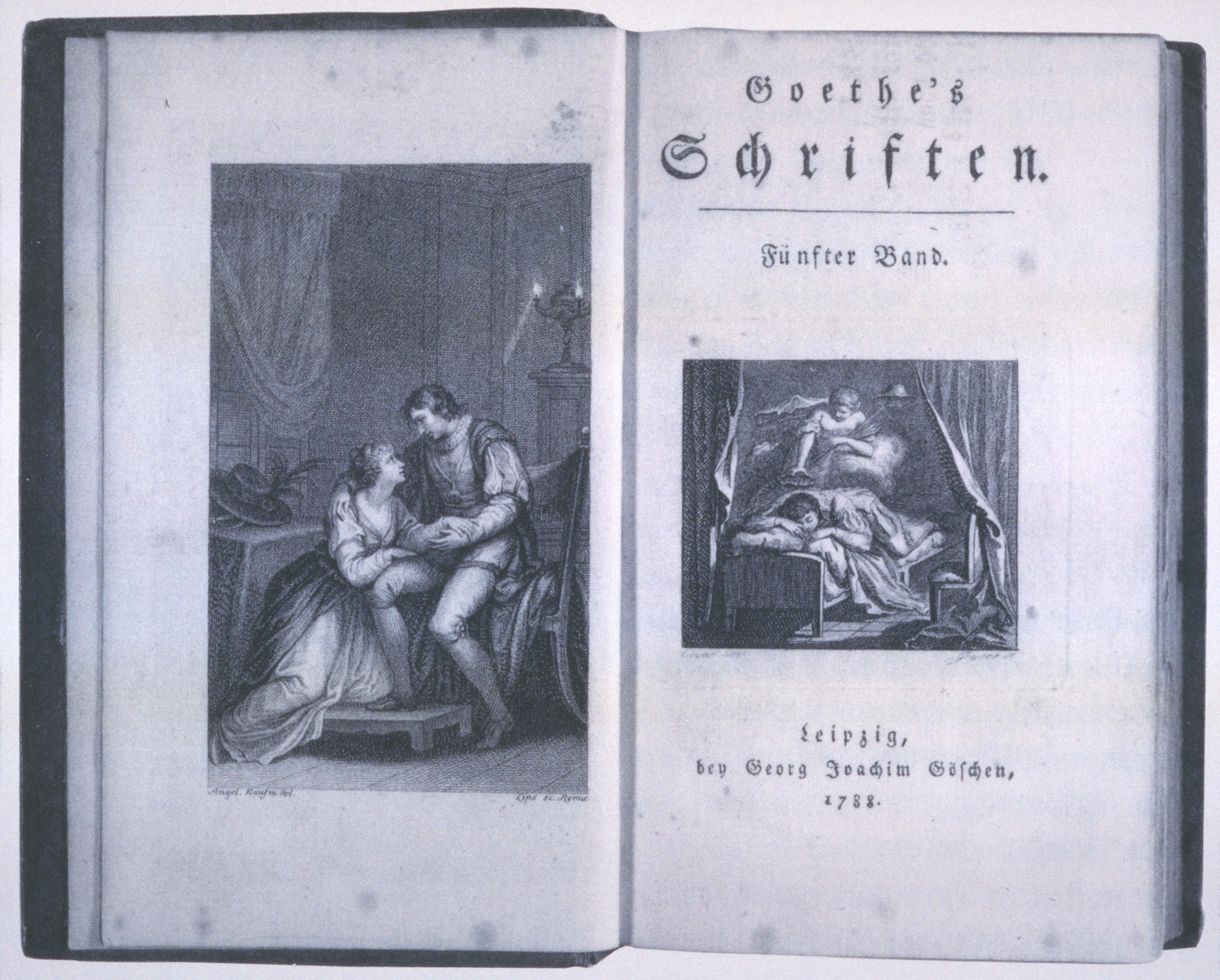

Despite its complicated title, this lecture aims to do something very simple. It will offer not much more than an introduction to just one book by Goethe, his Italian Journey, which you can read in a fluent translation published by Penguin. I hope it will make you want to go and buy the book immediately.

The first third was published in 1816, the year after Waterloo, and the second in the following year.

Hence these two parts appeared more or less at the same time as a collection of Goethe’s poems inspired by his growing interest in Oriental culture, and especially, in the poets of medieval Persia. Since you are likely to know Fitzgerald’s Omar Khayam, you will readily imagine the ‘feel’ of these poems, in which Goethe adopts the persona of the Persian poet Hatem, and borrows proper names, imagery, attitudes and themes from his models, while expressing his own thoughts and feelings and his own very western sensibility.

To bring out this paradox, Goethe called his volume by the very strange title: West-österlicher Dívan—where you can ignore the various meanings of the Persian word ‘Divan’, but register that ‘West-österlich’ is a deliberate oxymoron, since ‘East is East, and West is West and ne’er the twain shall meet’. A wind may certainly be South-easterly, or South-westerly, but it cannot be West-easterly.

But Goethe was a poet, and, as such, capable of miracles. The Greek sculptor (he tells us in the poem Mag der Grieche)—the Western artist, male, the demiurge—imposes his will on his subject matter. He models his figures out of solid clay, and his pleasure is intensified when he can recognise himself in his ‘offspring’. But Hatem, the Persian poet—the Eastern artist, feminine, intuitive—is seemingly content to dip his hand into the Euphrates, just letting himself be carried, this way and that, by the ‘fluid element’. Such is the contrast between West and East. But now for the resolution. If Goethe were to ‘quench’ his burning passion in the stream, a song would ring out, like the scream of red-hot metal hitting cold water. Or, switching the metaphor instantly (as one can do in the ‘fluid’ medium of words), if his ‘poet’s hand were to scoop water out of the Euphrates’, it would stiffen, solidify, and take on the form of a ball in his cupped hand, held in place by metre and rhyme.

Mag der Grieche seinen Ton

Zu Gestalten drücken,

An der eignen Hände Sohn

Steigern sein Entzücken.

Aber uns ist wonnereich

In den Euphrat greifen,

Und im flüßgen Element

Hin und wider schweifen.

Löscht ich so der Seele Brand,

Lied, es wird erschallen;

Schöpft des Dichters reine Hand

Wasser wird sich ballen.

West-österlicher Divan, Buch des Sängers (I), Lied und Gebilde.

Let the Greek press

his clay into figures

heightening his joy

in the child of his own hands.

But our pleasure is

to reach out into the Euphrates,

and to glide to and fro

in the fluid element.

Were I so to quench my soul’s fire,

song, it would ring out;

water will round to a ball, if it is

drawn by the pure hand of a poet.

Now, the decades from 1790 to 1820 were those in which German philosophers were feeling their way to a dialectical model to account for change in the natural world and in human history. The thesis, X, will clash with its antithesis, Y; but the result is not the defeat of one by the other, but a higher synthesis: X + Y = Z. From about 1800, Goethe himself was preoccupied by the related notions of polarity (‘Polarität’) and intensification (‘Steigerung’); and this tiny poem, with its contrasts of Greece and Mesopotamia, is itself an example of that process of ‘Steigerung’. It is neither Western nor Eastern, but something ‘West-easterly’, a fusion of the two elements in a new and higher, ‘intensified’, compound.

I am sure you have understood the thrust of my argument before I state it explicitly. If something cannot be ‘West-easterly’, it cannot be ‘North-southerly’ either—unless it has been ‘fired’ in the creative imagination of a poet and allowed to ‘harden and ball itself’ in poetic form. I shall be suggesting that Goethe published Die Italienische Reise in an effort to explain to his readers what had happened to his personality and his art, when (to use a metaphor of my own) he ‘grafted’ the ‘bud’ of Mediterranean culture, the ‘scion’ of the South, on to his wild but vigorous Northern ‘stock’. Of course, this process was infinitely more complicated and nuanced than Goethe’s late and rather superficial attempt to assimilate the Orient, but the simpler paradigm can help us to see the nature of the enterprise. Goethe wanted to have ‘the whole world in his hands’.

Gottes ist der Orient!

Gottes ist der Okzident!

Nord- und südliches Gelände

Ruht im Frieden seiner Hände.

West-österlicher Divan, Buch des Sängers (I), Talismane.

The East is God’s,

the West is God’s!

Regions of the North and South

rest in the peace of his hands.

*****

Before I begin to offer any kind of interpretation of the book, I thought it would be a good idea to remind you of the raw facts of the journey itself, looking at the landscape and the buildings he saw, as far as possible with eighteenth-century eyes.

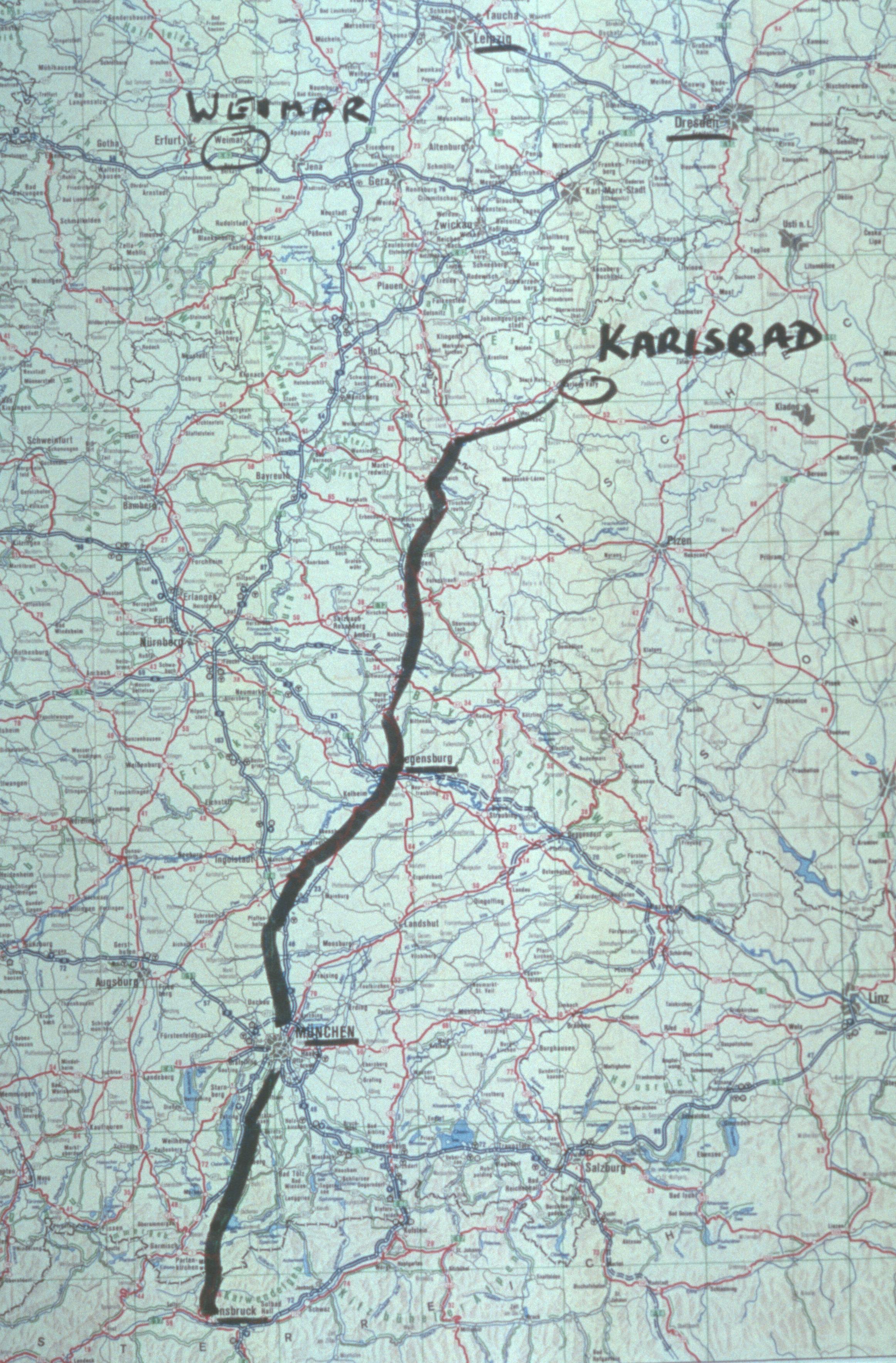

His hired carriage took him via Munich and Innsbruck, over the Brenner (cf. fig. 4), down past Lake Garda to Verona and Vicenza, and then along the river to Padua and Venice—all this by the end of September. In Venice he had his first ever sight of the sea, and was of course stunned by the buildings on the lagoon close to St Mark’s: the fairy-tale Doge’s palace (seen in fig. 5a, looking East along the waterfront in a magical view by Carlevarijs painted early in the eighteenth century); and (from the same point in fig. 5b, looking in the opposite direction) the classicising library and column on the Piazzetta.

He explored Venice with great zeal for a fortnight, absorbing the inner-city charm of spaces like the Campo San Gallo, just behind St Mark’s (painted by Marieschi in about 1750, fig. 6a), as well as the great square used for all public processions, the square of St Mark’s (painted in fig. 6b by Bernardo Bellotto):

He passed over the Apennines to Florence, for just a few hours, then proceeded South-east up the Arno valley, before swinging south down the valley of the Tiber, until on the first of November he saw what he had been dying to see all the time: Rome—the capital of the world, ‘die Hauptstadt der Welt’, the eternal city—shown in its setting in fig. 8 by Vanvitelli, from an unusual viewing point behind St Peter’s.

He took in Castel Sant’Angelo on the Tiber (fig. 10a), with the cupola of St Peter’s behind; Bernini’s gigantic colonnade in front of St Peter’s (fig. 10c is a modest painting by a follower of Van Vitelli); and the steps up to the Renaissance palaces on the Capitol, with the even steeper stairs going up to the medieval church of Aracaeli (depicted in fig. 10b by Bernardo Bellotto and his son).

At the top of his agenda, though, were the monuments of classical Rome: the Colosseum and Arch of Constantine (Vanvitelli again in fig. 10a), or, from the Arch, the view along the Forum to the West side of Aracaeli (Panini, in fig. 10b).

Towards the end of February, he set out for Naples (cf. fig. 12: a shorter journey which took only three days) and was bowled over by the sheer beauty of its position on the bay (in fig. 13, we see the city from Portici, in fact from the windows of the villa of Sir William Hamilton, which Goethe visited more than once.

And not just grandeur either, but menace and a sense of the precariousness of all things human. The cities of Pompei and Herculaneum, buried by the eruption of Vesuvius in the first century, were being excavated in these very years. In fig. 16a, I show you Pompei as painted by Goethe’s friend, the artist Philipp Hackert; and it is relevant to know that it was news of the volcano beginning to erupt again which caused Goethe to set out for Naples when he did.

It had about 500,000 inhabitants, three times as many as Rome; and Goethe was delighted by the vitality of Neapolitan life, which characteristically found expression in festivals, like the one in progress in fig. 18.

After a month in Naples, at the end of March he set out on a new and somewhat more risky journey, which was not something he had been committed to from the outset.

He made friends with a young German painter called Christopher Kniep (cf. fig. 19), just a year older than himself, and he employed him as companion and ‘photographer’, as it were, for the coming journey. Together they took passage on a corvette to Sicily, and four days later, on April 4th, they landed in Palermo, another beautiful city lying on a bay, as you see in the view by Antoniani in fig. 20:

Then, instead of going to Syracuse, they made their way right through the heart of Sicily to Catania, from which city they went up, via Taormina, to Messina, arriving only four years after the huge earthquake of 1783 had devastated the city (shown in fig. 24, in a very stiff and amateurish view, well before the disaster).

Among the deepest impressions left by Sicily were the Greek remains—the beautiful amphitheatre at Taormina, the line of temples on the shore at Agrigento, and, before these, the solitary temple of Segesta (the three images in fig. 25 show you the temple, crudely engraved, in its setting, in the late 1770s; then romanticised in close up by Goethe’s friend Hackert on an earlier visit in 1777; and in a recent photograph.

From Messina, they returned to the quayside at Naples (fig. 26); and after that, it was all consolidation. Goethe spent another three weeks in the city, once again enjoying the life on the streets; and he made an excursion out to the temples at Paestum (shown in fig. 27, in a watercolour by his friend Kniep), although he later pretended (as Nicholas Boyle proved in a very amusing article) that he had been there before he went to Sicily.

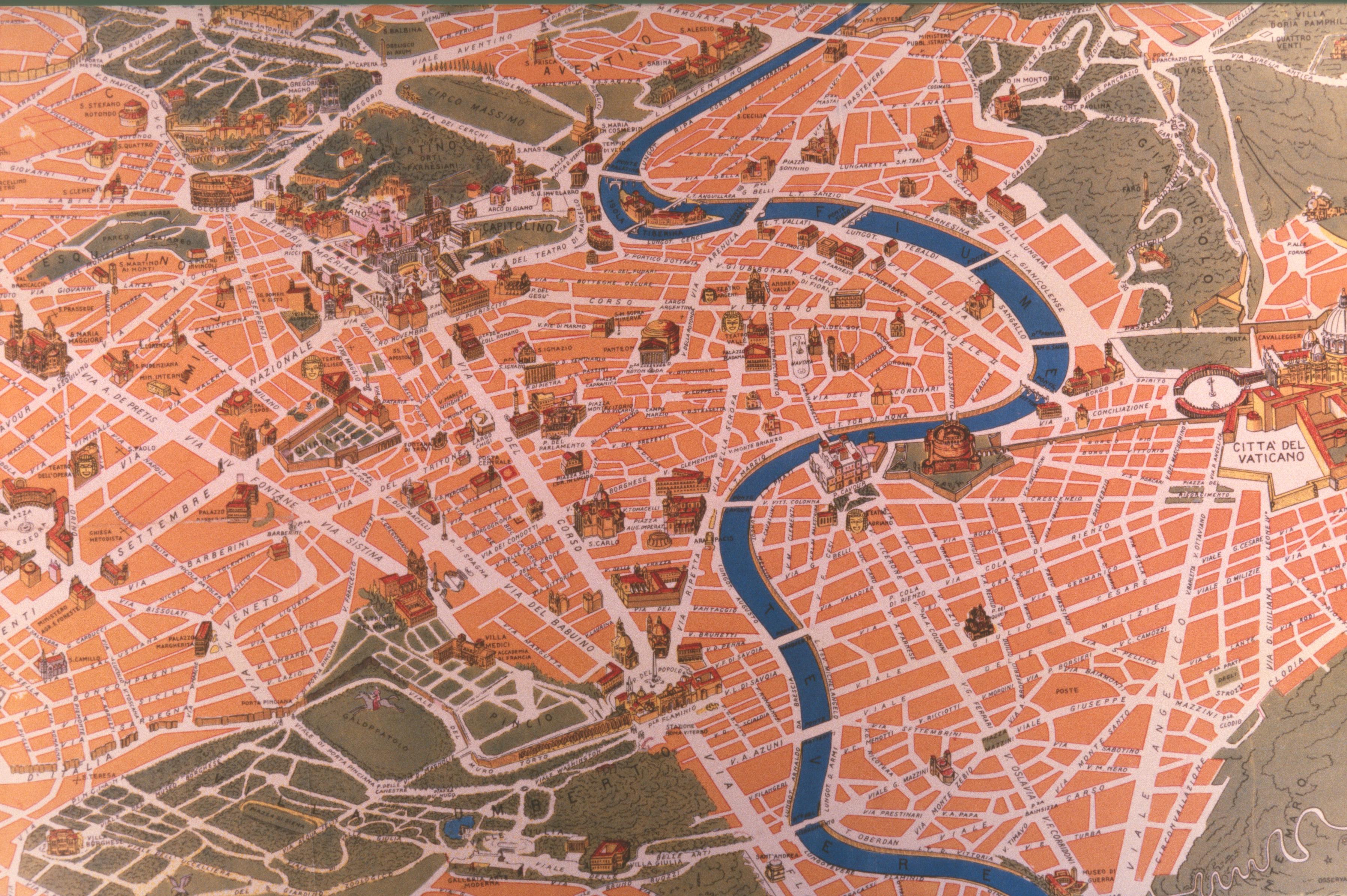

Then, on the June 8th, it was time to return to Rome, where he settled down again in the same house overlooking the long, narrow Corso, which you can see clearly in the modern tourist map in fig. 28 (the map is suitably ‘North-southerly’, in the sense that South is at the top where we expect North to be).

This is the vast space that greeted new arrivals from the North, with its obelisk and the charming twin churches on either side of the Corso—Goethe’s lodgings being only about two hundred yards down the road. Although he had originally planned to return to Weimar shortly afterwards, in the event Goethe stayed in this area with his artist friends for the best part of a year, and was obviously sublimely happy to be one of the lads again.

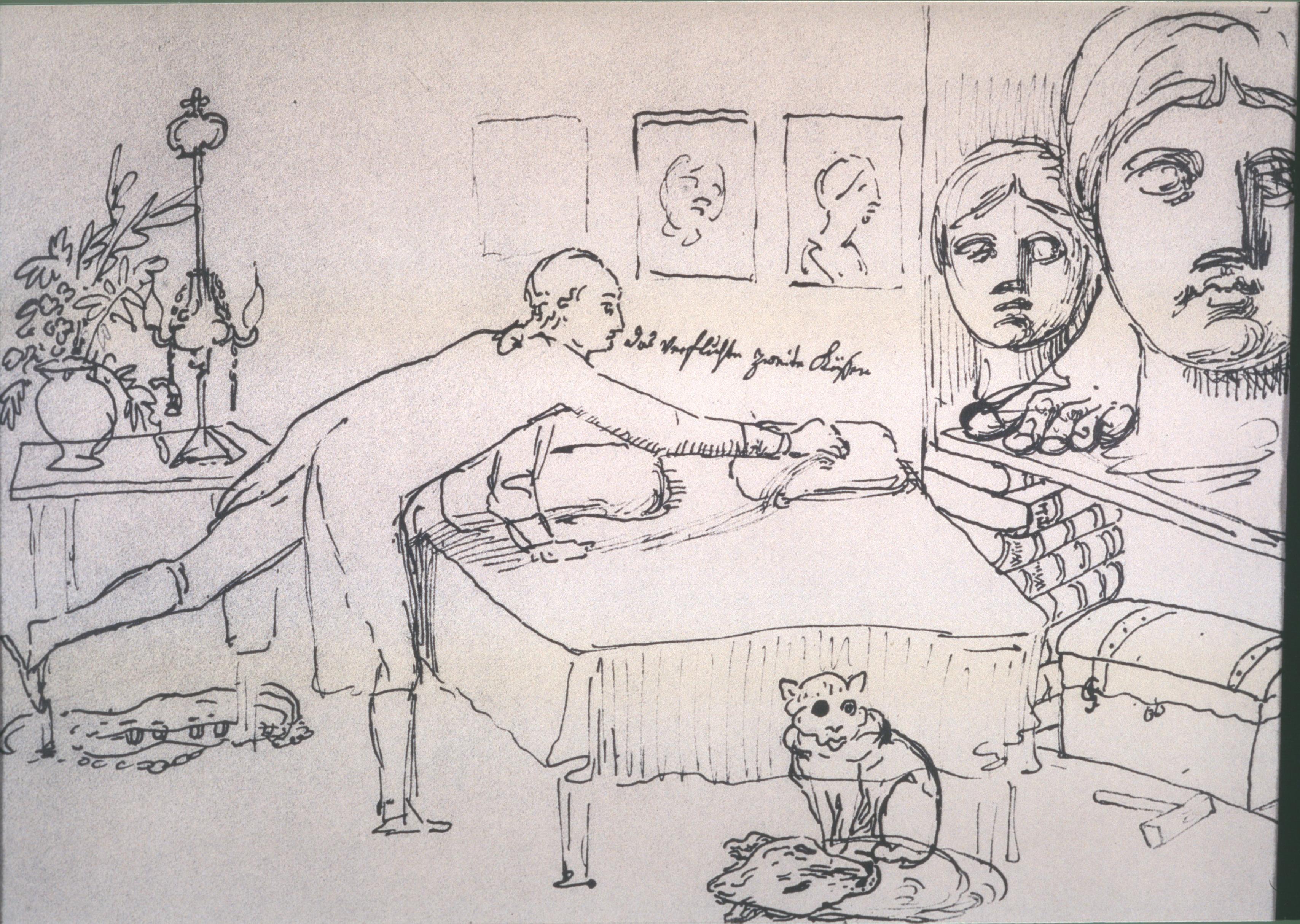

In fig. 31, Goethe is in his bed-sitting room, making a crack about ‘das verfluchte zweite Kissen’, that ‘bloody second pillow’—the problem being that while he had a double bed, he had no partner for that second pillow. The cat in the foreground is the one who, to the amazement of his landlady, had seemed to worship the giant bust of Juno (on the right; cf. fig. 46 below), which was Goethe’s most treasured acquisition (whereas he himself realised that the cat was attracted by the smell of the animal fat used in the mould of the plaster-cast).

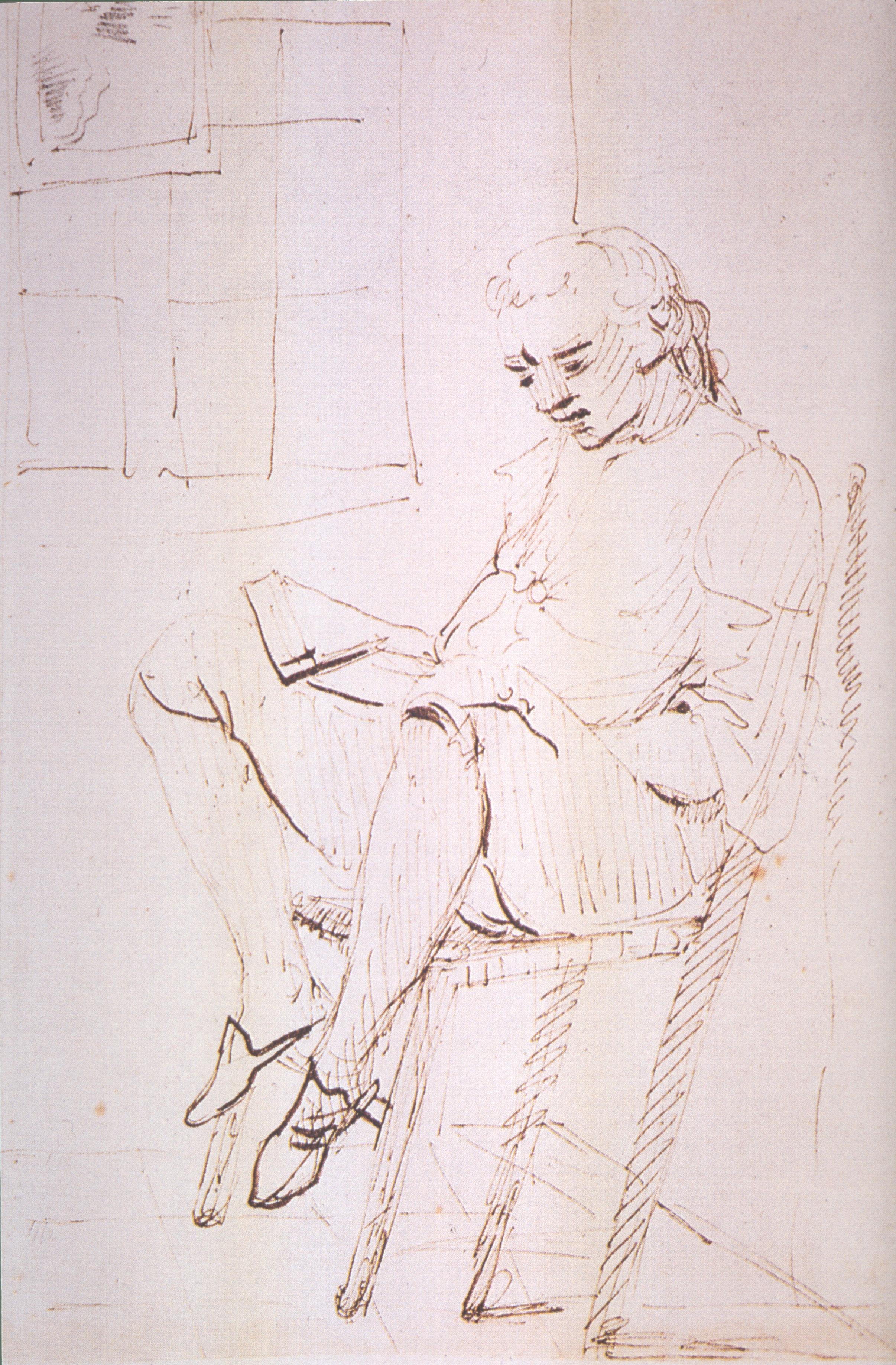

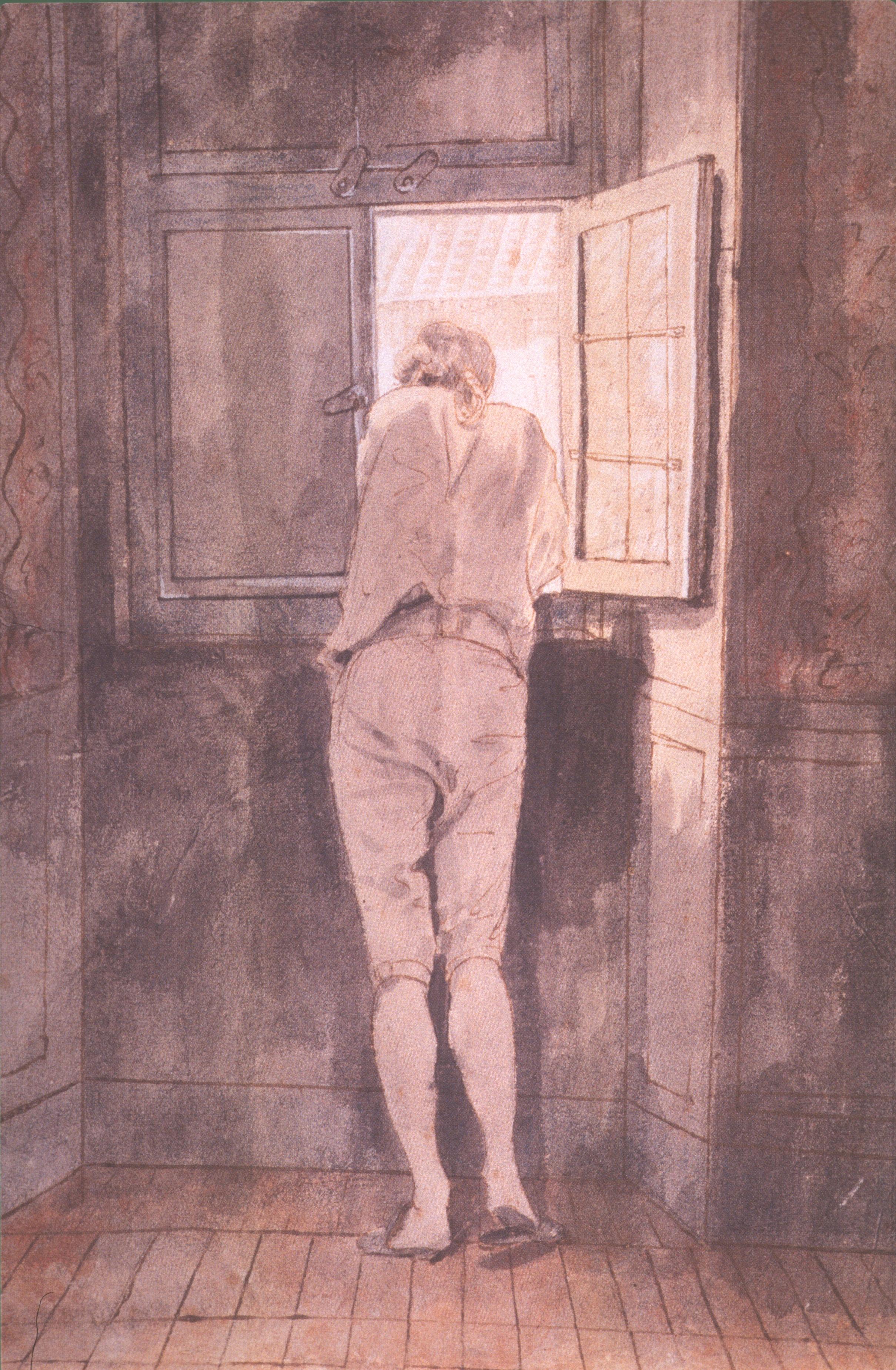

In his lodgings he could just sit and read a book in his shirt-sleeves, tipping his chair back like a typical teenager (as you see him in fig. 32): or he could stand for ages at the window, dressed exactly as he would have been as a student fifteen years earlier, looking down onto the Corso below him, and observing life on the streets.

Of course, you have to be told that it is Goethe’s back you are looking at, but for me this is the most expressive, and most attractive of all the images of Goethe I have ever seen.

All holidays have to come to an end, though—in May 1788 he left Rome for ever, and by early July he was back in Weimar. He had been away for the best part of two years—22 months—spending a good five months of that time on the road or on a boat; but he had had those longer stays in Venice and in Naples, and he had lived in Rome for fifteen months altogether.

*****

As they say after a news bulletin in Germany: ‘So weit die Nachrichten’. Our next job is to try and get behind the facts, or at least to set them in some sort of context. The first thing to remind you is that, in the way I have told the story so far, there is absolutely nothing remarkable in it. Goethe was doing the ‘Grand Tour’, an undertaking by then so commonplace as to provoke Dr Johnson’s famous put-down: ‘Sir, a man who has not been in Italy is conscious of an inferiority, from his not having seen what it is expected a man should see’.

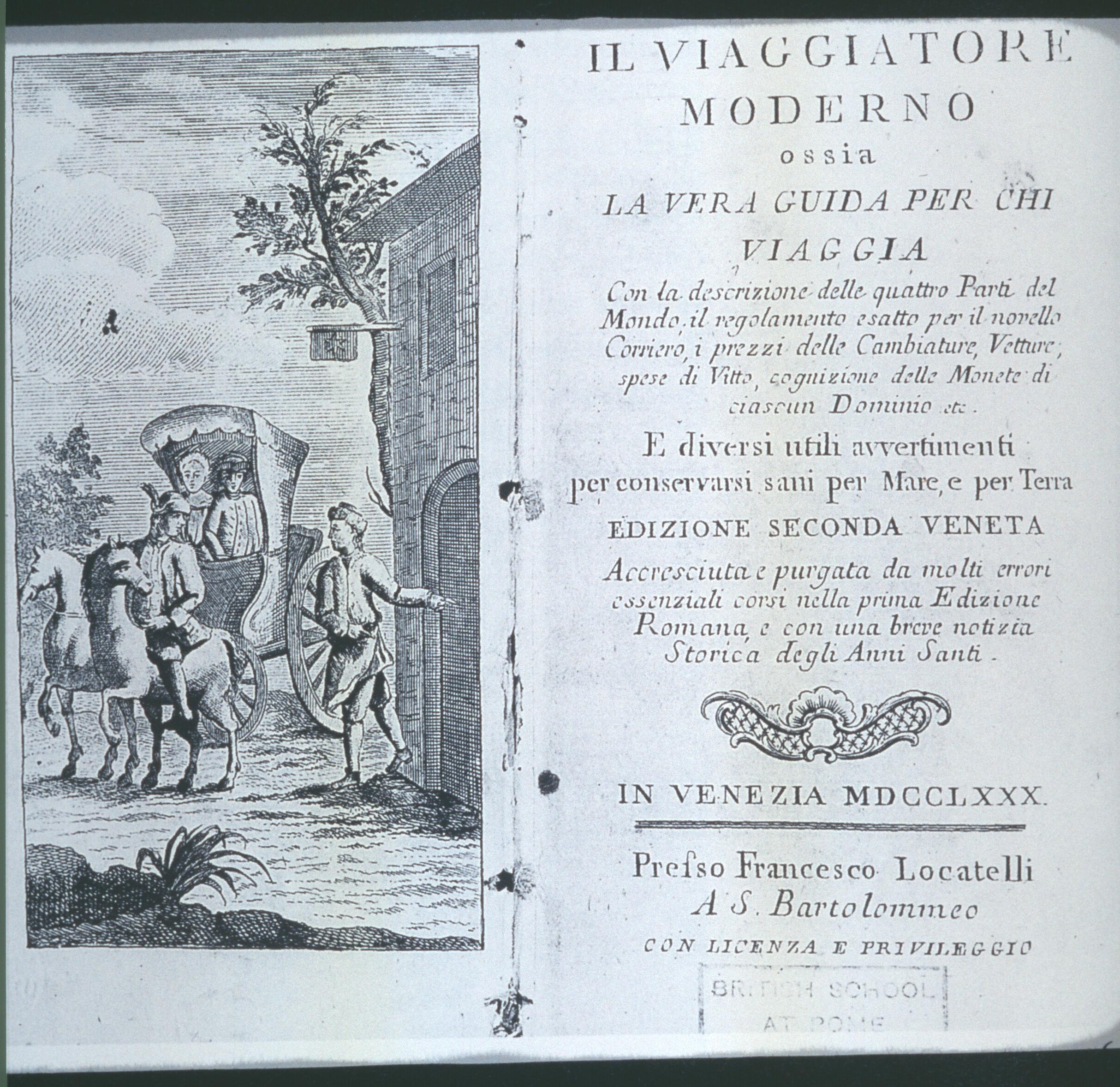

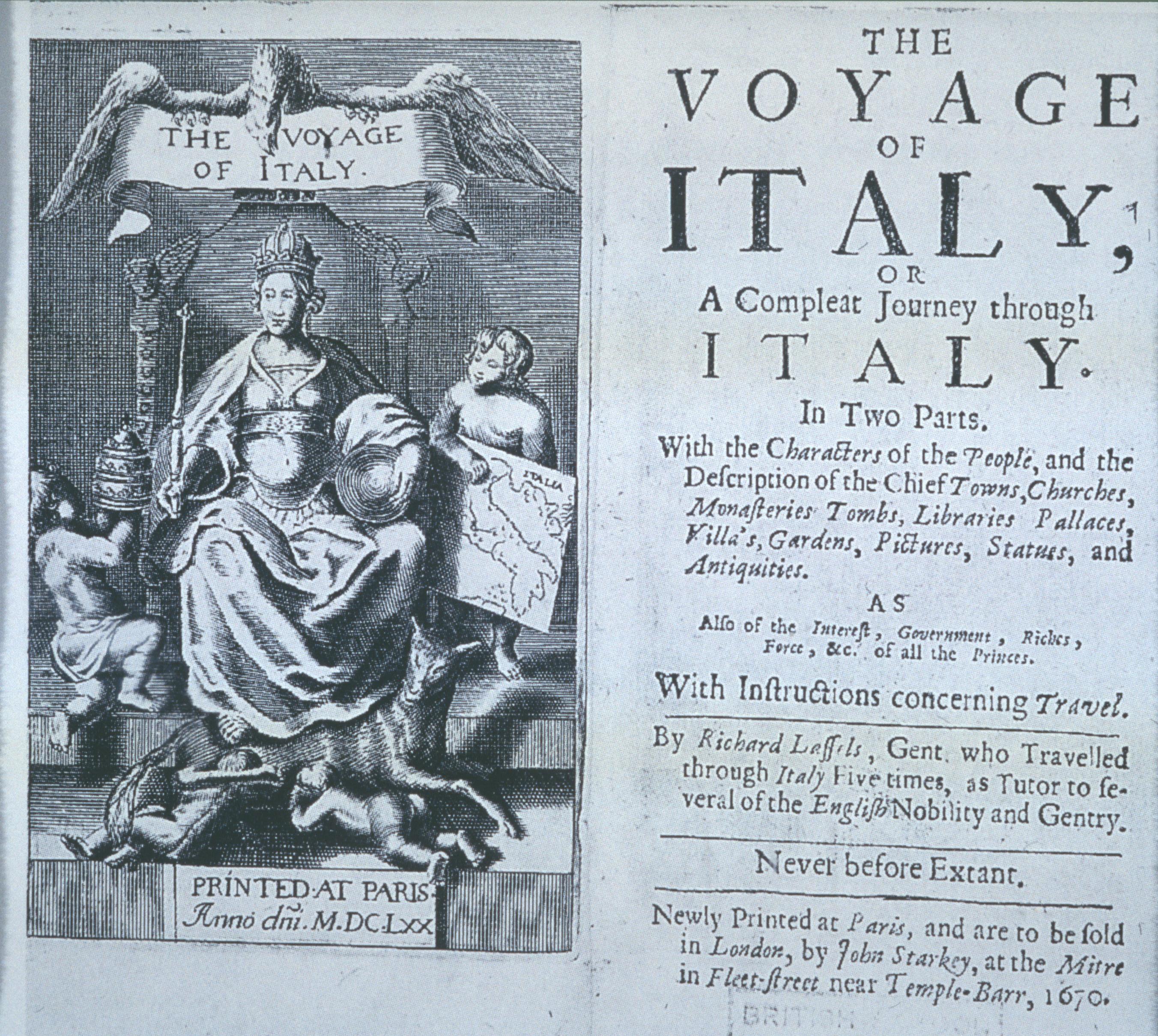

He went armed with a practical guide book, telling him exactly what to expect at in every place and at every level. I choose the title page of the one in fig. 34, dated 1780, instead of his own Volkmann, because of its little sketch of a carriage at an inn; but such books had been in existence for a century, and the English-language ancestor in fig. 35 dates back as far as 1670:

But Goethe saw these buildings and hills rather differently, in a gentle, poetic haze, with happy contadini in the foreground—because his eyes had been prepared, just like those of other visitors, by landscapes such as the first one in fig. 37, painted around 1700, with its circular fort, its villa, river with boats, and spreading trees, all of which elements go back to the enchanted vision of the Roman Campagna created by Claude in the 1640s (fig. 37b).

As regards the tourist attractions listed in the guide-books (the title page of the 1670 guide already specified churches, monasteries, tombs, palaces, villas, gardens, pictures, statues and antiquities), Goethe had assiduously prepared himself for what he ought to enjoy by his earlier study of the aesthetic of Winckelmann, who had lived in Rome for many years and finally met a tourist’s death in a street murder in Trieste in 1768, the year of the portrait of him in fig. 38.

This was an ancient, pre-Christian ideal, which had been smothered (so the neo-classicists thought) in the Dark Ages and in the Gothic North, but which, in sixteenth-century Italy (so the neo-classicists thought), had once again found perfect expression in the buildings of Palladio and the paintings of Raphael, whose own vision of classical culture you see below in the School of Athens:

This pure ideal was thought to have been lost again in the various movements we now call Mannerist, Baroque and Rococo; and Goethe’s conscious purpose was to see with his own eyes works of art which he had been taught how to admire by Winckelmann, but which he had known up till then only in plaster casts or engravings.

In his first few days in Italy, in Vicenza, he was bowled over by the buildings of Palladio—notably, the centrally planned villa, just out of town, known as La Rotonda (fig. 41). He immediately bought himself a copy of Palladio’s Four Books of Architecture, where he could study the plan and details of this and many other buildings, admiring the deliberate marriage of the beautiful and the useful, of contemporary needs and classical proportion. The result of his study was that, when he got to Venice, he looked with deeper insight and pleasure at the Palladian churches there, preferring above the others, the Church of the Redeemer (fig. 42).

His admiration for Palladio was, of course, shared by hundreds of wealthy English aristocrats, who commissioned villas like the Rotonda to stand in parks landscaped to look like paintings by Claude; but Goethe studied Palladio more diligently than they did, trying to master the principles and details of classical architecture, and some of his own analytical descriptions of ancient buildings—for example, the façade of the tiny temple of Minerva in Assisi (cf. fig. 43)—are remarkably well informed.

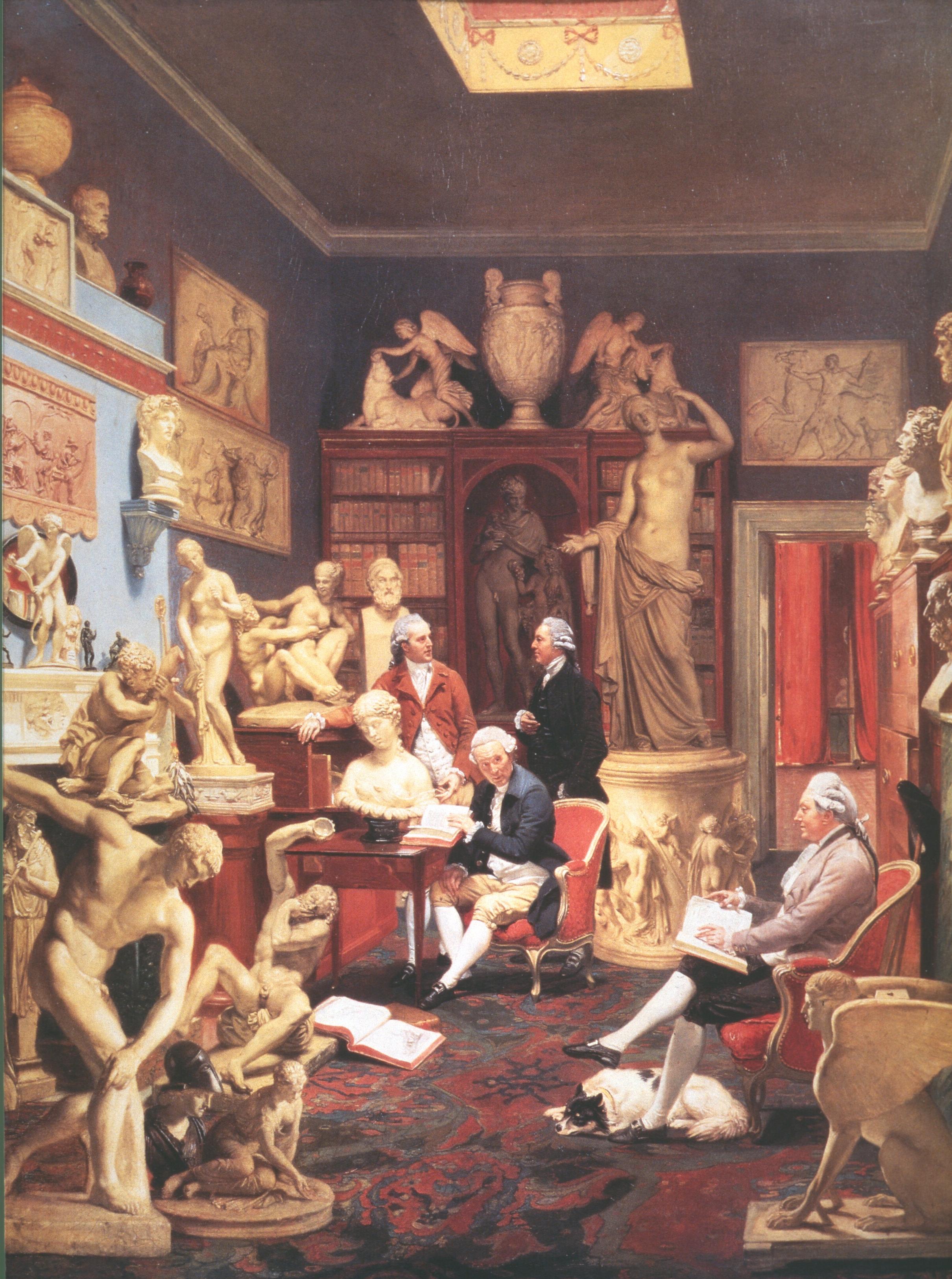

He did not have the kind of money to go to a studio like the one you see in fig. 44 (painted by Panini in 1755), where you could acquire paintings of every Roman monument that mattered; and he could not even begin to rival the collection of plastercasts assembled by Charles Townley, which you see in his London library in the year 1783 (fig. 45):

But it is typical of Goethe that his favourite souvenir was the plaster cast you saw in the drawing in fig. 31, namely, the giant head of the so-called Juno Ludovisi (fig. 46 shows the original by moonlight), which was in his view the epitome of classical art—and just the right size to go in your valise!

However, he did not do the obvious thing and go to Pompeo Batoni (as the American in fig. 47 did, when he was in Rome in 1783). Instead, he sat, formally this time, for his friend Tischbein, who put everything he possibly could into the background to make sure we know it is a record of the Grand Tour—the background offers a ‘caprice’ of the Alban hills, a tomb from the Via Appia, part of an aqueduct, blocks of fallen granite for a bench, and a fragment of a frieze, covered in vine leaves.

In this famous portrait Tischbein also did more than any other person to put the English off Goethe: first, by posing him in his cape so artificially, like a statue of a Roman river god; and second, by crowning him with that monstrous hat, a Paddington Bear hat—to coin a phrase, ‘der verfluchte Hut’, ‘that bloody hat’. Once seen, never forgotten, alas! We can no more think of Goethe without this hat, than of a medieval saint without his halo, or of Dante without his headgear (cf. fig. 49).

Goethe was more or less deaf to Dante, by the way, as he was to all manifestations of medieval culture in Italy (it is significant that the only thing he registered in Assisi was the classical temple façade, illustrated in fig. 43 above). His vision was rather blinkered, too, by conventional prejudices with regard to what the English guide-book called ‘the characters of the people’, that is, with regard to the scenes of daily life he could see on the streets or in society.

There are many pages in Die Italienische Reise where he laments the noise and confusion or the frequency of violence on the streets (fig. 50 is a melodramatic representation of a knife-murder on the Piazza del Popolo itself, just two years after he left). He complains about defective or non-existent plumbing, the filth on the streets (a recurrent theme), the appalling springs in the hired carriages, the beggars, the Roman Catholic church and Popish superstition. But although he is not without the typical tourist’s sense of superiority to the ‘natives’, he is capable of self-irony, referring to his knee-jerk reactions to Catholicism as his ‘Protestant original sin’; and at times he really does communicate his enjoyment of what was going on around him day by day—of the ‘Mitwelt’ as well as the ‘Vorwelt’.

He can be very funny about his adventures. I am sure you will enjoy his accounts of how he nearly got arrested as a spy because he was sketching a fortress near Verona, or nearly arrested as a smuggler, simply because he had gone up to Assisi on foot. He gives a very spirited account of how he went to see a comedy in Venetian dialect, where the action of the play was set on the streets of Venice. It led him to realise that you do not have to go the theatre at all in Italy, because Italians are always ‘theatrical’. And when he himself drew the very lively sketch (fig. 51) of a Venetian lawyer pleading in court, he knows that the real advocate is acting a part no less than his thespian counterpart would do on stage: both of them are to be judged on their performance.

The first is devoted to Naples (in fig. 52 you see one of the popular festivals for which the city was celebrated). It is a highly intelligent refutation of the charge that Neapolitans are congenitally—or rather ‘con-culturally’—idle, giving preference to a ‘dolce far niente’. Goethe sets out to prove paradoxically that no people on earth are more industrious, in their way.

The second is a description and study of the Roman Carneval—the week of Saturnalian licence before the beginning of Lent, which was centred on the very street where he lived, the Corso. fig. 53 shows the horses assembling in the Piazza del Popolo at the beginning of the famous race down the length of the street.

He is very attentive to the elaborate masks and costumes in the fancy dress worn during the Carneval (fig. 54 provides two illustrations from the original essay published back in 1789), and in particular to the frequency of cross-dressing.

*****

At this point it is time to shift the emphasis from those aspects of his ‘journey’ and his ‘journal’ which were shared with virtually all travellers of the time, to those where his experiences or reactions were unique. What were the things that made Goethe’s journey so different? And what are the qualities in his record that have sent so many Germans to follow in his footsteps and see Italy with his eyes?

I suppose the first thing that might surprise you are the affinities with the travels and travel-writings of men like Daniel Defoe or William Cobbet. Goethe is a man of the Enlightenment, interested in reform, progress, rationalisation. He notices signs of agricultural improvements in his brief journey through Tuscany, and he is interested too in defences against the sea in Venice, the draining of the marshes south of Rome, and in market forces and the economic life of Naples. But unlike Defoe and Cobbett, he had a genuinely scientific interest in climate, rocks and plants. He is always noting the interdependency of latitude, altitude, soil, rainfall, and crops, building-materials and manufacture, explaining the cultural differences between Germany and Italy as the necessary result of the differences between the two natural environments—Northern and Southern. These scientific interests were combining to lead him towards a theory of the evolution of plants, to such a degree that there are pages of The Italian Journey which read like the Voyage of the Beagle, the quest for the primal plant.

Another reason why his book is so much better as a record of what he saw than the journals of most earlier or later travellers is that Goethe was an amateur artist. He had taken drawing lessons as a boy and a young man, and during his second stay in Rome, he would spend a great deal of his time sketching and painting, and taking further lessons to improve his technique. Indeed, this was his main reason for staying on.

As he himself reluctantly conceded, he had left it too late; and we would probably say that his modest talent was almost suffocated by the academicism of his teacher, Hackert, and his friends. But he did develop a pleasing skill in the simplified treatment of large masses, whether these be architectural, as in the example in fig. 55, or purely geological, as in the Sicilian view in fig. 66:

When I first thought about this lecture, I had it in mind to give you an anthology of his analyses of great paintings—such as Veronese’s Family of Darius before Alexander (fig. 58), which has found its way into our National Gallery, or the frescos in the Sistine Chapel, or the Tapestries woven from the cartoons by Raphael. However, I decided such an anthology would take up too much space and be a little old hat, so I shall merely throw out the suggestion that Goethe’s practical experience in Italy as a keen amateur painter, under instruction from men like Hackert (who was no slouch himself, as you see again in fig. 59), helped him to make the kind of observations about the nature of colour and light that would lead to his later attack on the theories of Newton.

The next factor that makes his journey so different was its date, 1786–1788, whether you consider it as the moment in his own life, or as the moment in European history. He got back to Weimar only a year before the Storming of the Bastille; and the next 25 years were to be convulsed by the French Revolution and the Napoleonic Wars, which would in any case have made a journey like his impossible for much of the period. By the time he edited his journals and letters in readiness for the publication of Die Italienische Reise, after the battle of Waterloo, he must have realised he was looking back to a world of lost certainties.

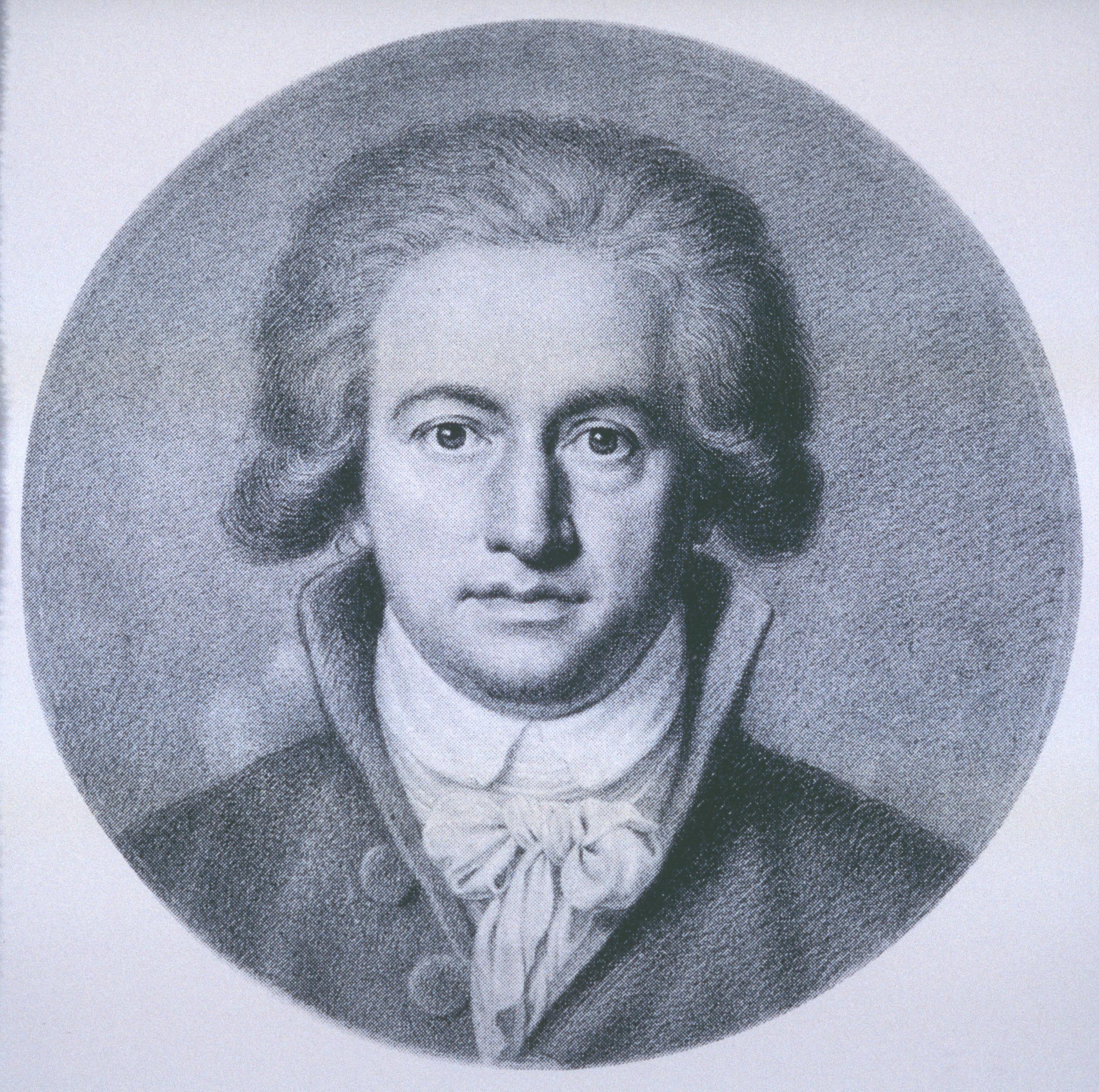

More important than the moment in European history, though, is the place of these years in Goethe’s own life. He was already 37 when he set out for Italy, a famous author, and a trusted professional administrator in a minor German state. Let me pause for a moment to recapitulate some well known facts.

Goethe was the son of a well-established lawyer, Johann Caspar (fig. 60 a), who had himself made a long journey to Italy back in 1749, and who had filled the hall of the family house in Frankfurt (so native-German in its style, as you can see in fig. 60 b) with engravings of the marvels to be seen there, and by so doing had filled his son with yearning to visit the country. (Incidentally, Goethe managed to learn Italian quite well from an early age, and unlike many of those who made the Grand Tour he was able to read poets such as Ariosto and Tasso with ease and pleasure.)

Like his father, Goethe qualified as a lawyer and had a good natural bent for practical affairs. But during the 1770s he made a name for himself as a daring, modern writer; a poet, dramatist and novelist who found his inspiration, not in France or the classics, but in Shakespeare and in the traditions of his native land. He drew on the indigenous legend of Dr Faustus; he wrote a play about the sixteenth-century rebel, Götz of the Iron Hand; he wrote an essay praising German (that is, Gothic) architecture; and enjoyed immediate success with lyrics and ballads in the style of German folksongs (Heidenröslein, for instance, was first published as a genuine Volkslied). Most important of all, in 1774 he published a short epistolary novel about an alter ego, a poetically-gloomy young man called Werther, who fell in love with the wife of his best friend and shot himself—a novel which was to become a runaway best-seller all over Europe, and hung round Goethe’s neck like an albatross for the rest of his life!

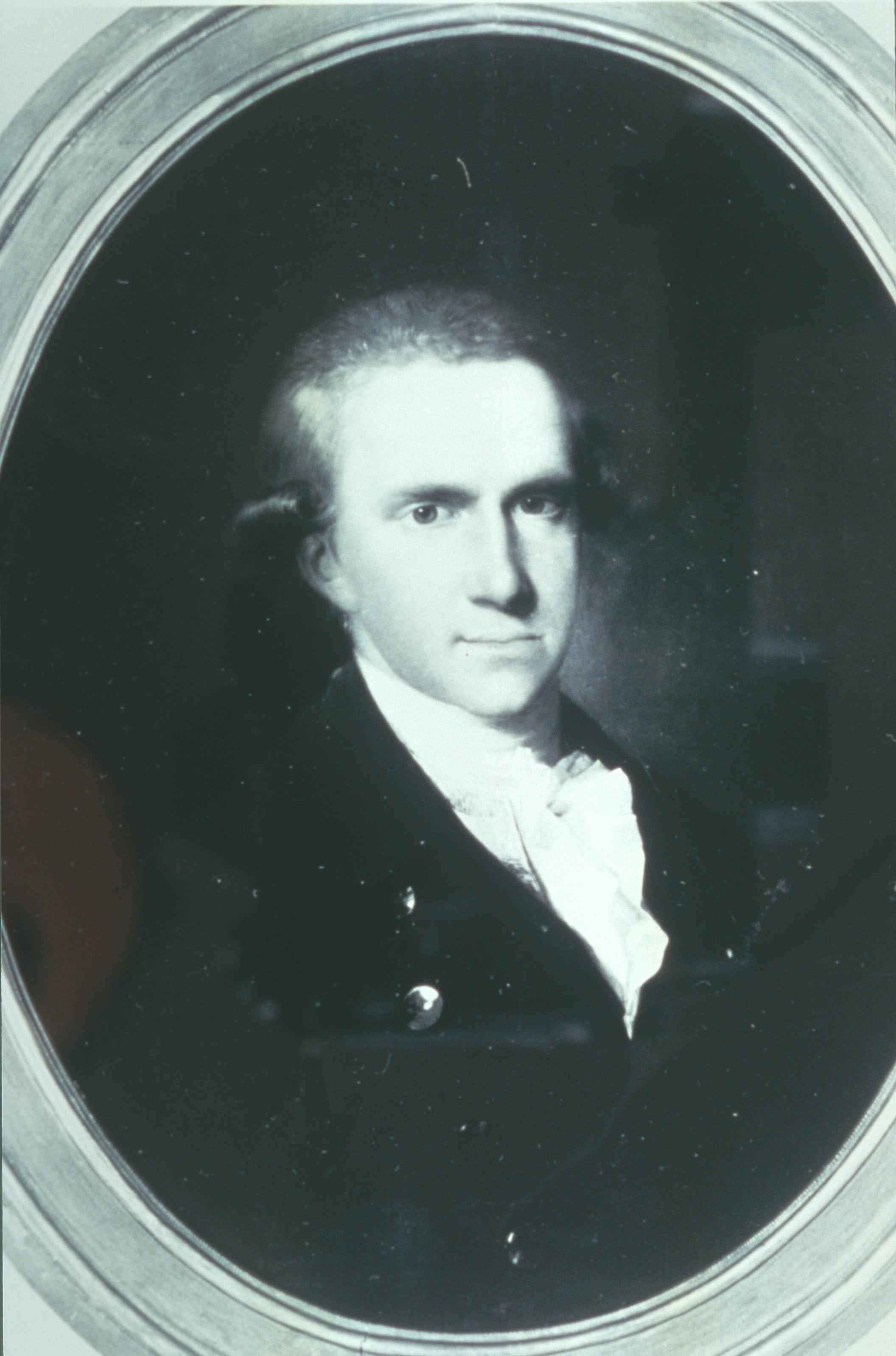

It was this literary fame that had led to his friendship with the adolescent heir of the tiny duchy of Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach, Carl August (fig. 61), a youth, eight years younger than himself, with whom he took employment in Weimar, late in 1776, as ‘General Superintendent’. The job was not a sinecure, and Goethe carried out his duties punctiliously.

Within a few years—fig. 62 offers a convincing likeness of Goethe as he was in 1779—he was responsible for the mines, roads and conscription to the army; and his duties took up more and more energy, leaving him less and less time for his writing. He had got stuck half-way with four major projects (plays that we know as Iphigenia, Faust and Egmont, and a long novel about another alter ego that we know as Wilhelm Meister and his Theatrical Mission). He desperately wanted to have a real break from his work; and he had been dreaming of a journey to Italy for a long time, with all the intenstiy of the famous poem of yearning which he included in the novel:

Kennst du das Land, wo die Zitronen blühn,

Im dunkeln Laub die Gold-Orangen glühn,

Ein sanfter Wind vom blauen Himmel weht,

Die Myrte still und hoch der Lorbeer steht –

Kennst du es wohl?

Dahin! Dahin

Möcht’ ich mit dir, o mein Geliebter, ziehn!

Mignons Lied, 1–6.

Do you know the land where the lemon-trees blossom,

golden oranges glow in the dark foliage,

a gentle breeze blows from the blue sky,

the myrtle stands still and the laurel tall?

Thither! Thither

would I like to go on a journey with you, my beloved.

He knew that a prolonged absence would be controversial. So he laid his plans in great secret, asking the Duke for indefinite leave with just three days notice. And he left Weimar at the crack of dawn on September 3rd, without even the Duke knowing where he was going. In this perspective, then, the Italian journey began like a volcanic eruption or a political revolution; or (if those tempting analogies are exaggerated) it began like an adolescent running away from home.

In reality, however, it was not a true kicking over the traces, and he had not burned his boats. Despite the mystery and the surprise, in retrospect it all seemed like a carefully planned and fully justified ‘Sabbatical Leave’. He had recently signed a contract to publish his collected works in eight volumes; three of the volumes were ready (since he only had to revise what was already in print); and by the end of his Sabbatical he had virtually completed the unfinished works that make up the other five. In Italy, he would collect material for the essays I mentioned, some of which would appear shortly after his return; and he negotiated a better contract, a higher salary, with more support-staff, when he resumed his duties in Weimar. We could sum up the whole episode by paraphrasing the opening of a famous Latin hymn by Abelard: ‘O quantum et quale fuit illud sabbatum’. And these are the factors behind my choice of the title of this lecture: North-southerly Sabbatical.

*****

There were other dimensions to his prolonged absence for which you have to read more between the lines in the Italienische Reise, because the journey was also a quest for love and self-knowledge. I would dearly like to tell you something about them, but for reasons of space I must simply call your attention to the excellent chapter in the first volume of Professor Boyle heroic biography (Goethe: the poet and the age), and do no more than indicate three of the headings in the section I have had to renounce.

Throughout his ten years at Weimar Goethe had been deeply, but platonically, in love with a married woman, Charlotte von Stein (cf. fig. 64), seven years older than himself.

She was his ideal, the model of his Iphigenia, to whom he wrote lovely spontaneous letters and notes almost every day, and some very moving lyric poems. But as he laments in one of the best-known of these lyrics, she was his soul-mate, but not the daily companion of his bed; and by 1786 she was in her middle 40s. As we now say, so lamely, he wanted to be ‘out of this relationship’, to be able to enjoy the undemanding and physical love of a less complicated person, the kind of person he had imagined as the youthful mistress of Count Egmont—not an Iphigenia, but a Klärchen (whom you see in the evocative image from the first edition of Egmont (dated 1788) in fig. 64).

The long absence did indeed (to use another modern and trite expression) ‘do the trick’. He never broke with Charlotte, but she was deeply hurt by his running away without telling her, and she found him greatly altered on his return. A month later he met Christiane Vulpius, a buxom young woman of 23 (whom you see in fig. 65 in his own sketch), and in no time at all they were lovers—he had found the head for his second pillow.

He set up house with her, fathering his first illegitimate son in the following year. So the journey to Italy was one from Charlotte to Christiane.

Between these two loves, however, there had been other significant moments. The most important in the long run was his liaison in the winter months of early 1788 with a young Roman widow, who was the precursor of Christiane (her name, in real life, it would seem, as well as in poetry, was—believe it or not—Faustina). Of course, he says nothing at all about her in the book, and we shall come back to their affair at the end. But there were also three moments of unconsummated attraction, which he can and does describe in the book, and I find these pages some of the most moving and revealing.

The Italienische Reise also gives some fascinating glimpses of the metaphorical journey in discovery of his inner self, ‘spying out’, as he would later say, ‘the gloomy paths of his discontented spirit lost in contemplation of his “Ich”’. When you read the book, watch out for the roles he plays under assumed names, which range from Jean Philippe Möller, a merchant, to Mr Wilton, an Englishman, and to Megalio Melpomene, an honorary member of the Literary Society of the Arcadians. Remember too that these fictitious identities which he assumed in real life—in ‘Wahrheit’—were companions to those he was taking on almost every morning, when he sat down at his desk to continue work on the various pieces of make-believe—of ‘Dichtung’—which he had carried with him to Italy: Faust the striver; the exiled Iphigenia, ‘seeking the land of the Greeks with her soul’; Tasso, the paranoid poet so uncomfortable at court; and several others besides.

After these mere hints at what you can read between the lines in the book or explicitly in Professor Boyle’s biography, I am ready to come back to the strange compound adjective in the title of my lecture, ‘North-southerly’.

In the event, the paintings and sculptures that Goethe learned to understand in their context were almost exactly the same as those which appealed to other contemporary travellers. You see them again in the 1750s souvenir shop painted by Panini (cf. fig. 44)—which was somewhat up-market from what you might now find on King’s Parade, as the detail in fig. 66 will confirm:

But unlike the others, Goethe was discovering this kind of art for himself, as a mature man of 37, coming to it as not just as a well-educated tourist, but as a writer who had been an angry young man, a romantic before the word had been invented, whose work had been characterised by every quality except restraint and noble simplicity, and who had polemically celebrated the despised culture of his native land. The journey was the culminating point of his conversion to the values of classical civilisation. What he wanted to find in Italy, and of course duly found, was ‘greater Greece’: magna Graecia. In Horace’s famous phrase, he had gone to study ‘the art of captive Greece which captured Rome’ (cf. fig. 67).

What made all the difference was the opportunity he had daringly created to study this art in its geographical context. Hence—like so many others before and after him—he came to polarise the differences between his native German culture and that of ‘Greater Greece’ (alias Italy) as differences between two mythical entities called North and South (‘pazienza’ that there are only nine degrees of latitude between Weimar and Rome!).

In the early years of Goethe’s life there had been, so to speak, a ‘direct’ current between the North and South poles, flowing just one way at a time: first, the South had been rejected in favour of the North; then it became a longed-for mirage. But once he had returned from his journey, there was an ‘alternating’ current between the poles—or to go back to the terms I introduced at the beginning, there was a ‘North-southerly’ synthesis. And in this synthesis—or so it might have seemed in 1816—there had been a reconciliation and a ‘Steigerung’ of all the different theses and antitheses that had entered into his being: his father’s earnestness and his mother’s gaiety; science and poetry; love for Charlotte and love for Christiane; modernity and reverence for the past; masculinity and femininity.

So all these contrasting dualities, and many more, were subsumed in the greater reconciliation between the North—cold, indoors, Protestant, buttoned-up, hard-working and provident—and the South—warm, outdoors, relaxed, pagan, infuriating, but so, so beautiful. Italy was the place where he himself became North-Southerly, where his water ‘balled itself’.

*****

That, then, is my introduction to his journey, and to his account of the journey. The Italienische Reise is a splendid book; and I hope you will read it, or re-read it, before planning your next summer’s holiday. But obviously the whole cumulative experience of Italy would not be of great interest to us as readers, if it had not led to creative writing of a kind we would not otherwise have enjoyed; and I should not be doing my job in this lecture if I did not end by pointing, at least, to a few of the works which would not have existed without the journey.

Working backwards, I would say the most important of these works were the following: the last four acts of Faust Part II; the classical drama he finished there, Iphigenia, and the Renaissance play he was working on, Torquato Tasso; and, most obviously, his Roman Elegies—where ‘Elegies’ means sensual and joyous love poems in the manner of Ovid and written in the metre of Ovid’s Amores (that is to say, in couplets formed of a hexameter followed by a pentameter, with strict rules governing its caesura and last syllable). These poems illustrate virtually everything I have been trying to say, so I shall share with you a dozen or so lines by way of a conclusion.

Thematically, they are recreations—in a modern and Northern language—of classical love poetry in classical metre. But they are also an evocation of the city and its life as Goethe had experienced them in the 1780s: they are, as I put it earlier, a synthesis of ‘Vorwelt and ‘Mitwelt’. And at the same time they are a self-portrait of himself as the young Northerner discovering, and accepting, himself and his sexual desire.

Poetically, they are full of charm, wit, tenderness, sex, learned allusion and self-mockery. You can recognise some of these qualities already in the very first lines of the cycle, in the mock-solemn apostrophe to the ruins, buildings and streets of Rome.

Saget, Steine, mir an, o sprecht, ihr hohen Paläste!

Straßen, redet ein Wort! Genius, regst du dich nicht?

Ja, es ist alles beseelt in deinen heiligen Mauern,

Ewige Roma! nur mir schweiget noch alles so still.

Römische Elegien, I, 1–4

Tell me, you stones, speak out, you towering palazzi!

Streets, say a word! Genius loci, will you not stir?

Yes, everything is quick with life within your holy walls,

eternal Rome; only for me is everything still so silent.

Rome will not speak to him yet, because he has not yet found ‘Love’—the god of sexual love, Cupid, or rather, Amor, which is simply Roma spelt backwards, a palindrome. This discovery was promptly made, and is celebrated in some lovely poems, of which there is only space to give you a six-line example, taken from the very well-known fifth elegy:

Aber die Nächte hindurch hält Amor mich anders beschäftigt;

Werd’ ich auch halb nur gelehrt, bin ich doch doppelt beglückt.

Und belehr’ ich mich nicht, indem ich des lieblichen Busens

Formen spähe, die Hand leite die Hüften hinab?

Dann versteh’ ich den Marmor erst recht; ich denk’ und vergleiche,

Sehe mit fühlendem Aug’, fühle mit sehender Hand.

Römische Elegien, V, 5–10

But through the nights Cupid keeps me busy in another way;

If I become only half the scholar, I am twice as happy.

And is this not learning, to study the forms

of her lovely bosom, and glide my hand down over her hips?

For then I understand marble all the better: reflecting, comparing,

I see with an eye that feels and feel with a hand that sees.

Reluctantly, I cut him short there, so that we can end with a poem which combines Northern vowels and consonants with a Southern metre, while contrasting the sun and joy of the South with the grey skies and dark mood of life in the North:

Oh, wie fühl’ ich in Rom mich so froh! gedenk’ ich der Zeiten,

Da mich ein graulicher Tag hinten im Norden umfing,

Trübe der Himmel und schwer auf meine Scheitel sich senkte,

Farb- und gestaltlos die Welt um den Ermatteten lag,

Und ich über mein Ich, des unbefriedigten Geistes

Düstre Wege zu spähn, still in Betrachtung versank.

Nun umleuchtet der Glanz des helleren Äthers die Stirne;

Phöbus rufet, der Gott, Formen und Farben hervor.

Sternhell glänzet die Nacht, sie klingt von weichen Gesängen,

Und mir leuchtet der Mond heller als nordischer Tag.

Römische Elegien, VII, 1–10

Oh how glad I feel to be in Rome, as I remember those times

back there in the north, when grey days clung about me

and the gloomy sky pressed heavily down on my head,

and I was surrounded by a colourless, shapeless, dulling,

exhausting world, and would sink into contemplation of my ego,

trying to spy out the dark paths of my discontented mind.

Now the radiance of a brighter aether shines round my brow;

Phoebus, the god, calls forms and colours into being.

Brilliant with stars, the night resounds softly with singing;

and the moon shines more brightly than the northern day.

FIXME: - - - lecture ends; there are two further slides in the carousel which I have reproduced below in case we want to insert them anywhere - - -

![Figure 5: (O_G_5) Carlevarijs’ The Molo with the Ducal Palace (left) and [FIXME: painting title needed] (right)](media/image5.jpeg)

![Figure 14: (O_G_14) Joli’s [FIXME: title needed]](media/image14.jpeg)

![Figure 37: (O_G_37) L’Orizzonte’s [FIXME: title needed] (left) and Claude’s Landscape with Shepherds—The Ponte Molle (right)](media/image37.jpeg)

![Figure 46: (O_G_46) [FIXME: caption needed]](media/image46.jpeg)

![Figure 49: (O_G_49) [FIXME: caption needed]](media/image49.jpeg)

![Figure 52: (O_G_52) Joli’s [FIXME: title needed]](media/image52.jpeg)

![Figure 54: (O_G_54) [FIXME: caption needed]](media/image54.jpeg)

![Figure 55: (O_G_55) [FIXME: caption needed, something along the lines of Goethe painting of Palatine Ruins?]](media/image55.jpeg)