Handel’s Partenope

A headline in the Times, around the time I first delivered this lecture, declared that “The hottest new trend is towards opera older than Mozart”. A worldly reader may have found this no surprise, but it was not always so; one of the biggest obstacles to the enjoyment of the music of Handel has been the librettos, the texts. Watching a Handel opera was rather like being shown a recording of a TV programme by a friend, who used a mixture of the ‘Fast Forward’ button and the ‘Pause’ button. The spectacle seemed to consist of rapid passages of unintelligible recitative, in which battles were won and people fell in and out of love with total strangers, interrupted by arias, where the singer expressed his or her feelings in response to the new situation, repeating the same words over and over again for four or five minutes while the action remained stationary.

Even in more times, when a Handel scholar like Winton Dean gave a talk on an opera like Orlando, he was implicitly apologising for the complex plots and the da capo arias, and praising the scenes or musical sequences in which Handel was looking forward to the 19th and 20th centuries.

My sole qualification I have for speaking on this subject—apart from loving Handel, having listened to his music for 45 years and his operas for a good 20—is that I can read Italian quite well, and look at a libretto as Handel would have done when he was casting around for a good subject in the difficult years after the collapse of his first company in London and the unexpected success of The Beggar’s Opera in 1729.

Hence I will approach the music through the words, through the libretto, through all the maligned complexities of the plot and the all-too-static songs; and I will divide my talk into three sections: the first on the story, the second on the language of the arias, and the third, much shorter, on the ways in which the music can transcend the words. And it is more of a talk than a lecture, more of a bozzetto or rough sketch than a finished painting.

Much of what I say about the libretto of Partenope, and the spirit in which I approach it, is going to be valid mutatis mutandis for any of Handel’s Italian operas; but if this lecture achieve nothing else, I hope it will compel you to buy the existing recording, recorded in 1979, but still available on CD.

So let us start thinking about the plot of Partenope. Most of Handel’s plots seem pretty uniformly absurd to us, and we have to make an effort of imagination to understand why ticket-buying audiences, aristocratic patrons and the composers themselves kept turning to the romans of the day (we call them chivalrous ‘romances’), as they would later turn to material drawn from romans of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century (which we call Gothic ‘novels’ and Romantick ‘novels’).

At this point, I must add that I have one additional qualification as advocate or ‘salesman’ of late seventeenth- and early eighteenth-century opera plots, which you may not expect. About twenty years ago, I developed a mad passion for the plays of Corneille, especially the almost unknown and unperformed Corneille of the second half of his career, in the 1660s. I think I am probably the only person in the UK who has read all these later plays frequently in recent years. In making general comments, I shall be thinking in particular of my favourite among Corneille’s late plays, which, like Partenope, takes its title from an eponymous heroine—Pulcheria or Pulchérie. It was called by its author a ‘comédie héroique—he seems to have invented the term—and it is ‘comic’, in the sense that it not only has a happy ending, but is very ‘funny’, while it is ‘heroic’ only in a more technical, limited sense, namely, that its characters come from the remote classical past, are all of noble birth, and speak in the Alexandrines of French tragedies.

Partenope was a Greek Queen, the mythical foundress of the city of Naples (and ‘partenopeo’ is still a posh adjective meaning Neapolitan), while Pulcheria was a Greek Empress of Byzantium in the early fifth century AD. In the play as in our opera, despite all the unnatural twists in the plot and the inevitability of that happy ending, the human types and the human emotions are observed from life and represented with considerable wit and finesse.

Before I begin the summary proper, let us look at some images, which I find one of the best ways to approach the stories and the music of the operas.

The first is a singer, portrayed in the first half of the seventeenth century

by the Neapolitan artist, Cavallino. The second is the vision of Pharoah’s lovely daughter by Handel’s slightly younger contemporary, Tiepolo (a work now in Edinburgh); the third is an Eastern queen from the classical past, again as imagined by Tiepolo—Cleopatra, with Antony. You might like to imagine Partenope as looking somwhere between these two.

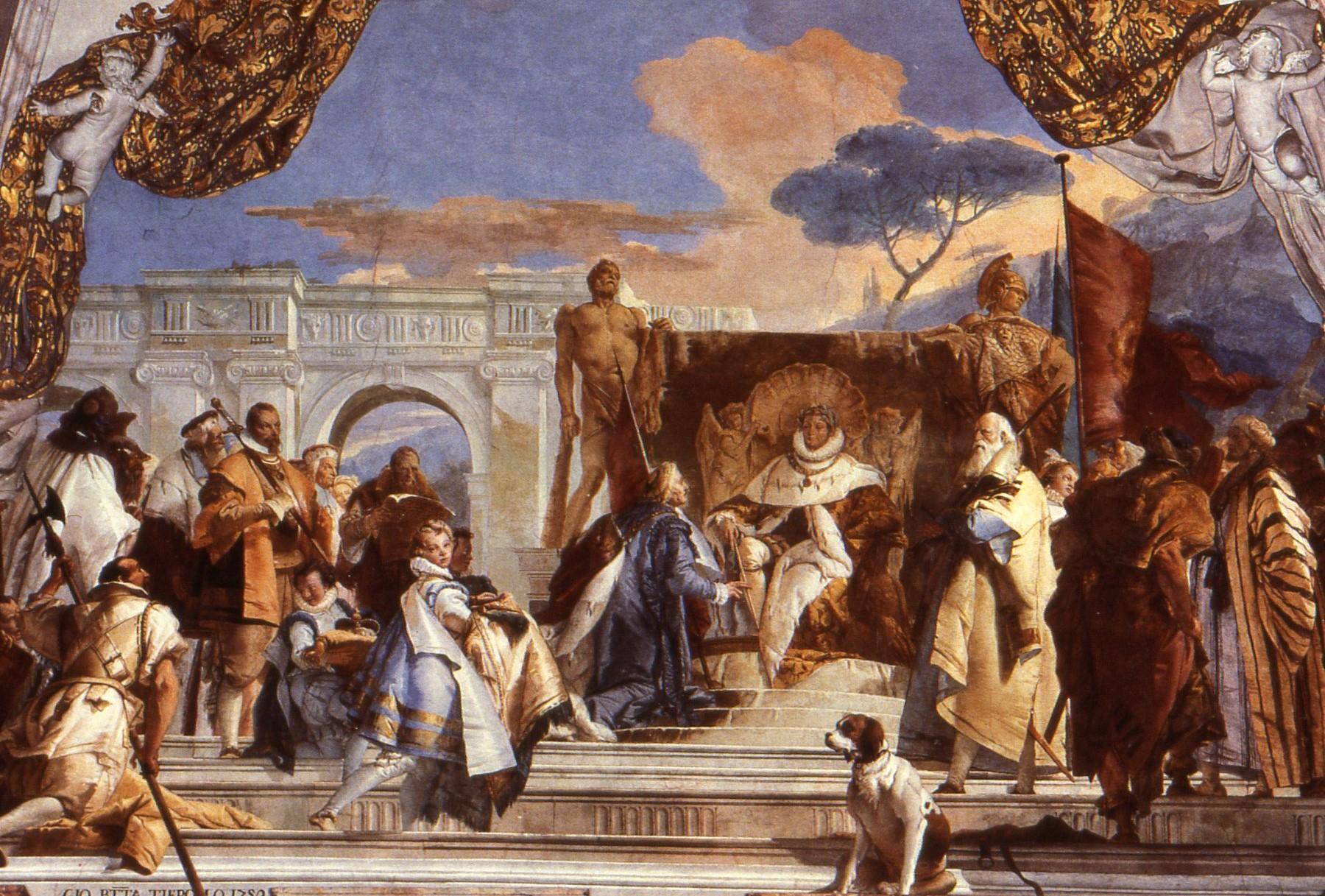

Now, two history paintings from the period, with beautiful costumes and armour, and romantic attitudes, showing how classical subjects were visualised in the 1720s and 1730s. On the left is a ceiling fresco by the Venetian Amigoni, born ten years before Handel and very popular in England, showing the meeting between Dido and Aeneas (Partenope and her new city are modelled on Dido and Carthage). On the right is an oil painting by a Neapolitan, Solimena, done in the 1720s and now in our National Gallery, showing Dido and Aeneas again, with Cupid disguised as Ascanius.

They could not be more relevant to our opera, because Partenope’s relations to her new city of Naples are modelled on Dido’s relations to Carthage. Andrew Jones tells me that he saw a recent production of Partenope which was set on a modern building site; so let this kind of scene serve as a antidote.

At last we turn to the pleasures of the plot, and the reasons why Handel chose to set it to music. It is not easy to summarise, because—as anyone knows who has ever tried to do a synopsis of an early opera—the action is so complicated that the summary is almost as long as the text itself. But I have thought up an ingenious way of taking you through all three acts without muddling you, which I hope will help you to grasp the ‘outline’: I shall describe only those events in which Partenope herself takes part, I will not reveal anything in advance which she, our ‘eponymous heroine’, does not know at the time, even though the audience gets to know a lot of other facts which are revealed either through ‘asides’ ( addressed directly to us) or through scenes where two of the other characters are on stage alone and say things which Partenope cannot hear.

As you would all expect, the characters are rather stereotyped, not much more than cardboard cutouts—‘pasteboard’, as we say—hardly more individualised than the kings and queens in a pack of playing cards. Let Partenope, then, be our ‘queen of diamonds’.The first act introduces us to her at the ‘topping out ceremony’ for her new city, nea-polis, Naples; and we meet her in the company of her established lover, Arsace, who is a very attractive man—a ‘king of hearts’.

Barely has she completed the ceremony when an Armenian prince appears on the shore, enterprising (as will appear), who shall be our ‘jack of hearts’, which in many card games is what is called a ‘wild card’. His name is Eurimene, and in no time at all he will declare himself a rival to Arsace for the Queen’s hand. The arrival of Eurimene is followed almost at once by an embassy from the local ruler, Emilio, the Italian prince of Cumae, well represented by the ‘king of clubs’.

His subjects want him to drive out this new ‘colonial power’, but he is already in love with Partenope, and while he pretends he wants to win her by force of arms if necessary, he is really willing to throw himself at her feet. So now she has three lovers.

The first scene is grand and public, set on the shore of the bay of Naples, but the next is intimate, a room in the palace. Here we meet Armindo, young, ‘pale and wan’, well represented by the ‘jack of diamonds’ in our pack. He is secretly in love with the queen, as she knows perfectly well when she teases him, but although she is flattered, she takes the first opportunity to renew her protestation of love to Arsace, in a brief, enchanting duet. What they are really saying is ‘Je t’aime moi non plus’.

Trouble begins when Eurimene appears, declares himself in love with the queen, and starts casting aspersions on Arsace; but Partenope again asserts her love for Arsace—perhaps protesting too much—in her second aria. The action then passes to a state room, of the sort Tiepolo had imagined:

Emilio first declares war, and then declares himself ‘conquered’—but his declaration of war is accepted, and his declaration of love rejected. When Partenope announces that Arsace is to be commander in chief, there is a row between him and the other two local rivals, in which the newcomer Eurimene again charges Arsace with untrustworthiness. So Partenope assumes command of her army herself in the sprightly third aria.

Act two opens with some typically military battle music, while fights and rescues take place on stage. Emilio is taken prisoner, set free, but refuses his liberty. The rivals continue to quarrel, and the sequence ends with a lovely aria by Partenope,

addressed to the ‘Dear Walls’ of the city she has just completed. Again in a public place, there is more puzzling behaviour from the rivals—Eurimene seems to be taking Armindo’s part, before starting another furious row with Arsace, in which Arsace again refuses to respond to his provocation, including a challenge to a duel. This scene ends with Partenope dismissing Eurimene under guard, while singing a splendid aria once again asserting on her love for Arsace, but again rather too insistently, as if only in order to annoy Eurimene.

Further baffling behaviour follows, when the injured Arsace now pleads on behalf of Eurimene, but when the Queen is left alone, Armindo enters, and this time her teasing makes him reveal that she is indeed the woman he loves. For the third and last time she sings of her unquenchable love for Arsace, in the aria Qual farfalletta –

like a butterfly, whirling round the flame.

Act three opens in the same garden in the palace. Partenope is now puzzled to find Armindo intervening on behalf of Eurimene. He is allowed back into her presence, renews the challenge to Arsace, and explains he is acting as champion for a lady called Rosmira, whom Arsace ‘dumped’ in order to court Partenope. Arsace admits the charge, and Partenope breaks off their engagement, speaking alternately words of love to Armindo, and of dismissal to Arsace.

The remainder of the act revolves around the arrangements for the public duel between Eurimene and Arsace. From Partenope’s point of view—to which we have limited ourselves—the most important scene is one in which she witnesses Arsace, lying on the ground, apparently talking in his sleep, with Eurimene standing over him, whom he apparently mistakes for Rosmira, and goes on refusing to fight.

And so to the lists, in a great final scene which has to be staged and seen to have its fullest effect. It suffices to say here that the climax comes when Arsace, who has been refusing to take part, suddenly agrees on condition that both of them shall fight without breastplates, and at this point it is Eurimene’s turn to show fear or reluctance, because he is none other than Rosmira herself in disguise. Partenope’s final aria concerns the inseparability of the pains and pleasures of Love, while all ends happily—with marriages between the queen and her inferior, the jack of diamonds (the successful suitor had to be of the same suit), and between the king of hearts and his true queen, while Emilio is allowed to depart as a brotherly friend.

At this point, I must remind you that my synopsis is written entirely from the point of view of Partenope, and leaves a great deal out: Arsace knows who Rosmira is from the beginning, and so of course do the audience. His public humiliations are due to the fact that he promised not to reveal her identity, and she, not Partenope, is the real heroine of the piece, the spunky girl, the ‘Sweet Polly Oliver’, who goes out and wins her man back again.

Other versions of Stampiglia’s libretto, set by another composer, have the title Faithful Rosmira; and if she is the most attractive character, Arsace, torn between the two women, vacillating, is the most interesting, the most like us, and the one whom Handel redeems with his finest music. But I hope my way of presenting the plot—in synopsis, with paintings from the period, not to mention the playing cards—has put you in the right frame of mind to appreciate some of the charms of ‘heroic comedy’, ‘comédie héroique’, when it is well written and well constructed. And in particular, I hope it helps you see the consonances between the working out of the plot and the working out of the musical forms, with their regular phrases, cadences and harmonic progressions, but their contrasting keys and metres and speeds, and their constant approximation to the dance or the fughetta.

I come now to the second aspect of the relationship between the words and the music—the language of the arias, and especially the way in which their metres and rhythms ‘influence’, or ‘give hints or opportunities’ to the composer. There are 32 arias in all in the opera, divided between the singers in accordance with a strict hierarchy: ten to the counter tenor (Arsace), eight to the coloratura soprano (Partenope), seven to the dramatic actress soprano (Rosmira), and only seven for the minor roles.

What strikes me about them—as someone accustomed to the verse forms

you find in Italian literature of the Renaissance and Baroque in narrative poems, lyric poetry, or verse drama—is threefold.

First, their brevity; they are often no more than four or six lines, many of which are extremely short, so that aria one and aria three, for example, each consists of just twenty-four syllables. The second striking thing is the number of different types of line. Italian lines are distinguished and named by the number of syllables they contain, and the opening arias, for instance, have lines of seven, ten, seven again, eight, then seven with a five. The third thing is the number of verses that end with a stressed syllable, what the Italians call ‘truncated’ lines, versi tronchi, because the final weak syllable has been ‘cut off’.

The result of these factors is that even with such simple and short stanzas, there is a great variety of metres, if you take into account the number of syllables in the line, the number of lines in the stanza and the rhyme schemes (including the presence or absence of versi tronchi). If one groups the arias by metre, you can see that there at least twenty different patterns in the thirty-two.

In a moment we are going to consider how far the pre-existent shape of the words of the aria—written by librettists who knew the musical forms of the day, and who knew the kind of variety a composer would want—help to determine the choice of the musical metre, and how far the metrical form may have persuaded the composer to choose one of the standard dance forms, the kind that composers used in suites for harpsichord or orchestra.

But before we go into any detail about the metre, let us not forget that the first duty of a writer of lyrics for songs is to give the composer one or two key words, which will suggests the speed, key and mood of the piece, and perhaps allow opportunities for word painting of the kind that was developed by Italian madrigalists in the second half of the sixteenth century, and had not lost all its attractions for composers in the first half of the eighteenth. We can find two examples of this in arias by Emilio and Armindo:

(Emilio to Partenope)

Anch’io pugnar saprò

armato di valor,

ma non di sdegno.

E vincer tenterò

sol del tuo regio amor

per farmi degno.

(Armindo to himself)

Voglio dire al mio tesoro

ch’io sospiro, piango e moro,

e che bramo almen pietà.

(Partenope, Act I Scene X)

In the first, Emilio is addressing Partenope towards the end of Act One, and the key words are pugnare, ‘to fight’, and armato, ‘armed’—‘armed with courage not disdain’. In the second, Armindo, left alone, tries to psyche himself up to tell his ‘treasure’ that he ‘sighs, weeps and dies’, and you can hear not only the sad mood of the piece, but the madrigalisms on sospiro. I should add, however, that although there are other examples of response to individual words—Partenope’s ‘farfalletta’ and its ‘girare’ for instance—Handel does not indulge himself in this respect; in fact he is positively parsimonious.

I return now to the metres of the arias. It is a fact not always appreciated by amateurs of Italian versification that the individual lines are not distinguished simply by the number of syllables, but by their rhythm. Certain lines are almost always ‘binary’ in rhythm (in classical or English terms, iambic or trochaic), while others, notably the lines with six, eight and ten lines (senari, ottonari and decasillabi) are ternary, or, if you prefer, dactylic or anapaestic.

Could it therefore be that the metre of the words has an influence on the choice of common time or triple time? There is some evidence that they do—but even more evidence that they do not! To further explore this, we will turn to the music of Rosmira.

Rosmira (or Eurimene) is given a song in praise of hunting, where the meaning of the opening words—‘Proud and alone I follow the beasts in the woods’—tells the composer to bring in horns and oboes, while the ternary rhythm of the senari points towards the triplets of a giga. However, the same metre, senari, in another context—where Rosmira admits to still loving Arsace’s face, but to fearing (the inconstancy of) his heart—is set to a 3/8 of a totally different kind.

I now move on to two of her other arias in a different metre, settenari tronchi:

Un’altra volta ancor,

mi promettesti amor,

poi m’ingannasti

Settinari tronchi (2) + quinario, 4/4, allegro

(Partenope, Act I Scene V)

Arsace, oh Dio! così

infido l’ingannò

Settinari tronchi, 12/8, larghetto (siciliano)

(Partenope, Act III Scene II)

The first is in common time, allegro, but the second—in which she is telling Partenope that ‘Arsace, alas, the unfaithful, deceived Rosmira like this’—is set to a lovely siciliano in 12/8.

It is worth noticing that the arias set to established dance metres are all those with simple regular stanzas: in other words, the librettist can nudge the composer in that direction by his choice of metres. And it is also worth noting that there is a strong possibility that Handel will be less constrained, more inventive, in his melodies and phrasing and accompaniments where the verse is less regular and predictable.

One last example, still from Rosmira’s arias, illustrates this point:

Furie son dell’alma mia

gelosia,

rabbia e furor

Ottonario + quaternario + quinario tronco, 3/4, allegro

(Partenope, Act II Scene V)

The key word is ‘Furies’, subdivided into ‘jealousy, rage, and anger’. The lines are all of different length, and Handel chooses not the beguiling lilt of the siciliano, but three equal blows on ‘Fu-rie-son’.

So now I come to my promised final section, and a few examples of the way in which the words don’t seem to matter at all; examples of the way in which Handel can transform any words he is given into something that they themselves do not suggest: neither by their meaning, nor rhythmical arrangement, nor by their quality, nor by their psychological finesse. To my ear, virtually all of Arsace’s music has this extra quality which transforms him from a two-dimensional ‘playing card’ into a moderately complex and at times well rounded character.

So to end, we will focus on three arias from the castrato. In each of these arias he is addressing Rosmira; in the first, he asks her in three settenari if she is always going to be so fierce and scornful (when he has indicated he is really still in love with her), and she, in a final quinario, goes on calling him a ‘faithless ingrate’:

Arsace

E vuoi con dure tempre

di fiero sdegno armato

così schernirmi sempre?

Rosmira

(Infido, ingrato!)

(Partenope, Act II Scene IV)

In the next act, he is still reproaching her for needlessly continuing to torment him:

Rosmira

Sei cagion del tuo mal. Parti! ch’io resto.

…

She tells him ‘you are the cause of your own sufferings, leave, because I am staying put’. He replies (with a nice, Petrarchan conceit):

…

Arsace

Ch’io parta? Sì, crudele,

parto, ma senza cor;

ché nel mio sen fedele

nel luogo ov’era il cor,

è il mio dolor.

(Partenope, Act III Scene IV)

Handel transforms the poetic cliché, in a largo with a strong suspicion of the sarabande, into something quite magical. However, the most surprising music in the whole opera comes later in the same final act, in a recitative, sinfonia, and aria.

Here, Arsace, just before the duel, sinks down to the ground in exhaustion, and falls asleep. Everything in these four minutes of music is lovely: the accompanied declamation, the sinfonia mesta, the choice of instruments, the aria itself with its ‘echoing notes of sad laments’:

Arsace

Non chiedo, o miei tormenti

che mi lasciate in pace:

sol per brevi momenti

date qualche respiro al cor d’Arsace!

Vieni, pietoso oblio,

ristora il petto mio

cadente e lasso,

e de’ riposi miei sia letto un sasso.

[S’ode una sinfonia mesta]

Ma quai note di mesti lamenti

qui d’intorno echeggiando sen vanno?

Ah! ch’al suon di querele dolenti

a dormire m’invita l’affanno.

[Si addormenta]

(Partenope, Act III Scene VI)

The music then continues, with the following accompanied recitative for Rosmira,

which is equally moving and lovely:

Rosmira ed Arsace, che dorme

Rosmira

Cieli che miro! Abbandonato e solo

dorme Arsace, il cor mio!

Dolce sembianza vaga,

almen fossi fedel, quanto sei bella.

Cruda mi chiami, e pur fedel t’adoro.

Sogno infausto, ombra ria

non funesti ‘l tuo sonno, anima mia.

(Partenope, Act III Scene VII)

She comes upon him while he is fast asleep, and can at last declare freely that he is still her ‘heart’ and her ‘soul’, wishing that he was ‘as faithful as he is good looking’, and hoping that ‘no bad dreams will disturb his sleep’. At this point we have the music of a great love story.

FIXME: Search for “???” and deal with the following:

NOTES FOR PAT

- I have left out the bozzetto and final version of the Tiepolo painting, and reduced from the original typescript what was a mea culpa for the necessarily sketched nature of the lecture.

- I have changed the phrasing of the section about Winton Dean slightly, to account for the fact that he is now pluperfect.

- I have left in the substantial paragraph on the ‘absurdity’ of Handel’s plots, though this was struck through in the paper typescript as delivered—it was unclear whether this was for reasons of time or criticism.

- On the subject of the CD, I note that as well as the 1979 recording (which is still available on Deutsche HM), there is a Chandos (CHAN0719) recording from 2005 of the Early Opera Company (which is I believe the production, performed at Buxton, that you referred to in the typescript), as well as DVD of Andreas Scholl’s 2008 performance (Decca 0743348)—we could work these into the text if you want?

- I have not reproduced the English opening lines from the slides, as it does not seem so essential to the printed edition without the accompaniment of the music; it can of course be reinstated. So too, the handout listing all 32 arias.

- Similarly, a specific reference to the arias by Emilio and Armindo would be helpful to the reader in the absence of audio.

- It was unclear to me which painting(s) were supposed to illustrate Ermania, so they have been left out for now (and again are potentially not essential).

- The English translations of Arsace which appear in the slides and at one point in the body of the text have been omitted.