Signorelli and Sodoma: The Life of St Benedict

In the last lecture we ended by looking at scenes from an altarpiece from the 1440s telling the life of St Anthony Abbot, which was commissioned by the Martinozzi family for a community of Augustinians in the contado.

We move on fifty years now, to the 1490s, to enjoy a cycle of frescos telling the life of an even more important figure in the history of Western Monasticism—one of the ‘Founders of the Middle Ages’—which were executed for a community of Benedictine monks in a monastery lying a little more distant from Siena, which had been founded by a member of the Tolomei family.

(Religious vocations were by no means confined to the lower or middle classes. Many of the sons and daughters of the nobility renounced the world and worldly possessions, as St Anthony had done, and entered monasteries or convents. And some of these institutions became prosperous and comfortably appointed, thanks to the ‘dowries’ brought by the novices, and to continuing ties with leading families in the city.)

The institution which concerns us is the Abbey of the ‘Mount of Olives’—in Italian, ‘Monte Oliveto’—which came to be known as ‘Monte Oliveto Maggiore’, to distinguish it from other smaller communities of the same name.

It lies a good twenty miles south of Siena, in a rather desolate area known as ‘Le Crete’, because of its chalky-clay hills which are very reminiscent of Ambrogio Lorenzetti’s vision of the contado, as you can see in this photograph of the Abbey in its natural setting.

The courtyard has become a major tourist attraction because, running right round all four walls of the lowest cloister, there is one of the most extensive fresco cycles to be found anywhere in Italy. (Indeed, the cycle is so long and so full that, rather against my principles, I shall pass over half a dozen scenes in order to match the proportions of the other lectures in this series.)

The thirty-six frescos tell the story of the life of Saint Benedict, because Monte Oliveto is a Benedictine Abbey, where the monks live under the Rule—regula—drawn up by this admirable man at the beginning of the sixth century. What you see in the first fresco here—symbolically, not realistically—is Benedict giving his Rule to Bernardo Tolomei in the year 1319.

Sociologists and cultural historians often talk about the ‘Protestant work ethic’, but it is important to keep in mind that—a thousand years before the Reformation—Benedict had already invented the ‘Catholic work ethic’. His communities were to be self-sufficient. The Regula laid it down that those who wanted to devote their lives to the service and worship of God should not only ‘pray’, but ‘plough’. Hence his ethos could be enshrined in the single command: ora et ara.

Mercifully for posterity, the fragile pen—pinna means ‘feather, quill’—was ranked equal with the ploughshare (for ‘the Seed shall swell in the furrow / and the Word shall thrive in the line’).

Among the many tasks he assigned to the monks was the faithful copying of manuscripts, to be written in indelible ink on imperishable vellum and bound in sturdy leather codices (of the kind you can see in the fresco). The scriptorium became perhaps the single most important workplace in any monastery; and we owe more to Benedict than to any other individual for the conservation of Latin literature, history, philosophy and theology.

I will not poach on the story to be told by the artists in the cloister, but perhaps I ought to throw in a preliminary handful of historical facts and hint at the historical context.

His birthplace was Norcia. He founded his first community near Subiaco, thirty miles east of Rome. The Abbey of Monte Cassino, which became the mother house, lies about eighty miles south-east of Rome.

The date of his birth is probably more important than the place.

He was born in 480, which means that he lived in the years immediately after the final collapse of the Roman Empire in the West, at the time of the first Germanic invasions.

The abundant details of his life are taken from a biography written by Saint Gregory the Great, only sixty years or so after Benedict’s death, and Gregory was able to draw on the testimony of four people who had known Benedict personally.

My quotations will come from the medieval Italian translation of this Life, which is also the source of the inscriptions (or descriptions) below each fresco in the cloister.

The Abbot of Monte Oliveto in the late 1490s came from north of Milan, and his artistic taste was relatively sophisticated.

He avoided the still backward-looking painting of the native Sienese in favour of Luca Signorelli, who had been born in neighbouring Cortona and had worked in many important centres in Italy, including the Sistine Chapel in Rome.

Signorelli began work on the cycle in the summer of 1497.

He proved to be a very good choice indeed; but, alas, after he had frescoed the West Wall—beginning half way through the story of Benedict—he was lured to a more prestigious commission, the famous Last Judgement in the cathedral of Orvieto, and he never returned.

It was not until 1507 that the monks secured the services of Giannantonio Bazzi, who had recently come to Siena from the North.

He was clearly a delightful eccentric—he is pictured here with his pet badgers, wearing the coat of a nobleman who had become a monk, for which he paid the exorbitant sum of thirty five gold ducats—and he had the nickname of ‘scatterbrain’ or ‘madcap’—‘il mattaccio’. He was more usually known, however, by another nickname, sometimes written as ‘Sógdona’ and ‘Sódone’, but most often as ‘Sodoma’. (There is, apparently, no more reason to ‘interpret’ his name than there is in the case, for example, of Anthony Trollope.)

As an artist, he is not perhaps one of the immortals, but reputations can change. It is fascinating to learn that, in 1508, Raphael painted Bazzi’s likeness next to his own self-portrait and not far from the architect Bramante. (They are all among the spectators on the extreme right of the fresco known as the School of Athens). It is an affectionate portrait; and it is relevant to notice that he is wearing the same expensive cloak!

He was most certainly a highly competent narrator. He used the established pictorial language of the early sixteenth century, together with some delightfully realistic touches in the fifteenth-century style, to tell a good story very well indeed. Hence, for the rest of the lecture I shall give you hardly anything except story.

The caption written under the first narrative scene reads: ‘How Benedict left his parents’ home and went to Rome to study’.

It is almost as long as the relevant sentence in Saint Gregory’s Life, and it tells us virtually all we need to know.

The town in the distance is his birthplace, Norcia. The lady in red, riding side-saddle on a mule, is Benedict’s devoted nurse, called Cirilla.

The lady standing in the foreground must be his mother, bidding her son farewell; while the little girl, who is being ‘worried’ by the puppy, is probably his sister, the future Saint Scolastica.

Since there is nothing remarkable in the story, I shall make explicit a few obvious points about the pictorial conventions, most of which will remain true for most of the scenes throughout the cycle.

The real architecture of the bay is helped out by fictive architecture, including the foreshortened rosettes—indeed, in photographs, you cannot always tell where the real architecture ends and the fictive architecture begins.

The horizon is at a comfortable height, more than a third from the top, so that there is a good deal of nicely graduated sky. The landscape is conventional but convincing, with an apparent depth of several miles. (This could be taken for granted in paintings from the first decade of the sixteenth century). Notice how the river guides the eye inwards; and notice, too, the aerial perspective obtained by the use of subdued greens and browns in the middle and foreground, fading to blue in the hills.

The hillside town in the distance is rather schematic; but within its low wall it contains all that is needful: dwellings for burghers and towers for the nobles; a parish church as well as a cathedral; a castle—and a corpse swinging from the gibbet.

Against this very light background of sky and countryside, the main actors in the story are—as so often—arranged in a frieze across the foreground. All of them, from the father on the left to the groom on the right, are dressed in contemporary costumes in strong bright colours.

The simple narrative could not be clearer, the group being dominated by young Benedict in the centre, who twists round on his saddle to say goodbye to his parents, fully at his ease on the sculpturesque, bay stallion as it rears up, impatient to be off.

The facial types are conventional, even vapid—very reminiscent of the faces and expressions one finds in the dominant art of Perugino and his pupil Pintoricchio. Indeed, this face, this horse and this servant are lifted ‘verbatim’ from a fresco by Pintoricchio which we shall look at in the final lecture. (He, in turn, had borrowed them from a drawing attributed to Raphael.)

The second scene is painted on a slightly convex surface, to which, obviously, the camera is not doing justice at the edges.

The fresco includes a glimpse of a landscape with the river Tiber. In the centre, you see a classicising loggia, with a coffered ceiling, strikingly foreshortened in accordance with the principles of Albertian perspective (as noted apropos of the frescos from the 1440s in the Ospedale at Siena).

This is the schola where Benedict went to hear lecturae (read by the bearded magister, enthroned on his cathedra) along with students of his same age (including a self-portrait of Sodoma, flaunting his coat!)

Seeing, however, that ‘such worldly studies were vain’, and that his companions were given to ‘lascivious vices’ (this explains the cupids above the loggia), Benedict abandoned school and ‘drew back the foot he had set in the world’—this being the moment which Sodoma captures so charmingly on the right, where Benedict is identified by the same stylish outfit he was wearing on his departure from Norcia.

The next fresco shows us Benedict’s first recorded miracle—a charmingly domestic one—which takes place in the room to the left.

Cirilla the devoted nanny, still dressed in red, had borrowed a wooden tray which was used to sieve the grain (you can see chickens ‘gleaning’ grain on the floor). However,

‘leaving the tray incautiously on the table, it fell and broke in pieces. At which she began to cry very loudly, especially as she had borrowed it. The young Benedict felt sorry for her, took the broken tray, knelt down to pray, and, rising, found the tray was made whole’ (‘bello e saldo’).

This useful little miracle greatly impressed the local inhabitants (in the foreground, right), who hung the miraculous tray over the door of their church, as you can see in the detail.

There it remained, according to Gregory, until the coming of the Longobard invaders.

(One might be forgiven, perhaps, for not realising immediately that the vast classical temple in the background was intended to represent the church in Affíle, a village not far from Rome.)

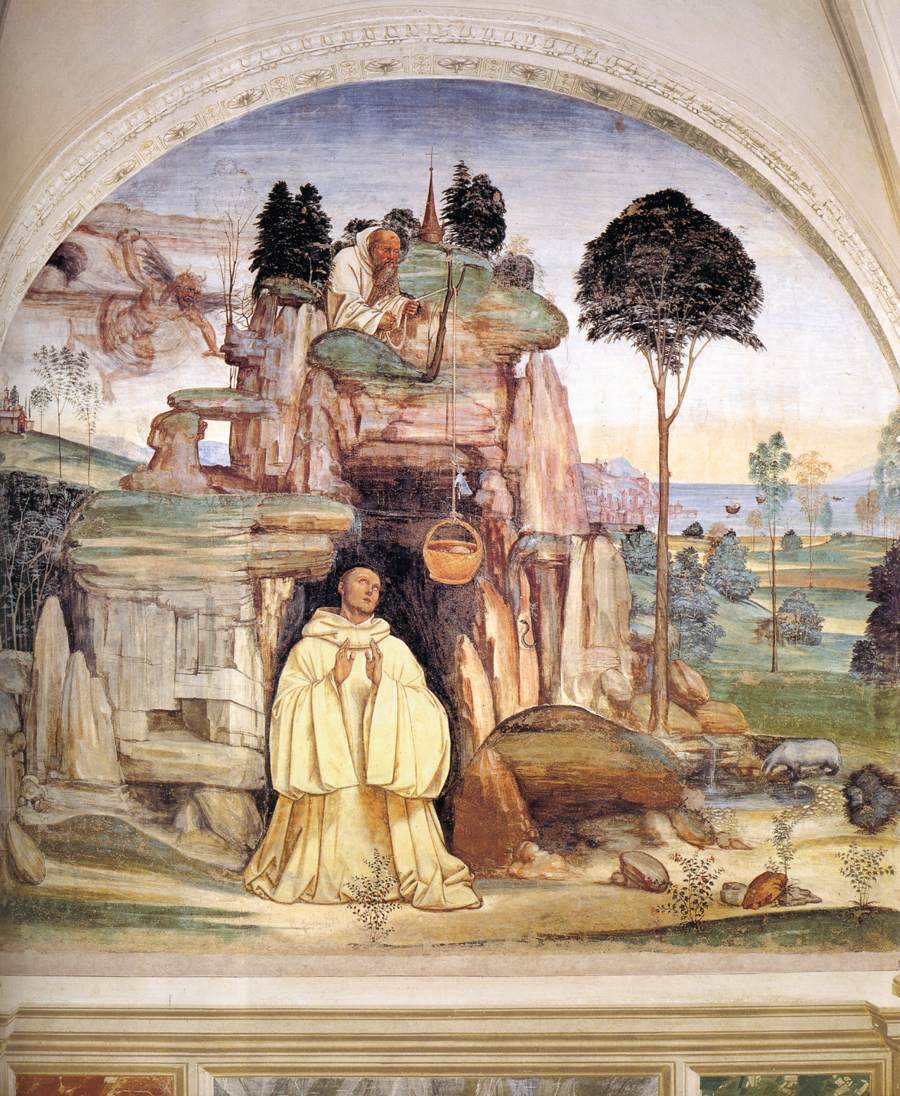

The next group of scenes deal with the three-year period when Benedict became a hermit—a ‘monk’ in the original sense of the Greek word monachos, meaning someone who lives ‘alone’.

The first need not detain us long.

The landscape on the convex wall represents—with a little goodwill—the wild country near Mount Subiaco, lying to the east of Rome.

In the background we see the young Benedict (very small in the distance) advancing into the wilderness, having grown tired of the attentions of the local people.

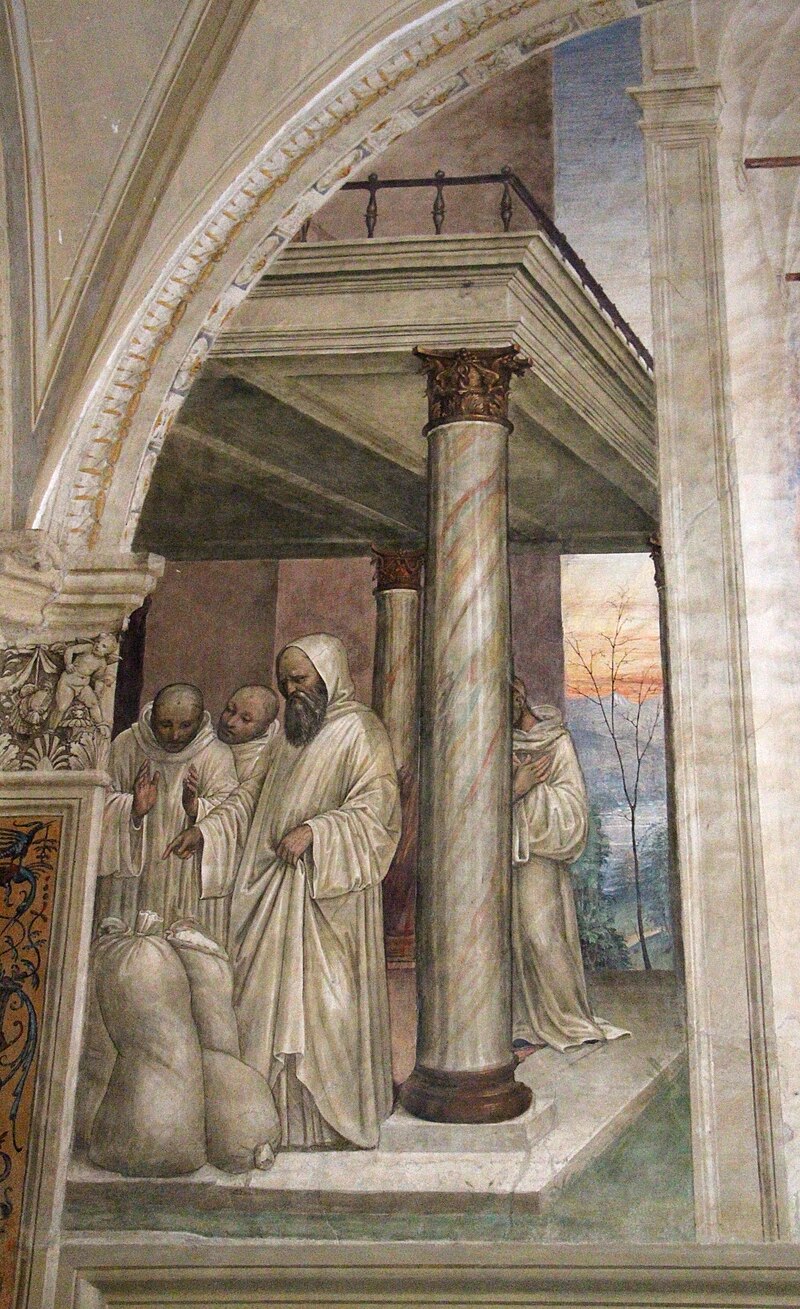

In the foreground he has met by chance a monk called ‘Roman’, ‘Romano’, who having questioned him, clothed him in the religious habit, which Benedict is kneeling reverently to receive, having left his own coat in a bundle on the ground. (The new garment, by a pardonable anachronism, is the full white habit worn by the Benedictines.)

Benedict took up residence in what is supposed to be an inaccessible cave at the foot of a precipice. (Sodoma throws spatial realism to the winds in favour of earlier pictorial conventions which were not concerned with a common scale for all objects and people in the same frame.)

His friend, Romano, would save up bread from his own daily ration and bring it to Benedict secretly, lowering it down from the cliff top in a basket on the end of a rope (as you can see in the detail) which had a bell attached to the end, in order to alert the hermit that his supper had arrived.

The devil, however, ‘grew envious’ (you can make him out, top left); and ‘one day he threw a stone and broke the bell’, so that poor Benedict ‘no longer knew of the arrival of his loaf’.

The consequences might well have been serious, as we gather from this next fresco, which is painted on either side of a window embrasure (the window is ‘real’ architecture).

A priest had prepared a substantial meal to celebrate Easter Day.

(The detail shows the scene in the kitchen, where you see the table set out for the meal, the boy stirring the soup, and the dog waiting his share expectantly.)

However, God appeared to the priest (that is why he is shading his eyes from the divine effulgence), and said: ‘You have prepared a fine spread (‘grandi delizie’) while my servant Benedict is starving in the desert’.

So the priest rose immediately, and after a long search, he found Benedict, prayed with him, and then, ‘invited him to eat, as it was Easter Day’.

At first Benedict demurred, since he had lost all count of time and thought the Priest was merely using a figure of speech, but then—as you can see in the group on the left—‘he sat down and ate’. (Look how carefully the boy is pouring the wine.)

Jumping over one scene, we come to the story of how Benedict, like St Anthony before him, was visited by ‘unclean thoughts’.

One day, we read, ‘the Adversary came in the form of a small black bird’ (in Italian, ‘merlo’ or ‘merla’), ‘which kept flying about and into Benedict’s face, until he made the sign of the cross, at which point it flew away.’

(Sodoma’s bird is difficult to see against the rock of the hermit’s cave; but the gesture is clear.)

The bird reminded the saint of another ‘bird’—that is, a girl whom he used to know called Merle (‘Merla’); and he began to be tormented by lust.

However, just as he had reached the decision to abandon his cave and seek out the girl, divine grace came to his rescue, and he felt ashamed.

He stripped off his habit and threw himself naked into a clump of nettles and thorns, and rolled in them until he was bleeding all over. ‘The wounds of the body healed the wounds of the soul’.

His cure drove away all thoughts of Merle (as the artist shows us in the sky where an angel puts the demonised temptress to flight). And Gregory reports that Saint Benedict was never troubled by lust in his life again.

The episode was a popular one in pictorial cycles, as you can imagine, and it is worth looking at this little panel by Niccolò di Pietro, just over three feet high, which was painted about eighty years earlier.

It reminds us yet again of the enormous advances in artistic technique with regard to the treatment of space which had come about between 1420 and 1500.

However, it also reminds us of the greater effectiveness of the medieval conventions in getting to the heart of a religious subject.

In Niccolò di Pietro, there is no distracting ‘Lake District’. The stylised rock is more essentially ‘rock’; the briar patch is more thorny; the forces of Good and Evil confront one another as an angel and blackbird of the same size; and Benedict can be posed in such a way that he reminds us of Adam immediately after the Fall, and thus as being all too aware of his sexuality.

Three years then passed in the wilderness, and Benedict acquired quite a manly beard.

In this scene, some monks from a nearby monastery arrive to entreat Benedict to become their Abbot.

‘For a long time’, we read, ‘he refused, and told them that, considering their way of life, he was not the leader that befitted them. But in the end he gave his consent’.

In the distant background, Benedict duly accompanies the monks to their own church, which lay between Subiaco and Tivoli, in the same kind of landscape.

(The detail reveals Sodoma’s superbly impressionistic skill as a painter on wet plaster: you can almost hear the confidence and speed of the brush strokes.)

The next fresco (the tenth) depicts two scenes which took place in that monastery.

‘Benedict proved to be very strict in applying the rule; and the monks regretted that they had taken him for their Abbot. One day, therefore, they mixed poison with his wine, and they offered him to drink’.

(The mixing of the poison is shown in the corridor; and the sinister intention of the monks is conveyed in the weasel crouching on the sill.)

‘But Benedict made the sign of the cross over the glass, and instantly the glass was shattered as if it had been struck by a stone’.

(It has now become clear how important the characterisation of the big-nosed ringleader was.)

Benedict forgave the monks most humanely, saying: ‘He had told them that they were not really suited to each other’.

‘Then he returned to his wilderness’ (you see him striding serenely away in the scene on the right of the fresco).

However, his reputation was now such that many people came to join him. Indeed, they became so numerous that he decided to build twelve small monasteries in the region, each of them to house twelve monks.

(The very legible titulus below the fresco says, succinctly: ‘How Benedict completed the building of twelve monasteries. )

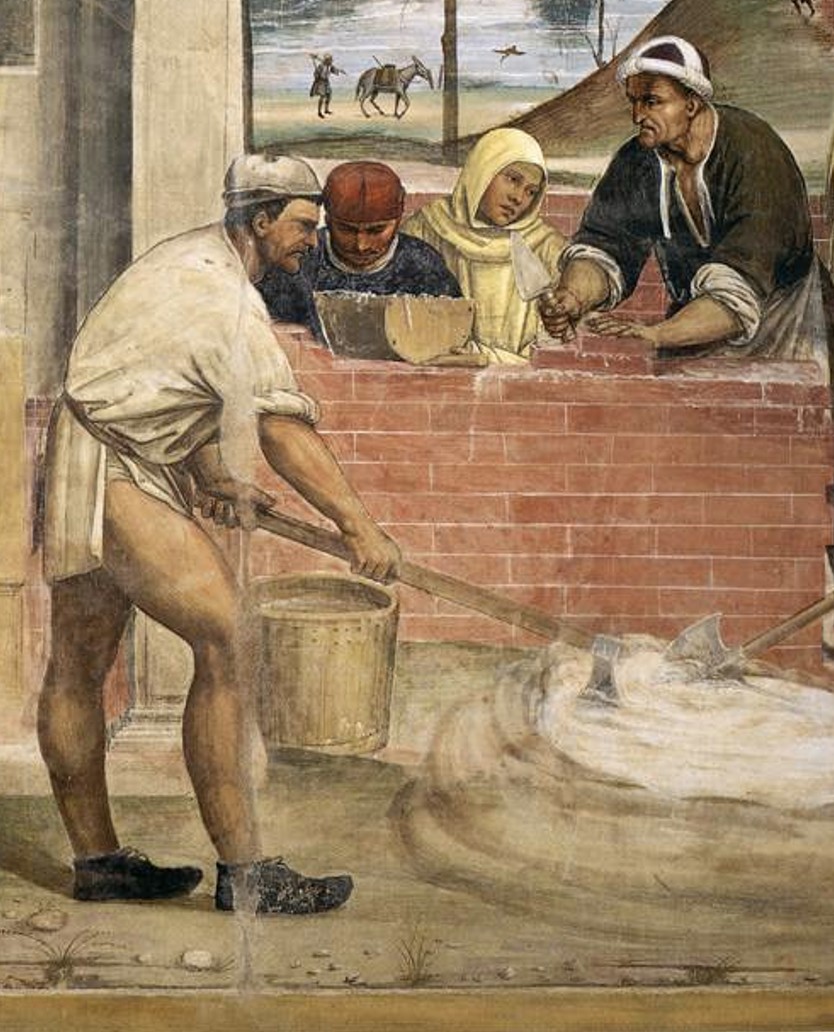

You may think the monastery under construction would be a little on the large side for twelve monks. But we can rejoice in the lack of narrative realism because the numerous details offer some very rewarding social realism in their close observation of a Renaissance building site.

Benedict, bearded, Is clearly in charge of things, as the architect. A diminutive painter with a long-handled brush whitewashes the vault of the arch. Stone-layers (top right) are laying the cornice. A tradesman perches on his scaffolding, plastering the vault (a wonderful feat of draughtsmanship).

We turn another corner in the cloister now to reach the twelfth fresco, which lies on the East Wall.

The scene is extremely crowded and animated (and Bazzi actually got paid extra for the work involved), because the whole point is that Benedict’s reputation for sanctity continued to grow, so that more and more people flocked to join his communities—or, at least, they sent their sons to be educated there, treating the monasteries as a kind of boarding school.

Of these ‘boarders’, the most notable were to be Mauro and Placido, who are prominent in most of the following scenes, and who were both to be canonised in their turn.

They are the two boys being received by Benedict on the left.

Once again, it is worth breaking off and looking at another version of the same episode in order to measure the vast gap between the conventions of the year 1510 and those back in 1420.

This tiny panel, just twelve inches tall, now in the National Gallery, is by Lorenzo Monaco.

Lorenzo retains a medieval, shallow ‘stage set’, flanked on the right by a stylised treatment of the cliff.

He shows only a dozen figures in all, closely overlapping, all of them monks. Placido and Mauro are already wearing their Benedictine habits, and they are already identified by haloes.

The mood of the picture is suitably solemn and devout, and it is also a breathtakingly beautiful study in the deployment of creams and gold.

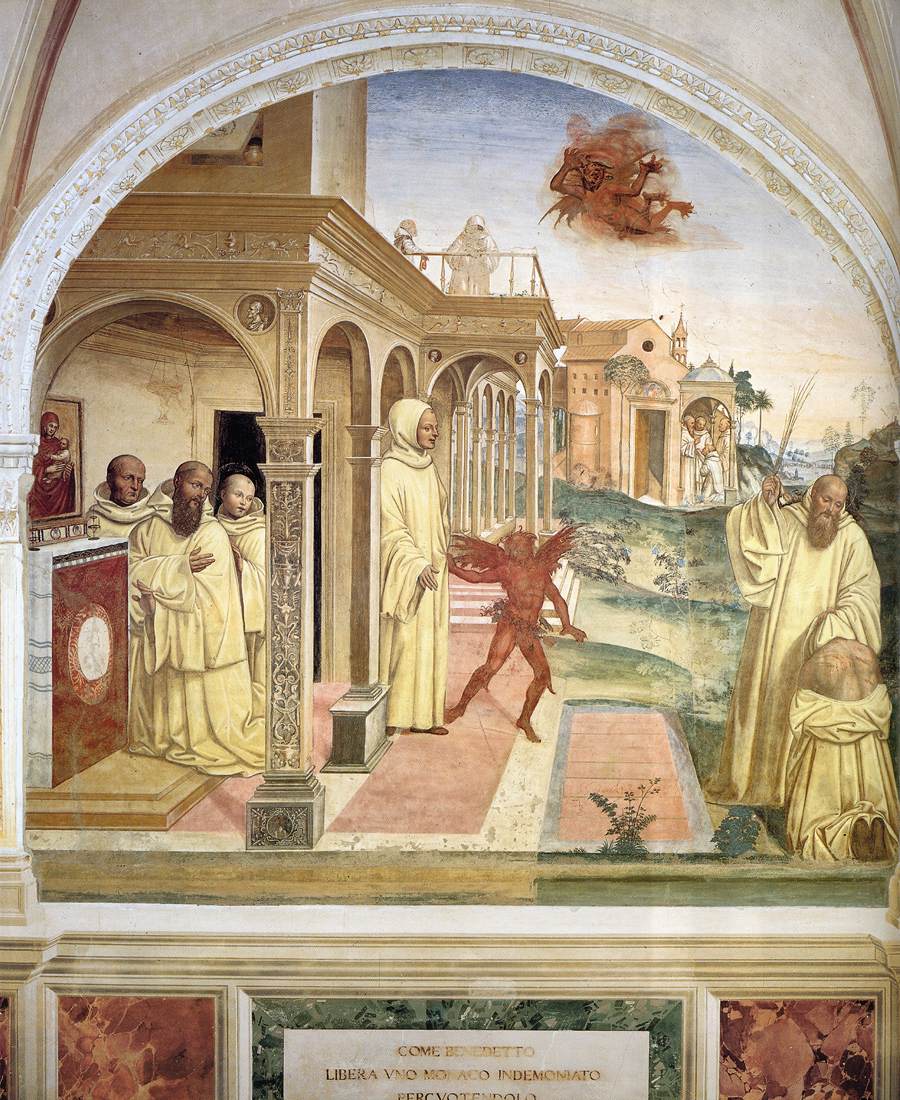

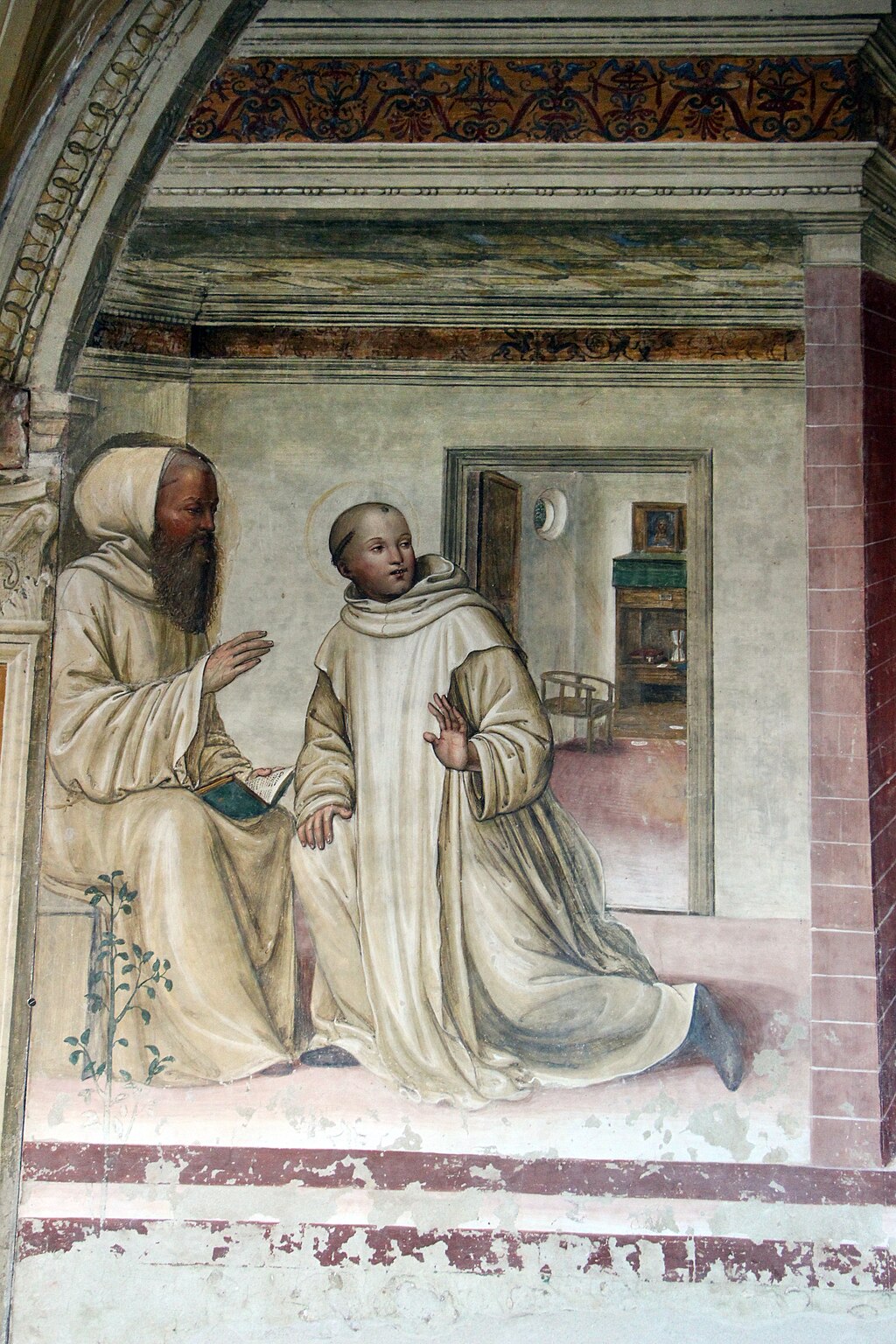

The next scene shows Benedict as a kind of Victorian headmaster, or perhaps better, a ‘school inspector’, for this story is taking place in another of the twelve monasteries—no less grand in scale and architecture than many English boarding schools—where Benedict had been called in by the Abbot to deal with a young monk who was persistently playing truant when he should have been with the others at prayer.

Benedict came and observed, and he saw that the youth was actually being led outside by a ‘small, very dark skinned boy’, who had caught hold of the monk’s habit.

The Abbot, and young Mauro, could not see the devilish ‘boy’. But after they had prayed for two days (in front of the altar and the altarpiece, as pictured), Mauro, but not the Abbot, also became able to see the Devil in his disguise.

Benedict then took a rod and chastised the youth, thereby curing him of his truancy once and for all.

Saint Gregory reports that the Devil felt that he himself had been beaten by Benedict’s rod; and this is what Sodoma depicts in the sky.

In short, it is a scene of exorcism by beating.

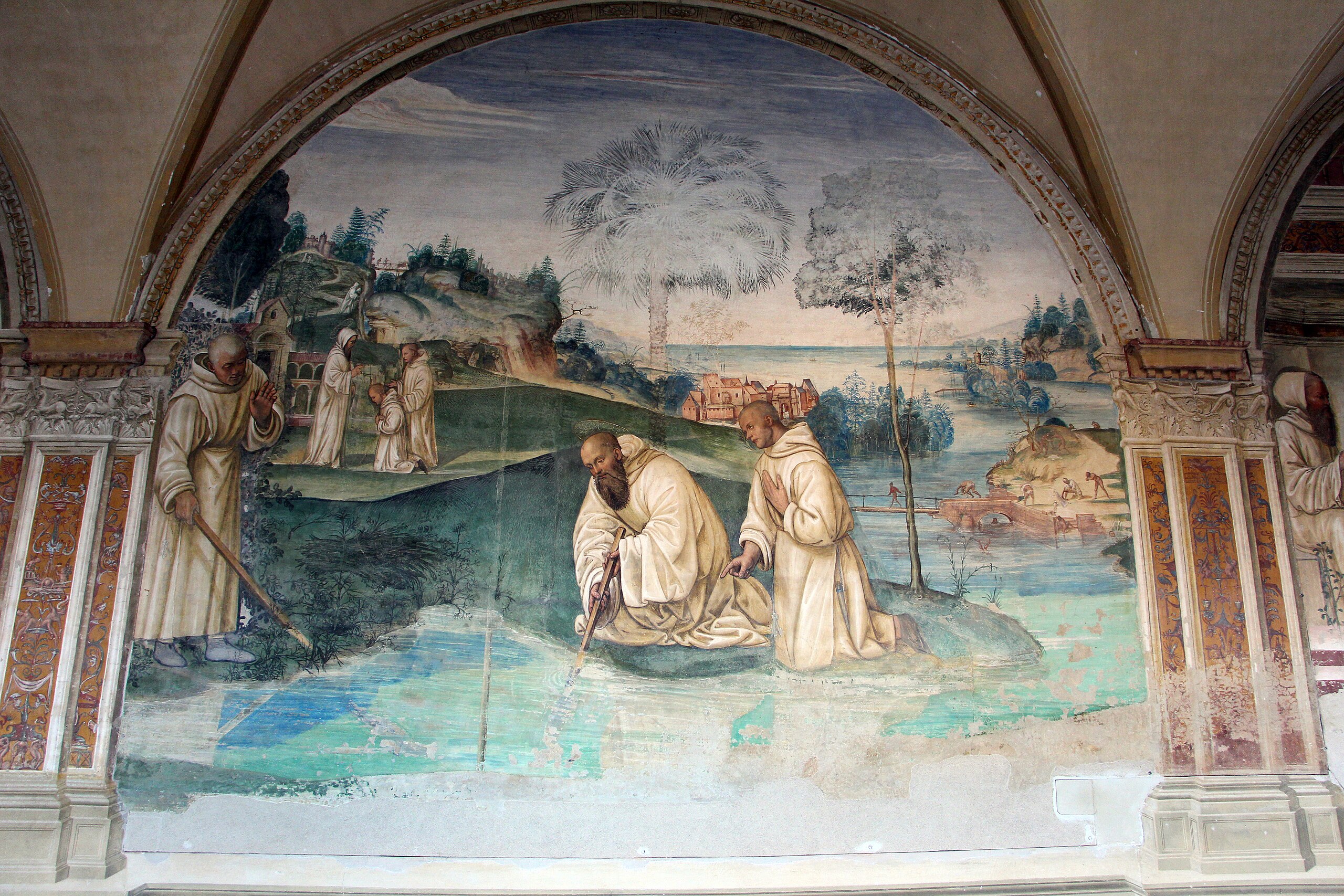

From a monastery with a problem of discipline, we come to three others with a more fundamental problem—lack of water.

They had been built on the top of a steep mountain, with the result that the poor monks had to come down the mountain to the lake every day, and carry their water back up.

They therefore formed a joint delegation to ask Benedict for permission to rebuild on a more convenient site. Benedict received them sympathetically, but sent them off without any decision. (This is the foreground scene.)

That night, he climbed the mountain secretly, accompanied this time by Placido, and he prayed for a long time.

He then set up three stones in the ground as a sign.

When the monks came again to hear his verdict, he told them to go and dig where they found three stones ‘one on top of the other’. They did so, and immediately a spring of water began miraculously to flow’ (as is vividly illustrated in the detail).

‘The spring’, adds the author, ‘is still running down the valley to this very day’.

The problem of the first group of monasteries, had been that of insufficient water.

The next two episodes hinge on their being too much water in the vicinity of Benedict’s own monastery—far too much water, as you can see clearly in the detail, offering a charming scene of people stripping off for a dip, with one man in the very act of diving into the lake from the bridge.

The story here is one of Benedict’s trademark, domestic miracles, rather like the one involving the broken tray in Affíle.

A Goth had been converted and taken on as a lay brother. One day, while he was clearing undergrowth near the lake, the blade of his bill-hook flew off and disappeared into the deep water. He was very upset, and he came first of all to Mauro, who reported the loss to Benedict.

Instead of ‘putting him on a charge’, Benedict came to the lakeside, together with Mauro, dipped the handle into the lake, and immediately the blade flew back on.

Mauro and Placido are both involved—this time as protagonists—in the next scene, on the marge of the same lake.

One day, Placido was drawing water from the bank when he slipped and fell in, and was carried away by a current ‘a bow shot and more’ from the shore.

Benedict was in his cell, but he saw the accident in a vision and ordered Mauro to go and rescue his companion.

Mauro delayed only long enough to ask for Benedict’s blessing (you can sense his urgency), and then—‘Mirabile cosa’, ‘unheard of since Saint Peter’—Mauro walked on the waters of the lake as if he were on dry land, seized Placido by the hair (what little the barber had left him), and brought him safely back to the bank again.

The next three scenes deal with successive plots by a local priest called Florentinus (I shall Italianise him as Fiorenzo), who had grown envious of the saint’s reputation. They demonstrate Benedict’s remarkable mildness with his enemies and persecutors.

Fiorenzo tried a campaign of slander, and having failed, his next move was to try to poison Benedict.

His chosen vehicle was not wine but a loaf of bread, which he hands to his servant (in the scene in the left background). The servant (in the bright colours of his sixteenth-century costume) brings the loaf to the monastery (middle ground), where Mauro carries the gift-offering to the dinner table (on the right).

Benedict is diplomacy personified.

He was in the habit of feeding a raven every day, so he spoke to the raven (just as his fellow Umbrian, Francis of Assisi would later do) saying: ‘In the name of our Lord Jesus Christ, take this bread and carry it off to a place where no one will ever find it.’ The raven spread his wings, opened his beak, and walked all round the bit of bread, cawing, as if to say ‘I would like to obey you but I am afraid.’

Eventually, he was coaxed into obedience, flew away, and returned only after fully three hours had passed, when Benedict gave him his usual portion. (You can see the raven below the figure of Mauro.)

Having failed to destroy the body of the saint, Fiorenzo ‘resolved to kill the souls of his followers’.

To this end, he sent seven young women to dance in the monastery garden, and thereby to inflame the monks to ‘fleshly desire’.

Benedict saw the scene from his cell (Sodoma places him on a balcony). Realising the danger, he decided that the time had come for him to leave this region, taking with him his closest followers (you can see Mauro and Placido in the group on the left), who all avert their gaze from the young women.

At this point, however, the Lord intervened, because while Fiorenzo was at home rejoicing at the success of his stratagem, the beam on which he was standing collapsed, and he was killed.

Mauro ran after Benedict, who had got no further than ten miles away, to tell him the news and to urge him to return.

Benedict, we are told, wept bitterly on hearing of the death of his persecutor; and imposed a severe penance on poor Mauro, because he had shown gladness at the news he had brought.

The artist shows not only the collapse of the beam but also the immediate cause of that collapse, by imagining an SAS-style attack from the air by four devils.

Look closely at the detail. These devils are powerfully muscular and sculpturesque. Their varied poses provide the occasion for some virtuoso feats of foreshortening. Their energy and demonic glee are quite unlike anything we have seen thus far.

This is because the artist is no longer Sodoma. We have in fact turned another corner in the cloister to reach the West Wall; and this is the area that had been frescoed by Signorelli back in the summer of 1497.

The same strength and vigour is to be found in the following scene—which takes us on to the most important period in Benedict’s life.

He left Subiaco and travelled south-east to the area near Cassino because the province had relapsed into paganism, and specifically into the worship of Venus and Apollo.

The three future saints are impressively monumental in their voluminous white habits as they stand above the clearly reluctant congregation on a simplified mound. And they are well differentiated psychologically (Benedict ticks off his reproaches on his fingers; Mauro holds an hour-glass to ensure the sermon does not go on too long; Placido makes a sweeping gesture and turns his head aside in displeasure).

But Signorelli comes fully into his own in the scene in the background.

As you can see in the splendid detail, seven monks are taking a more vigorous approach. They are using ropes and a great beam as a lever, in order to tear down a statue of Apollo in a pagan temple. Notice especially the figure who has leapt up onto the pedestal to use his broom handle as an additional lever.

It was on the site of this very temple that, in the year 529, Benedict began to build a church that would become the famous Abbey of Monte Cassino, the mother-house of the Benedictine order. (It was almost completely destroyed in some of the bitterest fighting in the last war but has now been rebuilt.)

In the next pair of scenes, the construction of this immense abbey brings Benedict into renewed conflict with the Devil himself.

One day, a group of monks tried to lift a huge stone that would have been useful for the building—but it was as if it were ‘rooted to the ground’. They realised that the Devil must be sitting on the stone—you can just make him out despite the flaking of the paint—and they called in Benedict to exorcise him with a blessing. After the blessing, they could lift the stone as if it had no weight. (This is the foreground scene.)

The saint then ordered that they should dig down in the place where the stone had been.

Signorelli places this scene in the background. The detail shows what they discovered. A bronze idol had been buried underneath; and it is the head of the idol that the monks are lifting out of their pit.

The story continues In the dynamic scene in the middle ground of the fresco, on the right.

By chance, we are told, the monks happened to fling the excavated statue down into the kitchen, which then seemed to catch fire. ‘While they were throwing water and causing an uproar, Benedict came and recognised that the blaze was a pure illusion’.

He prayed, with his usual success, that the monks would recognise it as no more than an ignis fatuus, a will o’ the wisp.

After the failure of obstructionism and of illusionism, the Devil tried more active means to hinder the work of building.

He caused a wall to collapse—by giving it a hearty shove, as you see—sending a young monk flying to the ground and killing him.

Three of his fellow monks brought the body to Benedict (according to Gregory, they had to put the mutilated and crushed bits into a sack), and Benedict was moved by this challenge to give the supreme proof of his sanctity, praying so fervently that the young man rose from the dead, and was sent straight back to work!

There were no further interruptions to the building of Monte Cassino.

At this point we can allow ourselves another little digression to draw comparisons with an earlier interpretation of the story—a fresco from the 1380s, executed by an artist called Spinello, who came from Arezzo and is therefore known as Spinello Aretino.

If you cross the Arno at Florence, and climb up the steep steps to the church of San Miniato, you will find in the Sacristy eight scenes from the Life of Benedict, of which we shall glance at two.

In the first, you will instantly recognise three moments in the episode of exorcism by beating; and you will notice how the arches of the painted building (so typical of the conventions of the late fourteenth century) are used to articulate the action with much greater clarity than in Signorelli.

The second shows Spinello’s version of the scene we have just examined at Monte Oliveto Maggiore.

The limited range of the subdued colour scheme is in itself particularly striking: a hint of blue and green in the trees and devils, the merest touch of red for the tiles and roof beams and the clothes of the labourers, but otherwise the white robes of the Benedictine order are echoed everywhere—in the ground, the building, and the stylised rocks.

The devil does the pushing, as in Signorelli; but we see the result, not the process, with the victim already covered by the rubble.

The linking scene of the carrying of the body is omitted, but the resurrection itself is in the foreground; and where Spinello really scores, from the point of view of clear narration, is in the crouching position of the monk who is being raised from the dead. (You could hardly find a more instructive example of the differences between 1387 and 1497.)

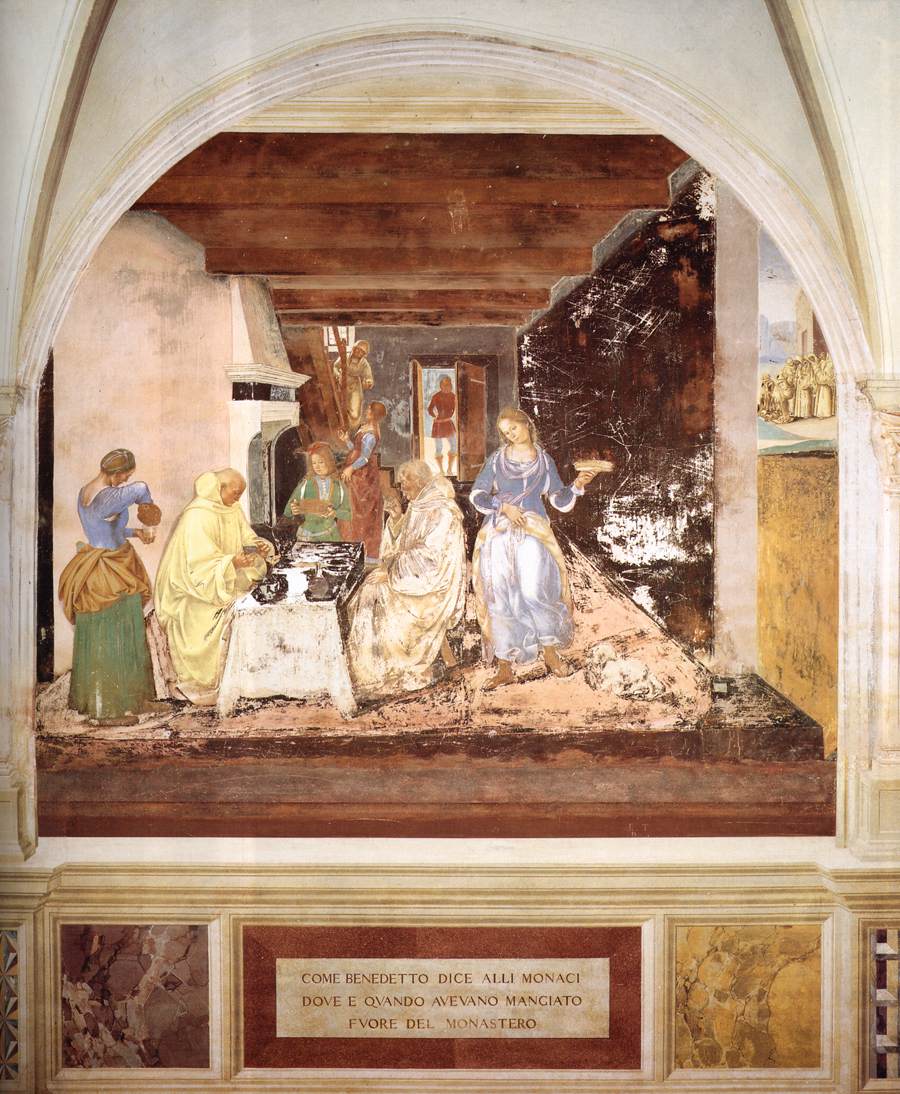

The resurrection of the monk was what you might call a ‘mainstream’ miracle, something rather uncharacteristic of St Benedict, as we are immediately reminded in the next two scenes, which have that homely stamp which is more in his style. They also show his second sight, and his good-natured tolerance in dealing with minor transgressions.

Two of the monks had been outside the monastery to preach and to give counsel. The hour grew late, and they could not resist an invitation to supper given by a religious woman, although there was a strict rule forbidding the monks to eat or drink outside the monastery.

You can see them seated complacently at table (and is a great pity that so much of the paint has either turned black or flaked off).

In the background, the proprietress reaches down provisions, a kitchen wench backs away from the fire, while a man keeps an eye out for the ‘military police’.

One serving girl comes forward, skirt lifted, thighs very visible through her ‘shift’, almost dancing, carrying a plate of food; while the other has tucked up her apron, and pours a good glass of wine, revealing a split under her arm, and with a tell-tale wisp of hair escaping on her forehead. The monk seems to be saying grace with more than usual fervour and expectancy.

The minuscule scene which is barely visible on the right, shows the consequences of the monks’ night out. They returned to the monastery. They failed to confess their disobedience; yet they were told by the saint exactly what they had eaten, and how many glasses of wine they had drunk. However, all ended well—they were ashamed, and he forgave them.

In the next scene (still by Signorelli), the tempter is no longer a serving wench, but the ‘Adversary’ himself, in disguise.

A brother of one of the monks used to visit him once a year, and being a pious man himself, he turned his visit into a kind of pilgrimage, vowing that he would never break his fast while he was on the journey.

Twice the offer was refused, but on the third occasion, temptation was too strong, as you can see in the detail from the background.

No sooner had the man arrived at the monastery and knelt to pay his respects to the Abbot (this is the main scene in the foreground) than Benedict gave further proof of his visionary powers.

‘Brother, what happened?’ he asked.

‘If you could resist the Evil Spirit twice, why could you not be steadfast a third time?’

Benedict’s reputation for ‘second sight’ spread so wide that it came to the ears of Totila, king of one of the Gothic peoples who had invaded central Italy in the years following the collapse of the Western Roman Empire. (Notice the crescent moon on the banner of the ‘infidel’ over the invader’s pavilion, discreetly drawing attention to the menace of the Ottoman Turks in the 1490s.)

Totila came, pitched his camp not far from the monastery, and sent to enquire whether Benedict would receive him. Having received a positive answer, he summoned his sword-bearer, whose name was Rigo, caused him to be attired in his own royal apparel, and sent him off to Saint Benedict with orders to pass himself off as the king. (This is the preliminary scene, relegated to the background, which you can see better in the detail.)

They came into Benedict’s presence, richly dressed and accompanied by courtiers and helmeted men-at-arms, as you see in the foreground. But as soon as the saint saw him, he called out: ‘My son, take off the ornaments you are wearing, for they are not your own.’

At this, ‘Rigo fell to the ground, aghast and terrified that he had set a trap for such a man.’

The next scene in the narrative follows immediately and takes place in exactly the same spot.

Totila himself came to the abbey, accompanied by a throng of horsemen as well as soldiers and courtiers. And in great contrast to the swaggering, aggressive behaviour of his retinue, the king knelt and refused to rise until the saint appeared and raised him with his own hands.

(The twisting torsos of the brightly dressed young knights in the detail show Signorelli at the top of his form; and it will not escape you that even the warhorse curls his nostrils in disdain.)

The two scornful knights and their sniffy stallion must have been the last few square inches painted by Signorelli, so please locate the paired images of the story of the Gothic King, in this photograph of of the West Wall in the cloister, before we turn the corner to resume the narrative through the eyes of Giannantonio Bazzi (who arrived, you remember, fully ten years after Signorelli’s departure).

There are still eleven more frescos on the North Wall, but I will limit my commentary to just two of them (also placed side by side), since it seems appropriate to complete our visit by enjoying two of Benedict’s more characteristic miracles, of a purely domestic kind, which also happen to find the younger artist at the top of his form.

As we pass from the twenty-seventh fresco to the thirty-first, it is important to remember that the Benedictines ‘ploughed’ as well as ‘prayed’, and that they normally expected to be self-sufficient.

One year, however, there was a bad harvest and ‘famine throughout the province of Campania’. Hence the day came when there were no more than ‘five loaves in the monastery’.

What you see in the right half of this fresco is the monks seated at dinner in the Refectory on that fateful day. They are being served by a bare-headed lay brother who is unloading one tiny dish from his tray, while the dog and the cat are disputing one fallen scrap.

(As regards the setting, notice the ‘fresco-within-the-fresco’ on the rear wall, where the Crucifixion is painted on the plaster above a door which remains open to allow the house-martins to fly in and perch on the ceiling ties. And don’t miss the monk who is reading aloud from the scriptures during the meal, as was always required in Benedict’s Rule.)

There is a little wine on the table (although one of the flasks is empty), but the only solid food in sight seems to consists of an artichoke and just three slices of bread—which is why the man closest to us is both clutching his own roll and apparently trying to filch his neighbour’s.

(Notice, however, that the artist has painted ‘two little fishes’ on the table in front of the same monk to bring out the parallel with the story in the Gospels.)

The monks had become very depressed at this point, but Benedict, at the head of the table, consoled them, prophesying that by tomorrow there would be ‘an abundance’.

My second and final choice from the miracles on this wall is also of a highly practical kind; and once again it demonstrates that Benedict could not only see visions, but himself appear in visions to other people—at his will—as a way of communicating with them.

He had nominated a new Abbot and a new Provost, assigned to them to a small colony of monks, and sent them off to build yet another ‘daughter monastery’, in a field near Terracina—which Sodoma sets in another of his typical landscapes, complete with fern-like larches, a river and distant hills.

Benedict promised that on a certain day, when the site had been cleared and prepared, he would come and show them where to build, and what to build.

During the night before the promised visit, he appeared in the dreams of both the Abbot and the Provost (whom we see fast asleep in the same bed).

He brought with him (as you can see) a model of the church; and he gave the necessary instructions.

(Enjoy the delectable realistic details in the bedchamber: the candle and icon on the mantle-piece; the sheepskin coverlet (in Benedictine colour); the hand peeping out; the sandals on the ledge; and a key casting its shadow on the drawer under the bed.)

The two men did not trust their vision. They went to Benedict and reproached him for not coming as he had promised. But he simply sent them back again, to carry out what he knew he had shown them in the shared dream.

The outdoor scene on the right of the fresco represents the ‘substance’ of their dream; and Sodoma supplies some very ‘substantial’, realistic details, based on his close observation of a Renaissance building site (like the one we enjoyed earlier). For example, the shovel with a very long shaft, but without a T-grip at the end, which is being used in the mixing of the mortar, is of exactly the same type as can be seen all over Italy to this day.

A very junior monk monitors the exact amount of mortar under the trowel being used by two very experienced bricklayers.

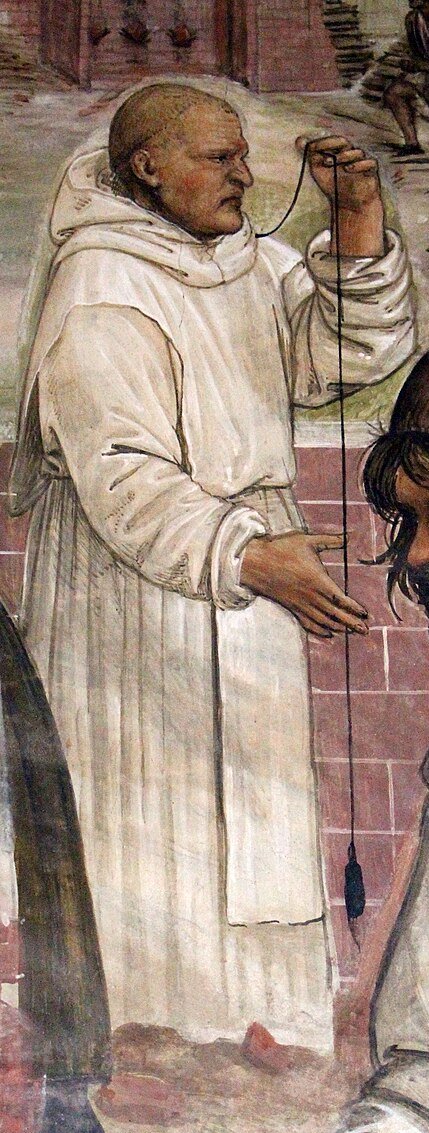

Notice, above all, the more senior monk behind them, and the concentration and care with which he uses his plumbline to check their work.

The detail of the overseer with his plumbline enables me to conclude our tour of Monte Oliveto Maggiore with equal, geometrical elegance by returning to the first fresco in the whole cycle, at the point where we entered the cloister.

A ‘plumbline’ (filo a piombo, in Italian) is a kind of ‘ruler’ (regolo, in Italian).

Benedict’s great legacy was his ‘Rule’ (regola, in Italian).

He was not a visionary. He did not go forth and preach the Word. He was not martyred for his Faith. He did not receive the stigmata.

He used firmness and tolerant common sense, together with his knowledge of human nature at all levels of society, to devise and disseminate a very special kind of good life in a very special kind of large but isolated religious community, which would both survive the downfall of an Empire and preserve its cultural inheritance.

He was the quintessential Abbot, the Abbot par excellence.