Introduction: The Virgin, the Nobles and the Nine

As the title suggests, all seven lectures in this series will present narrative cycles which are in some way associated with the city of Siena—although I do not promise that every picture is actually in Siena, or by a Sienese, or painted on a wall.

(I shall, however, be offering something like an introduction to early Italian Art in general, even though I shall concentrate on just one artist in each lecture and limit myself to a thorough discussion of one ‘painted story’—a story in many scenes, done for a particular building and a particular patron, in particular circumstances.)

We shall look at one such narrative cycle at the end of this first lecture, but I would like to launch the series by telling you about Siena itself—showing you the city as it now is, before going on to explain how it grew up, politically and socially, and how it was organised some seven hundred years ago.

You may have already been to Siena, possibly on a day trip.

If so, you were probably taking a coach from Florence and you will remember this characteristic view of the edge of the town taken from fairly close to the coach station, near the church of San Domenico.

You will probably also know the single most important fact about Siena.

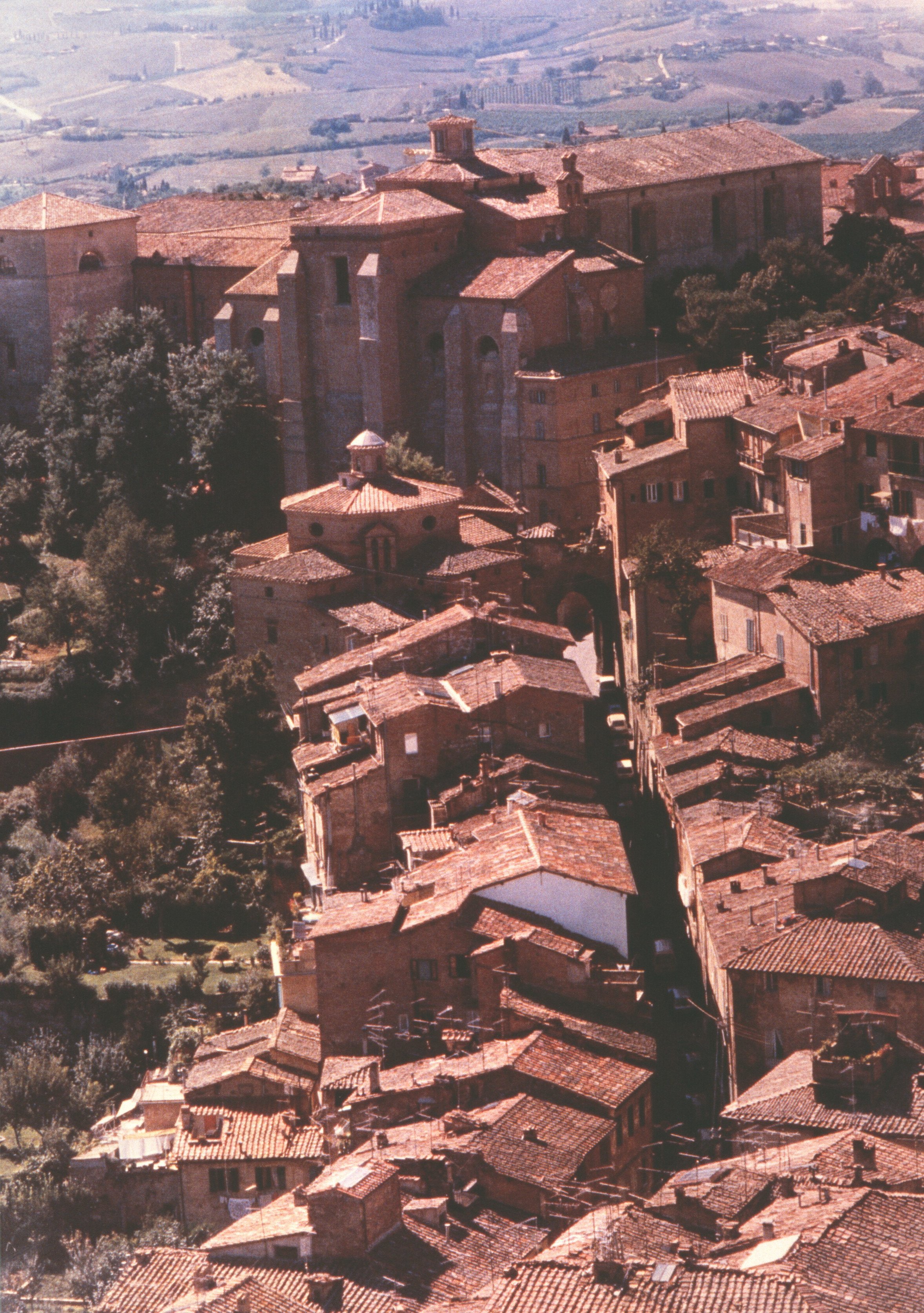

Unlike Florence, which lies in the flood plain of a major river, Siena is situated on the top of a hill about one thousand feet above sea level. And unlike Florence, where almost all the buildings are covered in plaster—‘intonaco’—Siena still displays the local brick, which has the glorious warmth of the colour they used to put in children’s paint boxes, where, next to the ‘Crimson Lake’, we dipped the brush in ‘Burnt Sienna’.

The medieval city spread as far down the complex slopes of the hill as the pressure of population and the need for defence allowed, coming to an abrupt halt at the line of the city wall. The result is that the reddish, ‘burnt Sienna’ colour of the walls is set directly against the green of the trees and the grass and other vegetation. The irregular shape of the hill also means that there are many little green valleys cutting into the city.

Because of the curves and the rise and fall, you cannot see much of Siena at a time from ground level.

You must either see it outside, from a distance, or go up in a helicopter before you can get a sense of the whole city, as in this glorious image, showing the densely packed buildings in the narrow streets around and between the cathedral and the Palazzo Pubblico.

Now that you have had a chance to visualise the red brick city on the green hill with its black and white marble cathedral, I will try to place it in its geographical and historical context.

In the period that interests us, Siena was one of many self-governing communes in central and northern Italy.

A hundred years later, in 1350, the area under its control—the ‘contado’, (again coloured purple on the map)—had expanded considerably to the south west, and it probably contained a population of between 80,000 and 100,000 inhabitants in the decades before the coming of the Black Death.

As you can see, its closest neighbours in Tuscany were the city states of Pisa and Lucca (with whom Siena enjoyed quite good relations), and, very close to the north, the dominant republic of Florence, with whom Siena was regularly at war in the thirteenth century, losing four battles in the period before 1250, gaining an annihilating victory in 1260 at the battle of Montaperti, and then losing decisively at Colle Val d’Elsa in 1269.

The underlying reasons for the importance of Siena—and for its inevitable decline—are best appreciated on the plastic relief map, which gives a vivid impression of the terrain.

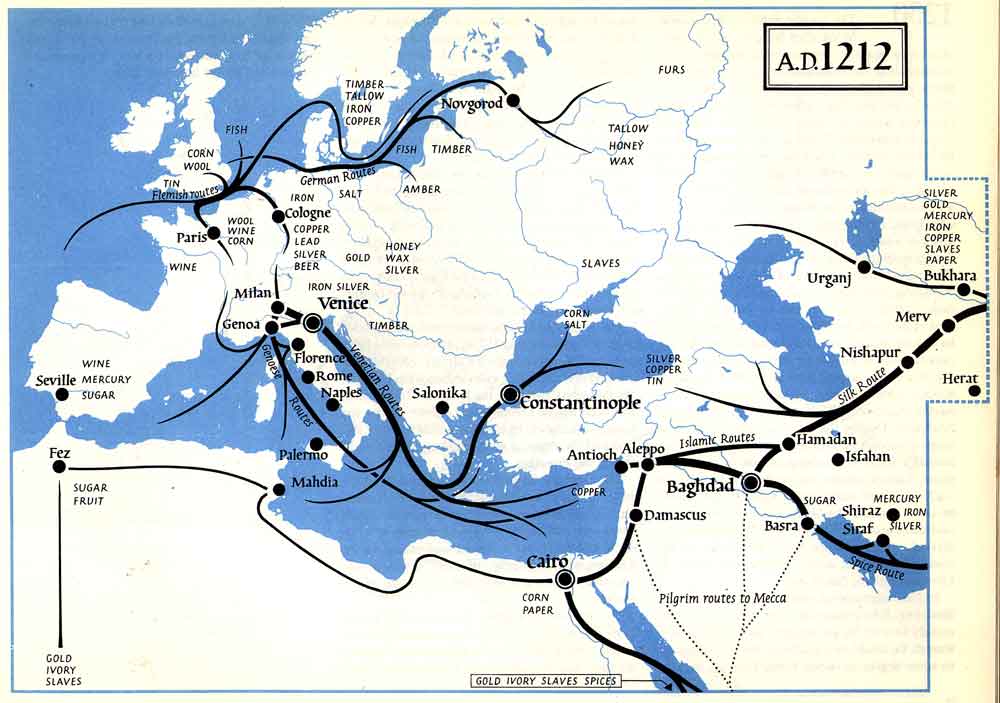

From the eighth century onwards, Siena lay on one of the most important routes—for trade, pilgrims, and diplomats—linking Rome with northwest Italy and with France.

It was known as the ‘Frankish Way’. (The course of the Via Francígena has been traced by hand in the curving red line added to the photograph of the map.)

Coming to the city from the north, you would come as far as Parma in the valley of the river Po, traverse the Appennines by a pass which followed the valley of the river Serchio to Lucca, then cross the Arno and follow the line of the Elsa valley up to Siena, from where the route lay across broken country to the lake of Bolsena and Viterbo, 75 miles to the south.

Siena was the only major staging post between Lucca and Viterbo.

Returning from Rome, this lower part of the same route would be used by travellers going to Bologna, Venice, and Austria.

The hills in the Sienese contado are not very high and could provide abundant grain, olives and wine, as well as abundant pasture for livestock.

This, so to speak, is the good news.

The bad news is that there is no substantial water course anywhere near the city (the Elsa, Arbia and Cecina are all quite small). And although the spring line for water is not far below the hilltops, Siena never had enough water for domestic or industrial use, and it never had control of a major port on the coast.

Medieval legend attributed the founding of the city to the less well known of the twin sons of Mars and the Vestal Virgin—Remus, not Romulus; and in 1297 the city adopted the wolf that had suckled the infant twins as one of its emblems, thereby claiming an antiquity equal with Rome itself.

In reality, it was a late and minor Etruscan settlement, which first appears in historical records as Sena in 29 BC, when it was granted the status of a Roman colony by Augustus.

There is virtually no trace of the original settlement—as there is, for example, in the centre of Florence.

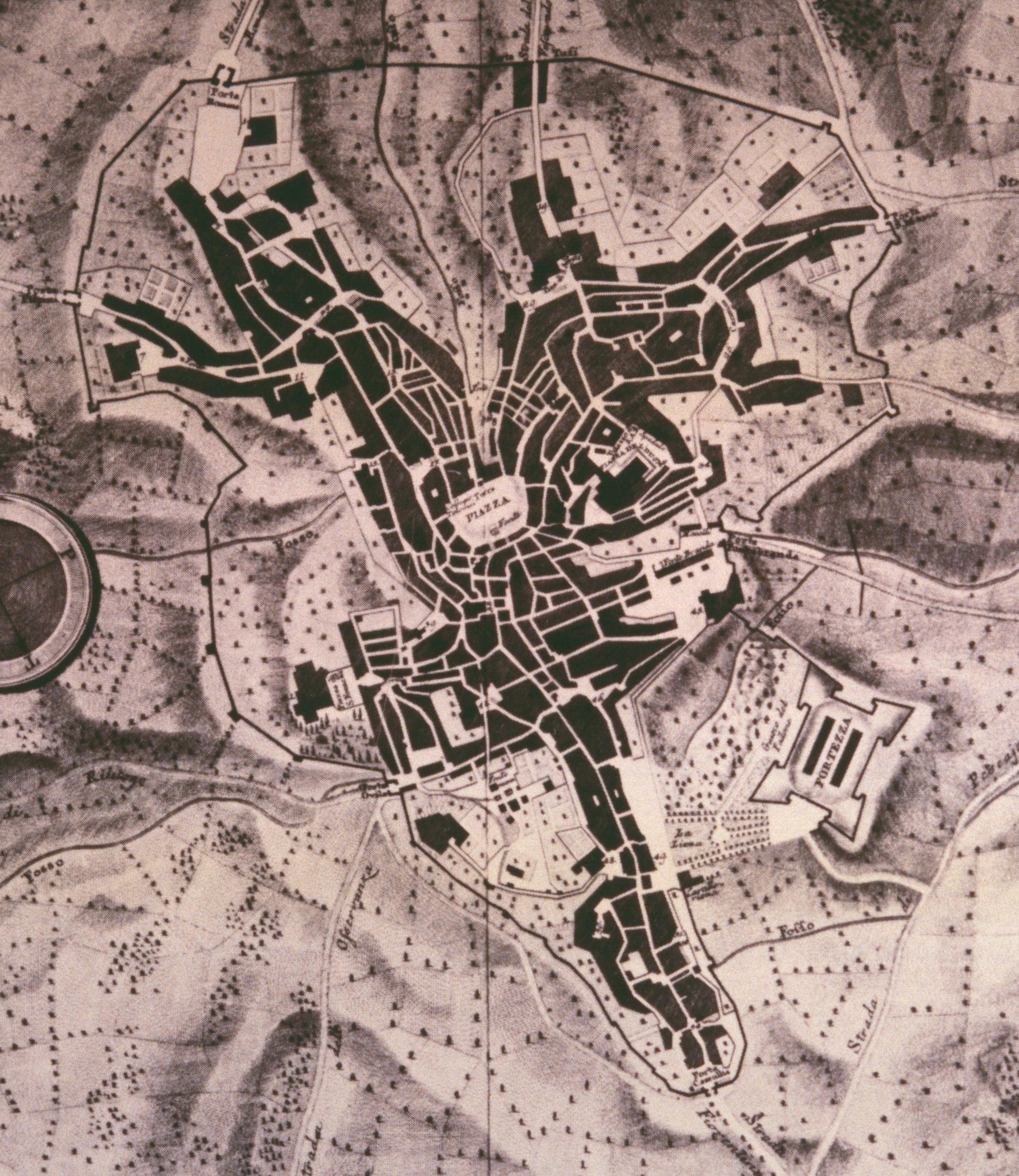

The city is built not on seven hills, like Rome, but where a ridge running roughly north–south, forks into two, to give a total of three hills forming a rather lopsided lambda, or an inverted Y.

(The three ridges were and remain the main thoroughfares, leading to Lucca in the north, and to Grosseto and Rome in the south.)

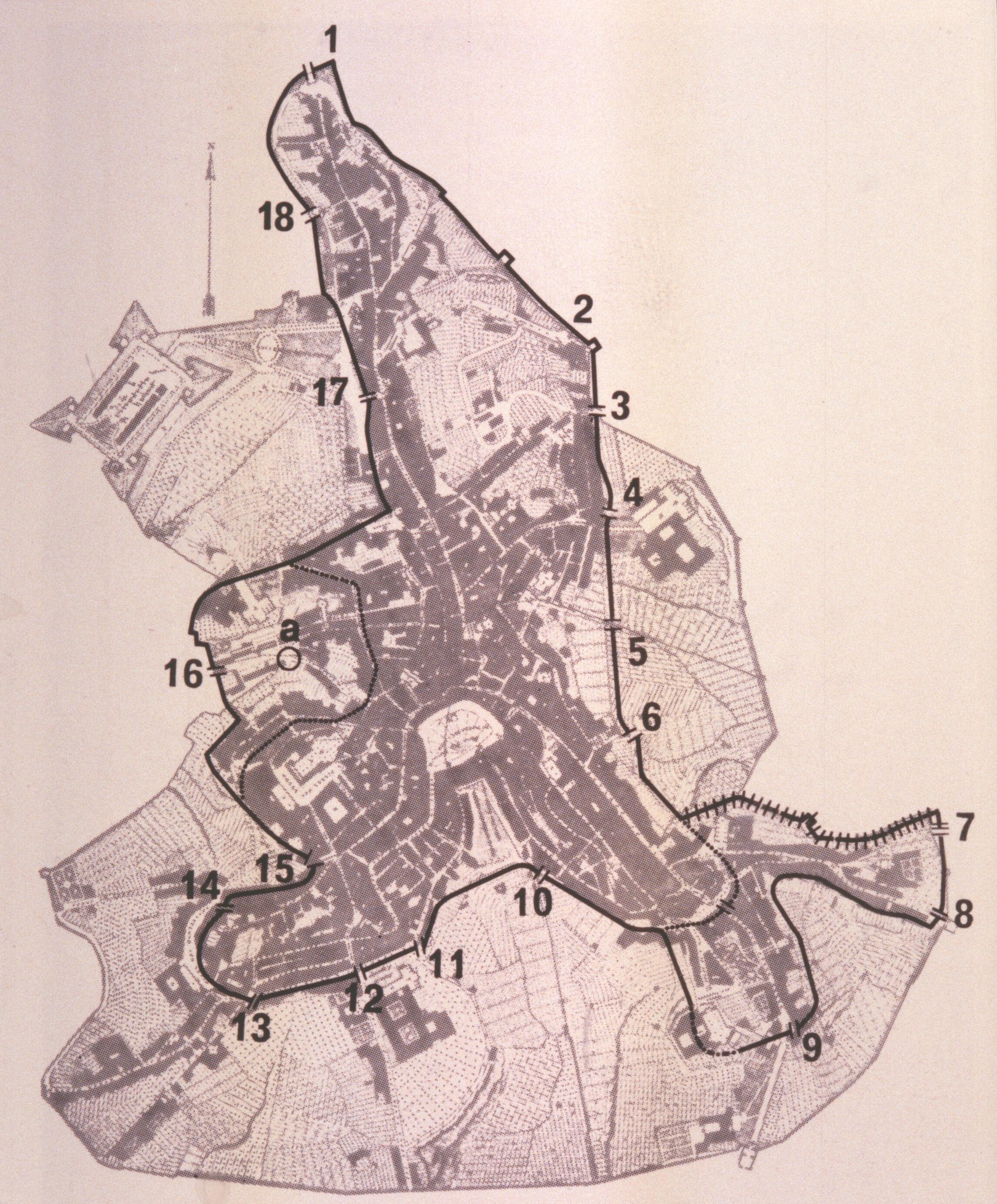

You can see the shape of the original core of the city very clearly in the dark areas of a plan, published in 1832.

Notice in particular the prominent, central position of the Campo, lying in the ‘crotch’ between the ‘legs’ of the Y.

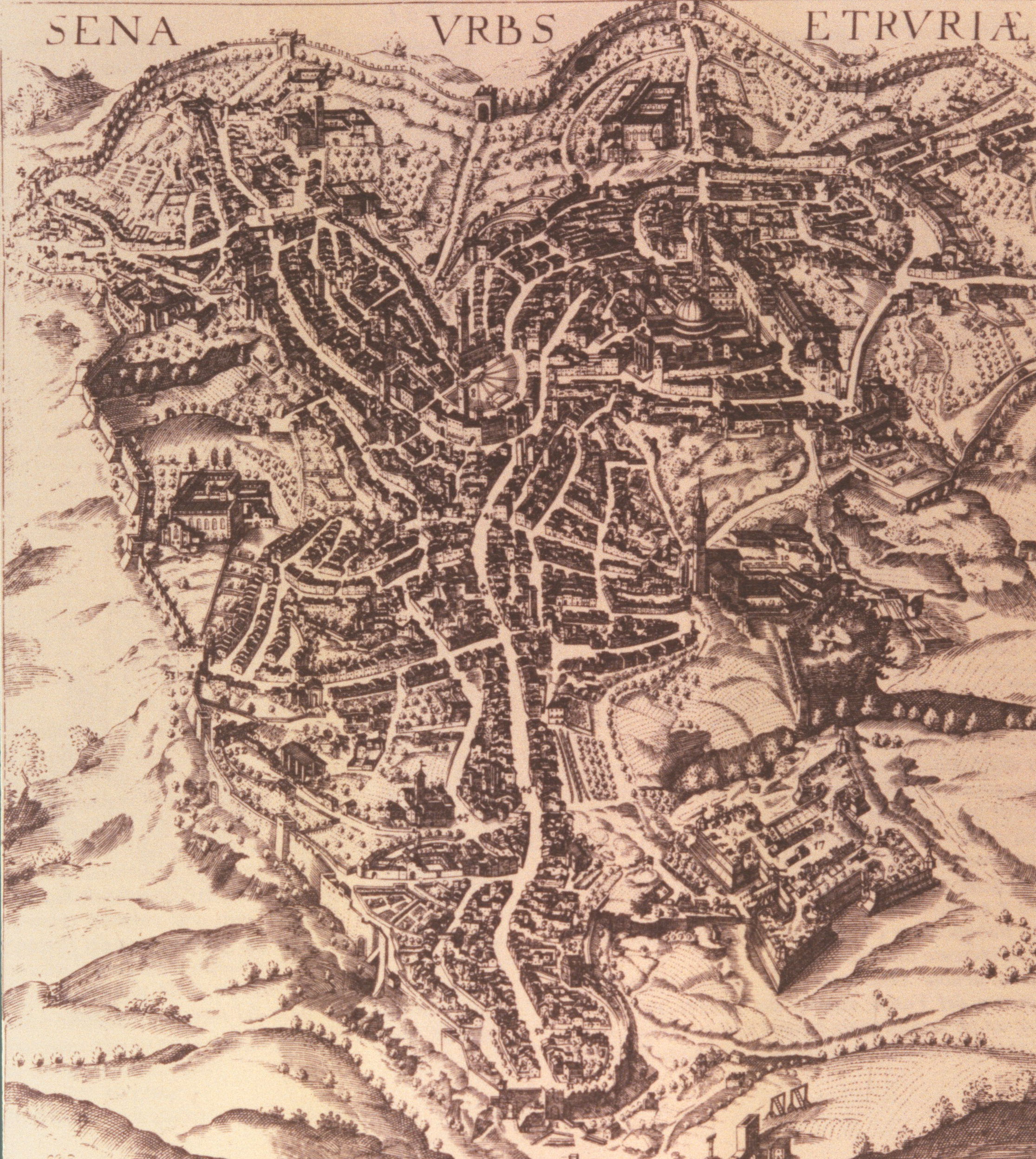

If you adjust your brain to the inverted orientation of a slightly earlier plan (with south at the top, and the ‘legs’ becoming ‘arms’), you will get a very good sense of the lie of the surrounding land from the relief shading; and you will also be ready to appreciate the magnificent piece of perspective below, showing the city as it was in the Renaissance, around 1600, not long after Siena had been absorbed into the Grand Duchy of Tuscany, under the Medici.

(Clearly visible are the road from Florence or Lucca; the Campo and the Palazzo Pubblico; the roads to Grosseto and Rome; and the Cathedral on the south western spur, near the centre of the earliest settlement on the site, and on the highest ground.)

You have now seen Siena as it is today, and registered the ancient core of the site in its permanent geographical context; while the last image shows the Renaissance city in its still recognisable definitive form.

We must now begin to focus on the medieval city, in or about the year 1300, and look at the role played in the formation of the city by the ‘three estates’—Church, Aristocracy, and Bourgeoisie—to which the title of this lecture alludes: ‘The Virgin, the Nobles and the Nine’.

The high viewing point used in the 1572 engraving does give a slightly misleading impression of the historical city, because it flattens the numerous towers that used to dominate the skyline, as is shown more clearly in the eighteenth-century engraving.

We must keep in mind, then, that medieval and Renaissance Siena used to look very much like the neighbouring town of San Gimignano still does, with a forest of towers rising above the walls at the top of a hill. One old chronicler said that Siena looked ‘like a reed bed’, a ‘canneto’.

Many of these towers were bell towers (‘campanili’), like those of the two highest, the Cathedral and the Palazzo Pubblico. But the majority had been built by noble families in the middle ages, partly as private fortresses against each other and against the citizens, partly as symbols of their family pride and of the distinctive and disruptive lifestyle, so brilliantly conveyed by Shakespeare in Romeo and Juliet.

Although the nobles were in fact debarred from participation in government in the years around 1300, they were always a major presence in the city, and they dominated its fortunes again, disastrously, in the later fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries.

These families were the remote descendants of a feudal nobility, who had been granted lands in Tuscany following the collapse of the Roman Empire. Italy was invaded, first by the Goths, then by the Lombards (who governed Tuscany from the city of Lucca from the sixth to the eighth centuries), and finally by the Franks, under Charlemagne in the ninth century, when Tuscany became a Marquisate, still centred in Lucca. This survived as an administrative unit until the beginning of the twelfth century, the last effective ruler being the famous Countess Matelda, who died in 1115.

These local lords, living on their ‘domains’ in fortresses, or in fortified manor houses, were inevitably the enemies of the expanding cities in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, as the cities sought to obtain direct control over their surrounding territories. In Siena, as elsewhere, over a very long period they were forced to build residences in the city and to live there most of the year—hence the towers.

But the nobles kept their hereditary lands, and they kept their income as landlords; they maintained their traditional role as ‘horse soldiers’, cavalrymen, ‘knights’—the ‘officer class’ needed for defence. They retained their cult of honour and of the ‘clan’ (with the consequent duty to pursue vendettas), and they kept their contempt for the ‘villeins’, that is, the artisans and the tradesmen. Thus, even when they were excluded from political office, the nobles were extremely influential, and extremely troublesome, within the city—facts nicely symbolised in the rival towers that dominated the skyline.

I am giving the nobles rather a ‘bad press’, which I will correct a little by glancing at a charming sequence of sonnets written in or about 1300, by a nobleman, Folgore, who took his surname from the nearby town of San Gimignano.

In the introductory sonnet, Folgore addresses himself to a ‘noble and courteous company’ of his friends in Siena, and suggests the nature of their literary tastes by comparing them to the heroes of Arthurian romance. They are ‘more courteous and bold than Lancelot’; and ‘if the need arose, with lance in hand, they would joust in tournaments at Camelot’. (Lord Tennyson was not the first poet to rhyme ‘Lancelot’ and ‘Camelot’).

Alla brigata nobile e cortese,…

prodi e cortesi più che Lancilotto,

se bisognasse, con le lance in mano

farian tornïamenti a Camellotto. (I, 1, 12–14)

Folgore then addresses twelve sonnets to these friends in which he ‘gives’ them—or ‘wishes them the enjoyment of’—the appropriate pastime for each month of the year, and in so doing, he give us an excellent idea of their tastes and fantasies.

In January, for example:

‘I grant you…. to go outside sometimes during the day, throwing the white and lovely snow at the girls around you’:

I’ doto voi, del mese di gennaio…

uscir di fuori alcuna volta il giorno,

gittando della neve bella e bianca

alle donzelle che saran d’intorno; (II, 1, 9–11)

To illustrate these lines, I cannot resist showing you the detail of a fresco in Trento in which some very non-Sienese nobles are throwing snowballs in the month of January.

In February, he wishes them ‘good hunting of deer, roebucks, and wild boar, returning in the evening with your followers, weighed down with game, rejoicing and singing’:

E di febbraio vi dono bella caccia

di cerbi, cavrïuoli e di cinghiari…

e la sera tornar co’ vostri fanti

carcati della molta salvaggina,

avendo gioia ed allegrezza e canti. (III, 1–2, 9–11)

In March, he ‘gives’ them a ‘fishpond, with trouts, eels, lamprey and salmon’—and ‘may there be no church or monastery; but let the mad priests do the preaching, who tell a lot of lies and little truth’:

Di marzo sì vi do una peschiera

di trote, anguille, lamprede e salmoni….

Chiesa non v’abbia mai né monistero:

lasciate predicar i preti pazzi,

ché hanno assai bugie e poco vero. (IV, 1–2, 12–14)

April brings the Spring; and he wishes them ‘the lovely countryside, all flowering with fresh grass; fountains of water for delight; and ladies and girls for company; ambling palfreys, war horses from Spain, servants in livery of the French style; singing and dancing like they do in Provence, with newfangled instruments from Germany’ (the upper classes always looked to the North for the latest fashions and pleasures).

D’april vi dono la gentil campagna

tutta fiorita di bell’ erba fresca;

fontane d’acqua, che non vi rincresca;

donne e donzelle per vostra compagna;

ambianti palafren’, destrier’ di Spagna

e gente costumata alla Francesca;

cantar, danzar alla provenzalesca

con istormenti nuovi della Magna. (V, 1–8)

From the nobles, I pass to the ‘priests’ and to their ‘monasteries’ and ‘churches’. And just as I tried to link the nobility to their towers, so I shall try and relate all the essential facts about religion and the church to just one building.

This is the ‘Cathedral’, the ‘seat’ of the Bishop of Siena, which you see in its context, as it now is, and, below, as it was back in the year 1224, before the present façade was added.

(Notice the fortified towers of the city, rising behind the bands of black and white.)

Siena grew by an accretion of small settlements like those indicated in the diagram, beginning with a fortress (to the north, at the spot marked A), moving up the northern ridge in the twelfth century, and out to the south east in the thirteenth century.

Each such settlement had its own church as its focus of loyalty, and always felt itself to be as distinct, as (for example) West Ham, Tottenham, Millwall, Fulham or Chelsea still do today.

In due course, however, the earliest of the religious sites (at the spot marked C), had become the site of the Bishop’s church, with his palace alongside. And you must bear in mind that for about 250 years—from 900 to about 1150—the Bishop had become the feudal overlord, holding the city as tenant ‘in chief’ from the Marquess of Tuscany.

It was the Bishop to whom the citizens looked for justice and for defence.

Obviously, as the township governed by a Bishop slowly evolved into a self-governing city-state, there came conflicts of interest between the church and the laity. But remember that, just as the local parish church was the prime centre of loyalty in everyday life, the Bishop’s church—the Cathedral—became a very important focus of civic identity, and of civic unity and pride.

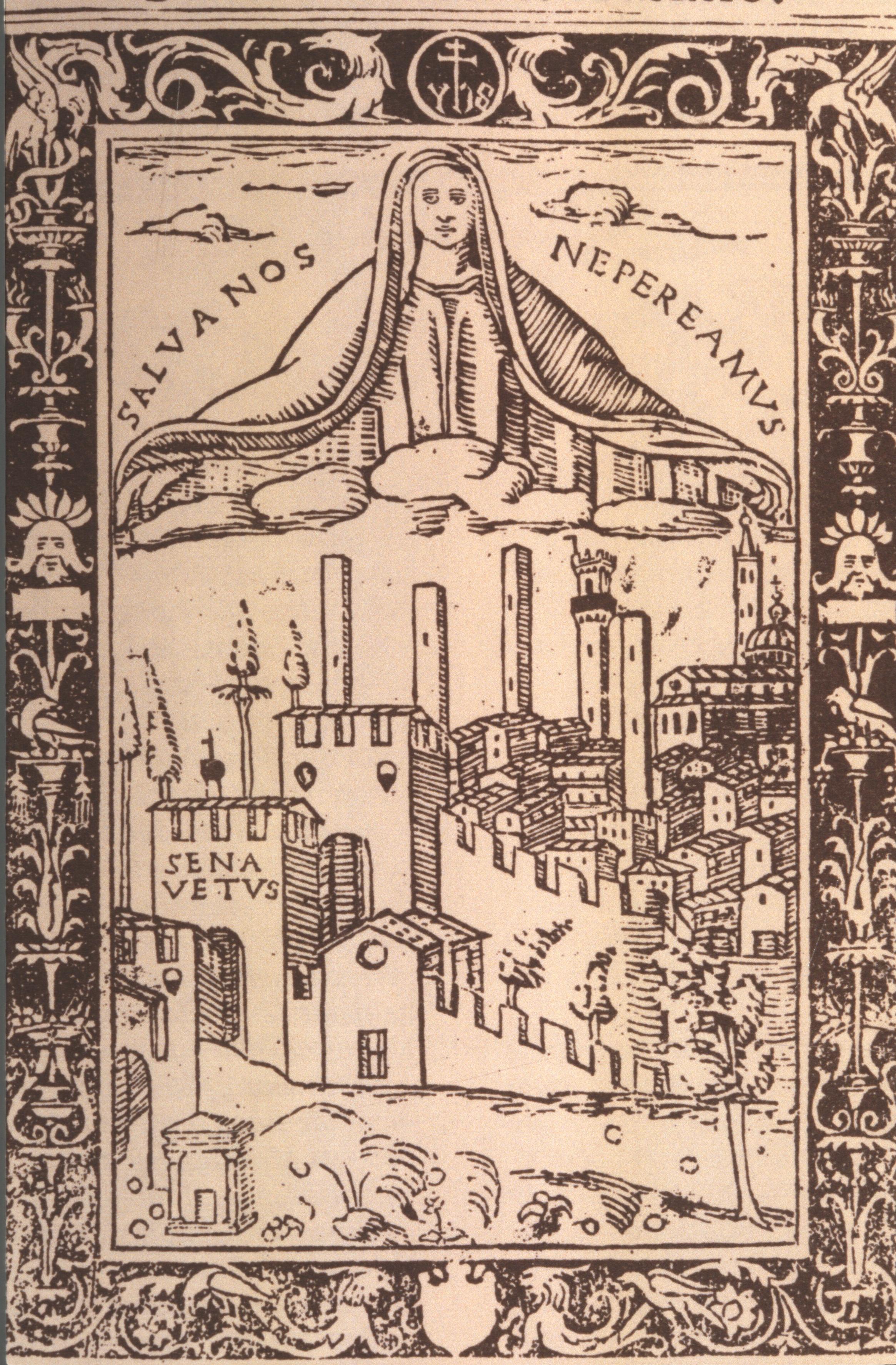

The Cathedral, in the Commune’s colours of black and white, is dedicated to the Virgin Mary; and the whole Commune had placed itself under her protection (in an extraordinary manifestation of mass piety) immediately before Siena’s only major victory against the Florentines, the Battle of Montaperti in 1260.

This dedication and this victory were still being celebrated in 1502 in the splendidly iconic woodcut, where the Virgin spreads her protective mantle over ‘ancient Siena’ (Sena vetus) in response to the prayer: ‘Save us lest we perish’ (Salva nos, ne pereamus).

The Commune frequently renewed its act of self dedication to Mary, as when, under military threat in the 1480s, the citizens consigned the keys of the city to the Virgin in the Cathedral.

(Notice how the image of the Virgin, placed over an altar in a side-chapel, leans forward, miraculously, to receive the keys.)

There are many similar images in Sienese art, showing the power of religious feeling, but perhaps the most poignant is the Madonna of Mercy, from the year 1335, who is shown protecting clergy and laity alike under her cloak.

Alas, she was unable to prevent at least half of them from being wiped out by the Black Death only fifteen years later.

Having dealt very briefly with the ‘Virgin’ and the ‘Nobles’, let us now approach the ‘Nine’, by noting the expansion of Siena through the successive enlargements of the city wall, bearing in mind that every time another stretch of wall was built, new houses would be built immediately outside the wall where the lie of the land permitted it.

The earliest wall enclosed the Cathedral and the ‘Old Castle’ in a ‘butterfly shape’. By 1150, it had ten gates, and took in the ridge of the northern hill, ‘Camollia’.

Fifty years later, in 1200, the ‘Camollia’ wall had moved well to the east, and part of the third hill was included. There were sixteen gates.

By 1250 expansion had continued to the south east. There were now 18 gates, and the population had reached about 20,000. By 1300, the population is estimated to have been about 25,000, and the wall enclosed 125 acres, which is to say about half the size of Florence at that time.

Just before the Black Death in 1348, there may have been 35,000–45,000 people within the walls, living in the kind of density suggested by the aerial photo of the area near the Campo.

Within those walls, as I have hinted, there were intense divisions and rivalries, focused on the ecclesiastical parish and on the slightly larger civil parish, called a ‘contrada’.

The Palio is still bitterly contested, twice a year, by the 17 surviving ‘contrade’.

At a slightly higher level again, the Sienese also felt that every person belonged to their own ‘Terzo’, the city having been divided into thirds, one to each of the main hills, in order to ensure fair representation.

One reason why the Campo came to be the site of the mighty Palazzo Pubblico was that it lay in a ‘no man’s valley’, where the three ‘Thirds’ joined.

The social groups behind this steady growth were neither the feudal aristocracy, nor the day labourers, but the shopkeepers and craftsmen who produced goods to sell and who organised themselves into what came to be called the ‘minor’ guilds and were known collectively as the ‘popolo minuto’—and above all, the citizen elite, the ‘popolo grasso’, the entrepreneurial class of the ‘major guilds’ who lived by trade and by activities connected with trade: tax collecting for the papacy, money lending, banking for the rulers of Europe.

Such, then, was the group whose rise to influence and power within the commune is inseparable from the commune’s path to increased independence within the old feudal hierarchy.

Bearing in mind that a similar process was going on (with considerable local variations in time and space) in communes all over Tuscany and the North, we can chart the advance of the ‘popolo grasso’ in Siena through a list of three significant dates:

the recognition of a citizen class (1137);

the establishment of a permanent council on which that class has a voice (1176);

and then, in 1192, the formation of the professional body to which most of the new politicians will belong, the Merchants’ Guild.

The early years of the new century witnessed a period of civil unrest, culminating when the popolo gained half the seats in the executive body in 1233. This led in turn to the drafting of a written constitution with elaborate safeguards for the popolo.

After the fall of the pro-imperial Ghibelline faction (in 1271), all nobles were excluded from the executive body in 1280. In 1287, finally, came the classic revision of the constitution, which remained in force until 1355—the rule of ‘The Nine’.

Under this constitution, the executive was formed of nine members, rotating every two months, all of them being drawn from the ‘middle people’, that is, from the non-noble merchants and bankers.

Here are a few facts about the classic form of government as it would have been in the year 1300.

The ‘House of Commons’, so to speak, was the Great Council, or ‘Council of the Bell’, which met in the newly completed Palazzo Pubblico, in what is now called the ‘Sala del Mappamundo’.

The Council had three hundred members, drawn evenly from each Third of the city, serving for one year, with meetings held once or sometimes twice a week. Most of the business was taken ‘on the nod’—that is, it required approval of what the executive proposed—but the Council was also the forum for public debate on all major issues of policy.

It acted as a court of appeal; and it was only by a two thirds majority vote, in a secret ballot, that new legislation could be approved, the constitution amended, or the balloted selection of the executive endorsed.

Day to day decision making was done by the so called ‘Concistoro’, elsewhere known as a ‘Priorate’ or ‘Magistracy’; and it is in this group that we see the obsession—found in almost all the Italian communes—with power sharing and the rapid rotation of office in order to prevent the rise of a dictatorship.

The head of the executive—known in Siena, as almost universally, as the ‘Podestà’—served for only six months at a time and could not serve again for a further five years.

He was never a Sienese, rarely even a Tuscan, but typically a nobleman from the centre of Italy or from the north, who made a career as a professional administrator, passing from one city to the next like the manager of a modern football team.

Chosen on his past record by the outgoing Concistoro, he received a generous salary (from which he had to pay his personal retinue—all non-Sienese—consisting of a dozen judges and notaries, and about forty men at arms); but he only got the final instalment of that salary—about 15%—after he had ‘rendered his account’ at the end of his brief term of office.

Effective decision-making lay in the hands of the ‘Nine Governors and Defenders’, three members from each third of the city, serving for only two months.

The Nine were chosen by lot; and to be eligible, one had to be over thirty, non-noble, Guelph.

During their term of office, they lived together in the Palazzo Pubblico and they met daily in the chamber now called ‘La Sala della Pace’.

The Nine were joined in their deliberations by ex officio members, whose own terms of office were also very brief—usually not much more than six months.

(To use anachronistic terms, these members were the four ‘Treasury Ministers’, the ‘Director of the FBI’, the ‘Chairman of the Ruling Party’, and the ‘Minister of Health and Social Security’.)

The Concistoro had to cope with an extraordinary range of business; and the abundant archives show them dealing with foreign policy, defence, taxation, famine relief, the water supply, public health, poor relief, protection of orphans, the prisons, the police force, and a small but flourishing university. Overall, they did their job with genuine public spirit, imagination and flexibility.

The disadvantages of the system will be blindingly obvious—discontinuity, above all; institutionalised divisions; jealousy from the excluded nobility and the labouring poor.

But the system did ensure that a very large number of the most able citizens participated directly in the affairs of the commune: about one thousand different names are recorded over the crucial seventy year span as having served on the Nine.

It was their conscious and frequent decisions about urban planning which gave definitive form to the Campo and to the Palazzo Pubblico, as seen in the fifteenth-century view of San Bernardino preaching.

It was their decisions, too, which gave definitive form to the appearance of the rest of the walled city, the essence of which is brilliantly conveyed in the simplified model, here being blessed by its patron saint.

(The painting is from the early fifteenth century. Notice the bands of black and white marble on the cathedral; the tower of the Palazzo Pubblico; and the city gate in the red brick wall.)

That is the end of the historical part of this introductory lecture; and it is high time that we moved on to look at the art-historical context.

The pictures that form the subject of the next three lectures were painted between 1300 and 1350, under the rule of the Nine; and since we shall be concerned with images that tell a story and represent the world of experience, it will be convenient to ‘get our eye in’ by examining two earlier works containing narrative panels. The first of these was painted in about 1220, the second in the 1270s; and both are characterised by certain features which will always be characteristic of Sienese painting.

The earlier of the two is an altar frontal, measuring about three feet by six. (It is now in the picture gallery in Siena.) The six little narratives flank a figure representing Christ as Redeemer. (He is haloed, framed by a mandorla of stars, and worshipped by two angels.) The traditional symbols of the four Evangelists appear in the corners.

The narratives themselves here are too ‘rubbed’ for us to enjoy, but notice the typical combination in a single design of a large scale image, which would be clearly visible from the back of a church, with smaller panels intended for the edification and enjoyment of the celebrant of the Mass.

And look more closely at the detail of the winged lion (the emblem of St Mark), where you should register four things in particular: the stylised, archaic treatment of the lion’s rib cage and head (there are, so to speak, separate viewpoints for the eyes and the mouth); the superb confidence of the sweeping line defining his back and tail; the nervous energy in his very heraldic legs and paws; and the depth and warmth of the colours—browns, deep blue, and red, against a gold ground.

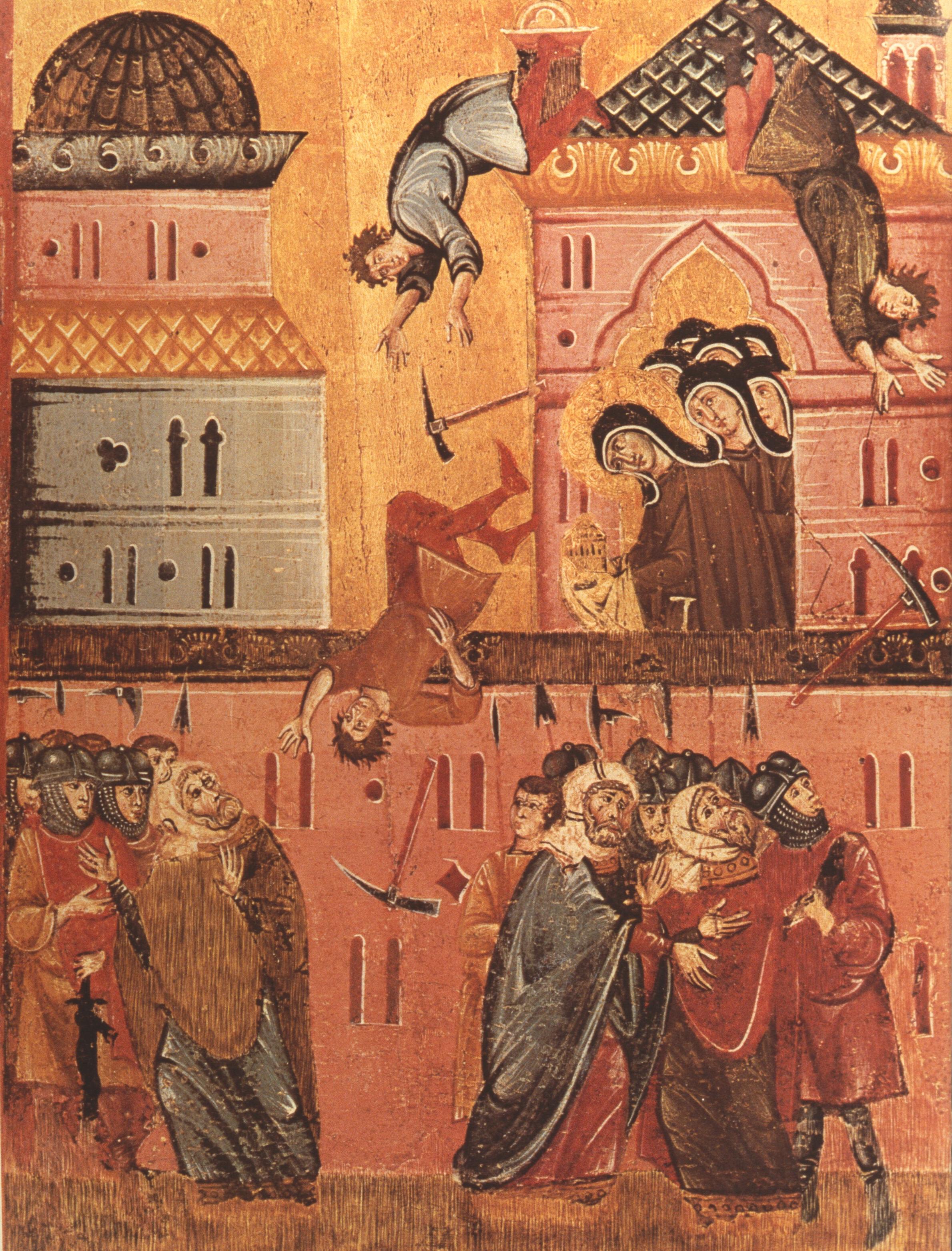

In the fourth scene (bottom right; about eighteen inches high), you can see St Catherine of Alexandria strapped on a ‘spit’, so to speak, and miraculously unharmed by the flames on the wheel which the torturers are rotating underneath her. (This is the scene which gave rise to the name, a ‘Catherine Wheel’).

Meanwhile the emperor looks down from the simple ‘pictogram’ which represents, here, an imperial palace. You can see again just how important the warm Sienese colours are to the effect and the mood of the painting, which I personally do not find in the least bit harrowing.

Colour is also the key to the scene of the altarpiece on the left—pinks, browns, grey–blue and green–blue set against gold—but the background buildings are a little more sophisticated than in the other scene at Alexandria.

We see the city of Assisi under attack from marauding Saracens, who are trying to break into the convent that houses St Clare and six other nuns who are wearing the plain habit of her order (the ‘poor Clares’).

The ‘pioneer corps’ are being hurled from the roof, with their pickaxes flying, as St Clare holds up the monstrance containing the consecrated wafers of the Host.

Enchanting.

We shall see painted narratives which are similar in scale and colour in the next lecture, but in order to understand why they will, quite emphatically, not be similar in figure-style, composition and expressive power, we must go back to the Cathedral of the Virgin.

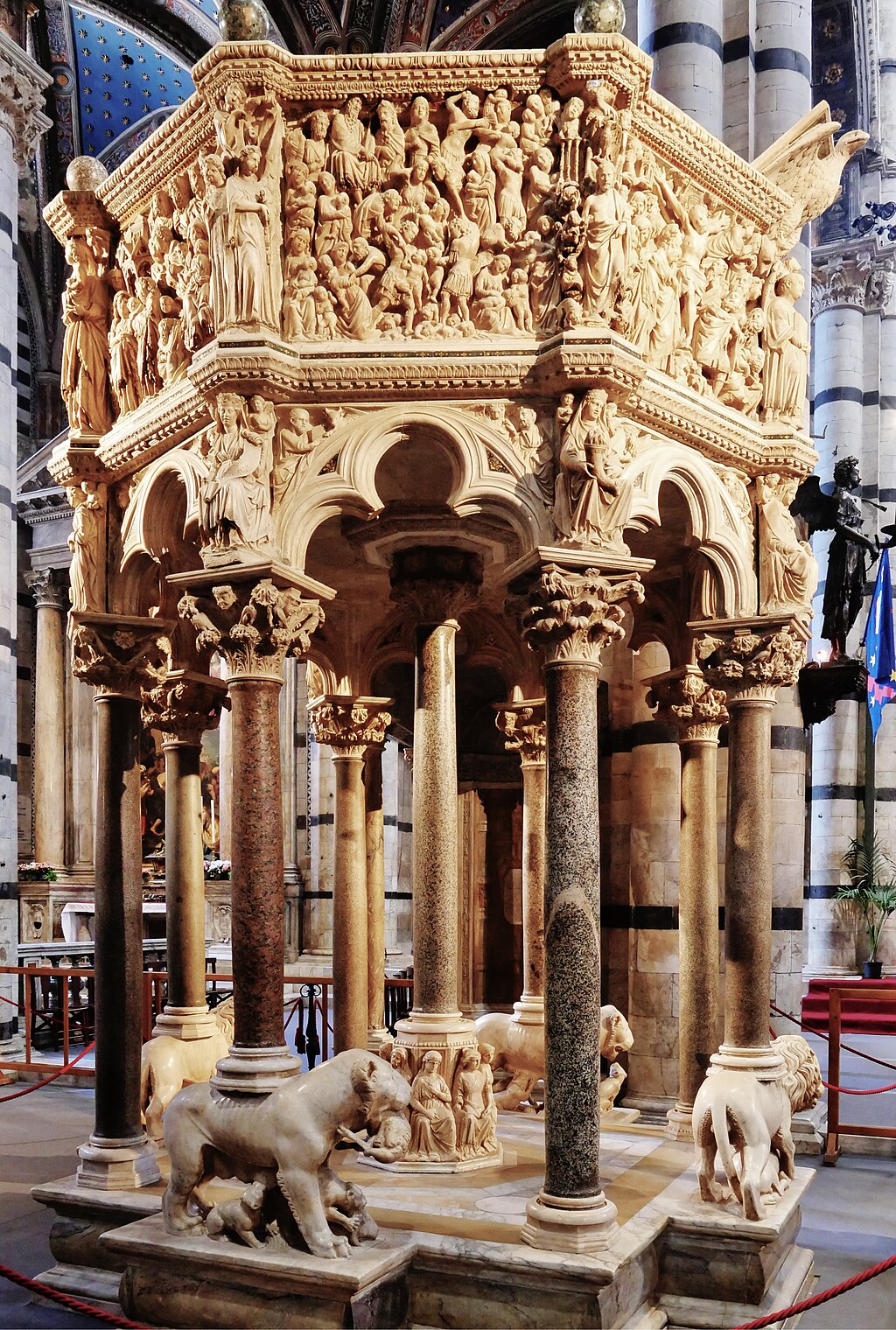

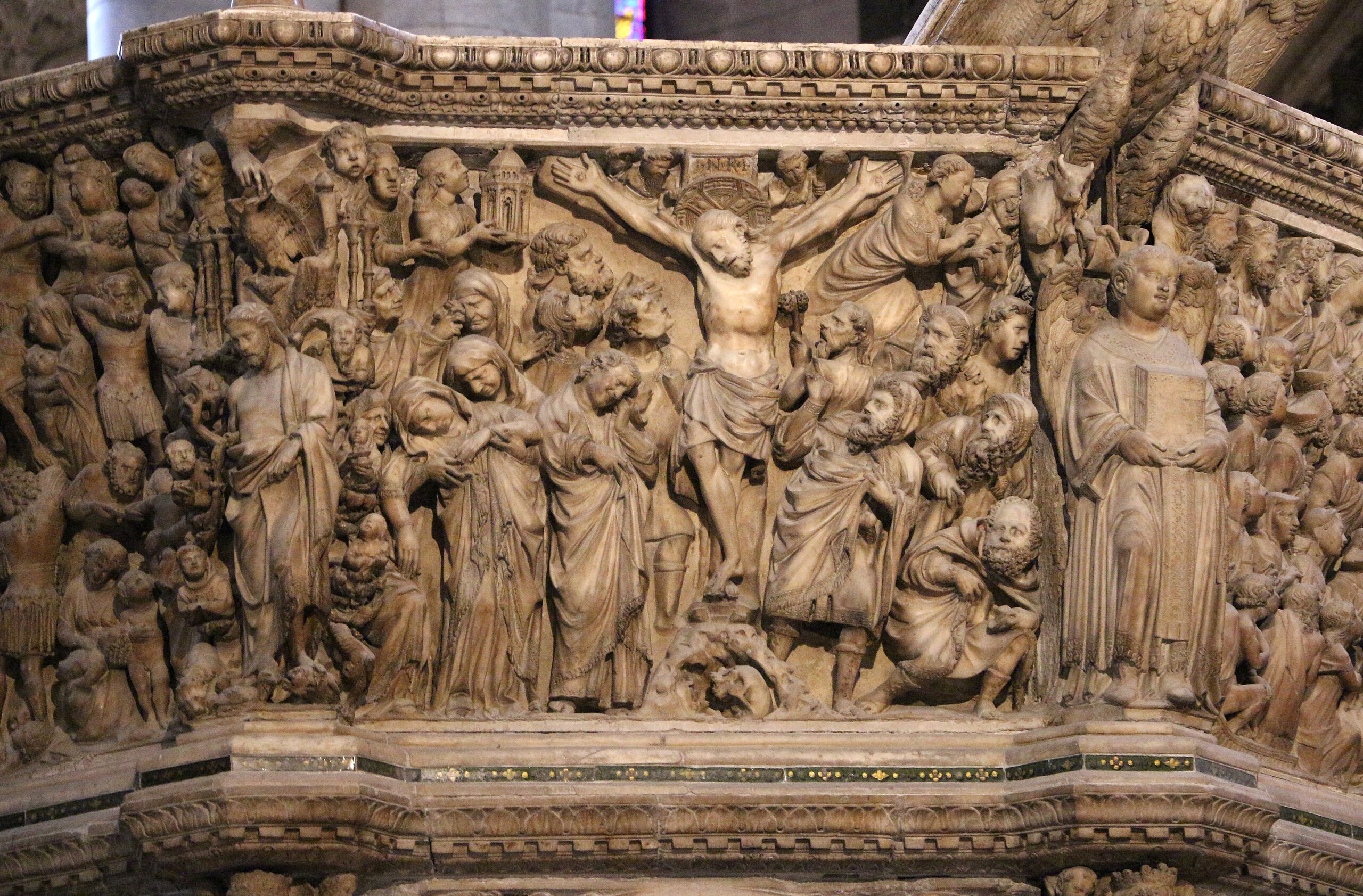

If you walk the length of the long nave, between its almost oppressively black and white banded columns, and come to the crossing, you will find a tall, octagonal pulpit.

What brings us to this pulpit are the panels on seven of the eight sides.

Each is about three feet high, and each is packed with relief sculptures, executed by a workshop headed by the leading sculptor at work in central Italy in the second half of the 1260s.

These reliefs made available to all successive Sienese painters, in a convenient public place, and on a scale which they could easily assimilate, the most advanced treatment of the human figure then available anywhere in Italy.

The sculptor and designer in chief was called Nicholas from Pisa: Nicola Pisano.

His assistants included Arnolfo di Cambio and his own son, Giovanni; and they completed the pulpit in just three years, between 1265 and 1268.

I am not going to talk about the pulpit as an ‘architectural whole’, nor about the very ambitious iconographical scheme through which all the human figures who are not in the narratives are linked to the story through prefiguration or fulfilment.

But you must bear in mind, as we skim through photographs of the densely packed little figures in the seven narrative panels, that they are placed well above your heads, and carved in quite deep relief, with the result that they change in appearance and in their relationships to each other every time you move your head or shift your position in the cathedral.

The statue on the left, standing outside the first panel, shows Mary receiving the Annunciation, while the panel itself contains three (or, arguably, four) further scenes associated with the Birth of Jesus.

In the sky, five angels announce the Good Tidings to the two shepherds, who gaze up ‘in wonder and mighty dread’ from the task of ‘watching their flocks by night’, the flocks being represented in the well-kempt sheep in the foreground, one of whom scratches its head like a dog.

Reclining in the very centre, Mary turns to look at the two crouching midwives who are bathing the very lusty new born babe in the foreground, who will soon be wrapped in swaddling clothes and placed in the crib for the ox and the ass to worship.

Perhaps the most memorable detail in the first panel comes in an earlier scene, to the left, where, beneath a skeletal church, we see the ‘Visitation’—that is, the meeting between Mary, just pregnant with the Word Incarnate, and her much, much older cousin, Elizabeth, who is already heavily pregnant with the future John the Baptist, after many years of barrenness.

It is a profound study of youth and of age, and of a ‘wild surmise’.

The next two panels are linked by the story of the Three Wise Men.

In the earlier scene, you can just make out the cavalcade (top left), as it sets out from a regal palace in the East (identified as the ‘Orient’ by some ‘oriental’ palms).

The caravanserai journeys across the whole of the foreground, with the kings (young, middle aged and old), on horses, accompanied by two aristocratic greyhounds, riding behind two Ethiopes, who are mounted on diminutive camels, and a servant, who is halting the pack horses as they arrive at the end of the journey. (All the animals are carved with astonishing virtuosity).

Above, Mary holds Jesus in her lap as he receives the homage and gifts of the Three Kings: the older man, kneeling awkwardly, the middle aged man, most ‘involved’ and adoring, and the young man waiting his turn to offer his gift of myrrh.

A much more elaborate building in the next scene—shown simultaneously from outside, above, and inside—represents the Temple in Jerusalem, where Joseph and Mary are presenting Jesus to old Simeon, and the baby is recoiling (as he so often does in the pictorial tradition) from the old man in some alarm.

Contemporaneously, king Herod ponders on what the Wise Men have told him about the birth of ‘a ruler who will govern the people of Israel’; and he resolves, in consultation with his bearded advisors, ‘to kill all the male children in Bethlehem and in all that region who were two years old or under’.

Luckily, however, a boy-faced angel of the Lord appears to Joseph (crouching and cocooned in his cloak), warning him of Herod’s intentions; and he places Mary, holding Jesus, side-saddle on a donkey, and leads them off to safety in Egypt.

Jesus escaped his murderers on that occasion, but his time would come, as we see in the next scene, where, he hangs from the Y-shaped cross, his head sunk in pain and exhaustion, flanked by his swooning mother (supported by the other two Marys), while his disciple John presses his hand against his cheek in the ritual gesture of grief.

Once again, there is a tiny building, placed top left; but this time it is the model of a hexagonal baptistry, carried by an angel, which symbolises the victorious Christian Church.

At the same height on the right, another angel is driving away a figure representing Synagogue, who is ‘routed’, together with the crouching, huddled Jews in the foreground, because although the Christ on the Cross is of the type called patiens, he is nevertheless triumphans.

The paired details almost defy comment.

They confirm that Nicola’s pulpit offers some of the most expressive ‘narratives in stone’ to be found anywhere in the history of European Art. All this in Siena, in the 1260s.

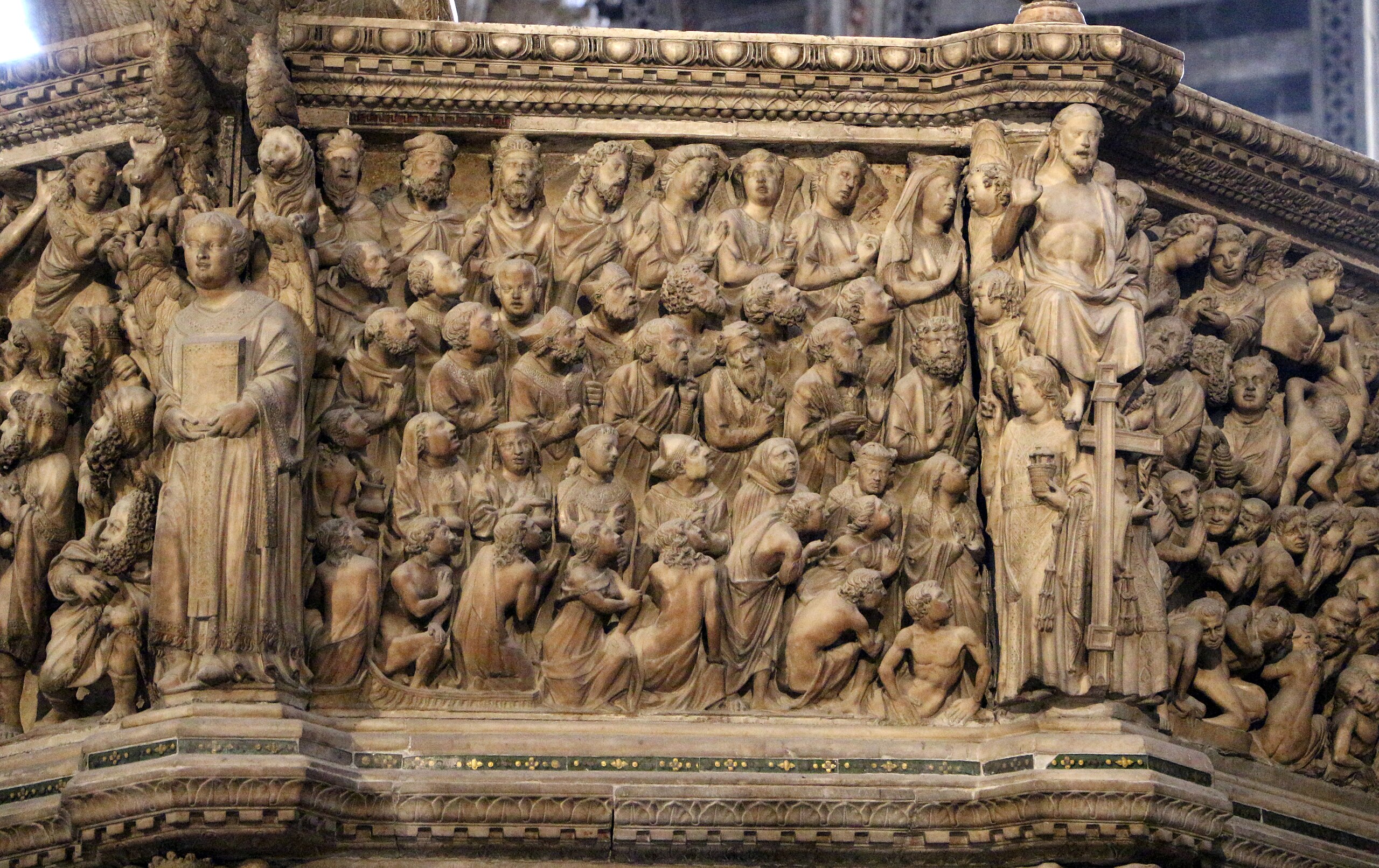

We move briefly to the last two panels, which absolutely demand to be displayed as a pair.

From the Crucifixion, at the midpoint of human history, we leap forward to the end of history—to the Last Judgement.

Nicola had the happy idea of representing Christ as Judge, as a larger statue, between the panels, such that the Chosen are on his right, and the Damned are on his left.

It would be tempting to concentrate on the scene of Damnation, the seventh panel, which is every bit as animated and varied as the Slaughter of the Innocents.

(You will find an initial process of assessment and debate between the angels (top left) and the newly risen bodies below them; then vain entreaty, exemplified in the angel and the monk (left foreground); but in the end, the sinners are hurled down in their nakedness, to be clawed by Lucifer, seated on his throne, or bitten by the devil in the foreground.)

Like Dante, however, I should like our story to have a ‘happy ending’, and so I will close by focussing on just two details from the sixth panel—the Joys of Paradise.

Concentrate, first, on the heads of the Blessed, rising from their graves in the foreground, before taking their seats in Heaven.

They are arranged in three rows: first women, then men (with two crowned heads among them), and the patriarchs of the Old Testament at the top.

The patriarchs look calmly down at us—they always knew they would be saved—while the others, with one exception, gaze up at the Son of Man in worship, and in some relief, splendidly varied in age and in type, and marvellously characterised by gesture, costume and expression.

At the very top right, you see the Virgin Mary again, her hands joined in supplication, interceding with her Son on behalf of all Mankind in general—but, in particular, you may imagine, on behalf of the city which had placed itself under her protection—

Siena, the city of the Virgin.