Piero della Francesca: The Legend of the True Cross

One of the most charming openings to any story I know is that of the Tuscan children’s classic Pinocchio:

‘Once upon a time there was—“a King”, you’ll all say at once. No, boys and girls, that’s where you’re wrong. Once upon a time there was a piece of wood’—‘c’era una volta un pezzo di legno’.

This phrase could also serve as the opening of the story I shall be telling in this lecture. It is about a piece of wood; and we shall follow its adventures from parent tree to a cutting, from a cutting to another tree, from tree to a piece of timber that was twice carried by a king and itself carried one of those kings, was twice buried, was stolen by a heathen king, and rediscovered by a saint who was the mother of the first Christian emperor. So, it is a fairy-story, a story of ‘once upon a time’. It does involve a king or, rather, several kings; but the subject is nevertheless a ‘piece of wood’.

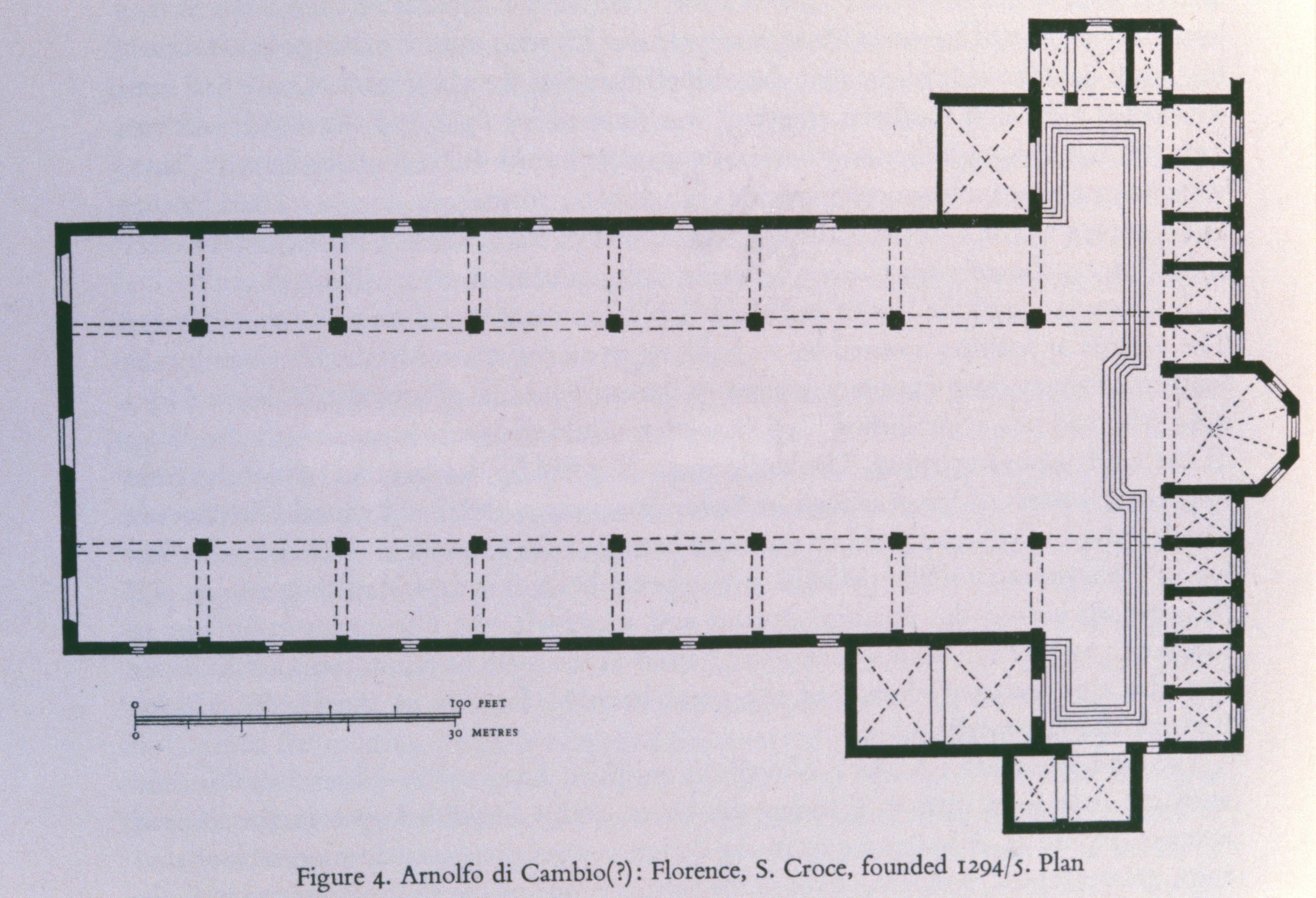

The story is told in two separate entries in the Golden Legend, in May and September; and the illustrations, or the pictorial narratives, that concern us are to be found in two Franciscan churches, one in Arezzo, the other in Florence. The Florentine church is, in fact, dedicated not to Saint Francis, but to the Holy Cross itself, the ‘Holy Rood’—‘Santa Croce’.

In both churches the frescos are in the place of honour; that is, in the presbytery or choir, the area reserved for the clergy behind the high altar of the Church.

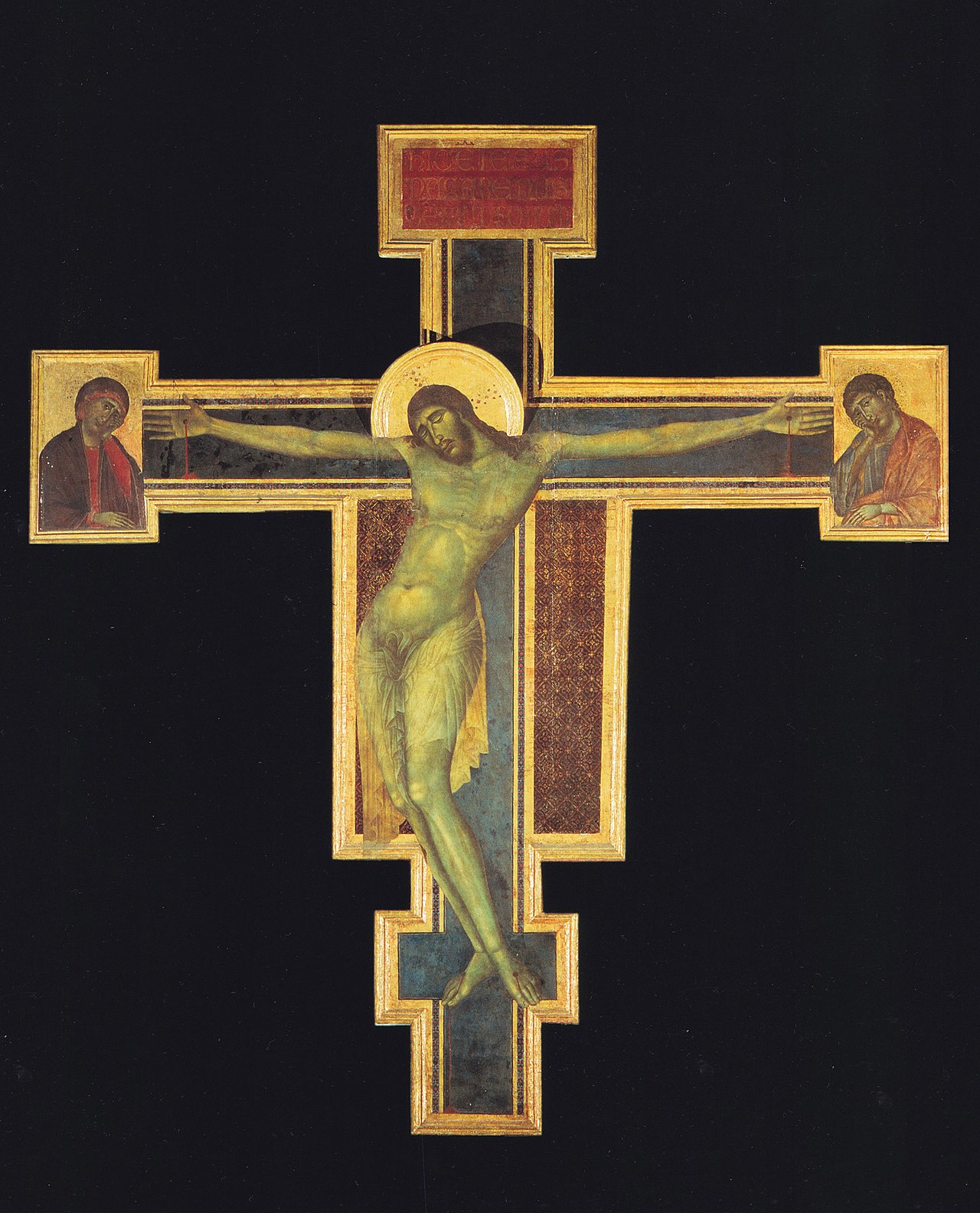

The altar itself would have been topped by a large wooden crucifix.

As far as the cross itself is concerned, all the advantage lay with Florence, because what you see here is the famous crucifix by Cimabue (this photograph was taken before the flood damage of 1966).

But as far as the frescos are concerned, the advantage lies very much with Arezzo.

The Florentine cycle was done earlier, in the 1390s, by an artist who was called ‘Angelo’ (Agnolo), the son of Taddeo Gaddi, who had been the chief assistant and heir of Giotto.

Agnolo remained fair and square within the tradition of Giotto, as you can see from this panel of the Coronation of the Virgin, now in the National Gallery, which is very closely derived from an altarpiece in Santa Croce done by Giotto and his workshop back in the 1330s.

He would have had ample opportunity to study fresco painting in further work by his father, and also by Giotto himself in the narrow Bardi and Peruzzi chapels, close to the altar in Florence.

Piero was in some sense a local or provincial painter. We know that he was employed at Rome and Ferrara, but the works he did there have been lost or destroyed.

His relatively few surviving works were done for Urbino, or Arezzo, or the little town of Borgo San Sepolcro where he was born between 1410 and 1420, and where he died in 1492. His Baptism, for example (which is now in our National Gallery), was done for Borgo.

However, it is more important to think of Piero’s apparent isolation as the consequence of a private obsession. In his Lives of the Artists, published in the 1550s, Giorgio Vasari, who grew up in Arezzo, had good reasons for presenting Piero as a supreme ‘mathematician’ or ‘geometer’.

In a moment, therefore, we shall distinguish two main aspects in his passion for geometry; but before doing so, we must take account of his purely empirical interest in the fall of light and its role in modelling bodies in relief.

Piero was not particularly interested in the warmth of colour or in surface patterns, but, rather, in volume and mass, and in how to represent the most subtle differences in relief by the most subtle gradations of tone.

His almost miraculous control is seen most clearly when he restricts himself to the range running from ‘rather light’ to ‘light’ and on to ‘very light indeed’. The Baptism, for example, is characteristic in that he treats the bark of the tree and the skin of Christ’s body as though they were both made of white marble.

As a result, subtle variations in tone are to be attributed not to differences in the make-up of the substance itself, but to the fact that differing facets of the surface are making different angles to the source of light and to the eye of the spectator.

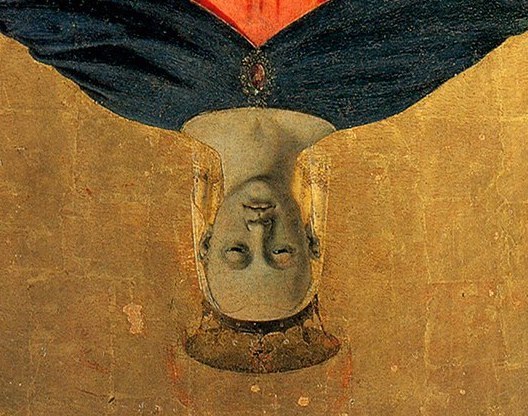

The first main consequence of his passion for geometry is his attempt to resolve all the complex and irregular bodies which are found in nature into the cubes, spheres, cylinders and cones of their divine prototypes or exemplars; and, perhaps most characteristically, to find the living compromise between sphere, cylinder and cone, which is to say the ‘egg’ or ‘ovoid’.

What you see here is the central panel of an altarpiece that Piero painted for his home town in 1445.

It represents the so-called ‘Virgin of Mercy’, that is, Mary as protecting her supplicants under her voluminous robe.

If you concentrate your attention above her cape (as in the detail), you will see that all wisps of hair have been tidied away; that the neck is a cylinder, placed on a section of a cone; and that the head is an egg under a section of an inverted cone.

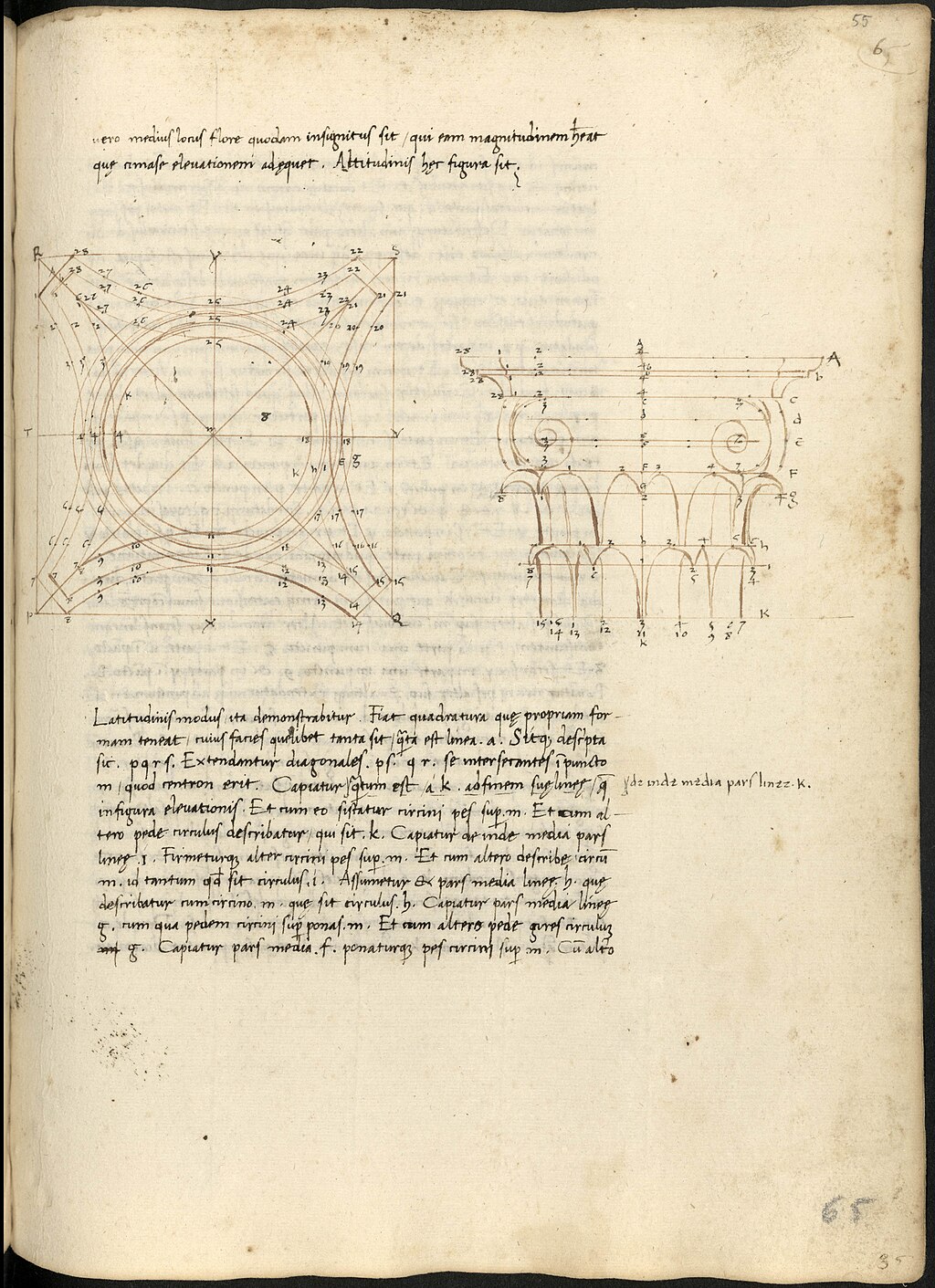

There was, however, a second, more technical aspect in Piero’s passion for geometry which is what led him to compose a detailed treatise on Linear Perspective, in order to teach other painters how to represent, on a flat, two-dimensional surface, any conceivable three-dimensional object, seen from any conceivable view-point.

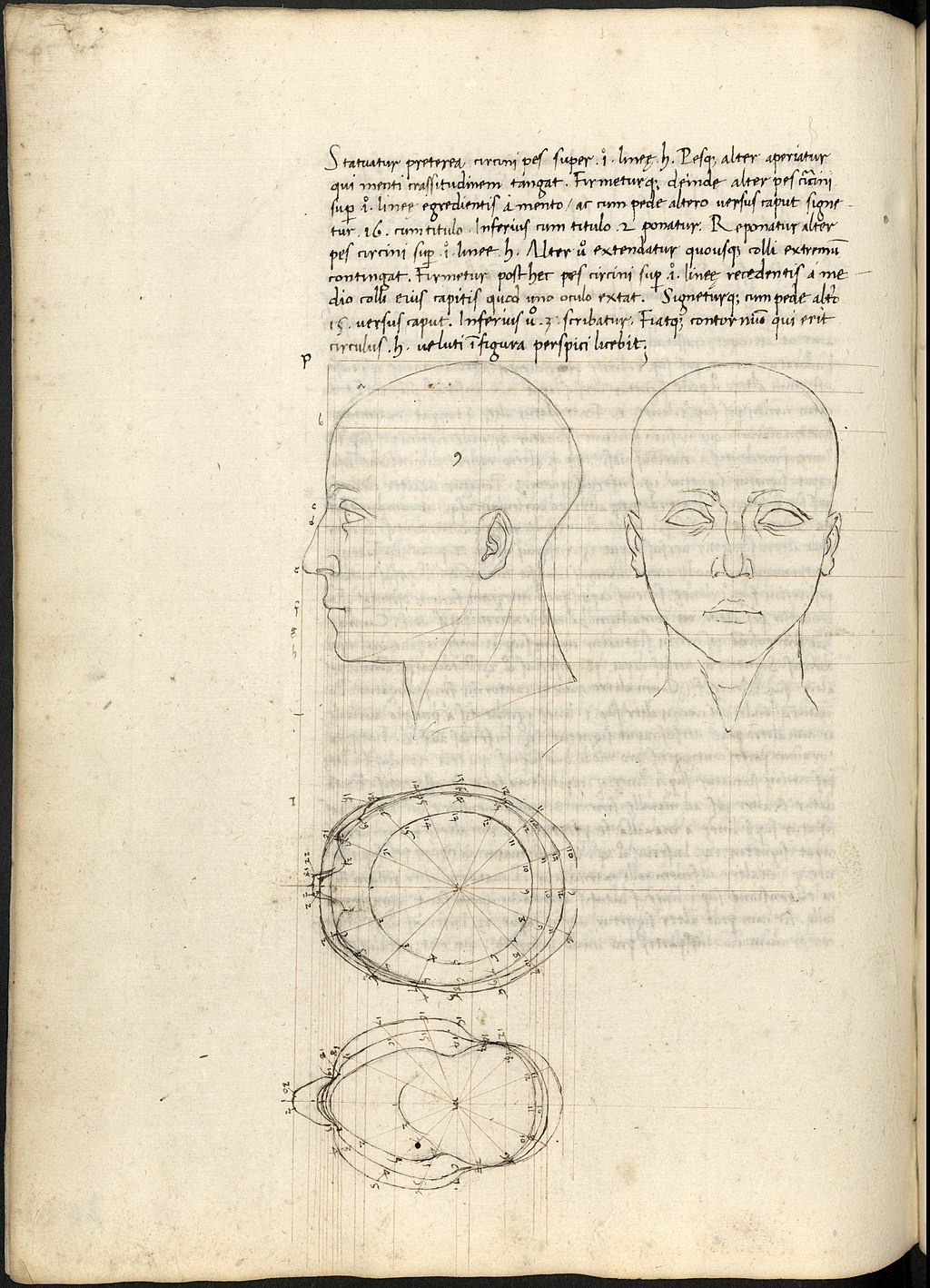

The images you see here are taken from that treatise and demonstrate how he uses the same meticulous approach whether he is drawing the wicker frame of an elaborate contemporary hat, the capital of a classical column, or the human head.

His meticulous measurements and cross-sections enable him to render a head, or a capital, or a hat from any angle whatsoever—the more challenging, the better.

Often, he seems to take a single ‘column-like’ head and neck and turn it through various angles to create different people within the one frame. (This detail offers a particularly striking example).

Given these obsessions, it is not surprising that Piero derived intense pleasure from the representation of classically inspired architecture—where the material is white marble; where the architect has already idealised the feet, trunk and head of the human body in the base, shaft and capital of a column; and where everything is regulated, as the Bible says ‘in weight, measure, and number’.

The painting which distils all that I have been saying into a single image is the famous Flagellation at Urbino (1455: it ought now to be retitled The Vision of St Jerome).

It is quite small, measuring only about two feet by nearly three.

Ignore the three enigmatic figures in the right foreground and focus on the classical interior.

Notice how the dramatically low viewpoint exposes the measured recession of the coffered ceiling and calls forth a geometrical tour de force in the rendering of the black and white tiles on the floor.

The ‘marble’ body of Christ (or of St Jerome dreaming he is Christ) is tied to the marble column but stands as stock-still as a statue.

In another artist, one would interpret the soldier’s raised arm as expressive of movement. Here it seems to grow out like a branch from the trunk of a tree, which is itself treated like a marble column, running from the soldier’s head perpendicularly down through his right leg.

So much by way of an introduction to Piero’s art.

Let us now return to the churches in Florence and Arezzo and examine the general layout of the frescos in the two cycles.

Look first at the setting of the earlier cycle by Agnolo Gaddi.

The two separate parts of the story of the True Cross are narrated in two separate entries in The Golden Legend; and they are each allowed a whole wall in Santa Croce.

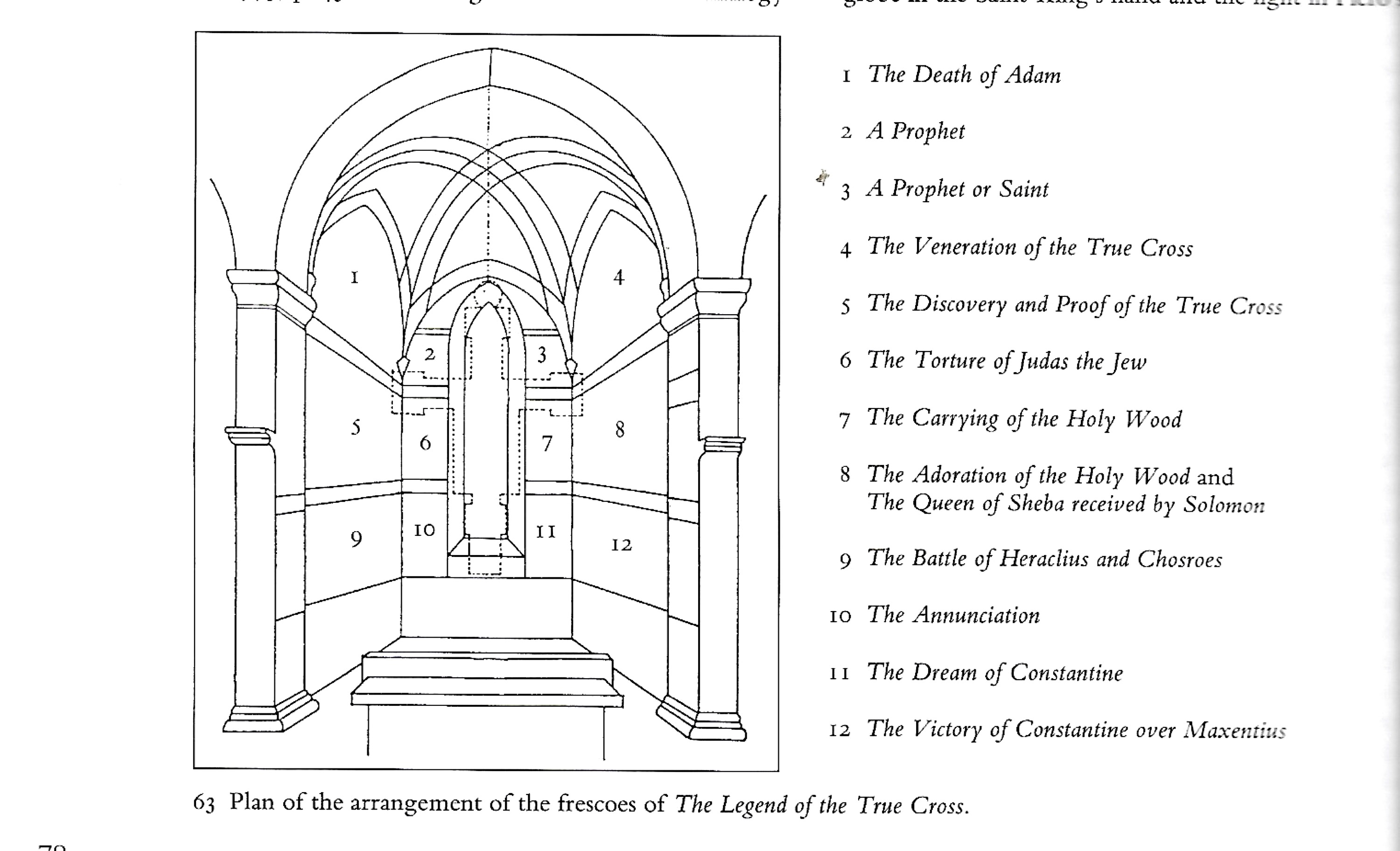

The choir of Piero’s church in Arezzo is lower; and it is also narrower, since there is only one window instead of three, as at Florence.

There is room for only three superimposed tiers on the side walls, but the area of each lunette and of each rectangle is about the same as at Florence, that is, about 25 feet across in each case.

At Arezzo, however, there are four narrower frescos on either side of the window, in addition to the six zones on the side walls. And since both Piero and Agnolo are quite willing to accommodate up to two episodes within a single pictorial frame, they each have an equivalent amount of space.

The first major difference in the two layouts is that Piero does not divide the two stories (the Finding of the Cross, and the Exaltation of the Cross) evenly between the left and the right-hand walls.

Although his first two ‘chapters’ are duly narrated in the right-hand lunette and in the rectangle immediately below it (as in Florence), the narrative sequence thereafter is very irregular.

Look now at the first of two diagrams of the layout in Arezzo.

Do not try to absorb the titles of the scenes (you can return for reference at your convenience later) but concentrate on the capital letters which indicate the narrative sequence. You will see soon realise that we must pass downwards from 4 to 8; then sideways to 7; then horizontally right across the bottom to 10, 11 and 12; while on the left-hand wall, we proceed horizontally from 6 to 5; then downwards to 9; before climbing to 1.

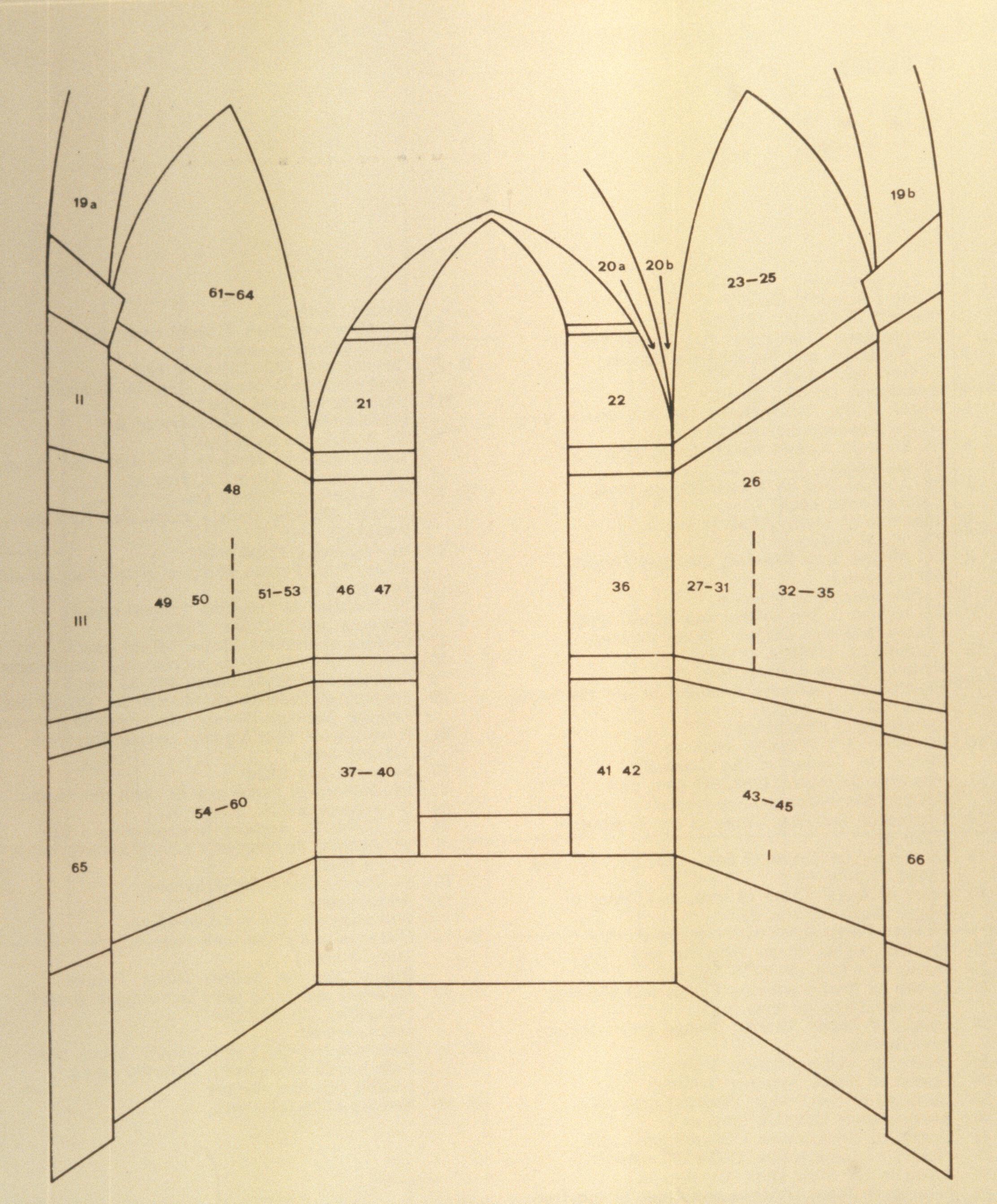

It is rather important to keep the arrangement of Piero’s frescos in mind when you are trying to make sense of the story at Arezzo, so let me reinforce the point by recapitulating the same information in this alternative diagram .

It shows very clearly the six large zones on the side walls (consisting of a lunette and two rectangles to both right and left) and also the four narrower zones (on either side of the window on the altar wall).

It uses numerals rather than letters to indicate the narrative order of the scenes and details. (Again, do not attempt to remember anything. Just allow the numbers to tell their own story…).

No doubt there were many different factors determining this very unusual departure from the obvious narrative sequence; and the patron and his advisers may well have had their say.

Yet the main reasons seem to have been artistic. We shall see that Piero is interested in scenes that lend themselves to ‘contemplation in stillness’, and he wanted to create a host of ‘rhymes’ or symmetries between frescos of the same height, whether they face each other across the choir, or lie to the left and right of the window.

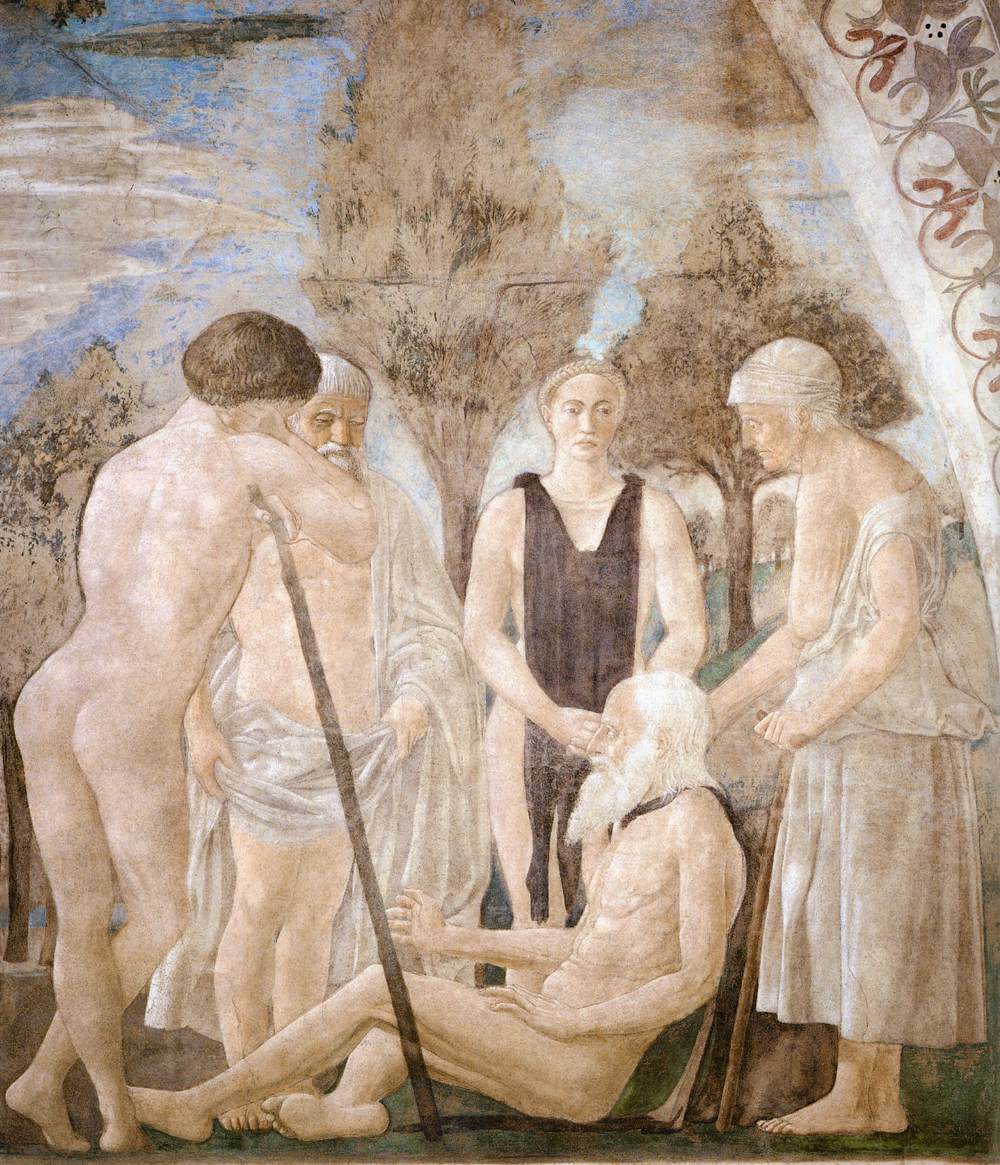

The first scene in the story, which is represented in the right lunette both in Florence and in Arezzo, begins thousands of years before Christ, in fact just three days before the death of our common ancestor, Adam.

In the Golden Legend it goes as follows:

One day when Adam was old and ailing, his son Seth went to the gate of the Garden of Paradise and asked for a few drops of the oil from the Tree of Mercy, that he might anoint his father’s body and thus repair his health. But the Archangel Michael appeared to him and said: “Nor by thy tears, nor by thy prayers, may you obtain the oil of the Tree of Mercy, for men cannot obtain this oil until five thousand five hundred years have passed”, which is to say, after the Passion of Christ.

Nevertheless, the Archangel Michael gave Seth a branch of the miraculous tree—the same that had led Adam into sin—and told him that on the day when this tree should “bear fruit”, his father would be made whole. And when Seth came back to his house he found his father already dead. He planted the tree over Adam’s grave, and the branch became a mighty tree which still flourished in the time of King Solomon.

The story is easier to follow in Florence, even when you are standing at ground level in the church itself. Agnolo uses the medieval convention of a ‘double scale’ in order to make Seth enormous on the hill in the distance and normal size in his second appearance in the group below; and he uses a high view-point to display Adam’s dead body in his shroud, with Seth planting the cutting in his heart at the centre of a half-circle of mourners, all of them in appropriate, ‘sacred’ robes.

Piero uses a single, very low viewpoint (and therefore. a very low horizon) and he spreads his actors in a frieze right across the foreground, very close to the frame. Seth and the angel are relegated to the background, at a size proportionate to their distance.

In the group on the right—as you can see in the detail—the artist concentrates on extreme old age and infirmity, showing an emaciated Adam, in profile, his stick on the ground, supported by Eve, stick in her hand, her breasts withered and hanging low.

A grandson rests on his hoe, while Seth, the son, already grey-haired, lifts his robe to set out on the journey, and a scantily dressed granddaughter looks solemnly down. All of them, in their attitudes and simple dress, remind us of the Lord’s curse recorded at the end of the third chapter of Genesis, that they must earn their bread by the sweat of their brow.

On the left and in the centre, in the scene around Adam’s dead body (you see him in profile at the very bottom of the picture), Piero follows an alternative version of the story and has a seed planted in Adam’s mouth, far less dramatically than in Gaddi.

He reserves the drama for the woman’s outflung arms—a ritual gesture of grief and mourning, which is both ‘cross-like’, and reminiscent of Mary Magdalene at the foot of the cross in many representations of the crucifixion.

At the extreme left of the fresco, two of the great-grandchildren look at each other ‘with a wild surmise’. They are in the presence of natural death for the first time in human history, but they are also ‘wondering’ at the planting of the seed, and the promise of being made whole.

The top of the lunette is, or was, dominated by the tree, the lignum, the ‘pezzo di legno’—either the parent tree in Eden, or the tree that was still flourishing in the time of King Solomon—spreading its boughs like a cross, and rhyming with the triumphant cross which we shall see in the other lunette, at the same height, on the opposite side, at the very end of our visit.

We now move down one level in both churches, and take up the story during the reign of King Solomon, at which time the tree planted by Seth was still flourishing. The Golden Legend version of the story goes like this:

Solomon was struck by the beauty of the tree and he cut it down in order to use it in the erection of the Temple. But no place could be found where it could be used: for sometimes it appeared to be too long, and other times too short; and when the builders tried to cut it to the length desired, they discovered that they had cut off too much. So they became impatient with the tree, and they threw it across a pond to serve as a bridge. But when the Queen of Sheba came to Jerusalem to try the wisdom of Solomon with hard questions, she had occasion to cross this pond; and, in spirit, she saw that the Saviour of the World would one day hang upon this tree. She therefore refused to put her foot upon it, but knelt instead to adore it.

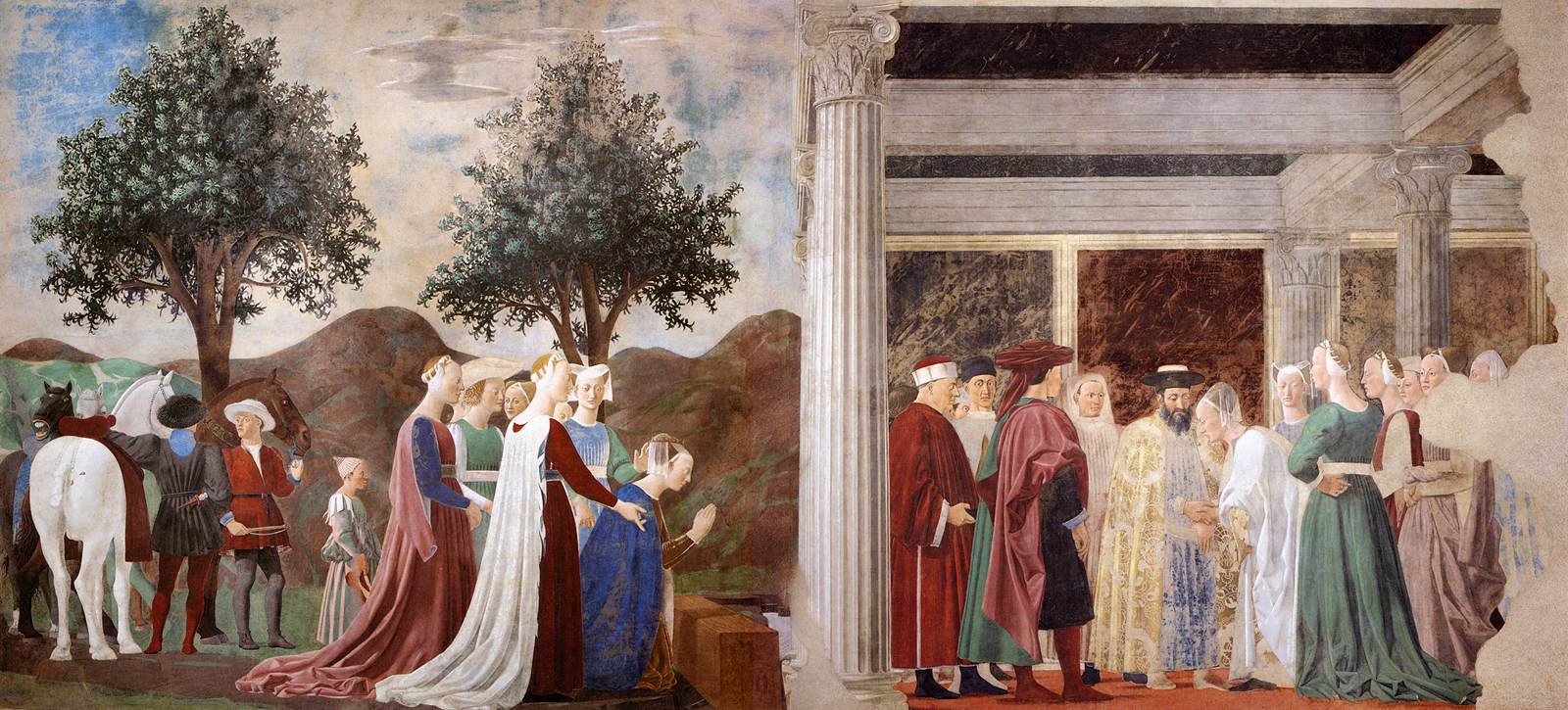

We can see her act of adoration on the left of both frescos; and (ignoring the area to the right in each case, which belongs to another separate episode, and is different in each of the two cycles), we can see that the composition of the Adoration is broadly similar in both churches.

The setting, in both cases, is a landscape of hills and trees. The crowned Queen, still youthful, kneels in front of a baulk of timber thrown across a stream. Her ladies-in-waiting stand in a group behind her, and some grooms hold horses in order to show that the party are on a journey.

This is exactly what one might expect to find in an Adoration of the Magi; and the quotation is clearly deliberate, because the ‘oriental queen’ who ‘came to Jerusalem’ was interpreted as a prefiguration of the Three Wise Men from the East.

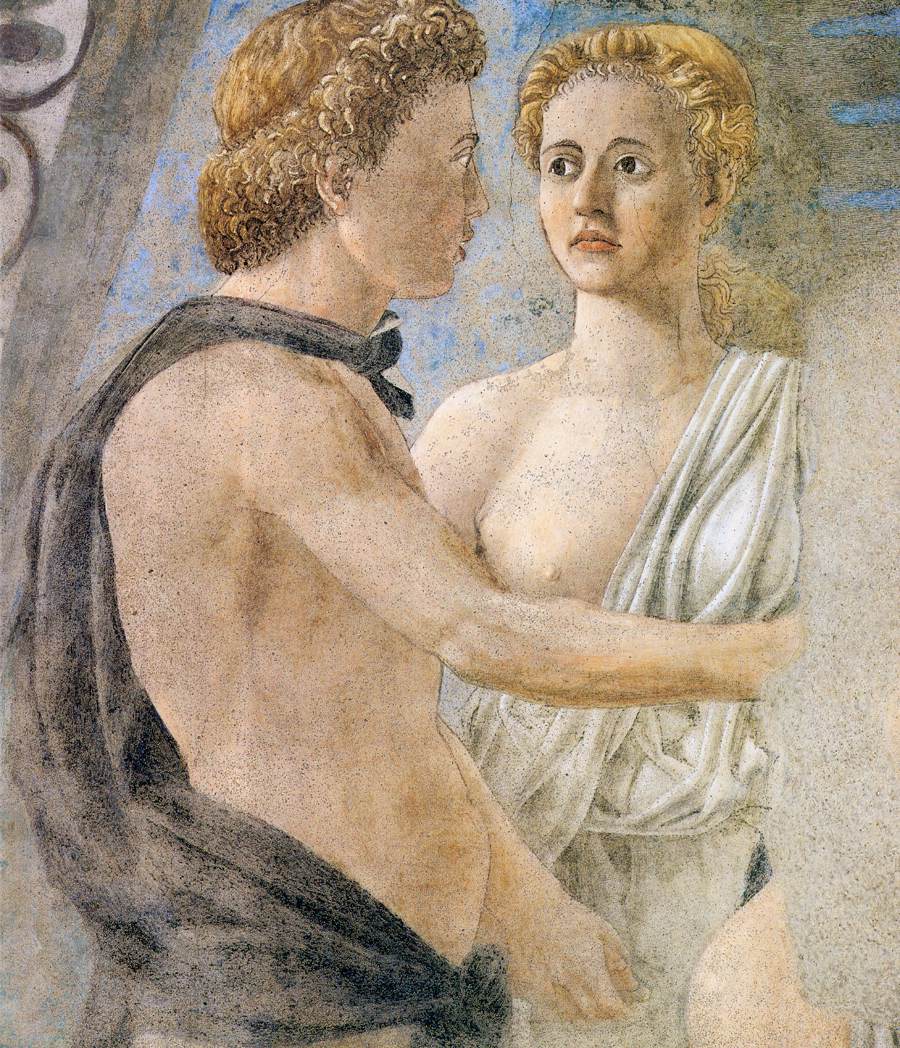

But then the differences begin—Piero separates the sexes, and he uses the two very large trees to reinforce the division between the groups.

The foreshortened rump of the white horse and the heads of the other three horses are very convincingly drawn, at least when considered as sculptures of horses.

Light falls from the left, casting a clear shadow across the doublet and hose, and modelling the legs of the men and the horses, which are equally column-like.

The two grooms—one with the dagger in his belt, the other holding a whip—exchange pregnant glances, like the ones you saw in the first scene; but they might also serve as fashion plates for contemporary costume, illustrating the difference between gathered pleats and a plain fall of the fabric, held by a plain belt—or, if you like, the differences between a round column and a fluted column.

Piero’s love of architecture is recalled even more strongly in the group of attendant women, where everything is equally motionless, and where the fluting or pleating of the dresses and the ‘capital-like’ headdresses contrast with the smooth columns and the ovoids of the long, bare necks, the shaven foreheads, the plucked eyebrows, and the close fitting veils of the majority.

The two ladies in profile (or near profile) are clearly ‘sisters’—which is a tactful way of pointing out that Piero often uses the same model for different characters in his stories, examining the same head from different angles, as we noted earlier. They are also ‘cousins’ to the Queen—the study of her profile being a lovely example of Piero’s powers of understatement, concentration and inwardness.

No less than a Meditation on old age and death (as in the lunette above), an Adoration is the perfect subject for Piero’s art.

This is borne out in the complementary scene to the right of the same fresco, where the meeting in Jerusalem between Sheba and Solomon enables Piero to portray a second act of veneration (this time the Queen is doing reverence to a sacred king who is one of the ancestors of Christ), even though this episode has nothing to do with the story of the True Cross, and does not occur in Gaddi’s cycle.

Before we examine the figures in this scene, please look closely at the virtuoso use of perspective. Notice that the vanishing point of the system is placed just a fraction to the left of the temple, so that you are able to make out the whole entablature on its side wall, and even the volutes of the rear columns.

The vanishing point is also placed very low, just above the baulk of timber; and this is why the ceiling beams are so prominent, and why the columns, pilasters and marble panels of the classical building serve both to separate the groups and bind together the members of each. It is also the reason why the figures seem much taller and more imposing than you might expect.

I will not dwell on the ladies, nor even on the isolated central figures and the slightly awkward act of reverence by the Queen to the King, which makes one think of Elizabeth stooping to greet and honour the Virgin Mary in a Visitation. (You will be able to enlarge these images when you return to them at your leisure.)

What you really must look at, though, are the heads of the four men in contemporary dress. Enjoy the expressive portrait of the burly, middle-aged donor, standing in profile, and the understated portrait-head of the austere young man in the black cap. And look at every fold in the fashionable hat— a mazzocchio—seen from a very awkward angle (just like the temple), as well as the profil perdu of the wearer of the hat, which is yet another typically quiet tour de force.

According to The Golden Legend, the Queen prophesied to Solomon that ‘upon this tree would one day be hanged the man who would put an end to the Kingdom of the Jews’; and the next scene in both cycles illustrates Solomon’s attempt to prevent the prophecy from coming true.

The story consists of just one sentence: ‘Solomon ordered that the tree be buried deep in the earth’.

In Florence, it forms the right-hand area of the previous fresco.

Agnolo shows Solomon, as a young man with the features of Jesus. He is crowned unobtrusively with what could be crown of thorns; and the artist is particularly attentive to headgear, or the lack of it, among the bystanders. (You will find a peaked cap with a long vizor, a helmet, an acorn, a turban, a fashionable hat, rough caps for the workers, flowing locks for a priest and one bald pate.) Fun, but no more than that.

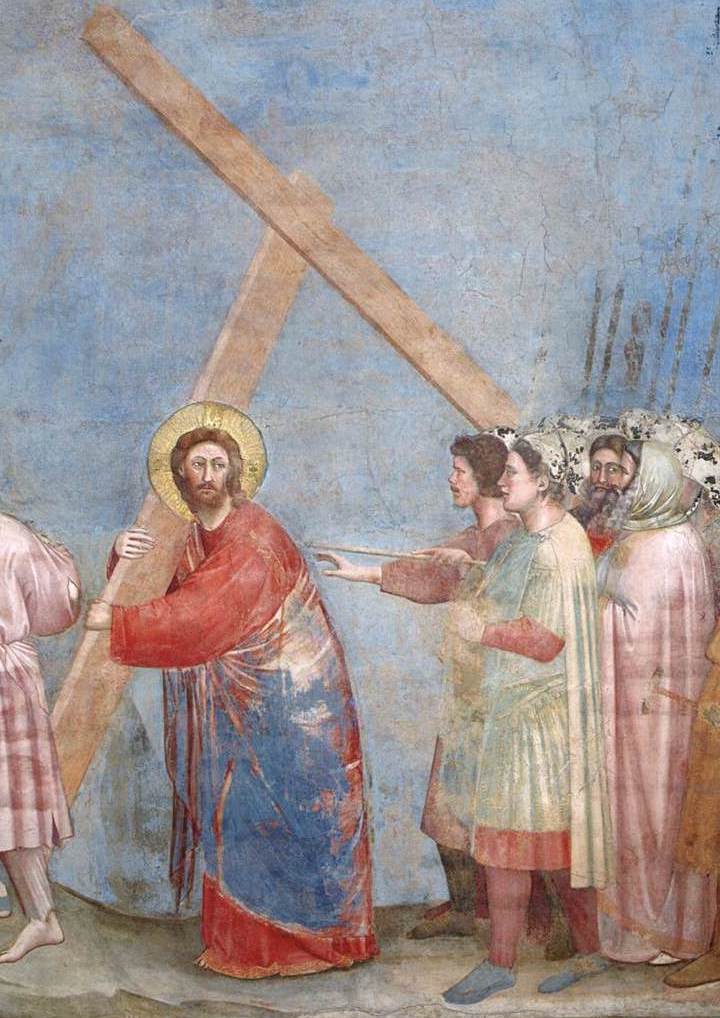

The pattern of the grain in the timber is almost as bizarrely stylised as the jagged clouds in the sky; but there is a good deal one might say about Piero’s powers of realistic observation in the foreground (look at the complex folds of the black and white doublet, or the scrotum of the first worker). However, I’ll content myself with two obvious comments on the symbolism.

You can see that the left-hand labourer supports the diagonal of the great beam as though he were Jesus carrying the cross to Calvary.

(I smuggle in a particularly powerful example of the prototype by taking you to the Arena Chapel in Padua and ‘flipping’ an image by Giotto.)

The detail also clearly shows that the artist painted the labourer’s hair and expression to make us think of the Man of Sorrows under the Crown of Thorns.

Piero now omits two important scenes which together form the subject of Gaddi’s third fresco.

In the Golden Legend we read that ‘at the spot where the tree was buried, the miraculous pool called Bethesda later welled up, so that it was not only the descent of the angel’ (as narrated in the Gospel of John, Chapter 5) ‘but also the power of the tree buried in the earth which caused the water to move and the sick to be healed’.

(Gaddi reinforces the last point by including the wards of a medieval hospital, with seven rather large patients, in the background.)

Then: ‘when the Passion of Christ drew nigh, the wood of the tree floated to the surface of the water’. (This is the moment illustrated on the left.) ‘And when the Jews saw it, they fashioned our Lord’s cross from the wood’.

Gaddi shows five contemporary carpenters at work in the right foreground with his usual clarity and attention to detail.

The Crucifixion itself is taken for granted in both fresco cycles.

(In the text of the Golden Legend, the relevant material belongs to the entries for Holy Week; while in the two churches, a crucifix is displayed prominently on or above the altar itself.)

But Piero does include his own rather oblique allusion to the coming of the Son of Man, by placing a scene of the Annunciation in the lower register to the left of the window.

(The figure of Gabriel is rather stiff and perfunctory, but the tall, upright, high-waisted figure of Mary—who was often represented as seated and inclining her head in humility—is pure Piero.)

You can see from the detail that this narrow fresco offers one of Piero’s loveliest evocations of classicising architecture.

Notice that the perspective system converges on a point which is both very low (as usual with him) and lying outside the composition to the right; while the light in the painting seems to come from the right (as though from the real window alongside) to model the marble of the column which seems to form the upright of a Cross, with the entablature as its beam.

The Annunciation lies to the left of the window; and we must now make two horizontal moves to the other side to tackle the story of the Emperor Constantine, three hundred years later.

The first scene, which you see here (again exploiting our format to perfection) is indeed paired with the Annunciation on the other side of the altar.

It too has an angelic messenger and another clear allusion to the cross.

The story of Constantine is narrated in the Golden Legend but is only loosely connected with the wood of the True Cross and its rediscovery.

If we ask why Piero included it, and Gaddi left it out, the answer could be in two parts.

The first is a question of temperament: Gaddi is the story-teller, Piero the contemplative.

The second would reflect the dramatic changes in the balance of power in the Near East in the first half of the fifteenth century. The Turks began their main advance to the West after 1390, and Constantinople would fall in the year 1453, while Piero was at work on these frescos. Successive popes in the fifties and sixties were to proclaim ‘crusades’—that is, Holy Wars ‘in the Sign of the Cross’—with the aim of driving the infidel from Jerusalem and from the Holy Land. Hence, Piero and his patrons are here indulging in a mixture of wishful thinking and propaganda.

Back to the story (I remind you that three hundred years have elapsed since the previous episode):

At that time an innumerable horde of barbarians under Maxentius was massing on the bank of the Danube, making ready to cross the river, in order to subjugate the entire West. At these tidings, the Emperor Constantine marched forth with his army and camped on the other bank of the Danube. Constantine was filled with fear at the thought of the battle which he had to undertake. But in the night an angel awoke him and told him to lift up his head. And Constantine saw in the heavens the image of a cross described in shining light; and above the image was written in letters of gold the legend: “In this sign you shall conquer”.

For many people, Piero’s narrow fresco is the most memorable scene in the whole cycle, and it comes as rather a surprise to discover that he may have found inspiration in Gaddi’s cycle—Gaddi having adapted the dream in order to make it fit a rather similar episode, concerning another Emperor (Heraclius), much later in the story. If you look at the detail, you will see that the shape of the pavilion, the opening, the pole, the sleeping emperor, the three soldiers, and the angel in the sky are all there in Florence in 1390.

But of course, closer comparison only heightens one’s awareness of the transformations that Piero has brought about. Everything and everyone in Piero’s fresco is stock still, whether standing, seated, or lying down. This immobility provides the maximum contrast for the irruption of the angel, who is bathed in supernatural light and so boldly foreshortened as to be almost unrecognisable. It is the angel who holds out the diminutive cross and who himself forms the ‘sign of the Cross in shining light’.

En passant, the comparison helps us do justice to Gaddi and the artistic conventions of the 1390s.

Agnolo makes a significant allusion by positioning the drowsing soldiers exactly as they might appear in a typical scene of the Resurrection of Christ from the sepulchre. His emperor is plausibly disturbed in sleep, resting his head on his arm (which is what the aide de camp is doing in Piero’s version). And he gives form to the content of Heraclius’s vision by showing the emperor a second time, apparently bursting out of the side of the pavilion, as he charges into battle on the following day, crouched over his white stallion with its rippling mane.

Back to Constantine—and to the art of Piero della Francesca.

Neither the monumental stillness and solemnity, nor the downward plunge of the angel, is as amazing as the suggestion of darkness, unevenly illuminated by celestial light.

Giorgio Vasari was quite ecstatic about this effect even a hundred years later; and no Italian painter had achieved anything remotely comparable before—let alone in the medium of fresco!

So, look at the play of light over the stretched red canvas of a cone or in the folds of the brailed-up entry; and focus on the light in the detail as it spreads across the dark metal of the soldier’s peaked helmet and shoulder, or plays irregularly over the woollen cloth worn by the splendidly calm and youthful aide-de-camp.

(A brief snatch of autobiography. In the summer of 1954, during my first visit to Italy, I was dragged out of bed by a fellow student at the University for Foreigners in Perugia and dumped into a very early coach to Arezzo. Walter came from the Saar. He had been well educated and knew what to expect. I wasn’t and I didn’t. I still remember the impact of Constantine’s Dream on my totally innocent and uncomprehending eye. When I got back to England, I purchase my first-ever art book: Kenneth Clark’s Piero della Francesca. Ich danke Dir, Walter.)

We come next to the consequences of the dream, which are depicted in the lowest scene of the right wall, immediately alongside.

This fresco is almost 25 feet across, and as you can see, damp and chemicals have played havoc with the surface, especially on the right. Hence it may be easier to follow the story if you look at the copy in water-colour, made 180 years ago, when the fresco was still more or less intact.

The story goes as follows:

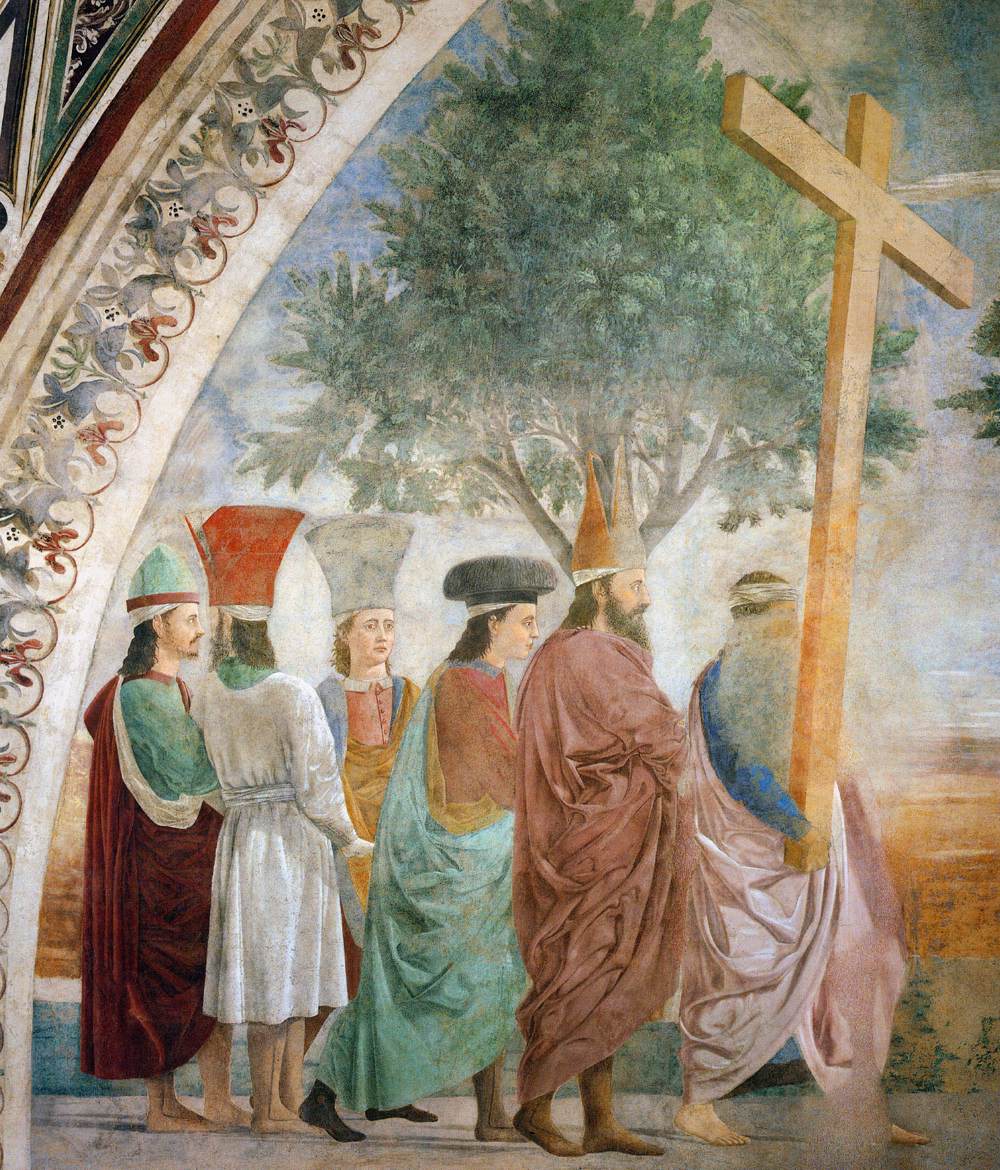

‘Constantine took heart at the heavenly vision. He had a wooden cross made and he commanded that it be carried in the van of the army.’ (Piero makes him carry the cross himself.)

‘He then implored God that his hand, armed with the sign of salvation, should not be stained by the blood of Romans who had been conscripted into Maxentius’s army.

He fell on the enemy, drove them across the Danube, and put them to flight’.

Piero has in effect seized the opportunity to paint the first and last scenes of a three-part Battaglia in a single composition, that is, he shows one army advancing, and the other routed and put to flight.

(I hope you will take the opportunity to explore (at your leisure) the many interesting parallels with Paolo Uccello’s contemporary Battle of San Romano, the last scene of which is now in the Uffizi, while the first is in our National Gallery.)

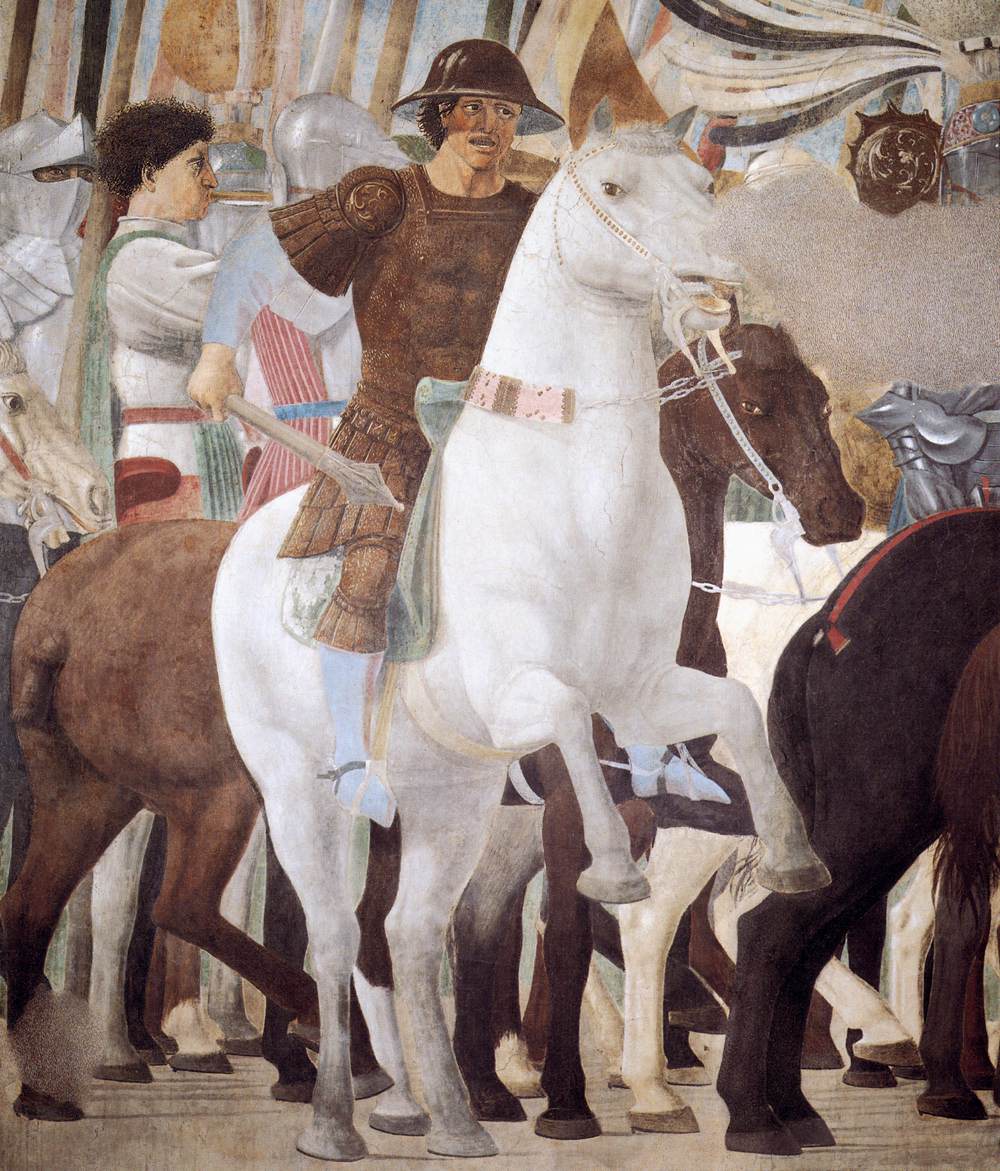

Like Uccello, Piero is having a lot of fun with fluttering heraldic banners (notably an imperial eagle and a dragon), patterns of raised lances, statuesque horses, and men in complex suits of armour.

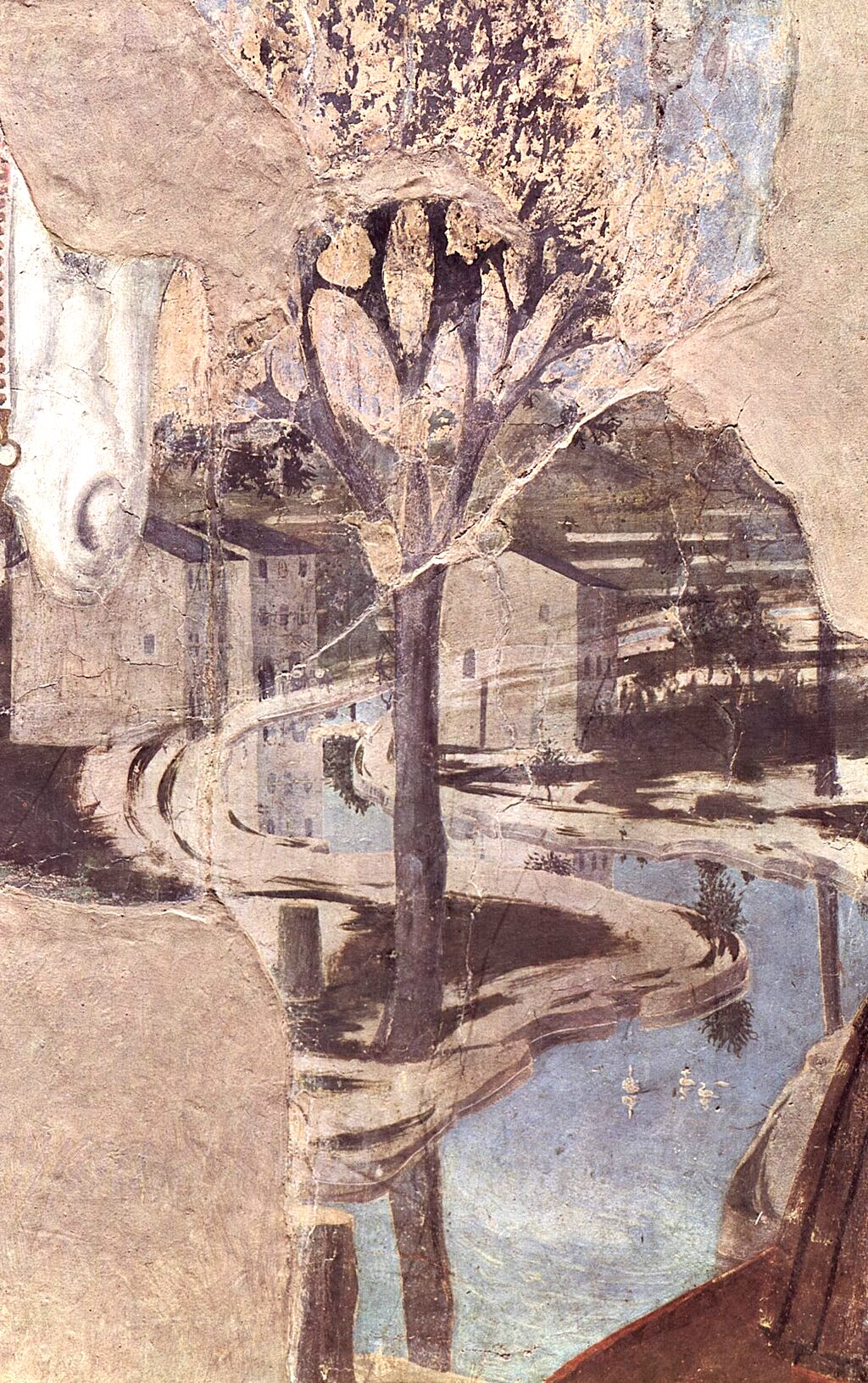

But the mood is tranquil. No blood is to be shed, and so the most significant detail may be the mighty River Danube (looking very much like the source of the River Tiber near Borgo San Sepolcro), calmly reflecting the sky, buildings and trees, and patrolled by two white swans and a grebe.

Constantine rides forward, serenely confident of a bloodless victory in the Sign of the Cross.

His features and his hat are borrowed from a famous portrait-medal by Pisanello, showing the man who had been emperor of Constantinople in the 1440s—the last but one eastern emperor (as it proved), since his successor was killed when the Turks captured Constantinople, more or less exactly at the time when the fresco was being painted.

After his victory, Constantine is said to have found out about Christianity, and to have been converted and baptised. The next two scenes in the story concern his mother, St Helena, and how she came to rediscover the True Cross, in whose sign her son had been victorious.

The narrow fresco shows the results of St Helena’s skills as a detective—both in finding people, and then in persuading them to talk.

The hatless man is called Judas, and he is the only person in the Jewish community at Jerusalem who knows where the timber of the true cross was buried after the crucifixion.

When Helena tracked him down, he refused to part with his secret, because he believed that the rediscovery ‘would bring to an end the Kingdom of the Jews’; so, Helena had him put into a dry well-shaft, without food, to consider his position. A week has gone by, and Judas has just indicated that he will reveal all. In consequence, he is being hoisted out of the well.

There is quite a lot one ought to say even about such a simple scene; but from the point of view of the story, one need only remember Judas’s brown coat; and from the point of view of the whole design, one should note the diagonals of the huge wooden tripod, which help this scene to balance and to ‘rhyme’ with its partner on the opposite wall, which was dominated by the diagonal of the beam being lowered into a narrow hole.

We must look for similar rhymes or echoes as we move sideways to the wide fresco on the north wall, which faces the scenes with the Queen of Sheba on the south.

Like its partner, it is about 25 feet wide, and it is divided by architecture into two scenes.

On the left, in the part nearest the nave, a queen is again seen in profile, standing, with head bowed; and in the part nearest the altar wall, the same queen kneels in profile to adore the wood of the cross. It is directly opposite the scene we examined earlier, and the features of the two queens are virtually identical.

(Gaddi, as we shall see, had combined the same two episodes in one fresco at the bottom of his right-hand wall.)

Let us make ourselves perfectly familiar with the two distinct moments in the story.

According to the Golden Legend, Judas led them to a place ‘near a Temple of Venus, which had been raised by the Emperor Hadrian, so that whoever should come to adore Christ would appear to adore Venus at the same time. And for this reason, Christians had ceased to visit the place. But Helena had the temple torn down, whereupon Judas himself started to dig into the earth, and twenty feet beneath the surface he found three crosses, which he at once caused to be carried to the Queen’.

Gaddi places the discovery on the right of his composition, and he shows us just the first of the crosses, placing the tightly packed, overlapping figures of the onlookers to either side of the workmen in the pit.

Piero spaces his figures most beautifully, with the heads of the main figures all at the same height; except, of course—and the exceptions are all motivated in different ways—the labourer who is stooping, the dwarf, and the labourer in the pit (whom the low viewing point cuts off at the waist).

The main figures are Queen Helena, her calm-faced officer; a labourer heaving out the second cross; Judas in his brown coat (alas, now without his head), directing operations and supporting the first cross; and two other labourers, in repose, on either side of him—one with his mattock over his shoulder, the other leaning on his shovel, with an expression that was much admired by Vasari.

We move on to the miracle depicted in the other half of the fresco, both in Arezzo and Florence. These images show you the two relevant details:

The story goes like this:

It remained only to distinguish the cross to which Christ had been nailed from those of the thieves. All three were set up in an open space; and Judas, seeing the corpse of a young man being borne to the two, halted the cortège, and laid first one, then another of the crosses over the body. But the corpse did not move.

Then Judas laid the third cross upon it; and instantly the dead man came to life.

One must never neglect the architecture in Piero.

So, look at the modern street scene shown in steep recession on the extreme right, and notice the half-concealed marble cupola and lantern at the very top (both inspired by Brunelleschi’s cupola and lantern for the cathedral in Florence).

Then focus on the geometrical façade of the temple in classical style (or rather, in the style of Leon Battista Alberti) which once again is a technical tour-de-force, because it is seen from very low down, and is not quite fully frontal.

Next, let your eye come down to the three male bystanders on the right—in contemporary dress—and follow the direction of their gaze to the miracle, with its incredibly difficult exercise in the foreshortening of the cross, which seems to loom out towards us over the body of the resuscitated youth.

Finally, enjoy the truly ‘Pierian’ moment of adoration, in which the heads of Helena and her companions, echo those of Sheba and her ladies on the opposite wall.

That is the end of the story of the Invention—that is ‘Finding’—of the True Cross.

The final scenes in the two cycles are taken from the legend relating to the Feast of the Exaltation of the Cross, which fell on September 14.

In Florence, Gaddi had devoted the whole of his second wall to episodes from these further adventures of the True Cross, beginning at the top, in the lunette, in which Helena (with a halo surrounding her elegant, eastern hat) returns the cross to its rightful place in the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem, while the inhabitants kneel in adoration.

We need not dwell on this, nor on the second scene, which takes place three hundred years later, in 615, when the King of the Persians, Chosroës, who has conquered the Middle East, comes to Jerusalem and to the Holy Sepulchre, and steals some pieces of the cross, before being driven away in terror:

You may be able to make out four horsemen galloping out of the city gate, one of whom is carrying a large chunk of wood on his shoulder, while the old infantry man with a scimitar in the foreground has another large piece of the cross tucked under his arm. Neither of these episodes is to be found in Piero.

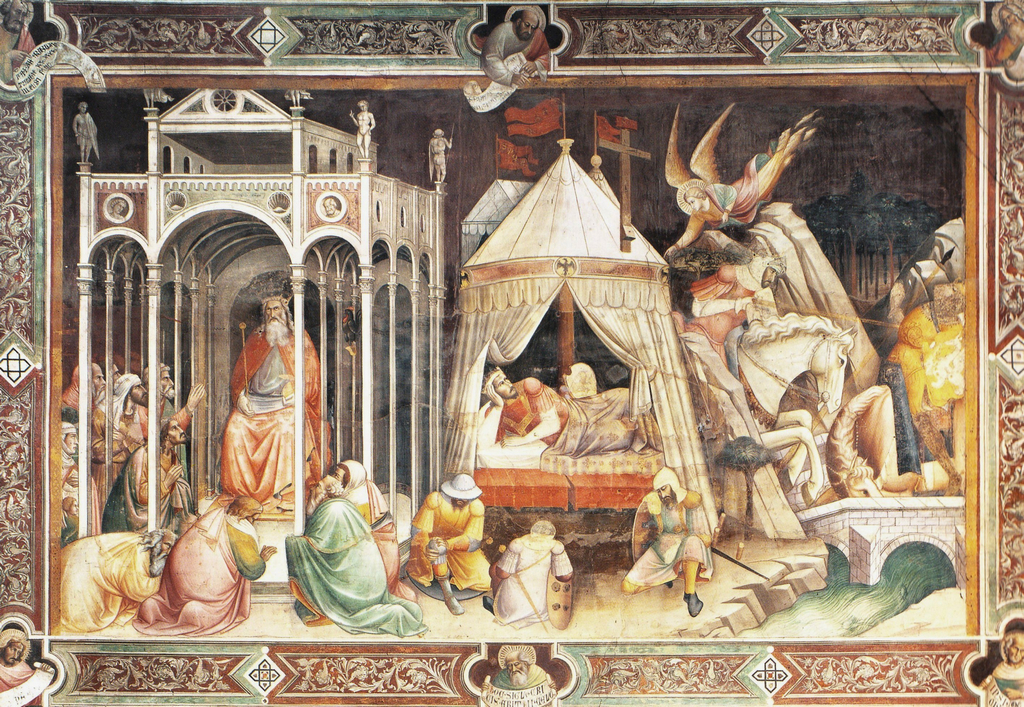

Gaddi’s third fresco, however, deals with an episode that we also find at Arezzo, where it appears as the lower of the long frescos on the left wall. (The two details here show the crucial moment in the story, as interpreted by each artist.)

The story concerns the mad delusion that came to afflict King Chosroës (as it seems to afflict so many absolute rulers): he wanted his subjects to adore him as God.

Quoting from the Golden Legend again:

He built a tower of gold and silver studded with shining gems, and placed upon it the images of the sun and the moon and the stars. Then, handing over his kingdom to his son, the profane king seated himself in this temple, demanding that all salute him as God.

Seating himself upon the throne as the Father, he set the wood of the cross at his right side, in the Son’s stead and a cock at his left as the Holy Ghost, and commanded that he be called God the Father.

Gaddi places the King impressively on the throne inside the tower (which is topped by statues of pagan deities).

Piero shows the throne empty; but you can clearly see the cockerel and the wood of the cross on his right.

This page gives you a chance to see the whole of Gaddi’s third fresco; and you will recognise in its centre the scene which helped to inspire Piero for his Dream of Constantine. It represents the Emperor Heraclius, who is being urged by an angel in his dream to attack Chosroës and to avenge this blasphemy.

In the scene on the right of Gaddi’s fresco, you should be able to make out a tiny bridge over the River Danube, where Heraclius, in white armour on a huge white horse, is unseating his opponent, who is the son of King Chosroës (the two armies having agreed, in the best traditions of epic poetry, that the dispute should be settled by single combat between the leaders).

Piero, by contrast, refused to be tied closely to the letter of the Golden Legend. He had a large space to fill, which he wanted in some way to ‘rhyme’ with the bloodless victory of Constantine at the same height on the opposite wall; and he chose to present another full-scale Battaglia in close-up, like a battle scene on a Roman sarcophagus.

Nevertheless, he was clearly familiar with the story; and the text of the Golden Legend enables us to identify the man on the white charger as the son of Chosroës, and the man on the dark horse in dark armour as the emperor, Heraclius.

Take a moment to enjoy the heraldry of the banners: a swarthy maiden toppling backwards before the imperial eagle, a Tuscan lion, and the Holy Cross itself.

Focus on the detail of the soldier behind Heraclius, whose powerful arm anticipates the proportions of Michelangelo’s ignudi in the Sistine Chapel: it also happens to be another good example of Piero’s power to suggest the role of light as a modeller of forms.

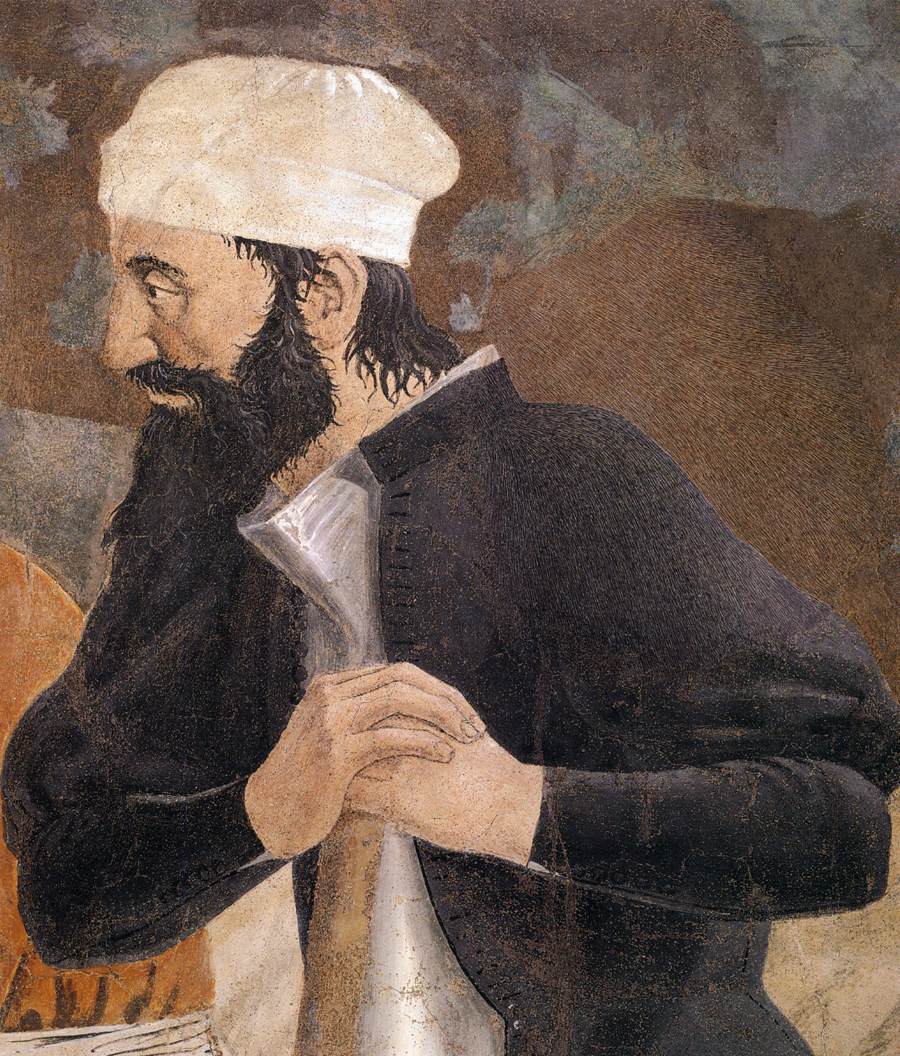

There is a great deal of Piero’s art, too, in the detail of the trumpeter, puffing out his cheeks under the chef’s hat, alongside the head of a knight who is totally enclosed in his helmet.

Piero places the next moment in the story on the right of his fresco, in front of the throne of Chosroës’s temple, where the mad old king (with the features of God the Father in an earlier episode) is about to have his head cut off, after having refused to be baptised.

As always, the varied helmets of the soldiers and the inscrutable faces of the witnesses are not to be ignored. (The three civilians are clearly portraits.)

Gaddi, by contrast, chooses to paint the decapitation of Chosroës in his final fresco, to which we now turn, where you will see the executioner sheathing his sword, on the left, having done the deed.

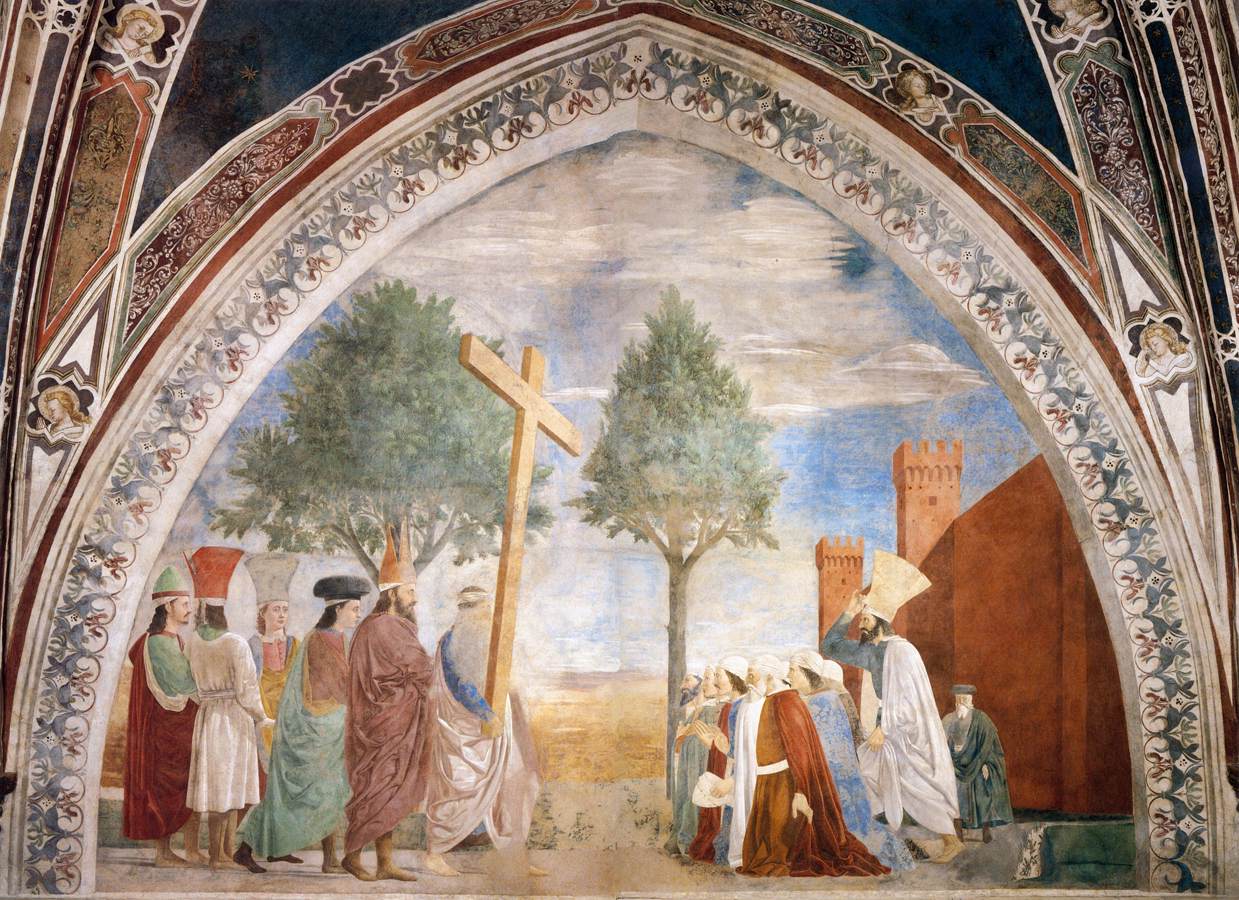

The upper section and the whole of the right half of Gaddi’s fresco (above and to the right of the diagonal line of rocks), illustrates the end of the legend of the Exaltation of the Cross—the same scene that Piero will place in the lunette at the top of his left-hand wall.

Once again, you will probably find it easier to follow the story in Gaddi’s version.

Heraclius carried the Holy Cross back to Jerusalem. He descended the Mount of Olives, riding on his royal charger and arrayed in imperial splendour and was about to re-enter by the gate through which Christ had gone to his Passion, when, suddenly, the stones of the gate fell down and formed an unbroken wall against him. Then, to the astonishment of all, an Angel of the Lord appeared over the gate, holding a cross in his hands, and said: “When the King of Heaven, coming to his Passion, entered in by this gate, he came not in royal state but riding on a lowly ass. And thus he left an example of humility to his worshippers”.

Then the King burst into tears, took off his shoes, and stripped himself to his shirt, took up the Cross of the Lord and humbly carried it to the gate. Instantly, the hardness of the stones felt the power of God go through them, and the gate lifted itself aloft, and left free passage to those who sought to enter.

Gaddi, as always, is the faithful story-teller or illustrator. If the tale requires two scenes to make its point, he gives you two scenes. Hence, he shows the same gate twice: in the centre, beneath the angel, where it is still bricked up; and on the right, where you can see the miraculous aperture.

Piero’s instinct, by contrast, leads him to concentrate exclusively on the climax of the story; and he ‘exalts’ the cross (carried as it would be in a contemporary religious procession) at the very top of the wall, letting it rise up into the lunette, to answer the towering tree in the lunette on the opposite wall, the tree which would provide the wood for the cross.

We can see tall Greek hats and a bishop’s mitre among the emperor’s followers standing on the left, and we can see the citizens of Jerusalem kneeling on the right; but, by an irony of fate, damp has attacked and almost obliterated the figure of the Emperor himself in the centre, and so we have to take his shirt and his air of penitence and humility on trust.

There is a Cross and a Tree, but no King.

But perhaps this very accident confirms the relevance of the opening words of Pinocchio with which I began. And by now you will be able to understand the words of my own introductory paragraph, where I said ‘the story I shall be telling in this lecture is about a piece of wood; and we shall follow its adventures from parent tree to a cutting, from a cutting to another tree, from tree to a piece of timber that was twice carried by a king and itself carried one of those kings, was twice buried, was stolen by a heathen king, and rediscovered by a saint who was the mother of the first Christian emperor. It is a fairy-story, a story of “once upon a time”. It does involve a king or, rather, several kings; but the subject is nevertheless a “piece of wood”’.

‘Once upon a time there was…“a King”…. No, boys and girls, that’s where you’re wrong, once upon a time there was a piece of wood’: ‘C’era una volta un pezzo di legno.

REUBEN: IT WOULD BE NICE TO HAVE THIS FINAL IMAGE IN THE CENTRE, EVEN THOUGH IT IS AN ALPHA-SHAPE (not sure what Pat is suggesting here, and did he mean the text “FINIS” to be at the bottom of the page?)