As the huge canvas in fig. 1 (42 feet across) suggests, in this lecture we shall be looking at something very different from the art of Tintoretto: not the dramatic vision of a man who saw supernatural beings and supernatural light bursting into the everyday world of a stable or inn; but an art that is essentially secular even when the subject is nominally sacred—for this painting actually began life as a Last Supper, intended for the refectory of a convent.

We shall be dealing with an artist (of whom the figure in the detail in fig. 2 is probably a self-portrait) who, when he was summoned by the Inquisition in 1573 because this particular painting seemed inappropriately ‘worldly’, tried to wriggle out of the charge by simply changing its title from the Last Supper to Feast in the House of Levi (the painting is now in the Accademia at Venice).

Our artist’s portrayal of the wealth and confidence of the Venetian nobility has come to determine our view of the culture of sixteenth-century Venice to such an extent that it is something of a shock to recognise that his surname is identical with the capital of Sardinia—Cagliari—and that the name by which he was usually known means ‘the man from Verona’—Paolo da Verona, or Paolo Veronese.

His home town, as you can see in the map in fig. 8, lies a good 70 to 75 miles west of Venice. It had been the centre of an important state back in the fourteenth century when Dante was a refugee there, and it remained prosperous and independent in spirit after it came under Venetian rule at the beginning of the fifteenth century. Notice too that it is relatively close to Mantua, which is a mere 30 miles to the south, and that it is no farther from Parma and Modena than it is from Venice. I stress these relative positions and distances to prepare you for the fact that the man who has come to epitomise Venice was formed under non-Venetian influences.

Paolo was born in 1528, which makes him ten years younger than Tintoretto and 40 years younger than Titian. He was the son of a minor sculptor, Gabriele da Verona, and the nephew of a local painter, Badile, from whom he learnt the rudiments of his craft.

He was certainly in Mantua, where he knew the Triumphs of Caesar and the Camera degli Sposi by Mantegna, the first great master of foreshortening and of perspective from below (or, as the Italians say, ‘from the bottom upwards’, ‘di sotto in su’); and I have particular reasons, also, for wanting you to remember a painting of the Conversion of St Paul from the year 1551 (fig. 10):

The tiny panel in fig. 11 was painted in 1517. Notice the colour-range of the robes and the physical type of the Virgin, which are entirely characteristic of Correggio, the first great painter from the city of Parma. And please go back to the map (fig. 8), to make sure you can find the positions of Vicenza, which was the birthplace of the architect Palladio, and Treviso, which is the nearest city to the villa which contains the main cycle of paintings in this lecture.

Paolo was a precocious youth, and his earliest certain surviving work is the altarpiece in fig. 12 (on canvas, seven feet by six), painted in 1548, when he was just twenty. It was done for the family chapel of the Bevilacqua family—the ‘Drinkwaters’—in a church in his native Verona, and is now located in the museum there.

It is fairly badly rubbed and abraded, but you can immediately see the debts to Correggio for the type of the Madonna and also for the range of colours. Take in the architectural setting, which provides the by now favoured ‘split-level’, but which is asymmetrical (with only one cut off pillar); and notice, finally, the complex, very agitated pose of St Louis of Toulouse, who is holding a book, looking up and to the right, while gesturing to the left. Even from this one picture, you will have registered that Paolo’s early colours, his composition, and his figure-style are clearly much indebted to Mannerism and to the artists of the central Po valley.

We know that he did some frescos on secular themes for two noble families who possessed villas in the neighbourhood of Treviso in 1551 and 1552; but let us instead follow him to his city of adoption, Venice, where in 1553 and 1554, he was hired to do some small ceiling paintings for the room where the Council of Ten met.

The classical allegorical-scheme here was probably devised by a certain bishop, Daniele Barbaro, of whom you will hear more in due course. The painting (fig. 13) is only about four and a half feet long, and it shows the goddess Juno, above, and, below, a personification of Venice seated on the lion of St Mark, who is receiving from the goddess three crowns, a laurel wreath, and coins in profusion. So you can see that, even in his first, small-scale, allegorical composition for the city, Paolo took as his theme Venetian power, glory and wealth. You can also see that he has already found his ideal woman—both Juno and Venice being variants, in proportion and colouring, on a type that will recur throughout his career.

I will not dwell on this, but show you another small ceiling allegory, probably from the same years and now in Rome (fig. 14), just three and a half feet high, in which the personified figure of Peace (or Strength) presses her foot against a branch, and uses a long torch to set fire to a suit of armour.

Here we already have the brilliant colours, the pale skies, and the mastery of foreshortening ‘from the bottom upwards’ which will recur again and again in the art of his maturity.

Paolo made his home in Venice from 1555 (when he would have been aged 27) until his death at the age of 60 in 1588. He lived well to the West of the city, near the small-to-medium sized church of San Sebastiano (cf. fig. 15 a & b).

The church belonged to an order of friars, the Gerolomini, who lived in clausura in the adjacent convent; and the Prior was a fellow Veronese and friend of the artist. Thus it is perhaps no surprise that Paolo’s first commission as a resident was for this very church. Paolo began work in the sacristy of the church in 1555, decorating the ceiling with several small Old Testament scenes arranged around the canvas you can see in fig. 16, in the centre:

Measuring six and a half feet by five and half, it represents The Coronation of the Virgin, and is still very close to the style of Correggio. Over the next decade, he covered virtually every surface in the church that could be painted: with scenes from the life of Sebastian (like that in fig. 17, left), with simulated columns and statues, or with scenes from the New Testament (fig. 17, right ** check subject).

By common consent, his finest achievement in the Church of San Sebastiano was the three large canvasses, in superb frames, done for the ceiling of the nave, and illustrating key moments in the Book of Esther, which he painted in 1556 and 1557, when he would have been coming up to thirty years of age. These canvasses made Veronese famous almost overnight, and since they constitute a ‘mini-cycle’ on the theme of Love and Marriage, I want to ‘give them the treatment’, so to speak, even though I only have two of the three pictures in colour.

The first of the three (fig. 20) lies immediately overhead as you enter the church, and measures a generous sixteen and a half feet by eleven. The scene represented comes at the end of Chapter 1 in the Book of Esther (which, I remind you, is a splendid oriental fairy-tale, worthy to be included in The Arabian Nights). The king, Ahasuerus, is said to reign over 127 provinces, stretching from India to Ethiopia. After three years on the throne, he has given a first banquet for the nobles and the governors of these 127 provinces which lasts no less than 180 days; and this is followed by a second banquet, the last phase of which is illustrated here, ‘in the courts of the garden of the king’s palace, lasting seven days’. (I should add that the description in the Bible of the splendid setting in the garden specifically mentions ‘marble pillars’.)

As you look at the picture, please keep in mind that you would be seeing it above your head, and that the frame is the underside of a horizontal cornice, which has been foreshortened from below, ‘di sotto in su’. ‘On the seventh day’, we read, ‘when the heart of the king was merry with wine’, he commanded that his queen, the beautiful Vashti, should be brought into his presence. She refused to come, and the king, after due deliberation with his nobles, divorced her by a decree that was sent ‘to every province in its own script and to every people in his own language’, a decree which dwelt on the moral: ‘that every man should be lord in his own house’.

In case you have not been able to work it out: the eunuch, almost hiding the king on his throne, has plucked the crown from the head of Queen Vashti; and she is being led down the steps by another eunuch (you can just see his face), while she holds her son by the hand. The figure sitting with his dog at the foot of the throne is the true hero of the tale. He is Mordecai, a Jew, a descendant of the Jews who were carried off generations earlier by King Nebuchadnezzar; and he is guardian to the beautiful Esther. When the king announced a kind of ‘beauty competition’ to find a new queen, Mordecai sent his ward to the palace with the other contenders for a twelve-month period of beautification (I said it was a fairy tale); and every day he used to pass ‘in front of the court of the harem, to learn how Esther was and how she fared’. Esther was eventually taken to the king, and ‘she found grace and favour in his sight more than all the virgins, so that he set the royal crown on her head and made her queen instead of Vashti’.

So here in fig. 21, in the rectangular canvas in the centre (it is the same width as the first), we are shown the throne, with its splendid canopy, from below, in another ‘subject’s-eye-view’. The king, with his gold sceptre, is in the act of crowning Esther, who is kneeling at his feet, inclining her head, her arms submissively folded, attended by two rather overawed companions. The absolute power of the Eastern monarch is a vital theme in the story, by the way, because to appear before him uncommanded meant certain death.

All this happens in Chapter 2, which ends with a seemingly irrelevant but later significant episode, in which Mordecai, ‘sitting as always at the king’s gate’, gets wind of a plot to murder the king, and discovers the plot to Esther, as a result of which the conspirators are hanged on the gallows.

The man at the foot of the throne in the second scene (cf. detail in fig. 22), scowling, his arms akimbo, wearing armour and talking to a dwarf, is clearly meant to be the villain of the tale, Haman, who (as we are told in Chapter 3) became chief minister to the king, and became obsessed with the fact that Mordecai, and Mordecai alone, refused to bow down before him and ‘do obeisance’.

The central part of the Book of Esther deals with the confrontation between these two—Mordecai and Haman. Haman himself conceived a new plot to murder all the Jews in all the 127 provinces. Mordecai again discovered the plot and persuaded Esther to intervene, which she did, appearing before the king, uninvited, at the risk of her life, in a much painted scene which Veronese does not represent in San Sebastiano.

Without explaining her intentions, she invited Haman and the king to a banquet at her palace on the following day. Haman construed the invitation as a mark of great personal favour, and, hoping to anticipate his revenge, consequently ordered that a gallows be built to hang Mordecai. But the king had a restless night; and in reading the Chronicles of his reign, he was reminded of Mordecai’s role in frustrating the earlier plot, and realised that Mordecai had not been rewarded in any way. He therefore resolved ‘to honour him’.

It is at this very moment that Haman appears at the palace. The king asks him, apparently in the abstract, “What should be done to a man whom the king delights to honour?”. Haman is sure that he himself is the man, and he lays it on pretty thick:

“For the man whom the king delights to honour, let royal robes be brought which the king has worn, and the horse which the king has ridden; and let the robes and the horse be handed over to one of the most noble princes; let him array the man whom the king delights to honour, and let him conduct the man on horseback through the open square of the city, proclaiming before him: ‘Thus shall it be done to the man whom the king delights to honour’.”

Then the king said to Haman: ‘Make haste, take the robes and the horse, as you have said, and do so to Mordecai the Jew, who sits at the king’s gate’.

So the subject of the third canvas (fig. 23), another oval, lying nearer the altar, is the Triumph of Mordecai. In yet another ‘subject’s eye’ view, we are shown ‘the open square of the city’, with a spiralling column supporting a balcony with many spectators. We see Haman, still in black armour, himself ‘one of the king’s most noble princes’, who is ‘conducting’ Mordecai ‘on a horse which the king has ridden, in royal robes which the king has worn’—and Veronese throws in a banner for good measure.

Haman is proclaiming (cf. detail in fig. 24)—no doubt between his teeth—“Thus shall it be done to the man whom the king delights to honour”; and needless to say, it is Haman who will be hanged on the gallows he had prepared for Mordecai.

The images to retain here are the two horses—and the differences between them—remembering all the time that you are seeing them above your head. Both are on the verge of a precipice, of disaster and death; but Mordecai’s white horse is restrained, held back, whereas Haman’s black horse is rearing and threatening to plunge over. Veronese seems to be recalling a very early painting of his own, a tondo for a ceiling (fig. 25), in which the very Mannerist horse of the Roman knight Marcus Curtius is being galloped by his rider, so that both will fall into a chasm that has opened in the middle of the Roman Forum.

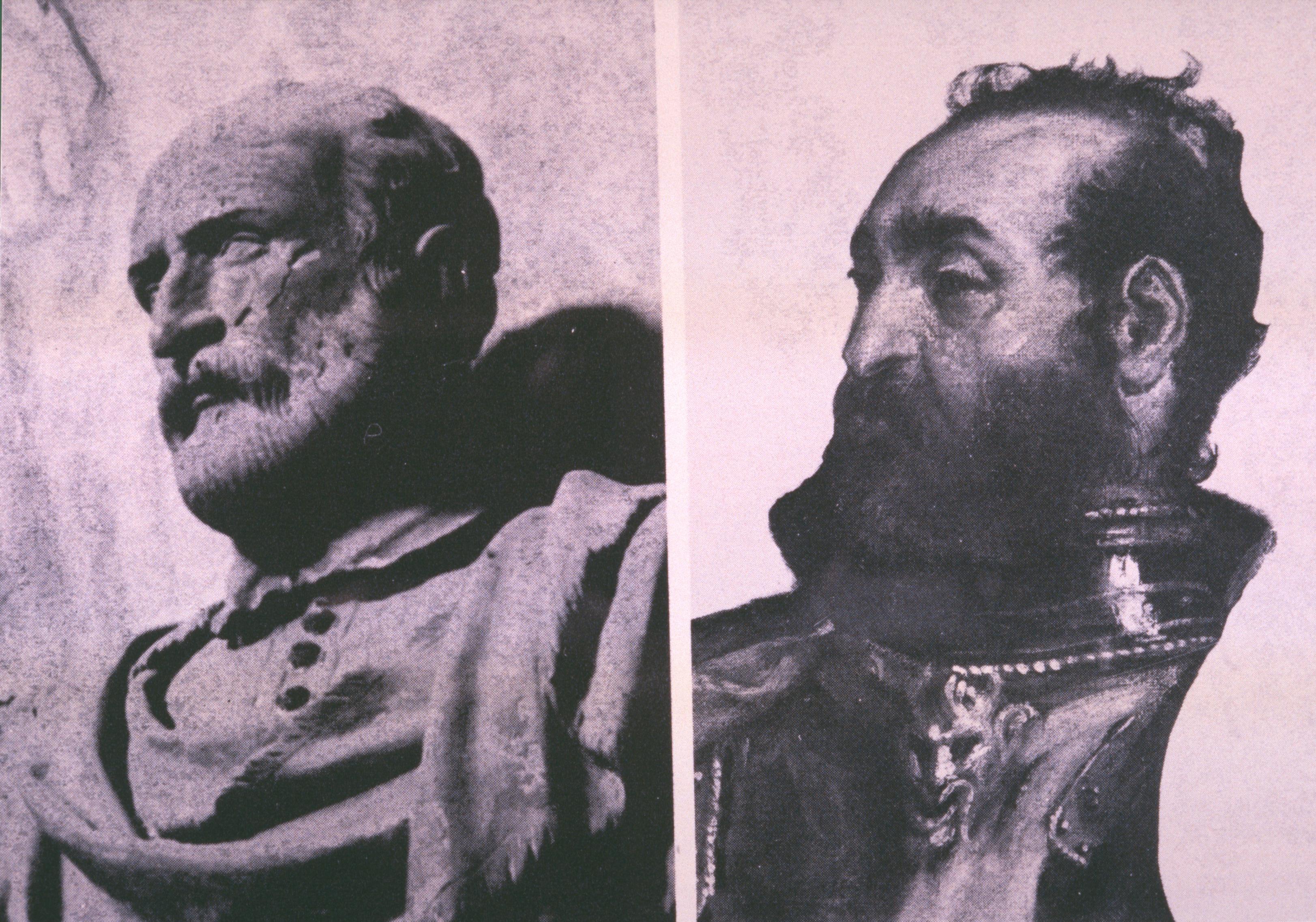

So much then for the Church of San Sebastiano. The success of these Esther canvasses, with their extraordinary command of perspective, together with Paolo’s earlier reputation as a fresco painter of villas, brought him to the attention of Daniele Barbaro (mentioned earlier), an extremely interesting man whom you see in fig. 26 (left and right) in portraits by Titian (done in about 1545) and Veronese (in the late 1560s):

In 1558, then the subject would have been ‘half-way between’ these two likenesses. Daniele had been born in 1514 of a very well-known noble family. He had received an excellent humanist education at the University of Padua, and he had written several commentaries to the works of Aristotle. Noble status carried obligations, and he became a diplomat. He was ambassador in England at the court of our Edward VI from 1548 to 51; then he became a bishop, and then patriarch elect of Aquileia (more of which in the next lecture), and it was in this capacity that he attended the Council of Trent, which met over a period of eighteen years from 1545 to 1563, and established what has come to be called the Counter Reformation.

Daniele’s own private passion, however, was classical architecture and the art of perspective. In the mid 1560s he would publish his own treatise on perspective, and his own translation (with commentary) of the Roman architect Vitruvius, in an edition with engravings by Palladio—this is the book he is holding in the Veronese portrait. What I am now going to show you is the much more significant, earlier fruit of the collaboration between these three: Barbaro, Palladio and Veronese.

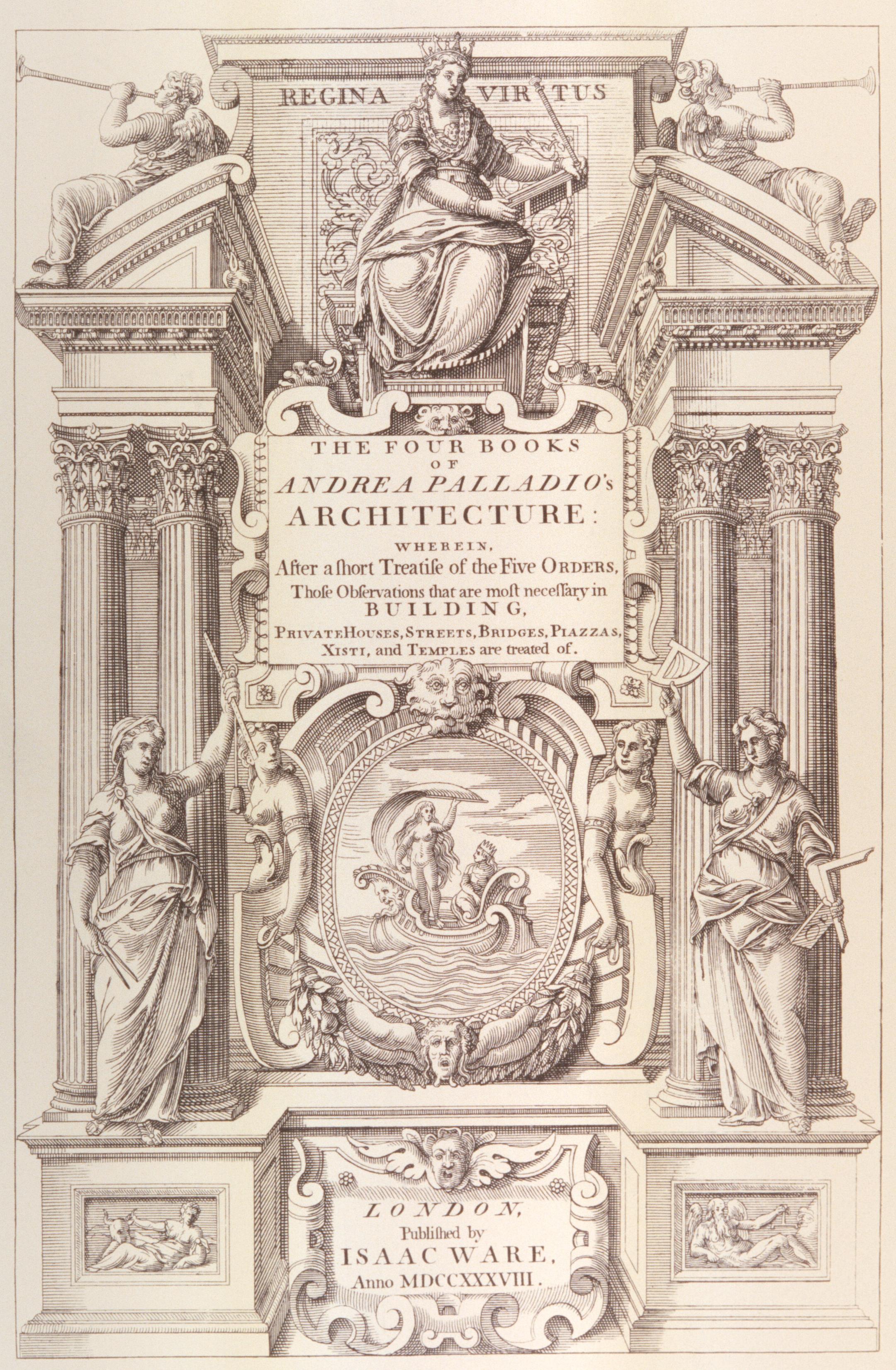

First, then, a few words about Palladio, which is a ‘name of art’ meaning the ‘architect of Pallas Athene’. His European influence was due to his famous Four Books of Architecture, to be published in 1570 with splendid engravings. The work was the condensation of thirty years’ experience as a practising architect who had made himself the leading expert on ancient architecture.

This brings us to our story. Daniele Barbaro, this connoisseur of architecture and of painted architecture, had a brother called Marcantonio, who was married with three sons. Daniele and Marcantonio got together to commission a superb new villa from Palladio, in the province of Treviso, near the village of Maser, about 30 miles north-west of Venice, and 30 miles north-east of Vicenza.

The building (fig. 30), which faces south, was completed by 1559; and although the dates are not certain, it seems most likely that Paolo exectuted his frescos there in two summer seasons—1559 and 1560, or possibly 1560 and 1561—when he was in his early thirties.

As you will have registered, the villa is typical of its architect in the classical proportions of the projecting central building (based on a temple façade), and in the perfect symmetry of the two low wings, which end in elaborate dovecots ornamented with large sundials.

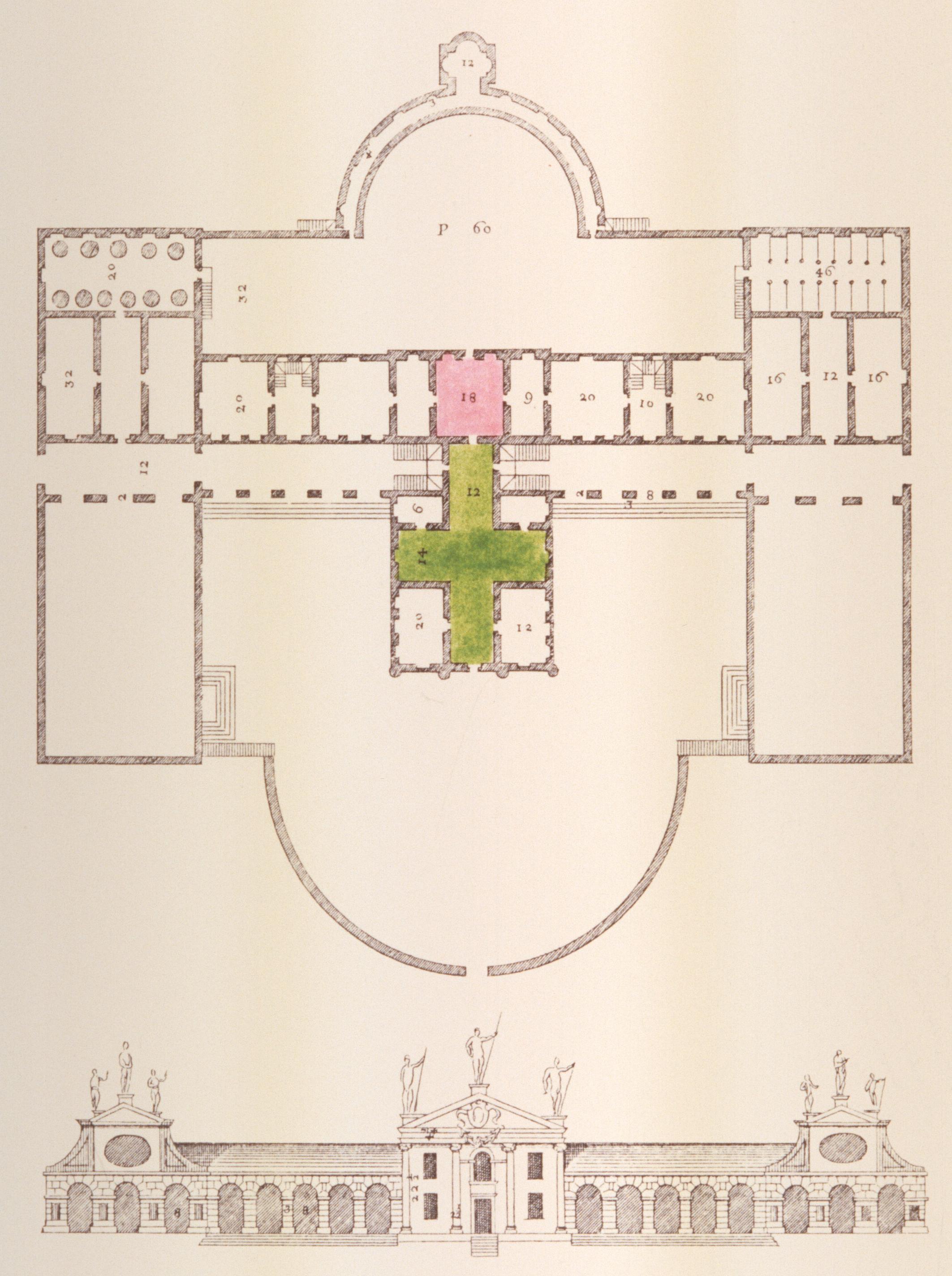

This first impression is confirmed by the plan (fig. 31), which is taken from Palladio’s own second book, and shows the low walls, the central block, projecting well forward, and the suites of rooms to the east and the west. The most important room, with the most elaborate decorations, lies at the intersection of the wings and centre, which is picked out in pink on the plan.

It takes its name from the subject of Paolo’s ceiling frescos in the room—that is, the ‘Room of Olympus’—and as guest of honour you would have been conducted there through the cross-shaped vestibule that I have coloured green, the ‘Sala a Crociera’, also frescoed by Paolo. If you were an intimate friend of the family, you might also expect to be taken to see his frescos in four other less public rooms in the central block.

So for the next part of this lecture, we are going to look at the cycle of decorations in the villa, not worrying too much about the symbolism underlying the choice of subjects and scenes, but bearing in mind that the whole complex programme was conceived by Bishop Barbaro and his brother, and that the main theme is Harmony as expressed in married love, and in the life of a family living amid nature tamed by man.

Mentally step down from your carriage in front of the villa, go up the steps, and walk into the cross-shaped vestibule (which is about 70 feet long by 12 feet wide on the longer axis, and 14 foot wide by 42 on the shorter), letting your eyes go first to the right-hand wall (**fig. 32a: TOM, supply caption), where the frescos shows pleasant vistas beyond a balustrade and a large blood-hound in the hall itself.

You will also see another door, half ajar this time, with a little page peeping out—one of the most charming examples of trompe l’œil painting in the villa (cf. detail in fig. 34), although you must remember that everything here is illusionistic: the door, the niches, the statues, the columns, the medallions, even the pile of pikes and halberds casting their shadows on the wall in the corner.

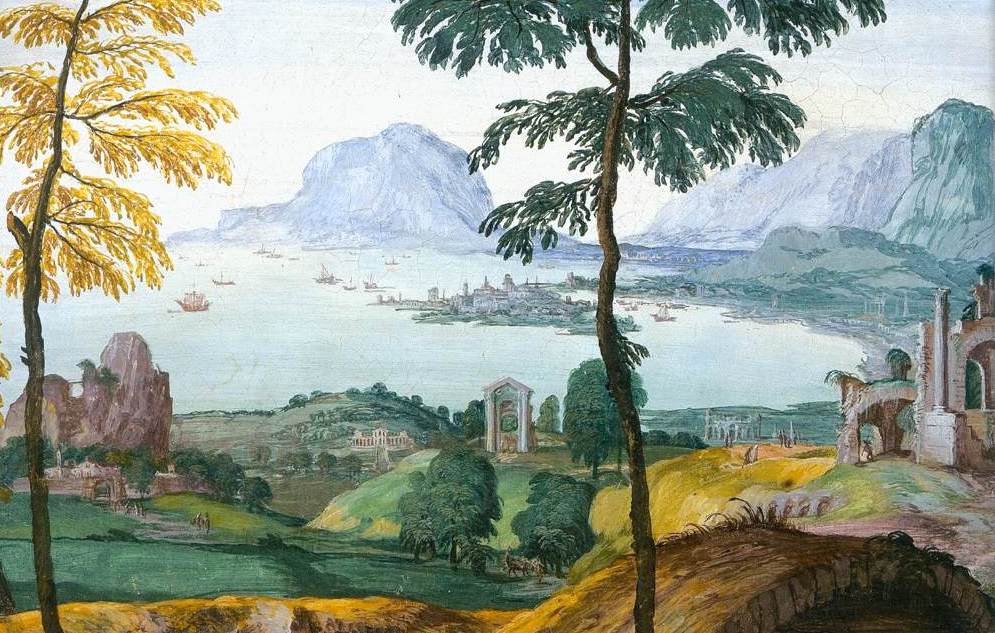

Instead, there are high cliffs (with diminutive fortified manor houses), a small lake with men on a punt, and a foreground, where sheep or cattle are grazing. Once again, two thirds of the area is sky, this time with cloud cover, allowing the rays of the sun to filter through. Not one of these features is all that compelling in itself, but together they offer a vision of Harmony in the relationship between Man and Nature in the ‘real world’—a kind of ‘Georgic’ poetry—and they are regarded as epoch-making in the history of art, because they are among the earliest examples of landscapes painted as landscapes, rather than as a mere background to human actors.

Now imagine that you have opened the East door, and are looking down to the end of the wing (fig. 40, left and right), where Veronese has painted a gentleman returning from the hunt, smartly dressed in his doublet and high collar, with an alpine hat at a rakish angle, his hunting horn slung on his hip, his boar-spear in his hand, and two dogs (a greyhound and a bloodhound) at his feet—a man in his early thirties, who is plausibly taken as a self-portrait of Paolo da Verona himself.

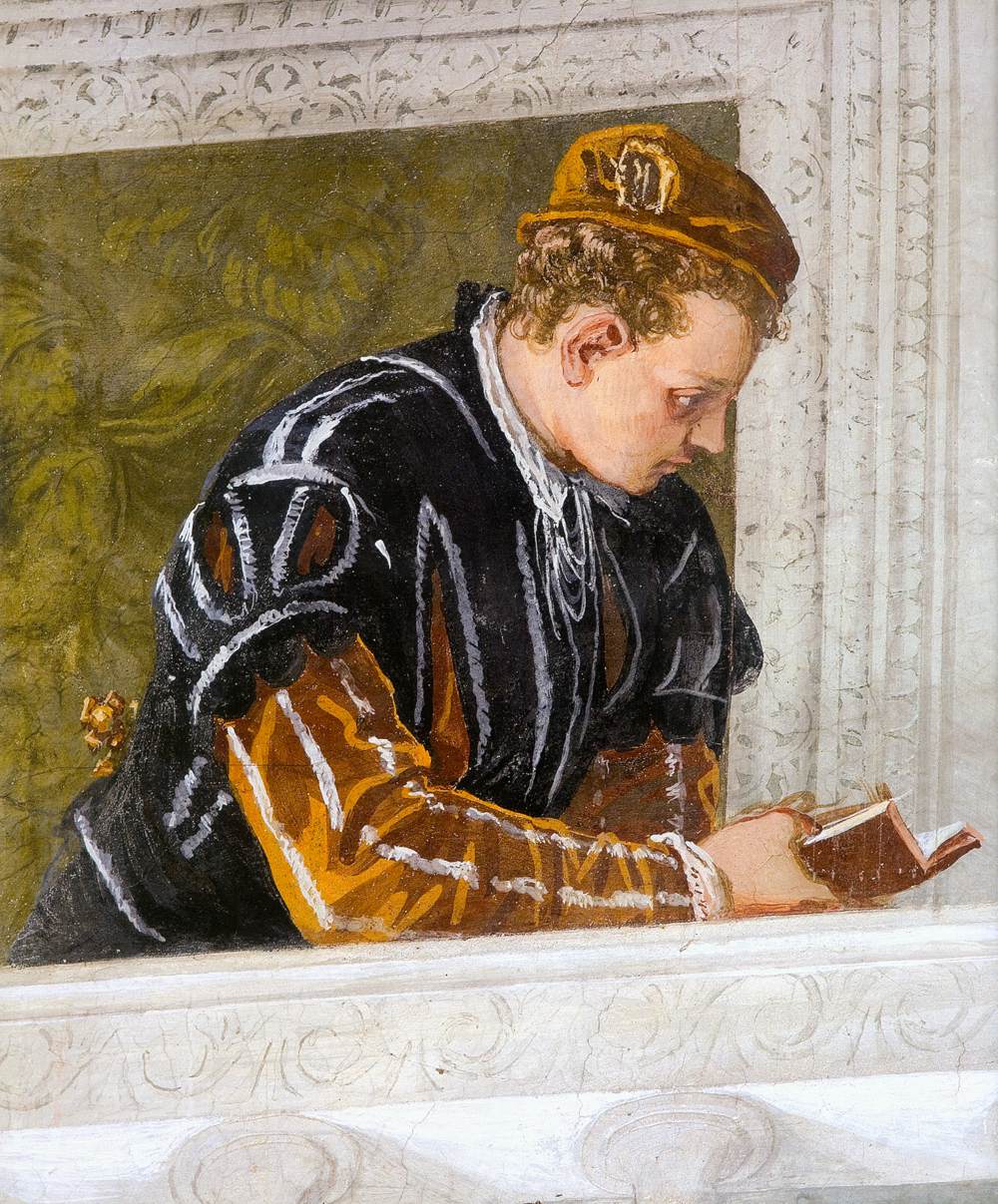

Now it is time to lift your eyes above ground level, above the realistic landscapes, the page, the artist, the working classes—to members of the noble family for whom the villa was built. If we stand in the Room of Olympus looking to the west, above the door this time, we see a balcony, with the two elder sons of the marriage (fig. 41): Francesco is reading a book on the left, and the younger brother, Almorò (whom I have picked out in the detail, fig. 42) is holding back his dog, who is straining after the pet monkey in the middle:

And if we look on the opposite east wall, again above the door (fig. 43), we see the head of the youngest son, a parrot, and the mother, Giustiniana Barbaro. She is wearing a dress with a lace shawl that matches her blue eyes and blonde hair, and is accompanied by her much older nurse or attendant (strongly characterised, fig. 44), who holds up her forefinger to restrain the lapdog from taking undue interest in the parrot.

Fig. 45 shows the splendid vaulted ceiling, looking north as you enter the Room of Olympus. In the very centre, an allegorical female makes a gesture of welcome (fig. 46)—she being variously interpreted as Divine Wisdom; the ninth Muse, Thalia, personifying Celestial Harmony; or perhaps, since she is seated on a Ram (Aries), simply a figure of Spring, Rebirth, or the beginning of the astronomical year.

Perched in the clouds around her, within the eight sides of the octagon, are seven gods and goddesses, and in fig. 47 you can see how effortlessly Veronese has handled the pictorial problem of getting seven to go into eight. These are the seven gods and goddesses who had been identified with the planets in the Ptolemaic universe; and they are arranged in the presumed astronomical sequence of their distance from the earth at the centre.

Thus we find Saturn, the furthest away and suitably melancholic; Jupiter, very impressive with his eagle; Mars, in bronze armour; Apollo with his lyre; Venus, with Cupid pointing to some music; and then the two innermost planets or gods—Mercury with his caduceus, and, most charming of all, the Moon, pictured as Diana the Huntress, who is being rather ‘soppy’ with one of her two hounds (fig. 48):

Thus we have Neptune as Water (with, for identification, his trident, a Triton and a conch); Juno, with a swallow, as Air; Vulcan as Fire; and Cybele, with a lion (and the usual castle on her brow), as the element Earth.

Between these corner figures, the simulated marble reliefs symbolise the states of being that come about when the celestial influences and the elements combine harmoniously; and below these, we have details (fig. 50) of Fecundity (a lady with an extra pair of breasts), and opposite, Good Fortune (with a section of Fortune’s wheel).

Last, not least, the two lunettes over the north and south entrances (fig. 51) have frescos symbolising the Seasons: Winter and Spring to the South (with Vulcan and Venus, who has been delivered of a new child); and Summer and Autumn, the time of harvest and of the grape harvest, a festival presided over by Bacchus.

Here you can see the by now familiar recurrent features of simulated medallions in the dado and simulated allegorical statues on either side of a landscape; and we must have a closer look at this landscape (fig. 55), since it shows us half the façade of a splendid villa in the Veneto at the end of an avenue of trees along which a coach and horses advances, presumably carrying the noble family back to the city for the winter:

It shows Bacchus making the gift of wine to gladden the heart of mankind, and specifically (as we also saw at Ferrara), to kindle sexual desire—not promiscuously, but within marriage. Indeed, the whole picture might have as its epigraph a line from the Aeneid, where Dido prays ‘May Bacchus be present, the giver of joy, and also good Juno’, Adsit laetitiae Bacchus dator, et bona Juno.

We may suppose that the corresponding room across the vestibule was the principal bedroom; and we may imagine Marcantonio, having taken a glass of wine, crossing over to the other side, and coming in through the statued-framed door (fig. 58).

It clearly shows a female plaintiff, kneeling in supplication between two male officers, and a male judge with two female attendants, one of whom puts her fingers to her lips, as if to counsel the wife not to disturb the matrimonial peace. Meanwhile, little Cupids rain down petals of ‘reconciliation’ or ‘harmony’ from above, the petals being about to fall on the bed below. Such a ‘chauvinist’ interpretation would accord well enough with the Pythagorean motto inscribed over the fireplace: ‘Don’t poke the fire with a sword’ (ignem gladio ne percutias).

The connection that Daniele Barbaro seemed to want to establish between the themes of celestial harmony and domestic harmony—Love in Wedlock—would be confirmed by the little group of musicians (fig. 61) playing ‘in concord’ over the fireplace (a trio of viol-players, linking the early Coronation in San Sebastiano, with the detail in the later Marriage of Cana).

It is possible to visit the Villa Barbaro but as Maser lies a little off the beaten track, I thought I would end the lecture with yet another cycle—a mini-cycle—on the theme of ‘Love and Marriage’. This one is far more accessible, because the four canvasses in question are to be found in the National Gallery in London, in a room which is simply crammed with paintings by Titian, Tintoretto and Veronese.

We do not have any documentary evidence about the date of these National Gallery paintings (although, recently, critics incline to the mid-1570s), nor about the circumstances of the commission or the original layout. Nevertheless, I am in good company when I assume that they were ceiling paintings, done for the matrimonial bedroom of a nobleman—in principle, just like the Room of Conjugal Love in the Villa Barbaro.

Two characters appear in each of the four scenes: Cupid, symbolising sexual desire as a fact of life, morally neutral, to be judged good or bad according to the circumstances; and a bearded man, therefore mature, old enough to know his own mind and be responsible for his actions. I shall assume that the man is intended to be the same in each painting, and that what we are being shown is an ‘Education of the Passions’ (‘Education sentimentale’). If it is a narrative cycle, then the painting in fig. 62 must represent the first of the four stages; and there is some internal evidence to suggest that it lay to the west, or, if you prefer, to the left, of some unknown central decoration.

What is going on? Under the pinnate leaves of a twisting tree and bough, our hero, lightly dressed—dressed for pleasure – in a yellow tunic under a red doublet, is greatly taken by the charms (all of which he can see) of the gorgeous blonde woman whose hand he is holding. She is naked to the waist, and wears bracelets of pearls; her left calf is lovingly embraced by one Cupid, while another is playing amorous music on the spinet. All of this suggests that she is ‘no better than she should be’, or, at least, that she represents a ‘daughter of Venus’ in the astrological sense, that is, a woman arousing and feeling sexual desire.

The ‘moral’ of the picture—from the point of view of our hero—is that such a woman, whether her affections are to be won by love or by money, is just as fickle or inconstant as he himself is, when he is drawn by his sexual appetite to her, or to another of her kind. This is because the whole point of the picture is that she is holding our hero’s hand while passing a note to another admirer—young, beardless, still with his coat on, still ‘in the ante-chamber’, so to speak. His gaze seems more passionate, more ardent, than that of our frankly admiring hero; and it is his gaze that she returns.

The letters on the note she holds have been read and ‘filled out’ to yield the sentence: ‘Who possesses me?’. However, one cannot be sure of this reading, which may have been influenced by the received title of the painting, which is Unfaithfulness.

The painting in fig. 63 would be the second stage in the ‘Education’; and it may have lain to the north, that is, ‘at the top’ of the hypothetical central decoration. Our hero lies on his back, wearing no more than a loin-cloth (his body being a tour de force of draftsmanship), on what would seem to be the base of a classical temple, very like the architecture in the Esther cycle.

This temple or shrine seems to be dedicated to deities symbolising our animal nature, because the armless and legless statue looks like a Herm, while the other is clasping the pipes of Pan at a suggestive angle. The man is quite certainly being beaten by Cupid, who is using his bow as a club, rather than to shoot arrows; but it is not clear whether the beating expresses simply the torments of unrequited passion, or whether it is a punishment for his unbridled desires.

The traditional title for the picture, going back to 1727, is Scorn; and this suggests that the man’s suffering, or his punishment, is caused by the shapely woman, who inflames him with her white bosom and provocatively placed elbow, but who is listening to the voice of her chaperone, or of her conscience—the figure who is primly dressed with a high-collar, and clutches a white ermine, which is an emblem of chastity. The man is being ‘scorned’—rebuffed—and that too is part of a Sentimental Education.

The third scene (fig. 64) clearly makes a contrast with the second, and it may very well have lain to its right, to the east of the central ornament. It must also have been in a kind of ‘Chinese box’ relationship to the original room, since it is a picture designed for the ceiling of a bed-chamber, which shows a bed-chamber with a picture on the ceiling!

Returning to the idea of contrast, this time it is a woman who reclines, while our hero stands to one side, dressed for outdoors, with a green cloak over the yellow tunic, and he is accompanied by an older companion of the same sex. The woman is fast asleep on the ravishingly painted linen sheet and crimson bedcover. She is attractive and vulnerable, like Lotis in Bellini’s painting for Alfonso’s camerino (fig. 65); and Cupid seems to urge our hero to seize his opportunity just as Priapus tried to do.

However, the man listens to his elder companion, and he is thinking of one of the great examples of ‘Continence’, of Self Denial, set by the great Roman general, Scipio, which is actually represented in the ceiling fresco within the painting; and he makes a gesture of renunciation. He finds the girl highly ‘appetising’, he has sexual appetite; but he is able to discipline and control his desire. The traditional title is Respect.

The received title for the fourth and last canvas in fig. 66 (which might have been placed to the south, that is, at the bottom of the original layout) is Happy Union; and there is no serious disagreement about the meaning in this case. Our hero, dressed in yellow over green this time, is accompanied by a dog, symbolising fidelity (which is why dogs are often called Fido). He does not hold his lady’s hand (as he had done with the girl in the first scene), but both of them clasp an olive-branch as a symbol of Peace and Harmony. The lady is dressed, neither provocatively nor prudishly, in a handsome pink brocade, the underrobe covering her arms and breast, but setting off her broad neck with its pearl necklace and the pearl ear-ring above the very handsome brooch; and her hair flows freely down her side.

Cupid has placed a golden chain about her, and she is about to be crowned (perhaps for her constancy in love) by a full-breasted personification of Good Fortune or Fecundity (you will notice the Cornucopia, and remember the pairing of these images in the Room of Olympus). If the four paintings are intended as a story about ‘Love and Marriage’, then the last words would undoubtedly be: ‘They lived happily ever after’.