Titian: The Studiolo of Duke Alfonso

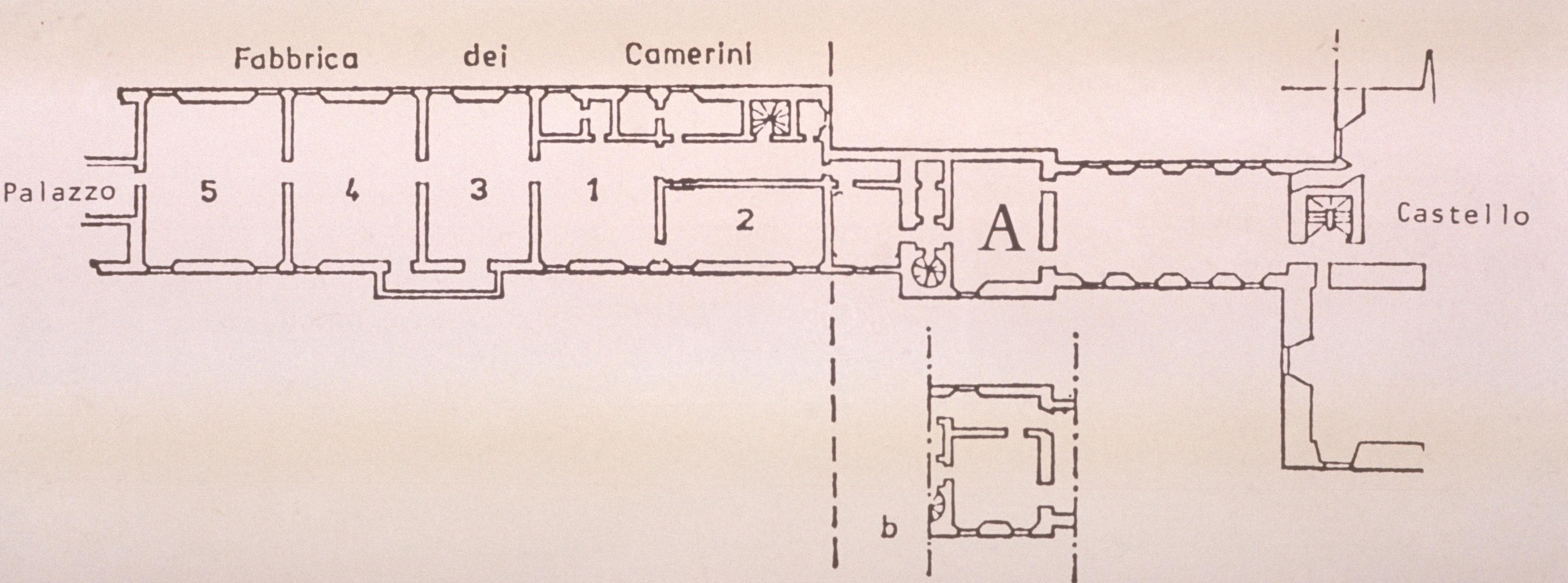

In this lecture, we will be looking at two cycles of paintings, both of them done for Ferrara, which—as you can see the map (fig. 2, right)—lies about 50 miles from Venice, on the South side of the Po, and about 40 miles from Mantua. In many ways it is like Mantua: it had about 25–30,000 inhabitants at this time, its buildings are largely of brick, and it is dominated by a huge brick castle built in the late fourteenth century.

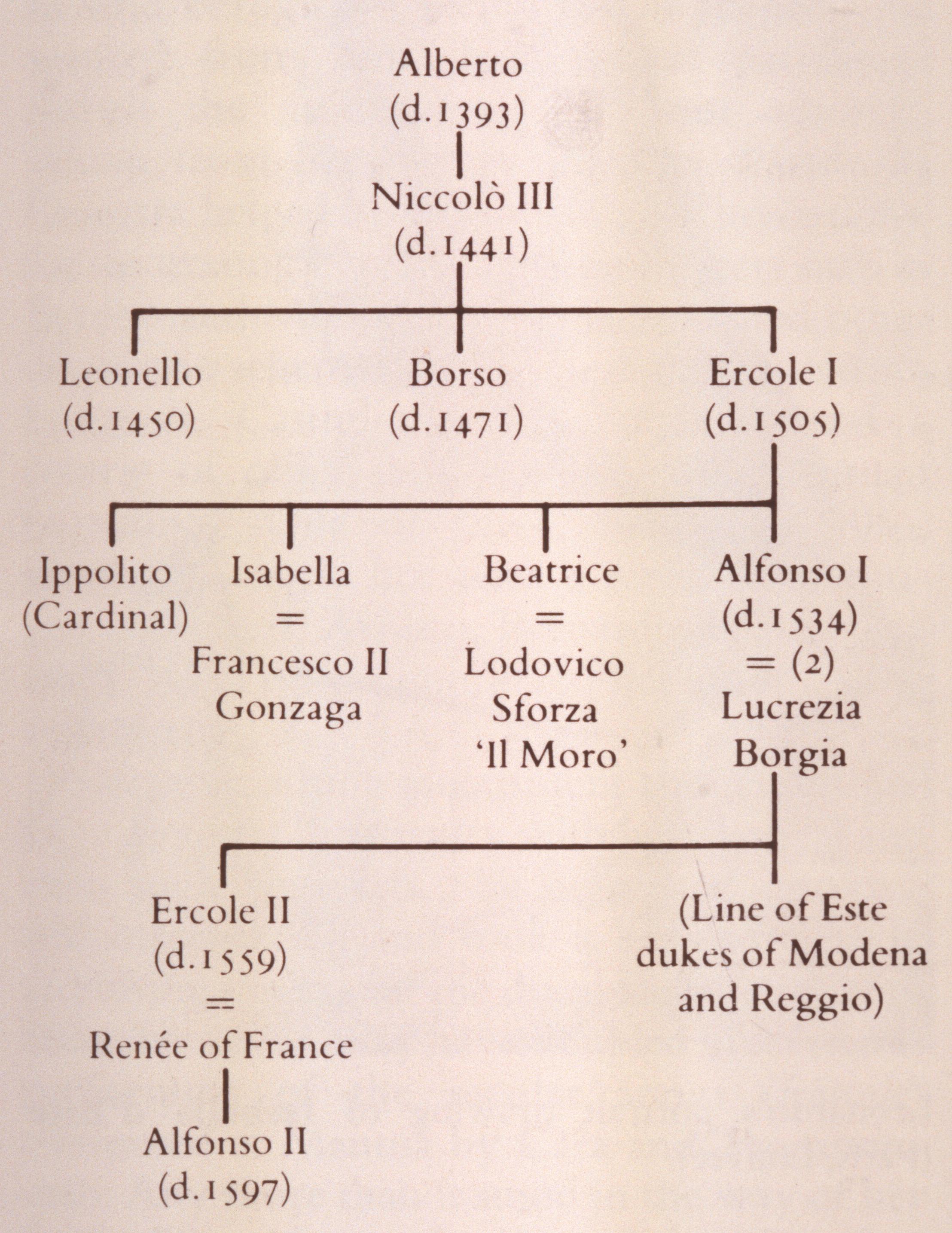

It was the seat of a Marquisate that became a Duchy, and in the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries, the Duke of Ferrara ruled over a vast tract of land (shown in purple), extending right across the peninsula, controlling all the main routes from the North to the South. Like Mantua, the city and the contado had been ruled throughout the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries by members of a single family—the Estes—and finally, the sons of these two families (the Estes and the Gonzagas) were among the first future rulers to be sent to one of the new humanist educators—men like Vittorino and Guarino—and they too became important patrons of the Arts.

The first Este to make his name as a patron was Lionel, Lionello (fig. 3, right). He was born on the wrong side of the blanket, but succeeded his father in the 1440s, when he called in artists such as Roger Van der Weyden, Jacopo Bellini and Pisanello (who did both the portraits in fig. 3). In 1450, he was succeeded by his brother, Borso, also illegitimate, who ruled until 1471.

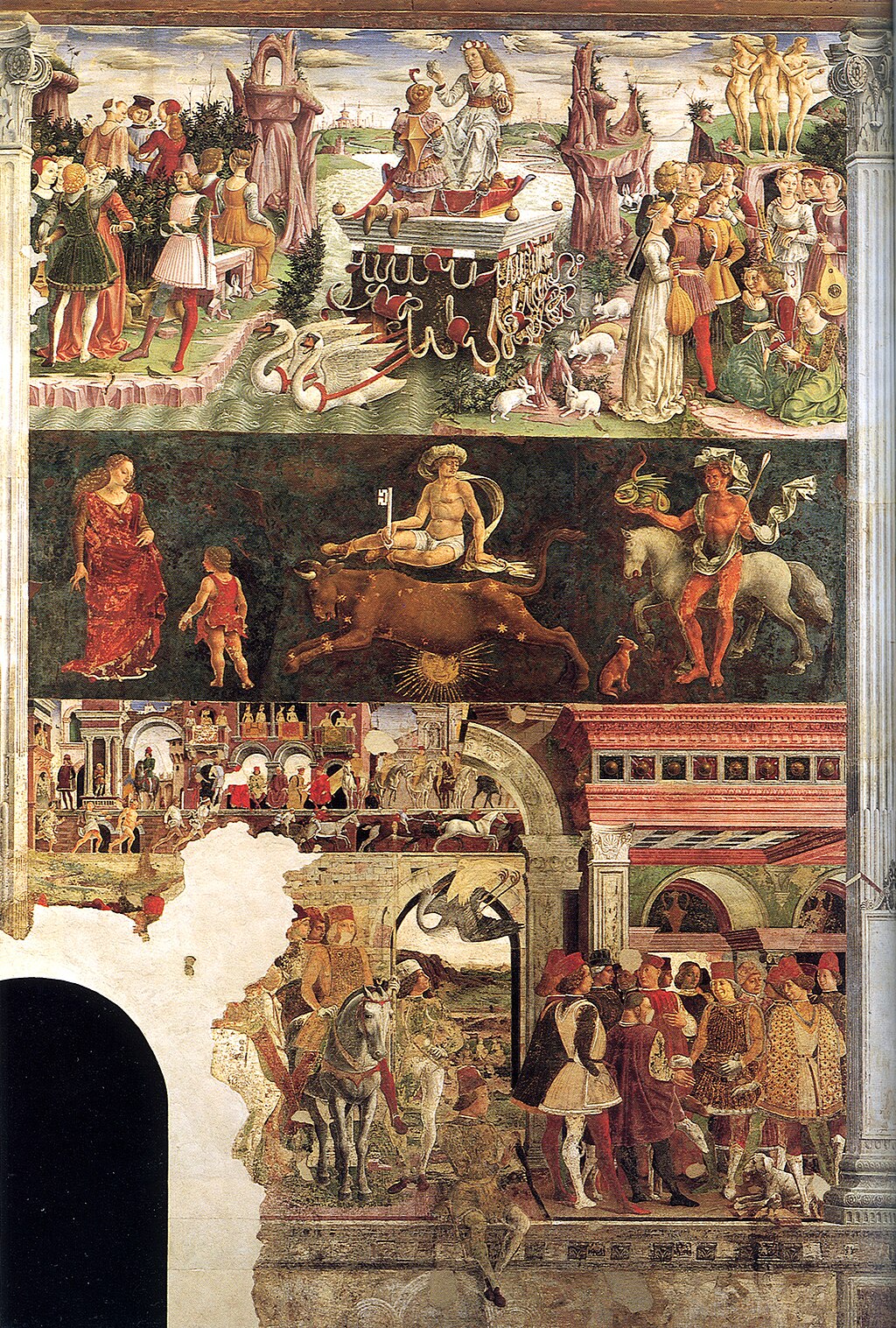

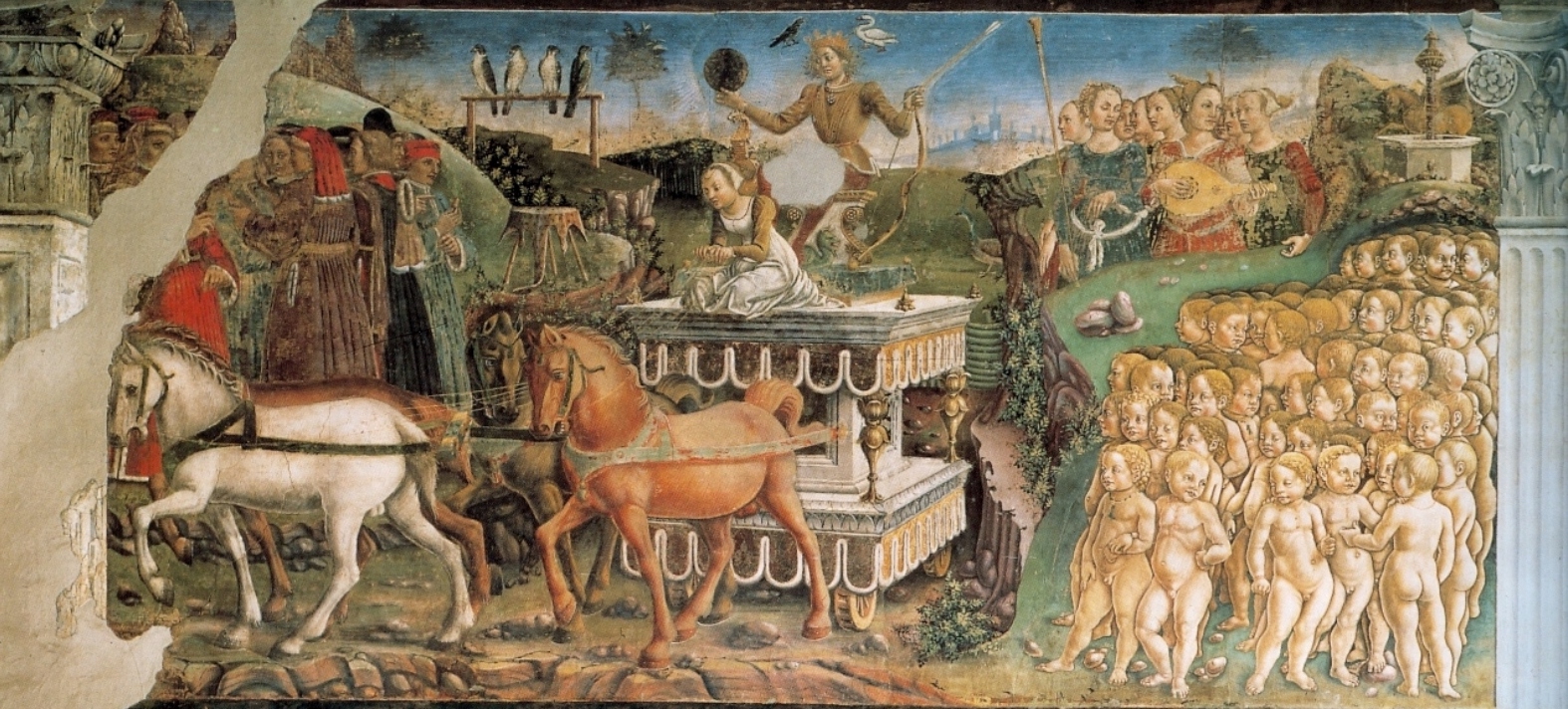

It is rather a grim looking building on the outside, but as the name suggests, it was intended as a pleasure palace; and in the 1470s, the main room on the first floor was decorated with a superb set of frescos by local painters—that is, Ferrarese painters, led by Francesco del Cossa. The frescos have suffered very severely from damp and neglect, but I am going to spend a fair part of this lecture on this earlier cycle, because it introduces many of the themes of Titian’s paintings, because it offers a wonderful foil to his style, and because, even in its damaged state, the room is still well worth a visit.

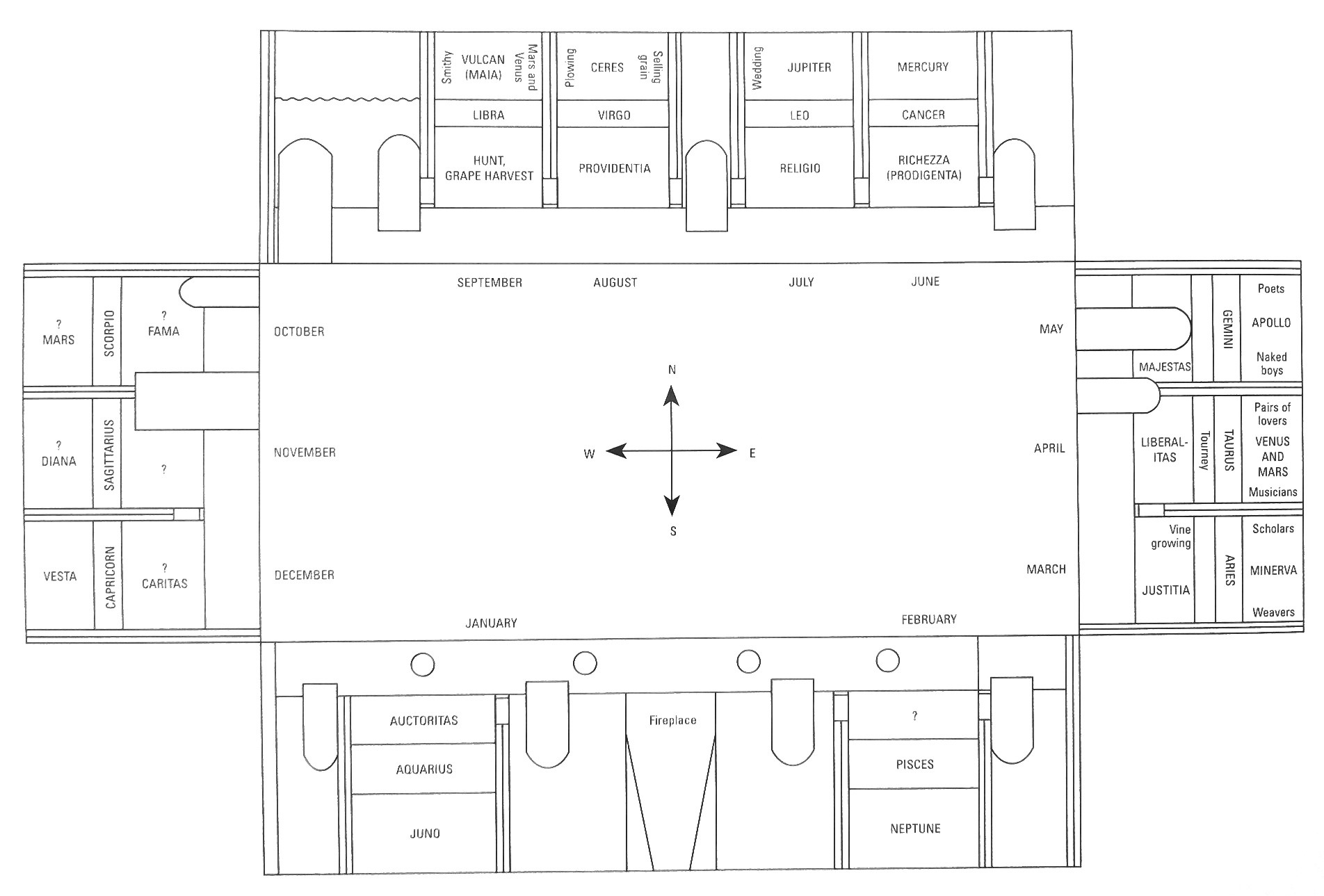

There are four windows on the south wall, corresponding to the four you saw on the façade; and the frescos are laid out in twelve ‘zones’, three on each of the shorter walls, four on the North wall, and two on the South wall. Each of the twelve zones is divided into three horizontal bands, as you can see in fig. 9 (light, dark, light); and each zone is dedicated to one of the twelve months in the year.

To be more precise, each zone is in fact dedicated to one of the twelve signs of the Zodiac—and what you see in Figure 00a FIXME on the right end of the North wall, is not June and July, but Cancer and Leo. The figure representing the ‘sign’ itself is always represented in the very centre of the central zone.

This is why the cycle begins with Aries the Ram, that is, with the Spring equinox, which is represented on the East wall. And this is why the sequence unfolds from right to left, in the order Taurus, Gemini, Cancer and so on (since the observer in the Northern hemisphere will always see Taurus to the left of Aries, Leo to the left of Cancer etc.). In Palazzo Schifanoia, the twelve ‘signs’ are linked to twelve of the classical gods and goddesses, in a scheme that goes back to the early first century AD. Hence those deities who had already been identified with the planets (for example, Mercury, Venus, Mars and Jupiter) are joined by Ceres, Vulcan and others.

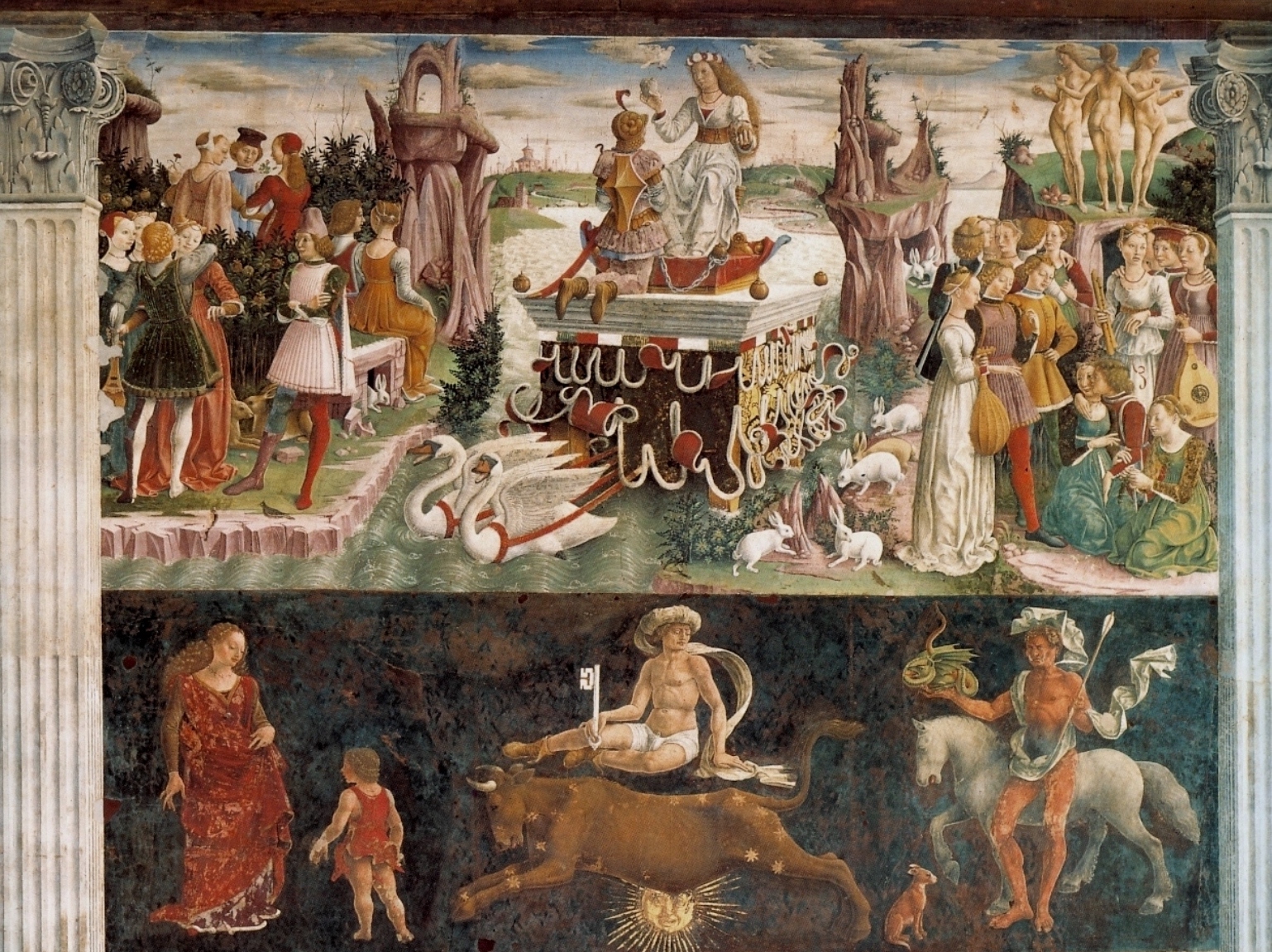

Each of the Signs of the Zodiac, as you will know, is said to be ‘dominant’ for the thirty days during in which it is ‘in conjunction’ with the Sun; and from ‘dominance’, it was easy to arrive at the idea of ‘Triumph’, and to give ‘Triumph’ the sense we discovered at Mantua two lectures ago. So the upper zone of the frescos in Schifanoia always represents the appropriate Olympian deity (in Figure 00b FIXME, Minerva is paired with Aries), riding on a triumphal chariot, drawn by appropriate animals (in this case white unicorns), and accompanied by an appropriate retinue.

Here, we have to the left scholars, soberly dressed, their noses buried in books, and to the right, women weaving at a loom, and embroidering (although I suspect these are meant to be the Three Fates). There is no space here to explain the ‘decans’ who accompany the Signs in the middle section of the wall, nor is there time to do more than remind you of the obvious fact that the whole point of the ‘science’ of Astrology was that the stars and planets were believed to ‘rain down’ influences—influences, which were either ‘benign’ or ‘malignant’, which varied with the different conjunctions of the heavenly bodies, and which did a great deal (though how much was always in dispute) to affect or to determine our temperament, our health and our inclinations. Hence, the lowest of the three bands (cf. fig. 7, Taurus) shows typical human activities on Earth as influenced for good or ill by the heavens.

Specifically, the lowest band shows some of the activities of Duke Borso himself (this is the source of the detail used for his portrait in fig. 5 above). He is represented in exactly the same way as Lodovico Gonzaga was portrayed in those same years at Mantua—in a group portrait with members of his court.

The small oblong area at the top of the middle zone (found in some months but not all) also deals with contemporary human life; and the one in Taurus is absolutely fascinating, since it shows the Palio at Ferrara, in its dual aspect of a horse-race (as at Siena), and what was called a ‘humilation’ race—a race on foot, between vagabonds, prostitutes and Jews, run for the amusement of the nobles and their ladies, seated above.

These attendants give the artist, Francesco del Cossa, a wonderful chance to show fifteenth century Ferrarese art at its most characteristic, and as being everything that Titian’s art is not: naïve, light in tonality, sharp in outline, anxious to record every lacquered curl, and every pleat in the contemporary costumes.

Above this group (in fig. 18), you will see Cossa’s version of the Three Graces who were also associated with Venus: Beauty, Desire, and Pleasure. On the ground, you can see rabbits and hares—famous respectively for their fecundity and for their madness in the mating session. Nor should we forget the Goddess herself, decorously clothed in the costume of a fifteenth-century court beauty, and with Mars kneeling before her, in full armour, but chained, ‘in her thrall’ (cf. detail in fig. 18 below).

For reasons of space and internal economy, I must renounce the pleasure of showing you many more details from other Signs in the room, but I hope to have shown you enough to make you want to go to Ferrara and ‘banish dull care’ for a couple of hours in Palazzo Schifanoia.

*******

As you can read in the genealogical table in fig. 19, Duke Borso died in 1471, and for the second time running, a ruler of Ferrara was succeeded by his brother—a much younger half-brother called Hercules, or Ercole, who ruled as Duke of Ferrara until his death in 1505, and whom you can see in the posthumous portrait by Dosso Dossi in fig. 20.

He was much admired by Machiavelli for the way in which he survived a major war against Venice in 1482–84 (hence the armour); and in the last fifteen years of his regime he was the moving force behind an extremely ambitious programme of building, such that the new city walls would include three times the previous area, and the new streets would be laid out according to the most advanced ‘town planning’ of his day.

Apart from stimulating architecture, he was a notable patron of the Arts—he had Josquin as a court composer for two years—and he had considerable success in ‘placing’ his very well educated, art-loving daughters. Beatrice married the Duke of Milan, who was the patron of Leonardo da Vinci in the 1480s. Isabella (whom you see in fig. 21, a drawing by Leonardo) married the Duke of Mantua, and together they became the last patrons of Andrea Mantegna, as we saw in his Triumph of Caesar.

Lucrezia presided over a brillant, small court until her death in 1519; and perhaps this is the moment to add that the greatest Italian poet of the Renaissance, Ariosto (fig. 24), was in the service of the Este family, and that the first edition of his chivalrous epic, Orlando furioso, was published in 1516, by which year Alfonso had taken on the appearance recorded in fig. 24:

It had become something of a fashion for a prince to have a splendid private room, decorated perhaps with illusionistic marquetry, as at Urbino (fig. 28), or with a set of paintings done by great artists, as was to be in the case of Alfonso’s sister at Mantua, who commissioned solemn and learned allegories of the virtues from artists such as Mantegna and Perugino.

Alfonso was a simpler man than his sister, but he was a man of his age. He wanted the paintings in his private room to celebrate the earthier pleasures of good wine and sex, but he chose to dignify these pleasures by associating them with the classical deities Bacchus and Venus. He obviously insisted that his paintings should be extremely detailed illustrations of passages in classical literature. By 1514 he had already persuaded Giovanni Bellini to illustrate a passage from Ovid; he tried very hard to obtain a Bacchus from Raphael, and a Venus from Fra Bartolomeo, of which fig. 29 is his preliminary drawing:

When they both died before delivering the goods, however, he turned to a thirty-year-old Venetian painter called Vecellio, Tiziano Vecellio, otherwise known as Titian. From him, Alfonso commissioned three paintings which were to be of the same size as the existing Bellini: one illustrating another passage in Ovid, and two attempting to recreate lost classical paintings representing Bacchus and Venus, as described by a Greek rhetorician. To these, he would add a fifth painting by his own court painter, Dosso Dossi.

The five works are now dispersed. But I have so to speak reassembled them here, so that we may view them as a cycle—because Alfonso’s ‘camerino’, as it is called, must have been the most beautiful small room anywhere in Italy at this time, and because the relationship between pictures and narrative texts is one of the most interesting that I have had the pleasure of examining in these lectures.

Before we come to our main item of business, however, I must remind you that the art of painting had evolved almost out of all recognition between 1470 (the date of the Schifanoia frescos) and 1520 (the time when Titian began his oil paintings for the ‘camerino’).

Today, we think of the feeling of upward movement and the extraordinarily complex ‘choreography’ of the Assunta as being somehow generically Italian—as you might say, ‘Post Raphaelite’—but the warmth of colour and the softness of outline (cf. the detail in fig. 32) owe a very great deal to a quieter revolution, which had been taking place more exclusively in Venice, and which we owe to the extraordinary ‘late summer’ of Giovanni Bellini.

Look at the head of St John the Baptist in the altarpiece in fig. 33, which was painted when he was 80 years old, in 1510; or again (in fig. 34), look at the no less extraordinary ‘spring’ of that mysterious genius, Giorgione, who died of the plague in the year 1510, when he could not have been more than 30.

At this point I had intended to try and say in my own words what it is that makes Giorgione’s figures, his landscapes and his skies so startlingly new; why it is that his contemporaries called this painting a ‘poem’, ‘una poesia’; and what were the features that the young Titian took over from him. I soon realised, however, that a proper answer to these questions would totally exceed my brief in a lecture about Titian, so instead I shall limit myself to offering you three more images, to be treated as ‘test-cards’, so to speak, in order to give you time to ‘adjust your sets’ to the signals coming from this new ‘channel’.

The first of these (fig. 35) is from our National Gallery in London. It is very much earlier Giorgione, and is only twelve inches high. Look at the detail in fig. 36 (about two inches square), so that you can register the soft, ‘smoky’ ‘sfumato’ outlines, the shadows, the warmth of the flesh tones, the simplification of the heads, and a certain feeling of inwardness:

In this case, the experts suggest that the goddess was painted by Giorgione, but that the landscape was completed by Titian in about 1510. With the economy of a true professional, Titian used the same hill and the same building in his Noli me tangere (fig. 38; again about 1510, and now in our National Gallery):

It is a splendid anticipation of what we shall find at Ferrara in the varying impressionist treatment of the rocks, the broad-leaved foliage, lit by the rising sun, and the radiant colours of the clouds.

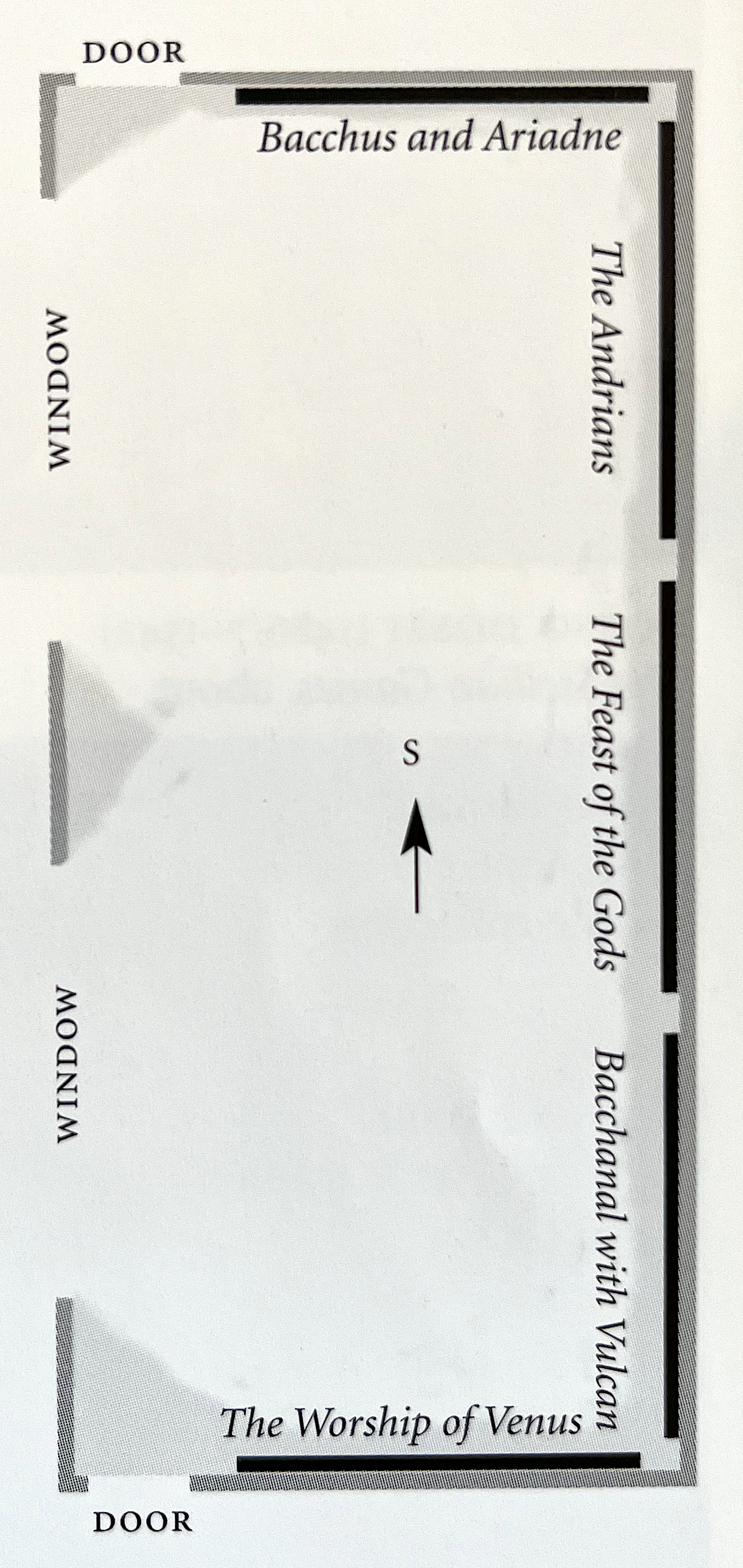

Back now to our ‘advertised programme’; that is, back to Alfonso’s ‘camerino’, the pictures devoted to Bacchus and Venus, and the texts which they illustrate. There have been two superb articles in recent years, which attempt to reconstruct the layout of the main apartments in the castle wing, to discover which works of art were in which rooms, and specifically, to establish the layout of the five paintings which concern us in this lecture. Needless to say, they come to very different conclusions!

Charles Hope opts for one ‘camerino’, while Dana Goodgal finds two, which would presuppose a different lay out. She assumes that the pictures were hung above the doors, as you saw with Carpaccio’s canvases in the School of St George:

PAT: MORE RECENT RECONSTRUCTIONS (LIKE THE ONE I HAVE PUT IN), INCLUDING CHARLES HOPE IN 2003 AGREE NOW WITH TITIAN, BELLINI, DOSSI (LOST), TITIAN

She suggests the arrangement you can see in fig. 40 putting the ‘three best pictures’ side by side on the long wall, in the order, (from right to left), Bellini, Titian, Titian.

Hope has the pictures at the normal height, and in his arrangement (fig. 41), the Bellini is hung at the centre of the long wall, with a Titian on either side, while the third Titian goes round the corner.

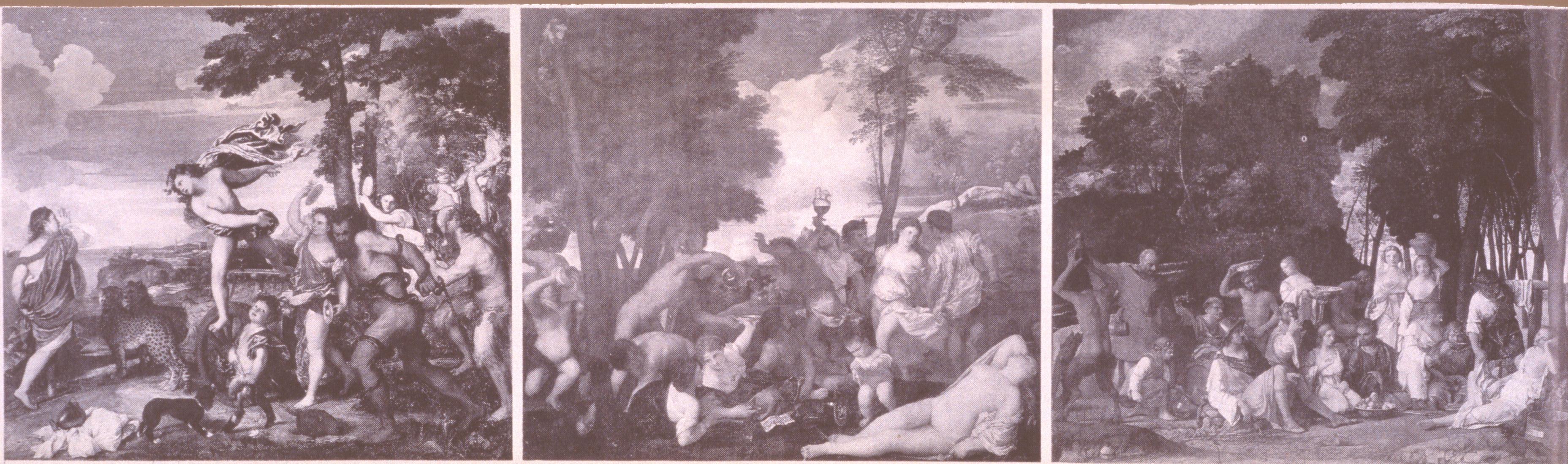

All it is necessary for you to keep in mind, however, is that the room was tiny—the longer wall measuring not more than twenty feet; and that what I am venturing to call the ‘three best pictures’ (fig. 42) were originally intended to be hung in the sequence C B A, whether or not they turned the corner.

Let us begin by looking at the right hand picture in the photomontage (fig. 42). It is usually called the Feast of the Gods, and it has now found its way to Washington. It measures five and a half feet by six. The figures and the foreground were painted by Giovanni Bellini (it is firmly dated to 1514, when the artist would have been eighty four years old). But the trees on the left and the rocky crag were repainted by Titian, some ten years later.

The underlying story comes from Ovid’s unfinished poem on the festivals of the Roman calendar, Fasti, which we can think of as being his pagan Golden Legend; and the episode in question is a kind of ‘Just-so story for adults’, which purports to explain why it is that donkeys are sacrificed to Priapus, the god of procreation or fertility (you will probably know that wooden statues of him, usually shown with an enormous erection, were used by the Romans in their gardens as scarecrows).

It is not a very ‘proper’ story, and Ovid, indeed, asks himself whether he ought to tell it or leave it out. In the event, however, he finds it so pleasing that he tells it twice, with a different heroine each time: once in connection with the Ides of January, and then again in connection with the Ides of June.

It is the time of the biennial feast of Bacchus (if we follow the first version) or of the feast of Cybele (if we follow the second). In our painting we see the infant Bacchus, who is drawing wine, and Cybele, holding a quince taken from the fruit bowl on the ground.

The eternal gods have come together for a glorified picnic, with ‘Pans, lascivious Satyrs, and the Nymphs or goddesses of the countryside’. There are three Satyrs (two of them stripped to the waist), of whom one must be Pan. The Nymphs are placed to the right, while the seated (or reclining) gods in the foreground are clearly the guests of honour, the Olympians.

Ovid, in fact, does not name them, but they are identifiable by their attributes (just like the saints in an altarpiece). In the details (figs. 44, 45) you can pick out from left to right: Mercury (helmeted and holding his caduceus); Jupiter (drinking, with a bedraggled eagle on his shoulder);

Neptune (who is getting fresh with Cybele, his trident lying on the ground); and Apollo (who is drinking from the flat dish and holding in his left hand the neck of a primitive member of the Viol family).

The key figures in the story, however, are old Silenus on the left (standing next to his donkey), and young Priapus on the right.

We are told that Bacchus poured the wine; and Ovid specifies that some of the nymphs had their hair neatly combed, while others had let their hair down. We are also told that the nymphs were all barefoot, and these facts combined to excite (to borrow a phrase from Dr Johnson) the ‘amorous propensities’ of the Satyrs, Silenus and Priapus. What Bellini shows in the main group is the earlier, more decorous phase of the party, although the girls are clearly beginning to display their charms, and, as the wine runs free, their shoulders and bosoms have begun to appear.

Priapus is strongly attracted by a nymph called Lotis (in the first version), or Vesta (in the second version), but she rejects his sighs and his gestures. Night comes on, and the revellers ‘crash out’ on the grass, having been overpowered by the wine.

Lotis falls asleep, under a maple tree, ‘apart from the others’; hence I have separated her, in the black and white detail (fig. 47). Priapus notices her and tiptoes across, holding his breath, until he is standing close by. She is full of sleep (plena soporis) and she does not stir. He lifts the dress that covered her feet (a pedibus tracto velamine), but, just when he is sure he can have his will, the donkey, old Silenus’s mount, utters a raucous and ill-timed bray (intempestivos edidit…sonos…. rauco…ore), with the result that Lotis awakes and escapes, and the gods mock Priapus and the all too evident indicator of his lust. This, ‘O best beloved’, is why Priapus has demanded the sacrifice of donkeys ever since that day.

It is a strange picture, not least in its mixture of tree-trunks by Bellini, on the right, alongside the broad masses of Titian’s foliage and his treatment of the rocky crag, on the left. The grouping of the foreground figures is really rather sophisticated—you can see how they are linked by their movements or their gestures—but it is still totally innocent of Florentine choreography and artifice of the kind we saw in Raphael. The picture is very ‘matter of fact’, too, in its attitude to the Olympians; which contrasts with the extraordinary beauty of its colour.

We do not know if Dosso Dossi’s picture for the right hand wall still exists, because considerable doubts have now been cast on what used to be considered the most likely candidate, the so-called Bacchanal (fig. 48), which is now is our National Gallery:

At four and a half by five and a half feet, it is smaller than the others in both dimensions; it lacks some details mentioned in early descriptions; and it is, on the whole, too close to the Bellini, since you might well interpret this as the middle and the penultimate phases of the fête champêtre we have just been looking at.

Food is still being served, but the males in the party are naked; the girl on the left, next to the hairy satyr, is showing rather more than a shoulder or a knee;

love-making is beginning, and the couples have scattered beyond the little groups in the foreground with Silenus and Pan.

It is likely also that Alfonso’s picture would have been a particularly fine one, because Dossi at his best could be a very suggestive painter (in the fullest sense of the word), as you can see in FIXME Figure 00 in his illustration to the Circe episode in the Odyssey (it might also be an illustration to the derivative Alcina episode in Ariosto’s epic, because Alcina and Circe both turned their lovers into beasts):

Dossi is also very romantic in his moonlight version of the Adoration of the Three Wise Men, which is about the same size (nearly three foot by almost four), and is also in our National Gallery:

Dossi’s contribution must have been something like the NG Bacchanal in its figure style and in the landscape—notice the broad glade leading diagonally to the bluish hills and to the sky, with the sun catching the broad-leaved trees—because these both act as rhymes, or at least assonances, with the first of the canvases by Titian (which for Charles Hope, would have lain at right angles to the Dossi, on its left). It was clearly the same concern to make the canvases match or rhyme that led Titian to repaint the trees in Bellini’s Feast of the Gods.

The conventional or received title of this painting (fig. 50) is the Worship of Venus, but, as we shall see, there is absolutely no doubt that its real title should be Cupids; or, in Latin, Cupidines.

Look first at the sky, the hint of dark blue hills with the campanile, the farm building with its chimney, the broad masses of the trees that occupy about a quarter of the canvas, because these all come from the ‘repertory’ of standard backgrounds that Titian had built up through his contact with Giorgione in the early years of his career (by this point, he would have been in his mid-thirties). But almost everything else in the picture comes from the classical text that Duke Alfonso had asked him to illustrate, or rather, ‘to recreate’. Because this the first of the two ‘recreations’ of lost or imaginary classical paintings that had been described in Greek prose by Philostratos in the early third century AD, in a work called, in Greek, Icons, and, in the Latin translation that Alfonso had borrowed from his sister Isabella, Imagines (that is, Images). This work consists of 64 such ‘descriptions’ or ekphrases, preceded by an introduction in which Philostratos explains that they are intended to help the young ‘to interpret paintings and to appreciate why they are valued’.

They are cast in the form of little talks given to the ten-year-old son of his host while he was staying at a splendid country villa which had many panelled pictures. Hence, the first description of all begins: ‘Have you noticed, my boy, that the painting here is based on Homer?’. And the first words of the sixth description, entitled Erotes, or ‘Cupids’, are: ‘Look, Cupids are gathering apples, and do not be surprised that there are so many of them’.

As I indicated, Titian is following his author very closely indeed, and all the features I am now going to point out derive from Philostratos. ‘Cupids are gathering apples’, which grow ‘red and gold on the ends of the branches’ of trees, which run in ‘straight rows’, with ‘space left free between them to walk in’ and with ‘tender grass fit to be a couch’. The cupids have blue wings; they are not wearing their crowns, as their hair suffices; and they are untrammelled by their gold-studded quivers, which they have hung on the trees (Titian has made the quivers far too big, so that we are able to see them).

They do not need ladders, because they fly to where the apples hang; the baskets they use to gather the apples are encrusted with jewels (Titian gives them prominence, but his are more functional and more ‘vernacular’). ‘Their embroidered mantles lie on the ground, and countless are the colours thereof’. Some of the Cupids are sleeping (I can see at least one in the centre), while others are engaged in wrestling. All the main features in this area, including the grip, the attempt to bend back the fingers, the answering bite on the ear, and the audience pelting the wrestlers with apples in disapproval of these ‘professional fouls’, come from Philostratos.

Then, to quote literally again from the Loeb translation, ‘let not the hare yonder escape us’, ‘the hare which possesses the gift of Aphrodite to an unusual degree’, and which has been hunted, without arrows, and caught by the Cupids as ‘an offering to Aphrodite’.

Again: ‘Do look, please, at Aphrodite [cf. the detail in fig. 51]. But where is she, and in what part of the orchard yonder? Do you see the overarching rock? With the spring?…Be sure she is there…where the nymphs have established a shrine to her, because she has made them mothers of Cupids. That silver mirror is not there without a purpose.…And the Cupids bring first fruits of the apples and pray that their orchard may prosper’.

I have left to the end, though, the most important paragraph of all which relates to the special group of Cupids in the foreground (these can be seen in the pair of black-and-white details in fig. 52), which just overlap, though alas at a different scale:

I shall quote once again, because Loeb English has its charms: ‘What is the meaning of these others? For here are four of them, the most beautiful of all, withdrawn from the rest. Two of them are throwing an apple back and forth; the second pair are engaged in archery, each shooting at his companion. Nor is there any trace of hostility in their faces; rather, they offer their breasts to each other, in order that the missiles may pierce them there. It is a beautiful riddle. Come, let us see perchance if I can guess the painter’s meaning’—which turns out to be that the first pair are beginning to fall in love, the kissing of the apple before throwing being mentioned in the text. Meanwhile, the pair of archers are ‘shooting arrows that they may not cease from desire’.

Now, I am well aware that Protestant taste ‘stumbles’ over Madonnas, and positively ‘sticks’ at Cupids or putti; and I know also that the appreciation of Titian’s painting only begins with the recognition that he was attempting to recreate all those details described in the classical text.

But there are cupids and cupids, as I remind you with a detail (fig. 53) from the Palazzo Schifanoia. It is enough to look at the closely-packed figures of Francesco del Cossa to recognise by contrast the wealth of invention in Titian, his extraordinary power to suggest human flesh, his insight into the sexuality of children—all the qualities that ought to make you give this picture an extra five minutes attention next time you are in Madrid, because that is where you will have to go if you want to see the original.

From a shrine of Venus, in a tee-total orchard, we pass in imagination to the other side of the Bellini to the last two Titians, which are closely connected thematically, and deal with a river of wine, Dionysiac revels, and the love of Bacchus for Ariadne.

This is the first of them—it is the same size as the Cupids and it is also in Madrid. While thinking about its relationship to Bellini’s Feast of the Gods, notice how the paintings are linked by the colour and the scale of the trees (they occupy about a quarter of the painted surface here), although clearly this particular rhyme did not exist before Titian repainted the Bellini.

The argument is once again taken from Philostratos’s Imagines, mostly from the twenty fifth chapter, entitled Andrians (or Men of the Island of Andros). But there are two very important additions from Chapter 15 which establish a link with the previous painting; and I think we ought to register all the features that Titian derives from his written source.

Chapter 25 begins like this: ‘The subject of this painting is the River of Wine on the island of Andros, and the Andrians, who have got tipsy by drinking the river. For thanks to Dionysus’, who, of course, is the Greek counterpart of Bacchus, ‘the earth of Andros is so steeped in wine that it bursts forth as a great river—not “great” in respect of volume, but in the transcendent quality of the wine. It is superior to the River Nile, since this river makes men rich, influential, handsome, and seven feet tall—at least in their imaginations—and it is never muddied by the feet of cattle…but is drunk unpolluted, flowing for men alone’.

The sprawling old man (cf. the detail in fig. 55) may, then, be interpreted as the source of the miraculous river, because his position echoes that of statues of classical river gods, and perhaps it is his weight which causes the saturated earth to ooze and flow with wine.

Philostratos tells us that the Andrians draw their wine directly from the stream; and Titian shows them scooping up, pouring out, pouring down, carrying away, and balancing decanters on their noses, in a wonderfully choreographed interaction of bodies (cf. the detail in fig. 56), which are growing like shoots from the foot of the tree.

Philostratos also specifies that women and children participate (although he does not say that the children lift their smocks for a wee); but that some are dancing, while others are reclining, and that the men are singing the praises of the river. There is not much that Titian can do about the singing, although he does give each of the foreground girls a recorder (and you remember the symbolism) and a sheet of music to play (fig. 57). This can easily be read as a ‘catch’ or ‘glee’; that is, a round, probably composed by the contemporary composer Willaert, setting a very brief text in praise of drinking.

Roughly translated, it means: ‘To drink, and not to call for more, / is not to know what drinking’s for’; and the Renaissance French runs: ‘Qui boit, et ne reboit, / il ne sait que boire soit’.

On the other hand, what Titian can do is to evoke the movement and spirit of the dance quite superbly. We know that the couple are circling round each other (fig. 58), their eyes meeting, their shoulders lowered, pivoting round their clasped hands, the thighs raised in the identical way, suggesting that they are moving to the rhythm of the music, and moving with sufficient speed to lift his doublet and to set her skirt swirling. Nevertheless, despite the splendid ‘choreography’ of moving bodies to the left and to the right, I suspect many people may think that the reclining figures are the most memorable of all—the figures that look back to Giorgione, rather than to Raphael.

The two recorder players (fig. 59) are leaning on their elbows; the first of them in full face, reaching back to have her flat bowl refilled, and with violets tucked into her corsage (from which the not improbable suggestion that she is a portrait of Titian’s mistress Violante: indeed, the violets carry Titian’s signature). Above all, we remember the girl overpowered by sleep (fig. 60: a link to the story of Lotis), with her head thrown back, and her loose hair spreading over the pitcher.

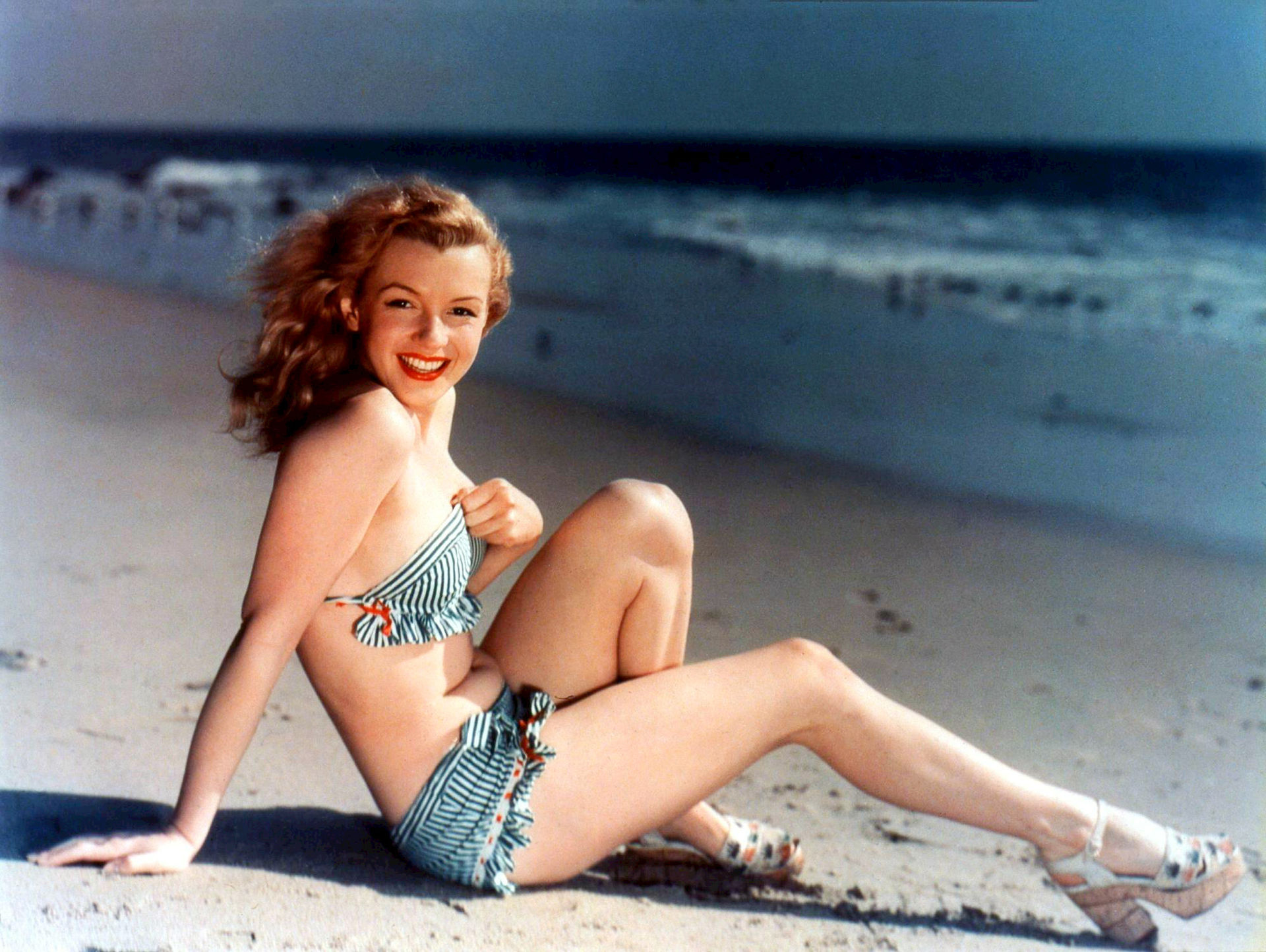

Even Titian never painted young, soft, and desirable female flesh with quite this lyrical abandon again; and while the art historians remind us of pictorial sources in the ancient world, we perhaps might take this as anticipating a modern myth, seeing the qualities that a local photographer found in a girl called Norma Jean, whom Hollywood would turn into Marilyn Monroe (fig. 61).

I now must turn to those extra details in Philostratos which seem to link this picture with the final one in the cycle. At the close of Chapter 25, the author directs our attention to the mouth of the River of Wine, and he says: ‘Dionysos also sails to the revels of Andros; his ship now moored in the harbour’. And in Chapter 15, headed ‘Ariadne’, he had said: ‘I do not need to tell you’—he is talking to that ten year old boy—‘that Theseus treated Ariadne unjustly, when he abandoned her on the island of Naxos…and I do not need to point out Theseus on the ship and Dionysus on the land…nor to call attention to the woman on the rocks lying in gentle slumber…Look at Ariadne, or rather look at her sleep, her bosom bare to the waist, her neck bent back, and her delicate breast and all her right side visible, but her left hand resting on her mantle. How fair a sight Dionysus! (And how sweet her breath!)’.

In short, it is easy to imagine a ‘soft dissolve’; to let the island become Naxos, and to think of the girl as being Ariadne, exhausted by grief rather than wine, and soon to be consoled by Bacchus. For this, precisely, is the theme of the last painting, which—as we saw in figs. 41, 42–was probably intended to be hung to the left of the Andrians, either at right angles to it, or, in Dana Goodgal’s reconstruction, alongside.

It will not cost you a sizeable air fare to Madrid or to Washington if you want to go and see it, but simply the price of a Travelcard to the National Gallery in London. In this, the most famous painting of the five, Philostratos is first joined and then displaced by two Latin poets, namely Ovid again (the Art of Love) with a small injection from Catullus. The rhetorician’s descriptions of timeless or repeated scenes—like the apple orchard or the river of wine—give way to scenes from a single story which are combined within the one frame, just as we saw in the Bellini, because the picture represents the arrival on Naxos of Bacchus and his followers, and his declaration of love to the abandoned Ariadne, including his promise to give her immortality as a constellation in the sky.

I shall give you the ‘bones’ of the story as it is told in Titian’s main source, which is Book 1 of the Art of Love; and I shall use, not the Loeb, but the spirited new verse translation by Peter Green, which you can find in the Penguin Classics:

Ecce, suum vatem Liber vocat; hic quoque amantes

Adiuvat, et flammae, qua calet ipse, favet.

Gnosis in ignotis amens errabat harenis,

Qua brevis aequoreis Dia feritur aquis.

Utque erat e somno tunica velata reccinta,

Nuda pedem, croceas inreligata comas,

Thesea crudelem surdas clamabat ad undas,

Indigno tenereas imbre rigante genas.

Clamabat, flebatque simul, sed utrumque decebat;

Non facta est lacrimis turpior illa suis.

Iamque iterum tundens mollissima pectora palmis

“Perfidus ille abiit; quid mihi fiet?” ait.

“Quid mihi fiet?” ait: sonuerunt cymbala toto

Littore, et adtonita tympana pulsa manu.

Excidit illa metu, rupitque novissima verba;

Nullus in exanimi corpore sanguis erat.

Ecce Mimallonides sparsis in terga capillis:

Ecce leves satyri, praevia turba dei:

Ebrius, ecce, senex pando Silenus asello

Vix sedet, et pressas continent ante iubas.

Dum sequitur Bacchas, Bacchae fugiuntque petuntque

Quadrupedem ferula dum malus urget eques,

In caput aurito cecidit delapsus asello:

Clamarunt satyri “surge age, surge, pater.”

Iam deus in curru, quem summum texerat uvis,

Tigribus adiunctis aurea lora dabat:

Et color et Theseus et vox abiere puellae:

Terque fugam petiit, terque retenta metu est.

Horruit, ut steriles agitat quas ventus aristas,

Ut levis in madida canna palude tremit.

Cui deus “en, adsum tibi cura fidelior” inquit:

“Pone metum: Bacchi, Gnosias, uxor eris.

Munus habe caelum: caelo spectabere sidus;

Saepe reget dubiam Cressa Corona ratem.”

Dixit, et e curru, ne tigres illa timeret,

Desilit; inposito cessit harena pede:

Implicitamque sinu (neque enim pugnare valebat)

Abstulit; in facili est Omnia posse deo.

Ovid, Ars amatoria I, 525–562Bacchus too helps lovers,

as Ariadne discovered, ranging the unfamiliar

sea-strand of Naxos, crazed

out of her mind, fresh-roused from sleep, in an ungirt

robe, blonde hair streaming loose, bare-foot,

calling “Cruel Theseus!” to the deaf waves.

Then, presto, the whole shore echoed

with frenzied drumming, the clash

of cymbals.

She broke off, speechless, fainted,

as wild-tressed Bacchanals, wanton

Satyrs, the god’s forerunners, appeared,

with drunken old Silenus, scarce fit to ride his sway-backed

ass, hands clutching its mane

as he chased the Maenads.

Then came the god, his chariot grape-clustered,

paired tigers padding on as he shook

the golden reins.

Thrice she tried to run, thrice stood frozen with fear.

“I am here

for you,” the god told her. “My love will prove more faithful.

No need for fear. You shall be

wife to Bacchus, take the sky as your dowry, be seen there

as a star, the Cretan Crown, a familiar guide

to wandering vessels.”

Down he sprang from his chariot,

lest the girl take fright at the tigers; set his foot

on the shore, then gathered her up in his arms—no resistance—

and bore her away.

No trouble for gods to do

whatever they please. Loud cheers, a riotous wedding. Bacchus

and his bride were soon bedded down.

So when the blessings of Bacchus are sent out before you

at dinner, with a lady to share your couch,

then pray the Lord of Darkness and Nocturnal Orgies

to stop the wine going to your head!

To these spirited words, we must mentally add details from Catullus (in a poem where he pretends to be describing a tapestry of the same event), who speaks of the ‘departing vessel’ and specifies that some of the Bacchantes were waving the thyrsus (a wand tipped with vine leaves), some were bound with twisting snakes, some were clashing timbrels, some were brandishing the limbs of a dismembered steer.

We must recognise, then, another huge, specific debt to the classical texts specified by Alfonso; and we may be sure that Titian did some careful homework on surviving Roman bass-reliefs, like that shown in fig. 65, in order to see what a thyrsus and a timbrel might look like. But what matters most of all is the transformation of all these elements into a High Renaissance painting, with that sense of movement, extremely sophisticated ‘choreography’, and Venetian colour that would have been inconceivable before 1520.

By way of a conclusion, let us roam over the surface for a while, noting, for example, how, in the original layout, the trees would have met in the corner with those in the Andrians, and how space opens up on the opposite diagonal to that of its companion picture, where the sky (intensely blue after a highly controversial cleaning) is a Venetian sky, and the hills, the buildings and the campanile are those of the Veneto.

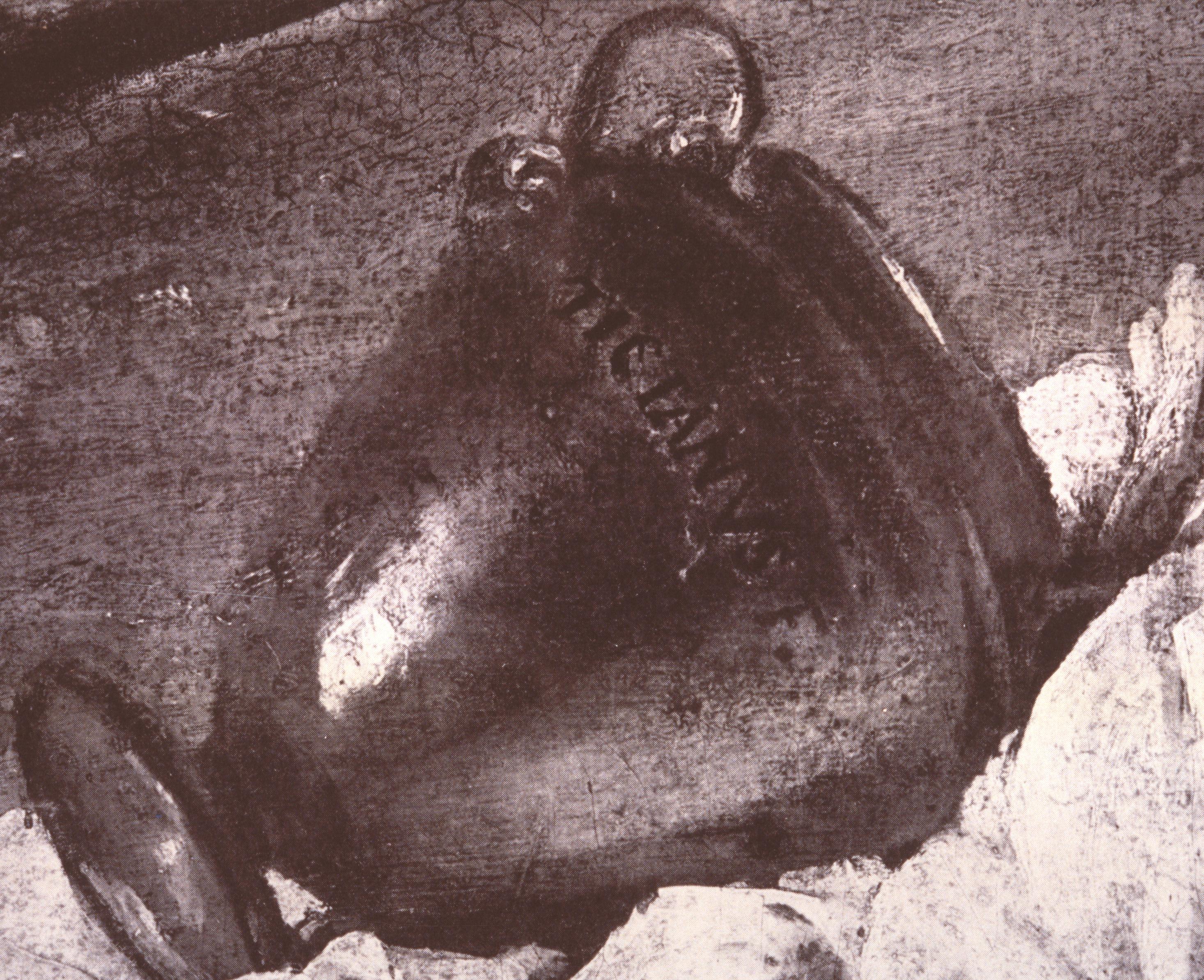

Fig. 055: Detail from Titian’s Bacchus and Ariadne.

The urn (fig. 67) is a wonderful still-life, glistening, even in a black-and-white photograph; and notice how Titian’s signature is apparently cast and glazed with the pot. There are some superb flower studies in the foreground, and the animals are splendidly observed (fig. 68)—from the ‘vernacular’ mongrel, barking at the chariot, to the pair of exotic cheetahs from the Ferrara zoo, who are doing duty for Ovid’s tigers, and exchanging a calm look, relaxed, as only two great cats know how.

Finally, let us focus on the two protagonists, the princess and the god. Ariadne is extraordinary in the combination of what became a favourite pose among the Mannerists (her movements suggesting an upwards ‘spiral’) and her generous, ‘Junoesque’ proportions, which are most un-Manneristic; just look at the massive left arm, clutching the robe around her hips, and the colossal right hand, raised in fear or alarm.

Last not least, we have the amazing irruption of Bacchus, leaping from his chariot, as Ovid had described him, twisting in flight, left arm swept back, right arm swinging round, the cloak blown back and up to suggest the movement forward and down.

Energy and movement were to be the chief hallmarks of the artist who will be the subject of my next lecture: Tintoretto. Indeed, his art make Bacchus and Ariadne seem almost as calm as a ‘sacra conversazione’, as you will see when we visit another of the Venetian Schools, the Scuola Grande of San Rocco, to have a good look at his most original and famous cycle—the canvases that he did for the Sala Grande of the School.