canto 26 of his Inferno (c. 1310):

Godi, Fiorenza, poi che se’ sì grande che per mare e per terra batti l’ali, e per lo ’nferno tuo nome si spande!

Literally: ‘Florence, rejoice, since you are so great / that you beat your wings over earth and sea / and your name spreads through Hell!’ More freely—but with the spice of rhyme and assonance: ‘Florence, be glad that you can now command / the sky, the ocean and the land, / and through the Underworld your name resounds!’

But the city had quite a lot to be proud of…

A few words now about the institutions of the commune of Florence as it had become at the height of its first ‘Efflorescence’.

(The sketch is valid, in broad terms, for most of the fourteenth century and for most of fifteenth. But remember that In or around the year 1400, the population had come down to about 45,000 and the citizen class numbered about 6000.)

In its definitive form, the constitution was intended to ensure that no one person, family, or corporation could ever seize absolute power over the city, or even exercise undue influence.

In other words, it was designed to bring about the ‘bene comune’, the ‘common good’ or ‘common weal’—a ‘commonwealth’.

This was why the conduct of affairs was shared among those who were active in producing wealth or doing professional service for the community.

(In the 1290s, members of the nobility were specifically debarred from holding office unless they joined a guild—which is why Dante Alighieri, a minor aristocrat, duly joined the guild of Apothecaries and Painters.)

The republic was headed by a Chancellor, who was appointed for life. (Earlier—in Florence as in other Italian communes—the chief executive, known as the podestà, was a professional magistrate, from another city, who held office for no longer than six months or a year at a time.)

Legislation and policy making was entrusted to three ‘colleges’, known as the three ‘major bodies’. These were: the signoria; the boni homines (twelve men, chosen by lot for three months); and the gonfalonieri (literally, ‘standard-bearers’, sixteen men, chosen by lot for four months).

The day-to-day running of the city was in the hands of civil servants and committees or commissions, answerable to the signoria.

Legislation had to be approved by a two-thirds majority both the ‘Councils’ (which were similar in nature, but had evolved separately for historical reasons). These were: the two-hundred-man ‘Council of the Commune’ (who met in the Sala dei Duecento), and the three-hundred-man ‘Council of the People’.

The ‘signoria’ consisted of nine men, a chairman and eight Priors, chosen by lot (there were two Priors from each of the quarters).

They worked full-time, but for only two months, meeting every day in the Palazzo della signoria. (In Dante’s time, a hundred years earlier, the larger city had been divided into sixths, and the poet himself served for two months as one of twelve Priors).

At least two of the eight Priors had to be members of one of the fourteen minor guilds.

The signoria was assisted and monitored by the two other ‘colleges’—i. e. the boni homines and the gonfalonieri—whose members served for slightly longer. They were selected by lot every three or four months; and in case of the gonfalonieri, provision was made to ensure that every area of the city was evenly represented.

The ‘good men’ and the ‘standard-bearers’ could not initiate legislation, but their assent was required.

The two great Councils (300 and 200) met less often in normal times; but they too had to approve legislation by a two-thirds majority.

In effect, therefore, it was impossible to change anything significant in your two months in power as one of the Priors, unless you could persuade at least 330 of your fellow citizens to agree.

The committees dealt with road works, hospitals, taxation on property, indirect taxation, and the like—the two most influential being those which conducted affairs in time of war (Dieci di balía) and those in charge of security of the state (Otto di guardia).

To serve on a committee, a college or a council, you had to be male, over 30, a guild member, solvent, and not to have held that same office during the previous 3 years.

Approximately 5,000–6,000 citizens had the right status, and of these around 1,650 would be involved in government at any one time. (Sceptical modern historians have noted that, in the crucial committees, the same names, from the biggest guilds and the wealthiest families, tend to recur with great frequency…).

No one was elected and no one (except the Chancellor) was appointed. So, how were citizens summoned to serve?

The answer is ‘by drawing lots’. The names of those eligible (after being scrutinised for validity by two ‘accoppiatori’ appointed by the signoria), were put into a large leather purse, which was always kept up to date for the next ‘scrutiny’ (as they called it); and then the relevant number of names were simply drawn out of the bag.

It was far from being a modern democracy with universal suffrage, but the constitution did ensure that a great many people were involved in running the commune from day to day, and those people had to be ready to serve for short periods at almost any time.

You did not fulfil your duty as a citizen of Florence simply by going along to the polling-station and putting your cross on a ballot paper once every five years in order to delegate the administration to someone else.

One of my favourite lines from John Milton comes in his Samson Agonistes, at the climactic moment when Samson’s father urges a clearly agitated Messenger to deliver the essence of his report without explaining all the details:

‘Tell us the sum, the circumstance defer!’

I fear I may have told you rather more than the ‘sum’ of what you need to know for present purposes.

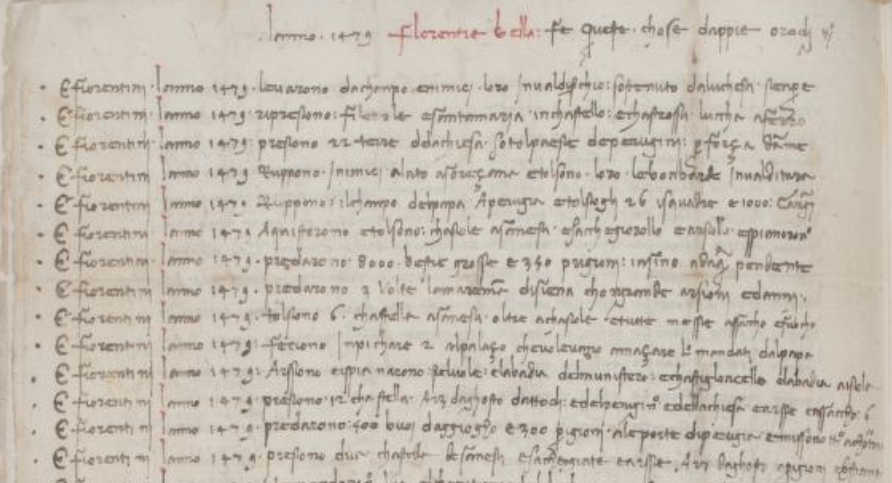

But you will have sensed how difficult it is to stop once you get launched on the subject of Florentine greatness in this period, and how difficult it is to avoid either the rhetoric of Leonardo Bruni’s Encomium (Laudatio florentinae urbis, 1404) or the vernacular enthusiasm expressed in the countless ‘bullet-points’ of Benedetto Dei’s Chronicle (known as La cronica dall’anno 1400 all’anno 1500).

‘Beautiful Florence,’ Dei tells us in the sentences you can glance at here, ‘has 108 richly appointed churches, 23 palazzi, and satisfies all of the seven conditions prerequisite for greatness: viz. political freedom, a large population, a river, subject-cities, a University, Greek and the abacus, every craft in all perfection, and banks and branches all over the world.’

Fiorentia bella…ha drento alla città chiese 108 le qua’ … sono a ordine e ’n punto maravigliosamente con chiostri e … e ’nfermerie e sagrestie e librerie, e campane e campanili, e reliquie e croci, e calici e argenterie assai…

Fiorentia bella ha 23 palazzi drento alla città…

Fiorentia bella ha 7 cose ed è dotata di ciascuna d’esse, e non si può chiamare perfetta chi no l’ha tutte e sette.

Prima ell’ha libertà intera; seconda ell’ha gran numero di popolo e ricco e ben vestito; la terza ell’ha fiumara pel mezzo; la quarta ell’ha signoria di città e di castella e di terre e di popoli e comuni; la quinta ell’ha lo Studio e ’l greco e l’abaco; e la sesta ogni arte intera e ’n perfezione, la settima e ultima ell’ha banchi e ragioni per tutto el mondo.

I hope I have not caused confusion by abandoning my guiding principle of subordinating every line in my text to an image and by dwelling so long on Dante and the Middle Ages (even though most of the lectures in this series are dedicated to narratives from the period 1425 to 1475).

There are factors to plead in mitigation.

My head is packed with too much ‘circumstance’.

Cumulatively, I have been privileged to live in the heart of Florence for at least 30 months (adding together all the study trips between 1963 and 2015; having first glimpsed the city as a hitch-hiking student in 1955). I have been invited to lecture on Dante in the Palagio dell’arte della Lana and in both the Sala dei Duecento and the Salone dei Cinquecento.

So many memories come crowding in—not least of the day in 1995 when I marched in a solemn procession to the sound of trumpets through the streets from La casa di Dante to Palazzo vecchio, there to receive a Gold Medal. (Notice the lily and the inscription.)

However, I think I can restore the balance and bring this lecture to a satisfying conclusion by offering a close commentary on one final image, which will function both as revision and as an appetiser.

FIXME: IF I STAY WITH THIS CONCLUSION, AND IF I FIND A REASONABLE PHOTO FROM JUNE 1995, WE’LL INSERT THE PHOTO OF ME IN PROCESSION, PROMINENTLY, AT BOTTOM OF THIS PAGE

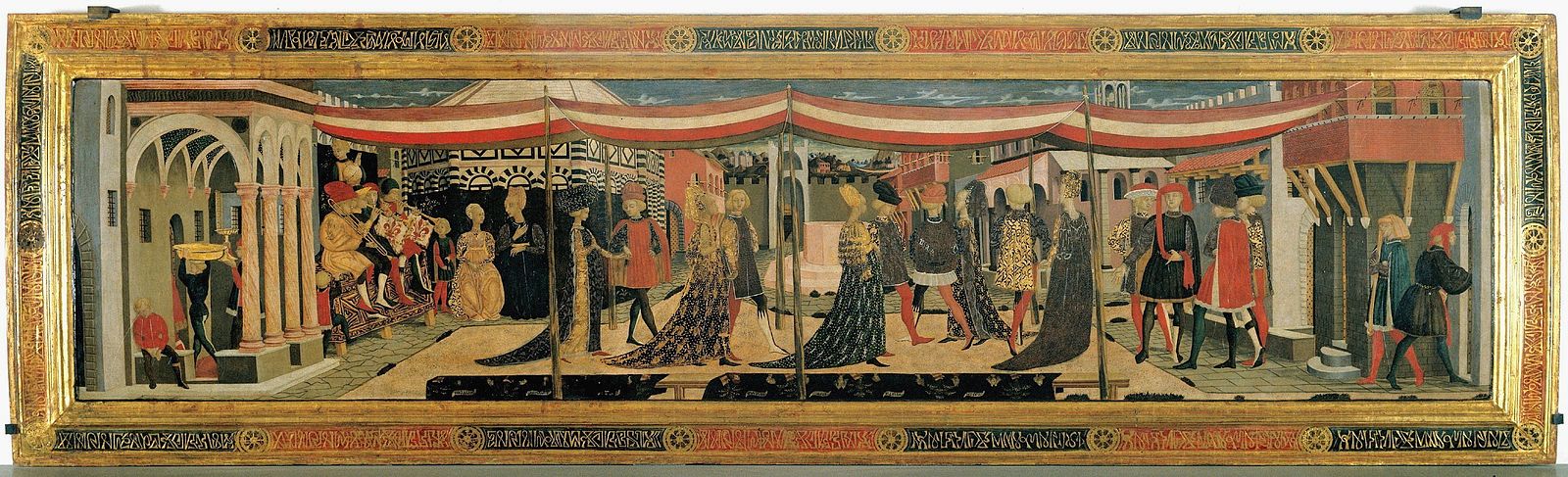

This cheerful spalliera (about three feet wide) is now attributed to Masaccio’s younger brother, Giovanni. It dates from about 1450. The perspective is right up to date (single vanishing point), but the effect is still rather naīve—almost the same as it might have been in a painting with empirical perspective from 1400, or even 1350.

The bright colours testify to the enduring influence of courtly art from north of the Alps (as will be evident in Benozzo Gozzoli’s frescos for the Palazzo Medici).

Florence is identified not by its cathedral or seat of government (as it was in Domenico di Michelino), but by the polychrome Baptistry (for which Lorenzo Ghiberti had just moulded the bronze reliefs on the Gates of Paradise).

The scene is a kind of street party taking place under a canopy erected for the occasion. The central street is recognisable as the modern Via de’ Calzaioli. The realistically cantilevered balconies and the windows are of the kind often represented in the backgrounds to sacred art in this period by (we shall see examples in Masaccio and Domenico Veneziano).

The five aristocratic couples are taking part in a stately dance (‘with steps solemn and slow’), at a Wedding Feast of the Adimari family, who are proclaiming their status and wealth. The men are elegant and neat in their tabards and coloured hose, each with a hat of different design. But the five women are dressed to kill with the most elaborate coiffures and headgear, wearing the most expensive of embroidered gowns with long trains.

Musicians play wind instruments: a recorder (half hidden); a sackbut (requiring a lot of puff); and two shawns (adorned, as they were for me, with Guelph flags). The dishes being carried back indoors are of pure gold.

This is the kind of treat that lies in store for you.