Ambrogio Lorenzetti: Allegory of Good Government

In the first lecture, I talked about the forms and institutions of republican government in the Commune of Siena, under the classic form of the constitution that lasted from 1287 to 1355. There, we learnt something about the Great Council of the Commune, and, above all, about the Consistory or ‘concistoro’, the executive body or cabinet.

(The latter was chaired by the Podestà, attended by a few treasury and guild officials, and dominated by the teams of Nine ‘governors and defenders’, who were chosen by lot from the citizen body, and served full time for two months.)

In this lecture, we shall be looking at frescos which were painted to decorate the rooms in which the two bodies met in the Seat of Government (then called the Palazzo del Comune, and now the Palazzo Pubblico), the administrative fortress which still dominates the lower, southern side of the Campo.

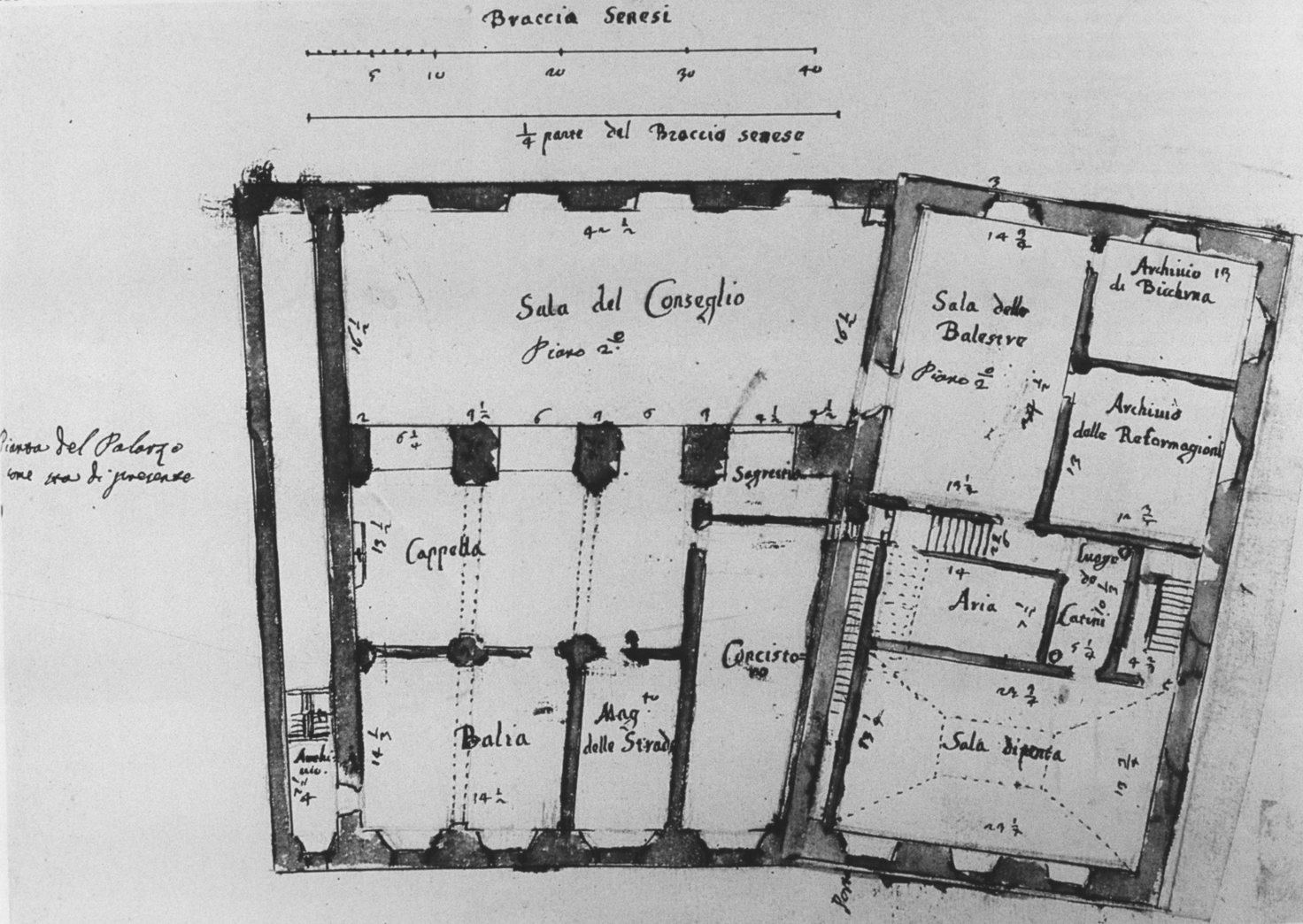

The greater part of the present Palazzo was begun in the 1290s and completed by 1310, and the all-important first floor was originally laid out as you can see in the ground plan (which places South at the top).

The spacious room at the top of the plan was set aside for the Great Council—necessarily large since the Council was three hundred strong; and there was a narrower adjoining room (below it, to the right, on the plan) set aside for the Consistory.

These two rooms were soon decorated with frescos bearing a suitable political message.

The message was complex and subtle for the executive body; but bold and simple for the members of the Council and for the envoys who would be received in the Council Room (envoys representing the Pope or Emperor, or other communes, or, simply, the townships in the ‘contado’).

Let us begin by reading the relatively simple message in the ‘Sala del Conseglio’ (as the larger room is labelled in the plan).

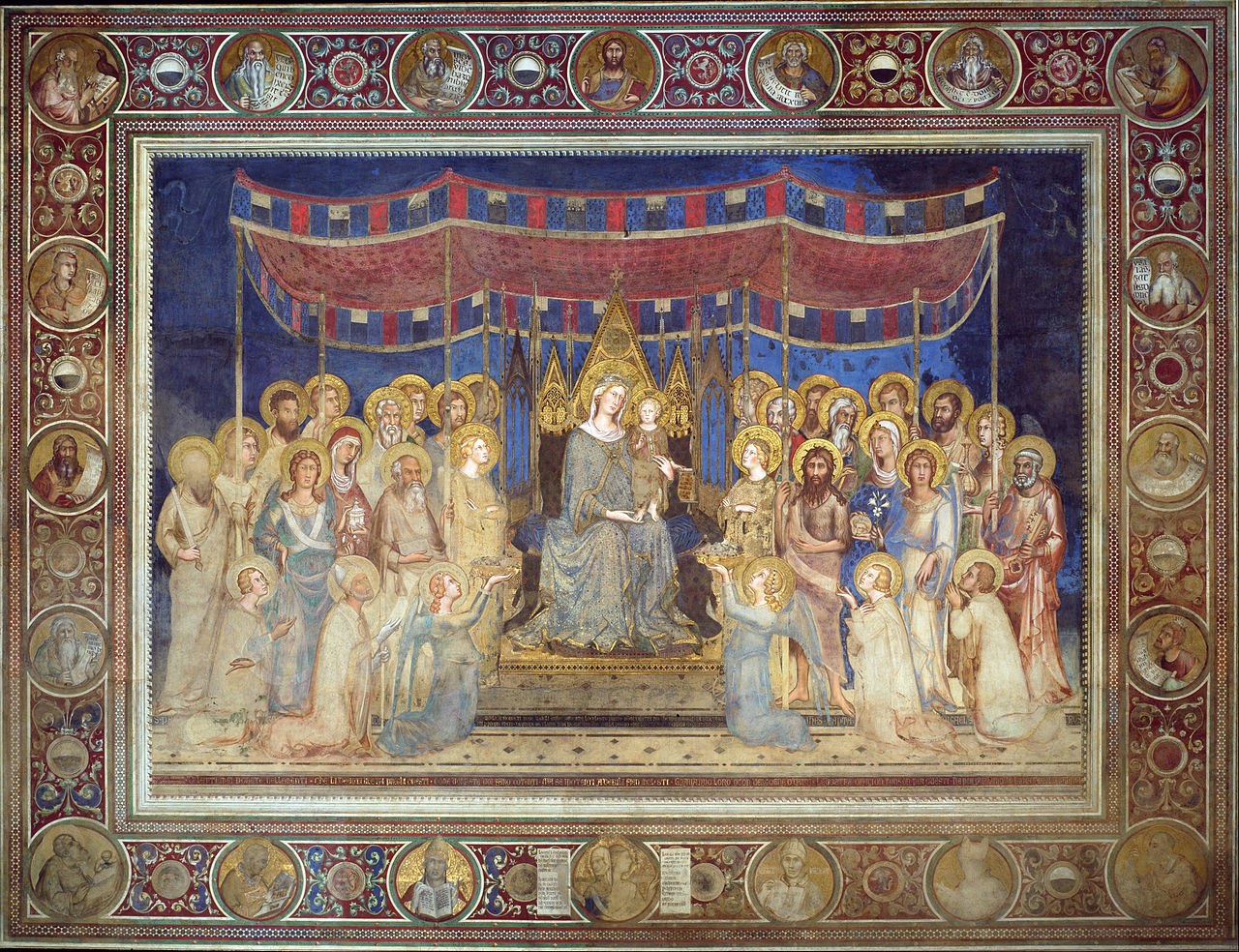

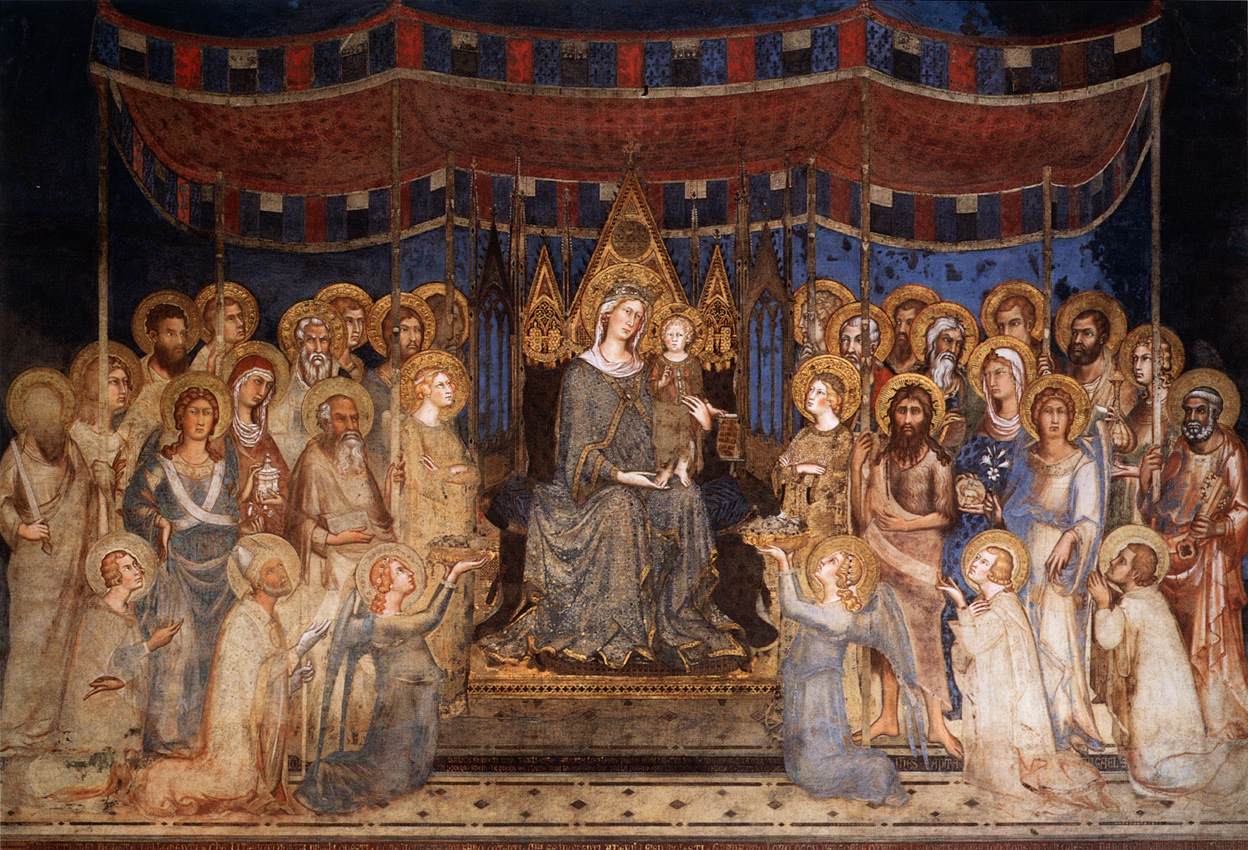

The eastern wall of the Council Chamber is occupied by a giant fresco, showing the Virgin in Majesty (Maestà), in a sumptuously painted, fictive frame about 3 feet wide, containing many medallions: the whole area measures 32 feet across.

The artist was the leading local painter of the generation after Duccio, Simone Martini (who was the subject of the previous lecture). He completed it in 1315.

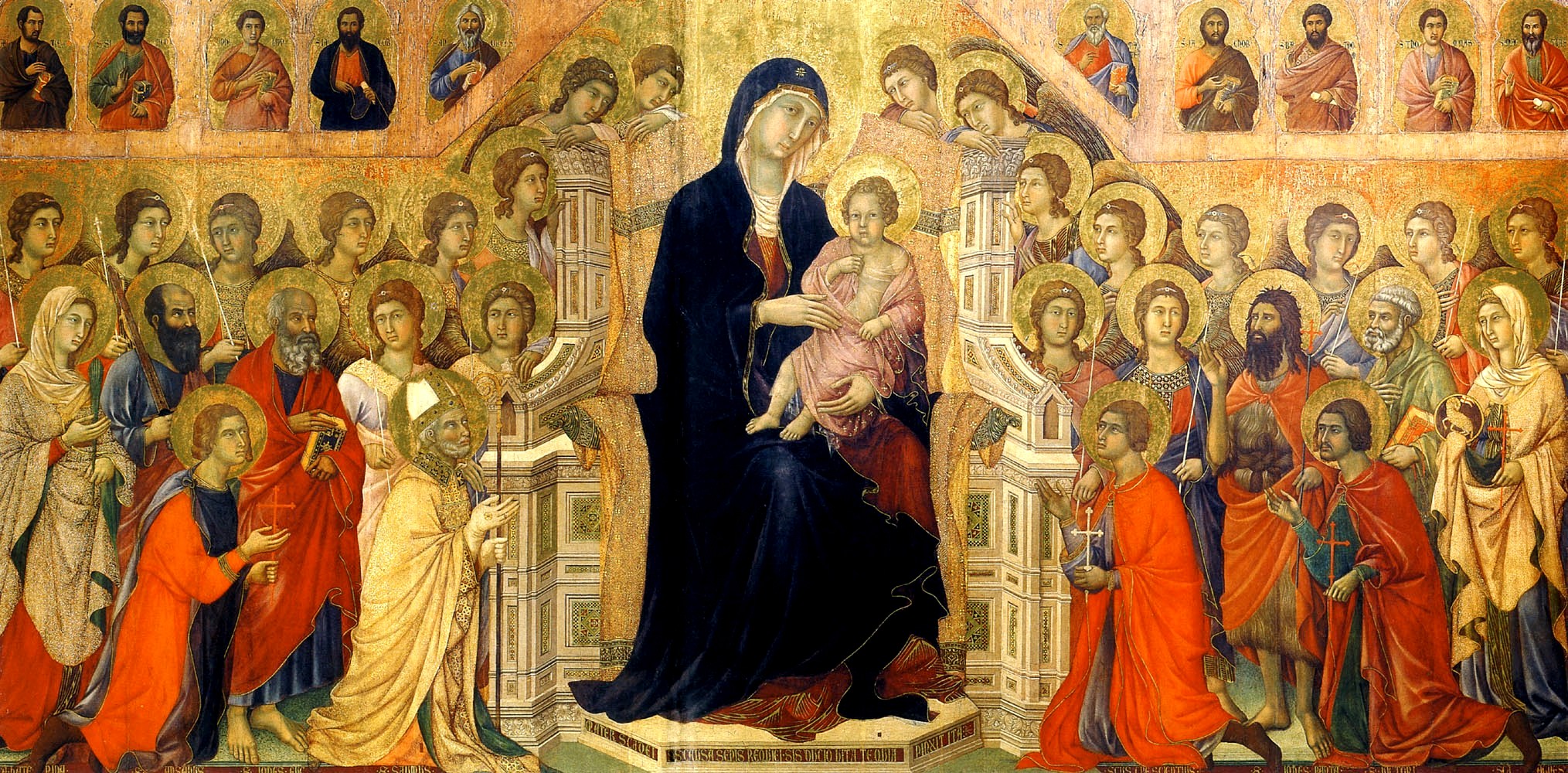

The subject of the fresco, then, is exactly the same as that of the ‘public face’ of the altarpiece in the Cathedral; and indeed the layout is broadly similar to Duccio’s Maestà, which had been completed only four years earlier.

In Simone’s version, the Virgin and her Child are seated on a splendid throne in the centre (once again, larger in scale than the other figures).

She is adored in the front row by four local saints: young Ansano, Savino (the bishop), another youth, Crescenzio, and the moustachioed Vittore, all of whom are praying to Mary for her protection.

In his composition, Duccio had added three major saints on each side of the throne in the second row and filled most of the back row with angels, in a very formal ‘group portrait’. But Simone is much more relaxed, even ‘laid back’: it is astonishing to recollect that there are only four years between the two works.

He slips in a pair of very youthful angels, kneeling, in the front row, and two others in the middle of the second row. But everyone else is a saint; and their haloed heads are grouped with delightful freedom, not only one above the other, but also one behind the other, because the splendid canopy is foreshortened to suggest considerable depth—a depth which does not really exist in Duccio’s Maestà.

The throne is decorated with five triangular panels (resembling a polyptych). And Mary is dressed, not in the regulation blue mantle of tradition, but in an exquisite brocade, with a simple crown over her veil, so that she looks like a princess in an Arthurian romance.

We must come now to the political message.

Part of this is contained in the fictive frame, where the portrait medallions of selected prophets and patriarchs are supported by smaller heraldic shields bearing two coats of arms—alternately, the black and white colours of the Commune of Siena, and the lion rampant of the Popolo di Siena, whose rights and privileges had been wrested from the nobles and were to be protected by the three hundred non-noble members of the Council seated in the Chamber.

(We also find the same shields and colours on the canopy.)

But the message of the whole composition is distilled in the verses which are printed as prose at the foot of the throne. (They form two, seven-line stanzas, written in the metre of the Divine Comedy—the poetic level being perhaps not quite so high.)

The words are to be understood as spoken by the Virgin. Each little poem begins with a brief affirmation of her general good will, as in the first:

Diletti miei, ponete nelle menti

che li devoti vostri preghi onesti

come vorrete voi, farò contenti.Best beloved, keep it in your minds

that I shall grant, as you would wish

your devout and righteous prayers.

Each poem continues, however, with a ‘but’ (Ma), and a warning:

Ma se i potenti a’ debili fien molesti,

gravando loro o con vergogne o danni,

le vostre orason non son per questi,

né per qualunque la mia terra inganni.But if the powerful oppress the weak

weighing them down with humiliations and penalties

well, your prayers are not for them

nor for anyone who deceives my city.

And in the other poem:

Li angelici fioretti, rose e gigli,

onde s’adorna lo celeste prato,

non mi dilettan più ch’ e’ buon consigli.

Ma talor veggio chi per proprio stato

disprezza me e la mia terra inganna:

e quando parla peggio, è più lodato.

C’om guardi ciaschedun cui questo dir condanna.The angelic flowers—roses and lilies—

which adorn the meadow of heaven

do not delight me more than good counsels.

But sometimes I see someone who for his own interests

holds me in scorn and deceives my city;

and the worse he speaks, the more he is praised:

beware of everyone whom this saying condemns.

Hence Simone’s Virgin is there to remind the councillors always to give good advice, ‘buoni consigli’, not inspired by ‘self interest’, and not tending to ‘deceive’.

All along the northern wall of the Council chamber and on part of the western wall, came a series of sterner, threatening images which were intended for outsiders—the local nobles, and the local towns, in the first instance, but also for envoys from the territories lying on the borders of the contado, chief among them the commune of Florence.

This detail from a political map in a school atlas offers a very useful selection of the more important cities in Northern Italy in the late Middle Ages, and uses its four colours to give a good impression of the areas under the influence of the dominant cities.

It represents the state of play in around 1400, (hence almost a century later than our period), when the Duchy of Milan briefly dominated the huge area in green.

But it will help you to bear in mind the size and shape of the territories controlled by Venice (red), the Papal States (yellow), and above all, Florence (orange).

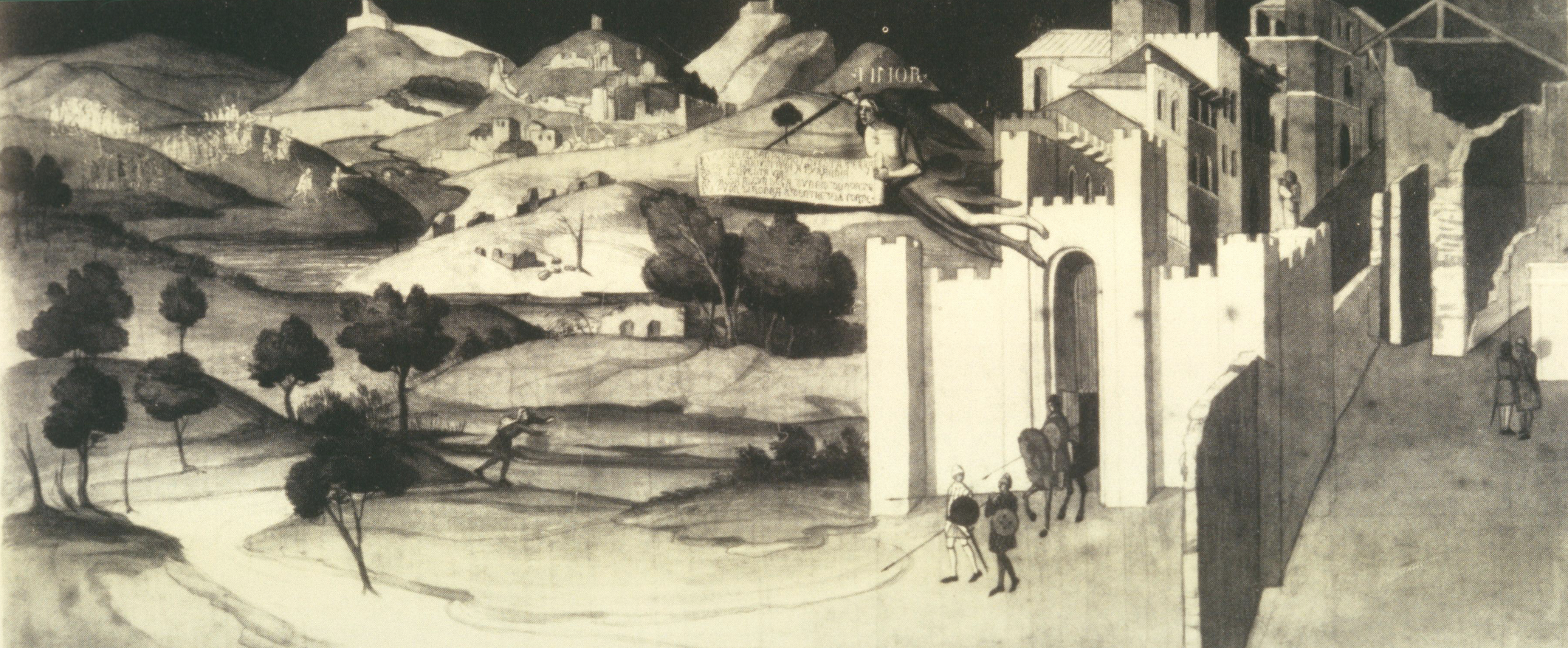

The more threatening images were no doubt conceived as a warning to Siena’s immediate neighbours. Those on the long northern wall have been painted over, but we know they were similar in nature to those that have survived on the west wall.

The splendid example on this page was discovered and restored only relatively recently. It measures about fourteen feet by ten, and must have been painted between 1304 and 1320. It shows an official of the commune receiving the submission of one of the noble fortresses in the contado.

The dazzling drawing-skills (look at the palisade) and the eclectic but expressive use perspective, better seen in the detail, makes one fairly certain that the artist is not Duccio, as some have argued, but either or both of the Lorenzetti brothers, whose skill in this branch of their art we shall have appreciated by the end of this lecture.

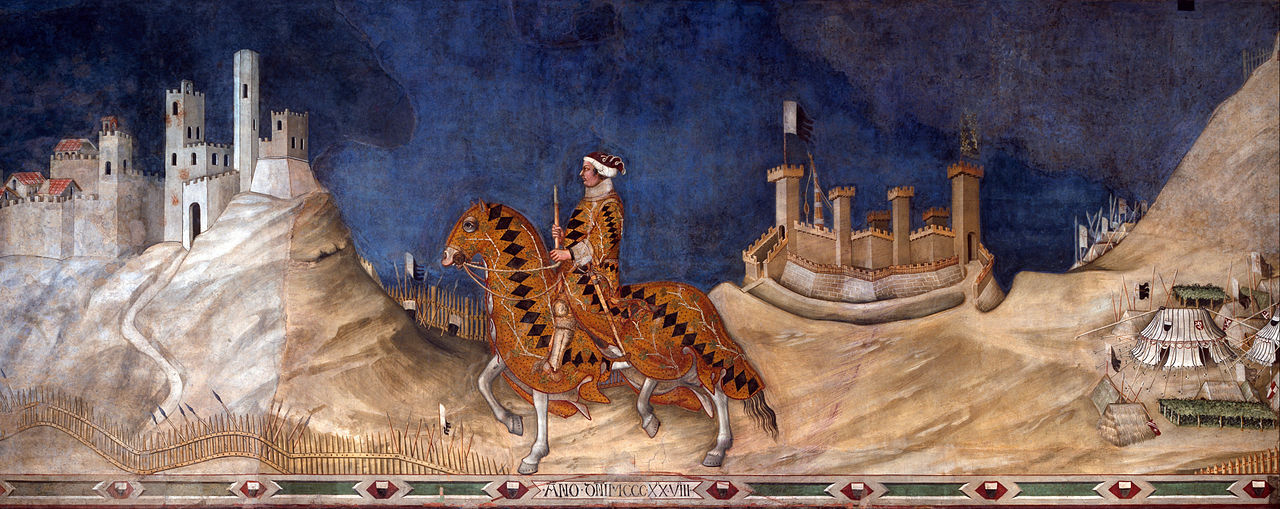

Above that admirably direct reminder of Sienese military power we find this celebrated fresco, running the whole width of the wall (thirty-two feet by eleven).

It has always been attributed to Simone Martini, although I have come to share the misgivings of recent scholars, who suggest that it is an imitation of his style later in the century. But whatever its date and authorship, its message is a perfect visual distillation of the themes of the first part of this lecture.

It depicts two townships in the contado, Monte Massi and Sassoforte di Maremma, which had rebelled in the year 1328 (you can read the date below the painting).

This rebellion was promptly suppressed by a professional soldier, Guidoriccio da Fogliano, who served the commune in what was then a relatively new post, called the ‘Captaincy of War’.

Thus we must think of the splendid figure in the centre not as a portrait of the individual man, nor as the typical mercenary general of the kind who came to wield enormous power all over the peninsula for the next 150 years, but as, precisely, the ‘Captain of War’, the personification of the commune’s will and power to defend the city and to assert its authority over the contado.

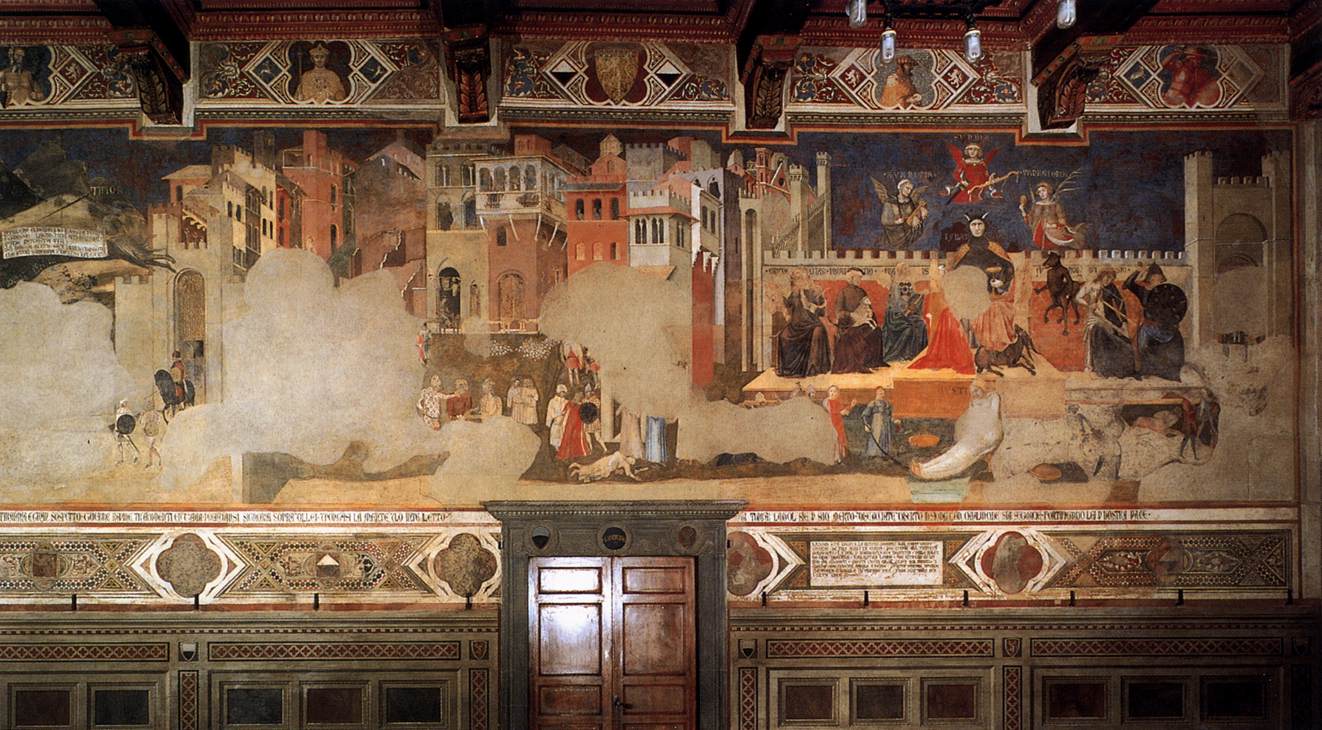

We now pass into the smaller adjacent room (now called ‘La Sala della Pace’), which was originally known as the ‘Room of the Nine’, ‘La Sala dei Nove’.

It was in effect the Cabinet Room, where the Podestà and the half dozen ex-officio members met with the ‘Nine Governors’ who were serving their two month term.

The room measures about fifty feet by thirty-two, and is lit by a window on the south wall (behind the camera in the photograph).

It is obvious that the frescos are there to remind the members of the Consistory—only one of whom serves for more than a few months—of the nature of their office, and of their duty to act in the Common Interest, not to ‘oppress the weak’, and not to seek ‘their own advantage’, nor to ‘deceive the city’.

The political message is not particularly complex, but since the publication of George Rowley’s monograph on Lorenzetti in 1958 there have been half a dozen major contributions to the interpretation of the room—chief among them two magisterial articles by Professor Quentin Skinner.

To put it very simply, Professor Skinner argues that Ambrogio’s political ‘language’ derives from the works of Italian ‘civic humanists’ active in the period 1220 to 1270, the best known among them having been Dante’s mentor, Brunetto Latini.

He reminds us that the frescos are not to be related too narrowly to the constitution of Siena under the Nine, because the message is valid for any of the city republics in medieval Italy, and, by extension, for any ‘just’ human society anywhere in the world.

(One of Professor Skinner’s great merits is that he writes in the conviction that it was a painter, Ambrogio Lorenzetti, who made ‘the most memorable contribution to ‘the debate about the ideals and methods of republican self government’, and that Ambrogio deserves our respect, in his own right, ‘as a political philosopher’.)

So let me attempt a close reading of the painter’s ‘treatise’, starting with this central fresco on the North wall—some thirty feet across in reality.

(Before I plunge in, let me make it clear that my own reading is based on the principles that a valid interpretation must be faithful to the words written within the composition, or on the wall below, and must take into account the spatial layout of the figures—including antithetical relationships to the parallel figures in the fresco alongside.)

Above the head of the personified virtue enthroned on the left, there is a phrase transcribed to form a semicircular arch. It is the Latin translation of the opening of the Book of Wisdom (a canonical work in the Vulgate). It says: ‘Diligite justitiam, qui iudicatis terram’.

Literally, it means ‘Love justice, you who judge the earth’. But we ought to take note of three important implications in the Latin that get lost in translation. Justitia may refer to a moral virtue possessed by an individual and must often be translated as ‘righteousness’ or ‘uprightness’. The word ‘judge’ (iudex), in the Old Testament, means a ‘supreme magistrate with civil and military authority’. And in medieval Italian, terra was very often used to mean ‘city’, or ‘native city’.

Thus, within this room—the Cabinet Room—the phrase may be construed as an exhortation addressed specifically to all the members of the Consistory: ‘Ye that be magistrates of the city, foster justice’.

Within the context of fresco itself, however, where other personified virtues are labelled with their Latin names, it is obviously natural to refer the word Justitia to the large enthroned female immediately underneath the inscription, who is represented with a pair of balances suspended above her head.

It is also natural to construe the second-person plural verb (iudicatis) as a so-called ‘plural of majesty’, referring to one person of importance, who, in this case, could only be the largest figure in the fresco, the enthroned male, who is placed between six other female virtues. In this case, the Latin phrase would mean: ‘Thou that judgest the earth, love righteousness’; or, simply, ‘Let the Judge love Justice’.

From the ambiguities or multiple meanings of that one brief text, we must now pass to the spatial organisation of the whole wall.

Horizontally, it divides into three tiers.

Above, we have the heavenly or celestial plane, with winged figures (duly labelled) representing the three theological virtues, together with Divine Wisdom, who is labelled Sapientia and who holds the ‘Book of Wisdom’ in her hand. At the lowest level, we have the earthly sphere—the particular, the concrete—with individual human beings in contemporary dress who exemplify (rather than symbolise) the citizens and officers, and the whole commune of Siena.

Between the upper and lower tiers, there are abstractions or personifications, representing qualities or offices found in any human society at any time. These are general concepts, and there is usually no doubt as to their meaning, because each figure is labelled and given a traditional, symbolic attribute.

The only exceptions to this division into three tiers are the four individuals next to Justice (who are in contemporary dress, like the figures in the bottom row), and the figure labelled Concordia (hence an abstraction), who is seated at ground level, but might have been expected to appear in the middle row.

Vertically, the composition has a strong ‘caesura’ in the upper two registers, dividing it into one third plus two thirds; while the human figures in the lowest register are grouped, facing each other, two thirds plus one third, on either side of the Judge’s throne.

Let us now look in some detail at the right hand group in the middle and upper tiers.

In the centre, largest in scale, sits the massive male figure, enthroned. Above him, there is an ‘arch’ formed by the three theological virtues.

He is flanked by six crowned figures, the earthly virtues, three to each side. At his feet, there are twin boys. On his left hand (like the Damned in a scene of the Last Judgement), there are bound and pinioned malefactors under the control of some men-at-arms; while the virtuous citizens, like the Blessed, are assembled on his right.

There is little that needs to be said about the three theological virtues, except to point out that they are arranged, not in the sequence Faith, Hope and Charity (the order suggested by Saint Paul), but with Charity, ‘the greatest of these’, in the centre—placed highest, and directly above the enthroned male.

The general message is clearly that no society will be just or happy unless and until men are ruled by love, ‘on earth as it is in Heaven’. (Dante, in a highly relevant context, wrote that ‘love will most give strength to justice’, caritas maxime iustitiam vigorabit).

However, this is a presupposition, rather than the burden of the argument. Who or what, then, is the dominant male?

At one level, he would seem to be the Commune of Siena. He wears the black and white colours of the republic, and his shield is the seal of the city (you can see traces of the Virgin to whom the commune was dedicated). Round his head are the letters C S…C V, standing for ‘comune Senarum, civitas Virginis’, and at his feet, you will see the Sienese wolf, and the twin sons of Remus, Aschio and Senio—the last-named being the legendary founder of the city that bears his name.

The man is obviously seated in authority or judgement, like a Biblical judex. In other words, he is the man who ‘rules’ the city; and if you want a masculine noun for him in Italian, he is its ‘signore’, the Lord. But, of course, Siena was a republic and did not have a ‘Lord’, and (as we saw in the first lecture) all the checks in the constitution were designed to prevent any one man from holding power in perpetuity.

Hence, the masculine singular ‘He’ must represent in reality a corporate ‘She’—a feminine noun. Not ‘Signore’, but ‘Signoria’: in other words, the Consistory.

On this view, the figure represents the ‘Nine Governors’, headed by the non-Sienese Podestà, who have been given brief authority to enforce laws, and (where required) to make or change them, for the common good (‘il bene comune’) or for the good of the Commune, (‘il bene del comune’). And on this view, it is they, as a collectivity, who are being exhorted to ‘love righteousness’.

What are we being taught about the way in which the ‘Signore / Signoria’ should exercise his or their authority?

Certainly, the Signoria is to be inspired and ‘invigorated’ by Charity to love Justice; but it is also to be guided and advised by the six counsellors, the ‘princesses’, seated on the dais beside him. So let us now turn to examine their names and attributes, beginning on the right of the central figure.

On the far right is a figure labelled Justitia, holding in her left hand a crown, to be placed on the head of a virtuous man as a reward, while in her other hand she holds a sword, with which she has severed the head of an offender.

This lady would seem to represent Justice as we understand the word in ordinary speech—not ‘fair play’ or ‘righteousness’ in general, but the necessary enforcement of the written law.

Next to her is Temperance, or Self Control, whose attribute here is an hour glass, which establishes a link between temperantia and mensura, by insisting on the measurement of tempus, Time.

These are two of the four so-called ‘cardinal’ (meaning ‘pivotal’) virtues.

The other two cardinal virtues sit next to each other, to the left of the ‘Signore’/‘Signoria’ (that is, on his right hand).

Nearest to him, richly robed and beautifully painted, comes Prudence; that is, ‘practical wisdom’, or ‘good judgement’, who was acknowledged to be the ‘lamp-bearer’ of the cardinal virtues. (Tiny flames illuminate her scroll from below, calling attention to the words ‘past, present and future’.)

Next to her, dressed in black, armed with a shield and short-sword, cool like a Valkyrie, stands Fortitude or Courage—that is to say, resolution in the face of danger.

There are some innovations in the attributes of these four figures with respect to the iconographical tradition, but there is nothing very unusual or controversial in the suggestion that a good ruler or judge should be courageous, able to assess present needs in the light of past experience and future aims, able to control his own appetites and fears, and able to enforce the letter of the law.

More interesting is the inclusion of the two virtues that I have not yet mentioned, who sit at the left of each group of three.

First, we have Magnanimitas, a virtue singled out for special praise by Seneca (as Quentin Skinner points out).

In fourteenth-century usage, ‘Magnanimity’ had a marked semantic overlap with ‘Munificence’, ‘giving generously’; hence, she is shown distributing coins from the bowl in her lap.

Second, we come to the real surprise, the reclining figure of Pax, ‘Peace’.

Peace is not a personal virtue, but a condition—as the civic humanists agreed—which all good government seeks to establish or preserve.

She is by far the most interesting figure of the six from every possible point of view; and it is she who is also very close to the centre of the composition, and hence to the centre of the room to which she has given her name (it is now known as ‘la Sala della Pace’).

Her pose is quite different from all the others.

She is ostentatiously at ease (‘riposata’ will prove to be a key adjective), reclining in the attitude of a classical river deity.

Her pleated dress clings to her form (and the dress is known to derive from a classical statue of Venus, now lost).

She holds an olive branch, and is crowned with olives.

She leans her elbow on a cushion, which rests on the discarded armour underneath, while a shield and a helmet lie at her feet.

To secure peace, however, justice must be enforced—by men who are wearing helmets and armour.

These are to be found among the soldiers and knights in the lowest register, to the left and right of the judgement seat.

They supervise the prisoners, whose arms are pinioned and bound to those of their fellows.

This group seems to include rebels as well as mere common criminals, since the two at the head seem to be nobles from the ‘contado’, bare-headed, but still in full armour, as they offer their towered fortresses in submission.

At the risk of spoiling the story, I shall go straight to the punchline, ignoring the controversies about the two barely legible words written on either side of the central figure, and drawing instead on my knowledge of a famous poem about justice, written some 30 years earlier by Dante: ‘Tre donne intorno al cor mi son venute’.

In Dante’s canzone, the ‘three ladies who take their place around his heart’ are relatives who stand in the vertical relationship of Mother, Daughter and Grand-daughter. Allegorically, they represent three successive manifestations of Justice.

In the light of Dante’s allegory, I understand the massive central figure (who is wearing red, the colour of the ‘popolo’ in Siena) neither as divine justice (defined as that which is consonant with the will of God), nor as the so called ‘positive law’, ius positivum (a body of local laws, of customary law, varying in time and place), but as something very like Natural Justice—the instinct for ‘fair play’ (to use our term) or for ‘equity’ (to use theirs), which is to be found in all men, simply because they are ‘rational’ and social animals.

Justice, thus understood, is the virtue that ‘gives everyone their just deserts’ (suum cuique, literally, ‘his own to each’). She arbitrates; she finds the ‘right balance’; she seeks or restores ‘equilibrium’.

As you can infer from the two kneeling figures in the detail, she is not to be identified simply with criminal justice. It is ‘naturally just’ to give malefactors their ‘due’—that is, giving bad in return for bad. But Natural Justice is also involved in making appointments to office, in promotion, or in the preparation of what we would call an ‘honours list’—returning good for good, as in the crowning of the benefactor (who is clutching the palm of victory).

Natural Justice also intervenes as mediator in all disputes between individuals as to the worth of the goods and services which they ‘interchange’; and I agree with the proposal that the angel in white is holding out a measuring rod (a yardstick) and a recognised measure of volume, in order to determine the appropriate and just ‘rate of exchange’.

Natural Justice is looking up to her source in Divine Wisdom; and it is Sapientia who holds the ‘staff’ of the pair of balances over her head (notice how Natural Justice is resting a thumb equally on both scales, in order to ensure that they start in equilibrium).

What Justice is seeking by her gaze is that which King Solomon had asked for: ‘an understanding heart to judge thy people’.

(Solomon in this period was believed to be the author of the Book of Wisdom, which, you remember, is the source of the crucial quotation inscribed above the whole group: ‘Diligite iustitiam, qui iudicatis terram’.)

In the lowest tier, Natural Justice has produced her ‘descendant’—the quality of Concordia. (Ambrogio’s ‘granddaughter’, incidentally, is very different from the ‘third’ of the three ladies in Dante’s poem.)

You will see that, by a typical medieval pun, there are two cords (one grey, one red) running from the evenly-poised scales down to the left hand of Concord (whose name is etymologised, poetically, as She ‘with the cords’, cum cordibus).

Concord, in turn, is shown passing the two cords, sideways now, to the citizens on her left—but only after she has plaited them into single rope, in which the grey and red strands are clearly visible. Wherever the spirit of concord and of unity exists, it will ‘iron out’ any local differences between members of the group.

To drive the point home, the name Concordia is written on the huge carpenter’s plane steadied by her right hand—this being instrument par excellence used to ‘smooth things out’.

We now approach the question of how to interpret the actions of the Twenty-four Elders (the number is not casual), who carry the intertwined strands from the figure of Concord to the gigantic male figure, whom we have called, variously, judge, ‘signore’, ‘signoria’, ‘ben comune’ and ‘comune di Siena’.

Here I must draw more explicitly on Professor Skinner’s essay, and remind you that there had been two rival views concerning the origins and nature of human society. The first, or pessimistic one, eloquently expressed by Cicero and repeated by Brunetto, assumes that men are naturally savages; that they were first brought together and ‘civilised’ by a great ‘law giver’—a Moses, or a Solon; and that they will always need the stern rule of law and strong authority if civilisation is not to revert to savagery again.

The second view, more optimistic, taken as axiomatic by Aristotle, holds that man is a gregarious animal by nature. More precisely, he is an animal designed to live in a civitas or polis—a ‘political animal’; and he has a natural instinct for the virtue variously called ‘fair play’, ‘equity’ or ‘natural justice’, which must regulate the relationships of unequal individuals within a political unit. The two views may seem contradictory; but most of us could find anecdotal evidence to support either of them from our daily observation (of ourselves, our children, our colleagues, or the nations of the world).

Broadly speaking, then, I am inclined to think that Lorenzetti is giving equal weight to both views, and that he is showing how the pessimistic and optimistic views may be reconciled. More than that, he seems to be demonstrating how they have in fact been reconciled in the constitution of his native republic and in the day to day decision-making of its executive body. In the group to the right of the throne, he stresses authority, the rule of law, and the permanent need for the enforcement of law. On the other side, in the body of citizens, he gives expression to the Aristotelian position. The citizens take the ‘con-cords’ of Natural Justice, and freely and ‘in concord’ take it to the ‘signoria’. They attach it to the staff of authority; and by so doing, they ‘tie’ the right hand of ‘la signoria’.

This ceremonial binding serves to remind the members of the executive that the source of their power lies in the free will of the community—not in brute force, not in the pope or emperor, not in hereditary rank—and, simultaneously, to remind them of the need to exercise their brief authority in accordance with the principles of Natural Justice.

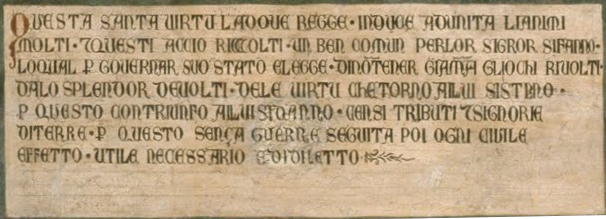

Now let us read the words painted on the wall beneath the fresco to demonstrate that my interpretation of the visual evidence is indeed in accord with the meaning of the long inscription.

The text is set out in seven straggling lines, like this:

Questa Santa Virtù Ladove Regge Induce Adunita Lianimi

Molti. (E) Questi Accio Ricolti. Un Ben Comune Perlor Sigror Si Fanno.

Loqual P(er) Governar Suo Stato Elegge Dino(n) Tener Giam(m)a Gliochi Rivolti

Dalo splender Devolti De Le Virtu Che Torno Allui Sisteno

P(er) Questo Contriunfo Allui Si Danno Censi Tributi (E) Signorie

Diterre. P(er) Questo Sença Guerre Seguita Poi Ogni Civile

Effetto. Utile Necessario e Didiletto.

The inscription looks like notarial prose, but is in fact a piece of regular verse, a canzone stanza in hendecasyllables and heptasyllables, rhyming and structured according to the principles set out by Dante in his book on Eloquence in the Vernacular.

The metrical structure—(I+I) + II—is shown by the indentations in the following conservatively standardised transcription. (Lines 1–4 are metrically identical to lines 5–8: they form the two pedes in Dante’s terminology. Lines 9–13 (the sirma) have different rhyme-sounds and a different arrangement of the pattern of the rhymes.)

The rhyme scheme of the thirteen lines is: ABbC; ABbC: C, Dd, EE.

Questa santa virtù, là dove regge,

induce ad unità li animi molti;

e questi, a ciò ricolti,

un ben comun per lor signor si fanno;

lo qual per governar suo stato elegge

di non tener giammai gli occhi rivolti

da lo splendor de’ volti

de le virtù, che torno a lui si stanno.

Per questo, con trionfo, a lui si danno

censi, tributi e signorie di terre.

Per questo, senza guerre,

séguita poi ogni civile effetto,

utile, necessario e di diletto.

Where this holy virtue reigns

she brings to unity many minds,

and these, gathered together for this end,

achieve one common good through their lord;

who, to govern his state,

chooses never to turn his eyes away

from the brightness of the faces of the virtues

who are around him.

Through this [respect for the virtues], triumphantly,

taxes, tributes and lordships of cities are given him.

Through this, without wars,

there follows every effect of civilised living,

the useful, the necessary, and the delightful.

In a moment, you will see what is meant by the phrase ‘ogni civile effetto’, as you simply sit back and enjoy one of the accessible masterpieces of Italian medieval art in the fresco that occupies the opposite wall in ‘La sala della Pace’.

But before we turn away from the conventions of personification–allegory, we must at least glance at the figures in the much damaged fresco on the west wall.

It is a ‘cautionary tale’, where the images of Justice, Peace and the Virtues are replaced by personifications of their polar opposites—Injustice, War, and the Vices. Similarly, the just ‘Signore’ is replaced by a demon with horns and fangs, who is labelled ‘Tyrant’.

The fresco has suffered severely from damp, but if we examine a few details of the main figures, we may at least take note of the antithetical relationships which should fill out our understanding of the parable of Justice and Peace.

In the high register, then, there are three fundamental vices corresponding to the theological virtues: to the left, Avaritia, an old woman, equipped with a hook to gather in, and a ‘press’ to squeeze and to hold tight; on the right, Vanagloria, a young woman, admiring herself in a hand mirror; and, above them, the ‘beginning of all sin’, Superbia (pride), with a sword and a ‘yoke’ to oppress.

Directly underneath Superbia, we see Tyranny (Tyrammides) who is given the horns and fangs of a traditional devil in medieval art. He wears armour hidden under his cloak, has a demonic goat at his feet (instead of the Sienese wolf), and clutches a dagger and a cup of poison.

Three of of his six infernal counsellors appear to the left of the composition (on his right hand). Cruelty, an old woman, is throttling a child and frightening it with a snake in her other hand. Treachery (Proditio) is holding an animal which is half lamb, half scorpion, innocent in the face but with a sting in its tail. Fraud (Fraus), has bat-like wings, and talons instead of feet.

On the other side of Tyranny, we find Blind Rage (furor, the fury of the lower classes in revolt), a hybrid, with the head of a wild boar and the tail of a wolf, holding a dagger and a stone.

Next to him (a human female again), there is Discord (divisio), the opposite of ‘Concordia’. Her hair is dishevelled; she is dressed half in white and half in black, with ‘sì’ on the white side and ‘no’ on the other; and she is holding not a carpenter’s plane, but a carpenter’s saw, with which she tries to saw herself (or some other object) in two.

The sequence is closed by ‘War’ (guerra), the opposite of Pax—with armour, helmet, and shield, her sword raised, and with a coffin open at her feet.

Thus far, we have looked only at the right hand side of the fresco, and we must turn our attention to what lies—or used to lie—to the left (sadly, damp has now obliterated almost half of this area).

It shows a city—a city very like Siena; and it shows the effects of ‘tyrannical’, ‘vicious’ government, in a more concrete pictorial idiom.

The houses and towers (a wonderful feat of close observation and advanced perspective) are clearly in disrepair (although the damp has perhaps rather exaggerated this result).

The shops are shut, except the armourer’s. The streets are almost deserted, except for armed and violent men such as the two who are seizing a woman for their own fell purposes.

From the city gate (one of the few areas to survive the damp), a horseman on a black horse, superbly drawn, sets out with two foot-soldiers to ravage the ‘contado’, which, save for a scene of banditry, is deserted, uncultivated, unproductive.

The allegorical figure flying in the sky over the city-gate used to be labelled Fear (timor).

Above the fresco, in the wide fictive border, there are medallions representing the ‘baleful’ planets—Mars, Saturn and Jupiter; while in the medallions of the lower border, we find this expressive head of Winter, who is clutching a snowball in a snowstorm.

There are also portraits of notorious tyrants, such as Nero.

It is a shame, of course, that we can no longer enjoy Lorenzetti’s vision of a ‘hell on earth’, either in the allegorical analysis of the causes or in the superbly realistic representation of the effects; but we can at least rejoice that the other long wall is still in relatively good repair.

‘Rejoice’ is the right verb, because the whole of this wall—fully fifty feet wide—is given over to a celebration of the effects of ‘Justice and Peace’ provided by the rule of the ‘signoria’, that is, of the ‘Nine Governors and Defenders’ of Siena.

Remember that they met daily in this very room, deliberating for ‘the common good’, or ‘the good of the commune’; and that the effects of their deliberations are evident both within the city walls (in this half of the fresco), and beyond them in the contado.

It is a vision of ‘Heaven on earth’. Nothing is forgotten, not even in the fictive frame.

The planets represented in the medallions above the fresco are the beneficent ones, Mercury, Venus and the Moon; while the tyrants of the opposite wall are replaced by the Liberal Arts (such as Grammar), and the ‘Winter of Discontent’ is answered by the ‘Summer of Harvest Home’.

In the sky, just outside the city wall (in the position where the tyrannised city had the figure of Fear), we see Securitas, whose pose and drapery is derived from a classical statue.

She holds a notice inviting everyone to:

‘walk freely and without fear,

and to sow the seed, and to labour,

for so long as the commune

shall hold this virtue as its liege lady:

for she has taken all power from the wicked’.

It is one of the ‘wicked’ whom we see hanged on the gibbet held in her hand.

Below her, the well-hedged fields of the market gardens give way to open fields, spreading across the extraordinary bumps of the chalk downs (I used to think these hills were no more than a rather primitive stylisation, until I got to know the area of the ‘crete’ in the countryside to the South of Siena).

In this vast expanse of countryside—unparalleled before Lorenzettti in Italian art—we are shown the characteristic ‘labours’ of the months, because the productive seasons of Spring, Summer and early Autumn, are shown simultaneously in different parts of the landscape.

The first detail shows both ploughing and the ‘broadcasting’ of seed’. (Notice how the man in the foreground is covering the seed with his mattock, to protect it from the gulls.)

In front of the reapers and binders, men begin to thresh and winnow the grain with slow alternate strokes of their long flails. (The seed will be stored in the tiny barn behind them.)

Rich pickings are left for the cock and hen; and the straw is made into stooks.

Beyond the watermill (which will serve to grind the corn), a team of pack mules crosses the narrow bridge; and to the left, we see a ‘contadino’ driving his pig to market.

Meanwhile, still in the countryside, a well-dressed nobleman and a lady are setting out for a day’s hawking; she perhaps will toss a coin to the beggar by the roadside, before they catch up with their peers, who are already galloping, hawk on wrist, behind their pointers.

(The contrast is stark between these scenes and the barren, deserted contado of the Tyrant and the state of War that we saw on the opposite wall.)

Now let us turn our attention to the effects of justice and peace within the city, following the peasants to the left, as they pass through the city wall into the main street.

Four pack-mules, laden with bales of wool, enter and turn to the right, close to a woman weaving at her loom. Other mules, with staves or firewood are unloading near a stall.

A shepherd drives a small flock in the other direction, crossing two women, each of whom is carrying a kid or a lamb—the younger with a basket of vegetables balanced on her head.

It is also apparent that the fourteenth century had already invented the hooded anorak, as worn by the fair-haired man who seems to be examining a pair of shoes, rather than one of the suits of clothes which are being made behind the counter.

Scholars have shown that there are iconographic prototypes for most of the groups in the streets, either in the Labours of the Months, or in the activities of the so-called ‘Children’ of the Planets, but it still needs to be said that the total effect is convincingly true to life—and it is truth to life that I would want to stress first and foremost in the representation of the group of dancers.

The first point to make is that, despite the length of their robes, the dancers are young men: this has only become clear in recent years, thanks to a closer study of their footwear, their costumes, and above all their hair style, which is exactly like that of the young St Martin in the previous lecture. They are performing a ‘round-dance’—known as a ‘carole’ North of the Alps, or, in Italy, as a ‘ballata’—in which the whole group dances round in a circle, usually while singing the refrain between the short stanzas sung by a soloist (dressed in black), with the rhythm being tapped out on the tambourine held by the singer.

I feel pretty sure that the actual figure of the dance would have been recognised by a contemporary. When I think back to the playground of an Essex Elementary School in the 1940s, I seem to see a hint of the ‘In and Out the Windows’ section of the ‘Farmer Wants a Wife’ (and in one pair, even the ‘Here comes a chopper to chop off your head’ from ‘Oranges and Lemons’).

(In one of his articles on Lorenzetti, Quentin Skinner has adduced a number of relevant texts to show that men did regularly dance the ‘tripudio’, a virile dance in triple time, both as a sign of celebration or victory, or simply as a healthy way of banishing melancholy or depression. He observes that the dancers’ garments are tattered, literally eaten by the moths and worms; and he shows that at this time, moths (which are mentioned frequently in the Psalms and prophets) were interpreted as symbols of sickness, depression and accidia, for which dancing was a remedy.)

However, there is far more to the group than social realism or sharp observation. The dancers carry the burden of the argument in this half of the fresco. They are larger in scale than the workaday people around them (as are the main figures on the north wall); the system of perspective opens out from them as the walls diminish equally away from the centre; and if you examine the pattern of shaded planes on the walls, you will find that the directed light emanates from the dancers, or, at least, that the source of the unifying light is close to where they are.

What we are seeing, then, is a real dance, observed from the life, and, simultaneously, an expression of joy (‘diletto’), a symbol of peace and security, a source of ‘gloria’ (meaning claritas), and, above all, a symbol of the movement of many minds in concord. The ‘holy virtue’ of Justice, you remember, ‘moves many minds to unity’; ‘questa santa virtù…induce ad unità li animi molti’.

There are other groups on the streets and in the shop fronts, but I would like to end by dwelling on the buildings of the city, which are clearly modelled in style architecturally on those of Siena itself.

These are Ambrogio’s greatest and most personal achievement as an artist. No earlier medieval artist had ever rendered buildings so convincingly, or on such a scale before, capturing the pink brickwork, the characteristic Gothic windows (the Nine had ordered that every building facing the Campo should have windows of this type, without balconies), the projecting eaves, a church façade, another façade higher up the hill, and, dominating the skyline, the towers of the nobility.

Closing in, we can see the tilers at work on a new roof, with their labourers carrying up the materials. And a final memorable detail combines the intimate and the grand: a balcony, with three children who are craning over to see the martin or swallow returning to its nest below, while above them rise the unmistakable cupola and the black and white marble of the campanile of Siena Cathedral.

I remind you of the closing words of the stanza underneath the parable of Justice and Peace on the opposite wall: ‘Through this, there follows, without warfare, every effect of civilised living—the useful, the necessary and the delightful’, ‘ogni civile effetto, / utile, necessario e di diletto’. And I conclude by transcribing the long lines of straggling capital letters which appear beneath this fresco.

Once again, properly arranged, the words prove to form the stanza of a regular canzone with the same rhyme scheme as its counterpart. (The text of the poem, as before, has been conservatively standardised).

With its echoes of Dante, the Book of Wisdom, Aristotle, and Brunetto Latini, it offers a perfect envoi to the lecture.

Volgete gli occhi a rimirar costei,

voi che reggete, ch’è qui figurata,

e per su’ eccellenza coronata,

la qual sempre a ciascun suo dritto rende.

Guardate quanti ben vengon da lei,

e com’ è dolce la vita e riposata

quella de la città dov’è servata

questa virtù, che più d’altra risplende.

Ella guard’ e difende

chi lei onora e lor nutrica e pasce.

De la sua luce nasce

el meritar color c’operan bene

ed agl’ iniqui dar debite pene.

You who govern [Podestà, defenders & ex officio members]

turn your eyes to look at Justice

represented here and crowned for her excellence,

she who gives everyone his due.

See how many good things come from her,

and how sweet and tranquil is the life

of the city where this virtue is preserved,

the virtue that shines out more brightly than any other.

She protects and defends those who honour her

and feeds and nourishes them.

From her light there derives

the rewarding of those who do good deeds,

and the giving of due punishment to the wicked.