The opening pair of images (fig. 1, left and right) are of annual festivals in Venice in the eighteenth century—Ascension Day in front of the Doge’s Palace, and the Regatta on the Grand Canal. Both were painted by Canaletto in the later 1730s; and I show them to remind you that although the economic and political historians of today can see that the republic of Venice suffered a major decline in the 150 years that have passed since the time of Veronese, this was by no means obvious to the Venetian ruling class, nor to the aristocratic travellers from England who commissioned paintings like these and took them home as souvenirs of the Grand Tour (which is why they are now in our National Gallery).

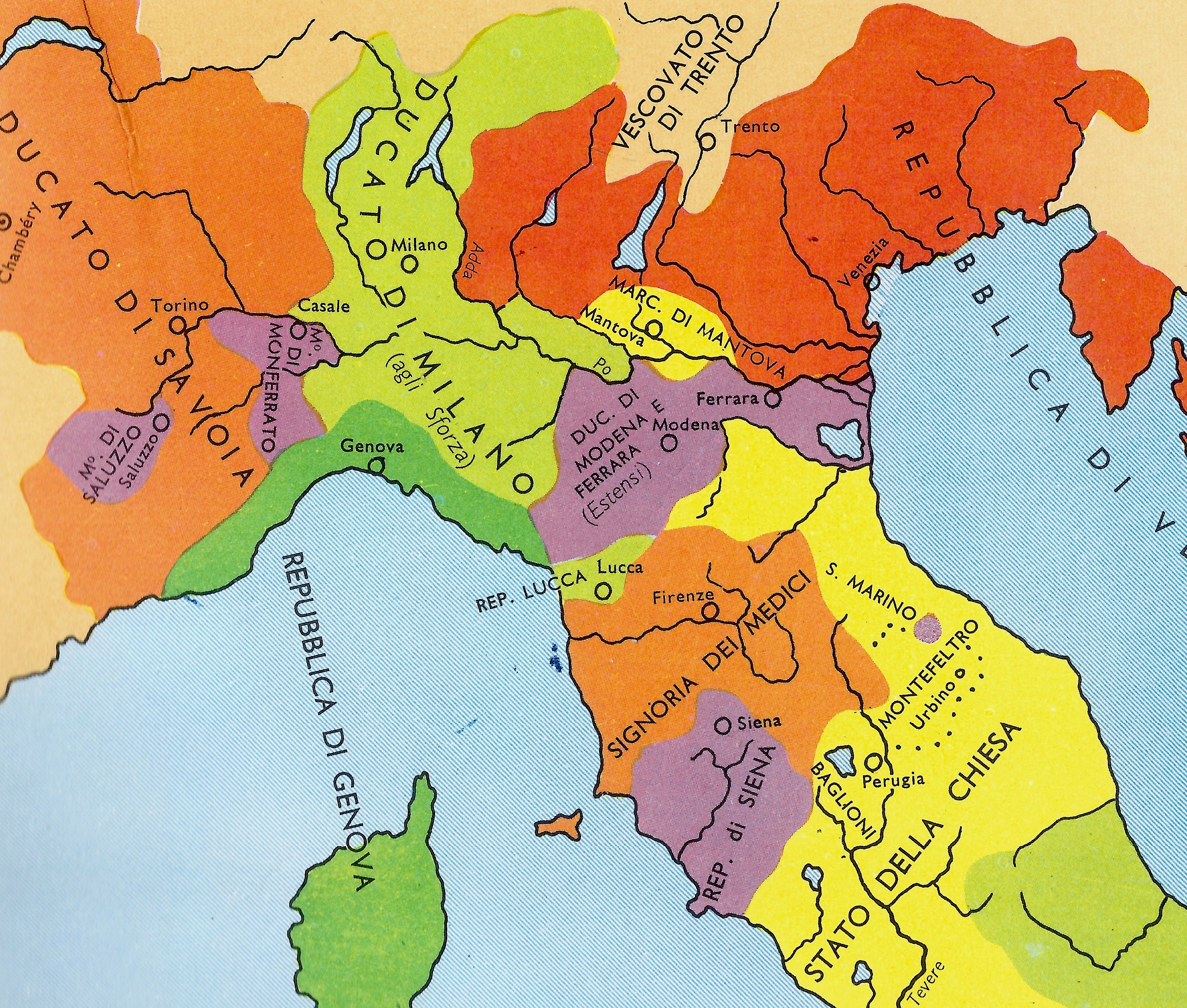

The Wars of the Spanish Succession, concluded by the Peace of Utrecht in 1713, and then the wars of the Polish and Austrian Successions in the 1730s and 40s, made very little difference to Venice (whose territory in 1740 is coloured in red in the map in fig. 2), except that Austria now controlled all the lands shown in green at the top of this map, including Lombardy and Mantua, and that the new grand Duke of Tuscany was a son-in-law of the Hapsburg emperor.

Yet Venice’s borders remained more or less where they had been back in 1450 (cf. the map in fig. 3). Money was still available to be ‘spent conspicuously’, and the building of new palaces and churches gave plenty of opportunities for architects and painters. It was into this city that we feel we know so well from Canaletto, near the Arsenal (the military dock-yard), that Tiepolo was born in 1696—a date which makes him about 10 years younger than the great musicians, Bach and Handel (both 1685), Rameau (1683), Telemann (1681) and Vivaldi (1680), and a little less so than the writers Voltaire (1694), and Alexander Pope and Marivaux (both 1688). He is, then, exactly the same age as Canaletto and Hogarth (both 1697), and a fraction older than Chardin (1699) and Boucher (1703).

It would be hopeless and counterproductive to try to even sketch the shifts in taste and the developments in the art of painting that had taken place between 1580 and 1720; but it may be as well to ‘get our bearings’ by establishing a couple of ‘points of reference’.

The first of them is none other than Paolo Veronese, whose huge canvasses were still on view in Venice—at the time, the work in fig. 4 was still in the refectory of the convent attached to the church of Saint George, on the island opposite the Doge’s Palace—and Veronese’s colours, costumes, mastery of perspective, and even the very buildings in his pictures, were being freely copied and adapted in the later seventeenth and the early eighteenth centuries.

The altarpiece in fig. 5 is by Gregorio Lazzarini, the master to whom Tiepolo was apprenticed; and as you can see, it draws on Veronese’s Wedding at Cana for the spirit of the classical buildings to the left and the right, as well as for the campanile.

Second, although Veronese remained a vital presence for so long after his death, there was also a recognisable contemporary Venetian, style embodied in the work of three artists: Ricci (1659–1734), Pellegrini (1675–1741), and Amigoni (1682–1752).

This was a style much appreciated in the courts and noble villas throughout Europe, from Madrid to St Petersburg. All three artists travelled widely, and all of them spent some time in England. The acknowledged master was Sebastiano Ricci (the oldest), and in fig. 6 you can see a highly relevant example of his grand style: an altarpiece, thirteen feet high, dated 1708, done for the church of San Giorgio Maggiore; and which, unlike Veronese’s Wedding at Cana in the convent next door (which was later looted by Napoleon), is still in position.

The composition seems perfectly effortless in the placing of the figures, either one above the other (Peter talks to the bishop, the nun adores the child, the bald man ponders the words in the book), or to the side of the marble throne, topped by its canopy. And the whole canvas is most enjoyable, and very typical, in its light, bright colours, with predominant yellows, cream and blue, ochre, and various splashes of red.

His pupil Amigoni (with an M for Michael) was to spend much of the 1730s in England, after a ten year stay in Bavaria where he did the ceiling fresco you can see in fig. 8, showing a bearded Ulysses who traps the youthful Achilles (in women’s clothing) into betraying his identity by making him draw his sword.

Achilles, you remember, had been taken by his mother, Thetis, to the court of King Lycomedes, disguised as one of the King’s daughters (of whom we see at least a dozen). Notice again the bright colours; the virtuosity of the perspective ‘from the bottom upwards’; the rather ‘magical’ treatment of the figures who seem to be ‘dissolving’ on the skyline; the theatrical movements of all the actresses and of the actor ‘in drag’: in all these features, this is a painting in the spirit of ‘opera seria’, the genre with which Handel was currently triumphing in London.

Last of the group (fig. 9) is an easel painting, no more than four feet high, by Pellegrini (who was about twenty years older than Tiepolo). It was painted, in all probability, during the artist’s five-year stay in England between 1708 and 1713. It is now in our National Gallery, and it shows an Old Testament subject—Rebecca and Abraham’s servant-cum-emissary at the Well—which is treated in just the same light-hearted spirit, with the same theatrical costumes, the same facial types, and the same ravishing colours that we shall find in Tiepolo’s frescos at Udine.

So much, then, for fashionable, internationally popular, Venetian art in about 1710. Our third reference point will consist of two painters, not so widely patronised in Europe, whom Tiepolo is known to have studied closely when he was a young man. These are Bencovich (1677–1753) and Piazzetta (1683–1754), who are contemporaries of Pellegrini and Amigoni, but are very different in their composition, mood and colour, since they are looking backwards, through the School of Bologna, almost as far as Caravaggio.

Fig. 10 shows Bencovich interpreting another classical story—another of the events in the build-up to the Trojan War. It shows the Sacrifice of Iphigenia, and was painted in 1715, measuring five and a half feet high by nearly ten. Here we see Iphigenia the victim, Calchas the priest, and Agammenon the father; it is dark in tonality, limited in palette (with no reds, greens or blues), very dramatic in the lighting, and tragic in feeling.

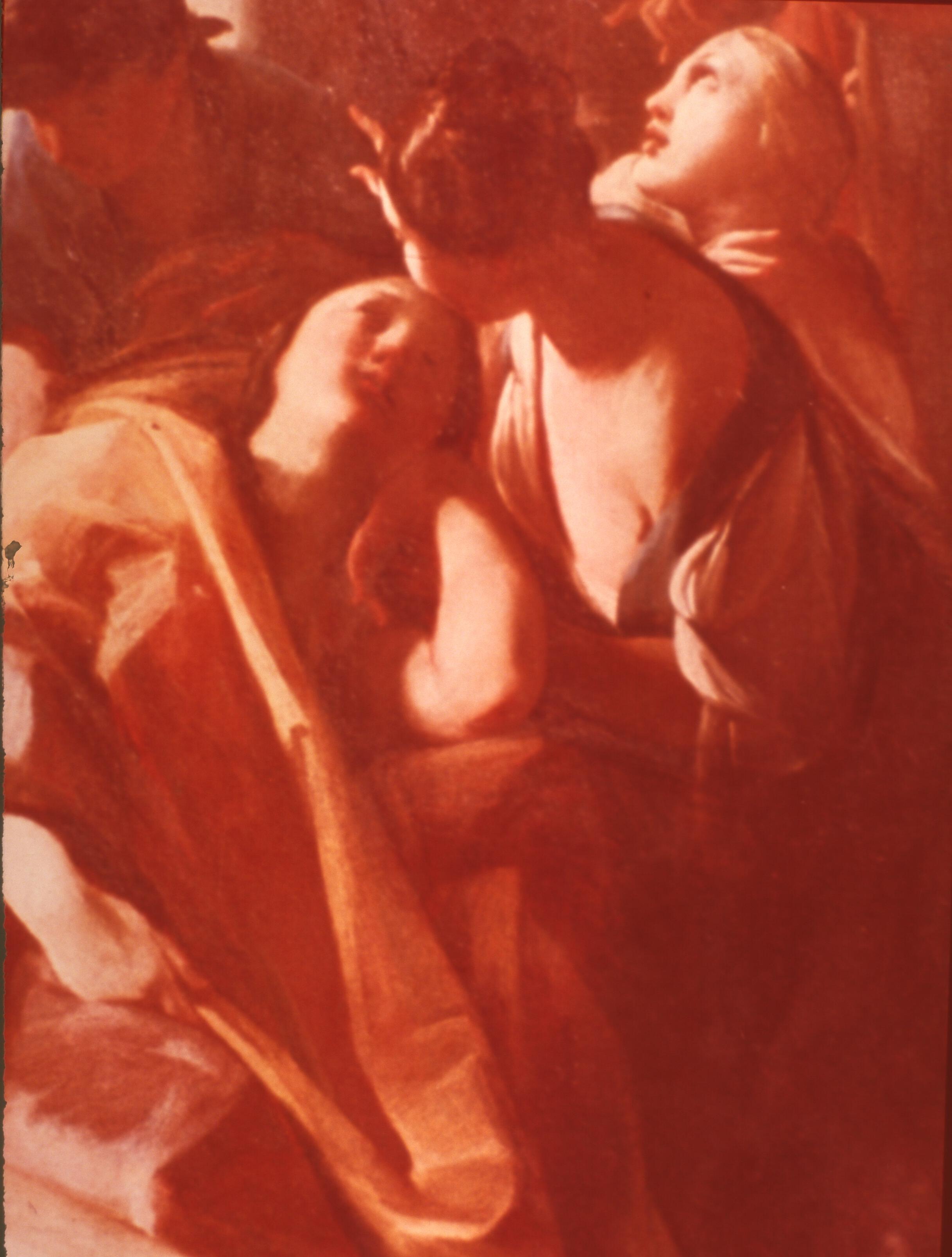

Finally, I give you one example of the art of Piazzetta (fig. 12), a picture done for the church of the oddly named Santo Stae in Venice in the early 1720s (the size once again is five and a half feet by four and a half). It shows St James being dragged to his execution—the subject of that dramatic fresco by Mantegna that we looked at in the first of these six lectures. The palette is limited to browns and yellows; it is dramatically lit from above, with splashes of light and patches of deep shadow; and it shows us violence, in extreme close-up and with anatomical exactitude, done by and done to relatively unidealised members of the working-class—proving that Piazzetta was seeking inspiration in the art of Caravaggio and his followers a hundred years earlier.

This canvas forms part of a set of twelve, each depicting one of the apostles, which were commissioned from a number of artists, including Ricci, Pellegrini, and the young Tiepolo—who was by then about 26 years old. Just how far Tiepolo could assimilate his style to that of Piazzetta is evident from his Martyrdom of Saint Bartholomew (fig. 13), even though I only have a black-and-white image:

There is the same low view-point; the same use of close-ups, the same physical types; the figures being unbearably close to the picture plane (as you can see in the feet, or in Bartholomew’s extended hand, or the executioner’s huge fist). And notice not only the violent contrasts of light and shade, but the differing anatomical treatment in the arms of the executioner—very detailed—and in the pale and more idealised body of the saint, who is about to be flayed alive.

We have a good many paintings from the first decade of Tiepolo’s career—that is, from 1716 to 1726, the year when he went to Udine—and they contain quite a few surprises if you only know his later works, as well as a number of elements that will help us to understand our cycle.

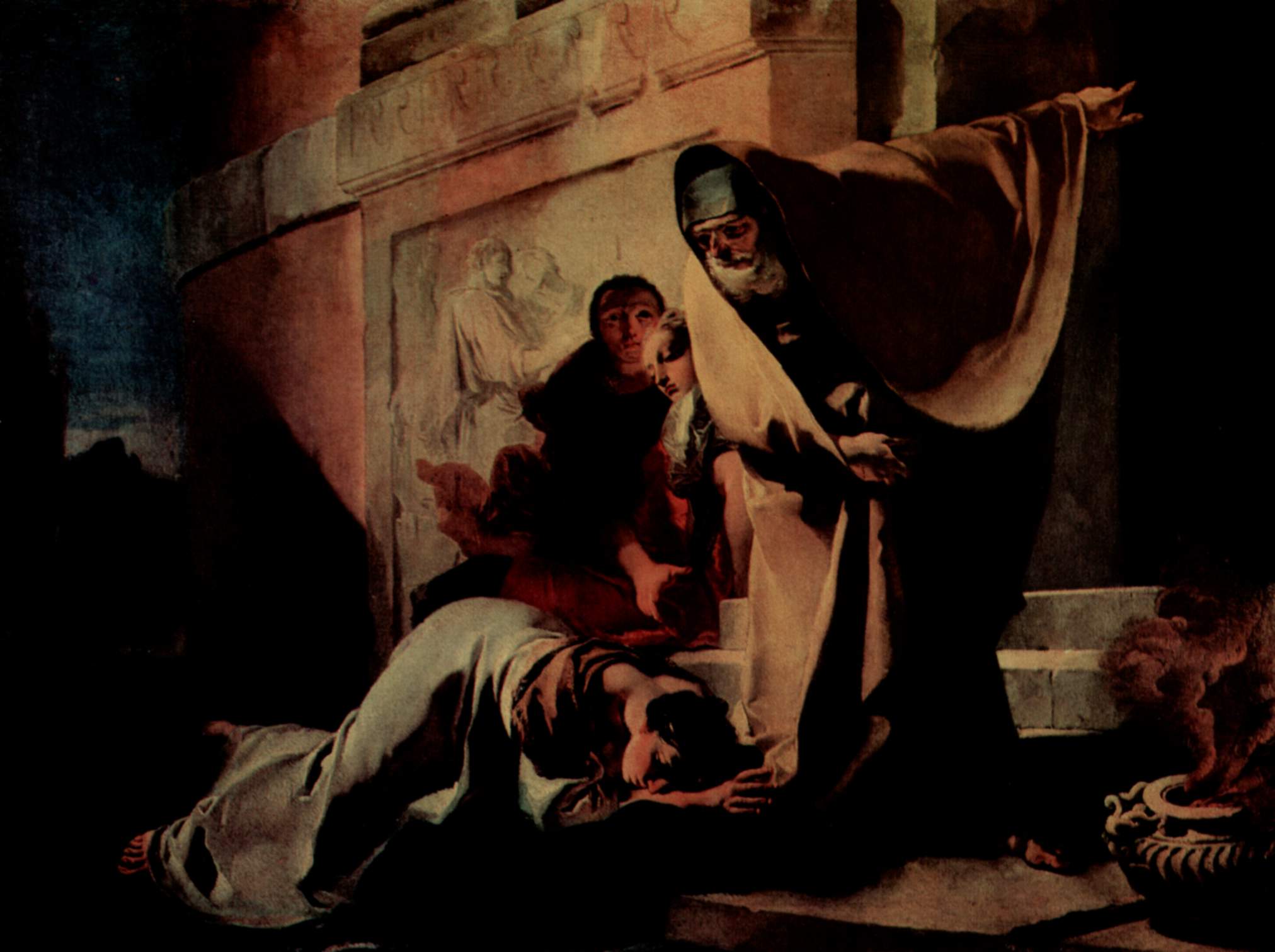

Fig. 14 is a little oil-painting, three and a half feet by four and a half, done in either 1717 or 1719 (the date is hard to read), showing a bearded patriarch, who is bending forward over the figure of a prostrate girl, and clearly indicating with his left arm that she is in disgrace and that she must go. It may well be that he is Abraham and she Hagar, the Egyptian slave-girl, whom we shall meet in Udine. Abraham took her as his concubine (at the insistence of his wife Sarah, when she believed that she would be barren forever), in order that Hagar should bear him a son. Inevitably, Sarah became jealous, causing Hagar to run away into the wilderness a first time (before her son, Ishmael, was born, as recorded in Genesis, Chapter 16). Then, after the birth of Sarah’s own son, Isaac, Sarah insisted that Abraham ‘should cast out this slave-woman with her son’; a command that was ‘very displeasing to Abraham’.

Nevertheless, we read: ‘he rose early in the morning, took bread and a skin of water, and gave it to Hagar, and sent her away, in the wilderness of Beersheba’. (Genesis 21, 9–14).

There are several objections to this identification of the scene, but I have reminded you in some detail of the story at this point, partly because we shall meet it again later, and because the proposed title does help us to understand the reluctance and concern of the patriarch (evident in his bowed head and in his expression). It also helps us to enter into the sombre mood, so powerfully created by the dark shadows to the left and the right, and by the contrast between darkness (the darkness of banishment) and dawn—the supernatural light from above making the bas-reliefs on the monument glow with an orange light, and highlighting the recumbent body of Hagar (if she it is).

RIGHT [FIXME: slide missing, no placeholder; original in Pinacoteca di Brera, Milan, if this helps find it among slides]

It is the palette that is so remarkable too in the even smaller oil sketch (fig. 14a, original in Pinacoteca di Brera, Milan), just eighteen inches by fifteen, done in about 1725, showing the Temptation of St Anthony in the Desert. There are no ‘creepy-crawly’ things of the sort you find in earlier versions of the subject: just a brown and ochre sky, an outcrop of quartz which is the colour of road-side snow after a thaw, and three trunks eerily lit—Tiepolo was always fascinated by the texture of bark in trees of the pine family, and by their short or broken lower branches.

The contrast in this painting is between the standing figure of the naked woman, ‘snooty’ but desirable, in conversation with her bat-winged, sharp-nailed pimp, and the bearded patriarch who is down on his knees, shielding his eyes with his huge book from the brightness of her flesh as he stumbles towards us—in a nice inversion of the role of the sexes, when compared with Abraham and Hagar.

In fig. 15 we have one last example of the early Tiepolo—again about 1725, again very small (20 inches by 26), and again in oils. This time, though, we have a contrast of colours within the picture, and an element of playfulness and wit that is going to be very characteristic of the frescos at Udine.

On the left (in colours that remind me very much of Ricci), we have a light blue sky, a creamy segment of a classical wall (very Veronese), a marble statue of Hercules, and a classical, laurel-wreathed conqueror, picked out by a bright splash of red for his robe (very Ricci again). He is Alexander the Great, and she is the Imperial mistress, Campaspe, having her portrait painted in an uncomfortable, but very ‘revealing’ pose (I think the aide-de-camp is plucking the dress just a little further off her breast).

To the right, we see the interior of the artist’s studio, the pilasters being made from a dark, volcanic rock, where there are some very dark green canvasses, half finished (the nearer one showing Moses and the Brazen Serpent). The artist—in contemporary clothes—is seen at work on the portrait, his brush poised between very elongated fingers, his head and eyes screwed right round in frank admiration as he tries to capture and to memorise the soft fullness of Campaspe’s breast, before setting it down on his canvas (cf. detail in fig. 16).

He is Apelles, the greatest painter of antiquity, who, according to the story, fell in love with Campaspe as he painted her and became her lover—with Alexander’s gracious consent—but he is also a self-portrait of Tiepolo, in his mid-twenties, not afraid to laugh at his own ‘pop-eyes’ and his own prominent nose, or at the drollness of his hypnotised expression. Hence we have here a combination of the historical and the modern, and of the classical and the Old Testament; a contrast between the palettes of Ricci and Piazzetta; a nod in the direction of Veronese; a chaste sexuality; and more than a gleam of humour –these being the elements that we shall find assembled in another compound at Udine.

We have had a look at eighteenth-century Venice; at Venetian painting in the 1710s and 1720s; and at four of Tiepolo’s canvasses done in the first decade of his career, before 1726. Now it is time to have a look at the city of Udine, and the building where this lecture’s frescos are to be found.

Looking to the north from the same building (fig. 20), you find two more landmarks—the portico or loggia of St John, and, behind that, a huge palace on the small hill where the medieval castle used to be, both buildings being virtually unchanged since the sixteenth century, as you can confirm in the detail (fig. 21) from a painting by Palma the Younger:

Fig. 23 is a photograph of the cathedral, in which Tiepolo did his first work for the city, frescoing a little chapel with some charming angels floating in the clouds (fig. 24), singing—and dropping their music. We should note them carefully, because angels are going to be as important as patriarchs in our cycle.

Who, or what, you may well ask, was the Patriarch of Aquileia? In Roman times, Aquileia was an important port on the Adriatic (cf. the map in fig. 28, where it is marked with a green arrow); and in the fourth century it became the seat of a ‘Patriarchate’ which could bear comparison with those of Antioch or Jerusalem—or with what was then the mere ‘Bishopric’ of Rome.

With the passing of time, the port silted up, the city declined, and the Patriarch moved his actual seat inland—first to Cividale, in the eighth century, and then to Udine in the thirteenth, where he occupied the castle in the centre of the town and ruled the area of modern Venezia-Giulia as a feudal overlord, just like the great feudal archbishops in medieval Germany.

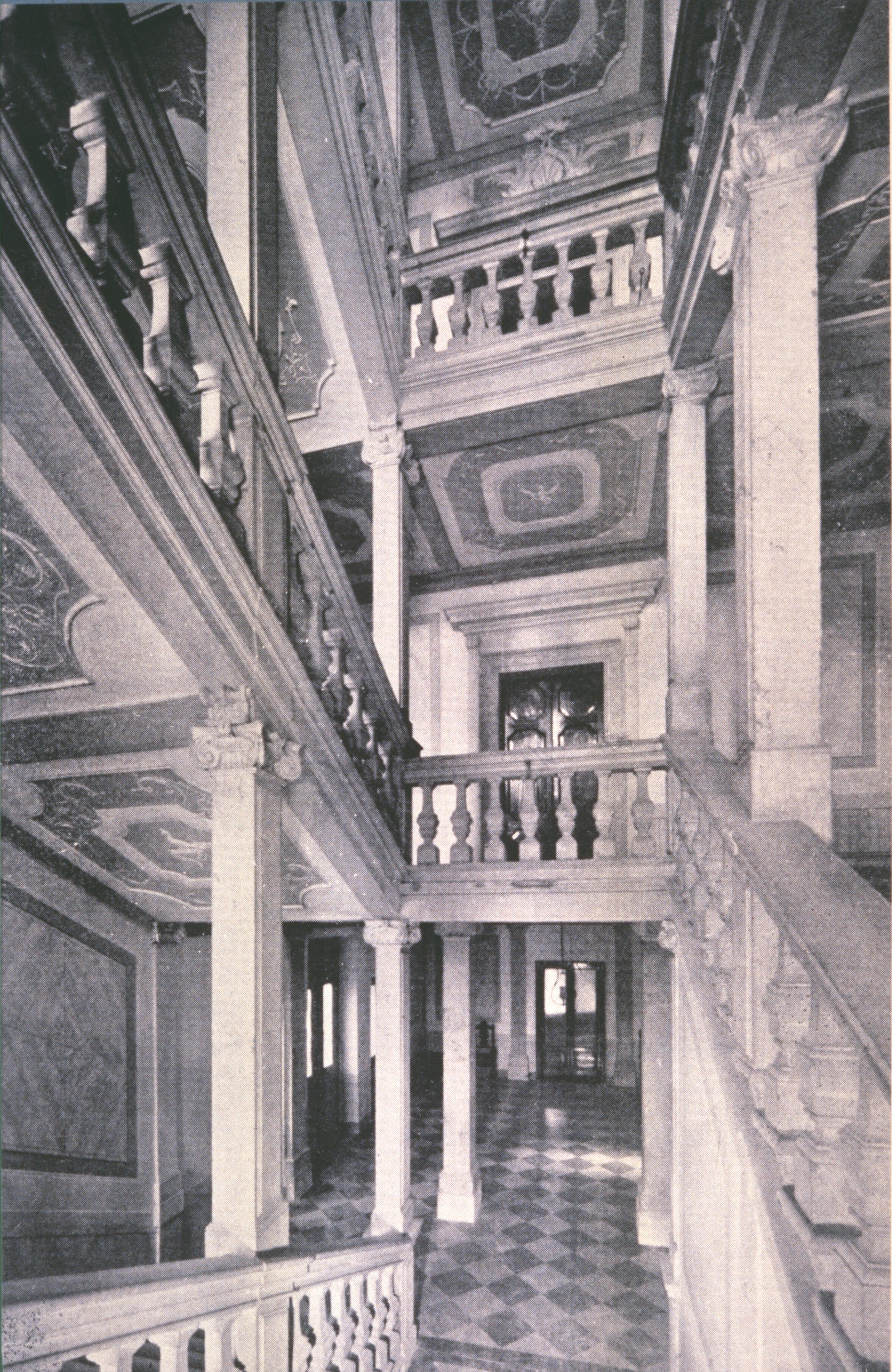

In 1420, however, the whole area was ‘annexed’ by the Republic of Venice. The Patriarch lost his temporal or political power; he was not allowed to reside in the city, in case he became the focus of local dissent; and he was appointed from one of the major noble families in Venice (you may recall that Daniele Barbaro, last lecture’s patron, was Patriarch-Elect of Aquileia, although he never took up that office). The religious prestige and the political influence of this ancient Patriarchate survived, however, and we know that in the first half of the eighteenth century both the Emperor of Austria and the Pope were doing their utmost to have the institution and its prerogatives suppressed. It is against this background that we have to understand the efforts of patriarchs from the Grimani family and the Dolfin family, who refashioned their curia on the site that concerns us until, by 1725, it had become the imposing edifice in fig. 26.

I hope I have told you just enough for you to understand that the decision to have two of the major public rooms decorated with frescos by an up-and-coming artist, Tiepolo, as well as the choice of the subject matter of the frescos, was part of a power struggle and a battle for men’s minds.

He is Michael, his wings and costume light-blue, armed with a shield and a cork-screw like sword. He is swooping down on a group of four rebel angels (already demonised with bat-wings and corkscrew tails) to cast them down from heaven into the ‘pit’. The most striking figure, isolated, presumably intended for Lucifer, is shown in the most difficult foreshortening—his left arm projecting beyond the frame, and actually modelled, in plaster, in the round.

This is among the earliest of scores of ceiling frescos showing swooping or soaring figures for which Tiepolo is probably best known; and, politically, it is probably meant to be a warning of the fate that will befall those upstarts who dare to menace an ancient Patriarchate.

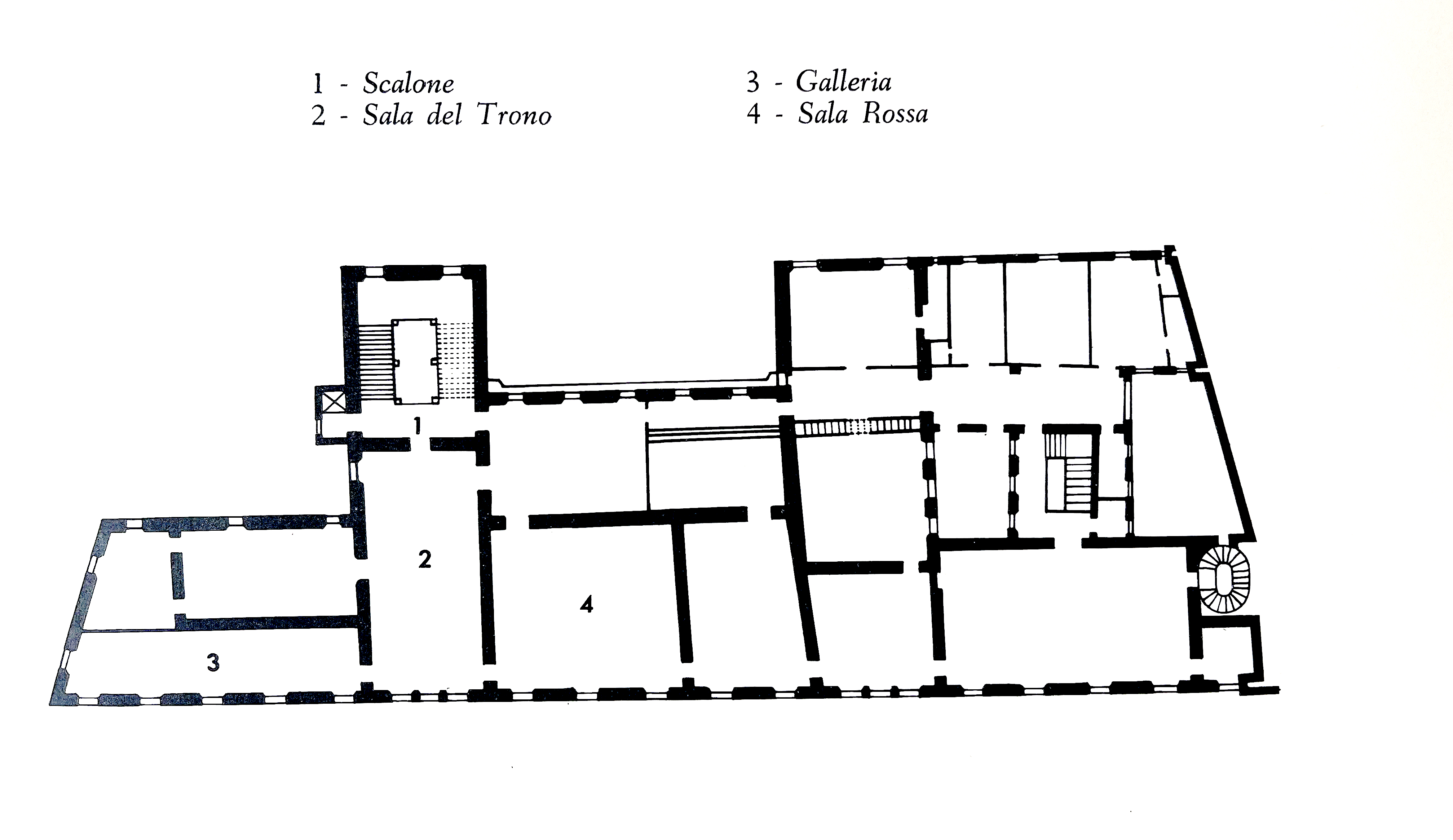

We now go on climbing up to the first floor, the piano nobile, which is laid out as you see in the plan in fig. 31—the various irregularities reminding you that the uniform façade of the building conceals what were many separate accretions around a core, on an awkwardly shaped, inner-city site. The room that interests us is marked with the number 3. It is the so-called ‘Gallery’, not quite symmetrical, the outer wall being twenty-two of my paces, and the inner only twenty and a half, the width being five.

Our frescos are set in the most incredibly elegant Rococo plaster frames, the work of Tiepolo’s frequent collaborator, Colonna, none of them being rectangular in shape. They are laid out with three narratives on the ceiling (a large one in the centre, as you see, and two smaller, symmetrical ones at each end), and five narratives on the inner wall (a large one in the centre, again, flanked by two symmetrical ones in grisaille and gold—simulating bas-reliefs—with two other narratives in symmetrical frames at either end).

Between the grisailles and the outlying narratives, which are in full colour, there are simulated bronze statues of female figures, apparently in deep niches, representing women prophets mentioned in the Bible; and the scheme is completed by four more of these Biblical prophetesses, all duly labelled, between the windows on the street wall. I do not have any images of these six ladies, but in fig. 34 I show you a drawing which is a study for one of them, and gives you the general idea:

Quite how the prophetesses were meant to fit into the ‘argument’ of the Gallery is not perfectly clear. They include well-known names, like Deborah and Anna, and two complete obscurities; but perhaps they highlight the important role played by the Matriarchs in the Book of Genesis—Sarah, Rebecca, Rachel—or by the ‘Mary’s’ in the Gospels.

The reasons behind the choice of the narratives, on the other hand, are perfectly straightforward. The Patriarch of Aquileia—at this time Dionisio Dolfin—would receive official visitors in this room (just as Lodovico Gonzaga received vistors in his Painted Chamber), and he wanted to link himself, and his political role, to the first patriarchs—Abraham, Isaac and Jacob—showing them as assisted or guided to success in moments of trial or crisis by ‘messengers’ from heaven—‘angeloi’ or ‘angeli’—exactly as the present patriarch hoped to receive divine aid in his defence of the prerogatives of the Patriarchate.

The main incongruity is that Tiepolo and Colonna were to treat the subjects in a light-hearted way, in those curvilinear frames, in bright colours, and with a good deal of innocent charm and humour. The narrative sequence does not read simply from left to right, nor from top to bottom, because of the different sizes of the frames to be filled and the need to achieve pictorial symmetry. Thus I will dodge about the inner wall and the ceiling, showing the frescos and telling you the story in the order in which they occur in the Book of Genesis.

The first episode in the Bible lies on the extreme right of the inner wall, and is therefore the first you meet on entering the room:

You see it in fig. 35, shorn of its relatively simple frame (which actually opens out a little to produce lobes at the top, as you will see in the paired scene in a moment), and is about thirteen feet high by seven and a half. The kneeling Patriarch is Abraham (cf. detail in fig. 36), now aged 99, married to Sarah, now aged 90, in a childless marriage.

The episode is narrated in Genesis, Chapter 18; but you cannot really understand the force of the story unless you realise that the couple were first introduced at the end of Chapter 11 (when Abraham was already 75), and that the Lord has brought them out of Ur of the Chaldees, through Egypt, to a place called Mamre—not far from Sodom and Gomorah, where their nephew Lot has gone to live—promising them, time and time again, that they shall have, even at their age, a multitude of descendants who shall be ‘as numberless as the stars in the sky’, and shall dwell in the land of Canaan, which is where Abraham himself is travelling.

Sarah is particularly sceptical about the repeated promise, hence her solution—described in Chapter 16—of persuading her husband to father a son with the Egyptian slave-girl, Hagar (which happened when Abraham was 86!). And in Chapter 17, which takes place fully 13 years later, Abraham falls on his face and laughs when the Lord tells him that his wife is about to conceive a son. This is why God insists that the boy should be called Isaac, meaning ‘he who laughs’.

Anyway, we have reached Chapter 18, which begins like this: ‘The Lord appeared to Abraham by the oaks of Mamre in the heat of the day. He lifted up his eyes, and beheld three men stood in front of him’. (There will be repeated shifts in the narrative, by the way, from one Lord to three men: and Christian theologians were to interpret the shifts as a sign that the three Persons of the Trinity had appeared to Abraham: Christian artists, however, always showed the three men as winged angels—as ‘messengers’.)

‘When [Abraham] saw them, he ran to meet them, and bowed himself to the earth’. He then prevailed upon them to rest under the tree, and to take refreshment—including cakes—which were hastily baked by Sarah. In following the action in the fresco, you will have noticed the tree (although it is more like a pine than an oak, and it does not offer much shade); and you will also have registered that the buildings are suspiciously like farms in the Veneto. But notice how Semitic, and how old Abraham is; and how he turns his head and closes his eyes (cf. detail in fig. 36), unable to endure the radiance of the angels, while holding up his huge hands in entreaty.

As for the angels—well, you must forget Rilke’s famous assertion that ‘each and every angel is fearful’, and enjoy the affectionate way the central angel is embracing his young companions, or admire the way in which their loose-fitting, theatrical costumes are caught at the waist to produce complex folds and to expose their legs, two of them having very short, bulging calves.

Enjoy the colours too: they are standing on a white-pink cumulus, against a convenient, grey-bluey-pink nimbus; meanwhile the white robe and wings of the one in the middle contrast with the light-green, and with the particular combination of blue and brown that, for me at least, is always Tiepolo’s greatest chromatic glory.

The Biblical story continues without a break at the far end of the gallery on the same inner wall, beyond the last simulated statue. This time (fig. 38), the slide-maker has had the good sense to include the plaster moulding, which does so much to put you in the right frame of mind, and to help you to accept the light-hearted treatment of the subject:

Sarah was eavesdropping, and she overheard the angels say that she should have a son in the spring, although the menopause was long behind her (or, if you prefer the more dignified words of the Bible, ‘it having ceased to be with her after the manner of women’). And ‘she laughed to herself, saying: “after we have grown old, shall I have pleasure?”’—only to deny having laughed immediately afterwards, when the Lord reproached her (at this point in the narrative, the three men have indeed become the singular Lord) with the words: “Is anything too hard for the Lord?”.

Hence in our image the three angels have become the one Lord, and the angel is clearly the central one of the first three (cf. detail in fig. 39), having the same set of his head on the long neck, the same wing feathers, and the same rather shapely thigh, even though he has rapidly changed costume and is now wearing a yellow robe, cast negligently over a brocaded tunic with a blue hem.

The Bible speaks of a ‘tent’, but Tiepolo gives us an improvised wooden shelter, with a nail for the shawl and for the water-bottle; a shelter made of rough planks of pine wood (look at the knots and the grain), cut from a tree like the one which helps to support the shack. Do enjoy the colour here, the texture of the bark, the splits in it, and the fungus growing on it.

Sarah (cf. detail in fig. 40) kneels like Mary in an Annunciation (and the composition is very like one of Tiepolo’s drawings for an Annunciation in reverse), but she is treated with that humour and that hint of caricature which we are coming to expect, as somewhere between laughing, and denying having laughed; between hiding and being discovered.

She is wrinkled, scrawny necked, and she has just two teeth; but she is dressed like a ‘grande dame’—so take in the striped sleeves of her chemise, the blue of her dress (highlighted in yellow), the ochre of her robe, and the superb whale-boned collar (there is a delightful double anachronism in her costume, which is neither vaguely biblical, nor eighteenth-century, but copied from sixteenth-century fashions in the paintings of Paolo Veronese).

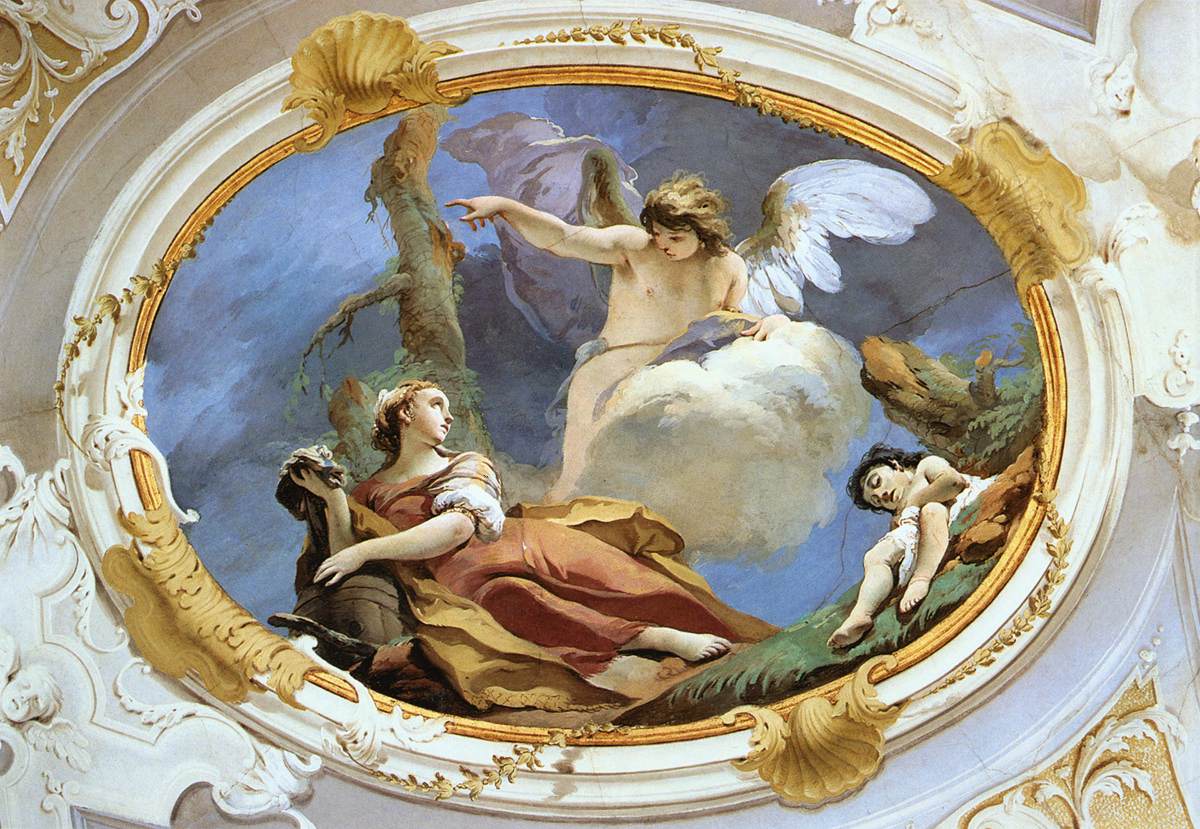

Chapters 19 and 20 deal with Sodom and Gomorrah, and with Sarah’s abduction by Abimelech. Then, in Chapter 21, Isaac, ‘he who laughs’, is born to the parents, who had each laughed at the idea of their having children at their advanced age. No sooner is Isaac weaned, however, than Sarah grows jealous of Hagar and her son Ishmael; and she insists that Abraham ‘cast them both out into the Wilderness of Beersheba, with bread and a skin of water’. But the Lord is a good deal more merciful than Sarah, as we discover in the next scene, which lies on the ceiling near the door, in a fairly elaborate oval moulding (fig. 41).

In accordance with the text of Genesis, she is represented as ‘a good way off’ from the exhausted Ishmael, whom she has ‘cast off under a bush’ (or a pine-stump), saying: “Let me not look at the death of the child”. But the Lord hears the voice of the boy crying, and the angel of God called to Hagar from Heaven, saying: “Fear not, arise, lift the lad, hold him fast with your hand, for I shall make him a great nation”. Then God opened her eyes, and she saw a well, and she filled the skin with water’. You can supply the happy ending to the story as well, if you now imagine the barrel to be full.

The subject, then, is an angel coming to the rescue; and although the picture is fairly ‘routine’ Tiepolo, I would like you to look at the way his thigh, or his hand, ‘melts’ into the white cloud; or how his right wing ‘dissolves’ into the cloak, and then the cloak ‘merges’ into the sky, for this will give me the chance to quote some lines from Alexander Pope’s Rape of the Lock, which seem to me to be describing an archetypical Tiepolo ceiling, though the poem was written in the year 1714, before Tiepolo had even begun work:

He summons straight his Denizens of air;

The lucid squadrons round the sails repair;

…

Some to the sun their insect-wings unfold,

Waft on the breeze, or sink in clouds of gold:

Transparent forms, too fine for mortal sight,

Their fluid bodies half dissolv’d in light.

Loose to the wind their airy garments flew,

Thin glitt’ring textures of the filmy dew,

Dipt in the richest tincture of the skies,

Where light disports in ever-mingling dyes;

While ev’ry beam new transient colours flings,

Colours that change whene’er they wave their wings.

We move along now to the central fresco on the ceiling, whose elaborate moulding is at least suggested by the first version of the image in fig. 43 above (the moulding itself does put in a brief appearance in the detail of the main action below it).

It is bigger than the other ceiling frescos (thirteen feet by sixteen and a half), and it represents the single most important episode in the relationship between the father and son, Abraham and Isaac, when the Lord puts Abraham ‘to the test’, saying (at Genesis 22): “Take your son, your only son Isaac, whom you love, and offer him as a burnt sacrifice”.

As almost always in Christian art, we see the climactic moment in the story, with Isaac ‘bound on the altar, upon the wood’; and, as so often, Tiepolo suggests that the wood is laid to form a cross, because the episode was taken to be a prefiguration of the Crucifixion. Abraham had ‘put forth his hand, and taken the knife to slay his son’, but the Angel of the Lord called to him from Heaven, commanding him: “Do not lay your hand upon the lad, for now I know you fear God, seeing you have not withheld your son, your only son, from me”. You will remember that Abraham then catches sight of a ram, ‘caught in a thicket by his horns’, and he offers the ram instead.

So, there is faithfulness to the narrative—the knife, the altar, the wood, Isaac, the ram—but nothing sublime or tragic: simply an exploitation of the ceiling to paint a lovely ‘denizen of air’, ‘wafting on the breeze’, with ‘airy garments’ flying ‘loose to the wind’, and ‘light’ ‘disporting in ever mingling dyes’.

At this point you should look back to fig. 33, to remind yourself of the setting: the photograph there is taken looking towards the door, with Sarah’s angel and a prophetess on the wall, and, on the ceiling, little Ishmael with Abraham and Isaac. Now we must continue along the ceiling to the end near the door, where we find the first of four episodes dealing with Isaac’s son Jacob, the younger of the twins, who had fought with his elder twin Esau (the ‘hunter’ and ‘hairy man’) even while he was in the womb (the story is told in Genesis, Chapter 25).

Tiepolo was not required to paint the scandalous stories of how Jacob persuaded Esau to sell his birthright, and how he cheated Esau of his father’s blessing; but he takes up the story immediately after that event, when Jacob has set off on a journey to his uncle, Laban (notice the staff and his water-bottle), with a view to marrying one of his cousins.

‘He came to a certain place and he stayed there that night because the sun had set. Taking out one of the stones, he put it under his head, and he laid down in that place to sleep. And he dreamt that there was a ladder set upon the earth, and the top of it reached to Heaven, and, behold, the angels of God were ascending and descending on it’. (Genesis 28, 10–12).

At this point the Lord appeared and renewed the promises made to his father and grandfather—Abraham and Isaac—about the number and the glory of his descendants. But in this case, I scarcely need to do more than remind you that it is a ceiling painting, and that the ladder really does seem to climb up and up, and perhaps remind you too of the relevant lines from Alexander Pope:

‘Transparent forms, too fine for mortal sight,

Their fluid bodies half dissolv’d in light.

…

Thin glitt’ring textures of the filmy dew,

Dipt in the richest tincture of the skies’.

Laban was a pretty tough customer—uncle or no uncle–and he made Jacob serve for a total of 14 years before he let him marry the cousin he loved, Rachel, having first fobbed him off with the ‘rheumy-eyed’ elder sister, Leah. So perhaps Laban got no more than his due in the next scene (figs. 45, 46). This occupies the place of glory in the centre of the gallery, and is thirteen feet high by sixteen and a half across:

The story is told in Genesis, Chapter 31. Having married the two sisters, Leah and Rachel, Jacob has struck a bargain with his father-in-law by which he would become the owner of any sheep and goats to be born with a speckled fleece. He has also become ‘exceedingly rich’ (30, 43), because, thanks to a little ‘sympathetic magic’, and the help of the Lord, all the lambs and kids were born ‘striped, spotted and mottled’. That summer, he waited for Laban to go off for sheep-shearing, then (quoting from Chapter 31, verse 17):

‘Jacob arose, and set his sons and his wives on camels; and he drove away all his cattle, and all his livestock which he had gained to go to the land of Canaan to his father Isaac’.

Laban did not discover their flight for three whole days, and he then took a week to catch them up (which happened immediately before the episode shown here). But before I remind you of what father is saying to his daughter, let us take in the characters and the setting. Against the simplest sky and clouds—and just a hazy glimpse of the Alps as seen from Udine, with a campanile in the foot-hills—we see, in the centre, two pines (which are Tiepolo’s way of reminding you that, like the earlier episodes, this takes place in the desert), and to the right of centre, two camels (or their heads) with two attendants.

On the left, you can see a suggestion of sheep and goats, and a cow which is being escorted by an affectionate and rather dreamy cow-herd, who is carrying his indispensable staff and water-bottle, while a tall maid-servant, carrying an even bigger water-jar, turns her shapely back towards us and gestures to unseen followers ‘off-stage’. On the right, the vast flap of a tent forms the ‘back-drop’ for the elder sister and first wife, Leah (cf. detail in fig. 47); she too has an amphora, and pyjama trousers underneath her ‘slatey’ dress.

She is surrounded by some of the seven children that she has already born to Jacob—one drying his eyes on her dress, and another clinging to her skirts (although he or she is really rather big to be frightened of such a soft-mouthed retriever), while a much older girl comforts a rather glum-looking Reuben.

The three characters in the centre (fig. 48) are Laban, every inch the patriarch, leaning forward, with puckered brow; Jacob, looking rather ‘sheepish’; and Rachel, with her first-born, Joseph, at her knee.

We must go back to Genesis to discover the precise cause of the confrontation. Laban is not only the ‘insulted’ father, reproaching his daughter and son-in-law for having simply run away; he is ‘the injured’ father who has discovered that his household gods have been stolen—his ‘idols’ or idola, which would have been sacred figurines, easily transportable by a nomadic community. We have in fact been told that it was Rachel who stole these ‘household gods’, without saying anything about the theft to her husband. He, all righteous innocence, has invited his father-in-law to search all his possessions; and Laban, having found nothing in Leah’s tent, comes to Rachel’s.

We pick the story up at Chapter 31, verse 34: ‘Now Rachel had taken the household gods and put them in the camel’s saddle, and sat upon them. Laban felt all about the tent, but did not find them. And she said to her father: “Let not my Lord be angry that I cannot rise before you, for the way of women is upon me”’—in the vernacular, ‘I have the curse’. And so the theft was not discovered.

The episode ends with the kind of uneasy settlement that follows a major family row; and Jacob will return to Canaan, after wrestling all night with an angel (the scene represented in simulated bas-relief, to the right of the central fresco, in fig. 49), and after being warily reconciled with his twin-brother Esau (which is the parallel scene, represented in bas-relief to the left).

I think we ought to end our visit, however, with a closer look at the principal actors in the main scene (fig. 50):

So, look at Laban’s expressive hands, emerging from the loose sleeves of his chemise under the brown doublet, with its shoulder-strap to support the sword; or at his sunburnt neck, and puckered brow, beneath the close fitting skull-cap above the flowing beard. Look closely too at Jacob’s puzzlement—but dawning understanding—and, if you focus on the pop-eyes staring out at us, and at the large shiny nose, you may be reminded of the painter Apelles in the 1725 work, and accept that this too is intended as a self-portrait of Tiepolo in his later twenties, he having married very early after much resistance from his future father-in-law.

If it is a self-portrait, then it seems intrinsically likely that Rachel is a portrait of his young wife Cecilia, sister of the painter Francesco Guardi; blonde and blue-eyed, pearls in her ears, pearls about her neck and in her hair, wearing the most ravishingly painted blue dress. She is in a sense prophetic, because if the two men make us think of the earlier Tiepolo, Rachel points forward to the later masterpieces—to a whole series of gorgeously dressed princesses and queens from the mythical Orient, each of them as clever and as calculating as Rachel, who always bring out the very best in Tiepolo.

FIXME: THE FOLLOWING PARAGRAPHS ARE A SAMPLE OF AN END-OF-COURSE THANK-YOU SPEECH, AND SERVE TO RECREATE THE CIRCUMSTANCES IN WHICH THE VARIOUS LECTURES COURSES ON ITALIAN NARRATIVE ART WERE FIRST GIVEN, ON MONDAY EVENINGS IN THE MICHAELMAS TERM, AT 5 PM, IN THE BABBAGE LECTURE THEATRE ON THE NEW MUSEUM SITE.

Now to the thankyous. A series like this depends on the collaboration of a great many people, and I want to thank a few of them by name. First, then, our departmental secretary Jane Bagat, who has shouldered a great deal of extra work for many weeks with unfailing cheerfulness; then, the technicians from the Audio Visual Unit, Terry de Castro and John Skinner, for nursing the two projectors through the year (the projectors are ‘obsolete’, and yet far superior optically to anything currently on the market), and for standing by every week in case of a technical hitch. I would also like to thank every one here this evening as a ‘collectivity’. I do not know what combination of factors brings you so faithfully out week after week into the cold and the dark of a November evening, but I do know that the very special atmosphere depends a lot on the fact that you do keep coming and that the room is always packed: it is this atmosphere that makes the lectures such fun to give.

Today is rather a special day, in that we have some distinguished guests representing the University, and the Italian State. Italy is represented, first, by the new Director of The Italian Cultural Institute, Professor Francesco Villari. Professor Villari is a distinguished modern historian, coming from a family of famous historians, and I would like to thank him most warmly, on your behalf, for finding the time to come out to the provinces during his first busy days in the capital. I am sure I speak for you all in wishing him a very happy and fruitful tenure, and in expressing the hope that this will be the first of many visits to Cambridge in the coming months and years.

He has already begun to make history, because he is accompanied by a member of the government, Luigi Covatta, Undersecretary to the Ministry of the Arts and the Environment, who, as you may have read in The Times, is here in England on an important visit, which is part of a drive to change the Italian laws regulating the movements of works of art. If the mission succeeds, English museums will be able to have important works of Italian Art on long term loan, works that are currently languishing unseen in Italy’s overcrowded and understaffed museums. Perhaps we shall have a Michelangelo for the Fitzwilliam. So a warm welcome to him, too, and every augurio for success.

For their part, I hope that our Italian visitors will remember this evening for the warm welcome you have given, and that they will look on this occasion as a concrete example of the widespread and persistent love of Italy and Italian art which has been characteristic of this country since the Renaissance. Cambridge is a little different from other English towns of its size—‘un po’ particolare’. But the very varied audience here tonight is a wonderful cross section of all the people in the UK whom Professor Villari and Signor Covatta are doing their best to help. And in their inevitable moments of weariness and despair, I hope they may remember you all and take heart again.