Luca della Robbia: Cantoria

In the previous five lectures, I talked about the wealth and power of the Florentine city-state, the role of the guilds, and the citizens’ immense pride in the buildings that made Florence so beautiful, ‘Fiorenza bella’. You have seen evidence of their Christian belief and piety in paintings and sculptures, illustrating the Old Testament, the New Testament, and the Life of St Francis; and I have stressed that republican pride and Christian faith were in no way incompatible, and that the two were joined together above all in the construction of the cathedral, which was begun back in Dante’s time in the 1290s, and finally came to dominate the city skyscape, as you see in the view of the city (fig. 1a) painted nearly 200 years later.

The cathedral is just as much a symbol of the commune as it is an expression of devotion to God, and it is the cathedral which forms the link between my three ‘figments’ this evening: You will learn about at its completion in the year 1436; we will have a leisurely look at the relief sculptures (fig. 1 b) on one of the two marble singing-galleries which were commissioned to stand under the cupola; and, finally, I will discuss the music of the motet that was specially commissioned for the dedication of the cathedral in 1436.

**TOM: PLEASE SWITCH THESE LEFT AND RIGHT

The link between the building and the music lies partly in the solemn occasion, and partly in the subject chosen for the relief sculptures; but mostly it lies in an attitude to proportion and harmony which linked the arts of architecture and music to each other, and both of them in turn to the greater art or craft of God, the creator of the universe and of ‘all things visible and invisible’, because the Bible affirmed that he had made all things ‘in measure, number and weight’, in mensura et numero et pondere. This much quoted verse was taken to mean that God had used simple ratios and the properties of certain numbers to ensure that the cosmos was a perfectly ‘proportioned’ and therefore ‘harmonious’ whole.

Proportion and ratio are of such importance to the whole lecture that I will begin by outlining a few basic facts and their symbolic meaning, before we examine the details. God had ordained that the ratios of 2:1, 3:2, and 4:3 should be not only visually pleasing, but satisfying to the ear, because they determine the so-called ‘perfect’ intervals of octave, fifth and fourth, which create perfect consonances when sounded simultaneously with the fundamental.

He created the world in six days because six was the first perfect number—‘perfect’ in the technical sense that it is the sum of its proper divisors: 1 + 2 + 3 = 6. When God gave instructions to Solomon regarding the building of the Temple of Jerusalem, he insisted that its three main dimensions should be in the ratio of 6, 3 and 2—60 cubits long, 30 cubits high, and 20 cubits wide (the Sistine Chapel follows these dimensions). He also declared that it should be divided into a ‘House of Prayer’ and a ‘Holy of Holies’, forbears of the nave and choir in Christian churches, in the proportion of 4:2 (40 cubits and 20 cubits).

In other commands with respect to the building and consecration of the Temple (details that were to be imitated exactly in the re-building of the papal chapel in Rome), God gave great prominence to the numbers 4 and 7 (our week of 7 days being a reflection, or imitation, of the six days of creation followed by the day of rest): 4 and 7, rather than 2, 3 and 6, are the crucial factors of the next perfect number, 28, which is the only perfect number between 10 and a 100. With this minimum of background ‘in mensura et in numero’, we may turn now to the building of the Florentine cathedral, Santa Maria del Fiore.

It was begun back in the 1290s, and it rose over the existing cathedral, which had been dedicated to a local saint called Reparata: the apse of that earlier church forms the crypt of the present cathedral.

Building work proceeded fitfully between the death (in 1302) of the original architect, Arnolfo di Cambio and the 1350s; but it gathered momentum again after the Black Death, when many modifications were discussed, rejected and revised, until in 1367 a definitive plan was drawn up, which every successive superintendent of works had to swear to preserve. That plan was apparently very similar to the church represented in a famous fresco by Andrea da Firenze in the Chapter House of Santa Maria Novella (below left), which I have flipped horizontally to make the cupola appear at the same end as in the photograph of the cathedral:

Notice the similarities between the fresco and the cathedral. In both cases, there are four bays in the nave (originally with Gothic windows), and three domed chapels at the east end, instead of a normal transept and apse. In both cases, the chapels are flanking an octagonal crossing, which is topped by an octagonal cupola and a lantern: the ribs of the cupola are plainly visible, with a section or profile that is clearly not hemispherical, but more acute. Andrea must have been painting from a model of how the cathedral was, or was going to be, in the modified fourteenth century plan of 1367—a plan for a great civic cathedral for the biggest commune in Tuscany, consciously intended to outdo the cathedrals of Siena and Pisa.

Turning now to the ground plan, you can see the octagon in dotted lines, and the three complex ‘bumps’ surrounding the octagon, each divided into five chapels, and separated by two sacristies to the North East and the South East. Fig. ¿fig:6? shows what the East end looks like from outside, in its three-toned marble facing, and with its bulging bumps to the East and the South:

The final plan is an ideal compromise between a centralised church, a so-called Greek cross, with four equal arms (you can easily imagine a fourth set of five chapels instead of the nave), and the Latin cross of a normal basilica, which has a long nave and shorter transepts. It was ideal for a civic cathedral, because it could hold about a quarter of the entire population in the nave alone; and, perhaps more importantly, a huge congregation could assemble all around the high altar, which was, and is, placed at the centre of the crossing.

The approach to the crossing from the West end is very exciting, because the arches of the nave are sprung very low, and the arches supporting the roof begin immediately above the low gallery, making the nave and aisles seem broad and low: hence there is a great sense of climax as you come to the unbroken space of the crossing under the cupola.

This is a good point to spell out a few of the significant dimensions and proportions.

The central bays are squares and the nave is four bays long, 4:1. Each aisle is half the width of the central bays, so that the proportion of the length of the nave to the width is 4:2, or 2:1. The document of 1367 laid down that the height of the cupola should be twice that of the nave: once again, we have the ratio between the wave-length of a fundamental and that of the same note an octave higher. More importantly, the document fixed the height of the nave as 72 cubits (taking the Florentine braccio or ‘arm’ as the equivalent of the Biblical cubit). If you multiply 72 by 2 to obtain the height of the cupola, the answer is 144, which according to The Book of Revelation is the length of the wall girdling the celestial city.

More numerical relationships have been claimed in an effort to discover a consistent use of the factors of 6, and thus a deliberate imitation of the Temple of Solomon; but these have now been debunked, as have some even more improbable claims for architectural relationships involving the factors of the next ‘perfect’ number, 28. So let us leave the subject of number symbolism for the moment, and come on to the construction of the crowning glory of the cathedral, the cupola itself:

We move forward, then, from the definitive plan of 1367, past the decision in 1410 to build a ‘drum’ below the cupola itself to admit more light, and come to the agonised committee meetings of the period 1417–20, when it was finally decided to entrust the task of building the cupola to Filippo Brunelleschi—whose profile you see, allegedly, in the head to the right of Masaccio and Leo Battista Alberti in the detail from the Brancacci Chapel (fig. 13):

It was Brunelleschi, by now 43 years old, who devised the master plan and oversaw every detail of the building of the cupola. Work began in earnest in the year 1420, and finished in 1436—though the marvellous lantern was not completed until after 1446. The story of the construction is told in vivid detail by Giorgio Vasari in his Lives of the Artists (which is available in several translations), and in fact his account occupies a good half of the forty-page biography. Do read it, because Vasari really does give a sense of the high drama, the danger of a total fiasco, the conflicts of personalities, and the hero worship accorded to the architect after the cupola was competed; but you should be warned that his account does contain more than a few myths, some of which I will try to correct in the following very simplified sketch of what the main engineering problems were, and how they were overcome.

First, correction of a myth. It had always been intended to give the cupola something like the present unclassical shape, and it had always been intended to build it with two ‘skins’ or ‘shells’, as had been done, centuries earlier, in the octagonal Baptistery of Florence, less than 100 yards away. There too, we have one roof inside the other:

The problem was that the ribs of the cupola over the Baptistery, about half the size, would have been built by the normal method of ‘centering’—that is, by building a timber support in the desired shape, and dropping the wedged shape stones into the support one by one, until the final ‘keystone’ was inserted and the wooden centering could be removed. But the width of the octagon in the Cathedral—pictured below from the floor—was 140 feet, and the whole was to be 180 feet above the ground; thus it was just not possible to build a timber centering on that scale.

In the frantic years leading up to Brunelleschi’s appointment, it really did seem to many people that it would be impossible to complete the cathedral as planned, and that Florence would become the laughing stock of the whole of Italy. Brunelleschi’s solution was based on his first hand study of the Pantheon in Rome, a building which has a circular ground plan and a circular profile, and therefore a hemispherical roof (it also has an oculus open to the sky):

LEFT (FIXME slide missing, placeholder reads ‘A Pantheon photo B Foullier section to Sutre I R14–15 Luca 1997 L8 and 9’) and LEFT (FIXME slide missing, no placeholder)

A hemispherical roof can be built without centering, if one constructs fairly narrow courses right round the whole circuit; and there are no particular difficulties in scaffolding, at least in the early stages. Each time a new ring is complete, and the mortar has set hard, the overhanging roof remains as steady as a rock. Brunelleschi’s job was to adapt the method of building used in the Pantheon—with its relatively simpler geometry of the circle and hemisphere—to an octagonal structure where the stresses are radically different at different points of the ‘circumference’, and to do the same job twice over, once for each skin or shell, which would also have to be bonded together at intervals.

His solution is shown in this axonometric drawing above, which reveals that apart from the eight main ribs in each skin, rising from the corners of the octagonal drum, there are two median ribs between each of the main ones tying them together. He had this structure erected, octagonal ring by ring, with minute attention to the cutting and laying of the stones used in the lower courses, and of the bricks used higher up. The herringbone patterns (visible in fig. 17) are something that Brunelleschi learnt from his study of the Pantheon, and are apparently vital to the strength of the curving walls:

If every measurement was absolutely correct and every stone was positioned at exactly the right place and angle, each complete octagonal ring would possess, as nearly as possible, the geometrical properties of a circle.

If there were more time, I should like to exemplify some of the main engineering achievements of this project: how Brunelleschi invented new blocks and tackle to hoist up the 25,000 tons of brick and stone, or how he suspended a canteen for the workforce to save time. However, I shall have to content myself with showing you one image (fig. 18 ) where you can see the passageway between the two shells, the photo having been taken high up in the cupola where the sides begin to curve in more sharply towards the oculus:

If you feel the fascination of this heroic story, do go and read Vasari, or a subsequent history of architecture; but for our immediate purposes, all that really matters is that, in the year 1436, Florence did not become the laughing stock of Italy. It had instead acquired one of the wonders of their age, or, indeed, of any age—totally unbelievable whether you see it from a distance, or from close by; from the side, or from above; by day, or by night. That is my first ‘figment’.

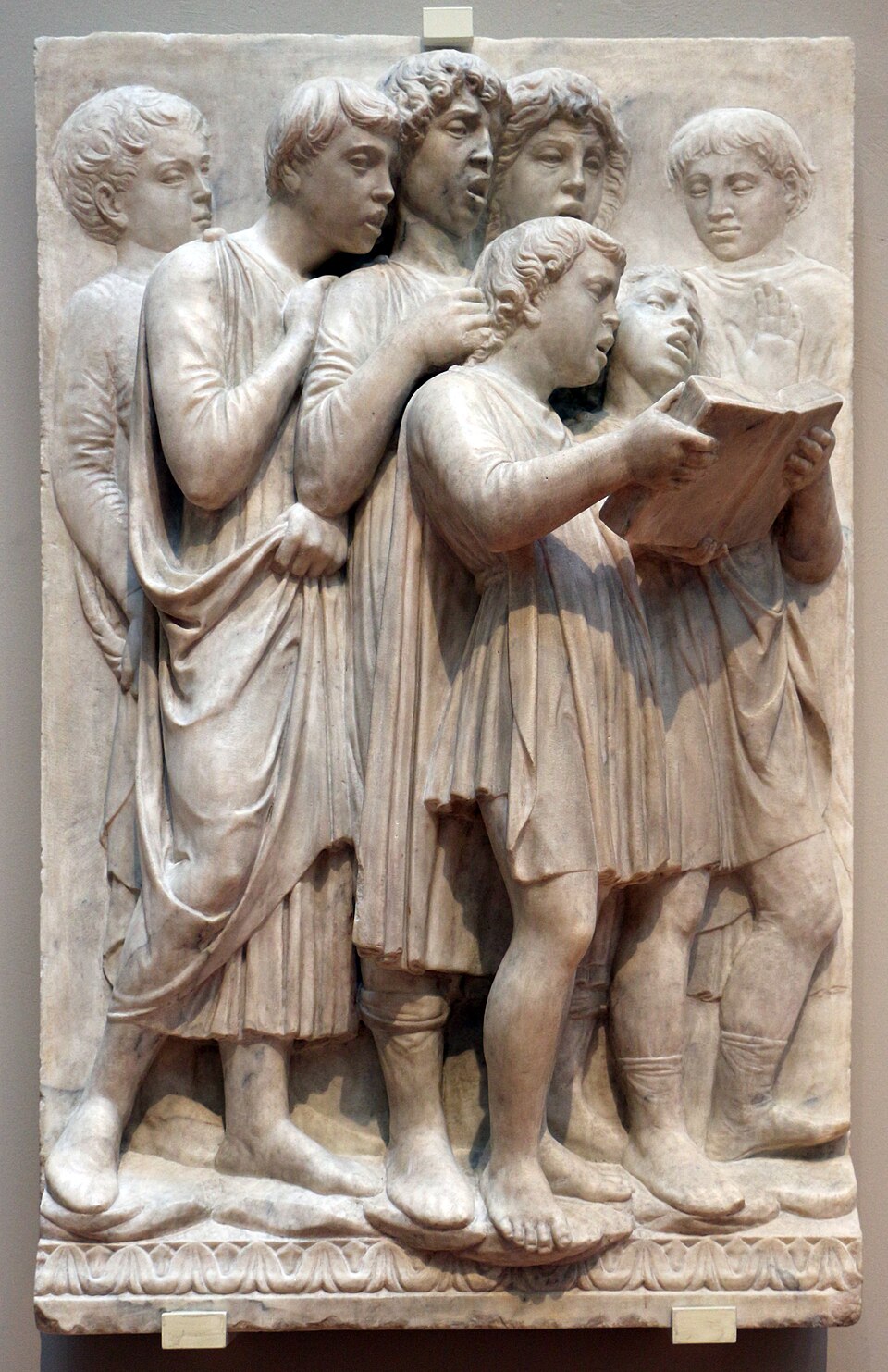

As the whole cupola began to curve over and inwards, and after a prolonged financial crisis from 1427 to 1431 when it was forbidden to spend any money on sculpture, the Wool Guild commissioned two marble galleries for the cathedral musicians. The first (by Luca della Robbia) was to be placed high over the door of the North (NE) Sacristy, overlooking the High Altar. The second (by Donatello) was to stand at an angle of 90 degrees, over the other Sacristy Door. You would have seen them something like this:

The first, on the left, was commissioned in 1431 and finished in 1438; the second in was commissioned in 1433, and finished in 1439. They are more or less the same length, 17 feet x 18 ½, and they are about three feet deep, large enough to hold a group of instrumentalists or a small organ (though the latest evidence suggests that they would not have been used by singers in the fifteenth century, who would have stood on the floor).

Each cantoria is supported on five brackets; and as you can see, the front surfaces are decorated with low relief sculptures, just over three feet high, which continue round the sides. In each case, too, the front surface was divided into four sections, either by pairs of pilasters (as in the left gallery) or by pairs of free-standing columns (fig. 21), so that in each cantoria the human figures are arranged to form four groups.

The subjects of the reliefs are derived from the Psalms, and especially the final sequence, in which we are told that we should ‘sing to the Lord a new song’, cantate Domino canticum novum, (149,1), ‘make melody with timbrel and lyre’ and ‘praise his name with dancing’ (149,3).

Donatello’s gallery, as you can see in the detail, is dominated by dancing; but Luca’s is explicitly inspired by the words of the very last psalm, 150, which is transcribed in full in lovely classical capital letters. Nevertheless, in general terms, all the reliefs on both galleries represent singing, playing instruments, and dancing—all in the service of the Lord.

I had intended to talk at some length about Donatello’s gallery, both for its own intrinsic merits, and as a foil to the other, but when I needed to make a substantial cut for reasons of time, Donatello was the obvious victim—so I shall pass straight on to Luca della Robbia.

Born in 1400, he was fourteen years younger than Donatello. He seems to have trained with the sculptor Nanni di Banco, who carved the Assumption of the Virgin over the side door on the North wall of the Cathedral; and the detail (fig. ¿fig:F6_20b?) of an angel there shows that Luca remained very close to his master’s relief style, at least in the first panels of his cantoria, for which the order was placed when he was 31 (this being his first recorded commission).

His brief had clearly been very precise—he was to illustrate Psalm 150 verse by verse. Where Donatello placed his rows of acanthus leaves, urns, shells and palmettes, Luca prints out the text of the psalm in full, top and bottom, thus providing the perfect description of his work, as we shall see:

Across the top, verses one and two:

1 Laudate Dominum in sanctis eius;

laudate eum in firmamento virtutis eius

2 Laudate eum in virtutibus eius;

laudate eum secundum multitudinem magnitudinis eius.

1 Praise God in his sanctuary;

praise him in his mighty firmament!

2 Praise him for his mighty deeds;

praise him according to his exceeding greatness!

Across the middle, verse three and the first quarter of verse four:

3 Laudate eum in sono tubae;

laudate eum in psalterio et cithara.

4 Laudate eum in timpani…

3 Praise him with the sound of the trumpet;

praise him with psaltery and lute!

4 Praise him with timbrel…

And across the bottom, the rest:

…et choro;

laudate eum in cordis et organo.

5 Laudate eum in cimbalis bene sonantibus

laudate eum in cimbalis iubilationis

…and [the] dance,

praise him with strings and organ!

5 Praise him with well sounding cymbals;

praise him with cymbals of jubilation!

FIXME: The following is given in the translation but not in the original: 6 Let everything that breathes praise the Lord!

The opening Alleluia is illustrated on the left end, round the corner:

It seems to be a close study of contemporary music making; and in the detail I have chopped off their legs (in any case there are not enough legs for their heads), so that we can see them even better. The boy trebles hold the single copy of the music, one reading with great concentration, the other letting himself go a little; the youth to the right, in much flatter relief, is clearly acting as choirmaster, displaying his hand like someone teaching sight reading by the hexachord method. The basses seem to be holding long notes, and there is a furrow of effort between the brows of one of them; while the place of honour is reserved for the tenor, with his straighter hair and forelock, who is resting his right hand informally on the shoulder of his neighbour.

This first panel on the front illustrates the first specifically musical command in verse three of the psalm: ‘Praise him in the sound of the trumpet’. Three trumpeters in profile, dressed in very short doublets and hose, blow lustily with distended cheeks, but without deafening the two youths whose heads (but not whose legs) we see on the right. The main sculptural charm, though, lies in the four little girls wearing knee-length dresses, with a high waist-band to give free movement. Two of them reach up to touch the long trumpets, while two others dance, as in Donatello, one ducking through the improvised arch while holding the hand of the other, who leans back, lowers her head, and executes the dance step with her left leg.

The next scene has a reversal of the sexes, and it illustrates the injunction to ‘praise him in the psaltery’, a cross between a zither and a harp. The instruments are held by teenage girls who stop the strings with one hand and pluck them with the other, while inclining their heads at various angles and singing with enjoyment and, indeed, some abandon. In the foreground below, we see two little boys singing and practising on their ‘psalteries’.

More girls are found in the next panel, but differently arranged. The two infant boys sit and point; two girls are facing inwards, singing; and they frame the two figures in the centre, who are praising the Lord in cythara, which Luca understands to be a small lute, with the four paired strings characteristic of this family. One sings the melody with some passion, her drapery stretched wide by the effort; the other stands slim and straight, her head slightly inclined, accompanying rather wistfully.

With the last scene on the top row of the front, we go back to the male sex, and to quintessentially ‘male’ instruments, because they are ‘praising the Lord with the drum’, in timpano. Luca understands this as the ‘tabor’, a drum so small you could attach to your waist and play with one hand if necessary, leaving the other free to play the pipe—which in this case, is a flageolet with just three fingerholes.

The nine-year-olds dance to the strong rhythms of a jig. It brings to mind the story of one of the actors in Shakespeare’s company, Will Kemp, who danced all the way from London to Norwich in nine days, accompanying himself with pipe and tabor—an act which earned him a pension for life!

We turn now to the four scenes between the brackets, the first of them being an illustration of the second noun in verse four, in choro—they are praising the Lord in dance:

Seven figures hold hands decorously in a ring dance, all aged between ten and twelve, apparently both boys and girls, and all but the one on the right singing as they dance. They are all very restrained when compared with Donatello’s urchins, but the figure in the foreground has something of a mischievous smile.

The second panel in the bottom row presents another contrast. The dancers give way to eight standing boys, grouped around the seated girl in the centre, who praises the Lord with a portative organ.

One of the boys on the left just listens intently, but on the right, some of the boys are obeying the other command in that verse of the psalm—to praise him ‘in strings’. You can see the top of a psaltery, while to the right again, a chubby hand is plucking the strings of another little lute of the kind we saw in the scene above—as Einstein said, ‘Der liebe Gott steckt im Detail’.

You will remember that verse five of the Psalm required us to praise the Lord with cymbals, but introduced a distinction between ‘euphoniously’ and ‘jubilantly’. These two indications of mood are represented separately in the last panels in this row.

We are back to girls, or possibly hermaphrodites, three on either side of a central figure, who is naked except for the garland which covers a crucial area; and they are striking their cymbals quietly, ‘well-soundingly’, with one of them holding a cymbal coquettishly close to her own ear.

The percussionists in the final scene, however, are really ‘jubilant’. No fewer than six pairs of cymbals are being clashed together, and the whole sextet are in vigorous motion, particularly the boy in the middle.

Psalm 150 ends, you remember, with another Alleluia, which is duly represented on the remaining side panel. Here we see a trio of singers, again apparently drawn from the life (like those in the other side panel), who are reading their music from a single scroll—counting hard, or concentrating like mad, on the tricky rhythms of their motet.

I am suggesting that the musicians on the side panels look like members of a fifteenth-century church choir, who are singing something a little more complicated than plainsong. And this might lead you to be curious about what kind of music would have been played in the 1430s, over the Sacristy doors, underneath the completed cupola of the Cathedral, near these two galleries…

Having completed my second ‘figment’, I turn now to the promised third. It is at this point that the text in this book must depart more than usual from what the words I used for the audience in the vast Babbage Theatre in Cambridge, where I was able to introduce a live performance, given by five members of the choir of St John’s College, of the very motet that had been specially written for the dedication of the Cathedral on 25 March 1436. As a reader, sadly, you will have to make do with my remarks about the words and the music of the motet (although it will not be difficult to find a recording readily available on YouTube). But even if you are unable to hear the voices (as you have been seeing all the images), the following pages may be worth your attention, because they will highlight some of the ways in which the words and music connect with each other, and with the architecture.

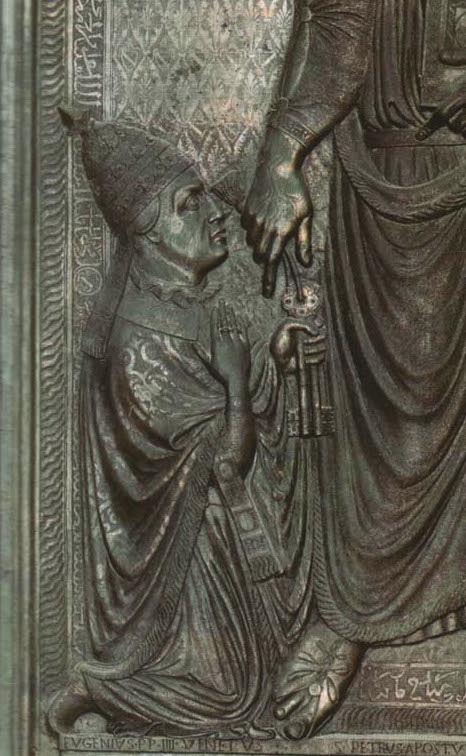

As I mentioned in the previous lecture, the Pope at the time was a Venetian, who had taken the name of Eugenius IV on his election in 1431. Three years later, he was forced to leave the unruly city of Rome, moving his court for most of the next nine years to Florence; and it was here that he hosted a sort of ‘ecumenical conference’ in 1439. The miniature below shows him outside Santa Maria del Fiore:

RIGHT (slide missing, no placeholder)

Among others in his retinue, the pope brought with him Leo Battista Alberti (on his first visit to Florence), and a small papal choir of about ten musicians. Among these was the most accomplished and most melodious composer of his time, the Frenchman Guillaume Dufay.

Dufay was the same age as Luca della Robbia, having been born between 1398 and 1400. Like so many musicians, he came from the Low Countries; but he gravitated to Italy, and first entered the papal choir under Martin V in 1428. He wrote a famous motet for the coronation of Eugenius in 1431, and another for the coronation of the Emperor Sigismund in Rome two years later. After an absence, he returned in the autumn of 1435 as ‘first singer’ in the papal choir, which by this time was established in Florence. The motet I am going to discuss seems to have been his first commission in his new role.

The day chosen for the ceremony of dedication was 25 March 1436, the Feast of the Annunciation—the feast par excellence of the Virgin Mary, to whom the cathedral is dedicated. The ceremony was extremely elaborate: they built a wooden walkway outside, at least a thousand yards long, to allow the enormous congregation, dressed in all their finery, to file into the cathedral in a dignified way.

It is also relevant to know that the Pope made a gift of a golden rose, standing just over two feet high, which was blessed and placed on the High Altar. This was the normal gift for a pope to make on a special occasion; and what you see above is the rose donated on a similar occasion 22 years later by Pope Pius II. However, such a flower had a special significance for the ‘City of the Flower’, Florentia, and for the cathedral of Santa Maria del Fiore.

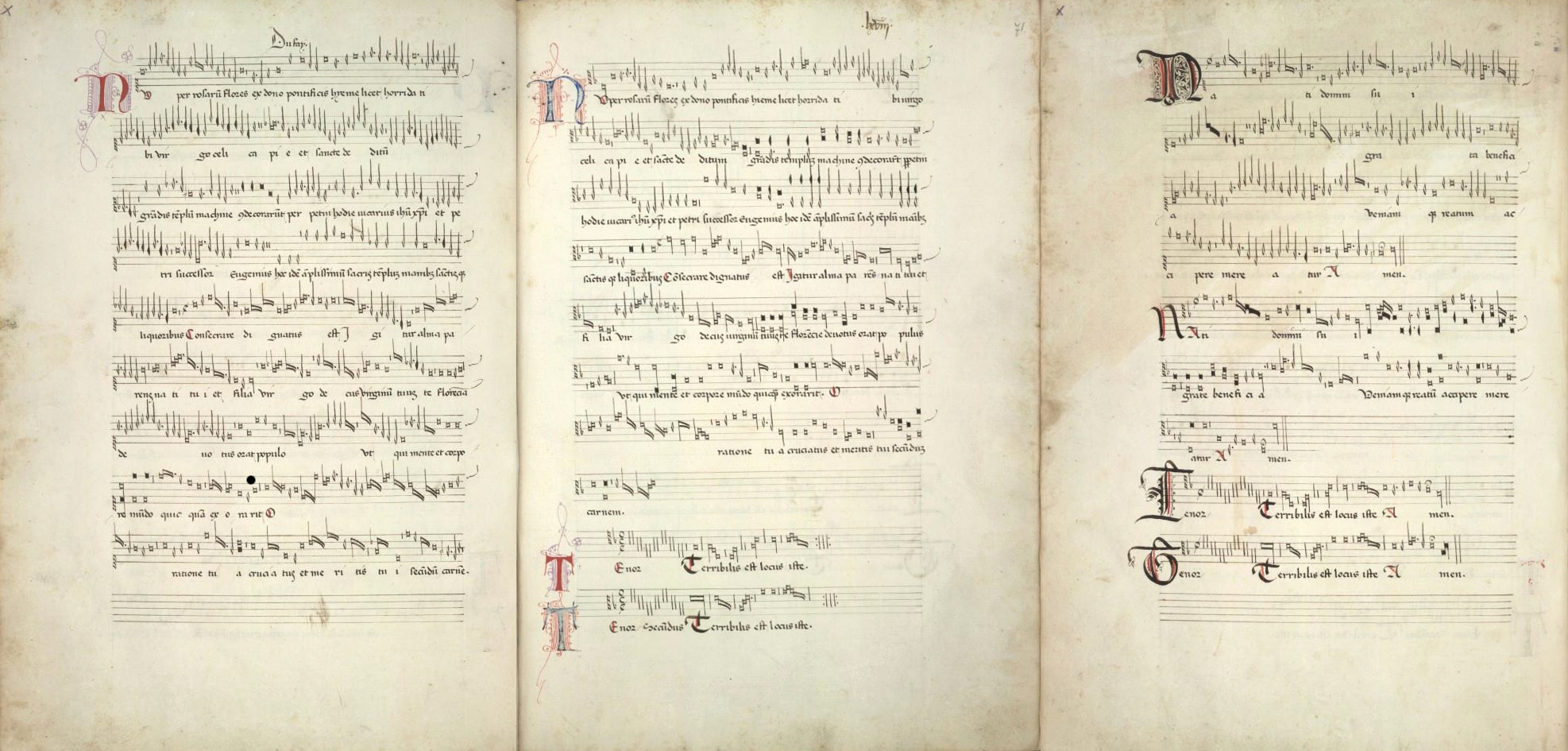

In general terms, we can say that Dufay wrote the same kind of piece as he had done for the coronations of Eugenius and Sigismund. It is an ‘isorhythmic motet’, a species of motet which had been invented in the remote years when the foundations of the cathedral were being laid, but which had apparently become rather old fashioned by 1430 and was now reserved for special occasions, like the one at hand. However, before I come to the tricky subject of ‘isorhythm’, I ought to say something about the nature of the polyphonic motet in general.

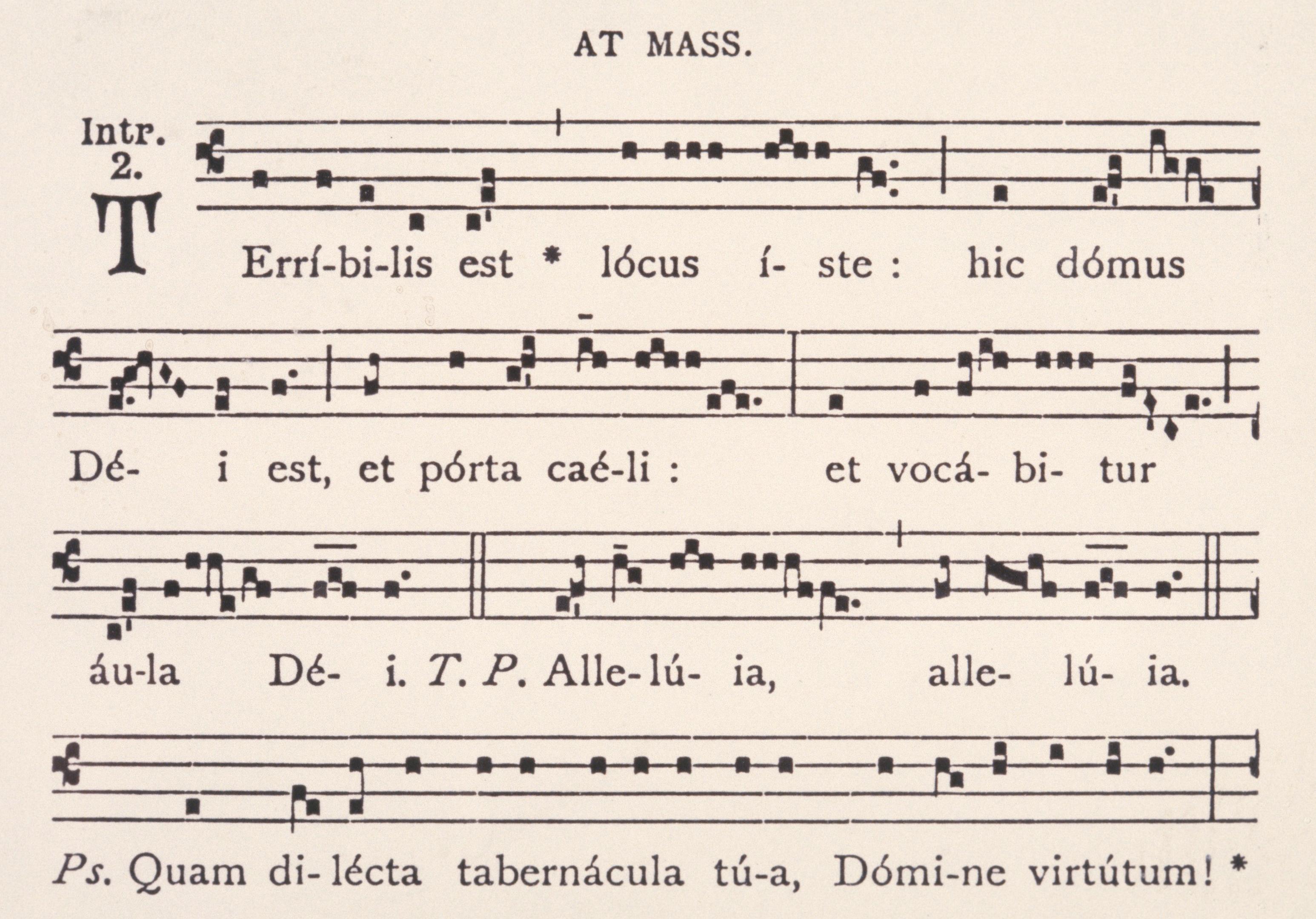

The genre had originated centuries earlier as a result of the practice of adding a descant to a monodic plainchant. As the form evolved, the process of composition went something like this (needless to say, I am simplifying drastically). The composer took the melody and words of an existing plainsong as the lowest voice in the composition, which carried or ‘held’ the melody, and was therefore called the tenor—the ‘carrying’ or ‘holding’ voice. To this, he added a separate text—a kind of commentary or paraphrase or meditation on the words of the chant—with a newly composed melody, sung by a higher voice. This was called the motetus, or ‘motet’—the part with the ‘little words’, ‘les petits mots’ or ‘les motets’. Later, composers added a third, even higher voice, with yet another text—which was known as the triplum, the third voice, which is where we get our word ‘treble’.

On this occasion, Dufay composed a triplum and a motetus to an existing tenor, but there is only one set of words for the two higher parts, and it is to these words we must now turn. The choice of the plainsong was self-evident.

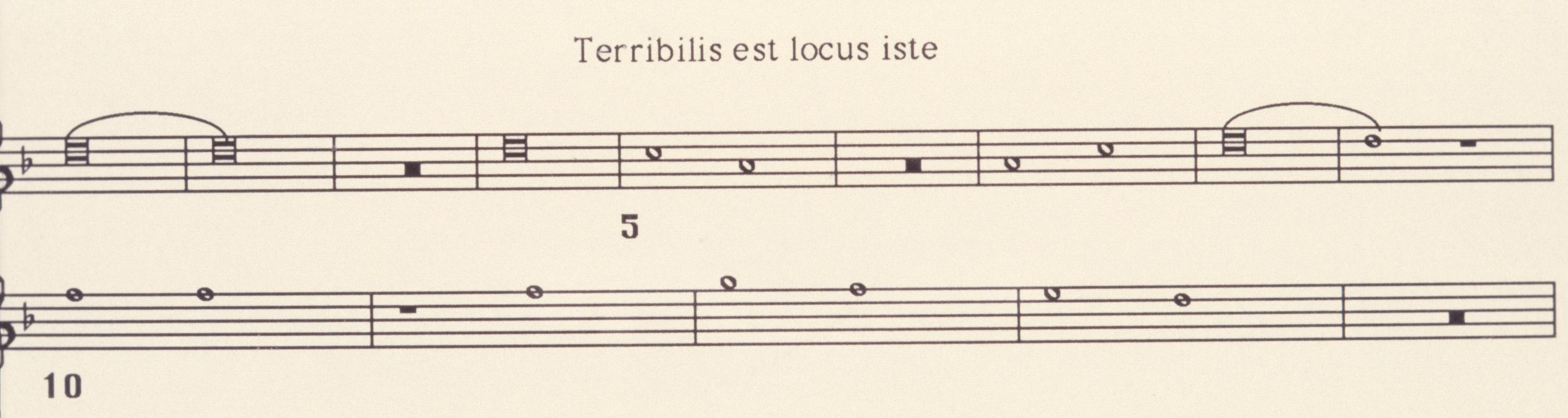

The introit prescribed for the dedication of a church was Terribilis est locus iste (fig. 42), a text that was perhaps in the mind of Captain Scott when he wrote of the South Pole, ‘Great God, this is an aweful place’. The text for the two upper voices was specially written by a competent humanist at the Papal Court (in principle, he could have been Alberti), and it falls into four sections or strophes, each of seven lines (most of which have seven syllables—metrically speaking—except that the last line of each section has eight syllables): 4 and 7, I remind you, are factor of the ‘perfect’ number, 28. I shall give present the text one strophe at a time, and clarify the meaning.

Nuper rosarum flores

ex dono pontificis,

hieme licet horrida,

tibi, virgo coelica,

pie et sancte deditum

grandis templum machinae

condecorarunt perpetim;

The first half the text, is taken up with narrative, with the first strophe giving the context. ‘A little while ago’—nuper, last week in fact—‘roseflowers given by the pope have decorated unfadingly’—being made of gold, they could flourish in winter and would never wither—‘the temple of great engineering skill, which is dedicated, piously and holily, O heavenly Virgin, to you.’

hodie vicarius

Jesu Christi et Petri

successor Eugenius

hoc idem amplissimum

sacris templum manibus

sanctisque liquoribus

consecrare dignatus est.

‘Today’, hodie, ‘Eugenius, the successor of Peter and Vicar of Christ, has deigned to consecrate the vast temple with his sacred hands and holy oils.’

Igitur, alma parens

nati tui et filia,

virgo decus virginum,

tuus te Florentiae

devotus orat populus,

ut qui mente et corpore

mundo quicquam exorarit,

In the second half, the text passes from narrative to petition, beginning with a typical invocation to Mary, which stresses her power to intercede and her relation to the people of Florence. ‘Therefore, bountiful mother and daughter of your son, maiden, glory of maidens, your devoted people in Florence pray to you that whosoever prays with pure mind and body for anything…’

oratione tua,

cruciatus et meritis

tui secundum carnem

nati, Domini sui,

grata beneficia

veniamque reatum accipere mereatur

Amen

‘…through your prayer and the merits of the suffering of your son incarnate, who is his Lord, should be found worthy to receive kind favours and pardon for their sins. Amen.’

Having presented the text, and introduced the motet form as a genus, I must say a few words about the ‘isorhythmic’ species. In the ‘isorhythmic’ motet, the composer begin by taking the melody or tenor of the chant (in our case Terribilis est locus iste), and imposing an arbitrary rhythmic pattern on the opening notes—arbitrary, in the sense that it is unrelated to the rhythm of the words.

In our case—and here you will begin to notice the presence of further factors of the ‘perfect’ number 28—Dufay has taken the fourteen notes used for the first four words, and given them values and rests that would stretch them out, in two groups of seven, for the equivalent of fourteen ‘measures’. This is what constitutes the basic unit of the motet, the ‘module’—what the musicians then called its ‘tally’ (from the Latin talea, meaning ‘stick’). (The term is related to the tally-sticks that merchants would notch and then split down the middle, so that both partners to a deal could ‘keep count’ or ‘keep account’, because the two halves ‘tallied’).

Normally, the composer would impose exactly the same sequence of note values and rests on the whole of the rest of the melody of the chant; and hence every section, every ‘tally’, would have exactly the same rhythm in the tenor: it would have isorhythm. (In our case, Dufay repeats the same fourteen notes, as well as the same rhythm). However, although one had to keep the rhythmic pattern, one could and did change the metre from perfect time to imperfect time (roughly, from 4/4 to 3/4), simply by changing the time signature; and one could halve the note values in both metres, by simply drawing a vertical line through the relevant time signature.

To express this in modern terms: if you had begun by taking your basic unit as a dotted minim, you could replace it, in the second talea, with a minim; in the next talea, with a dotted crotchet; and in the next, with a crotchet, changing all the other note values and rests to preserve the iso-rhythm.

We have dealt with the genus, motet, and with the species, ‘isorhythmic’; and I now want to present a little table summarising some of the distinctive structural features of Dufay’s motet, in order to make you aware of some of the ways in which Dufay used the factors of 28, and the factors of 6—as prescribed in the proportions of the Temple of Solomon—to bind together the music, the words, and the ‘immense temple’, the templum amplissimum, of the Cathedral of Florence.

Getting things to ‘tally’ (‘talea’ = ‘stick’)

The measures have the equivalent of:

6 minims in the 4 2 3 |

first talea second third fourth |

The approximate performance times are:

2 x 60 seconds for the 2 x 40 2 x 20 2 x 30 |

first talea second third fourth |

|

Each talea has The text is in each strophe has 4 x 7 |

14 measures without tenor 14 measures with tenor = 28 measures 4 strophes; 7 lines (mostly of 7 syllables). = 28 lines |

**TOM we need to fiddle the proportions of the table a bit.

The text has four strophes, then, and there are to be four repetitions of the musical talea. The strophes have seven lines (and four times sevens are 28). Dufay expanded each talea to a total of 28 measures by starting the motet with a further fourteen measures of unaccompanied music for the two upper voices alone.

**TOM, SOMETHING ISN’T QUITE RIGHT HERE. LEAVE THIS REMINDER IN PLACE…

Dufay made use of the possibility of varying the metre and the duration of the fixed rhythmic pattern by—to put it as simply as I dare—making the fundamental note value of the first talea equivalent to six minims in perfect time, the next to four in imperfect time, the next to two, before going back to perfect time (3/4), making each measure in the final talea equivalent to 3 minims.

As you can see in the table, the practical result of this is that, if you keep the value of the minim constant in performance, the fourteen-measure sections last approximately 60, 40, 20, and 30 seconds respectively—60, 30, and 20 being the dimensions of the Temple of Solomon (the ‘figure’ or ‘proto-type’ of the Christian church), while 40 and 20 are the figures prescribed for the division of the Temple into House of Prayer and Holy of Holies (prefigurations of the Nave and Choir).

However, the most interesting and compelling of the parallels between the ‘frozen music’ of the architecture, and the ‘architecture’ of the motet lies in the treatment of the tenor. Dufay does not use just one voice, but two. Underneath the normal tenor (in a position which was as new and original then, as it became commonplace later), he puts a bass line singing the same few notes, and almost the same note values and rests, as the tenor—but a fifth below, and half a measure behind, so that the two voice are in free canon. (It is therefore rather tempting to accept the suggestion, made by Charles Warren, that Dufay, who had been living in Florence for the previous six months, was inspired by the two skins of Brunelleschi’s shell, identical in profile, never touching, never getting any closer, but always following one another at the same distance.) All these connections mean that the four ‘tallies’ do not correspond with the four strophes:

Talea 1

Measures 1–14 (approx. 60 secs.)

|

Measures 15–28 (approx. 60 secs.)

|

The first talea has thirteen lines, so that we are almost half way through the text.

Talea 2

Measures 1–14 (approx. 45 secs.)

|

Measures 15–28 (approx. 45 secs.)

|

Talea 3

Measures 1–14 all on the first vowel, then (approx. 2 x 25 secs.)

|

**TOM. AS ABOVE, WE NEED TO FIDDLE THE LAYOUT

The second has eight lines, while the third has only three—but the fourth, with slightly more notes again, has the remaining lines of the text, the crucial petition being held back for all the voices to punch home with due solemnity:

Talea 4

Measures 1–14 (approx. 40 secs.)

|

Measures 15–28 (approx. 40 secs.)

|

I am aware that my explanation of the complexities of the form has demanded great concentration and left unanswered the all-important questions: What about the composer’s inspiration? What about the tunes? What is going on in the freely composed upper voices?

The questions can only be answered after listening to a good performance of the motet. But when you have tracked down a recording, you might like to focus your attention initially on such features as the following.

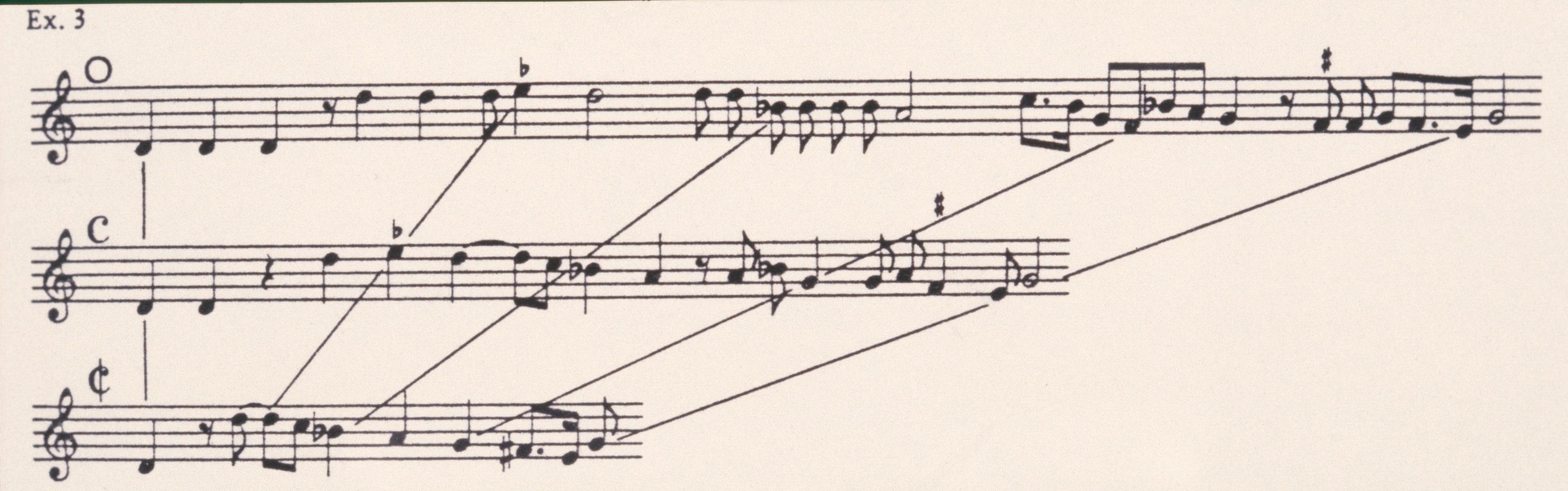

Given the changes in metre and note values, the setting of the four equal sections of the text could not be strophic (that is, repeating the same melody, as in a normal song); but there is a sense in which the last three taleae are a set of variations on the first, with each new melodic fragment being compressed (rather than expanded, as one would expect from normal Divisions on a Ground: the following example given by Charles Warren is very clear.)

The highest part (the triplum) is the least constrained and most rhapsodic, sometimes soaring high above the motetus, as you will hear on the climactic accipere at the very end. Surrender to its spell and enjoy the often purely melismatic decoration of individual vowels—the ‘a’ of beneficia, for example, or the ‘i’ of sui. The first vowel of Oratione in section three, on the other hand, takes up the whole first 14 bars of its talea in a strict canon for the upper voices.

RIGHT (FIXME slide missing)

Before that point, you will hear some lovely rhythmic interactions when both parts are syncopated to produce the kind of effects which Beethoven would come to love in his scherzos—and which are the very devil to perform. And although the two upper parts are usually independent rhythmically, there is one memorable moment when—after a brief canon on successor, one voice ‘succeeding’ the other—the name Eugenius is punched out simultaneously in block chords, before the treble soars again, in response to the word amplisissimum.

FIXME: BRUNELLESCHI’S CANTORIA: paragraphs cut for reasons of time.

So much then for the common features in the two cantorie. Now let us look at the differences, beginning with the one on the right. The sculptor was the long term associate and close friend of Brunelleschi, Donatello, born in 1386 (and therefore nine years younger than his friend), and now at the height of his powers and fame. He was between 47 and 52 years of age during his work on this gallery, and had just returned from a second prolonged visit to Rome, with his head teeming with motifs derived from classical sculpture, motifs which he here combines in a totally unclassical way.

LEFT

He treats the whole gallery like an entablature on a Triumphal Arch, but he fills the cornice with acanthus leaves separated by elegant urns, and he clutters up what should be the clean horizontal lines of the architrave with a row of palmettes over a row of shells. The frieze is divided up by those pairs of free standing columns, which, like the whole background, are encrusted with tesserae of light brown marble. He treats it like the frieze on the Parthenon with which you are all broadly familiar—there are no separate panels, but two blocks of marble treated as one continuous surface, with the figures forming a sort of procession moving from right to left.

And what figures, what a procession! Donatello found verbal inspiration in that phrase in the psalms about ‘praising his name with dancing’, and visual inspiration in the mischievous winged and youthful genii found in Roman sculpture, especially on sarcophagi. He creates a scene that reminds me of the rather raucous and indecorous end of an evening’s Ball Room dancing in the 1950s, when, after the foxtrots and quicksteps, we formed circles to sing and dance the ‘Hokey Cokey’, and then made a long eel like line, clasping the waist of the person in front to dance the ‘Conga’, often going out of the hall by one door to come back in at another. Or I am reminded of the 1940s, when I was at a local elementary school in an Essex village, and, in the playground, we simultaneously danced and sang ‘Oranges and Lemons’, or ‘The Farmer wants a Wife’.

Let us follow the turbulent boys, then, from this right end panel, where they duck under the arch of two cornets (just as we used to duck under the arches of arms), to the right end of the front:

FIXME: RIGHT

They do a little hula-hooping, and then begin to run past the figures in the background, the rearmost runner brandishing a tambourine in each hand, and trying to hear what the other in front—the one with the timbrels—is yelling back over his shoulder. Then, from side and rear views, we pass to a well-rounded little tummy, a particularly lively dance step, and a particularly loud voice, better highlighted in this detail:

FIXME: LEFT

Moving to the right again, after an emphatic counter movement between the columns, we come to a specific figure in the dance, where they all clasp hands high above their heads and ‘turn around’—because (as we used to sing in the Hokey Cokey), ‘that’s what it’s all about! Ho!’

FIXME: Search for “**” as well as “FIXME”.