Simone Martini: The Life of St Martin

The previous lecture focused on the twenty-six panels of Duccio’s Passion Cycle, painted between 1308 and 1311 for the high altar of the Cathedral in Siena, presenting them as a worthy climax to developments in Italian art in the previous thirty years.

In this lecture I shall move forward only a few years, to a date most likely between 1316 and 1318 (but in any case not later than 1325), to look at a narrative devoted to the life of St Martin painted by the greatest ‘Sienese Storyteller’ of the generation following Duccio—Simone Martini.

The cycle on which this lecture focuses has only ten scenes, which allows plenty of time to set them in the context of the early career of Simone Martini, and indeed, plenty of scope to say something about the very famous, very non-Sienese frescos in the upper church at Assisi, which date from the late 1290s and tell the story of the life of St Francis.

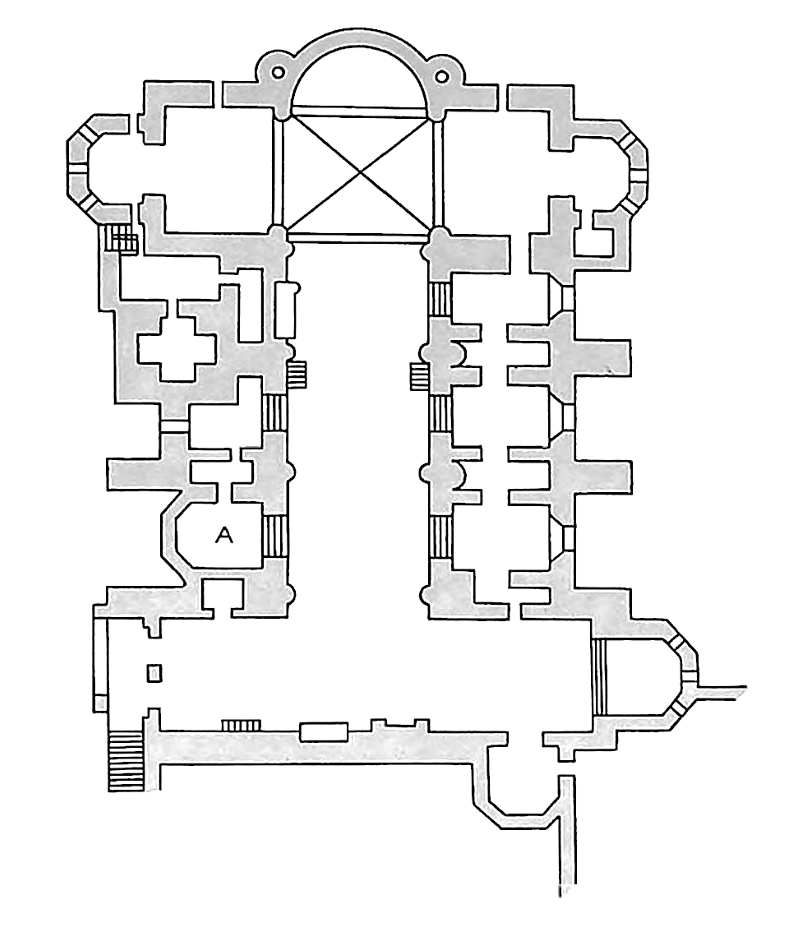

There are two main reasons for exploring the relationship between the two saints and the two fresco cycles. First, our frescos are actually in the same building as the others. They are to be found in a chapel in the lower Church at Assisi; and hence it was possible for Simone to study the earlier cycle every day during the two summer seasons he was engaged on his work. And second, the choice of scenes from the life of St Martin was deliberately shaped in order to emphasise parallels with St Francis.

I remind you that the ‘double’ churches constituted the mother church of the Order of Brothers Minor and that they were built over Francis’s tomb in the very town of his birth.

Martin was retrospectively ‘adopted’ by the Franciscans because they came to regard him as a spiritual ancestor of their founder.

These facts are so important that I have in fact decided to devote a few pages to the historical Francis and to the striking evolution in the ways his mission had been conceived and represented in the first hundred years after his death—an evolution that can tell us great deal about the history of the Franciscan order down to the year 1315 when Simone began to paint.

Francis, whose personality was movingly interpreted by Cimabue in the 1280s, was born in Assisi, in the very centre of Italy, in the year 1182.

He was the son of a merchant; and several of the stories about his early life portray him as a comfortably well-off young man about town. But he came to feel that Jesus had personally called him to his service, and he decided to follow, to the letter, Jesus’s instructions to his first disciples.

He became in effect a missionary to his own society, dedicated to absolute poverty, and preaching not only love for all men but love for the whole of God’s creation—as we know from the story of his preaching to the birds, and from his own prose-poem, the ‘Canticle of Brother Sun’, otherwise known as ‘Praises of Creatures’, from which I quote these typical lines. (You will easily pick out the dozen key words: ‘All creatures, Brother Sun, day, illuminate, beautiful, radiant, splendour, Sister Water, useful, humble, precious and chaste’).

Laudato sie, mi’ Signore, cum tucte le tue creature,

spetialmente messor lo frate sole,

lo qual’è iorno, et allumini noi per lui.

Et ellu è bellu e radiante cum grande splendore:

de te, Altissimo, porta significatione.…

Laudato si’, mi’ Signore, per sor’aqua,

la quale è multo utile et humile et pretiosa et casta.

Francis founded an order, modestly called ‘Lesser Brothers’ (frati minori); and after his death in 1226, his followers multiplied and spread with extraordinary rapidity in the fast growing cities of Tuscany and northern Italy.

Before long, they were building enormous new churches, like Santa Croce in Florence, which had colossal naves to accommodate their huge congregations.

So much by way of recapitulation of the bare facts. Now, let us examine some images of the new saint.

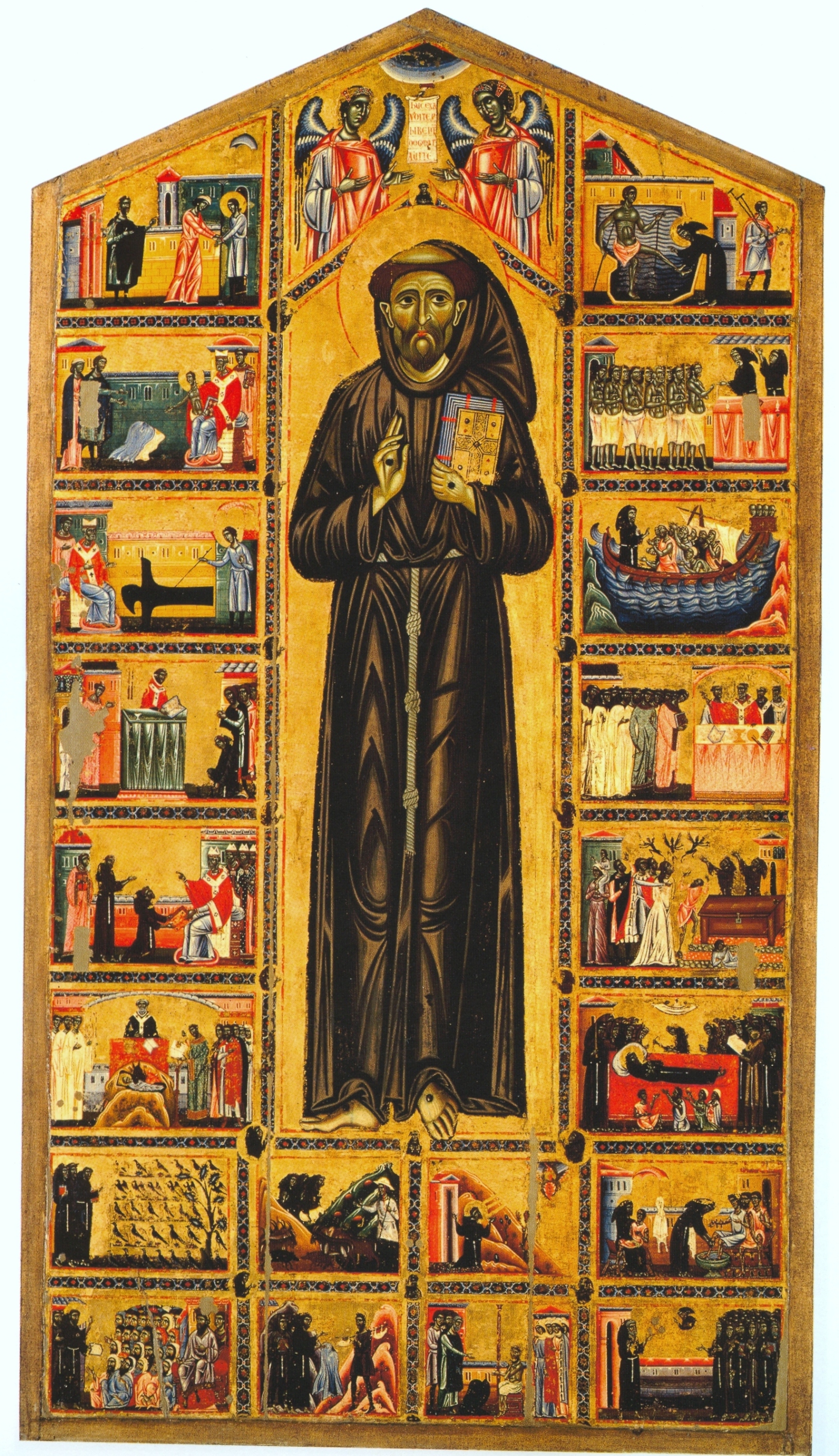

There are several early altarpieces on which St Francis is represented, of which the most significant and best preserved is the one formerly attributed to Coppo da Marcovaldo. This dates from the 1260s and is still to be found in its proper place over the altar of a chapel in Santa Croce in Florence.

It offers an almost perfect illustration of what early nineteenth-century connoisseurs meant when they spoke about Italian ‘primitives’.

In the main figure of St Francis, for example, you have only to look at the cowl of his hood, or at the old-fashioned stylisation of the folds in drapery, evident in the pattern of chevrons imposed on the Saint’s legs.

In the tiny panel to the right of the main figure, showing a storm at sea, notice in particular the gold ground and the deep saturated colours, the huge eyes, the highly stylised rocks and waves, and the absolute indifference to the relative size of men and ships.

Today, we would not want to call this ‘primitive’. The turbulence of the sea, the broken mast, the terror and supplication of the crew and the calm benediction of the saint could not be better conveyed. This is ‘icon’ painting at its most sophisticated.

But the main point I want to make here is that paintings in this conservative style are entirely faithful to the spirit of Francis himself, as we come to know him from his writings and from the earliest biographies.

In the 1260s and 1270s, however, there came a struggle for control of the Franciscan Order between the radical wing, known as the ‘Spirituals’, who wanted to observe the letter of Francis’s teaching, and the more moderate, practical and conservative wing, known as the ‘Conventuals’.

The Conventuals won, and to consolidate their position they called in all the existing biographies of the founder with the intention of destroying them and replacing them with a new official life, written by St Bonaventure, the General of the Order—a biography which lays great stress on the subordination of Francis to the authority of the Pope.

And when the decoration of the new upper church at Assisi was put in hand during the 1280s, the finance was authorised from Rome; and the artists who were called in were not nameless provincials, but some of the most advanced and monumental painters of the day, who were closely associated with the art of the metropolis.

The situation of the two churches in Assisi, one on top of the other, can be clearly seen in the photograph.

The lower church had been built in the Romanesque style immediately over the Saint’s tomb.

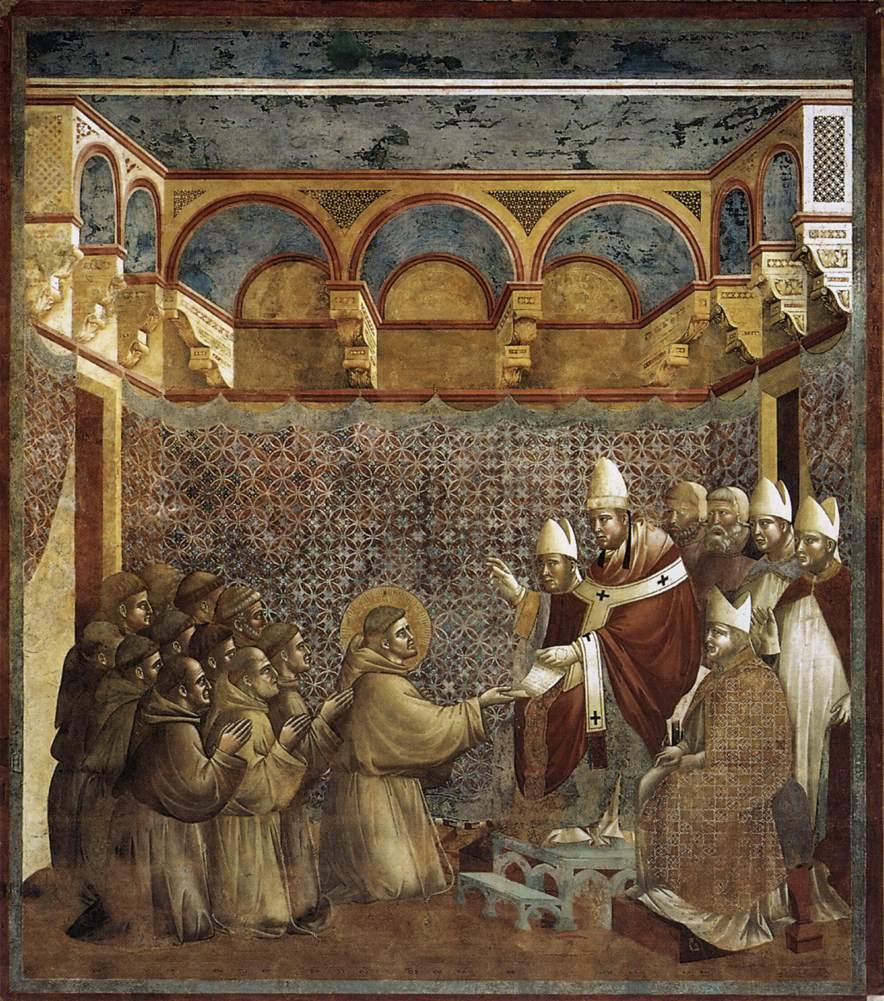

The transepts and the nave of the upper church were clearly specifically designed to accommodate vast areas of well-lit frescos, with the place of honour being reserved not for the biblical narratives in the higher zones, but for 28 scenes from the life of Francis, as narrated by Bonaventure.

These run right round the nave, starting just above head-level, and are hence clearly visible to every member of the congregation, however vast the throng of pilgrims in the church.

Scholars all now agree that the frescos were executed in the 1290s, but it is important to bear in mind that there is no firm documentary evidence; which is why the guide books, and most native Italian art historians, are able to attribute some of the frescos in the Francis Cycle to the youthful Giotto, while many Anglo-Saxon experts seem to be sure that none of the frescos are by him (although his youthful hand is detected in one of the Old Testament narratives higher up the wall).

Whoever the artists were, the St Francis Cycle constitutes an absolutely amazing advance in the use of a two-dimensional surface to convey the appearance of a three-dimensional world, thanks to a combination of several factors which combine to create this new realism.

The first factor is perhaps no more than the artist’s closer observation of objects in the everyday world, coupled with a desire to make them look real (it will lead to some astonishing examples of trompe l’œil painting in the next century).

The second is the deliberate foreshortening of complex objects, drawn from unfamiliar angles, such that the lines defining the legs of a table, for example, will only be recognisable as such, if the mind calls into existence an imaginary space for them to stand in.

The third is the controlled use of perspective in the representation of architecture, with the intention of creating something like a shallow stage-set to contain these foreshortened, volumetric bodies.

And the last important factor is the artists’ increasingly confident control of relief modelling, that is, the differentiation of planes by tone (lighter and darker applications of the same colour) so that the viewer will assume that the brighter surfaces are reflecting the direct fall of light from one specific source, while the darker surfaces will seem to lie in a shadow cast by an object that must therefore be opaque and three-dimensional.

All this will become clear if we take a quick look at four of the frescos in the Life of St Francis in which the combination of these factors is particularly striking.

The episode illustrated in the very first scene of the story took place in the town of Assisi itself, only a few hundred yards from the church; and the fresco reproduces, with quite astonishing attention to detail, the tower of the Palazzo del Comune (which then lacked its upper storey) and the façade of a Roman temple which had been transformed into a church.

Never mind that there are five columns in the picture instead of six in the town-square—such a degree of realism was totally without precedent.

This street scene is an example of architecture used principally as a ‘backdrop’, but the next two examples show how perspective came to be used in order to suggest depth, that is, in order to create an imagined space able to ‘contain’ the human actors.

In the next example, the foreshortening of the balcony and its supporting soffits generates just enough space to enable the Saint to stand behind the table.

And if you examine the detail showing the edge of the table, you will see both a masterly piece of three-dimensional drawing in the ‘foot’ of the table, and an assured rendering of the fall of light on the different planes in the folds of the tablecloth, which give a very strong sense of relief (rilievo).

It is important to remember, however, that the buildings scarcely seem big enough to accommodate the human beings, and that the artists are still adopting more than one viewpoint in their empirical use of perspective.

The ceiling of a room, or the vault of a church, may be shown as they might appear from a position near the floor, whereas tables, beds and altars in the same painting may be drawn as though they were viewed from near the ceiling.

It would be another 150 years before Alberti taught artists to adopt a single scale for all objects within a painting and to project every part of a scene from a single viewing point. And it is the sometimes uneasy blend of incipient ‘realism’ with the traditions of ‘icon painting’ which gives these frescos a power to move us that will often be lacking when the technical revolution is complete.

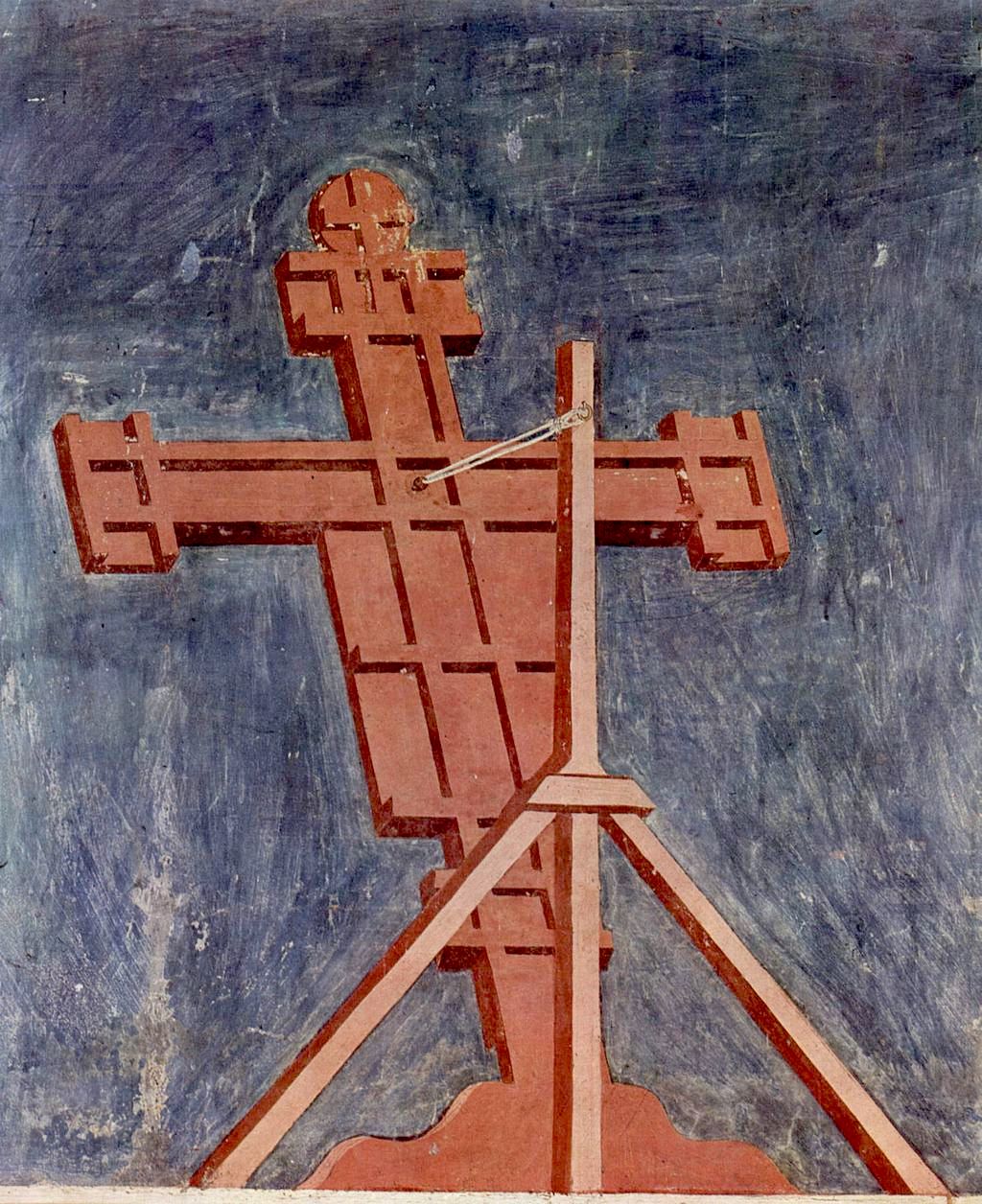

For a more complex example of the creation of space and the filling of that space with solid objects, it is enough to look at the throng of figures, standing one behind the other in the chancel of a church.

Admire, too, the very convincing representation of the tall ciborium on the right (faithfully copied from a recent work by Arnolfo di Cambio in Rome); and notice the subtle suggestion of a much deeper space in the nave of the church.

The nave exists only in our imagination because it is blocked out by the rood screen; but we are compelled to imagine it by the foreshortening of the back of the pulpit (with its candles in place), and, above all, by the rear of the red crucifix, which is leaning away from us to display the unseen figure of Christ on its other face to the unseen congregation.

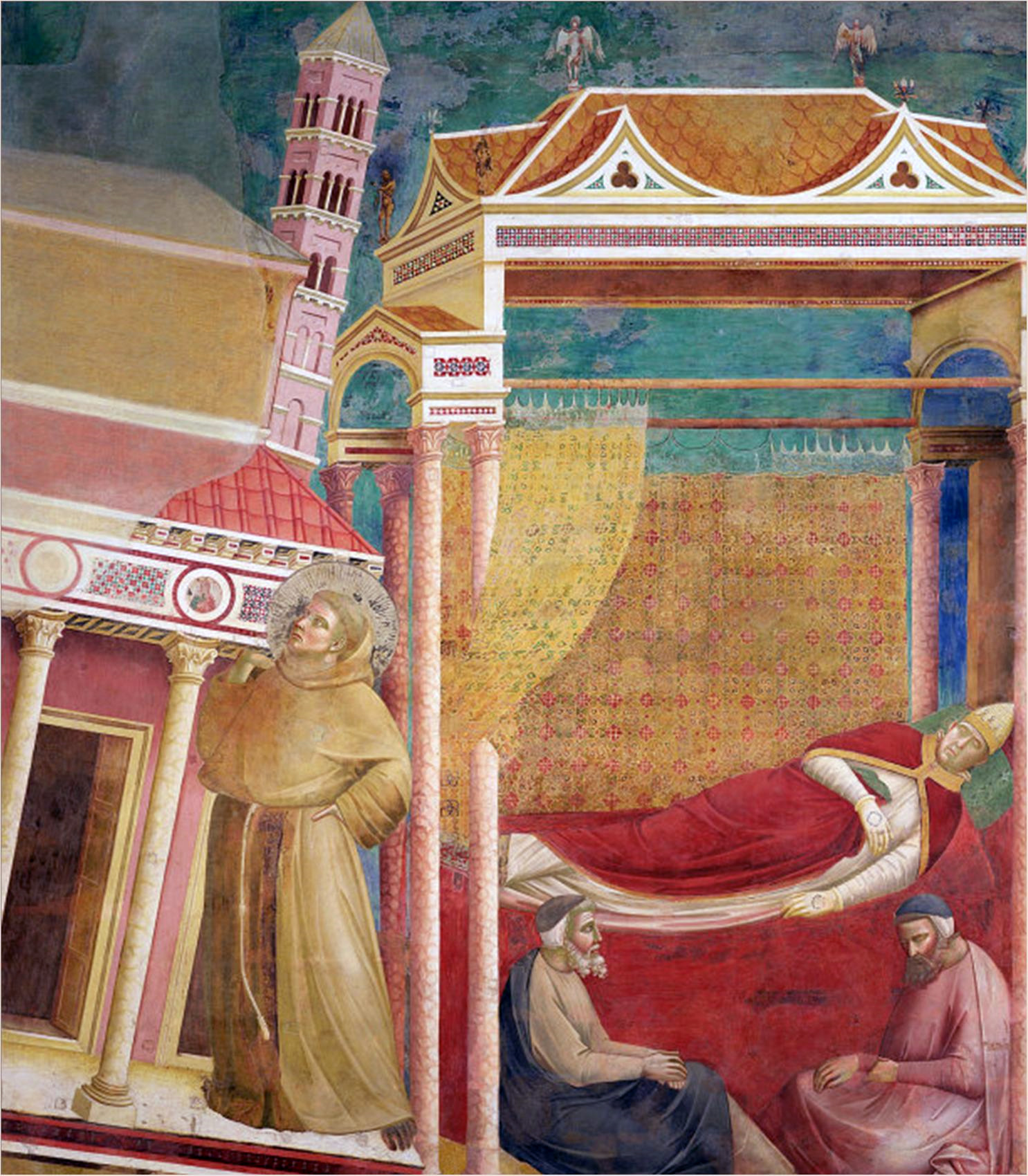

For a final example—this time of a human body—let us look at the fresco where the Pope is shown lying in his magnificent, ‘four-poster’ bed, having a prophetic dream that Francis will support the collapsing church.

In his dream, a young, heroic Francis—with a barrel of a chest, a tree-trunk of a leg, and his right hand flattened by the weight of the collapsing church—is bracing himself with his left hand placed on his hip; and this is the gesture which causes the form-defining folds across his chest.

We can also note, in the closer detail, the use of darker and lighter tones to define the different planes of his face, neck and cheek bone, the bulge on his jaw, and the hint of a Cary Grant chin.

This brief anthology must suffice as a reminder of the technical developments in the art of painting that had been gathering momentum while Simone Martini was still an apprentice.

(Remember that these frescos are especially relevant to our subject, because Simone could have looked at every brush stroke every day for at least six months, while he was working on the Life of Saint Martin, given that our cycle is to be found in the earlier church underneath.)

Before we turn to The Life of St Martin, let me say a few words about Simone’s career and show you some of his other paintings so that you can get your eye in.

He was a citizen of Siena, probably born in the 1280s.

We know nothing certain about him until 1315, by which time he was an assured master in his thirties, who was called in to paint a huge image of the Virgin in Majesty, fully 32 feet across—on one wall of the Council Chamber of the Commune in Siena.

We really ought to make a close comparison of this monumental work with its model, the Maestà by Duccio, finished in 1311. And we must at least pause to glance at the figure of Mary in the centre.

She is so amazingly unlike Duccio’s Virgin: so ‘regal’, so ‘courtly’ in her slim proportions, in the design of her crown and in the richness of the cloth-of-gold she is wearing instead of the plain blue mantle of tradition.

The complex folds of her robe across the foreground seem to have been painstakingly arranged for a fashion photograph in Vogue.

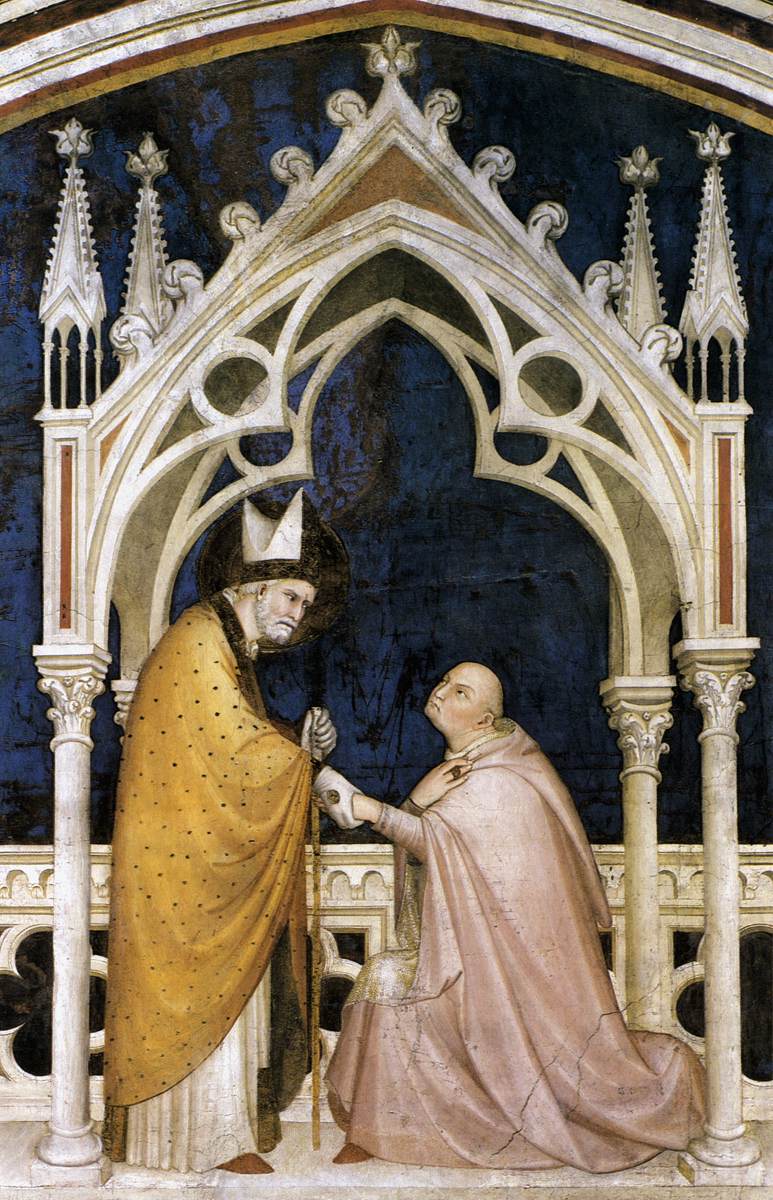

By 1317, Simone was famous enough to be called to Naples to paint this superb altarpiece.

It shows Prince Louis of Anjou—who became a Franciscan in 1296, and had become Bishop of Toulouse at the time of his death a year later (hence the habit, and the coat, and mitre).

He is receiving the crown of sainthood from two diminutive angels at the top. (He was canonised in that very year, 1317.)

Louis, in turn, places an earthly crown on the head of his brother, Robert, who had become King of Southern Italy in 1309, and was to become a patron to Boccaccio and Petrarch.

(It is not very revealing, considered as a portrait; but look at the painting of his tunic and, above all, at the way the broad golden band of his pallium is folded over and tucked into his belt.)

Again, I would love to tell you a a great deal more about this picture, but must limit myself to a swift look at the predella panels at the bottom of the altarpiece, which show us, for the first time, Simone in his role as a storyteller, in five scenes from the life of St Louis.

These are particularly interesting from the point of view of technique, because the perspective of the architecture in all five scenes presupposes a single, common viewpoint in the centre of the central scene.

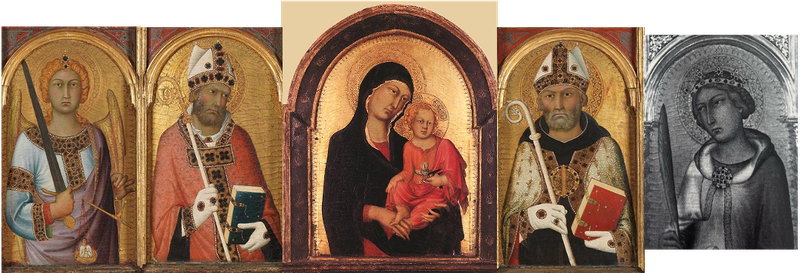

Two years later, in 1319, Simone painted a huge polyptych for the Dominicans at Pisa, showing the Virgin flanked by many saints, who are all turning inwards at the appropriate angle to face towards the centre.

Two years later again, Simone completed a similar altarpiece, somewhat less grand, for the Augustinian canons at nearby San Gimignano.

Its components have long been dismantled and dispersed but the photomontage uses the evidence of pose and directed glance to shows how the five panels must have been arranged originally.

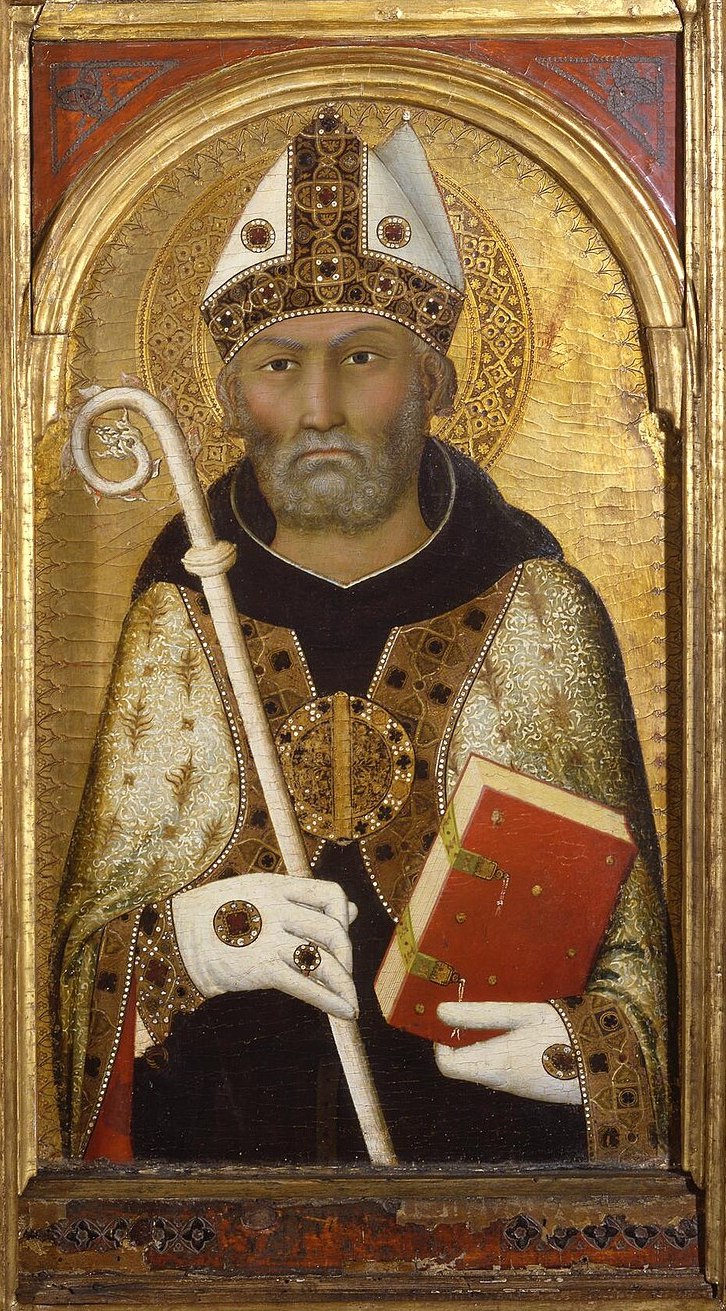

Three of these panels are now in the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge where they are presented and framed as you see them here, placed low on the wall, enabling you to enjoy the delicacy of Simone’s touch and tone in the imagined portraits of the two bishops (St Geminianus is the local saint, and St Augustine is the patron saint of the community).

Look closely at Augustine’s eyes in the detail, and at the down-turned corners of his mouth, and his curly beard under the mitre, because the Bishop of Hippo here closely resembles the Bishop of Milan (St Ambrose) and the Bishop of Tours (St Martin) in the final frescos of the narrative in the Lower Church at Assisi.

I shall not describe Simone’s later career—in the 1320s and 1330s (which, on any dating, would come after our cycle)—but I do want to mention that in 1340, Simone was summoned to work at the papal court, which had abandoned Rome and established itself in France, at Avignon.

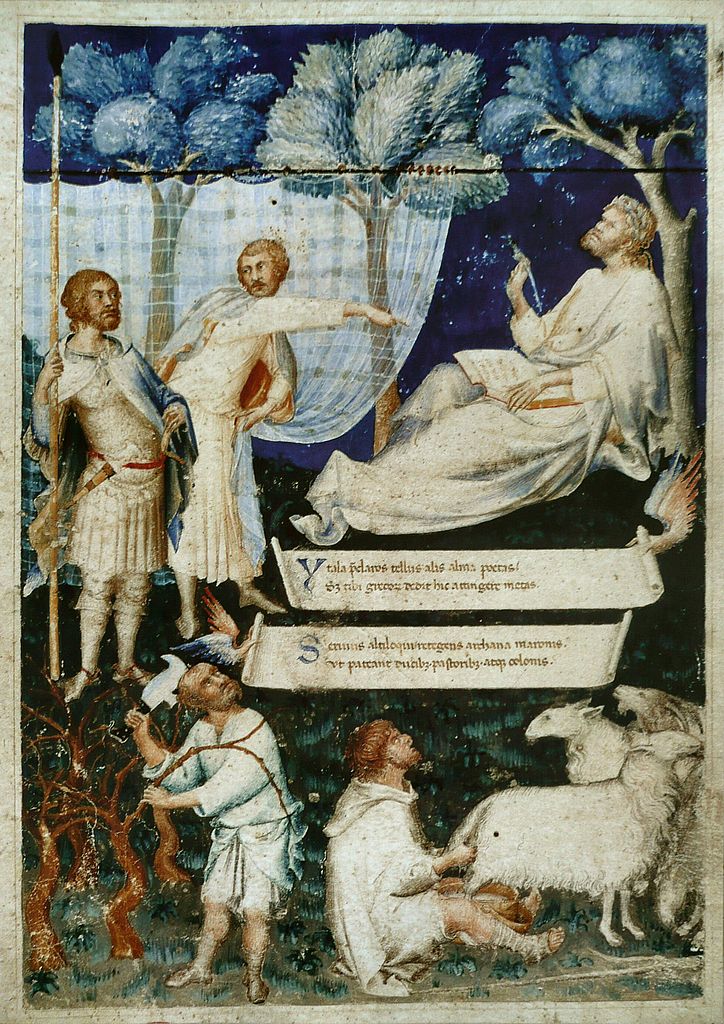

Simone lived there for four years (before his death in 1344). He became a friend of the poet, Petrarch; and he painted two miniatures at the request of his new friend. The commissions are the equivalent of Nicholas Hilliard limning the Dark Lady for Shakespeare, and the images are therefore ‘worth the detour’ (in the hallowed phrase of the Michelin Guides).

The first is only about 11 inches high and is to be found in Petrarch’s own copy of the commentary by Servius to the works of Virgil.

It shows Servius drawing back a curtain or ‘veil’, in order to ‘re-veal’ the poet and his meaning; and it personifies the three main works of Virgil in the shepherd of the Eclogues in the right foreground, next to the peasant farmer of the Georgics, with his machette or pruning knife, and the knightly hero of the Aeneid, with his sword and long lance, standing beside Servius.

The other miniature was nothing less than a portrait of Petrarch’s beloved, Laura, which, alas, has not come down to us. What we do have, though, are the two sonnets which Petrarch wrote as an answering gift in order to thank ‘his Simon’.

I give you the first, preceded by my translation (which you may care to think of as like the engraving of a painting—the absence of rhyme being like the renunciation of colour). It is neither literal nor free; and if you read the English aloud, you should find it gives some idea of the flow of the original).

And I place alongside the poem a detail from a fresco in the Lower Church at Assisi, showing how Simone had visualised St Clare.

Had Polyclitus gazed a thousand years,

in contest with his rivals in that art,

their eyes would still have failed to apprehend

the beauty that has overpowered my heart.

But Simon must have been in Paradise

(from where this gentle lady made her way),

and there he saw her, taking with his brush

a faithful record of her lovely face.

The work was one of those that may be limn’d

in heaven, not here among our kind below,

where flesh and blood enfold and veil the soul.

Nor could he now repeat his kindly deed,

after descending to the world of change,

and after his eyes had known mortality.

Per mirar Policleto a prova fiso,

con gli altri ch’ ebber fama di quell’arte,

mill’ anni, non vedrian la minor parte

della beltà che m’ave il cor conquiso;

ma certo il mio Simon fu in paradiso,

onde questa gentil Donna si parte;

ivi la vide e la ritrasse in carte,

per far fede qua giù del suo bel viso.

L’opra fu ben di quelle che nel cielo

si ponno imaginar, non qui tra noi,

ove le membra fanno a l’alma velo;

cortesia fe’, né la potea far poi

che fu disceso a provar caldo e gelo,

e del mortal sentiron gli occhi suoi.

I have now given you not one, but two introductions—the first dealing with St Francis and the developments in Italian painting between 1250 and 1300, the other with the career of Simone Martini—and you should be reasonably well prepared to enjoy the Life of Saint Martin, as painted by Simone at some time between 1315 and 1325.

Back to the town of Assisi, then, and to the ‘double church’, which rises over the tomb of Saint Francis.

Ignoring the upper church, we must go in through the rounded arch at street level, and turn left into the nave of the earlier, Romanesque church, which is as low and as dark as the other is high and full of daylight.

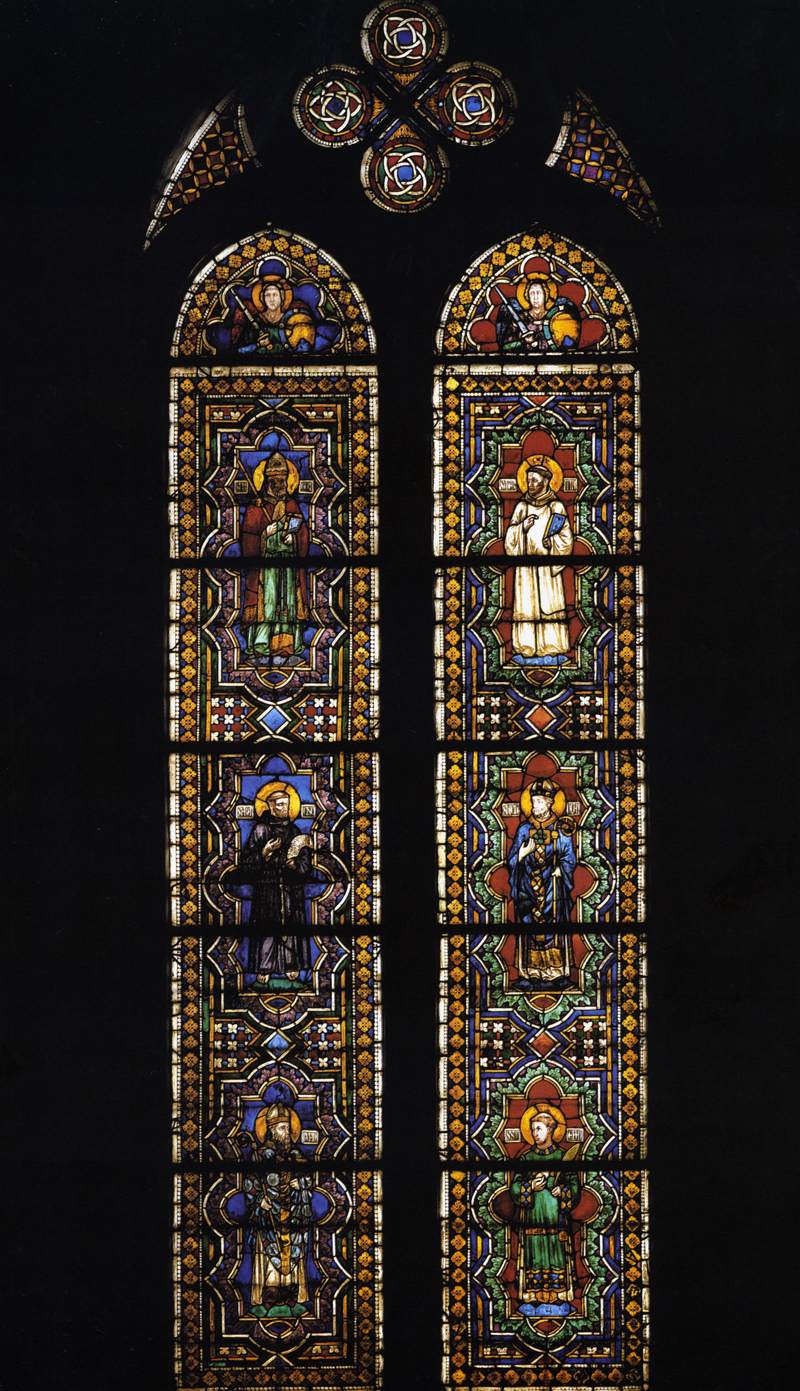

The Chapel is crammed with images of saints other than Saint Martin, which surround the entry arch and fill the windows, and include many examples of Simone painting at the very top of his form. But we may ignore all but one of these ancillary images and concentrate, just for a moment, on the fresco on the inner face of the entry arch, where we see the donor of our narrative frescos, kneeling before the saint to whom the chapel is dedicated.

There is a lot more I could tell you about Gentile, and about the decorative scheme in its totality, but let us move straight to the ten scenes which tell the story of Saint Martin.

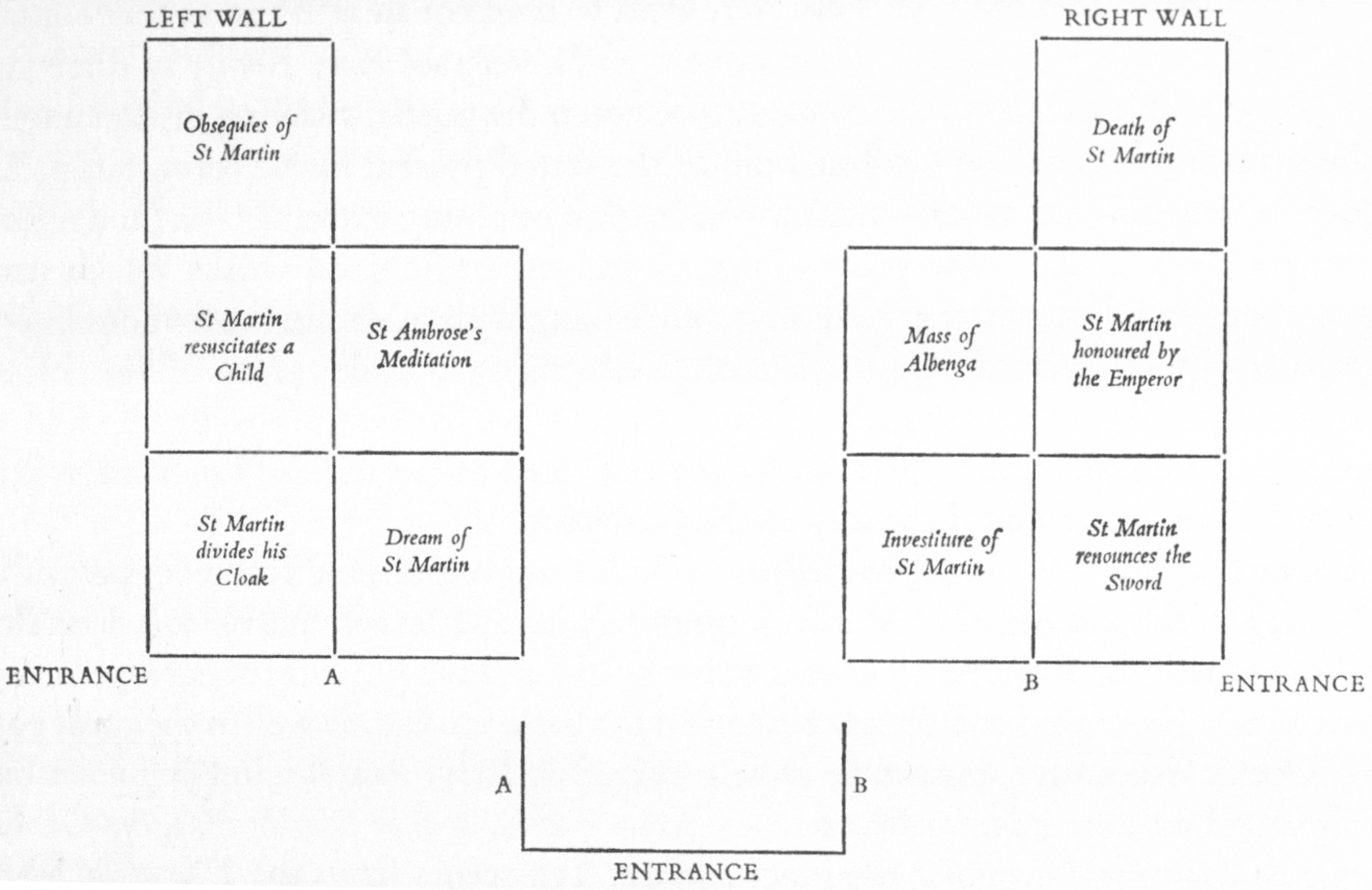

As you see in the diagram, the frescos are laid out in three tiers, facing each other, with two of them curving over to touch each other at the top of the vault above your head.

The general appearance of the eight scenes in the lower registers is nicely conveyed in the photographs, where you must imagine the bottom edges as being about ten feet above the ground.

Most unusually, the story unfolds from bottom to top (for visual reasons that will become clear later). So we will begin our reading with the lowest pair on the left wall, each scene being about eight feet high.

These two scenes (like the next pair, and like the first frescos of Francis’s life in the upper church) show Martin as he was before he discovered his vocation.

The best way to find out what is happening is to pick up a very influential compilation of saints’ lives, the Golden Legend (dating from c. 1260) and turn to the entry for November 11, which is the day of Martinmas. The story illustrated in the first scene runs as follows:

‘Martin was born in Hungary, but was reared at Pavia in Italy, where his father was a tribune of soldiers. He himself served in the army under the Emperors Constantine and Julian, but against his will.

‘Martin was inspired by God from infancy; and when he was twelve years of age he fled to the church and asked to be received as a catechumen. He would have become hermit had not the weakness of his body forbidden it. But, since the Caesars had decreed that the sons of the veterans should take their fathers’ places in the Army, Martin was compelled to take arms when he reached the age of fifteen. He took with him only one serving man; and Martin often waited on him and drew off his boots and polished them.

‘It chanced one winter day that Martin was passing through the gate of Amiens, and came upon an almost naked beggar. The poor man had received no alms that day, and Martin considered that he was reserved to himself. So, he drew his sword, divided his cloak in two parts, gave one part to the beggar, and wrapped himself in the other.’

The story is completed in the second scene:

‘On the following night in a vision, he saw Christ wearing the part of his cloak with which he had covered the beggar; and he heard Christ saying to the angels who surrounded him: “Martin, although still a catechumen, has clothed me with this garment!” And so the future saint had himself baptised’.

The best way to approach the scene of the gift in the first fresco is through a comparison with Simone’s original thoughts, which were revealed when the fresco was detached from the rough plaster underneath to show the sinopia or ‘underdrawing’.

Originally, Simone had intended to place buildings to the right to balance the city gate on the left; the beggar was imploring alms or receiving the unexpected gift more passionately, with both arms outstretched; and the helmeted Saint, boldly foreshortened, was looking down at the cutting edge of his sword.

In the final version, however, Martin is bare-headed and young, with golden hair like an angel; and he twists round in his saddle in order to accompany the gift with the all important gaze.

If you now glance back at the scene of the subsequent dream, you will notice how the architecture presupposes a viewing point which lies between the two pictures (it is this whole second scene which now balances the city gate of Amiens in the first).

These details from the second scene nicely illustrate nicely the points I was making earlier about the lack of a common scale and about multiple viewpoints.

Christ and the angels are very cramped.

The bed is viewed as if from above, to show off the coloured pattern of the quilt and the exact position of Martin’s body and his feet.

But the close-up of Martin’s head is a perfect example of the key components in Simone’s art.

There is a debt to tradition in the halo, totally unforeshortened, richly tooled, covered in gold leaf. There is human insight in the childlike gesture of the saint’s hand at his throat. And there is superb skill in the rendering of the curve of the pillow and the folds of the sheet, which is well tucked in to keep out the drafts.

The next pair of frescos are side by side on the opposite wall, nine to ten feet above the ground, and each about eight feet high.

The first scene is only implicit in the Golden Legend, and shows the future saint being invested as a knight. A squire kneels to put on his spurs; brightly dressed musicians play their instruments and sing, while three spectators look on; and the Emperor Julian himself reaches out awkwardly to clasp the sword around Martin’s waist.

The scene has been created to give the maximum impact to its neighbour, which shows Martin renouncing the ‘profession of arms’ in the most decisive way. In the Golden Legend, we read:

‘Martin continued in the profession of arms for two years. Meanwhile the barbarians were breaking into the empire, and the Emperor Julian, before setting out to war against them, distributed a gift of money to his soldiers. But Martin, being unwilling to bear arms any longer refused the donative; and he said to Caesar: “I am the soldier of Christ; it is not lawful for me to do battle”. Angered at this, Julian said that it was not for the sake of religion that he renounced the profession of a soldier, but out of fear of the impending war.

Unshaken, Martin responded: “If you attribute this to cowardice and not to faith, tomorrow I shall face the enemy unarmed; and in the name of Christ, protected not with shields and helmet, but with the sign of the cross, I shall pierce their ranks in safety”’.

Looking back to the scene of the investiture, now, notice how the foreshortening of the architecture demands that you view it on your left, and note again how relatively convincing and ‘space-creating’ the buildings are. Even without a detail, you can also appreciate Simone’s line and nervous energy in the way the crouching Squire is concentrating our attention on the knightly spurs.

It is the same language of gesture and gaze, the turn of the head and the set of the head on the shoulders, that is the clue to the centre of the fresco.

The Saint dedicates himself to heaven with both hands and eyes, drawing a very uncomfortable and astonished look from the heavily-jowled Emperor.

Among the spectators, the figures on the left demonstrate Simone’s love of colour (they seem to be dressed in the same chequered fabric used in the quilt), his powers of close observation of the real world, and his quiet sense of humour (in the knight’s helmet which is held up to view on what is apparently a cross-bow).

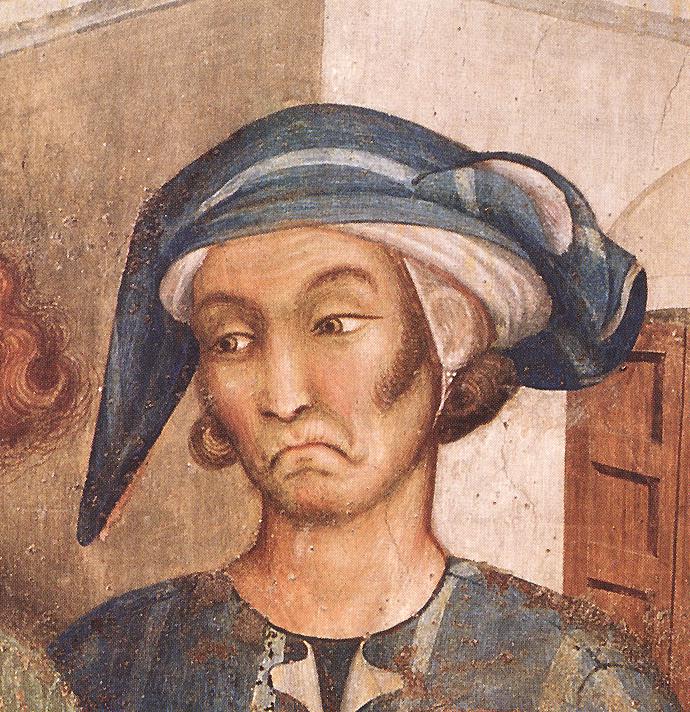

However, the prize in this scene must go to the musicians.

One can almost hear the ‘barber-shop’ harmony of the three singers.

Look at the chequered costume and the floppy hat of the dreamy mandolin player who is stopping the doubled strings with three fingers, while lifting the index finger far higher than a teacher would recommend.

Or again, look at the texture of the dunce’s hat of many colours (which is apparently a Hungarian hat, a souvenir, kept in the artist’s ‘property box’, from a diplomatic mission made by Cardinal Montefiori).

And dwell for a moment on the comic face of the countryman (with conspicuous crow’s-feet around his eyes), playing his two pipes, one in each corner of his pursed lips.

(These two pipes could be the fruit of realistic observation, or they could be a reminiscence of an auletos which Simone had seen on some classical basso rilievo.)

The right-hand fresco in the pair (showing Martin’s refusal to enlist as a paid soldier in the face of the enemy) would be difficult to interpret without the words of the narrative to help us.

(It is not immediately obvious that the white rocks in the centre separate the pavilions in the Roman camp from those of the barbarians who are ‘breaking into the empire’—and, indeed, already riding forth to give battle. Nor could one readily understand the significance of the soldier receiving his ‘donative’.)

But Simone brings out the essence of the confrontation between the incredulity of the Emperor and the faith of the saint simply by the way he paints their faces.

The Emperor (identified again by his jowls and laurel wreath) is clearly baffled, his mouth half open, his eyes popping in frantic disbelief.

Martin—with his golden hair thinning at the temples already, but neatly bobbed in a pageboy style—is all youth and innocence, and yet, simultaneously, all faith and resolution, as his wide eyes turn to meet the Emperor’s gaze, while he half turns his body in the other direction to hold out the cross against the infidels.

Other details are in the scene are highly expressive.

Look at the gold coins being counted out to the soldier (the pay-corporal can hardly bear to watch unearned money being given away); and enjoy the soldier’s tall, romantic helmet (like a hairdryer in a modern hairdressers) or the multi-coloured, Hungarian hat on his rather ill-shaven attendant, who is looking nervously sideways towards the enemy.

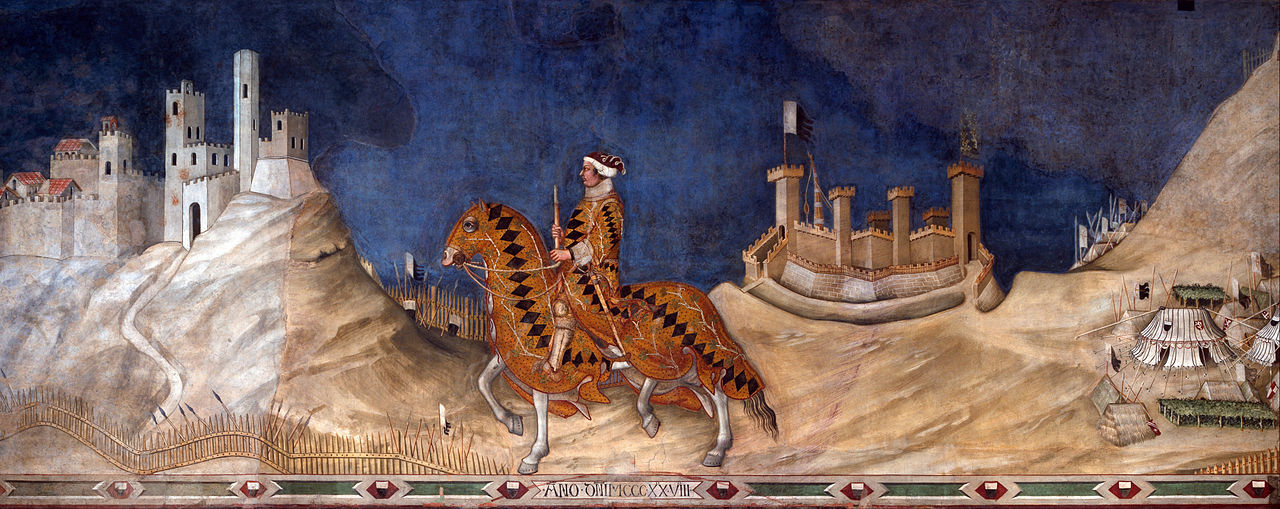

As you look at this area of rocks, river and tents, it is natural to think of its later counterpart in the gigantic fresco in the Council Room of the Palazzo Pubblico at Siena, showing the contemporary mercenary general Guidoriccio da Fogliano, which we shall consider in its context in the next lecture.

(It is dated 1328 and ‘signed’ by Simone; but several scholars believe it to be by a later imitator.)

We jump forward many years in the story now as we come to the frescos in the second tier.

Martin has been discharged from the Army, he has been ordained by Saint Hilary, he has founded monasteries in Milan and Poitiers, he has combatted the Aryan heresy; and he has been elected, most unwillingly, as Bishop of Tours.

The next scenes show him as a ‘working Bishop’, performing miracles, and giving or receiving other signs of saintliness.

The fresco representing the first miracle (which is a couple of feet taller than the one below, showing Martin and the Beggar), has been badly affected by damp in the lower part, but is still reasonably well preserved at the top right, where we see a group of bystanders watching the kneeling Saint, who has just raised a child from the dead through his prayers.

The group is memorable mostly for the head on the right (picked out in the detail), with its superbly confident, three-dimensional rendering of the complex forms of a fashionable hat, and the expression of distaste (and scepticism, perhaps), conveyed by the upraised hand and the down-turned corners of the spectator’s mouth.

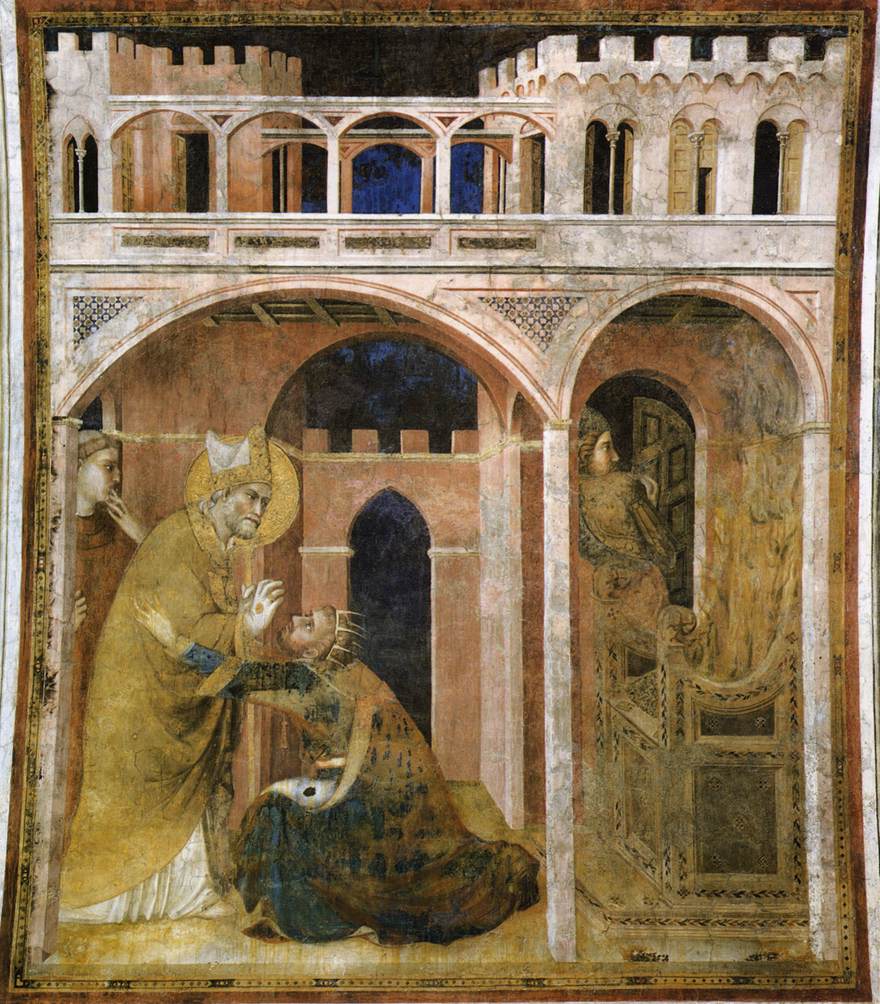

The fresco facing this healing miracle, on the right wall, has also been affected by damp, and I do not have any good details to show you, but the story is so charming—and so funny—that we cannot pass it by.

It concerns Martin’s relationship with a later emperor who refused to grant him an audience and indeed had the bishop locked out of the Palace:

‘After being twice repulsed, Martin wrapped himself in sackcloth and sprinkled his head with ashes and he abstained from food and drink for the space of a week. Then, at the bidding of an Angel, he returned to the Palace and made his way to the Emperor, being hindered by no one. When the Emperor saw him coming, he was angered that he had been admitted; and he refused to arise to receive him, until suddenly his throne was covered with flames, and he was burnt in his hind parts. Then, rising before Saint Martin, he confessed that he had felt the power of God; he embraced the Saint warmly, and granted his petition before it was expressed.’

Once again, the rendering of the architecture of the imperial palace is highly accomplished (notice the rounded arcade and the Gothic windows, the arches and battlements) and serves to create a splendid foil for the bishop’s modest private chapel, placed alongside, which is the scene of the Saint’s third miracle.

The next picture represents the climax of a Mass, that is, the moment of the elevation of the white wafer of the consecrated host; and it is also the climax of a rather complicated story which serves to illustrate Martin’s continuing practical kindness to the poor.

He had given his tunic, secretly, to a beggar; and he had put on, secretly, underneath his bishop’s cloak, the miserably inadequate tunic that one of his archdeacons had given—a tunic so inadequate that:

‘…the sleeves came only as far as his elbows. And so Martin went to celebrate Mass. When, as is the custom, he lifted his hands to God, his linen sleeves slipped back. And since the sleeves of the aforementioned tunic reached only to his elbows, his arms were left bare. Then, by a miracle, Angels brought golden bracelets set with jewels and covered his arms decently with them.’

Two diminutive angels fly downwards to cover Martin’s arms with the huge golden bracelets; while our eyes are steered upwards to the miracle by the sequence of rising, curving lines that begin in the lower folds of the acolyte’s robe, ascend through his loose sleeve and outstretched arm to continue their climb in the folds of the Saint’s chasuble and his upstretched arm.

The vaulting in the tiny chapel is convincingly foreshortened from below, creating the now familiar shallow stage-set.

Once again, the altar is seen from a different, higher viewpoint, so that it is tilted towards us to display three contrasting feats of ‘still life’ painting: a gold crucifix, teetering on the edge of the altar (and unsteadily drawn); the curving ‘petals’ of an ornate chalice (drawn to perfection), and the plain, large-print missal with its sprawling leather clasps, resting at an angle on a cushion.

The last of the frescos in this tier shows a bishop—properly mitred, gloved, and attired—who sits in the transept of a Gothic church next to the altar in the nave, obviously in a kind of trance, or lost in contemplation, unresponsive to the gentle hand of the standing cleric who tries to rouse him, or to the other cleric who kneels before him with the missal.

It is natural—and traditional—to assume that the bishop is St Martin; but I feel sure that Andrew Martindale is right to interpret the scene differently, and that this bishop is none other than the Bishop of Milan, St Ambrose.

The episode will prove to be exactly contemporaneous with the scene in the left-hand fresco in the final pair in the vault above; and we shall have to make ourselves familiar with that part of the story before we can grasp the significance of this moment.

The ninth and tenth frescos form a genuine pair and their edges do indeed touch each other, but not as they are displayed here.

On this page, you see them as if you were looking at the palms of your hands, held up in front of you, with the sides of the little fingers touching.

But to imagine their real relationship, you must join your hands above your head, with the fingertips touching, and look up at your palms in that position.

In other words, the frescos touch each other at the top, in their fictive cornices.

On the right you see Saint Martin on his deathbed—or rather, and very significantly, you see the Saint lying on the ground at the age of 81, his eyes turned upwards to Heaven, having resolutely refused to be moved onto his side to ease his pain, and having insisted on being allowed to die on the ground.

The fresco on the left shows the funeral service, with the saint again stretched out horizontally, fully attired and mitred, but this time lying on his bier.

There was therefore something of a compositional challenge to avoid visual monotony. Simone rises to the occasion by providing two very different architectural settings, each with a centralised viewing point, within the same composition.

On the right, you see a Romanesque loggia and a Romanesque tower which definitely stands under the open sky; while on the left, we have a contrasting interior—a Gothic chapel, with elegant tracery in the narrow windows, and three slender spiralling columns supporting the arches.

It was of course normal to represent the death and/or the funeral of a Saint in a cycle of illustrations. Nor was this merely to round off the story. Miracles were typically reported as taking place at the time of the death or burial which served to confirm the saintliness of the deceased. Thus, in the Golden Legend, we read that at the moment when Saint Martin expired, ‘his face shone as though he were already in glory; and many heard the choir of Angels singing round about’.

From the hagiographical point of view, then, what matters most is the area enlarged in this detail, which shows St Martin being carried off to heaven by four Angels, and is placed directly above the viewer’s head.

Now it becomes clear why the whole narrative had to be told beginning at the bottom of the wall.

(Incidentally, it is not so easy to believe that the figures in this detail were executed by Simon himself, although they are similar in style to the figure of St Michael in the panel at Cambridge.)

The two young clerics who are kneeling close to St Martin exemplify the newly learnt technique of conveying emotion without showing the expression of the eyes or the tautness of the muscles round the mouth. The younger one is shown in profil perdu, while the haloed figure, who is placing the candle in the dying man’s hands, shows more of his tonsure than anything else.

All these figures, with their differing responses to the moment of death, unite in concentrating our attention on the body of the dying Saint. But paradoxically, the most significant of all the bystanders is the young man on the right. Wild-eyed, passionate, rubber-necked, he twists his gaze upwards to the Saint’s ascending soul and the miraculous appearance of the angels in the sky above.

The miracle of the angels is as nothing, however, compared to what is happening in the funeral scene in the next fresco. The Golden Legend tells the story like this:

‘On the same day, Saint Ambrose, the Bishop of Milan, as he was celebrating a Mass, fell asleep between the reading of the Prophecy and the Epistle. No one dared to waken him, nor would the Sub-Deacon read the Epistle save at the Bishop’s command; but after two or three hours had passed, he aroused him, saying: “The hour is long past, and the people are weary of waiting. Command the Clerk to read the Epistle”. He answered: “Be not disturbed, for my brother Martin has departed to God, and I have been present at his funeral and presided at his Obsequies”’.

This is the passage that confirms that it was St Ambrose whom we saw in the eighth fresco (directly below this one), lost in the contemplation of his vision in the cathedral of Milan, even though he was contemporaneously physically present at the funeral in the city of Tours, which is where we now see him again, mitred and haloed.

Only one person is conscious of the miracle, namely, the young man who kneels to kiss the monstrance held out by St Ambrose; and he is clearly meant to be the same youth who directed our attention to the angels in the sky.

On either side of St Ambrose, too, we recognise the bearded priest who was administering the last rites, and the costume and quizzical features of the middle-aged man who was so prominent in the previous scene.

But while this close attention to the links between the scenes in the story is typical of Simone’s art as a storyteller, I would like to end the lecture with two final details that show him as a poet and as a meticulous observer of reality.

First, the noble features of the long-haired, soft-bearded nobleman under the striking black hood which looks for all the world like a helmet.

Second, the wonderful study of two cantores in ecclesia, whose facial muscles are observed with sufficient care for them to form the basis of closely argued theories concerning techniques of voice production in the Middle Ages.

The final comment on Simone’s art simply has to come from the sonnet which Petrarch addressed to his friend. To be able to paint like this, ‘my Simone must have been in Paradise’:

‘Certo il mio Simon fu in paradiso’.