Michelangelo: The Last Judgement

As was hinted at the end of my previous lecture, the cultural and religious climate in Rome in the second half of the 1530s, when Michelangelo returned to the Sistine Chapel to paint the Last Judgement on the Altar Wall, was very different from that in about 1510 when he frescoed the ceiling, or from that in the 1480s, when Pope Sixtus built the chapel that bears his name, and began the decorations that we have been studying—decorations with a visual and conceptual unity that would now be rudely disturbed.

This disturbance was not unrelated to the new cultural climate, which, in turn, was not unrelated to the profound changes that had occurred on the political map of Europe and of Italy.

The story that I have to tell—very briefly—is that of a pope who did not understand the changed reality; who put his political interests, as ruler of the Papal States, before his duty of reforming the Church; and who behaved exactly like a temporal ruler, entering into short-lived alliances and hiring mercenaries to make war—more or less as Sixtus and Julius had done in their time.

He was a Medici, and he took the name of Clement VII when he was elected pope in 1523.

Alas, his luck did not hold for long. After the disastrous defeat of the French at Pavia in 1525, Clement formed a league with the newly ransomed king of France against the emperor.

Both sides hired their mercenaries; the two armies converged on Mantua late in 1526, and the Emperor’s general won. The victorious army then marched on Rome, and in May 1527 took the city at the first assault, putting it to the sack, and looting and desecrating monuments on a totally unprecedented scale.

The dream of seven successive popes, from Sixtus to Clement, was over. Papal Rome would never recover that sublime, or blind, self-confidence.

I should also explain that Florence took advantage of the pope’s defeat to expel the Medici family once more. But the newly revived republic was besieged by the imperial forces for three years, from 1527 to 1530, during which time Michelangelo was in charge of the fortifications. (The detail from Vasari’s fresco shows the the encampment of the besiegers on the hills to the south of the Arno.)

Anyway, when the city capitulated, the Medici were to return for ever—from now on, as grand dukes of Tuscany. The dream of the ideal human society as a free republic had died almost everywhere (save for Venice), just like the dream of the popes.

Enough by way of historical context. Now let us move towards the fresco in the Chapel.

At this point, I should explain that when a new film arrived in Italy in the last century, it used to be shown in what was called ‘first vision’ (prima visione ) in the expensive cinemas in the centre of town. It then disappeared for a while and would subsequently be projected in seconda visione in the less fashionable cinemas in the suburbs.

This is the unlikely model I am going to adapt in this lecture—which will be much simpler than its predecessors in the series, because there is no story to summarise, and no theological or cultural message to decode. I shall show you the whole fresco rather rapidly once; then I will discuss some of its features in considerable detail; and finally, I will give you the opportunity to enjoy Michelangelo’s fresco in seconda visione , at a very leisurely pace.

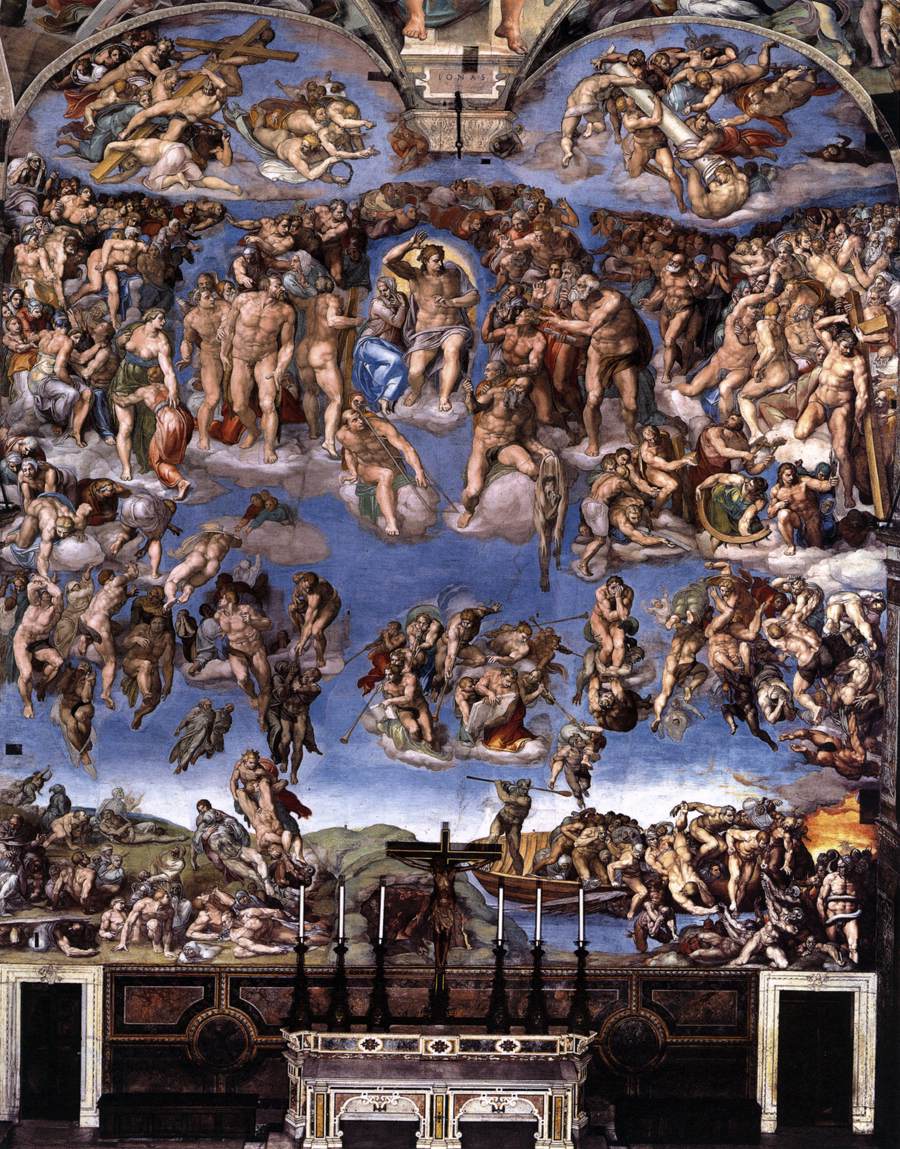

The purpose of the ‘first vision’ is to allow the Last Judgement to make its first overwhelming impact in the way you should experience it in the Chapel. I shall point out the main figures and zones (in an area measuring about forty five feet by forty), and confine myself to words taken from the two earliest descriptions of the wall.

Both these descriptions have a special status, because they were written by men who knew Michelangelo personally and admired him above all other artists. Each of them, too, wrote a biography of their hero: their names are Ascanio Condivi and Giorgio Vasari.

Two of the angels have a book in their hands—the Book of Life, and the Book of Death.

Above, we see the Son of God in majesty in the form of a man, with arm and strong right hand uplifted. Wrathfully he curses the wicked and drives them before his face into eternal fire, while with his left hand stretched out to those on the right, he seems to draw the good gently to himself.

Switching to Giorgio Vasari:

Our Lady draws her mantle around her in great fear, as she hears and sees such desolation.

So much, then, for the prima visione in which your eyes have been guided by the perceptions of Michelangelo’s earliest biographers, both of whom were writing within ten to twenty years of the unveiling.

Before we leave the 1550s, I would like you to look at an early copy of the whole fresco made by one of Michelangelo’s pupils, called Marcello Venusti.

The copy serves to establish some important points.

First, Venusti’s colours are vibrant, fresh and sharp. This is how they were when Vasari and Condivi saw the frescos—and how they became again, after the cleaning in the 1990s which removed centuries of candle-smoke from the surface.

Second, the separation or isolation of the various groups from each other seems to have been more pronounced than it is when we see them now; and the ‘clouds of glory’ were much more prominent.

If we now close in on Venusti’s copy, we may revise all the figures that were named in the prima visione, and register how the various groups relate to each other through their relationship to the gigantic figure of Christ in the top centre.

With a little bit of good will, the complex counter-pull of Christ’s arms—respectively, lifting and thrusting, but across the body—can be interpreted as setting up a circular movement, like water running out of a bath.

Around Christ, there is a fairly tight circle of the blessed, emerging more and more clearly from a dense mass in the distance behind, and climaxing in some large standing figures, who are almost equal in size to Christ.

The circle is closed by the seated figures of St Lawrence and St Bartholomew, whose Feast Days were of special importance in the Chapel.

This inner circle is relatively still, and most of the faces are turned intently inwards, looking towards the Judge.

Around them, there is a vast, second circle, where most of the figures are in movement—with a very clear sense of direction.

On the left, they are rising into Heaven; and our eye should climb through a very compact group (mostly female), who are diminishing in size as they recede, right up to the angels, high in the lunettes, bearing the Cross and the Column of Flagellation. From these angels, our gaze should now travel downwards on the right, descending through another very compact group, who are advancing and getting larger, to the area where we find a ‘wall’ of clearly identified martyrs, and below them, the angels, who drive the condemned down to the abyss—the second circle being completed by the trumpeting angels, with whom we began.

However, the power of Christ to attract or repel is still being felt at ground level by the bodies rising from their graves, or by the Damned who are being sent down to Minos and the flames of Hell on the right.

Whether or not you find it helpful to identify the two circles, there is no mistaking the ascent on the left, and the fall on the right.

I remind you briefly of the original fresco, rather than the copy, before calling attention to other important features of its general design.

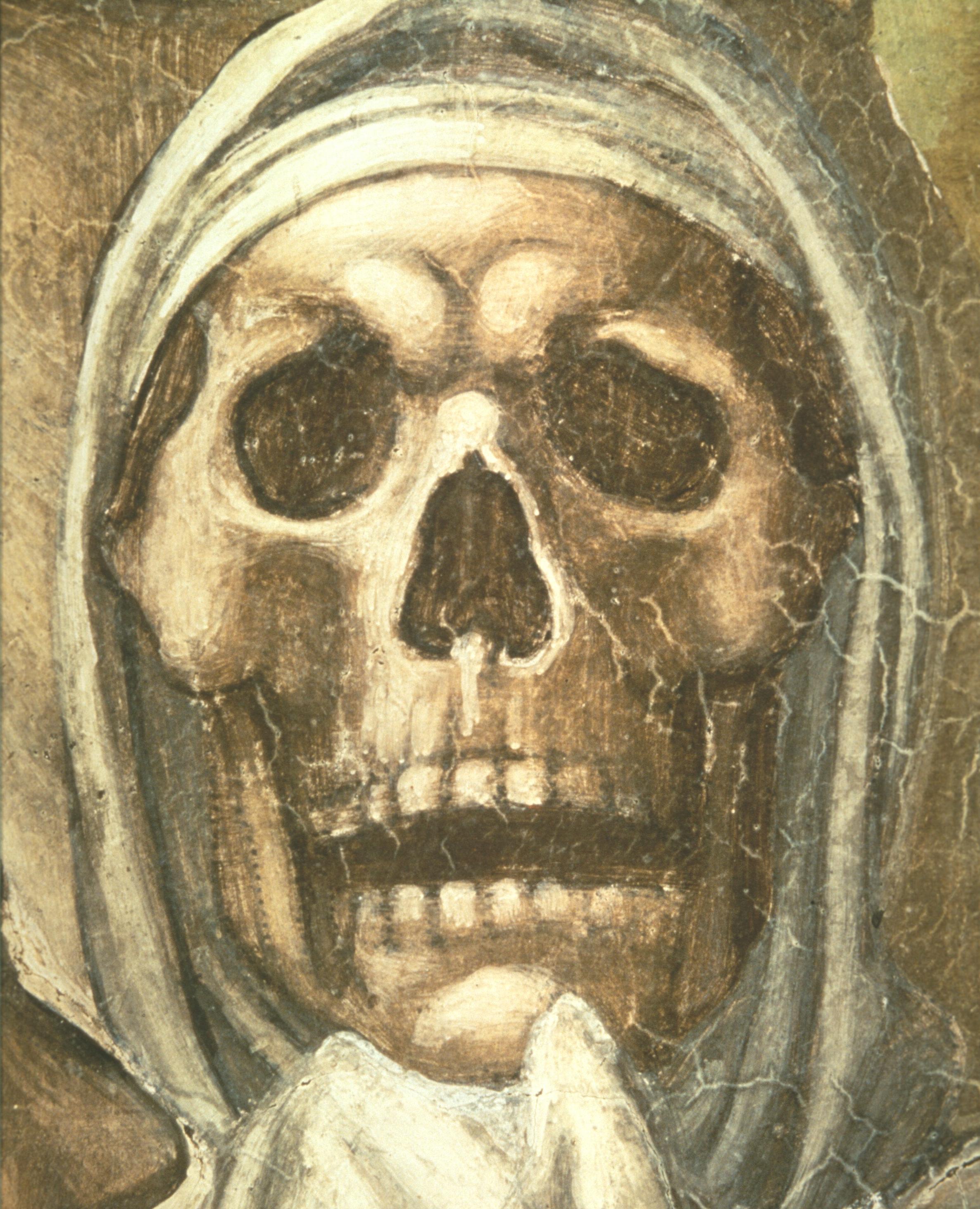

And the best way to proceed—perhaps the only way—will be to show you two other Last Judgements, both Italian, from about two hundred years earlier.

The comparisons will both highlight Michelangelo’s greatest single innovation, and remind you of how faithful he was to the iconographical tradition.

First, then—best preserved, and best known to us, although probably unknown to Michelangelo—let us consider the entry wall of the Arena Chapel in Padua, painted by Giotto just after 1300.

It reminds us that whereas Christ had usually been represented, in a scene of the Last Judgement, as seated like a Judge, clothed, and circled by a stylised ‘glory’, Michelangelo chose to represent him as essentially nude, and standing or rising, or, rather (in the words of the prophecy in Matthew’s Gospel), as ‘the Son of Man, coming in the clouds of Heaven, with power and great glory’.

What Michelangelo emphasises are the ‘clouds’, the ‘coming’, and the ‘power’.

Nevertheless, there are many shared features.

In both frescos, Christ is out of scale to all the other figures, and picked out by a splash of yellow.

And in each case, there are four clear horizontal ‘bands’ or ‘tiers’—respectively, of angels; of apostles and saints (the six large figures to either side); of figures approaching and figures being hurled away; and of figures emerging from the grave (together with a suggestion of the torments of Hell).

In Padua, the Cross is prominently displayed; and, as we close in on Giotto’s Christ, you can see that his feet and hands display the stigmata (nail-marks of his Crucifixion).

Notice that Christ’s hand movements are contrasted: right palm up, and left palm down, welcoming the Saved and spurning the Damned.

It is significant, too, that his mild gaze is turned towards the Blessed.

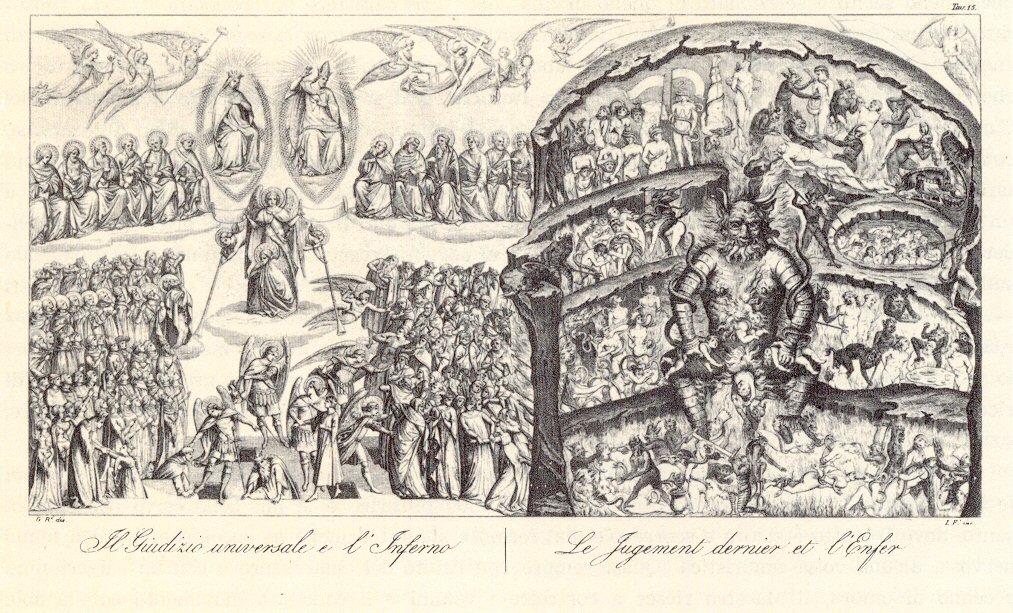

In the Camposanto at Pisa, there is a large fresco from the mid-fourteenth century, which was almost certainly known to Michelangelo.

In this nineteenth-century engraving of how it used to be, you will be immediately aware of the decisive horizontal ‘banding’ on both sides of the composition (there are four ‘tiers’ both in Heaven and in Hell).

But you must not miss three other features which Michelangelo took over from tradition: the angelic trumpeters in the centre; the angelic prison-guards, who are driving back the damned; and, most important of all, the figure of the Virgin Mary, seated with lowered gaze beside her Son, whose right arm is now lifted in condemnation, while his left arm points to the wounds in his side.

To recognise debts like these is not in any way to deny Michelangelo’s originality; and one could easily spend a lot of time examining other Last Judgements in order to ‘render unto Michelangelo that which is Michelangelo’s’.

However, I think we will be more confident that we are tuned in to the right wavelength if we now trace out the stages in the evolution of Michelangelo’s design.

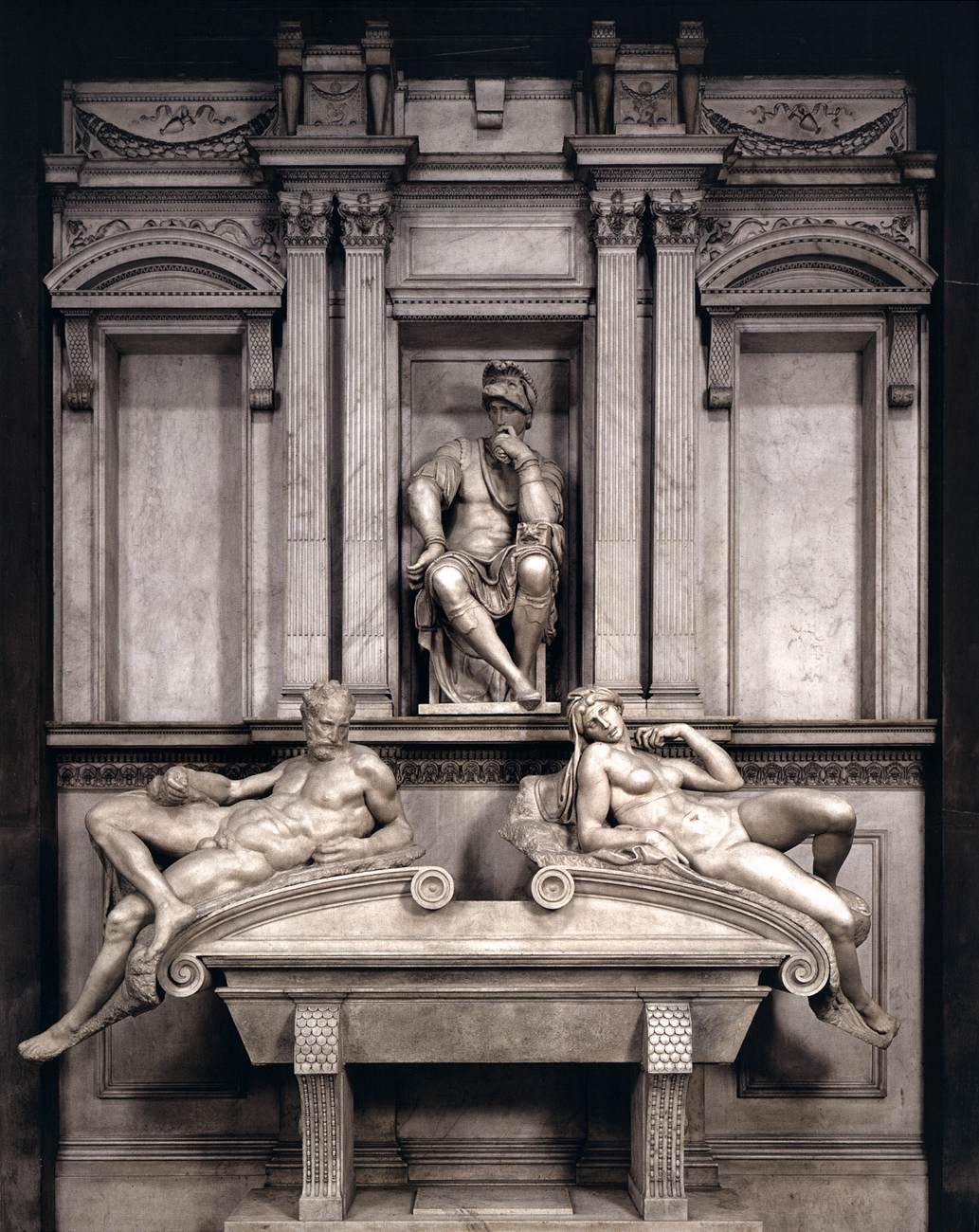

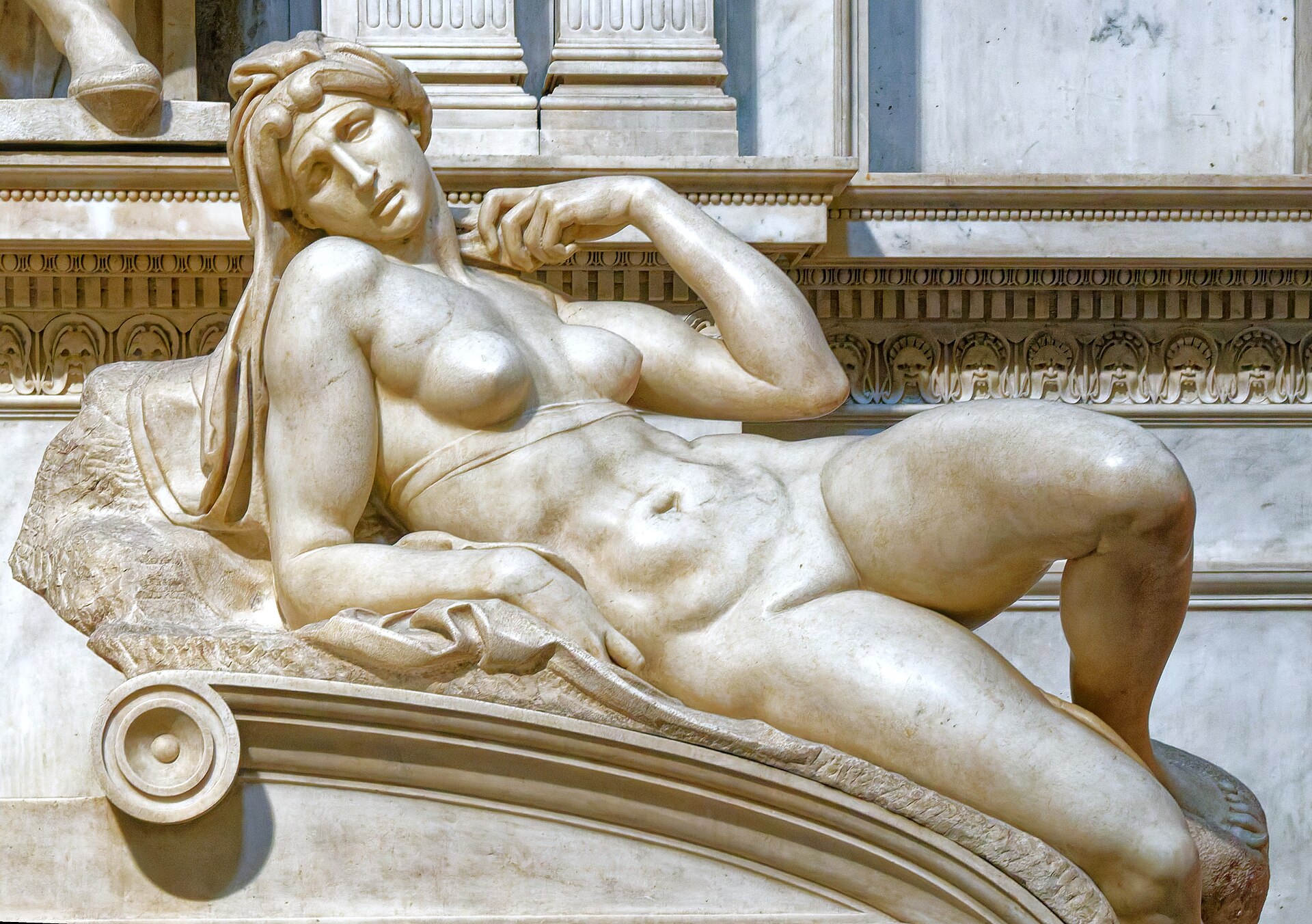

In the mid-1520s, Michelangelo had been at work on sculptures for a funerary monument for two members of the Medici family.

I remind you here of the tomb for the younger Lorenzo, duke of Urbino, with its famous statues of Twilight and Dawn balanced on the sarcophagus.

(There could hardly be a better single example of Michelangelo’s new figure style in the decade after he completed the second phase of his work on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel than the figure of Dawn in the detail here.)

The fact that Michelangelo had been actively involved in the defence of the Florentine Republic from 1527 to 1530 was to make his relationship with the Medici pope (it was still Clement VII) rather ‘difficult’, to say the least; but by 1532 both men were back in Rome, and they had reached a modus vivendi.

The Sistine Chapel, meanwhile, had suffered damage to the two end walls. The simulated altarpiece had been blackened by a fire, and the first frescos in the narrative cycles of Jesus and Moses on the entry wall had been cracked by the collapse of the lintel over the door.

Sometime early in 1534, Clement seems to have decided to repair and restore both the end walls, with the intention of moving a representation of Christ’s Resurrection and Ascension to the western end of the chapel, where it would replace the Assumption of the Virgin over the altar.

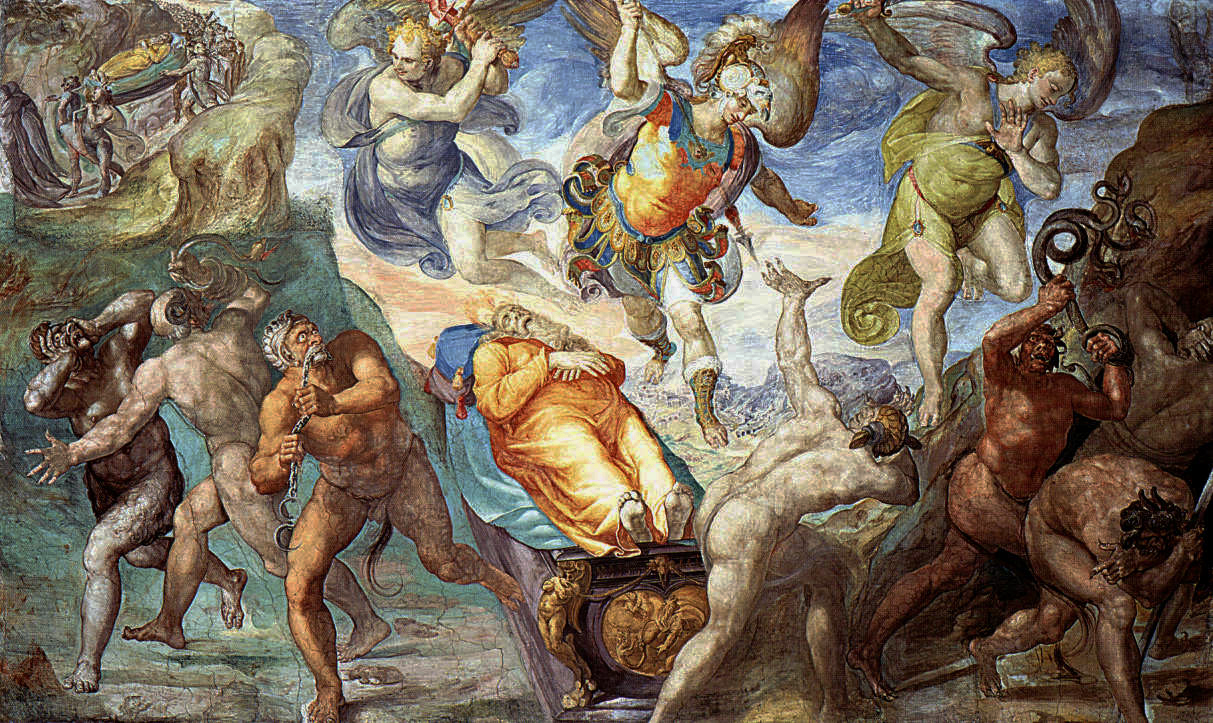

This was in order to dedicate the whole width of the entry wall to a representation of ‘The Fall of the Rebel Angels’, which would have been closely linked to the subject of the other existing fresco, which showed a struggle between devils and the Archangel Michael for the body of Moses. (Clement’s plan was never executed and the two mannerist frescos you see here are repaintings of the original subjects, which are later in date than the Last Judgement.)

Not surprisingly, Clement insisted that Michelangelo, by now fifty-nine years old, should undertake both the new frescos. And it is important to note that the subject matter of Christ’s Ascension and the Fall of the Rebel Angels would both have been highly congenial to Michelangelo, even though he would have preferred to continue work on his sculptures for the tombs of the Medici Dukes in Florence and for the still incomplete funerary monument for Pope Julius II in Rome. (The tomb, which I discussed in an earlier lecture, was now conceived on a more modest scale, and was to be placed in a church, rather than in the Basilica of St Peter’s.)

His drawings of this period reveal that he was mildly obsessed with classical myths of human rebellion or presumption and divine retribution—especially the myth of Apollo’s love child, Phaethon, who tried to drive his father’s chariot, and had to be destroyed by a thunderbolt from Jupiter.

The upper drawing here is one of four on this theme; and I would like you to notice the position of Jupiter’s arms, the representation of a free fall in space, and the terror and despair of Phaethon’s sisters on the ground, which should remind you of the centre and right of the Last Judgement.

Similarly, there exist sketches of the Resurrection of Christ (the proposed theme for the Altar Wall) going back a good twenty years, and also new drawings for the new commission in which Michelangelo is concerned above all with rendering ‘ascent’—that is, free movement, upwards, in space—because he characteristically combines in one image the moment of Resurrection, on Easter Day, and the moment of Ascension, at Whitsun.

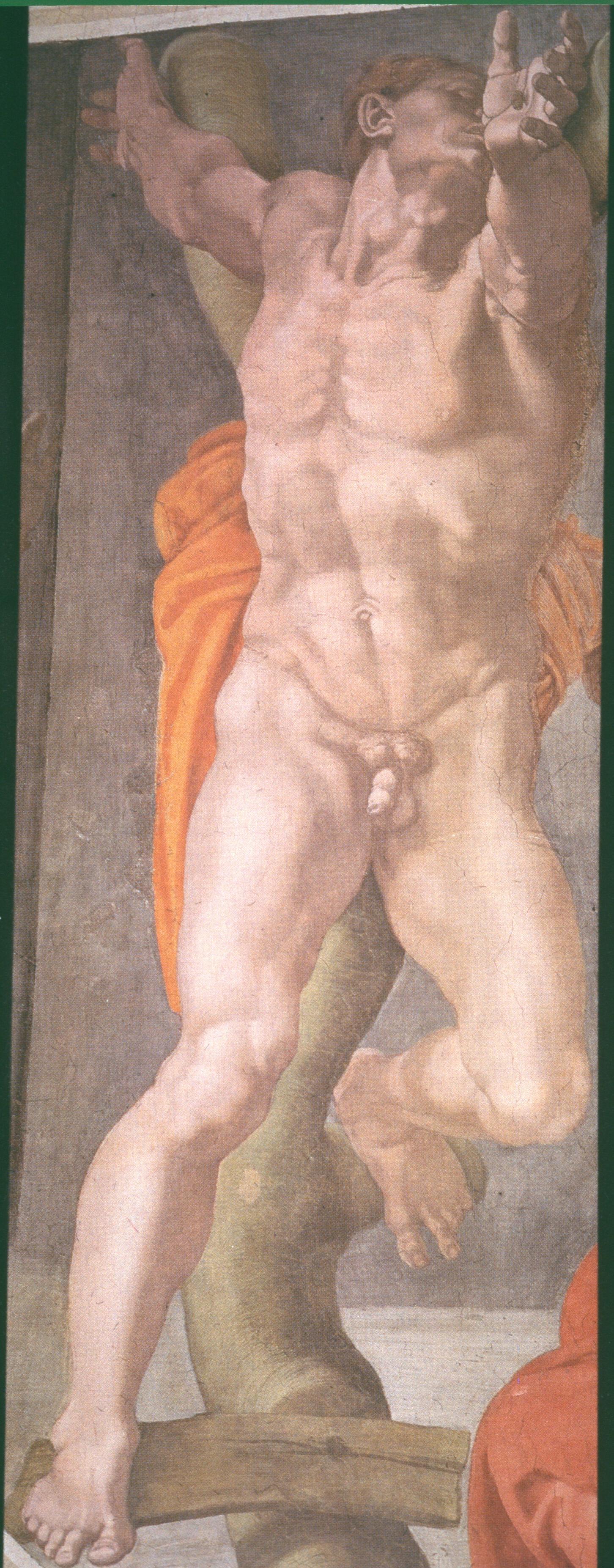

In drawing you see here, Jesus is given the proportions of an Apollo; the body is given its characteristic ‘serpentine’ twist; and you would have registered the relevance of his raised arm, even if I had not flipped the photograph horizontally in order to make it his right arm, as in the final fresco.

Another marvellous sketch for the Resurrection shows, in addition to the nude figure of Christ, the soldiers who had been guarding his tomb. Instead of being fast asleep, however, as would have been traditional, they are scattering like spokes from the hub of a wheel, or like rays from the sun (or perhaps a sun god).

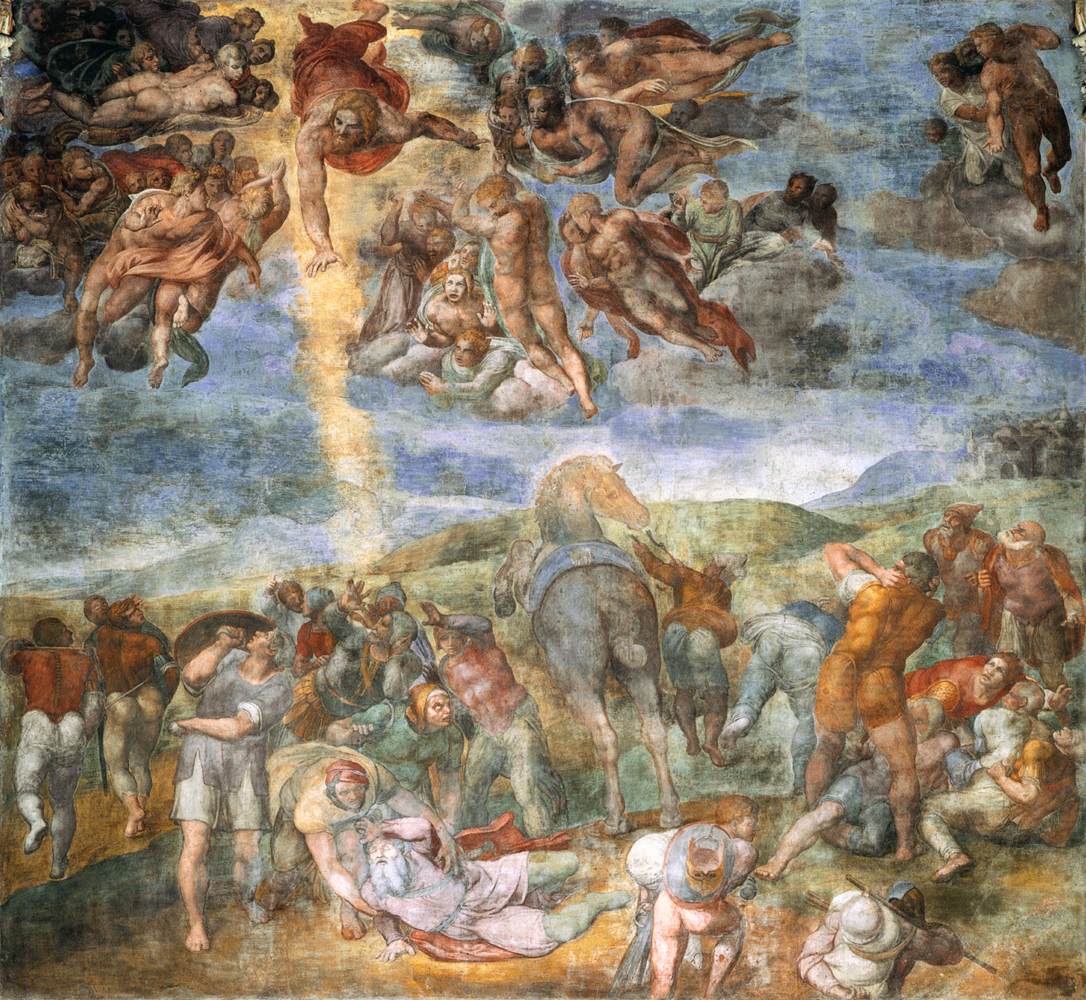

This theme of an eradiation of divine energy from a centre—eradiation that creates a sphere of influence or determines the movements of all bodies in a surrounding circle—was clearly very important to Michelangelo. So much so that it will return twice in the fresco (in the lower image) which he executed four years after the Last Judgement, dealing with the conversion of Saul on the road to Damascus.

Angels radiate from the flying figure of God who hurls his flash of lightning, while, on the ground, soldiers, bystanders and a horse form another exploding wheel—with Paul himself, blinded on the ground, acting as the main spoke.

Thus, even before we come on to the actual commission for a Last Judgement, or to the drawings which show its evolution, we begin to see why the huge fresco will show Ascent and Fall, and why Christ as is shown as Apollo-the-sun-god, or as Jupiter hurling a thunderbolt, and why there should be an explosive centre, a ‘sunburst’ from the sol iustitiae, affecting the movement of every other body in a sphere of influence, drawing or repelling.

Both the Last Judgement and the Conversion of Saul were commissioned, not by Clement, who died in that same year 1534, but by his successor, who took the name of Paul III—a man who had fathered four children as a young cardinal, but who in 1545 would summon the Council of Trent and set in motion the Counter-Reformation.

It was he who, in early 1535, brushed aside all Michelangelo’s protests, and demanded that he should paint a Last Judgement on the Altar Wall.

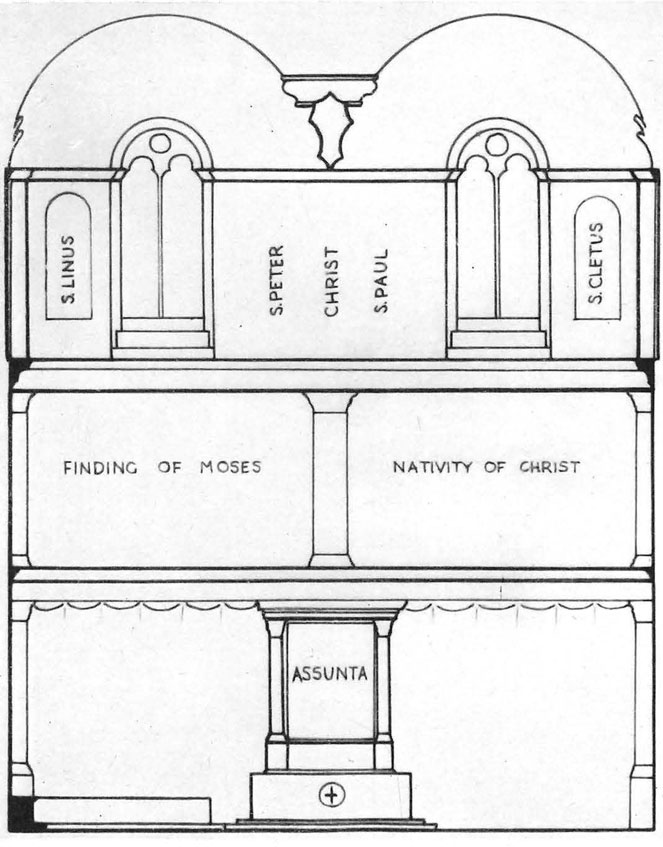

We have to bear in mind that, in that year, the wall was still laid out as shown in this very clear diagram.

In the lunettes above the windows, at the very top, were some of Michelangelo’s own Ancestors of Christ.

Flanking the two windows lay simulated niches with simulated statues of the first thirty popes, painted by the four teams in the 1480s who contributed the frescos of the narrative cycles devoted to Moses and Jesus, which lay below the windows.

In the lowest tier, the fifteenth-century altarpiece—still in fresco—showed the Bodily Assumption of the Virgin (Assunta).

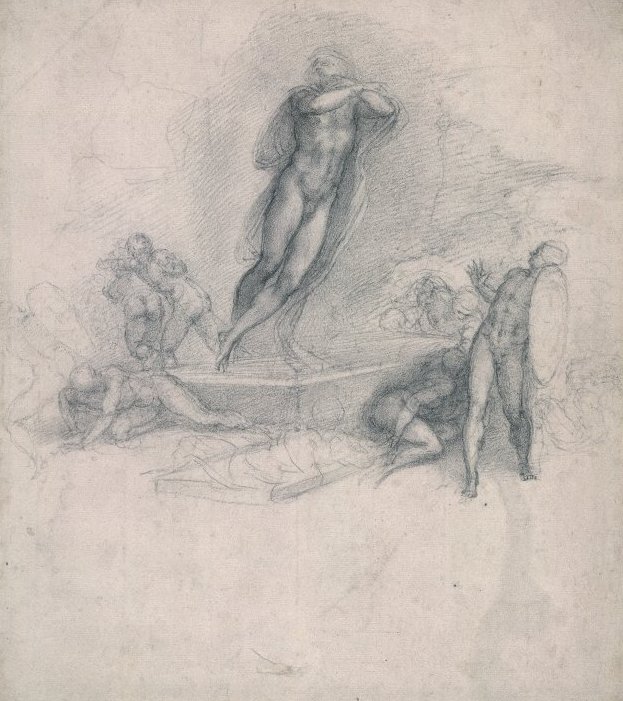

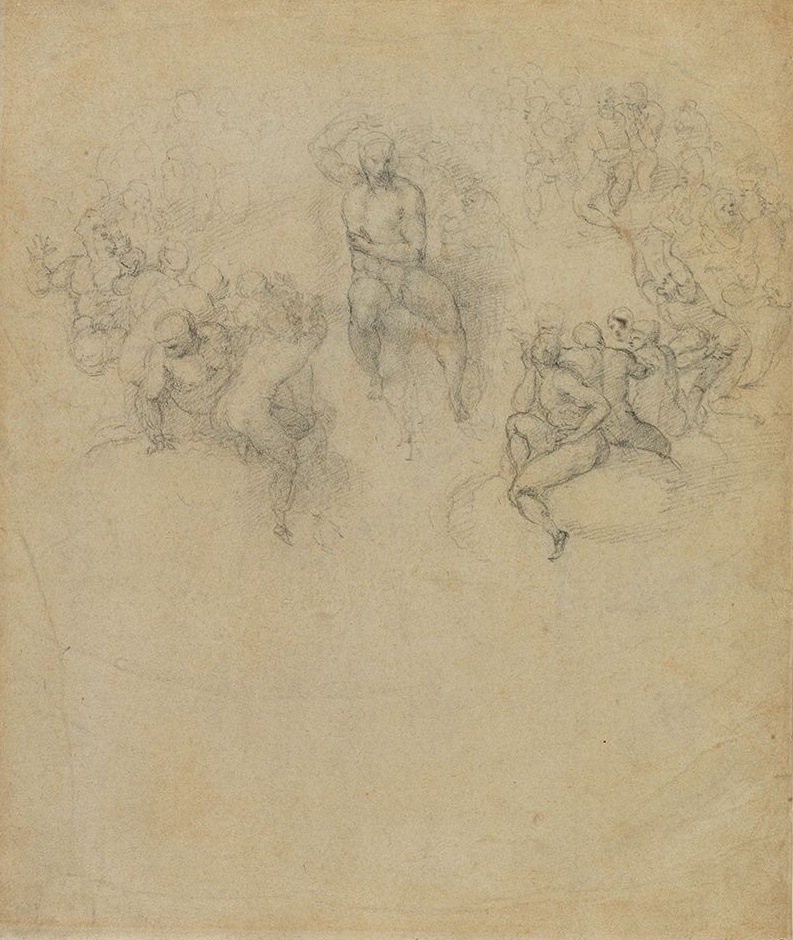

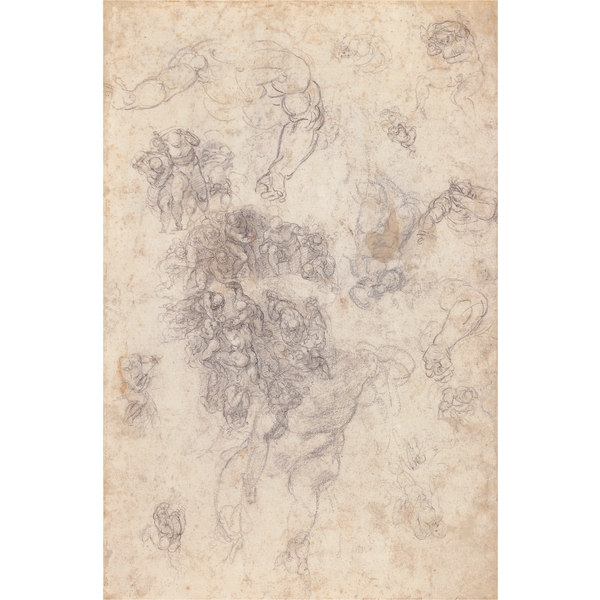

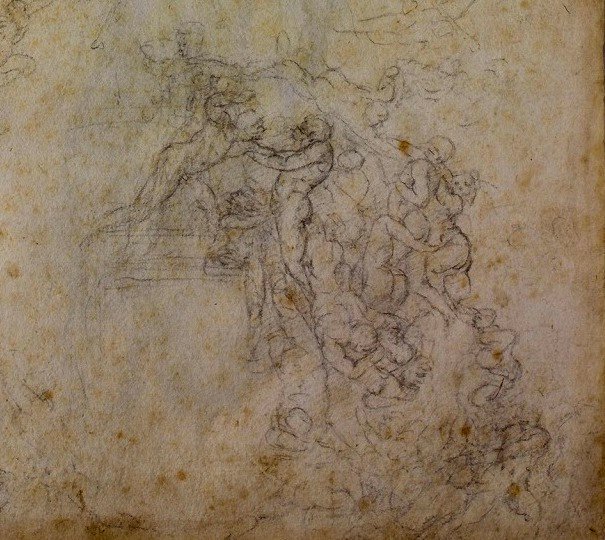

The earliest surviving sketch for the Last Judgement would seem to be the one you see here, in which there are three main things to notice.

First, from the beginning, Christ is nude and has his right arm raised.

Second, the Blessed form part of a ‘tilted wheel’, with strong torsions in their bodies, expressive of fear or entreaty.

And third, the design would seem to be limited to the two middle registers.

In other words, it would seem that, in the original brief, the windows were to be bricked up and the pair of narratives destroyed, but the lunettes and the altarpiece would have survived.

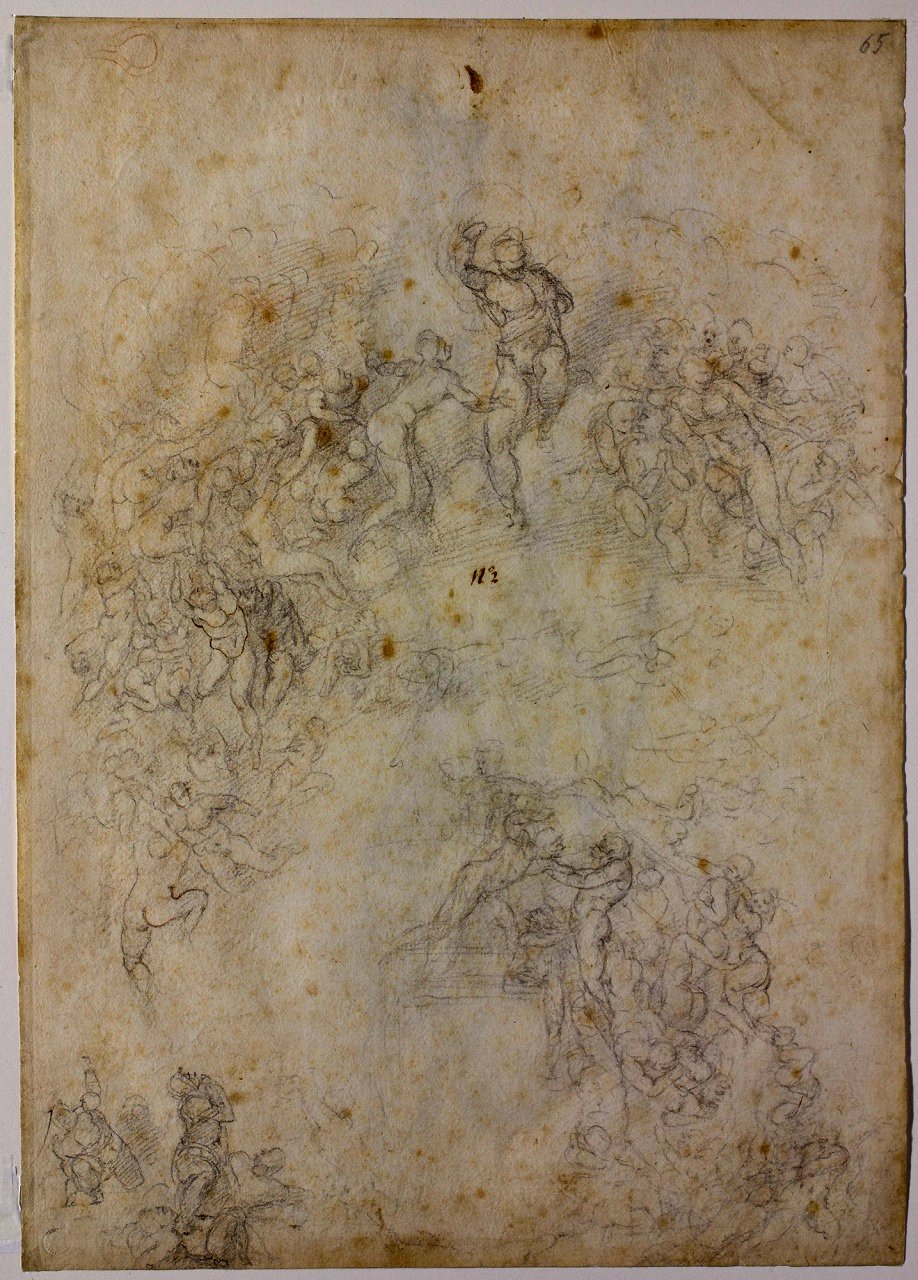

The second drawing (it is disputed whether it is earlier or later) shows Michelangelo’s early thoughts about the lower half of the wall.

If you look carefully at the detail, you will see that he seems to trying to fit his composition around the altarpiece.

He also seems to have imagined a very vigorous resistance on the part of the Damned—inspired no doubt by classical myths of the assault on Mount Olympus by the giants.

We have very little evidence about the intervening stages, when Michelangelo must have decided to extend his picture up into the lunettes (destroying his own Ancestors of Christ) to show the angels, and then down (sweeping away the frescoed altarpiece), in order to introduce Charon’s boat, Minos, and the Resurrection of the Dead.

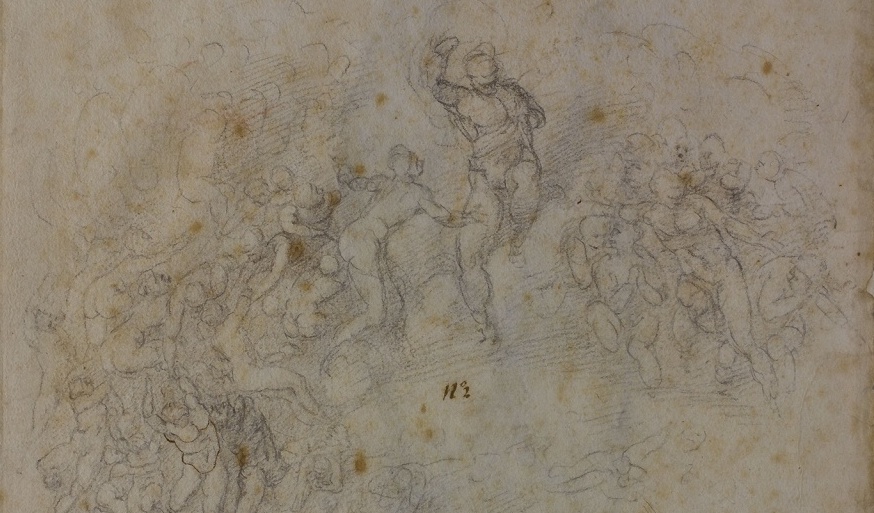

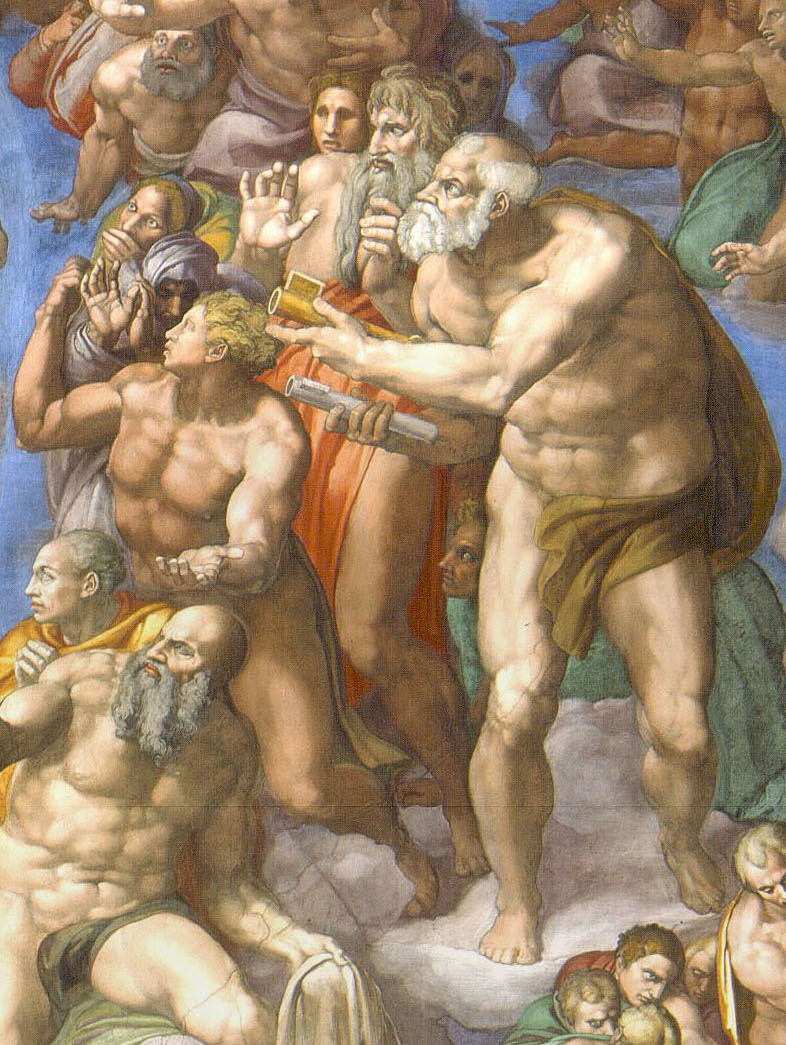

What evidence we do have, though, is of the highest quality, such as the vibrant centre of this sheet of drawings, where Michelangelo is coming close to his final solution in the area where the martyrs form a wall and where the angels struggle with the damned: you can see the penitent thief, St Sebastian, kneeling with his arrows, the angel with a raised arm and the back of his powerful opponent, more or less as they would remain.

The point to remember is that the final design did not come to him in a single flash of inspiration, but via a series of lightning sketches like the ones you have just seen.

The previous detail came from a sheet of drawings that document the beginning of the next phase—by far the longest—in the evolution of the Last Judgement; a phase which lasted not merely for weeks but for a period of years.

Even though Michelangelo is still ‘doodling’ on a very small scale, he is beginning to experiment on the same piece of paper with detailed poses on a larger scale—an arm, two arms and a torso.

(The shadowy image at the bottom looks like the figure who would become St Lawrence.)

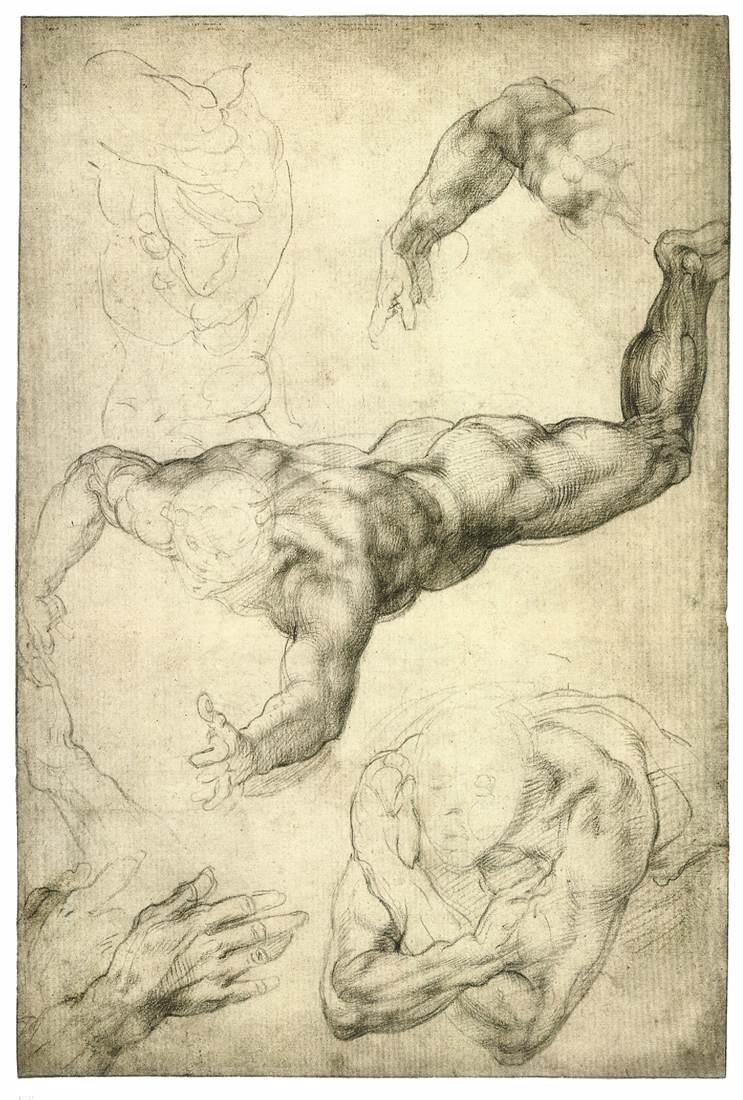

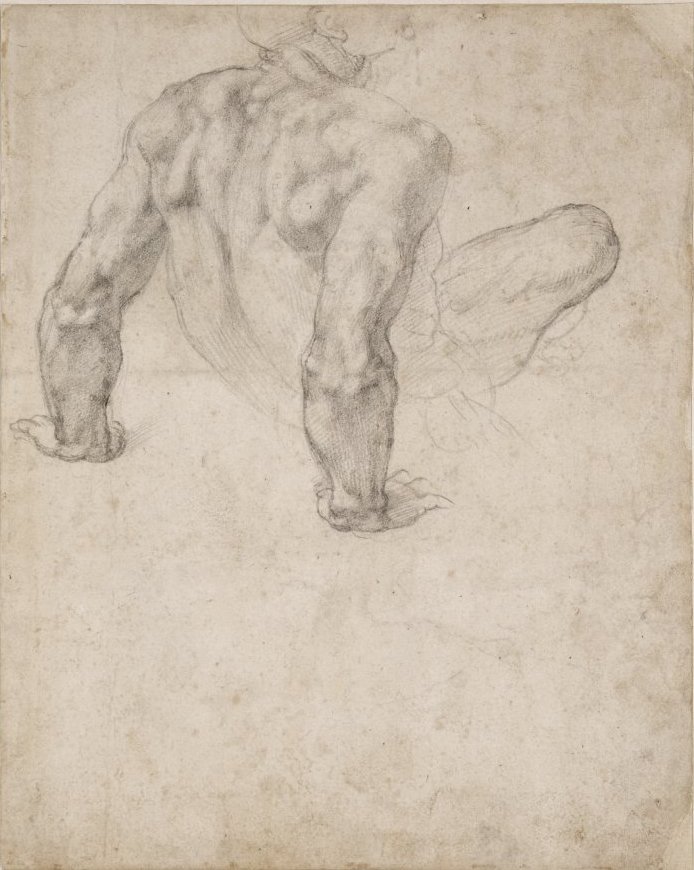

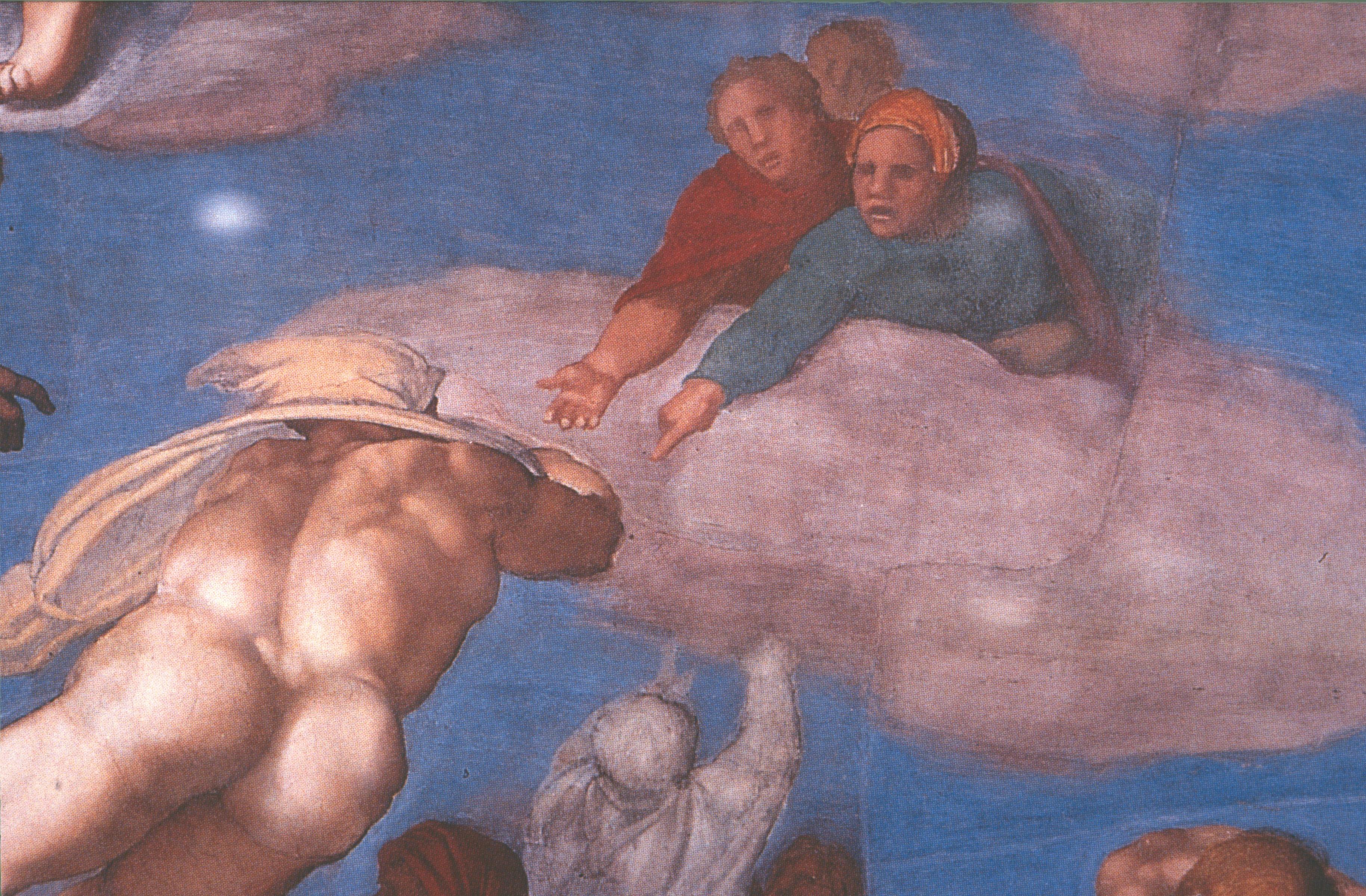

In this phase, it was clearly his normal studio practice to draw from the life a well-muscled assistant, who would be instructed to adopt a particular pose.

In this case, his model might have been asked to kneel on a bench or table and reach down, so that the artist could visualise one of the Blessed in the clouds who was helping a new arrival to safety. In due course the arms and back in this very rapid sketch (a matter of seconds) would appear in the fresco, freely modified and drawn from a slightly different angle.

Or again—the assistant would be asked to sit on the floor and brace the weight of his powerful body against his flattened hands behind him.

This highly finished drawing (one of Michelangelo’s finest) would be reproduced in the fresco, with fewer changes, as one of the Blessed at ground level, arising from the grave at the general Resurrection on the Last Day.

In all these studies, you will see how very little Michelangelo was interested in faces—it is the muscles of the back, legs and arms, tensed in various ways, and seen from incredibly difficult angles, which are his chosen vehicle of expression.

It is also clear from the many surviving sketches that Michelangelo did not always draw from the life, but continued to find inspiration in classical statues.

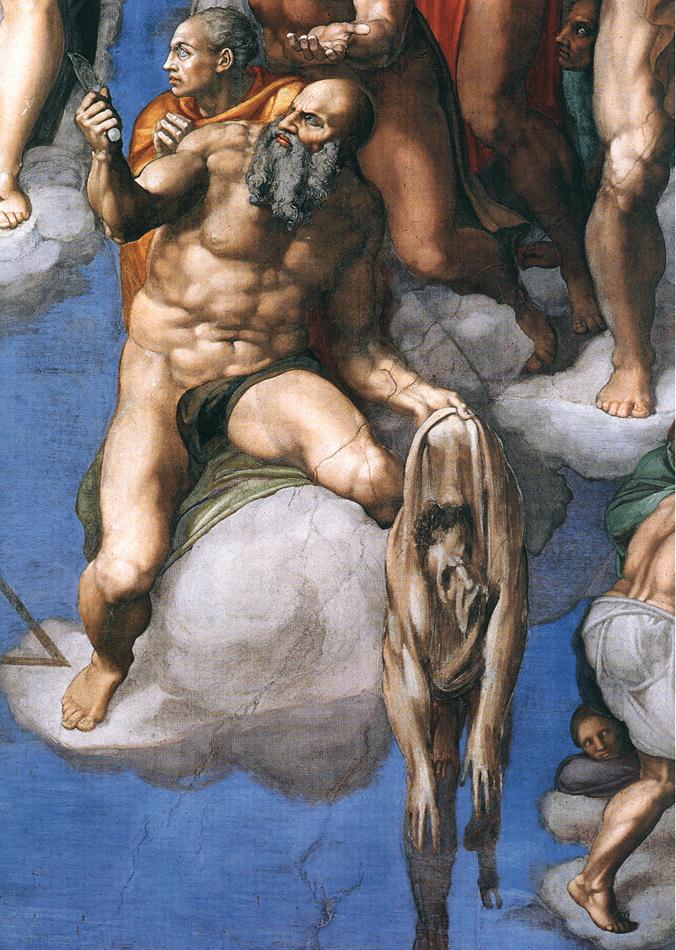

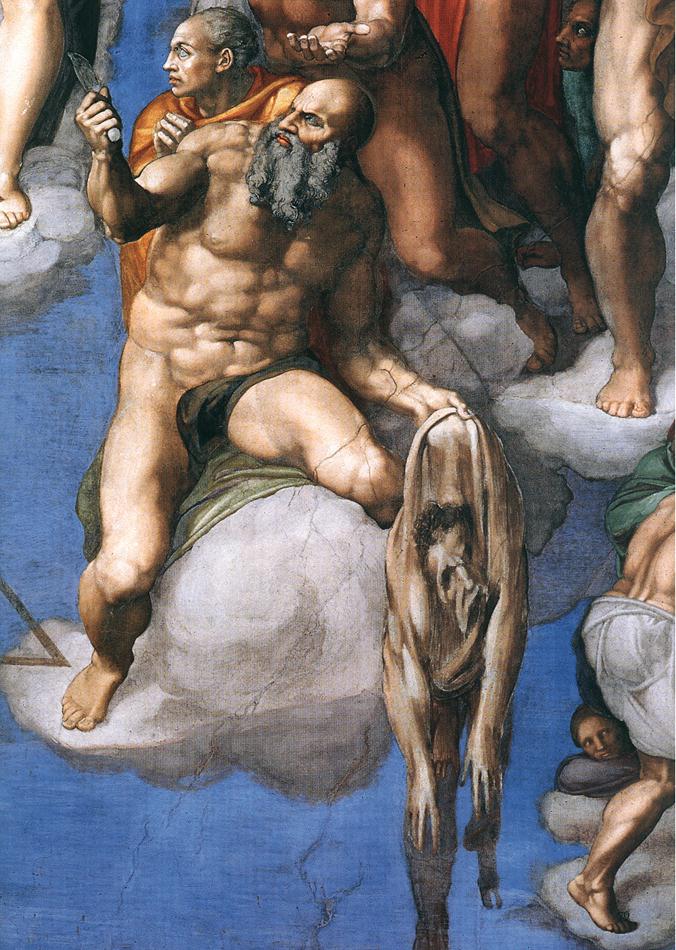

The famous Torso di Belvedere (which was discussed in an earlier lecture with reference to the male ignudi above the thrones of the prophets on the ceiling of the Chapel) is the model for the torso of St Bartholomew. (We will come back to his face and flayed skin later!).

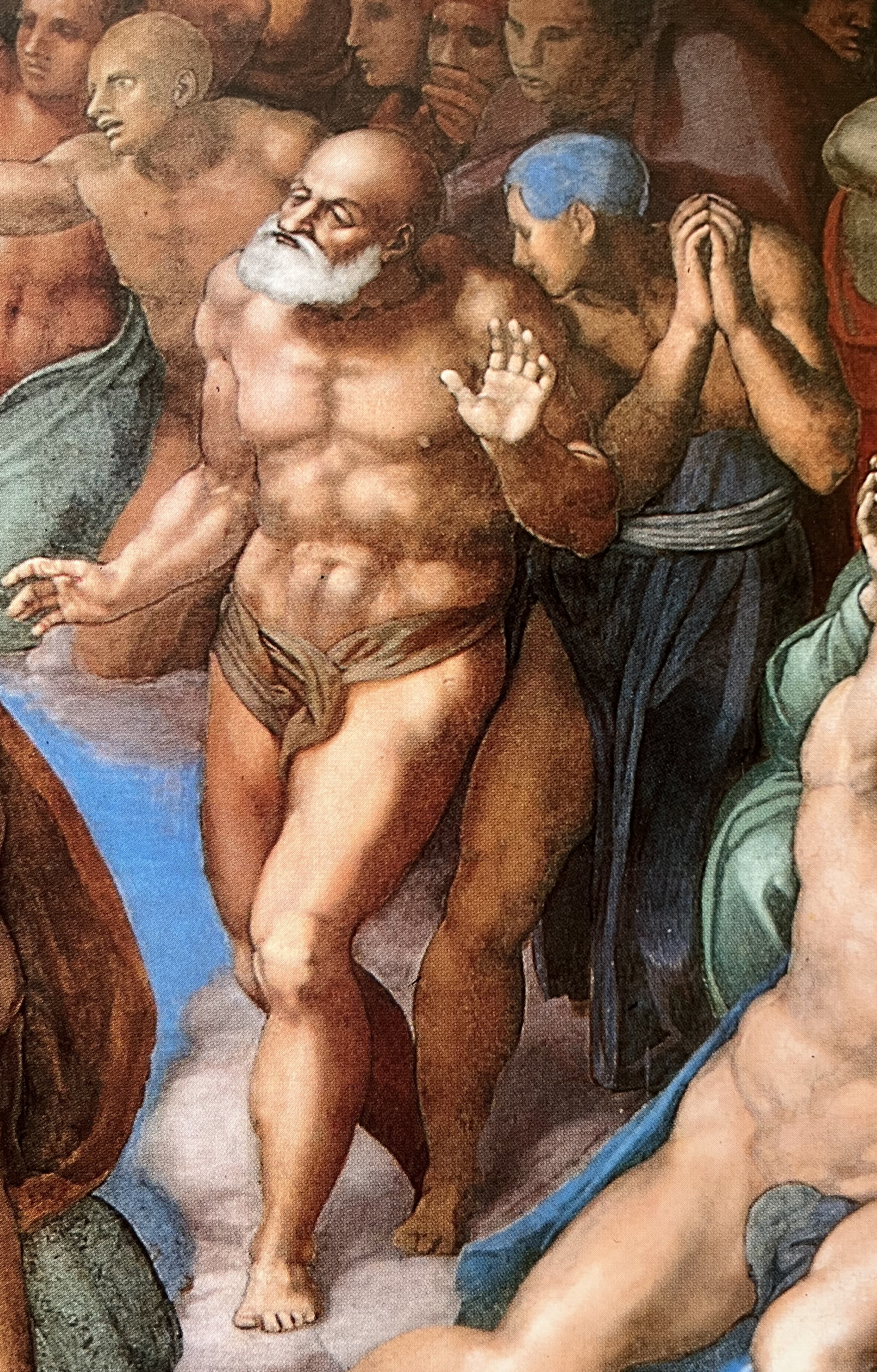

A statue of Niobe trying to protect one of her daughters from the avenging arrows of Apollo and Diana is freely transformed into the pair you can see here. (They appear alongside the massive male in the previous detail, the one whom Vasari identified as Adam, but is in fact meant to represent St John the Baptist.)

The back and arm of the kneeling woman are very similar to those of the Libyan Sibyl, and its preliminary drawing, from twenty years earlier.

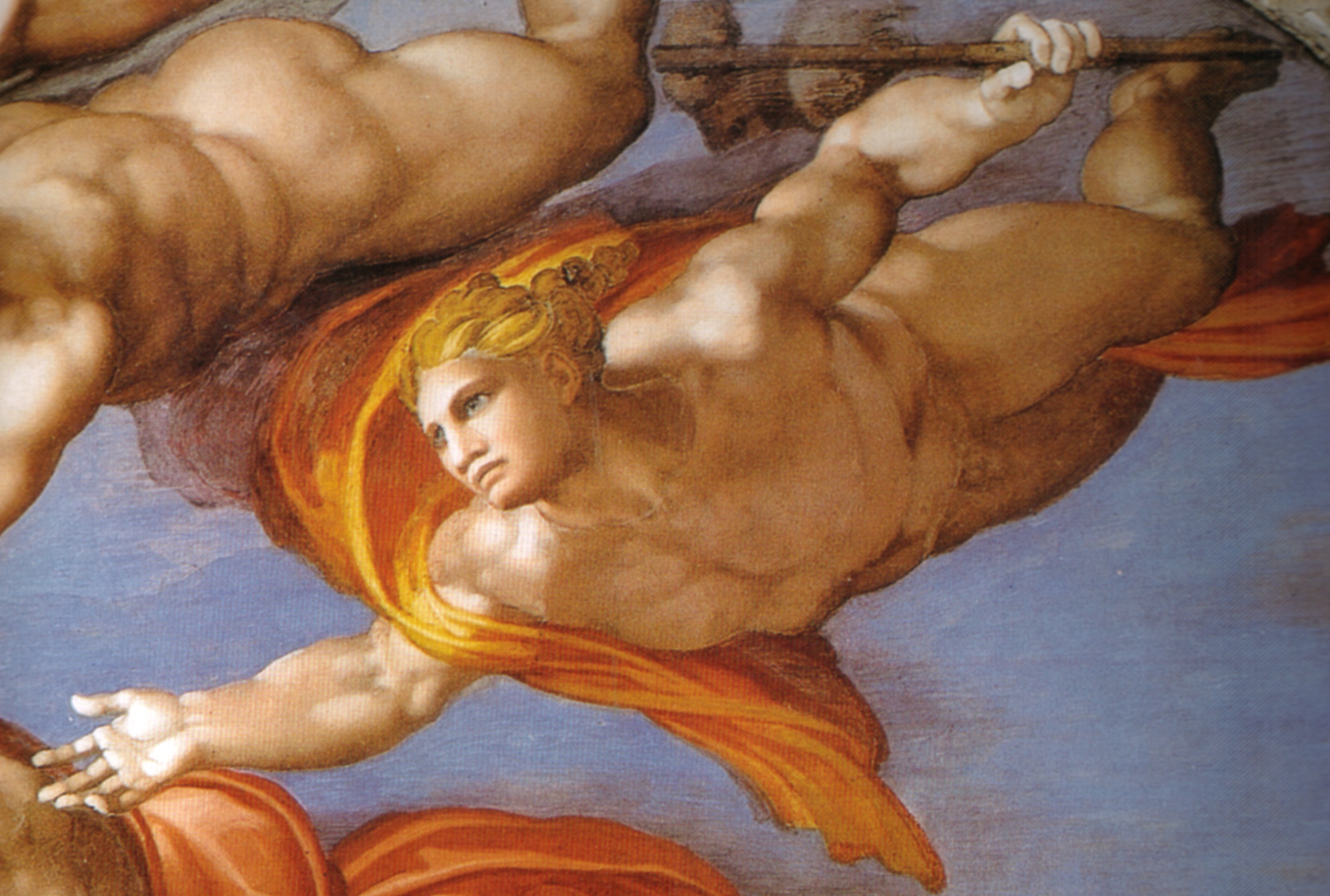

Now, it is an art-historical commonplace that Michelangelo’s style in the Last Judgement—which was actually painted between 1536 and 1541, that is, from the age of sixty-one to sixty-six—is radically different from the style of the frescos on the ceiling, executed more than twenty years earlier. Nowhere is this difference more striking than in his treatment of the nude.

Even his angels can become ‘endomorphs’, at times almost like American footballers in full protective clothing: rubbery or even blubbery, grotesquely overdeveloped, and sometimes as coarse in expression as the trumpeter in the lower detail here.

The radical change in style is not in dispute. Nor are the main biographical, historical and cultural causes of that change.

But the processes I have just been illustrating—the way in which Michelangelo adapted his new commission to his current obsessions; the sequence of lightning sketches of increasing boldness and originality, followed by drawings from the life; the borrowings from classical sculpture; the commitment to the male body, unclothed—these are all exactly the same in principle as they had been in the years from 1509 to 1512.

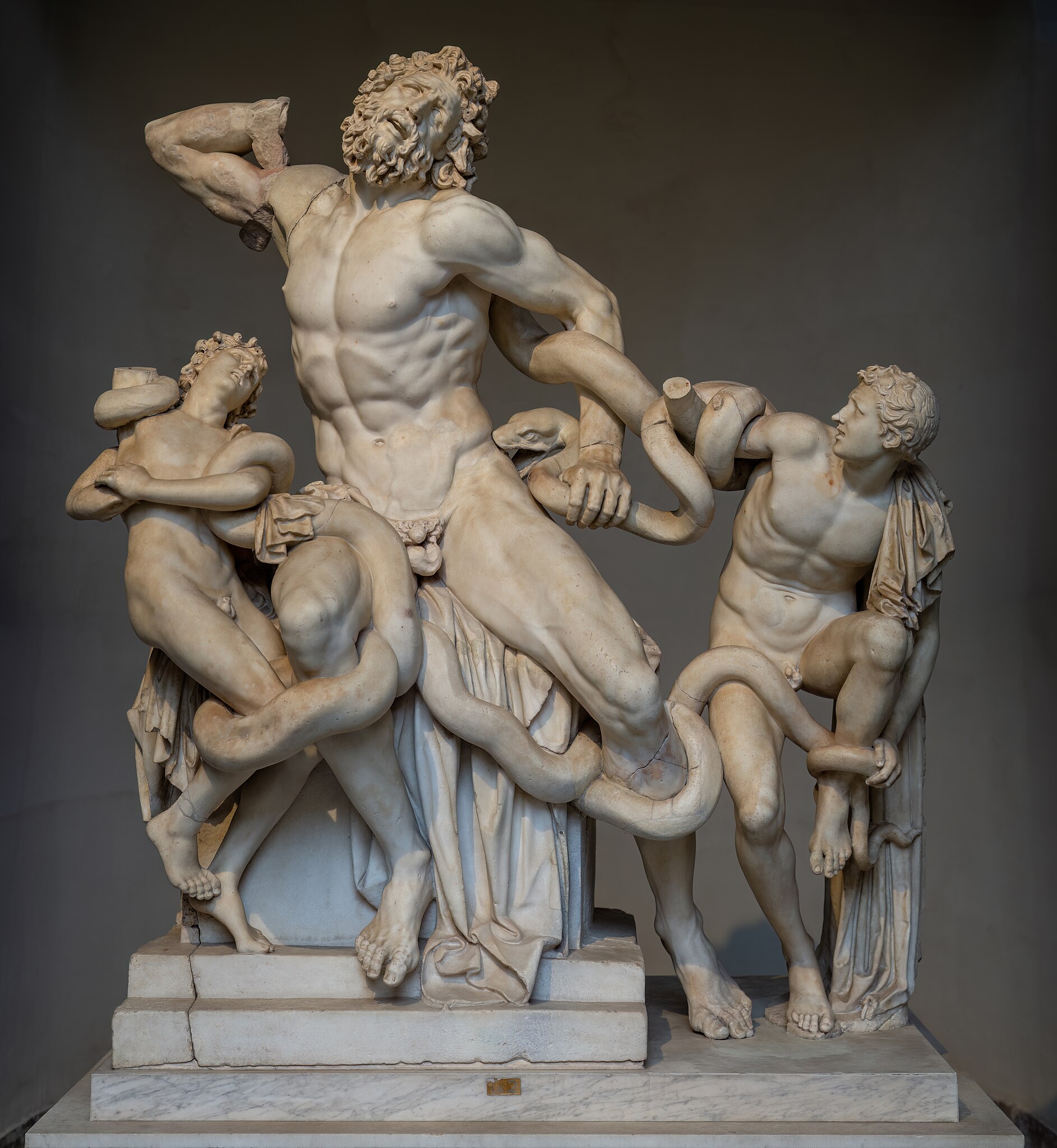

For example, the crucified figure of Haman (another variant on the Laocoön), dating from 1512, in the corner-spandrel next to the Altar Wall, is strikingly similar to a figure on the same side of the Last Judgement—in fact, even more like a cricket bowler in his delivery stride, about to unleash an out-swinger.

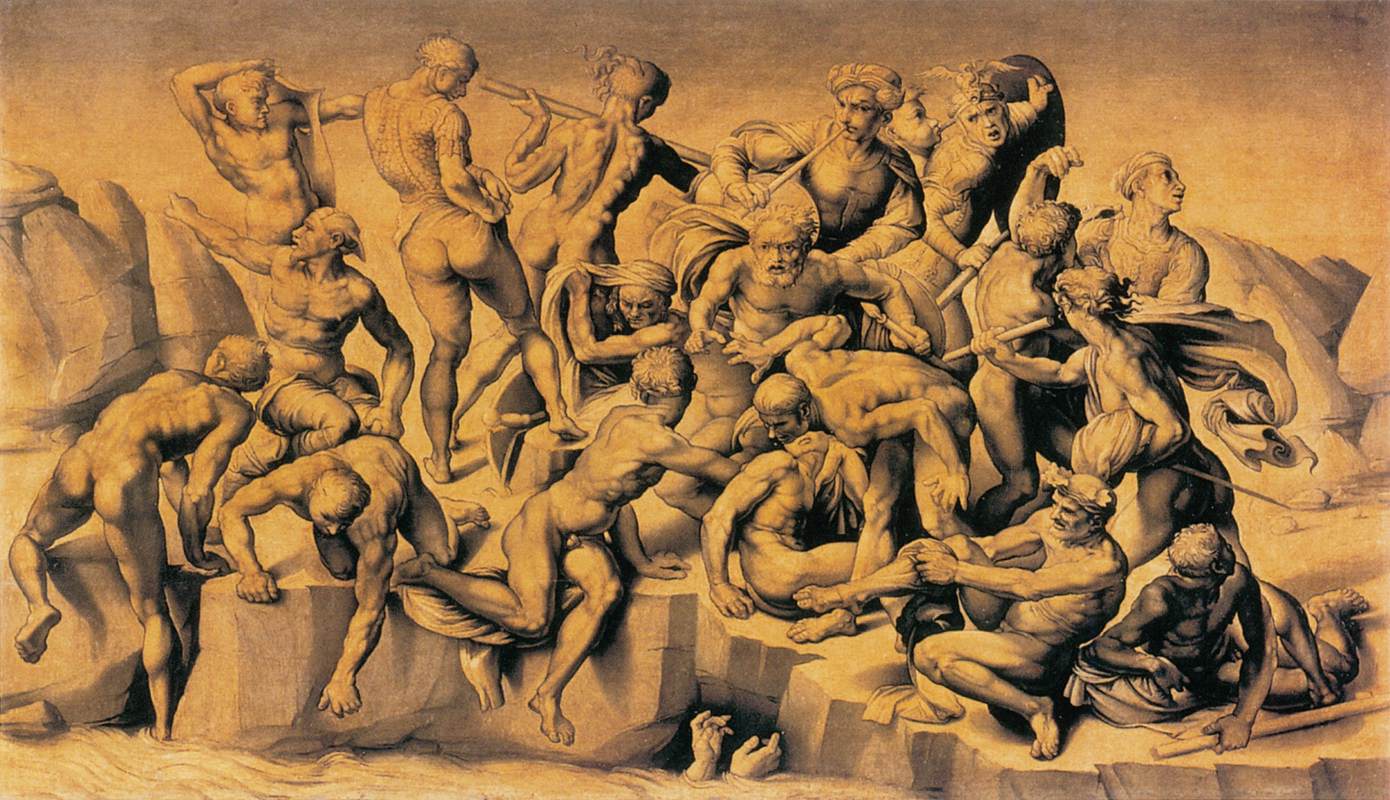

Or we can go back even earlier, as far as 1505, to the time when Michelangelo and Leonardo were preparing giant frescos of Battle Scenes for the Council Chamber of the Republic in Florence. Michelangelo’s Battle of Cascina has been lost, but we have a more than competent copy of its cartoon which gives us a fair idea of the composition.

The soldiers (who had been swimming in the river and sunbathing on the bank) have heard the alarm, and are rising, twisting and pulling on their armour.

All are presented in the same plane, like a relief sculpture; all are improbably closely packed—and all are very much the cousins of the Blessed on the right of the Last Judgement.

Or we can even go further back, as far as 1492, when Michelangelo was just eighteen, and compare the little marble relief with a detail from just below the ‘wall’ of the martyrs in the Last Judgement.

What do you see, nearly fifty years earlier? A ‘relief’ of a struggle, the good above and the bad (the centaurs) below, with the main expressive vehicle being human backs and muscular arms.

It will be this sense of continuity—reinforcing what we have learned from Michelangelo’s sketches, his studies from life, and his homages to classical sculpture—that will guide me in my selection of details and my commentary in what follows.

(I might have told you something about Michelangelo’s poetry, and what it reveals of his pessimism and sense of guilt. I might have presented the fresco as a religious epic—but I myself do not feel it as a profoundly ‘inward’ work. If I were to offer an anachronistic parallel to the giant fresco, it would be Leni Riefenstahl’s film of the 1936 Olympics: there is a tragic background, certainly; a tale of struggle, winning and losing, yes; but what matters most of all is the celebration of the human body, extended to its utmost.)

Make yourself comfortable, then, to enjoy an extended seconda visione of the whole pulsating wall.

Please use your own eyes to take in lots of detail (I will keep my comments as brief as possible), but retain some awareness of the route all the time as we glide over the surface clockwise in two spirals, working our way from the outer circle to the inner, so that we may end the journey in the dynamic centre of Michelangelo’s maze.

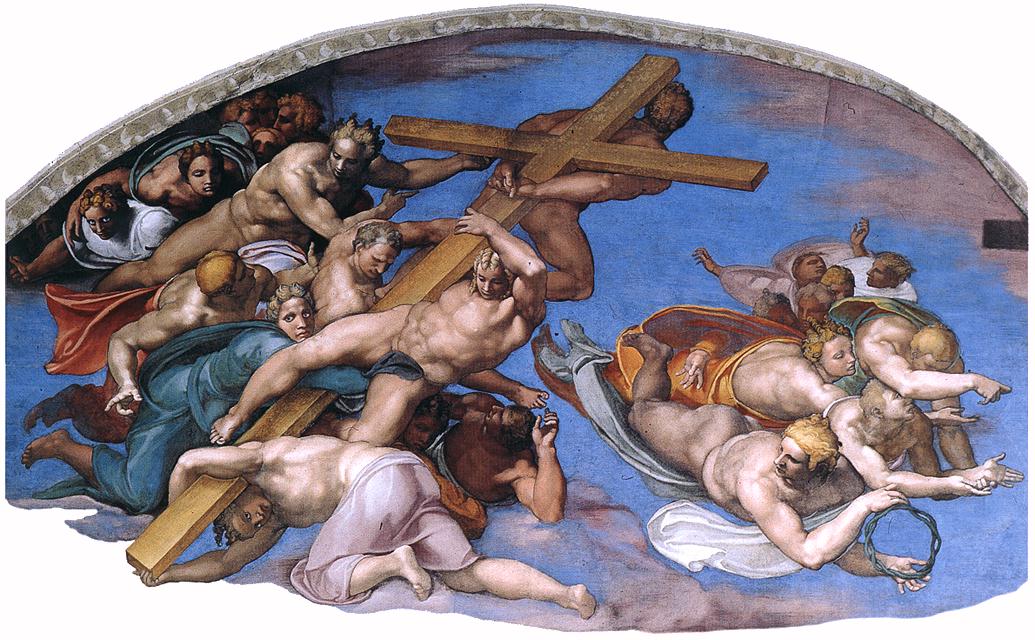

Our point of departure must be the area that Michelangelo painted first—the lunettes—beginning on the left.

All the angels are flying above us, but those bearing the Cross are not drawn from the same angle as those displaying the Crown of Thorns; and you should always keep in mind that there is no single consistent viewing point for all the groups in the fresco.

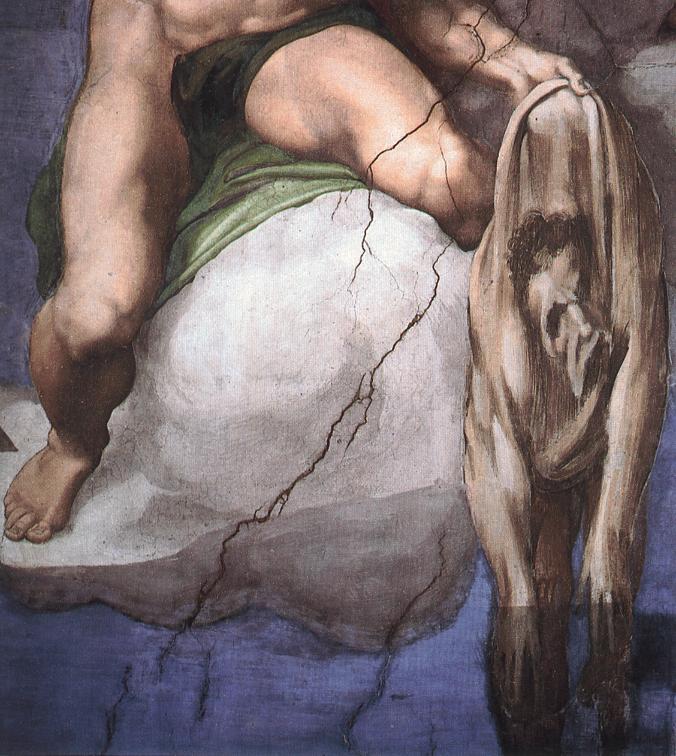

The figure style is more ‘mannered’ than it had been on the ceiling, much closer to the statues for the Medici tomb, as you can see above all in the extraordinary pose of the angel who is sprawled against the Cross. And, although it is anachronistic, I find it helpful to think of Michelangelo as trying to represent bodies in a condition of weightlessness.

How does one change direction in such a state? Well, today, by firing a little rocket laterally—but then, by having an angel drive in horizontally like a rugby lock forward.

Or—turning now to the other lunette, and pursuing the rugby football metaphor—you might think of the Column of Flagellation as being straightened up by having a flanker put his shoulder to the scrum, while other players prepare to launch into diving tackles.

The most striking, and the most mannerist, of the poses in the lunettes are to be seen in the lower details here.

The first of them anticipates a famous statue of Mercury by Giambologna (which became in its turn the model for the badge of the Royal Corps of Signals).

The last seems to be acting as a kind of human cushion; and his pose contains more than an echo of the position of Leda in Michelangelo’s lost painting of Leda and the Swan, or of his statue of La notte in the Medici chapel.

The next group lies well below the main central band on the wall, and was probably painted a good two years later.

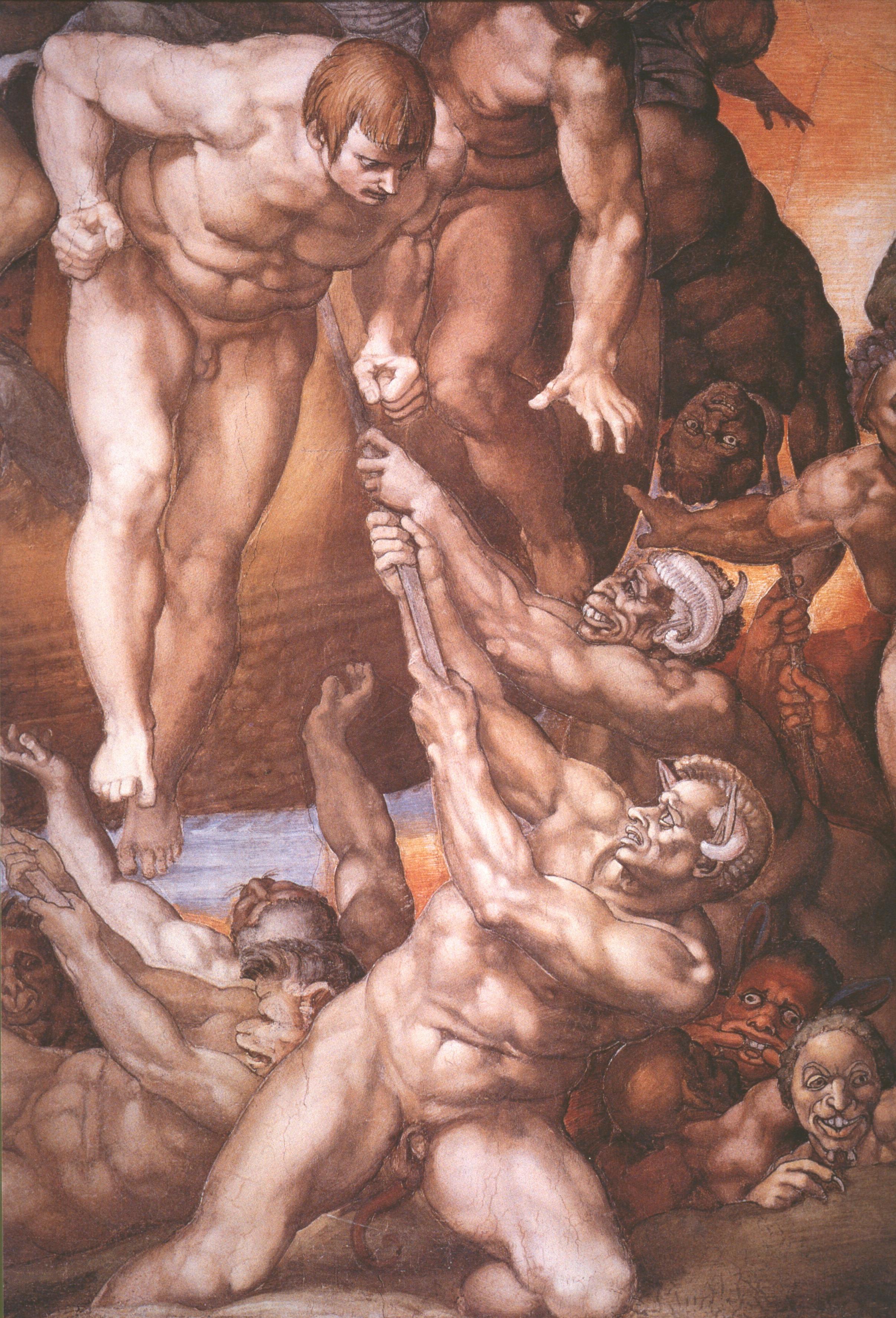

The very early drawing I showed you a little while ago revealed that Michelangelo had first conceived of this area as a struggle, with the damned attempting to ‘storm a citadel’ just as the giants had tried to scale Olympus.

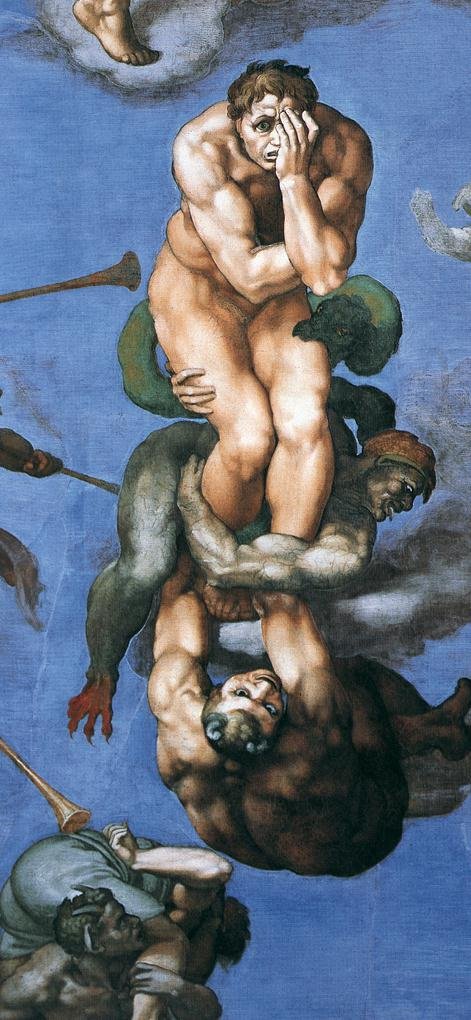

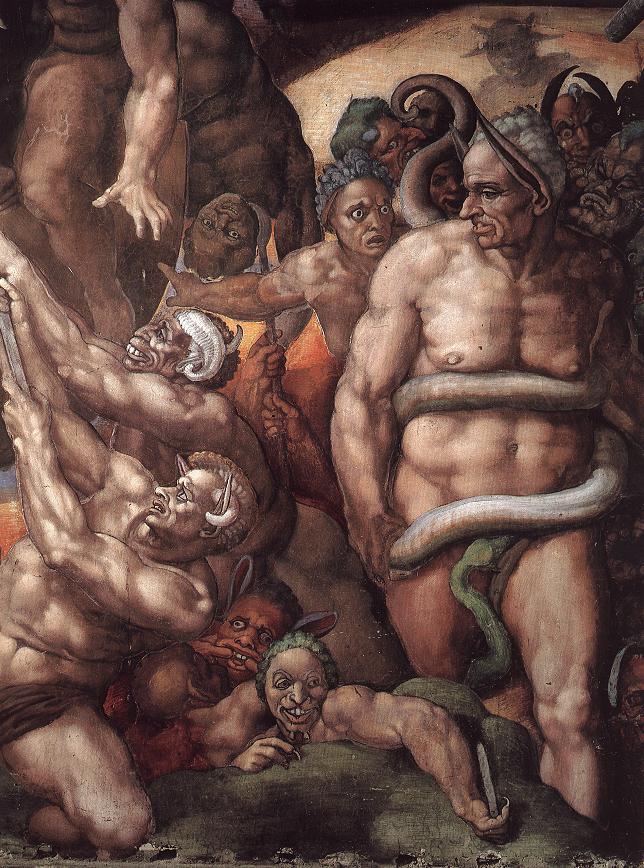

Well, a struggle it remains. The figures are indeed gigantic; and the one who shows us the mighty muscles in his back is putting up a stiff resistance. But there is no doubt about the outcome; and the damned are not only being driven down from above by angels, but also dragged down by demons, who are attacking from below.

Vasari and some later critics have allegorised this area, seeing it as a representation of the Seven Deadly Sins—in which case the defiant back might well belong to Pride, while the upside-down figure in the centre would definitely be Avarice, since he is being dragged down by his money-bags, and by the keys to the safe.

The same allegorists would read the isolated figure to the left of this group as Despair.

He is offering no resistance as he is pinioned and weighted down by no fewer than three devils—one at waist level, one round his knees, another, huge, upside-down below.

And what Despair is trying not to look at—but cannot resist looking at—is the scene in Charon’s landing craft, from which the damned souls are disembarking from the bow, assisted by the friendly demons on shore.

Dragged ashore by the demons, the souls hasten towards their judgement by Minos in a scene which is loosely inspired by Dante’s description of the infernal judge in the fifth canto of his Inferno.

Dante’s text is the source of the coils of the serpent. (The number of coils is Minos’s way of indicating the number of the circle in Hell to which the next damned soul must go.)

But Dante does not say what the serpent’s head is nibbling at here.

Nor does he mention that Minos has a woman’s breasts, and ass’s ears—nor the fact that his features are a caricature of the Pope’s Chamberlain, who had been getting on Michelangelo’s nerves!

We have seen groups falling through space (thanks to the weight of sin) or being dragged down by demons.

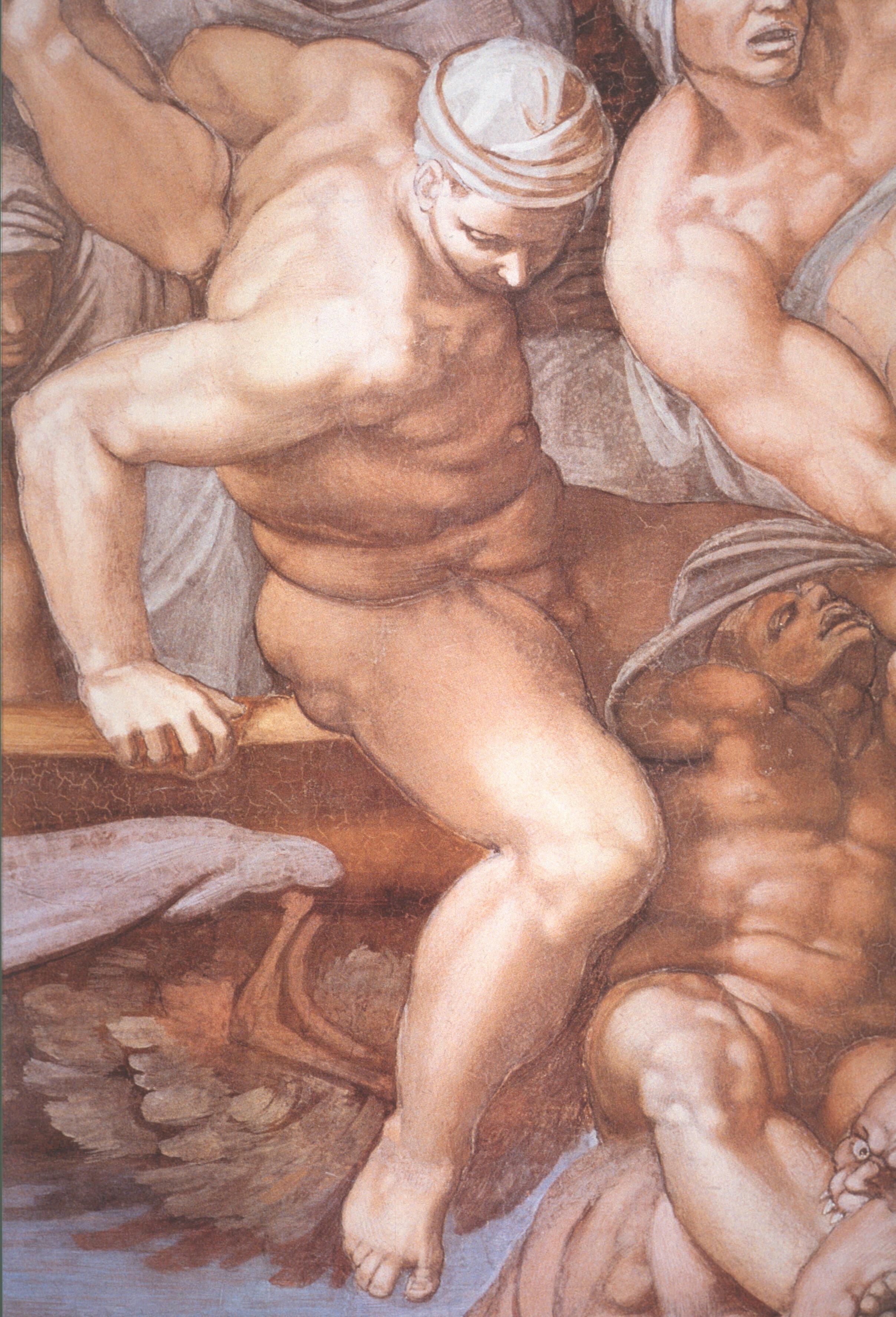

Now we must shift across to the left of the fresco, at ground level, to study the moment of Resurrection (thanks to Divine Grace) and register how the glorified bodies of the Blessed will now be able to defy the laws of gravity in free ascent (with occasional assistance from angels).

Michelangelo shows various distinct stages of ‘emergence’.

Two burrow forward like moles.

Another pushes back with both arms behind him (we saw him in the drawing earlier).

This area is one of the most loosely organised and also one of the most exciting in the whole composition.

It is a set of variations on the theme of naked bodies defying gravity and rising like to the surface like divers who have completed their task. (Remember that the loin-draperies were painted on later by another hand for the sake of decency.)

To the left, the ‘swing bowler’ figure in delivery stride.

Below him, a darker-skinned woman with hunched shoulders, knees drawn up, hands raised in supplication, head tilted back, eyes closed.

In the centre, a superb, heavily built decathlete, with one knee on a cloud, reaches up to the cloud above, as Adam had reached up for the fruit.

Further to the right, a younger athlete seems to be jogging up an invisible slope (his forefinger negligently crooked), apparently unconcerned by the draped women in the overlapping and receding group resting on the cloud behind him.

Below him, diminished by distance, are two figures who are still ascending (one with swept back ‘wings’, the other swaddled in his shroud).

The clouds are a bit like a cliff top, where rescuers are assembling to assist the unwary who have been trapped on the beach by the tide or a recent landslip. (You will think of your own analogies: rescue vessels in the Channel, perhaps, or aid lorries during a famine. The outstretched hands in this detail reminded me vividly of a newspaper photograph of refugees in Africa.)

We have almost completed our survey of what I called the outer circle, and we come to one of the densest areas of the whole fresco, where movements up or down are replaced by gestures, glances and strong torsions, expressing aspiration to the centre.

The figures are predominantly female; and I suggest you let your eye be guided initially by the rhythmic arrangement of their unclothed arms and backs.

Begin by tracing out the kneeling figure in the foreground (based on the classical statue of the ‘daughter of Niobe’) until you reach St Catherine (whose green robe, you remember, was supplied later for reasons of decorum by another hand).

Move sideways and climb again via the flank and back of the figure whose expressive pose resembles that of the Libyan Sibyl (in reverse). Then follow her gaze and gesture up to the two women, naked above the waist, who are reaching down to assist you. Then let your eye travel to the right again following the line of the hip and back of the dominant figure (she may be Eve), who is wearing nothing but a blue skull-cap.

To their right you can see the prominent figure whom Vasari took to be Adam, but modern critics agree must be St John the Baptist.

He is next to St Andrew (identified by his X-shaped cross), no less broad-hipped and powerfully muscled; while crouching between their legs, with his unmistakable red cloak and white beard, is none other than Father Christmas!

The Baptist’s gaze is very intense, and we may follow it right across to the other side of the centre to dwell for a moment on the interactions between the blessed.

Look first, though, at the astonishing representation of Simon the Cyrenian (who is supporting the full length of Christ’s cross, almost as if he himself were crucified), before letting your eye climb to the two huge nudes, who turn upwards to the left and right, to encounter the arms and meet the gaze of the pair above.

Keep going higher still to register some of the embraces as the souls recognise their friends and family who have also been saved.

Particularly moving is the ‘bear hug’ of greeting between re-united brothers (Michelangelo, as so often, is more moving in the pair where he does not show the facial expressions).

However, it is high time we began to direct our attention back towards the epicentre.

The pair in the detail you see here are as totally unexpected as any on the whole wall.

The bald-headed, bearded old man (said by some to be St Paul) seems to be risking a tricky step in a stately sarabande, while his blue-rinsed partner helps him by clapping the dotted rhythm.

We are definitely in the ‘inner ring’ now, high on the right, looking first at a varied group of old and young, men and women, secular and religious (notice the tonsured head of a deacon), who are all strongly lit by the celestial light emanating from Christ (look at the palm of the hand), and casting correspondingly strong shadows.

Below St Peter, you see St Bartholomew, who is holding the knife with which his skin was flayed in his martyrdom.

I deliberately focus your attention exclusively on the sloughed skin, where the face has the unmistakable features of the artist himself. (Acres of print have been dedicated to the biographical, psychological reasons for this unique decision by Michelangelo which has nothing to do with any iconographical tradition. But concentrate for this moment on his tour de force of spontaneous brushwork!)

But now on to the triumphant climax of this seconda visione (which will take us back to the beginning of the prima visione , where I was relying on the laconic commentaries of Condivi and Vasari).

Follow the gaze of St Laurence and the living Bartholomew (at the bottom of this splendid detail) up to the Son of God and the Virgin Mary.

Mary turns her eyes away from the punishment of the damned.

Her role as Mediatrix is over.

She tilted the balance in favour of individual sinners by interceding on their behalf and pleading for mercy as long as pleas could be heard. She is resigned to the rigour of divine justice, but she cannot bring herself to smile in welcome at the new arrivals in heaven.

(One observation only about technique.

The huge enlargement allows us to see that Michelangelo was still painting like a sculptor in his sixties—jabbing the bristles on his brush into the wet plaster as though they were the teeth of his favourite claw chisel biting into stone.)

Her Son—the Son of Man and the Son of God—has the colossal body of Apollo—the Olympian Sun-God.

His totally original pose combines elements of a Resurrection and Ascension, as found in earlier Christian Art, with the energy of Jupiter hurling a thunderbolt.

He is the dynamic centre, whose arm-movements—down and across, up and across—seem to determine the movement and position of every figure in the vortex of his influence.

His face is illuminated by a divine source of light from high to the left, so that even the downward-looking eye we can see is mostly in shadow, and the inward-looking expression remains as inscrutable as it ever was (even after the dirt was removed in the 1990s): not Christian, not pagan, neither medieval nor modern, but certainly more than human—perhaps simply michelangiolesco.

PB (2025)

Manum de tavola!