The Visual Arts and Dante’s Purgatorio

This lecture is the first of the final series of open lectures

on Italian art which I gave at the University of Cambridge; a series

based around the theme of Italian Painting and Poetry, and some of the

relationships between them in a period of 200 years running from

Giotto’s frescos in the Scrovegni Chapel in Padua to Michelangelo’s

frescos in the Sistine Chapel. The poets include Petrarch and Boccaccio,

who, thanks to the invention of printing, had become even more popular

in 1510 than they had been in their lifetimes; but the lion’s share of

the poetry will fall to Dante, who will be dominant in three of the six

lectures, starting with this one.

Dante was born in 1265, and died in 1321; he composed the three parts of his Comedy, the story of his journey through Hell, Purgatory and Heaven, in the last fifteen years of his life, and he probably began work on the second cantica, Purgatorio, in about 1310. In this lecture I am going to take all my examples from Purgatorio—so much less familiar than the Inferno—for reasons that will become clear as I go along. I want to throw light on the nature of Dante’s achievement by exploring some of the parallels or similarities between his poetry and the painting and sculpture of some of the great artists who were working in Tuscany in his lifetime.

Let make two things absolutely clear before I begin. (a) I shall not talk about the possible sources of his imagery in earlier art, nor about illustrations of his poem, which obviously come later; and (b) there is no ‘argument’ to this lecture. I am not trying to prove anything, but I hope you will agree by the end, that you have seen and heard some astonishingly beautiful and moving things, and that the qualities that make Giotto a great painter are remarkably similar to the qualities that make Dante a great poet.

| Some masterpieces of Tuscan art in the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Nicola Pisano | Pulpit Pulpit |

Pisa (Battistero) Siena (Duomo) |

1260 1268 |

| Cimabue | Crucifix | Florence (S. Croce) | 1285 |

| Giotto (?) | Frescos | Assisi (Chiesa sup.) | (?) 1295 |

| Giovanni Pisano | Pulpit Pulpit |

Pistoia (S. Andrea) Pisa (Duomo) |

1301 1302–10 |

| Giotto | Frescos | Padua (Scrovegni) | 1305–10 |

| Duccio | Maestà | Siena (Duomo) | 1308–11 |

I have summarised some names and dates in the table (fig. 1), and I

shall talk you rapidly through them now, so that you have at least

something to hang on to. The oldest artist to whom I shall refer will be

Nicola Pisano, the sculptor who carved a white marble pulpit for the

Baptistry at Pisa in about 1260 (below left), as well as

another, more elaborate pulpit for the cathedral in Siena ten years

later, in about 1270. Next in chronological order comes Cimabue, a

Florentine, best known for a gigantic crucifix which he painted in the

1280s for the Franciscan Church of Santa Croce in Florence (below

right) (it was he who used to be credited with the designs for the

mosaics in the Baptistry there).

Next we have to go to Assisi, to the church which rises over the tomb

of St Francis, where a team of central Italian artists, working under an

unknown Master (even Italian art historians now accept that it was

not the youthful Giotto), painted the Life of St Francis in no

fewer than 28 scenes, from which I have reproduced a detail below

(left). From there we travel north to Padua, to a tiny red-brick

chapel whose walls are covered in three layers of narrative frescos

telling the story of Christ, and of his mother, Mary, and of his

maternal grandfather, Joachim. These were painted by the ‘real’ Giotto,

a Florentine, between about 1305 and 1308, and are pictured below

(centre), along with a detail of Joachim (right): TOM !, SOMETHING

LIKE (see fig. 2 b and 2c)

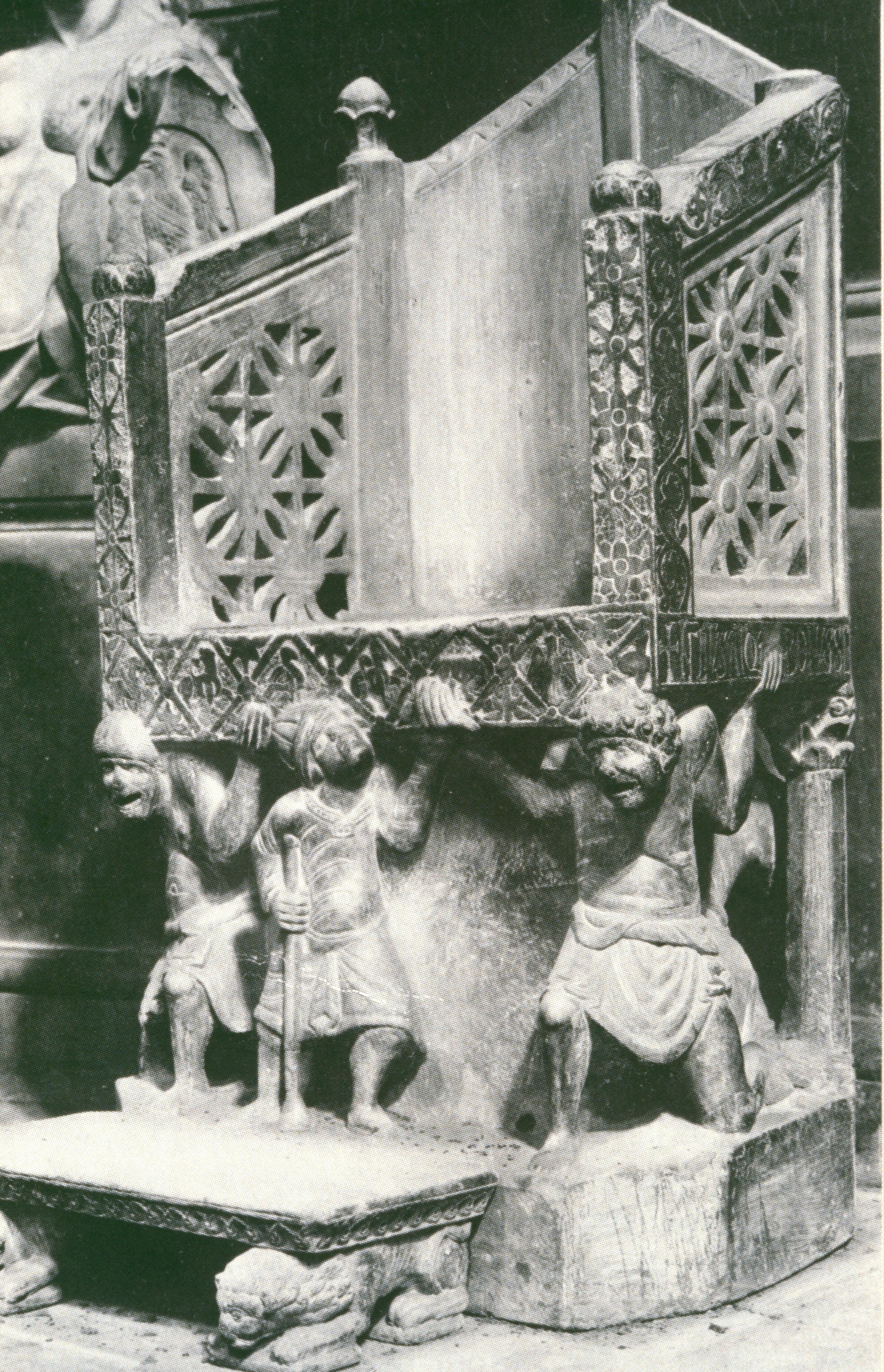

Back to Tuscany itself now, to Pistoia and to Pisa, where in the same

years, another great sculptor, Giovanni, the son of Nicola, carved two

more astonishing marble pulpits; shown below is the one in

the Cathedral at Pisa, CHECK: I REMEMBER USING THE TELAMON AT PISTOIA

HERE with its marvellous telamon. From Pisa we return to Siena where we

began, to glance at the masterpiece of Duccio, who painted both sides of

the gigantic altarpiece (below right) for the Cathedral of

his native city in 1311—on the front you see the ‘Virgin in Majesty’,

which is why the altarpiece is called simply the Maestà:

Simone, though, is better known as a friend of Petrarch, so you will see more of his work in the next lecture.

I have shown you a good many images already, but it would be more fitting, and more evocative, if it were now possible to show you total darkness, as a way of reminding you of the fundamental contrast between Inferno and Purgatorio in Dante’s poem. He represents the underworld of Hell as a ‘valley of gloom’ (‘valle buia’), filled with ‘black air’, but in the last lines of the Inferno, he tells us how he and his guide, Virgil, climbed up a narrow tunnel from the very centre of the earth, until they could ‘see the stars again’, although these were rapidly fading in the blue sky just before sunrise.

In the opening sequence of the second cantica, it becomes clear that the travellers have in fact emerged on the shores of a mountain island in the Southern ocean, which is where Dante the poet—striking out boldly on his own—chose to place the second kingdom in the Catholic afterworld; ‘that second kingdom where the human spirit is purified and becomes worthy to ascend to heaven’. Everything in this mountain kingdom, Purgatory, is totally different from the pit of Hell—as different as life is from death—and every event and scene is bathed in light and colour.

The difference is proclaimed by the narrator at the very beginning, where we read:

Dolce color d’orïental zaffiro,

che s’accoglieva nel sereno aspetto

del mezzo, puro infino al primo giro,

a li occhi miei ricominciò diletto,

tosto ch’io usci’ fuor de l’aura morta

che m’avea contristati li occhi e ’l petto.

Lo bel pianeto che d’amar conforta

faceva tutto rider l’orïente…

(Purg. 1, 13–20)

To quote Dante in another context, ‘how many things ought to be noted’ in these lines: ‘quante cose sarebbero da notare’. Notice first, then, the adjective ‘dolce’, the noun ‘diletto’, and the verb ‘ridere’—all of which allude obliquely to the first chapter of Aristotle’s Metaphysics, which opens with a vigorous affirmation of the pleasure of perception as such, and, above all, an assertion of the pleasure we take in the sense of sight.

Now, Dante had a scientific cast of mind, and he had been taught by

the natural philosophers of his day (whom today we would call

‘scientists’) that the specific objects of the sense of sight, and that

therefore the things that give pleasure when we see them, are ‘colour

and light’. In a passage in his Convivio, from which the

heading comes, In his Convivio, he had said: ‘other

things than colour and light are indeed visible, such as shape, size and

number, but not specifically (‘propiamente’), because other senses can

perceive them; whereas colour and light are specifically and exclusively

visible (‘prop(r)iamente è visibile lo colore e la luce’)’.This is

because, he continues, we can perceive them only with sight, and not

with any of the other senses. In other words, shape and size are

secondary, but colour is primary. It is colour that gives

delight. [TOM: I THINK IT MAKES SENSE IF WE REMOVE THE

STRUCK-THROUGH SENTENCE] I hope this short passage of prose is enough to

give some inkling at least of the full significance of those simple

words ‘dolce’ and ‘colore’, which provide the obvious link to the art of

painting in Dante’s time.

As is well known, colour had a pre-eminent role in medieval painting, and predominates as in no other period in Western Art. I am thinking of the manuscripts, which (to quote Dante) ‘seem to smile with the art which in Paris is called illumination’; of the most important churches, where the frescoed walls and vault are like a symphony of colour; and of the art of mosaic, neglected in Italy for many centuries, but renewed in the 1280s in the Baptistery of Florence:

And to these, we must not forget to add the huge areas of coloured light in the windows:

IMAGES x2 (the first of these I need to rescan from the box of

slides, as it seems to have slipped through the cracks; the second of

these, the Martini in Assisi, I cannot find in the slides)

The tondo above is in the Cathedral at Siena, and the

designs are by Duccio; the window is in Assisi, and is to designs by

Simone Martini.

In medieval art, we might say, as in medieval physics, colour comes first. And this leads me back to the quotation above from the opening of Purgatorio and Dante’s reference to the ‘ sweet colour of Eastern sapphire’, a colour which we find in a painting by Duccio, a lovely triptych in the National Gallery at London, from which I want to pick out a particular detail:

[TOM, THIS LIINK IS VERY LABOURED AND I MUST IMPROVE IT]

The strong and brilliant colour you’re looking at is not literally ‘sapphire’. It comes from a mineral that was almost as precious, it too being imported from the East, (‘l’Oriente’), lapis lazzuli, which at that time cost more than gold in its pure state. It is a natural colour, not synthetic, intense, saturated, pure with no admixture, brilliant, resistant. These are qualities that make me thing of another passage in Purgatorio, where Dante describes the intense colours of the flowers in a little valley on the lower slopes of the mountain:

Oro e argento fine, cocco e biacca,

indaco, legno lucido e sereno,

fresco smeraldo in l’ora che si fiacca,

da l’erba e da li fior, dentr’ a quel seno

posti, ciascun saria di color vinto,

come dal suo maggiore è vinto il meno.

Non avea pur natura ivi dipinto…

(Purg. 7, 73–9)

‘Cocco’ was red, ‘biacca’ was white, ‘indaco’, is our indigo, a deep blue; ‘legno lucido e sereno’ is said to be yellow, while ‘smeraldo’ is emerald. Yet the substances you are invited to imagine, says Dante, would have been surpassed in intensity by the colours provided by God; and the inference is that God too takes delight in colours, the brightest and sharpest possible.

I would now like you to look at an example of the brilliance and intensity of colours other than blue, in the art of Dante’s time:

This little panel above (left) is by Ugolino di Nerio, a pupil of Duccio, and it is also in our National Gallery. It was painted in the early 1320s, shortly after Dante’s death, and it was part of the predella of the altarpiece in Santa Croce in Florence. Alongside it I have placed a detail (right) in which the colours have been digitally enhanced to bring them back to something like the state in which they would have been 700 years ago.

Look at the gold, ‘il cocco’, ‘la biacca’, ‘il dolce colore dello zaffiro’, ‘lo smeraldo’—and let’s close in to see the same colours on the feet:

Gold, white, scarlet, sapphire, emerald—these are what Dante and his contemporaries expected from a painting!

In order to draw together all the points I’ve made so far about the role of colour in medieval art, and about Dante’s own way of conceptualising colour, I would like to focus for a moment on the first stanza of a lyric poem by Dante.

Amor, che movi tua vertù dal cielo

come ’l sol lo splendore.

…

sanza te è distrutto

quanto avemo in potenzia di ben fare,

come pintura in tenebrosa parte,

che non sì puo mostrare

né dar diletto di color né d’arte.

(Rime XC, 1–2, 11–15)

This lovely canzone is a hymn to Love, Amore, understood

here as a cosmic force, or a divine power, ‘which sends its energy from

heaven, just as the sun sends its splendour’. The italicisations remind

you of words and concepts present in the lines from canto 1 of the

Purgatorio already quoted; but this passage makes explicit the

other connections I have been suggesting, thanks to the final simile of

a painting (‘pintura’ is modern Italian ‘pittura’) which has been placed

‘in a dark place’, thereby becoming almost invisible, and unable to

fulfil its purpose—its ‘raison d’être’—which is that of giving the

‘delight of colour and art’. For Dante, I would argue, the two

telescoped phrases, ‘diletto di colore’ and ‘diletto d’arte’, are almost

a hendiadys, two ways of saying the same thing. [NOT QUITE

RIGHT YET]

Think back to Duccio’s Madonna, while I make a few simple points about the symbolism of colour in the art of Dante’s time. According to the medieval encyclopaedias, the sapphire had various powers—or, as they then said, various ‘virtues’—some of which are highly relevant to the situation of Dante the pilgrim at the beginning of his ascent of Purgatory. A sapphire (so we are told) can ‘set prisoners free from prison’ (Dante has emerged from Hell, which he called a ‘blind prison’, ‘cieco carcere’). A sapphire can purify or ‘clean the eyes’ (symbolically, Dante’s mental vision must now be made ‘pure’). It can also ‘appease God’s anger’ (placatum reddit Deum), which is what all sinners hope to do through repentance and acts of penance.

Blue—the colour of the sky and of heaven—was the colour associated par excellence with the Virgin Mary, whom Dante will later describe, in a daring phrase, as the ‘fair sapphire with which the brightest heaven is ensapphired’. You must remember that the whole of the second cantica is pervaded by the spirit and example of Mary, who, we are told, ‘opened the road between earth and heaven’, the road which Dante must now take. Her virtues are recalled on each of the seven terraces of the mountain of Purgatory. She is the star of the blue element, the ‘star of the sea’ (stella maris). In paintings, her face is often sad and full of foreboding, but always ‘dolce’.

Look at this detail of her face Duccio’s image, and think of the words in Dante’s final hymn to Mary in Paradiso 33:

Tu se’ colei che l’umana natura

nobilitasti sì, che ’l suo fattore

non disdegnò di farsi sua fattura.

(Paradiso 33, 4–6)

***************************

I have been making broad generalisations up to this point, but obviously it is not correct to speak about colour—or any other aspect of painting—in the late thirteenth and early fourteenth century as though they were universal and unchanging, the same in every decade, in every centre, or in every artist throughout his career. To substantiate this point, I had planned to talk about the changes in the style of Nicola Pisano, who, without rejecting the Romanesque style as found in Northern Italy in the 1250s, could pass from imitation of classical sarcophagi this panel from his Pisan pulpit in about 1260 (below left), to an assimilation of the very latest Gothic Style from France, in his version of the same scene, the Adoration of the Magi, in this pulpit in Siena in 1270 (below right):

I was also going to draw a parallel between Nicola and Dante, by looking at Dante’s re-creation, in various parts of the Inferno, of his successive stylistic experiments in the poems of the 1290s; vastly different experiments in the colloquial, vulgar style, in the harsh and grating style, and in the noble, Virgilian style. The Divine Comedy has been described as a summa stilistica. On the morning of giving this lecture, I decided that all this would take too long to explain properly—but I could not resist touching upon it, and so I gave my audience only the conclusion, which follows.

In the Purgatorio—but not in the Inferno—Dante often recreates the mood and language of the love poetry that he had composed, back in the 1280s; of the poems in praise of Beatrice, which he had gathered together in his Vita nuova, the style he would define as the ‘sweet new style’, ‘il dolce stil novo’.

I recall for you below one central motif in this praise style (in the Vita nuova, he called it ‘lo stilo della loda’):

Di donne io vidi una gentile schiera

questo Ognissanti prossimo passato,

e una ne venia quasi imprimiera…

(Rime LXIX, 1–3)Tanto gentile e tanto onesta pare

la donna mia quand’ella altrui saluta,

ch’ogne lingua deven tremando muta,

e li occhi no l’ardiscon di guardare.

Ella si va, sentendosi laudare,

benignamente d’umiltà vestuta;

e par che sia una cosa venuta

da cielo in terra a miracol mostrare.

(Vita nuova XXVI)

Namely, this is the evocation of Beatrice (‘la donna mia’) as she passes along a street of the city (‘ella si va’) at the head of a group (‘schiera’) of other young women, almost as ‘the chief among them’, ‘quasi imprimiera’, but ‘sweetly clad in humility’. It is a recurrent theme, which one feels must have been stirring in Giotto’s mind and heart when he painted the wedding procession of the Virgin in Padua:

Just look at the simple but effective ways in which the Virgin is singled out as ‘imprimiera’: the ‘caesura’ that separates her from the overlapping bodies of her companions; the slenderness of her figure; the whiteness of wedding dress; andthe elegance of the folds created by her hand as she lifts the skirt. The fresco also calls to mind the opening of another sonnet by Dante:

Vede perfettamente onne salute

chi la mia donna tra le donne vede;

…

E sua bieltate è di tanta vertute,

che nulla invidia a l’altre ne procede,

anzi le face andare seco vestute

di gentilezza, d’amore e di fede.

(Rime XXIII, 1–2, 5–8)

He perfectly sees all bliss [all salvation]

who sees my lady among the other ladies.

…

Her beauty is of such power

that no envy proceeds to the other women.

on the contrary, it makes them walk beside her clad

in nobility, love, and faith.

For me, this is one of the moments of closest contact between poetry and painting at the turn of the fourteenth century—not actually in the Purgatorio, admittedly, but conveying a mood that you will find throughout the second cantica.

It is only at this point in my exploration of the relationship between poetry and painting in Dante’s time that I turn, finally, to those famous lines, in which Dante shows that he is bang up to date, and is well aware of the parallels between his art and that of both the two Guidos (Guinizzelli and Cavalcanti), and of Cimabue and Giotto:

Oh vana gloria de l’umane posse!

…

«Credette Cimabue ne la pittura

tener lo campo, e ora ha Giotto il grido,

sì che la fama di colui è scura.

Così ha tolto l’uno a l’altro Guido

la gloria de la lingua…»

(Purg. 11, 91, 94–98)

I recall these much quoted lines rather hastily here, not to labour the obvious, but to remind art historians of the context and the speaker, which are often overlooked. We are on the first terrace of Purgatory—the circle reserved for the penitent proud—and the lines are part of a passionate sermon attacking ‘vainglory’. In context, the lines are not about progress, not about the emergence of a race of giants, but about fashion, about the arbitrary and inevitable changes of taste on the part of the public, the consumers—not about what we perceive as a decisive revolution on the part of the artists, in the way of representing reality and of reinterpreting stories from the Bible and the Lives of Saints.

I remind you that the speaker of the lines, the ‘preacher’, is a miniaturist from Umbria, name was Oderisi da Gubbio, whose ‘honour’ (show) was in fact so ephemeral that the experts have not been able to identify with certainty a single manuscript from his hand, although his style was probably similar to this miniature, which Mario Salmi attributed to his workshop:

It shows the allegorical figure of Justice, with her balances; two jousting knights, representing the parties in dispute; the antagonists, who are sardonically recalled, too, in the bear baited by the mastiff; on the arms of the balance, the non-allegorical figures citizens and jurists in contemporary costume; and, at the bottom, the lovely decorative flowers. Dante makes Oderisi speak of ‘le carte che ridono’, ‘the parchments sheets that smile’, and this is ‘una carte che ride’.

Oderisi recalls that he was eclipsed by a miniaturist called Franco from Bologna, ‘Franco Bolognese’; and here again the force of his arguments in the sermon against vainglory is borne out by the fact that we do not have a single manuscript signed by him either. His style must have been close to this image, by a Bolognese artist—anonymous, highly talented, very much open to the volumetric art of Giotto—who was the executant of one of the fullest, earliest, and best series of miniatures to Dante’s Comedy, done in the 1330s, and now in the British Library:

I have chosen this particular image because it shows Dante the pilgrim, the figure in pink, walking alongside Oderisi and the other pentient proud, who are all bend double under the weight of huge boulders that ‘tame their proud necks’. Dante specifies that he and ‘that burdened soul’ were walking along like two ‘oxen yoked together’. He had been made conscious and ashamed of his own fierce pride in his art, and of his own desire for ‘glory’—vain glory—his desire to be publically acknowledged as the greatest poet in the world. The penance that Dante chose for the souls of the proud—and for himself—is a nice example of the clear influence of the visual arts on his imagination.

It must have been inspired by the caryatids—the crouching figures serving as corbels to support a column—which are a very expressive feature of Romanesque art all over Western Europe.

Above I have shown you just one example, from the year 1098—the tormented features of the dwarves who support the bishop’s throne in the cathedral at Bari. That the inspiration did come from sculpture is guaranteed by the simile used by Dante to describe the souls of the proud, and the huge stones on their backs, when he first sees them:

Come per sostentar solaio o tetto,

per mensola talvolta una figura

si vede giugner le ginocchia al petto,

la qual fa del non ver vera rancura

nascere ’n chi la vede; così fatti

vid’io color, quando puosi ben cura.

Vero è che più e meno eran contratti

secondo ch’avien più e meno a dosso;

e qual più pazïenza avea ne li atti,

piangendo parea dicer: ‘Più non posso’.

(Purg. 10, 130–9)

The commentators suggest that Dante may have been inspired by two caryatids in particular, which used to stand in the portal of the cathedral of Civita Castellana, because underneath them is written what we would now call a ‘caption’, exactly as in a cartoon in the newspaper. The ‘caption’ is in the form of a dialogue in macaronic Latin. The first figure is saying, ‘Help me, you sod’; and the second is answering, ‘I can’t, because I dying’, ‘Non possum, quia crepo’.

The similarity with Dante’s text is obviously very striking, ‘non possum’, ‘più non posso’; but I do not think we need assume Dante was inspired by a statue with a caption underneath. There are other, and more expressive, visual counterparts for Dante’s penitent proud, in all their dignity and pathos. To find them, I would advise you to go not to Civita Castellana, but to Pistoia, to the church of St Andrew, to have a close look at the wonderful pulpit (below left) by the son of Nicola Pisano, Giovanni, where the so-called ‘Atlas’ figure, below right in close up, seems to me a perfect match for the meaning and feeling of Dante’s lines, ‘e qual più pazïenza avea ne li atti, / piangendo parea dicer: “Più non posso”’:

The figure was carved in the year in which Dante was sent into exile, 1301, and I think one can certainly say that ‘not being true, it gives birth to true anguish in any one who sees it’ (‘la qual fa del non ver, vera rancura / nascere in chi la vede’).

I shall turn now to Dante’s similes—not so much the ones he imitated from Virgil and other classical poets, but those which he drew from sharp personal observation. He was much admired for these similes by his early commentators, in the twentieth century, and, between these, in the Renaissance—where they were perceived as being among the main sources of what, to quote Tasso, ‘the Latin writers call evidenzia, the capacity to put things before our eyes, and to particularise’.

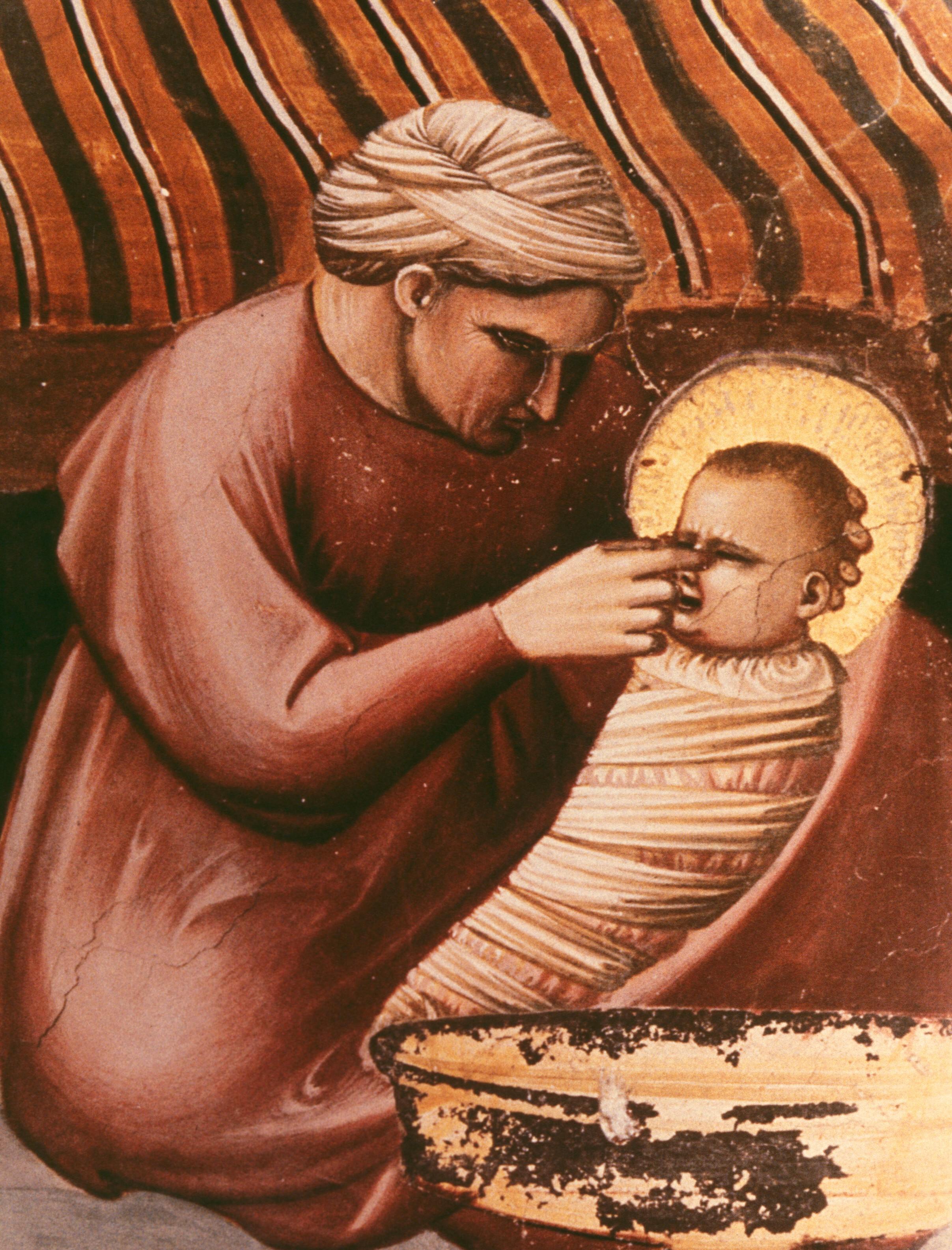

Albert Einstein said that ‘God hides himself in the details’—‘Der liebe Gott steckt im Detail’—and it is in the details you must look for Him. In this love of sharply observed detail, Dante is not only close to Homer, as Tasso says, but also close to Giotto. The following example from the Scrovegni Chapel would be enough alone to make the point:

A painter who can concentrate like this on a midwife clearing the mucus and gubbins from the eyes of a newborn baby can find divinity in the humblest task, and in the words of George Herbert, ‘make that and the action fine’. However, I want to add another image, also from the Scrovegni Chapel, in order to take note of the distinct causes of Giotto’s realism, which so impressed his contemporaries and us.

I think we must distinguish four main factors, working together: first of all, delight and skill in drawing complex objects from difficult angles; second, mastery of the principles of linear perspective; third, the art of modelling by lighter and darker tones to suggest relief; and fourth, close observation of, and empathy with, human body language.

The third dimension is created on the flat surface of the fresco by the confident treatment of the architecture, which immediately creates an apparent depth of several feet to accommodate the human figure. In this space, Giotto places the massive, solid, ‘volumetric’ figure of the serving girl, whose mass is made evident (‘placed before our eyes’) by the use of ‘lights and shadows’, ‘luci ed ombre’, especially over her knees. The attitude or posture of the young woman tells us that, while she continues mechanically with the task of spinning, she is trying to overhear the words spoken by the angel in the room beyond the door!

Just how important posture and gesture are in revealing states of mind, will be confirmed if we close in on the figure of St Anne, who is captured here in the very moment when her prayer is granted—her prayer that she may at long last, in old age, bear a child:

Her prayer is granted with the Annunciation of the birth of a daughter, the Virgin Mary; her face shows the realistic observation of the crowsfeet round her eyes, showing her age, and, more importantly, the set of her head and the intensity of her gaze, showing the intensity of her faith and love. This is an unromanticised face, but it is the face of the grandmother of the ‘Saviour of the World’.

I may seem at this point to have strayed a long way from Dante and the Purgatorio; but if I wanted to find words to match the simplicity, intensity and sublimeness of this image, they would come from canto 8, describing one of the souls in Antepuratory at prayer:

Ella giunse e levò ambo le palme,

ficcando li occhi verso l’orïente,

come dicesse a Dio: ‘D’altro non calme’.

‘Te lucis ante’ sì devotamente

le uscìo di bocca e con sì dolci note,

che fece me a me uscire di mente.

(Purg. 8, 10–15)

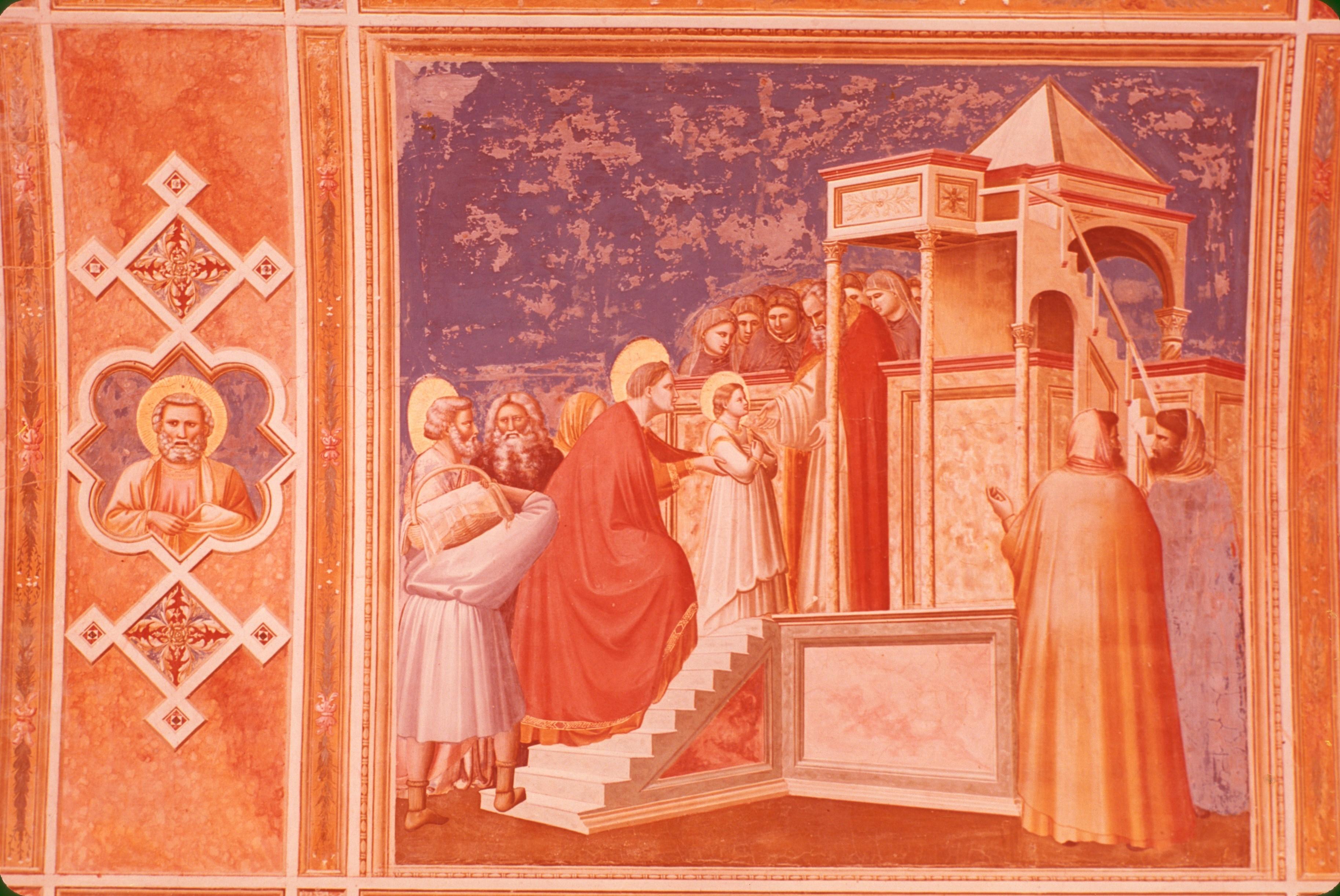

According to the Golden Legend, only three years after the birth of the Virgin, St Anne would renounce her daughter, dedicating her to the service of the Lord in the Temple at Jerusalem.

The line of her back, carried forward in her outstretched arms, reveals a certain solicitude and anxiety (left)—she is a little like a mother pushing her timid child up on stage to perform at a school concert. However in her face and eyes (right), where, as Dante says, ‘il sembiante più si ficca’, I think you can read pride, a hint of sadness, and yet resignation to the will of the Lord—all the complex ‘movements of the heart’ (‘i tristi e cari moti del core’, as Leopardi called them), that one used to feel when a daughter got married, or would feel when a daughter goes into a convent. You cannot get closer to Dante than this: ‘più Dante di così si muore’.

Of all the gestures that express the feelings of affection, friendship or love, the most common is obviously the embrace, so common that it can be banal. But great painters and poets are rarely or never banal; as I am now going to demonstrate by letting you see four ‘variations’ on the ‘theme’ of the embrace: two in the Scrovegni Chapel, and two in Purgatorio.

Fig. 21: Giotto fresco in the Scrovegni chapel (l); and detail from same (r).

The first is the best known, that of Judas. A false and treacherous embrace, so exaggerated, so over the top, that the yellow cloak of the traitor, with its diagonal folds, almost completely conceals the body of Jesus, whose face—noble, calm, dignified—makes the maximum contrast with the rodent, or baboon face of Judas.

No one who has seen this detail can ever forget the precise distance that separates the two profiles, nor what we know to be the meeting of their gaze.

Giotto’s second embrace is almost as well known, the meeting of St Anne and St Joachim, the future parents of the Virgin Mary, outside the Golden Gate. This is an embrace between husband and wife, well advanced in years, childless, who are meeting again after a long and painful separation following the husband’s public humiliation, precisely because he had not produced a child.

Joachim’s arm is free (not concealed by the cloak); and the folds of his cloak are not produced by a false, rhetorical gesture, but, naturalistically, by the knot or pin at his shoulder. The two faces are not held apart, like those of Jesus and Judas, but touching and overlapping; Anne’s hands are caressing her husband’s beard, and the hair on the nape of his neck. In Catholic theology and iconography, this was the embrace in which Mary was conceived without concupiscence, the moment of the ‘immaculate conception’.

The embraces I want to examine in Dante’s Purgatorio are very different from these, and from each other, but no less surprising and moving. Early in the cantica, while Dante and Virgil are still on the shore of the Mountain of Purgatory in the waters of the Southern Ocean, a vessel arrives, powered and piloted by an angel, carrying a precious cargo of newly dead souls who are about to begin the process of purgation.

The souls disembark, and Dante is recognised by one of them. The passage is very well known:

Io vidi una di lor trarresi avante

per abbracciarmi, con sì grande affetto,

che mosse me a far lo somigliante.

Ohi ombre vane, fuor che ne l’aspetto!

tre volte dietro a lei le mani avvinsi,

e tante mi tornai con esse al petto.

(Purg. 2, 76–81)

It is the ancient motif that Dante found in Virgil, who found it in Homer (and perhaps it is in every account of a descent to the Underworld)—of the impossibility of any embrace with a ghost, any embrace with the ‘shadow bodies’ of the dead. As you will read, Dante recreates the epic pathos of the moment in the second terzina.

The same motif will be repeated, but transformed—given a further musical variation, far more moving—in canto 21. We are now high up the mountain, on the fourth of the seven terraces where the penitent souls make expiation and are purified. The Roman poet Statius, newly released from purgation, has caught up with Dante and Virgil, not knowing who they are; and, in introducing himself, he has praised Virgil extravagantly for his influence on him. Dante gives him the amazing news that he is actually in Virgil’s presence, and instinctively Statius tries to embrace his master, not round the neck though, but ‘where the inferior should take hold’, ‘dove il minor s’appiglia’—around his feet:

Già s’inchinava ad abbracciar li piedi

al mio dottor, ma el li disse: «Frate,

non far, ché tu se’ ombra e ombra vedi».

Ed ei surgendo: «Or puoi la quantitate

comprender de l’amor ch’a te mi scalda,

quand’ io dismento nostra vanitate,

trattando l’ombre come cosa salda».

(Purg. 21, 130–6)

In this case, the impossible embrace was between one shade-body and another, and so it was doubly ‘in vain’. In any case it would have been difficult to paint the scene as described, because a painter must treat shades like a solid thing if he is to make them visible, and hence the point of Virgil’s remonstrance would be lost. If anyone could have rendered the pathos of this moment, though, it would have been Giotto; and, for me, Dante is nowhere closer to Giotto than he is in these lines.

According to the famous epigram of Simonides, which was quoted over and over again, ‘a picture is a silent poem, and a poem is a talking picture’. To this I would add that, in the Middle Ages, a good many words used technically, literally, in the art of painting, were taken over and applied metaphorically to the art of poetry. So, for example, a figure of speech was regularly called a rhetorical ‘colour’, as in the following passage from the Vita nuova, and the poetic or rhetorical elaboration of a simple idea was compared to ‘colouring in’ the outlines of a ‘drawing’ or to ‘clothing’ a nude body with a a rhetorical ‘garment’ (‘vesta di figura’):

…però che grande vergogna sarebbe a colui che rimasse cose sotto vesta di figura o di colore rettorico, e poscia, domandato, non sapesse denudare le sue parole da cotale vesta, in guisa che avessero verace intendimento.*

(Vita nuova XXV, 10)

«Per te poeta fui, per te cristiano:

ma perché veggi mei ciò ch’io disegno,

a colorare stenderò la mano».

(Purg. 22, 73–5)

Thus I am being entirely faithful to Dante’s own metaphors, if I say that he is closest in essence to the painters of his day, not when he is describing a bodily gesture—an embrace, a shudder, or a smile, which an artist can represent—but when he reproduces what we can call a ‘verbal gesture’—as it were, ‘drawing’, ‘outlining’, phrases he had heard, spoken in his native Italian—and when he heightens the natural, idiomatic utterance, by ‘colouring’ it through the use of rhythm and rhyme.

It is through his command of ‘verbal gestures’—authentic, but heightened, ‘drawn in outline’ and ‘coloured in’—that he is able to create a character on the page or evoke an emotion in our imagination.

Indeed, there are times when it seems as if he can establish a whole personality in a single terzina. I shall give three examples of what I mean. They are the first words spoken in the poem by three women, who reveal themselves immediately as intensely ‘feminine’ (in the sense that this word had in my youth), but as amazingly different from each other. Beatrice (show bottom of slide) is the severe mother, about to scold her naughty son:

«Dante, perché Vergilio se ne vada,

non pianger anco, non piangere ancora;

ché pianger ti conven per altra spada».

(Purg. 30, 55–7)

Lia is the dream woman of every French impressionist:

«Sappia qualunque il mio nome dimanda

ch’i’ mi son Lia, e vo movendo intorno

le belle mani a farmi una ghirlanda».

(Purg. 27, 100–102)

While la Pia is highly delicate and self-effacing, in her concern for Dante’s health and wellbeing:

«Deh, quando tu sarai tornato al mondo

e riposato de la lunga via»,

seguitò ’l terzo spirito al secondo,

«rircorditi di me, che son la Pia…»

(Purg. 5, 130–3)

It will be obvious—and that is why I haven’t bothered to say it until now—that Dante is literally ‘closest’ to the painters and sculptors of his day when he is describing works of art. This he does with great bravura in his account of the relief sculptures which are carved on the marble wall of the first circle of Purgatory, and which I show you here in a late fifteenth-century fresco by Signorelli:

Deliberately pitting himself against Virgil in his description of the forging of the shield of Aeneas by Vulcan, Dante ‘puts before our eyes’ scenes that have been carved by no mortal man, but by God himself, and which are therefore endowed with a miraculous expressiveness, such that you would swear that the figures are not only moving but talking.

Let us have a look the first of the three, Dante’s evocation of the Annunciation:

L’angel che venne in terra col decreto

de la molt’ anni lagrimata pace,

ch’aperse il ciel del suo lungo divieto,

dinanzi a noi pareva sì verace

quivi intagliato in un atto soave,

che non sembiava imagine che tace.

Guirato si saria ch’el dicesse ‘Ave!’;

perché iv’ era imaginata quella

ch’ad aprir l’alto amor volse la chiave;

e avea in atto impressa esta favella

‘Ecce ancilla Dei’, propriamente

come figura in cera si suggella.

(Purg. 10, 34–45)

We are told here that Gabriel was carved in a ‘gentle gesture’, in such a life-like way (‘verace’) ‘that he did not seem a silent image but you would have sworn he was saying Ave’, while in Mary’s face and attitude (‘atto’), one can read as if they were on a wax seal the words reported in the Gospel of Luke: Ecce ancilla Dei.

Dante’s commentators point out that it was not uncommon in medieval art to write a snatch of speech, and insert it in a ‘balloon’ coming out of a character’s mouth, just as modern cartoonists do. Great artists did it—here is Simone Martini’s famous version now in the Uffizi, where you can read, in the balloon, Ave gratia plena, dominus tecum:

But, as with the caryatid earlier, the commentators can be misleading, and there is a ‘suggestion of the false’ here (suggestio falsi). Simone is such a master that we don’t need the words to understand what Gabriel and Mary are feeling, and therefore what they would be saying; God, as sculptor, is an even greater master, and he would have even less need of a balloon.

The difficulty for the painter, any painter, would lie not in finding the visual equivalent of a ‘verbal gesture’, but in the representation of the complex ideas and concepts that Dante interweaves with his description. How do you paint or carve ‘the peace…which was sought with tears for many years’, or the ‘key which opened the recesses of divine love’?

The relationship between these sister arts of poetry and painting appear with greater clarity if you consider the words of Dante’s ‘ecphrasis’ (this being the technical term for the rhetorical description-cum-evocation of a work of art), with the two details of the Annunciation pictured below, as carved by Giovanni Pisano on the pulpit in Pistoia. They will also help you to visualise Dante’s ‘cliff of marble’ which is ‘adorned with reliefs’:

Remaining on the subject of Dante’s ecphrases, I perhaps ought to analyse, terzina by terzina, Dante’s description of the intaglios on the pavement of this first circle of Purgatory, representing the divine punishment of such proud figures as Lucifer, Rohoboam and Saul, Yet in my opinion, the Biblical scenes described by Dante, which most closely recall the paintings of the early fourteenth century are to be found, not on the circle of the Proud, but in the circle of the Angry, ‘gli iracundi’.

On that circle, Dante and Virgil were enveloped in a a cloud of black smoke so thick and acrid that Dante was forced to close his eyes, and walked on—as you see below in a Bolognese illumination—I quote, ‘like a blind man, close behind his guide, in order not to lose his way’ (‘sì come cieco / dietro a sua guida per non smarrirsi’):

Dante entered into a sort of trance, and he saw three ‘ecstatic visions’ of examples of mildness, ‘mansuetude’, which God transmits like a television programme for the benefit of the souls in the smoke (who would be unable to see carved images), and which are, so to speak, ‘received’ by Dante on the mental ‘screen’ in his head.

I shall conclude this lecture, therefore, by giving the words of the first and most beautiful of these ‘ecstatic visions’, alongside a picture of the same scene, this small panel painting on wood by Duccio:

The scene is usually called ‘Jesus among the Doctors’; but, as we shall see, in Dante’s poem, as in Duccio’s picture, it really counts as an episode in the Life of the Virgin: the focus is on her. We began, as you will remember, with the figure of Mary, as interpreted by Duccio, and we shall end with Mary intepreted by Duccio. The scene is set in the Temple at Jerusalem:

Ivi mi parve in una visïone

estatica di sùbito esser tratto,

e vedere in un tempio più persone;

e una donna, in su l’entrar, con atto

dolce di madre dicer: «Figliuol mio,

perché hai tu così verso noi fatto?

Ecco, dolenti, lo tuo padre e io

ti cercavamo». E come qui si tacque,

ciò che pareva prima, dispario.

(Purg. 15, 85–93)

[Again, at the end of this document was a sketch for a ‘Primo cominciamento’, which I have edited. It could serve, with considerable editing, as a more general introduction to a volume. There is also a discussion of Purgatorio 15, which I have also edited up.]

This lecture is a first attempt at a series of three devoted to Dante and the Visual Arts, inquiring into the links between his imagination and the imagination of painters and sculptors, investigating influences in both directions, studying theoretical models of the relationship between the sister arts in the Middle Ages, and exploring the vaguer ‘affinities’ which one always feels to exist between works in different media which were composed or executed in the same society.

In due course, I hope to work up the lectures into a short book, and if I do I shall mention our meeting this evening, and thank Giorgio Campanaro for giving me this chance to put some order into my thoughts. The chapters or lectures will each focus on one cantica of the Divine Comedy; but each will have a major theme, and they will be very different from each other.

The first chapter will be devoted to the Inferno. It will look at representations of Hell and devils before Dante wrote the Inferno, to see how far his imagination was conditioned by earlier artists, and it will go on to look at some of the illustrations in the early manuscripts of the Comedy, to see how closely these artists read Dante’s text, and how far they merely fall back on traditional iconography.

The third chapter will be devoted to the Paradiso. It will be concerned above all with the representation of light. As you will know, for most of the cantica, the faces and bodies of the souls whom the pilgrim meets are hidden from his eyes by the intensity of the light that they themselves irradiate, and all he can see, as he travels up through the planets, and the constellation of Gemini, are patterns formed by their individual lights. Inevitably therefore I shall look at the art of earlier centuries: the stained glass windows of the twelfth century and mosaics in Ravenna in the early sixth.

Tonight’s lecture is about Purgatorio, the cantica where the relationship between Dante and the souls he meets is the most relaxed and intimate, and where the chief interest lies in what I call the ‘affinities’—a deliberately imprecise word—the affinities between Dante and the painters and sculptors who were active in Tuscany and Central Italy during his own lifetime.

I have been tactfully reminding you of some of the main names, and the relative dates of some of the most important, the most epoch-making works of art.

–-

Notice, too, the links between the concept of ‘light’, ‘luce’, which is implicit in the phrase ‘beautiful planet’, and ‘loving’ (‘amare’). At this point in the poem

Dante the pilgrim is about to restart on his journey to heaven, the place which Dante will later call the ‘angelic temple, whose frontiers are only love and light’ (

l’angelico templo, / che solo amore e luce ha per confine’). You may remember from the previous lecture that all Dante’s illustrators represent Virgil and Statius as fully clothed—no less than the living Dante—and they represent all the other souls encountered naked, but as though they had solid bodies.

–

…by showing you painted images of two scenes from the New Testament, executed in the first half of the fourteenth century: a miniature on parchment, attributed by the experts to the school of Franco da Bologna (who, you remember, was the artist who eclipsed Oderisi)

–-

In addition to these images, below are the words which Dante evokes the two scenes, and in which he is clearly influenced by paintings similar to them. The first scene is that of the martyrdom of Saint Stephen:

Poi vidi genti accese in foco d’ira

con pietre un giovinetto ancider, forte

gridando a sé pur: «Martira, martira!».

E lui vedea chinarsi, per la morte

che l’aggravava già, inver’ la terra,

ma de li occhi facea sempre al ciel porte,

orando a l’alto Sire, in tanta guerra,

che perdonasse a’ suoi persecutori,

con quello aspetto che pietà diserra.

(Purg. 106–14)

–—

So what I am trying to do in this lecture is to call your attention to different kinds of analogy or affinity between different episodes in the Purgatorio, different artists, or different phases in the work of one artist—for example, Nicola Pisano.

In the reliefs on the pulpit in the Baptistery at Pisa, in 1260, Nicola is known to have been imitating a classical Roman sarcophagus. This is the Adoration of the Three Wise Men:

IMAGE x1

Look at Mary and at the first king. Yet when he carved the same scene on the pulpit in the Cathedral at Siena a few years later, in 1269, he was drawing his inspiration from the most up-to-date avant garde art in the North:

IMAGE x1

Look at the first king here! These are French, Gothic, agitated, linear—and if I had not mislaid the relevant slide, you would have seen that the crouching lions who support the whole pulpit in Siena are neither classical nor Gothic, but very close to the beasts in the Romanesque art of the twelfth century in the Po valley.

With Nicola in mind, let us think about the Divine Comedy. In the Inferno, Dante drew on many of his stylistic experiments in the poems he wrote in the 1290s. You can hear the language and modes of the so-called ‘comic’ or ‘realistic’ style in the exchange of insults between Master Adam and Sinon; you can hear the ‘harsh rhymes’ of the ‘songs for a stony lady’ in the description of Lower Hell; and you can hear his attempts to mimic the noble rhythms of Virgil in the words of Ugolino and Francesca. In other words, there are many different registers, many different styles, in the same cantica.

On the seventh circle, the penitent souls of the lustful walk around the mountain, within a wall of flames, in two columns, proceeding in different directions depending on whether their lust was ‘straight’ or ‘gay’, heterosexual or homosexual.

Every time the two columns of souls meet and cross, they exchange kisses, each soul to every other, ‘una con una’—but they never pause or prolong the kiss, ‘content’, says Dante, ‘with a brief celebration’ (‘sanza restar, content a brieve festa’). Their swift and chaste salutation is made ‘evident’, ‘put before our eyes’, ‘particularised’, by the surprising simile, half biblical, half naturalistic, of the ‘dark column’ of ants who ‘nuzzle each other’ (‘che si ammusa<no>’, ‘l’una con l’altra’).

NOTES

- At page ten, or thereabouts, there is an explanation for the skipping over of a discussion of Pisano, which I am not entirely sure works on paper—where of course there is time. I have edited it, however, for the purpose of this first draft, and we can do what we will with it.

- I have edited, once again, the leftover parts in the source document which followed the conclusion.

![Figure 4: (P_Pu_4) Simone Martini’s* Maestà *at [dove?].Palazzo comunale, Siena](media/image4.jpeg)

![Figure 5: (P_Pu_5) Vault of Scrovegni Chapel.* [NB THIS SLIDE OPTIONAL]](media/image5.jpeg)

![Figure 6: (P_Pu_6) Illuminated O from Liberale da Verona (l); [which church is this] it’s a manuscript (right top); mosaic in Battistero at Florence (right bottom)](media/image6.jpeg)

![Figure 7: (P_Pu_7) Duccio’s* [title needed] Madonna and Child *(l); detail from same (r)](media/image7.jpeg)

![Figure 8: (P_Pu_8) Ugolino di Nerio’s* [title needed] *(l); detail from same (r)](media/image8.jpeg)

![Figure 9: (P_Pu_9) Detail of feet from Ugolino di Nerio’s* [title needed]*](media/image9.jpeg)

![Figure 10: (P_Pu_10) Detail from Duccio’s* [title needed]*](media/image10.jpeg)

![Figure 13: (P_Pu_13) [caption needed - date and origin perhaps best?]](media/image13.jpeg)

![Figure 25: (P_Pu_26) [I wasn’t 100% sure which of the two slides was intended here (presumably the latter?) so I have inserted both]](media/image28.jpeg)