On the left is a portrait of Lady Margaret Beaufort, a queen-mother, and foundress of my College at Cambridge, St John’s, who was born in the 1440s, in the same same decade as Botticelli, and who is portrayed here, posthumously, as she would have been shortly before her death in 1509. On the right is Pope Leo X, born in 1475, the same year as Michelangelo. He was thirty years younger than Botticelli, but would certainly have known him, since he was the second son of Lorenzo il Magnifico and a cousin of Botticelli’s best documented patron.

The books they are reading are sacred texts, a New Testament and a Book of Hours; the setting is noble, in keeping with their rank of the two readers and with the dignity of their reading matter. Their attitude is reverent—very much so in the case of Lady Margaret.

The books are sumptuously produced and expensive, status symbols, handwritten on parchment, beautifully decorated and illustrated by an artist concerned to ‘throw light on’—to ‘illuminate’—the meaning of the sacred text.

It is clear that the Pope is a connoisseur of the arts: he is using a lens to enjoy the illustrations, and his bell is as beautiful as his bible. There is every reason, too, to think that the Queen Mother took delight in the beauty of her book. But there is no contradiction, no incompatibility between the dignity of the room and its fittings, and the sacred text; nor between a spirit of reverence, and the enjoyment of images that are giving delight as well as aiding devotion and comprehension of the text.

Lady Margaret can be seen in the background of this group of images where, once again, you are looking at a woman reading reverently, in a noble setting. We might call her “Lady Catherine” (she used to be a lectrice in St John’s College), and over her shoulder, we can see that the book she is studying combines text and images—some lines from a poem, and a sumptuous illustration.

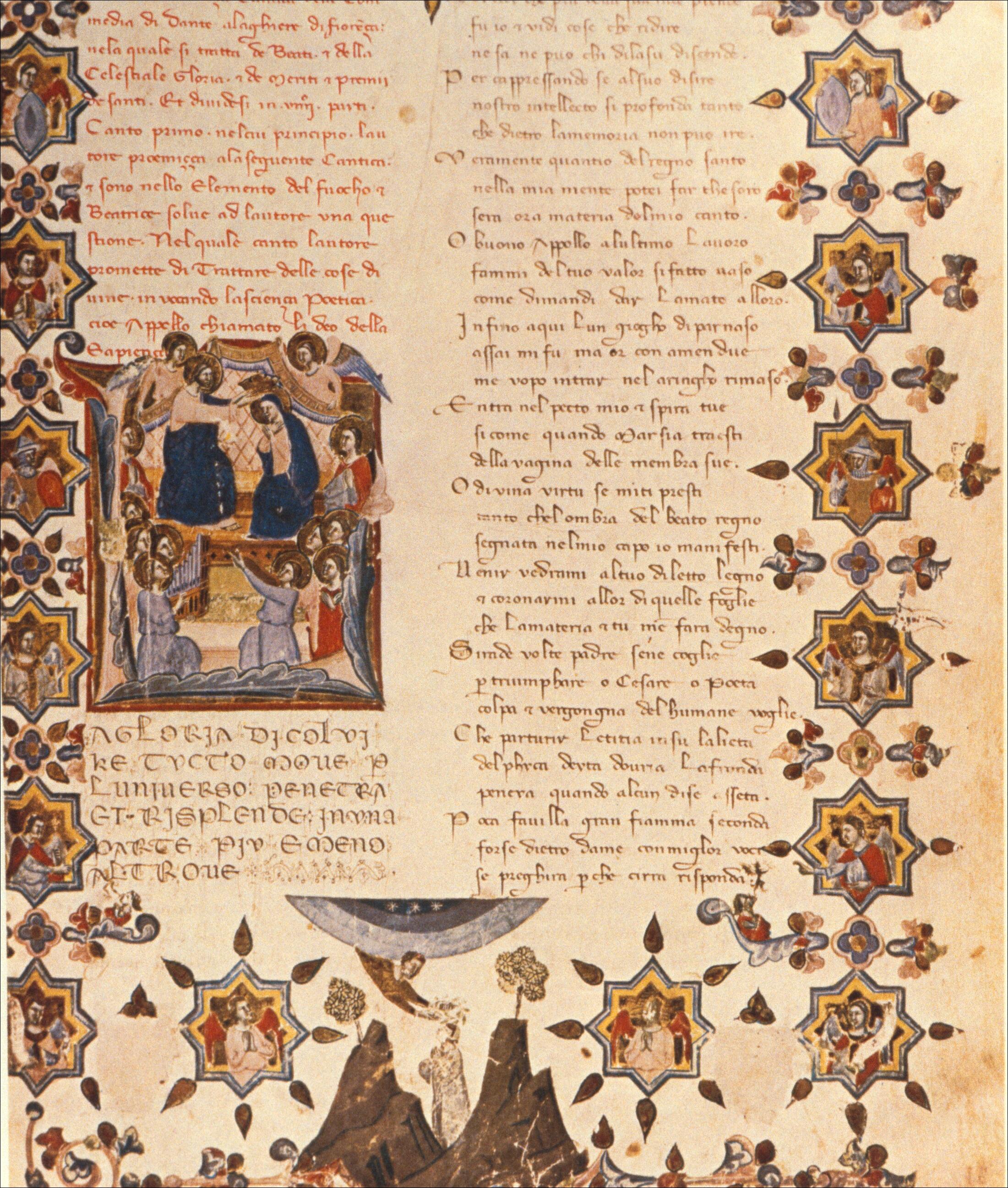

You will have already intuited the poem and its author. The text she is reading, intently, reverently, concerns the fate of the soul in the Christian vision of the afterlife; and it had become a classic in Botticelli’s Florence—almost a symbol of Florentine culture and of the superiority of Florentine over the other dialects of Italy. Within a few decades its ‘holiness’, and its status as a classic, would result in its being given a new title: not just the Comedy, as Dante himself had called his own poem, but The Divine Comedy, a punning title, implying that it is both ‘about sacred things’ and a ‘more-than-human’ achievement as a work of literature.

It is hardly surprising, then, that Dante’s poem should be treated like a Bible or a Book of Hours, that the text should be enhanced with painted images, which not only help to clarify the meaning of the text, but are beautiful in their own right, and that the reader should want to study the text in a noble setting, in a spirit of reverence, and to take delight in the beauty of the words and of the illustrations or decorations.

I have to tell you, however, that although the setting and the reader are real enough, the book you are looking at is only a virtual reality. What you are looking at is a life-size reconstruction, of how Botticelli’s illustrations to the Comedy would have been used and enjoyed—if only the artist had finished the job!

It is well known—not least due to the well publicised exhibition in 2001 at the Royal Academy—that some of the one hundred parchments sheets are lost.

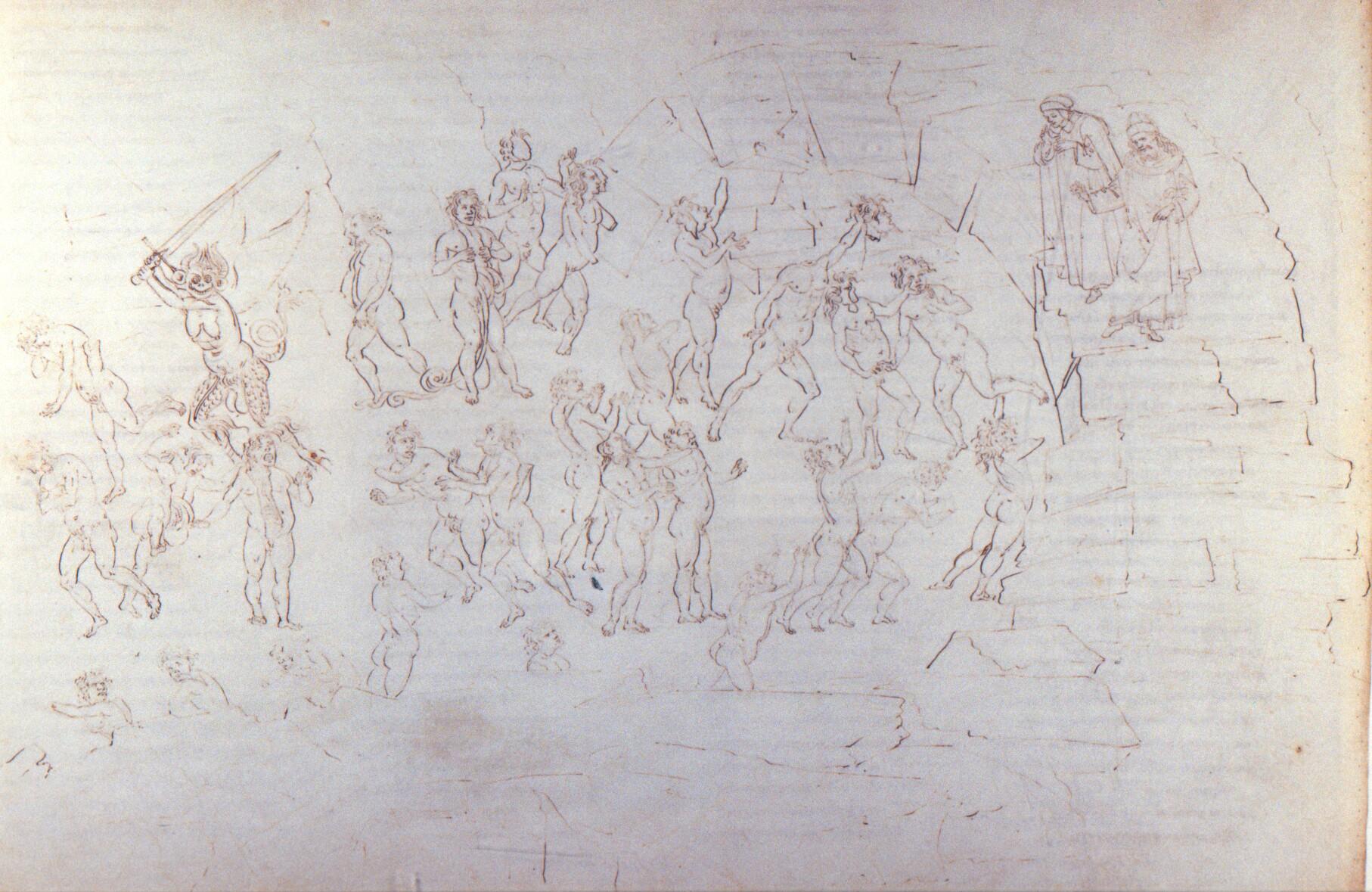

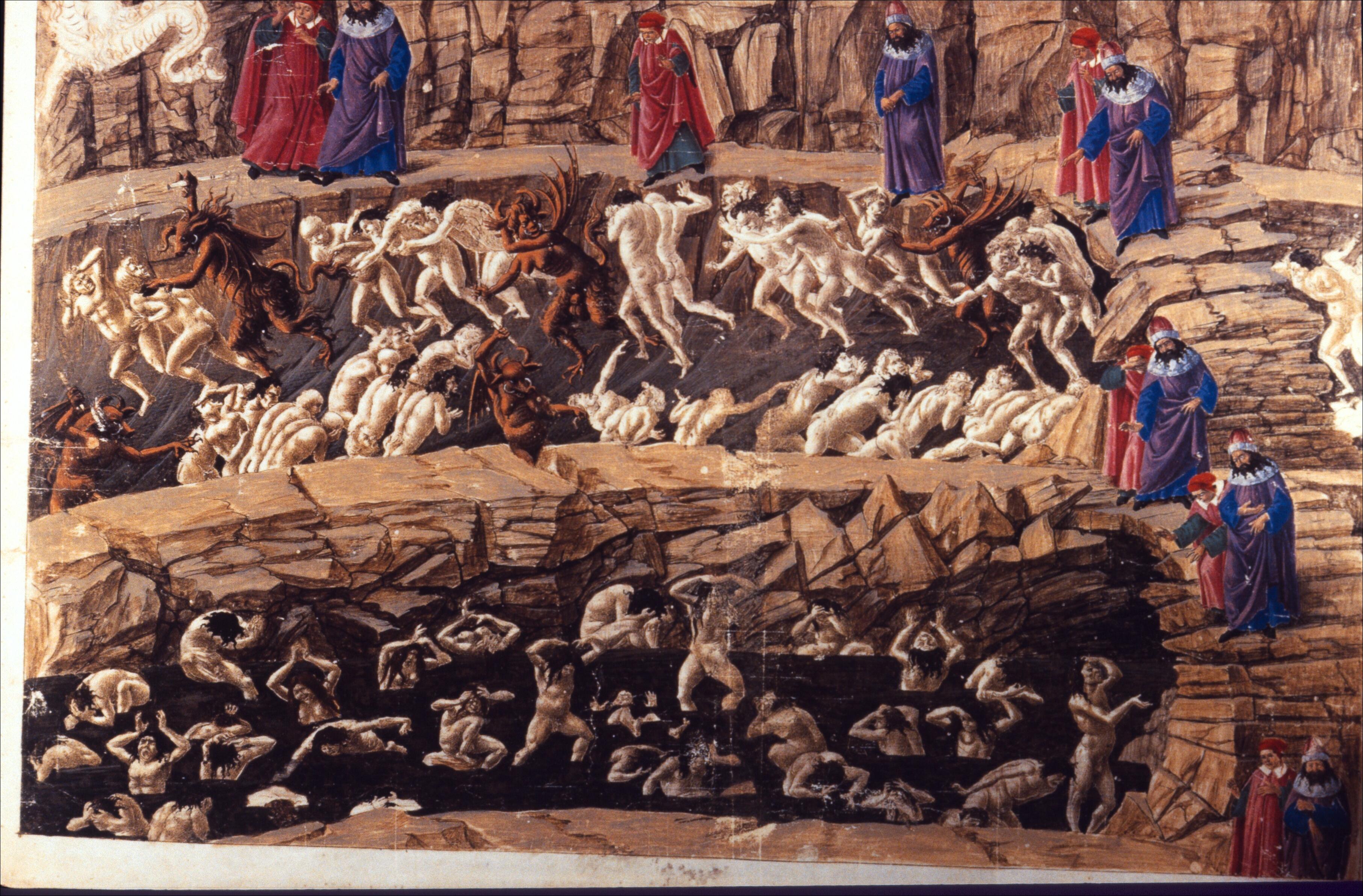

It is likely that they were never bound up into a volume; and it is certain that the artist only added colour to two of the 100 cantos. The rest are simply drawings with stylus, and pen and ink, as you can see below:

You have already seen and learned enough to prepare you for my claim that the relationship between ‘Poetry and Painting’ in the case of ‘Botticelli’s Drawings for Dante’s Comedy’ is very different from the relationships I have explored in the other two lectures on Purgatorio and Paradiso. In those, I looked at some of the links between Dante and the visual arts in his own time or earlier, and I was mostly concerned with the exploration of affinities and influences in independent works of art. In this case, however, the images we shall be looking at are specifically ‘illustrations’, subordinate to Dante’s text, produced by an artist who was nearly 200 years younger than Dante, who did not complete his commission, and whose small grey images were never intended to be displayed (as they were in London) stuck up side by side like oil paintings on the wall of an exhibition gallery.

We shall return several times to my reconstruction of Botticelli’s intentions and what it can tell us of the cultural context in which he worked; but before we leave the book for a time, I want call attention to an essential difference between the layout of the book that Catherine is reading, and that of a typical Book of Hours or illuminated manuscript of the Comedy; because it is from this single difference in layout that there follow most of the other features which make Botticelli’s drawings quite unique.

To underline this vital point, let us examine some whole pages from earlier manuscripts of the Comedy:

The first was produced as early as 1337, while the second dates from not long after 1400. As you can see, the traditional page used to be laid out in what we now call vertical or ‘portrait format’; the images are integrated with the text on the same page, and they are set either inside a decorated letter, or in rectangular boxes, in such a way that each picture is small in scale, and rigorously framed.

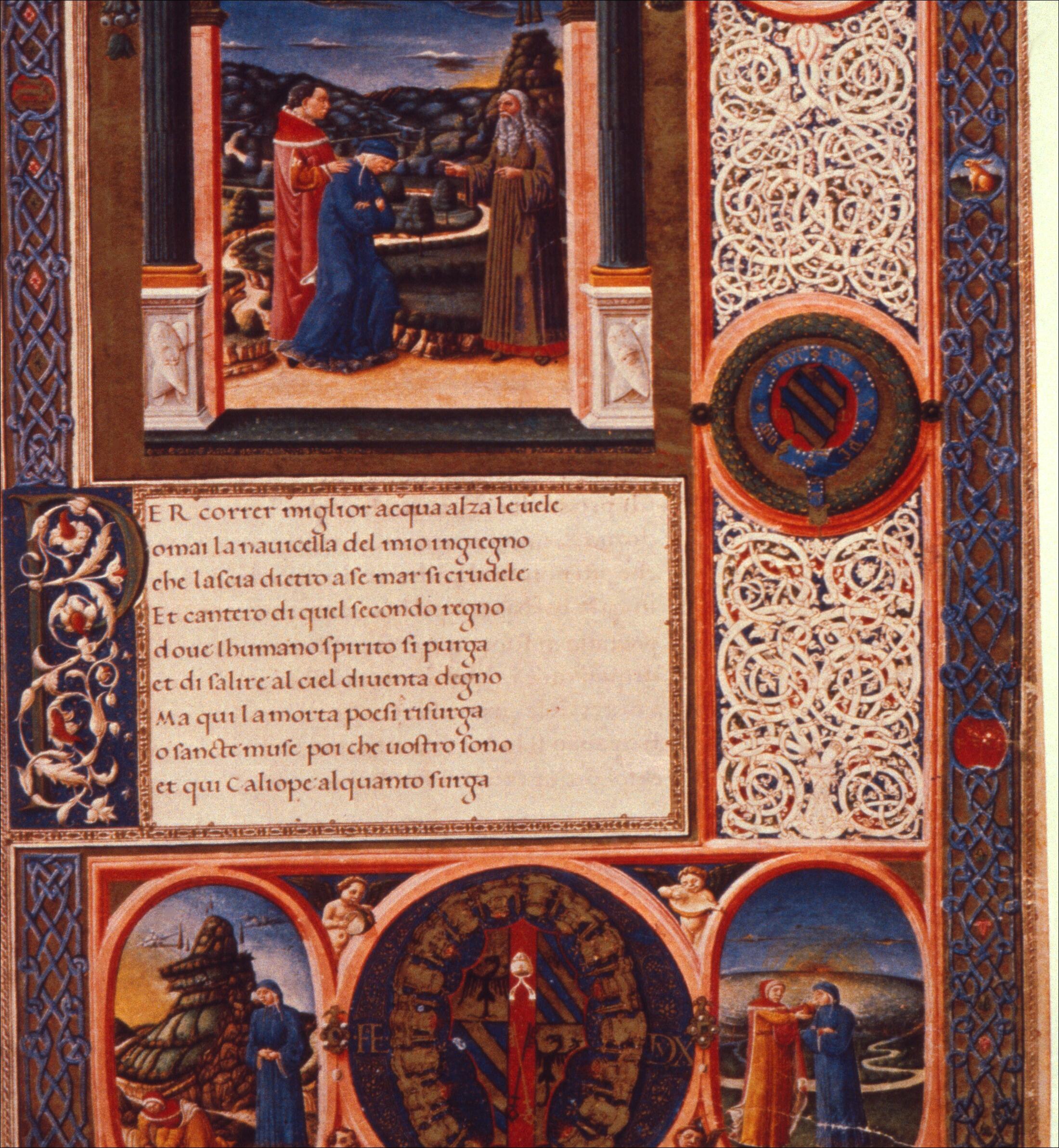

These conventions hold good even when you come to a manuscript from only a few years before Botticelli’s illustrations, such as this example from Ferrara in the 1470s:

In contrast, the book being ‘virtually’ read by our ‘virtual’ reader has to be viewed horizontally, ‘landscape format’, and the text and image are on separate pages. The text is set out in four columns, which makes it possible to get a whole canto of the Comedy on a single page; and this leaves a whole, large page—the back, the verso, of the previous canto—for Botticelli’s illustration.

Everything that matters about these illustrations—good and not so good—follows from that one innovation.

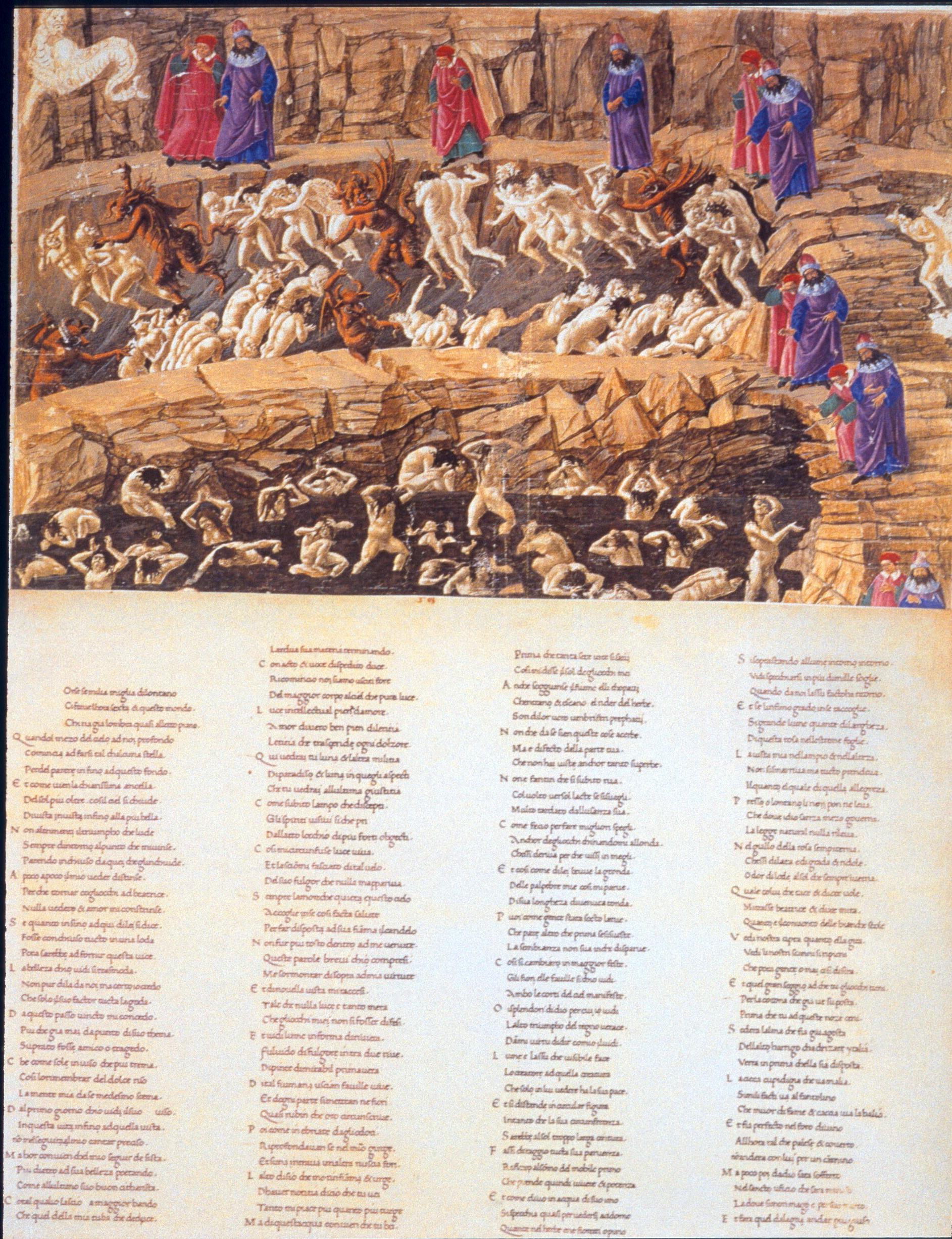

Let us begin with the good news. First, and most obviously, Botticelli has masses of room in which to show the setting, and to give a sense of the spaces, through which Dante moves on his journey through the afterworld. Second, the large size of the sheet enables him to represent all the successive events in the narrative of Dante’s journey (which is like a road movie, packed with motion, action and dramatic encounters). Third, the page is big enough for Botticelli to create a pleasing pattern, so that one looks at the composition with pleasure, even if one does not at first recognise that it represents more than one event.

I have called the layout an ‘innovation’—and so it is with regard to the tradition of illustrations to the Comedy—but from Botticelli’s point of view all he was doing was continuing his practice as a painter of narrative frescos, as we can see by taking a quick look at his work in this building:

fig. 8 shows the Sistine Chapel, as it would have looked in the first half of the 1480s, perhaps five to ten years before he did the drawings for the Comedy. We will examine just one of the narrative frescos that Botticelli painted, on the opposite wall to that above, illustrating how Moses was chosen and put to the test by the Lord.

It is a big painting, about 14 feet across, but the first point to notice is that the proportions are very close to those of the parchment sheets; Botticelli was thoroughly at home with this shape. Moses is dressed in yellow and green, and the colours enable you to see at once that he is represented no fewer than seven times within the same frame.

First, he is killing an Egyptian who had beaten up this Hebrew (we shall examine his face later), then fleeing the wrath of Pharoah, then driving away shepherds in Midia who were molesting his future wife, for whom he gallantly draws water, then taking off his shoes on Mount Sinai before approaching the burning bush, and finally leading his people out of bondage. (Notice, too, how confident Botticelli is in letting the story unfold from right to left, instead of the more usual left to right, which is something he often does in his drawings for the Comedy.)

Let us dwell a little on the landscape in this pictorial tradition. There is some typical late fifteenth-century realism—the buildings, the grove, the mountain pasture, and the flat ground stand respectively for Egypt, Midia, Sinai, and the wilderness—but essentially Botticelli is perfectly happy with the medieval conventions of the earlier International Gothic Style, in which the artist chooses to cover the whole of his surface with a rising, hilly background, seen from a high viewpoint, because this makes it easy to distribute the multiple episodes in the story in different zones, and to make them all clearly visible. (Botticelli remains entirely medieval in his selective disregard of the rules of perspective: at that distance, Moses should of course be far smaller than he is!)

Botticelli must have been delighted that in Purgatory and Hell Dante’s text actually demanded that he should imagine the rocky wall of mountain or the rocky wall of a pit. He uses almost the whole of this surface as the background for his narrative (he is not much interested in the sky).

You can also see that he is very concerned with the pattern made by his whole composition, tracing out a pyramid with his landscape to group the seven moments in the story into four plus three, while distributing all the episodes harmoniously around the delightful scene at the well.

Having taken in something of their antecedents, we may now return to the Dante illustrations. Even the most casual reader of the Comedy knows that the pilgrim’s passage through Hell was not simply on the flat. It is a journey downwards, taking him farther and farther away from God and the light.

In this illustration, the generous space available to the artist allows him to show you two of the infernal ‘ditches’ at once, the second (full of excrement), being not just closer to us, but lower than the dry bottom of the first. Dante and Virgil are clearly moving down towards the centre of the earth, deeper and deeper into the knowledge of evil, nearer and nearer to Satan. You simply could not achieve this effect on a smaller sheet.

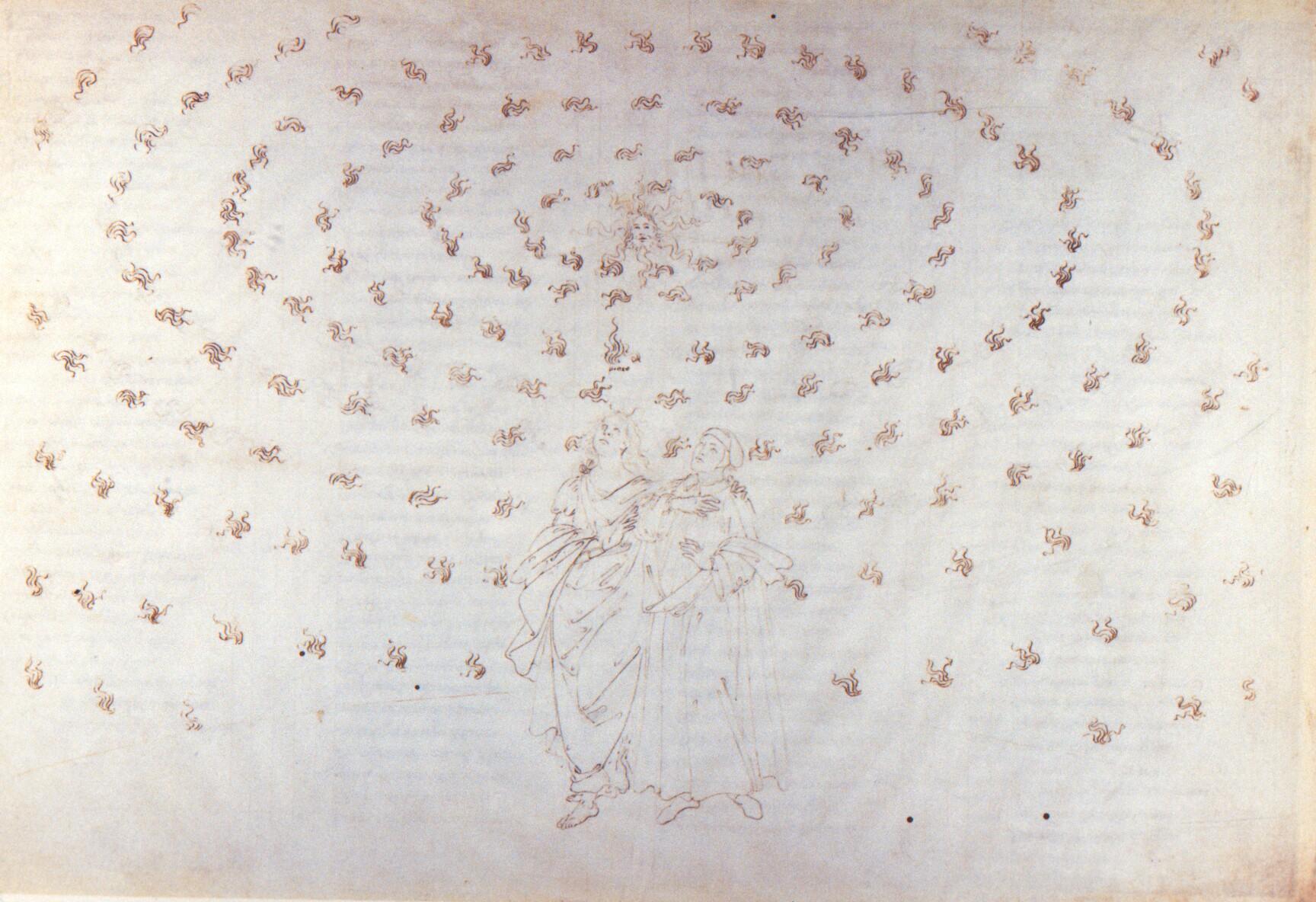

In the next two canticas of Dante’s poem the descent to evil is followed by ascent to union with the Good, the supreme Good, God; and for maximum contrast I now jump forward to Paradiso 30 (the last illustration that Botticelli completed) for this wonderful image (fig. 11) of Dante and Beatrice, borne upwards only by their “concreated thirst” for God, soaring towards the fountain-head of the river of light, of the river of grace.

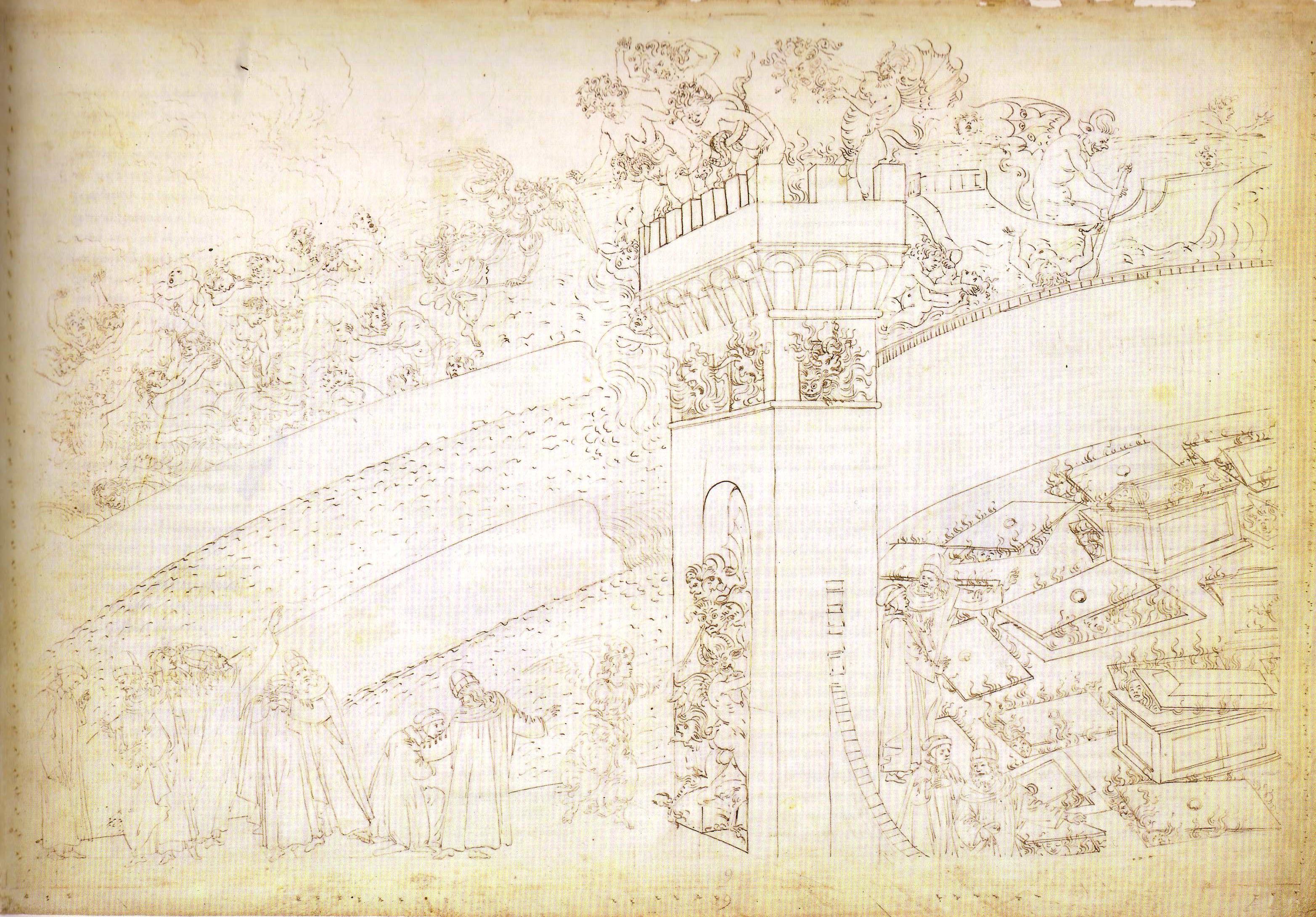

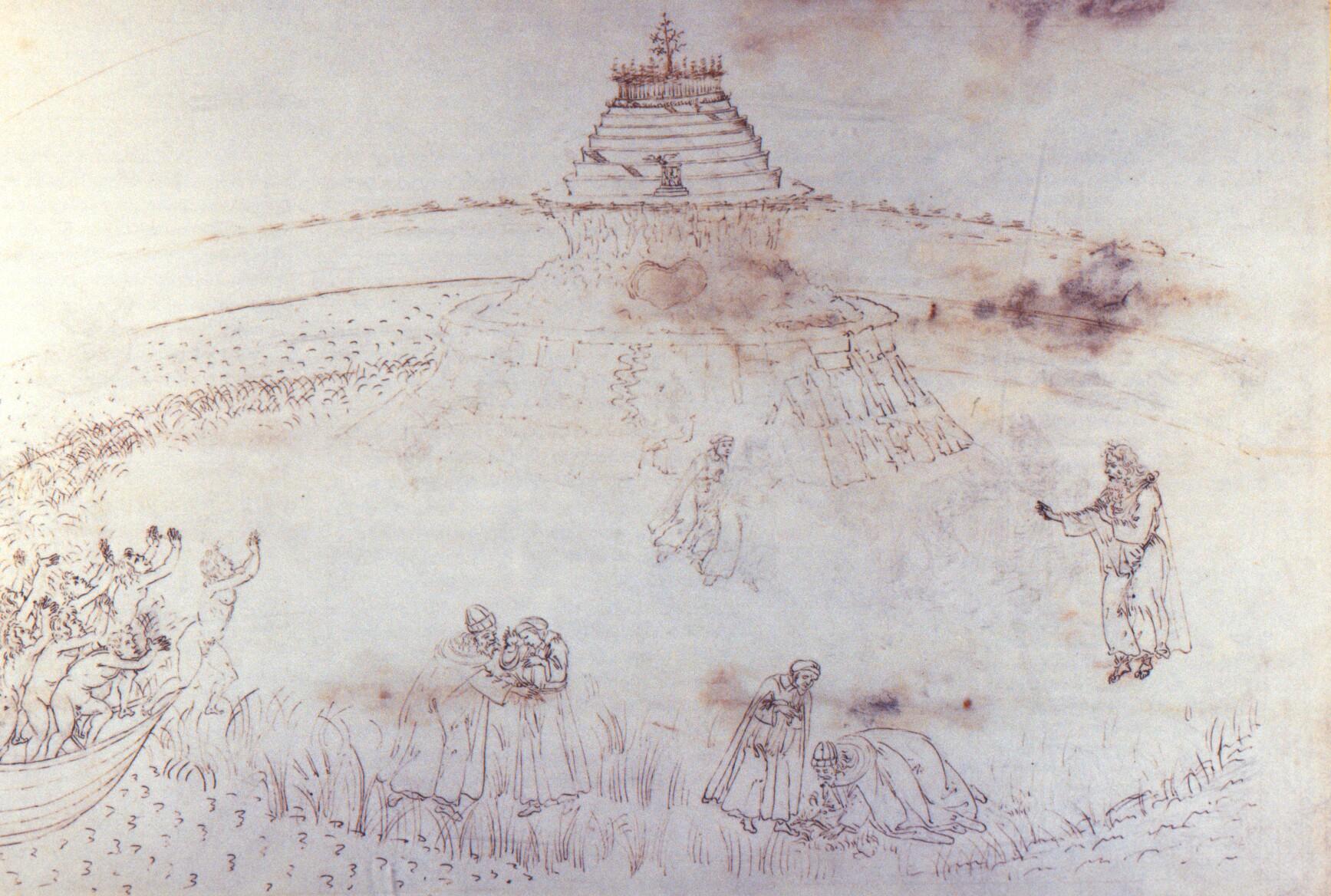

Of course the ascent had begun already in Purgatory, which demanded a hard climb up the ‘mountain of God’ to the Earthly Paradise situated at its summit. What follows (Figure. 13) is an example of Botticelli’s use of the height of his page to indicate the sweep of ascent; here you see the climb from the fourth of the seven ‘terraces’ of Purgatory to the fifth.

Dante the character slept on the fourth terrace for a whole night, and he is still almost ‘sleepwalking’ as he resumes his journey on the flat, before following Virgil, who has started to climb, past the angel who points upwards with an encouraging smile; then, together with Virgil, up the first flight of steps to the very top. But even now it is harder work for Dante, who is there in the body, than it is for Virgil, and you can see the effort needed for him to defy gravity and not fall behind.

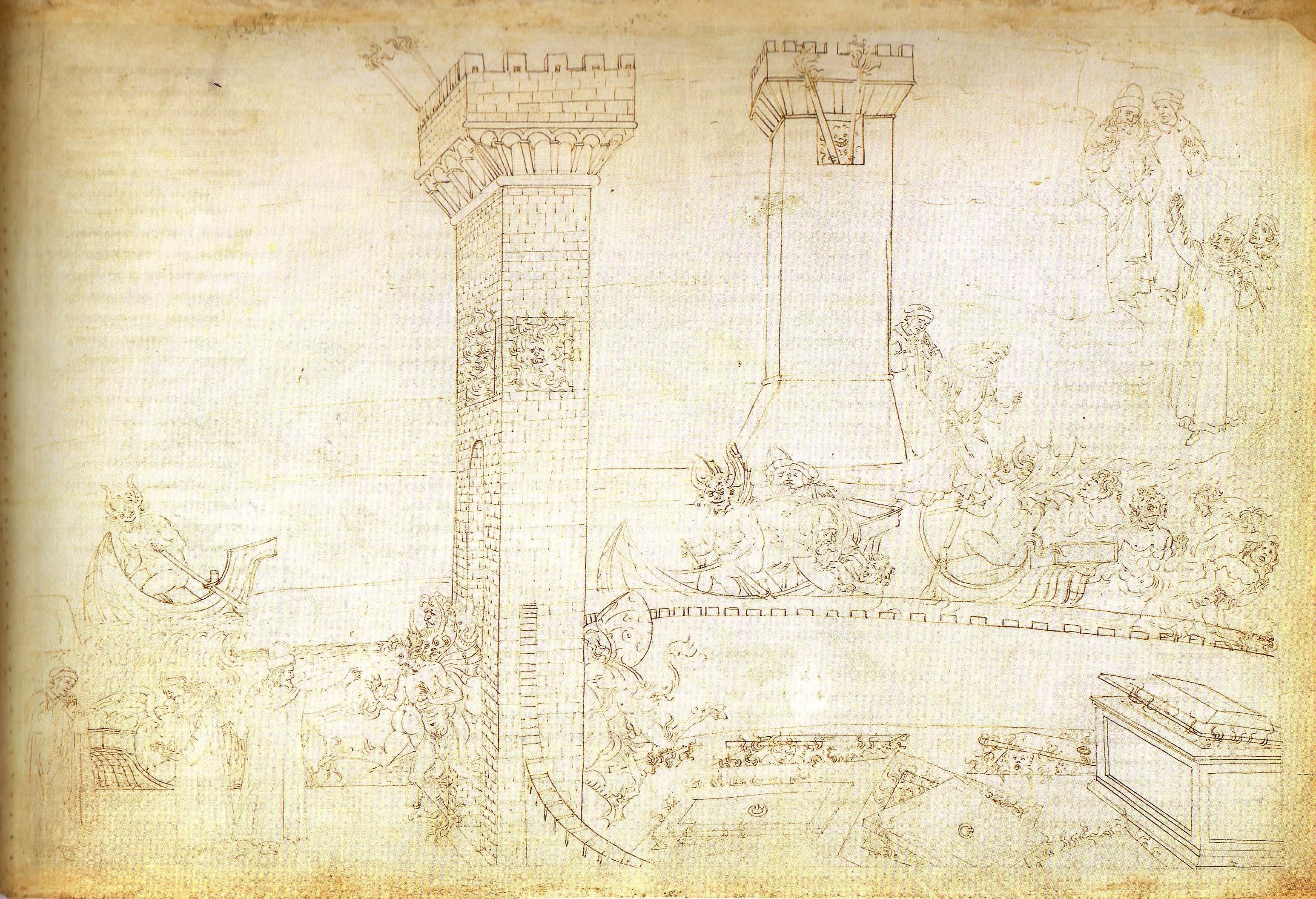

We may return now to my reconstruction of the intended format of these drawings, and to some of the negative aspects of the unique layout, which, you remember, has a whole page of text below a whole page of drawings. You will recall that it was not difficult to pick out the figure of Moses in the fresco, even though he appears seven times. But if you look now at the sheet illustrating canto 8, you will find it much harder to find the Dantes, even though he is only represented six times; and hard even to see where the river is (the Styx), separating the watch tower on the further side from the watch tower on the wall of the city of Lower Hell:

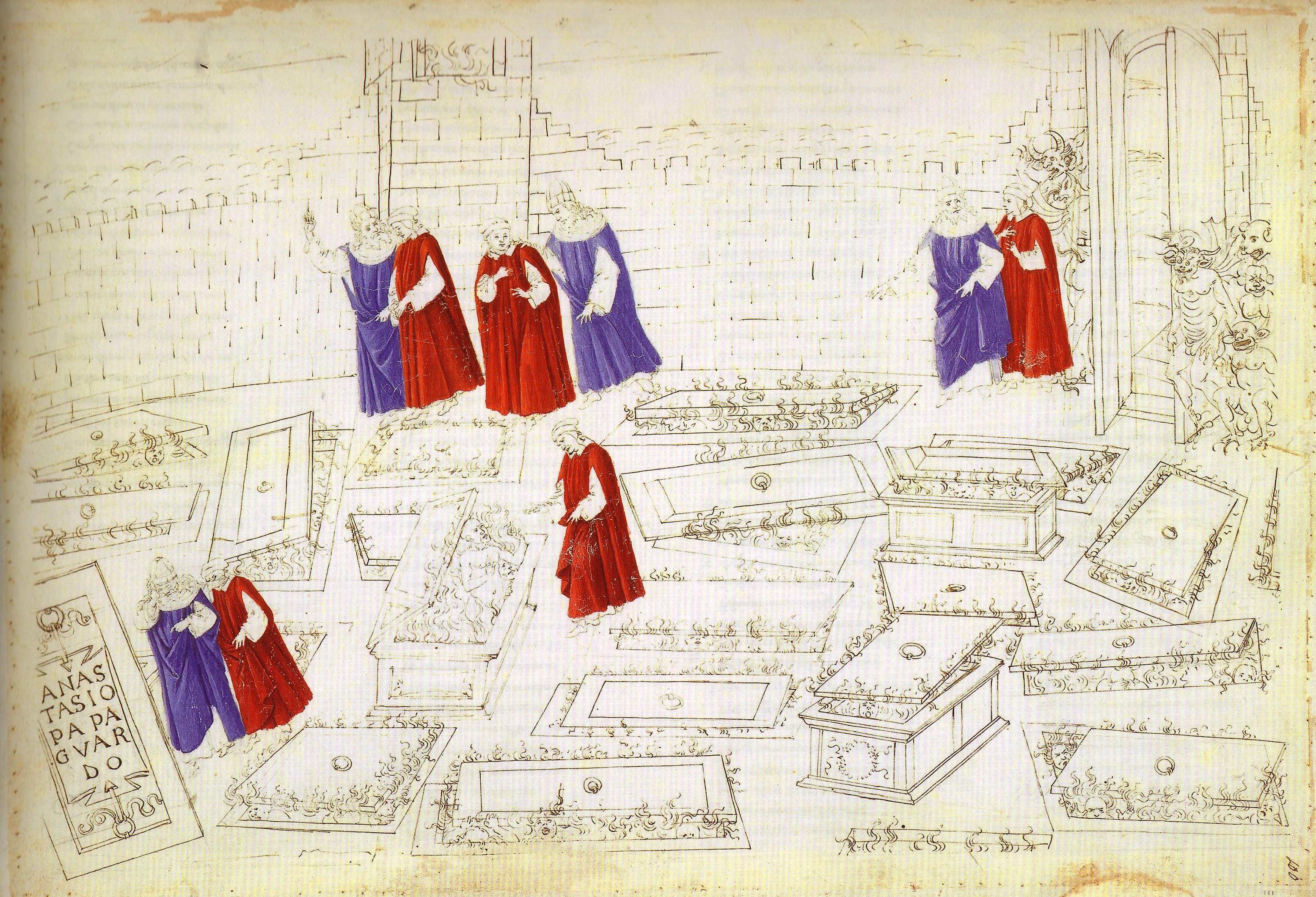

You will see that on this page, someone has used colour to pick out the figures of Dante and Virgil (it is the only illustration with this selective use of colour). There is no doubt in my mind that the use of colour makes it very much easier to pick out the successive positions of Dante and his guide (and to highlight the significant absence of Virgil in this tiny section, he having no part in the long encounter with Farinata).

So, what I am arguing is that Botticelli knew perfectly well that if you are going to put so many episodes on one page, you absolutely need colour to make the page intelligible. And unfortunately, as we have seen, he simply did not get round to getting an apprentice to colour in the great majority of the sheets.

Another example reinforces this point. In canto 10, you saw just five Dantes, but in the following illustration to Inferno 17, there are no fewer than seven:

We see him coming to the lower rim of the seventh circle, and talking with a group of usurers, and then we find him in need of transport; because, in order to descend the precipice separating the sins of violence in circle seven, from the sins of deception and fraud in circles eight and nine, he has to mount on the back of a monster, called Gerione, and be flown down, as if he were in a helicopter.

This page is relatively uncluttered, and the ink outlines are clear, but the dark grey lines on the light grey background still make it quite hard for the viewer to concentrate, even on a single part of the scene. It will therefore be useful, I think, to consider what it would have been like if Botticelli had finished the job and coloured at least the main figures in, as was done in Inferno 10.

Perhaps the best way to visualise what Botticelli originally intended would be to dig out your old box of watercolours, and to pick those figures out for yourself, like this:

See how Gerione comes to life as the ‘image of fraud’. Dante imagines him as a composite beast, with the face of a righteous man, the talons and wings of an eagle, and a scorpion’s venemous fork on his serpent’s tail. See how how much easier it is to follow every stage in this highly exciting moment in the story, which is very important for the development of trust between the terrified Dante and Virgil as his guide. Gerione has been summoned up from the pit below. Virgil is the first to mount, giving encouragement by example; he beckons to Dante, urging him to follow; then, as Geryon backs slowly out (like a boat from the quayside, says the narrator), Virgil senses Dante’s fear and unspoken desire and puts his arm round him, holding him closely for the rest of the flight. If there were time, further comparison with the original text of this passage would show us just how good Botticelli is at what we now call ‘close reading’.

But I would like to press on and repeat the same experiment of adding colour with another scene from much later in the poem. An important point of reference for this illustration is the following painting by Botticelli, which is from the 1490s, close in time to the Dante drawings:

It is usually called The Calumny of Apelles, and it is a re-creation of a lost classical painting by the artist Apelles illustrating the concept of calumny (that is, ‘bearing false witness’ in a court of law). We know about the painting only because it was lovingly described in words by a Greek rhetorician, in a very well-known example of the genre called ‘ecphrasis’.

Focus on the parchment-like colour of the architecture, the splashes of strong colour in the clothes, and the almost frenetic activity, as this is the best introduction to what Botticelli was required to do in his illustration to the tenth canto of Purgatorio, where, on the wall of the mountain, on the first circle, Dante and Virgil find three relief sculptures representing three scenes of humility, the virtue opposed to pride:

Here we are interested in the third of the scenes, the one at the top right, showing the Emperor Trajan, who, as he marches out to war, is checked by a widow, demanding justice for the murder of her son. Dante’s description of the sculptured reliefs is a marvellous example of poetic ‘ecphrasis’:

Quivi era storiata l’alta gloria

del roman principato, il cui valore

mosse Gregorio a la sua gran vittoria:

io dico di Traiano imperatore;

e una vedovella li era al freno

di lacrime atteggiata e di dolore.

Intorno a lui parea calcato e pieno

di cavalieri, e l’aquile ne l’oro

sovr’essi in vista al vento si movieno.

La miserella intra tutti costoro

parea dir: «Signor, fammi vendetta

del mio figliol che è morto, ond’io m’acoro».

(Purgatorio 10, 73–84, text from Sanguineti edition)

The confusion of the scene is vital to the story: the widow could not have chosen a worse moment to plead her case. And Botticelli’s illustration is one of his most amazing responses to the four columns of text which would be displayed below:

You can now pick out the Emperor in a flash, and recognise immediately the figure of the kneeling widow. For myself, I find the colours help me to pick up the rhythms—of the horses galloping across the page, or rearing up when they are checked and swung round, contrasting with the kneeling soldier and with the by-standers who gesture towards the widow; and in this version, I can really see the wind-swept pennons.

This is perhaps the moment to say that the colours in these images—just water colour applied to a Xerox—are the work of a friend and long-time companion of my mother, Eileen Burke, an amateur artist who was then in her late 80s. She did the work at my request in just a couple of days, setting out with almost no knowledge of Botticelli, and armed with no more than the catalogue of the exhibition and a book of reproductions of his paintings. She did it as a labour of love, and it taught her more about Botticelli and Dante than a hundred lectures could do. I value her contribution to this lecture much more than the input from any other source. It is dedicated to her memory.

I have implied that the absence of colour on these large, crowded sheets

was part of the ‘bad news’. Another piece of bad news is that the depiction of so many successive events on a single page, using a common scale for all the actors, makes it impossible to do justice to the personalities of all those characters in the poem who appear only once.

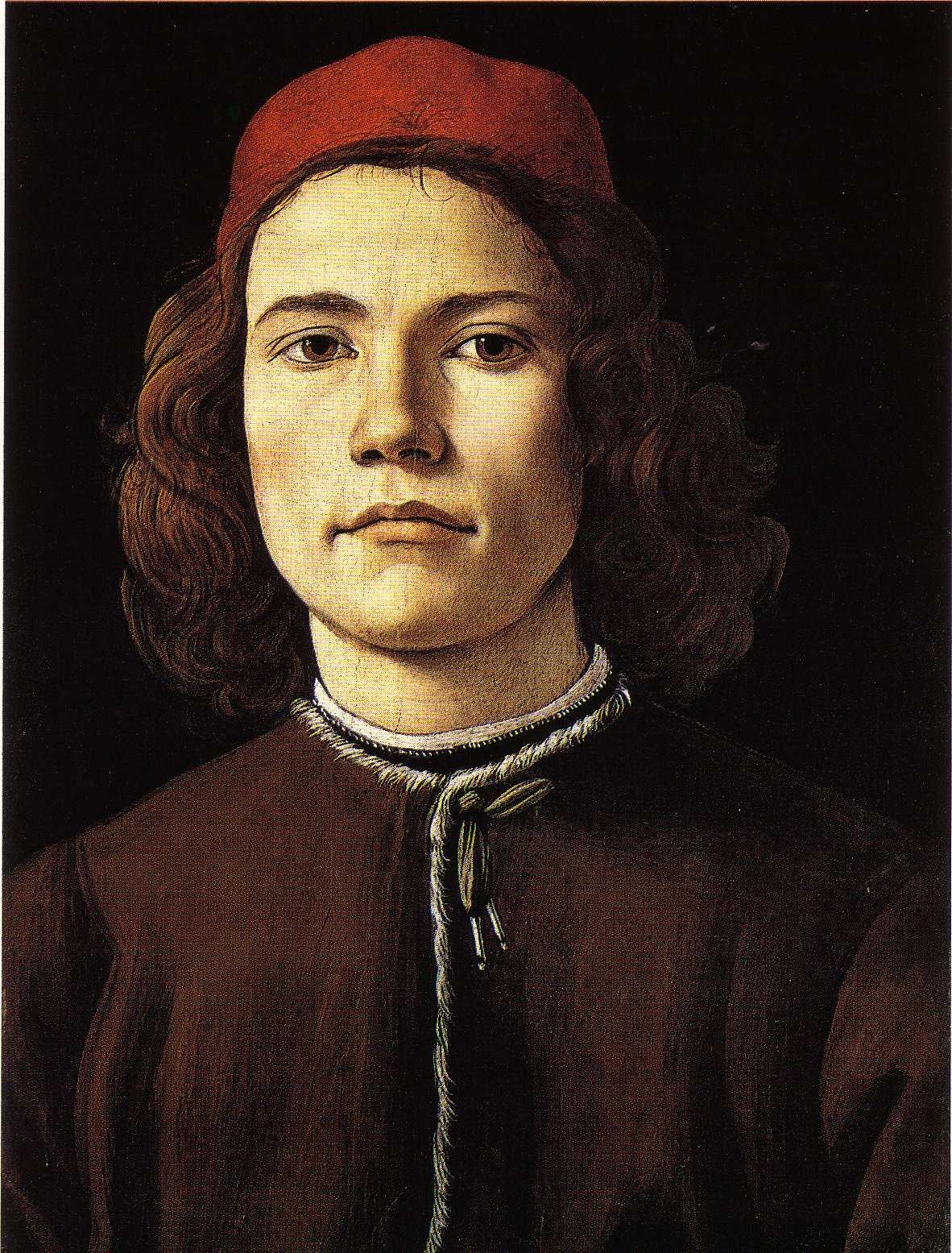

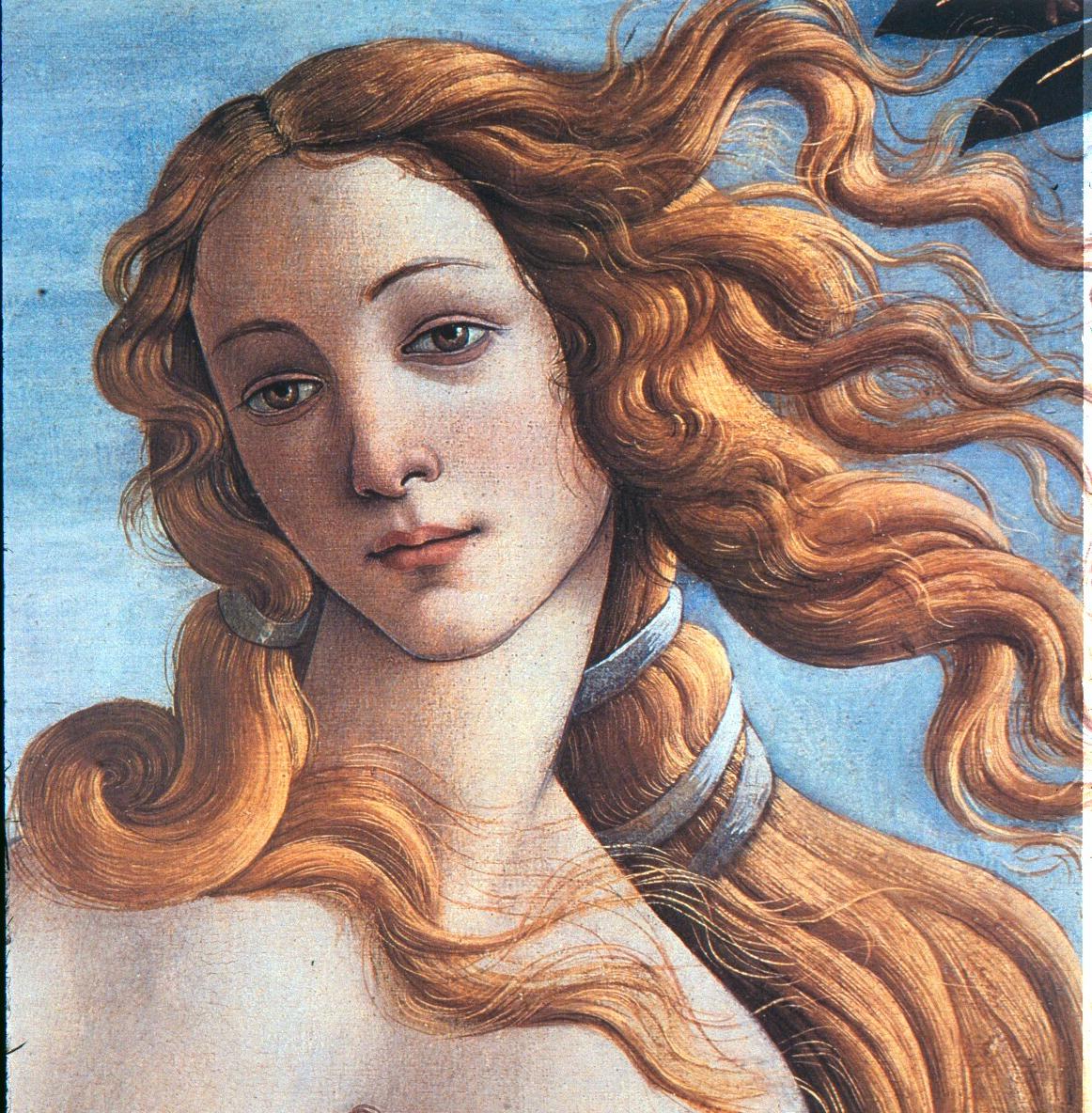

There are no “close-ups” or “insets” on a different, bigger scale. The figures are all so tiny that the individuality of a face and its fleeting expressions have to be suggested in no more than three or four lines with the stylus or pen. Botticelli certainly could capture the individuality of a face, in a way that no artist of Dante’s own time could have done (see fig. 22a); and I suppose he might well have done justice to some of the great sinners or penitents in the Comedy, if this had been part of his brief. Yet I am by no means entirely convinced of this, because it must be said that Botticelli’s idealised heads are often rather conventional, even vapid, especially the women. Some examples of this are shown below (in fig. 22b & c), where you can see a woman from one of his frescos in the Sistine Chapel, alongside a head of Beatrice taken from our manuscript. I find these striking for their capture of movement but not of individuality or character.

And while we are on the subject of limitations, perhaps we can pause to qualify some of the ‘hype’ that found its way into print almost everywhere at the time of the exhibition in 2001. The exhibition proved to be a great success with the public, and rarely have I seen such enthusiastic coverage in the media and such consensus among the critics. Everyone agreed that this was a ‘marriage of true minds’ between a great poet and a great artist, and everyone seized on a splendid opportunity for what I. A. Richards memorably called ‘the luxury of safe praise’. I do not dissent from this general judgement; but no marriage is perfect. A picture can ‘be like a poem’ (as Horace memorably remarked), but only up to a point. To give an obvious example, it cannot represent complex dialogue. If you turn back to the illustration reproduced as fig. 15, you would never guess that it corresponds to one of the most famous dramatic scenes in the whole of world literature, the clash between Dante and Farinata degli Uberti in Inferno 10.

Similarly, although Dante is undoubtedly a great storyteller, concentrating on action and focussing on detail, he does not always give his illustrators the kind of opportunities you have seen so far. For most of the second cantica (Purgatorio), the setting is no more than a narrow stone ledge, and a stone wall behind:

Like virtually all of Dante’s earlier illustrators, Botticelli denies himself the opportunities that Gustave Doré would seize on in the nineteenth century, meaning that he does not attempt to illustrate the narratives (such as that of Buonconte in Purgatorio 5) in which the souls of the dead tell how they came to die and what happened to their body at death, or when they relate their experiences and adventures in life. Again, no painter chose to represent the hundreds of similes in the poem, while the ever increasing flood of metaphors are not reducible to images. Nor represented, either, are the wonderful philosophical ‘hymns’ of Paradiso. Taking all these absences into consideration, I would say that Botticelli is forced to leave out at least 80% of what Dante’s readers read him for.

So what does that leave? What is there in the remaining 20% of The Divine Comedy that does lend itself to illustration? Answer: ‘Quite a bit’! There remain the soul-bodies of the damned in Hell and the penitent in Purgatory. There remains, as we have seen, the story of the journey, the constant movement from place to place. And there remain the crucial links between the traveller and the things he sees—by which I mean all the emotions that surge through Dante the pilgrim as he sees the damned and the penitent; the emotions which used to be called the ‘passions of the soul’.

In medieval and Renaissance psychology the passions of the soul constitute the ‘motive force’, the vis motiva, of all our instinctive ‘movements’, big and small. The passions were thought to have their seat in the heart, and from there they operate on all parts of the body by means of the so-called ‘animal and vital spirits’, which were thought to flow up and down the nerves and the arteries. It is the passions that directly affect our heart-beat, our rate of breathing, all our muscular flexions, extensions and rotations, and all our reflex responses to sudden stimuli. It is the passions, such as fear, anger and desire, that initiate and control all our big movements, such as running away or fainting; and it is the passions that cause all the lesser effects, like blushing, growing pale, trembling, sighing, smiling, or frowning. It is by their means that our outside reveals our inside, that our ‘affection is seen in the face’:

“Come si vede qui alcuna volta,

l’affetto ne la vista, s’elli è tanto,

che da lui sia tutta l’anima tolta…”

(Paradiso 18, 22–4)

that the ‘features bear witness to our heart’:

“Deh, bella donna, che a’ raggi d’amore

ti scaldi, s’i vo’ credere a sembianti

che soglion esser testimon del core…”

(Purgatorio 28, 42–5)

or that ‘the face shows the ‘colour of the heart’:

“Lo viso mostra lo color de core

che, tramortendo, ovunque pò s’appoia…”

(Rime, XII, 5–6)

You may be mildly surprised to hear me talk of ‘medieval psychology’, and surprised at my very specific description of the way our feelings were thought to work on the organs of the body. But I can assure you that ‘psychology’ was not invented by Sigmund Freud, and that the work of Aristotle which gave its name to ‘psychology’—‘Concerning the Soul’, Peri Psychês—was one of the most-studied of all works in the Middle Ages and Renaissance. From his early poetry right up to the final cantos of the Comedy, Dante was fascinated by what he knew about the interactions of body and soul; and I have dedicated a whole book, (Perception and Passion in Dante’s Comedy) to explain the interactions of his thought and poetry in this area.

The single most important fact that I want to put across about Dante’s technique as the teller of a gripping story is that he concentrates intensely not so much on the things and beings he allegedly saw and heard, but on the way that he as protagonist perceived them, how these perceptions affected him emotionally, and how these emotions made themselves visible. And what I want to argue now is that Botticelli had an equally acute interest in the way our feelings cause physical changes in the body. For him, too, it was almost as if the ‘passions of the soul’ were writing messages on the pages of the body—which is, of course, how we are able to communicate our feelings without speech, and to interpret the feelings of other people, without speech, through what we would now call ‘body-language’. Botticelli could draw the human body, naked, without a model, from any angle and in any position, and he had long been capable of capturing any movement while it was happening.

Below is a detail of a girl among the onlookers in another fresco in the Sistine Chapel. She is bringing ‘clean living’ birds to a sacrifice in the Temple of Jerusalem, and one instinctively knows exactly where she was a split-second before, and where she will be a split-second later. Botticelli can use this kind of ‘movement made visible’ to tell you what kind of emotion, what kind of passion, is providing the inner energy, the ‘motive force’.

Brilliant as he undoubtedly was in rendering the nude body, Botticelli is actually at his best when his figures are clothed in flowing dresses, or in long, loose-fitting garments such as those worn by Virgil or by Dante the pilgrim, because the natural fall of the cloth from a raised arm, or the swish of a cloak from a previous gesture, both enhance the sense of physical movement, which is precisely what reveals the so-called ‘movements of the soul’. Remember, too, that there is one part of the body which is like a cloak anyway—the hair, which Botticelli treats like flowing waves or coiling spirals, deliberately combining two or more of the seven kinds of simple movement possible in nature (see fig. 27a; I am referring here to Leo Battista Alberti, who thought that an artist ought be able to suggest all seven movements on the unmoving surface of his picture). He is equally adept at doing this with a woman’s long hair, or, more importantly for our purposes, with a man’s forelock or an eyebrow, making a face intensively expressive, as is evident in the black and white detail from the Sistine Chapel fresco showing the Trials of Moses (fig. 27b), which we examined earlier:

Botticelli’s desire to communicate movement is so strong that he will sometimes show the head in two different positions on the same body, as he does (see fig. 28) when Virgil pivots to take another direction, just as the text specifies (Botticelli, as we have seen, is an almost incredibly attentive reader).

Usually, Botticelli will tend to concentrate on movements caused by the act of seeing and the things perceived by the eye—but not always, as we find if we look at the events on the terrace in Purgatory which is reserved for the souls of the envious:

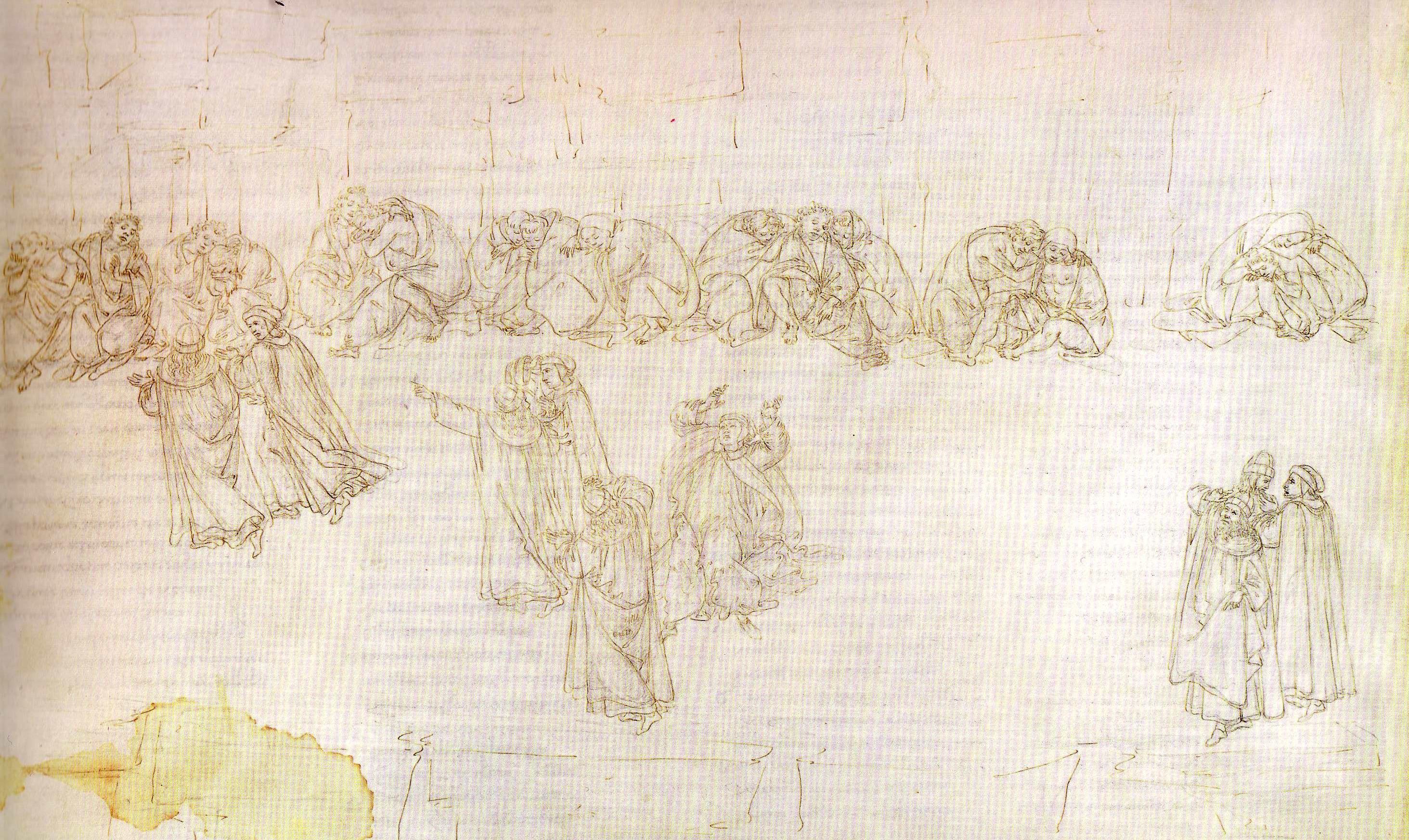

Like all the souls in Purgatory, the envious are provided with negative and positive examples on which they meditate as part of their purification; but unlike other souls they can neither see nor move, because their eyelids are stitched together, and they sit huddled against the wall. So it is arranged for unseen voices to pass calling out the names of those whose examples are to avoided or followed. To the pilgrim, these sudden, inexplicable voices are highly alarming; and you see him rocking slightly backwards, throwing both arms high in the air, while his knees seem to knock together; and even Virgil drops his right shoulder and lifts his right arm as if to ward off an attack.

When the voices return in the next canto, it will be Virgil’s turn to throw up both arms, while Dante is seen swinging round, as we can deduce from his coat-tails, rocking to one side, looking up in alarm, and trying to protect himself.

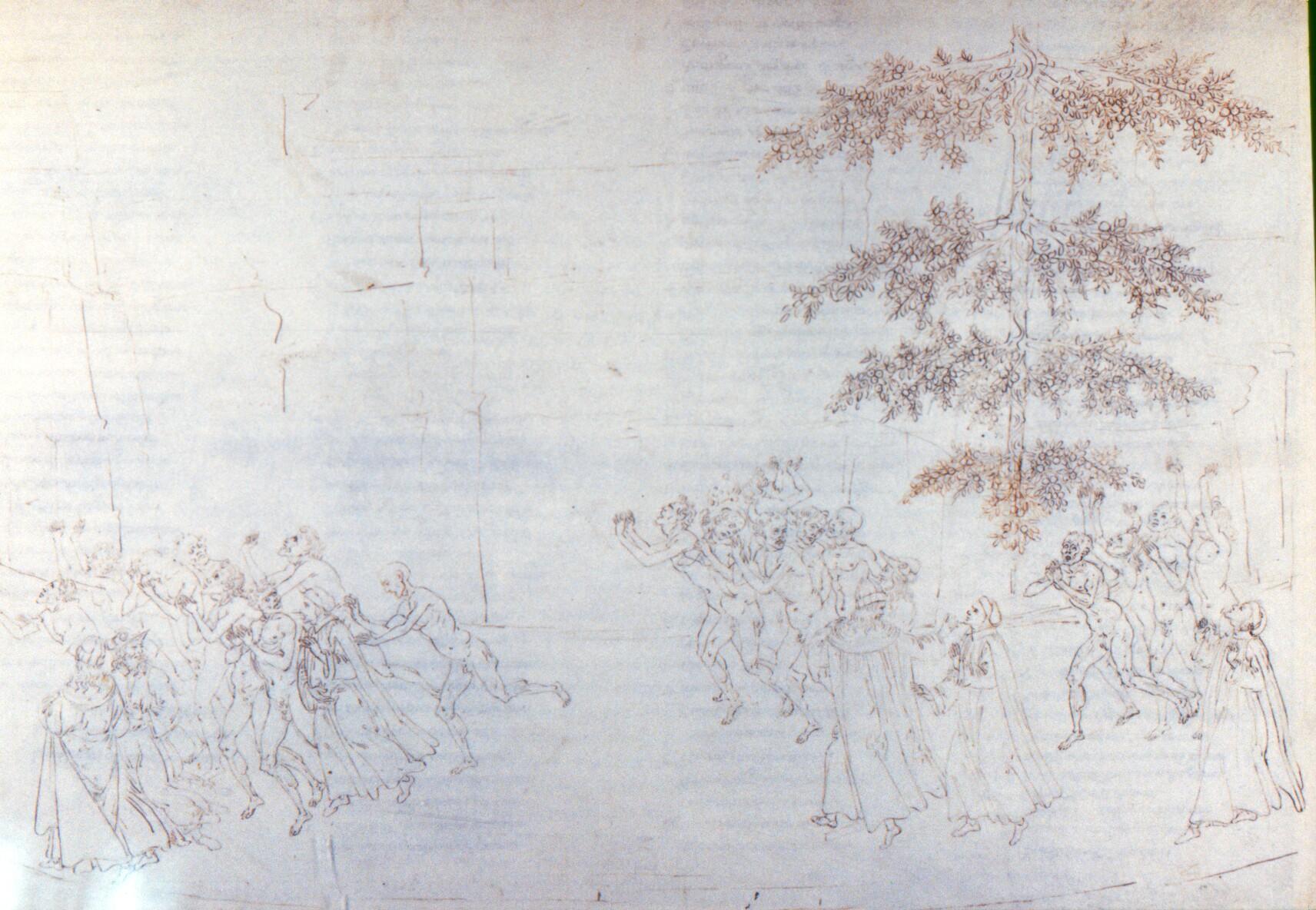

This is the sixth cornice, where Dante is shown gazing up in wonder (not alarm) at a miraculous fruit tree, growing from the top downwards. The tree is covered in succulent fruit, the sight of which simultaneously torments and purifies the souls of the greedy, the ‘gluttonous’, ‘gulosi’, who gesture up to it from below, and who are shown as being emaciated by their desire for this unatttainable fruit. So emaciated are they that Dante is almost unable to recognise his old friend Forese Donati as Forese swings round to look at him.

What Botticelli represents here is the intense concentration of Dante’s querying gaze, his head being drawn back, and his eye shown darker, while his right arm is raised as if he were pushing away, and the right hand is raised to show a new kind of wonder on meeting his friend.

I now want to turn my attention to the relationship between Dante and Virgil, more or less confining myself to close-ups, as if I were using Pope Leo’s magnifying glass. I do this because it is in these details of the two poets that Botticelli, closely following his text, uses his command of line to give expression to some of the more subtle ‘colours of the heart’, as they are revealed in some of the most profound and subtle episodes in the whole Comedy.

In the first scene, from Inferno 20, Dante is recoiling aghast, drawing his head into his shoulders, ducking, inclining his head in grief and raising both hands in protest, as he weeps at the spectacle of the soothsayers, whose punishment consists in having their heads twisted round through 180 degrees so that they look backwards as they walk. Virgil is steadying him but he is also reproving him for showing compassion of any kind at the results of God’s just ‘vengeance’ on sin.

Nine cantos later—once again the two poets are crossing a bridge over the concentric ditches where the fraudulent are punished—Virgil is still very much the confident leader, holding up his coat in front of him with his right hand, as he often does, in order not to trip, while he talks over his shoulder to Dante, who is covering his ears to shut out the laments of the forgers and falsifiers.

The relationship between master and guide becomes much more complex, however, in the purely Christian realm of Purgatory, where Virgil has never been before, and where he will never come as a penitent soul—as Dante hopes to do after death, on his way to Heaven and the vision of God. On the shores of the mountain island in the southern hemisphere, Virgil badly misjudges his approach to the guardian of the shore, Cato of Utica, and is answered brusquely for his pains:

He is carrying out Cato’s orders, not showing his own competence as guide, when (in fig. 33) he leads Dante to the shore, and kneels to pluck a rush, which he binds with utmost tenderness and care round Dante’s waist, as a symbol of humility. In the next canto Virgil will be actually admonished by Cato for allowing his charge to hang about wasting time; and he is still upset by this reproof at the beginning of Canto 5:

In the detail (fig. 34), you see Virgil from the rear, his head slightly inclined, his right hand raised as he scolds Dante for paying any attention to the whispered comments of the souls sitting on the ground. The situation is immediately intelligible to all those of my age who were ever given an undeserved rollicking by a corporal who had just been bawled out by the RSM! Further to the right, Virgil is again seen acting as the leader, apparently restraining the impetuous advance of two messengers who had come running up to the pair; but he will never be as confident again.

We jump a long way forward now to the fifth terrace of Purgatory, where we find Virgil and Dante have been walking along, looking down on the prostrate soul-bodies of the avaricious and prodigals (see fig. 35, on the extreme left). They have just heard the mountain of God ‘skip’, and a choral Gloria sung by all the souls in Purgatory; and here they are caught up with the very soul whose release from purgation was announced by the earthquake and the song:

He is Statius, the first-century AD Roman poet. Like Dante and Virgil, Botticelli draws him with his clothes on, but he is distinguished from them by his curly-brimmed hat. Notice again how, even here, Botticelli is showing different movements of the soul in the different movements of the three bodies. Statius is walking very briskly (he has just been allowed to stand up and move after 1000 years face down on his belly). Dante is clasping both hands in alarm at the sudden appearance; Virgil calmly halts and turns back.

In the centre group, Statius goes on to explain who he is, and how much he owed to Virgil, both as poet and moralist, and even for helping to convert him to Christianity. He still does not realise he is in Virgil’s presence, and when Dante involuntarily ‘betrays’ his master with a smile, Statius kneels in an attempt to embrace his master’s feet. It is one of the most haunting moments in the whole poem, and although Botticelli does his best, this is one of the scenes where the gap between the words and the image is inevitably wide.

They move off as a threesome (fig. 36), and here I would like you to notice how much information Botticelli can convey even from a rear or side view of the body. Statius and Virgil are deep in conversation with another, talking shop. Virgil is listening intently; and it is Statius now who makes the gesture of a leader, while Dante is straining to catch every word behind.

There are many more variations on the grouping of this ‘threesome’ in the following cantos, but we must jump forward again to the last scenes involving Virgil, before his abrupt and silent disappearance. The next detail (fig. 37) illustrates a slow, sad speech (made shortly after a major failure of trust on Dante’s part), in which Virgil is taking leave of his pupil (although Dante does not realise this):

He tells Dante that he has shown him everything that human reason can see; now faith and love must take over in the person of Beatrice. But he is also assuring Dante that his will has been set free from bondage to sin with the words ‘I crown you, and I “mitre” you over yourself’.

In the poem Virgil never utters another word, although we are reminded of his presence as Dante comes with Statius into the beautiful wood in the Garden of Eden, on the summit of the mountain. Virgil is now seen (fig. 38a) as a pensive, sad figure, thinking of his return to eternal exile in Limbo, keeping behind the two Christians with his head held low. And as the three walk further along on the near side of a stream separating them from Matelda (fig. 38b), his head hangs lower still, despite Statius’s gesture of concern:

Perhaps this is because Dante, his ward, who has become like his son, seems to be wholly taken up with the beautiful Matelda. Botticelli will show Virgil once more in the same kind of attitude, still remaining behind, still on this side of the stream: and then we see him no more.

I would like to round off my lecture by picking out some scenes from an earlier canto, that seem to me to encapsulate all the main points I have been making about Botticelli’s response to The Comedy, and about the way in which the artist intended us to use his ‘smiling pages’—glancing up from Dante’s words in front of us to his images above, as in the reconstruction shown in fig. 4. It seems only fair to give the poet himself the last word.

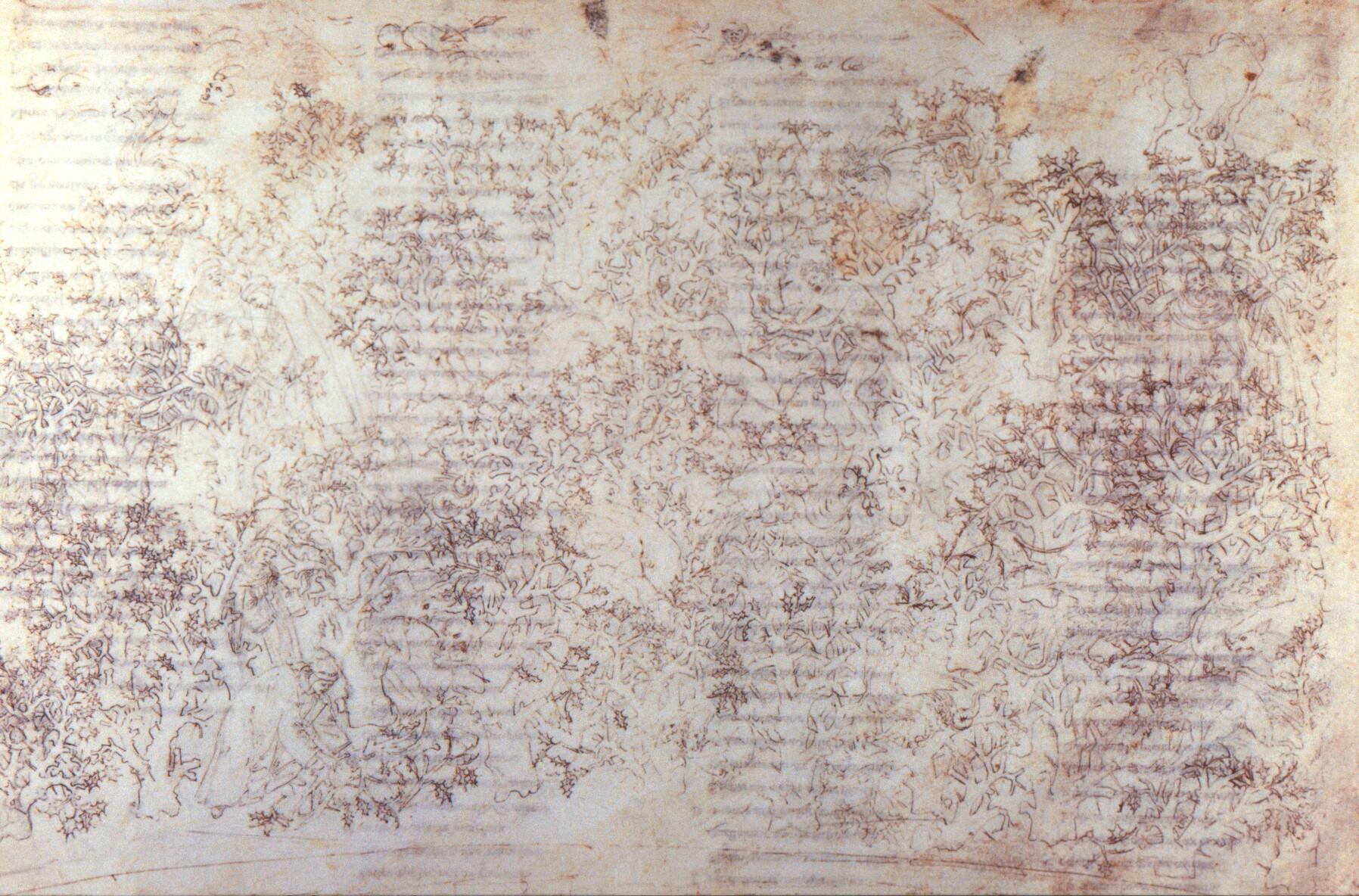

The canto I have chosen contains one of the greatest dramatic scenes that Dante ever wrote, and one for which Botticelli would have produced one of his finest illustrations. The scene is set in a pathless, almost impenetrable wood; and the state of Botticelli’s drawing is enough to make you tear your hair out:

Dante and Virgil enter the wood top right (fig. 41a), and the main event in this canto is illustrated top left (fig. 41b). It is Dante’s meeting with the soul of Pier della Vigna, the imperial Chancellor back in the 1240s, who committed suicide when he was accused of breaking faith with Emperor Frederick the Second. This encounter, I have to say, belongs to the 80% of Dante’s poem which I do not think any painter can match, but for our purposes it is enough to know that every tree in this wood is the ‘body’ of a suicide; and that Dante is pictured breaking off a twig from one of the trees, only to see it ooze blood and to hear the hissing reproaches of Piero, to whom he has unwittingly given a mouth.

However, Botticelli can and does illuminate the whole of the canto by helping you to keep in mind the impenetrability of this dark and pathless wood which is at the heart of the episode, and this is the visual equivalent of the negativity which Dante drives home in the opening lines of the canto, where five of the first seven lines begin with the word ‘Non’.

Non era ancor di là Nesso arrivato,

quando noi ci mettemmo per un bosco

che da neun sentiero era segnato.

Non fronda verde, ma di color fosco;

non rami schietti, ma nodosi e ’nvolti;

non pomi v’eran, ma stecchi con tosco.

Non han sì aspri sterpi né sì folti…

(Inferno 13, 1–7)

A few lines later, we read about the foul monsters, the Harpies, who ‘make their nests’ in the ‘strange trees’, where they ‘make lamentations’:

“Quivi le brutte Arpie lor nidi fanno,…

Ali hanno late, e colli e visi umani,

piè con artigli, e pennuto ’l gran ventre;

fanno lamenti in su li alberi strani.”

(Inferno 13, 10–15)

The Harpies appear in the bottom-right of Botticelli’s illustration, which captures not only their monstrosity but also the ‘strangeness’ of the trees:

This description is followed by the breaking of the branch (already discussed), and the long, eery conversation with Piero, with whose haunting words Botticelli can of course do absolutely nothing, and which he makes no attempt to represent.

We shall therefore move on to the final episode in the canto where we witness, still in the same dark wood, the punishment of the prodigals—the ‘squanderers’ who destroyed their possessions with the same recklessness as the suicides destroyed their bodies, and who are pursued through the wood by hellish hounds, and torn to pieces in the same way that the Harpies tear the branches off the trees:

Here are Dante’s words at the point where the text becomes ’illustrable’ again, where the souls of two of the damned prodigals plunge through the wood, as depicted by Botticelli in the centre of his page:

Ed ecco due da la sinistra costa,

nudi e graffiati, fuggendo sì forte,

che de la selva rompieno ogne rosta.

…

Di rietro a loro era la selva piena

di nere cagne, bramose e correnti

come veltri ch’uscisser di catena.

(Inferno 13, 115–117 & 124–126)

We can see one of the hunted souls ‘squatting down’ by a bush, trying to hide—in vain, because the dogs ‘put their teeth’ into him, ‘tore him to pieces chunk by chunk, then carried off those tortured limbs’:

Close examination reveals how Botticelli visualised the ‘dismemberment’. As the hounds tear the soul to the pieces, they also tear the branches from the stem of the sheltering bush, which is the body of another, less illustrious suicide; and—as with Piero—the bleeding wound becomes a ‘mouth’ through which the soul can call out to the two poets. Virgil takes Dante’s hand, leading him closer, and the suicide reveals that he is a fellow Florentine. His words move Dante the pilgrim to compassion, so that he gathers up the torn and scattered branches at the foot of the tree, as pictured further to the bottom left of Botticelli’s page.

The lines that Botticelli could illustrate show Dante at the very top of his form, and I would like to read them aloud for you now while you look at details from the page.

With the words ringing in your ears, and the images before your eyes, I hope you will agree with Dante’s own explicit statements that poetry must be read and heard in the original language, and that colour is essential to the “delight of art”. And I hope you will also see why I am certain that no other artist has ever read Dante so closely as Botticelli, or captured so many of the outward signs of “the colour of the heart”.

Non era ancor di là Nesso arrivato,

quando noi ci mettemmo per un bosco

che da neun sentiero era segnato.

Non fronda verde, ma di color fosco;

non rami schietti, ma nodosi e ’nvolti;

non pomi v’eran, ma stecchi con tosco.

…

Quivi le brutte Arpie lor nidi fanno,

…

Ali hanno late, e colli e visi umani,

piè con artigli, e pennuto ’l gran ventre;

fanno lamenti in su li alberi strani.

…

Ed ecco due da la sinistra costa,

nudi e graffiati, fuggendo sì forte,

che de la selva rompieno ogne rosta.

….

Di rietro a loro era la selva piena

di nere cagne, bramose e correnti

come veltri ch’uscisser di catena.

In quel che s’appiattò miser li denti,

e quel dilaceraro a brano a brano;

poi sen portar quelle membra dolenti.

Presemi allor la mia scorta per mano,

e menommi al cespuglio che piangea

per le rotture sanguinenti in vano.

…

Ed elli a noi: “O anime che giunte

siete a veder lo strazio disonesto

c’ha le mie fronde sì da me disgiunte,

raccoglietele al piè del tristo cesto.

…

Poi che la carità del natio loco

mi strinse, raunai le fronde sparte

e rende’le a colui, ch’era già fioco.

(Inferno 13–14)

FIXME: One or two instances of RED TEXT only.