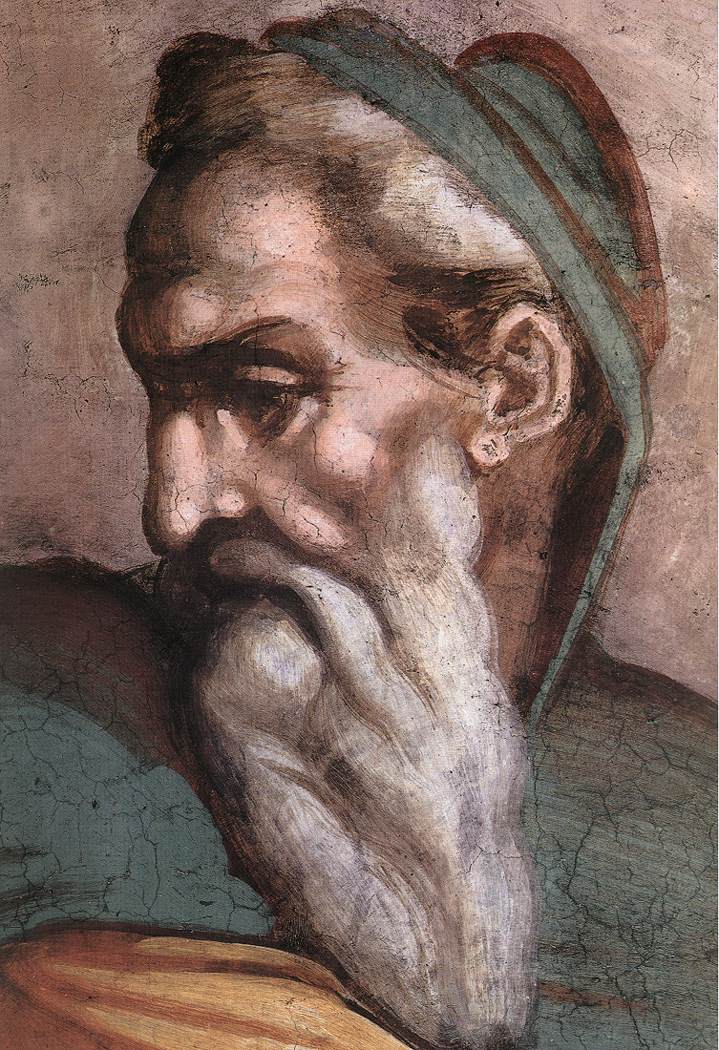

Michelangelo: The Ancestors of Christ

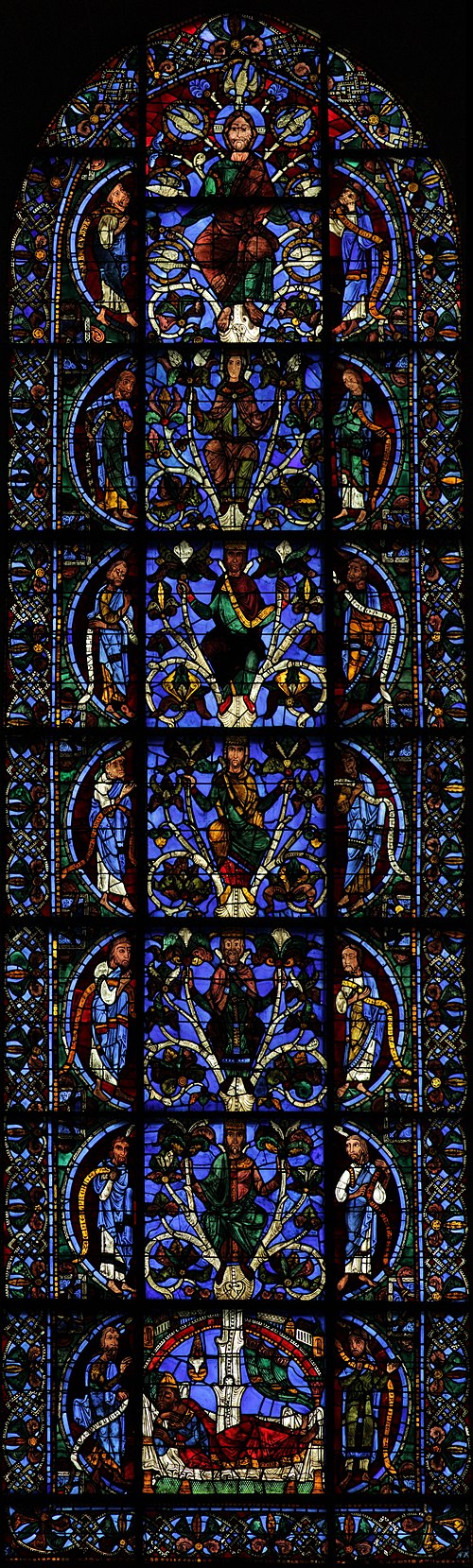

My subject in this lecture is ‘The Ancestors of Christ’; the figures painted by Michelangelo at the top of the wall in the Sistine Chapel, in the lunettes over the windows and the triangular spandrels above them (both visible in the composite slide of the south wall in fig. 1).

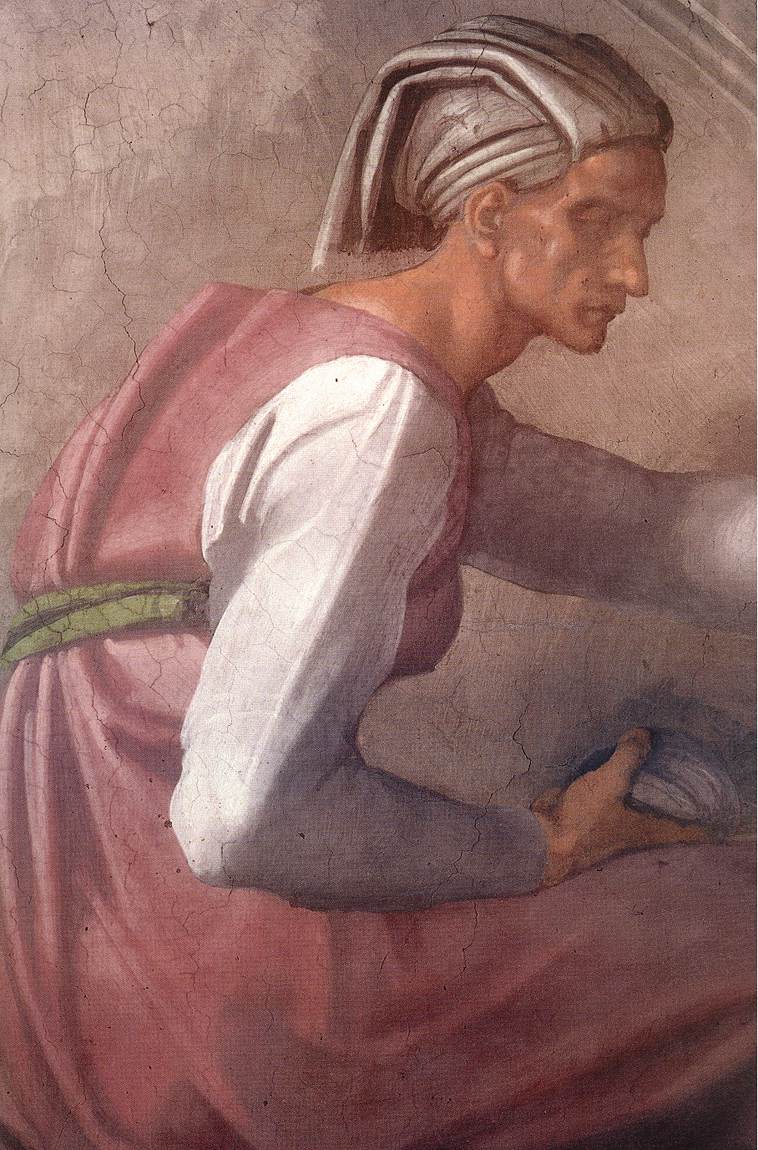

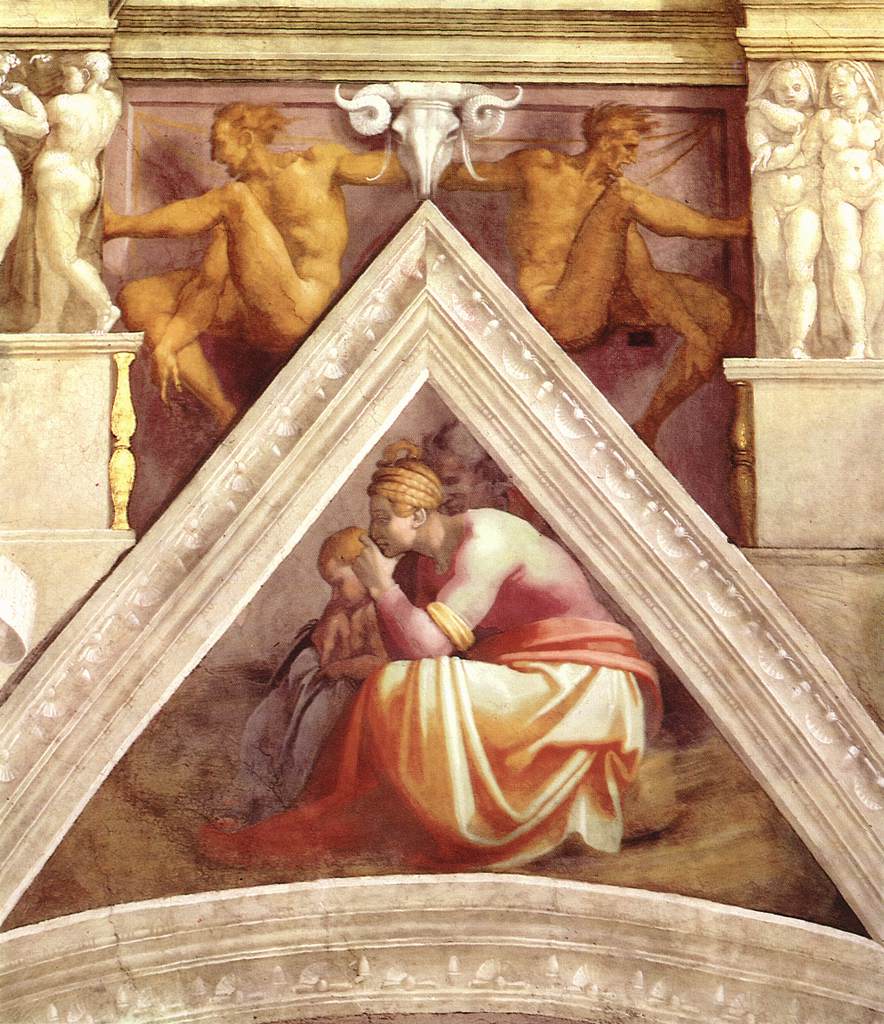

Freed from the need to paint over his head (cf. Lecture 3, fig. 3), and able to do all the work in the vertical plane, he abandoned the use of elaborate drawings enlarged to a cartoon, and proceeded immediately from a sketch or a life study to the wall itself, working straight onto the wet plaster without any guide-lines, and doing each half of the lunette in a single day. The brushwork was so impetuous that the restorers occasionally found bristles from the brushes stuck in the plaster; and he gave free rein to his fantasy. He creates wonderful headgear, and seems to have taken down from life a snapshot of a girl drying and combing her hair in fig. 6a:

And remember always that in this free, improvisatory mode of painting, he was still capable of delicate insight and poetry, as in the images of a young pregnant mother asleep (in fig. 10; I call her Peninah, without Biblical authority), or of a middle-aged mother virtuously at work winding wool (in fig. 11; who is certainly Bathsheba):

I could go on and on; but you will have gathered that I am still totally bowled over by these figures (which I had hardly noticed before 1986)—so overwhelmed, in fact, that I want to give them a whole lecture to themselves for their own sake.

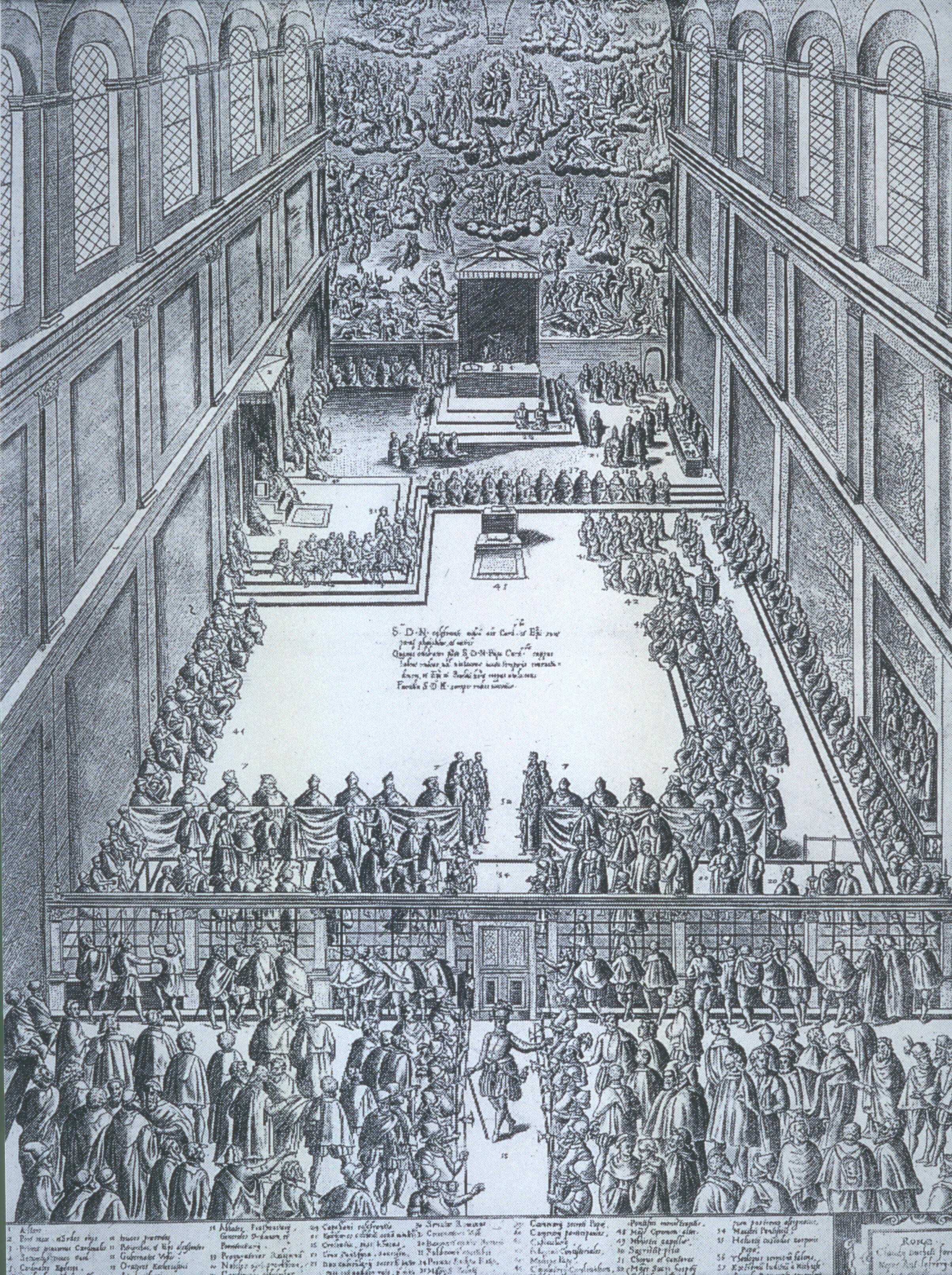

But there is more to come. From the sixteenth to the eighteenth century, the Sistine Chapel was almost as famous for its choir as for its frescos, and I have long wanted to say something about the music that was sung in the Chapel from the lovely Singers’ Gallery or Cantoria (fig. 12), with its inscription Psallite Deo—‘Sing Psalms to the Lord’—which originally bisected the screen that separated the clergy from the laity (as is shown in the reconstruction of the interior of the Chapel as it was before Michelangelo started work in about 1505, in the engraving in fig. 13).

And I cannot talk about the music in the Chapel in this period without saying something about Josquin des Pres (fig. 14), who had been a singer-composer in the chapel during the 1490s.

Josquin is regarded as the greatest composer working in the early years of the sixteenth century, and it was a natural temptation to talk about him in tandem with Michelangelo, the greatest painter of the age. The temptation was reinforced when I realised that the pairing of these names is not just an anachronistic whim of our own time. Martin Luther himself had said of Josquin that he was ‘the only composer who made the notes do what he wanted them to’; and more importantly, in 1543, another writer remarked that Josquin was to music what Michelangelo is to art. I then learnt that Josquin had written a motet, setting to music the names of the Ancestors of Christ—all of them—and that this motet had been copied out into a choir book in the Sistine Chapel. Indeed, it had been copied—and therefore presumably sung—around 1510, in the very years that Michelangelo was at work on the lunettes and ceiling. And to clinch the matter, I soon learned that this particular motet had been singled out (as late as 1547) by the famous Swiss theorist known as Glareanus, who praised it for its majesty and teeming invention, despite the apparently barren text, which, he said, was no more than a ‘nuda…nomenclatura’.

Cantio magnam habet maiestatem, mirumque est in tam sterili material, in nuda scilicet virorum nomenclatura, potuisse tot effingere delicias, perinde atque esset foecunda aliqua historia.

Glareanus, Dodecachordon, Book III, p. 365.

The song has great majesty and it is astonishing that from such a barren matter, namely, a bare list of men’s names, it was possible to create so many delights, just as if it had been some narrative teeming with events.

I also found that this motet about the Ancestors had suffered from the same neglect as Michelangelo’s images of the Ancestors had done. (A commercial recording was not finally released until 2003, ten years after my first attempt at this lecture). So I procured the score, and realised that it was indeed a masterpiece, and, more importantly, that the challenge of the text to Josquin had been closely comparable to its challenge to Michelangelo. In both cases, the artist—be he painter or composer—had responded to a seemingly impossible technical constraints, and had sought to give as much variety as possible to the ‘nuda nomenclatura’, to this bare list of names.

With all these factors in mind, I devised a lecture which would provide an accessible introduction to both works, concluding with a live performance of the motets (sung by members of the St John’s College Choir), synchronised with a re-projection of all Michelangelo’s images—a Son et Lumiere to end all Sons et Lumieres!

It is this lecture which is here reconstituted umbriferously (that is, as a mere shadow) on the page. Sadly, you will have to ‘make your own accompaniment’, with the help of the recording mentioned above (Decca CDGAU306).

Before we look at either the music or the images in detail, we must take a glance at the text which conditions both of them—the nomenclatura virorum, as Glareanus calls it—which proves to be none other than the opening words the Gospel of St Matthew, and, as such, the opening words of the New Testament.

Liber generationis Jesu Christi

Filii Abraham, filii David.

Abraham genuit Isaac.

Isaac autem genuit Jacob.

Jacob autem genuit Judam et fratres eius.

…

Mathan autem genuit Jacob.

Jacob autem genuit Joseph, virum Mariae,

de qua natus est Jesus, qui vocatur Christus.

Matthew 1:1–2, 15–16.

The first sixteen verses of Matthew’ Gospel, then, consist of a long list of names, all in the identical form: ‘A begat B’; ‘B for his part (autem), begat C’; and so on. The list gives the names of all the ancestors of ‘Joseph, the husband of Mary, of whom was born Jesus, who is called the Christ’ (that is, ‘the Anointed One, the Messiah’) going right back to Abraham, whose name was changed from plain ‘Abram’ to ‘Abraham’, which means the ‘Father of a Multitude’!

Everyone who writes about this list in modern times seems to find it ‘unpromising’, to say the least—and this is the bad news for you, for the composer and for the artist. But the news is not all bad. In the first place, there can be a literary pleasure in lists of proper names. Leaving aside the famous catalogue of the Greek ships and detachments in the second book of the Iliad, or the roll-calls of heroes in all the literary epics that descend from Homer, I think of one poignant example assembled in a work of popular fiction from Michelangelo’s lifetime (c. 1475): the intensely moving list of the Knights of the Table Round towards the end of Malory’s Morte d’Arthur. The fact that all 110 knights are unable to heal Sir Urry of his wound is the agonising symbol of the decadence of the Table Round, which in turn was the prelude to the quarrrels which lead to the Death of Arthur.

Or to take another tack: most of us seem to be interested in our roots, in explaining who we are by our ancestry, by our inherited genes. And I have to confess that I felt an absurd sense of pleasure and rightness when a cousin of mine on my mother’s side, who had spent some twenty years working on the family tree, was able to show that one of my remote ancestors was an Italian—so that my becoming a professor of Italian could be read as a ‘fulfilment’ of the remote historical accident that an English aristocrat on the Grand Tour had to recruit a servant, one Giuseppe Malone, who ended up in Oxfordshire as the family gardener (having anglicised the spelling as Mellonie).

A third and more serious consideration is that Matthew is the ‘most Jewish’ of the four Evangelists, and hence the unpromising opening may be interpreted as being one of the ways in which he sought to establish his credentials with his first audience. The book of Genesis is full of such genealogies; and the phrase Liber generationis is in fact taken verbatim from Genesis 5, ‘this is the book of the generation of Adam’. (Indeed, the Greek word for generatio, used in Matthew, is none other than genesis; and there are similar genealogies in all the historical books of the Bible.)

There is still a lot more to be said, however, about the list in itself. Matthew is the evangelist who keeps using the phrase ‘so was fulfilled the prophecy’; and he is consistently anxious to assert that Jesus is a king in a line of kings, the promised Messiah from the house of David. It has been said, too, that placing this typical genealogy at the very beginning of his gospel is his way of saying, in effect, that you must read the ‘New’ Testament as the fulfilment of the ‘Old’. And, of course, this is precisely how the Popes wanted us to interpret the parallel lives of Jesus and Moses (cf. Lecture 2).

As you can see in the tabulated list of names below, Matthew is not without a sense of form and pattern—a dangerous things for a historian, but attractive to the artist. His list is divided into three equal parts, each of fourteen generations (and it is no apparently no coincidence that when letters are used as numbers in Hebrew, the three consonants in DaViD add up to 14 (4 + 6 + 4. You will also see from the table that the divisions between the three groups coincide with turning points in Jewish history. The first goes from Abraham down to David, who united the twelve tribes into one kingdom, and the opening names are not exactly unknown to fame.

| From Abraham to David | The kings of Judah | After the deportation to Babylon |

|---|---|---|

|

|

(14. Jesus) |

The second set consists of kings who ruled over the Southern Kingdom of Judah. In the judgement of the chroniclers who wrote the second book of Kings and the second Book of Chronicles (whose moral verdicts at times remind one of 1066 and All That), half of them were good, but half were bad, or behaved badly at the end of their reigns, with the result that in the end the Lord punished their transgressions by destroying the Kingdom, Jerusalem and the Temple, and having all the Judaeans deported to Babylon for a period of about 60 years.

The final set contains no more than obscure names: they represent the humble condition of a long period in which the regenerated state of Judah was no more than a minor province in foreign Empires. They are the Judaeans (whom we call Jews) who lived in the hope that they would be delivered by a ‘Messiah’, the Anointed One (in Greek ‘Chrestos’, the Christ), who is the subject of Matthew’s Gospel and the New Testament…

The other interesting feature of this genealogy, which the table does not show, is the explicit mention in the first group, of four wives and mothers whose sex lives had been a little unorthodox, or who had given rise to scandal: Thamar and Rahab, then Ruth (of whom Michelangelo gives a particularly loving interpretation in fig. 19), and Bathsheba, the wife of Uriah the Hittite, who became David’s wife in such a disgraceful way (through no fault of her own, as Michelangelo is perhaps at pains to underline by showing her in fig. 20b as a paragon of the domestic virtues in middle age).

These two expressive images also demonstrate that Michelangelo does not simply match each name in the genealogies with a single male face, but in most cases shows us a whole family. With all these factors in mind, then, let us now examine in detail how Michelangelo rose to the artistic challenge of the nuda nomenclatura.

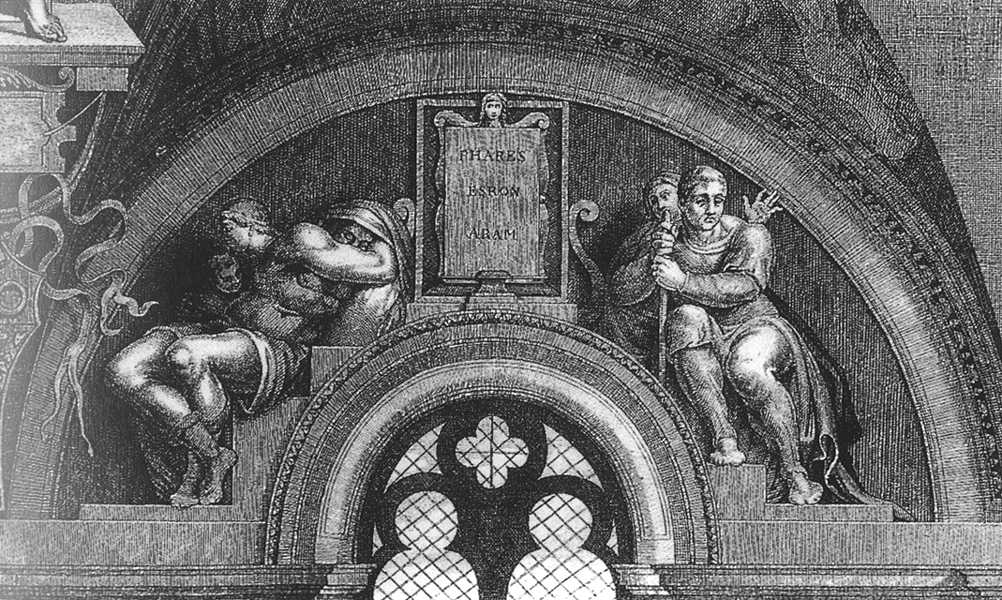

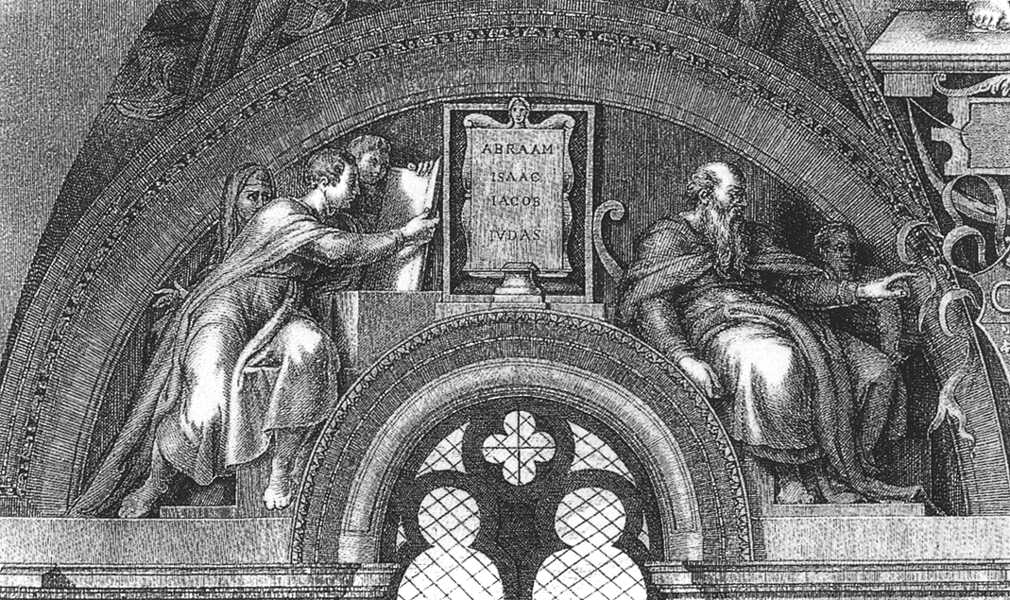

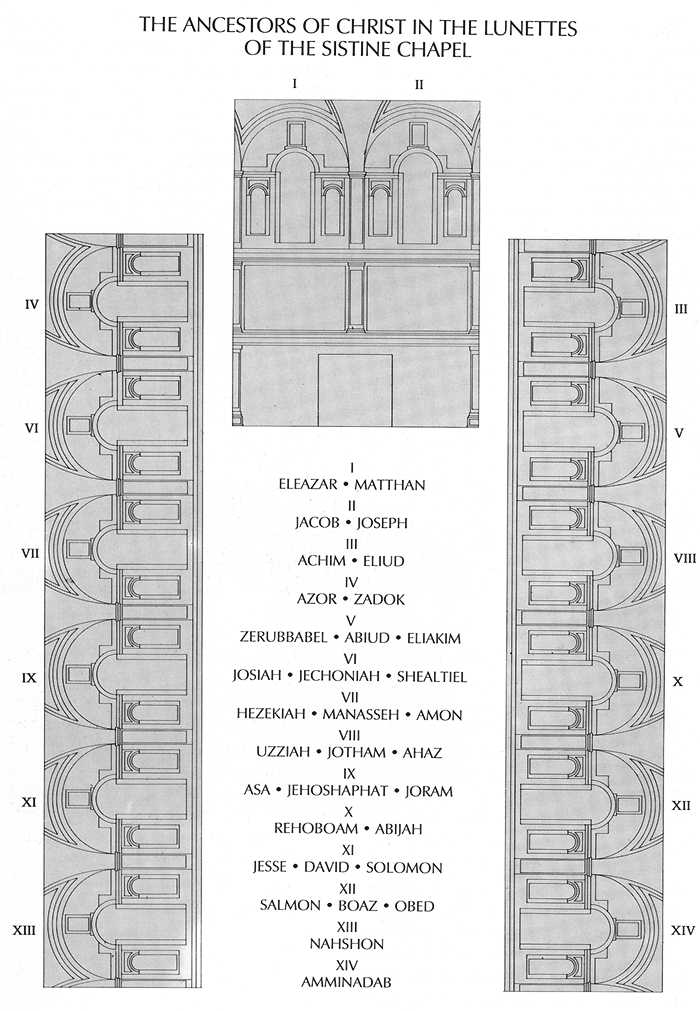

I remind you first of the spaces—the very awkwardly shaped spaces—into which he had to fit the figures. First come the lunettes over the windows. There used to be sixteen in all (six on each of the side walls; and two on each of the end walls), but Michelangelo himself later acquiesced in the bricking up of the windows on the altar wall and the consequent destruction of the lunettes there, which we know only from the engravings in fig. 21. These engravings, however, make us vividly aware of the challenge posed by the half-moon shape: getting human bodies to fit inside the crescents is like squeezing into a crowded underground train on the Piccadilly line, just inside the doors, during the rush hour.

The second set of spaces available were the eight triangular spandrels lying over the windows in the centre of the side walls, four on each side, of which you see examples in figs. 23, 24. Bear in mind that, unlike the lunettes, the painted area is doubly curved (as illustrated in Lecture 1, fig. 5) because the spandrel is scooped out of the barrel vault of the ceiling.

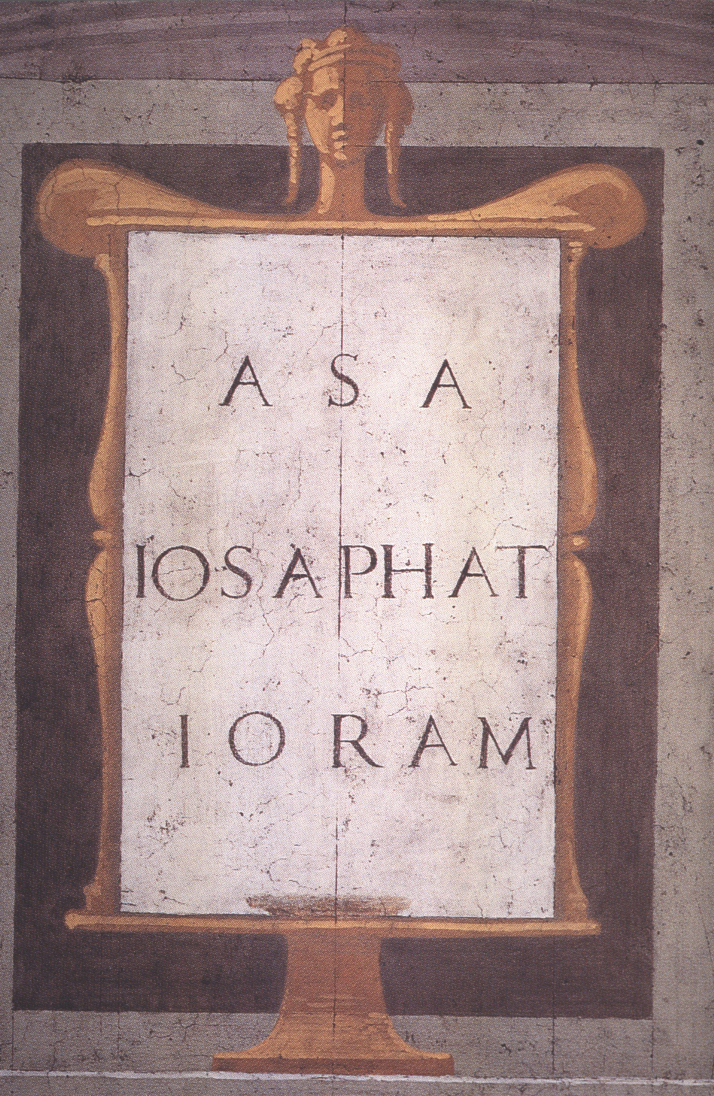

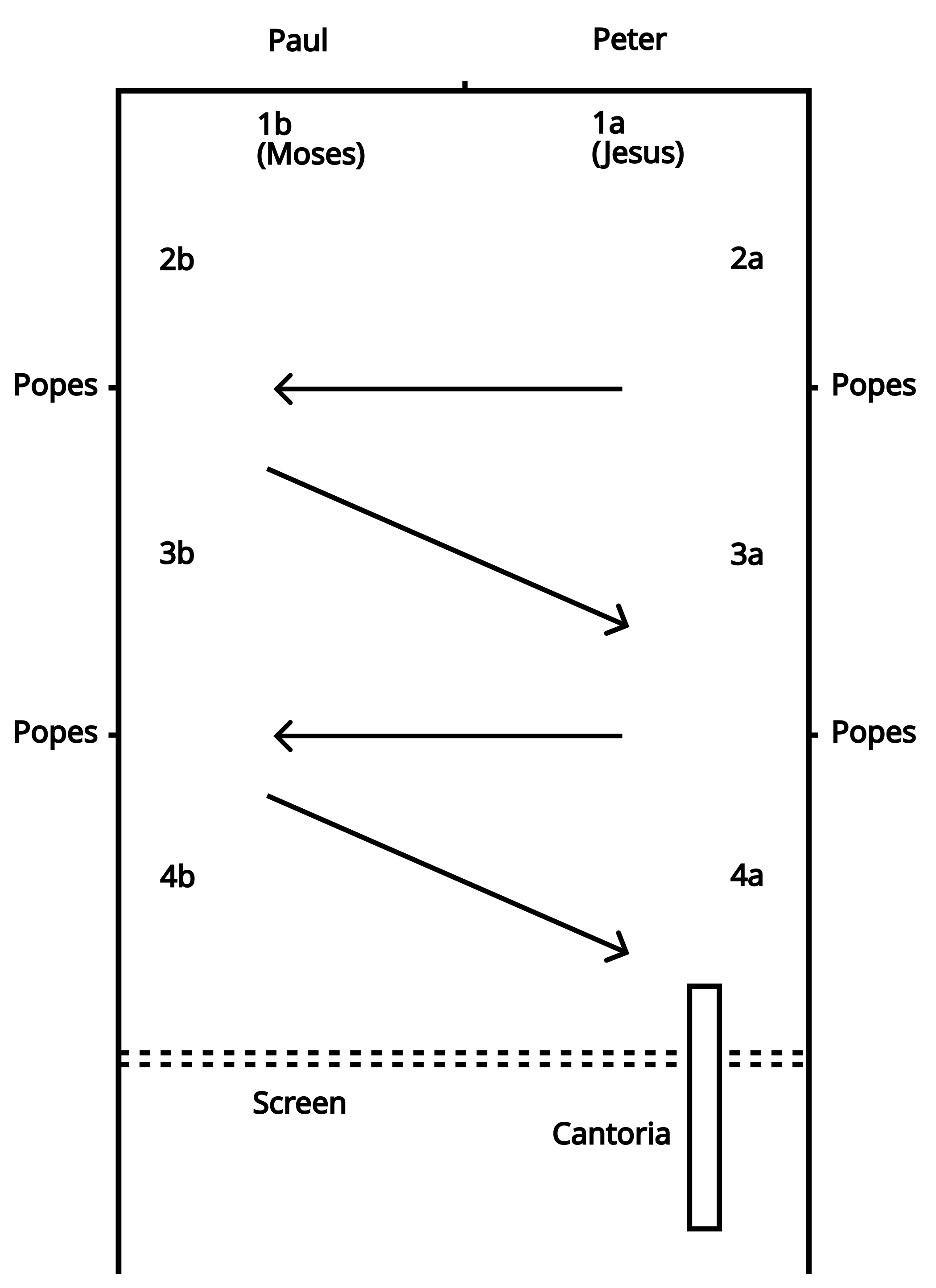

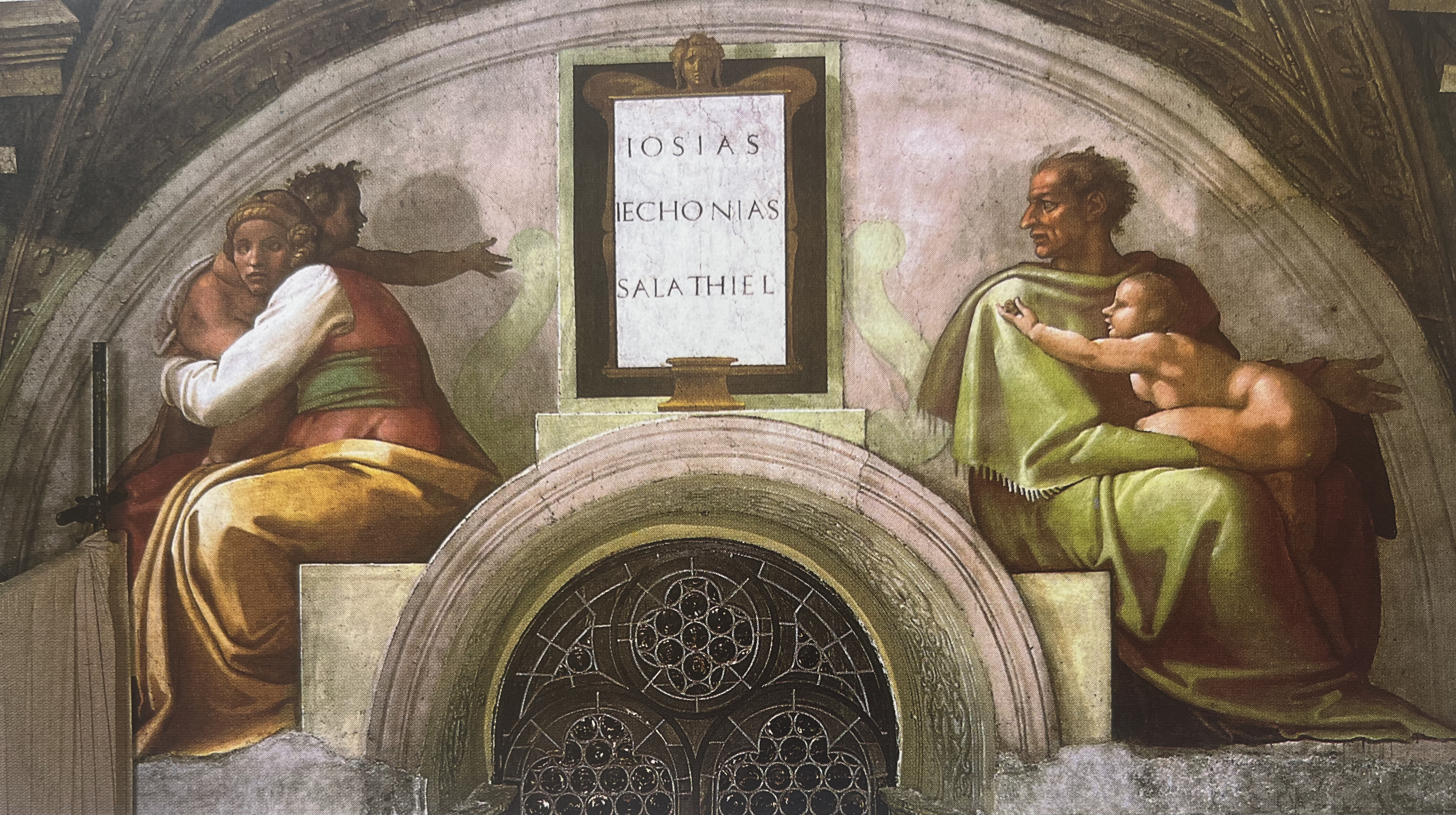

How do we know who is meant to be who in the lunettes and spandrels? As you can see in the engraving in fig. 21 and in the detail in fig. 25, the male names were all written out in capital letters on shields placed at the top of the lunettes. And the shields tell us, first and foremost, that Michelangelo was asked to respect the principle governing the sequence of the first thirty popes, whose simulated statues were painted in the 1480s and lie on either side of the windows below the lunettes. As you can see in fig. ¿fig:R2_5?, the sequence began on the left of the altar wall, moved to the other side of the same wall, and proceeded thence alternately, marching ‘left–right, left–right’ all the way down the chapel to the entrance.

These shields, then, offer us an indispensable guide, but they do not answer all our questions unambiguously. So please remember that, whenever I attribute specific names to specific figures in this lecture, I am making the following assumptions:

- the highest name on a shield refers to a male the family in the spandrel above (although one cannot be sure whether the name refers to the father or to the begotten son).

- where there are two names that must belong to the lunette, the first refers to the father, if there is only one adult male.

- where there are two adult males, one on each side, the first refers to the male on the left on the North Wall, but to the male on the right on the South Wall. (This decision is in harmony with the direction of the imagined fall of the light in the paintings (always from the altar wall), with the sequence of the narrative frescos on the walls and ceiling, and, as explained above, with the sequence of the popes on the relevant wall.)

- on the end walls, the lunettes to the South of a central line follow the conventions governing the South wall, and those to the North of the line, the conventions of the North.

In fig. 27, you see a diagram of the spaces that concern us which may help to clarify the foregoing and will enable me to make two further important points about the general design.

As you saw, there are exactly forty distinct names in Matthew’s list, and they could all have been distributed evenly, if Michelangelo had allocated two names to each of the lunettes (16 × 2 = 32), and one to each of the eight spandrels. This is precisely what he does in the Eastern half of the chapel (the end which he frescoed first, but which contains the later Ancestors). However, in the Western half, three of the lunettes (those coloured in green) contain only one name. The result is that there were three names left over, and so the (now non-existent) lunettes on the altar wall, did not have just two names each as they might have done (there being no spandrels), but three names on one side, and four on the other! (You can make them out in the engravings in figs. 21, 22).

The effect of the juggling (as I have tried to show by my use of blue in the diagram), is to make Matthew’s first set of fourteen names coincide with the first third of the chapel: the crucial name of ‘David the king’ refers to the father in the second lunette on the North Wall, exactly one third of the way down the chapel.

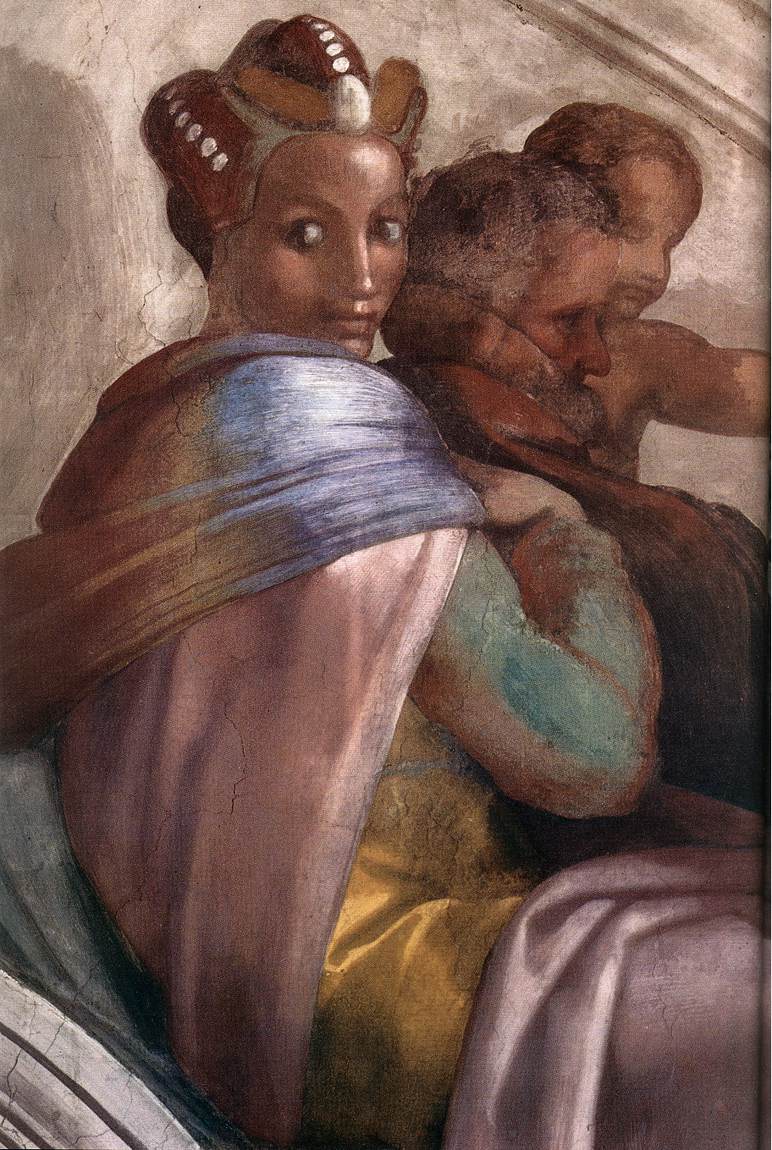

It was probably the same sort of concern that led to another disturbance of the expected pattern in the Eastern End of the Chapel. As you can see in the doctored diagram, the alternation ‘left-right, left-right’ is interrupted at number eleven, which should be on the South Wall. The result is that Jechonias (whose name begins the last group of fourteen generations in Matthew’s list) is highly visible in the lunette on the North wall; and thus the last third of the chapel coincides with the last third of the names.

So much for the general design and the minor adjustments to it. I now pass on to the all-important subject of the variations that Michelangelo introduced to diversify the list of names, and to fill the impossible shapes of lunette and spandrel without any sense of strain or repetition. I will begin with the resources of colour, the first thing I fell in love with in 1986.

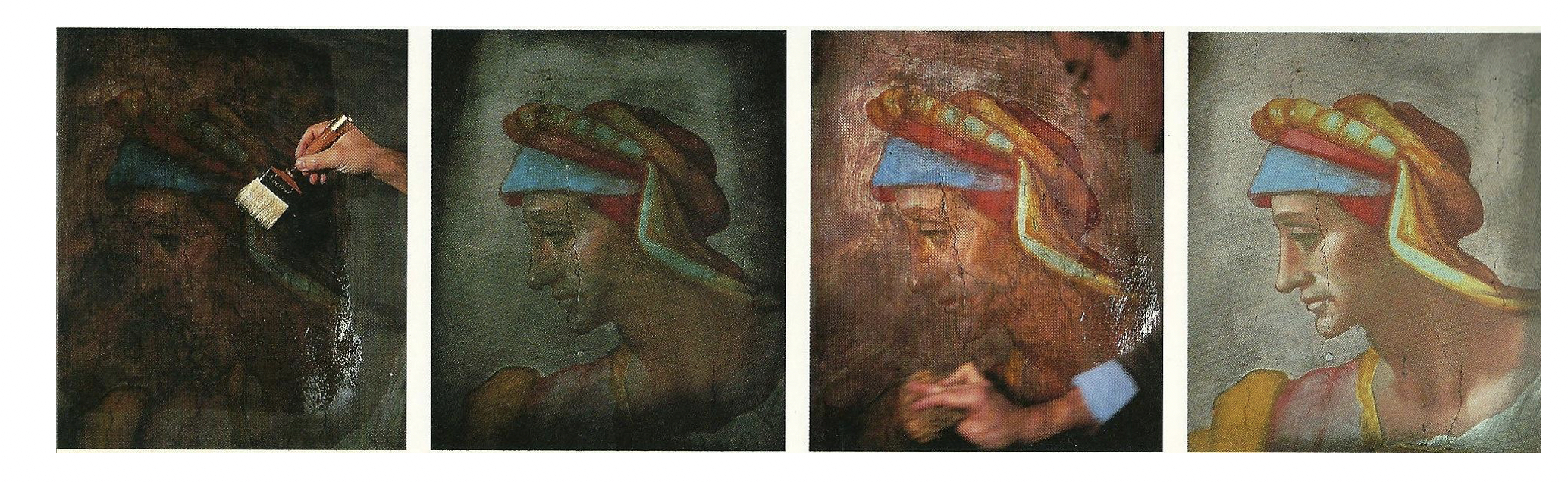

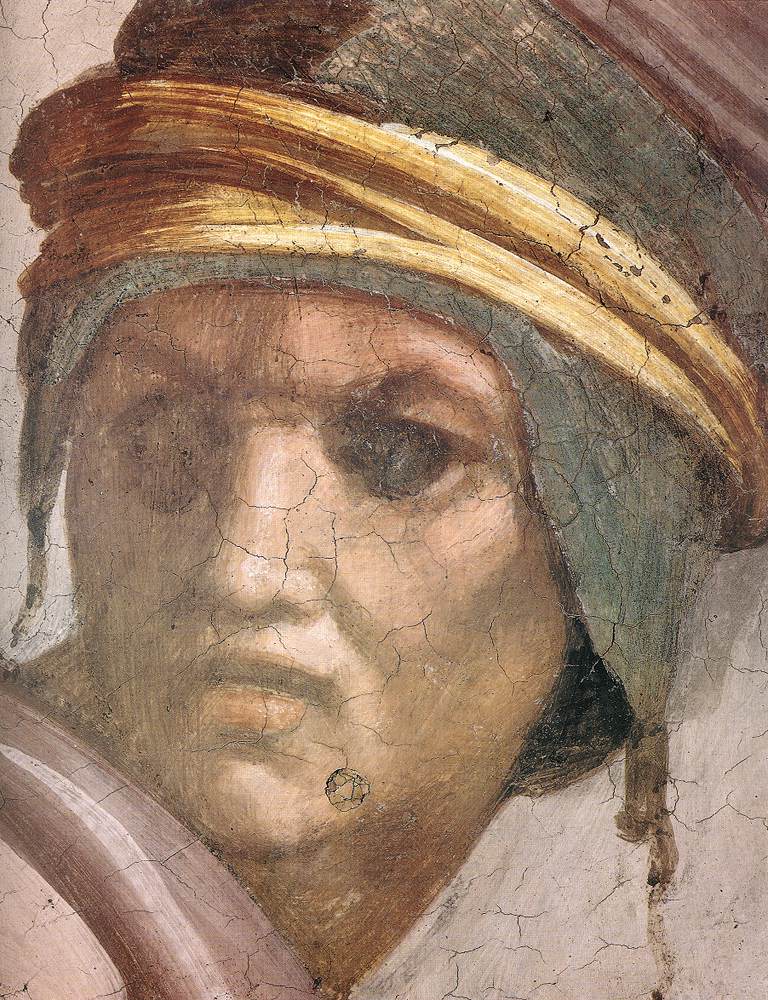

The filth was very, very thick; and it took the four stages shown in the composite image in fig. 28, before the head of Azor’s wife stood revealed in all the glory of the head-dress you see in fig. 29.

It now seems obvious, though it did not before, that the first important variable was simply colour: in profusion, in varying combinations; colours that are often intense and acid, and used instead of tones to model the lights and shadows. There are five distinct colours in the headdress alone! Similarly, in the clothes worn by Peninah (fig. 30) there are four strong colours.

Nor are the men any less brilliant. Josaphat (fig. 31) has the most wonderful cloak, in yellowy-green and orangey-scarlet, over his white ‘track-suit’ trousers; while Joseph’s youthful grandfather Matthan (fig. 32) poses like a model to show off his finery: a splendid red cloak with ochre lining over his brilliant hose:

This is one of the cases where art-historians are still arguing over whether Michelangelo intended these colours to represent a fabric made of shot silk, or whether he was simply modelling in relief by using different colours instead of darker and lighter tones of the same hue. He may be doing both, as seems to be the case with the dusky Shulamite in the lunette alongside:

In the eight triangular spandrels, the limitations imposed by the shape are so extreme that Michelangelo invariably shows a family resting on the ground (as you see in fig. 34), finding inspiration in Holy Families such as the moving panel in the National Gallery (fig. 35) by his contemporary Fra Bartolomeo: the fathers are usually like Joseph, the mothers like Mary:

By contrast, in the last pair to survive at the West End (fig. 38 and fig. 39)—imagine these facing each other—he eliminated the children altogether, showing instead young couples, the wife nearer the altar in each case, adorning herself or contemplating herself in the mirror, facing the same way in profile, or both looking out to the front:

The basic pattern determined by the half crescent seems to be that of the couples seated back to back, as in fig. 40.

In this case, they look in opposite directions—he, Manasses is deep in sleep; she is attending to two children at once (you can see her rocking the cradle with her foot). However, opposite this couple (fig. 41), Abiud and his wife hold one child each, and both turn their heads to look at some common point in the chapel:

Next to Manasses, meanwhile (fig. 42), Jechonias twists in order to seek reassurance in his wife’s gaze, while she looks sideways towards him as far as she is able to do so, and the two naked children reach out their arms to each other.

That is all there is room to show and say regarding the wonderful variety of ‘attitiduni’, and I move on now to the almost infinite expressive resources of the human face—beginning with some of the fathers whose names are the only ones to be recorded.

Side by side, in the first two lunettes at the east end of the south Wall, Michelangelo makes a contrast of age in Abiud and Achim—Abiud having one of the most alert among the younger faces, and Achim being one of the most inward or prophetic of the elder men. In their cases, the artist had absolutely nothing in the rest of the Bible to help him in his characterisation; but you may well feel that in the case of David (fig. 45), he is imagining the author of Psalm 50, or the father mourning Absalom in the tower above the gate:

In the case of Boaz (fig. 46), the debt to the Bible is clear, but the mood of the image is very different from what we might have expected:

Boaz is certainly not a pilgrim in the Book of Ruth: but he is shown him with water-bottle, staff, and a sunhat on his back. And although his extreme old age is central to the story, Michelangelo mocks him gently by making him tug out his long grey beard, while staring hard at the head carved on the handle of his staff, which juts out its forked beard back at him (cf. detail in fig. 47):

You may or may not think the humour increased by the suggestion that both heads are caricatures of Michelangelo’s formidable patron, Pope Julius II.

Having mentioned two cases where Michelangelo found inspiration in the Old Testament, I must stress, however, that he is just as inventive and fanciful when he has nothing to go on—as in the two portrait heads placed side by side in figs. 48, 49 (but, in reality, diagonally opposite each other at the extreme ends of the chapel):

Young Aminadab has the most saucy ear-rings (each one different) and a raffish head-band over the double ‘M’s of his forehead and brows and the down-turned upper lip of his open mouth. Meanwhile, the lower part of Azor’s bearded face is hidden by his hand, so that we register with all the greater pleasure the thinning hair over the forehead (wonderful brush-strokes!), which is puckered into concentric semicircles, over the huge ovoid lids of his eyes. One should always bear in mind, too, that in Michelangelo’s art, a back or torso is often more expressive than a face (as you can confirm in the detail of Manasses in fig. 50):

We come now to the unnamed mothers. I have already shown you Ruth and Bathsheba, so you know how Michelangelo can respond to the detail of the Old Testament stories where he has something to go on. It is worth adding, too, that he seems to respond with great feeling to women precisely as mothers (as in the case of Ruth in fig. 19, who has just removed the sleeping Obeth from her breast: you might perhaps remember that Michelangelo’s own mother died when he was six years old).

Some of the mothers of the Ancestors have the features he liked to give to his Madonnas, as is the case with Meshullameth in fig. 51 (of whom the Bible tells us only the name), with her pointed chin and downward, contemplative gaze.

He knows that not all mothers are young, though, and he is always aware of how much energy is required to look after and amuse young children. So perhaps the most moving face among all the mothers is the wife of Jehosaphat (fig. 52) who is holding off the attack of the youngest child, allowing number two to return to the breast, while putting her arm round the eldest, presumably Joram.

It is time to come back to Josquin now, and to the singing of music in the chapel. What you see in fig. 53 is a service in progress in the Chapel some seventy years later in 1578 (with Michelangelo’s Last Judgement now dominating the altar wall at the West End). Notice how the congregation is gathered on the near side of the screen, at the East End, and that the choir singing in front of the cantoria, which is visible on the right.

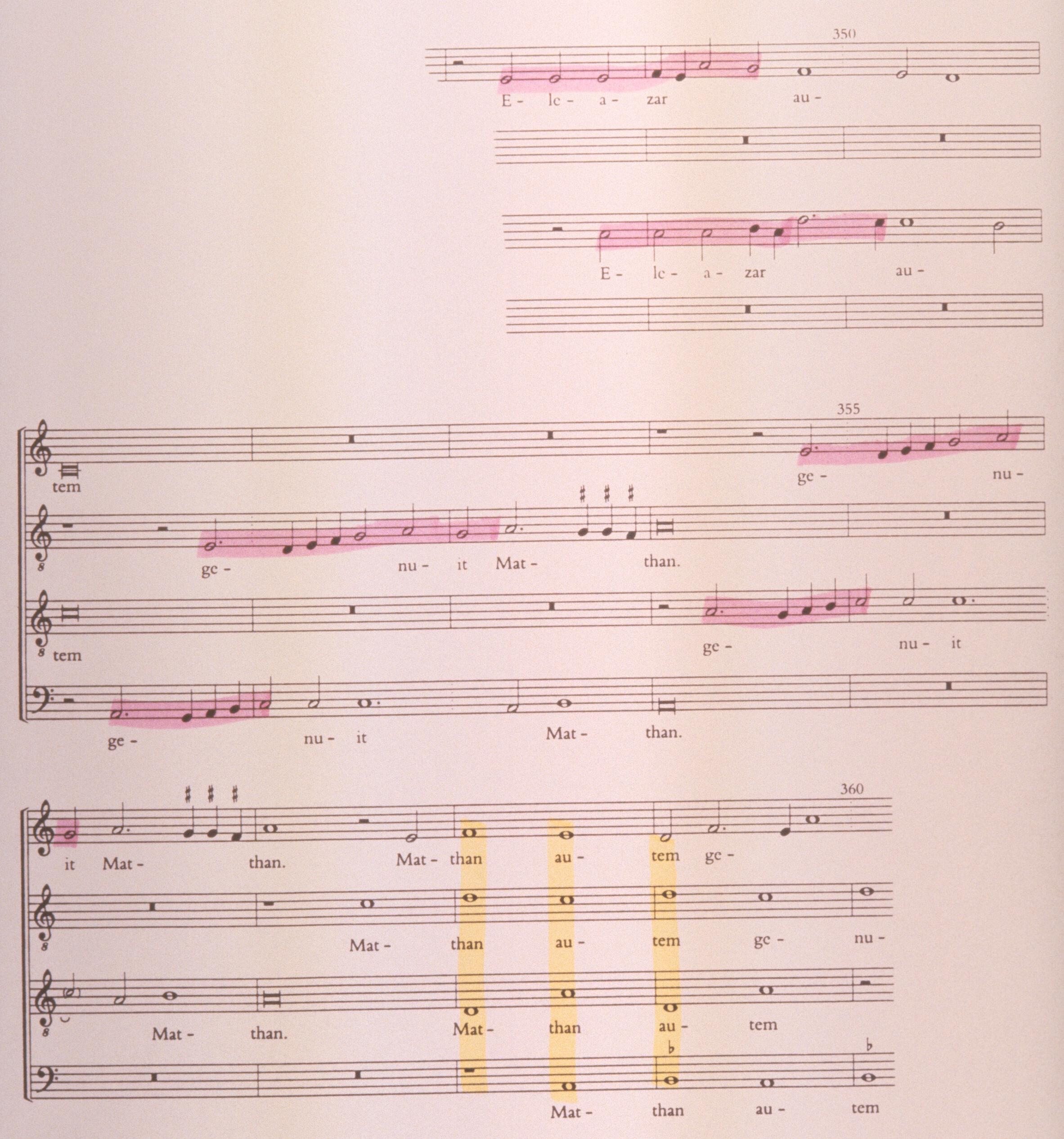

Josquin set to music the ‘Genealogy of Christ according to St Matthew’ in a motet called Liber generationis (in all probability before he came to the Chapel in the 1490s; although you may recall that his motet was copied out into a chapel choirbook in around 1510). It is divided into three parts—the divisions coinciding with those indicated in the Gospel itself—and you will find your way into the music readily enough if you are familiar with choral works from later in the century.

It is written for four voices in ‘imitative polyphony’, which means, very roughly, that for each new clause in the prose text of a motet, there is a new musical phrase, with a distinctive ‘head’, suggested by the shape of the opening words. This is introduced by one voice, and imitated at different pitches by the other voices entering in turn, all tending to become independent of the leading voice in the middle of the clause, but all finding their way through proven formulae to a clear cadence at the end of the clause. In other words, Josquin is drawing on the musical language and conventions that had been elaborated in the fifteenth century (he was probably twenty years younger than Ockeghem, and forty years younger than Dufay).

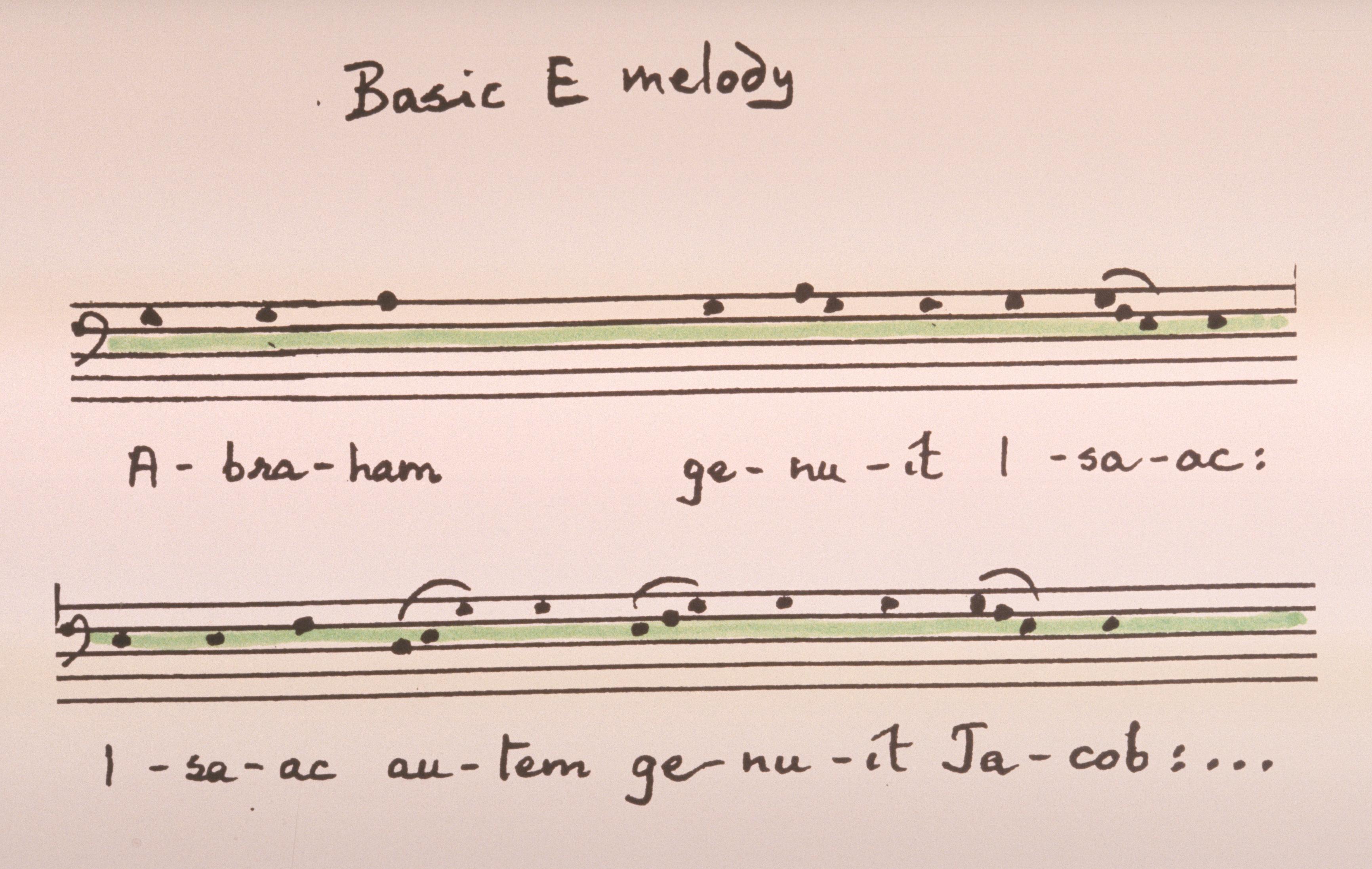

In our motet, however, he is setting himself formal constraints of a very precise kind. He is not inventing new motifs for each new phrase in the text, but drawing—in every single one of the forty phrases—on the plainchant formulae that had been used for centuries to recite the Genealogy in churches all over Western Europe. Since it is his acceptance of this incredibly restrictive formal restraint that constitutes the chief parallel with the art of Michelangelo, I think it will be helpful if I take a moment here to clarify the nature of the chant and its mode, because these determine the structure and the flavour of the motet.

It is an incredibly simple example of what you find in all psalmody, which is at the heart of Catholic liturgy. Remember that the main practical problem was how to make the words of the sacred text intelligible in a very large and resonant stone building. The solution was similar to that which a good speaker instinctively adopts when making a public announcement to a big group of people. One begins with a little rising phrase to catch their attention, delivers the message more or less at a single pitch, following the rhythm of the words (with perhaps a little twiddle to mark the commas), and then at the end of the message, one allows the voice to sink again, with another little flourish, to the pitch with which one began. (The message might be something like: ‘Ladies and Gentlemen // would you be so very kind // as to take out your mobile phones // and make sure they are switched off // so they won’t interrupt the performance. // Thank you for your cooperation’).

You can see from the heading in fig. 54 that the chant used by Josquin is in the E mode—also called the third mode, or the Phrygian. He stays unswervingly in the mode, and it was for this very quality that the motet was singled out by Glareanus. To make yourselves aware of the characteristic feel of the modes, you could do worse than try the following little experiment. Find a ‘keyboard application’ on your computer and use it to pick out the melody of the opening line of the carol Unto us a son is born, starting on middle C (use the white notes up to F and back). Now play the melody again, still starting on C, but using E flat instead of E natural. (You will get the same effect, if you start on A and use only the white notes). The difference is electrifying. In modern terminology, you have discovered the difference between a major and a minor scale.

Now tap out the rhythm and shape of the melody again—still ascending or descending by one degree at a time—but starting on E and using only the white notes on the keyboard. The difference is almost electrocuting. In sixteenth-century terminology—which we owe to Glareanus—you will have now heard the difference between the eleventh, ninth and third of the Church modes (those with their home note or ‘final’ on C, A and E). And you will have heard how much depends on whether a mode ascends (a) tone–tone–semitone, or (b) tone–semitone–tone, or (c) semitone–tone–tone.

Now let us look a little more closely at the tiny musical motif, which is repeated for every new section in the plainsong version of the Genealogy of Jesus Christ in the Gospel of Matthew, from verse 2 to verse 16 (fig. 54).

Now when the genealogy was intoned in church at Matins on Christmas Day, all forty ‘begettings’ were intoned to those two alternating patterns; but the whole chant opens with a genuine intonation for the rubric, Liber generationis.

As you can see, it opens with a falling minor third, G—E, reciting tone to final, hovers obsessively between them in the first phrase, after which it fills the interval in with an F natural (not an F sharp as in the modern E-minor scale), to make those phrases (x) and (y).

Josquin proclaims his fidelity to the chant and the mode by opening the first part of his motet with that falling minor third, successively in all voices—either at pitch, G—E, or up a fourth, A—C, which is still a minor third. You should also listen out for the opening of Part 3 of the motet, with its rising minor thirds and the voices entering in different order.

I have spent so long on the chant because it is omnipresent. At least one of the voices will state it, or paraphrase it very closely, in every one of the forty ‘variations’, and the other voices will imitate the opening recitation and flexion on the name, and weave their counterpoint out of the two motifs which I have called (x) and (y). The chant is the blood link from one generation to another.

I hope the above has made you aware of the formal limitations that Josquin accepted and clearly welcomed, and so I now turn very briefly to the main sources of variety, in that wonderful fertility of invention so much admired by Glareanus.

(FIXME: here I have inserted L45, L47 and R43, which we think are the next few cues, to work in to the text below)

LEFT

I will mention and illustrate only four variables, which you can reasonably listen out for even at a first hearing. They are as follows:

LEFT & RIGHT

- The number of voices: far from writing for four voices all the time, there are frequent duos becoming duos, and further variety in their combinations, higher and lower.

- Canonic writing: the imitative head-phrases are frequently extended to become brief two- or three-part canons, again further varied by the intervals (unison, third, fifth), and the distance between the first two entries.

- Homophony: most of the time the voices are singing the same words at different times and in different rhythms (with the upper voices sometimes becoming very free and fast moving), but sometimes all the voices come together in chordal writing, homophony, with each singing the same syllable on a note of equal length.

- Changes in metre: ginally, listen out in Part 3 to the switch from the standard common time to triple time and back again.

FIXME: (also search for “**” and “00”).

- - - lecture end - - -

left over bits from the radical surgery needed to adapt to the page!

- and in about ten minutes time, we are going to hear it sung from an unpublished transcription of that manuscript made by Jeffrey Dean, who is here with us tonight.

- Supposing I did not have the gadgetry of this lecture theatre, and I wanted to make an important announcement to all 400 people here tonight. I would begin by calling out ‘Ladies and Gentlemen’, but using a little rising phrase to catch your attention. Then I would deliver my messsage more or less on one note, following the rhythm of the words, allowing myself a little twiddle to mark the commas, until at the end of the message I would allow my voice to drop back, with another little flourish, to the note with which I began. The shape will always be something like what I have indicated in heightened neumes below: up, along with a twitch, and down:

‘Ladies and Gentlemen, Would you please be so ki-i-nd as to switch off your mobile tel-e- phones. Thank you for your co-operation’.

So: INTONATION, RECITATION, WITH FLEXA, AND TERMINATION.

- I will ask the choir to come forward now, while I explain what is going to happen. They will sing part 1, and as they sing I shall project slides showing you where we have got to, while on the other screen I will project the corresponding image from Michelangelo.

LEFT and RIGHT

In the middle of the slide, I have put in each case a brief description of the ‘attitudes’, so that you think of the variety; and at the bottom, I have put an equally brief description of what to listen out for if you want to take in the variety in the music.

RIGHT

Here I abbreviate the names of the voices to S, A T and B; but understand these as referring to the Latin names in the MS, in reality they are Alto, Tenor, Baritone and Bass.

There was not time to rehearse the second part of the motet, but I have asked Reuben and Simon to step forth and give us the chant, for the missing names, nice and slowly, so that I can continue to show you all the images in order and put up a brief description as here:

LEFT

Notice that the names are given in Latin, in the form in which they are spelt by Michelangelo on the wall, and I underline the name which is being illustrated, always assuming that I do not get out of synchrony—and that is a high risk, because Josquin is making a point about the unbroken chain of generation, by letting one voice begin new clause before the others have finished.

I do not suppose any of you will want to try and take in everything at the first hearing, but I have given you a choice. You can shut your ears and look at the right hand screen; or shut your eyes to all but the names on the left, while you let the music overwhelm you, enjoying its sad Phrygian harmony and its magnam maiestatem, and the hypnotic presence of the chant motifs. Or you can try, in one second, to read the indications of the variety in either the music or the frescos.

But whatever you do, let it blow your minds.

Passages cut by Pat in first revision, 27 July 2015–07-27

The shape will always be something like what I have indicated in heightened neumes below [check]: up, along with a twitch, and down. So: intonation, recitation with flexa, and termination. Not surprisingly, the dominant, higher note is called the ‘reciting’ tone, the last note is called the ‘final’.

and I can quickly make you aware of how important this is by singing you a snatch of a very familiar tune (is this in fact the image we have below?) in a very unfamiliar notation, so you might not recognise it straight away.

In this notation, only the spaces, not the lines, mark the different degrees of the mode or scale; and I use numbers instead of crotchets to reinforce the idea of degree, and to make the point that the tune begins and ends with the all-important ‘final’, called 1—which I pick out in in colour—dipping below it twice, and not straying far above it.

If I ask Graham to play the melody, starting on C, and using only the white notes of the piano, we get the following. But if he starts the melody on E, still keeping to the white notes, the result is hauntingly, plaintively different. The interval between the seventh degree and the final is now a whole tone instead of a semitone, and the interval between 1 and 2 is a semitone, instead of a tone; and so the interval between 1 and 3 is not a major third, but a minor third, exactly as it is in our modern minor scale. It is absolutely crucial where the semitones come in the chain.

- - -