Giotto: St Francis

The fresco cycle at the heart of this lecture is one of the most extensive and most important in the whole of Italy. It is also one of the most familiar. We all know something about St Francis of Assisi, and we all know that Giotto’s Life of St Francis constitutes a turning point in the history of Italian Art.

Or do we?

Until about the middle of the last century, the cycle was one of the least well understood; and traditional misperceptions and misrepresentations are still repeated from one guidebook to the next. Indeed, the mixture of truths and half truths is sometimes so hard to disentangle that at one point I thought it would be necessary to offer at least three preliminary lectures to clear away the cobwebs.

One ought to be acquainted with: (a) the historical figure of St Francis of Assisi (1184–1226) and the historical context of the astonishingly rapid diffusion of his Order of Friars Minor in the first sixty years after his early death; (b) the no less astonishing technical advances in Italian painting towards the end of the thirteenth century; and (c) the problems of attribution in the particular case of the narrative cycle in the Upper Church at Assisi. (Several workshops were clearly involved, and there is no documentary evidence of the participation of Giotto, who would have been only in his mid-twenties in the crucial years.)

Finally (d), one ought to be aware at least of the existence of a later cycle of frescos, which are certainly by Giotto and his team, and are to be found in the church of Santa Croce in Florence.

Rising to the challenge, undeterred, I have tried to compress this superabundant material into a single lecture, divided into three distinct parts.

In the long central section, I shall allow the anonymous ‘Assisi Masters’ to narrate in visual form the main events in Francis’s life, as these had been selected and presented in the ‘official biography’ of Francis by St Bonaventure. (The Franciscan theologian became General of the Order of Friars Minor. His Legenda maior was compiled in the 1260s and was intended to correct and replace all earlier witnesses.)

In the final section, I shall introduce—briefly and more analytically—the seven episodes in the Santa Croce cycle (dating from 1325–1330, and universally accepted as work by Giotto), comparing and contrasting them with the corresponding scenes in the Assisi cycle (painted in the 1290s).

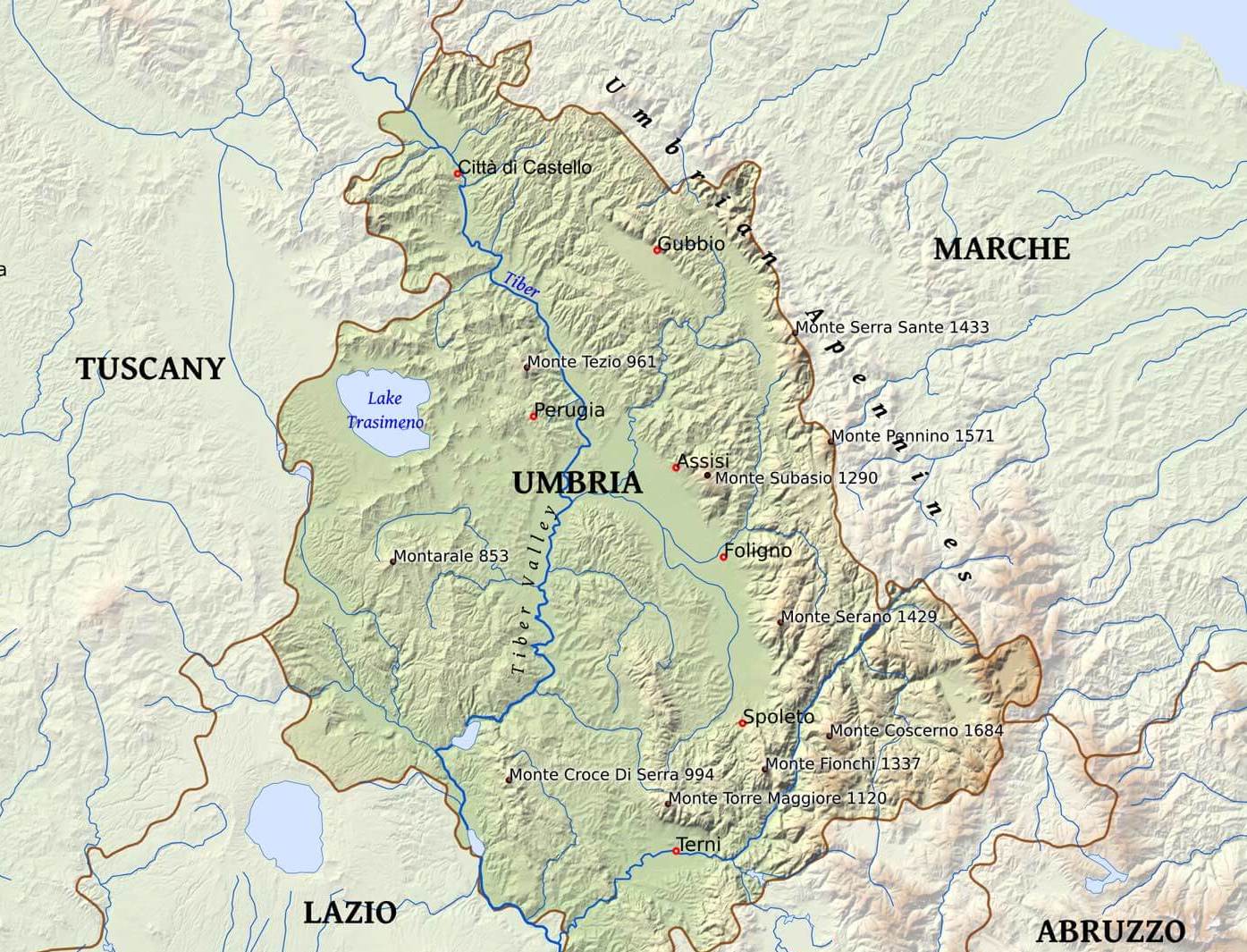

And I am going to begin by giving my own account of the early history of the Franciscan Order—properly called the ‘Lesser Brothers’—and their rapid ‘colonisation’ of Central Italy in the middle years of the thirteenth century.

This opening section will be illustrated by images of Francis painted in those early years which will give you some idea of what provincial painting was like in the period before the huge technical and expressive advances made by artists at the end of the century.

In the first, introductory lecture of this series—The Flowering of Florence—I was careful to present the ‘City of the Flower’ in both its positive and negative aspects; and I stressed that these had produced a ‘love-hate’ relationship in Dante, who described himself metaphorically as one of the ‘flowers’ who had been ‘cast out of her bosom’ (by banishment, in the year 1300).

In the Divine Comedy, the poet returned again and again to his feelings for his native city, either speaking in his own voice or putting words into the mouth of one of the souls whom he met in the journey through the three realms of the afterlife.

In the most extended and poignant of these fictional encounters (in the central cantos of Paradiso) he allowed his remote ancestor, Cacciaguida, to evoke the myth of the good old days (‘il buon tempo antico’), when the city had lived ‘in peace, soberly and chastely’, within the ‘ancient circle’ of its twelfth-century wall (Paradiso, 15, 97–99). The population of the city in 1300, he asserted, was five times as big as it had been (16, 48); and—by implication—was living ‘lewdly, drunkenly, and in discord’.

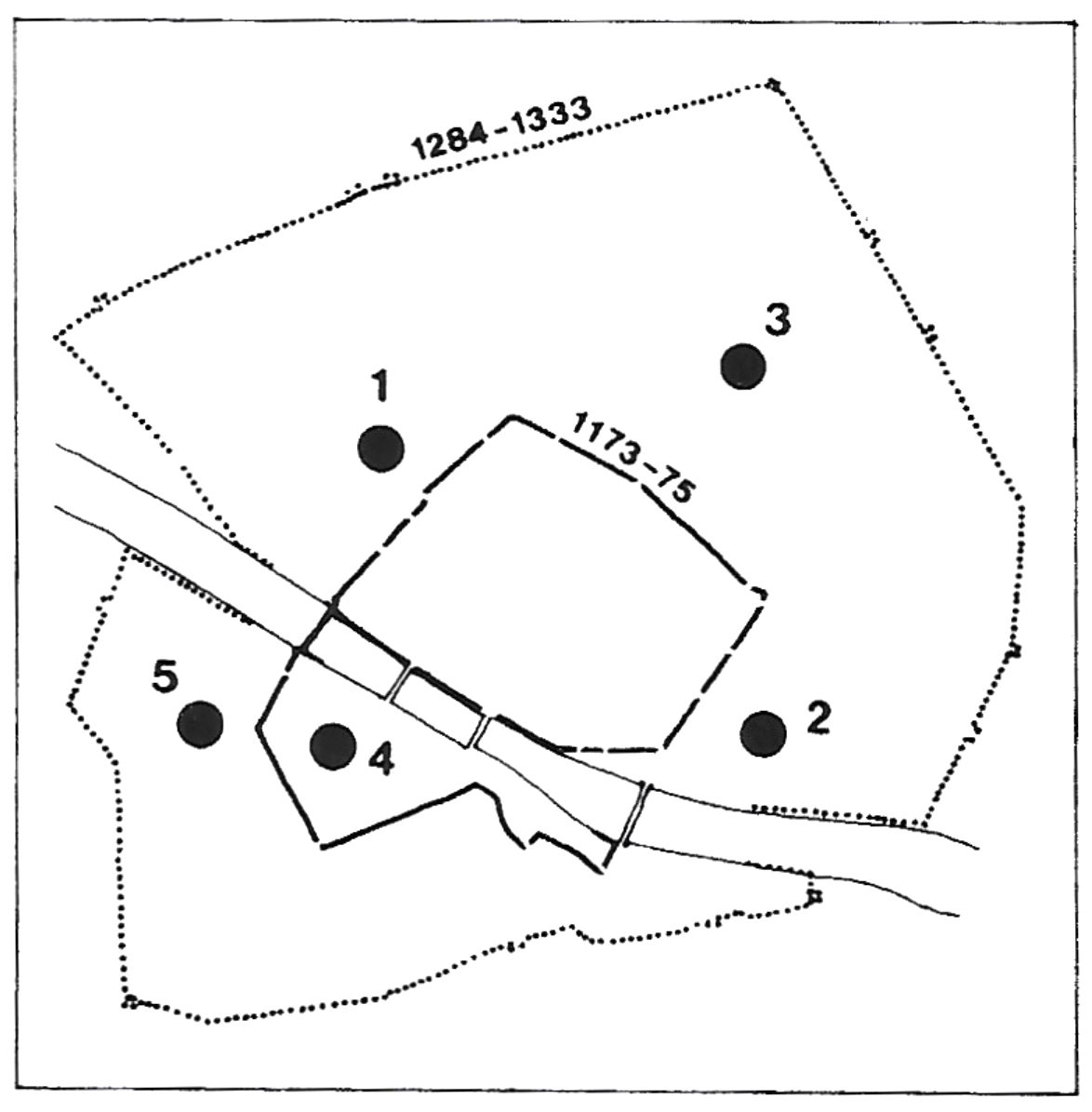

(This simple diagram of the two ‘circles’ of the city walls—in about 1180 and 1320—tells you almost everything you need to know about the huge expansion.)

Much earlier in the Comedy, the character Dante had pronounced a famous, one-line diagnosis of the linked causes, viz.: ‘the new people and the sudden profits’ (‘la gente nuova e i súbiti guadagni’, Inferno 16, 73).

In modern terminology, he was attributing the city’s wealth and and its moral turpitude to a prolonged economic boom sustained by mass immigration from the surrounding countryside. (What he does not say, of course, is that this phase in the history of Florence was simply the most dramatic example of a process taking place all over Western Europe.)

Rapid urbanisation brought problems of all kinds, including purely spiritual ones. The uprooted ‘new people’ (in Florence, as elsewhere) found little nourishment in the established church; and they turned to other forms of religious belief and practice: either non-Christian or involving distortions of Christian teaching which the Church has branded as ‘heresies’.

At the beginning of the thirteenth century, the official church reacted vigorously to these challenges: either, with force, as for example in the so-called Albigensian Crusade in Southern France; or by a more effective teaching of the true faith to the new communities and by involvement in their daily life.

Four new religious orders were founded in the early years of the thirteenth century, and the existing Augustinians were revitalised.

The diagram of the walls is repeated here to show how the new orders came to Florence and where they built their huge new churches in the enclosed suburbs. These belonged to the Augustinians, the Servites (or Servants of Mary), the Carmelites, the Order of Preachers (Dominicans), and the ‘Lesser Brothers’ or Frati Minori (Franciscans).

The two saints were very different in personality, but the Church has always been at pains to insist that they were not antagonistic but complementary—the one more cherub-like, and the other more seraph-like. (Dante was fundamentally faithful to tradition in his carefully linked presentation of the two in cantos 12 and 13 of Paradiso).

Dominic was the intellectual, the preacher.

Francis was the man who tried to live as Jesus had told his disciples to live, the man who called the sun his brother and the moon his sister—the man who preached to the birds.

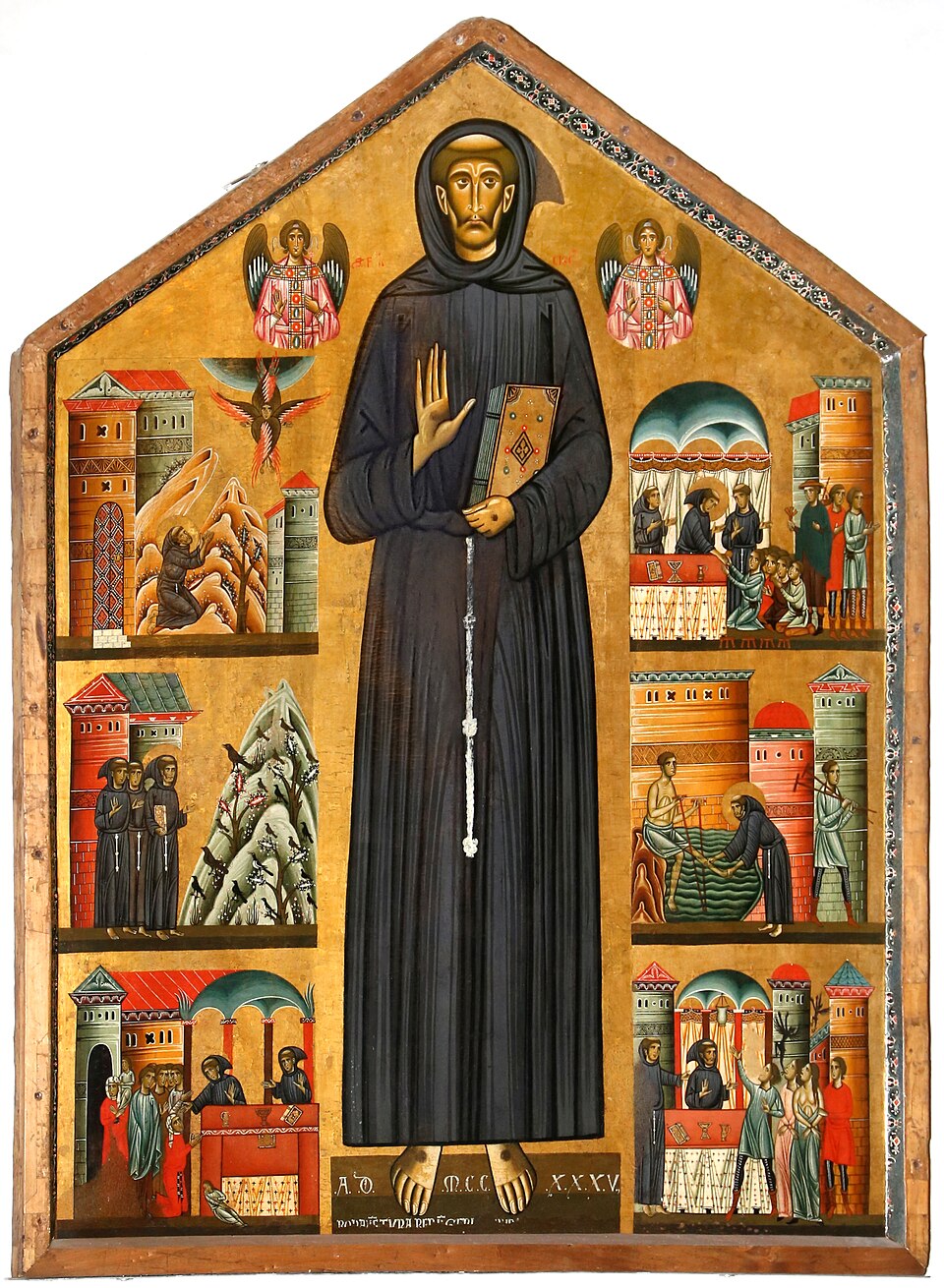

This wonderful early altarpiece dates from 1235, less than ten years after the death of the Saint. (It is the earliest painting of Francis by a Florentine artist.)

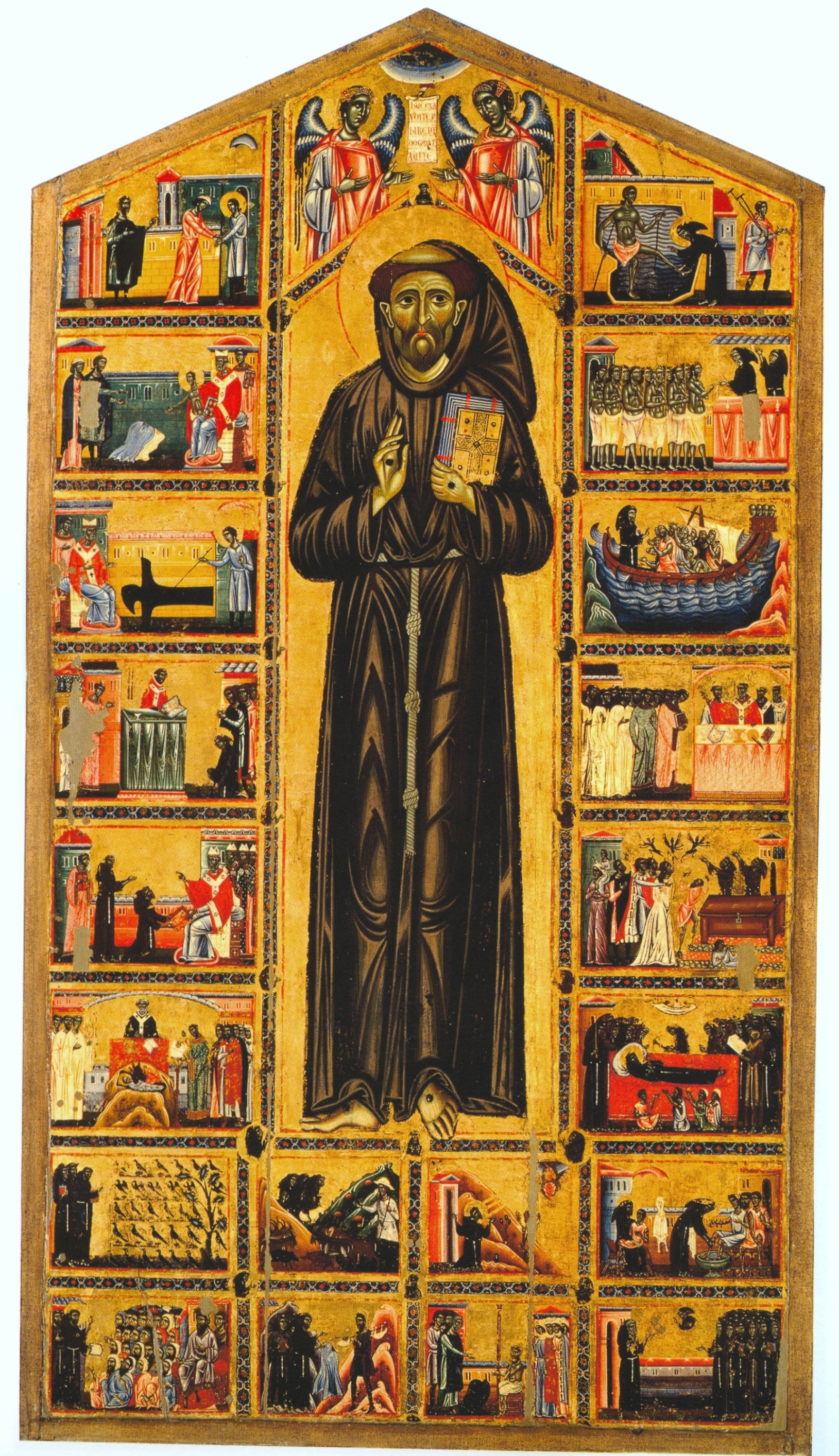

This is a similar altarpiece (known as the Bardi Dossal), dating from perhaps 30 years later, which was commissioned for the church of Santa Croce in Florence itself, where it still is.

Once again, but on a slightly bigger scale (about seven feet by three), you see a central image of the saint, visible to a congregation of moderate size, with smaller narrative panels alongside, visible only to the celebrant.

Please compare the scene of the Preaching to the Birds with that on the Pescia altarpiece—and enjoy both of them. There could hardly be better examples of the state of painting in central Italy in the middle of the thirteenth century. Nor does any later representation capture so faithfully the simplicity and directness of the saint’s own Cantica or the so-called Fioretti (the earliest narratives, written in Italian).

In the same spirit, let us look a little more analytically at another panel from the same Dossal.

It shows Francis, appearing miraculously in answer to a prayer from sailors on a stormy crossing of the Adriatic to save them from shipwreck.

Notice the gold ground and the saturated colours; the extreme stylisation of the pink and green rocks and the agitated blue waves of the sea; the lack of any depth in the picture; the absence of a common scale for ship and crew; the faces of the big-eyed suppliants, all in three-quarter-profile; and the four dark heads in the foc’sle.

All these features provide a perfect foil for the frescos in the Upper Church at Assisi.

We now begin to enter that grey area where ‘storia’ meaning ‘history’ shades into ‘storia’ meaning ‘story, myth, or fiction’.

The reasons why the ‘History of Francis’ we shall find in Assisi look so different from the ‘Stories of Francis’ you have just enjoyed are connected with developments in the art of painting, but they also have a great deal to do with the battle between the ‘left’ and ‘right’ wings of the Franciscan Order in the middle of the thirteenth century.

There is clearly no time here to go down either of these ‘main roads’; and I think the best ‘short cut’ to our subject will lie in the recognition that there had always been a very important tension (reflected in the visual arts) in the history of the Franciscan order, which goes right back to the personality of Francis himself.

It is the tension between the holy innocent, who gave both a new stimulus and a new focus to popular devotion by imitating Christ’s actions and observing his injunctions to the letter, and, on the other hand, the organiser, the leader, the man who founded a new Order with its own rule, an Order, rapidly approved by the Pope, which had spread all over the North of Italy by the time of his early death at the age of 44—the man who was so acceptable to the Establishment that he was canonised in 1228, only two years after his death.

The first Francis is the one who was recorded in the writings of those who knew him personally, like Thomas of Celano. In these writings the treatment is timeless and episodic, the message challenging, even subversive; and I am not alone in feeling that the Francis they present is caught to perfection in the more ‘primitive’ narrative panels, like those we have just seen, dating from close to his lifetime.

However, there was that other Francis, the one who wanted to be accepted by the established Church, and who founded an Order with a Rule.

Francis’s followers were soon divided into a more radical wing, who came to be called ‘spirituals’ and insisted on the literal interpretation of evangelical poverty, and the more middle-of-the-road ‘conventuals’, to whom, obviously, we owe the splendid monuments of Franciscan art and architecture.

The dispute came to a head in the 1260s, when the outstanding General of the order, St Bonaventure, wrote a new official life of the saint, laying great stress on Francis’s submission to the Pope, and demanded that all surviving copies of the earlier lives should be withdrawn and destroyed.

This command affected the iconography of the saint as well. It has been argued, for example that the Bardi Dossal in Santa Croce must have been painted before 1265, simply because some of the scenes are not to be found in Bonaventure. Whatever the exact date of the Dossal may be, however, pictorial representations after the 1270s are clearly based on Bonaventure’s official biography, and they show a Francis who is acceptable to the pope in Rome.

We have come to Assisi in order to study the Life of St Francis as it is narrated in an exceptionally long sequence of frescos in the most important church in his home town. It is the mother church of the Order of Lesser Brothers.

I say ‘church’, but ought to say ‘churches’ in the plural—for there are three of them, one on top of the other.

At the bottom of the stack is the crypt where the saint was buried in 1226.

Over this his followers built a relatively simple church in the local, provincial style.

But this soon proved to be too small for the countless pilgrims who came to visit the tomb; and a much grander church, in the up-to-date French Gothic style, was erected on top of the first (by the year 1260).

This Upper Church has a huge, undivided nave of about 800 square yards, and is thus able to hold about 2000 pilgrims who could all be instructed simultaneously through sermons and paintings.

It is important to know that this is a so-called papal church, to which the pope has the right of direct access and in which the altar is actually placed at the West end (as it is, for example, in St Peter’s in Rome, and in the Sistine Chapel).

It was the first Franciscan Pope (Nicholas IV, 1288–92) who energetically masterminded the extensive decoration of the Upper Church.

The funds came from Rome; and so too did the major artists, bringing with them a new, monumental, massive and realistic style, quite unlike what you have seen so far in the early altarpieces.

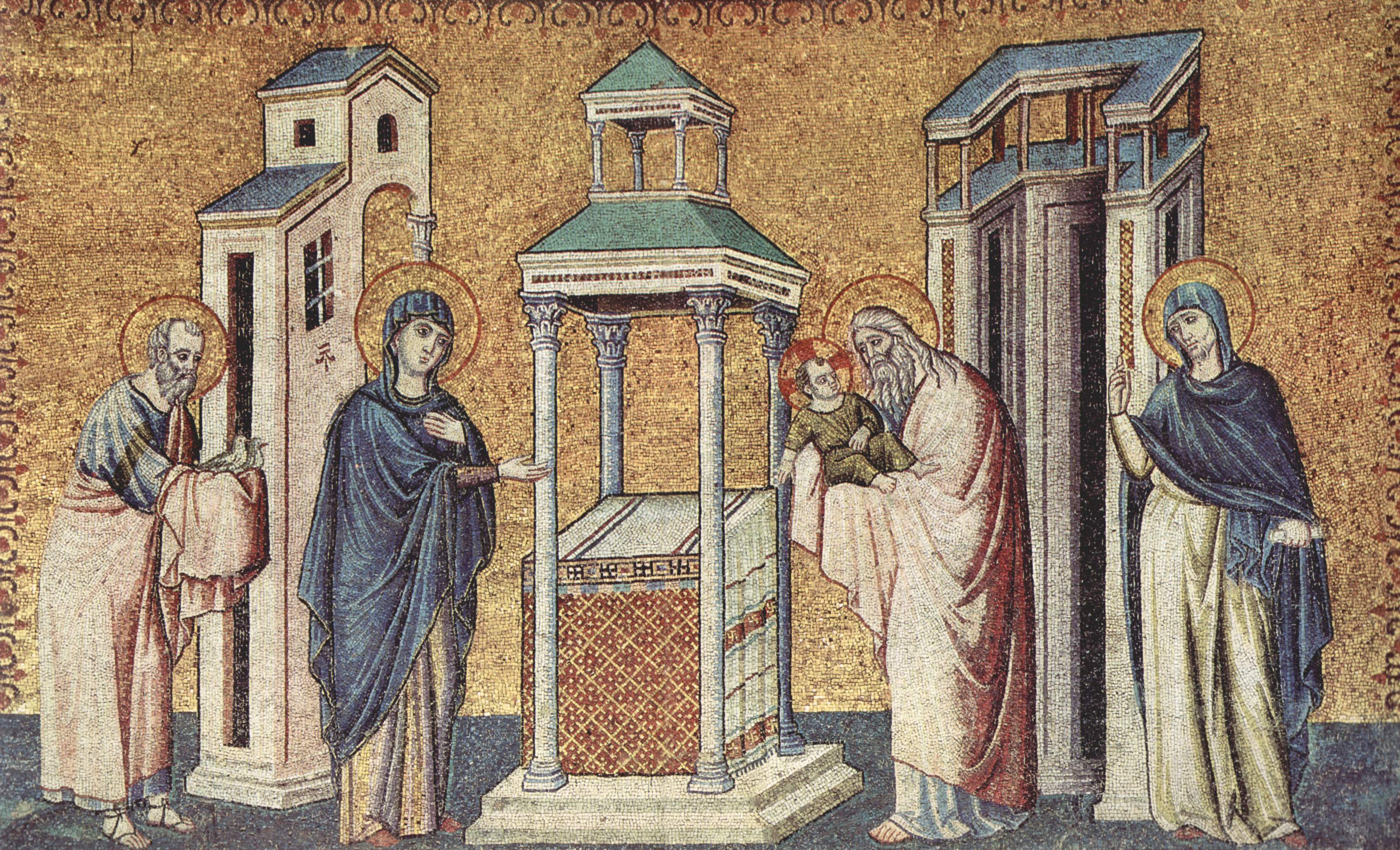

It was a style much influenced by Byzantine mosaics found in Sicily and Southern Italy, and also by French Gothic sculpture, exemplified here in a work by one of the greatest Italian sculptors of the age, Arnolfo di Cambio. (The statue is of St. Peter, the very symbol of papal authority.)

Back to Assisi.

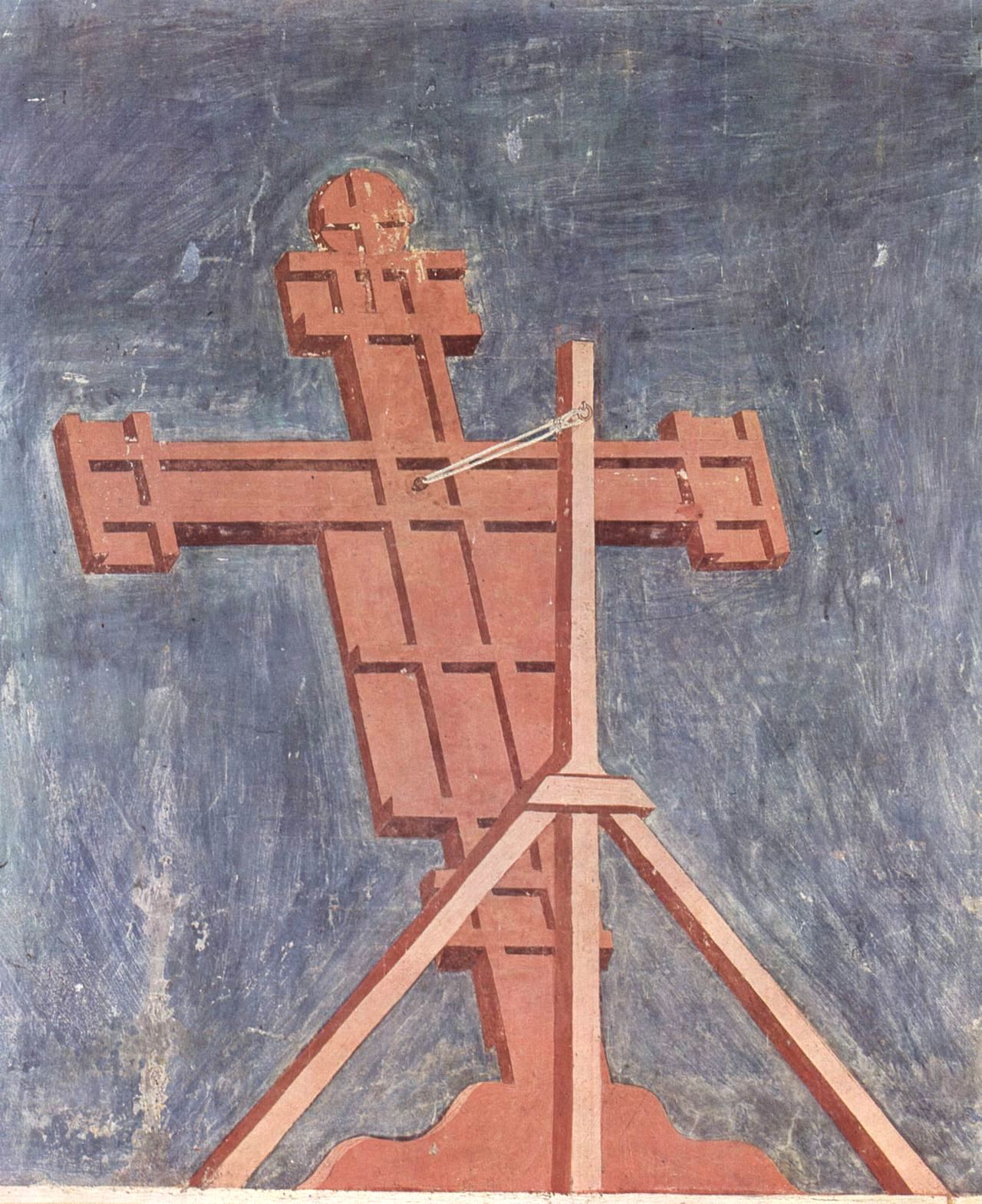

The crossing of the Upper Church had been frescoed in the 1280s by the Florentine Cimabue, who had every reason to believe, in Dante’s much-quoted phrase, that he ‘held the field in painting’, as witness the great wooden Crucifix he painted for Santa Croce in Florence.

(Alas, the Fates have been not kind to Cimabue. His crucifix was almost ruined by the great flood of 1966 and the Assisi frescos have degraded chemically.)

The spaces surrounding the windows in the nave are filled with carefully organised scenes from the Old and New Testaments.

The space below the windows had presumably been reserved from the outset (i.e.from the time of the building of the Church, back in 1260) to carry the story of the life and the afterlife of St. Francis.

At this point, we must pause to consider the ‘much ventilated question’ (vexata quaestio) of the ‘authorship’ of the narrative cycle.

Italian guidebooks still imply that the Francis Cycle was the first major contract awarded to Giotto—the rising artist from Florence, who was Dante’s exact contemporary (hence only about twenty-five years old at the time when the contract would have been signed). On this view, it would have been the Assisi frescos that made him famous all over Northern Italy by the date of their completion.(In his poem, Dante specifically says that by 1300—the fictional date of his fictional journey—Giotto’s name is on everyone’s lips (‘or’ ha Giotto il grido’), eclipsing the fame of Cimabue. The first documented work by Giotto is in the Arena Chapel in Padua, dated 1303–5).

Italian art historians (as opposed to the authors of tourist guides) seem to incline to the view that there were at least three or four workshops employed, one of which was headed by Giotto. By the 1970s, however (when I was first initiated into these mysteries), many English art historians, led by John White and Alastair Smart, had come to doubt that Giotto had any part at all in the decoration of the Upper Church.

It would be absurd for an amateur to express any personal opinions about such complex problems in an introductory lecture. So, having issued a sort of health warning—‘Be on your guard’—let us move to the frescos themselves.

(You are simply asked to keep in mind that every one agrees that the frescos offer the single most influential ‘Storia di San Francesco’ ever painted, that they are an indispensable document for the understanding of popular religion and papal politics in central Italy in the late thirteenth century, and that the numerous Tuscan and Roman artists involved made a fundamental contribution to developments in the art of painting that later became permanently associated with the name of Giotto. When we have looked closely at how the story of St Francis is told in Assisi, we shall compare seven of the scenes with their counterparts in the Bardi chapel in Santa Croce, in Florence, which certainly were painted by Giotto and his team towards the end of his life, when the artist would have been in his late fifties or early sixties (c. 1325–1330).)

The narrative in the Assisi cycle begins nearest the altar on the right-hand wall, unfolds down the length of that wall, crosses the entry wall, and returns all the way back to the altar.

Each fresco is about nine feet high and seven and a half feet wide.

The bottom is set about eight feet from the floor—which ensures that the scene is low enough to be seen clearly, but high enough to be visible even when the church is packed.

The painting and the architecture are marvellously fused.

All the real columns and vaultings in the nave are ‘flattened’, so to speak, by the use of one unified colour scheme; whereas the flat surfaces of the plaster are painted in such a way as to suggest a third dimension.

The artist has simulated tapestry below each scene in the narrative, and he has simulated spiralling columns on both sides of each fresco.

While, at the top and bottom, there are simulated beam ends or ‘soffits’, which are painted in perspective as if they were seen from a single viewpoint in the centre of the given bay, in order to suggest that the painting is actually set into the wall.

Having spent rather long on the various contexts, I am now going to take you rather rapidly through the first two thirds of the Assisi cycle, concentrating on the story-line and limiting myself as far as the narrative is concerned, to the words of St Bonaventure.

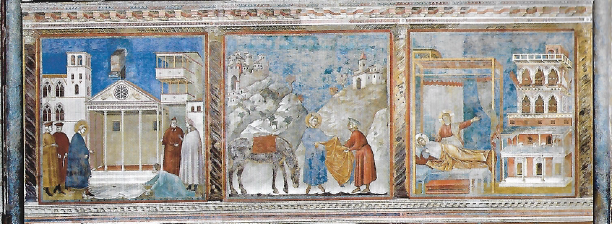

The three scenes in the first bay form a typical prelude.

In the first, which is set in the town square of Assisi, we are shown:

‘a simple man who, whenever he chanced to meet the young Francis, used to take off his cloak and spread it under his feet, saying that Francis deserved every sign of respect, since he was destined to do great things in the near future’.

(It has been established that this was the last of the 28 scenes to be painted; and specialists have identified the hand as that of the the ‘Saint Cecilia Master’.)

Apart from the absolute clarity of the storytelling—perfectly exemplified in the gesture of the poor man in the detail, with his spread arms and jutting chin—the fresco is chiefly remarkable for its representation of the buildings.

As we go through the cycle, we shall see a great many pieces of of tall, narrow, ‘stage architecture’, like the balconies on the right here. But the buildings in the centre and to the left, are among the earliest convincing examples in the history of Western Art of an attempt to represent the appearance of real buildings, and, moreover, the very buildings in front of which the episode took place.

The photograph shows what is now called the ‘Piazza del Comune’ in Assisi.

You see a tall tower which is the dominant feature of a three-storied palazzo, typical of the Italian communes, standing next to a church, which is built behind the façade of a first-century BC pagan temple, originally dedicated to Minerva.

Some things in the fresco do not ‘look right’. The top storey of the tower in the photo was added after the time of the painting; and the artist has instinctively ‘medievalised’ the proportions of the classical tympanum. He also has also reduced the number of columns from six to five, and made them much more slender than they are in reality. But the fluting and capitals are faithfully rendered; and there can be absolutely no doubt that this scene is set in the centre of Assisi, a few hundred yards away from the Upper Church itself.

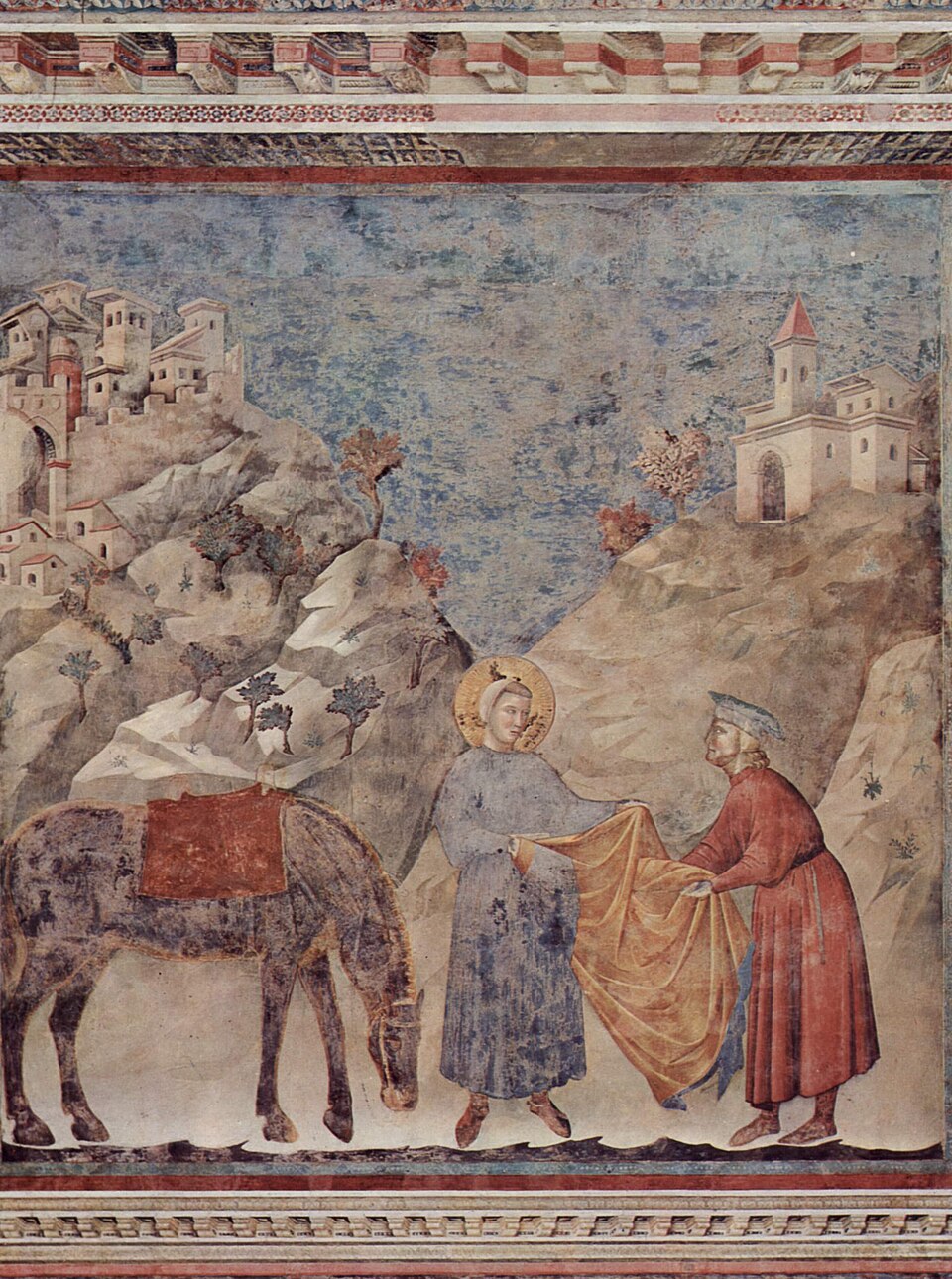

In the second scene, we are shown Francis after he has recovered from an illness.

‘Dressed in his usual fine clothes, he met a certain knight who was of noble birth, but poor and badly clothed.

Moved to compassion for his poverty, Francis took off his own garments and clothed the man on the spot’.

It is clear from the figure style, and above all from the architecture of the buildings on the hills, that the painter is not the same St Cecilia Master of the first scene.

He is, however, the artist mainly responsible for the rest of this wall, and it is he, if anyone, who is to be identified with the young Giotto.

In the intention of the artist, the landscape and buildings are no less identifiable than the ones in the first scene.

The walled town on the left is clearly meant to be Assisi, on the brow of its main hill; and the isolated, towered church is intended to represent (anachronistically), the very Upper Church where the fresco is. (You must mentally flip the photograph to see the likeness.)

However, the landscape and buildings are less important as a topographical record than as elements in the composition, which, in turn, is used to enhance the significance of the story.

You will register how the large V made by the two hills focuses attention on the saint’s head, and how the downward sweep of the hill from the town reinforces his gesture of giving—he is almost literally giving a ‘hand out’, extending the full width and full weight of the richly lined cloak, which is so gratefully received by the poor knight.

In principle, this is very characteristic of Giotto’s art.

The slightly awkward stoop of the knight’s body and the set of his head reveal his feelings no less than his gaze does, as he seeks to meet the eyes of his relatively impassive benefactor.

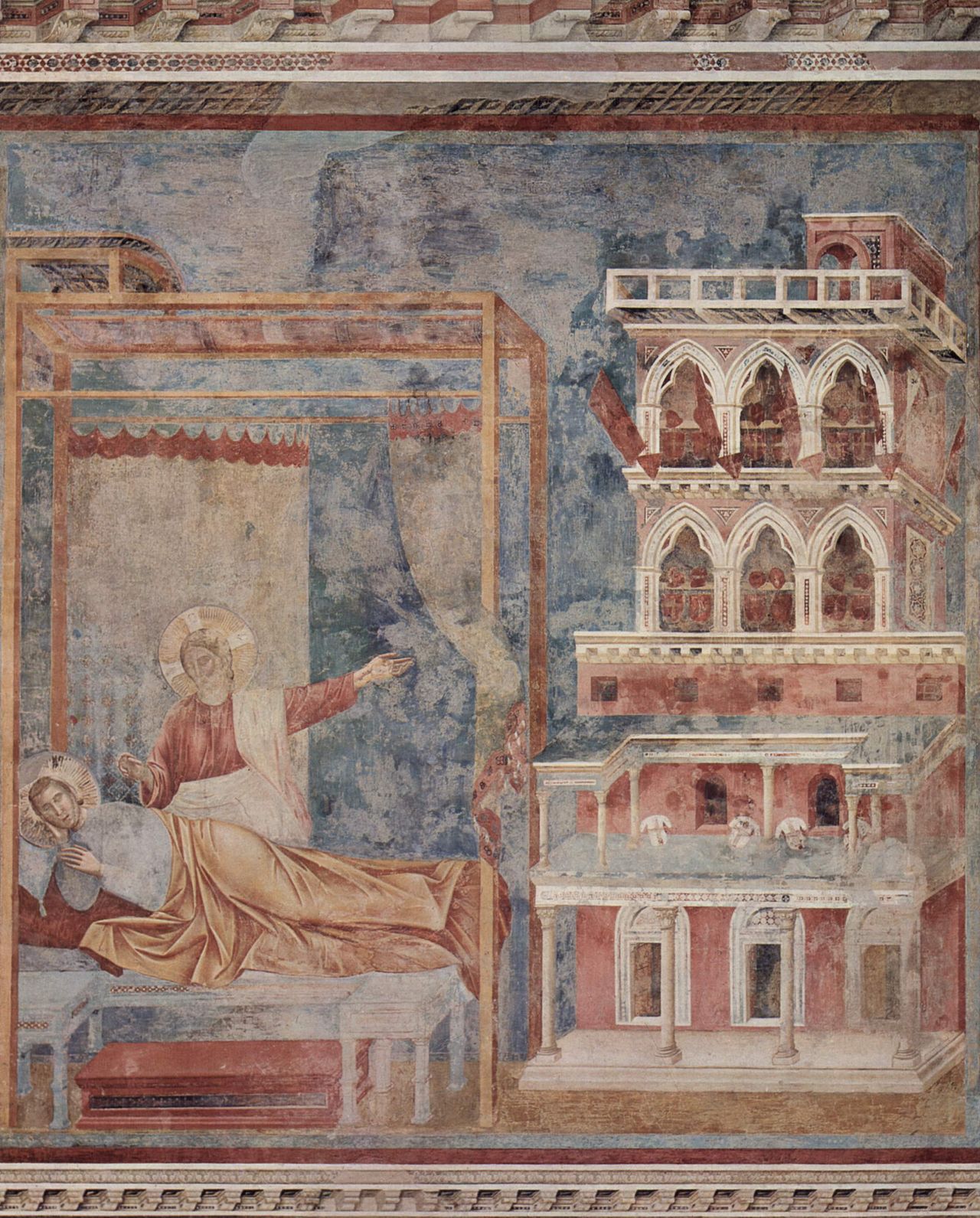

The right-hand scene in this first bay occurred ‘on the following night’:

‘When Francis had fallen asleep, God in his goodness showed him a large and splendid palace, full of military weapons emblazoned with the insignia of Christ’s cross’.

Alas, you can barely make out the banners with their crosses, even in the detail, because of the ravages of time. But there so much to enjoy in the pink and white palace of the vision. The classical columns and rounded arches of the two lower stories support trefoil arches in the next two (drawn from a different viewpoint) while a tiny loggia sits like a pent-house on the cantilevered balcony at the very top.

Francis misunderstood this dream and set out to become a knight. But the Lord corrected him, and he began, instead, to devote himself to the help of beggars and lepers.

The three scenes in the second bay take the story forward from these premonitions to Francis’s decision to forswear the world and to become a ‘pillar of the church’.

Here is how Bonaventure narrates the fourth scene:

‘One day when Francis went out to meditate in the fields, he walked beside the church of St Damian, which was threatening to collapse because of extreme age.

Prostrate before an image of the Crucified…he heard with his bodily ears a voice coming from the cross telling him three times; “Francis, go and repair my house, which, as you see, is falling completely into ruin”’.

What I enjoy most in this fresco, though, is the very convincing representation of delapidation: both in the ruinous building itself (which is out of scale to the human figure it contains, but otherwise full of space) and in the flaking paint on the inclined plane of that crucifix (a tour de force of drawing—although the altar is perhaps less convincing from the point of view of its perspective).

Francis became ever more contemptuous of his father’s wealth (he was a rich merchant), and for a time he was locked up in the hope that this would bring him to his senses. But one day, father decided that enough was enough, and that he would have to disinherit his rather difficult son.

‘He wanted Francis in the presence of the Bishop of the town to renounce his family possessions and to return everything he had… Francis showed himself eager to comply… He went before the Bishop and immediately took off his clothes and gave them to his father…He even stripped himself completely naked…The Bishop…drew Francis into his arms, and covered him with the mantle he was wearing.’

The angry father, restrained by his companion while clutching the rejected garments, stares almost in disbelief at Francis; but the young saint raises his hands and eyes in self-dedication to the Lord.

This scene will be the first one in the Assisi cycle to recur in Florence, some thirty years later; and I will discuss the all-important human drama in a little more detail in the final section of this lecture. But do look closely at the bystanders and notice the exchange of puzzled glances among children, among citizens, or between the bishop and his chaplains. (This concern, too, is a striking feature of Giotto’s art in Padua; whereas the naïve ‘hand-of-God’ in the sky and the rickety buildings are strikingly different.)

Straight on, then, to the sixth scene, where the sweep of the action across the whole bay is ‘closed’ by a truly palatial bedroom (with statues of angels on its roof, extensive ‘cosmatesque’ decoration, and slender marble columns, textured like bark, with classical capitals).

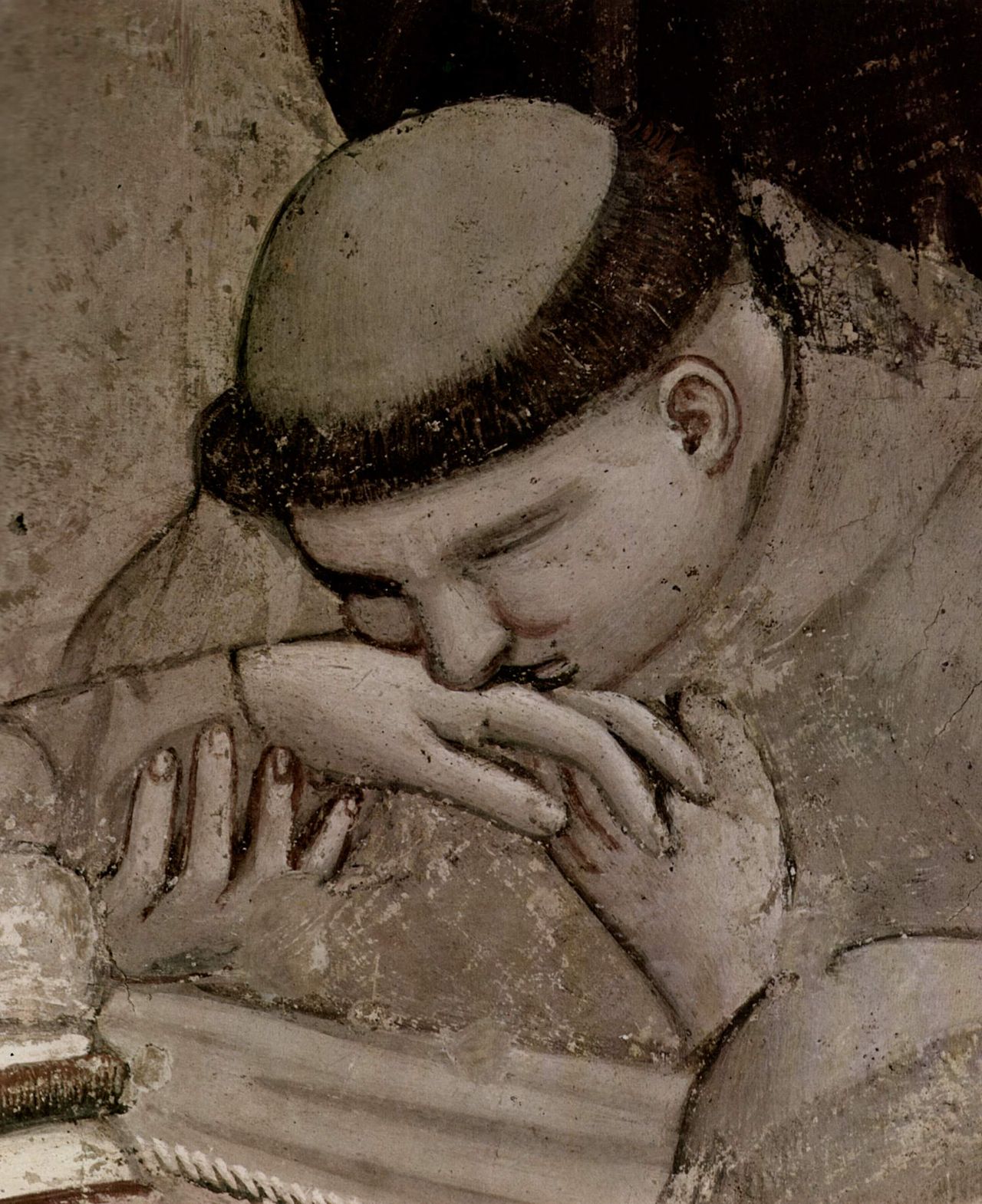

This is not a ruined church, nor a town villa, nor a bishop’s seat, but the papal residence in Rome. And to prove it, the luxurious bed-hangings are drawn back (and wrapped round a column) to reveal the pope himself, wearing his tiara, his gloves on, fast asleep, while one of his two bearded guards has dozed off, and the other is fighting to keep his visible eye open. (Both attendants are closely observed studies of the overmastering power of fatigue.)

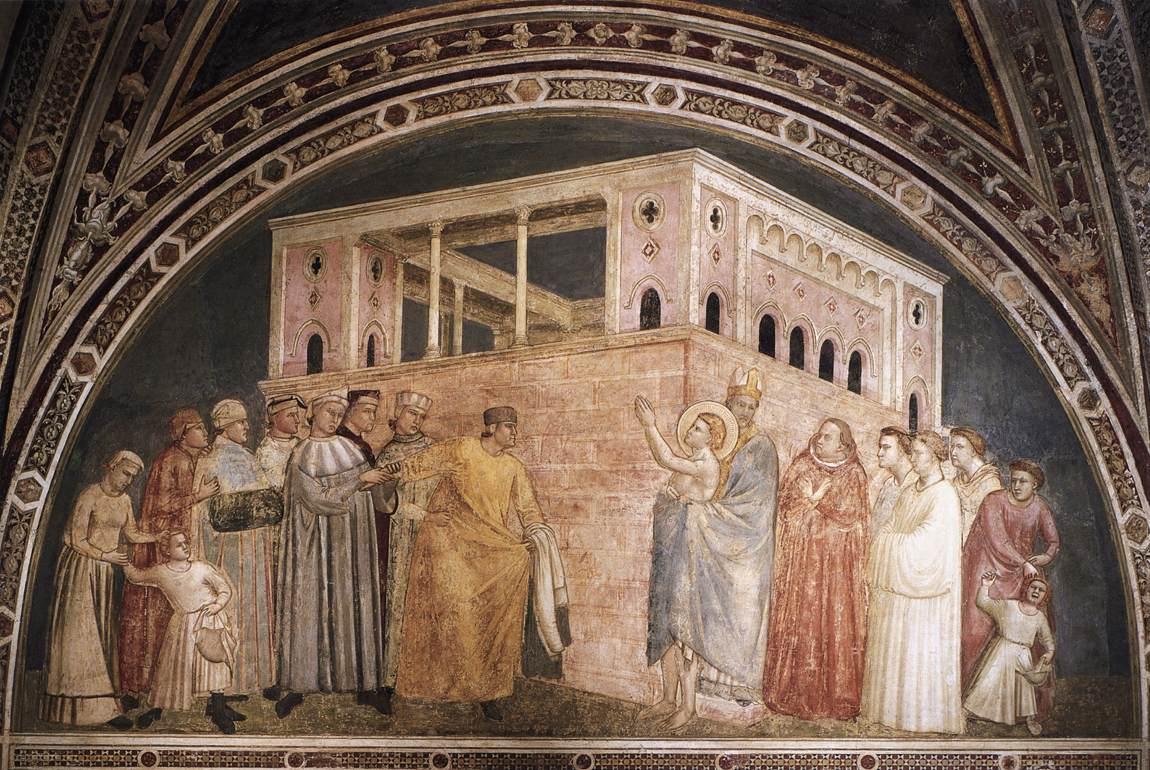

In St. Bonaventure’s biography, we read that, after he had renounced his inheritance, Francis formed a small band of disciples who followed him in his life of prayer, absolute poverty, and the alleviation of suffering.

He came before the Pope, and, after certain difficulties, was granted an audience, during which he told the Pope a parable. This parable reminded the Pope of a recent dream, and it is this dream we are shown in the fresco—a vision, in which he had seen:

‘a little poor man, insignificant and despised, who was holding up on his back the Lateran Basilica, which was about to collapse’.

Not the tiny church of St Damian, but the colossal Basilica of St John Lateran in Rome.

The fresco is a splendid example of pictorial narrative; and the only possible reservation one might have (as one looks at the detail of a very solid and three-dimensional Francis, with his right hand bent back and his left hand braced against a hip), is that the future saint is ‘too heroic’, and not the ‘insignificant and despised “poverello”’ who was described by Bonaventure.

(Incidentally, the basilica is drawn with a sufficient degree of realism for scholars to conclude that the fresco must have been painted shortly after major building work was completed there in the year 1291. And if you are curious to know what ‘cosmatesque’ means, or what a ‘soffit’ is, you have only to tear your eyes away for a moment from Francis’s face.)

The Pope did not interpret his dream literally.

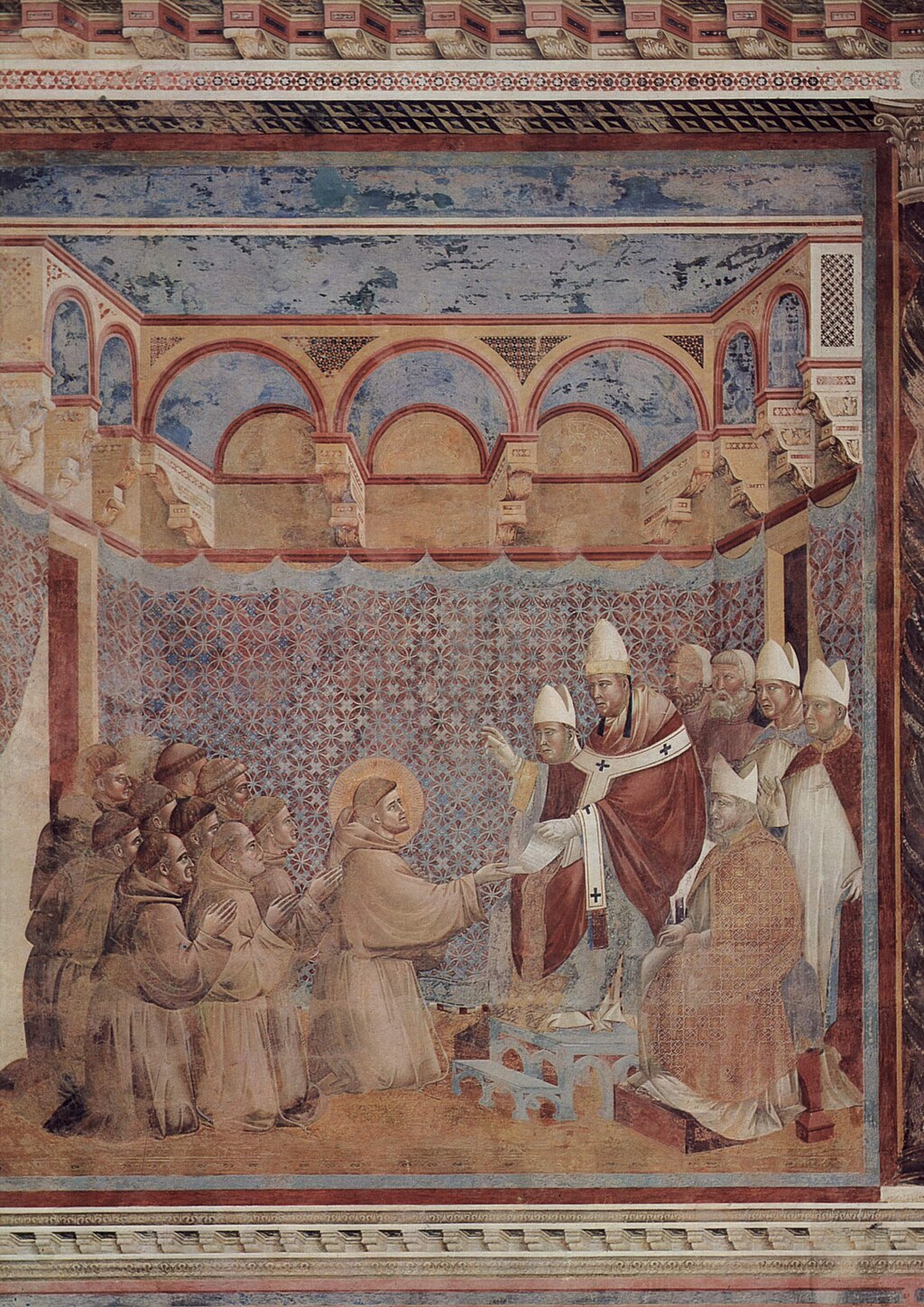

Instead, ‘he granted Francis his request’; and (in the left-hand scene of the third bay),

‘he approved the rule of life [which St. Francis had drawn up for his followers]. He gave them permission to preach penance; and he had small tonsures shaven on the laymen among Francis’s companions, so that they could freely preach the word of God’.

This fresco, too, is a good model for how to tell a story in paint. The audience chamber is palatial (with rich tapestry, prominent soffits and discreet use of cosmateque decoration). The two groups are contrasted, one kneeling in a scrum on the floor, the other clustered expressively round a raised throne. The ten tonsured heads on the left are balanced against five mitres and a tiara on the right; and the rhythm of the figures in each group focusses the viewers’ attention on the two hands, raised in supplication and in benediction.

In the third bay (scenes 7–9), we return to visions and ‘premonitions’ or ‘foreshadowings’—this time of St. Francis’s future canonisation.

St Bonaventure’s narrative for the seventh scene is comprehensive:

‘One Saturday in Assisi…Francis spent the night in prayer…in a hut…separated physically from the friars. At about midnight, while some of the friars were resting, and others continued to pray, behold!, a fiery chariot of wonderful brilliance entered through the door of the house.…

Those who were awake were dumbfounded, those who were asleep awoke terrified;…they felt the brightness light up their hearts;…they realised that their holy father, who was absent physically, was present in spirit, and transfigured in this image.

Like a second Elijah, God had made Francis a chariot and a charioteer for spiritual men.’

St Bonaventure’s narrative for the eighth scene is extremely brief, but again it is comprehensive:

A good while later,

‘one of the friars was praying fervently with Francis in a deserted church, when this friar was rapt in ecstasy, and saw among the many thrones in heaven, one more honourable than the rest.

And he heard a voice saying to him: “This throne belonged to one of the fallen angels; and now it is reserved for the humble Francis”’.

Having grasped the implications of the story, please look at the two frescos side by side, as you would view them in the Upper Church.

Notice how the cut-away convent on the left seems to balance the cut-away apse behind the altar to the right; and also how the visionary horses lead the eye up and across to the heavenly thrones, while the angel (whose presence tells us that we are being shown a vision) guides your eye down again to Francis, whereas Francis’s companion directs you with his gaze towards that angel. (More than just a touch, here, of Giotto in 1305.)

(The horses in the first of the pair are remarkably solid and convincing if you think of them as being terracotta statues; and the artist was enjoying himself when he painted their overlapping forelegs and the flowing tail. The foreshortened view of the candelabrum over the altar in the second is a piece of virtuosity requiring close observation of optical phenomena from a difficult angle: here, too, one may be reminded of similar feats in the Arena Chapel in Padua).

I add for good measure, a typical detail of a fresco from the same period in Rome by Pietro Cavallini (b. 1250). It will remind you of the pictorial origins of the monumental and very ‘Roman’ way of foreshortening complex three-dimensional objects in an oblique view.

And so we come to the last bay of the first wall, which has four scenes (10–13) instead of three. The left hand scene shows a casting out of devils—the devils of discord and of civic strife, of the kind I talked about in the introductory lecture. (Even the ground outside the wall is split).

‘Francis came to the city of Arezzo at a time when the whole city was shaken by civil war…Over the city…he saw devils rejoicing and enflaming the troubled citizens to mutual slaughter. In order to put [them]…to flight…he sent Brother Sylvester, a man of dove-like simplicity, before him like a herald, saying: “Command the devils to leave immediately”.’

As you can see in the detail, the devils left precipitously.

The juxtaposition of the four towers (the palazzo del comune, plus three of the nobility) withthe densely packed houses of the rich burghers with their projecting balconies, and the white wall of the city (with its Ghibelline merlons) makes a perfect illustration for the relevant section of my previous lecture; but the pictorial language is still more or less the same as we find in Duccio and Simone Martini (and is known to be based on a tiny miniature in a manuscript).

It is highly expressive (not least, in its cheerful indifference to the relative size of buildings and people)—but archaic with respect to the other side of this fresco. The loving study of the apse and bell-tower of a Gothic church is the perfect vehicle for the new message of evangelical love expressed by Brother Sylvester’s gesture. This is is the ‘state of the art’ in the 1290s.

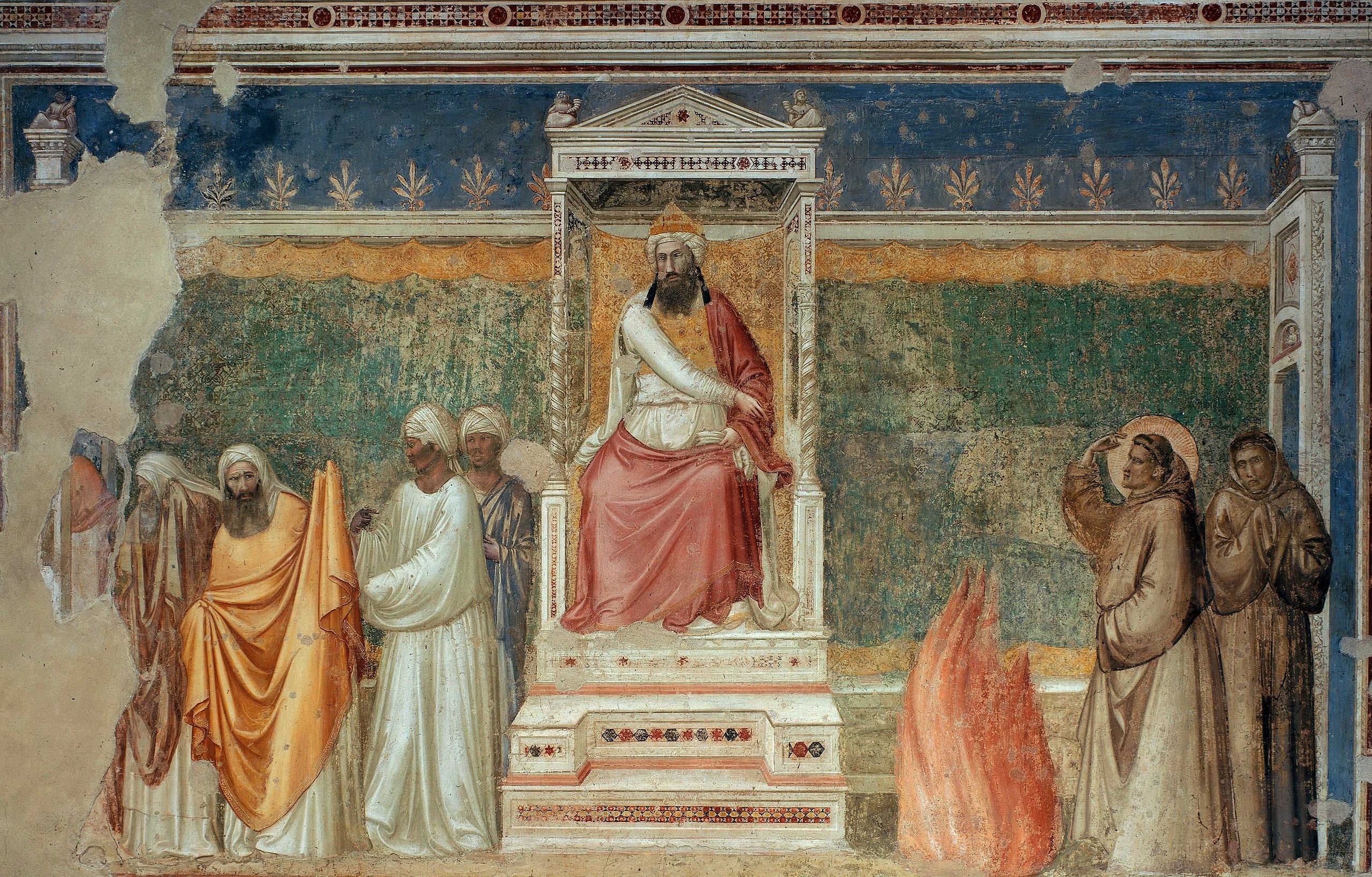

The next scene allegedly took place much later in Francis’s life and is of a totally different kind. After various abortive attempts to reach the Muslim East, he has come before the Sultan of Babylon, accompanied by Brother Illuminato. He preaches impressively before the Sultan and then proposes a kind of ordeal by fire. In Bonaventure’s words:

‘He said: “If you hesitate to abandon the law of Mohammed for the faith of Christ, command an enormous fire be lit, and I will walk into the fire along with your priests, so that you shall recognise which faith deserves to be held as the holier and the more certain”.’

The Sultan refuses the offer, because

‘he had immediately seen one of his priests, a man full of authority and years, slip away from his view when he heard Francis’s words’.

The gestures and body language are all crystal clear; and since we will come back to this scene in connection with the Santa Croce cycle, it will be enough to make three comments on the ‘headgear’. Francis is haloed; Illuminato is not; and the white headdress of the bearded priests establishes that they are ‘infidel clergy’—this being the shorthand convention that any artist of this period might use to identify, for example, a Jewish priest in a Crucifixion cycle.

Francis returned from the East safely to take part in the events represented in the last two scenes of this bay. Bonaventure’s story goes like this:

‘Praying at night, Francis was seen with his hands outstretched in the form of a cross, and his whole body lifted up from the ground, and surrounded by a sort of shining cloud.…And the unknown and hidden secrets of divine wisdom were opened up to him’.

Again, there is no need to put flesh on the bones of Bonaventure’s narrative—except to observe that Francis’s vision is a prefiguration, not of his canonisation after death (as in scene 10) but of his coming stigmatisation (scene 19).

Please allow yourself a few seconds to look at the bottom of the page to take in the combined effect of all four scenes in this last bay of the north wall.

Then turn your attention more closely to the final episode.

Visually, scene 13 is one of the most arresting in the whole cycle. It is quite unlike the exotic exteriors of scenes 10–12, totally credible in its detailed representation of the interior of a chancel of a church, in Umbria, during a Christmas Service, packed with more than twenty figures in contemporary dress (laymen on the left and ecclesiastics on the right).

You will not be surprised to learn that art historians want to attribute its execution (in whole or in part) to a different workshop; and you will be preparing yourself for another salutary shock when we move to the famous pair of scenes (14 and 15) lying on either side of the entrance wall.

Bonaventure’s narrative is particularly charming. It is almost as though he were using the very words of his source (who claimed to be eye-witness to a minor miracle); and the artist has attempted to capture every detail.

‘Three years before his death, Francis decided…to celebrate, at Greccio, the memory of the birth of the child Jesus. Having obtained permission from the Pontiff…he had a cradle prepared, hay carried in, and an ox and an ass led to the place’.

(At this point in his narrative, Bonaventure switches tense to use the vivid historic present):

‘The friars are summoned, the people come in, the night is rendered brilliant…by a multitude of bright lights and [there are] harmonious hymns of praise.…A solemn Mass is celebrated over the crib, with Francis as deacon…chanting the holy gospel; and a certain virtuous and holy knight, Sir John of Greccio,…claimed that he saw a beautiful little boy asleep in the crib, and that the blessed Father Francis embraced it in both his arms, and seemed to wake it from sleep’.

The child is shown with a halo, to make the point that he is, miraculously, the Christ Child.

The red-capped head of Sir John is just visible, between the officiants, peering down at the crib.

Look more analytically now at the architectural setting and the composition. The foreshortening of the base of the lectern is decidedly old-fashioned. The ciborium itself seems almost routine studio-work (in its chosen angle and the looping of the festoons). The animals are insignificantly small. The gazes of the priest, Sir John, and the standing friar are directed towards the crib, but the composition does not exploit diagonals and ‘caesurae’ to ensure that the miracle is at the centre of our attention; and the figure of St Francis is both unfamiliar and weak. The four most expressive heads among the crowd of by-standers are those of the friars looking upwards and away as they intone the chant.

And yet, and yet. The limited space in the foreground (our eyes are blocked by the full width of the horizontal screen), is almost miraculously extended by three stimuli to our inner eye. The press of overlapping bodies and heads in the narrow aperture suggests how large the congregation is. The empty pulpit, with its four slender candles, thrusts itself into the depth of the unseen nave. And most effectively of all, the back of the crucifix leans away (suspended by a piece of cord) in a dazzling feat of drawing, leaving to our imagination the suffering figure of Jesus. (Synaesthetically, one may be reminded of Keats: ‘Heard melodies are sweet, but those unheard are sweeter.)

We have examined all thirteen scenes lying on the north wall, and before we turn through a rightangle, you may be glad to be reminded of the general appearance of the north-east corner in this vertical section that takes us—higher even than the Old Testament cycle of the 1260s—right up to the start of the vault.

Are you confident as to which elements (cornices, columns, arches, niches, tapestry) are three-dimensional, and which fictive?

The next pair of images are probably the best-known and most loved in the whole cycle. They lie one on each side of the entrance in the east wall, and they are effectively united by their colour and simplicity of composition.

The story of the left-hand scene goes like this in Bonaventure’s Life:

‘Francis wanted to go to a hermitage.…Because he was weak, he rode on an ass which belonged to a certain poor man.…It was summertime…and the man became fatigued. Weakened by a burning thirst he [cried out].…“I will die of thirst, if I do not get a drink immediately”. Without delay Francis jumped off the ass, knelt on the ground and stretched forth his hands to heaven.…Then he told the man: “Hurry to that rock and you will find running water, which, in this very hour, Christ has mercifully drawn from the rock”.…[And so] a thirsty man drank water from the rock’.

The artist includes every fact and detail with astonishing economy. The donkey is cut in half (to suggest the journey that lies behind). One friar holds the bridle that checks the journey and turns quietly at his companion. The landscape is reduced to what is essential (stylised rock formation and naive plant life) to convey the arid desert. More important, its rhythm is a vital part of the composition. We are lured to raise our eyes and follow the arms of the saint towards heaven, and track sideways along the tensed leg, crouching back, jutting jaw and peaked hat of the ‘poor man’ as far as the stream that has appeared in the wilderness (or been miraculously struck from the rock as Moses did in Sinai.)

(Giorgio Vasari—the first writer, in the 1560s, to associate Giotto’s name with the Upper Church—cited this detail as his clinching evidence.)

The equally simple scene to the right of the entrance is so well known that I will omit Bonaventure’s narrative (which insists on the birds remaining motionless until they had received the saint’s blessing); and let you surprise yourself as to how much early Italian you already know as you puzzle out for the meaning of a few lines written by Francis himself, taken from his famous ‘prose poem’, a canticle, (a homage to Psalms 146 and 149), properly titled Praises of Created Things, in which he praises the Lord, successively, for the creation of three of our relatives in the natural world: ‘sister water’, ‘brother fire’, and ‘sister earth’ who is also our ‘mother’.

(The nouns and adjectives are all transparent or guessable. The three verbs are all singular and in the present tense, but do require you to understand their conjugation. Si’ = síi, is a second-person command from the verb éssere: ‘be!’. Enallúmini is a second-person indicative, ‘you give light to’. Sustenta and governa are third-person indicatives, ‘she sustains and rules.)

Laudato si’, mi’ Signore, per sor’aqua,

la quale è multo utile et humile et pretiosa et casta.Laudato si’, mi’ Signore, per frate focu,

per lo quale enallumini la nocte:

ed ello è bello et iucundo et robustoso et forte.Laudato si’, mi’ Signore, per sora nostra matre terra,

la quale ne sustenta et governa,

et produce diversi fructi con coloriti flori et herba.

Laudes creaturarum (Cantico di Frate Sole), 15–22

Notice how the eyes and gestures of the hooded grey-haired friar and the stooping, haloed saint direct our attention downwards to ‘sister earth’. In Pescia and Florence, the birds were all blackbirds, or black birds, perched on blossoming branches at eye-level, one of them opening its beak in song. Here the congregation are lapwings, larks, doves, magpies and what look like Muscovy ducks: all medium sized, ground-feeding birds; and—with the exception of the late-arriving scavengers (gulls or gannets?)—they stand stock still, listening to the sermon.

This brings me to the end of the second part of the lecture. You might want to stop here. You have seen no less that 15 frescos, in unbroken sequence, running the whole length of the south wall and straddling the entrance in the east wall, painted by a major artist in the 1290s, and you’ve been shown some of the reasons why his achievement here is considered to be a turning point in the history of Western Art.

You have learned all you need to know about the distinctive personality and mission of a quirky saint who died in 1222 and was canonised only two years later, having helped to bring about ‘climate change’ in medieval worship all over Europe. You have sampled the saint’s own poetry and gained an impression of how his life was re-told, in the 1260s, in the Legenda maior of St Bonaventure, a prominent theologian and General of the Order of Lesser Brethren.

In short, although the south wall still offers 13 more frescos, you could do worse than to walk out of the basilica at this point, passing between the Miracle of the Spring and the Sermon to the Birds and retaining their impact as your undiluted final impression.

But I hope you will stay with me for a substantial ‘coda’ in which I will present three of the remaining scenes (building up to the climactic moment of his receiving the stigmata and then to his death on the bare ground, a non-conformist to the last), before whisking you back to Florence to see how Giotto visualised these three episodes in the Bardi chapel in Santa Croce, some thirty years later. It will be quite instructive.

Before leaving Assisi, let us retrace our steps towards the altar and glance at three successive scenes on the south wall (numbers 18, 19 and 20 in the grand scheme of 28 frescos).

The first (18) occurred much earlier in Bonaventure’s narrative (one must turn back from Chapter Twelve as far as Chapter Four).

Francis had already received papal approval of his Rule, and although ‘he could not be physically present at the provincial chapters held by his followers’, we are told, ‘he was present in spirit’. Occasionally, however, he did appear visibly by God’s miraculous power:

‘At the Chapter of Arles [500 miles away], Anthony…was preaching to the friars.…A certain friar of proven virtue, Monaldo,…looked towards the door of the chapter and saw with his bodily eyes…Francis, lifted up in mid-air, his arms extended as though he were on a cross, and blessing the friars.’

The Gothic arches of the windows establish that it is an ecclesiastical building of some importance. Anthony’s halo shows that he, too, will be canonised. The rapt attention of Monaldo points to the miracle implied by Francis’s appearance. (It was quite common, incidentally, for an artist to convey that only one person among quite a number of by-standers had been able to see a spiritual reality, requiring the eye of faith.)

It is not difficult to see why the scene in Arles was shifted to this point in the narrative. We are now to contemplate the (twice anticipated) climax of Francis’s ‘Imitation of Christ’.

(Many of the events in the rest of Francis’s life are similar in kind to those associated with other saints: to receive the bodily nail-marks of the Crucifixion was unique.)

A word about the setting first. It is completely unlike the sophisticated interior of the Chapter House; and in its simplication it is close to the extreme stylisation of natural phenomena in the scenes of the Poor Knight and the Miraculous Spring (2 and 14). The two human figures appear in a landscape consisting of little more than a lump of modelling clay squeezed into shape by fingers (you can see their imprints on the sides) to represent a bare mountain supporting a few dendriform plants, without any regard for relative scale or perspective. But the diagonal plunge of the ‘mountainside’ is once again crucial to the impact of the composition; and the surfaces of the rock formations are now gleaming with light reflected from the all-important supernatural source in the sky.

The artist has responded to every detail in Bonaventure’s narrative to which there is nothing one needs to add.

‘On a certain morning about the feast of the Exaltation of the Cross, while Francis was praying on the mountain side, he saw a Seraph with six fiery and shining wings descend from the height of heaven.…[Then] there appeared between the wings the figure of a man crucified, with his hands and feet extended in the form of a cross.…

Francis…was filled with a mixture of joy and sorrow.

As the vision disappeared…the marks of nails began to appear in his hands and feet just as he had seen a little before in the figure of the man crucified.…Christ’s stigmata had been visibly imprinted on his flesh’.

The next scene (20, alongside, but in the next bay) has rather more than just three figures.

It represents both the last rites (Extreme Unction) being administered to the dying saint—who has in fact just expired, and is lying on a bare plank on the ground in the open air, as he had demanded in his will—and, simultaneously, a Vision of his immediate ascent to Paradise: a Vision, which, according to Bonaventure, was miraculously granted to two contrasted dreamers, both of them at a great distance from Assisi.

In the Upper Church, the two dreamers (respectively, a fellow friar on his own deathbed and the bishop of Assisi), are shown in the adjacent fresco (21); and it is necessary to quote the relevant paragraphs from St Bonaventure to make sense of what you are looking at here.

‘The minister of the friars in Terra di Lavoro [a region in Southern Italy near Naples, some 200 miles away] was Brother Agostino,…who was near death and had already for a long time lost his power of speech. Suddenly he sat up and cried out…: “Wait for me, Father,…I am coming with you!”. Amazed, the friars asked to whom he was speaking so boldly. He replied: “Don’t you see our Father Francis on his way to heaven?”. And at once his soul left his body and followed his most holy father’.

‘The Bishop of Assisi had gone at that time on a pilgrimage to the shrine of St. Michael on Monte Gargano [nearly 300 miles away on the Adriatic Coast, north of Bari]. The blessed Francis appeared to him on the night of his passing and said: “Behold, I leave the world and go to heaven!”. Rising in the morning, the bishop told his companions what he had seen, and returning to Assisi, he ascertained that the blessed father had departed this world at the very hour when he appeared to him in this vision’.

The scene could not be more different from its predecessor, and it is sufficient to ‘count heads’ to see why.

There are eleven confratelli on the ground beside the dying saint; six white-robed priests administering the sacrament; at least two dozen other men in holy orders behind them, partially concealed by the officiants; and ten flying angels who are escorting a very corporeal Francis, rising to heaven on a cumulus cloud.

It is a perfect foil to the art of the presumed Giotto of the north wall and the undoubted Giotto of Santa Croce in Florence.

We jump forward in time by about thirty years (from roughly 1295 to 1325), as we return to the church of Santa Croce in Florence, taking note of its shape—a typical ‘basilica’, with a wide nave and two narrower aisles.

The present church (the third on the site) was begun in 1294, and it is quintessentially a preaching church.

It is enormous—almost twice as long, at just over a hundred yards, as the Upper Church of Assisi.

In the 1850s, when they removed layers of whitewash from this chapel, they uncovered frescos which everyone agrees are by Giotto, including seven scenes from the life of St. Francis.

The condition of the paintings (even after two recent restorations) is poor; and they are also not easy to look at, because the chapel is so high and narrow and the frescos are laid out in three tiers on the side walls.

However, this excellent photomontage of the three walls makes it easy to grasp the general design. The story unfolds from top to bottom and the scenes follow alternately from left wall to right (in the traditional way).

You should be able to recognise, even at a cursory glance, the Renunciation and the Confirmation of the Rule; the Chapter House in Arles and the Ordeal by Fire in Babylon; the Death of Francis; and the two ‘remote’ Dreams of Francis’s Ascent (with a colossal area of damage).

You should also be able to evaluate the choice of scenes; and you should be asking: Where is the all-important Stigmatisation?

The first scene within the chapel lies in the left lunette.

It measures about fifteen feet by nine; but the exact dimensions are less important than its semi-circular-shape and the high position on the wall—as will become apparent if you ‘compare and contrast’ it with the same scene at Assisi, which is just the same height, but only half as wide, and placed only eight to ten feet above the ground.

The scene is obviously that of Francis’s renunciation of his inheritance, which, in both cases, becomes a confrontation between the irate father and the son, whose naked body is being clothed by the Bishop of Assisi.

In the earlier representation, the artist reinforces the ‘rift’ between father and son by putting tall, narrow, rather tottery buildings to each side—lay architecture to the left, ecclesiastical to the right—and by placing a dozen overlapping laymen on the left; whereas there are only two men in religious orders (notice the tonsures) behind the Bishop.

Giotto, in Florence, within the semi-circular form, opts for a remarkable single building. This is the very luxurious and solid palace (topped by an extravagant loggia), which Francis is rejecting. It is daringly foreshortened from below, and miraculously judged so that it fits effortlessly into the vault and dominates the composition when seen from below, at an acute angle, as you have to view it in the chapel. He adds women to both groups, placing a rebellious child at each end (instead of just two boys on the left, as in Assisi); and he makes the curving line of the heads in each group ‘echo’ the curve of the vault with superb control.

Do return to this pair of frescos at your leisure, and do force yourself to ‘compare and contrast’ all the details in these two close-ups. (It will help you to understand many of the advances in pictorial technique and conventions between the 1290s and the 1320s.)

For the moment, however, maintain your momentum and move on to the remaining scenes in the Chapel.

I pass without comment over the other lunette, on the opposite wall, showing the Confirmation of the Rule by Pope Innocent III. But I think it is very instructive to examine the earlier and later versions of the Chapter House at Arles.

In Santa Croce, it is placed in the middle of the left wall and is restored to its rightful place in Bonaventure’s narrative (whereas, in Assisi, you may remember, it had been placed very late in the story).

The differences in the architectural setting are again very striking. In Assisi, everything is foreshortened from a viewing point well off centre. The intense gaze of the compact group of friars directs our attention from right to left, parallel to the picture plane, towards the figure of St Anthony; but the diagonal lines of the architecture and the bench guide our eyes towards the rear of the room, as we follow the gaze of Monaldo (who was the only friar to be aware of the miraculous appearance of St Francis).

In Florence the viewing point is almost central. The narrow strip of tiled roof slopes down towards us, and its supporting columns link the roof to the marbled balustrade which encloses the seated friars, who are now seated in three parallel lines.

The two side walls, together with the three semi-circular arches, divide the pictorial space evenly into five; and the figure of Francis—more slender here, his hands placed higher, his glance downwards—is emphasised by its position in the centre of a frieze rather than at the far end of a diagonal reaching back into space.

Nevertheless, we should not read too much into these contrasts. The Assisi scene is taller than it is wide, and it is visually paired with the Stigmatisation to its right, as we saw earlier. The Florentine scene is wider than it is tall and is paired with the scene on the opposite wall, which has an equally centralised view of a dominant centre.

This fourth scene in Florence also invites us to register similar contrasts with Assisi.

Both frescos have the eastern potentate seated high on a throne, gesturing towards Francis and Illuminato, who stand ready to enter the fire; while the Muslim priests—dressed like Pharisees—exit hastily to the left.

But Assisi puts the tall throne, with its cosmatesque canopy, to the right; balancing it with an equally tall ‘mosque’ to the left. Both these edifices are set on the diagonal, and thereby help to focus our gaze on the central figure of Francis, whose restrained gesture continues the line of energy established by the Sultan, creating a single diagonal sweep in the direction of the flames.

In Florence, on the other hand, Giotto places the two faiths, Christianity and Islam, on either side of a judgement throne, from where the Sultan glances to his right at the discomforted Muslims, while, with his right hand swung right across the body, he gestures to the victorious Christians on his left; and Francis’s barely lifted arm can be read as a modest expression of triumph. There is also a most marvellous sequence of gestures and drapery folds here, guiding the viewer’s eye from right to left, down from the elevated throne to the defensively uplifted left arm of the retreating Imam, whose face itself is a ‘study’, showing Islam’s defeat.

And so we come to the last pair of frescos on the side walls of the Bardi Chapel in Santa Croce.

They show the death of the saint (with the ascent of his soul) and the two contemporaneous visions experienced by the dying Agostino, at Terra di Lavoro, and the dreaming Bishop of Assisi, even further away near Monte Gargano.

As you can see, both frescos are badly damaged, and huge areas of paint are missing—especially on the right, where the dying Agostino and the apparition have been completely obliterated.

But, despite their distressed condition, I would like to show you three details which document Giotto’s absolute mastery of the expression of different emotions—or rather, of different degrees of the one emotion which is appropriate at a death bed.