Giotto: Joachim and Anna

This lecture offers an introduction to the art of the man whom Dante early recognised as the greatest of the Tuscan painters in his lifetime. It will also serve as introduction to the story of Jesus’ maternal grandparents (little known in ex-Protestant countries) and to a famous collection of saint’s lives known as the Legenda aurea, which Emile Mâle regarded as one of the ten books that every would-be medievalist must get to know (it ranked second only to the Bible in terms of the number of manuscripts that have come down to us). Specifically, the lecture concentrates on just fifteen frescos in the Arena Chapel.

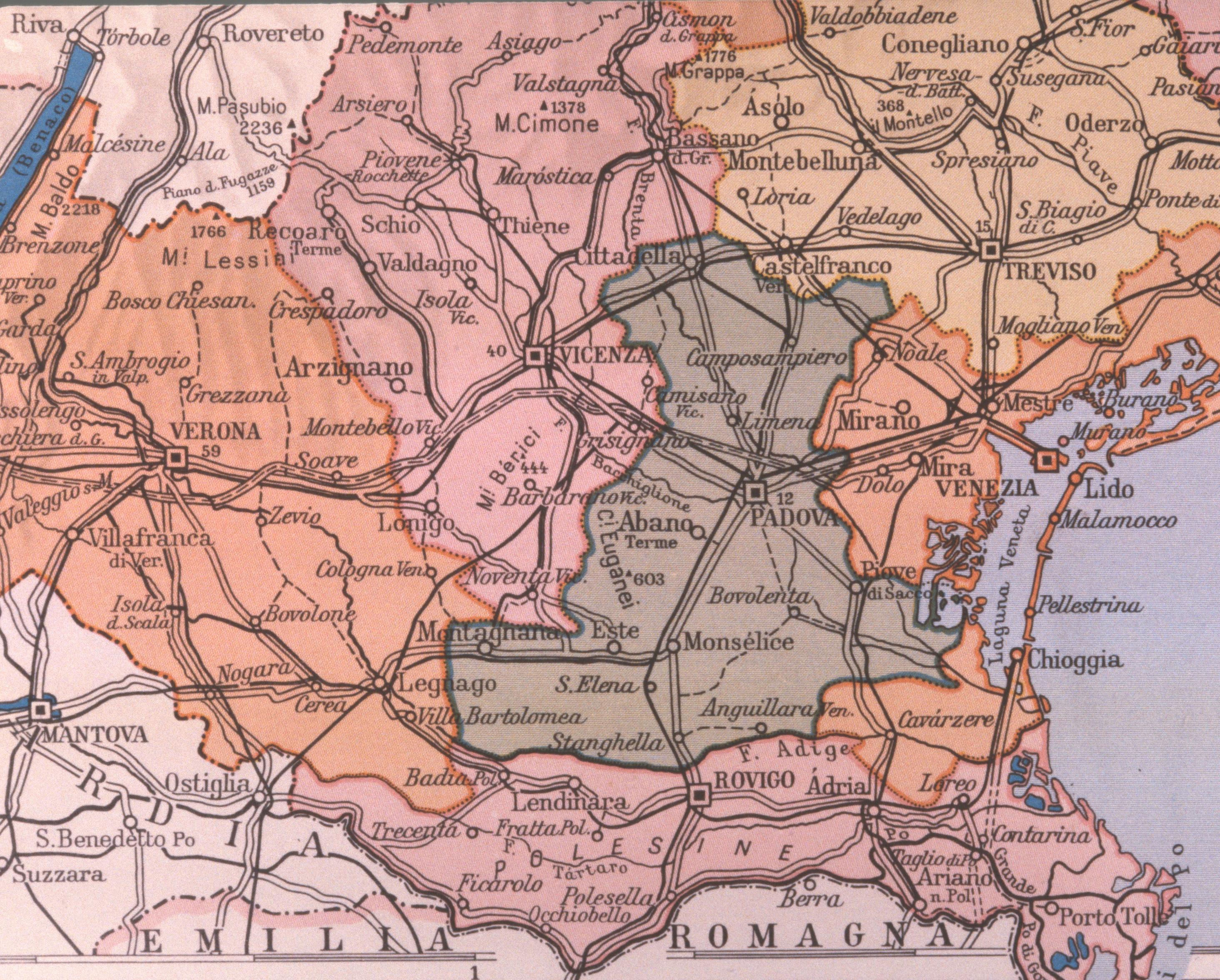

The frescos in question are not to found in central Italy or Tuscany, but well north of the Apennines in the city of Padua, which in Dante’s day was an independent city-state. It lay about twenty miles inland from Venice, and dominated more or less the same area as the modern ‘provincia di Padua’ which is coloured green in the second map.

Like the other city republics in central and northern Italy, Padua owed its political power to economic wealth; and it owed its wealth to industry and trade. Trade in turn was bound up with banking; and banking was inseparable from the loaning of money at high rates of interest—a practice which the church condemned as ‘usury’.

Dante came to know this part of Italy well when he was a political exile in the early 1300s. In one scene from his Inferno, he imagines a meeting in Hell with the souls of a huddled group of Italian usurers (fig. 2), one of whom is made to say that the only member of the group who is not a Paduan is a Florentine! This spokesman is described as carrying a purse which bears the coat of arms (an azure sow on a white field, shown on the right of fig. 3), of a very important Paduan family called the Scrovegni. He is certainly the notorious usurer and miser Rinaldo degli Scrovegni, who died in 1288 or 1289.

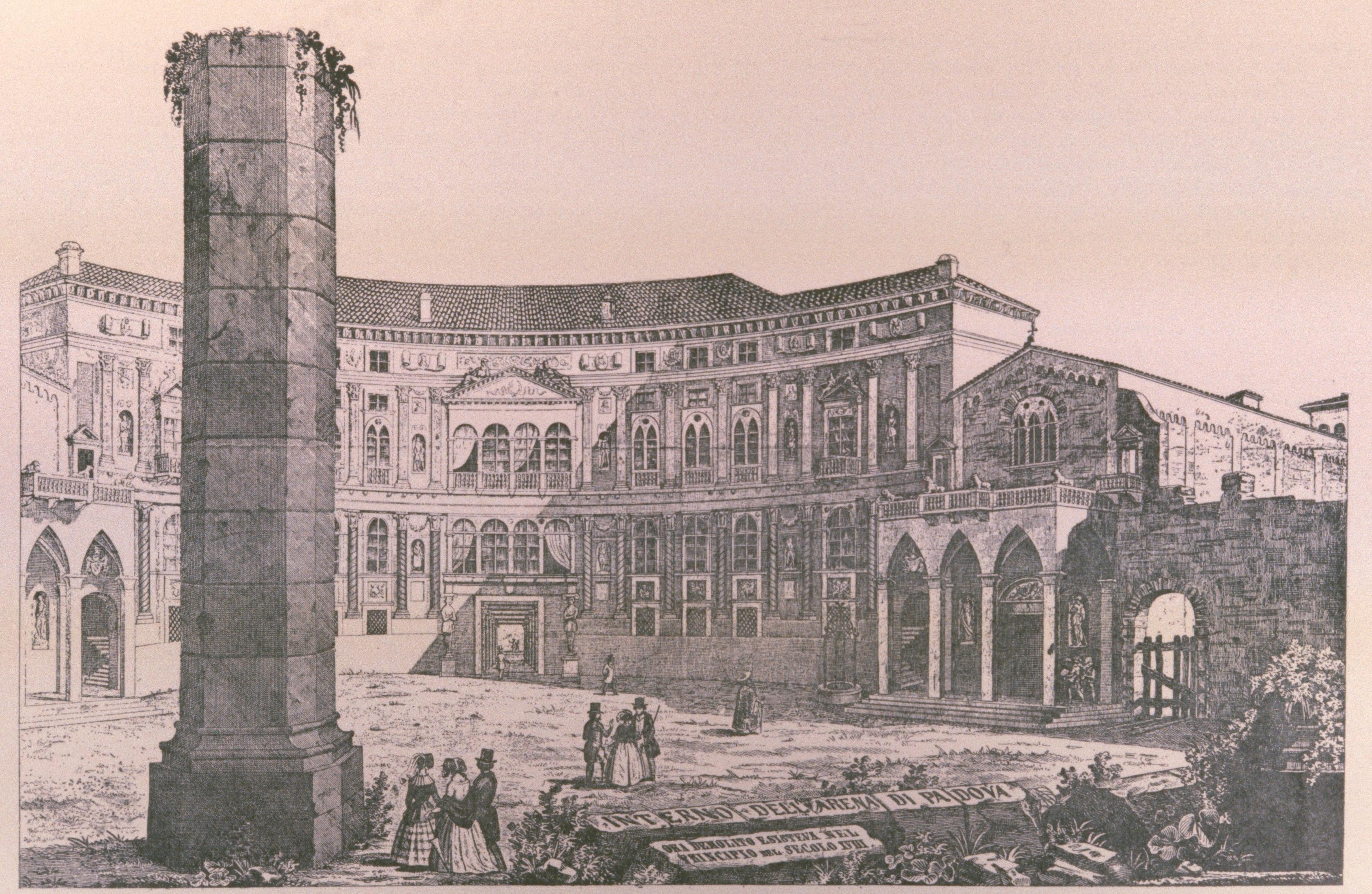

Now the son-and-heir of the very man whom Dante consigned to Hell was called Enrico degli Scrovegni (cf. fig. 5 below). In 1300, he bought a piece of land near the old Roman ‘arena’ in Padua; and there he built a splendid new palazzo for his family, which in the engraving (fig. 3) you can see as it was in the 1840s (it was demolished later in the century).

Enrico resolved to make expiation for his own and his father’s sin (and to proclaim the wealth and prestige of his family) by building a chapel alongside the palazzo, which was to be dedicated to Our Lady of the Annunciation (S. Maria Annunziata) and would replace an earlier chapel dedicated to the Virgin Mary on the same site. It is known to art historians both as the Arena Chapel and the Scrovegni Chapel.

When the building was complete, between 1303–1305, he summoned the Tuscan artist Giotto—who was by then in his late thirties—to decorate the chapel with frescos in which the story of the Virgin would be particularly prominent.

The Chapel survived the demolition of the palazzo and escaped an Allied bombing raid in the Second World War. It now stands alone; but as you can see, it is still very similar (in its shape and the pinkness of its brick) to the model which Giotto painted in the Chapel itself (cf. fig. 5), at the bottom of the fresco of the Last Judgement, where you see Enrico, as the donor, offering the chapel he had funded to the angels).

The chapel was clearly designed primarily as a vehicle for Giotto’s frescos. The natural light which enables us to see the figures comes from six lancets in the south wall, but otherwise every square inch of the internal surface is covered in plaster from the ceiling to the floor, as you can see in the photograph in Figure 00 FIXME, which was taken looking towards the altar.

CUE [FIXME: slide missing]

Every square inch of the plaster was painted while it was still wet or fresh—still ‘fresco’—with the brilliant colours that bonded with the plaster and became part of the wall and the building (although, for technical reasons, the blue had to be applied when the plaster is dry; and little or none of the blue can date back to the fourteenth century).

We are not going to examine more than a quarter of the painted surfaces, but I think we ought to take in the dimensions and the outlines of the whole decorative scheme.

The chapel you are looking into is quite small: about 32 yards long, 10 yards wide, and 13 yards high to the centre of the barrel vault.

The vault (fig. 6) is painted blue, like the sky—or rather, like Heaven, because Italian uses the same word ‘cielo’ for both. It is studded with stars and medallions, and is divided into two halves by a broad ornamental frieze (with heads of prophets and saints inset) which continues down to the bottom of the walls. The walls are clearly divided by horizontal bands into four tiers.

The lowest of the four tiers is painted to simulate panels of coloured marble, which alternate with panels in grisaille (‘grey-scale’, as we now say) which simulate marble statues set in simulated niches. These statues represent, on the north wall, six of the principal vices, and on the south wall, the corresponding virtues. fig. ¿fig:P_G_00? is a composite image showing the central figure on each side, with the quintessential civic virtue of Justice (framed by a modern pointed or Gothic arch) facing Injustice in the person of a tyrant (under an old-fashioned, rounded or Romanesque arch).

RIGHT and RIGHT [FIXME: slides missing]

The upper three tiers are given over to the cosmic drama of Redemption, which runs right round the Chapel. On the north wall there are six scenes at each level, divided by the broad ornamental frieze into groups of three. On the south wall, however, there are six scenes in the highest tier only (again divided 3 + 3 by the broad frieze), because the lancet windows leave room for only five scenes in the second and third tiers (cf. fig. 7)

This is the context for the image I showed you earlier, of the patron presenting a model of his chapel; and it may be that tradition is correct in identifying a face in the group behind Enrico, (cf. detail in Figure 00 FIXME), as a self-portrait of Giotto. However, we cannot be sure of this—just as we cannot be sure of anything at all about Giotto in the period between his presumed date of birth in 1267 and his work in the Arena chapel in about 1305. (There is for example no documentary evidence of his participation in the paintings of the Life of St Francis in the Upper Church of Assisi).

LEFT [FIXME: slide missing]

The story of Jesus is told in five acts: his passion and resurrection in the lower band (Act 5); his infancy and his mission in the middle (Acts 3 and 4), and in the upper band, the story of his mother and of his maternal grandparents, Joachim and Anne (Acts 1 and 2). The drama begins on the Chancel Arch with a separate Prologue, and unfolds in a gigantic spiral to reach its climax next to the altar, with the Descent of the Holy Spirit at Pentecost that marks the beginning of the Christian Church.

In the narrative scene over the chancel arch (fig. 11), which every commentator has to call a ‘Prologue in Heaven’, we find God enthroned amid his angels. We are witnessing a moment towards the end of a long courtroom scene, the story of which was told in the twelfth century by St Bernard of Clairvaux, who expanded a famous couplet from the Psalms: ‘Mercy and Truth are met together; Righteousness and Peace have kissed each other. Truth shall flourish out of the earth; and Righteousness has looked down from heaven’ (Psalm 85, 10–11).

LEFT [FIXME: slide missing]

Mercy and Peace have pleaded on behalf of fallen Man, while Righteousness and Truth insist that Justice must be done. On the right of the throne of God stands the severe figure of Righteousness, Justitia (fig. 12); while the angel kneeling on the other side may be none other than the Archangel Gabriel (Figure 00 FIXME):

This is because God—whom you see in the detail in fig. 13 (which is painted on wood, rather than plaster)—resolved the dispute between Justice and Mercy by agreeing that his only begotten son should take on human flesh (Divine Mercy), and eventually suffer death to make atonement (Divine Justice) and thereby redeem mankind.

LEFT [FIXME: slide missing]

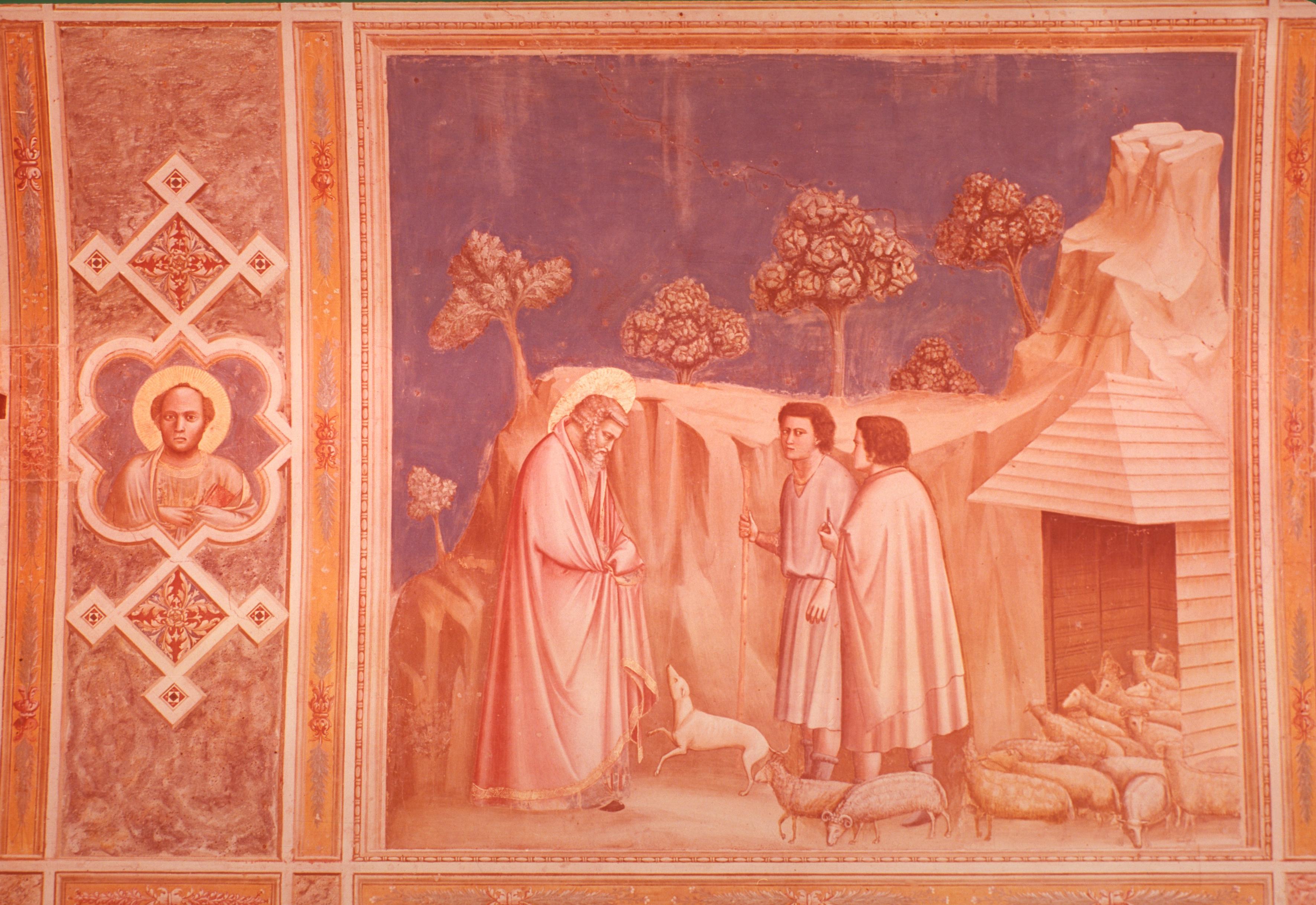

The Incarnation cannot take place immediately after the divine decree, however. It demands a long and careful preparation. Jesus must be born of a virgin undefiled; and the virgin herself must be conceived without sin, that is, without her parents experiencing lust for each other’s body at the moment of conception. This is why the action of the play in the Chapel actually begins—in the highest register of the south wall, immediately to the right of the altar (cf. fig. 10)—with the story of Mary’s parents, Joachim and Anne (fig. 14). The fresco measures about six and a half feet by six.

Before I begin to summarise the story, let me make a few points about the architectural setting within this fresco. On the left, you see an altar topped by an imposing ciborium with a pyramidal roof resting on rounded arches supported by spiralling columns. On the right, outside the marble screen, a flight of steps leads up to a tall pulpit, with candlesticks on the corners.

You will find the same features in a well-known fresco from the St Francis cycle in the Upper Church at Assisi (fig. 15), showing the chancel of a church with its ciborium and pulpit. And I think you will agree that if we were to evaluate the effect simply in terms of the degree of realism obtained by the perspective drawing, the Assisi master (in about 1295) is actually more advanced than Giotto ten years later.

Indeed, the effect of the Giotto is nearer to that of the Assisi master’s model, which you see in fig. 16: a mosaic of the Presentation in the Temple by Cavallini in Rome, done back in the 1280s. Of course, Giotto’s design is more advanced and much more assured than Cavallini. His stairs and pulpit are a ‘tour de force’, his built forms are linked, and either enclose each other, or lie behind each other, rather than being isolated and placed alongside. But there is still more than a hint of double or multiple viewing points; and Giotto is still content to ‘suggest’ the interior of the Temple in Jerusalem with just three props, and to ‘suggest’ an inner sanctuary by a means of the low marble enclosure shaped like an eighteenth-century box pew. Notice also that the whole structure is set on the diagonal, and that the plinth on which Joachim and the High Priest are standing is not parallel to the picture frame. This use of a gentle diagonal setting is never found in the Upper Church at Assisi, but is a recurrent feature of the ‘built forms’ in the Arena Chapel, and is one of the main reasons for doubting that Giotto was responsible for the ‘Life of St Francis’.

**TOM, AS YOU POINTED OUT, I DIDN’T CLEARLY INDICATE WHETHER ANY GIVEN SENTENCE WAS A LITERAL QUOTATION FROM THE GOLDEN LEGEND OR A PARAPHRASE.

IT WOULD BE NICE IF YOU’D CHECK THE PRESENT (AND SUBSEQUENT) NARRATIVES AGAINST MY COPY OF THE GOLDEN LEGEND, AND INSERT QUOTATION MARKS AS APPROPRIATE.

Anyway, now to the story. According to the Golden Legend, Joachim, who was of Galilee and of the town of Nazareth, took to wife Anna of Bethlehem. Both were righteous, and walked without reproach in all the commandments of the Lord. They divided their possessions in three parts, allotting one part to the Temple, and another to the poor, reserving the third part of themselves. Thus they lived for twenty years, and had no issue of their wedlock. And they made a vow to the Lord that, if he granted them a child, they would dedicate it to the service of God.

They went to Jerusalem to celebrate the three principal Feasts of each year. And once, when Joachim and his kinsmen went up to Jerusalem at the feast of the Dedication, he approached the altar with them, in order to offer his sacrifice. A priest saw him, and angrily drove him away, upbraiding him for daring to draw near the altar of God, and calling it unseemly that one who lay under the curse of the Law should offer sacrifice, or that a childless man, who gave no increase to the people of God, should stand among men who bore sons. At this, Joachim was covered with confusion.

We may try to get to the essence of Giotto’s interpretation by comparing his fresco with a later version by Giovanni da Milano in the Franciscan church of Santa Croce in Florence. Giovanni, in the 1360s, is very grand and very assured in his rendering of the architecture; he fills the space with all the kinsmen and kinswomen mentioned in the text; the composition is very symmetrical; and his Joachim is moving out towards us, looking back over his shoulder, the lamb calmly resting in his arm.

Giotto keeps his actors to a minimum. Reuben the ‘angry priest’ and Joachim the ‘childless man’ are shown in full, while the heads of a second priest and of just one worshipper who has brought an acceptable offering are relatively inconspicuous. His simple setting contrasts the enclosure of the sanctuary with a void to the right (where the blue background comes right down to the ground), offering antithetical, powerful symbols of society and the wilderness, of acceptance and rejection. And he concentrates all his attention on the two main figures shown in the detail in Figure 00 FIXME:

RIGHT [FIXME: slide missing]

His human figures are always massively built, thick-set, endomorphs; and his assured handling of tones, from dark to light, makes their bodies seem ‘volumetric’ or ‘cylindrical’. They usually wear, as in the present case, relatively simple unpatterned robes of a heavy woollen material, which either clings to (and models) the body beneath, or simply obeys the law of gravity. The folds are not decorative, not ‘striations’ imposed on the surface in pre-determined patterns. Rather, every fold originates, logically, from a point where the weight of the cloth is supported or checked by a shoulder, a girdle, an elbow, or a clutching hand—and Giotto uses these stark and simple resources for powerful dramatic effects.

The incline of Reuben’s back, the advancing foot that just lifts the hem, the sweep of his beard in profile, his fiercely directed gaze, the huge, broad green sleeve (with the folds emanating from shoulder or uplifted wrist), the way his fingers engage in the pink cloth of Joachim’s robe—all these combine to create an image of rejection or expulsion. Meanwhile, Joachim’s ‘confusion’ is shown with dignity in the twist of his head towards his persecutor, in the earnest gaze that seeks the eyes of the priest, in the puckering of his brow, and in the way he instinctively protects the rejected lamb in his arms (there should be no need to elaborate on the Christian symbolism here). You will see, too, that all the folds in his robe originate from that clutching movement of the arms.

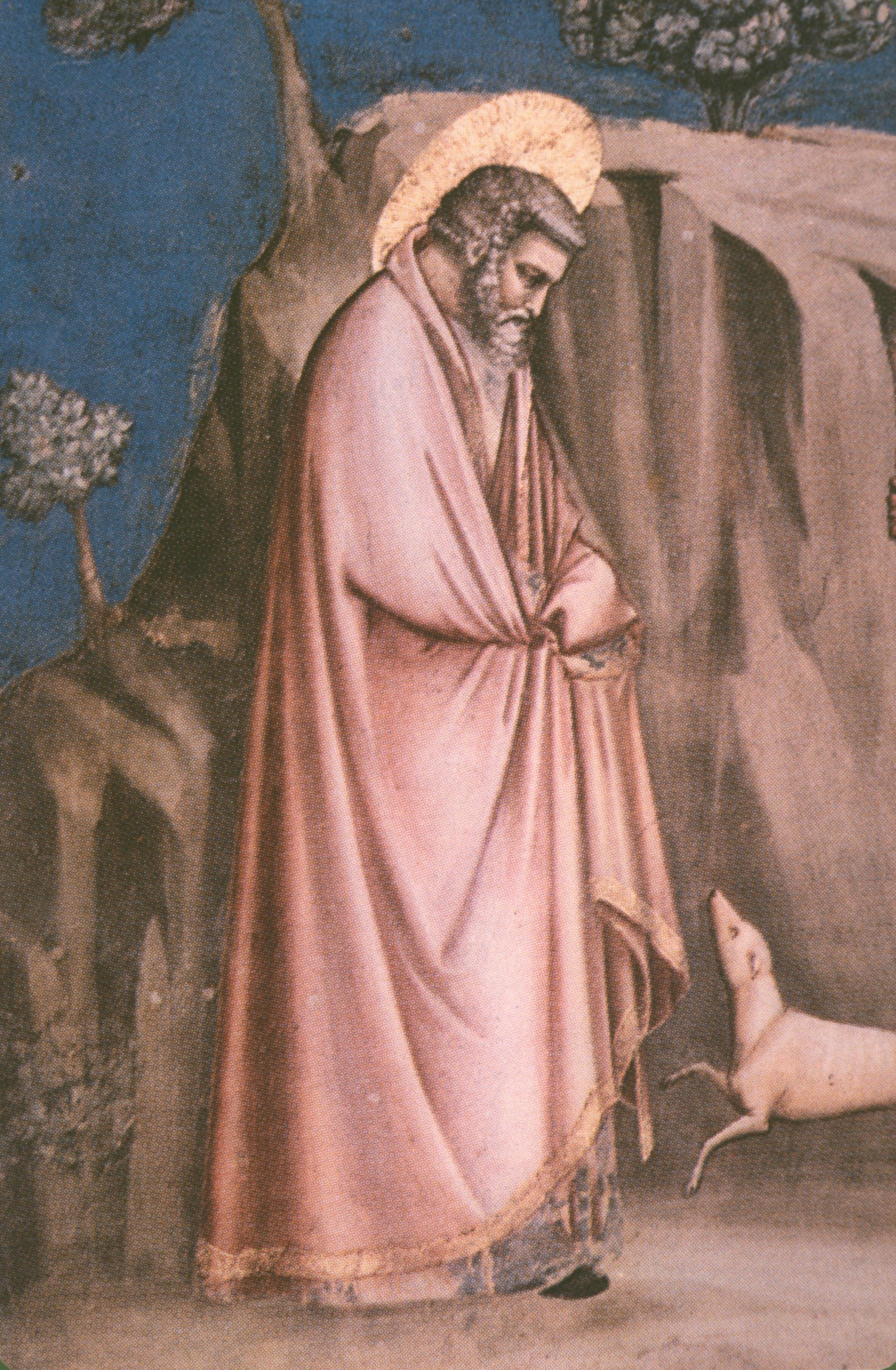

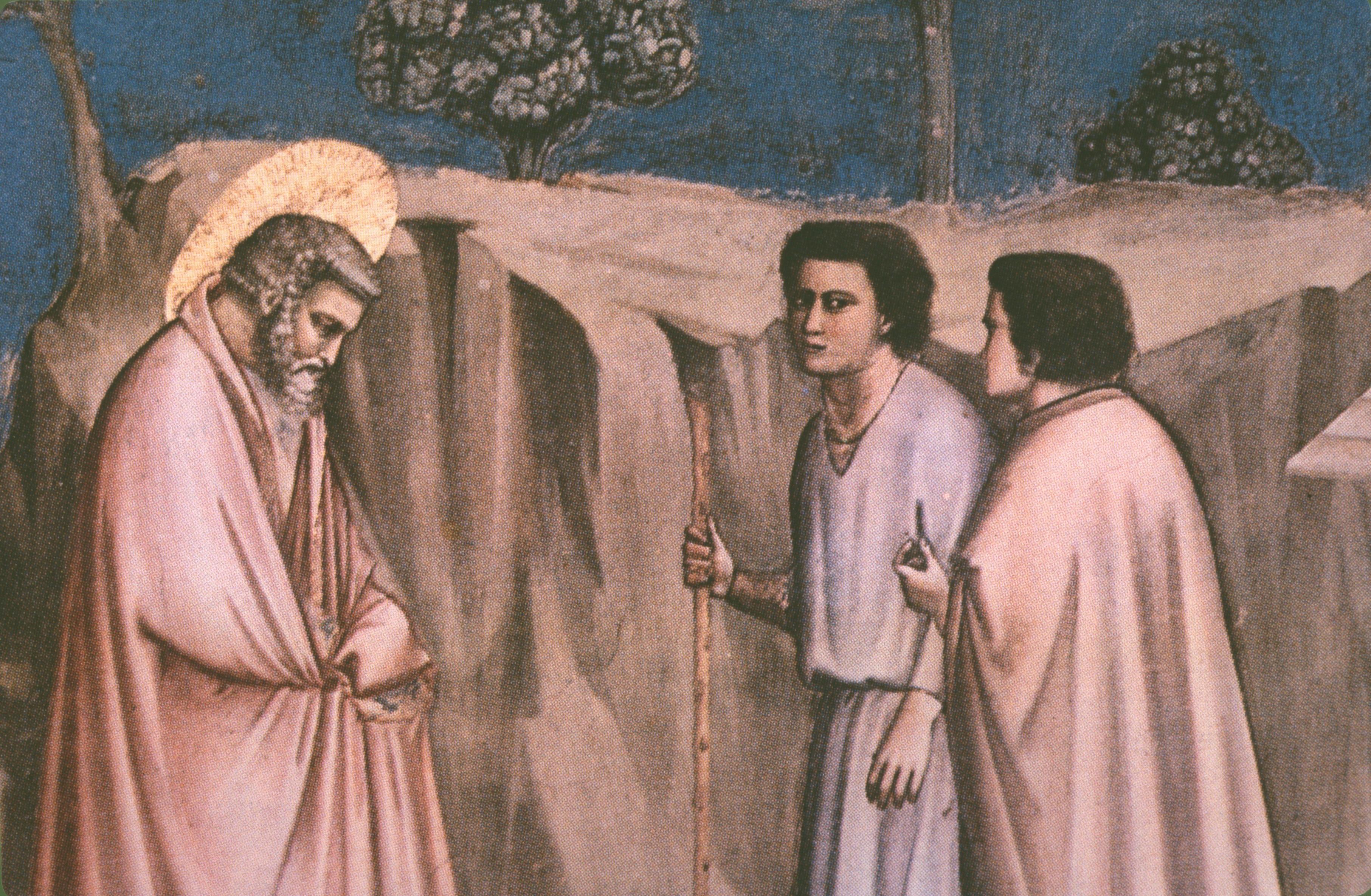

The second scene (fig. 18) continues the thrust of the action from left to right, the story being told in just one sentence in the Golden Legend. Joachim was covered in confusion and was ashamed to return to his home, lest he have to bear the contempt of his kindred, who had heard all. He went off, therefore, and dwelt for some time among his shepherds. ** TOM. PLEASE CHECK TEXT. WAS IT REALLY TWO SENTENCES? PUT QUOTATIONS IN AS APPROPRIATE

The composition, however, is like the opening scene in reverse, with the tall rock on the right answering the tall ciborium on the left. Similarly, the stylised mass of rock in the centre, the simple planks of the shepherd’s hut, and the highly stylised trees symbolise Joachim’s new existential situation, that of a self-imposed banishment, remote from the complex built forms that symbolised the life of a community and the Jewish law.

Joachim advances slowly (cf. detail in fig. 19), his head bowed in suffering under the foreshortened halo, the sad curve of his back emphasised by the edge of the rock behind. But his inner anguish of mind at the very public humiliation is revealed most of all by the folded hands that clutch the heavy robe and motivate the complex folds that lift the elaborate hem and reveal the advancing shoe. His isolation is further emphasised by his indifference to the leaping welcome of the dog, and above all by the body-language of the two shepherds.

Another ‘compare and contrast’ exercise will drive the ‘lesson’ home. What you see in fig. 21 is a tiny panel from the side of an altarpiece done for Pisa in the 1280s. It is totally ravishing in its tonality of reds, browns, golds and pinks, its more impressionistic hills, its hairy sheep, and the hats of the shepherds. However, you could not begin to deduce the story or the situation from the panel, whereas you most emphatically can from the fresco.

The setting of the third scene is neither sacred building nor remote hillside, but the domestic architecture of the matrimonial home—it shows Anne receiving a sort of Annunciation.

RIGHT = Scene 3 [FIXME: slide missing]

In the words of the Golden Legend: ‘Anne wept bitterly, not knowing where her husband had gone. But an angel appeared to her’, and, after reminding her of Sarah and Rachel, who in extreme old age conceived Isaac and Joseph respectively, the angel continued:

‘“You shall bear a daughter, and you shall call her name Mary. In accordance with your vow, she shall be consecrated to the Lord from her infancy, and shall be filled with the Holy Spirit from her mother’s womb; nor shall she abide among the common folk, but within the Temple of the Lord, lest anything evil be thought of her. And as she will be born of a barren mother, so will she herself, in wondrous wise, beget the Son of the Most High” ’.

Finally, the angel added that as a sign, Anne was to go to the Golden Gate of Jerusalem to meet Joachim at his return.

This ‘Proto-Annunciation’ takes place in a splendid but austerely furnished bedroom (exploiting the pictorial convention that a house may consist of just one room with the fourth wall removed). The command of perspective is really quite advanced—the coffered ceilings and the curtains all suggest real depth; and the bedside chest is particularly impressive (cf. fig. 22).

So too is the outer wall, the balcony, and the hitherto unparalleled ladder-like flight of stairs seen from underneath. The whole house—so the roof tells us—is gently tilted towards us on the diagonal; and the angel, too, appears on another diagonal, properly foreshortened (halo and all), and dramatically cut off at the waist.

RIGHT [FIXME: slide missing, detail of Anna]

The maidservant, spinning with her distaff at the door (fig. 23), represents normality and the quotidian (like the shepherds); and the relief modelling of the folds in her dress define the awkward position of her knees quite brilliantly. But it is Anne who dominates, heavy and still, calm and wondering, her uplifted face clearly that of an older woman (look at the crows-feet and her chin), everything being expressed in the praying hands and the set of the profile, which emphasises the intensity of her gaze.

Meanwhile, back on his estate with the shepherds, Joachim makes a burnt offering that is accepted by the Lord, and experiences a parallel ‘Proto-Annunciation’. The Golden Legend deals only with the second scene, telling the story like this:

Joachim went off therefore and dwelt for some time among his shepherds. But one day when he was alone, an angel appeared to him, surrounded by dazzling light. He was affrighted at the vision, but the angel bade him to be without fear, saying: ‘I, the Lord’s angel, am sent to you to announce that your prayers are granted. I have seen your shame, and heard the reproach of barrenness wrongfully cast upon you.’

The angel then makes the same prophecy as he did to Anne, concluding with the same detail:

‘And this will be a sign: when you come to the Golden Gate of Jerusalem, Anne your wife will be there to meet you, she who now grieves at your absence but will then rejoice to see you.’

In the first of Giotto’s scenes (fig. 24a), the sky is blue, two goats are grazing, two sheep are lying down, and the black ram makes advances to the white ewe. On the altar, the flames have already consumed the flesh of Joachim’s sacrifice (cf. fig. 25), and the smoke ascends to be received by the hand of God in the sky above. Your eye is guided upwards by the shepherd’s hands and his gaze, by the slope of the rocks and Joachim’s back, and by the smoke. But the jut of Joachim’s head, his fixed gaze, the ungainly kneeling pose (with the pull of the folds emphasising that the weight is forward on the hands)—all these direct your attention to the angel. He stands upright, wings folded and almost hidden, carrying an olive branch and holding up his head in blessing; and his dress and features closely resemble those of Gabriel in the Annunciation scene later in the story.

The setting of the next scene (fig. 24b and details in fig. 26) is clearly the same as that of Scene Two (but the hut is seen at a slightly different angle, there are no large trees, the rock-mass now turns and slopes to the ground, and the dog is calmly guarding the sheep). The two shepherds (now warmly dressed, against the cold of dawn, with hood up and hat on) now form the vertical of a right-angled triangle, with the line of the rock forming the hypotenuse which is echoed in the sky by the downward flight of the angel, who is conveying a vision to Joachim, (deep in sleep, head on knees, warmly wrapped against the cold).

Another contrast will help to point up the nature of Giotto’s art. In fig. 27, you see the corresponding detail from another fresco cycle in S. Croce (from the 1360s) by Giovanni da Milano. His old man sees the angel and is trying to shade his eyes from its dazzling radiance. But Giovanni’s attempt to convey the emotion of ‘wonder’ or ‘marvel’ is in the event less memorable than the solid mass of Giotto’s ‘dreamer of dreams’.

The last of the six scenes devoted exclusively to Mary’s parents is dominated by the Golden Gate of Jerusalem (notice immediately how the grey city walls are once again set on a gentle diagonal). It was there, according to the Golden Legend, that following to the angel’s command, husband and wife came face to face and shared their joy over ‘the vision which they had both seen, and over the certainty that they were to have a child. Then they adored God, and set out for their home, awaiting the Lord’s promise in gladness of heart. And Anna conceived and bore a girl child, and called her name Mary’. ** TOM, PLEASE CHECK WHAT IS QUOTATION AND WHAT IS NOT

LEFT = scene 6 [FIXME: slide missing]

This is, of course, among the most famous compositions in the whole cycle. One of Joachim’s shepherds provides continuity as he follows his master from the left, boldly cut by the frame to indicate that he has come on a journey. Anna’s attendant ladies advance on the diagonal, four of them clearly smiling and expressing their joy (their faces being typical of Giotto: anatomically still uncertain, hefty, well-fed, unglamourised and unsentimental). Meanwhile the fifth—best seen in detail in fig. 28—is half hidden by a widow’s black shawl, hinting perhaps at the suffering that has been and is still to come.

The first scene shows her birth, which takes place in the same ‘house-cum-bedroom’ that we saw in the Proto-Annunciation on the opposite wall:

RIGHT = detail, or closer view, of the people and things in the room [FIXME: slide missing]

The treatment is slightly more archaic: for example, the bed is now tilted towards us in the old-fashioned way, as though seen from a different, higher viewpoint; and there are two moments from the same story in the same frame, because it is the same baby girl who is being washed in the foreground and presented to its mother behind the bed.

RIGHT [FIXME: slide missing for first detail]

The language of gesture, however, is as clear as ever. In Figure 00 FIXME, look at the midwife who is cleaning the gubbins from the new-born baby’s eye, supporting Mary’s head and using her large peasant’s hands with such delicacy. Or, in fig. 32, look at the upward and left-to-right thrust of the woman in white who comes to the door to offer a gift; and then look back at the whole fresco to register how her gesture lets the action flow through the door-opening, across the room and into the main scene (where the attendant offers the swaddled baby as the most precious gift) until the movement is finally arrested by the vertical stresses of Anna and the bed-curtain behind her.

We can also jump forward 40 years, to the large panel by the Sienese painter Pietro Lorenzetti, which has some dazzling effects of perspective, and two very convincing midwives in the foreground; but which dissipates attention by the division of the surface into three and by bringing in Joachim (FIXME: or Zacharias?) on the left, and signally failing to concentrate on the woman in late middle age who reaches out her arms to hold her long awaited and miraculous first baby.

RIGHT = scene 2 of this block [FIXME: slide missing]

The setting of the second episode in the story of Mary’s Childhood also returns (with a concern for narrative continuity that would have seemed strange fifty years earlier) to the architecture of a scene on the south wall, taking us back to the Temple in Jerusalem and the beginning of the whole drama (cf. fig. 14 above). But this is a stroke of genius. We see the space within the temple from the other side of the marble screen. The high pulpit is now in the centre (without its candles and with its stairs and banister going the other way), while the roof of the ciborium is now on the right of the composition. More important, the action now flows up into the Temple, towards a priest who is extending his arms in welcome. This time the sacrifice is ‘acceptable’; and the sacrifice is Mary herself.

As the Golden Legend relates:

When the Blessed Virgin was three years old, her parents brought her with gifts to the Temple of the Lord. Around the Temple there were fifteen steps, and the Virgin, being placed upon the lowest of these steps, mounted all of them without the help of anyone, as if she had already reached the fullness of her age.

Giotto has followed iconographical tradition rather than the Legend in making Mary rather more than three years old (she is nearer the age of Confirmation); the steps are ten not fifteen; and Anna is very definitely giving her child a hand. Notice yet again how clear the gestures are—the mother’s body, head and arms proudly offering; the arms of the red-robed priest, Zacharias, spreading in welcome; Mary’s arms crossed in humility, as she will be seen in the Annunciation.

Once again, the composition is based on a right-angled triangle, with the hypotenuse lengthened by the porter’s shoulders at the bottom and extended or reinforced by the heads of the spectators above. It is completed by the pinnacle of the ciborium (the architecture is rarely there in Giotto as mere background), while the vertical axis of the triangle on the right is reinforced by the two elders, one with his back to us, both huge, stock still (as their robes confirm), like solid blocks of stone, their eyes interlocking, commenting on the significance of the presentation, and gesturing to call attention to the central scene.

This is the last episode in which Joachim or St Anne play a part; and we must now press on to study the remaining four scenes in this section of the north wall, which tell the story of Mary’s betrothal to Joseph.

The architectural setting becomes extremely simple and will remain virtually unchanged for the two subsequent scenes (as the needs of the narrative dictate). A semi-circular arch, (almost but not quite) centralised within a tall rectangle, acts as a frame to the front of a simple altar (hung with a richly patterned cloth). We are finally inside the Temple; and the officiant behind the altar is none than the red-robed Zacharias (later the father of John the Baptist), who is joined by Reuben, the priest in green, the one who banished Joachim in the opening scene. The story, as told in the Golden Legend, goes like this:

When she had come to her fourteenth year, the high priest announced that the virgins who were reared in the Temple, and who had reached the age of their womanhood, should return to their own, and be given in lawful marriage. The rest obeyed the command, and Mary alone answered that this she could not do, because her parents had dedicated her to the service of the Lord, and because she herself had vowed her virginity to God. The High Priest was perplexed at this. When the elders were consulted, all were of the opinion that, in so doubtful a matter, they should seek counsel of the Lord. They all therefore joined in prayer, and a voice came forth from the oratory for all to hear, and said that of all the marriageable men of the house of David who had not yet taken a wife, each should bring a branch and lay it upon the altar; that one of the branches would burst into flower; and upon it the Holy Ghost would come to rest in the form of a dove—and that he to whom this branch belonged would be the one to whom the virgin should be espoused.

In the first stage, Giotto nicely catches the clear, eager gestures of the younger men as they bring their branches to the altar—note especially the one in blue—while Joseph—identified by his halo, older, bearded (very like his future father-in-law)—hangs back diffidently, holding his branch vertically. In fact, the Legend tells that on the first occasion, he did not put his branch with the rest, and that nothing happened.

The next episode follows immediately, in the same space (fig. 37). Everyone is kneeling, and the urgent gazes of the main flock of suitors on the left (with modest Joseph almost hidden at the rear) guide our eyes to the three figures closest to the altar (Zacharias and two of the suitors), who form a typical a pyramid which finds its apex in the lesser pyramid of branches on the altar: and in this very moment, Joseph’s branch bursts into flower, and the hand of God appears in token of the miracle.

The Golden Legend spoke not of the ‘hand’ of God, but of a ‘dove’ which descended from Heaven and perched on the tip of the branch. Giotto, however, holds this back for the following scene, still in the same part of the Temple, which is that of the promised Betrothal, where you can see the dove on Joseph’s flowering branch:

The unlucky suitors are plainly vexed (as the iconographical tradition required). In a classical pose, like a senator in a toga (fig. 39) one of them remonstrates; a younger man snaps his branch over his knee (a knee defined by the cloth, as you can see); while the blue-gowned youth who had stretched forward so ardently now raises his arm in protest. But the reactions of the suitors are relatively restrained, and the architecture isolates them from the main group where, once again, the gazes of the attendant woman and even the folds of Joseph’s mantle and Mary’s white wedding dress lead our eyes to the hands and the placing of the ring.

[FIXME: pat: there is no detail of the main group, I’m afraid]

RIGHT = the final scene [FIXME: slide missing]

The last scene on the wall shows Mary, having left the Temple, returning to her parents’ house in Nazareth (Joseph having gone back to Bethlehem to make arrangements for the wedding). It is here, says the Golden Legend, that the Angel Gabriel was soon to appear and make the Annunciation (whence the colossal palm branch in the window).

Mary is accompanied, as the Legend requires, ‘by seven virgins of her age who had been nurtured with her and whom the high priest had given her as companions because of the miracle’; and the procession comes to a halt when the two trumpeters among the musicians turn round to face the player of the rebec. The effect is of perfect calm and serenity, and the very beautiful figure of Mary is given prominence in the whole design through a combination of unobtrusive devices—she is central; her foreshortened halo makes her appear slightly taller than her companions; her dress is much lighter in colour, and the folds created by her left hand are more complex. Above all, she is isolated by the perfect judgement of the spaces that separate her from her companions.

An English spectator is almost bound to think of John Keats and his ‘still unravished bride of quietness’. She is indeed a ‘foster child of silence and slow time’; and Keats may also help us to catch the ‘unheard melodies’ of the musicians, who ‘pipe to the spirit ditties of no tone’. An Italian, though, would surely think of some of Dante’s early poems, written perhaps ten or fifteen years earlier—for instance, the opening of a sonnet, which reads:

Di donne io vidi una gentile schiera

questo Ognissanti prossimo passato,

e una ne venia quasi imprimiera;[^1]

Of ladies I saw a lovely group

this last All Saints’ Day

and one of them came almost at their head;

Or else, the loveliest of all the sonnets regarding Beatrice in the Vita Nuova:

Tanto gentile e tanto onesta pare

la donna mia quand’ella altrui salute,

ch’ogne lingue deven tremando muta,

e li occhi no l’ardiscon di guardare.

Ella si va, sentendosi laudare,

benignamente d’umiltà vestuta;

e par che sia una cosa venuta

da cielo in terra a miracol mostrare.[^2]

So gentle and so full of dignity appears

my lady when she greets anyone,

that every tongue trembles and falls dumb

and eyes dare not look at her.

She goes her way, hearing herself praised,

graciously clothed with humility,

and seems a creature come

from heaven to earth to make the miraculous known.

Notice the gothic windows of the house in Nazareth, the projection above, and the ornament on its panel below—for they are the frame for our next picture of Mary which lies on the right of the chancel arch (fig. 41b):

Meanwhile on the left (fig. 41a)—in a mirror image of the setting, complete even down to the space-creating swags of the curtains—the angel Gabriel comes to make the Annunciation. I will not dwell on this; but notice that Giotto is no longer concerned to make Mary beautiful, slender and aristocratic, as she had been in the Procession. Here, she has already come to resemble her mother: strong, heavily built, grave, with her hair now pulled close round her face in tight plaits.

This is how we see her too in the little scene immediately below (Figure 00 FIXME), which links the Annunciation on the chancel arch to the middle register of the south wall (fig. 42), which tells the story of Christ’s Nativity.

This is the ‘Visitation’, when Mary, who has now conceived, is visited by her much older cousin Elizabeth (wife of Zacharias the high priest), who is six months pregnant with the future John the Baptist. It is at this point that I want to stop, partly because the story takes us back to that of Anna and Joachim, but mostly because this small scene is the very purest Giotto. All you see, and all you need to see, is a portico, three attendants, and two pregnant women—with St Elizabeth, the older and the higher-ranking woman (she is the wife of a priest, not the wife of a carpenter), stooping awkwardly and heavily in reverence, as she looks up so intently into Mary’s eyes, and touches the womb which she knows contains the son of God.

*************

THE ORIGINAL OPENING (INTRO. TO GOLDEN LEGEND)

LEFT and RIGHT [these images of Francis pertain to an introductory paragraph which I have edited out. ** TOM: WE MADE NEED THAT PARAGRAPH, IN SOME FORM. The sequence of ideas seems to be: 1. Everyone is familiar in outline with the mission and character of St Francis and the Francisan friars. 2. There was another, less well-known, exactly contemporary Order of Friars, the Dominicans, with a similar role and mission. 3. This lecture will be shadowing a very influential book written by an early member of this second order, a Dominican who died as Archbishop of Genoa in 1298. This superbly organised and clearly written compilation became an authoritative handbook used by many artists when they were called on to paint narrative cycles dealing with the Bible or the lives of the Saints…

…I must now remind you that Francis and his Order of ‘Lesser Brothers’ were not alone in their evangelical mission. They had indeed been preceded by a Spaniard called Dominic, who was born twelve years before Francis in 1170 and had taken an active part in trying to re-convert the Albigensian ‘heretics’ of southern France in the first decade of the thirteenth century. Dominic was moved to found his ‘Order of Preachers’ in 1216 (again, before the ‘Frati Minori’) in order to perform a similar task in the booming cities of northern Italy, which had become seed-beds of popular religion that might easily depart from orthodoxy.

LEFT

The ‘Brothers Minor’ and the ‘Preachers’—Franciscans and Dominicans—were often in keen and acrimonious rivalry, whether in the faculty of theology at the University Paris in the 1260s, or in city-republics like Florence, where the Dominican church of S. Maria Novella, begun in 1279, is no less colossal than the Franciscan S. Croce, begun in 1295. Nevertheless, it was a commonplace of official hagiography and propaganda—duly reflected in the very long account of the two saints and the two orders in cantos xii and xii of Dante’s Paradiso—that the two saints were different but complementary: both were ‘champions’ of the Church and mediators of the True Word, of the Gospel of Salvation. You seem them symbolically in these roles here, in the altarpieces from the 1260s in Figure 00 FIXME.

One of the most influential of the first generation of friars in either order was born in the town now called Varazze, on the Riviera, in 1228 (the year when Francis was canonised). He died in 1298 as archbishop of Genoa, and it is there you see his effigy lying in state on his funerary monument in Figure 00 FIXME.

RIGHT and LEFT

He is usually called—with a double Latinisation of his given name and the medieval name of his birthplace– Jacob of Voragine. He entered the Dominican order in 1244; and at some time in the 1260s (the decade when Dante and Giotto were born), he compiled what came to be called The Golden Legend—Legenda aurea—which the great historian of medieval art Emile Mâle regarded as one of the ten books you have to assimilate if you wish to understand medieval civilisation.

There are over 700 surviving Latin manuscripts, and the book became a best-seller in the early days of printing. In figs. ¿fig:P_G_00?, ¿fig:P_G_001?, ¿fig:P_G_002?, you see a Latin text published in 1474, a page from Caxton’s translation and edition of 1483, and a Venetian edition from the year 1494.

RIGHT and LEFT and RIGHT

James himself referred to his compilation as Legenda Sanctorum (where legenda is a substantified neuter plural adjective meaning ‘things to be read’—just as agenda originally meant ‘things to be done’). It consisted of a series of texts to be read aloud, as aids to devotion, on each of the major Feasts in the liturgical year (it is in fact arranged in calendrical order, beginning with the season of Advent). About 150 of the Feasts for which James makes provision are dedicated to individual saints, and this is why the Legenda Sanctorum was often used by artists when they were asked to paint a cycle of stories illustrating a Saint’s life. In this lecture, I hope to show just how carefully a major artist would follow and interpret the text.

FIXME: RIGHT

The woodcut in Figure 00 FIXME purports to show Brother James at work in Voragine in the 1260s, but FIXME

FIXME: Also search for “**” and “00”.