In this lecture, we move on to the period 1425-1450 but remain in the very heart of the ‘ancient circle’ of the walls of Florence.

The political and social context was essentially unchanged. In the second quarter of the fifteenth century, Florence was still an independent city state, whose wealth depended on the woollen industry, trade and banking. It remained a genuine republic, and its governing class was still drawn exclusively from merchants and professional men in the major guilds.

In fact, I need make only two additional points.

First, Florentine self-awareness and pride had been enhanced in consequence of a series of three extended wars against successive dukes of Milan and against the King of Naples.

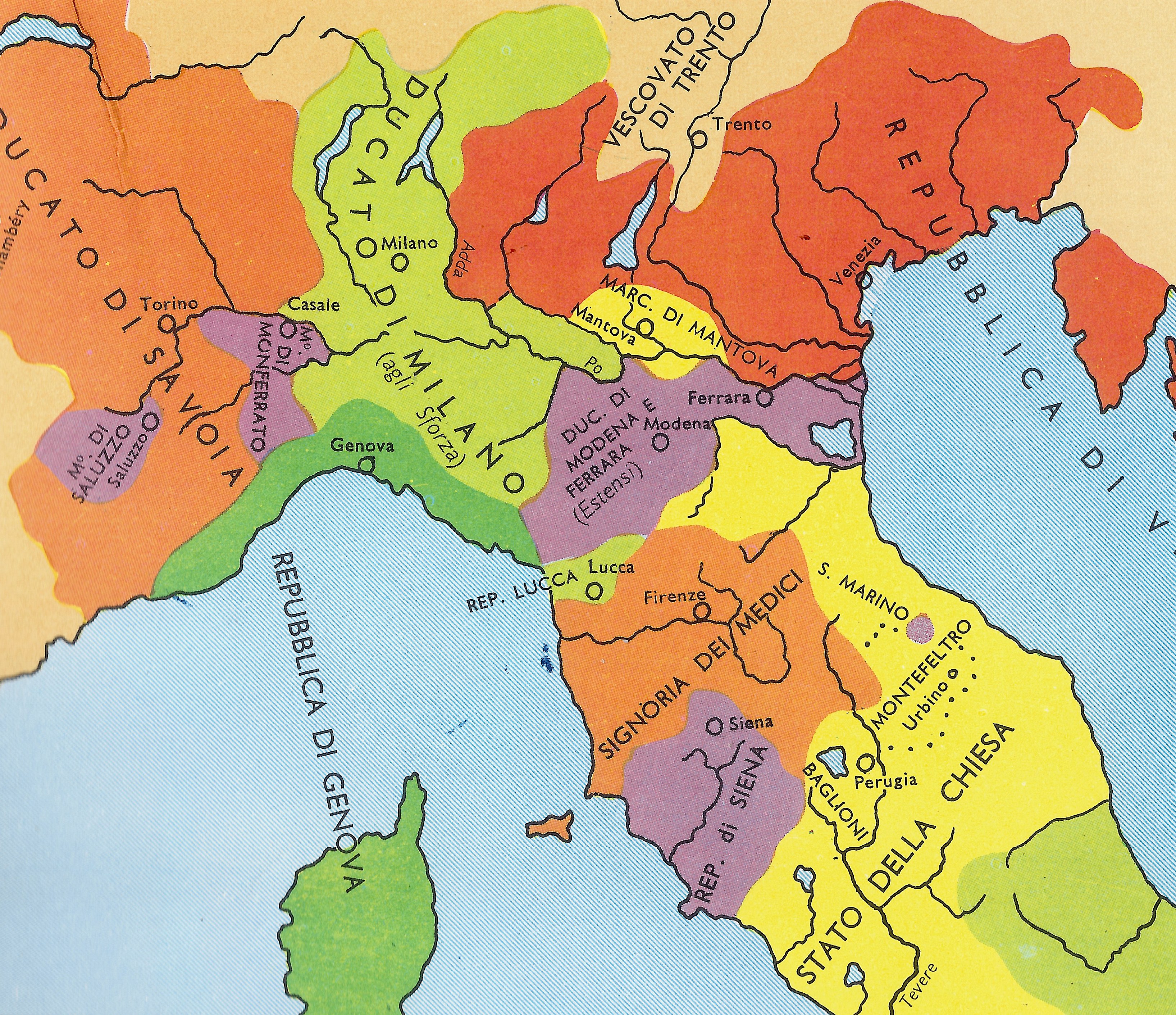

This map shows the extent to which Florence had been encircled by the Duke of Milan—his possessions are shown in green—at the gravest moment of the earliest and worst of these wars.

Things looked as bleak in Florence in 1401 as they did in Britain in 1940; and the existence of a certain ‘Battle of Britain’ spirit helps to explain a substantial new investment in public art—in buildings and in statues—intended to complete a number of great projects which had been begun a hundred years earlier.

Second, direct responsibility for the completion, maintenance and decoration of these public buildings was taken on by the major guilds, with the result that there was intense rivalry—of a kind fruitful for the arts—between the different guilds.

The statues by Donatello intended for the niches on the street walls of Orsanmichele, which we glanced at in the previous lecture, were done between 1413 and 1417 for the Guild of Armourers and for the Guild of Linenmakers, whose patron saint was St Mark.

It was the same guild which had responsibility for the Baptistry, a much older structure lying immediately to the west of the site for the Cathedral.

The Baptistry was always a very important building in an Italian commune, but it had particular importance in Florence since the city was dedicated to St John the Baptist.

It was quite common in other Italian communes for there to be magnificent bronze doors on these Baptistries; and so, in the last great days of the city’s expansion in the 1330s (not long after Dante’s death), a particularly superb door had been commissioned from a Pisan sculptor called Andrea.

It has no less than 28 quatrefoil panels, twenty of which tell the story of the St John the Baptist. (The narrative unfolds as it would in single pages in a book, from top to bottom.)

There is no time to study these fourteenth-century narratives, but I must at least give you a chance to look at St John as a boy—he is usually referred to as Giovannino in this popular scene—setting out into the Wilderness, and also the climax of the Dance of Salome, when she receives the Baptist’s head as her reward.

Andrea’s door (now the South door) was completed in 1336, in the decade when the Florentine economy had begun to go badly wrong, even before the city was hit by the Black Death in 1348–9, with its catastrophic, lasting consequences all over Italy and the whole of Western Europe.

Florence did slowly recover; and in 1401 the Guild of Calimala decided to commission a second pair of bronze doors to stand in the place of honour, opposite the Cathedral.

It was specified that the design should be more or less identical with that of Andrea’s doors, in that there would be a total of 28 panels, all with quatrefoils. But in this case the ‘Top Twenty’—the narratives in the upper five rows—would be given over to the Life of the Saviour and the story would unfold from bottom left to top right (as it does in Duccio’s Passion Cycle on the rear of the Maestà in Siena) so that the two doors are treated as a single ‘page’.

A competition was arranged to find the best qualified artist; and the subject of the test panel was Abraham’s Sacrifice (or attempted sacrifice) of his son, Isaac.

The image you see here is the entry submitted by one of the greatest runners-up in the history of Art—none other than Brunelleschi.

This was a panel measuring two feet square, considerably more advanced, in every possible respect from the quatrefoils on the North Doors in Florence.

Without going into detail about the evolution of techniques in the casting of bronze, I must make two essential points concerning the method of these artists.

First, Ghiberti had already learned how to create a panel in one piece, rather than bolting the main figures, cast separately, on to a ground, as Andrea Pisano and Brunelleschi had done. But Donatello taught him how to unify the panel still further, by graduating the depth of relief smoothly, from figures well in the round, in the foreground, to others that are little more than bumps or lines on the surface in the background. Donatello, in fact, treats the panel almost as a monochrome drawing; and he unifies his composition, as we saw in the previous lecture, by introducing the new system of perspective that would not be formulated in writing by Alberti for another ten years.

Second, Donatello and the later Ghiberti enhance the feeling of unity in the panel by gilding the whole surface, instead of contrasting gilded figures against a plain bronze ground.

We can now return to the Baptistry in Florence and begin to focus on the paired doors on the east side, facing the Cathedral. (The originals are now safe from the weather and the traffic in the cathedral museum). These are the ones known as the ‘Gates of Paradise’, a locution attributed by Vasari to Michelangelo who said, ‘they were so beautiful that they would not be out of place alle porte del paradiso’. (Question: did he really mean the two battenti of the East Door, or was he referring to both of Ghiberti’s portali, north and east?)

The commission for this new pair of doors was assigned in 1425, that is, in the same year as Ghiberti installed the first.

By this time, he was in his late forties and could dictate his own terms. It was apparently at his own insistence that there are not 24 quatrefoils, as in the first door, but 10 square panels (like those he was doing for Siena), just over two and a half feet wide.

The narratives are presented in pairs, like the spread of an open book, and the narratives follow each other from top to bottom, again like a book.

The frames of each door are glorious things in their own right and it would be possible to devote a whole lecture to the curvilinear flora (each plant is different) and the fauna (can you spot the frog and the bird?), and more especially to the characterisation of the slender prophets and sibyls standing in their niches, or to the portrait heads peering out of little portholes, as in this pair from the bottom row: hatless or turbaned, looking down or catching our eye, with different styling for their beards.

All ten panels are illustrations to the Old Testament; but each one has a different protagonist, and each tells a complete story consisting of numerous distinct episodes which are skilfully distributed over the surface of the panel in a unified composition.

The narratives in the first six panels are compact, in that they are drawn from the opening chapters of the Book of Genesis and do not omit any significant episodes. The last four panels may seem dispersive and unrelated because they illustrate scenes from four other Books But the subject of the doors should not really be described as ‘Stories from the Old Testament’, and nothing more than that, because there are links between recurrent situations and recurrent images which bind all ten panels together and which together throw light on the meaning of baptism and the functions of a Baptistry.

REUBEN: WHAT WE NEED HERE IS THE DIAGRAM (I REMEMBER IT AS MY OWN), WHICH SHOULD BE SOMEWHERE IN OUR ARCHIVE, OF THE SUBJECTS OF THE TEN PANELS. IT IS LAID OUT TO RESEMBLE THE TEN PANELS. EACH SQUARE SAYS LITTLE MORE THAN

JOSHUA,

Book of Joshua

It is these links we must now investigate in what will be a pretty hefty, ‘non-digressive’ digression. It will in fact be a copy-book example of what Aristotle called circumscriptio, a deliberately simplified sketch of a difficult new topic—a preliminary overview in universali et typo, in which free use may be made of analogies, similes and extended metaphors.

(My ‘circumscription’ itself may be compared to the spiral tunnels near Kicking Horse Pass in the Rockies, where the nineteeth-century engineers had not realised that the gradient linking the western and eastern sections of the Canadian Pacific Railway at Big Hill would be dangerously steep. In 1909 a later engineer of genius designed two tunnels (I quote from Wikipedia) ‘which loop in a figure of 8 inside the mountains, effectively lengthening the track to reduce the grade to a safe 2.2%. Trains exiting one tunnel cross a bridge and enter the other, sometimes resulting in the front and rear of a long train being visible in different parts of the loop simultaneously’. This is exactly what I was privileged to see on the day of my visit many years ago.)

You will emerge from my digression at the same point in the exposition, but you will be at a different height from which will enable you to enjoy the scenery of the rest of the journey in perfect peace).

Circumscriptio

Aristoteles vocat circumscriptionem notificationem alicuius per aliqua communia. Oportet quod aliquid figuraliter dicatur, id est secundum quandam similitudinariam descriptionem. Ad hominem pertinet paulatim in cognitione veritatis proficere.

Aquinas, Commentary on Ethics I, 7, 1098a, 27

(Cf. Patrick Boyde, Dante Philomythes and Philosopher, pp. 62, 315 and 360.)

Simplying to the utmost degree, one could say that the unifying features on the Gates of Paradise are all derived from the once-orthodox Christian interpretation of the history of the Jews (an interpretation which lingers on, given that, until quite recently, all historical events have been dated as either AD or BC).

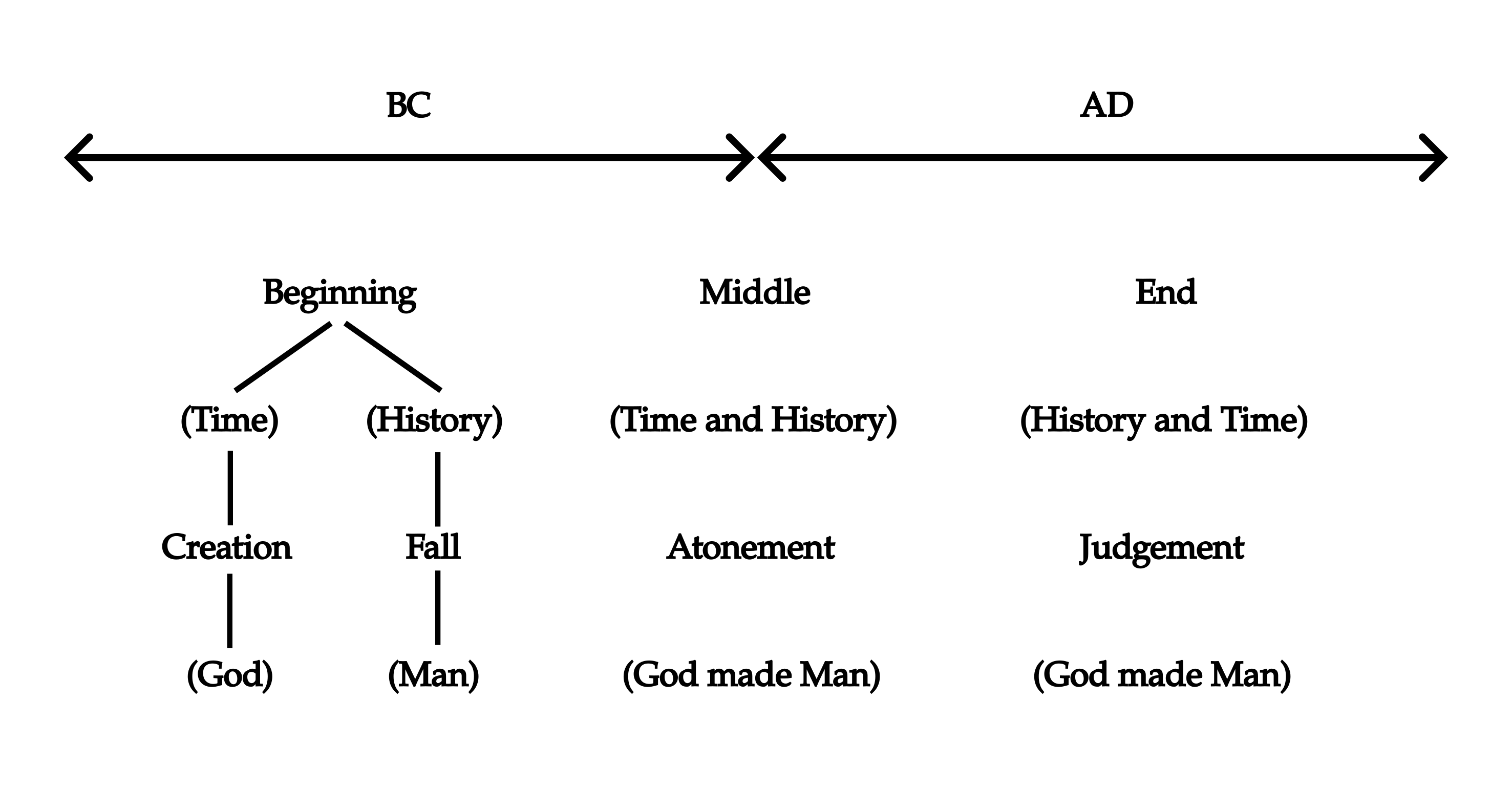

Remember, then, that for educated Christians at the beginning of the fifteenth century—and for many centuries before and after—the division into two eras carried the implication that time was finite, and that history was marked out by three main points.

There had been a Beginning (only about 7500 years ago, so they calculated) and a Middle or turning point (1400 years ago); and there was soon going to be an End. On the final day—the Day of Judgement—Time itself would cease to exist, giving place to Eternity, in which the immortal soul of every individual would find itself for ever ‘face to face’ with God, or forever ‘back to back’ with God, depending on the use each soul had made of their existence in time.

Always keep in mind that you cannot have a distinctively Christian view of history unless you correlate time and eternity, and unless you believe that God is involved with man, and man with God.

(The huge fresco in the Dominican church of Santa Maria Novella, dating from 1365-67, offers a reassuringly Florentine vision of the ascent of the blessed to Paradise on that Last Day.)

You may have felt a twinge of unease about my use of the words Time and History, but it is important to grasp the exact nature of the distinction between the terms in order to clarify the relation of the Midpoint to the Beginning.

The beginning of Time lay in a free act of God: the creation of the universe.

The beginning of History lay in a free human act: Adam’s disobedience.

The Midpoint lay in a free act of God-made-man, for it consisted in the atonement for Adam’s sin by the willing self-sacrifice of the Second Adam. The effect of that sacrifice was to restore human nature to some semblance of what it had been before the Fall.

For many centuries, Christian writers and preachers had used various similes and metaphors to make sense of the triad: Creation–Fall–Atonement.

The sequence was compared, explicitly or implicitly, to Making–Breaking–Mending, or Birth–Death–Rebirth, or Freedom–Capture–Ransom, or Health–Disease–Cure, or Voyage–Shipwreck–Rescue, or simply (and most important for us), Cleanness–Staining–Washing.

Clinging to these metaphors, and recognising them for what they are—viz. nothing more than successive and remote ‘approximations’—you will not be completely wide of the mark if you take it on trust that, in the orthodox teaching of the late medieval Catholic Church, human beings of any race or condition, at any point in time after the Crucifixion, may be cleansed, rescued, healed, ransomed, reborn or mended if they will freely avail themselves of God’s indispensable grace.

Grace is a gift. You cannot earn it. It cannot be purchased at a stated price, and it cannot be bargained for. But its balm cannot be infused against your will, nor can its seed take root if you have not prepared the soil and do not keep the tares at bay.

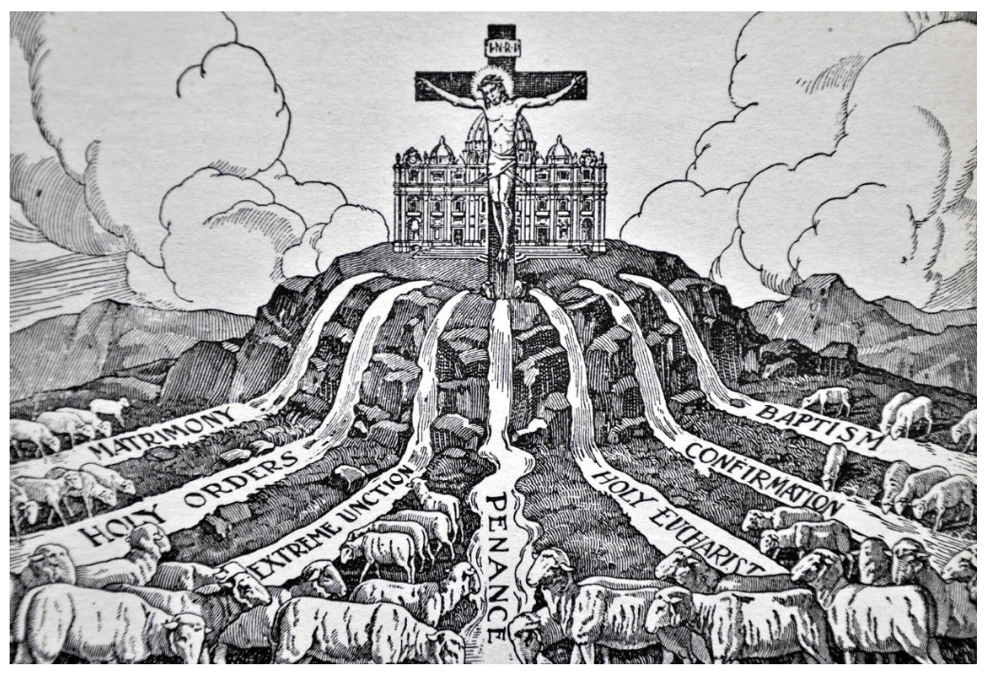

Grace (it was thought) is normally channelled to the soul through the Seven Sacraments of the Church and, principally, through Holy Communion (the second of the Seven), defined in a popular Catholic encyclopaedia as ‘the receiving of the consecrated bread and wine at the climax of the Eucharist, the ‘Great Thanksgiving’, in the liturgy of worship and scriptural readings known as the Mass’.

But the precondition of all the others is the initial sacrament of Baptism.

The ‘cure’ is not instantaneous and depends on the continuation of the ‘medication’. It will not be stable and complete until the eternity following the Last Judgement. But anyone who is ‘washed clean’ of the ‘stain’ of original sin through Baptism— at an eight-sided font, in an eight-sided Baptistry —is in fact ‘passing through a gate’ that may lead eventually to Paradise.

Baptism, then, is the ‘Gate of Paradise’.

We pass on now from Baptism to Time and the medieval conceptualisation of the relationship between BC and AD.

The life of individual Christians, in time after Christ—in life AD, in the ‘years of our Lord’—may offer a foretaste of the eternal bliss of Paradise, if their souls are in a state of grace. Similarly, so it was believed, there had been some kind of foretaste of the life AD in the era before Christ, life BC.

God revealed his existence—and his purpose for mankind—to one people, freely chosen by him: the Jews.

With them he made successive ‘treaties’ or ‘pacts’, or ‘covenants’. Provided they would ‘do his commandments’ and ‘recognise no other God but him’, he would help them to win a ‘Promised Land’, a ‘new Eden’, and at the appointed time he would send them not simply another high priest or a prophet, but the Messiah, the ‘Anointed One’ (i.e. the man anointed to be King)—‘the Christ’. (In Greek, christós was a rare adjective meaning ‘anointed’.)

Christians believed that the Jews had wilfully refused to recognise that Jesus of Nazareth was ‘the Christ’. But Christians also came to accept that God’s limited interventions in the history of the Jews had produced a whole series of correspondences between significant people, customs, and crucial events—a series in which the new order had been ‘foreshadowed’ or ‘anticipated’ in the old.

When Christians studied the Jewish sacred books—significantly, they called them the Old Testament—they sought to identify such partial revelations—such ‘prefigurations’, or, as they usually called them, such ‘figures’ or ‘types’—in Jewish history and Jewish religion.

The first of two Tables reminds you of a few key correspondences between people and observances, in particular, the relationship between blood sacrifices and the Eucharist, and between circumcision and Baptism.

| Some Correspondences between Institutions and Rituals | |

|---|---|

| BC | AD |

Judaism Mosaic Law High Priest Blood Sacrifice Circumcision |

Christianity Evangelical Law Pope Communion Baptism |

A second Table reminds you that many historical events which took place ‘in the years before Christ’ were also read as foreshadowings of later events—not just those in the life and Passion of Christ (although these were the most important), but events recurring in the moral life of any individual Christian living ‘in the years of Our Lord’.

| Some Correspondences between Events | |

|---|---|

| BC | AD |

The History of the Jews Adam and Eve Cain and Abel Israelites and Golden Calf Abraham and Isaac Noah’s Ark Crossing the Red Sea, River Jordan Joshua and Jericho, David and Goliath Solomon and Sheba |

The Moral Life of the Christian Temptation, Sin Envy, Hate, Violence Worship of False Values Obedience, Sacrifice Rescue from Sin Regeneration, Beginning a New Life Victory by God’s Grace Reconciliation |

The old ‘offending Adam’ (in Portia’s pregnant phrase) still persists in time AD. And this persistence—Original Sin, as it is traditionally called—leads to many successive ‘falls from grace’ in the life of any individual, which are analogous to those in Jewish history.

But those who receive the body and the blood of the Second Adam in the Sacrament of the Eucharist, having been granted Absolution for their recent sins, having been washed clean’ of Original Sin in the baptismal font—having gone through this door—will experience ‘newness of life’, ‘triumph over adversity’, ‘peace’ and ‘reconciliation’ with the God in whom they have ‘put their trust’.

They will have a foretaste of eternal life in Paradise.

This has been a substantial digression. But as I insisted earlier, it has not really been a digression at all.

The second Table is close to being a diagram of the ten panels on Ghiberti’s Gates of Paradise. And in the commentaries that follow, you will see that it is only by setting the panels in their cultural context that you can understand the choice of episodes and understand why they are not just Stories from the Old Testament but a unified Narrative Cycle.

The first panel is placed top left on the Door. Remember that it is about two and a half feet square, and that you can never see it from the angle at which the photograph was taken, because it is placed about six to eight feet above your head. Remember, too, that the foreground figures are in deep relief, so that they present very different views as you move your position.

It is packed with action, and its subject is the Beginning of both Time and History.

Time began (‘collaterally’, so to speak), with God’s creation of the universe out of nothing, ex nihilo. This is what Ghiberti represents (in very flat relief at the top of the panel), in the flying figure of Jehovah in the centre of the concentric heavenly spheres.

The creation of the many parts of the universe (the opus distinctionis) took place in time and occupied six full days. It culminated in God’s creation of Adam out of the dust of the ground and the creation of Eve from a rib in Adam’s side. These two events occupy most of the foreground of the panel, and the protagonists are shown in very high relief

Next comes the beginning of History, which consists in the first significant act by man (in biblical Hebrew, Adam means ‘man’). The story of the Temptation and the Fall is almost invisible, however, halfway up the left side of the panel.

The immediate consequence of the Fall is shown on the right, where the whole of humankind (totum genus humanum), in the persons of our common ancestors, is being driven out from the Gate of Paradise.

In the creation of Adam, the Lord raises his right hand in the received gesture (half blessing, half command), while with his left hand, he helps Adam to rise to his feet. Adam himself, in a complex, almost awkward pose, flexes his left knee and pushes down with his right hand to show off the muscles in his shoulder, arm, and abdomen—for his body is intended to be not just beautiful, but manly.

In the centre of the panel, however (where he is shown again), Adam’s weirdly elongated body becomes almost as sharp-edged as the rocks on which he lies sleeping, while Jehovah faces the other way now, and draws the figure of Eve from his side.

Her body, very similar to Masolino’s Eve, is beautiful, feminine, smooth; and it has been given just the gentlest torsion to show off her small high breasts and the fullness of her thigh. The illusion of roundness (in flat relief) is enhanced by the way the infant angels embrace her arms and waist.

You may be thinking that Ghiberti chose to place the creation of Eve in the centre of his composition simply for the pleasure of posing her lovely body in opposition to the bearded, draped form of Jehovah.

It certainly does seem odd that the Temptation and the Fall—so clear when seen in a close-up—should be so hard to detect when one is looking at the whole panel.

But the prominence given to the younger partner, Eve—the second created—is part of a conceptual pattern which we will find running through the whole cycle. Christians have succeeded the Jews. And the creation of Eve from Adam’s rib was a recognised ‘prefiguration’ of the way in which the Christian Church issued from the Jewish Synagogue.

Before we leave the subject of features that are almost invisible but conceptually important, I must also call attention to the stream, trickling across the foreground. It is one of the four streams in the Garden of Eden which were allegorised as ‘types’ or ‘figures’ of the River of Life, the fons vitae, that would flow in water and blood from Christ’s side to wash away the sins of the world.

By contrast, Adam and Eve seem to stagger and stumble, the husband being almost hidden behind his wife, who is now all too aware of her sexuality, despite, or because of her fig-leaf girdle.

Her complex pose expresses not just guilt and shame, however—as in Masaccio’s interpretation of twenty years earlier—but fear, anger, and even a touch of defiance.

In the second panel, the numerous scenes are distributed in a single landscape in a more traditional but very satisfying way.

A narrow strip of foreground allows just enough room for two men and a pair of oxen.

Behind them a stylised rock formation (which would have been perfectly at home in the art of Duccio or Giotto) rises from left to right, transforming itself into a ‘table-mountain’ which offers two ledges and a flat summit to accommodate more actors, while leaving just enough room in the sky for Jehovah to appear twice.

The simple scheme is varied, however, by the suggestion of a valley cutting the rock, and ascending from right to left (following the course of a doubtless symbolic stream), past a dense clump of maritime pines, to reach another hilltop on the left, with figures seated in front of a mud-and-straw hut.

To the left of the valley, Ghiberti chose to represent the state of humanity after the expulsion from Eden, rather than any specific episode.

Adam and Eve are shown with their first two children at their knees. Father is resting from the toil that has given him the burly physique of a farm labourer, while Wife is spinning from the distaff. It is the time ‘when Adam delved and Evë span’.

Although their accommodation is primitive, it is not without a certain idyllic charm, and the mood is sustained in the hillside and bracken below.

The two children have become young men in the foreground; and they have specialised in their labours. In modern terminology, one is a pastoral farmer, the other arable.

Abel, as you saw, has the easier life, sitting beside his alert dog, watching the sheep in the bracken. There is no sweat on his brow.

Cain has to exert himself rather more. But we gain nothing but a sense of pleasure from his intent form, as he presses the ploughshare deeper into the poor soil behind the lean flanks of the straining oxen—something you could still see in Tuscany in the 1950s.

The history of man’s broken relations with God continues on the other side of the valley.

It begins with a hint of reconciliation but ends in the first recorded violent death in history.

On the summit of the table-mountain, we witness the first of many sacrifices—attempts by man to make a peace offering. We also see that, while God finds some sacrifices acceptable—Abel’s flame rises—he finds others unacceptable, for Cain’s does not rise.

The younger, the weaker—the prefiguration of Christ and the Christians—is preferred.

Notice how, even while he kneels, the elder is filled with envy, resentment and hatred, for this is the first of many episodes where the split between man and God leads to a division between man and man, and, in particular, to a rift between elder brother and younger brother.

So, in the next detail, still from the same panel, Cain swings his great club up high for what is clearly a second time—a superbly energetic pose—before bringing it down again on the cowering, defenceless Abel.

Giorgio Vasari commented ‘that the very bronze used for Abel’s limbs itself falls limp’.

As I hinted, this scene looks forward to the Crucifixion, and backwards to the expulsion—it is a second Fall.

In the right foreground, Cain raises his hand to God in a gesture of protest or defiance, which recalls that of his mother Eve; while behind him the stream of the River of Life flows past in vain.

The third scene is dominated by built forms rather than a natural landscape, for behind the stonework of the altar, on the right, and the woodwork of the hut—which is moulded in dramatic perspective and in very high relief—there appears not a mountain, nor a pyramid, as you might think, but Noah’s Ark, presented in that form.

It is resting on Mount Ararat, and hence rises to the very top of the panel.

Ghiberti has omitted the building of the Ark, the Deluge itself, and the sending out of the raven and the dove after the waters subsided, which occupy the sixth and seventh chapters of Genesis. He picks up the story at a late point, in Chapter 8, verse 15, when:

Noah went forth and his sons and his wife and his sons’ wives with him, and every beast…and every bird…went forth by families out of the Ark.

In front of the door (and concealing the door)—in very flat relief—you can see a group representing Noah, his wife, and his three sons and daughters-in-law, from whom the three main races of the world would descend.

Very high in the sky, the ‘fowls of the air’ are flying away, while an elephant and a deer are making their way into the mountains. Lower down, a very ‘grisly’ bear is just emerging, almost as if from hibernation.

We are also shown, in profile, a lion and a lioness, who are looking hungrily at the ox who has been splendidly foreshortened from behind, to show off his rump steaks.

(All these animals, incidentally, are perfect examples of how a fifteenth-century artist would use his collection of drawings to build up any commissioned picture, almost as a child might use a set of stencils.)

The foreground of the panel shows two distinct scenes, the first of which follows almost immediately on the sentence quoted above (Chapter 8, verse 20).

It represents a very important stage—and a prefiguration—in the chain of events preparing the way for the Atonement.

Noah, we read, ‘built an altar to the Lord and took of every clean animal…and offered burnt offerings on the altar. The Lord smelt the pleasing odour’.

As a result, the Lord made a Covenant with Noah and his descendants—described in Chapter 9 of Genesis—that ‘never again shall there be a flood to destroy the earth’.

The ‘sign’ of the covenant is renewed whenever God sets the ‘rainbow in the cloud’. (You can just make out that God is speaking from within a rainbow.)

It is not yet a promise to redeem humankind. But the ‘acceptable sacrifice’ of Noah has at least led to a promise not to destroy us utterly.

The second scene, however (dominating the left of the same panel), is yet another of the many that tell of divisions between brothers, and of conflicts still to come.

In Chapter 9, verse 20, we read that:

Noah was the first tiller of the soil. He planted a vineyard; and he drank of the wine; and he became drunk and lay uncovered in his tent.…Ham saw the nakedness of his father and told his two brothers outside.

By so doing he had clearly broken a taboo, for:

Shem and Japheth took a garment, laid it upon both their shoulders and walked backward and covered the nakedness of their father. Their faces were turned away, and they did not see their father’s nakedness.

The upshot was that Noah laid a curse on Ham and his descendants; a curse that would be used as an excuse by the European descendants of Japheth to indulge in the slave trade of Africans well into the nineteenth century—but that is another story again.

The fourth panel deals with Abraham.

It is similar in conception, in the sense that Ghiberti does not represent a notorious example of divine vengeance—the destruction of Sodom and Gomorra—but dwells on two important prefigurations of, or steps towards, the Atonement.

Enjoy for a moment the harmony of the composition and the beauty of the frame before we tackle the story.

The scene on the left shows Abraham and Sarah, still childless as a couple, and already in their late nineties.

In a grammatically complicated passage, we are told that ‘the Lord’ (in the singular) ‘appeared to Abraham’; that ‘he beheld three men’, to whom he offered hospitality (this was regarded as a ‘type’ of the Eucharist); that Abraham addressed them as ‘my Lord’ (in the singular); and that they (in the plural) prophesied that ‘Sarah, your wife, shall have a son’. We also read that: ‘Sarah was listening at the tent door behind him’.

(Ghiberti is wonderfully attentive to all the details of the narrative.)

The three ‘men’ are shown with angels’ wings, as was customary in the iconographical tradition. Remember, though, that the encounter—with those strange shifts from plural to singular and back again—was normally interpreted by Christians as the first appearance of the Trinity, the first revelation that God is Three as well as One.

Despite her incredulity, Sarah will indeed bear a child, to be named Isaac.

Ghiberti now moves forward a dozen or so years in the next scene, where Abraham has been ordered by God to make a human sacrifice of his own son.

Having journeyed for three days, Abraham leaves his two servants together with the ass at the foot of a mountain.

Then he makes Isaac carry the wood for the sacrifice, concealing his intentions, by telling Isaac that God would ‘provide a lamb’. At this point, one must simply read the words from Genesis:

When they came to the place of which God had told him, Abraham built an altar there, and laid the wood in order, and bound Isaac his son, and laid him upon the altar, upon the wood.

Then Abraham put forth his hand and took the knife to slay his son. But the angel of the Lord called to him from heaven and said: “Abraham, Abraham!” And he said: “Here am I”. And he said: “Do not lay your hand on the lad…”

The arm raised to kill is of course very different from that of Cain. Abraham’s sacrifice goes far beyond those of Abel or of Noah. He was willing to show obedience to the will of God by offering ‘his only begotten son’; and Isaac, who carried his own wood to the altar, was interpreted as a ‘type’ of Christ, who carried his own cross to Calvary.

On the other hand, this prefiguration of the Crucifixion falls well short of its fulfilment, because the Gate to Paradise would be reopened only when the son of God offered himself as a conscious victim.

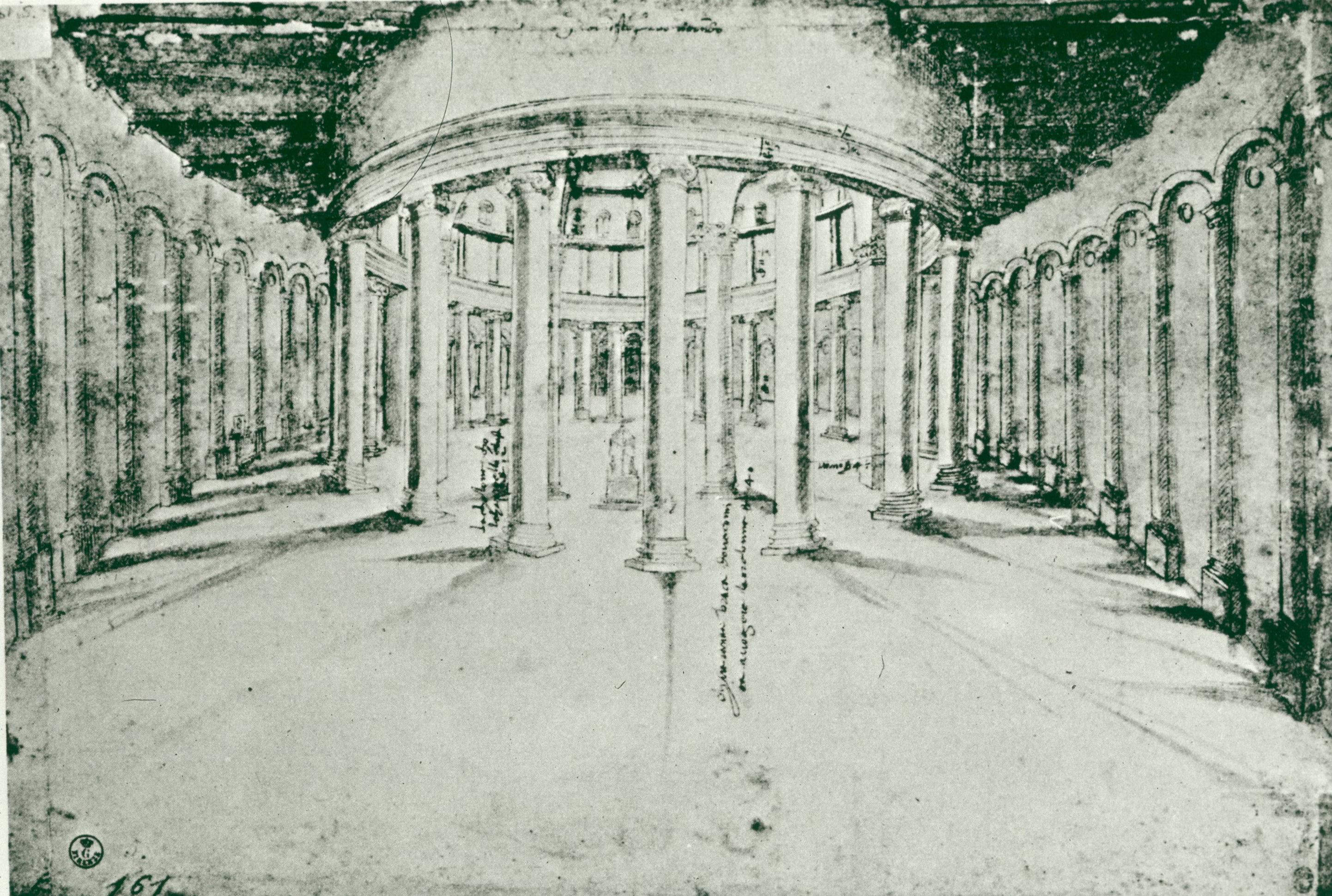

We move forward eighty years in the biblical narrative, and from pictorial conventions that were still essentially medieval, to one of the most beautiful and celebrated examples of a Renaissance urban setting, drawn in accordance with Alberti’s rules for perspective.

(The floor is duly marked out in paving stones, and the orthogonals converge on a single vanishing point. The arcades are correctly foreshortened; and the architecture itself is classical in its aspirations, with rounded arches, and proper entablatures supported by pilasters with Corinthian capitals).

The human figures are at last properly scaled, both in relation to the architecture and in relation to their distance from the picture plane. (When people of the same height are standing normally on the same ground, their eyes will all be at the same level, however distant they may be.) Everything breathes proportion and harmony—which is just as well, because there are no fewer than seven different episodes taking place within the same frame.

The women in the left foreground—one of Ghiberti’s most enchanting groups—are attending an elderly lady, barely visible in her bedroom behind, in a scene that deliberately echoes pictorial conventions for the Birth of the Virgin and the Birth of John the Baptist. It shows us Isaac’s wife Rebecca, herself barren for many years (like Sarah before her, and Anne and Elizabeth after), who is being brought to bed of twin boys, Esau and Jacob.

The twins’ appearance, you remember, was as different as their temperament, Esau being ‘hairy’ and ‘a hunter’, while Jacob was ‘smooth’ and ‘dwelt in tents’. You may remember too that their quarrels began even in the womb (as Ghiberti shows us in an earlier scene (top right) where Rebecca prays for help, and Jehovah appears to her, prophesying that ‘two nations are in your womb…divided…and the elder shall serve the younger’).

The scene in the middle (limited to the two diminutive figures) illustrates the first recorded clash between the two brothers, when Esau, returning famished from a day’s hunting, agreed to sell his birthright for a ‘mess of pottage’. This act of folly was later understood as a ‘type’ of man’s rejection of God’s grace.

The four remaining episodes in the panel are all parts of the story in which Jacob cheats Esau of his father’s blessing as well—not a very edifying story, at first sight, but one which had a special significance for the ‘younger’ Christian community.

Isaac, his eyes now dim with old age, sent Esau ‘to hunt game…and prepare for me savoury food, such as I love, that I may eat and bless you before I die’.

Esau duly departs with his bow and quiver full of arrows (top right, in the detail).

Rebecca, meanwhile, has overheard. She tells Jacob to kill ‘two good kids’ (you see him handing them over), and from their dark meat she prepares a ‘savoury dish’ tasting like game.

She then spreads the kids’ skins over Jacob’s smooth neck, in order to deceive blind Isaac’s hands, and in an agony of suspense, she watches while young Jacob receives his father’s blessing, a blessing which includes the words: ‘Be lord over your brothers,…nations shall bow down unto you’—words which, by now, need no further commentary.

We pass from the fifth panel to the sixth, where we come to another architectural setting.

This is such an absolute tour de force that it could still take Giorgio Vasari’s breath away one hundred years later; and it may have been inspired by a contemporary drawing of the ancient round church of St. Stephen in Rome.

In any other company, of course, than that of the dominant Rotunda in the centre, one would be bowled over by the foreshortened buildings on the left.

This panel shows four scenes from the life of Joseph.

Joseph, you remember, was Jacob’s son, born to his first wife, Rachel, in her old age, and hated by his elder brothers, who were born to other wives.

In the diminutive scene placed on top of the ‘mini-Colosseum’, the brothers have just taken their father’s favourite from the well (where they initially planned to leave him to die), stripped him of his ‘coat of many colours’ and are selling him to a group of passing Ishmaelite merchants, who will take him to the land of Egypt and re-sell him there.

The price was twenty shekels of silver, and the episode was regarded as a prefiguration of Christ’s being sold for thirty pieces of silver.

That story is told in Genesis Chapter 38, and Ghiberti now leaps over four fascinating and well-known chapters to reach the point after the end of the seven years of plenty, which had been foretold by Joseph in his interpretation of Pharaoh’s dreams.

During those seven years, on Joseph’s orders, the Egyptians had stored grain in huge granaries, of which our rotunda is one.

In short, we have come to the seven lean years, during which the grain would be distributed to the otherwise starving population.

It is the work of distribution that occupies both the middle ground and the foreground to the right, where, in another marvellous group, we see Joseph himself supervising, a youth bracing himself to receive his sack, a mother turning away with a bundle on her head, while a little boy hugs just as much as he can carry.

Among those who came for the ‘famine relief’ were Joseph’s elder brothers, who naturally failed to recognise Pharaoh’s chief minister.

Joseph accused them of being spies. He seized Simeon as a hostage and demanded that the others should return to Canaan and come again bringing their ‘youngest brother’ as a proof of their good faith (Benjamin had been born, to Rachel, after the news of Joseph’s apparent death).

The brothers do indeed return with Benjamin and are well received. But when they are ready to set out with their provisions, Joseph gives orders that a silver cup should be hidden in their grain sacks, and he then has them arrested for stealing the cup.

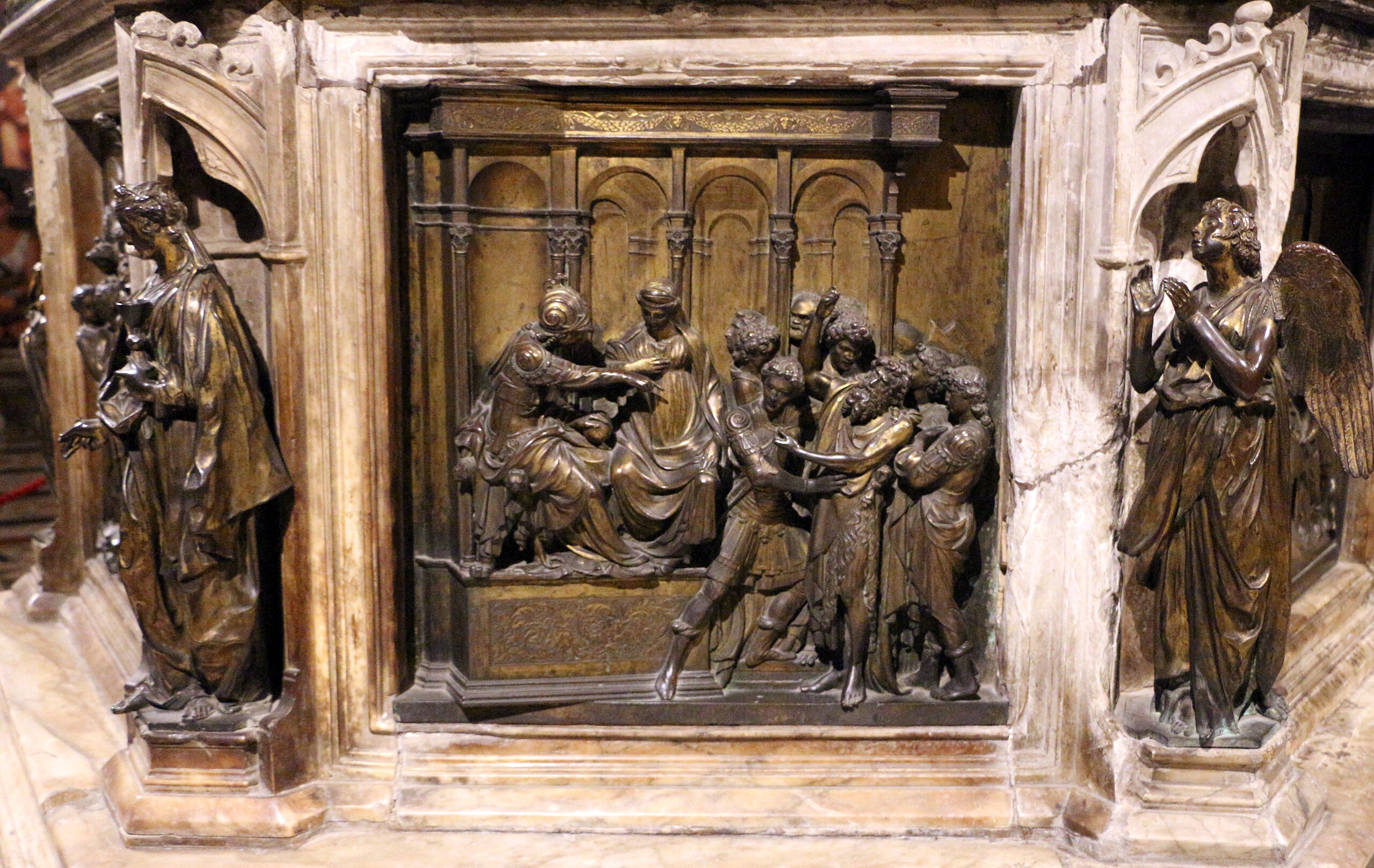

This superb detail shows the moment when the prisoners are brought before the bearded magistrates. You can see the officer stepping forward, the cup in the sack, little Benjamin, and the brothers, who are desperately ‘tearing their garments’ and protesting their innocence (all except the tall, languid youth on the right).

As you know, however, this story did not close with a grisly revenge, but with forgiveness and reconciliation.

Joseph revealed his identity. He forgave his penitent brothers; and ‘[he] fell upon his brother Benjamin’s neck and wept; and Benjamin wept upon his neck’.

(Apart from being a sublime story of brothers reconciled, the episode is important historically, because it represents the moment when Jacob and his descendants—the ‘children of Jacob’, alias the ‘children of Israel’—were invited to settle in Egypt, where they would eventually be enslaved.)

In Christian exegesis of the Bible, the historical enslavement became perhaps the single most important moral allegory of the soul’s bondage to original sin.

The seventh panel contains many deliberate reminiscences of earlier scenes, including flowing water (very prominent, this time, on the left), trees and tents, a mountain climbing towards the right with a patriarch placed on the summit, and the appearance of Jehovah, wearing the same hat that he wore for the scene of the Expulsion, accompanied once again by the angelic host. It is in fact a summation of all that has gone before.

The main subject of the panel is the day described in Exodus 19 and 20, on ‘the third new moon after the people of Israel had gone forth from the land of Egypt’.

Israel was ‘encamped before the mountain’ in the wilderness; Moses ascended the holy mountain of Sinai; and the Lord appeared, to the accompaniment of ‘thunders and lightnings…and a very loud trumpet blast’, to give Moses the Tablets of the Law—the Ten Commandments.

This is the single most important stage on the path to the Atonement.

Mankind now has a written law, replacing the oral pacts made between God, Noah and Abraham; a written law that would remain in place—accepted by Christ himself—until the proclamation of the new, evangelical law in the Sermon on the Mount, of which the scene is a ‘prefiguration’.

The smaller group on the extreme right of the foreground (raising their arms in agitation to the tree and the mountain) are the people of Israel, who ‘stood afar off’, and ‘were afraid and trembled’ when ‘they perceived the thunderings and the lightnings and the sound of the trumpet’.

The young man in armour, crouching, is Joshua, the heir apparent, who will be the hero of the next panel. He had accompanied Moses to the Mountain and is now overpowered by the transfiguring brightness of his master’s face as he returns with the Tablets of the Law.

The earlier scene, represented on the left of the panel, is almost equally important in the conceptual scheme.

The waters are those of the Red Sea, which had miraculously ‘stood’ and ‘parted’ to allow the fugitive Israelites to cross on a dry strip of land, and is still turbulent after it has swallowed up the pursuing Egyptian army.

The women, safely on the east bank, are those who danced when ‘Miriam the prophetess, the sister of Aaron, took the timbrel in her hand’ and sang to them a song of triumph.

We pick up the narrative in Chapter 3, where our hero—pictured on his chariot, bearded, helmeted, holding his trumpet—orders the priests who are carrying the sacred Ark of the Lord containing the Tablets of the Law to cross the boundary of the Promised Land, which was formed by the River Jordan.

The river was in flood at the time, but ‘when the feet of the priests bearing the Ark were dipped in the water…the waters coming down above stood and rose up in a heap far off…and all Israel pass[ed] over’ on dry ground.

Jesus himself would later be baptised in the Jordan by John the Baptist (the patron saint of Florence). So, it will be no surprise that the miraculous crossing over the Jordan was linked, typologically, to the previous crossing of the Red Sea, as another very important prefiguration of the sacrament of Baptism.

The scene on the other side of the foreground illustrates the chapter that follows.

Joshua gave these orders:

‘Take twelve stones from out of the midst of the Jordan,from the very place where the priest’s feet stood…

and lay them down in the place where you lodge tonight.’

(In the middle of the panel, Ghiberti duly depicts ten of the twelve pavilions where the twelve tribes of Israel ‘lodged that night’.)

The last episode—at the very top—tells the story of the first miraculous victory of the invading Israelites over the indigenous population, when, in the words of the spiritual, ‘Joshua fit the battle of Jericho, and the walls came tumbling down’.

This triumph was all ‘done by numbers’, you remember. For six days running, the whole army marched once round the walls of Jericho to the continued sound of trumpets. On the seventh day, seven priests, with seven trumpets, carried the Ark seven times around the walls, followed in silence by the army. After the seventh circuit (I return to the words of the spiritual): ‘Joshua told the people of Israel to shout, / and the walls came tumbling down’.

Despite such familiar features as tents, and trees, and complex groups of figures in high relief arranged across the foreground, the composition of the eighth panel as a whole is very different from its predecessors, thanks to the massive walls of the city of Jericho, which extend right across the top of the panel, and also to a second frieze of figures in front of the walls.

Ghiberti will not leave Jericho and Joshua without their visual counterparts, however, which are to be found in the following panel, in the lowest tier of the narratives, now more or less at the viewers’ eye level.

Here again we see a commander on a chariot; the advance of an army, rocks and trees in the middle ground, and a city behind a wall extending across the skyline.

The story is perhaps the single most famous example in the Bible of a victory granted by God, against all the odds, to the weak and the defenceless who put their trust in him.

The city this time is Jerusalem, the commander is Saul (his name is on his chariot) and what we see in the foreground is the climax of the story of David and Goliath.

The unarmed shepherd boy David has taken five stones from the brook (on the left in the foreground) and using his sling he has struck the giant down. Now he seizes Goliath’s own scimitar and energetically slices off his head, while three fully-armed and fully-grown men look on in wonder and admiration.

In the broad middle band of the panel, Ghiberti indulges himself in the representation of a single, accelerating sweep of action, in ever deeper relief. Foot-soldiers enter quietly, marching in front of the calm steeds of Saul’s chariot. Then the cavalry charge, slashing with short swords. The defenders resist vigorously, using dagger and javelin in the ensuing melee (as this detail shows): and a tall young spearsman with a huge lance, almost a pike, anticipates the swing of his opponent’s battle-axe. Finally, however, the first of the Philistines, an older man, drops his weapon, clings to his shield and turns in flight.

This is certainly the most animated of all the many figure groups we have seen, and it provides the maximum contrast to the tenth and final scene, which deals not with war but with reconciliation, and is the only panel to represent just one unified scene.

It is the only one, too, where virtually all the figures are onlookers, concentrating our attention on the central event.

The astonishingly assured architectural setting, which is almost perfectly symmetrical, is that of the newly completed Temple of Jerusalem, constructed, here, in the form of a Christian basilica with nave, aisles and apse, combining Gothic arches with classical details in what one could interpret as yet another kind of ‘reconciliation’.

Exactly in the centre of the architectural composition, framed by the arch of the nave (which is foreshortened centrally), standing in front of the altar (presumably containing the Ark and the Tablets which we saw earlier), we see the son of David, namely King Solomon.

Solomon is bearded like the earlier patriarchs, whose authority he has inherited, and he has just renewed Israel’s pact with Jehovah. He clasps the hand of the Queen of Sheba, who is dressed like Mary, and whose gesture of submission expresses the words which she speaks at the end of her visit to King Solomon:

‘Behold, the half was not told me; your wisdom and prosperity surpass the report which I had heard…Blessed be the Lord your God.’

The Queen’s words, together with the fact that she had journeyed from the East and her gifts included spices and gold, led to her visit being interpreted as a prefiguration, a ‘type’, of the adoration of the Three Wise Men.

This in turn had particular importance, because the Journey of the Magi was seen as the first recognition that the Jewish Messiah was to be the Saviour of all mankind—not just Jews, but also pagans, ‘gentiles’—including the Florentines, who would be baptised behind the paired doors we have been studying,

That is the main meaning. However, when the clasping of hands in reconciliation is interpreted in the light of the political context of the time, it becomes very probable that Ghiberti intended a reference to the sustained attempt to reunite the Eastern and the Western churches, Catholic and Orthodox, to counter the threat from the Turks in the 1430s—an attempt which culminated in a joint Council of the churches, which transferred itself from Ferrara to Florence in the year 1439.

If you would like to find out more about the Council of Florence, and more about the Three Wise Men, you may go the final lecture in this series, where you will be able follow them (as they followed their star), through many centuries in Western Art: from mosaics in Ravenna, to manuscripts in England, to a Florentine altarpiece and, finally, to the walls of a chapel in the new palazzo which the Medici family built in the 1440s.