Gozzoli: The Journey of the Magi

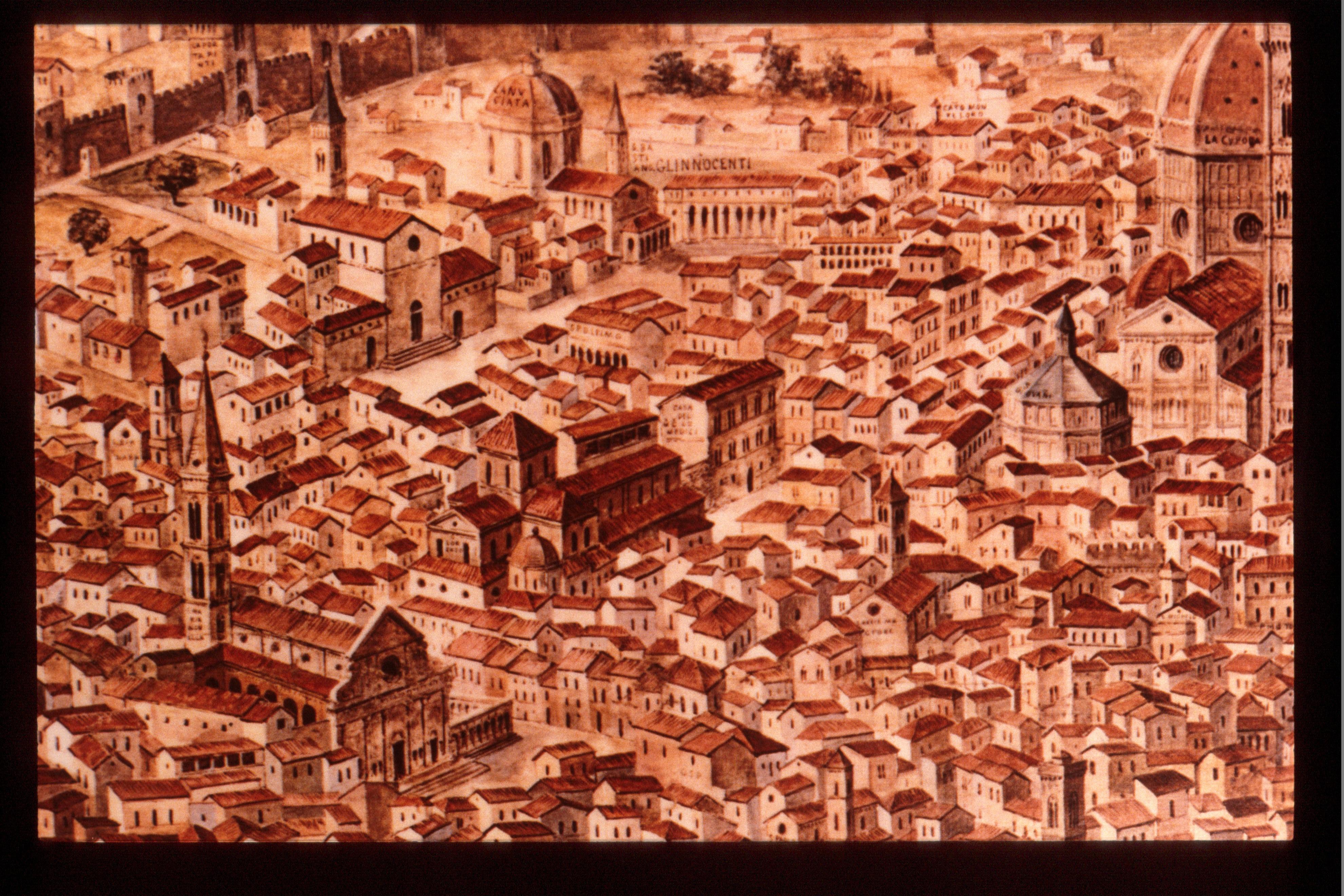

Fig. 1 shows the famous view of the city of Florence, done in about 1480, that should by now be familiar; and below it (fig. 2), I have picked out a detail showing the area of the city, to the east of the cathedral, where a family of bankers called the ‘Doctors’ lived—the Medici. This was the quarter they built, or caused to be built. It contains their palazzo, the Church of San Lorenzo, where the family are buried, and the Convent of St. Mark, where Cosimo di Medici used to retire and pray, and which contains a lovely altarpiece by Fra Angelico. In this lecture, we shall be looking at work done by the principal assistant of Fra Angelico, a Florentine called Benozzo.

Benozzo Gozzoli would have been about forty years of age when he received the commission, in 1459, to paint frescos on the walls of the Medici family chapel. This was a very typical commission, as we saw with Giotto and Masaccio and their fresco cycles for the chapels of the Bardi and the Brancacci families. But in this case there was a significant difference: the chapel in question was not in the local church, but inside the magnificent new townhouse that the Medici had been building, and which was approaching completion in the 1450s:

Notice, by the way, the emblem of the Medici on the corner of the palazzo, seven balls forming the pattern you can just make out in the photograph. The chapel itself lies in what would later be called the ‘noble’ storey, piano nobile, and is shown from two corners below:

It is a fairly small room, in which the main area, within these four walls, forms almost a square, about sixteen feet by eighteen feet. There is also, as you can see, a smaller rectangle, opening up from the front wall, to accommodate the altar.

This altar already had a magnificent altarpiece, painted in the early 1450s by Filippo Lippi, showing the Madonna adoring the infant Jesus on the ground, in the presence of the Father and the Holy Ghost, Saint Bernard of Clairvaux, and the young John the Baptist.

The seats in the chapel are veneered, the floor is inlaid, and the ceiling is splendidly coffered. There is, alas, one important detail which is missing from the photograph above: in the centre of the main ceiling, and also in the centre of the smaller altar-ceiling, there is a golden star, which would catch the faint light coming from the two oculi.

Gozzoli was asked to decorate three walls surrounding the altar with a fresco that would represent the journey of the Magi, who were to be imagined as ‘following yonder star’ in the ceiling. They would go right round the walls, until they came to a halt where the star had stopped in the chancel in front of the altar, where they would find Mary in the adoration of her baby (cf. fig. 7). Gozzoli achieved this goal by placing one of the Three Wise Men in the centre of each of these walls, and by linking them by means of pages, grooms and attendant lords-on-horseback, so that all three walls can be read as one continuous pageant, one continuous cavalcade entering the chapel on one side, and leaving on the other.

In the second half of this lecture, we shall have a close look at this pageant and enjoy a host of lovely details. When you have seem them, you will understand why tourists who visit the little chapel always enjoy themselves, and tend to remember what they saw far more clearly than many of the other sights that they packed into a week’s holiday in Florence.

Benozzo, however, is not one of the Great Ones in the history of art, and he hit the jackpot just this once. His career does not require much by way of explanation, and (unlike in the previous lecture) there is virtually no story to tell. So I am going to spend the first half of this lecture talking about the representation of the Three Wise Men in earlier centuries. I hope this will be enjoyable in itself; and although I shall confine myself to representations found in Italy (about ten in all) you will see enough to enable you to distinguish what Gozzoli took over from tradition from what is relatively new.

First, however, I must remind you of the bones of the Gospel story. So let us go back to the Gospel of St. Matthew (the only source):

‘Now when Jesus was born in Bethlehem of Judea in the days of Herod the King, behold, wise men from the east came to Jerusalem, saying, “Where is he who has been born King of the Jews? For we have seen his star in the east and have come to worship him”.

‘When Herod the King heard this…he enquired of them where the Christ was to be born. They told him, “In Bethlehem of Judea”.…

‘Then Herod…sent them to Bethlehem, saying, “Go and search urgently for the child, and when you have found him bring me word, that I too may come and worship him”.

‘When they had heard the King, they went their way, and lo, the star which they had seen in the east went before them till it came to rest over the place where the child was. When they saw the star, they rejoiced exceedingly with great joy; and going into the house they saw the child with Mary his mother and they fell down and worshipped him. Then, opening their treasures, they offered him gifts, gold and frankincense and myrrh. And being warned in a dream not to return to Herod, they departed to their own country by another way.’

As a romance or legend, the story has everything: sages from the east with the power to read the stars; a journey; a council scene with a wily opponent; a miraculous star that actually leads the way; and the offering of exotic gifts to a baby who is also the Saviour of the World. From a purely religious point of view, the episode was popular, too, because the whole story, and the gifts in particular, seem to cry out for a symbolic interpretation.

Most importantly, the moment of the adoration was interpreted as being the first ‘manifestation’ or ‘appearance’ of Christ to the ‘gentiles’ (that is to the non-Jews). This is why the feast day of the Magi on January 6th is known as Epiphany, which is simply the Greek word for ‘appearance’. If we turn to the Golden Legend, the widely read thirteenth-century compilation of reading matter for every day of the liturgical year, and if we look at the entry for Epiphany, we find the author quoting St. Bernard of Clairvaux, who offers a very literal and practical attitude to the meaning of the gifts:

‘The gold was intended to give testimony of the poverty of the Blessed Virgin; the incense to purify the smell of the stable; and the myrrh to give strength to the limbs of the child by driving out the worms from the entrails’.

It was more usual, however, to dwell on the symbolic or the allegorical meanings. Notably (as the Golden Legend also reports), ‘these three gifts signified the royalty, the divinity, and the humanity of Christ. Because gold is used for royal tribute,…incense for divine worship,…and myrrh for the burial of the dead’.

My earliest Italian example of their ‘epiphany-in-art’ anticipates the Medici Chapel by representing the three sages at the head of a long procession. To find them you have to go to Ravenna on the Adriatic Coast, to the Basilica of Sant’Apollinare Nuovo, where a single mosaic runs the length of the whole nave, showing a procession of virgins, who are advancing to adore Mary and her child, enthroned between four angels.

The Magi lead the procession, carrying large bowls, which resemble soup tureens, containing their gifts. The mosaic is from the middle of the sixth century, and you will see that the number of Magi, left unspecified by St. Matthew, has been fixed at three, that is to say, one bearing each gift. By this time, too, they have acquired names: Caspar, Melchior, and Balthasar (which is the Latin form of Belshazzar). Further, they have become representatives of the three ages of man: middle, young, and old:

In later centuries, they would also be interpreted as representatives of the three known continents—Europe, Asia, and Africa—and later still, one of the three would be portrayed as black. It is also worth noting that the layout of the figures is derived, in general terms, from those in a low relief sculpture of a Roman triumph - and, specifically, from reliefs showing pagan nations approaching to offer homage to a female figure of Victory. It is from this source, ultimately, that we get the very oriental dress of the Magi at Ravenna, with their Phrygian hats, brightly ornamented clothes (contrasting with the white of the virgins and the angels) and the very un-Roman trousers or breeches—admire especially the leopard-skin trousers with spurs!

I jump forward now a good seven hundred years to the thirteenth and early fourteenth centuries, to show you how the Three Wise Men appear—or ‘epiphanise’—in the works of three great Tuscan artists: the painters Duccio and Giotto, and, before them, the sculptor Nicola Pisano.

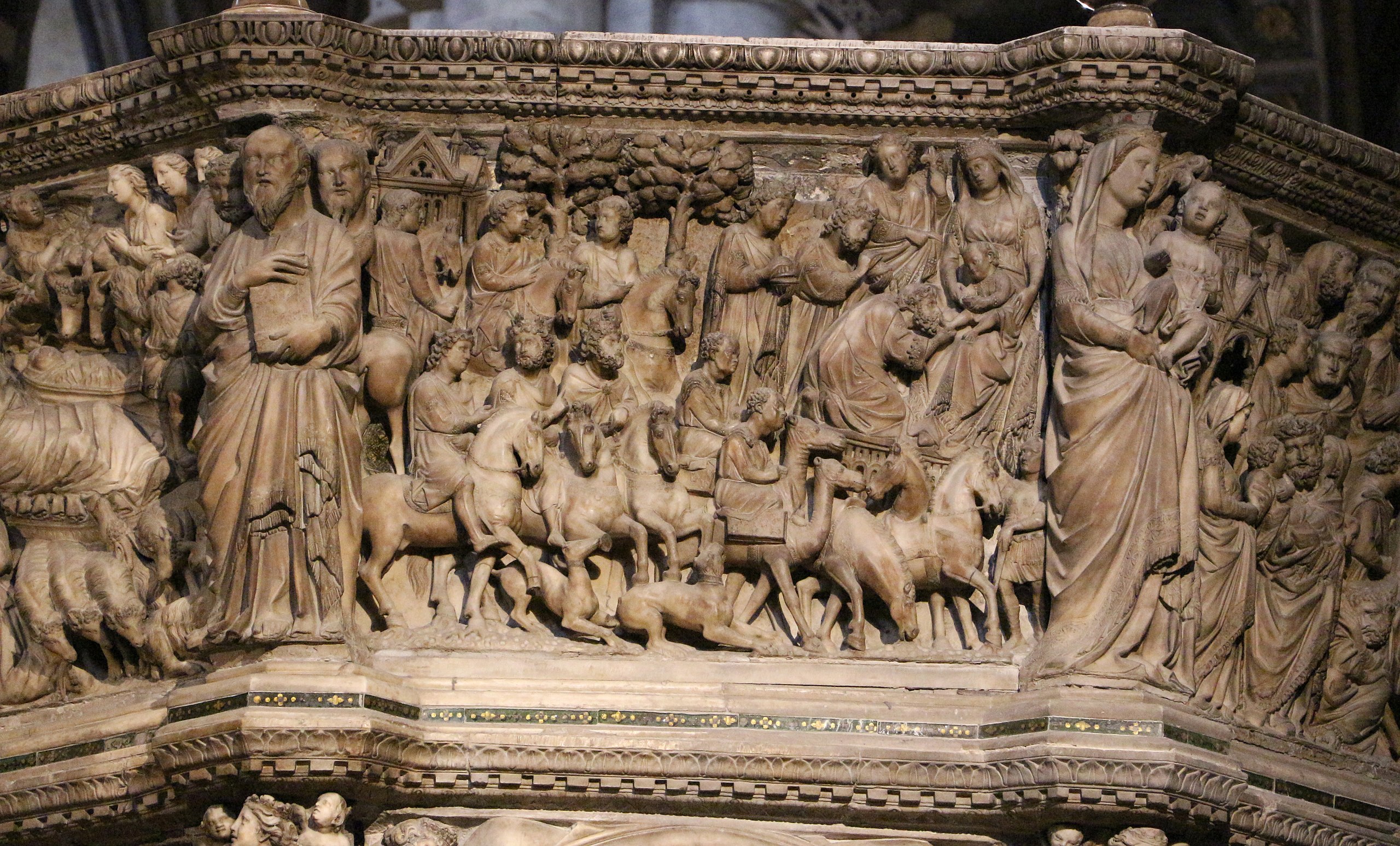

I am able to make this jump because Nicola carved two versions of the scene, and revealed himself of something of a Janus, who with one face looked back to the remote Classical past, and with the other, far into the future. His first attempt is to be found on the panels of the marble pulpit which stands in the Baptistery next to the cathedral and the leaning tower in Pisa, from which I have picked out the panel that concerns us now:

Here, Nicola was clearly inspired by the relief sculpture of ancient Rome, and particularly by some of the many sarcophagi that had been, and still are, preserved in the Camposanto at Pisa. Mary is flanked by an angel and by Joseph. She sits regally, full front, as at Ravenna—every inch a Roman matron. Two of the Kings (I call them ‘kings’ because they are always crowned by this time in Christian art) are kneeling in profile, as we saw at Ravenna, but they are less clearly distinguished in age, and are kneeling rather than advancing. Young Melchior stands behind, counter-balancing Mary, as sturdy as a statue of Hercules, inclining his head in reverence. The antecedent journey is indicated, very economically, by the heads of three horses, one for each rider.

The Pisan panel was carved in about 1260. Only a few years later, in the 1270s, Nicola was working on a second huge pulpit, this time for the cathedral at Siena.

At first sight it looks very much like the one at Pisa, but as soon as one focusses on on the relevant panel, one becomes aware of a totally different, Gothic sensibility. There is one angel on duty in the stable, but no Joseph. Mary is dressed in contemporary costume, while the crowned Kings are arranged in the order young, middle, old, and they are standing, inclining, and kneeling, The oldest King kisses the feet of the infant in homage, as had become prescribed by the tradition.

However, the greater part of the panel shows the journey of the Kings, who are riding on superb horses, with two regal greyhounds beside them. They are followed by three mounted attendants who are wheeling their horses, and they are preceded by other attendants, on camels, while their grooms bring the packhorses to a halt in the front of the panel.

We move forward forty years to 1310, when Duccio painted the panel in fig. 16, no more than eighteen inches high, as part of the predella for his gigantic altar piece which was going to stand only twenty yards away from Nicola’s pulpit in Siena Cathedral.

Here, everything is restrained and balanced. Duccio combines the cave, which was traditional in eastern or Byzantine representations of the Nativity, with the stable or barn, which had been favoured in the pictorial tradition of the Western Church, to form a central arch that frames the figures of Balthasar and Melchior. They exchange glances, as do the horses and the two pairs of grooms, while the two camels use their superior height to look down their long noses to the very heart of the scene; old Caspar arches his back while kneeling, so that he may look up to the child whose foot he is kissing, while Jesus holds out his hand in blessing.

The very deep blues and reds and the dark gold leaf on the little panel make a superb foil to the pastel shades of the following fresco, about six feet square, which you will recognise as being by Giotto, and as coming from the middle range or tier of the Scrovegni Chapel in Padua:

As always, Giotto tries to break away from a simple frieze—that is to say, a composition in which all the figures and all the action are parallel to the picture plane—by setting his ‘Dutch barn’ on a gentle diagonal, while the figures of Mary, Joseph and the angels are set on an even steeper diagonal, extending backwards into the space which is created, inside the picture, by the foreshortening of the barn, which assumes the pictorial function of a canopy to throne. Caspar kneels, as in the earlier imge, but with his eyes lowered. The figures that stick in the mind are young Melchior, massive and stock-still in his heavy, bell-shaped, un-patterned cloak, the groom reaching up to restrain the camel, and, in the sky, the star—which is also present in the Duccio—but which here is represented from the life as a comet: Halley’s Comet had appeared in the year 1301, shortly before this fresco was painted in around 1304.

Each of the four Adorations I have shown you so far were integral parts of a narrative cycle, and subordinate to the needs of the whole. The four I am about to show you—from the period between c. 1380 and c. 1435—were, on the other hand, independent paintings. Thus it is hardly surprising that they should be more elaborate, with a great many participants, and much local detail; generally speaking, they are following the lead given by the second of Nicola’s panels, the one from Siena.

The earliest of the four is by a Sienese, Bartolo, son of Fredi, and is about six feet high; while the latest is a panel, about two feet high, by the northern artist Stefano da Verona. Despite all the differences in size, quality, local traditions and date (they are separated by fifty years), the two pictures do share a number of generic features which art historians like to gather together under the label ‘International Gothic’, and which we need to recognise if we are going to try and ‘place’ the art of Benozzo Gozzoli.

Very roughly, the compositions are strongly influenced by the conventions used in tapestries—secular tapestries, especially scenes of hunting. The stylised landscape extends to the very top of the painted surface, which is usually closed by a cluster of small buildings, or hills, or both, with virtually no sky. Most of the lower surface is typically covered by a mass of closely packed, overlapping figures, surrounded by animals and plants. The human actors are dressed in the most sumptuous costumes, very bright with elaborate patterns; the servants or shepherds may be dumpy and almost caricatured, but the aristocrats have slender, willowy bodies, very often subjected to a flattened S curve, like the sound holes on a violin.

In the highest register of Bartolo’s altarpiece (fig. 18), you can see the procession of the Kings entering Jerusalem (which has a rather pronounced resemblance to Siena) and immediately leaving the city by the lower gate, before reappearing at Bethlehem in the foreground to present their gifts, hemmed in by their ill-disciplined horses and followers, and, finally (top right) leaving for ‘their own country by another way’.

In Stefano’s little panel, you can see in addition the star, the shepherds abiding in the fields, and some hunters. The procession here is limited to two men on camels and two dogs; but the stable has its ox and ass, and a symbolic peacock. The Kings form a beautiful, lyrical group (with the S-curves very prominent); and the emphasis is on the Presentation, rather than the Adoration and Blessing.

Now let us come to Florence itself, and to two altarpieces that were painted near the beginning of the fifteenth century. The first is now in the Uffizi, and is the work of ‘Lawrence the Monk’, Lorenzo Monaco, who was a major influence on the early Fra Angelico:

It measures about three and a half feet by five, and in very general terms, the composition is much the same as in the two we have just looked at. You can make out the angel and the shepherds, Jerusalem, the hint of a procession (with one camel, one horse and one dog); then the compact mass of followers, the Three Kings (young, middle-aged and old), Mary and Jesus, the stable with an ox and an ass. The style, too, is clearly related to that of Bartolo and Stefano, although there are a few features to which I want to call attention because they either point forward to what we shall find in Benozzo, or act as a foil to his work.

Let us begin with the contrasts. The architecture here is very schematic indeed; the colours are extremely bright; the animals could hardly be less lifelike; and the human figures are even more elongated and subject to that S-curve than anything you have seen so far—all their movements seem to echo the scimitar on the thigh of the man in the foreground (fig. 21). All these features are backward-looking by the year 1420; but to set in the balance against them, there is a new attempt to express the ‘easternness’ of the visitors, not just through the scimitar and the beards (Florentines at this time were all clean shaven), but with the reasonably convincing depiction of the black follower, and the splendid array of exotic headgear—pointed, or turban-like, or peaked.

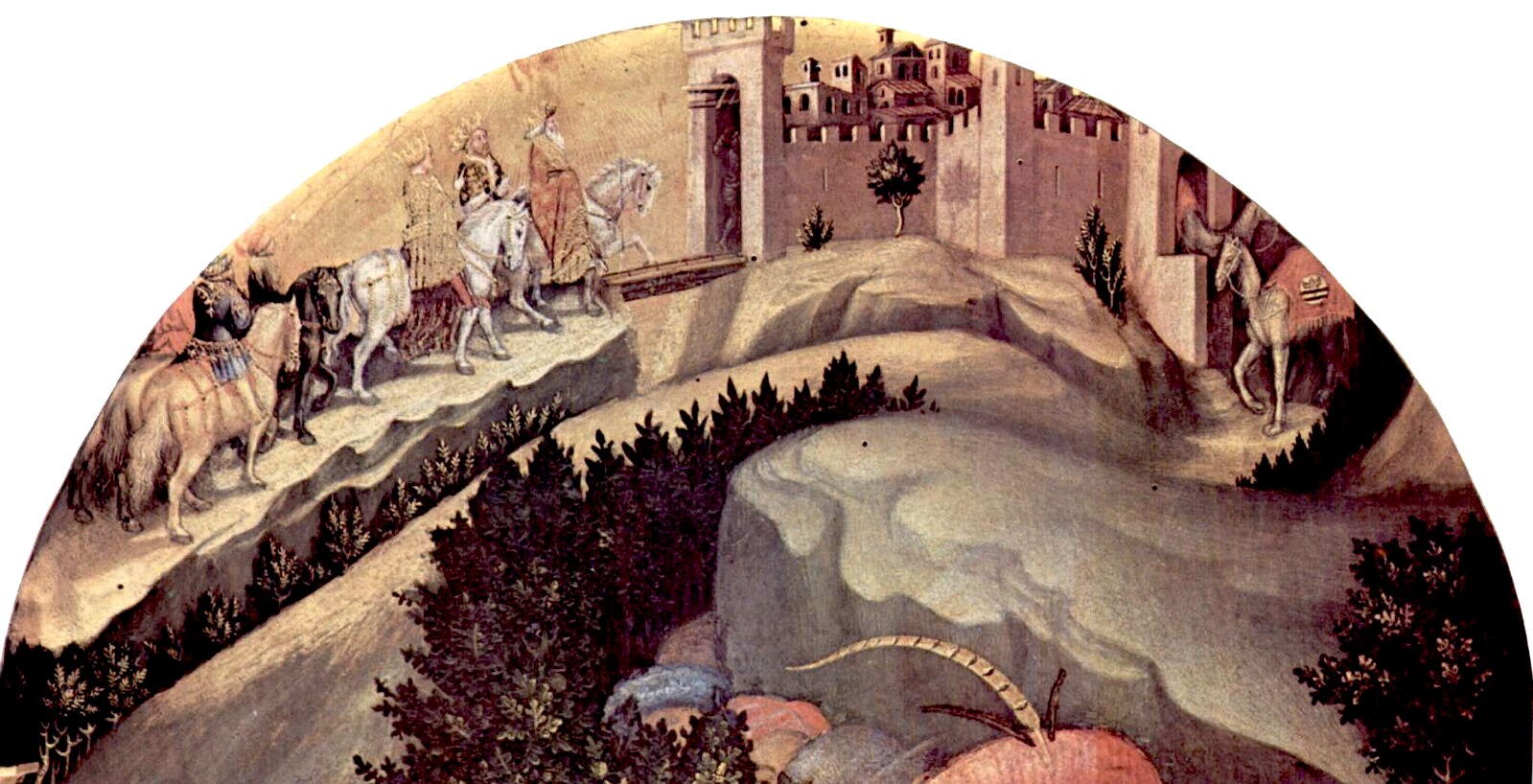

My final example before returning to the Medici Chapel, and to Benozzo, is one of the most famous images of the Magi in all European art. It was painted for a family who were the rivals of the Medici (and whose palazzo was eventually to be even bigger than that of their rivals)—the Strozzi.

It was commissioned as an altarpiece for a new sacristy in the nearby church of Santa Trinita. The artist was a non-Florentine, Gentile, from the town of Fabriano (which is in the Marches, to the west of Arezzo); and he signed and dated the work in May 1423. It is still in its original highly elaborate frame, and can now be seen in the Uffizi in the same room as the Lorenzo Monaco—but it is nearly twice as big, six feet by almost nine.

As in the Bartolo altarpiece, the story begins in the top left lunette, where you can see the ships that brought the Kings to the Holy Land and the start of their cavalcade. In between these two moments, you can just make out the Three Kings standing on a mountain, looking up at the guiding star, and shading their eyes against its brilliance.

The cavalcade then winds its way across the central lunette, before climbing towards the city of Jerusalem on the skyline. The Kings are in the centre; and you should be able to see leopards riding on the saddles of the horses before them.

A close-up (fig. 27) of the riders just behind the Kings allows us to enjoy the courtly costumes, and also the action of a man loosing his falcon, and a horse rearing up, apparently with sufficient suddenness to create a kind of ‘wind’, that ruffles the rider’s hair and sets his cape flying.

In the right-hand lunette, the Kings are seen at the very head of the column, with the unseen star flooding them with its golden brightness. Then, with a sudden change of scale and density, the cavalcade is upon us. It has been winding its way up from a sunken road on the right, and now it is now halting and milling round, with horses going both ways, and the riders looking up and down, and to the right and to the left, until the eyes of the page (the one with the huge sword, and his hose round his ankles) and the portrait heads of the donor and his son, direct your attention to the Presentation and Adoration itself:

The Presentation takes place under the intense light of the star, which has come to a halt at the porch of the stable, which is next to the mouth of the cave (now quite separate, unlike in Duccio). In the cave you can see the donkey and the ox, and the manger of a typical Nativity scene.

We ought to dwell a little on the Adoration and Presentation, if only because they are going to be totally absent from the Medici Chapel. The Three Kings are the most sumptuously dressed of all the members of the cavalcade, as you can see in the crown, hat and collar of the youngest King, who stands, rather too lackadaisically, with one finger in his belt, and his gift held rather nonchalantly between finger and thumb.

His attitude, however, acts as a foil to the middle-aged Balthasar, who is removing his crown and sinking to his knees. The sequence is completed by old Caspar, kissing the baby’s feet in homage. We are of course intended to enjoy the humanising touches among those who receive the gifts: the baby reaching to touch Caspar’s bald pate, rather than ‘blessing’ him; or the typically practical midwives, with their lovely northern Italian heads, who are examining the contents of the first pot.

But we should not neglect the things that Gentile shares with

Benozzo, or which he actually suggested to Benozzo. So, looking again at

the Kings’ retinue as they come to a halt behind them, there are far

more heads than in any version we have yet seen and they include some

vivid characterisations, especially in the juxtapostion of the noble and

the rustic—a taste which is not incompatible with a love for the

splendid headgear, whether it take the form of a FIXME

mazzocchio in red, or that of an ornamental helmet:

Even more memorable, perhaps, are the squashed, foreshortened features of the groom who kneels behind the youngest King to adjust his spur. But one could certainly argue that it is the animals that carry the day. The aristocratic greyhound in the foreground, with his golden clasp on the collar; the splendid studies of horses, of the grey and especially the dun, seen from the rear; the rocking-horse heads and bridles; and, even more delightful (and even more of a tour de force) the two monkeys who are squatting on the camel, chattering to one another in front of the pomegranates, which are splitting open, against the dark background of the leaves of the tree:

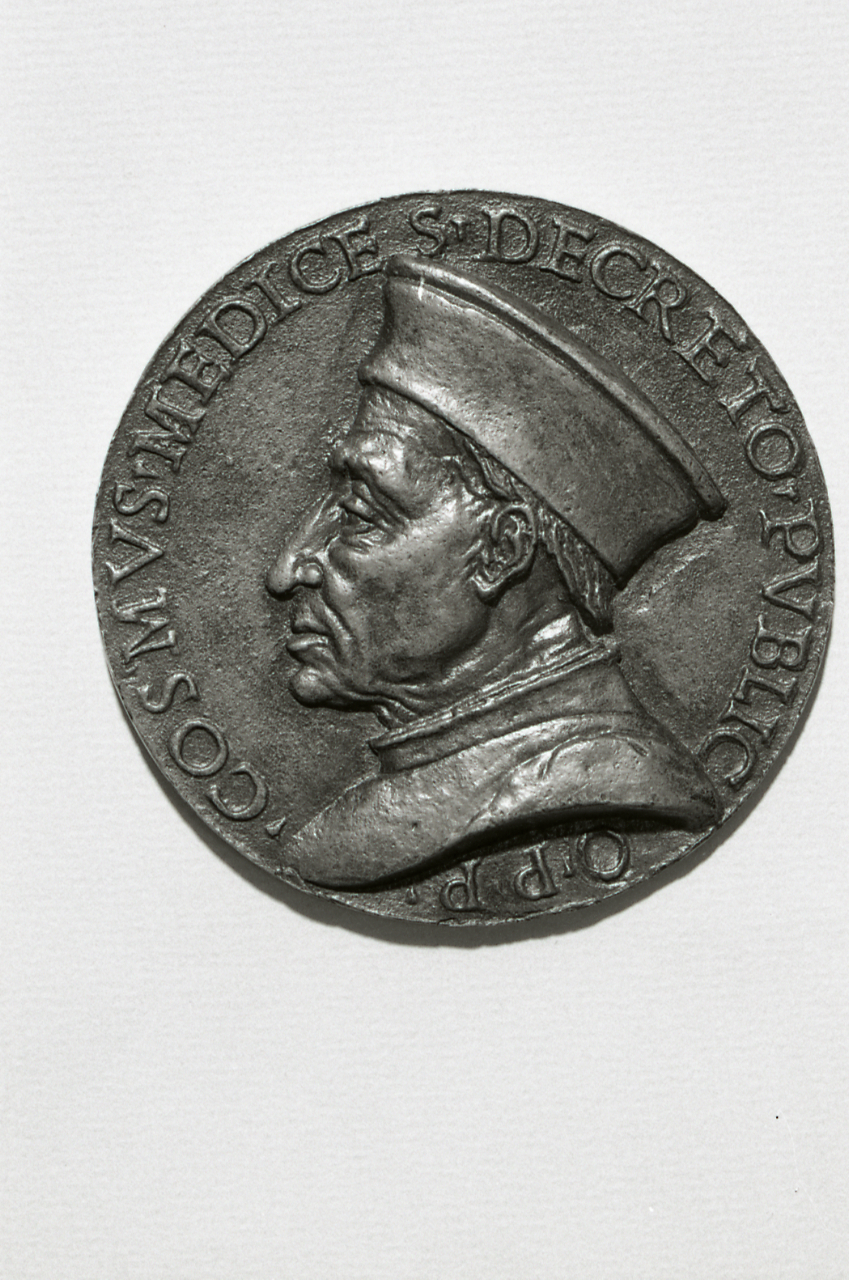

We may now leave the Wise Men in peace for a while, in order to absorb a few relevant points about the Medici themselves. The dominant figure in this period was Cosimo, who was born in 1389 and died in 1464, and whom you see below in an enlargement of a tiny portrait medal. It is the same medal which is held by the youth (possibly a Medici bastard), in the following portrait by Botticelli, and clearly served as the model for the posthumous portrait by Pontormo:

Cosimo was exiled for a time in 1432, but returned only two years later.

This time, it was the leader of the Strozzi family who had to go in to exile. Cosimo continued the work of rebuilding the Church of San Lorenzo; he started work on the new family home; and he financed the necessary building for the Dominican Convent of St. Mark, including the beautiful library by Michelozzo. In foreign affairs, he was to achieve decisive influence in the whole peninsula. He backed his old friend Francesco Sforza, a mercenary general, who had seized power in Milan in the early 1450s after the Milanese had thrown out the Visconti family, and who founded a republic there—the Ambrosian Republic. Cosimo allied himself with Milan (the traditional enemy) against the Republic of Venice (the traditional ally) in order to halt the Venetian advance inland: new boundaries between them were agreed at the Peace of Lodi in 1454 which were to remain virtually unchanged for the rest of the century.

Before this, Cosimo had been involved in papal politics through his friend Pope Eugenius IV, a Venetian who had been elected in 1431, but who had been forced to abandon Rome soon afterwards and had established his court in Florence until 1433, while he struggled against the Council of Basle and the surviving anti-pope. He is pictured below, in front of Florence cathedral in 1439, during the proceedings of a ‘summit conference’ between the heads of the Eastern and Western Churches. This ‘ecumenical’ council had been convened in Ferrara in the preceding year, but had run into financial difficulties, which were resolved by Cosimo on the condition that the delegates came to Florence, thus giving him and the city a considerable boost in prestige. It was attended not only by Joseph, the Patriarch of Jerusalem, but by the Eastern Emperor himself, the Emperor of Constantinople, John Paleologus VIII, pictured here in a famous medal profile by Pisanello—the Emperor having come to Italy in a desperate attempt to find allies to help him to check the advance of the Turks. The presence of this king from the East at the head of an exotically attired retinue obviously remained in the memory of the Medici family.

Lastly I would recall that the younger Medici, at least, clearly took delight in the aristocratic pastimes of the feudal north—banquets, jousts and tournaments, such as the one pictured below. The Medici were also patrons of a Confraternity which was dedicated to the name and the cult of the Three Wise Men. We know that members of the family regularly took part in horseback processions through the streets of Florence on the feast of the Epiphany—all of which helps to explain the choice of subject for the frescos in the Medici private chapel.

Now let us return to the Palazzo Medici, climbing the stairs up to the first floor, and entering the chapel to look into the little altar space and the rear wall.

We will spend the last part of this lecture following the cavalcade of riders behind the Three Kings, as they come in to the chapel and go right round the three sides to ride out again, without ever adoring the child or presenting their gifts.

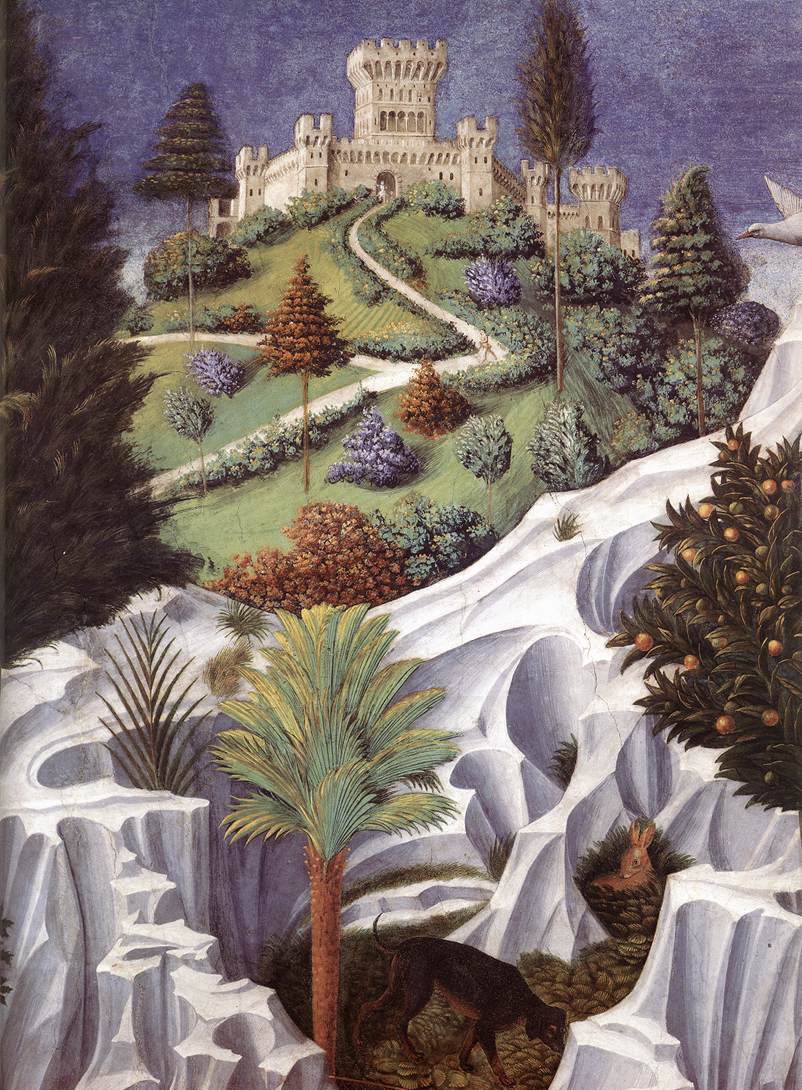

The procession begins on the wall to the right as you face the altar. It is about eighteen feet wide, and it is the most important of the three, as well as the least damaged. The first impression you receive is one that will be confirmed again and again in the details. There is an obvious, multiple debt to the tradition that culminated in Lorenzo and Gentile, in the way that the hilly landscape rises to the top of the painted surface, as in a northern tapestry; in the stylisation of the rocks; and in the treatment of the close-packed faces. But there is also a greater naturalism in local details, and a much greater sense of pictorial depth, especially to the right. The procession has just set out on this stage of its journey from the fortified manor house, set improbably high like its medieval models, but in fact a splendid piece of perspective drawing, showing the sort of fortified country residence that the Medici had built for themselves in Tuscany.

From the castle, the horsemen ride down the winding land close to highly stylised precipices. The rocks look more like a ‘rock garden’, and are either too pink or too white; the birds are far too big (at this distance, they would have to be pterodactyls!); and you can distinguish every tree trunk in the copse on the right, and in the forest on the left. Yet the horsemen are superb, the costumes are bright, and everything breathes the atmosphere of romance and fairyland.

As we come down to the left, however, where the riders are coming straight towards us, and are close enough to be recognisable, the interest shifts away from fairy tales to the Medici and to politics; because, under those red hats, and riding on those superb horses are a number of obvious portraits:

The first point to make about them is that only one identification is sure beyond any possible dispute. The figure I have picked out in the first detail, below, is a self-portrait of the artist, with his name written on his hat: Opus Benotii. The two figures on the left must be important because of their position; and there is nothing wrong with the traditional view that they are the boy Duke of Pavia, Gian Galeazzo Sforza, son of Francesco (who had been in Florence in the recent past), and the extremely tough ruler of Rimini, Sigismondo Malatesta.

The next three riders must be Medici; but one cannot be at all certain who they are. Most people have said that the first of the heads below is intended for Cosimo. The rider is plainly dressed, he is riding on a humble mule, and he is the right age. But he looks too unlike the lean-featured, scrawny-necked figure we saw on the medal portrait for the identification to be at all probable. The person with the more Roman profile behind him could be Cosimo’s second son Giovanni; and the leader is certainly his eldest son Piero. His face is very like a surviving portrait bust of Piero; and if we look at the horse and groom rather than the rider, we can see not only the Medici device of the seven balls, but Piero’s personal motto—semper—on the horse’s harness, and also embroidered on the groom’s tunic. The detail also gives us an opportunity to admire the lovely pattern of legs, both equine and human, here.

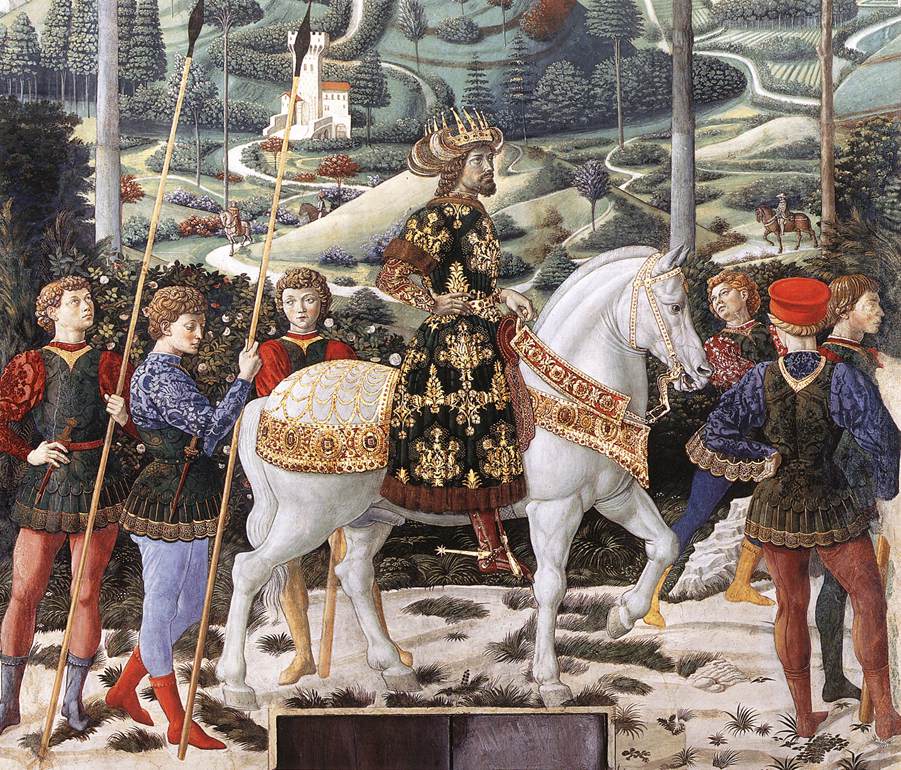

The dominant figure in the composition, however, is the youngest King:

Once again, this must be a Medici, for in the detail we can see the seven balls all over the harness. His head is framed by a laurel; and he is very much younger than the youngest of the three kings, as usually represented. All this fits well with the traditional view that it is intended as a ‘representation’ of Lorenzo, who in 1459 would have been ten years old, and was at that point the rising hope of his house. It is not really a portrait, because the face is scarcely more particularised than those of the pages who accompany him:

The pleasure of this foreground area is surely once again that of a ‘tapestry from fairyland’. Forgetting the politics and the Medici bank, we admire the crown, the curls, like those of a wig, the superbly embroidered robe and especially the sleeve. We should also look behind Lorenzo to the scenes of hunting, where a diminutive horseman with a javelin, far too small in scale for the suggested distance and accompanied by two very elongated greyhounds, is pursuing a stag with ass’s ears, who is also far too big (this indifference to relative scale being something very medieval). Meanwhile, under the shade of an exotic palm-tree, a bloodhound is tracking the hare who waits ready to spring into flight; and high above them, a huge falcon attacks a dove, above the most delightful orange-tree.

The composition is closed by the two squires who carry the young king’s gift for him, as well as his sword, and who are wheeling their horses in order to change direction on to the back wall. The image below shows how the two walls were linked to each other, though the composition is cut off to the right not merely by the camera, but by the builders in the seventeeth century, who put a new entrance in that corner.

The two squires give way in the corner to the three charming women below, who are certainly Medici, since they have Cosimo’s personal device of ostrich feathers in their caps. It was once believed they were intended as generic portraits of Lorenzo’s three sisters, Maria, Nannina, and Bianca:

It is a nice thought—but an impossible identification, since these are clearly male pages. Handsome they certainly are, though, in their brightly ‘dotted’ doublets and their red stockings; even if one’s eye does slip away from the riders to the advancing horse and its harness.

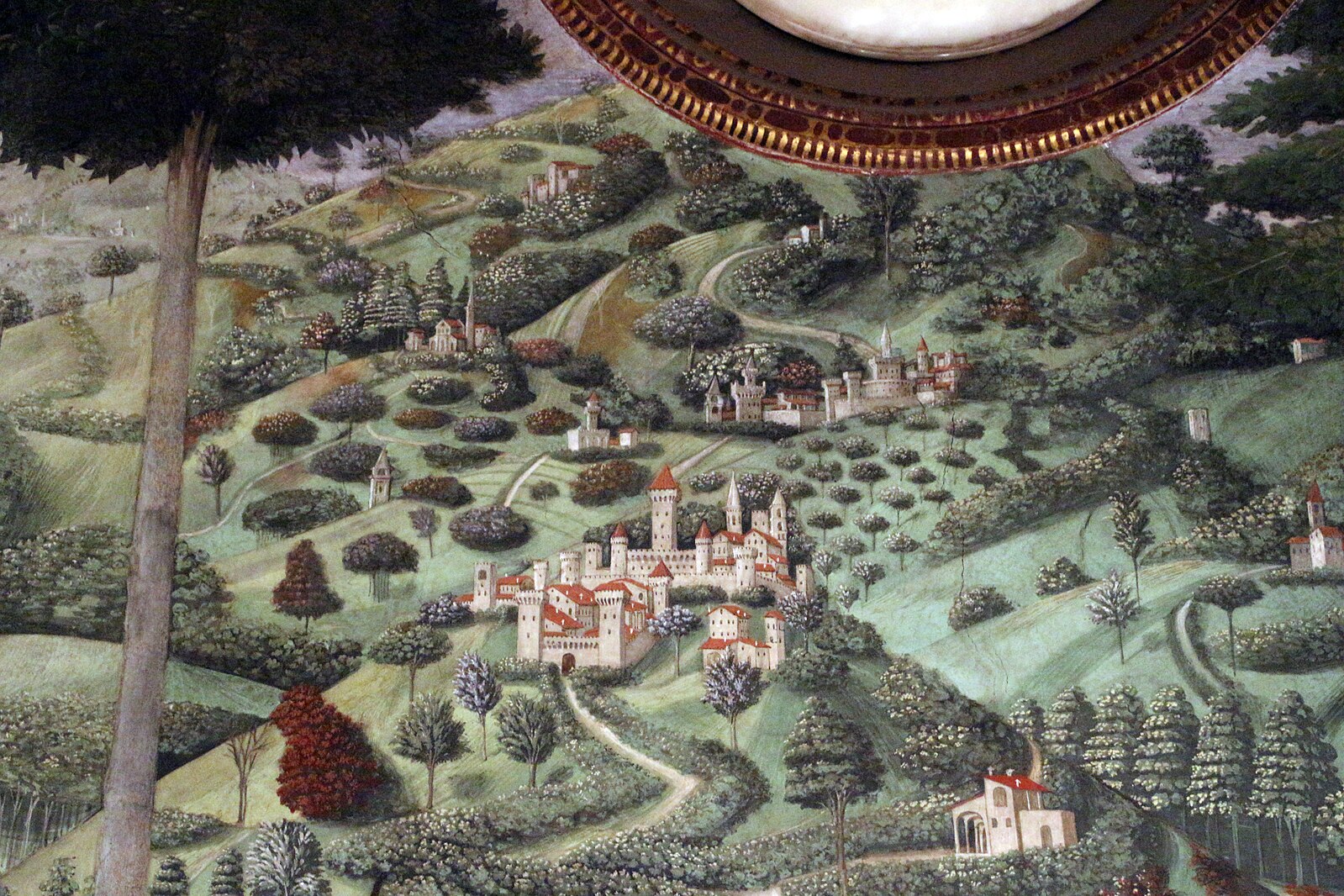

The centre of the wall is of course dominated by the proud figure of the middle-aged king, one arm akimbo and flanked by his pensive grooms. But I would like you to look first at the landscape, which contrasts with that on the first wall by being ‘hollowed out’, depicting a ‘valley’ instead of a ‘mountain’. The first detail from this scene shows a nice mixture of the stylised (with Forestry-Commission-style planting on the left, and a barely credible road), and the realistic, with a lovely stretch of Tuscan hillside in the distance. Above the heads of the grooms, we look past a distant horseman to a rising orchard; and then fantasy takes over again, with those two turretted castles perching on their hills:

Now we may come back to the foreground, taking in the white horse and the splendour of the king’s robe, before focusing on his exotic turban-cum-crown and on his features. These are usually said to recall those of John Paleologos, the Greek Emperor who came to Florence in 1439. (By the time Gozzoli painted these frescos, he had died; and his successor had been killed during the capture of Constantinople by the Turks in 1453.)

If the carving of the new entrance spoilt the back wall, it also almost ruined the left-hand wall, which I have presented below in a montage which affords a better view than one can get in the chapel:

The corner is marked by a pair of young horsemen, again very stylishly posed, and maintaining an all-round lookout. They are placed higher now, and the foreground is occupied by footmen, chief among them the handsome archer and his jogging companion. From him, we pass this ‘most unkind cut’ to the eldest king, white-bearded, dressed rather more soberly, and sitting side-saddle on a mule: this is now supposed to be an ideal portrait of Joseph, the Patriarch of Jerusalem in 1439.

The image which follows displays the whole of this right-hand part of the wall, beyond the break, alongside a detail of the main group within it. One horse turns his splendid rump on us, thus displaying his rider’s particularly lovely costume:

Our next focus, though, should be on that very young boy right at the head of the procession, his horse apparently about to spring, strikingly dressed in blue, with a leopard (or perhaps a cheetah) on his saddlebow:

Identification is not certain; but the pattern of spots on the cloth behind could be interpreted as the seven Medici balls, and it is not unreasonable to suppose that this is an idealised portrait of Lorenzo’s younger brother Giuliano, at that time aged about seven. It is Giuliano who was subsequently murdered in 1478 in the infamous Pazzi conspiracy.

There are several other obvious portraits to the right, but it would be wrong to finish on the social-historical side of the frescos. Instead, the eye should go past the portraits to the idealised faces (under various stylish hats), and up the precipitous path, following the mules, the packhorses, and the camels back in to the world of fantasy. Or we should stray back to the boy in blue with his pet cheetah, who is one of the happiest inventions in the whole chapel; just as the groom in front of him, whom we see better here, has one of the most interesting and one of the most resourceful poses of all the attendants:

He has one foot still in the stirrup, and bends down to restrain the cheetah (attached to his arm, as well as held in his hand), while the cheetah seems to look longingly at the falcon who has already disembowelled his prey. There could scarcely be a better example of Gozzoli’s finest qualities than this mixture of realism and romance.