The Visual Arts and Dante’s Paradiso

This lecture returns to Dante, and to the relationship of his poetry with the visual arts, and will concentrate on the final cantica of his Divine Comedy, the Paradiso. ‘Paradiso’, you will be glad to hear, does mean ‘Paradise’ as we use the word in English, and in this third phase of his journey Dante flies up from the earthly Paradise, on the summit of the Mountain of Purgatory, and ends his journey beyond the confines of the physical universe in the celestial Paradise, Heaven with a capital H, the abode of God, the angels and the blessèd.

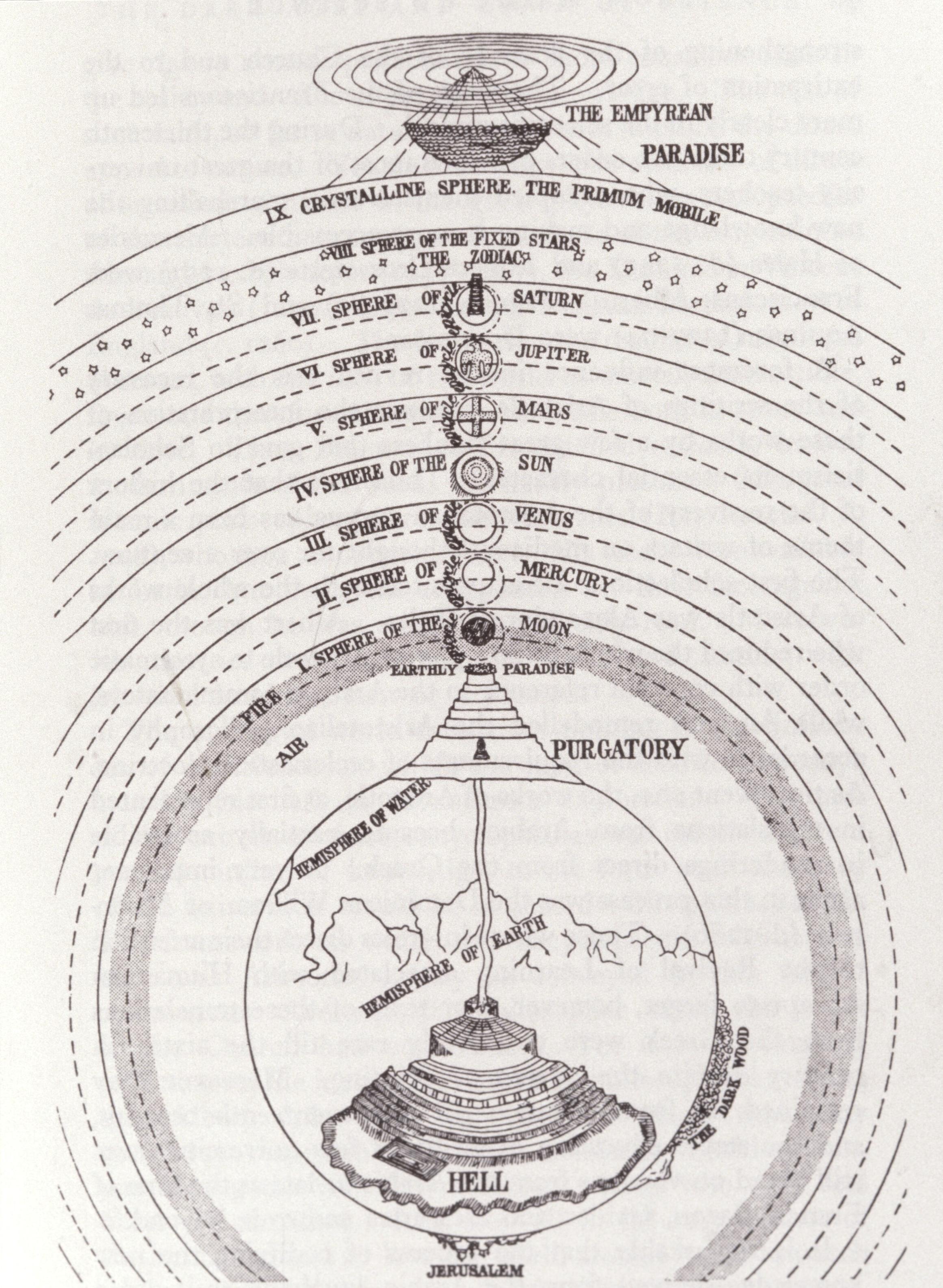

However, for twenty nine of the thirty three cantos, Dante and Beatrice make their journey through the ‘heavens’ with a small H, and in the plural. You must remember that the medieval universe was a huge sphere, made up of concentric spheres, like the layers of an onion, with an unmoving sphere of solid Earth at the centre, then the three liquid spheres of Water, Air and Fire, and then nine spheres of aether, transparent, solid, spinning round the earth, the first seven of them bearing just one luminary—the planets—in the order you see, the eighth carrying the constellations of ‘fixed stars’, and the ninth, the primum mobile, without any luminaries, imparting its diurnal revolution to all the spheres that it encloses:

In canto 30, Dante and Beatrice will pass beyond this ‘greatest body’, beyond matter, space and time, into the tenth heaven, which he calls the Empyrean, the Heaven with a capital H. This, as we are told in the opening lines of the cantica, is the ‘heaven that receives most of the divine light’. But, as we are also told in the first three lines, the radiance of God (his ‘gloria’), penetrates the whole of the universe, even though it fades in intensity in proportion to the distance from its source.

So, light pervades the nine aetherial heavens, through which Dante the pilgrim has to pass; and you must also remember that he and Beatrice actually enter each of the luminaries in turn. He does not just go to the moon, as Neil Armstrong did, and onto its surface; he penetrates into its body, and similarly with the sun and the other ‘planets’. So there is no ‘pit’ as in Hell, no ‘mountain’ as in Purgatory—in fact, no landscape at all, no body of any kind composed of the four elements, but only transparency, and light of ever increasing brilliance.

In the first 29 cantos, where we shall remain for the greatest part of this lecture, Dante does see and converse with the souls of the dead as he had done in Hell and Purgatory, because it is arranged that groups of souls descend from the Empyrean to welcome him in each of the heavens in turn. The souls of the blessed, the ‘beati’, also irradiate light themselves, which increases in intensity in proportion to the degree of their blessedness, and they are perceived by Dante the pilgrim as ‘lights, torches, or lanterns’.

In the first of the heavens, in the Moon, closest to the earth, Dante can still see the human faces within their radiated glory; even though he is slow to recognise his childhood friend, Piccarda, and her companions, because ‘something divine is shining out of their countenances:

«O ben creato spirito, che a’ rai

di vita etterna la dolcezza senti

che, non gustata, non s’intende mai…»

…

Ond’io a lei: «Ne’ mirabili aspetti

vostri risplende non so che divino

che vi trasmuta da’ primi concetti.»

(3, 37–9, 58–60)

However, already in the second stage in his ascent, the planet Mercury, and in all the higher spheres, the spirits or souls have become splendours, ‘splendori’, who express their joy in seeing Dante by a perceptible increase in their refulgence. The pilgrim cannot see the features of Romeo da Villanova, rather ‘his light shines within the pearl’ of the planet itself:

sì vid’io ben più di mille splendori

trarsi ver’noi, e in ciascun s’udia:

«Ecco chi crescerà li nostri amori».

E sì come ciascuno a noi venìa

vedeasi l’ombra piena di letizia

nel folgór chiaro che di lei uscia.

(5, 103–8)E dentro la presente margarita

luce la luce di Romeo…

(5, 126–7)

As I mentioned in my first lecture, Dante believed that the proper and specific objects of vision were colour and light. In the second cantica, the Purgatorio, he could and did represent colour and coloured bodies, beginning in the first line of the narrative, ‘Dolce color d’orïental zaffiro’. You will remember too the connections I drew between his poetry and the use of colour by the artists who were his contemporaries. In this last cantica, by contrast, he set himself the task of representing, so to speak, ‘the light, the whole light, and nothing but the light’. This means, among other things, that he has to renounce all that close observation of body language, of smiles and embraces, that also brought him close to the artists of his own time.

By this point you will have grasped my problem. How can there be any relationship between the Paradiso and the visual arts? And what, for example, did his early illustrators do? The answer is that they painted fewer illuminations, and they usually ignored what Dante explicitly says. Below is a lovely image from the best of them all, Giovanni di Paolo, in the first part of the fifteenth century:

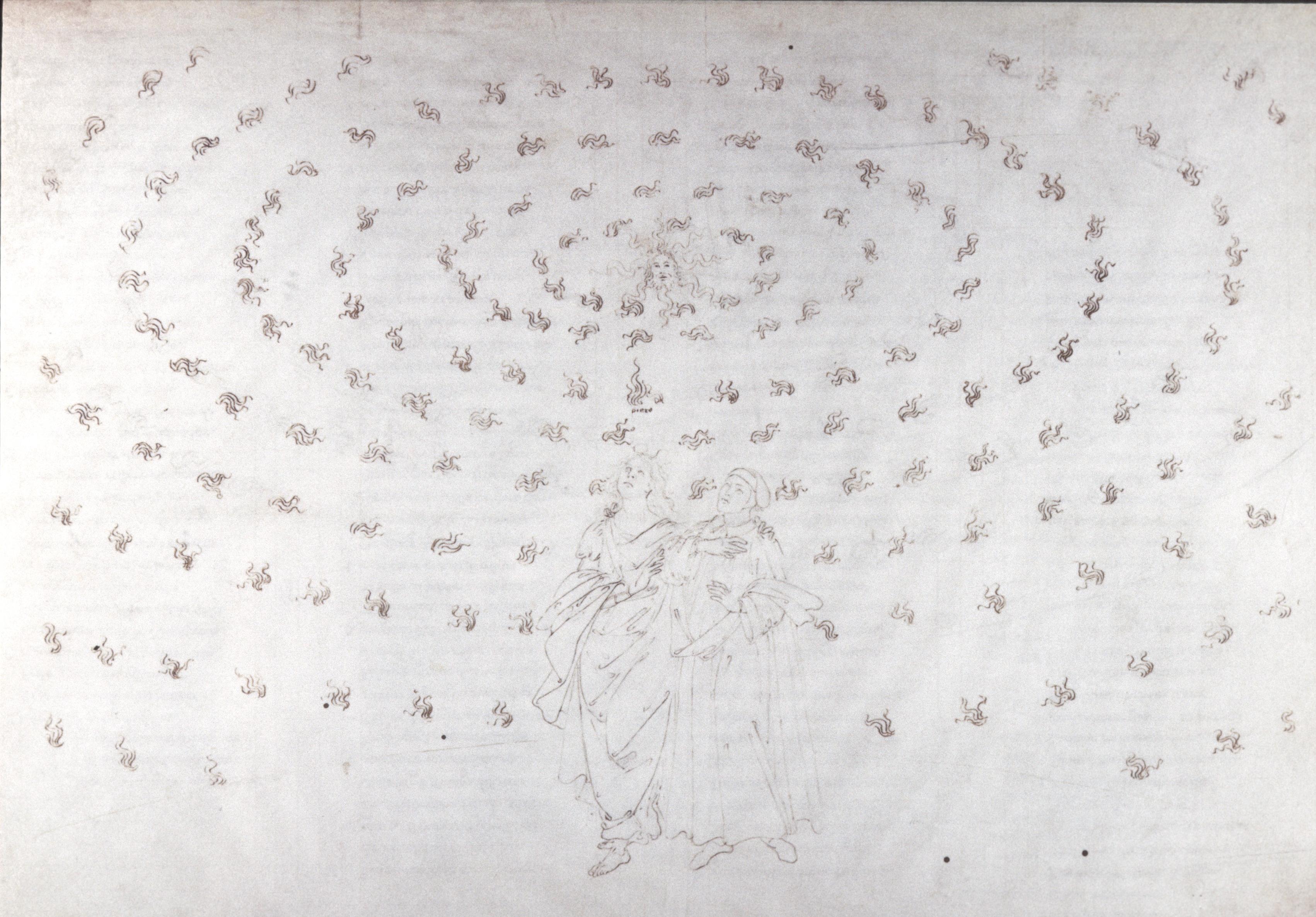

This is Romeo, whose light shines, and those are his daughters and their royal husbands, who are only mentioned in the narrative, and not seen by the pilgrim. Botticelli, whose drawings we shall be looking at in the final lecture, was the first to take Dante au pied de la lettre, and every one of these flaming torches which appear to Dante in the Heaven of the Stars, conceals or ‘steals from our sight’ one of the blessèd, as from the sight of the pilgrim:

This is a good moment to remark that the painters and sculptors who were active in Dante’s lifetime had relatively little to offer to his imagination in the representation of Heaven.

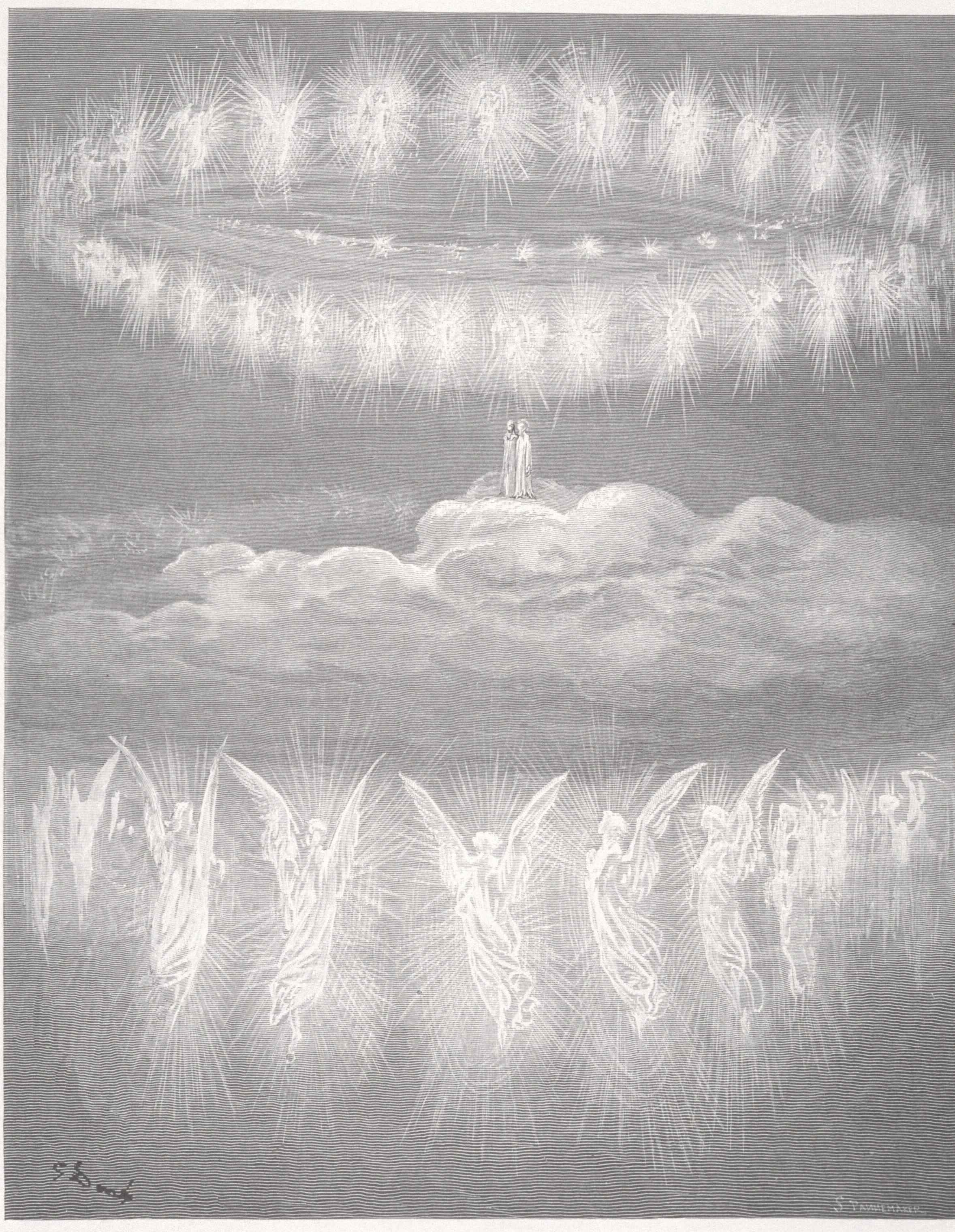

In a scene of the Last Judgement, the blessed traditionally sit on their thrones, mere spectators, betraying no emotion at the diabolic behaviour of the devils below or the torments of the damned, whose suffering does not touch them (‘la cui miseria non li tange’), as in the following detail from Giotto, at Padua:

What you see above is the centre and left hand panel of a triptych by Andrea Orcagna, from the 1370s, now in the National Gallery, which follows very closely the model established for Italian artists by Giotto in Santa Croce at Florence. Yet even here, as you can see, in this Feast Day in Paradise the saints have to sit in rows, and look pretty glum. So, you now know why the visual parallels I am going to adduce will not come from frescos or altarpieces, nor from the great Tuscan masters of Dante’s day.

Rather, we shall cross the Apennines to look at some mosaics from an ancient tradition best exemplified in Ravenna; and we shall cross the Alps to visit some of the great cathedrals of France and England, where the solid walls, as they climb, seem to dissolve and to become light, to see windows, like the so-called ‘Five Sisters’ at York, which were erected in the decade of Dante’s birth, and the Rose Window at Lincoln, originally erected in the mid-thirteenth century, and called the Bishop’s Eye.

The Bishop in question was none other than Robert Grosseteste, a Franciscan philosopher and theologian, translator and commentator, and author of two very influential works on the physics and the metaphysics of light. Indeed, I had originally intended to focus in this lecture on the relevant concepts, scientific and religious, that underly the whole of the Paradiso, but I have cut the treatment of both down to the barest minimum.

…a puncto lucis sphaera lucis quamvis magna subito generetur

…

[Lux], cuius per se est haec operatio, scilicet se ipsam multiplicare et in omnem partem subito diffundere

Grosseteste, De luce seu de inchoatione formarum*

According to Grosseteste, light, by its very nature, cannot not multiply itself. It has a vis multiplicativa; as soon as it exists, it must spread out in all directions, so that if you start with a point of light, it will immediately generate a sphere of light, a sphere of luminosity.

Now, St Augustine had said that ‘God is light’, Deus lux est; and in the Paradiso, Dante the pilgrim first perceives God as a point which was irradiating light, ‘un punto che raggiava lume’. Two cantos later, in Dante’s brief account of the Creation of the Universe, it is made clear that he conceives it as a ‘self-opening of the eternal love into new loves’, and this self-opening is depicted as instantaneous irradiation of the Divine Light, a multiplication of the light which is God.

In this perspective, the medieval cosmos is in principle nothing other than a ‘sphere of rays’ emanating from God, and all bodies whatsoever, even the darkest, and most impenetrable, participate, in different ways, in the nature of light:

Omnia corpora, qualiacumque sint, participant naturae lucis secundum magis et minus.

Alia claritas solis, alia claritas lunae, et alia claritas stellarum. Stella enim ab stella differt in claritate.

(Ad Corinthios 1, 15, 41)

The consequences of this are mind-blowing, and there is not space to go into more than one of them in this lecture. For Dante, as for all thinkers in his culture, there was a hierarchy of light, a ladder, or scale of light:

|

|

At the top of the ladder are bodies that shine, ‘corpi lucenti’, ‘lucent bodies’, in a scale of brightness that goes from the sun at the top to the phosphorescent firefly at the bottom. In the middle come the ‘transparent bodies’, ‘corpi diafani’, such as air, water, alabaster or amber. At the lowest level of all, we find light ‘incorporated’ in all opaque bodies, ‘corpi opachi’, which is a synonym for ‘coloured bodies’, ‘corpi colorati’, which were perceived as forming a scale of colours running from white at the top to black at the bottom.

This leads us to the those two points I want to quickly make about the nature and behaviour of light, as they were explained in contemporary physics and optics, which both fascinated Dante as concepts, and deeply affected his poetry in the Comedy.

In a passage in a prose work, the Convivio, Dante says he follows the usage of philosophers by distinguishing, within the generic term light, three species or successive manifestations; first, light ‘in its fountain-head or beginning’ (in what we have just called a ‘lucent body’), then light as a ‘ray’ in a transparent medium (in what we have just called a ‘diaphanous body’), and finally ‘splendore’, by which he means ‘reflected light’ when it is struck forth again (‘ripercosso’) towards some other part already illuminated:

Dico che l’usanza de’ filosofi è di chiamare luce lo lume, in quanto esso è nel suo fontale principio; di chiamare raggio, in quanto esso è per lo mezzo; di chiamare splendore, in quanto esso è in altra parte alluminata ripercosso.

(Convivio, III, xiv, 5)

These distinctions, which Dante very often observes with great precision, lead me to comment on his use of three verbs to describe the action of light—namely, ‘lucère’ (a verb no longer in use), ‘sfavillare’, and ‘risplendere’—because these distinctions will help us to understand the fundamental difference between the effect of mosaic, and the effect of stained glass.

The verb ‘risplendere’ is linked to ‘splendore’, and Dante often uses it specifically to denote reflected light, when the rays of sunlight are ‘struck back’ in another direction from a surface that is solid, smooth, especially if it has been polished. Such a surface might be leaded glass (i.e. a mirror), burnished gold, white marble, or a precious stone; and Dante refers in three separate similes, (each time referring to the sun’s rays striking the stone), to a ‘balasso’, an ‘adamante’ (diamond) and a ‘rubino’. All these surfaces can reflect light, and be ‘resplendent’ so brightly that they will dazzle our eyes, almost as if the light were coming directly from a ‘lucent body’, a ‘corpo lucente’.

As you will gather, I want you to associate Dante’s expressions with the techniques of mosaic, in which the individual tesserae used to be set at slightly different angles so that each reflects the incident light in slightly different directions, thus creating the effect of a supernatural radiance, which is one of the glories of Ravenna, especially perhaps in the tiny Mausoleum of Galla Placidia:

So much for the verb ‘risplendere’; now we pass to the verb ‘sfavillare’, meaning to ‘sparkle’, or to send out ‘sparks’, ‘faville’. At different moments in the Paradiso, Dante invites us to think of a ‘fire’ or a ‘furnace’, of a ‘coal which gives off a flame’, or the ‘flame of a candle’. A fire, with its leaping flames, can be thought of as a pulsating source of light, varying in intensity from one moment to the next,

and of course, able to send out sparks (‘scintille’, fiammelle’), as, for example, when burning logs are struck.

The point I am driving at is that Dante was well aware of a source of light which can be described as flaming, sparkling, scintillating, or coruscating and apparently alive, and for that very reason impossible to simulate in a painting. Nevertheless, you can sometimes see an effect very similar to sparkling in the stained glass windows of our cathedrals and churches; that is, North of the Alps, where the weather is often ‘cloudy bright’, and the wind is driving the clouds, such that the sun is constantly going in or coming out again, or at least varying in intensity, depending on the nature of their cover. Then, the windows do seem to be not only ‘lucent’ bodies, but ‘sparkling’ bodies, ‘sfavillanti’.

And so we come to the third of Dante’s verbs, lucère. As you will have gathered, my thoughts about sparks and pulsating sources of light, were inspired by this passage in Canto 18 of Paradiso, where the lights which rise up like innumerable sparks, are the souls of the just, justorum animae, who according to Solomon ‘will shine and run to and fro like sparks in the stubble’:

E vidi scendere altre luci dove

era il colmo de l’emme…

…

Poi, come nel percuoter d’i ciocchi arse

surgono innumerabili faville,

…

resurger parver quindi più di mille

luci e salir, qual assai e qual poco,

sì come ’l sol che l’accende sortille…

(18, 97–8, 100–1, 103–5)Justorum animae…fulgebunt et tamquam scintillae in harundineto discurrent.

(Liber sapientiae, 3, 1, 7)

This should remind you of what I said in the beginning: that in the Paradiso, there is a further class of ‘lucent bodies’ to add to the sun or furnaces or torches, namely, the ‘blessed’, whose outshining love and joy turn them into so many lights and fires, and who cannot therefore be represented faithfully by a painter spreading his powdered colours onto a wall or a wooden panel.

Put yourself for a moment into the shoes of a miniaturist who was called upon to paint the arrival of Dante and Beatrice in the sun:

Lo ministro maggior de la natura…

…

si girava per le spire…

…e io era con lui; ma del salire

non m’accors’ io…

È Beatrice quella che sì scorge

di bene in meglio, sì subitamente

che l’atto suo per tempo non si sporge.

(10, 28, 34–5, 37–9)

Nature’s prime minister…was revolving through the spirals of his course…and I was with him; but I didn’t notice my ascent…Beatrice it is who guides from good to better, so swiftly, that her action does not extend into time.

In other words, she acts instantaneously, which does not mean just ‘very quickly’, but literally ‘in no time at all’. Now, the most talented of the miniaturists who took up the challenge of ‘figuring Paradise’ (to use Dante’s phrase, ‘figurare il Paradiso’), was without doubt the artist from Siena, Giovanni di Paolo, whose work we have already seen once, and who was painting about a century after Dante’s death.

His work, of which another example is given above, reveals him to be immensely accomplished and intelligent. This stylised, but recognisably Tuscan, landscape under the rays of the sun, presents the sun precisely as Nature’s ‘minister’, servant, who ‘imprints’ or ‘stamps’ the world with the ‘power of the heavens’. Beatrice’s gesture and attitude is really worthy of ‘her who leads from good to better’, while space flight is well suggested in the sinuous lines of the two bodies, and by Beatrice’s fluttering veil. But alas, Dante himself says that he completed this phase in the instant—he didn’t fly, he just arrived.

Let us proceeed in the same Canto, on to the following lines:

Quant’ esser convenia da sé lucente

quel ch’era dentro al sol dov’ io entra’mi,

non per color, ma per lume parvente!

Perch’ io lo ’ngegno e l’arte e l’uso chiami,

sì nol direi che mai s’imaginasse;

ma creder puossi e di veder si brami.

E se le fantasie nostre son basse

a tanta altezza, non è maraviglia;

ché sopra ’l sol non fu occhio ch’andasse.

(10, 40–8)

How lucent in themselves

must have been what was in the sun where I entered,

appearing, not by colour, but by light.

If I were to summon up all my talent, and art and experience,

I should never express it in such a way

that one could form an image of it.

And if our imaginations are too low

for such heights, it is no wonder;

for no eye has gone so high as the sun.

If it is impossible to represent the instantaneity of space flight, what are we to say about the souls of the blessed, who appear to Dante within the body of the sun, and shine out so brilliantly that they overpower the light of the sun itself? Dante specifies that they were visible to him not because they were different in colour from the sun, but thanks to the intensity of the light they were irradiating.

Giovanni di Paolo admits defeat. He ‘chucks in the towel’, so to speak, and ignores the letter of the text. Thus, he instead uses different colours to render visible (‘parvente’) at least the different conditions of the souls when they were alive.

We can distinguish the Venerable Bede, by his monk’s habit; Saint Isidore, Bishop of Seville, by his mitre; two university professors from Paris, Richard of St Victor and Siger of Brabant; and, in Dominican robes, St Albert the Great and St Thomas Aquinas—or, with the crown on his head, King Solomon:

I would like to turn back now to stained glass windows, and think a little more about them. The glass itself is a ‘coloured body’, a corpus coloratum, no less than the tesserae of a mosaic, or a mineral like lapis lazuli used by a painter. Yet because it allows the light to ‘shine through’—because it is ‘trans-lucent’—when we look at it set in the window, from the darker interior of the nave, it has the effect of being a ‘lucent body’, of being a source of light, a ‘spring’ from which light ‘flows’, or a ‘fountain-head’—and remember that all these words were originally metaphors, being ‘carried across’ from water to light.

In other words, stained glass is the only medium which can give the effect that Dante had in mind when he described the souls of the blessed in the heavens; and I have chosen an image of the Virgin Mary at this point, partly because Dante will refer to her, metaphorically, as a ‘fountain’ of Hope, ‘fontana di speranza’, or a ‘blazing torch’ of Charity, ‘face di caritate’.

Remember, too, the point I made earlier about the effects of seeing stained glass in a non-Mediterranean land, on windy, cloudy-bright days when the glass can seem like a flaming, sparkling fire, and when, towards sunset, as the rays of the sun are almost horizontal, the window can become what Dante calls ‘fulvido di fulgore’, literally, ‘fulvid with lightning’.

Nor is the translucency of the glass itself the only point of contact between Dante’s poetry and the medieval stained glass window. Let us think for a moment about the technique of inserting bits of glass into a window.

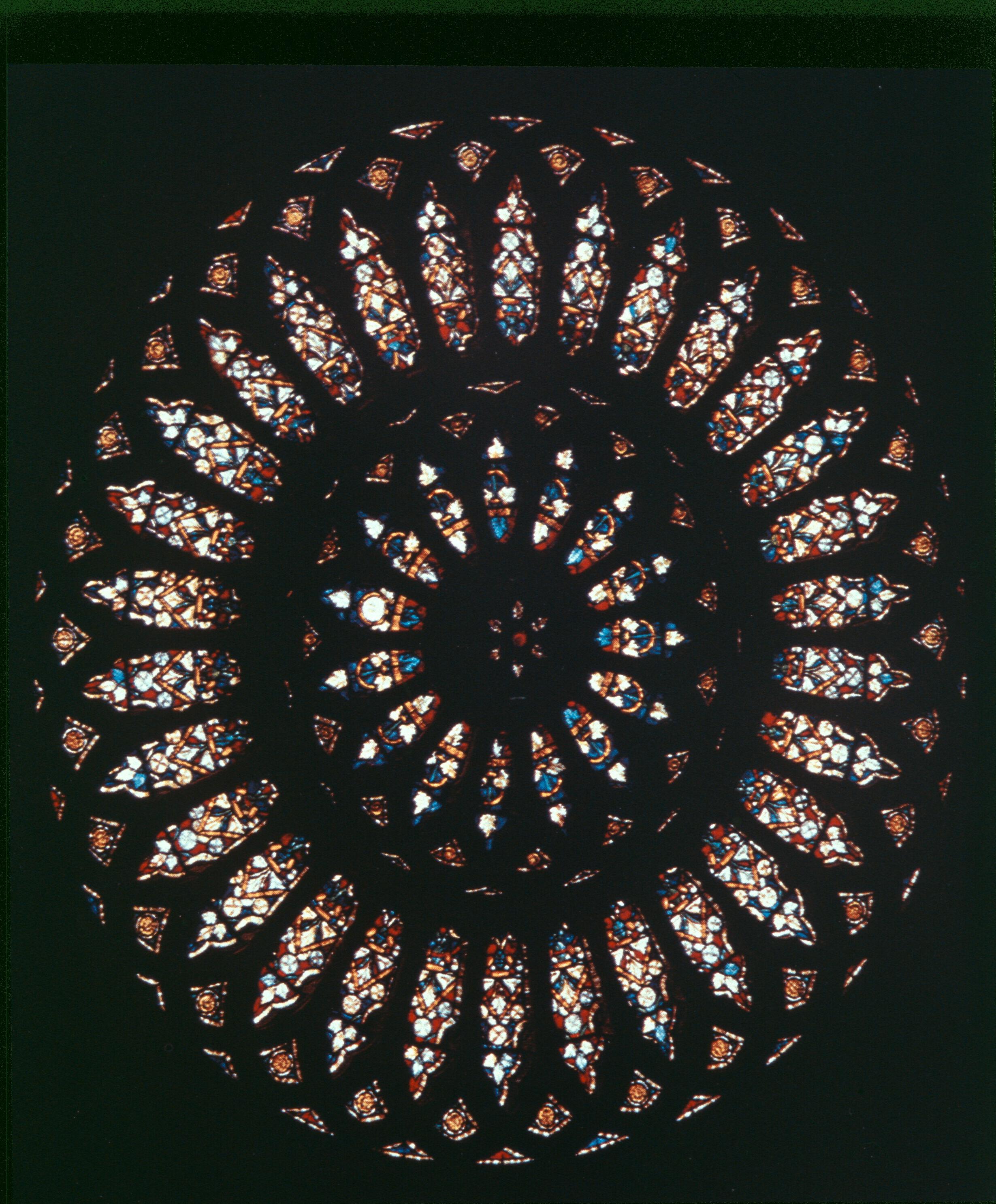

As you can see in the image above, a famous detail from our Westminster Abbey, the individual pieces of coloured glass are first set in strips of lead, a soft and malleable metal which can be moulded to form flexible, variable outlines. The leaded strips are then inserted into a stone frame, which can also be carved into regular, geometrical shapes, triangles, quatrefoils, ovoids. These stone shapes can then be put together, for example, to create a huge circle like that shown on the right: one of the so-called ‘rose windows’, that became common in the twelfth century. As you can see, the ‘roses’ are extremely beautiful from the outside, pure geometry. The example pictured is in Assisi, at the church of St Clare, and was completed in 1265, the year of Dante’s birth—so he would certainly have been familiar with this kind of window.

When you go inside, the geometrical shapes, which are ‘common sensibles’, are enhanced by colour and light, ‘the proper visibles’. Below is the same window, from the inside; and there are elements in a window like this which may have suggested some of the pyrotechnic displays that Dante imagined in his Paradiso:

In this case, it is hard not to think of the three concentric circles of lights that appear to Dante in the Heaven of the Sun.

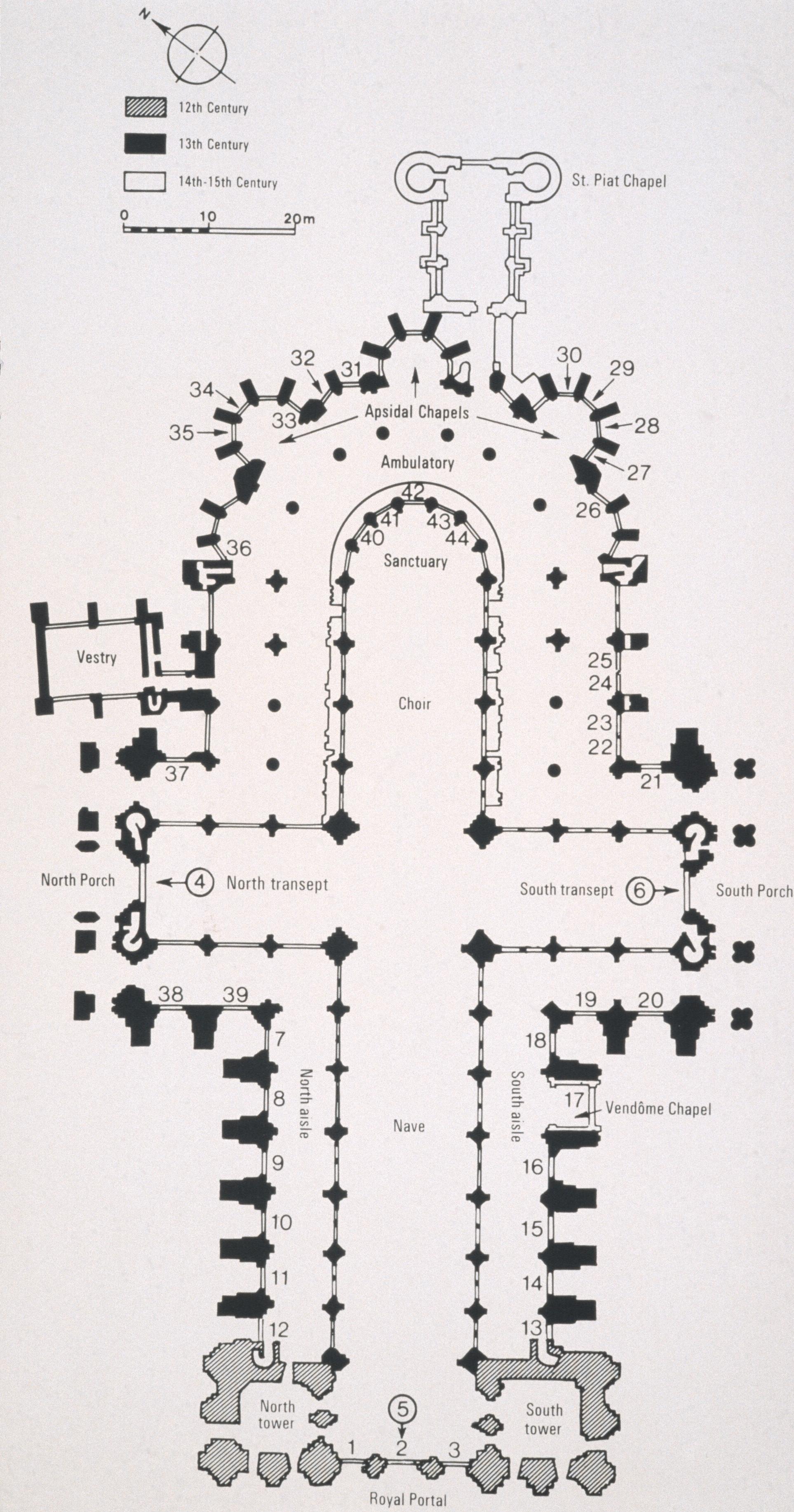

I have now shown you stained glass and stained glass windows in England and in Italy, and the moment has come to make a pilgrimage to France, to the city which more than any other has a right to be called the ‘Mecca’, of all those who make pilgrimages to see stained glass: Chartres, a tiny town dominated, as you can see, by its cathedral, which was rebuilt in Gothic style in the first three decades of the thirteenth century, after a disastrous fire destroyed its predecessor in 1194:

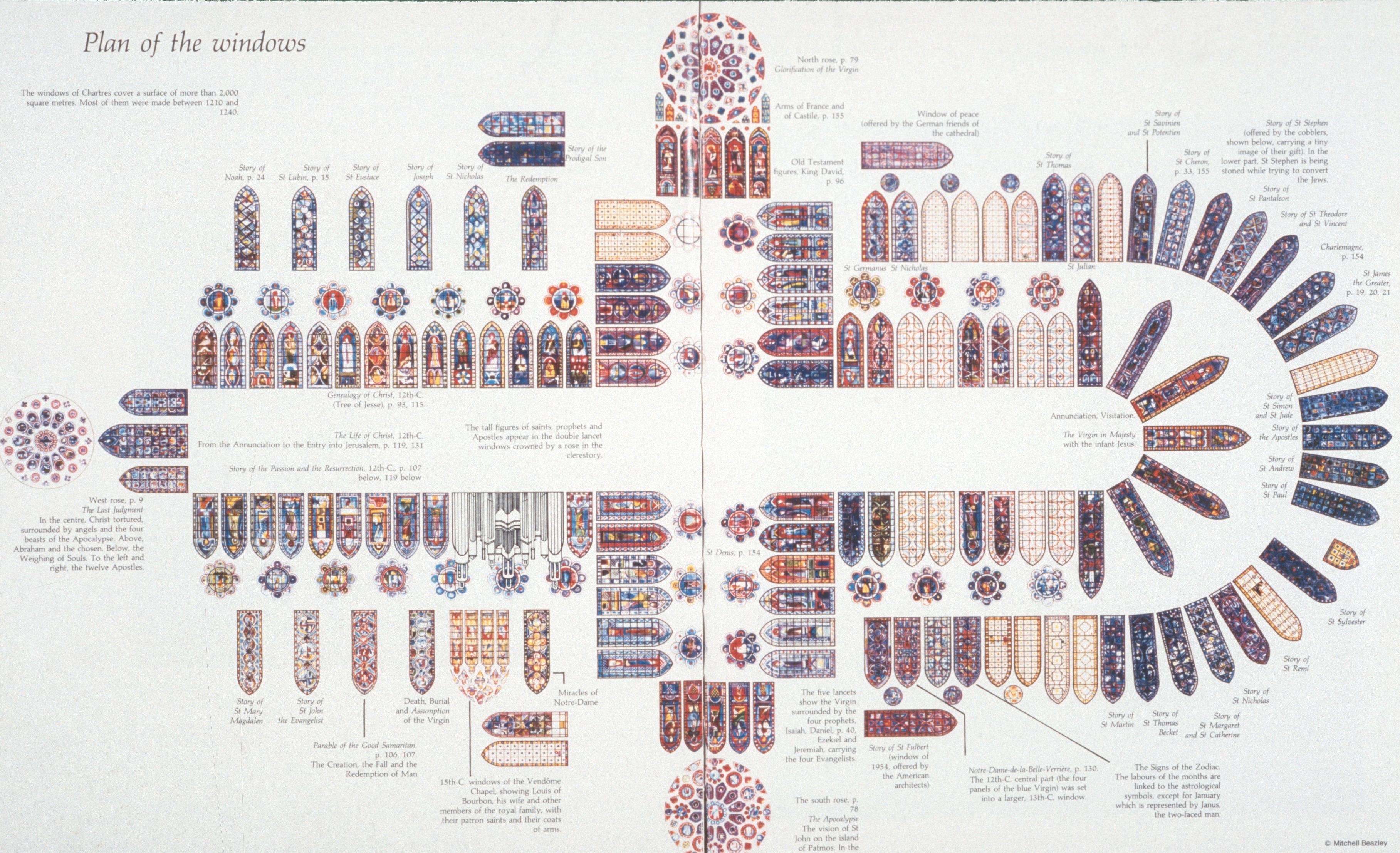

It has three portals, which are covered in row upon row of sculptures, so famous that people often speak of Chartres Cathedral as the ‘Acropolis’ of France. But what interests us in this lecture are the nave and the two aisles, which were built to hold the huge windows that were designed to be filled with colour. There used to be no fewer than 176 such windows in this one building, and it is almost miraculous that no fewer than 145 of them survive, laid out as you can see in this plan of the cathedral:

We will look at just five of them—first, two of the ‘vertical’ windows; and then, after a pause to study some texts from the Bible, we shall come back to the three rose windows, North, West and South, which will prepare us for the lecture’s finale.

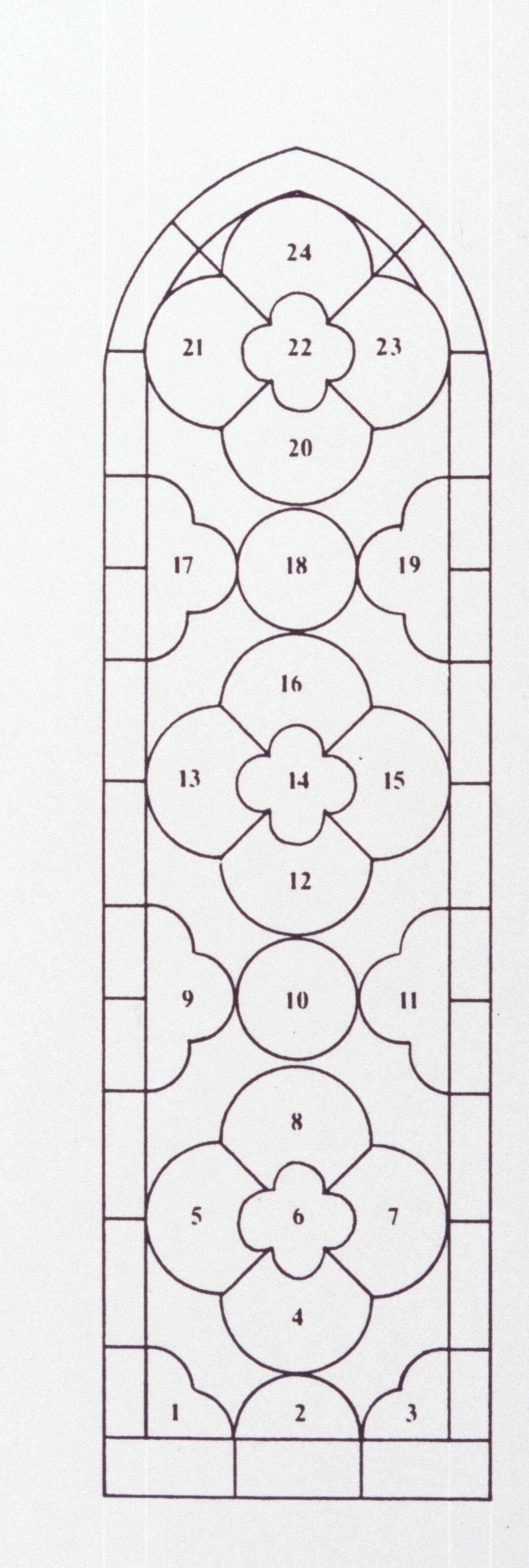

The first of the vertical windows is divided into 24 compartments, grouped into three ‘flowers’, six ‘leaves’, and two ‘buds’, while the lower zone is given over to the Parable of the Good Samaritan.

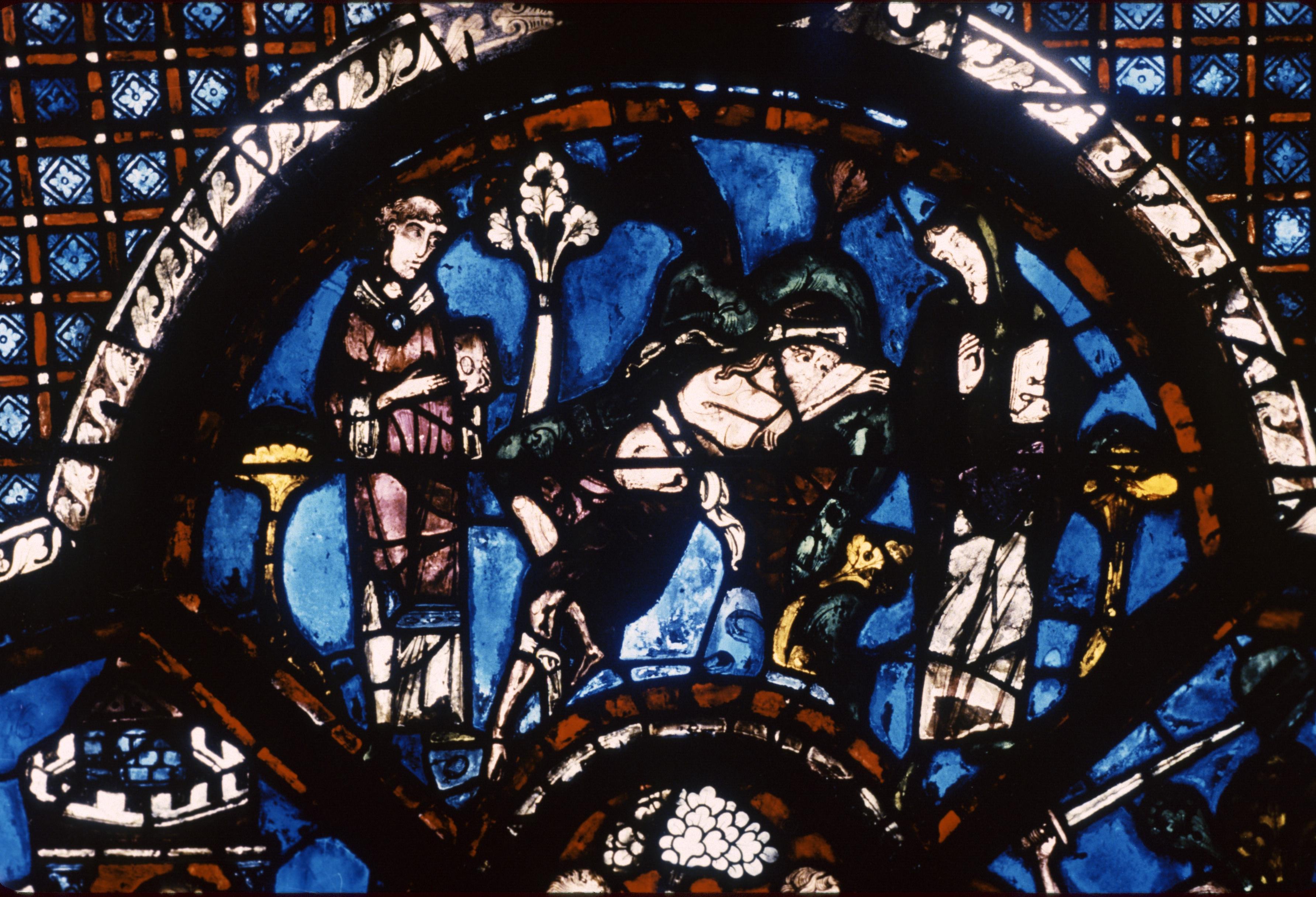

In the vertical ‘petal’ to the left, you can see the unnamed traveller, ‘a certain man’, who is emerging confidently from the Gate of Jerusalem under a cloudless blue sky, to make the journey to Jericho.

In the quatrefoil at the centre of the flower (below on the left), two thieves, dressed in green, are lying in ambush on a hill which is as red as blood:

To the right, the thieves are beating the traveller with huge clubs, while an accomplice is stripping him of all his clothes, as the parable specifies. The thieves will leave him half dead (as our translations say) or ‘half alive’, semivivus, as the Latin says, at the edge of the road.

And finally, it is at the edge of the road that we find him in the upper ‘petal’ (below), in the scene where the Priest and the Levite will pass by on the other side of the road, silhouettted against the intense blue of the sky:

What I have shown you are four scenes, set in four different geometrical shapes. The colours used were very intense, saturated, and their function was part naturalistic, part symbolic. The story is told with the utmost clarity, confined to the essentials. In all these respects, the windows make me think of Dante’s terzinas, which are bound together by the rhymes—ABA, BCB, CDC and so forth, in a strict pattern—where all the lines must have neither more nor less than eleven syllables, but the syntactic structures varied and flexible, and the rhyme sounds and rhyme words are deployed like patches of intense colour, some of them being (in Dante’s own terminology) ‘sweet-tasting’, like the blue, or ‘sharp-tasting’, like the reds or greens.

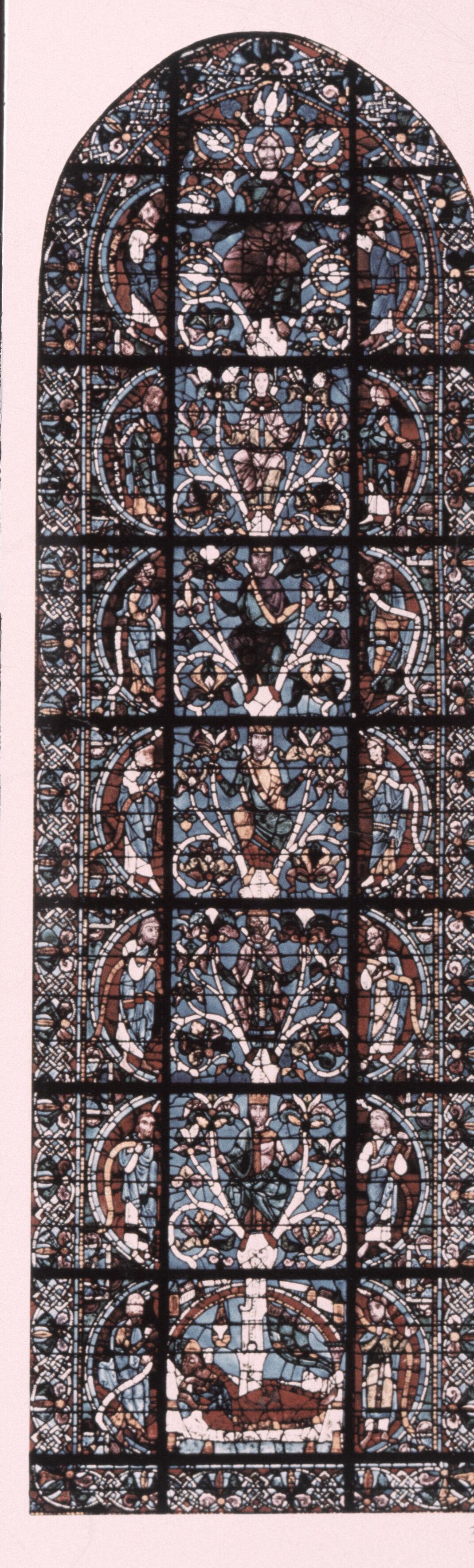

The second vertical window at Chartres we shall look at is placed over the West Portal, and is earlier in date—in fact, it goes back to the twelfth century, before the great fire. It looks like a ladder with seven rungs, or like the kind of wooden palier, that gardeners put on the south-facing walls of their orchards to support an exotic fruit tree. And as you can see in the detail, its frame does support a single tree—a lofty, white one which is growing from the loins of Jesse, who lies asleep wrapped in his red cloak on white sheets, spread over a green bed:

It is a so-called ‘Jesse tree’, a genealogical tree showing the ancestors of Christ, to whom I shall return in my fifth lecture. The trunk carries upwards the seed of the royal house of David, through the successive generations of the Kings of Judah, who are flanked (below left) in each case by the prophets who foretold the birth of the Messiah ‘from the line of David’. At the very top of the tree (below right), we find not Joseph (as St Matthew reports in the opening of his Gospel), but Mary and Jesus, (as the perspective of the New Testament requires), with Christ is represented not as the Messiah of the Jewish tradition, the ‘anointed king’, but as the son of God, the king of the world, and the Saviour of the whole of mankind:

When I look at this window as a whole, with its regular geometrical forms and the varying play of ‘colour and light’, it makes me think of certain cantos in the Paradiso, cantos 6, 11 and 12 for instance, where Dante narrates, terzina by terzina or scene by scene, the main events in the conquest of the world by the Romans, or the main events in the lives of St Francis and St Dominic.

The two windows you have looked at really are a visual correlative of Dante’s poem; of the economy, and the density, which come from his use of the terzina as a self-contained unit, of the interlocking effect of the rhymes, and the different ‘colours’ suggested by their contrasting sounds—all the features that make Dante’s way of telling a story so different from what you find in his classical models, Virgil and Ovid, or in the Bible, or in medieval romances.

We shall come back to Chartres presently, to look at the three rose windows—but before we do, we must have a quick look at the ‘source’ of the images, the ‘fountain head’ which ‘feeds’ not only Chartres and the Paradiso, but all medieval representations of Paradise; namely, the Book of Revelation, also known as the Apocalypse, by St John the Evangelist.

My plan is to remind you of certain key passages which will already be familiar from the King James Bible, and to give you the Latin which Dante knew, that of Saint Jerome’s Vulgate. I want you to concentrate in particular on the italicisations, because they call attention to those words which Dante uses to speak of the visibilia propria, ‘lo colore e la luce’.

In the opening chapter of Revelation, St John tells how he saw ‘in the spirit’ a ‘Throne set in heaven’, and around this throne 24 other thrones, on which there sat ‘24 elders’. The elders were dressed in white garments and had on their heads crowns of gold, and in front of the throne, ‘there was a sea of glass, like crystal’:

Et in conspectu sedis tamquam mare vitreum simile crystallo; et in medio sedis, et in circuitu sedis quattuor animalia plena oculis ante et retro.

(Apocalypsis Johannis Apostoli, 4, 6–7)

There were also the ‘four living things’, in Latin, quattuor animalia—lion, ox, man and eagle—always understood as symbols of the four Gospels, or four Evangelists, and in addition, the Lamb, the Lamb of God, always understood as Christ; though in the event, there is no trace of animals or lamb in Dante’s celestial Paradise:

Et vidi et ecce in medio throni et quattuor animalium, et in medio seniorum, Agnum stantem tamquam occisum…

(Apocalypsis Johannis Apostoli, 5, 6)

From these short texts in the early chapters, I jump now to chapter 21, and to the fart more substantial description of the Heavenly City:

Ego sum alpha et omega, initium et finis; ego sitienti dabo de fonte aquae vivae, gratis’.

Et sustuli me [sc. angelus] in spiritu in montem magnum et altum, et ostendit mihi civitatem sanctam Hierusalem, descendentem de caelo a Deo, habentem claritatem* Dei. Lumen eius simile lapidi pretioso tamquam lapidi jaspidis sicut cristallum. Et habebat* [civitas] murum magnum et altum habens portas duodecim

…

Et erat structura muri eius ex lapide jaspide; ipsa vero civitas auro mundo, simile vitro mundo; fundamenta muri civitatis omni lapide pretioso ornata

…

Et platea civitatis aurum mundum tamquam virtum perlucidum.

…

Et civitas non eget sole neque luna ut luceant in ea, nam claritas Dei illuminavit eam et lucerna eius est Agnus; et ambulabunt gentes per lumen eius.

…

Et ostendit mihi fluvium aquae vitae splendidum tamquam cristallum, procedentem de sede Dei et Agni…et ex utraque parte fluminis lignum vitae, adferens fructus duodecim…

(Apocalypsis Johannis Apostoli, 21, 10–12, 18–19, 21, 23–4; 22, 1–2; 21, 5)

He who sat on the Throne said: “I am Alpha and Omega, the beginning and the end, to anyone who thirsts, I shall give as a gift from the fountain of living water”. The angels showed me the Holy Jerusalem descending from Heaven, from the presence of God, which had the “glory”, the radiance of God, and its light was like that of a most precious stone, like a jasper, like crystal. The city had a great and high wall, and it had twelve gates.

…

And the wall was made of jasper; and the City was of pure gold, like pure glass; and the foundations of the wall were adorned with every kind of precious stone. [The author gives a wonderful list of these, including jasper, sapphire and emerald.]

…

And the square [platea, the ‘piazza’] of the city was of pure gold, like transparent glass.

…

The City hath no need of the sun or the moon, that they may shine out in it, because the “glory” of God illuminates it, and its lantern [lucerna] is the Lamb; and the peoples shall walk in its light.

…

The Angel showed me a pure river of the Water of Life, as clear as crystal, which came from the Throne of God and of the Lamb…on both sides of the river there was the Tree of Life, which bears twelve fruits…

The last description, of the River, is highly important for Canto 30 of Paradiso,

which is why I have quoted it out of order from another chapter. Yet together with the prior passages, the above gives you a generous and typical sample of the words and images that recur obsessively in Revelation, and which will be very common in Dante’s Paradiso.

We have seen gloria and claritas, lumen and lux, and lucerna, illuminare and lucère, lapis pretiosus (of all types), aurum mundum—and I am sure you will have been especially struck by the words that make us think of our cathedrals, ‘crystal and glass’, crystallum and vitrum.

When one reads phrases like sicut cristallum tamquam vitrum perlucidum, and above all, tamquam mare vitreum, ‘like a sea of glass’, it is impossible not to think of Chartres—or of the Abbey of St Denis in Paris, and its abbot in the year 1140, Suger, who made the conscious decision that he would realise here on earth, in his abbey, in coloured glass, the Vision of John the Evangelist, causing to ‘descend from heaven the Holy City which had the glory or claritas of God’,

So let us return to Chartres, and get a general idea of the layout of the stained glass in the three rose windows. I should clarify that I have chosen Chartres simply because there are three of these circular windows, all of the very highest quality; however, the points I want to make are in principle valid for all such windows, and it is no part of my argument that Dante must have visited the cathedral of Chartres itself. Reproduced below, then, is the window over the North Portal, alongside a plan of the building:

What I want to do in the coming paragraphs is prepare you to think about some possible connections between these circular windows—‘rose windows’, as we call them today—and what Dante called the ‘general form of heaven’, ‘la forma general di Paradiso’, as he described it in cantos 30 and 31.

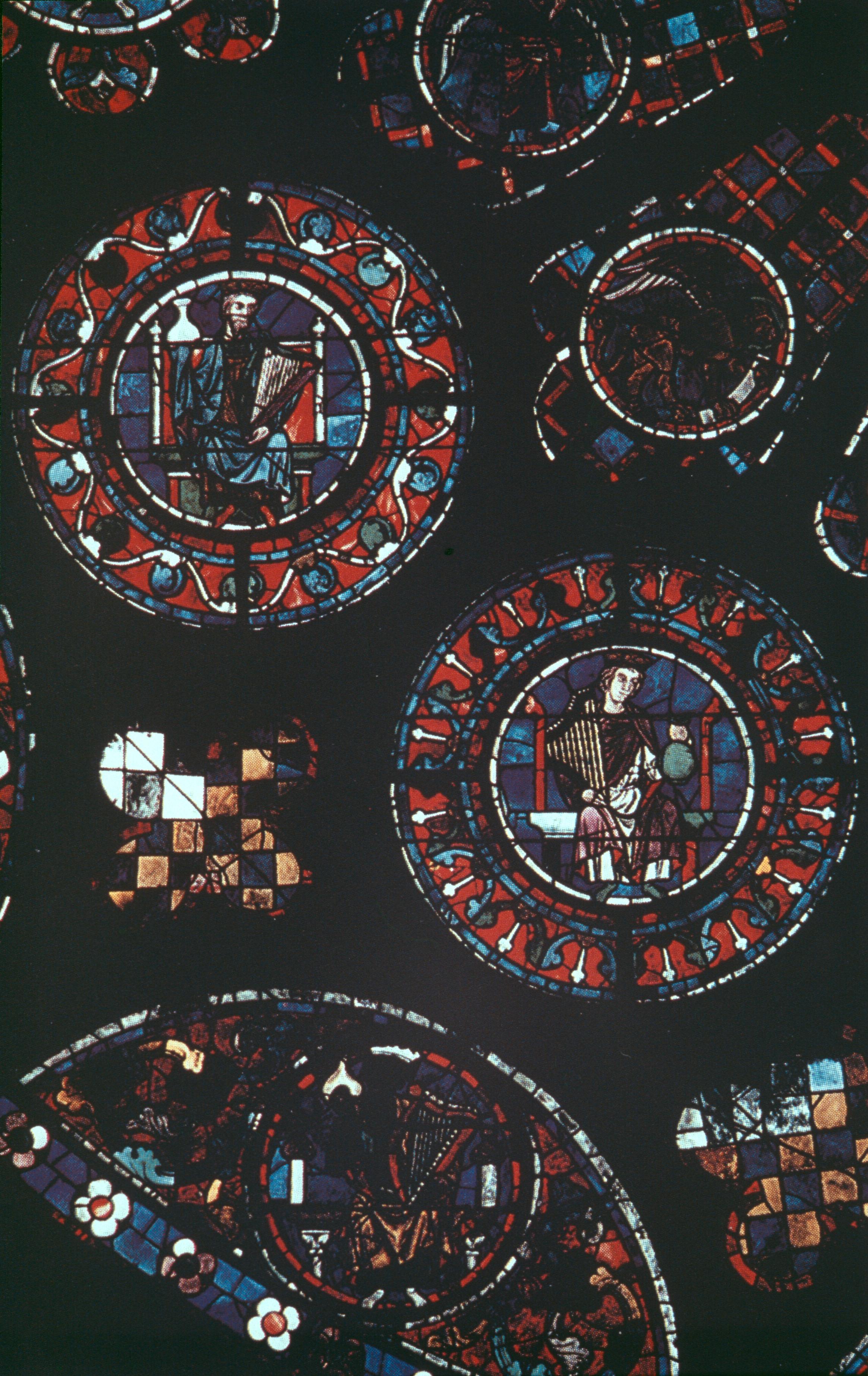

The one over the north Portal, pictured, presents the same characters that we saw in the Tree of Jesse. There are twelve squares, and they contain images of the twelve Kings of Judah; these are flanked, in the semicircles, by the twelve prophets, the so-called minor prophets, who foretold the coming of the Messiah. In the centre, you can see the Virgin Mary with the Christ Child, surrounded by twelve ‘parachutes’ or segments, representing angels or doves, as you can see better in the following detail:

We can examine them in order, moving outwards from the centre: Mary and Jesus, surrounded by lilies; doves; a King of Judah and a Prophet; and larger lilies.

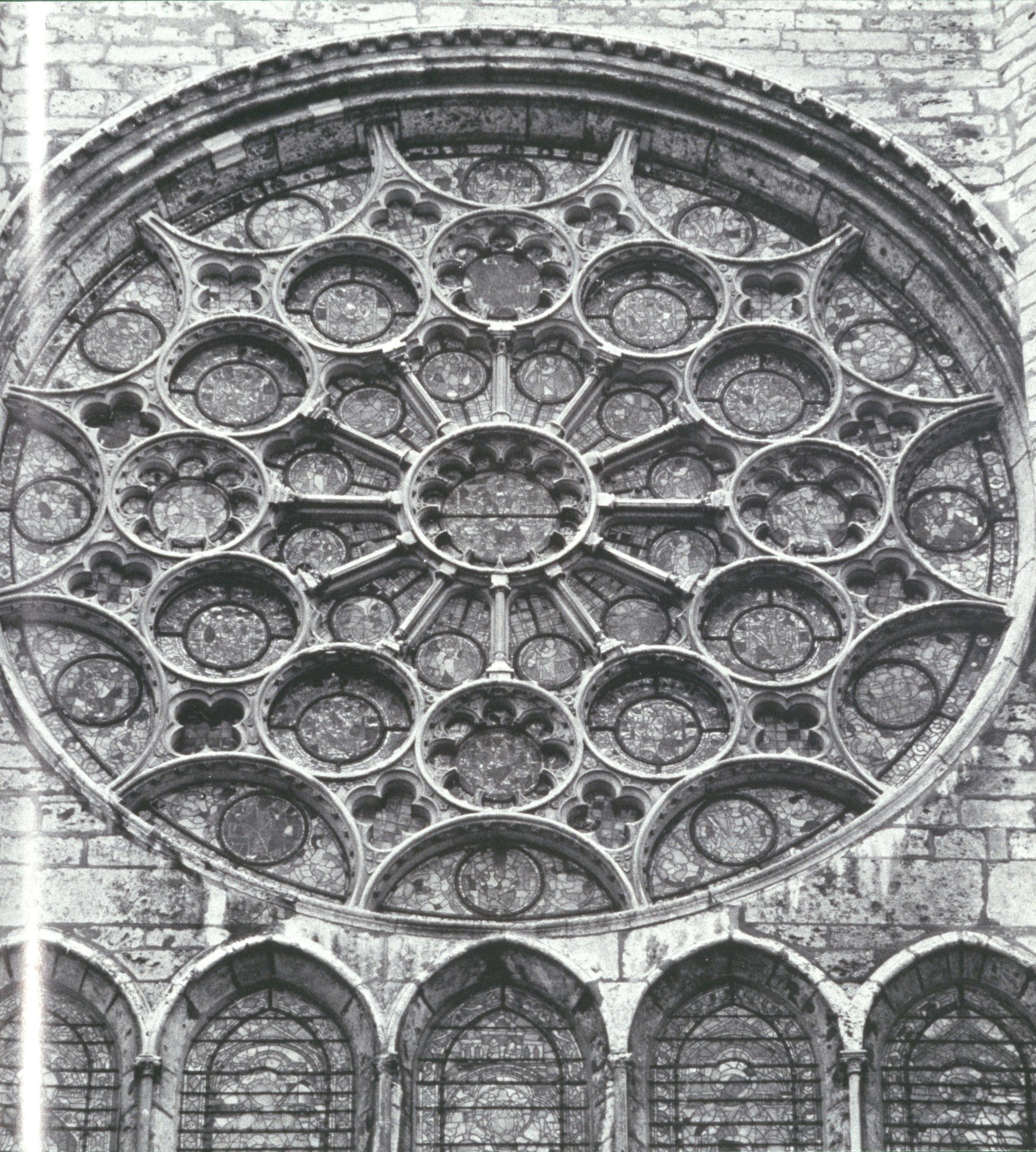

We move on now to the West Front, pictured below both from the outside and the inside (and where I would ask you to note the layout of the windows below the rose):

In the centre of the rose is the figure of Christ as Judge, who is surrounded by the four animalia, who are separated by pairs of angels. Moving now to the middle circle, in the lower half are the twelve Apostles, presided over by Abraham, who is flanked by Cherubim; in the outer circle, above, there is a ‘flying multitude’ of angels carrying the instruments of Christ’s Passion, and blowing trumpets to waken the dead for the Last Judgement.

Finally, let us pass to the South Rose, above the South Portal, where you can clearly pick out the concentric circles in the stone work, even without the colours that you see inside:

Once again, the centre is taken up with the figure of the Son of Man as seen in Revelation, surrounded by the four animalia alternating with angels, as in the West Window. This time the animalia and angels are surrounded, in the circles and in the semicircles, by the twenty-four elders, seniores—though they are not dressed in white, and are carrying musical instruments, which makes me think of a phrase in Dante, the ‘circulated melody’, ‘circolata melodia’.

Between the circles and the semi-circles is the coat of arms of the donor, the Count of Dreux, which I have picked out in this detail, which also shows some of the seniores and their instruments:

I come now to the last part of my lecture, in which I am going to take you through some lines from cantos of 30 and 31 of Paradiso. I see these lines as forming a kind of ‘Prelude and Fugue’, composed on themes derived from the Bible, and from the traditional iconography of the Last Judgement that Dante could have seen in frescos,

in manuscripts, or, just possibly, in the great circular windows we call ‘rose windows’.

«Noi siamo usciti fòre

del maggior corpo al ciel ch’è pura luce:

luce intellettual, piena d’amore;

amor di vero ben, pien di letizia;

letizia che trascende ogne dolzore.

(30, 38–42)

“We have gone beyond— from greatest sphere to heaven of pure light,

light of the intellect, light full of love,

love of the true good, full of ecstasy,

ecstasy that transcends the sweetest joy.” (The edition used here is that of F. Sanguineti, 2001; the translation is that by Mark Musa for Penguin Classics.)

At the point when we pick up the story, Dante and Beatrice have passed beyond the outer rim of the ‘primum mobile’ into the Empyrean, which Beatrice describes as a heaven of ‘pure light’, a light that is ‘intellectual’ (not accessible to the senses), filled with supreme love, joy and sweetness.

Così mi circonfulse luce viva,

e lasciommi fasciato di tal velo

del suo fulgor, che nulla m’apariva.

«Sempre l’amor che queta questo cielo

accoglie in sé con sì fatta salute,

per far disposto a sua fiamma il candelo».

(30, 49–54)

…so glorious living light encompassed me,

enfolding me so tightly in its veil

of luminance that I saw only light.

“The Love that calms FIXME: complete the translation

The first thing that happens is that Dante is engulfed and enfolded by a ‘living light’, a flash of lightning, (‘fulgore’), paradoxically forming a ‘veil’ before his eyes of such intense brightness that he can see nothing whatsoever, not even his guide, Beatrice. Immediately, however, her voice comes to reassure him, explaining that this is no more than the greeting (‘salute’) given to every soul as it arrives in the Empyrean, tempering it to withstand the light of God’s glory, by which light we shall ‘see’ God.

Non fuòr più tosto dentro a me venute,

Queste parole brevi, ch’io compresi

Me sormontar di sopr’a mia virtute;

e di novella vista mi raccesi

tale, che nulla luce è tanto mera,

che gli occhi miei non si fosser diffesi;

e vidi lume in forma di rivera

fulvido di fulgore, intra due rive

dipinte di mirabil primavera.

(30, 55–63)

No sooner had these brief, assuring words

entered my ears than I was full aware

my senses now were raised beyond their powers;

the power of new sight lit up my eyes

so that no light, however bright it were,

would be too brilliant for my eyes to bear.

And I saw light that was a flowing stream,

blazing in splendid sparks between two banks

painted by spring in miracles of color.

Dante is immediately conscious of an increase in his own power of sight, an ‘upgrade’ of such magnitude that he feels that no light whatever could now overpower his eyes and dazzle or blind him.

Di tal fiumana uscia<n> faville vive,

e d’ogne parte si mettea<n> nei fiori,

quasi rubino che oro circoscrive;

poi, come inebriate da li odori,

riprofondavan sé nel miro gurge,

e s’una entrava, un’altra n’uscia fòri.

(30, 64–9)

Out of this stream the sparks of living light

were shooting up and settling on the flowers:

they looked like rubies set in rings of gold;

then as if all that fragrance made them drunk,

they poured back into that miraculous flood,

and as one plunged, another took to flight.

Anco soggiunse: «Il fiume e li topazi

ch’entrano ed escono e ’l rider de l’erbe

son di lor vero u<m>briferi prefazi.

(30, 76–8)

…and then she said: “The stream, the jewels you see

leap in and out of it, the smiling blooms,

are all prefigurations of their truth.

And what can he see with this ‘novella vista’? He sees light, in the form of a ‘river’—flashing and sparkling light, flowing between two ‘banks’ which are, as it were, ‘painted’ with all the brilliantly coloured flowers of spring. Having given this general preview, as he often does, Dante then ‘fills out’ his description—combining no fewer than three images: sparks leaping up from a fire, the flowery banks of a river, and sparkling rubies and topazes set in the gold of a brooch or ring.

‘Living sparks’ are coming out of the ‘river’, settling down on the ‘flowers’ on both banks, becoming intoxicated with the fragrance of these flowers and then diving back into the swirling waters; as one spark leaps up, another plunges back. Or—switching the image and reversing the order—the ‘topazes’ are entering the river and ‘issuing’ from it. All these, however, we are warned, are no more than ‘shadowy anticipations of the truth’.

Fassi di raggio tutta sua parvenza

riflesso al sommo del mobile primo,

che prende quindi vivere e potenza.

E come clino in acqua di suo imo

si specchia, quasi per vedersi adorno,

quand’è ne l’erbe e nei fioretti opimo,

sì, soprastando al lume intorno intorno

vidi specchiarsi in più di mille soglie

quanto di noi là sù fatto à ritorno.

E se l’intimo grado in sé racoglie

sì grande lume, quanta è la larghezza

di questa rosa nelle estreme foglie!

La vista mia ne l’ampio e ne l’altezza

non si smariva, ma tutto prendeva

e ’l quanto e ’l quale di quella alegrezza.

(30, 115–20)

And its expanse comes from a single ray

striking the summit of the First Moved Sphere

from which it takes its vital force and power.

And as a hillside rich in grass and flowers

looks down into a lake, as if it were

admiring the reflection of its wealth,

so, mirrored, tier on tier, within that light,

more than a thousand were reflected there,

I saw all those of us who won return.

And if the lowest tier alone can hold

so great a brilliance, then how vast the space

of this Rose to its outer petals’ reach!

And yet, by such enormous breadth and height

my eyes were not confused; they took in all

in number and in quality of bliss.

At this point, I have made a huge cut in the text, twelve terzinas, to where Dante explains that, thanks to a further increase in his power of sight, he saw the river turn into a circular lake, and the two banks into the hills surrounding it. Here we begin to understand that what the pilgrim had seen as ‘flowers’ and ‘sparks’ are the two ‘courts of heaven’; respectively, the souls of the blessed, who remain seated like flowers on the bank, and the angels, who are flying constantly to and fro like sparks, between the throne of God and the thrones of the blessed.

Standing back from the unfolding of the spectacle in the story, Dante the poet describes what might be called a huge ‘cone’, or ‘amphitheatre’ of light, formed when the rays of direct light, flowing from God, are reflected back from the convex surface of the ‘primum mobile’, because it is these reflected rays that create more than a thousand rising circles of thrones for the souls of the blessed. Yet Dante does not speak either of ‘cones’ or ‘amphitheatres’—instead, with a metaphorical sleight of hand, we are invited to imagine this ring of enclosing the circular stage at its centre as being like the petals of a rose, surrounding the yellow stamens at its core.

We are asked to imagine how vast this ‘rose’ must be, and then to imagine the power of Dante’s ‘novella vista’ which can take in the ‘amplitude’ and the ‘height’,

and also the ‘quantity’ and ‘quality’ of the joy of Heaven, ‘quella alegrezza’.

Nel giallo de la rosa sempiterna,

che si digrada e dilate e redole

odor di lode al sol che sempre verna,

qual è colui che tace e dicer vole,

mi trasse Beatrice, e disse: «Mira

quant’è il convent de le bianche stole!

Vedi nostra città quant’ella gira;

vedi li nostril scanni sì ripieni,

che poca gente più ci si disira.»

(30, 124–32)

Into the gold of the eternal Rose,

whose ranks of petals fragrantly unfold

praise to the Sun of everlasting spring,

in silence—though I longed to speak—was I

taken by Beatrice who said: “Look

how vast is our white-robed consistory.

Look at our city, see its vast expanse.

You see our seats so filled, only a few

remain for souls that Heaven still desires.”

Beatrice now takes Dante down to the centre and the bottom, to the ‘yellow’ of this sempiternal’ ‘rose’, and she invites him to gaze on the immense size of this celestial ‘convent’, in which the seats in the sanctuary (so to speak) are almost completely filled with the ‘white habits’ of the monks and nuns. Notice the extraordinary density of the metaphors in the first terzina here: the rose goes up in steps, getting wider as it goes, and it gives off (‘is redolent with’, ‘redole’) a fragrance (‘odore’), which is the only way that a real rose can give praise (‘lode’) to the sun from which it derives its life and power.

In forma dunque di candida rosa

mi si mostrava la milizia santa

che nel suo sangue Cristo fece sposa…

(31, 1–3)

So now, appearing to me in the form

of a white rose was Heaven’s sacred host,

those whom with His own blood Christ made His bride…

One final jump now, to end with the first three lines of the next canto, which summarise most of what I have been trying to get across about the souls of the blessed on their thrones.

The overall impression should be of music in what you have read; the words that indicate light—light that is ‘living’, ‘fulgurating’, coruscating—and the words that relate to the ‘circular figure’, which Dante compares to a rose with its yellow centre and its row upon row of petals. From this, you can see why none of his illustrators could do anything with Dante’s poetry in final cantica, and why the only possible analogues between the visual arts and Dante’s Paradiso would be the great glass windows of cathedrals like Canterbury or Chartres.

FIXME: Deal with the following:

[Again, as with the Petrarch lecture, the end of the document contained various offcuts and abandoned drafts for passages; in this case they do not seem to have been used in the final version in any recognisable form. I have edited them below in case you wish to reinterpolate them into a second draft of this lecture. As they are less contiguous than those in the Petrarch lecture, nor have I attempted to stitch them together.]

In the following canto, it will fall to Solomon to explain that on the day of the Last Judgement, after the Resurrection of the Dead, the glorified bodies of the blessed will not dim their radiance, but will make them even more radiant than they are now:

Come la carne glorïosa e santa

fia rivestita,

…s’accrescerà ciò che ne dona

di gratüito lume il sommo bene,

lume ch’a lui veder ne condiziona;

onde la visïon crescer convene,

crescer l’ardor che di quella s’accende,

crescer lo raggio che da esso vene.

(14, 43–51)

When the garment of our flesh, made glorious and holy,

shall be put on again…/ that which the Supreme Good give us

of his light of grace will be increased,

[this being] the light that “conditions” us to see him;

so our power of sight must increase,

so too must the ardour that is kindled by sight,

so too the ray that issues from that ardour.

This is one of the most beautiful and ‘radiant’ passages in the whole cantica, and the poor miniaturist is, so to speak, totally ‘eclipsed’:

He shows us the resurrected bodies; he shows us the ‘gratuito lume’, alias the ‘light of grace’, or the ‘light of glory’(lumen gratiae, or lumen gloriae); but he cannot begin to convey what Dante is saying about the ‘glorified body’, that ‘body made glorious’ which will be a ‘lucent body’, even more brilliant than these spirits who have appeared to Dante, and who have surpassed the lucent body of the sun which is at the very top of the scale, or ‘ladder’, of the light which appears to our senses.

We also realise the sheer impossibility that any visual artist working in any medium other than film could convey what Dante was trying to evoke in our imaginations, because, as we shall see, he is concerned with changes, with processes, with the gradual unfolding of the spectacle and his gradual understanding of what we can think of as his Revelation; and this he achieves by constantly focussing on his own perceptions, and on the many distinct stages by which his power of vision was strengthened, to enable him to make out ‘the general form of Heaven’.

–

Italians call them ‘rosoni’, by the way, ‘big roses’; but there is no evidence as far as I know that this expression was used in Dante’s day. However, when you look at the stone ‘petals’, even from the outside, one wonders if a pilgrim who was returning from Assisi, and was trying to describe this window to someone at home, if casting around for some familiar object with which to compare it, might not have started with a ‘wheel’, and got as far as a ‘rose’.

–

Perhaps I should have gone on, and reminded you of the woman clothed in the sun (‘mulier amicta sole’), or the description of the feet of the Son of Man, which shone like bronze in the blazing furnace (‘in camino ardenti’).

–

(By the way, the verb ‘circunfulse’ is a Latinism equivalent to circumfulsit, which is the verb used in the Latin Bible to describe the bright light that threw St Paul to the ground on the road to Damascus, and left him blind.)

–

And so we pass to the next stage, and to yet another instance of the principle that ‘by His light we see the Light’; once again Dante must expose his eyes to the very light that he wants to be able to see, but this time the image is blended with that of Baptism, when we are immersed in the Holy Water that will wash away the stain of Original Sin and make us better, and with that of drinking the Water of Grace. Dante’s eyelids drink of the water, and immediately the images change.

–

[the following section has cues for a number of slides which are not present in the carousel I had to scan; and will need reinserting]

Still faithful to the principle that by his light do we see Light, Dante now appeals to the Splendour who is God for the power to express the triumph of the true kingdom, and then goes back over the ground he has covered.

He does so firstly by giving us the concepts. God the creator, who is Light of his very nature, sends out a light which enables Man—who is his creature, his creation—to see Him in his essence (which is Light). In this way, he satisfies our concreated desire for the supreme Good, which alone can grant us peace. This divine light extends in a circular or spherical figure (just as Grosseteste said it must),

and the circumference of this sphere is far greater than that of the sun.

More precisely, this sphere of light which is the court of heaven is a reflection back from the outermost of the physical heavens, the so-called ‘primum mobile’ of the ray of divine light, from which this heaven receives the life and energy which it relays to all the inner heavens and the earth below.

These lines, I should perhaps add, are bound to dazzle the minds of those who have not studied medieval philosophy and theology, but are in themselves as clear and as ‘lucent’, as they are beautiful to the ear.

And now we come back to similes and to description, the Word made Flesh, so to speak.

–

[so too here, there are no slides to accompany the cues]

Or in the main church of San Vitale, where the figures at the court of the Emperor Justinian shine out no less brightly than the angels at the ‘court’ of ‘that Emperor who reigns on high’, ‘quell’imperador che lassù regna’. Or, again, still at Ravenna, in the basilica closer to the coast, St Apollinare in Classe, where we can see this Cross inscribed in a circle.

When Dante arrives in the Heaven of Mars, formed by the lights of the souls who have descended to greet him there, he compares its appearance to that of the Milky Way. Although Dante also says it had the shape of a Greek cross, with equal arms inscribed in a circle, and although the souls somehow simulate the body of Christ on this cross of lights, I am not the first person to suspect that Dante’s inspiration for this miraculous sight was his memory of the basilica, which he recalls as being ‘near the pine grove on the shore of Classe’.

–

…beginning in this ‘petal’ here, where we see Christ telling the parable to his disciples within a frame of three colours, and some purely ornamental blue rectangles.

NOTES FOR PAT AND FOR MYSELF

- I have been somewhat selective in the images used, given the vast number of slides in the original presentation—those that are merely illustrative, rather than subject to discussion, have been omitted where it seems sensible and to not harm the sense on the page.

- The slide containing the passage from Convivio 3.9.6 (slide R4) has been left out, as the reader would presumably have lecture 1 at hand to refer to; if this does not end up in that lecture, or they are published separately, it can of course be reinserted.

- In the typescript body, during the initial discussion of Botticelli and Doré, there was a note to self to refer to Inferno 26 in any longer version.

- I have incorporated into footnote 2 your translations of the first two stanzas of the Italian quotation, as were read aloud—as a translation of the third stanza was missing, I have supplied my own; please do check and alter.

- As part of the general whittling down, I have left out the image of the sculptures at Chartres; again, if we want to reinsert this it is slide L23.

- Similarly I have left out the slide detailing the rhyme scheme of a terza rima, as it seems clear from the text and probably unnecessary in a print version (R28).

- The Fitzwilliam Illumination and Assisi rose window (L38 and 39) I have left out; something of a shame in the case of the former.

- As with the Petrarch essay, there were some leftovers at the end of the document which I have tried to edit into a usable state.

![Figure 5: (P_Pa_5) [caption required for Giotto fresco]](media/image5.jpeg)

![Figure 8: (P_Pa_8) Giovanni di Paolo, [FIXME: ref and possibly date needed]](media/image8.jpeg)

![Figure 10: (P_Pa_10) [FIXME: caption needed]](media/image10.jpeg)

![Figure 11: (P_Pa_11) Giovanni di Paolo, [FIXME: name of work needed]](media/image11.jpeg)

![Figure 12: (P_Pa_12) Giovanni di Paolo [FIXME: title needed]](media/image12.jpeg)

![Figure 13: (P_Pa_13) [FIXME: caption needed]](media/image13.jpeg)

![Figure 28: (P_Pa_28) Giovanni di Paolo’s [??] illumination of Paradiso 14](media/image28.jpeg)