This lecture deals with an artist who was probably about five years older than Masaccio, since he first appears in a document as a painter under the name ‘Guy Peterson’, Guido di Pietro, in 1417. Some time after that, but before 1423, he became a ‘Black Friar’ or Dominican—more precisely, he became a member of the reformed community of the Order of Preachers that had built an abbey (a badia) on the slopes below the ancient hilltown of Fiesole, about four miles away from the centre of Florence.

He continued his activity as a painter after becoming a friar, and his style was regarded by posterity as so pure, devout, and ‘spiritual’ that he became known as ‘Brother Angelic’ or ‘the angelic brother’, ‘Fra Angelico’. In what follows, however, I will use the simple name that he assumed on joining the Order of Preachers: John, or Brother John (‘Fra Giovanni’, or—if there was any doubt as to which Brother John—Fra Giovanni da Fiesole).

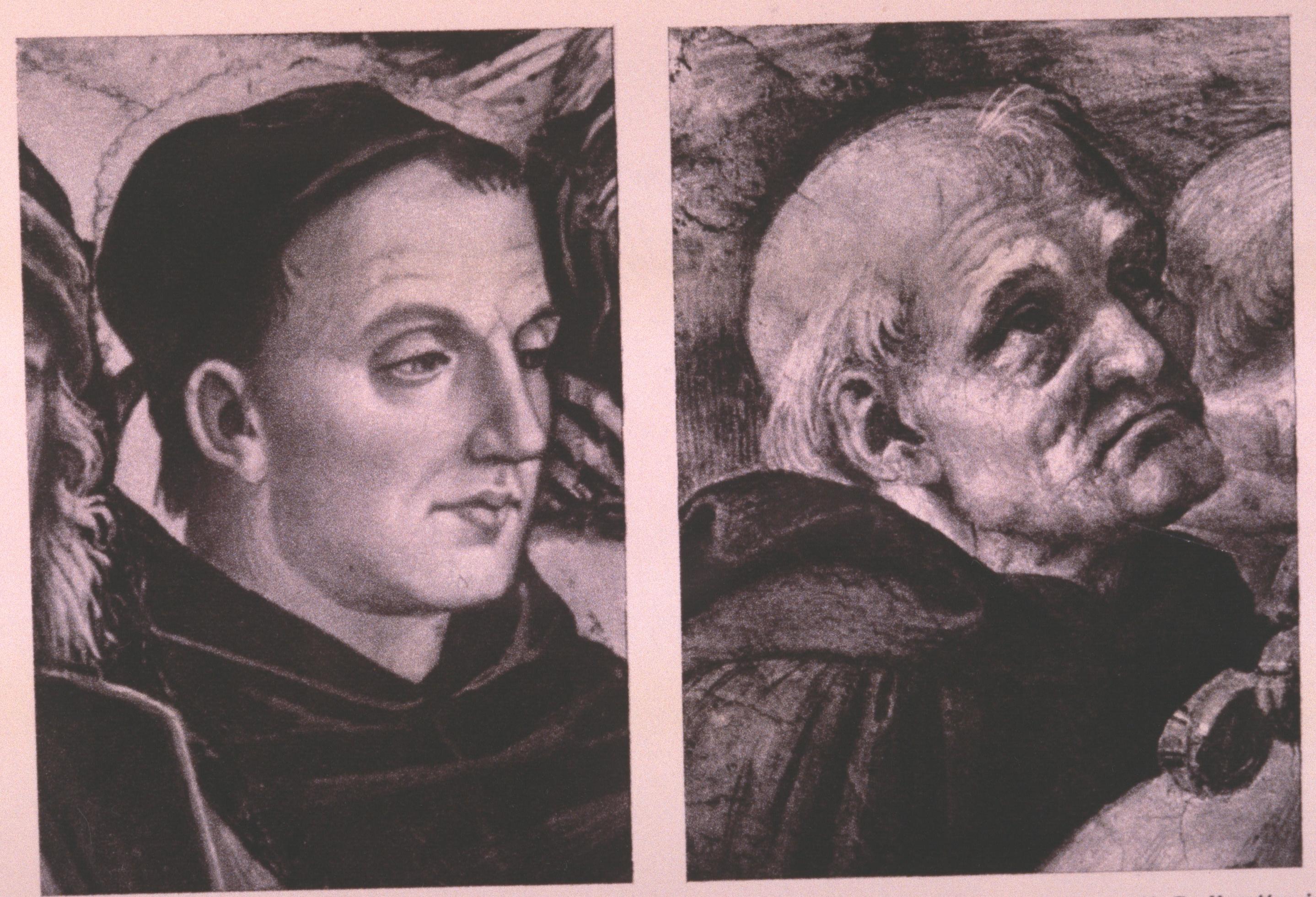

The point of reverting to the name he himself used is to get away from later clichés about his ‘angelic inspiration’ or, worse, his ‘artlessness’; and instead to see him as his contemporaries saw him (or as his near contemporaries saw him, in the case of the posthumous portraits by Signorelli and Raphael in fig. 1). For them he was a professional painter, who led a team of assistants producing religious artefacts on commission for patrons whose tastes were often conservative. As an artist, he was deeply influenced by the technical innovations in perspective and lighting introduced by Masaccio; and, as an administrator, he became the domestic Bursar, and then the Prior of his Convent, and was so good at his job that he was apparently considered a serious candidate for the Archbishopric of Florence.

His early training obviously made him familiar with the traditional methods of the medieval painters’ guilds; and it is often suggested that he worked for a time with an older painter who was also in religious orders—Lawrence the Monk, Lorenzo Monaco.

LEFT [FIXME: slide missing, placeholder reads ‘L. Monaco Coronation of V. central panel N. G.’]

In Figure [FIXME] 00, you see a large panel by Lorenzo of the Coronation of the Virgin, seven foot high, and now in the National Gallery in London, which was probably painted in the 1410s, and allows you to see something of the brilliance and intensity of his blues, reds and yellows (colours which we always associate with Fra Giovanni).

RIGHT [FIXME: slide missing, placeholder reads ‘Lorenzo Monaco Benedict scene in cream and gold N. G.’]

In Figure [FIXME] 00, you see a much smaller panel, only about one foot high, from a series depicting the Life of Saint Benedict. Again, concentrate on the palette: it is a ravishing study in creams and golds, with just one hint of pink and one of grey (in many ways, it is the National Gallery picture I myself would most like to own).

LEFT [FIXME: slide missing, placeholder reads ‘Lorenzo Monaco Annuciation In. Path. 9’]

In Figure 00 FIXME, you see an Annunciation by Lorenzo (now in Florence), again very small, only about two foot high. This illustrates to perfection the slim, curvilinear, weightless bodies that were still popular in Italian art in the early years of the fifteenth century, but which are not characteristic of Giovanni’s paintings, even in his earliest works—with one famous exception, as we shall see.

So much for his roots: now to the trunk and branches. There are about fifty surviving paintings from the first decade of Giovanni’s career as an independent master, that is, from about 1428 (the year of Masaccio’s death) to 1438. I would like to show you just three of these before we consider him as a narrative painter, in order that you can see something of his debt to Lorenzo Monaco and to fourteen-century traditions, and at the same time recognise his awareness of the avant-garde—the art of Ghiberti, Brunelleschi and Masaccio, and even of contemporary Flemish painters.

RIGHT [FIXME: slide missing, placeholder reads ‘Linaiudi cittquie B. A. 2 followed by detail B. A. 3’]

fig. ¿fig:O_An_00? is a triptych (the side panels may be folded over the centre), seven foot high, done for the Guild Room of the Guild of Linen-Makers, in an absolutely typical commission dated 1433. It shows the Virgin and Child, but has become chiefly famous for the twelve little angels, placed one above the other on the curving frame, each about fifteen inches high and each playing a different musical instrument (cf. Figure 00 FIXME).

RIGHT [FIXME: slides missing = Linaiuoli whole and detail of one angel alongside]

The dark, close-fitting robe in the detail in Figure 00 FIXME (very unlike those in Lorenzo) is set off by the splashes of bright red in the shoe, the flame, the wing feathers, and the drum, and above all by the very fetching ‘slash’ in the seam, that reveals the yellow of the lining. The face is much rounder than in Lorenzo, too chubby or ‘well-covered’ to reveal the bones or the muscles; the neck is carefully modelled; the arms and hands are very three-dimensional as they clasp and tap the drum. And it is the drum that for me is the key to the smooth, volumetric roundness of treatment in all parts of the human figure.

RIGHT [FIXME: slide missing,= Cortona Annunciation]

There is a similar inanimate ‘clue’ in my next example of Giovanni as a painter of devotional images, an Annunciation (Figure 00 FIXME), about four and a half feet high, perhaps painted a little earlier, which was commissioned by his fellow Dominicans in the Tuscan hill town of Cortona, where it still is. Giovanni’s necks are typically as smooth and round as the white marble columns you see here; and his heads are usually of the same proportions as the capitals, while the hair is as neatly bobbed or as close cropped as the carved acanthus leaves, as you can see very clearly in the case of the Archangel Gabriel. There is a lovely blend of the modern and the traditional in this image: Brunelleschi’s state-of-the art architecture is captured in a rather archaic, fourteenth-century perspective system (notice how the the side wall is folded out); the luminous pink of Gabriel’s robe—an absolute knockout as you walk into the room—is similar to what you might expect to find in Lorenzo, but the play of light over the whole surface makes you think of Masaccio (and the angel’s body is so much fuller underneath the robe).

LEFT [FIXME: slide missing, placeholder reads ‘Angelico Deposition B. A. 15’]

As my third example (Figure 00 FIXME), I show you the Deposition from the Cross, nearly 6 foot high, which was commissioned from Lorenzo Monaco for a family chapel in the Franciscan church of Santa Trinita in Florence. Lorenzo executed the figures in the pinnacles, but he left it unfinished at his death in 1425, and it was completed by Giovanni in the early 1430s. The shape of the frame is still completely medieval with respect to those pointed arches and the quatrefoils, and so too perhaps is the general effect of the bright, strong colours. But the grouping of the figures, receding into the landscape, has a complexity and a rhythm that demands the kind of analysis one would give to the figures in Masaccio’s Tribute Money.

The individual figures are modelled in the round, as you can see in the black-and-white photographs in the two details in fig. 2; a roundness which is very pronounced even in the pinched features of the third Mary, and in the little ‘colonnade’ of her fingers, or again in the long fingers of the male saint.

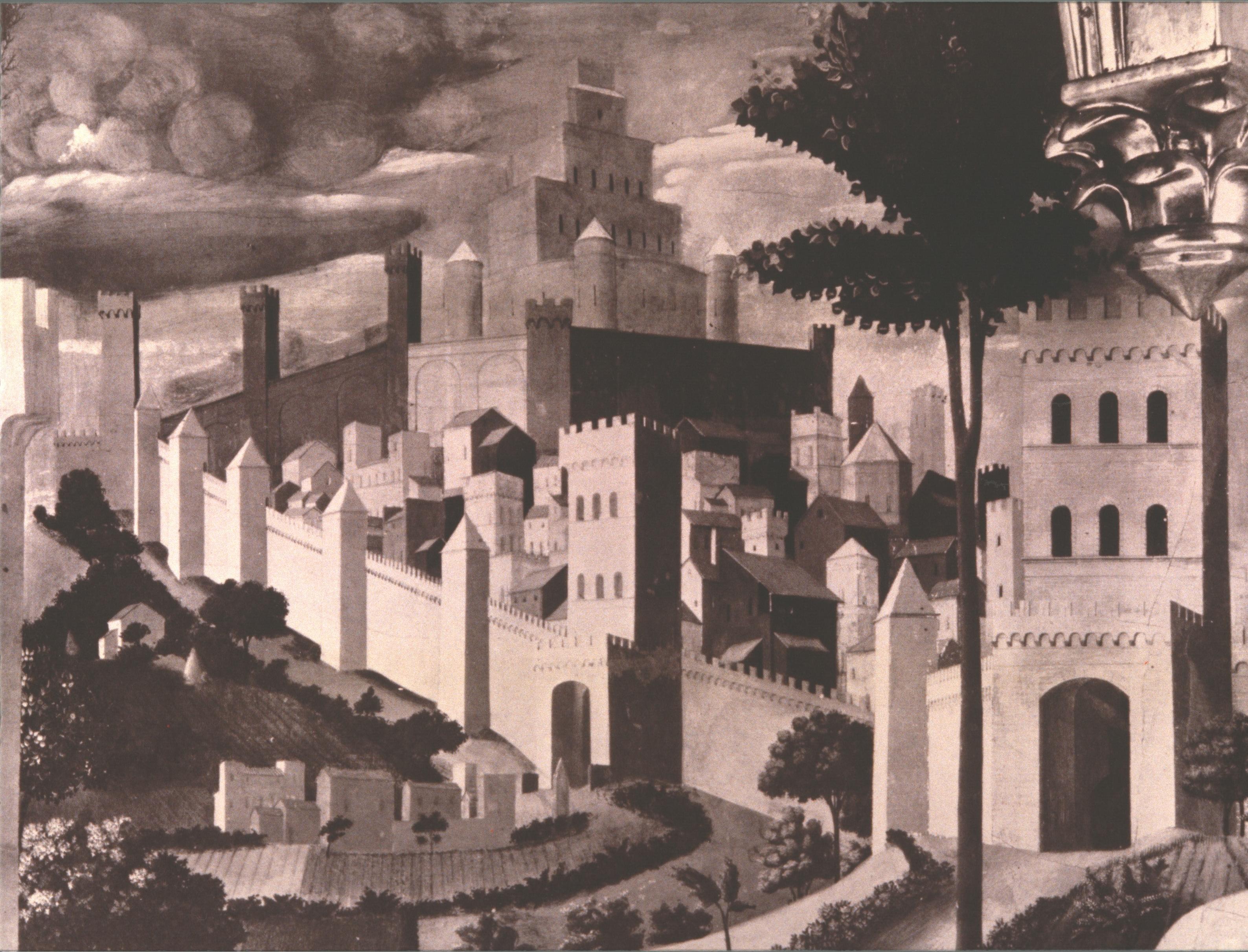

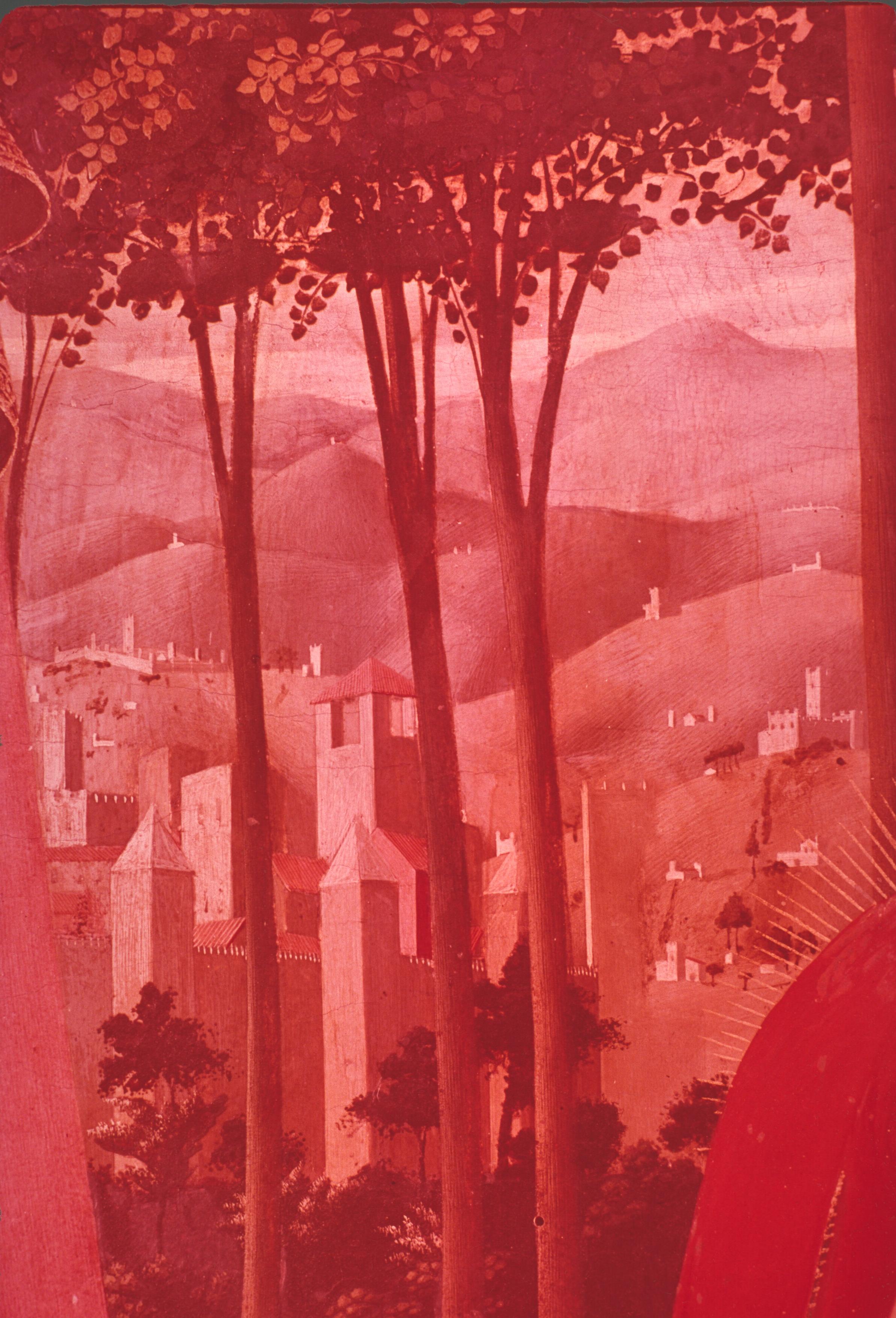

Very striking is the command of depth in the landscape, as for example in the detail in fig. 3, where up-to-date perspective is used to create simplified buildings and walls (almost like a wooden model of a city) which stretch far into the distance under the dark cloud. Elsewhere, (cf. fig. 4a) the landscape of brown hills becomes blue in the distance, and is dotted with little villas and farms just like the hills round Florence. The palm, too (fig. 4b) is modelled by light exactly as if it were a column with a slightly more elaborate capital; and the individual leaves of the neighbouring tree catch the sunlight at different angles.

The superb quality of the painting is also suggested by the portrait head in fig. 4c (said by some to be a portrait of the architect Michelozzo), in the contrast between deep brown and pastel blue, in the curve of the collar, the hint of his shirt, the short curly hair of his beard, the gleam of light on the lower lip, the gradations of colour and tone in his cheek, and his puckering eye.

So much, then, for the first ten to fifteen years of Giovanni’s career, and the various commissions for guilds, neighbouring towns and a Franciscan church. The next phase in his career brought him from Fiesole to Florence—you see a view of the city in about 1470 in fig. 5—and his work was now done almost exclusively for his own Order, in response to the patronage and influence of one man, whose family lived in the quarter you see below, between Santa Maria Novella, the Cathedral and the gardens inside the city wall:

I refer, of course, to the Medici family, and to Cosimo, whom you see in a detail from a portrait medal in fig. 7, which seems to be the source of all posthumous portraits. The family name means ‘doctors’ (medici), but their wealth and power—and their bad conscience—came from the bank which was founded by Cosimo’s father in 1397.

Cosimo had taste as well as power. In 1419, he was on the committee of his guild (the Arte del Cambio) that commissioned the statue of their patron saint, Matthew, from Ghiberti; and in the 1420s, he called in Brunelleschi to redesign and to supervise the rebuilding of the local church of San Lorenzo (Figure 00 FIXME).

RIGHT [FIXME: slide missing, church of san lorenzo]

Cosimo was sent into temporary exile in 1432, but returned in 1434 at the age of 45 to become the de facto ruler of the Republic (while scrupulously observing the letter of the Constitution, and keeping a fairly low profile) until his death in 1464 at the age of 75. He began to rebuild the family home too, such that eventually it would take on the form you see in fig. 8:

He played a very prominent role in foreign affairs, allowing the Pope, Eugenius IV, to hold his court in Florence during the 1430s; and he agreed to act as host to an important ‘summit conference’ between the Catholic and the Orthodox churches in 1439: the formal sessions were held in Santa Maria Novella, and, incidentally, gave Florentines a vivid glimpse of eastern beards, eastern costumes and eastern hats. With the support of Pope Eugenius, Cosimo evicted some Sylvestrine monks from their rundown convent near the family palazzo; and he contributed generously to the building and decoration to a new Dominican convent, the famous church and convent of Saint Mark.

RIGHT [FIXME: slide missing, view of the exterior of san marco]

The architect he chose was Brunelleschi’s heir, Michelozzo; and in Figure 00 FIXME you see the library he designed:

LEFT [FIXME: = slide of interior of the library at S. Marco B. A. 19’]

The painter he chose was Fra Giovanni da Fiesole, whose first task, between 1438–1440, was to produce an altarpiece for the high altar in the conventual church, which you see in Figure 00 FIXME. It is nearly 8 foot square, and shows Mary and Jesus on a classical throne.

LEFT [FIXME: = slide of Pala di S Marco, e.g. from Hood, plate 85]

In principle, the composition is like that in Masaccio’s Pisan altarpiece (Figure 00 FIXME):

RIGHT [FIXME: Masaccio’s Pisan altarpiece, slide presumably in relevant lecture]

But you can see that Giovanni’s altarpiece is now a single huge panel, instead of a fourteenth-century polyptych made up of several units. The vanishing point is much higher than in Masaccio; the foreshortened square of the Anatolian carpet creates a very generous space in front of the throne, while the curtains are drawn back to reveal a deep garden of funereal conifers. The grouping of the six saints on the edges of the carpet was absolutely revolutionary for an altarpiece. On the left, stand three famous saints of antiquity: the evangelists John and Mark in conversation, and the Deacon Lawrence (San Lorenzo); and on the right, three modern saints, two of whom being Black Friars (Dominic himself, and Peter Martyr), while between them stands the Grey Friar par excellence, Saint Francis.

Kneeling in the very foreground (more or less where one might have expected the tiny figure of the donor in profile) there are two further saints, one of whom gazes up at the Virgin in adoration, while the other looks out at us, with an unusually intense expression. Both these saints wear the robes of the medical profession; and they are in fact Cosmas and Damian, the patron saints of doctors in the middle ages, and for that reason the patron saints of the Medici family—indeed some say that the suffering face of Cosmas is a portrait of Cosimo.

The San Marco altarpiece used to have a predella below, as shown in fig. 9, with a series of small narrative panels telling the story of Cosmas and Damian, as recounted in The Golden Legend. I have yet to come across any set of illustrations to the Legend which seem more faithful to the spirit and even to the letter of the text, and so—although my images are not of very good quality—I am now going to reassemble the scattered panels (currently dispersed in Washington, Dublin, Paris, Munich and Florence), and bring back to life the little-known ‘medical’ saints who were the patron saints of the ‘Medici’.

In fig. 10, you see the first panel in the narrative (letter B on the diagram in fig. 9). It was originally tucked round the corner of the altarpiece, on the left: and measures only about fifteen inches by eighteen inches.

What you see is domestic architecture, drawn very carefully but reduced to its essentials. A plastered wall has an archway which opens into a plainly furnished bedroom. The wall then turns a corner, receding to open up a little courtyard, then dropping in height to support a large bowl with plants, to suggest the presence of a garden behind. The architecture is severely functional in the additional sense, too, that the arch and the courtyard act as frames to two distinct moments in the story.

As always, the colours contribute much of the pleasure. There is a lovely soft harmony of magenta, shading first into pink and then into brownish purple, set off by splashes of yellow, red and blue. And you will have noticed Giovanni’s attention to the fall of light and to the selective shadows which it casts (look at the bedside stool and table), and also the way the highlights gleam on the sheet and the doctor’s hat-band, or on the floor of the room glimpsed through the courtyard door. But let us come on to the story as it is told in The Golden Legend in the entry for September 27th:

‘Cosmas and Damian were brothers and were born in the city of Egea. They were skilled in the art of medicine, and had been endowed by the Holy Spirit with such grace that they healed all ills, of men and beasts, serving all without recompense. A certain lady named Palladia, who had expended all her wealth for the services of physicians, came to them and was completely healed’ (Giovanni has enhanced their virtue by having them pay her a ‘home visit’).

‘Thereupon she offered a meagre gift to Damian, and when he declined to accept it, she enjoined him with dreadful adjurations (cf. detail in fig. 11). At this he consented to accept the gift, not indeed from cupidity, but to satisfy the good intentions of the giver. When Saint Cosmas learnt of this he forbade that his body be buried with the body of his brother’—you must keep that in mind for later. ‘But in the following night the Lord appeared to Cosmas and acquitted his brother of blame for receiving the gift.’

So much then for the first scene. We now come round to the front of the original predella, where we would have found the second panel (fig. 12), which presents us with a much more elaborate architecture:

Classical pilasters frame marble panels and support a classicising entablature (ornamented with little roundels), on the top of which there stands (a ‘vernacular’ touch) three bright-red earthenware flower bowls foreshortened from below, while a loggia on the right protects the statue of a pagan, ‘martial’ god (he is naked and carrying a spear), and yet allows just enough space for us to glimpse a street and the sky. Add to these architectural clues the exotic, oriental hats of the figure on the throne and of his official, and it should be clear that we are in front of the palace of a pagan ruler somewhere in Asia Minor. The question you should be asking is, of course, why are there now no fewer than five figures with halos in front of this man in authority? The answer will revealed in the words of the Legend; but before we read them, take a moment to enjoy the colours. A very dark green lawn with flowers (a kind of artificial turf that Giovanni’s workshop could always roll out on demand) sets off the softer tones of the building and of the foreground soldier, while characteristic splashes of red, yellow and blue are distributed all over the surface in hats, clothes, and, not least, bright socks or hose. Notice too a feature which I do not remember seeing in any earlier painting, that is, how the back of the head or hat projects through the flat haloes of two of the brothers (where anybody else might have foreshortened the halo). The Golden Legend continues:

‘When the brothers’ fame reached the ears of the Proconsul Lisias, he had them brought before him and questioned them as to their names, their homeland, and their fortune. The Holy martyrs answered: “Our names are Cosmas and Damian and we have three brothers; are homeland is Arabia; as to our fortunes, Christians have none.” The Proconsul then ordered them to bring their brothers, so that they might all worship the idols together’.

It is clear, therefore, that Lisias’s gesture (with his right hand reinforcing the left) is towards the pagan idol on its column in the loggia.

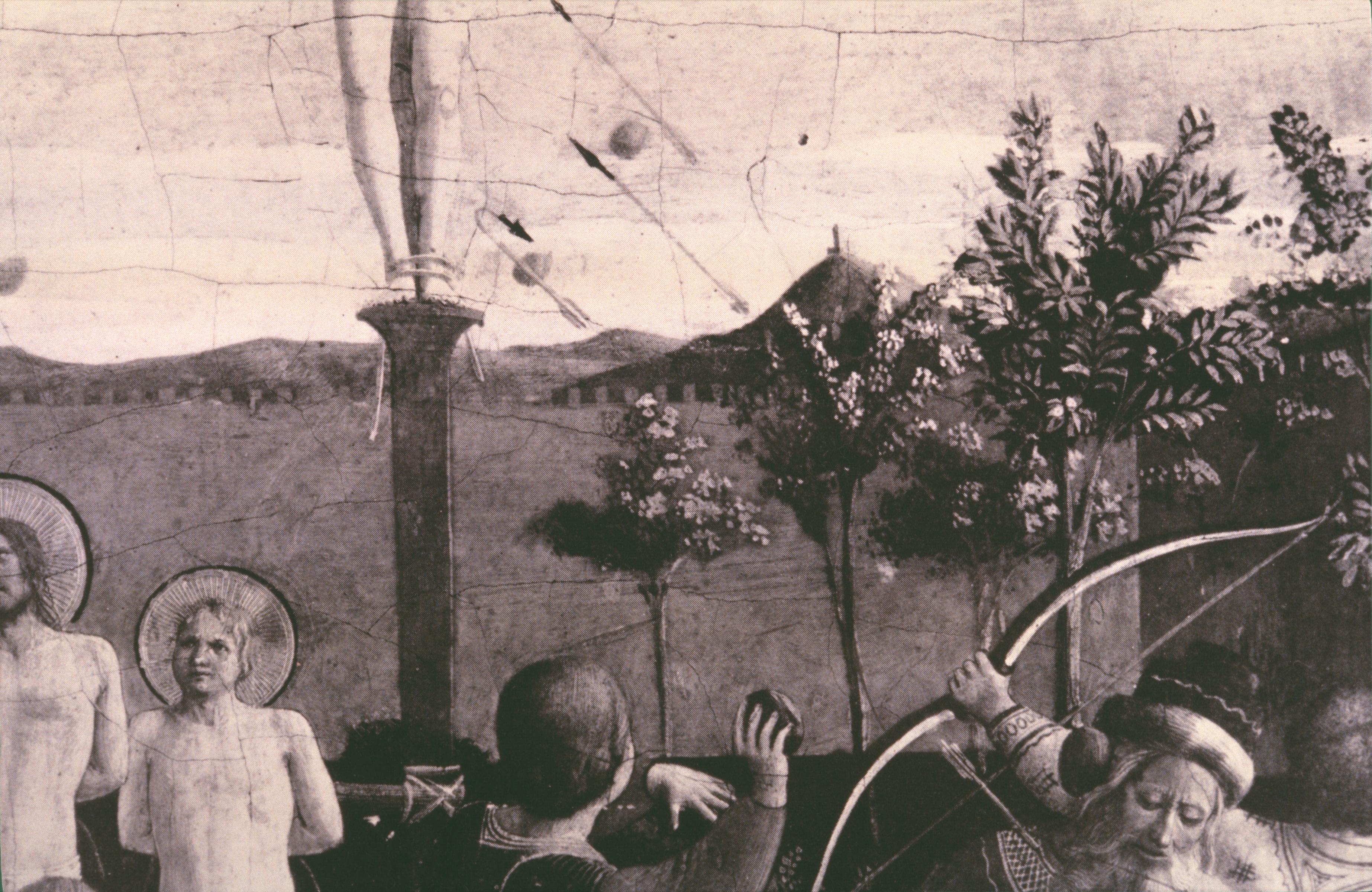

The next panel (fig. 13) forms a pair with its predecessor. The built-forms (wall, house and castle) are placed lower and to the right in order to admit a hill, an expanse of sea, and an open space, so that these three different backgrounds may act as ‘frames’ to several distinct moments in a story which is suddenly packed with action. Again, please absorb the colours, and details like the charming oriental pigtail (cf. fig. 15), before reading the narrative:

‘Seeing this the judge said to them: “By the great Gods, you conquer by means of sorceries, since you mock at torture and you calm the sea! Teach me your arts, and by the God, Hadrian, I shall follow you!” No sooner had he said these words than two demons appeared and struck him rudely in the face’ (see fig. 15), ‘so that he cried out: “I implore you, good men, pray for me to your God!” And at their prayer the demons straightaway departed’.

The fourth panel (fig. 16) allows just a glimpse of sky over the very tall palazzo (with proportions like those of the future Palazzo Medici) on the left. In the centre, it uses rusticated stone-block architecture, typical of a medieval commune, to suggest the lower storey of a fortified town hall. On the ashlared ceremonial balcony, we recognise the Eastern headgear of Lysias and his court (colourfully dressed as always). All this forms a perfect foil to the five brothers, who are roped together, back to back, in foreground. The story runs:

‘At this said the judge said: “See how angry the Gods are with me, because I thought of abandoning them! I shall no longer suffer you to blaspheme my Gods!” Then he commanded them to be cast into a raging fire; but it did them no hurt, whereas it leapt forth to a great distance and destroyed many of the bystanders’.

This is the purest Golden Legend material in every possible way, and once again Giovanni rises to the occasion. Nevertheless, as well as asking you to admire the red ‘dandelion’ of the flames, the animation of the guards in their brilliant costumes, or the unforgettable man behind his shield, I should remind you of scenes that were to take place fifty years later before a real Palazzo della Signoria—this time in Florence—when a Dominican from Saint Mark’s, who had successfully challenged the Medici and defied the Pope, made bonfires to destroy the ‘vanities’ of art-loving Florentines, and was himself later burnt alive in the square. I refer, of course, to Savonarola.

[FIXME: typescript gives RIGHT slide missing, placeholder reads ‘Bonfire of vanities + head of Savonarola, used in Medici lecture c. 1993’]

The scene represented in the very centre of the predella was the Entombment of Christ—but we may pass straight on to the sixth scene our story, shown in Figure 00 FIXME (letter G in the diagram in fig. 9), with its two crosses rising to the top of the frame. There are virtually no buildings to speak of, and half the surface is given over to a lanscape and a broad area of sky.

[FIXME: RIGHT = Scene of crucifixion of Cosmas and Damian, now in Munich, Hood p. 115 if necessary to scan]

The picture presents as one scene two further attempts by Lisias to put the brothers to death. As you will read, both the attempts can be said to have ‘boomeranged’. After torturing all of them in vain:

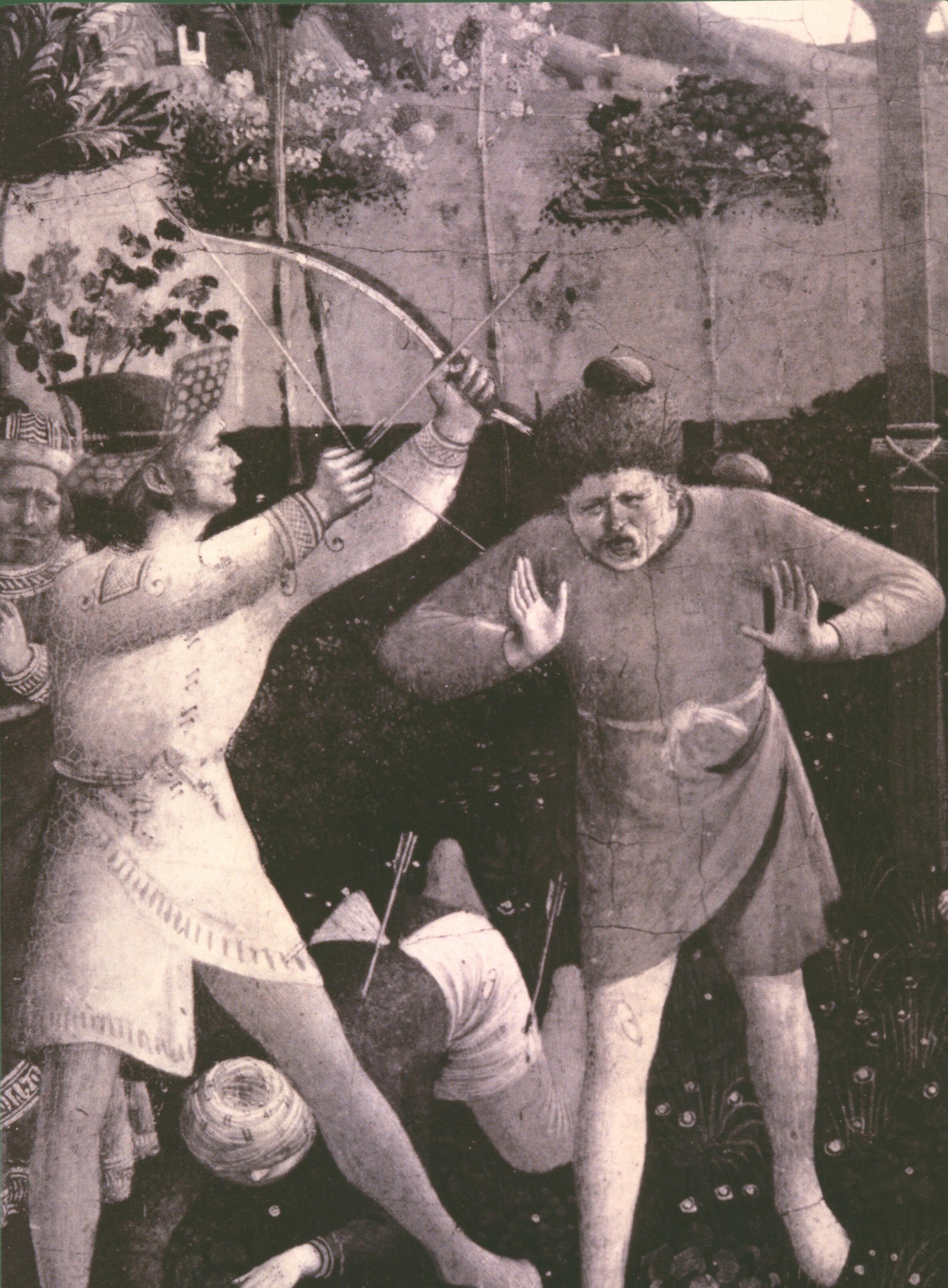

‘He caused the three younger brothers to be put back in prison, and he had Cosmas and Damian crucified, bidding the people to stone them. But the stones turned back upon those who hurled them, wounding a great number’ (cf. detail in fig. 17).

The brothers have survived fire, stones and arrows; but their luck cannot hold forever, and their end, as told in the Golden Legend, comes quickly.

‘Seeing all his efforts set at naught, the judge almost died of despite, and he had the five brothers beheaded at break of day’.

Their execution is the subject of the seventh panel in fig. 19.

FIXME: Also search for “00”.

The executioner is going at his work with all the élan of Lewis Carroll’s ‘Beamish Boy’. The ‘vorpal blade goes snicker-snack’, and the haloed heads are off the unnamed brothers before their kneeling bodies have had time to keel over, or the arterial blood to stop pumping out. The involuntary humour of this area helps to keep the emotional temperature low. We might ‘feel’ for Cosmas and Damian themselves, who kneel pinioned and blind-folded, but really we remain as serene in mood as the brightly dressed soldiers of the escort party, or the two bearded officials from the court.

Indeed, the most ‘moving’ detail in the composition is probably the group of five cypresses, one for each brother, set against the dawn sky in yet another fairy-tale landscape created by realistic perspective and a simplified but convincing recession of hills that reminds us of Giovanni’s Deposition.

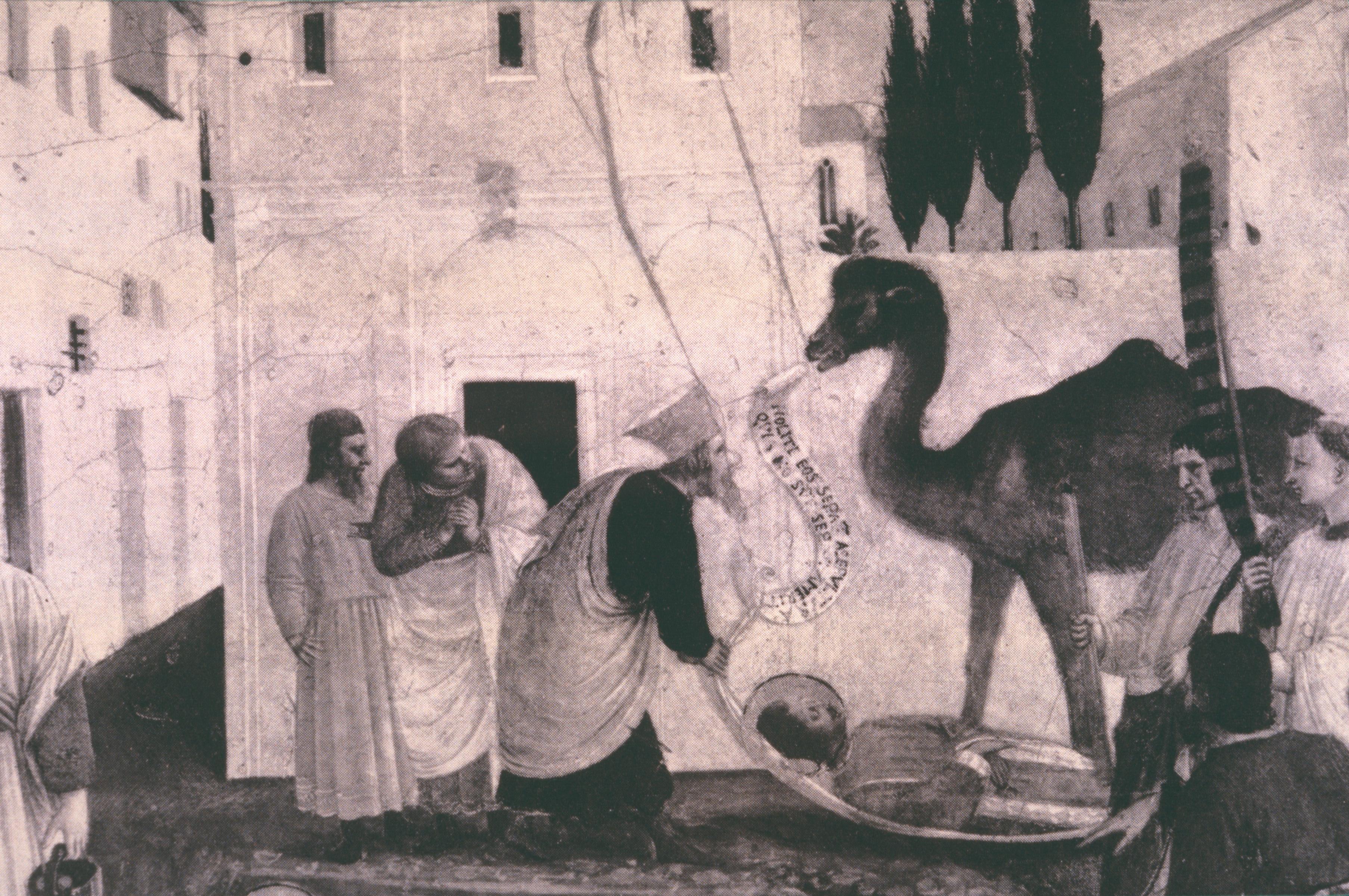

With the next panel, again forming a pair with its predecessor, we would have come to the right-hand end of the predella. Once again, there is a contrast between a patch of open sky and the unadorned buildings. These are typical of many a small hill town in Tuscany, and are painted with a perspective that creates quite a lot of space in the piazza (but not enough), and hints at a good deal more space behind, thanks to the four receding cypresses in the cemetery next to the church.

A cleric, assisted by two acolytes, recites the words of the committal, facing his colleague, who is holding aloft a long, thin banner on the opposite side of the shallow grave, which has been scooped out in the piazza by the peasant with his mattock. Four of the brothers have been laid in the grave, their severed heads in the correct position, while the fifth (who must be either Cosmas or Damian, since he is wearing doctor’s robes, like the corpse nearest to us) is being dragged away using his shroud as a ‘sledge’. With that enigma, we come to the miracle which justifies the scene. In The Golden Legend, the story goes as follows:

‘Then the Christians mindful of the command that Saint Cosmas had given them decided to bury the martyrs in separate tombs. But all at once a camel came up, and speaking in a human voice, bade them bury the saints in one and the same place’. (In the detail in fig. 21, you may be able to read the Latin words in the cartouche proceeding from the camel’s mouth: Nolite eos separare…)

At this point, the author of The Golden Legend seems to round off his tale with the words: ‘They suffered under Diocletian, whose reign began about the year of the Lord 287’. But the story should have reminded you of the Prologue (the panel tucked round on the left-hand side of the altarpiece), and this in turn should make you expect that there was still one more scene to come, hidden round the corner to the right. Here it is in fig. 22:

In this scene, we are shown a posthumous miracle, which is as totally unpredictable as the scenes of the brothers’ martyrdom were routine; and we could never interpret it without the words of The Golden Legend to help us. Cosmas and Damian reappear, without their three siblings and specifically in their role as doctors—hence their robes—in a sick-room. The very plainness of the room—with its ‘healthy’ mattress on a ‘healthy’ pinewood support, above a clean pinewood floor, where you can see just one tiny stool and a pair of ‘healthy’ sandals—allows Fra Giovanni to show the light falling from a hidden window in the passage, or coming in from the visible window to catch the underside of the bed curtains, tossed over the rail, and casting a shadow from them onto the wall. The story goes like this:

‘Pope Felix erected a noble church in Rome in honour of Saint Cosmas and Damian. In this church, a man whose leg was consumed by a cancer devoted himself to the service of the Holy Martyrs. One night as he slept, the saints appeared to him, bringing salves and instruments, and one said to the other: “Where shall we find new flesh, to replace the rotted flesh which we are going to cut away?”. The other replied: “This day an Ethiop was buried in the cemetery of Saint Peter in Chains. Go and fetch his leg, and we’ll put it in the place of the sick one!”. Thereupon, he hastened to the cemetery and brought back the moor’s leg, and they cut off the leg of the sick man and put the other in its place’.

The conclusion is that the man woke to find himself healed—but with a black leg!

For the next ten years, Fra Giovanni was kept pretty busy in San Marco itself, where he obviously made himself master of the very different, bolder technique and of the paler colours which are required in fresco painting. He and a team of assistants decorated the cloister of the convent and its cells with a famous series of frescos depicting subjects drawn from the New Testament.

FIXME: LEFT and RIGHT [LEFT ‘Angelico Annunciation B. A. 26’; RIGHT slide missing, no placeholder]

What you see in Figure 00 FIXME is his best known Annunciation. Notice how Mary’s willowy, shoulderless body has the proportions we associate with the art of Lorenzo Monaco (cf. Figures 00 above), but also how she sits in a loggia with arches and columns that seem to be part of Michelozzo’s cloister in which we find the fresco, painted with a sure command of modern perspective.

Giovanni’s fame as a fresco painter obviously spread far and wide, and he was summoned to Orvieto in 1446, where he began work on frescos in the cathedral depicting the Last Judgement, breaking the contract when Pope Eugenius called him to Rome

FIXME: RIGHT and LEFT [RIGHT slide missing, no placeholder ; LEFT slide missing, placeholder reads ‘Rome c. 1580 to Sistine ? Oct 90’ [At this point the RIGHT carousel has a run of images that don’t seem to be used elsewhere]

He remained in Rome under Eugenius’s successor and between 1448 and 1450, he frescoed for the new Pope a personal chapel with the stories we shall study in the final part of this lecture). He was back in Florence as prior of St Mark’s from 1450–52. But it was in Rome that he died in 1455; and it is there you will find his tombstone (fig. 24), showing him in his friar’s habit.

The new Pope, elected in March 1446, was a Florentine who took the name of Nicholas V. He was a distinguished ‘humanist’ (in the technical sense of the word); a contemporary of Alberti, a Greek scholar and a bibliophile. He was the first pope for 150 years to initiate a programme of rebuilding in Rome, beginning with a wing in the Pope’s palace next to St Peter’s, but drawing up plans which, by 1580, would transform Rome into the flourishing city you see in this map, with the new St Peter’s virtually complete:

RIGHT [FIXME: slide missing; it’s with the first of the Sistine Chapel lectures]

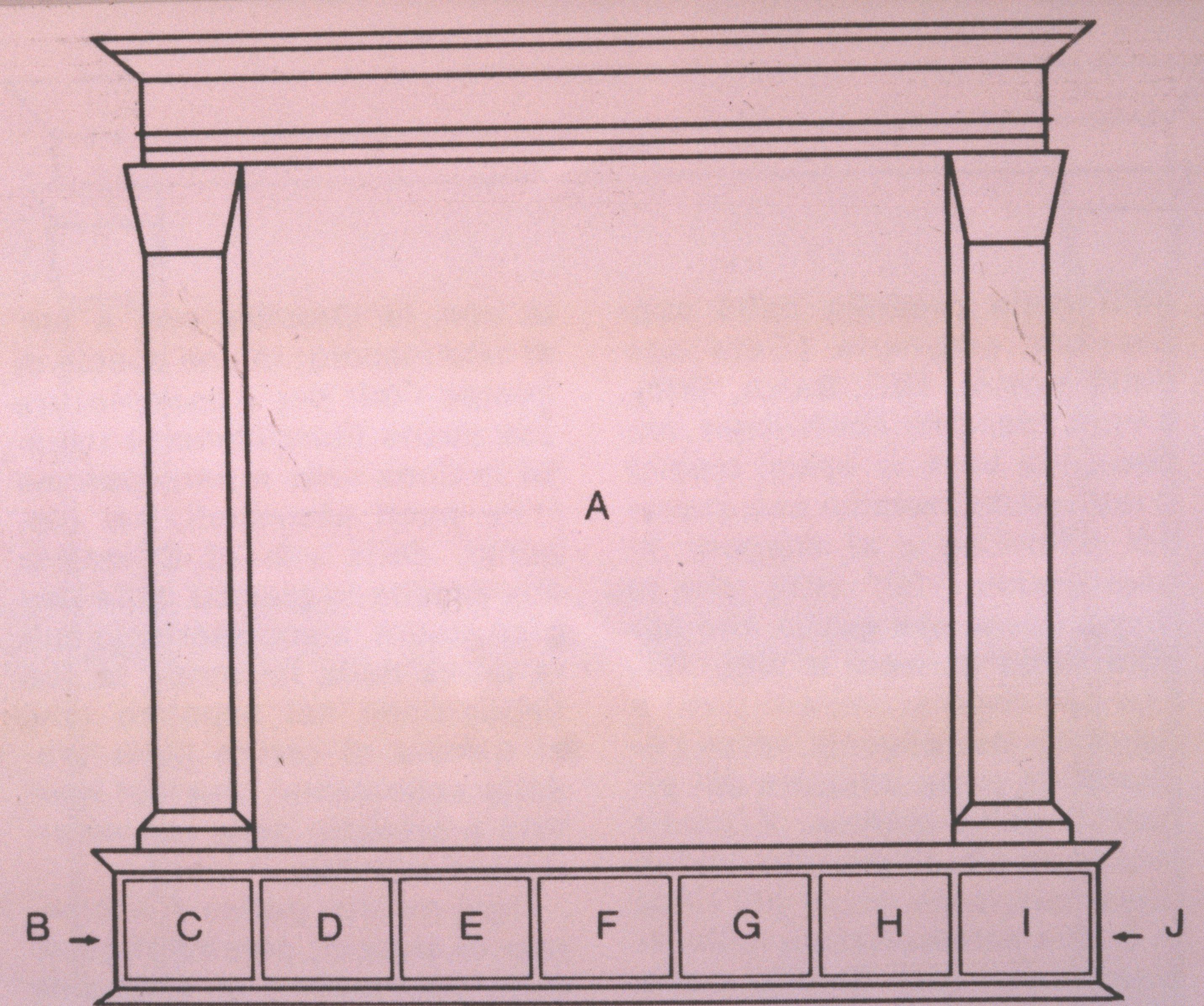

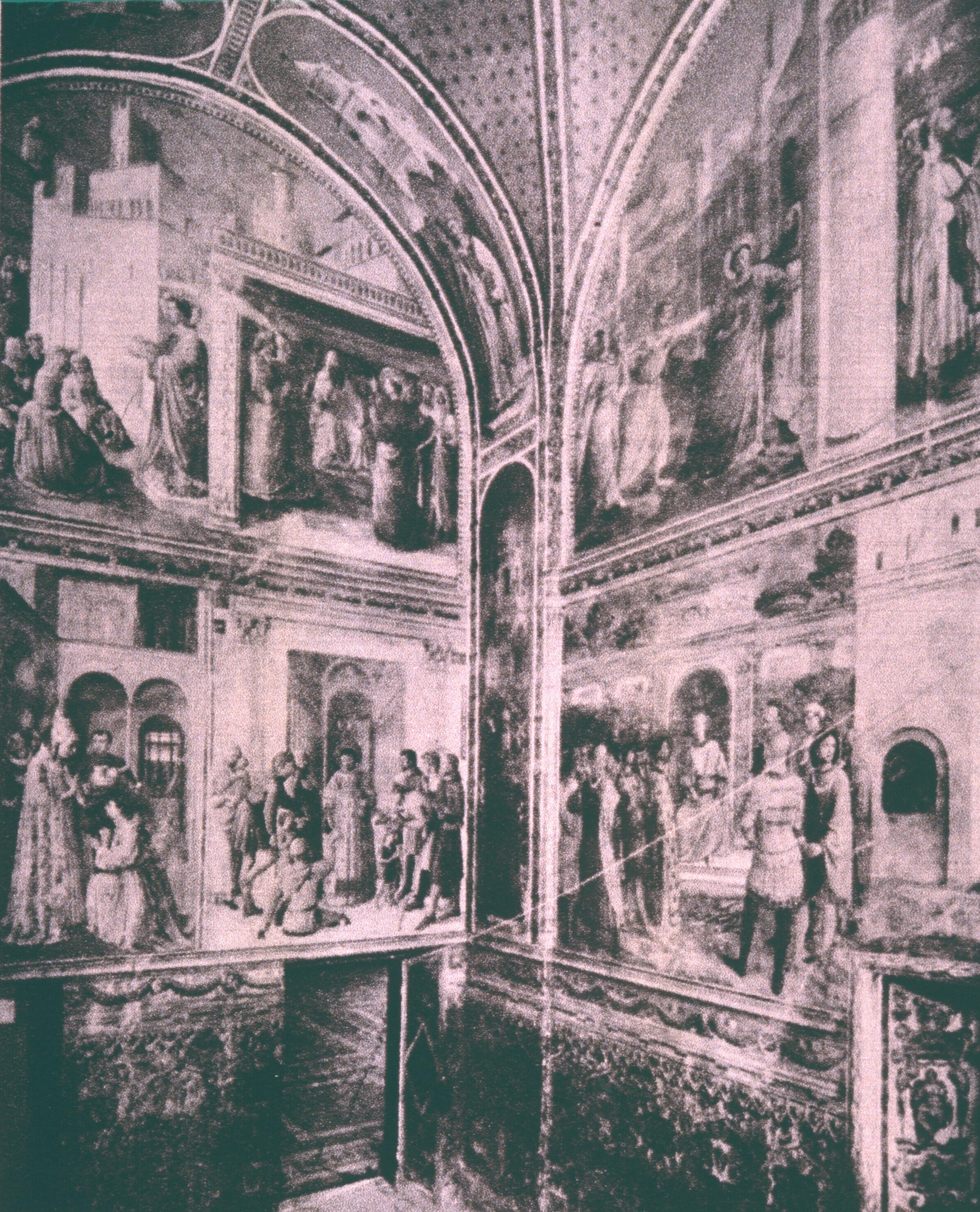

It was Nicholas who first planned a new basilica of St Peter’s and actually began to demolish part of the old; and in the area that he was rebuilding, Nicholas created a private chapel for his own devotions. It is this chapel (which you see in fig. 25), the ‘Niccoline’ Chapel, which Giovanni was commissioned to decorate:

It is quite a small room: five yards across on the wall marked by the letter B on the diagram in fig. 25b, and eight yards on the larger wall, corresponding to the wall marked C in the same diagram.

In what follows, I shall ignore the Prophets who adorn the ceiling vaults and the Doctors of the Church between the windows. Instead, I shall home in on the narrative frescos. These occupy the three lunettes marked A, B and C in the diagram (dealing with St Stephen) and the four rectangular areas marked D, E, F and G in the diagram (which tell the ‘parallel life’ of St Lawrence. Incidentally, the two martyred deacons were often portrayed together, for reasons which need not delay us; but I wonder whether the rediscovery of Plutarch’s Parallel Lives might not have influenced the pope, who was a notable Greek scholar).

With this minimum of context, let us look at the lunette marked A (fig. 26 a) and in particular at the left half of the lunette (fig. 26 b), which illustrates the beginning of the story of Stephen as told in chapter six of the Acts of the Apostles, which is paraphrased in the Golden Legend as follows:

‘Stephen was one of the seven deacons whom the apostles ordained for the sacred ministry. We know that as the number of the disciples increased, the Christians of Gentile origin began to murmur against those who had been Jews, because the widows were being neglected in the daily ministrations. Confronted with these murmurings, the apostles called together the multitude of the disciples, and said: “It is not reasonable that we should leave the word of God, and serve tables. Wherefore, brethren, choose seven men of good reputation, full of the Holy Ghost and wisdom, whom we may appoint over this business. But we will give ourselves continually to prayer, and to the ministry of the word.” This saying was liked by all the multitude. They elected seven men, of whom Stephen was the first; these they set before the apostles, and they praying, imposed hands upon then.’

You will notice how Giovanni has adapted his style to the taste of his patron and the taste of Rome. The figures in the detail in fig. 27 are more ‘massive’ and more like Masaccio than any we have yet seen—even though the haloes stay firmly flat.

I would also like you to pay special attention to the chalice which St Peter is handing to the ‘first deacon’, because it will reappear in the parallel cycle devoted to St Lawrence, and because it is one of those inanimate ‘clues’ to the proportions and treatment of the human figure in these frescos.

The architecture, too (cf. fig. 28), is much more solid and massive than anything we saw in Giovanni’s earlier work. This is not Tuscan-domestic or fairy-tale-romantic, but a very careful and detailed study of classical architecture; and the fall of the light (and the resultant play of the shadows) is even more lovingly observed and rendered.

The wall painted in the centre of the lunette acts as a scene-divider that can be interpreted as belonging to both episodes. Hence Stephen seems to reappear immediately on the outside step of the same church, taking part in a street scene which is one of the loveliest in all Giovanni’s work: notice the blind arcades on the high garden wall, and the exotic, Eastern towers in the narrow street which convey the information that we are in Jerusalem.

The right half of the lunette illustrates just one verse from the same chapter in Acts (6:8), ‘Stephen, full of grace and power, did great wonders and signs among the people’. Giovanni interprets this to mean that, as a deacon, Stephen gave practical help to the widows and children in the foreground, while not forgetting the needy among the men (cf. the detail in fig. 30). Just as Peter had leant forward in the first scene to give him the chalice, so Stephen leans forward to distribute alms to the poor.

The second lunette (marked B in the diagram) also uses architecture to create a pair of locations, one internal in the rather cramped loggia to the right; the other, to the left, external—a medieval street widening into a typical medieval square, topped, however, by exotic towers and battlements to remind us again that we are in the Near East:

Both scenes illustrate Stephen’s prowess in his other, ‘non-deaconly’ role as a preacher. The Golden Legend, in fact, introduces the saint in the entry for his main Feast Day, December 26th, with a typically medieval fanciful etymology, suggesting that Stephanus derives from strenue fans, one who ‘speaks with zeal or energy, concluding: ‘this he showed in his teaching and in his preaching the word of God’.

As you can see in the details in fig. 32, Stephen is ticking off his points on his fingers, while his audience—women, with one attentive child—are seated on the ground, listening raptly (although with a couple of moments of whispered distraction). The men in the background are unconverted Jews, of whom we read in the same chapter of the Acts of the Apostles (6:9–7:2):

‘Then they secretly instigated men, who said, “We have heard him speak blasphemous words against Moses and God.” And they stirred up the people and the elders and the scribes, and they came upon him and seized him and brought him before the council, and set up false witnesses who said, “This man never ceases to speak words against this holy place and the law”…And gazing at him, all who sat in the council saw that his face was like the face of an angel. And the high priest said “Is this so?” And Stephen said: “Brethren and fathers, hear me.”’

The council is, obviously, the scene represented indoors, where we find Fra Giovanni at his most Masaccesque. Stephen’s sermon to the Sanhedrin is a long one (53 verses of Acts Chapter Seven), and it is one of the earliest and most important statements about the relationship between the Old (Jewish) Law and the New. As Stephen’s forceful gesture with his right hand suggests (cf. fig. 33), it is not in the least conciliatory in tone, ending with the words “You stiff-necked people! Your hearts and ears are still uncircumcised.”

The immediate consequences of Stephen’s words are illuminated in the third lunette (fig. 34), where the most beautiful and magical of all Giovanni’s long, turreted walls starts in the centre as a scene divider, and curves away to the left, losing height to reveal the chalky hills with a towered fort on the summit.

It is the wall of the city of Jerusalem, and its prominence is justified by the text of the Acts of the Apostles:

‘Now when they heard these things they were enraged, and they ground their teeth against him…They cried out with a loud voice and rushed together upon him. Then they cast him out of the city and stoned him. And as they were stoning Stephen, he prayed, “Lord Jesus, receive my spirit.” And he knelt down and cried with a loud voice, “Lord, do not hold this sin against them.” And when he had said this, he fell asleep.’

The casting out and the stoning are illustrated to perfection and no further commentary is required.

A glance back at the diagram of the three walls (fig. 25b) will remind you that we have seen Stephen ordained as deacon and acting as deacon in giving alms to the poor (A); preaching ‘strenuously’ to the widows and the Council (B); and ‘bearing witness’ to his beliefs as the first ‘martyr’ of the Christian faith (C). You should keep these scenes in mind as we come to the lower register, which deals with his ‘grave-mate’, fellow deacon and martyr, St Lawrence.

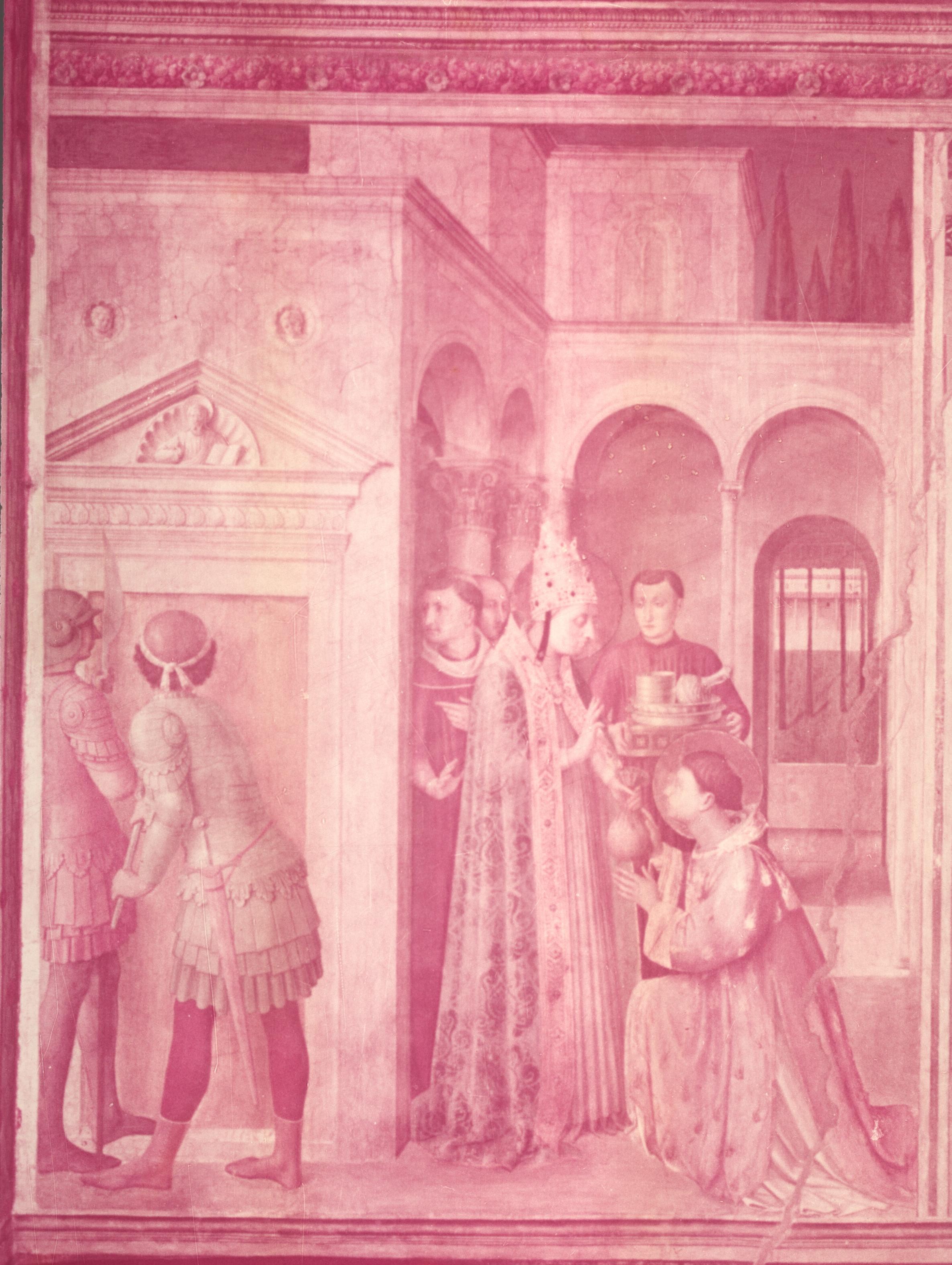

The first scene (letter D in the diagram in fig. 25), is placed between two real windows, as you can see in the above black and white image of the whole wall in fig. 36. It lies immediately below the scene of Stephen’s ordination by Peter, and the fresco (fig. 36) measures ten feet high by seven and a half feet wide:

The story takes place in the middle of the third century, and it can be told in one line: ‘Lawrence, a native of Spain, was brought to Rome by Saint Sixtus, who ordained him his archdeacon.’

According to the Golden Legend, the Emperor at this point was called Philip, and he was the first emperor to embrace Christianity. Alas, he was the victim of a coup d’état by his general Decius, who had just waged a successful war in Gaul, and who murdered Philip in his camp at Verona when the emperor came to meet and congratulate him.

Philip’s son—also a Christian, also called Philip—heard that his father had been murdered and that Decius was advancing on Rome with his troops. ‘He was filled with fear at these tidings, and handed over his father’s treasure and his own to Saint Sixtus and Saint Lawrence, in order that they might distribute it to the poor, in the even that he was done to death by Decius.’ Decius seized power, slaughtered many Christians—including young Philip—and then ‘made inquiry after his predecessor’s treasure’, sending first for Pope Sixtus.

Inside the courtyard, Pope Sixtus—again wearing his tiara, and again with the features of Nicholas V (cf. fig. 40b)—entrusts to Lawrence the treasures of the Church (represented by the vessels) and the treasures of the Emperor (represented by the money bag), so that the deacon may distribute them to the poor, and thereby save them from the hands of the usurper.

[FIXME: the rear of a sheet of the typescript has a cut and pasted extract from a text describing what is apparently this scene; not clear whether this should be incorporated here]

The scene on the right (fig. 41) shows Lawrence distributing the money. He stands in the centre of an imposing classical door, framed by pilasters, which reveals a long, narrow nave with classical columns receding to an apse, which acts as a frame to the saint’s head and halo. (Some critics believe that the building is inspired by Nicholas’s 1450 plan for rebuilding St Peter’s.) Lawrence is dressed in a splendidly decorated dalmatic (the garment prescribed for deacons) while he counts out coins from the money bag into the hands of the cripple on the ground, in just the same way as Stephen had distributed alms to the poor in the corresponding scene in the fresco immediately above (cf. fig. 30).

The recipients of the charity are as important in the story as the saint and the money, because when Lawrence himself was arrested and the emperor demanded to know where the treasure of the Church was, he pointed to the poor and said ‘these are the treasures of the Church’. (The two details in fig. 42 show that Fra Giovanni is rather conventional and pretty in his treatment of the young mother and child, but he rises to the occasion as he conveys the blindness and dignity of the man with a cane and vacant stare.)

There is an architectural rhyme between the frame of this scene and the one immediately above (Stephen before the Sanhedrin in fig. 25); and there may also be a rhyme between the figures of Stephen before the high priest and of Lawrence being examined by the emperor Decius, on the left in the third fresco (fig. 43) of the lower cycle:

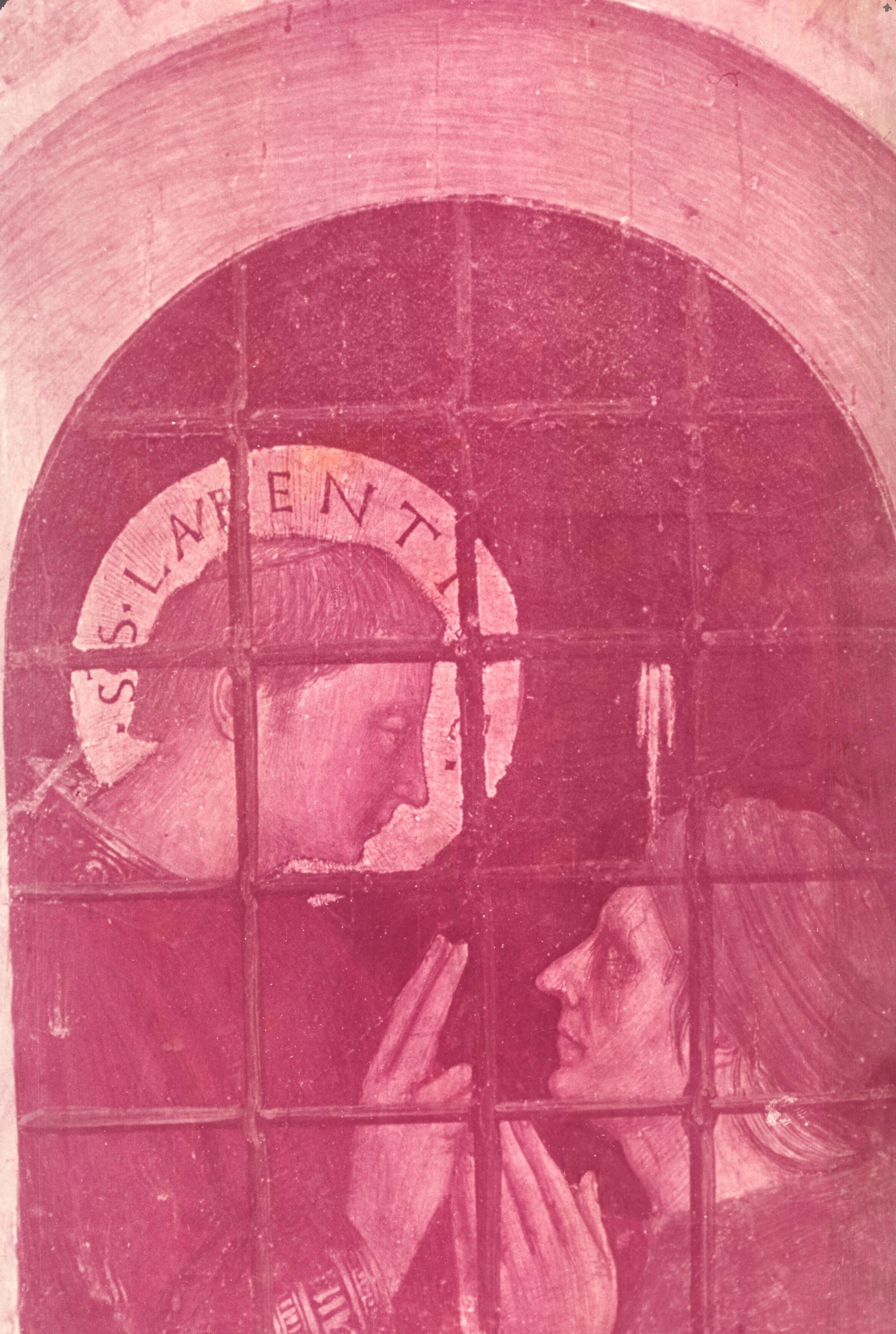

And it would take disproportionately long to tell the story behind the little scene in the prison window (cf. detail in fig. 45), where Lawrence, clearly labelled, is converting his jailer Hippolytus (whose face provides a lovely example of confident painting on fresh plaster. Incidentally, Hippolytus was also to suffer martrydom and his Feast was observed on August 14th, just four days after that of Lawrence).

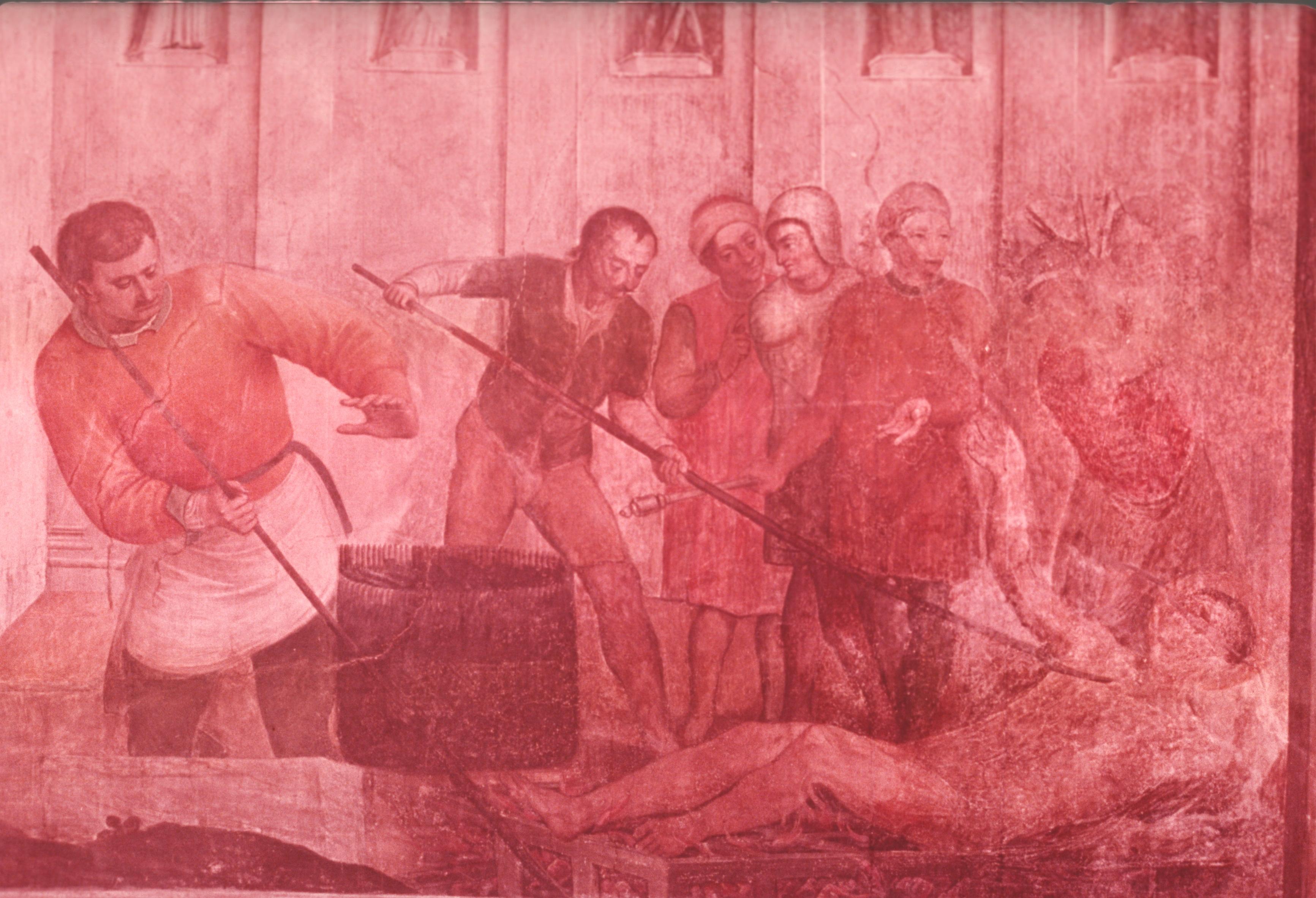

Instead, I call your attention to the scene on the right of the same fresco (fig. 46), which is placed above the real door in the chapel and below the painting of the stoning of Stephen. The final act of the drama is told as follows:

‘Every sort of torture was prepared for Laurence, and Decius said to him: “Sacrifice to the gods’ (you see them in the niches) ‘or you shall pass the night in torments!” And Lawrence answered: “My night has no darkness: all things shine with light!” “Let an iron bed be brought,” said Decius, “that this obstinate fellow may take his rest thereon!” Then the executioners stripped him and stretched him on a gridiron, pressing him down with iron forks; and they heaped burning coals beneath. And Lawrence said: “Know, wretched man, that these coals bring refreshment to me, and eternal punishment to you! Behold, wretch, you have cooked one side well! Turn the other, and eat!” And giving thanks, he said: “I thank Thee, O Lord, that I have been made worthy to enter Thy portals!” And so saying, he breathed his last.

The body and gesture of the executioner who seeks to shield his face from the heat of the coals offer a good, final example of Giovanni’s skill in fresco towards the end of his life, but since the body of the saint has been further tormented by damp, perhaps this is a good place for me to ‘breathe my last’ in this lecture.

[FIXME: As well as this typescript edited above, there is in the envelope a bundle of various pages and off-cuts entitled ‘Re-worked 1989’ which we may—or may not—wish to do something with]

FIXME: Also search for “00”

![Figure 5: (O_An_5) [FIXME: caption needed]](media/image5.jpeg)

![Figure 6: (O_An_6) [FIXME: detail from fig. 5]](media/image6.jpeg)