Introduction: Mantegna, the Triumph of Caesar

In previous cycles of lectures I have taken you to Florence and to Rome, but in this series we shall be going north-east to Venice and some of the ‘Cities of the Plain’ that lie in an arc around it (fig. 1), to show you what northern artists have to offer in the way of narrative cycles.

My interest remains the same as it has been in previous years—what Shakespeare called ‘the painted imagery of walls’: pictures intended to decorate a particular building or room, which one can go and see in their original environment rather than in museums; pictures that relate to each other, since they tell a story with a common protagonist. I am sticking to my chosen brief because I have found that narrative cycles are one of the best possible introductions to the art of the past, and to the style and pictorial conventions of artists who were painting up to five hundred years ago, because one’s innate curiosity about the story offers a ‘way in to’ the paintings, and if you stay with a single painter for a whole lecture, you have time to become familiar with his idiom, however inept the commentary might be.

In this lecture, we shall be concerned with Padua and Mantua, and I ought to say a few words about them before we begin.

As you can see from this political map (fig. 2), Mantua, the area in white, was an independent state—a marquisate, and would remain under the rule of the same family until the early seventeenth century. Padua had been an independent state in the fourteenth century, coming under the rule of the Carrara family, who were Petrarch’s last patrons; but in the early fifteenth century it had been swallowed up by the Republic of Venice, which now ruled over all the area coloured red on the map.

Padua kept its independent traditions, however, and Shakespeare would rightly say: ‘Fair Padua is the nursery of the arts’. It had its own university (which Venice did not), and it was the site of one of the first humanist schools—in fig. 3, I show you a medal-portrait of the most influential of the early fifteenth-century educators, Vittorino da Feltre, who virtually invented the ideal English Public School:

More importantly, Padua was to be very receptive to the new developments of the early fifteenth century in Florence, and particularly to the new scientific or ‘geometrical’ perspective, developed by Brunelleschi and Masaccio in the 1420s and theorised by Alberti in 1435.

I show you in fig. 5, a panel from the Fitzwilliam Museum by Domenico Veneziano, taken from an altarpiece of 1442, which is the earliest known work to follow Alberti’s theory to the letter. As you can see, the single most striking feature is the convergence of all the orthogonals—that is, all the lines parallel to the line of sight or ‘centric ray’—to a single vanishing point. Remember that the height of the vanishing point determines the horizon, which may be placed comfortably two thirds of the way up, as here, but may also be placed very high, or dramatically low, as we shall see. Similarly, the vanishing point may be placed near the centre, as it is here, or it may lie to one side, or even outside the picture itself, with dramatic results, as we shall also see.

These innovations were brought to Padua by no less a sculptor than Donatello, who in the 1440s did a superb bronze altarpiece for a huge church to the south of the city centre, the Basilica di Sant’Antonio, from which the panel in fig. 6 comes. It is a good example of what happens when you place the horizon very low, since in this case the barrel vaults are opened up to dominate the composition. Elsewhere in Padua, Donatello also did this magnificent equestrian statue (fig. 7):

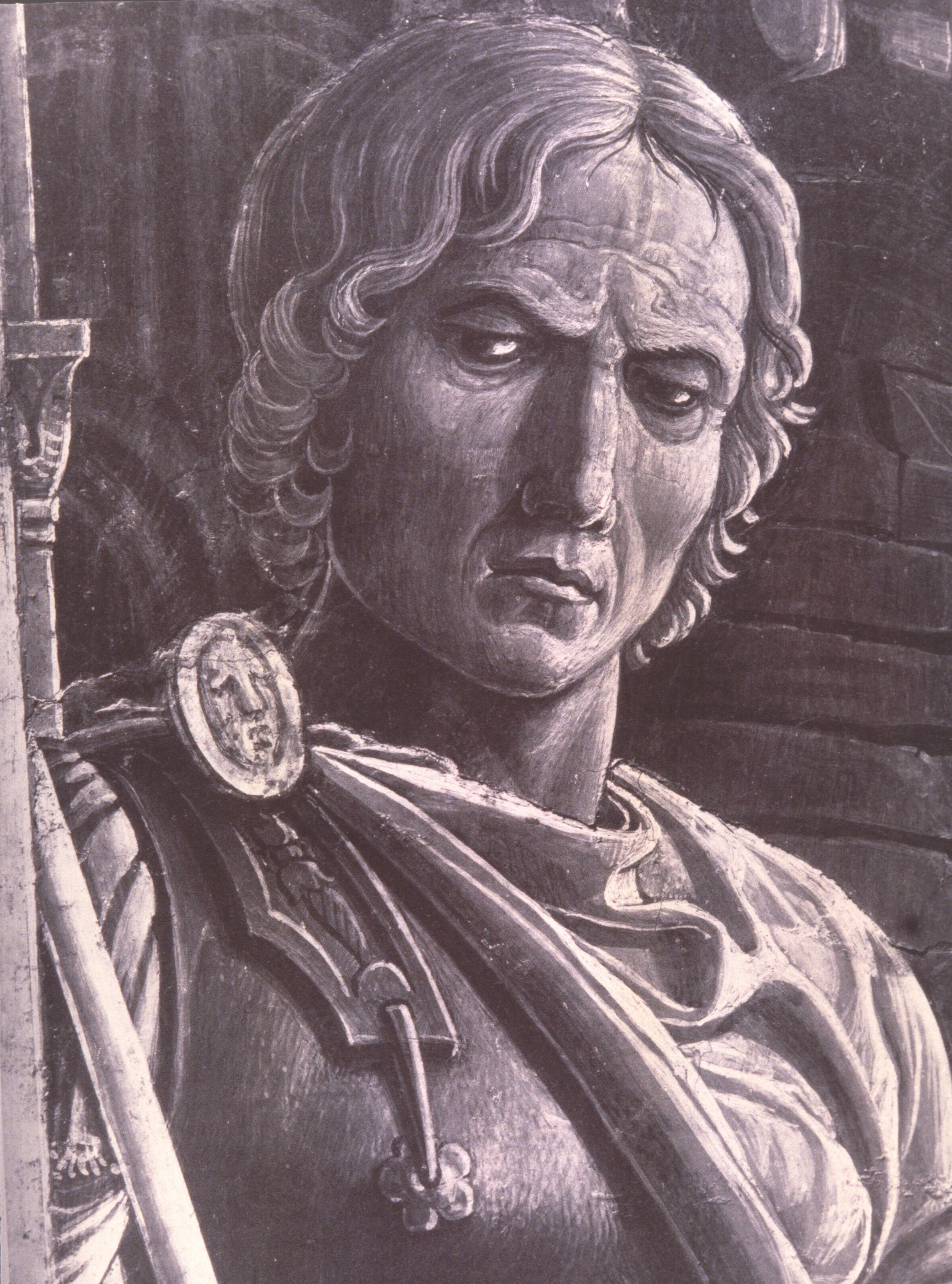

Our first northern artist is Andrea Mantegna, who was born near Vicenza in 1431, and grew up in Padua, before settling in Mantua. We shall look at no fewer than three cycles by him. The first was done in his early twenties (the image in fig. 8, left being a probable self-portrait from the cycle), the second in his early forties, and the third, as he was coming up to the age of sixty, by which time he must have looked liked the bronze bust that he himself modelled for his tomb in Mantua (fig. 9, right):

The rather ferocious expression on both likenesses is characteristic, for he was known to be extremely ‘prickly’ not to say, cantankerous, all his life. In Padua, we meet him first as the adopted son of a remarkable individual called Francesco Squarcione, a minor and backward-looking painter (as you can see in the altarpiece in fig. 10), but a great talent spotter and trainer, whose business activities (he traded in classical antiquities) were to leave a life-long mark on Mantegna, and make him well-known among the local humanists.

Mantegna was very receptive to the new trends from Florence, and to Donatello in particular. He was also very precocious. He was still only seventeen when he received a commission to decorate a chapel in another huge church in Padua, that of the Eremitani, just north of the civic centre, only a few hundred yards from the Scrovegni Chapel. This commission came as a result of provisions in the will of a local nobleman called Antonio Ovetari, who died in 1448; and the chapel is always known as the Ovetari Chapel. You can still visit the church and the chapel after you have been to see the Giottos; but, alas, they were severely damaged in a bombing raid in 1944, and the only parts of the frescos to survive did so because they were in such poor condition anyway that they had already been detached and removed.

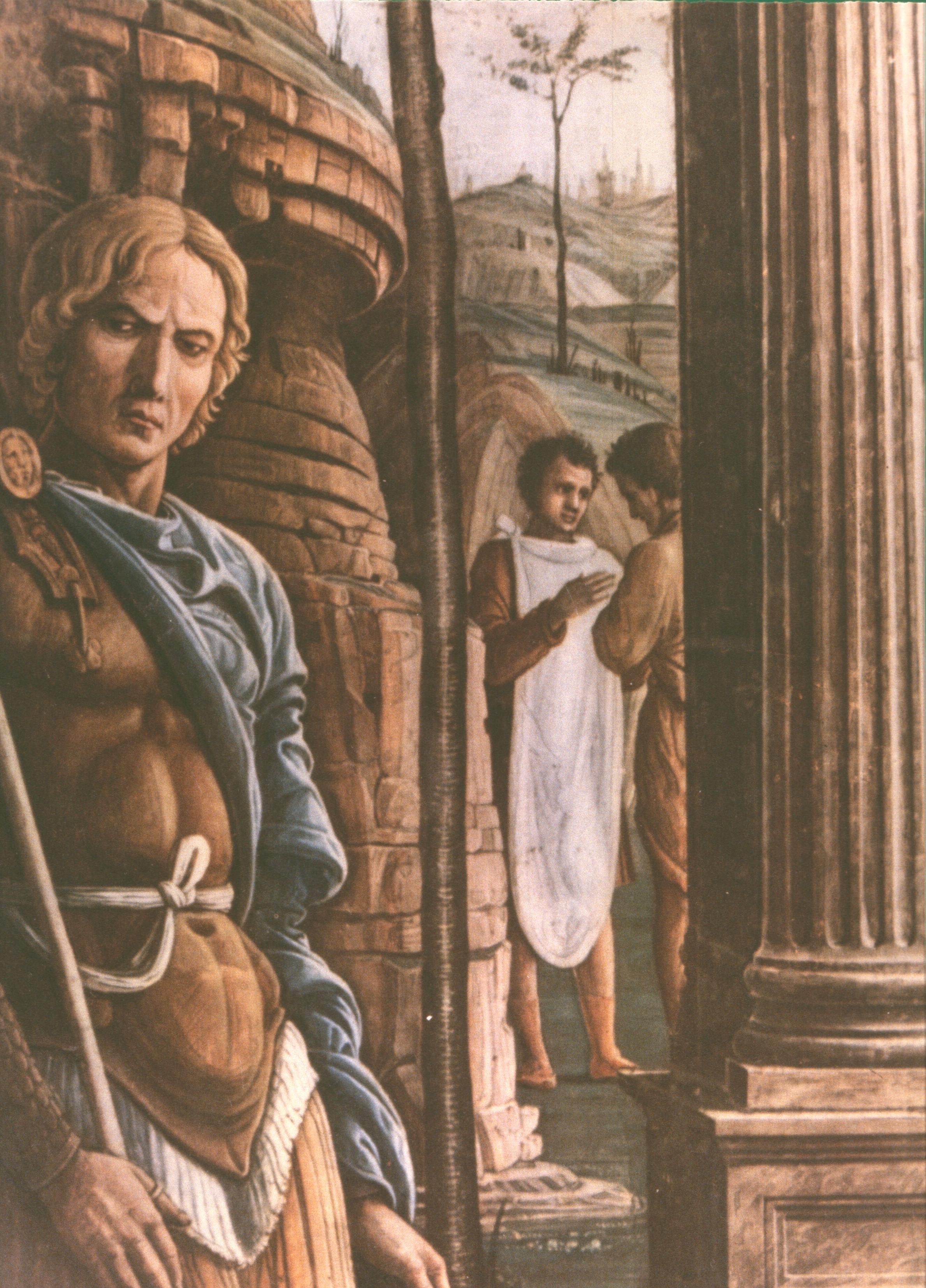

The surviving areas lay at the bottom of the right-hand wall (one detail of which is shown in fig. 11), but the frescos that I am going to show you were all on the left-hand wall, and we now know them only through photographs.

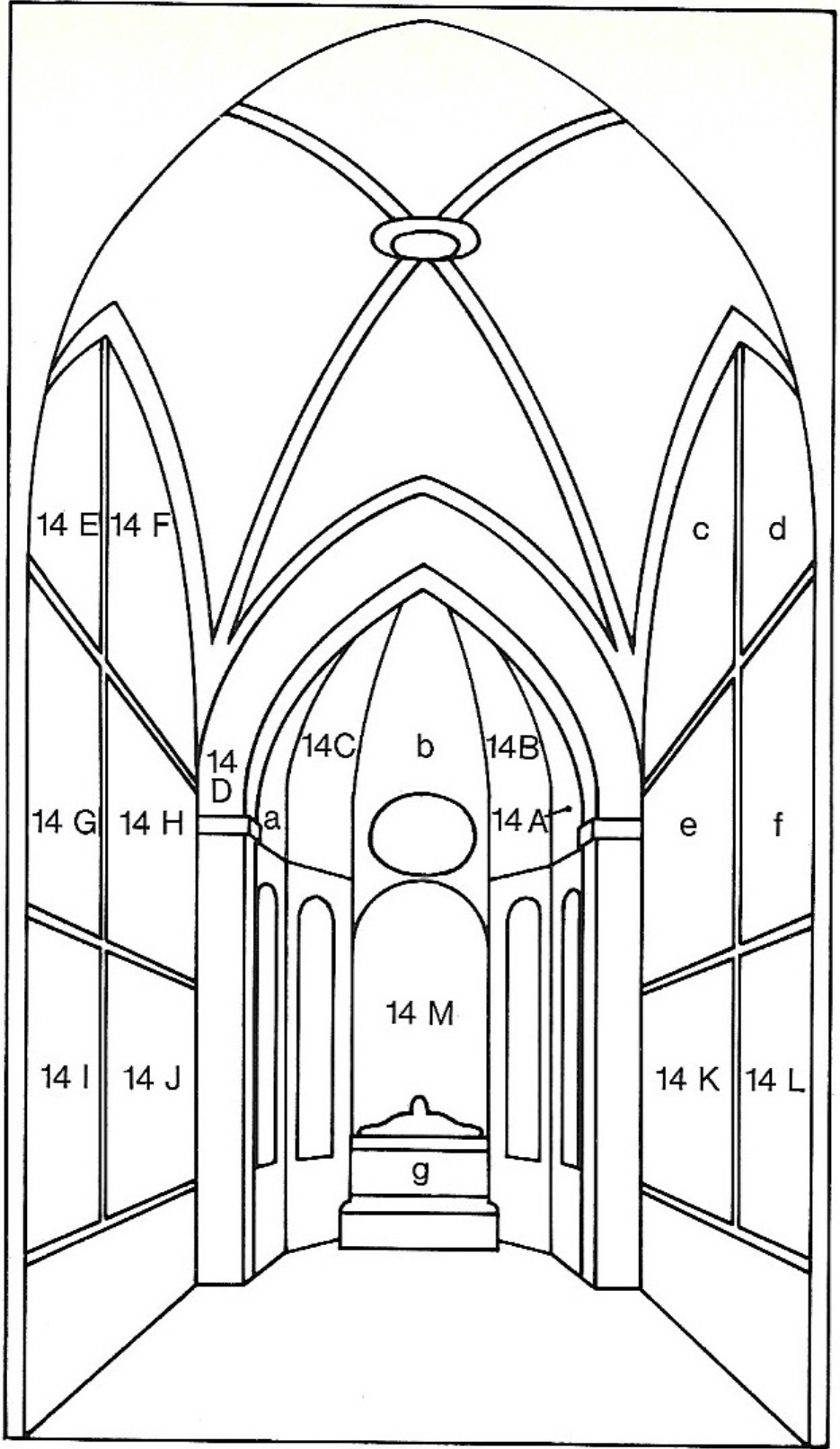

The chapel is a typical Gothic construction, as you can see in the diagram in fig. 12, measuring about 36 feet deep by 28 feet wide. The frescos were laid out in the typical fourteenth-century way, with an Assumption of the Virgin behind the altar, Apostles and Fathers in the vaults above it, and scenes from the lives of the two saints to whom the chapel was dedicated laid out on the side walls, to be read from left to right and from top to bottom.

The saints in question both have the same feast day—July 25th—and they are, on the right wall, St Christopher, and on the left wall (fig. 13), St James, James the Greater. These are the frescos we are going to look at, as best we may.

Work on the commission dragged on for six years from 1449 to 1455, with the result that there is a very marked evolution in Mantegna’s style from the upper pair, done when he was eighteen to nineteen, to the lower pair, done when he was about twenty-four. But before we trace that development, let us take in two features of the general layout that are going to be typical of Mantegna throughout his long career.

The framing and dividing strips are painted to resemble pilasters or cornices, decorated with classical motifs; and they act like the proscenium arch of a stage, apparently cutting off buildings and figures in order to suggest further, unseen spaces to the left and the right. There is also a good deal of illusionistic painting of objects or figures that seem to exist on the spectators’ side of the wall: here, as so often, we have festoons of leaves and fruit, a family coat-of-arms, and cherubs floating or fluttering—all of them out in our space.

I will not spend more than a few words on the first pair of scenes here, since they are relatively immature, and I only have black and white images. On the left, you see the only scene taken from the Bible—the ‘calling’ of the apostle, as told in the gospel of St Matthew. Jesus is flanked by Peter and Andrew (whom he has already called from their boats to make them ‘fishers of men’), while the sons of Zebedee, John, and our hero, James are kneeling before him.

On the right, meanwhile, we see an illustration of the first major episode in the version of St James’s life given in The Golden Legend for July 25th. He is preaching in Judaea, which was then a Roman province (as the architecture reminds us), when he is disturbed by demons (top left), to the evident consternation of his audience. The demons have been sent by a sorcerer called Hermogenes, whose disciple (or sorcerer’s apprentice) James has already converted to Christianity; and the demons have orders to bring back the saint and the ex-disciple bound in chains. James sends the devils packing—with orders that they should bring Hermogenes to him, bound in chains.

There is quite a lot more I would like to say about this picture, but let us press on with the story of Hermogenes, moving into the middle register, and into colour—these photographs having been taken just a few days before the chapel was bombed.

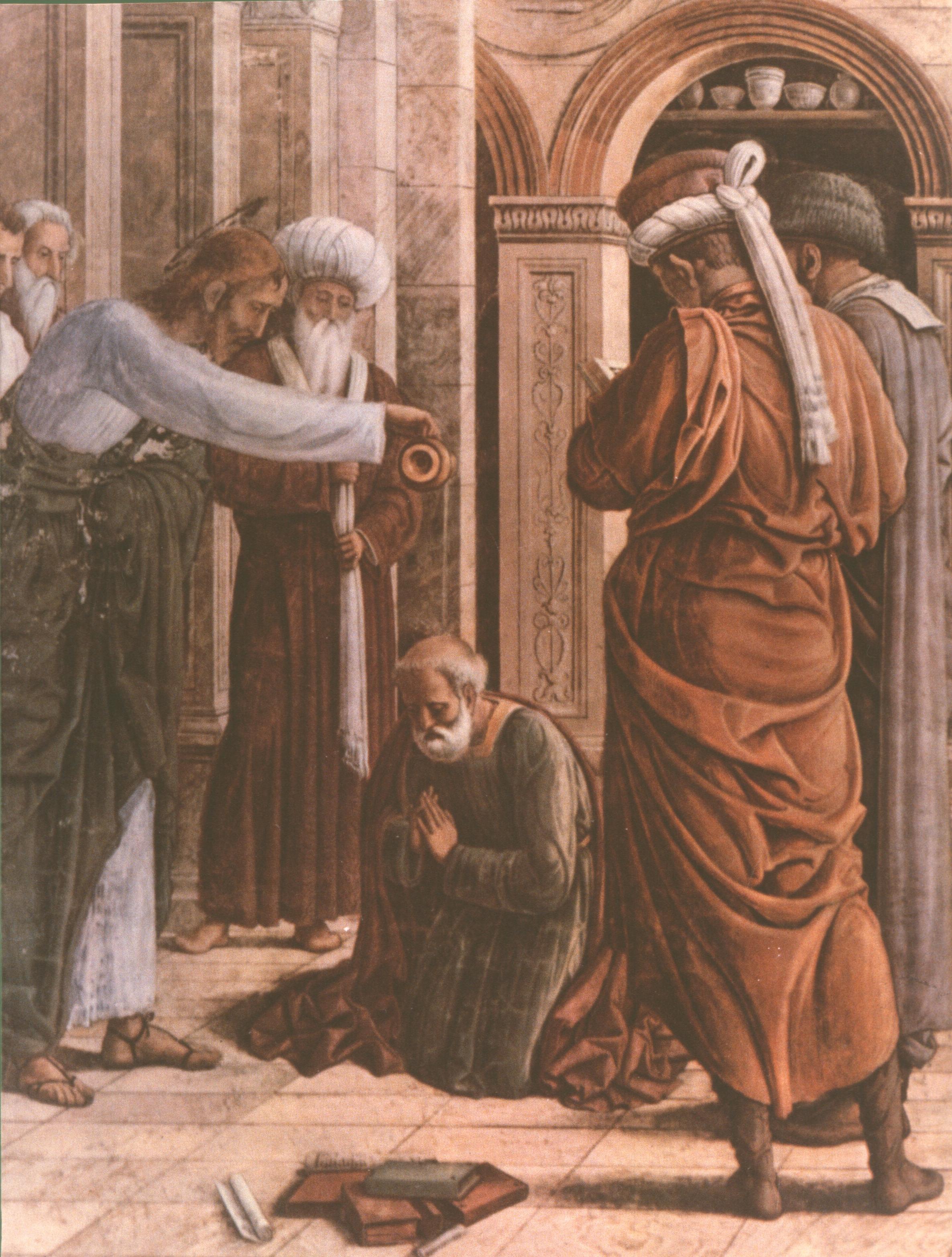

In fig. 15, Hermogenes has already been set free from the demons’ chains by his ex-apprentice (possibly, the young man standing behind the saint). Having forsworn his books of magic (they are lying on the ground, as you can see in the detail in fig. 16), he asks to be ‘received as a penitent’. Mantegna shows James in the act of baptising him, adopting the position in which, in Christian art, John the Baptist baptised Jesus.

This fresco was painted two years after the first pair, and, as you can see, Mantegna is now applying the new methods of strict geometrical perspective formulated by Alberti fifteen years earlier, using the converging orthogonals, and the diminishing intervals of the arches and paving stones to construct a convincing ‘box set’ for a ‘theatre’, and keeping his ‘horizon’ at the comfortable height recommended by Alberti (which coincides with the heads of the standing figures). But notice that he places the vanishing point to the right, outside the picture, inside the frame, and that he uses the pilasters of the frame (which you must mentally supply as you look at the illustration) to ‘cut’ the composition, and so to suggest that the street extends to the left and the right—a feeling which is helped by making one figure look off-stage into that imaginary space.

The other figures (a turbaned oriental, the two men with their backs to us, two youths on the balcony) are intended to direct our eyes to the central scene, although it has to be admitted that the two foreground figures are perhaps a little distracting, as we empathise with the bare-footed, bare-legged boy clutching a gourd, the colours and lines of which are echoed in his doublet, as he gently restrains his toddler-sibling, in his or her tight fitting bonnet and ‘cummerbund’.

The scene immediately to the right (fig. 18) has the same paving stones, converging on the same vanishing point located in the central pilaster; and the scene is lit in the same way (look at the shadows), with the source of the imagined light made to coincide with that of the real light in the chapel, coming from the windows near to the altar to the right. Here, too, there are various invitations to ‘distraction’, in the little-boy sentry in the foreground, under his man-sized helmet, or in the other sentry (the possible self-portrait, fig. 19) looking down at us, or in the figures conversing to the rear.

But our gaze is nevertheless compelled by that triumphal arch, loving and accurately observed from an arch in Verona, with its portrait medallions and relief sculpture/ And this is as it should be, for the arch is a symbol of Roman authority, which is also embodied in the close-cropped figure of the tetrarch, holding his staff of office, and leaning forward from his raised judgement throne, under its anachronistic baldacchino or canopy, with a very convincing sphinx on its side.

The Golden Legend tells us (in an episode clearly imitated from Christ’s appearance before Pontius Pilate) how ‘Abiathar, who was high-priest of the year, incited the populace to riot, caused a rope to be thrown about the apostle’s neck, and had him dragged before [Herod] Agrippa, who condemned him to be beheaded’. The detail in fig. 20 shows the moment when he receives sentence.

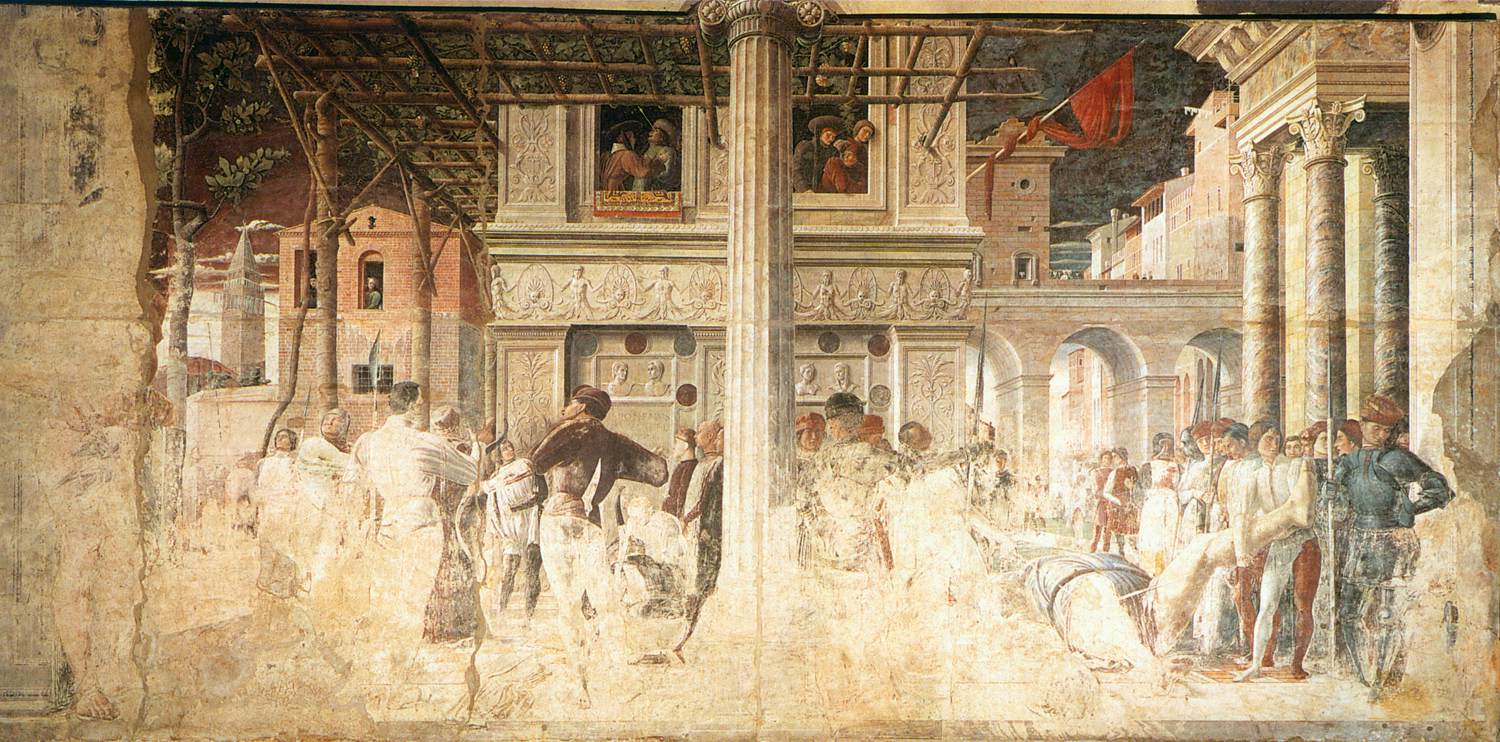

At this point, we should take a look back at the whole wall (fig. 13), to see how these two scenes with the common vanishing point ‘balance each other’, and to remind ourselves of the position of the fifth scene, shown in fig. 21, which follows without a break in the story, but was probably painted after an interval of two years (as late as 1454), and which is very much bolder in its exploitation of the Albertian perspective.

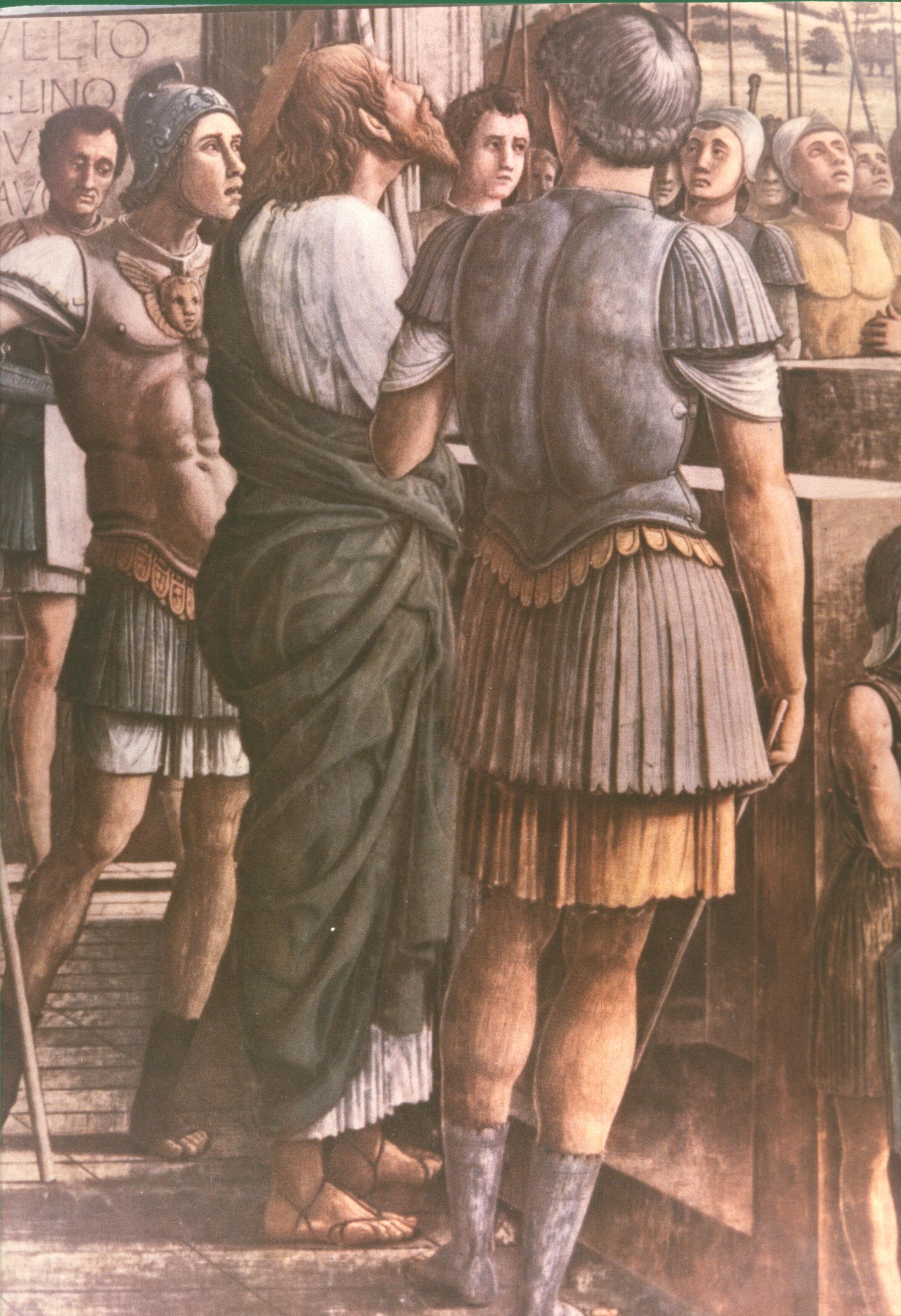

The bottom of the picture lay at about six and a half feet from ground level—that is, about a foot above the head of a real spectator in the chapel. Mantegna has placed the vanishing point of his virtuoso construction at our eye-level, just off centre, so that the ‘horizon’ is actually below the frame of the fresco.

As you can see (fig. 22), the result is that the five almost life-sized figures in the foreground tower over the viewer with disturbing effect, and the great curve of the second splendid arch, steeply and dramatically foreshortened by the low viewing-point, gives great impact to the saint, his guards, and the convert at his feet, in a way that outdoes anything achieved by Donatello and Masaccio.

James is being led to his execution, escorted by Roman soldiers, who keep the crowds back. Nevertheless, he finds time to miraculously heal a cripple by the roadside (the kneeling figure), and to convert and baptise an accompanying secretary who witnessed the miracle—the man to the left with the inkhorn.

The final scene is once again set in the open air, with the city of Jerusalem on the hill behind the huge marble gate in the brick-wall, from which travellers are coming down the road.

A lopped sapling (fig. 24) forms a cross with the pole of the improvised crowd barrier, which is placed right in the foreground, where it could only serve to keep us back from the execution.

Once again, the foreground figures are placed very close to the picture plane—indeed, the visual logic of the intersecting sapling and pole means that the soldier’s left arm is actually in our space—and the horizon is once again very low. But the fact that the horizon lies just above the frame, and the absence of any foreshortened architecture, means that the figures do not ‘press down’ with the same dramatic intensity. The saint is about to be beheaded by a rather nasty instrument—because the executioner is going to bring his mallet down onto the blade of a ‘baby-guillotine’, which will sever the head and the halo, and cause them to drop into the chapel (!).

But despite the fierce expression of the executioner, the scene does not really ‘freeze our blood’. We remain as detached as the three helmet-less soldiers, or the young knight on his white horse (whom we admire for Mantegna’s sheer technical skill in drawing the complex form of the shield), or the balding captain with his five o’clock shadow (fig. 27), who is part portrait, part derivation from Donatello, as he looks down impassively, indifferent to the saint, and indifferent to his rearing horse:

So much, then, for Mantegna at the age of twenty four. He was a master of the innovations coming from Florence, and a notable expert on classical architecture and all things Roman. He was newly married into the Bellini family, and he was therefore brother-in-law of both Gentile and Giovanni Bellini.

We jump forward now into the late 1460s and early 1470s, to a period when he was in his late thirties and early forties, finding him as the established court painter of Lodovico Gonzaga, whose family had ruled the Marquisate of Mantua for about a hundred and fifty years.

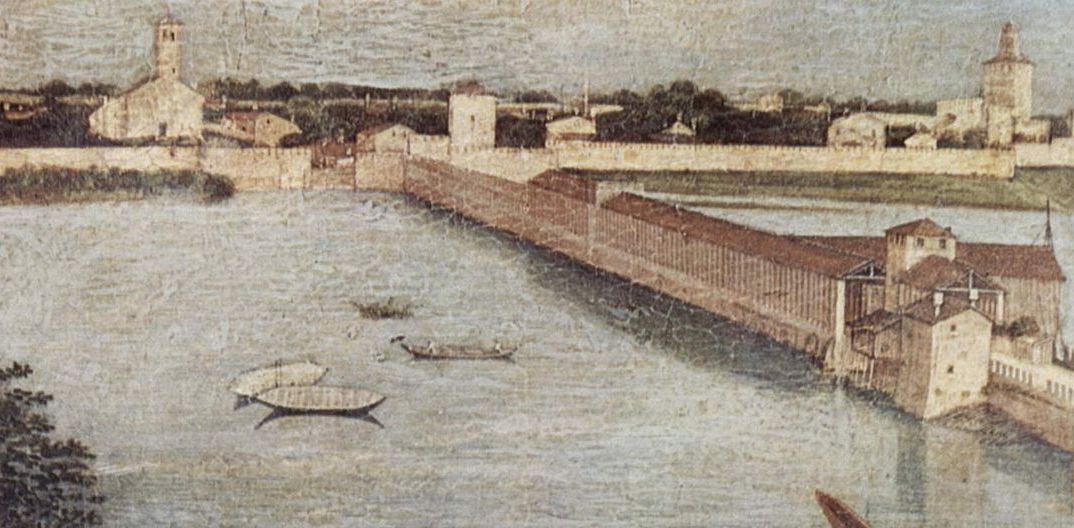

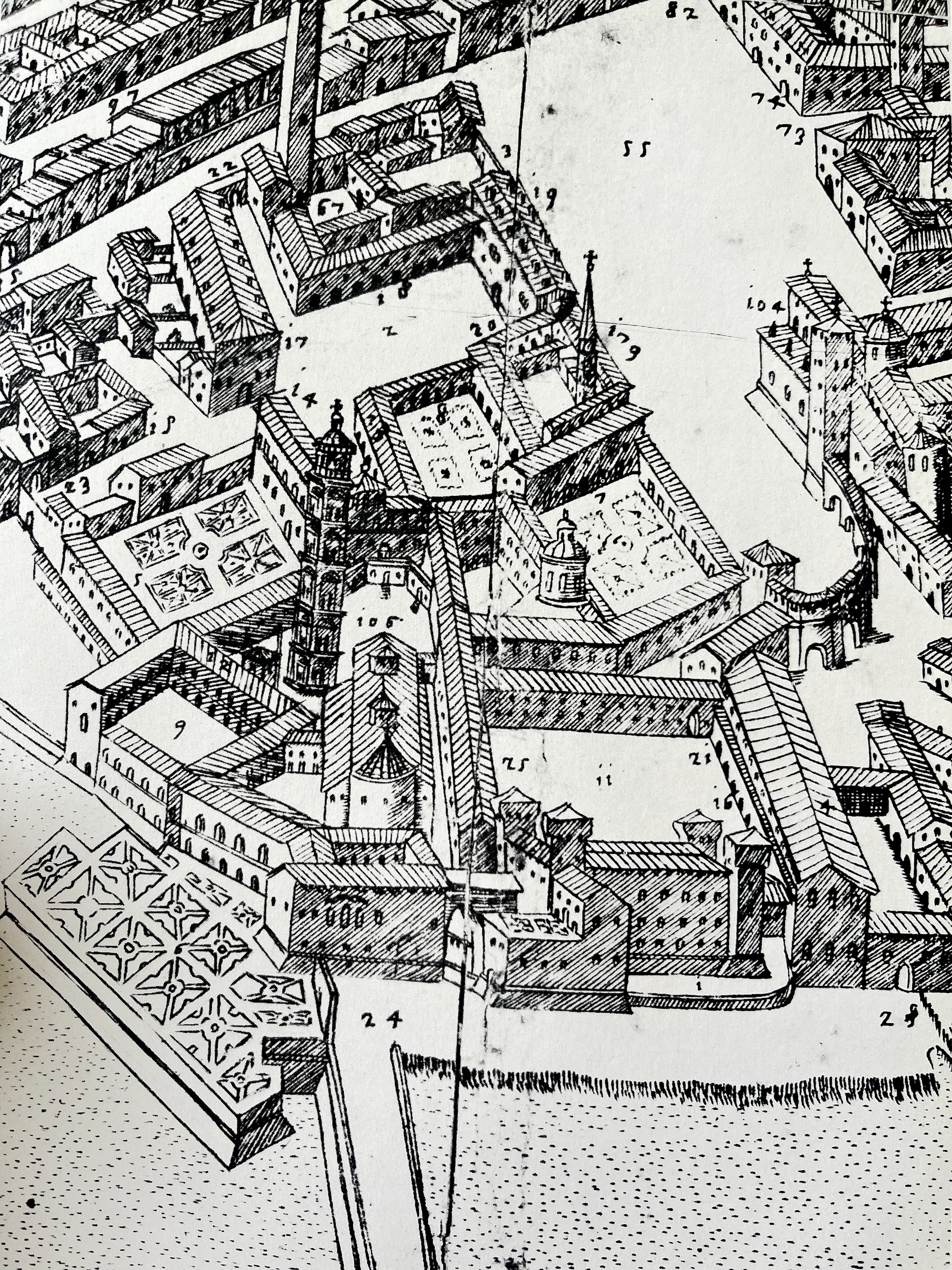

Mantua (fig. 28), you remember, lies about fifty miles west south-west of Padua, around and between three swampy lakes which are formed by the river Mincio. I show you two of the lakes in the modern photograph (fig. 29), while in fig. 30, you see Mantegna’s painting of the central bridge of San Giorgio:

The dominant buildings are the Cathedral (rebuilt to plans by Alberti in these very years) and, to the right of the photograph, the Gothic palace of the ‘Captain of the People’, which is linked by various buildings to the massive brick fortress (characteristic of nearly all of the cities of the Po valley), known as the Castle of St George.

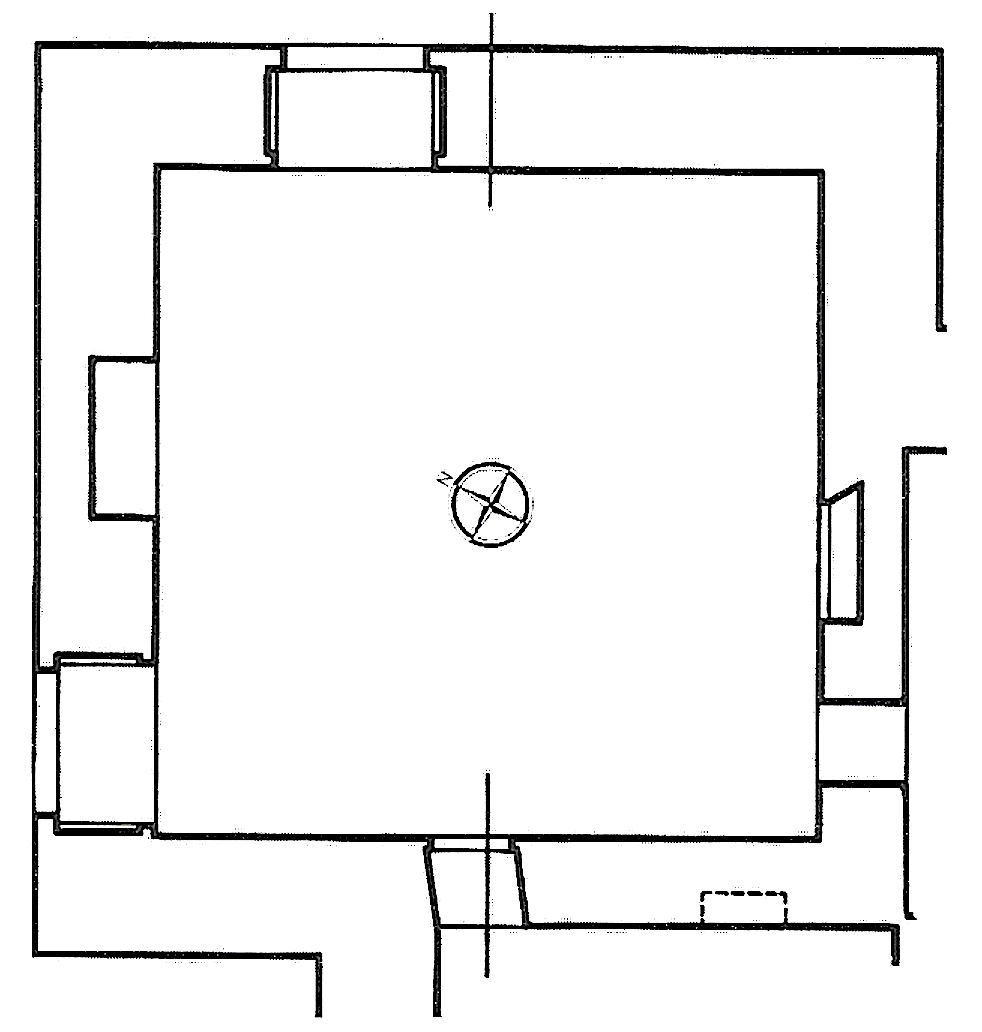

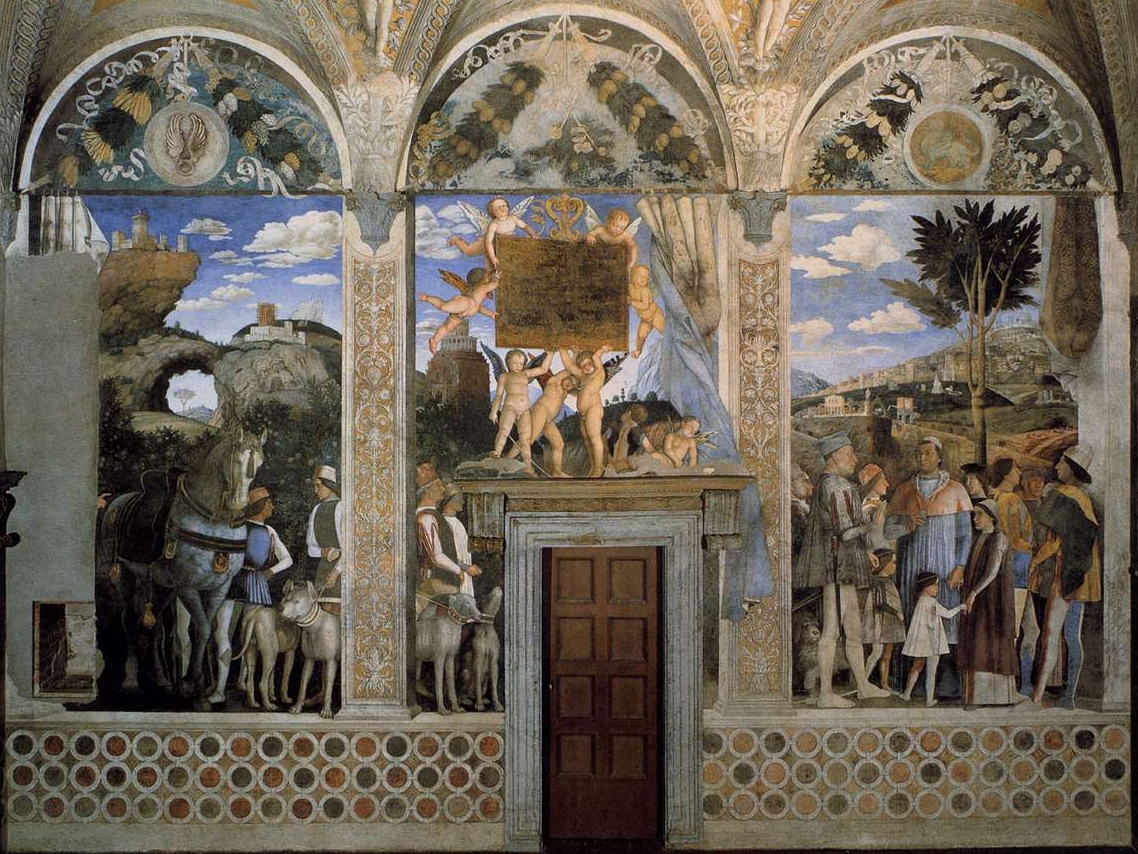

In 1465, Marquis Lodovico decided to transform one of the existing rooms into a bedroom and state apartment that would be both intimate and formal, decorating it with suitably impressive paintings by his court painter. We do not know exactly when Mantegna began his work, but we know that it was not completed until 1474. The room in question—now called ‘La camera degli sposi’, or bridal chamber, but then known simply as ‘the Painted Chamber’—is almost a perfect square, as you see in the plan in fig. 33, and not very big, since each side measures only about twenty six feet.

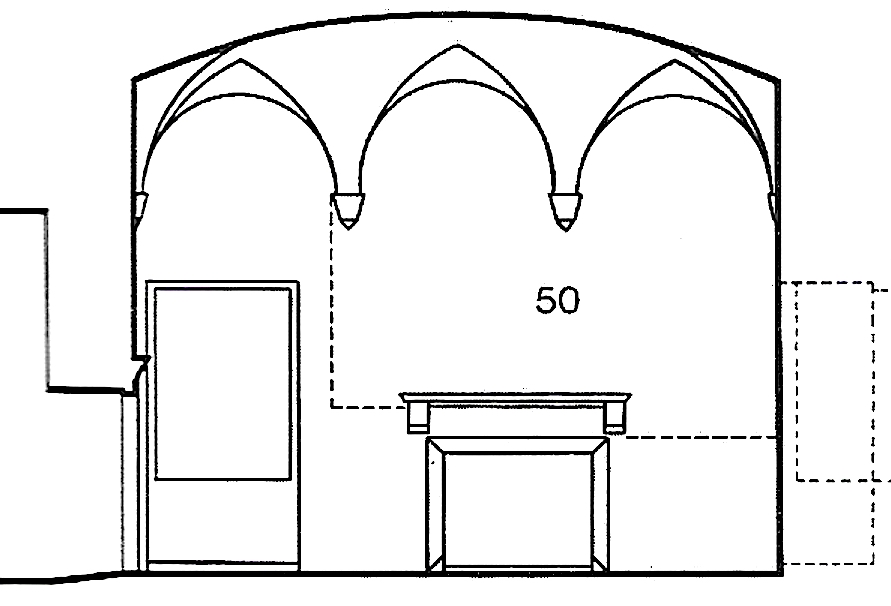

More important, it is almost a cube, since the walls, as you see in fig. 34, rise to just over twenty feet, and the ceiling curves gently up to reach twenty three feet.

It has doors on each of the internal walls (that is to the south, and to the west, which acts as the main entrance), and one window on each of the external walls (to the east and the north). The diagram in fig. 34 is actually of the north wall, and you can see that there is also a large fireplace. The Marquis would normally have sat in the corner facing the north and the west wall, and once Mantegna had finished the work in 1474, this is what he would have seen (with the north wall lying to the right):

As you can see, even at first glance, Mantegna has completely transformed the appearance of the ceiling and the walls, disguising the architectural realities with a brillant tour de force of illusion.

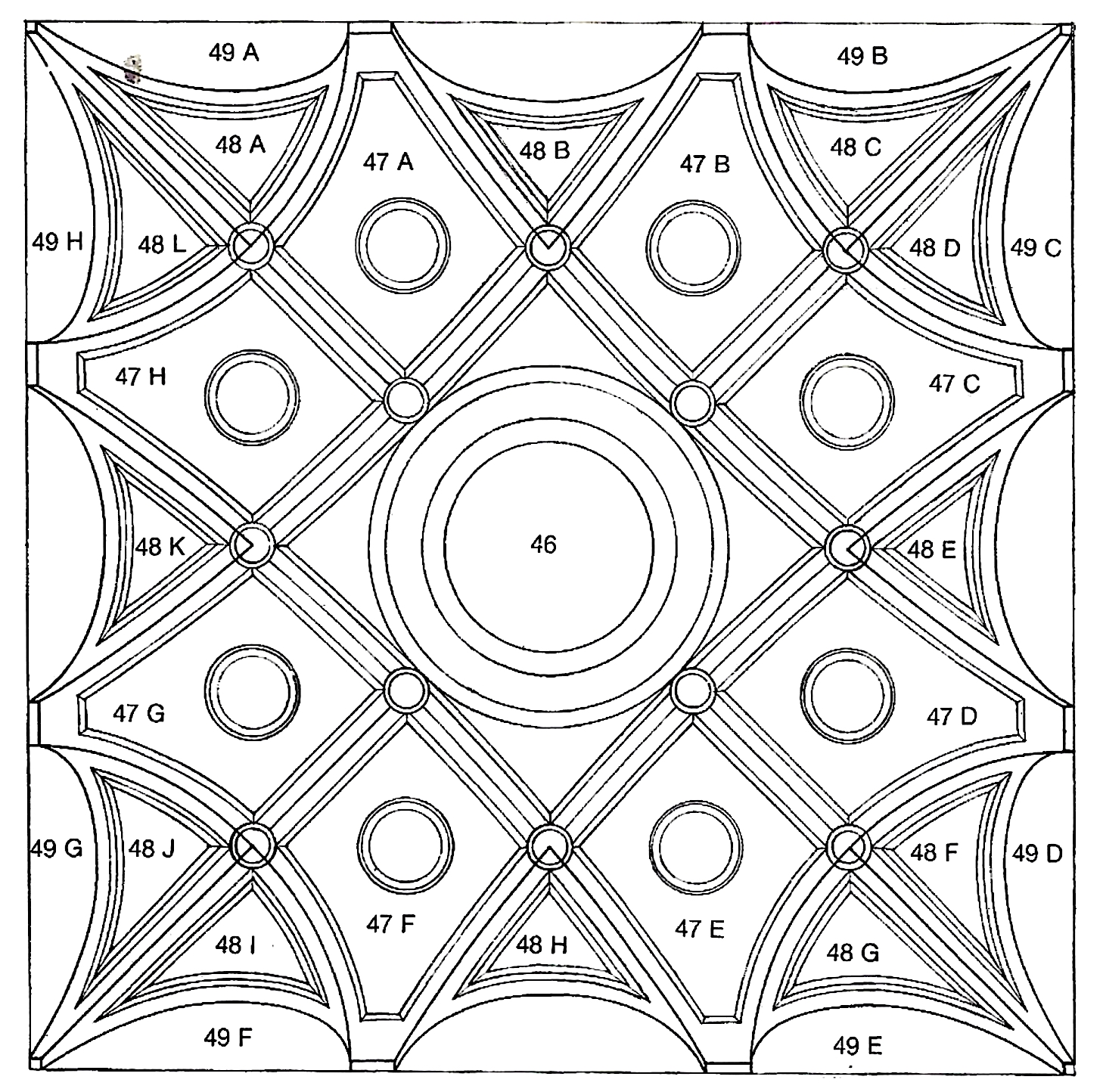

What he does with the ceiling is to paint a most elaborate pattern of ‘ribs’ (best appreciated in a diagram, as in fig. 36), so that the flattish ceiling actually looks like typical Gothic vaulting. The ‘ribs’ themselves are apparently richly decorated with stucco, and the spaces between them are filled with eight medallions, apparently containing relief busts of the first eight Roman emperors, of whom you see the first, representing Julius Caesar, in fig. 37:

In the pseudo-pendentives meanwhile, there are twelve mythological scenes—also apparently in relief—showing three Greek heroes who were very popular in the Renaissance.

In figure 34, you can see Amphion, riding on the back of the dolphin who rescued him after the sailors threw him overboard; Hercules, here wrestling with Antaeus; and Orpheus, here taming the wild beasts with his lyre, an allegory of the power of music and poetry to civilise mankind.

PAT: CHECK THE TEXT HERE. I COULD NOT GET GOOD QUALITY OF ALL THE ONES YOU MENTIONED, BUT CHOSE DIFFERENT ONES

This central, flat part of the ceiling, within the area defined by the fictive ‘ribs’ is celebrated as the most amazing feat of illusionism, not only in this room, but in the whole of Italy in the whole of the fifteenth century. Mantegna makes us believe that it is a cupola, or, rather an oculus, an ‘eye’, which is open to the sky; and he makes us believe that there is a flat roof above, with a terrace garden and flower tubs, from which one can peer down into the room.

Meanwhile, little winged Cupids or putti are floating up and down (another amazing study in foreshortening) and one of them is prodding the peacock with a stick, while on the other side, a Moorish slave with an appropriate headdress peeps over, crouching next to her young mistress who is holding a pole, the other end of which is held by the girls on the other side of the tub.

Across each of the corbels there will be a simulated rod to support simulated wall-hangings, which are apparently made of leather, with gold decoration. And on the south and east walls, that is all there is.

On the other two walls, however, as we have seen in fig. 35, the situation is far more complex. On the west wall, as I will show you more fully in a moment, the wall-hangings are apparently drawn right up to disclose some ‘French windows’, through which we look at a group of men, horses and dogs, who are standing on the ground immediately outside the room.

Meanwhile, on the north wall, there is a group of men and women, apparently sitting on a mezzanine floor within the room, with the wall-hangings drawn partly back to reveal a balcony garden and a glimpse of the sky. Notice, before we look at the group, how cleverly Mantegna has avoided the real window; how he has used the real mantelpiece as his fictive floor, and painted steps leading up to it on the other side of the chimney piece. Notice too—clearer in the detail in fig. 49—that the vanishing point of the perspective once again coincides with that of the viewing point of the spectator in the room, just below the ‘mezzanine’ floor, exactly as it was in the case of the lowest frescos in the chapel in Padua.

At this point, I have to admit that there is not much by way of a story in the two scenes. They are not simply ‘group portraits’, because something is happening in both cases, even if it is only the giving or receiving of a message. But I am inclined to accept the scepticism of Ronald Lightbown (in his superb monograph on Mantegna), and to doubt the received view that both scenes relate to a day in 1461, when Lodovico heard the news that his fourth son had been made a Cardinal, and upon receiving the news, rode out to meet the said son at the family estate of Bozzolo.

It is more likely that the north wall represents a typical scene in the chamber itself, showing the Marquis and his household receiving a not very grand envoy, perhaps from neighbouring Ferrara, which has come up the stairs by the main entrance, and is waiting to be admitted.

The delay in receiving the envoy may have been caused by the letter which the Marquis has been handed by his agent (fig. 52), who has come in by the back way, causing the Marquis to turn round and whisper a reply.

The main interest, however, is not in the two events—which serve mainly to twist those two heads to the right and to the left—but in the superb group portrait, which is arguably the finest thing Mantegna ever did. Lodovico himself, a ruler for the past thirty years (he would die in 1478), is a man of authority but very homely; his bare foot (just cut by the detail) is in a comfortable slipper; his favourite dog is under the chair; and he is clearly on very easy terms with the splendidly characterised steward or ‘agent’, who, we feel, may have been working with his master for most of those past thirty years.

Next to him is his heavily built second son Gianfrancesco. He is looking towards the visitor (and towards the source of the light, which is imagined as coming from the window in the east wall), and resting his hands affectionately on the frail shoulders of his youngest brother, also called Lodovico, who had become a cleric at the age of nine, and was Bishop-elect of Mantua.

The third son, Rodolfo, also a grown man, and also heavily built, stands behind his mother, the Marchioness (fig. 53). Her name was Barbara, and she was a princess of the Hohenzollern family. She sits front on, under her matron’s headdress, with her splendid robe stretching out to the right, while her eyes slip left to her husband and to the letter. She is flanked by her daughter, Paola, kneeling in profile (perhaps a problem child, since she seems a little old to be posed with an apple) and by her dwarf (who seems very pleased to be in the portrait, and is clutching her right forefinger with her left hand); while behind her we see the daughter of marriageable age, called Barbara, like her mother, whose attention goes towards the waiting envoy.

The detail in fig. 54 (with her duenna standing behind) illustrates beautifully Mantegna’s use of a low view-point, his radical simplification of the features in his portraits which is not incompatible with careful characterisation of each individual, and the immense care he took to render the grain of the coloured marble, the pattern of the dresses, and the elaborate hair-do.

The man in black (fig. 55) has recently been identified as no less a person than Leo Battista Alberti. In his later years he was portrayed in a medal by Matteo de’ Pasti, and you can see that the eyebrows and the curl of the side of the nose do seem to match pretty well with what you see in the detail from the painting in fig. 56:

Alberti, I remind you, was one of the greatest men of his time. He had worked on the Cathedral in Mantua, and Mantegna had used his method of perspective. As an admirer and imitator of the Greek satirist Lucian, Alberti may well have influenced the conception of the Camera Picta by calling attention to a description of a splendidly painted, cubic audience-room in Lucian’s work; and he is known to have asked for no other reward from the artists who profited from his works than that they should include his portrait among the bystanders in their historical scenes.

That, then, is the indoor scene, ceremonious but intimate, showing the Marquis doing business, in the company of his wife, two of his daughters, and the three less important sons.

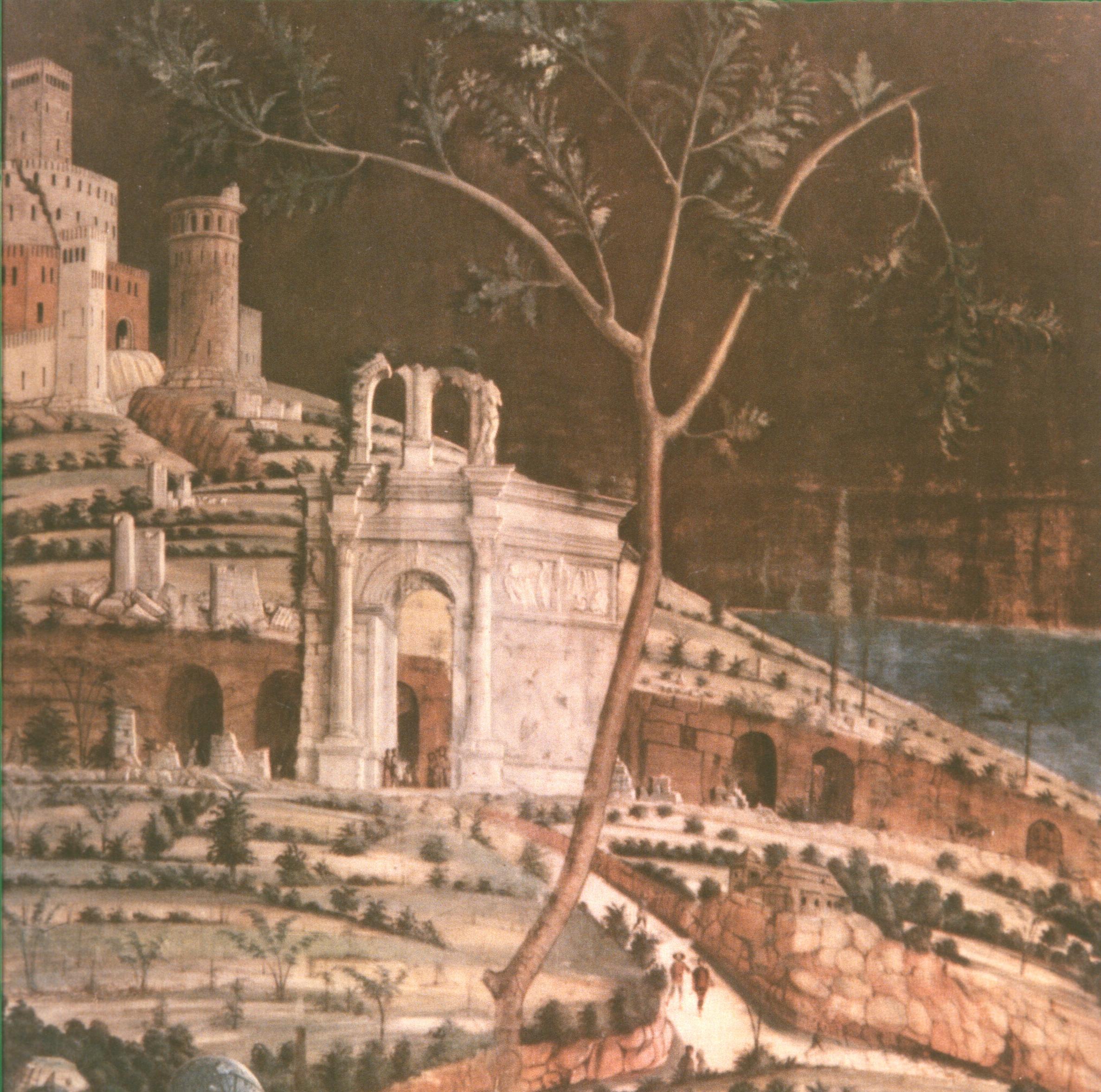

From this, we move to our left, to the west wall (fig. 57), where the hangings are drawn back to reveal horses, dogs, and men standing just outside what I called the ‘French windows’, against an idealised and utterly un-Mantuan landscape, which we are meant to assume is ‘continuous’. Hence we are meant to believe (or not to disbelieve) that we are looking at just one scene, with the two pilasters and the ‘notice-board’ blocking out part of our view.

To the left (fig. 58), we see precipitous crags (but not apparently too steep to preclude buildings and building works); while just outside, between us and the orange trees, grooms are holding the Marquis’s splendid horse and mastiffs (fig. 59): the emblem of the sun on the harness confirms that horse is his.

We see first, Lodovico, in his riding clothes this time, standing in profile, with his thick neck, huge ear, and heavy jaw. His eldest son and heir, Federigo, is in profile facing him, while between them stands ‘his man in the Vatican’, that is to say, his fourth son, the Cardinal Francesco, a worldly prelate, to judge by the portrait, and a good friend of Mantegna’s (the note he clutches says, very simply, ‘Andrea painted me’).

The romantic landscape is vital to the political message, because the buildings represent, beyond all doubt, the city of Rome, with the Aurelian walls, the Colosseum, and the Pyramid of Gaius Cestius (fig. 64). On the gates to the city, Mantegna has painted the arms of the Gonzaga family, who have now ‘arrived’.

But back to the portraits: Francesco is holding his younger brother by the hand (this is the younger Lodovico again, the Bishop-elect of Mantua); and he in turn is holding their nephew Sigismundo by the hand (fig. 65), to indicate that this boy too (Federico’s third son) was destined for the Church (indeed, he too would become a Cardinal).

As I said, it is probably better to discount the traditional interpretation that this scene represents the meeting at Bozzolo back in 1461, when the father rode out to congratulate his son. Rather, it is better to think of it as a day in 1472, during a rare but prolonged visit by Francesco. However, the exact occasion and year do not matter all that much, since there can be no doubt that any visitor to the painted chamber in the 1470s would have understood the fresco as a reminder that the Gonzagas had influence in high places and that they were a dynasty destined to last: we see not only Federigo, Lodovico’s heir, who would rule from 1478–1484, but also another boy standing close to Lodovico who is Federigo’s eldest son and heir Gianfrancesco, who would rule for twenty five years, right down until 1519.

PAT: IS THIS PAGE BREAK CORRECT?

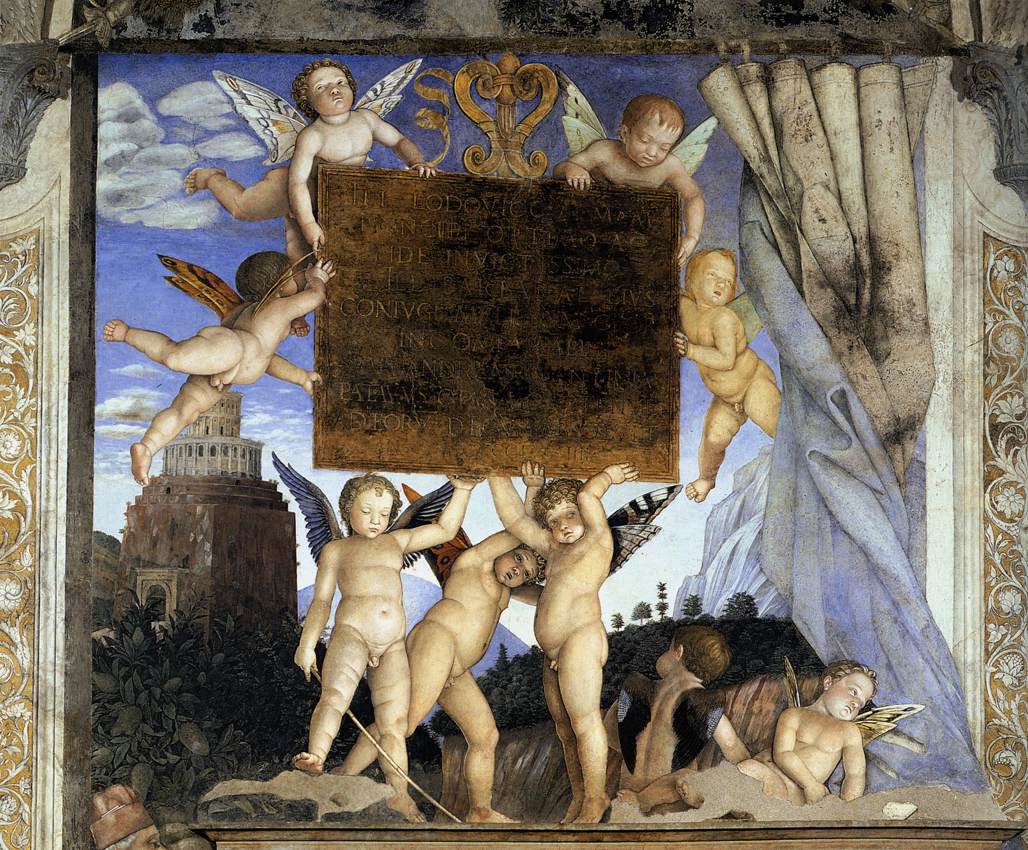

Lastly, a quick glance at the placard or shield in the middle of the west wall (fig. 66).

Even after the restoration, it is not all that easy to decipher, so I have given you a transcription below, along with a translation:

ILL(ustri) LODOVICO II M(archioni) M(antuae)

PRINCIPI OPTIMO AC

FIDE INVICTISSIMO

ET ILL(ustri) BARBARAE EIVS

CONIVNGI MVLIERVM GLOR(iae)

INCOMPARABILI

SVVS ANDREAS MANTINIA

PATAVVS OPVS HOC TENVE

AD EORV(m) DECVS ABSOLVIT

AN(n)O MCCCCLXXIIII

For the illustrious Lodovico

most excellent prince and unsurpassed in constancy,

and for the illustrious Barbara,

his wife, glory of women and beyond compare,

their Andrea Mantegna,

from Padua, completed this slight work

in their honour

in the year 1474

*****

We shall make our third and last major ‘jump’ in time now, coming forward to a series of nine scenes, painted on canvas this time, that were not completed until 1494, when Mantegna would have been sixty three. These were done for Lodovico’s grandson, Gianfrancesco, probably the same little boy we have just seen, who succeeded his father Federick in 1484, when he was only eighteen. He became a professional soldier, like his grandfather; and he married one of the leading patrons of the Arts at the end of the century, Isabella from the Este family, in the neighbouring Duchy of Ferrara.

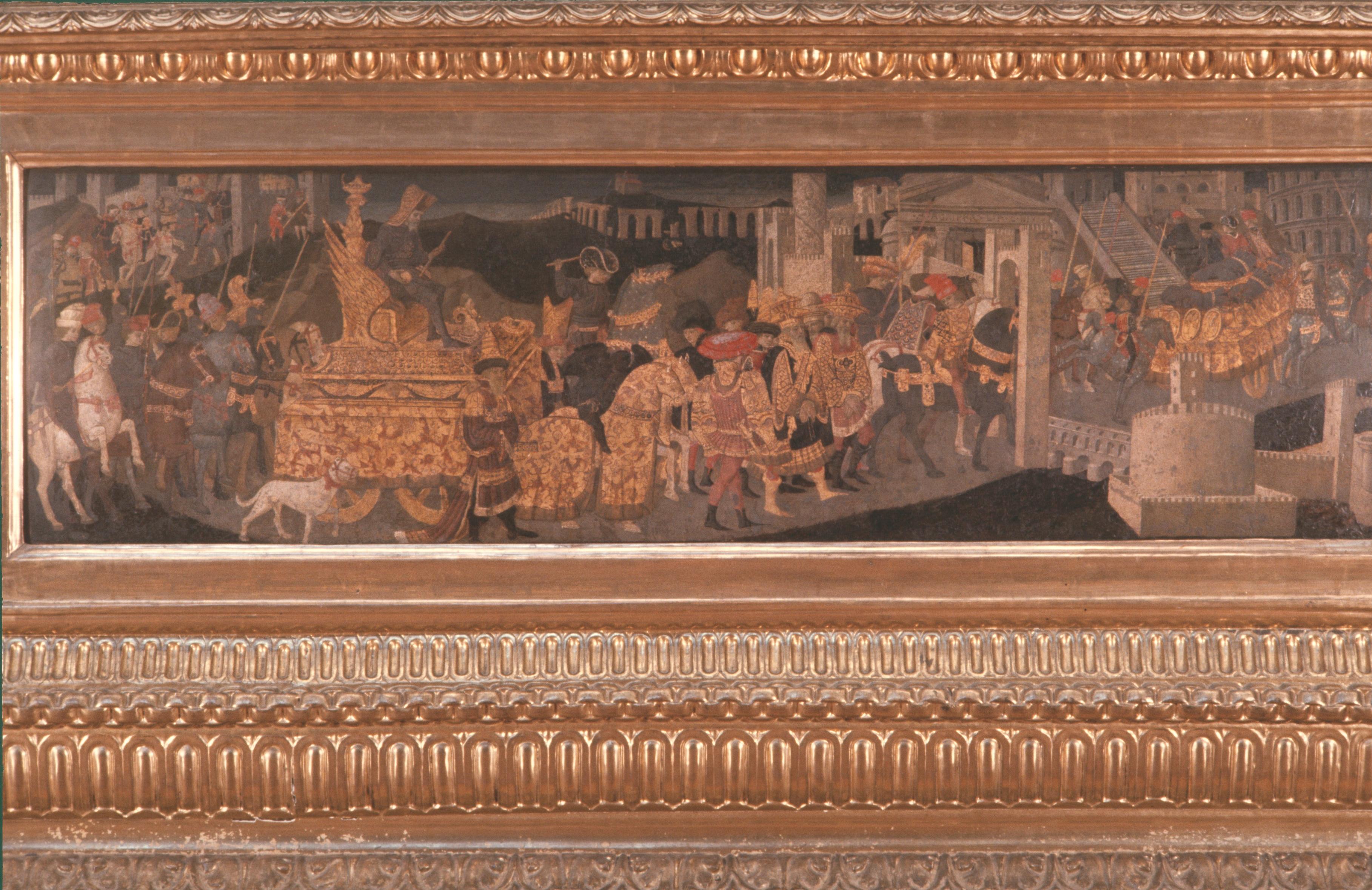

These two facts alone are enough to explain why he commissioned Mantegna to paint a Roman triumphal procession. This kind of subject had long been popular in fifteenth-century Italy, a fact of which I remind you by showing you an image of a cassone (now in the Fitzwilliam Museum), painted in about 1460, which shows Scipio Africanus entering the city of Rome, behind his troops, in a long column with their booty and captives.

Gianfrancesco chose the greatest general of them all—Julius Caesar. And Mantegna conflated the two triumphs that Caesar celebrated for his victories in Gaul and in Asia Minor, using every scrap of literary and archaeological evidence then available (cf. fig. 68) to make his reconstruction of a Triumph as full and as accurate as was possible at the time.

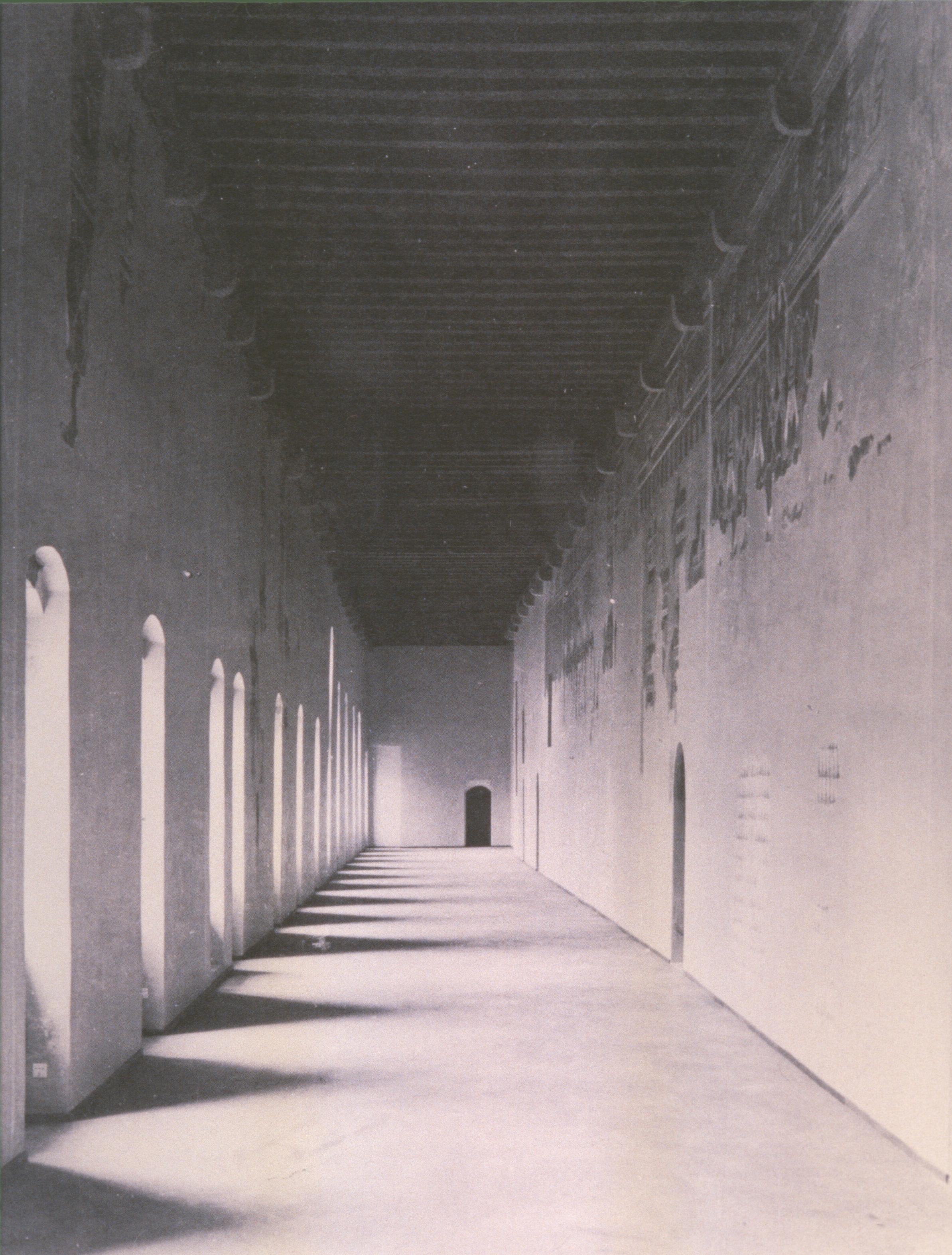

Most recently, in 1986, Lightbown argued for the three sides of a state room, next to the Painted Chamber in the castle. In 1901, Kristeller had argued for an arrangement along a single wall, with the light falling from windows behind the spectator. And in 1979, Andrew Martindale suggested that they may have been intended for the corridor or passage below, which is in the Gothic Palazzo del Capitano that you saw earlier.

It was Martindale’s view that prevailed when the canvasses, which had suffered terribly from damage and overpainting, were cleaned and restored by a single man, working for a period of twelve years, and then put back on view in the Orangery at Hampton Court (fig. 71), where you could see them tomorrow if you were so-minded.

What is certain is that, despite the late date there are striking continuities in composition and style with the works we have seen. Each canvas is nine feet square, the same sort of size as the frescos in the Ovetari Chapel.

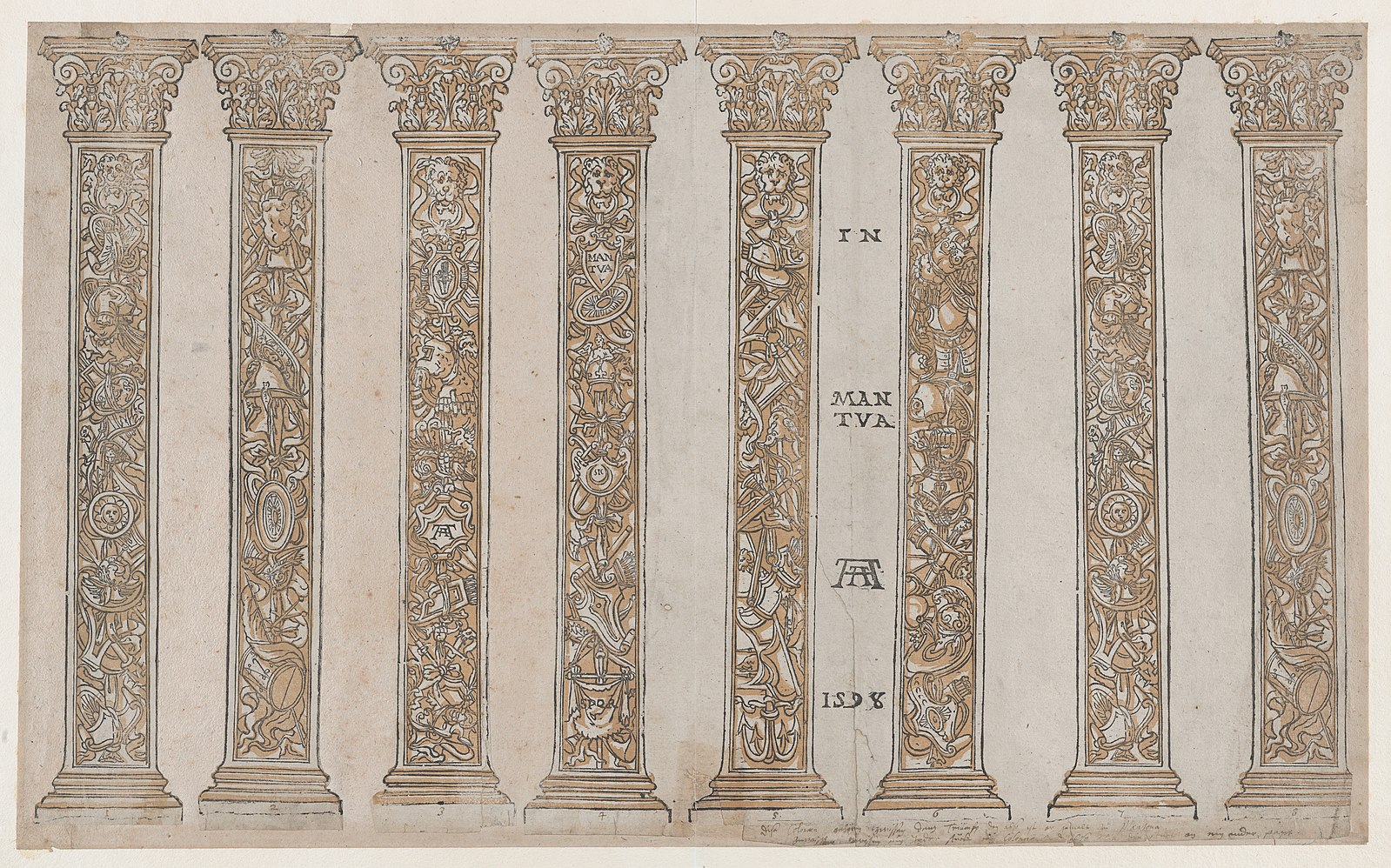

They were meant to be framed by pilasters decorated with classical motifs, like those in fig. 72, which is taken from wood-cuts of the sequence printed in 1589. These pilasters would once again seem to cut off the figures, apparently interrupting our view of a continuous space, just as in Padua and Mantua. The viewing level (and thus the height of the vanishing point in the perspective) is, once again, close to the bottom of the frame, so that we seem to be looking up to the foreground figures, whose feet we could almost touch with our hands—everything and everyone being foreshortened from below.

There is not really any ‘story’ to tell, so I will be content to more or less allow the procession pass by, like ‘floats’ in a Carnival or at the Lord Mayor’s show.

Here (fig. 73) is the first canvas, showing the front of the triumphal procession. Trumpeters lead the way, dressed in long robes and wearing boots, their brows crowned with laurel, their cheeks puffed out, and the long trumpets making an angle of about thirty degrees (fig. 74).

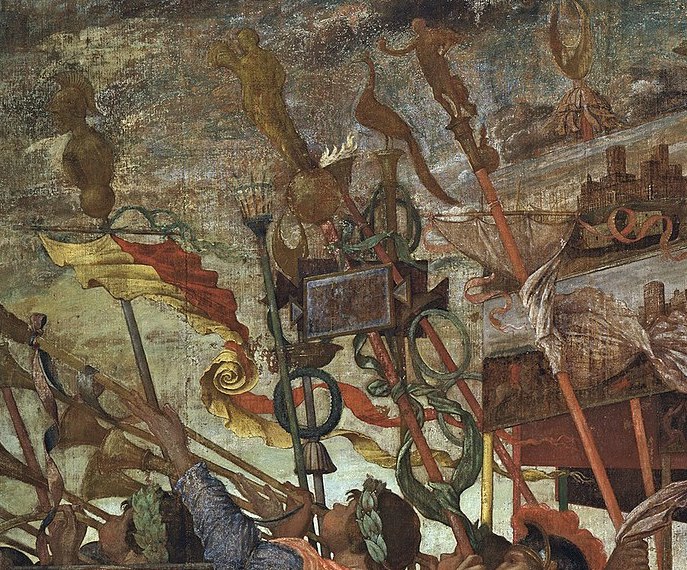

Behind the trumpets, making an angle of about seventy degrees, you can see a half dozen scarlet and green poles, with banners or standards which reach right up to the top of the canvas.

Behind them, on yellow poles, held vertically, in pairs, there are huge pictures of the captured cities (fig. 75), which are stretched right across the width of the marching column, and would have been almost invisible, because sideways on, were it not for the fact that the soldier in green has checked his stride, looking behind him (that is, in the same direction as the mounted officer, and the splendid African soldier, with his ornamental breastplate, and very flattering yellow robe).

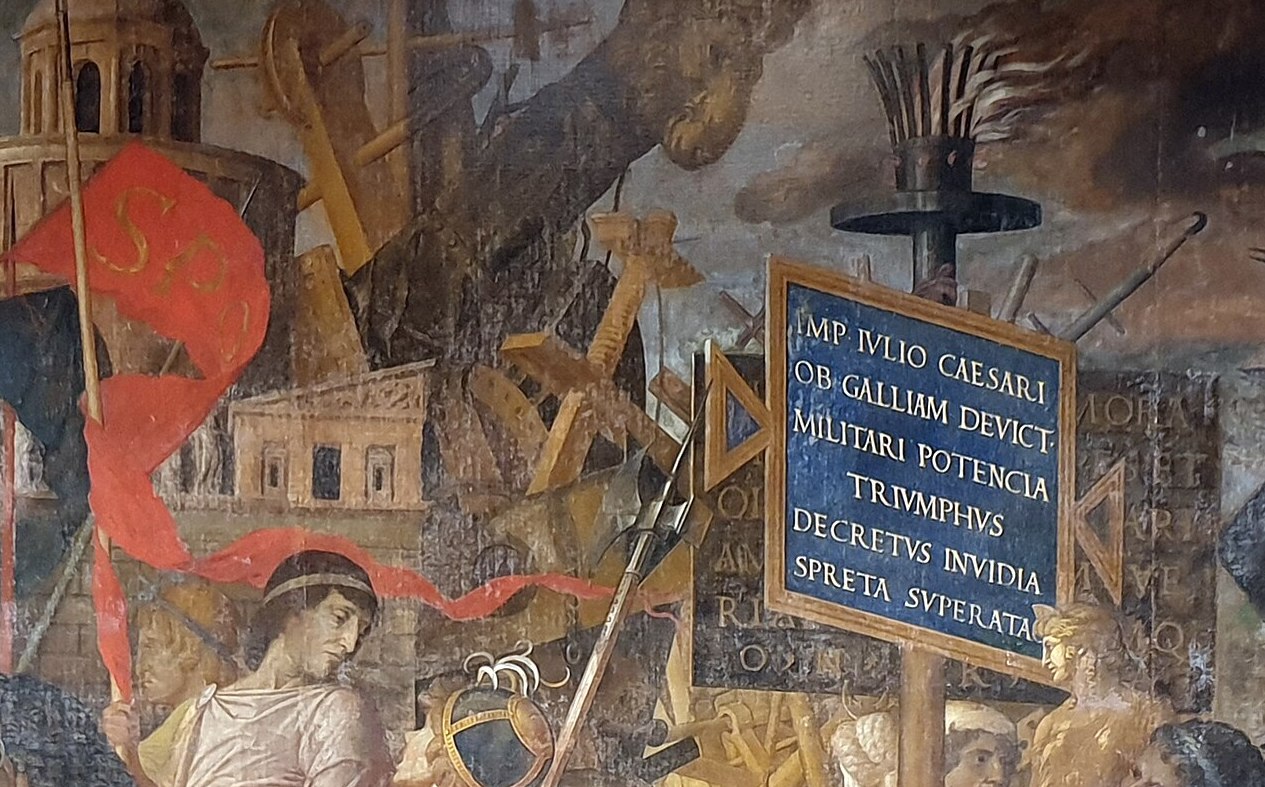

All three of them, then, are directing our gaze to the canvas ‘behind the pilaster’, where the sky is the same evening sky (specified by the historian Suetonius for Caesar’s Gallic triumph), which explains why there is a huge torch illuminating the foremost of two inscriptions, which spells out that the picture represents (cf. fig. 78):

a Triumph,

decreed for Julius Caesar,

because of Gaul conquered

by military might…

This part of the procession is reserved for captured statues of the defeated gods.

One of them is a huge bust of Cybele; another is a full length bronze, about three foot high, being carried by the soldier in yellow; and the leading one is a gigantic bust riding on a cart. Notice here that there are only two pairs of human legs visible in the ‘touchable’ foreground plane, because this is an area of wheels and of animals—like the horse, the wolf-hound, and the ox’s head.

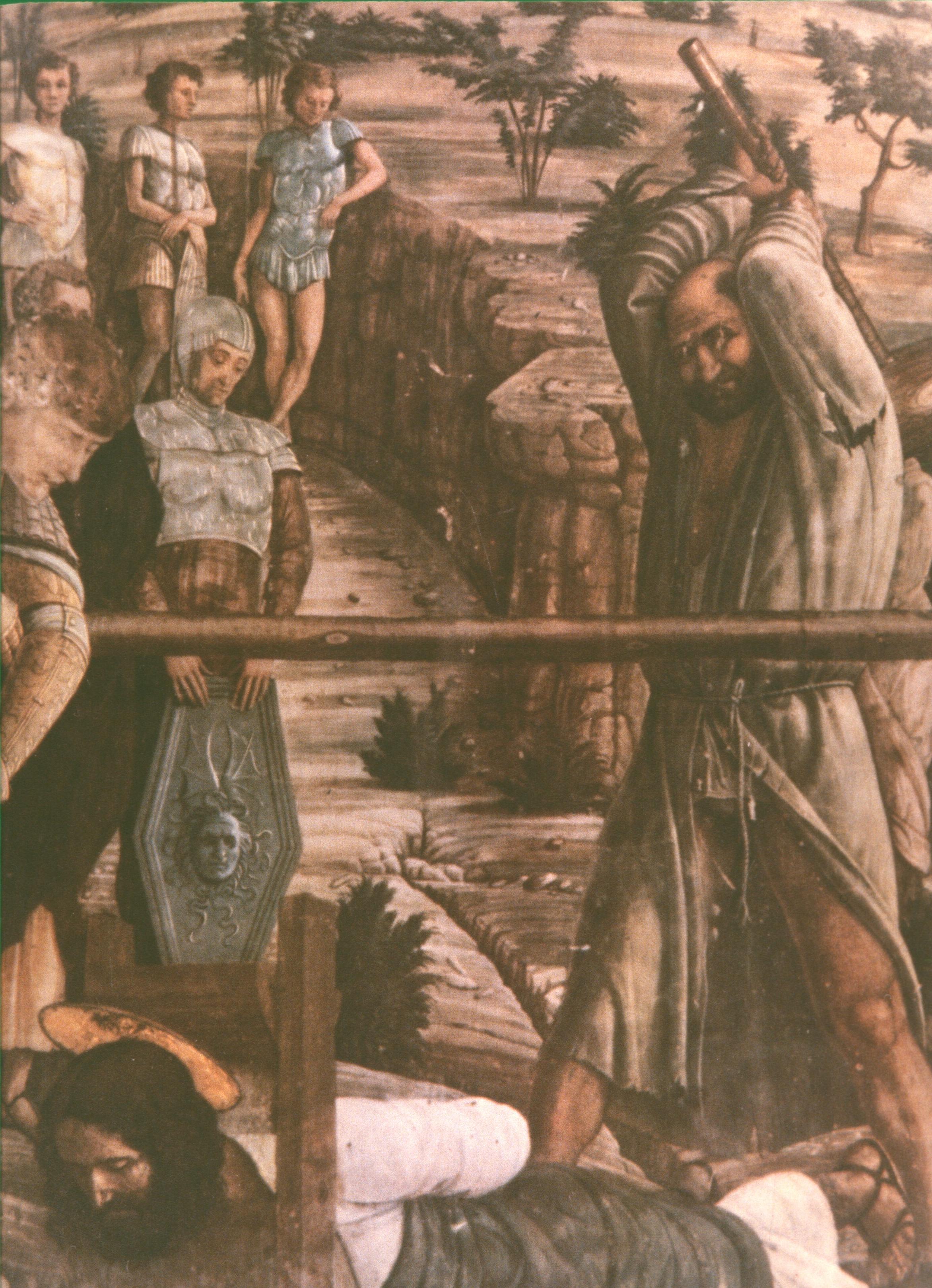

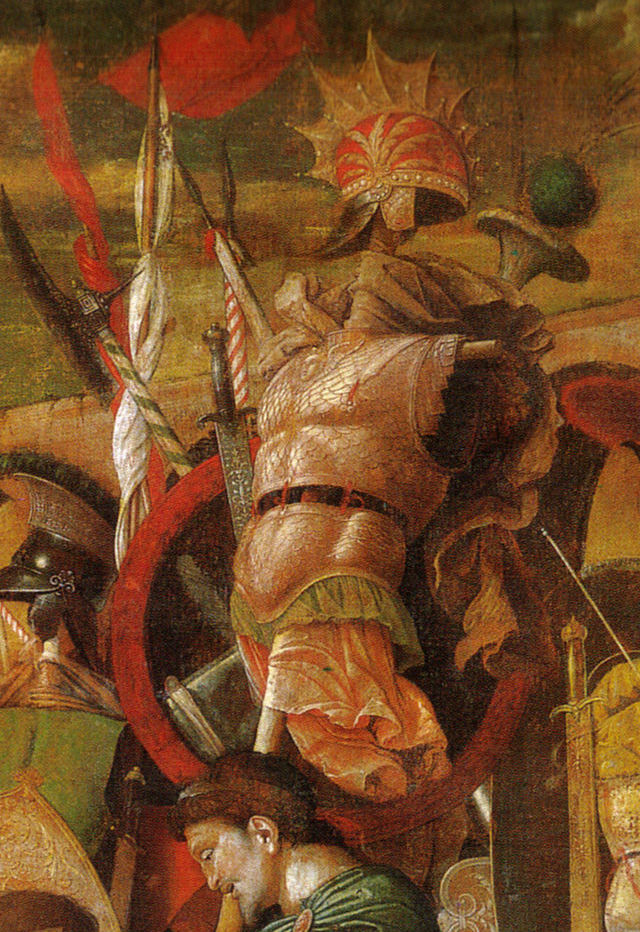

Indeed, it is a carved animal head that towers over the upper register here, this being the gigantic ram’s head of a ‘battering ram’, which appears among other items of siege equipment and models of captured buildings. To the very right, you can see helmets and shields; and it is the captured pieces of armour that dominate the same twilight sky in the third canvas (fig. 79):

This is one of the more damaged canvasses, and the dense colours make it rather difficult to ‘read’ all the meticulously rendered still-lifes. But you should be able to pick out the anachronistic halberds, the variously shaped helmets seen from various angles, and the pattern formed by the short swords and breastplates suspended on that crossbar held by the dreamy youth.

After the armour piled up on the ox-cart here, we come (still in this third canvas) to the first of two ‘litters’ or ‘stretchers’, laden with magnificent vases and pots, some of which are also being carried by hand.

The cut-off rear of the first ‘litter’ provides continuity with the cut-off front of the ‘litter’ in the fourth canvas that leads out of it (fig. 80), the ‘litter’ being accompanied by an old man, who is embracing the most sumptuous vase in the whole pageant—it is worth going to Hampton Court just to see that vase as it really is (fig. 81).

A second group of trumpeters produce another pattern of angled trumpets to which are attached banners that remind us of the ‘Senatus populusque Romanus’, and, of course, of ‘Julius Caesar’. Then our eyes travel to the right yet again, where the ray of sunlight that caught the vase illuminates the youth escorting the first of two oxen, which are clearly not just beasts of burden, but victims decked out for a solemn sacrifice (fig. 82).

Once again, Mantegna takes pains to make us believe in the continuity of the space between the (non-existent) ‘pilasters’ that ought to ‘interrupt’ our view of the procession.

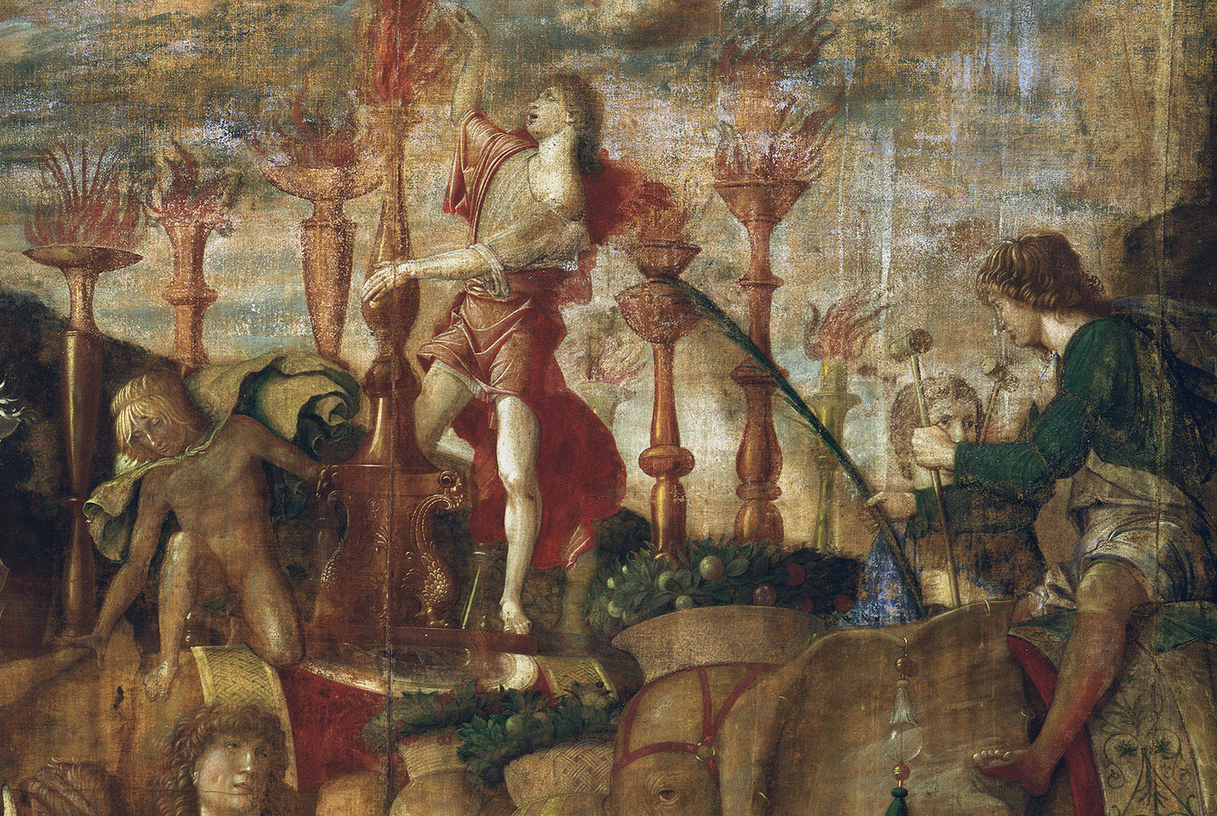

The sky line (in fig. 85) climbs high to the classical buildings on the left of a hill; it continues at the same height past a much more medieval looking tower, before dipping again to show us the evening sky, and then rising steeply again to the right. Notice, too, how the shaft of light which lit up the first sacrificial ox and its attendant now lights up the second, and how both ox and youth are turning their heads to direct attention to animals that are somewhat more exotic than dogs, horses or oxen (fig. 84).

What we see are elephants—African elephants—with huge ears, ridden by mahouts (two of whom are deep in conversation), and caparisoned in splendid hangings. We have seen flaming torches before, but never so many as in this area.

Nor have we seen a youth leaping up to refuel the torches (fig. 85), or perhaps to adjust the height of the flame.

The sixth canvas maintains the illusion of interrupted continuity, as we are shown just the rump of a retreating elephant, and more high ground to the left. The sky line is then varied with three new features: trees, on the high ground; an equestrian statue on a column; and then the straight line of a Roman aqueduct, from which spectators are looking down on the column—and down on us. The aqueduct is not parallel to the picture plane, and Mantegna introduces yet more variety by making it seem as if the marching column has come through one of the arches towards us, and is now turning a corner to march along parallel with the aqueduct in the very middle of the scene. The three soldiers in the foreground are contrasted not only in their direction of travel but in their ages and their attitudes; and the central soldier is certainly a splendid figure. In the last analysis, though, the most memorable features in this part of the Triumph are not in the background or the foreground—not in the architecture or the human beings—but in the marvellous still-lifes, with their complex, multi coloured surfaces caught by yet another ray of the setting sun.

We see vases, plate and jewels on a ‘litter’; and, most strikingly of all, complete suits of parade-ground armour—‘trophies’ in the original sense of the word—especially, perhaps, the breastplate and helmet in fig. 87, which is the finest single detail in this whole lecture:

The seventh canvas has suffered so badly over the centuries that it has been taken out of the procession at Hampton Court, and what I show you here is a photograph of the early engraving:

It shows the captured leaders and their families, and it was greatly admired by Giorgio Vasari. But, alas, there is no point in dwelling on our loss, and we must simply move on to the next ‘float’ in the procession (fig. 88). It too has been heavily overpainted, so I give you the engraving again alongside.

It is helpful to interpret the scene as a reflection of Caesar’s second and almost contemporary Triumph, which was awarded for his three-day victory in Asia Minor (this was the ‘Blitzkrieg’ of which he gave the famous description: ‘I came, I saw, I conquered’). Such an interpretation would explain why we have no fewer than four heads of the goddess Cybele; why the musicians are playing a lyre and a timbrel; and, why, in the case of the dancing oriental figure, he is playing a loud and raucous shawm.

Once again Mantegna is concerned with the link to the final canvas. The third group of musicians here herald the coming of the triumphal chariot itself, whose rumbling wheels are clearly catching the attention of the two soldiers, who are supporting more banners, standards, and images of captured cities.

The direction of their gaze is continued in the final scene (fig. 89) by the handsome youth who forces our eyes upwards, past the splendid horse and an uninterrupted view of that lofty chariot, towards Julius Caesar (fig. 90).

He is holding a sceptre and a palm branch, while the imperial crown is being held over his balding head by an attendant; and it will not surprise you that Mantegna reserved for this last scene the architectural structure which was most closely identified with Victory and with Rome, the ‘Arch of Triumph’, which had haunted his imagination since he was in Padua forty years earlier.