This lecture brings us back to Venice, to look at perhaps the most famous of all the cycles of paintings done for one of the Venetian ‘Schools’, those friendly societies or Confraternities, whose membership and activities we got to know a little when we were looking at the canvasses by Gentile Bellini and Carpaccio (fig. 2) two lectures ago.

The ‘School’ we are concerned with today was founded as late as 1478, and it was dedicated in particular to the relief of victims of the Plague. Epidemics of the Bubonic Plague had affected Europe both before and after the notorious Black Death in the middle of the fourteenth century; and some of these later visitations were absolutely devastating. As a seaport, with 100,000 inhabitants, trading with the East, Venice was particularly vulnerable: in 1575–7, for instance, an epidemic was to kill nearly one third of the entire population, that is, some 30,000 people.

Given this objective, the new School was dedicated, almost inevitably, to the recent French saint, Roche, known in Italian as Rocco, (whom you see in fig. 3 alongside Saint Sebastian), who had contracted the Plague while on a pilgrimage, and who was thought to help and heal victims of the pestilence. He had died in 1327 (a few years after Dante), and was buried in Montpellier.

From there, his cult spread through the Mediterranean cities, and (as you can see in the little panel from the Fitzwilliam above) he is usually shown dressed as a pilgrim, and he usually points to a large black boil on his thigh, which was where the Plague often first appeared.

This new ‘School’, dedicated to Rocco, was founded in 1478, but its enormous success and prestige can be dated to the year 1485, when some Venetians went to Montpellier and simply stole the body of the saint, bringing it back to Venice amid great civic ceremonies and rejoicing. Four years later, the confraternity was already recognised as a Major school, ‘Scuola Grande’. They were given a site just south of the church and major school of St John, where the canvasses by Carpaccio and the Gentile Bellini used to hang, and very close to the Dominican church of S. Maria de’ Frari (cf. fig. 4).

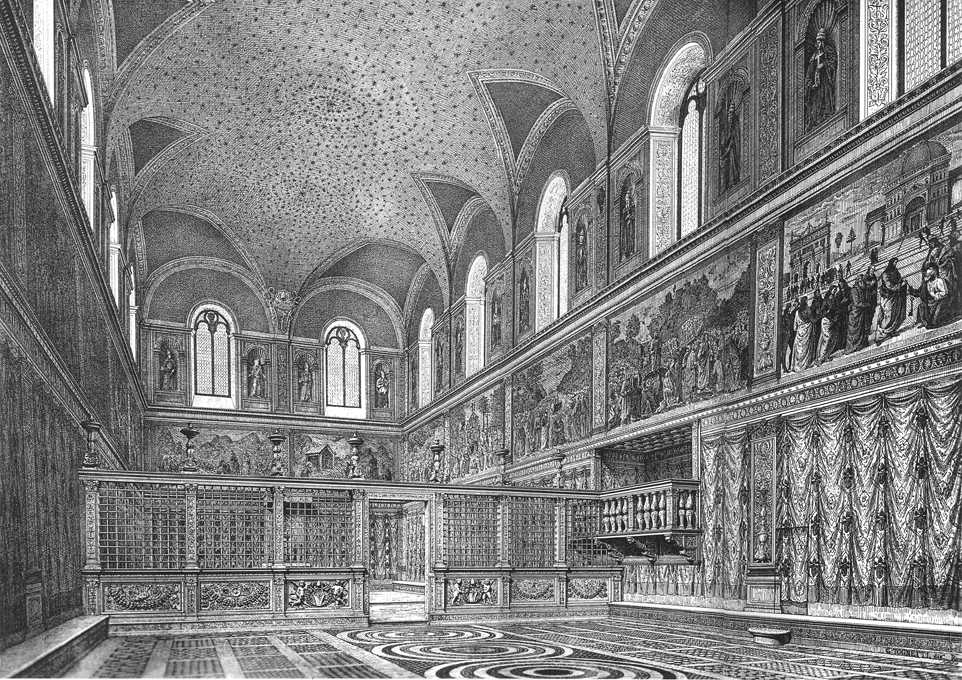

Their headquarters was a very grand building indeed, as we can see even better in Canaletto’s painting and the nineteenth-century engraving (fig. 7) with its accompanying plan. The ground-floor room measures almost 50 yards by nearly 20, and there is a superb staircase leading up to the Sala Grande (or Sala Superiore) on the first floor, which is of the same size, and to the smaller committee room or ‘Sala dell’albergo’, opening out in the area over the entrance.

He was the son of a dyer, in Italian, ‘tintore’, and therefore known as ‘little dyer’, or ‘dye-ling’—Tintoretto. He was a local boy made good, and, since no one is a prophet in his own country, he had to overcome some initial resistance from School members by a certain amount of sharp practice. But he executed the canvasses for the ceiling and walls of the ‘Sala dell’albergo’ in the mid-1560s, when he was about forty-five, and then huge areas of canvas for the ceiling and walls of the Sala Grande between 1576 and 1581, when he would have been around sixty, and, finally, ten canvasses for the ground-floor between 1583 and 1587—by which time he was nearly seventy, and must have resembled the not unaffectionate caricature in fig. 9:

At the half-way point—1577—he won for himself a contract unique in the history of Venetian art, whereby he received an annual pension for life of 100 ducats on condition that he would finish all the needed canvasses at the rate of three per year. San Rocco was Tintoretto’s own School, to which he was deeply and passionately committed; and in those three sets of canvasses he tackled virtually all the main subjects in Christian art, rethinking them totally, moving his compositions further and further away from realism, geometrical perspective, the ‘archaeological’ reconstruction of a glorious past, and the use of a Venetian warmth of colour—all the qualities we have been admiring in the last three lectures—towards a visionary, hallucinatory, ‘phantasmagoric’ style that would record not the natural, but the presence or the intrusion of the supernatural.

We have no fewer than twenty large canvasses to examine in this lecture—all from the second cycle, that for the Sala Grande—so there is no time for a leisurely look at the general evolution of Italian painting in the fifty years between 1575, when he began work, and 1525, when Titian delivered the last painting for the ‘Camerino’ of Duke Alfonso (cf. fig. 12).

Yet, however personal and idiosyncratic Tintoretto’s style was to become, the elements of that style are shared with a whole generation; and so I feel the need to spend a few words picking out the ‘trajectory’ that connects figs. 10, 12 by looking at a couple of major influences and at three or four of Tintoretto’s earlier paintings.

Born in 1519, when Titian was already at work for Ferrara, Tintoretto trained for a short time in Titian’s workshop. But his generation was to be greatly influenced by important new trends in central Italian art in the 1520s and 1530s—by what was then called ‘the style’, ‘la maniera’, and is now called ‘Mannerism’. This was a movement which had many and very different adherents, but they were all in some way deeply indebted to Michelangelo, and especially to the frescos on the Sistine ceiling:

The debt consists in the sharp, acid colours, in the unclassical, elongated proportions of the figures who are frequently posed with violent torsions of the body—such that they often seem to be, as Lewis Carroll said, ‘reeling, writhing, and fainting in coils’—and also in a preference for strenuous, difficult, restless and disturbing compositions. These features can be seen, in a relatively restrained form, in the family group in fig. 13 (top left) (one of the Ancestors of Christ in the lunettes, c. 1510) and, more dramatically, in fig. 13 (top right), which shows one of the corner pendentives near the altar wall in the Sistine Chapel. (It is relevant to know that this shows the Israelites being tormented by a plague of snakes until such time as they were delivered when Moses raised a ‘brazen serpent’ on a pole—usually, in Christian art, a T-shaped cross, with reference to the Crucifixion.) The pendentive dates from c. 1512; and it lies alongside the lunettes of the Last Judgement, painted much later, in 1536, where the angels carrying the cross are a perfect example of Michelangelo’s art at its most ‘mannerist’ (fig. 13, bottom).

The frescos in the Sistine Chapel, then, are the single most important source of the new trends; and you will have heard that Tintoretto dreamed of combining Titian’s colour with Michelangelo’s power of drawing—his ‘disegno’. As a single example of a ‘mediator’ between Michelangelo and Tintoretto, we may glance at the amazing Adoration of the Magi (fig. 14) dating from 1545 by Andrea Schiavone, from whom Tintoretto is known to have learnt a good deal (and who competed against him for the first San Rocco contract):

You can see that, taking his cue from the spirals on the column, Schiavone twists virtually every one of his figures into fantastic shapes—even the infant Jesus recoiling from the oldest king. Tintoretto’s early paintings are nothing like as restless as this, as you can readily confirm if you go to the Fitzwilliam Museum to see his Adoration of the Shepherds (fig. 14b), dated 1542–44, which measures about five and a half feet by nine:

FIXME: TOM: we must find this and call it fig. 14b for now ‘Tintoretto Fitzwilliam Shepherds to Fitz talk and file 2003’]

But if you look closely at the twist of the baby in the maid’s arms, at the ‘ardour’ of the shepherd in olive-green, the almost balletic gesture of Mary, and the supernatural light emanating from the Christ-child, you will recognise the roots of many of the canvasses in the School of San Rocco.

A new intensity in Tintoretto’s art is to be found in the huge canvas, nearly fourteen feet high by eighteen wide (fig. 15), which he painted in 1548, when he was 29, for the major school of St Mark. It illustrates the tale, from the Golden Legend, of how the saint (flying in like Superman, or, rather, like Michelangelo’s Jehovah) rescued a slave who was being beaten to death by the two torturers—one of whom is seen in full swing—by smashing their mallets to smithereens:

There is still beautiful architectural perspective here, and bright Venetian colour, and a concern for symmetry in the grouping of the figures. But this is a painting of mid-century, as you can tell from the poses of the astonished onlookers, who spring up with outspread arms, or recoil while remaining seated, or twist with a baby in arm, or bend forward, swinging the left arm across the body.

Fourteen years later, when Tintoretto came back to the School of St Mark in the early 1560s, his two large canvasses (shown side by side in fig. 16) are incredibly more advanced and quite staggeringly theatrical: not only in the figures, but in the dramatic use of the colonnades in steep perspective, and in the dark shadows contrasting with celestial radiance or flashes of lightning (the Venetians are shown stealing the body of their patron saint, just as they stole the body of St Roche).

These two paintings were done by 1566, by which time Tintoretto had begun his work for the Scuola di San Rocco, in the smaller room, the Sala dell’albergo (fig. 17).

The composition is derived from a wood-cut by Dürer; it is seventeen feet high by twelve and a half feet across; it was done in 1567; and it shows Christ before Pilate. The vanishing point for the perspective is well outside the painting, to the left, with the result that the classical architecture of the Roman governor’s palace opens up a composition on the diagonal, with the heads of a crowd, baying for blood, seen in the background.

Pilate twists as he washes his hands, the turbaned figure starts up, the young man recoils, and the old shorthand writer (whom I have picked out in fig. 19) almost steals the show, as he crouches, with his right hand raised to record the verdict. But it is Jesus we remember above all, stock-still, elongated and pencil-thin, almost like a candle, caught by the light flooding in between the columns—the mood of the whole painting depending greatly on the contrast between deep shadow and bright patches of sky or of light reflected from different surfaces: from marble, a turban, a robe, or a human face.

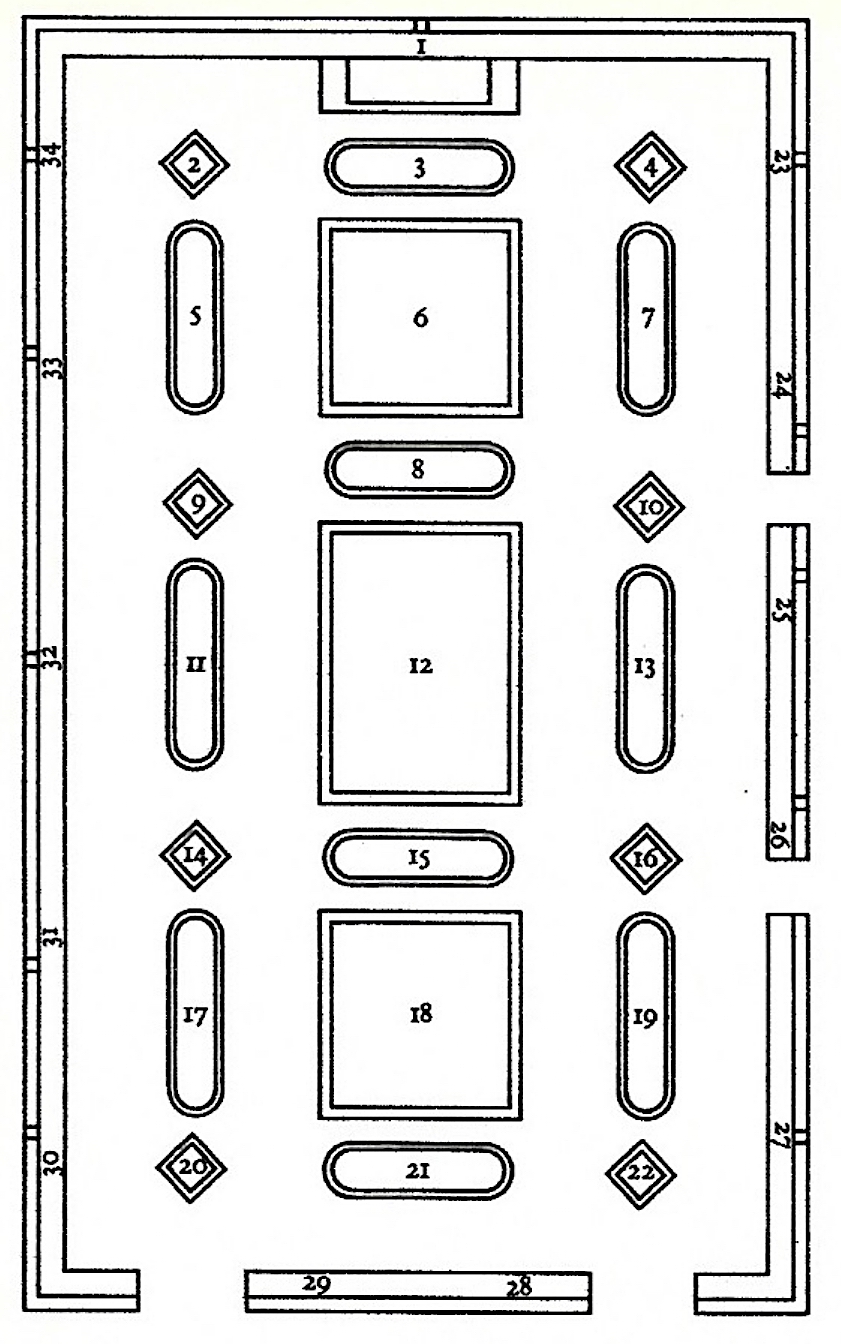

This brief anthology should have given you some idea, then, of the artist who will reappear in the School of San Rocco in 1575, when the guardians took the decision to decorate the ceiling of the Sala Grande (fig. 20), a decision which would be extended to the walls in 1577 in the special contract I mentioned earlier.

There have been—and still are—disagreements about the nature of the underlying conceptual plan and the degree to which it is coherent, or the degree to which the plan was intended from the outset. But there should not really be any difficulty in grasping the guiding principle, which is that scenes from the New Testament are ‘paired’ with one or more episodes from the Old Testament—episodes which had been interpreted for many centuries as ‘prefigurations’ or ‘types’ of a later event in the Life and Passion of the Saviour.

The Sistine Chapel (fig. 22) was characteristic of hundreds of churches, in that Old Testament stories of Moses were placed upon the left wall as you face the altar (the south, the Epistle side), while the corresponding New Testament story was placed opposite on the right wall (the north, the Gospel side). Other arrangements were possible—in stained-glass windows, for example—and the only innovation in the Sala Grande is that the New Testament stories are on the walls, while the Old Testament stories are placed on the ceiling in the vicinity of the episode which they were thought to ‘foreshadow’ or ‘typify’.

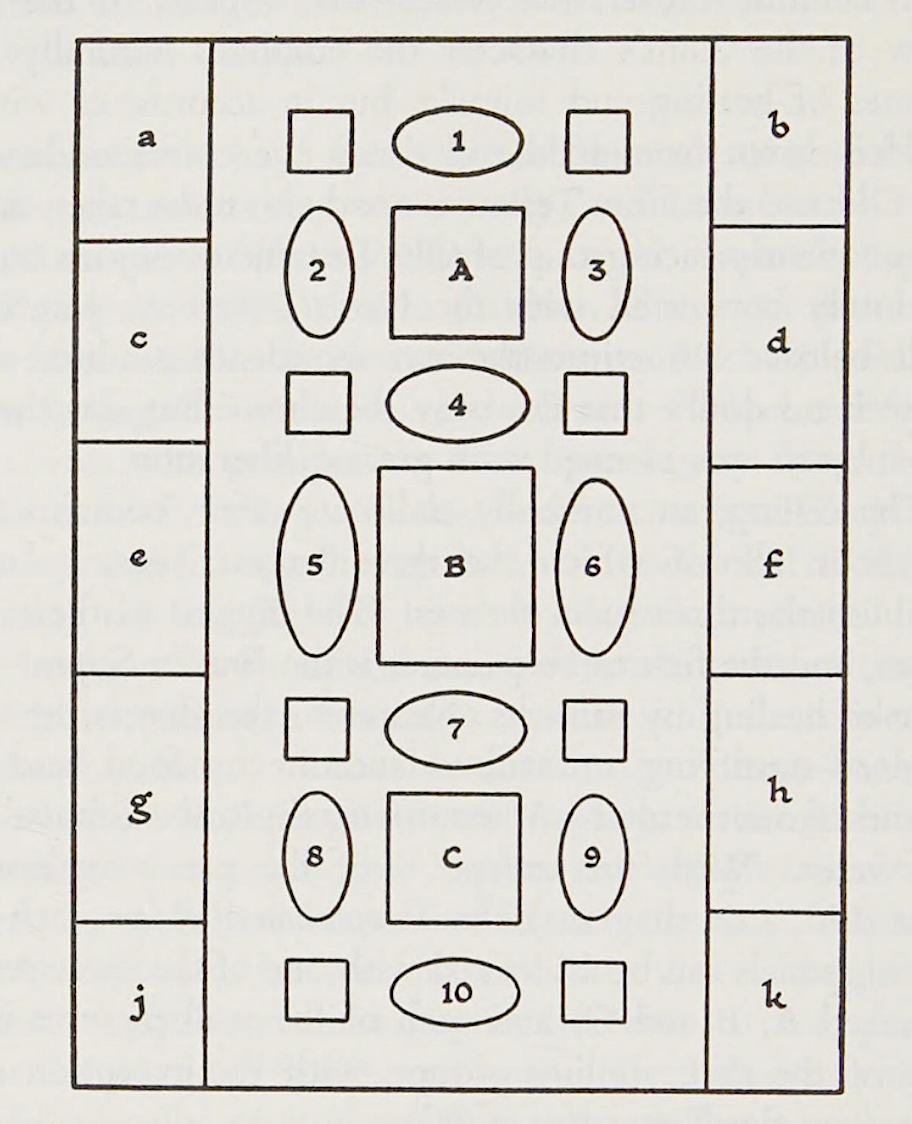

So far, so good—but if you begin your visit with the Nativity—little (b) in the scheme of the layout in fig. 23—you will come first to the Baptism (d), exactly as in the Sistine Chapel, but you will then find the Resurrection, followed by the Agony in the Garden, coming before the Last Supper (k).

Hence it is obvious that the sequence of the narrative in the gospels has been abandoned in favour of some other criterion; and this proves to be a three-fold division, reflecting or determining the subjects of the three main canvasses in the centre of the ceiling, which are, in order:

- Moses striking water from the Rock,

- Moses erecting the Brazen Serpent,

- Moses supervising the collection of the Celestial Manna.

For Eric Newton, writing in 1952—and for other scholars, before and since—the three-fold division reflects the three activities of the School of San Rocco as a charitable organisation. Hence, after an ‘Introduction’ (1a, b), we have ‘Succour by Water’ on the walls and ceilings; ‘Succour by Divine Intervention’ across the central band; and ‘Succour by Food’ on the walls and the ceilings next to the altar.

However, Guido Perocco, writing in 1979 and summarising work done in the 60s and 70s, believes that the paintings should be read—as would be normal—retreating from the altar, and in accordance with the sequence of Holy Week. ‘Succour by bread’ refers to the consecrated host—the body of Christ, Corpus Christi, the ‘consubstantial’ bread—and would be the subject appropriate to Maundy Thursday, the day of the Last Supper. The central themes are those associated with Good Friday and Easter Day: not simply ‘divine intervention’, but the Crucifixion, seen as a triumph, seen as followed by Christ’s Resurrection and Ascension—in short, the Crucifixion interpreted not as humiliation and defeat but as the means of our resurrection and of union with God the Father, which are made possible by the sacrifice of the Son. Thus, the canvasses in the third group are not concerned with water to wash off the dirt or to quench a bodily thirst, but water as the symbol of Grace, flowing from the wound in Christ’s side to cleanse the taint of Original Sin and the stain of all the sins we commit after baptism, or water as the means to quench the very special thirst of the Woman of Samaria.

The only trouble with his strictly sequential interpretation—rising from bottom to top, as it were—is that the four New Testament narratives in the highest section are all taken from the earliest part of the Gospel narratives. So I am going to suggest that the middle section (the canvasses you begin to see as you climb the stairs, both on the ceiling above, and on the opposite wall) is ‘central’ in every sense of the word, since nothing else makes sense, or has any importance for the congregation, unless Christ was crucified and unless he rose from the dead. The spiritual bread and the spiritual water are complementary to each other—like solid and liquid, or food and drink—or may be understood as two branches growing out from the same trunk. Hence, there is no ideal order of presentation; and I am following a mere inclination in this lecture by choosing to examine the ‘branches’ before the ‘trunk’, that is, by beginning with Bread, continuing with Water, and finishing with Atonement.

If we cross over to the left hand wall, we may look at the canvas nearest the altar (fig. 27) with its lower edged placed about a foot above our heads and stretching fully seventeen and a half feet high. It is one of the most memorable images in the room, The Last Supper, painted when Tintoretto was about sixty years old.

The horizon is set very high, so that you hardly notice the ceiling, and the vanishing point is very close to the left side, so that the one visible wall and the tiles on the floor open up space along a diagonal, just as happened in the Christ before Pilate of fifteen years earlier (see fig. 18). The pictorial light sweeps in from the right again (from the unseen window beyond the fireplace) and also from the direction of the real light in the window on the altar wall, so that it catches the maid on the right of the steps in the foreground (she is almost in our space), next to the dog which directs attention upwards and inwards, these steps being the lowest of the three ‘levels’ in the stage ‘set’.

Despite the pilasters, the interior of the inn is as contemporary and local as Pilate’s palace had been classical: focus on the unplastered brick, the metal hood over the fireplace, the plain workaday tiles, and servants reaching up for plates above the sideboard at the back of the room.

But, of course, we do not really register these details at first. Our eye goes to the figures at the table (it too set on the diagonal), and to the human figures diminishing in size with unnatural ‘speed’—from the giant, kneeling at this end of the table, gesticulating and twisting to set up a wonderful pattern of folds, to the balding disciple on the bench, who is letting his arm drop; or from the figure in the deep shadow, on the other side, to the standing man. Or again, starting from the near side of the table, we can follow the gaze of the apostle in white to the minute figure of Christ at the apex of the cone of figures (cf. detail in fig. 29), near the vanishing point of the perspective, his face emitting celestial light, as he says to Simon Peter: “Take, eat, this is my body”.

Immediately opposite, on the right hand wall (fig. 30), just six inches less in each dimension, you find a miracle that ‘pre-figures’ the Last Supper within the Gospel narrative itself (rather than in the Old Testament): the Feeding of the Multitude with two fish and five barley loaves, as told in the Gospel of St John, Chapter 6. The composition does not yield a particularly memorable image, but notice that it uses a favourite form, that is, a ‘split-level’ construction involving a diagonal slope.

Thus, the hill provides a dark background for the six lower figures, who are very close to us and very ‘mannered’; sprawling in exhaustion and hunger, remonstrating with outstretched fingers, reaching up for the bread, or handing it down to a companion in need. And the same hill provides a ‘platform’ for the boy with a basket, who is welcomed by Andrew (who discovered him), and is then sent to distribute his bread and fish by Jesus with a balancing sweep of the arm: these figures being silhouetted, like the seated women and children and the skeletal trees (cf. detail in fig. 31), against the dramatic yellows, reds and greys of the sky. The whole picture has an extraordinary tonality.

The time has come to mentally tip your heads back to study the Old Testament ‘prefigurations’ of these scenes on the ceiling above. The relative positions of the canvasses are shown in fig. 21, and the pattern is really quite simple: a rectangle, surrounded by four ovals, with a lozenge at each corner.

I will simplify still further by ignoring the lozenges (two [FIXME: ?] of which are shown in fig. 32), on the grounds that they were almost completely repainted during an eighteenth-century restoration. So we may begin with the first of the three scenes involving Moses, the one in the rectangle, which has maddeningly been trimmed by the slide-maker, and measures in reality about seventeen feet by sixteen.

It is perhaps the least successful, artistically, of the three ceiling rectangles; and you must use your imagination sympathetically to enter into its mood and meaning, remembering all the time that the painting is intended to be seen above your head, with the ceiling of the Sala apparently opening up to reveal the ‘sky’ and ‘heaven’ (Italian uses the same word for both: ‘cielo’). You are standing, then, at the bottom of a mountain in the wilderness between Sinai and Ephraim, looking up the slope to see the Israelites who have escaped from bondage in Egypt with their flocks. Your eye must go up and up, until you see (to quote Exodus, Chapter 17) ‘a glory of the Lord appear in a cloud’.

As so often, the picture represents several moments in the Bible narrative simultaneously; but it will be enough if you first follow the upward thrust of Moses’ arm (apologies that he has been split in half!) as he promises that the Lord will ‘rain bread from heaven’, and then visualise the fulfilment of the promise as the flake-like manna comes floating down from God, to be collected by the other standing figure in the foreground. There is no space here to explain the significance of the ‘awning’; but it is important to grasp that the flakes of ‘manna’ are painted to resemble the consecrated wafer or host that we saw in the Last Supper, with the wall painting (fig. 32) reinforcing the typological link.

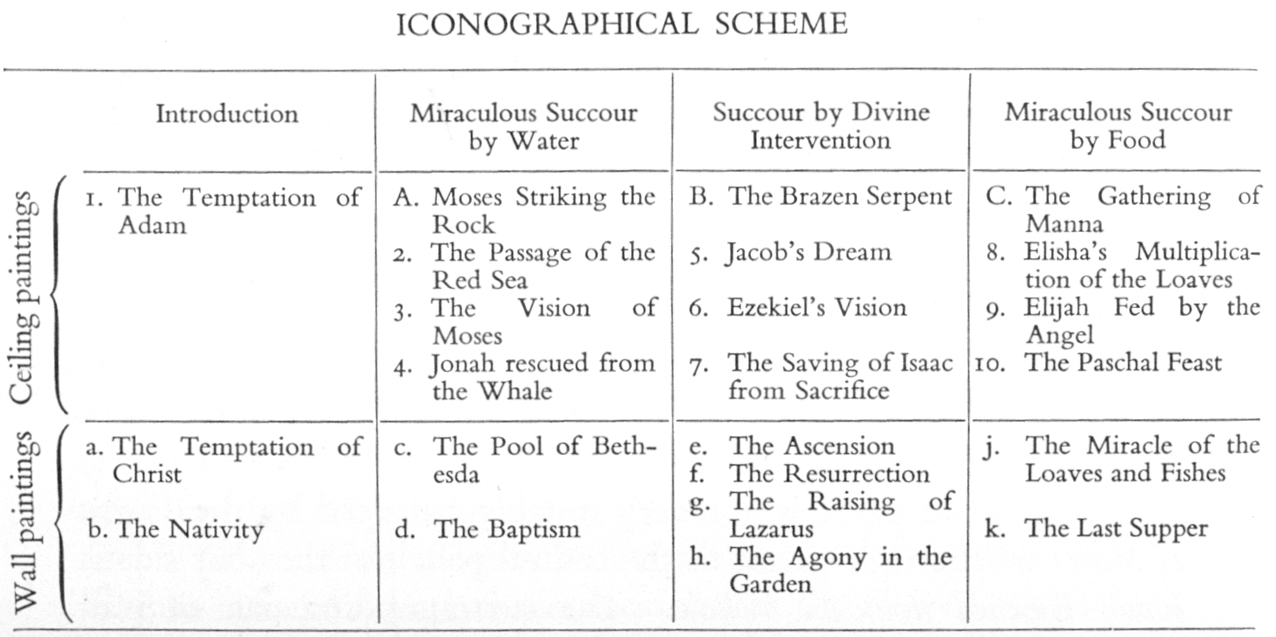

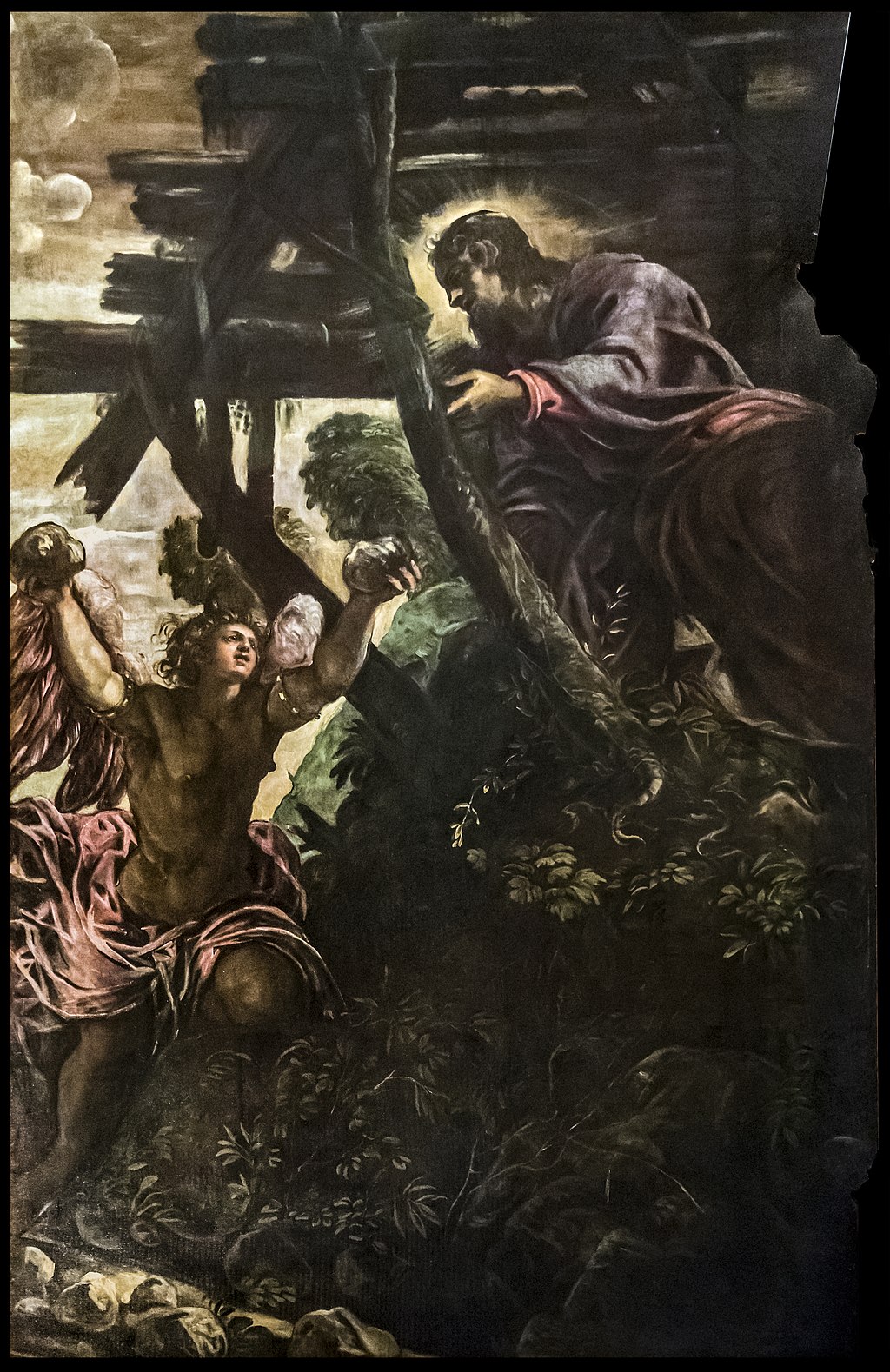

To the left and the right of The Manna, you will see the two ovals (fig. 34), twelve feet long, designed to be read longitudinally:

They are very much a pair. On the right, an angel plunges down from heaven, bringing (to quote I, Kings 19), ‘a cake baked on hot stones, and a jar of water’ to the prophet Elijah, who had fled from Jezebel into the wilderness and laid down under a broom tree saying: “Lord, take away my life, for I am no better than my fathers”. On the other side, we see his disciple Elisha, who, according to II Kings 5, anticipated the Feeding of the Multitude, by feeding a hundred men with twenty loaves of barley (these being painted good and big, as is the loaf-shaped cake). The Lord gives to the Prophet; the Prophet gives to the rest of mankind.

Finally in this section of the ceiling, we must look at the oval presented horizontally, and therefore twelve feet wide (fig. 35), between the altar wall and the Manna.

It represents the Jewish Passover—either the original event in Egypt (as described in Exodus, Chapter 12), when the angel of the Lord killed the first-born in every Egyptian home but ‘passed over’ the Israelites, or the annual feast observed ever afterwards in the same form—the feast which Christ was celebrating with his apostles in what Christians call the ‘Last Supper’, which in turn was regarded as a prefiguration of the Christian Holy Meal, the Eucharist.

So, in a dazzling feat of foreshortening from below (again: this is a ceiling painting), in a panelled room lit by candles—a study in brown and yellow—we see a family of Jews about to eat the Paschal Lamb, exactly as Moses prescribed: “In this manner you shall eat it: your loins girded, your sandals on your feet, your staff in your hand; and you shall eat in haste”.

At this point, you might like to pause and refer back to the two schemes taken from Eric Newton’s book (Figs. 23 & 24), where you can do a ‘recap’ of the paintings I have just shown you. It is at this point, too, that I shall break away from a strictly sequential presentation (for my own purely arbitrary reasons), and walk you down the room to the end furthest away from the altar, to the canvasses which are grouped round the huge rectangle, showing Moses Drawing Water from the Rock.

We shall begin with the horizontal oval furthest away from the altar, again twelve feet wide, which depicts the beginning of the history of Man considered as a free, moral agent—The Temptation (and, implicitly, The Fall). It links up, by way of contrast, with two of the ovals we have just looked at (Elijah and Elisha), because the ‘luminous’ figure of Eve (standing out against the dark green foliage of the Tree of Knowledge) is holding out to Adam a fruit that he has been forbidden to eat by God, instead of ‘a cake baked on hot stones’, of which God has invited him to partake.

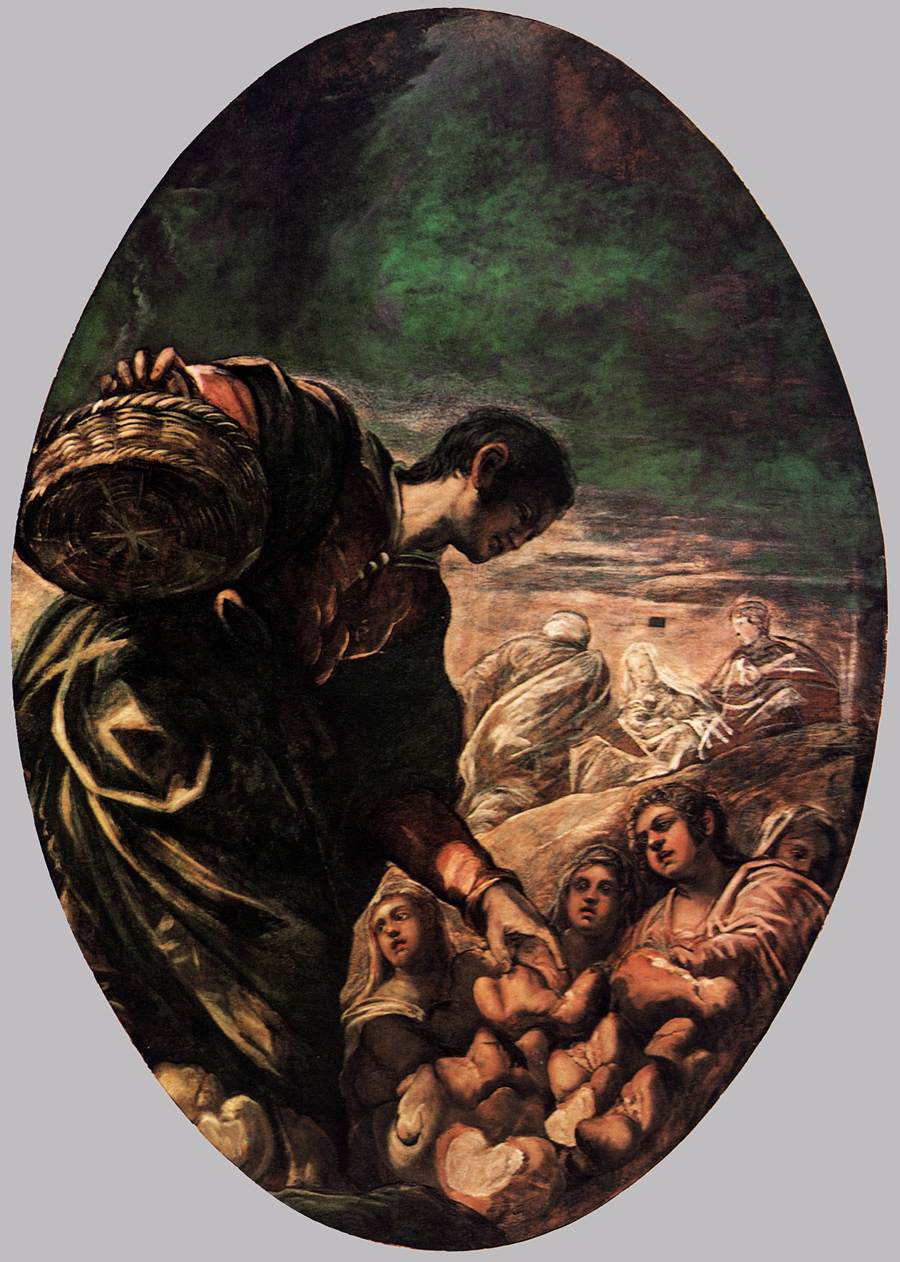

This scene is paired, typologically, with the New Testament wall canvas immediately underneath (marked (a) in the scheme) which is placed to your right as you face the altar. It stands a massive seventeen and a half feet high, but only eleven across, and it represents the Temptation of Christ by Satan.

Jesus is fasting in the Wilderness. He has made himself a primitive shelter, Robinson Crusoe style, by adding broken-off ‘horizontals’ to the ‘uprights’ offered by two curving tree-trunks). According to the Gospel of St Matthew, Chapter 4, he had been without food for forty days; ‘and afterward, he was hungry!’. The Devil appears and ‘tempts’ him—that is, ‘puts him to the trial’ for the first of three times, by saying: “If you are the son of God, command these stones to become loaves of bread”. But Jesus, unlike Adam, refuses the challenge with the words: “Man liveth not by bread alone”.

Again, we have dark green foliage; again a contrast of shadow and sky; and again the exploitation of the diagonal for the ‘bursting in’ of a supernatural being. But this is a fallen angel, beautiful but damned (it derives, incidentally, from a drawing of a statue by Michelangelo: cf. fig. 38). And Satan flies up from the depths, from the pit, rather than down from heaven, as did the angel who succoured Elijah in the Wilderness.

They are each twelve feet long; and what they have in common, if anything, is the element Fire, and the idea of a Beginning. On the left, you see an illustration of a story told in the Book of Exodus, Chapter 3. Moses has killed an Egyptian, run away from his kinsmen, married a Midianite, and is tending the sheep of his father-in-law on Mount Horeb. There the Lord appeared to him, ‘in a bush that burned and was not consumed’, and entrusted the reluctant Moses with the task of leading his people out of slavery into the Promised Land. We read that: ‘Moses hid his face, for he was afraid to look at God’.

The oval on the right shows us Moses in his role as leader. His staff of authority is held in his right hand; and you can make out a few of his followers, to the bottom left. He is not actually crossing the Red Sea (as Eric Newton would have it, in his anxiety to find water somewhere!), but he is being guided towards that sea on a nocturnal march (as we are told in Exodus 14) by what is variously translated as a ‘pillar of cloud’, or a ‘column of fire’. Here I can see a pillar or column on a cloud; I can also see a ‘fiery radiance’ from the Angel of the Lord, who is said to have ‘gone before the host of Israel’; and with a little good will, I suppose one could interpret Moses’ imperious gesture as one of separating the waters of the Red Sea in order to allow the Israelites to cross on dry land out of Egypt, into the wilderness and ultimately to the Promised Land.

Now that we are well ‘in’ to the story of Moses, we might as well stay looking at the ceiling, and go forward three chapters in Exodus to Chapter 17, which tells the story illustrated in the superb rectangle lying between these ovals, in reality fully eighteen feet by fourteen.

The episode occurs immediately after the story of the Manna, and hence we are already in the Wilderness on the far side of the Red Sea. As so often, the Israelites are on the point of mutiny, this time because they are suffering from thirst. So the Lord said to Moses: ‘“Take in your hand the rod with which you struck the Nile. Behold, I shall stand before you on the rock, and you shall strike the rock, and water shall come out of it that the people may drink.” And Moses did so in the sight of the elders of the people of Israel’.

Try and imagine yourself as being in the Sala, craning your neck backwards, looking high above your head up the dark rock face, with the usual dark foliage at the summit—looking up to where the ceiling should ‘dissolve’ to show the open sky, or the opening of heaven.

Again, there is a two-way movement of ascent (Jehovah is returning to heaven after ‘standing before Moses’), followed by a movement of descent, as water spurts out from the rock, which Moses has struck with his rod (fig. 41), down to the women below (all in the most ‘mannered’ of poses), who are catching the water in pitchers.

We have finished the Old Testament stories at this end of the Sala Grande, so let us look at the remaining three New Testament scenes, beginning on the left of the left-hand wall with The Nativity, or rather, The Adoration of the Shepherds (the shepherds being those to whom the angels first brought the ‘Good Tidings’, who were the first to worship Jesus, and with whom the poorer members of the School could most easily identify).

Once again, the great height of the canvas (fig. 42)—seventeen and a half feet—encouraged Tintoretto to adopt one of his favourite ‘split-level’ compositions; although what you see must have been a fairly faithful representation of a northern Italian farmhouse, with the animals on the ground-floor, and the Holy Family up in the hayloft, under the broad beams of the roof.

This is as irresistible as The Last Supper in its contrasts of light and deep shadow and its touches of realism: I am thinking of the wicker basket and the eggs, the cock picking up grain next to the wheel, the pitchfork in the rack, and even the symbolic peacock (who is a debt to tradition, no less than the ox, but is so dark and so bedraggled as to be perfectly in keeping with the stable. We are meant to enjoy the archetypal Tintoretto maid-servant (cf. detail in fig. 43), gesturing inwards, in front of the two elder shepherds (with their contrasts of highlight and deep shadow); the élan of the two younger shepherds (one reaching up and round with a gift of a chicken, the other stretching up to the higher level with his hat, and so guiding our eye to the two midwives, who are another debt to tradition); the cherubs peeping down in a flood of pink light (repeating the message of ‘Peace on Earth’); old Joseph, resting his chin on his staff; and perhaps the most expressive Mary that Tintoretto ever painted (cf. detail in fig. 44), lifting the veil to reveal the ‘brightness’ of the baby.

The River Jordan is flowing towards us, or away from us, on the diagonal, forming a little bay on the near bank, thanks to the huge black rock. This provides a dark background or frame to the young man, who is re-robing after the ceremony, to the mother, who is suckling a very large child, and—a very rare figure in this cycle—to a member of the Scuola in contemporary dress. In the fiery sky, the theatrical clouds part to reveal the Dove, symbolising the Holy Spirit, who descends from the Father, saying: “This is my beloved Son, in whom I am well pleased”.

Meanwhile, the far bank of the river (cf. detail in fig. 46) is lined with wraith-like candidates for Baptism (showing some of Tintoretto’s most daring and most dazzling brush-work in yellow on grey, to yield an effect so totally unlike our normal conception of Renaissance art). Jesus kneels on a sort of ‘pontoon’ (it is typical of Tintoretto that he should pay attention to such details within such an unrealistic setting) to receive baptism from his cousin John.

Exactly opposite, on the right-hand wall, hangs the canvas devoted to the episode of the Pool of Bethesda or Piscina Probatica, as it is told in the fifth chapter of the Gospel according to St John:

Again, our photograph (fig. 47) has been trimmed by the slide-maker, and in reality the work is fully seventeen feet square. It is the most repainted of all the canvasses in the room, but since I am trying to make you aware of the argument of the whole cycle, we ought to take it in, bearing in mind that it would have been painted only a few years after the devastating epidemic of the plague in 1575–77.

The vanishing point of the perspective system is behind Christ’s head (as it so often is). It is placed high so that we register the pool of healing water in the ground rather than the lovely vine-clad pergola above, and it is placed well to the right, so that space opens up again on the diagonal, and we can see all five of the porticoes (specified in the gospel text) which had become ‘changing rooms’ for the multitude of ‘blind, lame and paralysed’. We may note the contemporary realism as the mother shows Jesus the plague-boil on her daughter’s leg; but note too that Jesus is not talking to her. His words are addressed to the man in the foreground, who had been ill (we are told) for thirty-eight years, and had been waiting there for a long time because no-one ‘would put him into the pool when the waters were troubled’. Jesus told him: “Rise, take up thy pallet, and walk”; and you should be able to see that he is indeed taking up his pallet.

A glance back at the diagram in fig. 21 will reveal that we have dealt with the theme of Bread (at the altar end) and the theme of Water (at this end), but that we still have to examine the central block, visible in fig. 26, which I described as being the centre of the whole conceptual scheme.

It consists of nine paintings: four New Testament rectangles on the walls and four Old Testament ovals on the ceiling surround the Old Testament rectangle in the ‘epicentre’ (fig. 48), which was the first canvas to be painted (at the height of the plague), and is the biggest of them all, fully twenty-six feet by seventeen.

It shows Moses raising the Brazen Serpent, which had a special significance in 1576 because it was a healing miracle; but was always significant (as we noted in relation to Michelangelo’s pendentive in the Sistine Chapel, fig. 13) because the episode was universally interpreted (on the authority of the Gospel of St John) as a ‘prefiguration’ of the Crucifixion, which was the condition for the ‘healing’ of all mankind from sin.

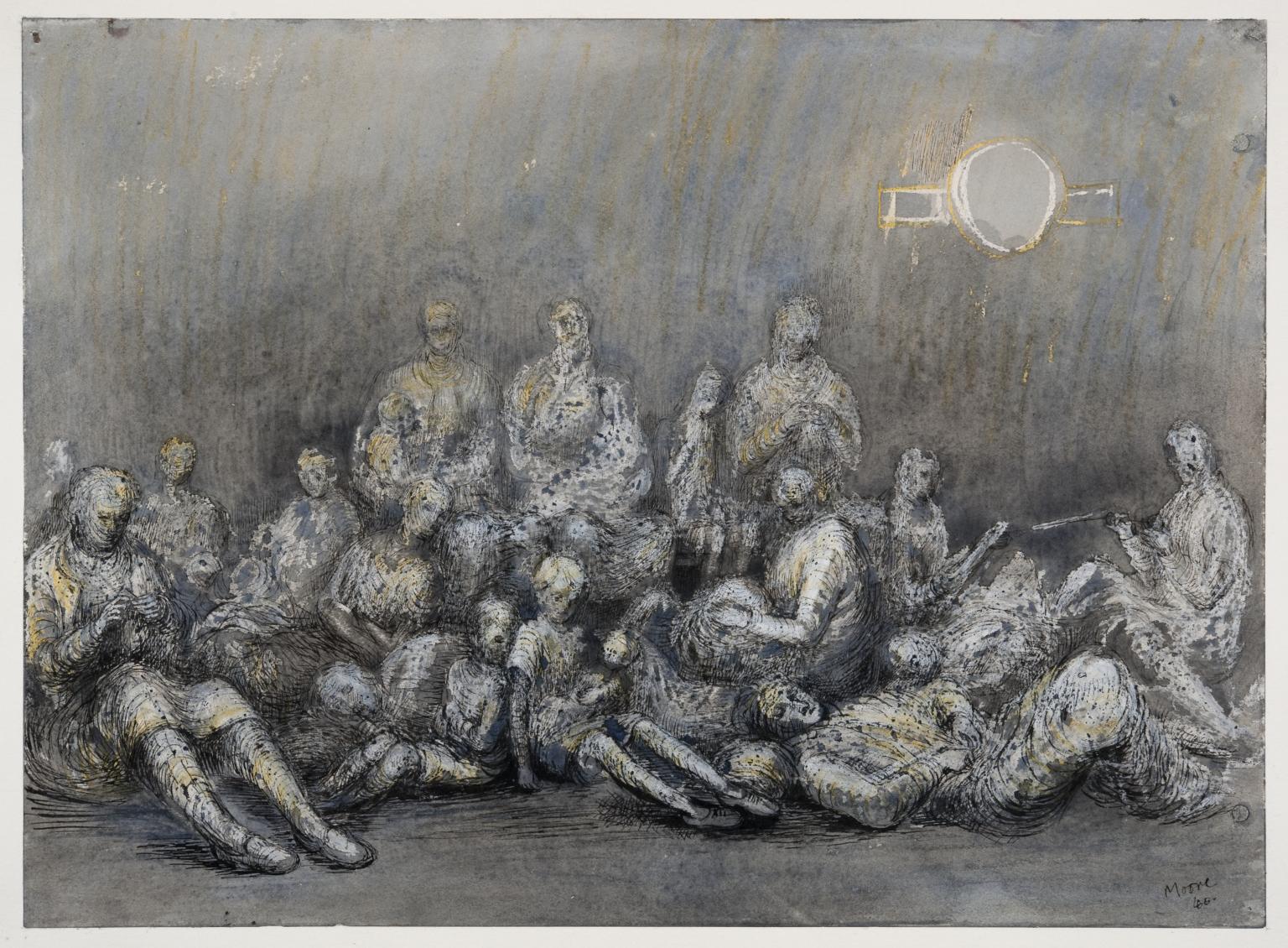

The canvas shows Tintoretto at his most feverishly, frenetically energetic, trying to outdo Michelangelo at his most mannerist. As I warned you, Titian’s Bacchus and Ariadne seems like a ‘sacra conversazione’ by contrast.

This scene was, once again, universally interpreted as a ‘type’ of the Crucifixion. And it is particularly important to keep the typological reference in mind, because the Sala Grande does not contain a representation of the Crucifixion—that lies in the smaller Sala dell’Albergo alongside.

LEFT [FIXME: slide missing, no placeholder ** TOM, I think we can safely leave the crucifixion out. But we’ve got to find the Agony, or scan it from a book, and insert it in the next paragraph]

There is, however, an allusion to the time of the Crucifixion, and a thematic link to the Sacrifice of Isaac, on the wall below, on the left, in the Agony in the Garden, (Figure 00 FIXME) another seventeen footer. This is one of Tintoretto’s most ‘surreal’ compositions in its contrasts of light and shadow, the huge area of dark foliage, and the complex poses of the sleeping figures of James, John and Peter, who are disturbed by the spectral soldiers led by Judas:

RIGHT [FIXME: slide missing, no placeholder TOM: see previous note

This thematic link consists in the fact that Jesus first asked that ‘this cup’ should be taken from him, but then, like Abraham, declared himself ready to do his Father’s work. However, the emphasis in this area falls not on doubt, betrayal and death, but on Triumph and Resurrection.

RIGHT [FIXME: slide missing: we need to find or scan]

The huge canvas on the right-hand wall (Figure 00 FIXME), directly opposite the Agony in the Garden, shows Jesus as being able to raise others from the dead, because the central figure on the upper level is Lazarus in his ‘grave clothes’—Lazarus who has been resurrected by Jesus, in answer to the prayers of his sister Mary.

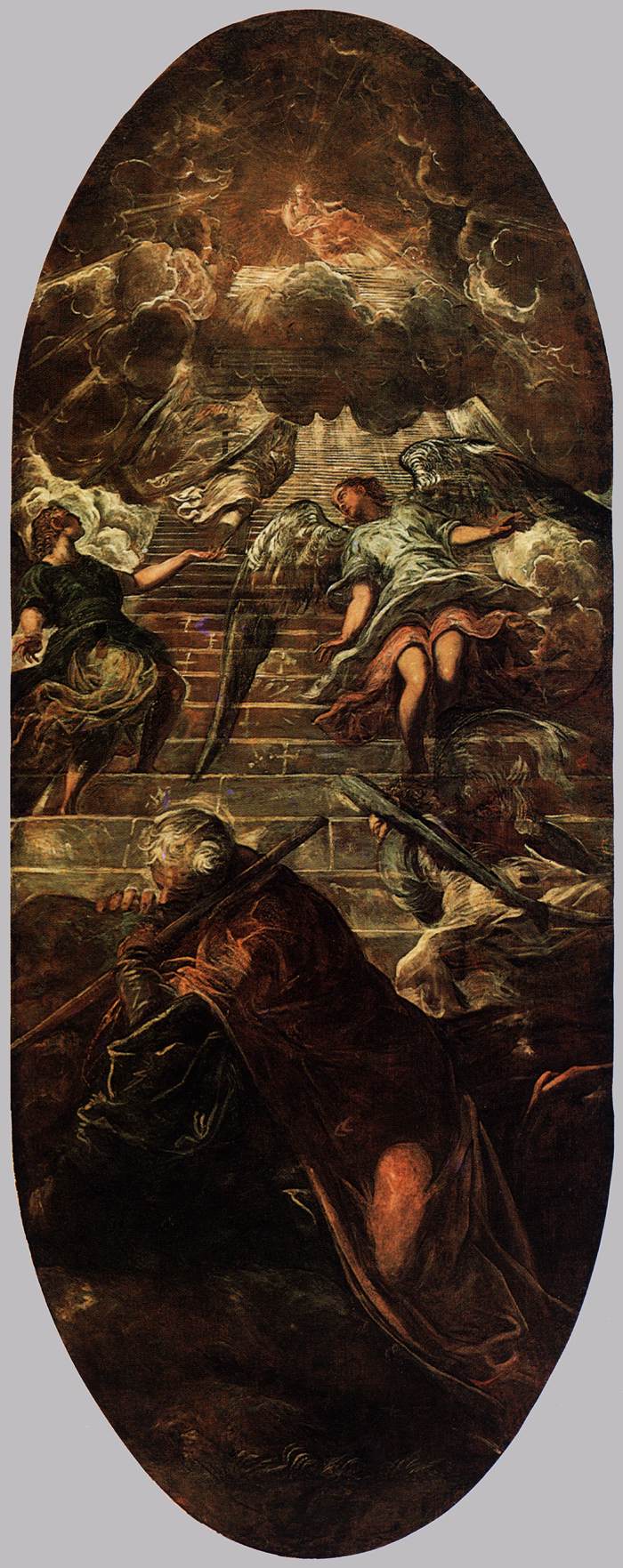

The two longitudinal ovals on the ceiling, flanking the serpent to the left and the right, are Old Testament prefigurations of the ‘opening’ of heaven through Jesus, and of the General Resurrection of the Dead on the Last Day. The first (Figure 00a FIXME) shows Jacob having his vision (as recorded in Genesis, Chapter 28) of a ladder reaching up to heaven, and of angels going up and down (remember, of course that the painting was designed to go on the ceiling); while the second shows Ezekiel, who had a vision (related in Chapter 37 of his own book) of a valley of ‘dry bones’ that were re-clothed in flesh and restored to life.

The last horizontal oval, meanwhile, shows Jonah, who at the Lord’s command is spewed forth from the mouth of the whale after spending three days in its belly—an event that was, following the authority of the Gospels, universally interpreted as a ‘type’ of the Resurrection of Christ, who rose from the dead after three days in the ‘pit’.

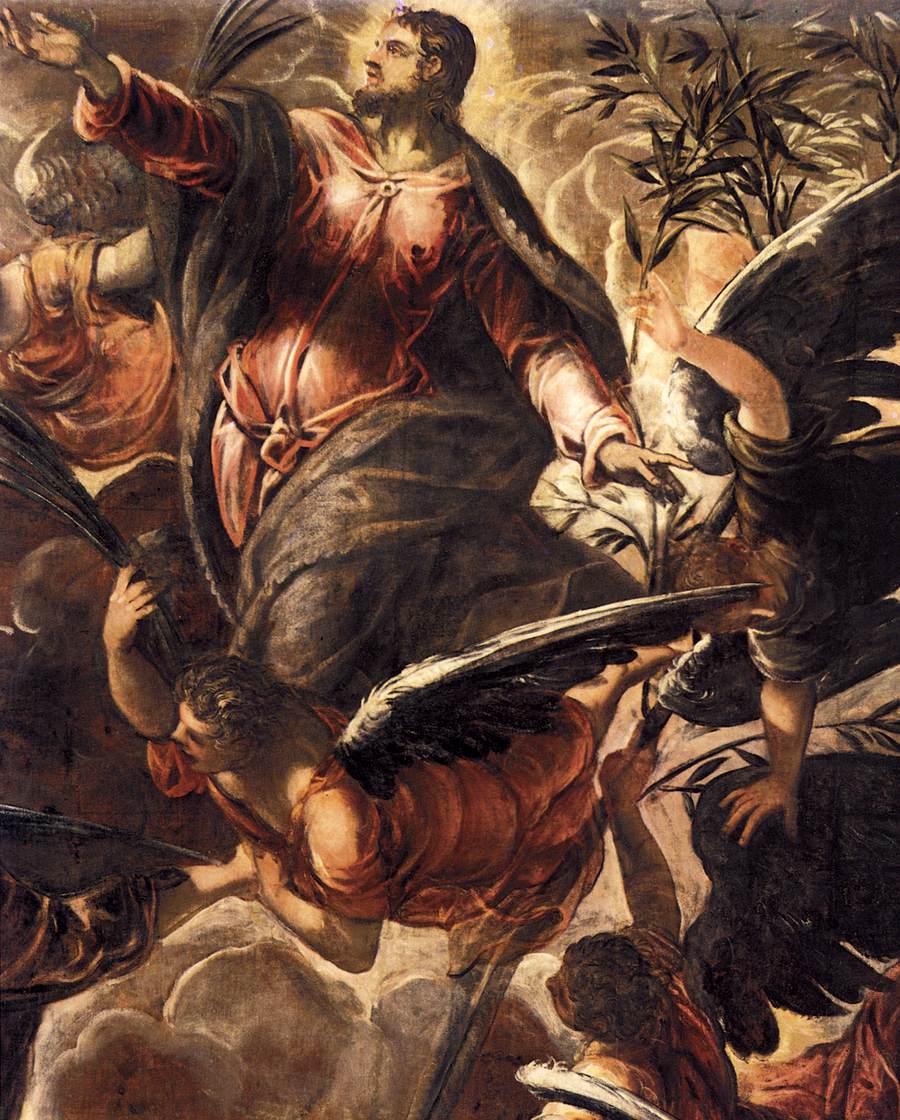

All that remain, then, are the ‘fulfilments’ of these ‘prefigurations’, which lie opposite each other in the centre of the walls, with the result that as you come up the stairs, you have The Resurrection opposite you (fig. 54a), and, as you leave, you will see The Ascension (fig. 54b).

The Resurrection is dominated, most unusually, by the four energetic angels who have been sent to move the massive stone; while the usually prominent sleeping guards (who have been sliced off by our slide-maker) are in any case almost lost in the gloom—our eyes being dazzled by the radiance of the Risen Body, the corpus gloriosum, of Christ.

The feeling of ‘ascension’ is perhaps more powerful here than in the picture nominally given over to the subject, where the gigantic clothed figure of Christ (cf. detail in fig. 56) seems to be carried sideways by the five angels with their palms and olive-branches, in an image which is perhaps more suggestive of the Second Coming.

The huge apostle in the foreground, with his book, makes one think more of St John, about to have his Revelation, than of St Luke, considered as the author of the Acts of the Apostles (where the Ascension is recorded at the beginning of Chapter 1). Meanwhile, the spectral figures of Moses and Elijah recall The Transfiguration on the Mountain.

But this is vintage Tintoretto—with the detail (in fig. 57) being as ‘phantasmagoric’ and as ‘prophetic’ as the detail of the horseman which I showed you at the beginning. This is the image Tintoretto wanted you to see (and to retain) as you leave the Sala Grande.

FIXME: Also search for “00”.

FIXME: PRESERVED IN CASE WE DECIDE TO CUT THE OVALS ON P. 51

I am not going to show you all of the images in this area; it is enough to know that the two longitudinal ovals are Old Testament prefigurations of Jesus’s power to raise from the dead and to open the gates of Heaven; and the horizontal oval shows Jonah being spewed out by the whale in a prefiguration of Jesus’s own resurrection after three days in the underworld. Meanwhile, one of the three remaining wall canvases shows Jesus himself raising Lazarus from the deal. But we must look at the two wall canvases that represent the ‘fulfilments’…