Pintoricchio: The Life of Pope Pius II (Libreria Piccolomini)

Our story in this lecture begins in Rome, in the biggest of the five churches dedicated to St Andrew, Sant’ Andrea della Valle.

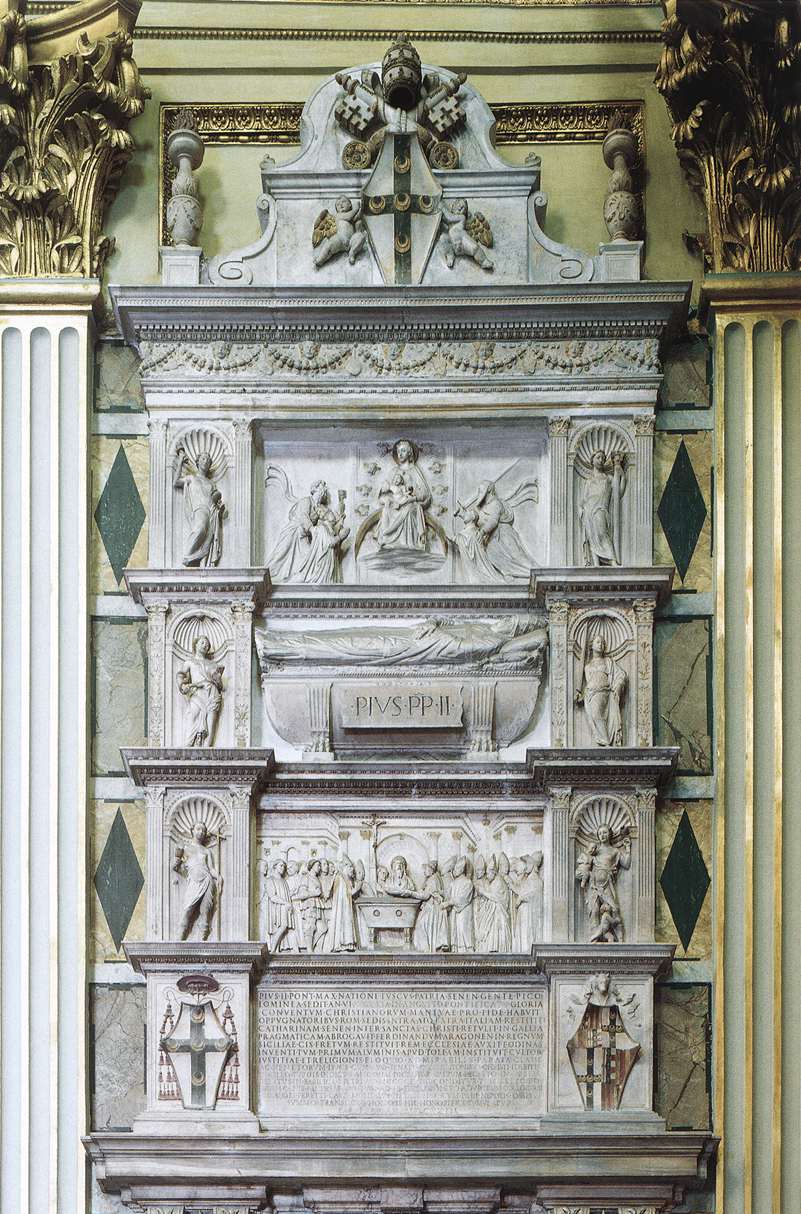

There, high up, on opposite sides at the end of the nave, you will find the ‘look-alike’ tombs of no fewer than two Sienese Popes, uncle and nephew, who both took the names of Pius on their election.

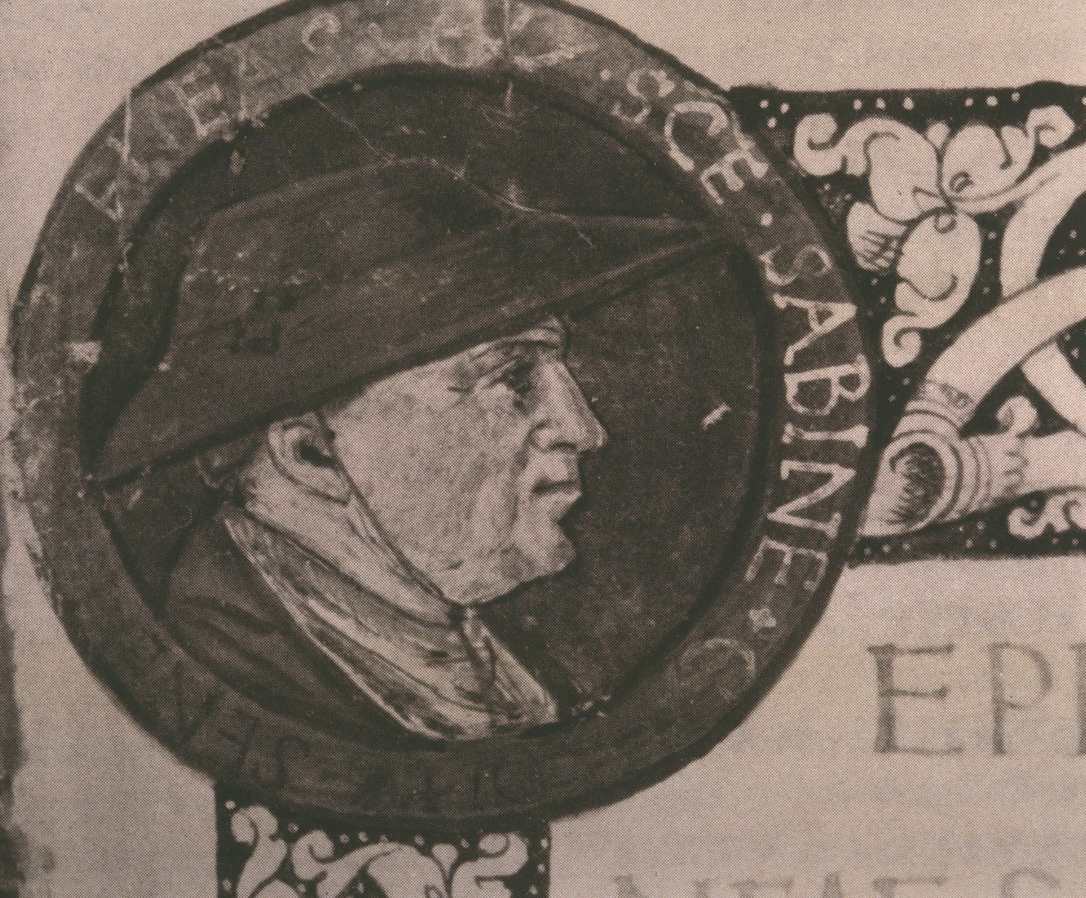

Pius II (whose monument you see here) reigned for six years, while Pius III reigned for less than a month in the year 1503.

It was the grateful nephew who, in 1495—while he was still a Cardinal—had caused a splendid library to be built against a side wall of the Cathedral in Siena in order to house his uncle’s collection of manuscripts.

And it was the nephew who commissioned a series of frescos to decorate the walls of the library with ten scenes from his uncle’s life.

It is these that form the main subject of the present lecture.

Please take a quick look at the scene of St Catherine of Alexandria among those frescos, where she stands before an enthroned Emperor, in front of a triumphal arch, ticking off the points in her discourse on her fingers.

(It is revealing, incidentally, to learn that contemporaries could accept that her conventional features were those of Lucrezia Borgia, Pope Alexander’s illegitimate daughter.)

The crowded composition of the standing figures spread across the foreground and the very bright colours of their exotic contemporary costumes are characteristic of the Early Renaissance style that had pleased Pope Sixtus IV in the papal chapel and continued to please Pope Alexander VI in the papal apartments.

This is the style which Pius III wanted.

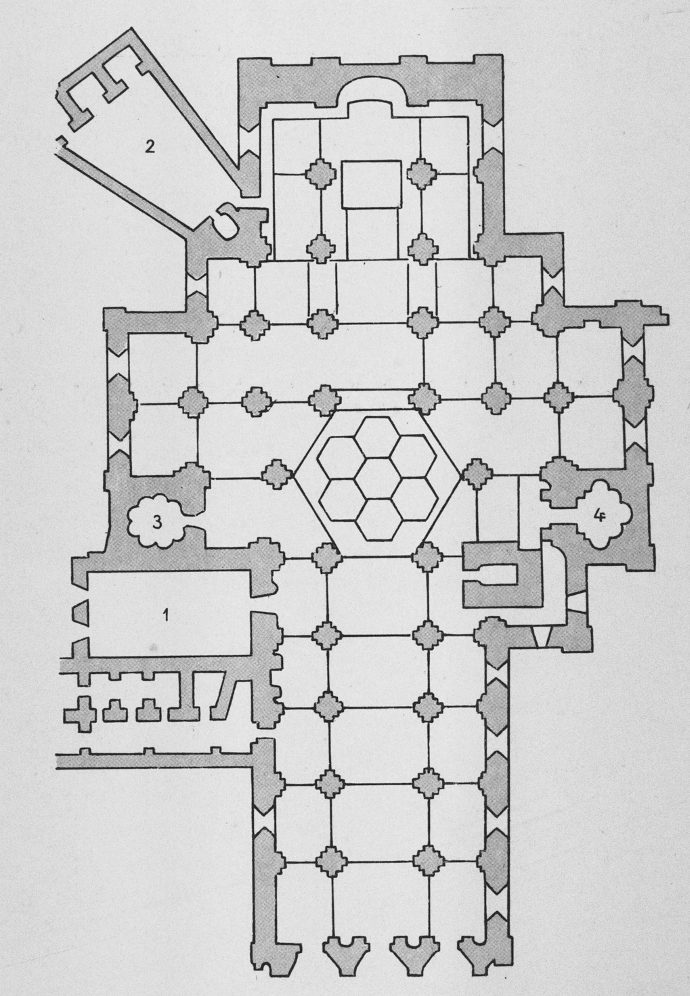

It is known as the ‘Libreria Piccolomini’—the name being that of the noble family to which the two popes belonged, which might be Anglicised as ‘little men’, ‘piccoli uomini ’.

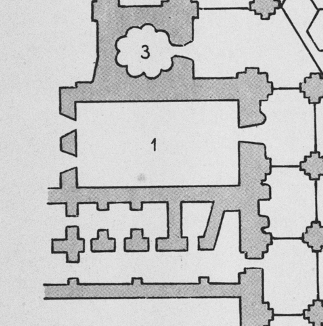

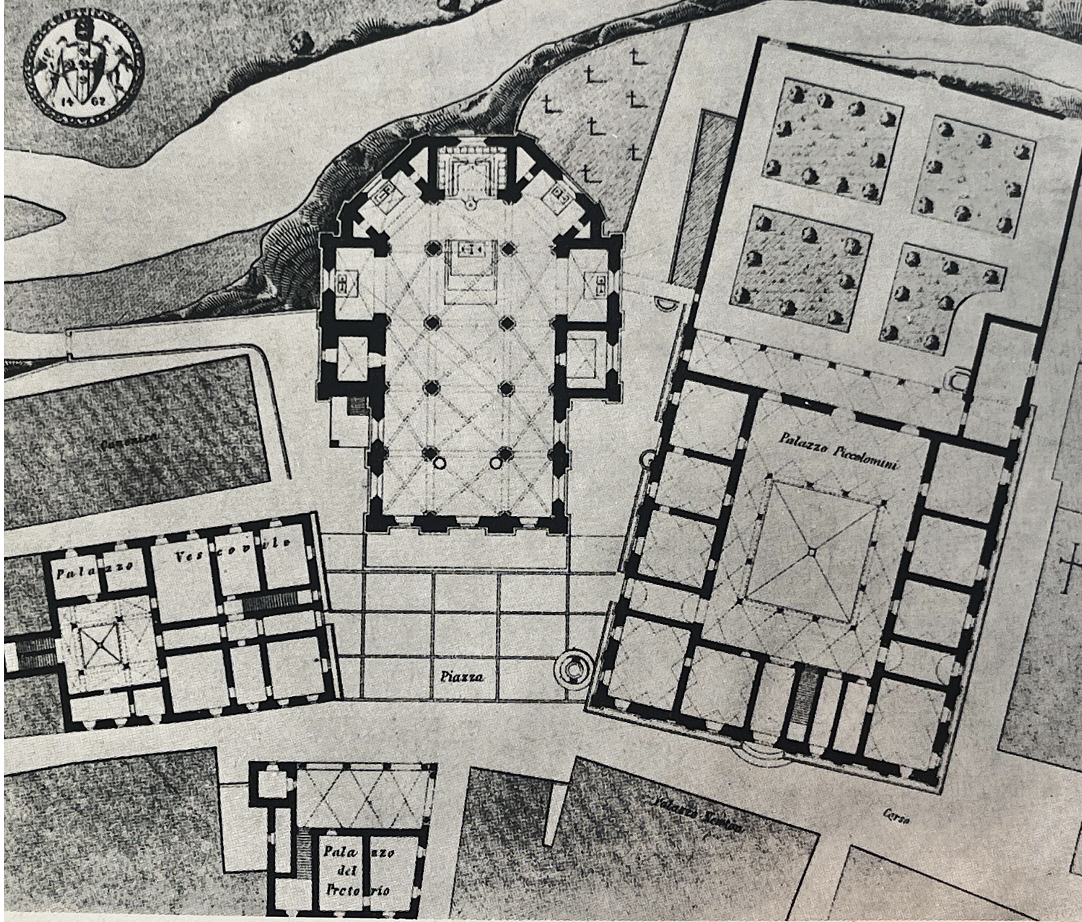

The enlarged detail of the ground plan enables you appreciate the shape of the room, which is of small-to-medium size and relatively narrow, measuring only about 60 feet by 30.

The plan also allows you to see that the natural light comes from two narrow windows in the short, exterior wall (the north wall; here on the left), while the photograph (in which the two windows are curtained) gives a good impression of the generous height of the room.

The general effect is very welcoming, as you see, with a feast of bright colour in the frescos (the contract actually specifies ‘colori buoni e fini ’).

There are illuminated manuscripts supported on lecterns which run right round the walls; and, in the centre of the floor, there is a delightful classical statue group showing the three Graces.

The ceiling is painted to simulate coffering, with mythological scenes set in the simulated stucco frames; and in the very centre you can see the heraldic half-moons of the Piccolomini family, arranged as a cross in the Cardinal’s coat-of-arms.

The inscription tells us that the library was built “to the second Pope, ex pietate, by the third Pope”.

These inscriptions—and indeed the whole story—are derived from the Pope’s autobiography, which is written in the third person, and called, simply, Commentaries (the title that had been used by Julius Caesar!).

This work give a remarkably full and frank account of his life, so that we know him better than almost any other Pope before or since. (If you wish to find out more about him, there is an excellent abridgement of the complete life, in an English translation.)

The hero of our tale was one of eighteen children, born to an impoverished member of the Piccolimini clan—a mercenary soldier, who settled in a little township called Corsignano, about 30 miles to the south of Siena, not far from Monte Oliveto.

Our hero was born in 1405, and he was christened with the Virgilian names Aeneas Sylvius.

After a rural boyhood, he studied the liberal arts and civil law at the University of Siena from the ages of 18 to 25.

This brings us to the 1430s, and to the first event depicted in the Libreria.

To understand the first four scenes in the story, it is necessary to know a little about the history of the Church and the Papacy.

For 40 years, from 1378 to 1417, two rival popes had claimed to be the ‘successors of Peter’, each with his own college of cardinals, and each with European support.

One was based in Rome, the other in Avignon, which had become the seat of the papal administration in the year 1309.

The protracted scandal of this ‘Great Schism’ led the rulers of Europe to bring pressure for there to be a General Council of the Church to bring it to an end; and after one false start in the year 1409 (which led to the emergence of a third claimant), this Council was eventually held at Constance, just over the German border from Switzerland, in the years from 1414 to 1418.

Among many other items of business and of reform, the Council deposed the existing claimants (all three of them) and elected a Roman aristocrat as Martin V—imposing on him the obligation to call frequent and regular General Councils in the future. Martin returned to Rome in 1420, and he was successful in reasserting Papal authority, both in the Church as a whole, and as temporal overlord in the Papal States. However, just before he died, he honoured his promise (or bowed to pressure), and summoned another Council of the Church.

This time the Council met in Switzerland, in Basel; and its deliberations dragged on and on, even beyond the lifetime of the next Pope, who took the name of Eugenius IV, and was at loggerheads with the Council and with the whole Conciliar Movement throughout his long and turbulent reign.

I tell you all this because the future Pope Pius II identified himself with supporters of the Council of Basel, and did not make his peace with Pope Eugenius until he was fully 40 years old, in 1445.

But let us go back to 1432, and close in on young Enea Silvio, who is 27 years old and holds the equivalent of a degree in lettere and a degree in law. He is in no way associated with the church; and in this fresco he is dressed fashionably, as befitted his youth and rank, and is riding a very spirited horse.

The man in ecclesiastical dress in front of him is Domenico Capranica, who had been nominated as a cardinal by Martin V, but denied consecration by Eugenius.

Capranica decided to plead his case for consecration at the newly convened Council of Basel; and as he passed through Siena on his way to Switzerland, he hired the newly graduated Enea as his private secretary.

What the foreground of the fresco shows is the resumption of the party’s journey to the Council of Basel; and I stress ‘resumption’, because the journey had begun disastrously.

Owing to a war between Siena and Florence, they could not use the ‘Frankish Way’, and they decided to go by sea from Piombino to Genova.

However, a great storm arose with winds from the north, which drove the vessels due south for about 200 miles, to within sight of the coast of Africa!

From this remote latitude they crept back to the Italian coast near Genoa and resumed their journey to Switzerland.

(The detail combines the storm and the disembarkation. The little port on the hill is obviously the work of Pintoricchio’s least gifted assistant, but the driving rain of the squall out at sea is nicely observed, and the rainbow promises that all will be well.)

It was clearly an unforgettable beginning to Enea’s career in the ‘diplomatic service’; but if you have a suspicious cast of mind, you may wonder whether the telling of the tale was not somewhat influenced by the storm described in the first book of Virgil’s Aeneid, a storm that drove the first Aeneas to the African coast, near to where Queen Dido was constructing the city of Carthage, which would become the arch-rival of Rome.

In short, it is not difficult to see a symbolic value in this storm, which drove our Aeneas ‘off-course’ when he was about to support the Council against Pope Eugenius.

In the foreground scene, there is not only a good deal of autograph work by Pintoricchio, but clear evidence that he made use of this glorious sketch, which is attributed to none other than Raphael (who was another, much younger pupil of Perugino).

It is probably to Raphael that we owe the imminent change of direction in the cavalcade, which we see advancing in the plane of the picture, but about to swing to the left, with the change being strongly emphasised by the horse of young Enea, by the twist of his body in the saddle, and by the thrust of his legs against the stirrups—the new direction being ‘confirmed’ by the braced legs of the halberdier.

We could learn a lot more by looking at the differences between the fresco and the drawing (such things as the addition of Enea’s hat and of the pattern-book greyhound, or the drooping of the horse’s tail, or the transformation of Raphael’s vigorous young page into his rather languid counterpart). But I must begin to prepare you for the second scene.

If you piece together your vague memories of Shakespeare’s history plays and of Bernard Shaw’s Saint Joan, you will recall that England (under Henry VI) and France (under Charles VII) were still engaged in their ‘Hundred Years War’, and that Joan of Arc was burnt at Rouen in 1431, the year before young Enea finally reached Basel.

This war is the background to the first really important mission undertaken by Enea, after he had been in attendance at the Council for three years.

A senior cardinal was sent to make peace between the combatants—between England and France—and having detached the Burgundians from the English, he wanted to bring in the Scots on the side of the French. Specifically, he wanted the Scots to make some raids on England, so that Henry would be deterred from sending more troops to France.

To this end, Enea was sent on behalf of the Council (after another stormy journey, lasting eleven days), to the court of King James I in his ancient capital of Perth (easily recognisable in the second fresco!)

The setting is not ‘Scottish baronial’, but ‘Italian classical’, with a coffered ceiling, a tiled floor, and a classical arcade behind, with medallions of emperors in the spandrels.

The venerable king (James was actually only forty at the time) is shown seated on a very high throne, surrounded by his courtiers, old and young, lay and ecclesiastical.

There is a nod in the direction of Christian iconography, with the king hinting at God the Father and Aeneas standing like the Angel Gabriel—except that he is ticking off the points of his mission on his fingers (like St Catherine in Alexandria). Or perhaps you could visualise Aeneas as the youngest of the three Wise Men, placed between the middle-aged and oldest kings on either side in the foreground. From yet another point of view, the most important ‘emblem’ in the fresco is probably the half-moon of the Piccolomini coat-of-arms at the foot of the polychrome marble column.

It will be obvious from these comments that we must not look for historical realism in the costumes and settings—any more than we do in the landscape, where the hills and water might just pass muster as a loch in the highlands but where the ‘kirk’ is not quite so idiomatic, and the local boats would probably be more at home in the Mediterranean—or even in the Red Sea.

Enea returned safely to the continent (having travelled through England, disguised as a merchant) and continued to work in Basel. There, the Council was beginning to lose the battle with the Pope, because in 1438 Eugenius summoned another, successful, Council of the Church, which convened first in Ferrara, and then in Florence.

In a last desperate throw of the dice at the end of 1439, the Council of Basel declared that Eugenius was deposed, and elected as its Pope an extraordinary character, a prince of Savoy called Amedeo, who had retired from the world in order to found an Order of ‘Knights-Hermit’ with headquarters on the shores of Lake Geneva.

The election of Amedeo was masterminded by Enea; and this drawing (possibly by Raphael) shows Enea at the ceremony in January 1440, when the new Pope (who took the name of Felix V) finally renounced his earthly kingdom (the Kingdom of Savoy) in favour of his two sons.

Aeneas became Felix’s secretary for three years, and the drawing seems to be the modello for a fresco in the Libreria which would have commemorated this phase. At some point in the preparations, however, someone must have realised that it would be rather too provocative to show the future Pope in the service of an ‘anti-pope’, and the scene was abandoned.

It was one of his early missions on behalf of Felix that led to Enea’s first meeting with the recently elected Holy Roman Emperor, Frederick, a Hapsburg from Austria.

(He was a young man who was to reign for fully 53 years, from 1440 down to 1493.)

The two men hit it off immediately; and in 1442, Frederick crowned his new ‘friend’ (amicus is used in the inscription) as a poet. He did so with a laurel crown, in the same way that King Robert of Naples was said to have crowned Petrarch a hundred years earlier.

This is the subject of the third fresco.

Behind the customary arch, we are to imagine a vast square in the ancient capital of Charlemagne (at Aix-la-Chapelle), where there is a very modest crowd of what, in the theatre or cinema, would be called ‘extras’.

Behind them is a huge classicising loggia, with no fewer than five colonnades—as charming and as unconvincing as the positively ‘pterodactylic’ hawk and duck in the sky above.

Time has not passed for Enea, it would seem, in the seven years since he appeared before King James of Scotland. This time, however, although he is kneeling, he is the person who is being honoured for ‘his services to Latin literature’ by the Emperor Frederick.

Enea was finally released by Felix, and he became protonotary and secretary to the Emperor himself, who, for his own political reasons, was to continue as ‘neutral’ between the conflicting claims of Eugenius, on the one hand, and of Felix and the Council of Basel, on the other.

However, the time came when the Emperor (and his secretary) decided that they must throw in their lot with Eugenius.

This is the subject of the fourth fresco.

Poor old Pintoricchio—who was asked to represent, for the third time running, a scenario that puts a still secular Enea in front of a ruler, on a throne, in public audience.

He does his best, though.

He changes the tonality, introducing some dark pinks, strong reds, and greens.

As in Scotland, he places the papal throne very high in the centre, but now he uses two roughly symmetrical cardinals as repoussoir figures in the foreground, placing them very close to the frame.

The other cardinals do not form a frieze because they are seated, five to a side, in a convincingly deep interior. The open-air scene is placed much further back than in Scotland. Finally, he places our hero—the Emperor’s penitent envoy—to the right of the papal throne, as he kneels, not to receive a laurel crown, but to kiss the Pope’s foot, seeking forgiveness and absolution for his master.

This proved to be a decisive moment.

A year later, the 41 year old Enea took Holy Orders for the first time, and soon after that, in 1447, he was made Bishop of Trieste, still close to his imperial master’s centre of power in Austria.

(This is what we are shown in the diminutive scene in the background.)

Three years later, in 1450, the new Pope, a fellow humanist, Nicholas V, appointed him bishop of his native Siena; and it is as Bishop of Siena that he will appear in the next fresco, which lies on the left of the entry wall.

Since the setting is important, let us take a look at the buildings in the background before we look at the whole.

You will recognise immediately the Cathedral, with its cupola and bell-tower, on the right.

You will therefore deduce that you are standing outside the city, to the north, looking south, with the tower of the Palazzo Pubblico and the other noble towers and bell-towers in the centre, and the gate called Camollia on the left. (The marble column, of which you can see the upper portion in the detail, is still in the same place to this day.)

The coats-of-arms at the top of the column are the clue to the event commemorated by both the column and the fresco. They are the imperial eagle of the Emperor, Frederick, and the arms of the royal house of Aragon in Spain, whose king, Alfonso, was also King of Sicily (since 1416), and had recently (1442) made himself King of Southern Italy as well.

Enea was continuing to work for Frederick, and in 1451 he pulled off two very delicate negotiations.

First, he went to Naples, in order to arrange the terms of a marriage between the Emperor and Eleanora of Aragon, a niece of King Alfonso, and sister of the King of Portugal.

Second, he negotiated with the rulers of Northern Italy for the Emperor to be allowed a safe conduct to Rome so that he could marry his bride there, and so that he could be formally crowned and consecrated by the Pope.

There were agonising delays on both fronts: the winds were unfavourable, the rulers jittery, but finally Enea had the satisfaction of receiving Eleanora in Siena; and then, on 24 February 1452, of conducting her outside the northern gate of the city, to meet her royal fiancé at the head of his retinue.

I will not labour the debt to Pintoricchio’s fellow pupil but concentrate your attention on the centre.

Enea, in his bishop’s mitre, slightly older now, places his hands on the shoulders of the queen as though he were ‘giving her away’, blessing the union of the royal couple.

Frederick, with his long hair, is ardent and romantic, rejoicing in Eleanora’s evident good-looks; she stands, with eyes modestly lowered.

The emperor is flanked by the bearded duke Albert of Austria, and by young Ladislaus, King of Hungary and Bohemia.

I show you two enlargements from this scene, to make the point that much of the pleasure in Pintoricchio’s frescos comes not from his sense of drama or his psychological insight, but from his close observation of expensive, brightly coloured, contemporary costumes.

Look, for example, at the highly complex ‘slashes’ in Eleanora’s sleeve, through which the loose chemise is gently and fashionably tugged, or at the pleasing incongruity between the Emperor’s golden slipper, and his red and white ‘flip-flop’.

Aeneas’s skill as a diplomat and troubleshooter was not limited to matchmaking. His reputation grew steadily in the early 1450s, both in Italy and in Europe.

His eloquence helped to prevent a major revolt by the electors and bishops of Germany. (Incidentally, his account of their grievances is wonderfully prophetic of the Reformation).

A second, personal mission to King Alfonso at Naples thwarted the attempt of a mercenary general called Piccinino to conquer the Sienese state for himself (he had been trying to emulate his counterpart, Francesco Sforza, who had just seized power in Milan).

After the Fall of Constantinople to the Ottoman Turks in 1453, Enea played his part in the efforts that led to the Peace of Lodi in 1454, which ended a war between Milan and Venice that had lasted for thirty years, and which gave the Italian peninsula relative stability for the next 40 years.

He also devoted a great deal of effort to persuading the European powers to agree on joint military action against the Turks, who were now threatening Hungary and Austria; and we shall see that his commitment to the cause of a new ‘Crusade against the Infidel’ was to be the leitmotif of the last years of his life.

March 1455 saw the election of a new Pope, a surprise candidate—the 70 year old Catalan, Alfonso Borgia, who took the name of Calixtus III.

(Notice the pack-mules with bales of wool entering the gate of Siena, a city still under the protection of the Virgin, and still dominated visually by the Torre del Mangia and the black and white bands of the Cathedral.)

Pope Calixtus ignored Enea’s claims for a Cardinalate the first time round, appointing instead three members of his own family, including his 24 year-old nephew, Rodrigo Borgia (who was to become Pope as Alexander VI in the 1490s, and for whom the artist Pintoricchio had already worked).

In the autumn of 1456, however, Calixtus listened to the representations made by the European powers, and nominated a further six cardinals, among them our hero, as we see in the sixth scene, where he kneels to receive his cardinal’s hat from the pope.

‘Poor old Pintoricchio’, I say again, faced with yet another throne, and yet another genuflection from Enea.

He adopts the same solution as he did in the parallel scene in the fourth fresco, putting the main actors on the left; but you can also see that he has done his best to differentiate the two scenes.

Here we are genuinely indoors, and there is no distant prospect. We are in a narrow chapel, with a splendidly coffered ceiling; and the small space to the rear of the scene is full to bursting with the lay spectators (the ‘extras’, as I called them), who are all confined behind the altar.

(The important witnesses in the foreground include the famous humanist Cardinal Bessarione, in green; while the cardinal in pink on the pope’s right hand is his right-hand man—Rodrigo Borgia.)

Pintoricchio does what he can to make the real protagonists interesting, but once again there is more to be enjoyed in the inanimate things he has placed in the centre of the composition—the mullioned windows in the plain wall, the foreshortened canopy high over the altar, and above all, the altarpiece itself (with St John the Baptist and Saint Andrew), convincingly mid-fifteenth-century in style, in an elaborate gold frame.

In the summer of 1458, when Enea was 53 years old, he had gone to Viterbo to take the waters to treat his ever more painful gout; and he was just starting work on his History of Bohemia, when he learnt of the death of Pope Calixtus. He hurried to Rome to attend the very elaborate funeral.

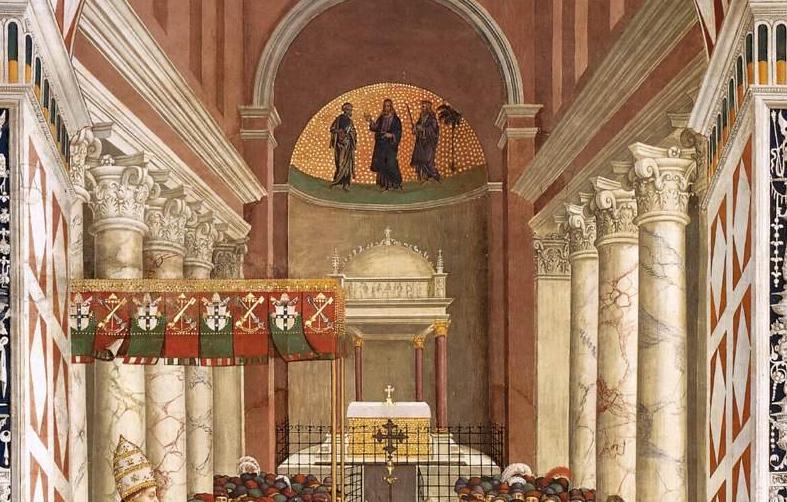

Then, on the 16th of August, he and the seventeen other cardinals who were able to attend—there were 24 of them in the College in all—went into conclave in the papal chapel in the medieval wing of the Apostolic Palace. (You can see the site of the chapel in the foreground of the photograph.)

Enea himself told the story of what happened in the chapel; and it is so interesting that I will abandon Pintoricchio for a little while in order to take you through his narrative and let you read some excerpts from Enea’s own Commentaries.

All you have to remember by way of introduction is that the whole point of a ‘conclave’ is that the electors are locked in ‘with a key’, cum clave, until they have reached a decision, and that this procedure was normally expected to last for several days.

The cardinals and their personal servants set up temporary living quarters in the ‘Great Chapel’, soon to be rebuilt and named the ‘Sistine Chapel’; and they held the formal part of their meetings in a small private chapel nearby—as far as I can tell, it was the one that had been frescoed eight years earlier by Fra Angelico.

The majority required for an election was two-thirds: hence, in this case, the target was 12 votes out of 18. On the first day they did nothing. On the second day, they all agreed on certain conditions that would be binding on whoever was to be elected. And on day three, they proceeded to the first vote—or, as they said, the first ‘scrutiny’.

The result was five votes for Philip, Bishop of Bologna; five for our hero; no more than three votes for anyone else; and most surprisingly, no votes at all for one of the most powerful of the cardinals, William, or rather Guillaume, the Archbishop Cardinal of Rouen.

No attempt was made to transfer votes at this stage, and this ‘chapter’ in the narrative ends with the cardinals breaking off for dinner: itum est ad prandium.

The next chapter begins with private conferences, or ‘conventicles’ (conventiculae), in which the ‘more powerful’ (potentiores) in the college tried to win support for themselves and for their friends.

The most powerful of them all, as you will guess, was none other than the Cardinal of Rouen. He saw that his main rival was going to be Enea, and he attacked him in the ‘conventicles’ as being someone who was still unknown, suffering from gout, without any personal fortune, far too involved with Germany, and suspect because of his reputation as a poet and a classicist.

Pedibus laborantem et pauperem nobis pontificem dabis? Quomodo relevabit inopem ecclesiam inops? Aegrotantem aegrotus? Ex Germania recens venit: nescimus eum; forsitan et curiam eo traducet. Quae sunt in eo litterae? Poetamne loco Petri ponemus? Et gentilibus institutis regemus ecclesiam?

Will you give us a lame, poverty-stricken Pope? How shall a destitute Pope restore a destitute Church, or an ailing Pope, an ailing Church? He has only recently come from Germany. We do not know him. Perhaps he will even transfer the curia there. And look at his writings! Are we going to set a poet in Peter’s place? Shall we govern the Church by the laws of the heathen?

And as for Guillaume’s own merits:

Ego in cardinalatu senior sum, nec me imprudentem nosti; et doctrina pontificali sum praeditus, et regium sanguinem prae me fero et amicis abundo et opibus, quibus subvenire ecclesiae pauperi possum. Sunt et mihi beneficia ecclesiastica non pauca, quae dimissurus inter te et alios dispertiar.

I am the senior cardinal. You know I am not without practical wisdom. I am learned in pontifical law. I can boast of royal blood. I am rich in friends and resources, with which I can succour the impoverished church. I also hold not a few ecclesiastical benefices, which I shall distribute among you and the others, when I resign them.

According to Enea, Guillaume held meetings in the washrooms (in latrinis); and he was sufficiently persuasive to get eleven cardinals to pledge their support to him ‘in writing and with oaths’. At this point, the group became very confident, because, as Enea says:

Et, cum undecim concurrere viderentur, non dubitabant quin duodecim statim haberent. Nam, cum eo ventum est, praesto adest qui ait “Et ego te papam facio” ut eam ineat gratiam. Confectam igitur iam rem existimabant nec aliud expectabant quam lucis adventum, ut ad scrutinium veniretur.

Since it now appeared that eleven were agreed, they did not doubt that they would at once get the twelfth. For when it has come to this point, someone is always at hand to say “I too make you Pope”, in order to win the favour that this utterance always brings. They therefore thought that the thing was as good as done, and they were only waiting for daylight to go to the scrutiny.

Chapter V begins dramatically, with a reminiscence of Book II of the Aeneid, where the original Aeneas was roused from his sleep by the ghost of Hector, telling him that the Greeks were within the gates. Our Aeneas is awakened by Philip of Bologna, some time after midnight:

Iam noctis medium effluxerat, cum ecce Bononiensis Aeneam adit, et dormientem excitans: “Quid ais”, inquit, “Aenea? Nescis quia iam papam habemus? In latrinis convenere aliquot cardinales, statueruntque Vilhelmum eligere, nec aliud expectatur quam dies. Consilium meum est ut surgens e lectulo, illum adeas vocemque tuam illi offeras priusquam eligatur, ne sit te adversante pontificatum obtineat, odiosus fiat tibi.”

Midnight was already past when the Bolognese came to Aeneas and, rousing the sleeper, said: “Don’t you know we’ve already got a Pope? Some of the cardinals have met in the lavatories and decided to elect Guillaume. They’re only waiting for daylight. I advise you to get up and go and offer him your vote before he’s elected, for fear that if he’s elected with you against him, he’ll make trouble for you.”

Philip proposes to follow his own advice; but Aeneas makes a high-minded reply, refusing to betray his own principles, whatever the risks. This impresses Philip sufficiently for Philip not to become that twelfth man.

Chapter VI shows Enea seizing the initiative. At daybreak, he calls on Rodrigo Borgia, who admits that he is only supporting Rouen because he thinks it is the best way to keep his post as Chancellor. Enea wins him over with some straightforward nationalistic arguments, to the effect that: ‘once a Frenchman has power, he will nothing do for a Catalan’.

In Chapter VII, he sees Giovanni, the Cardinal of Pavia, who is supporting Rouen only because he wants to be on the winning side; and he develops the same sort of purely nationalistic or ‘chauvinist’ arguments with some rather heady rhetoric.

Aut ibit in Galliam pontifex gallus, et orbata est dulcis patria nostra splendore suo, aut manebit inter nos, et serviet regina gentium Italia extero domino erimusque mancipia gallicae gentis. Regnum Siciliae ad Gallos perveniet; omnes urbes, omnes arces ecclesiae possidebunt galli.

A French pope will either go to France, and then our dear country is bereft of its splendour. Or he will stay among us, and Italy, the Queen of Nations, will serve a foreign master, while we’ll be the slaves of the French. The Kingdom of Sicily will fall into the hands of the French. The French will possess all the cities and strongholds of the Church.

The Cardinal of Pavia was so overcome by this that he burst into tears and agreed to break his promise to the Cardinal of Rouen. So our hero’s eloquence had reduced the opposition from a dangerous eleven to a still formidable nine.

The next chapter tells how the Cardinal of Venice (having abandoned all hope of being elected himself—his turn would come six years later) called together the native Italians, implored them not to let a foreigner become Pope, and urged them to vote for Enea. They agreed to do this, thus assuring him of seven votes.

This brings us to the dramatic final chapter, whose action takes place in the little chapel where the cardinals assemble for their second ballot.

A golden chalice was set upon the altar.

Three cardinals stood by to observe and to prevent foul play (ne fraus intercederet); and each cardinal went up, in order of seniority, to place his written vote in the chalice. One of the three scrutineers was Guillaume of Rouen.

Cumque iret Aeneas velletque suam papyrum in calicem mittere, expallens tremensque Rhotomagensis: “En”, inquit, “Aenea habeto me commendatum”, temeraria prorsus vox eo in loco in quo non licebat mutare scripturam. Sed vicit prudentiam ambitio. Aeneas vero: “Mihi te”, inquit, “vermiculo commendas?” Nec plura locutus, in suum locum abiit, scedula in calicem proiecta.

When Aeneas came up to put in his ballot, Rouen, pale and trembling, said “Look Aeneas, I commend myself to you”. Certainly a rash thing to say when it was not allowable to change what he had already written. But ambition overcame prudence. Aeneas said: “Do you commend yourself to a worm like me?” And without another word he dropped his ballot paper in the cup and went back to his place.

The scrutineers up-ended the chalice on the table, and read out the individual votes one by one. The result was six for Rouen, and nine for Enea.

They all agreed that they ought to see if they could reach a decision there and then, by what was called an ‘accession’, that is, by a public transfer of votes. They sat there ‘like statues’ for a long time. The first man to break the silence was Rodrigo Borgia, who rose to say: ‘I accede to the Cardinal of Siena’.

At this point, two elderly cardinals tried to create a diversion by ‘pretending physical needs’. But they returned, and at this point one of the two Greek cardinals gave his vote for Enea. Now only one more vote was necessary. Realising this, the Roman cardinal Prospero Colonna thought he would ‘get for himself the glory of announcing the Pope’. But, as he got to his feet, he was threatened and then seized by Rouen and the remaining Greek cardinal, who tried to bundle him out of the chapel before he could speak:

Verum Prosper calumnias et inania verba flocci faciens, quamvis in voto suo Rhotomagensem elegisset, Aeneae tamen veteri benivolentia coniunctus, versus ad reliquos cardinales: “Et ego”, inquit, “Senensi cardinali accedo eumque papam facio”. Quo audito, ceciderunt adversariorum spiritus et omnis fracta est machinatio.

But Prospero paid no attention to their abuse and their empty threats. Although he had voted for the Cardinal of Rouen on his ballot paper, he was nevertheless bound to Aeneas by ties of old friendship. Turning to the other cardinals, he said: “I too accede to the Cardinal of Siena, and I make him Pope”. When they heard this, the courage of the opposition failed, and all their machinations were shattered.

The new Pope had to choose a name.

Not for him the popular John, Innocent, or Leo. He went right back to the second century, for a name that had only been used once before—Pius.

Pius is the recurrent epithet for Virgil’s hero, Aeneas. So the new pope’s name—Pius (Aeneas), ‘Pious Aeneas’—is a delightful homage to the language and literature to which he owed his successful career.

Enea was to be Pope for six years, years that were full of activity.

As far as he was concerned, indeed, the story had barely begun. All the events we have been looking at are narrated in the first book of his Commentaries, and there are twelve more books to come!

However, as far as his nephew and Pintoricchio were concerned, the achievements of his Papacy could be reduced to three—two on the international scene, and one relating to the Church and to Siena.

His first major task, occupying him in 1459 and 1460, was a Congress of European powers, which he summoned at Mantua.

This is the scene in the eighth fresco.

(Mantua does indeed have a shallow lake big enough for the Marquis to organise a mock naval battle in honour of his guest).

The aim of the Congress was to persuade the rulers of Italy and Europe and the major ecclesiastics of the Eastern and Western churches to resolve their differences and make a common front against the Turk—against the infidel.

The Pope also seized the opportunity to try and settle some theological differences with the patriarch of Constantinople.

We see him on his throne, ticking off his points on his fingers (with his Cardinals in mute support), while the Patriarch argues back—ticking off his points—assisted not only by his interpreter but by a whole bevy of experts, who have brought the relevant texts and documents.

You will also notice the usual contrast between clean-shaven Catholics and bearded orthodox clergy.

Perhaps it is not surprising, then, that like so many ‘summit meetings’ since that time, the conference did not lead to any important practical results, even though it was agreed to assemble a ‘task-force’ of sorts, and to hire a Venetian fleet in order to attack the Mediterranean islands, rather than simply defending Hungary or the Italian coast.

We now leave that fleet to assemble (it took four years!), and return with Pius to Rome, where in June 1461 he officiated at the service of canonisation for St Catherine of Siena, the fourteenth-century mystic and reformer from his native city.

In a new ‘split-level’ composition we see a couple of the usual elegant ‘extras’ holding candles (the youth on the left was formerly believed to be a portrait of Raphael); while the remainder have been made to wear friars’ cowls and habits for the day.

In the scene at the top of the fresco, the Pope pronounces the formula of canonisation—which had been long desired, and was very popular in Siena—over the body of the saint. (Her heart and her head had been preserved separately, but were brought together for the occasion.)

You will see that Catherine is dressed in her habit as a Dominican tertiary, holding a lily, while the stigmata on her hands seem to eradiate light.

A Renaissance Pope usually had time to devote to building projects that would perpetuate his name after ‘the glory of the world had passed’.

Pius initiated quite a few projects in Siena, but his personal dream—which he realised in just three years—was to transform the centre of the tiny township of Corsignano, where he was born and had lived in obscurity until he was eighteen, into a perfect city ‘piazza’, with all the buildings required for it to become a summer residence for him and his cardinals.

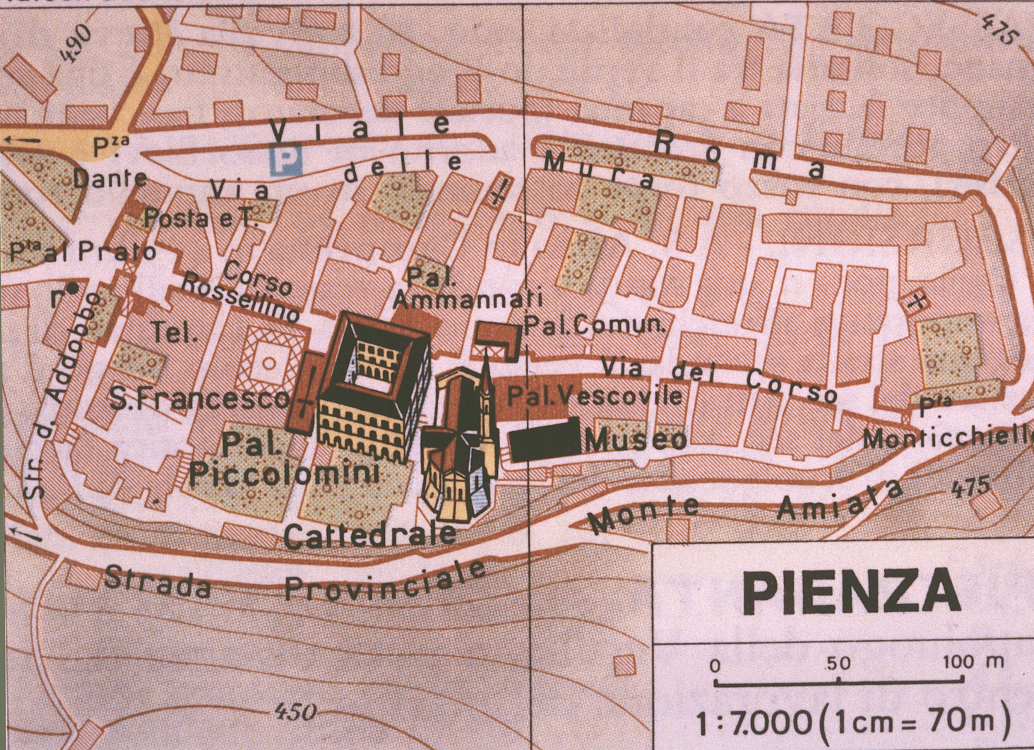

In 1462, he renamed the town ‘Pienza’.

One of the reasons why I chose not to linger on the details in the eighth and ninth scenes in Pintoricchio’s cycle was to leave space to examine the Pope’s own monument to himself, which remains more impressive in every way than that of his nephew.

Let us visit the buildings of Pienza.

A quick glance at the indication of scale on the plan reveals that the township is tiny—you can walk from one end to the other in about four minutes.

The buildings necessary to make it a papal summer residence are concentrated round the diminutive square, as shown in this old plan, which places south at the top of the map.

You can make out a small cathedral, lying north-south for reasons of space, which replaced the existing church; a palace (labelled Palazzo Piccolomini) for the pope himself, with a garden behind it, dropping down the slope of the hill; and a palace intended for the papal chancellor (labelled Palazzo vescovile), who at the time was Rodrigo Borgia. (In the photograph, this is the plain building to the left of the façade of the new cathedral).

The layout of the interior, on the other hand, was dictated by Enea himself, as we know from the documents and a number of surviving sketches in his own hand.

It was he who demanded that the apse should face South, even though it had to be shored up on the slope of a very unstable hill, down which the ‘glory of Pienza’ has nearly ‘transited’ on many occasions.

There are a number of other treasures, both in the papal palace and in the former Palazzo Borgia, which help to make the trip to Pienza even more worthwhile, should you find yourself anywhere near Siena. (Many people combine Monte Oliveto Maggiore and Pienza in the same day-excursion.)

But it is to Siena we must now return, and to the nephew’s monument to his uncle, in order to look at the last of the ten scenes in Pintoricchio’s cycle.

The year is 1464 and Pius is still trying to keep pressure on the rulers of Europe to make them honour their agreements and take action against the Turks. Hearing that the long promised Venetian fleet was ready to sail, the Pope, by now a very ill man, insisted that he should be carried in his litter to Ancona on the Adriatic coast.

After a month’s delay, on 14th August the fleet did arrive (as you can see in the detail); and a war galley brought ashore the Venetian Doge, Cristoforo Moro, who is pictured in the foreground, kneeling in a splendid robe of gold brocade.

Also receiving the papal benediction are Tommaso Paleologo, the deposed Greek despot of the Morea, dressed in blue, and, on the right, in Oriental costume, Hassan Zaccaria, the former ruler of the island of Samos, together with Calapino Bajazet, a pretender to the Sultan’s throne, who was held as a hostage in the papal court.