Paradiso 2

FIXME: This lecture was first given in the week of a new moon.

Then, I implored my audience to bear my words in mind as they watched it

getting rounder and rounder; becoming both brighter, as more and more of

its surface are illuminated by the sun, but also darker, as more and

more of the ‘craters’ and ‘seas’ are exposed, until they began to see

why people used to tell stories about a ‘Man in the Moon’. It was then

the twenty-fifth anniversary of when man first set foot on the moon, a

time marked by copious press coverage, and pieces concerning attempts to

discover whether there is ‘intelligent life’ elsewhere in the

universe.

These things were mentioned for a specific purpose: in order to challenge the commonly held view that Dante’s Paradiso is necessarily more ‘remote’ from us than his Inferno. For the facts of the matter are that there is no Hell underneath the earth, that it will never be possible to make a ‘Journey to the Centre of the Earth’, and that very few of us believe literally in the existence of Satan or in eternal punishments after death. Whereas, the action of the first 29 cantos of the Paradiso describes an interplanetary space flight on which the first staging post will be the moon, which you can see with your naked eye on most evenings, and where we know that it is possible for a man to land.

The canto that is our topic touches on themes relevant to us, such as the curvature of space, the relation of mind and matter, the nature of knowledge, and, especially, the relationship between experimentation and abstract thought in science, and comes to the conclusion that there is indeed ‘intelligent life’ in the planets and stars, or, at least, that they are ‘regulated’ by intelligent beings.

For reasons of time, I am not going to say anything about the opening 18 lines, and next to nothing about the space flight which has been carrying Dante and Beatrice upwards from the summit of Mount Purgatory through the sphere of Fire, with no other propellent than the ‘concreated and perpetual thirst of the godlike kingdom’.

We shall pick the story up at line 25, where Dante realises that he has come to a halt, because an amazing or awe-inspiring phenomenon (‘mirabile cosa’) draws his eyes towards it, and therefore away from Beatrice. She, however, reads his thoughts, and reassures him by telling him that God has ‘conjoined’ them with the ‘first of the stars’, which, in the geocentric system was, of course, the moon.

‘Meraviglia’ is normally dispelled by the discovery or the explanation of the causes of the strange new phenomenon that produced the emotion; but in this case the explanation should intensify our sense of astonishment. To the protagonist it seemed as if he and Beatrice had been ‘covered’ by a cloud—except that, contrary to the experience of hill walkers, the cloud is ‘solid’ and is shining like a diamond glittering in the sun. The author explains (I stress the author, because the second terzina shows the advantage of hindsight) that they had penetrated the body of the ‘eternal pearl’—a lovely metaphor for the moon—as effortlessly as a ray of light penetrates water, without splitting, displacing, or otherwise changing the ‘pearl’ (which if it were capable of change, would not be ‘eternal’).

At this point you might say: ‘Wait a moment!’ Dante had emphasised in the first canto that he himself was there ‘in the body’, in flesh and blood. The moon is solid and dense, and is therefore a body. A body (‘corpo’), by definition, occupies three dimensions, and therefore occupies space. And as Aristotle had proved in his Physics, which is the science of ‘bodies’ in nature or of ‘natural bodies’, it is impossible for two bodies to be in the same place at the same time. So Dante interrupts the narrative, which he has only just begun, in order to congratulate you on your ‘puzzlement’, and to offer some clarification.

Yes, he was in the body; yes, he does know that a body has ‘dimensions’; yes, he does mean that the two bodies were in the same place; yes, he does know that one dimension cannot ‘suffer’ another, because they are not ‘compatible’. What he is here describing is not simply ‘marvellous’—that is to say, strange and as yet unexplained but, in principle, explicable. Rather, it is miraculous—that is, explicable only on the assumption that God has intervened directly, and that the laws of natural causation have been suspended.

In these nine lines (19–27), Dante seizes the opportunity to allude to a whole series of interlocking propositions about the human intellect and its different ‘ways’ of arriving at the truth; and these propositions form the ‘ground base’, so to speak, of innumerable ‘variations’ in the rest of the poem. So it will be worth our while to spell them out. Briefly put, human understanding begins in the senses, especially in the sense of sight (‘vedere’), when a strange phenomenon (‘mirabile cosa’) excites the emotion of ‘meraviglia’, or ‘maraviglia’, also called ‘ammirazione’. It involves an element of direct intuition, though limited to the so-called ‘first truths’, or first principles, such as the self-evident axiom (‘per sé noto’) that a whole is greater than one of its parts.

Most characteristically, however, the act of understanding is the result of a laborious process of discursive reasoning—step by step deductions from these first principles or from earlier conclusions, as when we ‘prove’ a geometrical theorem (which is what is meant by ‘demonstration’ in line 44). In the study of theology, the process begins in an acceptance on trust, or by faith, of truths concerning God that human reason could never ‘demonstrate’—for example, that Jesus Christ was fully human and fully divine. And, finally, all our learning and all our understanding includes a hope, based on the foregoing, that it will one day be possible—when we have reached the ‘deiforme regno’—to see all truths by direct intuition, without reasoning, and without the need for faith: ‘Lì si vedrà ciò che tenem per fede’.

As I have already said, the rest of the poem will dramatise all these components in the intellectual process of discovery, making them, in fact, the main substance of the poetic action; and the ‘desire’ (40) kindled by the miracle will be finally ‘stilled’ or ‘satisfied’ only in the very last lines of Paradiso, which describe how Dante was granted direct vision, direct intuition, of the Union of Man and God in Christ. Which is to say that there are no ‘digressions’ in Dante.

The very complex meditation which I have just paraphrased belongs to Dante-the-author at the time of composition, and it is very different from the immediate thoughts of Dante-the-protagonist, who assures his lady that he is properly grateful to God for ‘removing him from the world of mortality’, and then promptly asks a question arising from his memory of how the moon appears on earth, when seen from the ‘mortale mondo’.

Up here, he notes, the moon is ‘shining’ or ‘clear’—‘lucida e pulita’—while from earth, its ‘body’ (50) seems to have many dark marks or signs (‘segni bui’), marks which gave rise to numerous fables about the punishment of the first murderer in human history, Cain.

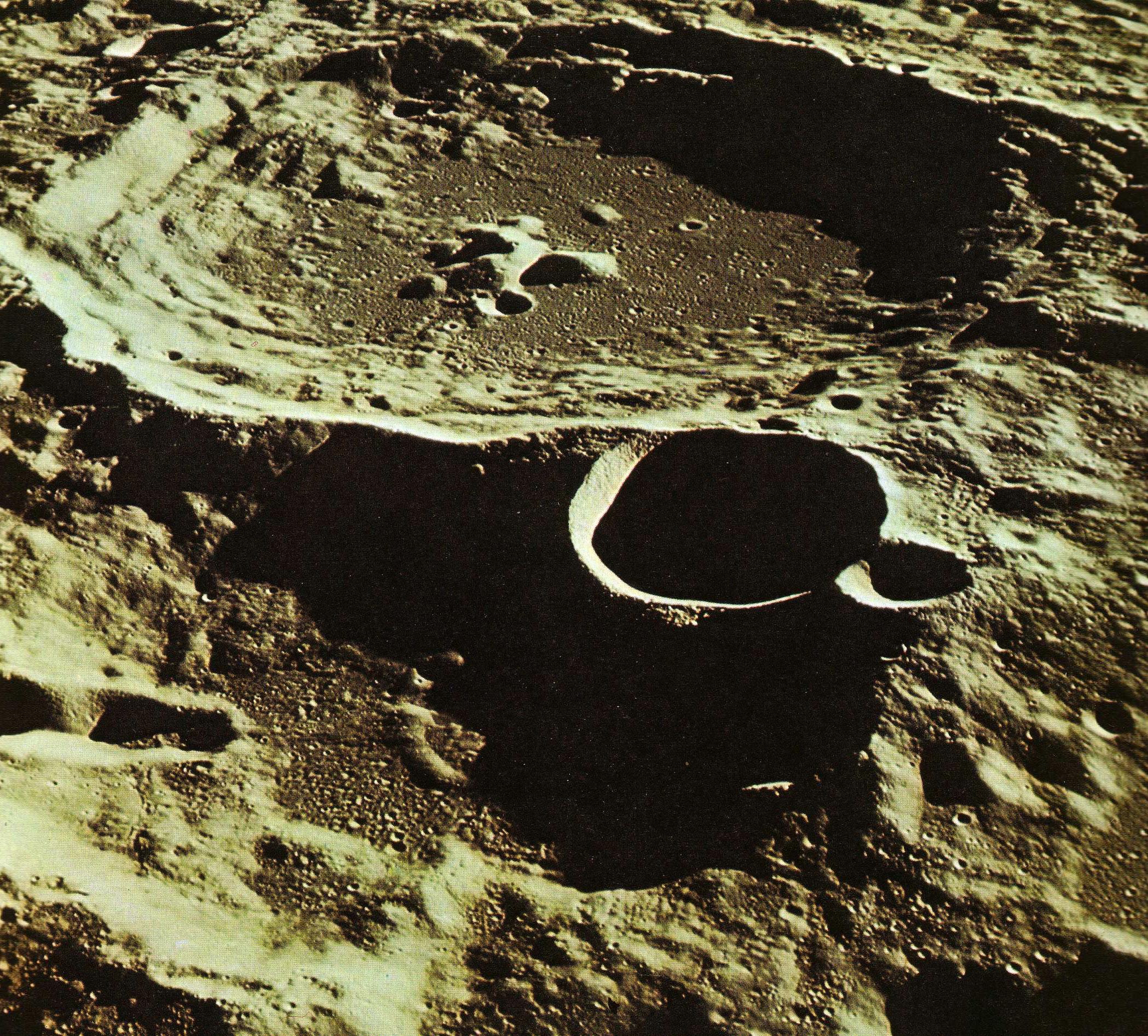

To us, today, the true cause of these markings is immediately apparent if you pick up any pair of binoculars you happen to have lying around at home, and go out and look at the moon. The dark patches are ‘seas’ or ‘craters’, and look like this (fig. 2a) when seen from a spacecraft:

They are laid out irregularly, as you can see from the map, but there is a marked concentration to the north, with downward extensions to the west and in two ‘lobes’ to the east. You will remember that the moon always shows us the same face, which is to say that the distribution of the seas is readily visible to the naked eye, and if we were to draw what we see, it would look much like the chart in fig. 2b.

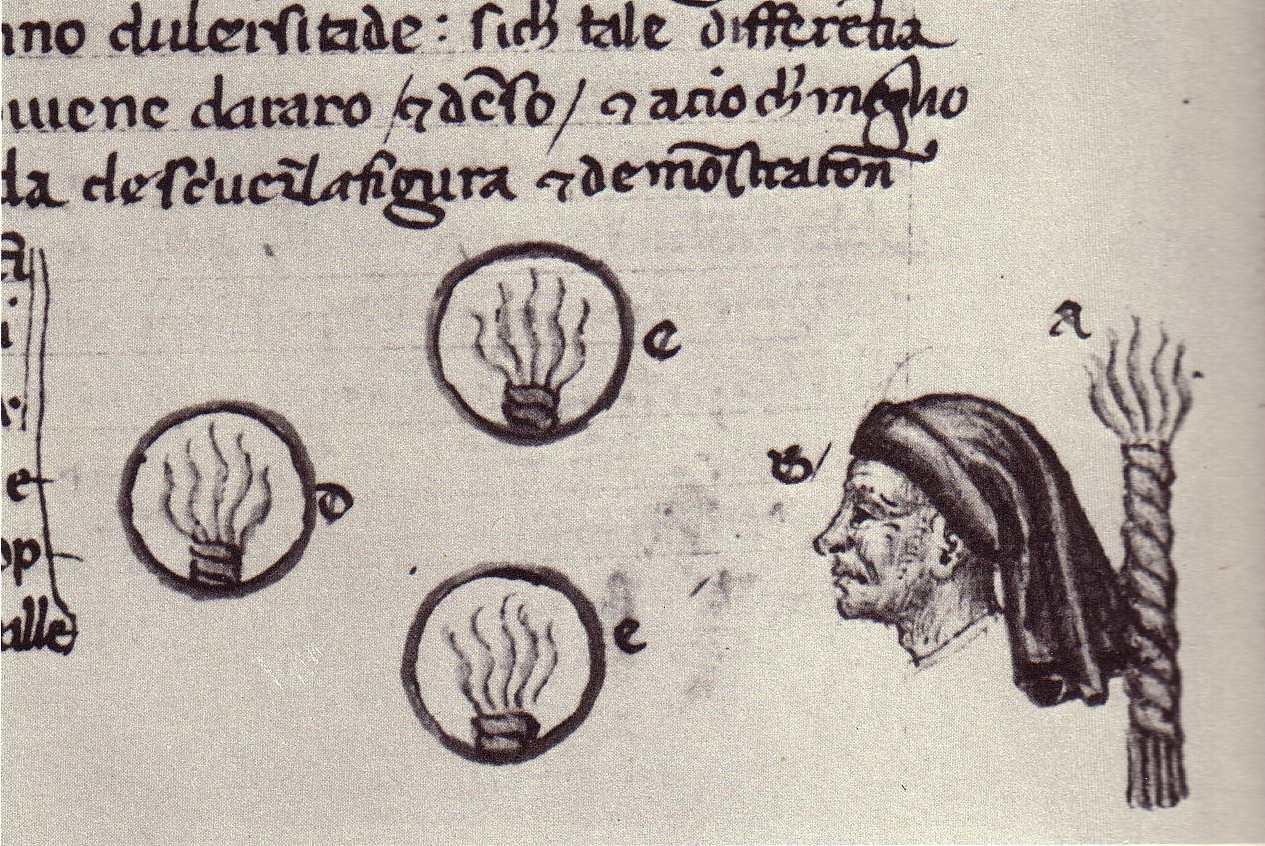

Medieval observers, however, were more fanciful. Jean de Meun, the author of the second part of the Romance of the Rose who was writing in the 1270s (about 40 years before Dante) said that people thought they could see a ‘marvellous beast’, comprising a serpent, with a tree on his back, and, on the tree, a man:

Et la part de la lune occure

nous represante la figure

d’une trop merveilleuse beste:

c’est d’un sarpent qui tient sa teste

vers occident adés ancline,

vers oriant sa queue affine;

seur son dos porte un arbre estant,

ses rains vers oriant etant,

mes en estandant les bestourne;

seur ce bestourneïz sejourne

uns hon sus ses braz apuiez,

qui vers occidant a ruiez

ses piez et ses quisses andeus,

si conme pert au semblant d’eus.

(Le roman de la rose, 16851–64)

One of the illustrators to our canto (the same 14th-century artist whose brilliant representation of space flight we saw earlier) shows us a leaning man, with the tree—the ‘thorn bush’ of which Shakespeare speaks—apparently growing out of his [** OR its; CHECK back. (Or perhaps he may be showing a serpent, tree and a man, as stated in the Romance of the Rose.)

Beatrice smiles at Dante’s question about the dark marks, which to her illustrates the frailty of human reasoning even when it has reliable sense-data as its point of departure. (Lines 52–57 are a development of some of the themes of Dante’s authorial meditation earlier in the canto). Then (58), like a skilled teacher, she asks her pupil for his personal opinion: ‘quel che tu da te ne pensi’.

There are three points to notice about the protagonist’s very brief reply (59–60). First, he generalises his answer (and therefore the scope of his original question) so that it includes all variations, all diversity in the celestial regions (‘qua sù’ meaning ‘up here’). Second, the answer he gives was a highly respectable one, which had the authority of scholars like Albert the Great; it had been adopted by Jean de Meun, and also been accepted by Dante himself at the time of writing his Convivio. In his prose work, he had explained the underlying reasoning:

L’una si è l’ombra che è in essa, la quale non è altro che raritade del suo corpo, a la quale non possono terminare li raggi del sole e ripercuotersi così come ne l’altre parti.*

(Convivio II, xiii, 9)

Third, he implies that the moon is a ‘body’, ‘corpo’, and therefore the object of study of natural science or physics; but he seems to forget the most fundamental principles of Aristotle’s Physics. The mistake in the reasoning is exactly that which Aristotle had exposed in the pre-Socratic philosophers. These ‘ancient, natural philosophers’ had the intuition, the correct intuition, that there was just one ‘stuff’ underlying all the bodies in the sublunary region: that is, that all bodies and all their transformations on earth had just one principium materiale. These ‘natural scientists’ had gone wrong, however, in assuming that all existing things were generated by rarefaction or condensation (generari secundum raritatem et densitatem). They had posited ‘rarified’ and ‘dense’ as the basic formal principles—principia formalia—whereas, for Aristotle, rarum et densum sunt qualitates.

At this point I must digress to say something about the concepts of ‘form’ and ‘property’ in Aristotle’s thought, since these will dominate the beginning and the end of Beatrice’s reply, where they appear as the words ‘principi formali’ and ‘virtù’. In Aristotle’s physics each ‘natural body’, each corpus, every existing, material, three-dimensional object or being, owes its existence to its ‘structure’ or ‘substantial form’, for which another possible synonym is principium formale. Aristotle also held that each corpus or ‘substance’ possessed certain natural ‘powers’ or ‘properties’, some passive, some active, simply as a necessary consequence of the way in which its matter was structured. The active powers—often called ‘virtues’ or virtutes—are known through their perceptible effects on neighbouring bodies with which they come into contact.

The other correlative of ‘form’—‘matter’, materia—is simply a necessary abstraction. It is that which is ‘structured’, that which clearly survives in any ‘transformation’ when a new body is generated, but which never exists except under some structure or other. A principium materiale explains nothing. It does not account for why bodies exist, nor for what properties they have, nor for what effects they produce.

So, to reiterate, and to make the link with our canto: the concepts of structure and property are inseparable. There is no form without properties. Every distinct form must have some distinct properties (although, obviously, many properties are shared), and any two bodies with distinct properties must be distinct in their structural principle, and vice versa.

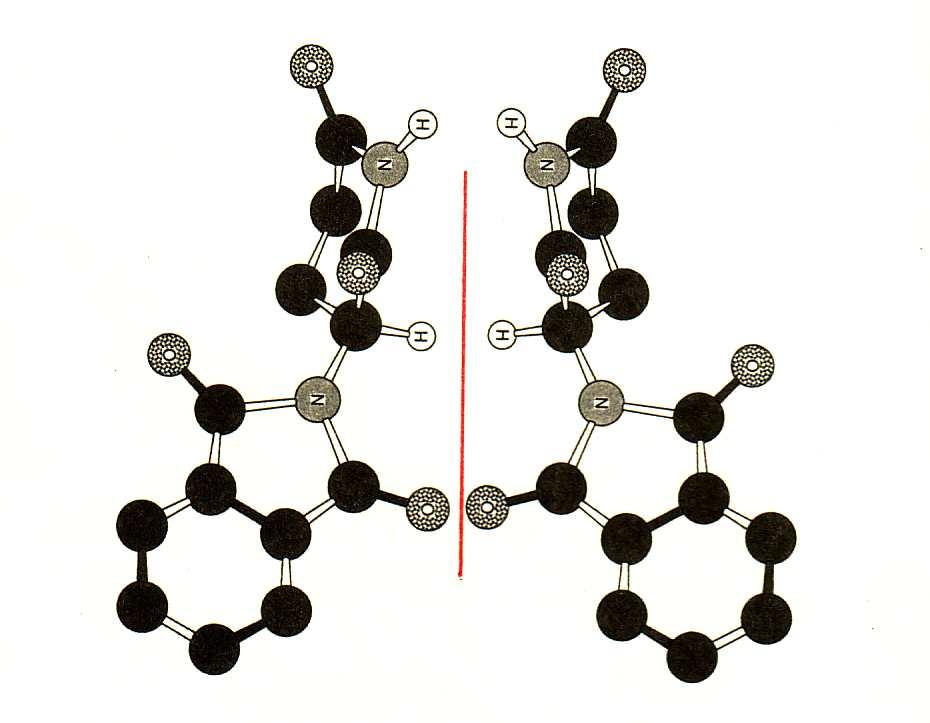

If this nexus of ideas sounds familiar, it is because it is still the basis—mutatis mutandis—of the chemistry you learnt in the first form at school and of the latest chemical research. If you put pieces of litmus paper into two colourless liquids, and one turns the paper blue, the other red, you know you are dealing with two different ‘substances’, with two different ‘formal principles’. The pre-eminence of structure—in Aristotle, as in modern science—can be illustrated by the idea of ‘handedness’ or ‘chirality’, which, I am given to understand, is very much a central concern of modern chemistry.

Our two hands are mirror images of each other. If I look at my right palm, and the reflected image of my left palm, they are identical. This means, however, that the two structures cannot be superimposed—try it. It also means that my left hand will not fit into my right-hand glove, or that a mirror image of my Yale key will not open my front door. Now, in many complex substances, especially synthesised ones, the component atoms of the molecule can arrange themselves into mirror images of each other, so that there are left-handed and right-handed molecules. Below is one such molecule—made up of atoms of carbon, hydrogen, oxygen and nitrogen—showing its ‘left-hand’ form, alongside its mirror image, the ‘unsuperimposable’ right-handed version, or enantiomer, which also exists:

It is the molecule of the drug thalidomide. Studies have suggested that it was the right-handed molecule which acted as a sedative, but was otherwise innocuous, while the left-handed molecule turned out to have appalling effects on the unborn child1. Different forms, different properties, different effects.

With these ideas in mind, let us return to our canto (61). Beatrice accepts Dante’s generalisation of the question by applying his argument to the eighth sphere, the one with ‘molti lumi’—that is, the stars in their constellations—which are self-evidently different in size (‘nel quanto’) and in their properties (‘nel quale’). (Here, you must remember that Dante’s contemporaries would have accepted that the effects of Capricorn and Cancer on man were as self-evidently different as those of an acid and an alkali on litmus paper). Such effects, Beatrice continues, are produced by active powers—‘virtues’ (68, 70). These are inherent in the structure or form (70–71); and different powers point to different forms, or formal principles. If Dante were correct, if all diversity were due to ‘raro e denso’ (67), this would imply that all the stars, and indeed all the planetary heavens, would produce the same effects, because they all had the same formal principle. The falseness of the consequence demonstrates the falseness of the assumption.

This is followed by a separate line of argument (73ff), which is limited to the moon. If Dante and Jean de Meun were right, and if the dark patches (‘bruno’, 73) correspond to areas of low density (‘raro’), then it is theoretically possible (as Jean specifically said) that the pockets of low density extend all the way through the moon to the other side (‘oltre in parte’, 74). On this hypothesis, the sun’s rays would simply travel through the moon exactly as they do through transparent glass (and, again, Jean had specified ‘verre transparent’). But if this were really the case, it would become evident during an eclipse of the sun (80), when the moon passes between the earth and the sun, because the sun’s rays would shine through from the rear to the front. This does not happen (‘questo non è’, 80, 82)—as you too may confirm from this photograph of a total eclipse:

So the theory expounded in the Romance of the Rose has been ‘broken’, and shown to be ‘false’, as Beatrice says in line 84. The other possibility, referred to in lines 76–78, is that the areas of high and low density—rarum et densum—are distributed in layers, like the fat and the lean in animal flesh. But in this case, says Beatrice, there must be a ‘termine’ (86) formed by a layer of denser matter sealing off a pocket of rarefied matter (which is its ‘contrario’, 87). Hence the sun’s rays would still be reflected ‘from this point’, (88), ‘indi’, and thus the area in question would be no less bright than those others where the surface itself was ‘solida e pulita’.

On this hypothesis, in fact, the moon would be exactly like a mirror, as described by Jean de Meun. The rays of colour (or of coloured light, as we should say) which emanate from my face, are invisible in the atmosphere and still invisible (or only faintly visible) if I cut them off with piece of clear glass. But if that glass were to be coated with lead (‘piombo’, 90) on the rear surface (‘retro’, 90), the coloured rays, or the colour (89), would return from the hidden metal, so that I could see my face in order to help me shave. Dante the character may, however, be hampered by one last ‘objection’ (‘instanza’, 94): perhaps the affected area is ‘dark’ (‘tetro’, 91) precisely because it is reflected from further back (‘refratto più a retro’, 93); and everyone knows that light gets fainter the further it is removed from its source.

However, Beatrice promises to make short work of this objection through the ‘experience’ of the senses (‘esperienza’, 95), or, as we would say, through an ‘experiment’, which she goes on to describe. (Note too, in these two lines, that knowledge begins with ‘experiment’ or ‘experience’ in Aristotelian science, no less than in modern science.)

The experiment involves not just one mirror but three, and requires the fairly careful placing of a flame. I have taken the trouble of following Beatrice’s instructions, and photographed the results, so that you may judge the matter for yourself. Any Fellow of my college in Cambridge (St John’s) who reads about reflections and candles will immediately think of our Combination Room, which is a typical Tudor Long Gallery, where we dine during the vacations amid a gleam of polished wood and silver. It is a room—to quote a line later in this canto—that ‘many lights make beautiful’ (‘cui molti lumi fanno bello’):

I was delighted to find, in the circumstances, that the long exposure required to make the slide (fig. 5) transformed all the candles into stars.

Passing to the far end of the room, I followed the very clear instructions given in Dante’s text. I set out three mirrors of equal size, arranging them so that two were equidistant from my position (which was outside and to the right of the image in fig. 6), while the third mirror lay at a greater distance between the other two:

I then looked at the three reflected images of the candle and considered their size and brightness—their ‘quanto’ and their ‘quale’.

As to the ‘quanto’, it was obvious that the distant image was smaller than the other two (the fifteenth-century diagram is wrong in that very crucial point). With regard to the brightness, the ‘quale’, however, you may judge for yourselves:

I put a camera where my head had been and took three exposures, the first (top) at 32 seconds, to show the mirrors and the gleam of the candles on the silver, the next (middle) at 8 seconds, and the third (bottom) at 2 seconds. For myself, I am reasonably happy that Beatrice has a fair point. To the unprejudiced eye, the middle reflection does look about as bright as the outlying reflections, whether at 2 seconds, at 8 seconds, or at 32 seconds (where the ‘star-effect’ which is so appropriate to our canto becomes very pronounced).

Now that you have seen the experiment for yourselves, let me translate Dante’s description of it as literally as I can, so that you can enjoy the marvellous concision and clarity of the language that Dante took over from medieval science:

You shall take three mirrors

and remove two of them from you in one way,

and let the other, further removed,

find your eyes between the other two.

Turning towards them,

see to it that behind your back there stands a light,

which illuminates the three mirrors

and comes back to you reflected from them all.

Although in magnitude

the more distant image does not extend so far,

you will see that it must shine out equally.

(Paradiso 2, 97–105)

Alas, I shall have to deny you my thoughts on the splendid simile (106–111) which marks the moment of transition from refutation to assertion, from weeding out to planting anew, and from a relatively plain and restrained style to some of the most beautiful and evocative poetry that Dante ever wrote. This is because the last 37 lines of our canto are conceptually quite difficult, and I need the time to give you the necessary introduction.

Let me resume by reminding you that Dante and Beatrice are now inside the moon, and that the subject under discussion is the ‘dark signs’ on the surface, considered as part of the general problem as to what causes diversity in the celestial regions. The conclusion to be reached is simply a restatement of the Aristotelian axioms that we met in the first part of the refutation, although this time the emphasis is reversed. A brief glance at the last lines of the canto will show us the direction in which we are heading:

Virtù diversa fa diversa lega

col prezioso corpo ch’ella avviva,

…

Da essa vien ciò che da luce a luce

par differente, non da denso e raro;

essa è formal principio che produce,

conforme a sua bontà, lo turbo e ’l chiaro».

(Paradiso 2, 139–148)

The differences between dark and light (148), or between star and star (145), are caused by different ‘virtues’ (139), different powers; and these are the consequences of different structures, different ‘formal principles’ (147), and not of density or rarity (146).

However, the steps that lead to this conclusion widen the discussion to show us all the heavens of the Ptolemaic universe as a single system; a single system for the production of effects here on earth. The differences between the heavens, or between their parts (as in the case of the many stars in the eighth heaven or the dark patches on the moon), are shown to be differences of function or purpose. Each is a different ‘tool’, or ‘machine’, with a distinct effect to produce. The underlying message of the whole speech is that the diversity of species and individuals here on earth, below the heavens, is good. And diversity is good because it is willed by God, beyond or above the heavens, who created, and who now maintains, a multiplicity of species in order to reveal the infinity of his power within the limitations of a finite universe.

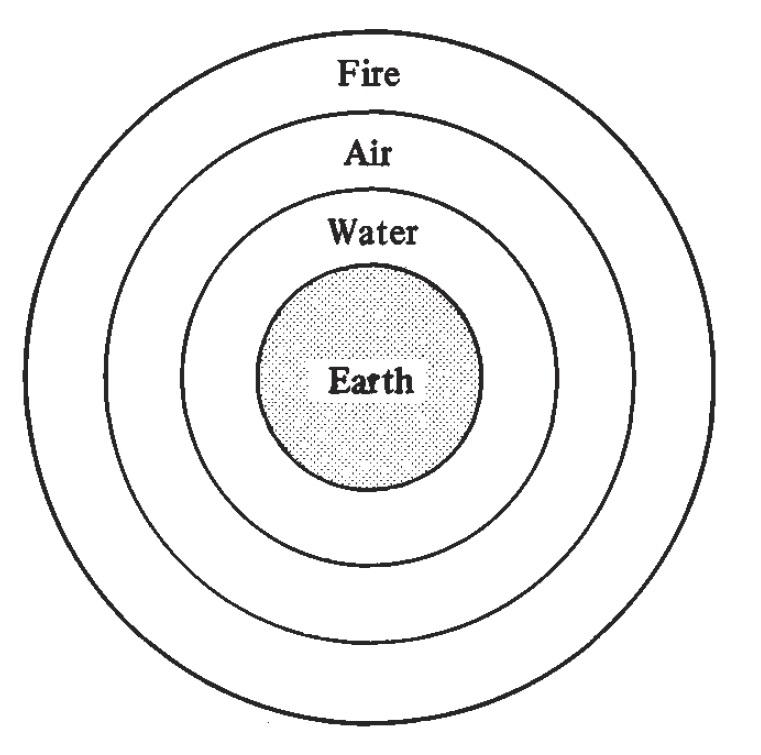

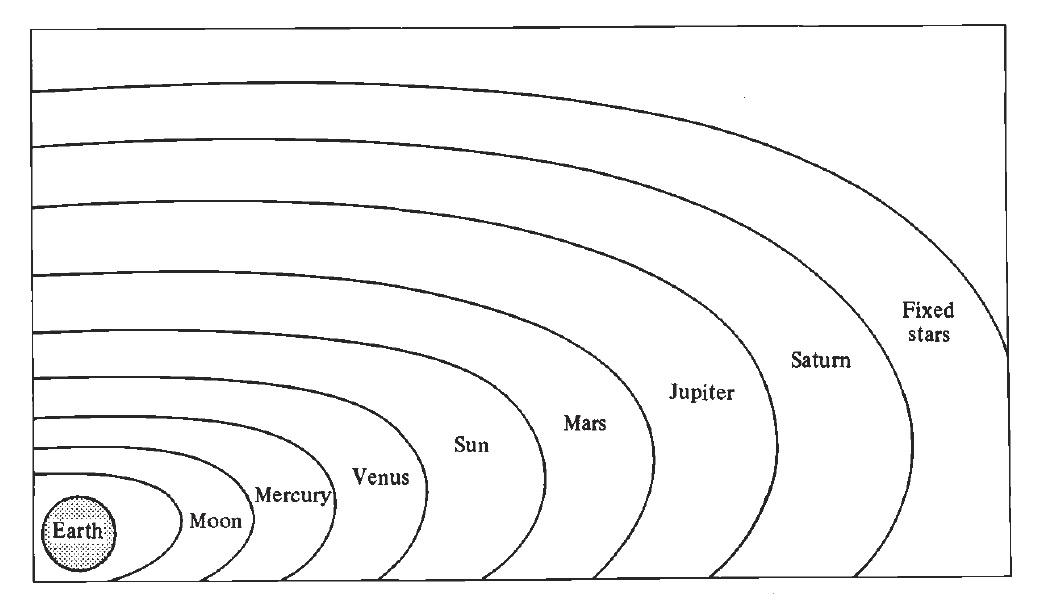

Let me remind you very quickly of Dante’s mental picture of the universe, beginning at the centre:

The core consists of the motionless sphere of Earth. This is surrounded by the other three elements, which would always have remained in their separate spheres (thanks to the difference in weight or lightness) if they had not been ‘mixed’ by an external agent (Dante will elsewhere say by the stars). Or, to put it more precisely, Water, Air and Fire would have remained separate, if all four elements had not been brought into contact, on or near the surface of our globe, in order to enter into the many compounds that underly plant and animal life.

Around these four spheres, arranged like the skin of an onion, are eight further spheres composed of a fifth element called aether. The first seven of these carry one planet each, while the eighth has many constellations:

Each of these eight spheres—here reduced to two dimensions—has the power of self-movement from west to east (or, rather, of movement on an inclined plane from south-west to north-east) in periods which range from one complete revolution in 29 ½ days (in the case of the innermost heaven) to one degree in a hundred years in the case of the eighth.

Outside these, there is a ninth sphere, also composed of aether, which has no ‘luminaries’, and which is perfectly uniform. It, too, is capable of self-movement. It revolves in the other direction, east to west, about the vertical axis, completing one revolution in just short of 24 hours; and—crucially important—it sweeps all the inner heavens around with it, which is why the sun goes from east to west every day. This heaven is called the ‘first moving thing’ (‘primum mobile’), and it is the containing body. Everything else is located within it, while it is contained or located only in God’s mind, or ‘in God’, or, to put it another way, in a ‘heaven’ beyond space and time called the ‘Empyrean’, eternally still, which Dante will call the ‘heaven of divine peace’.

These are the ideas that Dante will transform into great poetry in lines 112–14:

Dentro dal ciel de la divina pace

si gira un corpo ne la cui virtute

l’esser di tutto suo contento giace.

(Paradiso 2, 112–14)

There simply is not time to explain at length how Dante conceived the so-called ‘influences’ or ‘impressions’ raining down to earth from the planets and stars; however, it is important to know that it was generally assumed that each planet, or each constellation, did cause effects analogous to those which we still attribute to the sun. This influence was carried in the rays of light; and the movements of the heavens brought these different influences to all parts of the earth every day (thanks to the primum mobile), but in ever different combinations and altitudes (thanks to the proper movements of the inner heavens on their inclined plane). This is what Dante means in line 127 by ‘lo moto e la virtù d’i santi giri’.

Having summarised these facts, we may return to the text. In the first four terzinas of this final section, Beatrice describes the order of the heavens (proceeding from the outside towards the centre). She indicates the Empyrean (112), the primum mobile (113–14), the heaven of the stars (114–17), and the seven planetary spheres, considered as one group (118–20). She ends by insisting (121–3) that all the physical heavens (including the primum mobile) are collectively ‘instruments’ or ‘tools’ (‘organi’) of the universal system, which produce their effects in the world below, but receive their ‘programme’ and their ‘energy’ from above—and ultimately, therefore, from God.

Simultaneously, however, and especially in lines 116–19, Beatrice is insisting on the increasing ‘diversification’ or ‘differentiation’ which is the true subject of her discourse. At each stage of the ‘descent’—of the ‘journey’ from the circumference to the centre—the gift of being as such is ‘resolved’, ‘divided’, ‘distributed’ or ‘distracted’ into distinct kinds or species, and, finally, into individual bodies. (The crucial words are ‘parte’, ‘distratto’, ‘differenze’, ‘distinzioni’).

This brings us to lines 127–148, which for me, personally, are the most fascinating and challenging in the whole canto—where Beatrice approaches the question of how the heavens move, or are moved, which will also imply an answer to the question I mentioned at the beginning: ‘Is there intelligent life in the heavens?’

Clearly, there is a mind involved—a ‘deep mind’ (131), which, later (136), will be called an ‘intelligence’—because it would be just as absurd to attribute all the complex ordered effects of Nature to the heavens considered simply as bodies, as it would be to attribute the existence of a ploughshare to a hammer (‘martello’, 128) rather than to a smith (‘fabbro’). Clearly, too, in each case the mind is acting in conformity with God’s will. Hence, the ‘motori’ (129, the efficient causes of movement) may be called ‘beati’ (129). But the key question in Dante’s time was this: did the ‘deep mind’ act from outside, like a boy using a whip to keep a top spinning, or did it act from inside, like a boy spinning himself round, using his own legs and arms?

In the first case, the heaven would be moved ‘by another’ (ab alio), and the movement would be called ‘enforced’, or ‘violent’. In the second case, the heaven would be moved ‘by itself’ (a seipso), and the movement would be ‘natural’.

In this second hypothesis, however, the heaven itself would have to be alive, that is, it would have to be ‘animate’. And the ‘intelligence’ or ‘deep mind’ would be identical with its ‘soul’—its anima (because anima is simply the technical term for the ‘formal principle’ of a self-moved being).

There is not enough time to go into this complex matter in more detail, but I would like to draw your attention to the very explicit comparison (‘come…così’) between the different constellations of the eighth heaven and the ‘differenti membra’ of the human frame, each of which has diverse powers within a unity (‘unitate’ 138), a comparison which leads—via another explicit parallel drawn between life in the human body (141) and life in the ‘precious body’ of the heaven (140)—to the marvellous simile of the penultimate terzina:

Per la natura lieta onde deriva,

la virtù mista per lo corpo luce

come letizia per pupilla viva.

(Paradiso 2, 112–14)

Just as human joy (144) shines through the ‘matter of the eye’, so the light of the stars is an ‘outshining’ of the ‘virtue’ which derives from a ‘joyful nature’—that is to say, from the ‘formal principle’ or structure of the eighth heaven. We have already summarised the conclusion of the argument, culminating in the two words that refer explicitly to the moon—‘the dark and the clear’—which are linked, in the last line of the canto, with the key word in the underlying theme, namely ‘goodness’. Diversity is willed by God, and it is therefore good.

All that remains now is to read the canto aloud in the original Italian, for such a reading constitutes another kind of commentary, a way of suggesting the formal organisation of the language, the beauty of its sound, the variety of mood, and the emotional impact on the reader.

In preparing this lecture, I did take the conscious decision that I would not ‘apologise’ for Dante’s ‘outmoded’ science and philosophy, and that I would try to get the listener to appreciate the interest and coherence of his ideas. To that end, I produced the facing-text translation which prefaces this, which was intended to be intelligible and credible as a piece of twentieth-century English prose. But no one is more acutely aware than I am that what you can read on the right-hand side is like the right-handed molecules of my earlier example.

It gives you the same ideas, arranged in the same sequence, but it will pass quite innocuously through your system without leaving any trace. It is the left-handed molecules, in the left-hand column, which are ‘in conformity with the goodness of the formal principle’ that Dante gave them. Poetry exists as a ‘formal structure’—it is the left-hand column that may modify your feelings and modify your brain.

FIXME: Also search for “**”, and deal with the following:

NOTES FOR DISCUSSION:

- How to present the text of the canto; in its entirety or interspersed at points in the lecture?

Remember the page layout of the Cambridge Readings in Dante’s Comedy (CUP) I showed you

- Style guidance for embedded Italian terms, uses of italics/quotation marks (at present typewriter quotes throughout.

Italian words or phrases in single quotes. Latin words italicised.

No double quotes except within a quotation.

- Section on Patrick Moore cut as neither the slides nor the powerpoint presentation hold the amateur drawings.

OK

- The passage of Aquinas In Phys. not reproduced entirely, again so we can discuss whether necessary, or best footnoted.

I MAY WELL FEEL THAT WE NEED A SLAB OF LATIN, BUT WILL DECIDE LATER

- Second manuscript miniature cut.

OK

- The images of the hand have not been included, as the image seems vivid enough from the text (but of course can be added if needed).

IT READ WELL WITHOUT.

- A footnote has been added to the discussion of thalidomide to bring the discussion up to date, which sadly muddies the metaphor somewhat.

SEE MY NOTE AD LOC.

- Photograph of a manuscript illustration which began the section on the last 37 lines has been excluded - as it is unclear whether the one in the Powerpoint I have is the correct one.

LEAVE ME A CUE SO THAT I CAN COME BACK TO IT.

- Do you want to replace the latter image of Dante’s cosmos with that saved in the folder under the title ‘dantes universe 3’, which while less elegant shows the primum mobile in addition to the eight spheres.

I’LL TRY AND SCAN THE CANDIDATES, FROM THE ORIGINAL ENGLISH OF MAN IN THE COSMOS, AND FROM THE AD HOC HANDOUT FOR THE LECTURA

- I have done my best to reproduce as counsel to the reader your last section of the presentation, the reading aloud of the canto, though obviously this is less than straightforward.

THIS SECTION WILL NEED TO BE RECAST, BUT CAN BE LEFT FOR NOW, WHEN I’M STILL TRYING TO OFFER A VERSION OF A LECTURE EVEN THOUGH THE TEXT HAS BEEN LIGHTLY EDITED.

- Throughout the typescript as it currently exists are references to the lack of time, in glossing over certain parts of Dante’s work (which nevertheless are accorded significance in your discussion). Do you think an Ergänzung on these points might be worthwhile, or is there another way to make these glossings-over more elegant in a written form?

THE LATTER, I THINK