Masaccio: St Peter (The Brancacci Chapel)

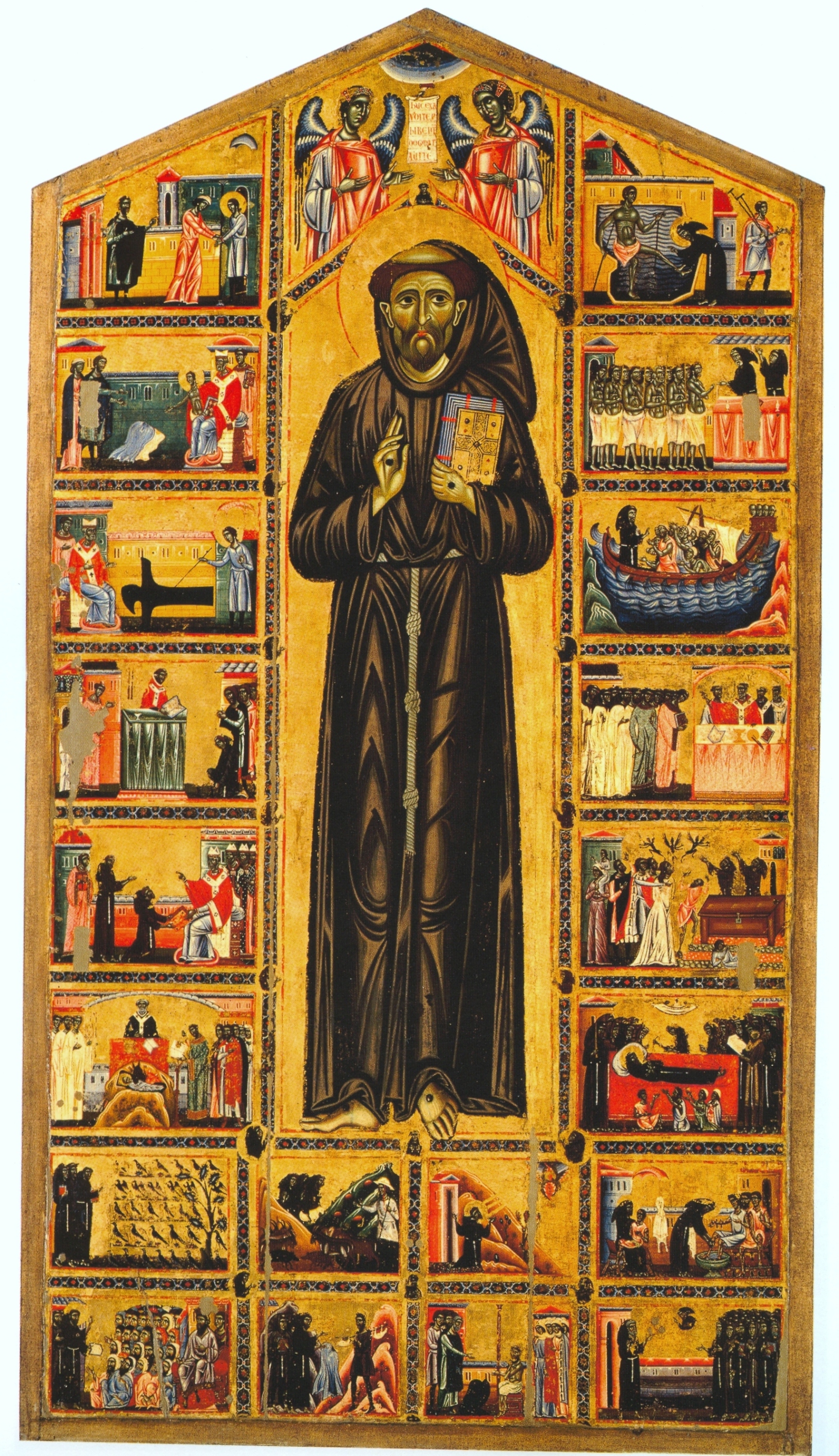

If you looked back to the second lecture of this series, you could revise the basic facts about the historical St Francis and the circumstances in which he founded his order of ‘Lesser Brothers’ in the year 1209 (confirmed by the Pope in 1221). You could also see scores of early depictions of Francisan Friars (to give them their more familiar name), in which they are wearing their distinctive religious habit, whose colour we would probably describe as dark brown.

(I dwell on the ambiguity of the colour because in later centuries they were referred to as Grey Friars.)

In that lecture, I also glanced at Francis’s close contemporary, the Spaniard, St Dominic (1170-1221) and the complementary religious order founded by him in 1216. Its proper name was, and still is, the ‘Order of Preachers’. But we usually refer to them, simply, as Dominicans; and they were often referred to as Black Friars, in allusion to the distinctive colour of their habit.

In the present lecture, we shall be turning our attention to a third order of Friars (whose rule was approved in 1226, the year of Francis’s death), the colour of whose habit led to their being called White Friars.

The White Friars claimed that their founder was none other than the biblical prophet Elijah, who, they said, had founded a community of hermits on Mount Carmel: hence they called themselves Carmelites. (In Italian, the mountain is called ‘Cármine’, and the adjective is ‘carmelitano’.)

They, too, spread rapidly throughout Europe (a Chapter-General in England is recorded as early as 1247).

They, too, came to Florence, in the 1260s, where they began to build a huge church.

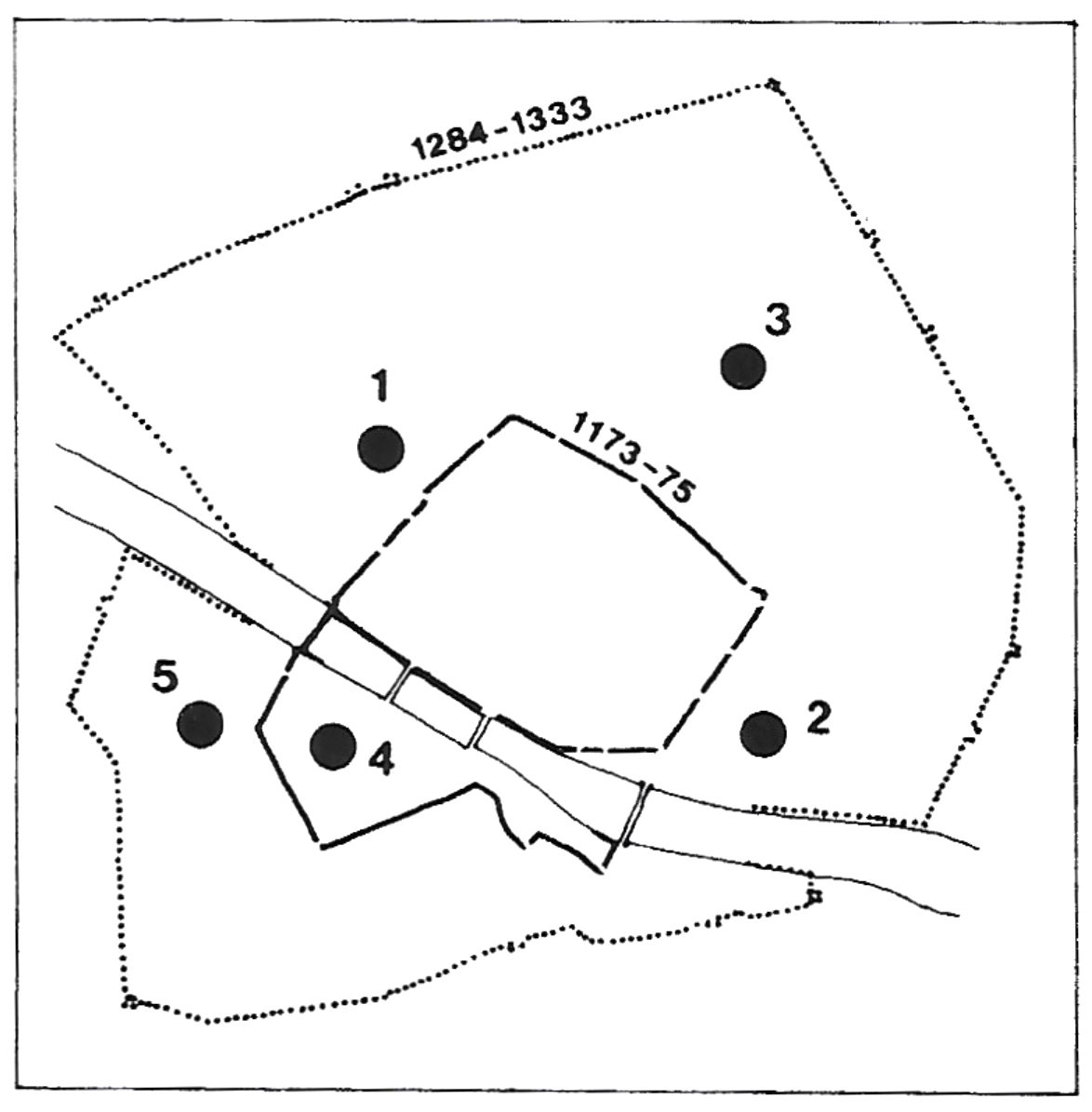

As the diagram shows, the historic centre of the city—which already contained 48 parish churches inside the ‘ancient circle’ of its walls—was now surrounded by the Dominicans in Santa Maria Novella (1) to the West, by the Franciscans in Santa Croce to the East (2), and the Carmelites in Santa Maria del Cármine on the other side of the Arno (5).

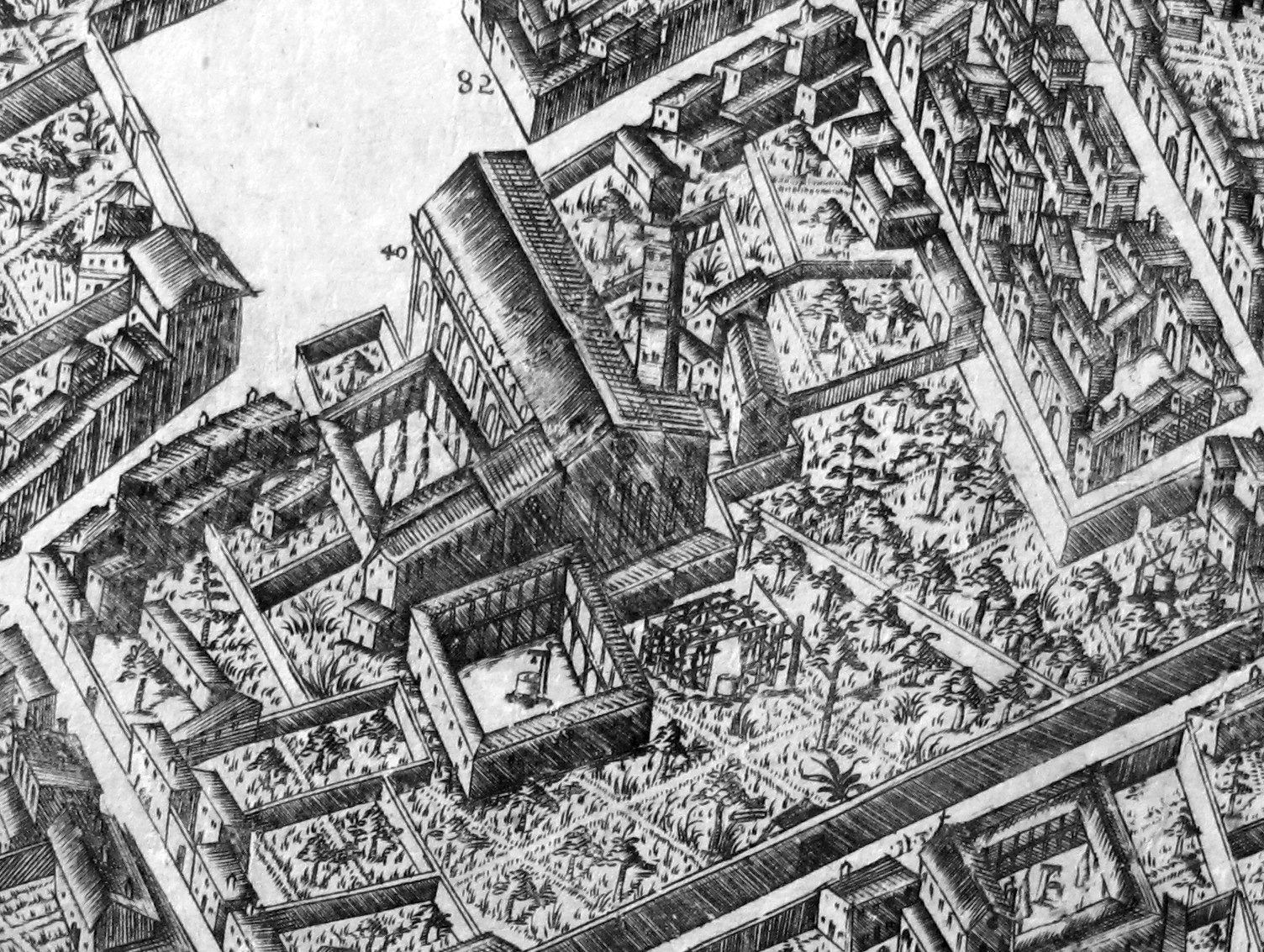

In this lecture we shall be concerned principally with the Carmelite church in Florence, built in the Gothic style, whose position and size you can make out in the details taken from the famous ‘Catena’ painting of the city.

(Building had begun in Dante’s lifetime, but it was not completed and consecrated until 1422. It was severely damaged by fire in the late 18th century and substantially re-built.)

In the mid 1420s, the Carmelites were looking for an artist to execute a fresco cycle in their Chapel which would be dedicated to events in the Life of St Peter after the crucifixion of Jesus.

They chose boldly, because the local painter (whom they had already employed in their convent at Pisa) was born as recently as 1401. He was still only twenty-six when he died in 1428.

His full name was Tommaso Giovanni di Mone (an abbreviation of Simone), which might be anglicised as ‘Thomas John Simonson’.

But he was always known simply as ‘Tommy’, or ‘Tompkin’—in Tuscan, Masaccio.

I will not say anything here about the social history of Florence in the late fourteenth century and the early years of the fifteenth. (I deal with the subject at some length in the first lecture in this series, The Flowering of Florence).

It will be enough to remind you that, despite a dramatic fall in population (mainly as a long-term result of the Black Death) from around 100,000 in 1300 to about 45,000 in 1400, Florence was still a powerful, self-governing Republic, well able to defend itself against its neighbours in three major wars during the first three decades of the new century.

We must, however, allow ourselves a couple of minutes to become familiar with the state of the visual arts at the beginning of the fifteenth century.

The art of painting had been essentially ‘marking time’ for seventy years and more.

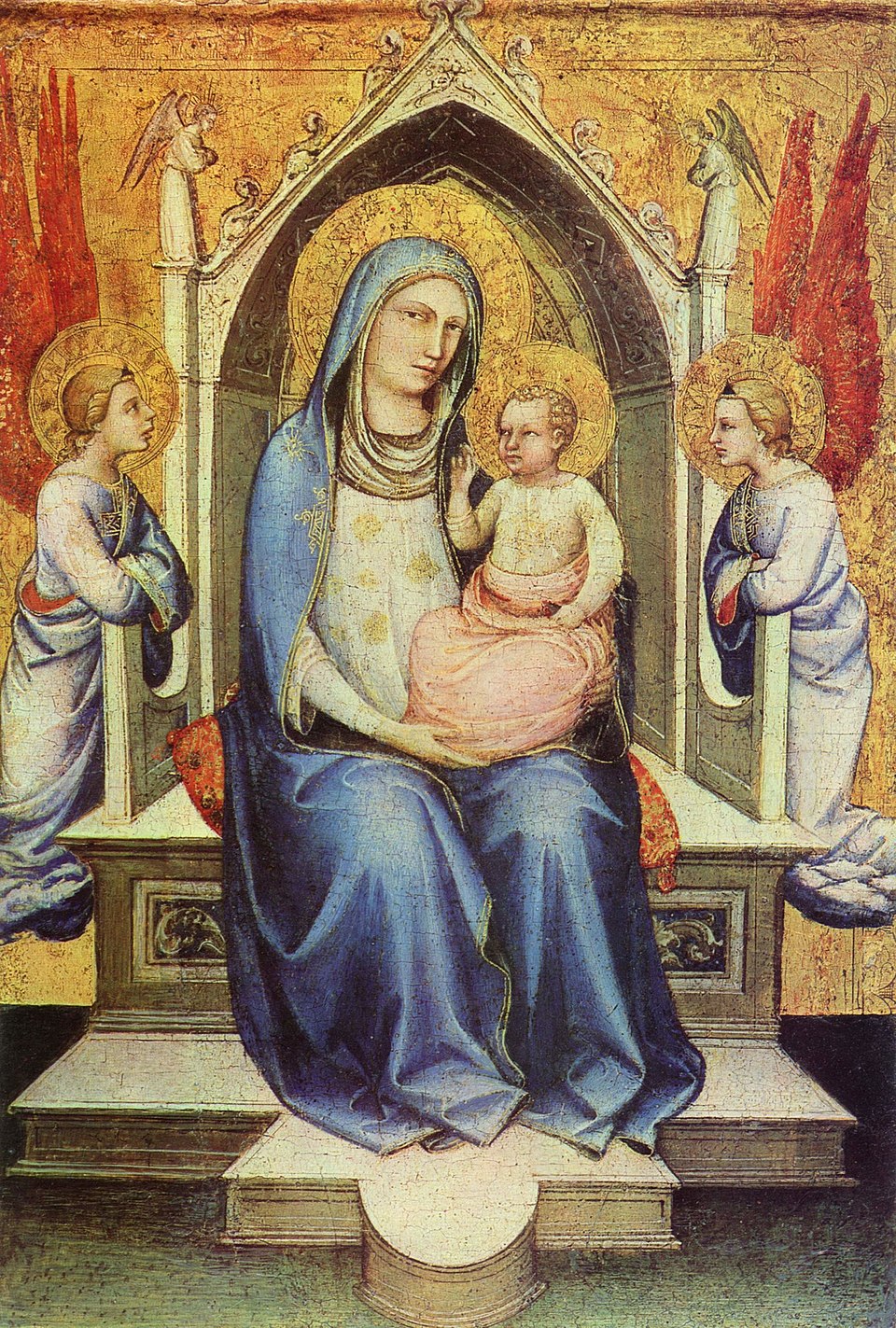

Two styles were competing for attention, which are charmingly blended in this small devotional image of the Virgin Enthroned (barely a foot high) dated to around 1400, which now hangs in the Fitzwilliam Museum at Cambridge. It is by Lorenzo Monaco (the master of Fra Angelico) who was born around 1370.

You can recognise at a glance the Tuscan tradition which can be traced back to the huge altarpiece by Giotto, now in the Uffizi, from ninety years earlier. (Notice particularly the construction of the throne and the figure of the Virgin.) But you should also be able to detect something of the lighter mood of the so-called International Gothic Style, which first appeared in Italy in the work of Simone Martini. (Notice the elegant ‘S-curves’ in the informal poses of the relaxed and smiling little angels in Lorenzo: they are kneeling on clouds and their wings are spread.)

Masaccio was clearly apprenticed to local masters who were working within these traditions, and it would have been from them that he learned the basic skills of his craft. But he was to be profoundly influenced in his late teens and early twenties by dramatic advances in the sister arts of sculpture and architecture.

The 1410s and 1420s were immensely important years in Florence for sculpture in marble, with several major artists at work on the exterior of the tower-like church of Orsanmichele in the heart of the city, carving the life-sized statues of the saints who stand in the niches on all four sides.

The greatest sculptor among them was Donatello (born 1386), whose work is exemplified here with a contemplative statue of St Mark (1413) and a heroic statue of St George (1417).

Focus for a moment on St George—so alert and so sensitive—because it is this statue, more than any other, which has come to epitomise the renewed admiration for the Classical past—and the new understanding of all aspects of that past—which characterise literature and philosophy as well as the visual arts in the new century.

Even more important, however, was the inspiration provided by an older man, Filippo Brunelleschi (born in 1378).

Brunelleschi had trained as a goldsmith and metal worker; and he was the the ‘runner-up’ in the competition held in 1401 for the twenty-four relief panels, cast in bronze, for the North door of the Baptistery (of which we shall take note in the next lecture).

But his fame now rests on his achievements as an engineer and architect.

He was the genius in charge of several major projects in Florence in the 1420s: the cupola for the Cathedral (Duomo), the Foundling Hospital (Ospedale degli Innocenti), the sacristy for the Church of San Lorenzo, and indeed the designs for San Lorenzo itself.

I show you here two images of the nave of this church to illustrate his creative rediscovery—based on a prolonged, first-hand study of Roman buildings in the city of Rome itself—of the ‘grammar’ of Classical architecture (clearly evident in the round arches and in the proportions of the columns), and also of the ‘idiom’ of Classical architecture, which is very evident in his faithful realisation of a three-part entablature (architrave, frieze, cornice) supported by a capital which has the volutes and the acanthus leaves of the Composite Order.

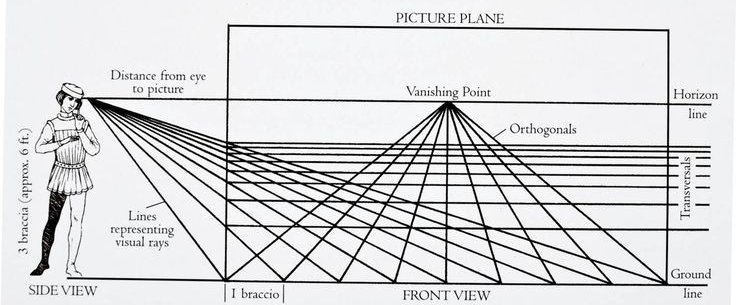

Brunelleschi and Donatello were friends; and it seems to have been these two—the architect and the sculptor—who made a decisive breakthrough in the study of perspective, a breakthrough which would be theorised and popularised in the mid-1430s by Leo Battista Alberti in his treatise on painting.

I include just one diagram here illustrating some of the main features in Alberti’s presentation of the easily learned geometrical laws at the heart of his ‘costruzione legittima’.

You do not need to understand or master them now; and I shall assume you are sufficiently familiar with such interrelated terms as ‘line of sight’, ‘viewpoint’ (outside the picture plane) determining the ‘vanishing point’ on the ‘horizon’ (within the picture) on which all the ‘orthogonals’ (lines parallel to the line of sight) will seem to converge, and which also determines the rate of ‘diminution’ of all lines at right angles to the line of sight. (Think of receding railway lines and the diminishing intervals between the sleepers).

But I ought to remind you of one vital consequence of the observance of geometrical laws in Alberti’s system of perspective.

There will now be a common scale, based on the height of an average man, for every object in the picture, with the result that buildings have to look big enough to contain the human beings, and that people in the picture will differ in size, not in proportion to their relative importance (as so often happens in medieval paintings), but in strict accordance with their presumed distance from the picture plane.

With this bare minimum of context, we can usefully spend a further moment or two to get our eye in by examining Masaccio’s first commission for the Carmelites, a now dismembered altar-piece for the convent at Pisa, of which the centre panel happens to be in our own National Gallery.

It illustrates simultaneously what Masaccio had been taught as an apprentice, what he had absorbed from Donatello’s sculpture and Brunelleschi’s buildings, and what he himself brought by way of genius and the close observation of directional light.

I show it together with that very famous altar piece by Giotto at which we glanced in relation to Lorenzo Monaco, so that you can pick up the debt to tradition and the innovations.

In both, you see a non-rectangular frame with a gold ground; and in both you see steps leading up to a throne on which Mary sits, her face in three-quarter profile, a mantle covering her right shoulder and head, holding Jesus on her left knee. On the steps there are two angels with flat, unforeshortened halos; and Mary also has a flat, but richly-tooled halo.

Giotto’s throne is clearly Gothic in its pointed arches and pinnacles, and the steps are inlaid with a typical Cosmatesque pattern of the kind you saw in the Upper Church at Assisi in the previous lecture.

Masaccio’s throne, by contrast, is self-consciously classical, apparently carved from the severe grey stone (‘pietra serena’), used by Brunelleschi in San Lorenzo, complete with two orders of classical columns (single below, double above), classical entablatures, classically-inspired rosettes on the base, and classical decorations on the step.

Giotto’s perspective certainly creates space—there is room for his angels to kneel, and room for the Madonna’s generous thighs—but the implied viewing point is far higher for the steps than it is for the underside of the arch; and the arch is not seen centrally, even though the wings of the throne are symmetrical and ‘fully frontal’.

Masaccio, by contrast, has placed his viewing height, and therefore his horizon, rather low, making it coincide with the level of the spectator’s eye in the chapel. The top of the narrow step (on which the angels are sitting) is revealed. The main step is seen almost flat. The seat and the base of the lower column, and all the rest of the throne, are foreshortened consistently from below.

Passing on to the figures, look first at the Christ child in Giotto, who is clothed, flat-haloed, and distinctly ‘volumetric’—but not particularly convincing anatomically. In Masaccio, he is naked, the halo is foreshortened, the body strongly sculpturesque: indeed, he recalls a classical ‘infant Hercules’.

Now, look at the foreground angels: in Giotto, they are kneeling, in profile, almost mirror-images of each other, modelled in light and dark tones in more or less the same way, even though one is on the left and the other is on the right.

In Masaccio, on the other hand—as you can see very clearly in the detail— the angels turn inwards, holding their lutes in different positions, and these are boldly foreshortened in order to insist on their three-dimensionality.

Yet the real innovation is that Masaccio’s angels are strongly and consistently lit from the upper left. The light catches one angel’s shoulder, the top of his arm and the lute, and the side of his outer knee; while it illuminates the other’s chest, the face of his lute, his inner arm, and the top of his inner knee.

If you look at the throne, you will see the direction of the light much better—it is clearly coming from an angle of about forty degrees from the left; it leaves a deep shadow, from the projecting side of the throne, and it throws a ‘cast shadow’ from the Virgin onto the brightly lit columns on the right.

In the Giotto, there are no cast shadows anywhere—and it is Masaccio’s close observation of what is called ‘incident’ light and of cast shadows, that makes all the difference in his modelling of the robe on Mary’s right side, and, of course, in the face and body of the child.

It is now high time we headed back to Florence and to the vast Carmelite Church on the south bank of the Arno.

Its position is clearly shown in what might be called a fifteenth-century ‘tourist map’ (in the upper image), which places South rather than North at the top.

In 1484, it looked like the splendid woodcut in the lower image.

I show you these rather than modern photographs, because the church suffered a disastrous fire in 1771, which badly affected the frescoes in our chapel and led to the demolition and rebuilding of everything except the chapel and the façade.

You must therefore try to visualise a huge Gothic church, not the rather soulless barn which stands there today.

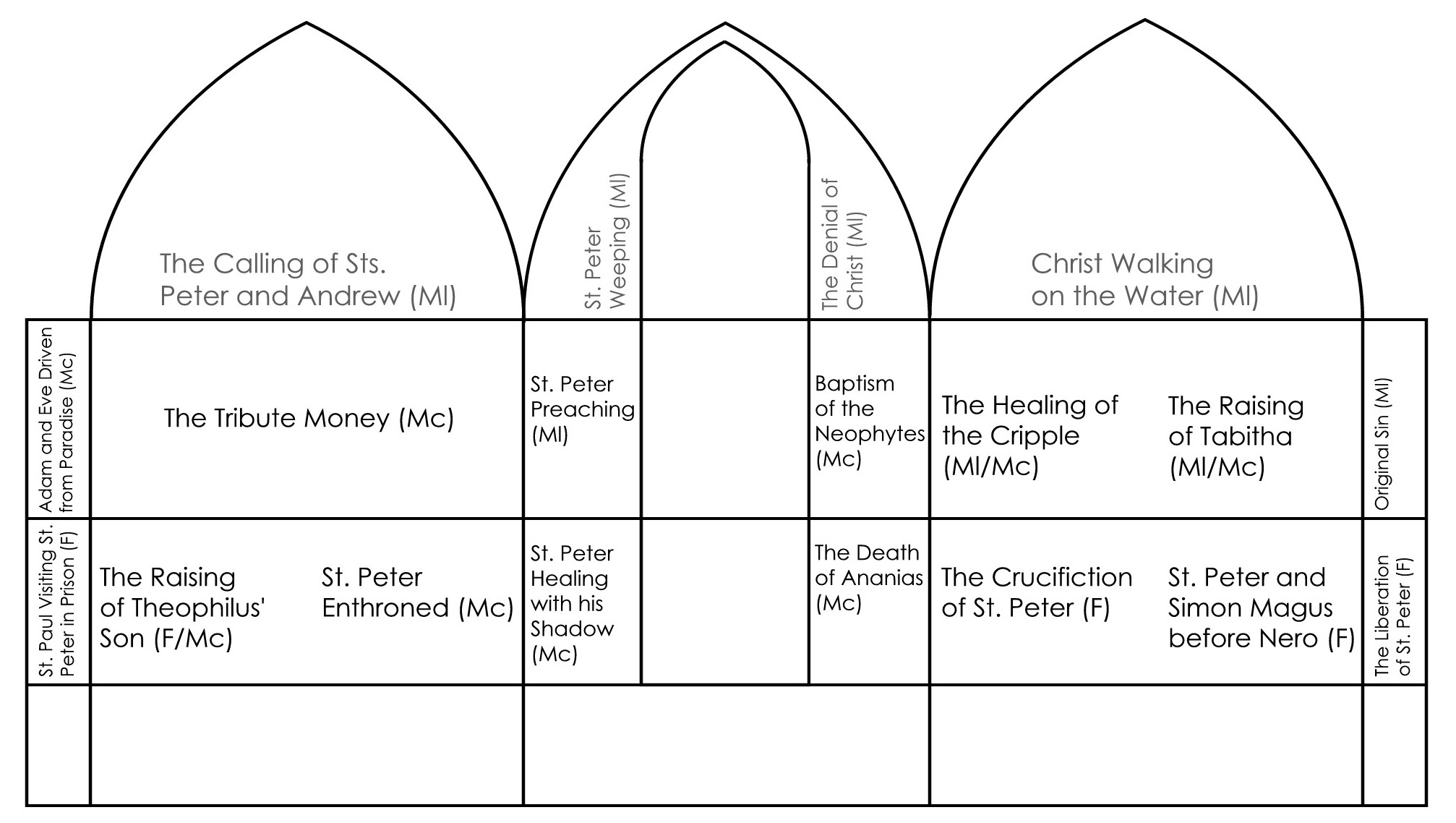

The fresco cycle on which the rest of this lecture will focus is located in a chapel on the South side of the church and occupies the three walls and the entry arch.

Notice the position of the window above the altar.

(The first photograph was taken fifty or sixty years ago, well before the painstaking restoration in the 1980s which has made the colours radiantly bright.)

The money for the decoration of the chapel was put up by a wealthy silk merchant, called Felice Brancacci, who lived in that Sixth of the city and was a prominent figure in Florentine politics.

The commission was assigned to a team which was headed by Masaccio and a slightly older man, called Masolino. (His name, too, is a diminutive of ‘Tommaso’ in Italian; so we have ‘Big Tom and Little Tom’.)

The two men had already collaborated on other commissions and were able to work together so closely that, in the received view, the Virgin and Child in the panel you can see here were painted by Masaccio, while the figure of St Anne was executed by Masolino (look at her hands, and then look at Mary’s hands).

In the case of Santa Maria del Carmine, the general plan seems to have been for Masaccio to work on the left wall and Masolino on the right.

Sadly, work was interrupted before they had finished. Masaccio died shortly after the interruption (still a very young man); and the Brancacci family came upon hard times. It was not until the 1480s that they could afford to call in Filippino Lippi to complete the planned cycle.

The 1980s restoration, however, does confirm that Filippino was an extraordinarily talented artist, and indeed one of the best portrait painters of his time. In short, the family could have done a great deal worse.

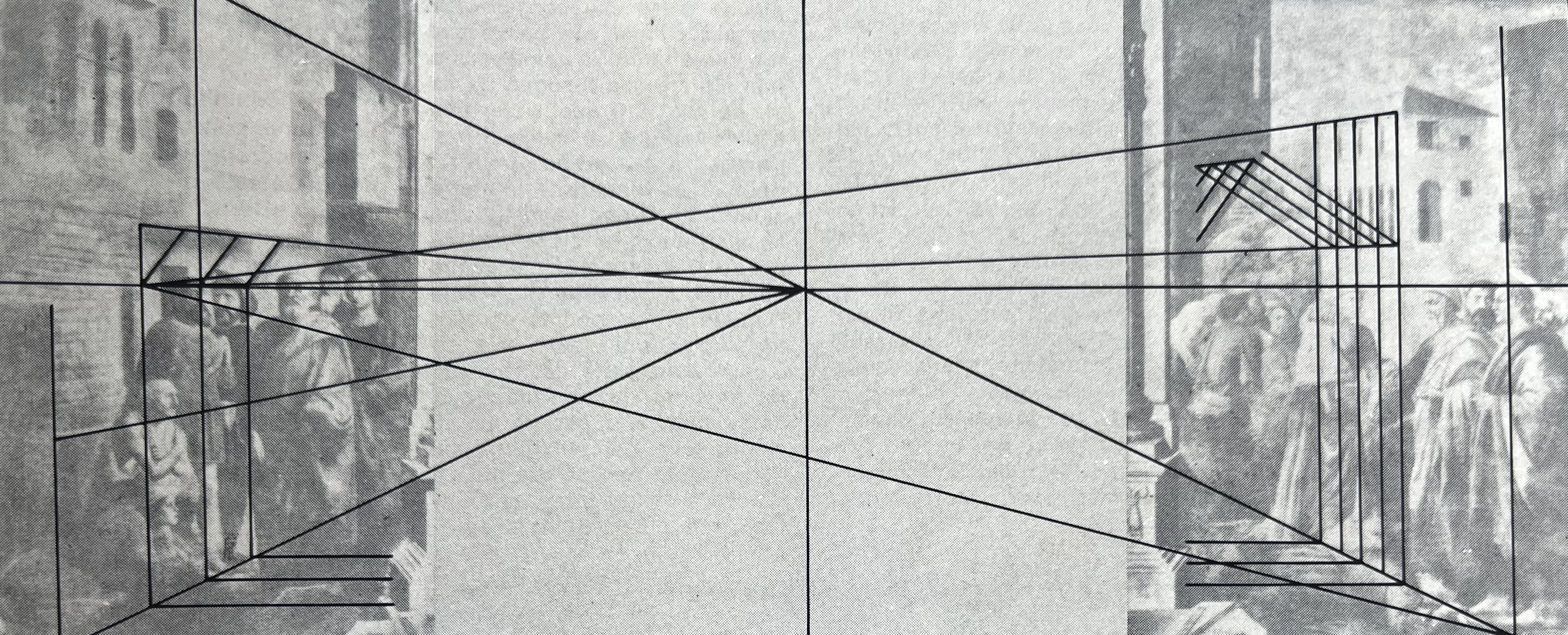

The layout of the surviving frescoes is made clear in this perspective diagram, which confirms that the shape of the chapel presented certain problems for the two painters, given that the frescos on either side of the altar and those on the entry arch are rather narrow (only about three feet wide), while the four main areas to be decorated are extremely broad (about twenty feet), and had to be divided up, so that each would contain two distinct episodes.

The hero of the cycle is none other than St Peter. Surprisingly, perhaps, this was a somewhat unusual choice; and it has led some critics to see a connection with the end of the great schism in the Catholic Church and the return to Rome of the newly elected pope, Martin V, in 1420, where it is known that Masolino and Masaccio worked for him.

Other critics have related the choice to Florentine politics. In particular, two of the scenes which give prominence to the punishment of tax-dodgers and to the Church’s obligation ‘to give Caesar his due’ are said to reflect the economic crisis caused by the third major war in a period of twenty years, and the drawing up of a new tax system and a new tax register in 1427.

However, everything in the narrative cycle becomes clear once you realise that you must take as your guide the most famous of all medieval compendiums of saints’ lives, the Golden Legend, where the entries are organised to form a calendar of saints’ days for the liturgical year.

The story told in the lower tier is taken from the entry for February 22nd, which is a minor feast of St Peter. The scenes chosen for the upper level and for the altar wall all come from the New Testament, but they are precisely those which had been singled out by the author of the Golden Legend in his preamble to the main entry for St Peter, whose major Feast falls on June 29th.

However, the narrative begins with a very special Prologue taken from the opening of the Old Testament, which forms the subject the upper pair of frescos on either side of the entry arch.

These frescos face each other, and measure about seven feet by nearly three.

In all their collaborations, the two ‘Toms’ never made a happier division of the work, and this arch is undoubtedly the best place to study the differences between the smooth, graceful style of Masolino in the Temptation, and the intensely dramatic art of Masaccio in the Expulsion.

Had the two artists switched subjects, the result might have been disastrous.

Masolino’s Eve glances sideways at Adam, coolly but not uninvitingly, twining her left arm around the tree in imitation of the serpent, whose alluring face and long hair could be interpreted as the expression of Eve’s inner self.

Her gesture reveals her small, high breasts, and her rather Flemish proportions. Her legs are almost fused together, like the Ghiberti bronzes we shall examine in the next lecture.

Adam stands equally motionless, his face relatively inscrutable.

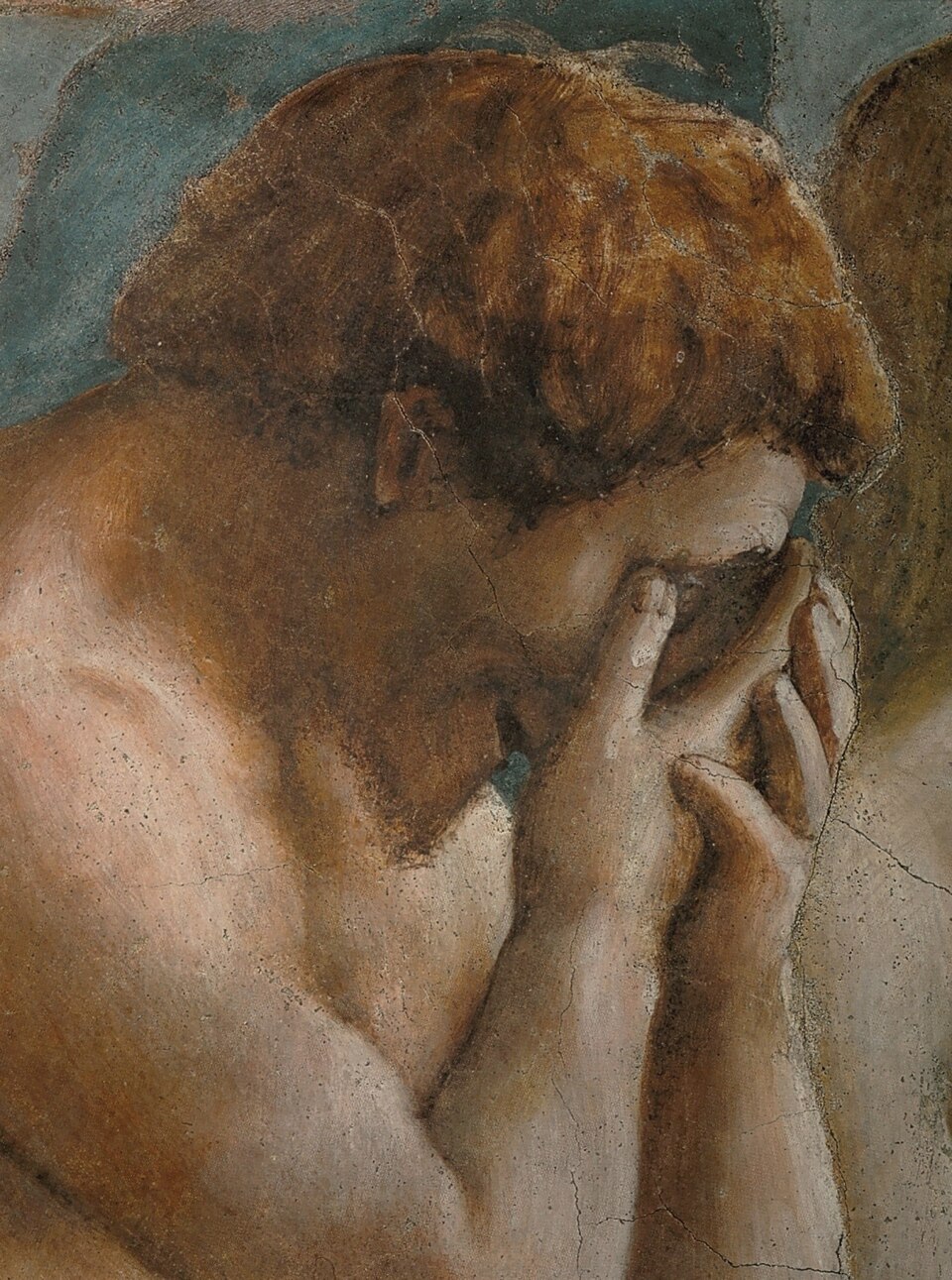

Masaccio’s pair seem to stumble out through the narrow gate of Paradise, driven by the fiery cherub with his sword.

The two details show Adam’s massive shoulders hunched as he buries his face in his hands, while Eve throws her head back, using her hands to cover her breast and her sex. Her face is torn by one dark patch for her mouth and two diagonal slashes, standing for her eyes. A great deal of the visual impact depends on the very exciting brushwork.

Masolino seems to draw a careful outline and then model and colour it with delicate touches; Masaccio goes straight at it with a loaded brush, modelling the hair, ears, chin, sternum and hands as though it were the easiest thing in the world.

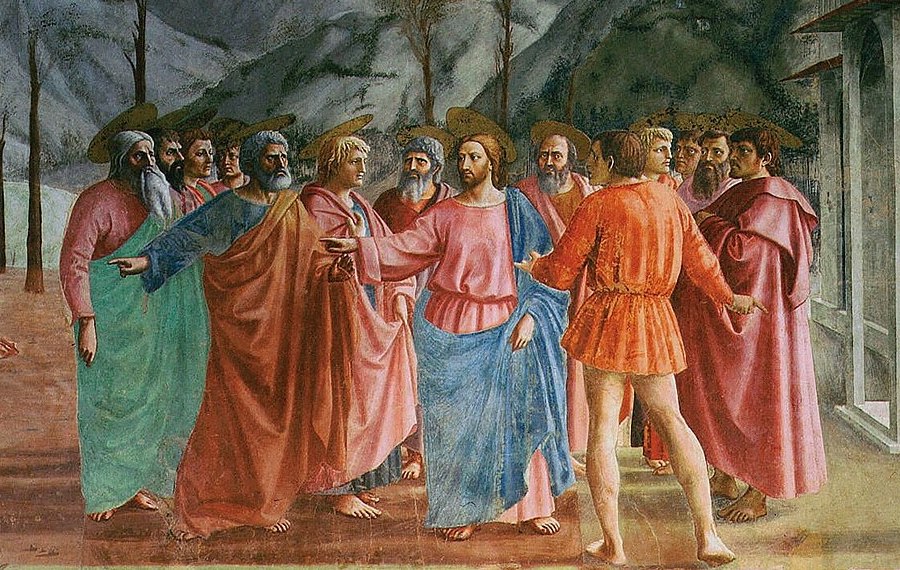

We can now move past the Expulsion to the long fresco at the top of the left wall.

This measures fully twenty feet by eight and a half and is universally regarded as one of the most important milestones in the art of the Renaissance.

Let me call attention, first, to the direction of the imagined source of the light.

In every scene in the cycle, the source of the incident light is made to coincide with the fall of natural daylight through the window above the altar, such that all the figures on this wall, including the Expulsion, are illuminated from right to left, while all those on the other wall are lit from left to right.

The story itself, halfway between a folk tale and a miracle, is rather unpromising from the point of view of a narrative painter, and not at all common in Western art.

It is narrated in the Gospel of St Matthew, chapter 17, immediately after the Transfiguration (when Jesus had distressed his disciples by prophesying that the Son of Man will be killed).

When they came to Capernaum the collectors of the half-shekel tax went up to Peter and they said: “Does not your teacher pay the tax?”. He said, “Yes”.

And when he came home, Jesus spoke to him first, saying: “What do you think, Simon? From whom do kings of the earth take toll or tribute? From their sons or from others?”. And when he said, “From others,” Jesus said to him, “Then the sons are free. However, in order not to give offence to them, go to the sea and cast a hook, and take the first fish that comes up, and when you open its mouth, you will find a shekel; take that and give it to them for me and for yourself”.

There are therefore three moments in the story, and our hero is shown three times.

First, he echoes his master’s gesture in the direction of the lake while scowling fiercely at the impudent tax man; then (on the left), he squats clumsily beside his cast-off robe, while he prises open the fish’s mouth (Vasari greatly admired the flush of effort on his cheeks, although I can’t see much of a flush). Finally, on the right, he thrusts the money contemptuously into the tax collector’s hand, in a gesture that appealed to Michelangelo so much that he made a drawing of it.

What is not immediately apparent—because the built forms are all kept on one side of the composition—is that the perspective system of the whole fresco is structured by the principles that would soon be formalised in Alberti’s Della pittura (1436).

The custom house (on the right), with its classically rounded arches, is big enough (just) in proportion to the human beings, while its orthogonals locate the single vanishing point as being behind Christ’s head.

It is the vanishing point which controls both the placing of the figures in the main group and the recession of the trees and the hills, which have long been recognised as the first truly distant hills and trees in Renaissance Art. (They emerged staggeringly well after the recent cleaning.)

It is, of course, to the main group in the foreground that the picture owes its fame, and we must close in a little to register some of its most important features.

First—and so obvious to us now that we take it for granted—the heads of all members of the group are at the same height, because they are all equally tall and are standing on the same flat ground. This is one of the most elementary, and yet most important, consequences of the system of perspective devised by Brunelleschi and Donatello.

Second, the general arrangement of the figures is that of a circle or ellipse.

(This, incidentally, may have been suggested by a sculpture in one of the niches at Orsanmichele, next to Donatello’s St George, which shows four little-known saints called the Quattro Santi Coronati, ‘the four crowned martyrs’, which was carved around 1413.

The four saints stand in a semi-circle, facing inwards, with solemn, rather classical features, wearing long togas or mantles.)

The features of Massacio’s Apostles are truer to life, anatomically speaking, than anything we saw in Giotto, but they are still appropriately stylised and simplified in a very sculpturesque idiom, so that Andrew, on the left, for example, is reminiscent of Donatello’s senatorial St Mark.

St John has reminded many people of Donatello’s St George: not in the proportions of the head and neck (John is much stockier), nor in the nose (John is much more Grecian), but in the spirit or expression—a synthesis of the classical and the modern or the Christian and the heroic—and also of course in the very sculpturesque treatment of the hair.

This head is also a wonderful example of Massacio’s powers as an observer of directed light and as a wielder of sticky coloured pigments clinging to a brush. The eye is warm and moist, the light strikes the forehead from the right, catches the bridge of that classical nose, touches the cheek, washes out the natural colour of the lips—then hits the up-facing plane below the mouth and the left of the neck, while leaving all the rest in shade.

One could and should look at every head in the composition with this kind of care but let us come back to the grouping.

Note the contrast between the rear view of the tax collector, who is the only one in contemporary dress, and the traditional, heavy, timeless, woollen robes of Jesus and the Apostles.

Register, too, the restrained rhythms of the solemn gestures.

Jesus both points and looks to his right; Peter points in the same direction, but faces the tax collector, who gestures both towards Jesus and towards his custom house. His gestures are also guiding our eyes outwards to the two subsequent events shown on the flanks of the picture.

One final point about the heads.

The Apostle on the right is painted vividly enough for him to have been interpreted as a portrait (indeed, a self-portrait). Every brush stroke is ‘pure Masaccio’.

But the face of Jesus is so serene and so smoothly modelled that many critics have suggested that it must be the work of Masolino, who would have stepped across from the scaffolding on the adjacent wall to paint the face of the Saviour, and thus bring out the likeness between the Second Adam and the unfallen Adam of the Temptation.

The biblical source of the narrative now moves from Matthew’s gospel to the Acts of the Apostles, which will supply the material for the four scenes on the altar wall and the long scene in the upper register on the right wall.

The scenes were chosen—with an eye on the entry in the Golden Legend—to bring out the character of St Peter as a successor to Christ in his mission of preaching, baptism, miraculous healings and raisings from the dead, a mission that would lead to Peter’s imprisonment and in the end to his crucifixion.

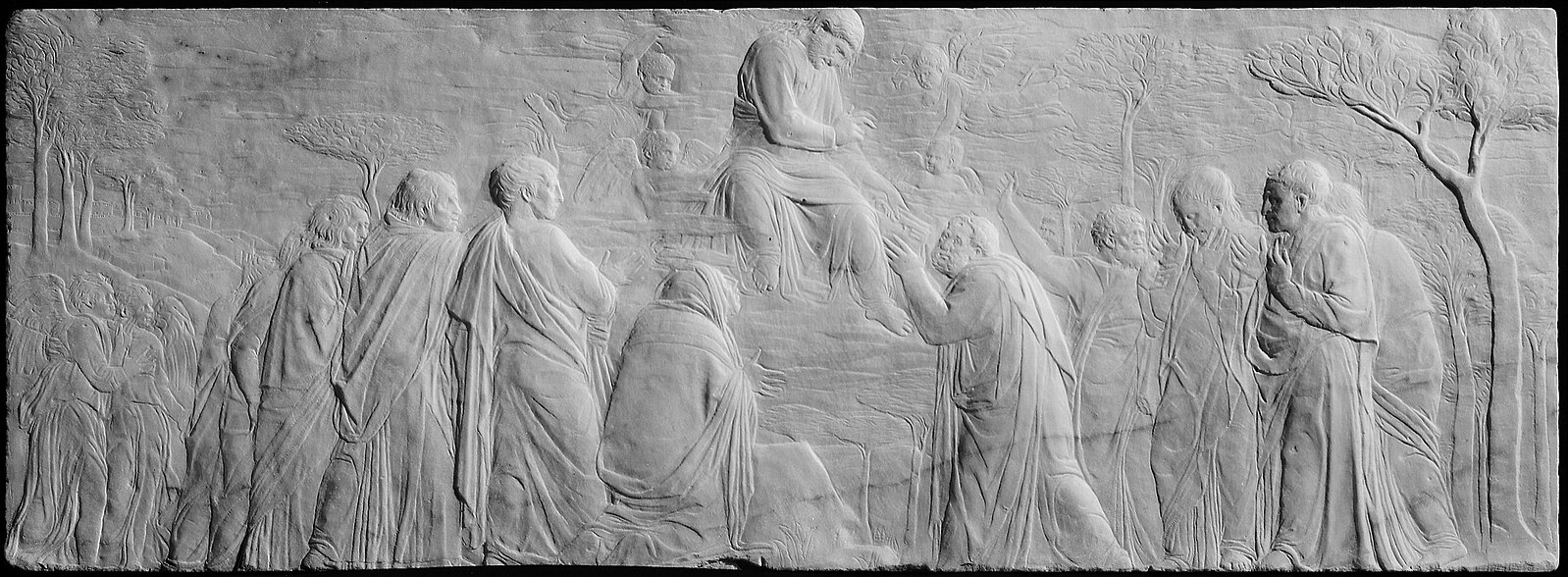

It is highly probable, incidentally, that the altarpiece provided a narrative link between St Matthew and the Acts of the Apostles, reasserting Peter’s unique authority by means of a small marble stiacciato panel by Donatello, carved in the 1420s (and now a brilliantly white object in the Victoria and Albert Museum).

This shows Christ handing the ‘Keys of the Kingdom of Heaven’ to Peter before being ‘taken up into heaven’, as we are told in the first chapter of Acts (1:6–11).

It has yet to be proved that the relief was placed in the Brancacci chapel; but even if it never was, it serves as a reminder that, in the same moment as Christ ascended, the Holy Spirit descended on his followers and they became ‘witnesses in Jerusalem, and in all Judaea and Sumaria and to the end of the earth’.

The next scene (still in the upper tier, adjacent and at a right angle to the last) lies immediately to the left of the altar.

It illustrates the second chapter of Acts, and represents Peter’s first recorded sermon, preached immediately after the descent of the Holy Spirit, which had come ‘like the rush of a mighty wind’. (The grey hills, their trees now visible again after the restoration, are meant to be continuous with the hills in the Tribute Money.)

You can see that Peter preached earnestly and that most of his audience listened attentively. (Incongruously, the listeners include two White Friars.) It has to be admitted, though, that some of the listeners seem to have fallen into a kind of trance, and I am sure you will have sensed straightaway that this cannot be the work of Masaccio.

Indeed, everything in the fresco—faces, garments, hills—could be usefully studied as ‘pure Masolino’.

The episode is briefly recorded at the end of the same second chapter of the Acts of the Apostles.

After Peter has concluded his sermon, we read: ‘So those who received his Word were baptised, and there were added that day about three thousand souls’ (2:41)—of whom we see about a dozen.

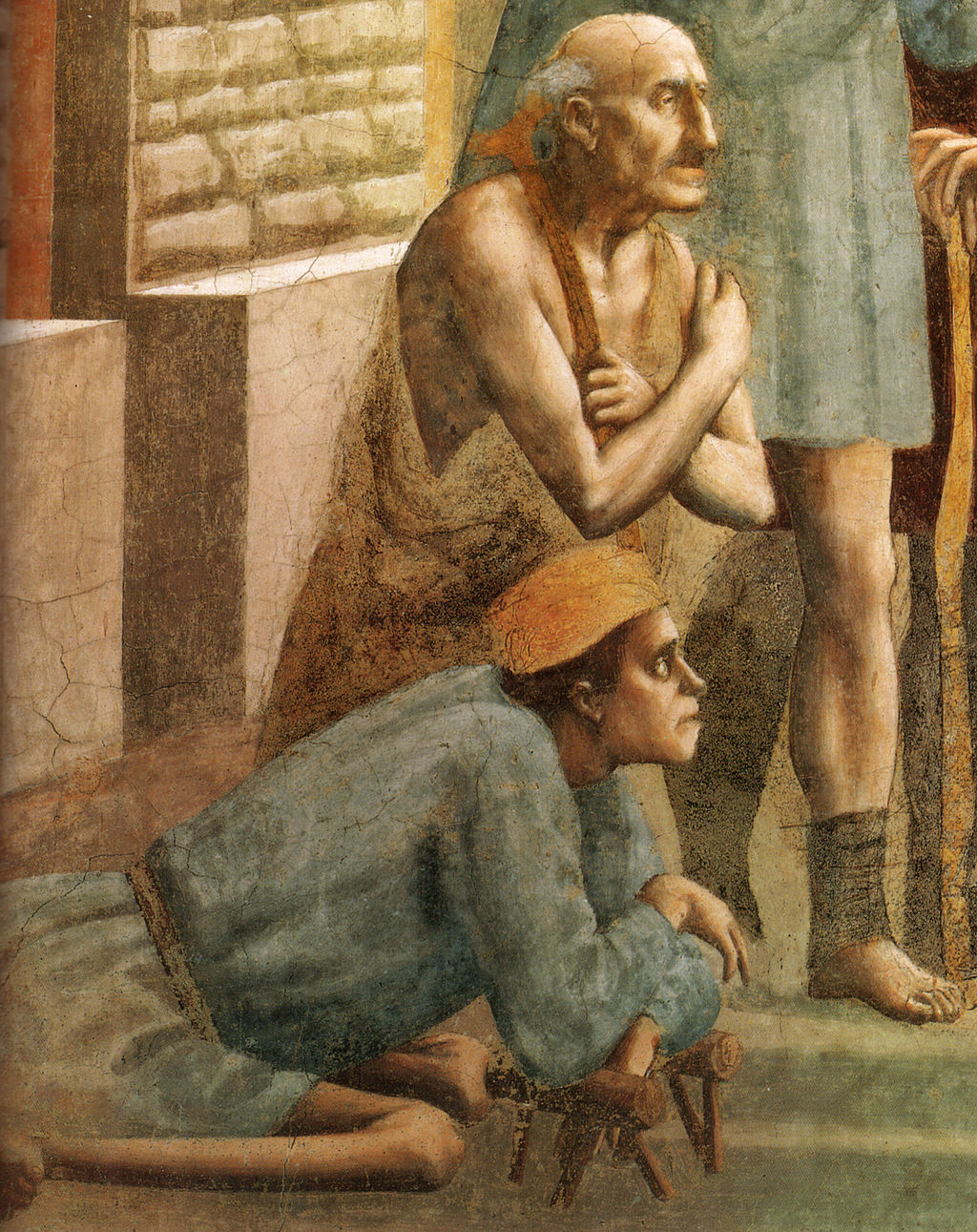

A shallow stream flows toward us, and Peter stands with his feet planted on the diagonal, turning his body slightly back into profile as he uses a backhand gesture to pour water—rather generously, from a good-sized bowl—over the head of the kneeling figure, who is also placed diagonally. His hair is being washed forward, and his torso, boldly lit and modelled, recalls that of Adam in the Expulsion—Adam, whose ‘original sin’ is here being washed away.

Behind him, one figure is slipping out of his bath-wrap; while the next-in-turn, standing in his undergarments in the freezing water, crosses his arms over his breast with an expression that Vasari interpreted as ‘trembling and shivering with cold’.

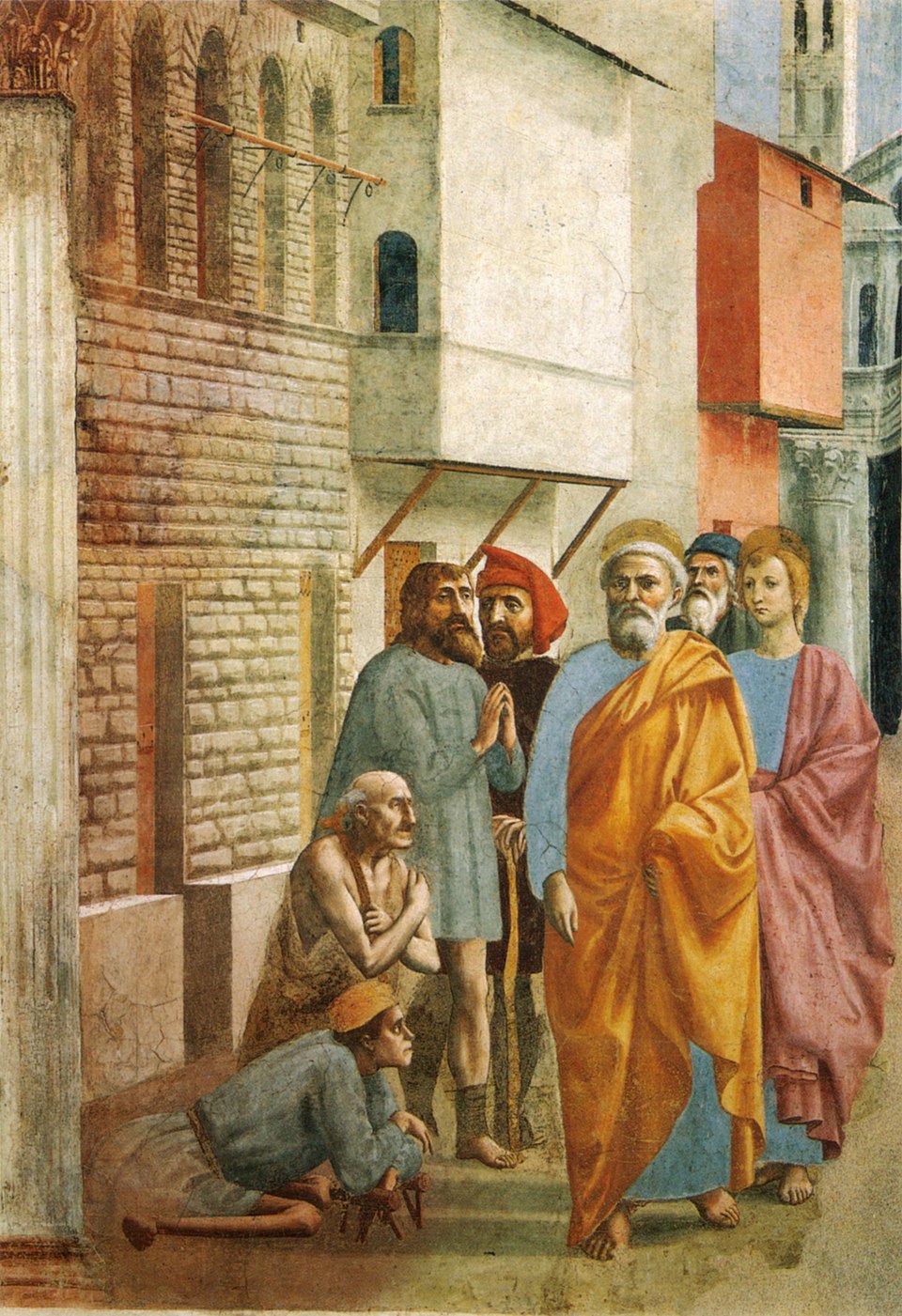

The next pair of narrow scenes are both by Masaccio.

They lie immediately underneath the ones we have just looked at. And, once again, it is important to visualise the altar as separating them.

As the useful diagram shows, the altar space is vital to a double tour de force of perspective, because the orthogonals from the left-hand scene guide the eye to a point outside the picture, in the middle of the altar piece, whereas the orthogonals from the right-hand scene actually converge on the wall of the left-hand scene.

Thus, even before we try to understand the story, we are entitled to enjoy this virtuoso anticipation of Alberti’s ‘legitimate construction’ (in which there is always only a single vanishing point, which may lie at any point on the horizon and does not need to be placed within the frame of the picture).

Before we come to the narrative, please enjoy the representation—in the left scene—of a quintessentially Florentine street, where the rusticated stone façade of an impressive palazzo contrasts with the coloured intonaco of the domestic houses with their cantilevered extensions; and—on the right—let your eye be led right back to the diminutive fortified manor house, which is now, for the first time, represented at a credible distance in pictorial space.

Remember, too, that perhaps the single most remarkable technical feat is the cut-off corner of the projecting balcony, opposite the austere, white building.

The story in the right-hand scene is told in chapter 4 and the beginning of chapter 5 in the Acts of the Apostles.

There was not a needy person among them, for as many as were possessors of lands or houses sold them and brought the proceeds of what was sold and laid it at the Apostle’s feet; and distribution was made to each as any had need.

But a man named Ananias with his wife Sapphira sold a piece of property, and with his wife’s knowledge he kept back some of the proceeds, and brought only a part and laid it at the Apostle’s feet.

But Peter said, “Ananias, why has Satan filled your heart to lie to the Holy Spirit and to keep back part of the proceeds of the land? You have not lied to men but to God.” When Ananias heard these words he fell down and died. And great fear came upon all who heard of it.

The light is imagined as coming from the central window (and therefore from left to right). It throws into strong relief the features of both St John (who is very like he was in the Tribute Money) and St Peter (whose pudding-bowl haircut makes me think of the black cap that judges used to wear when passing sentences of death).

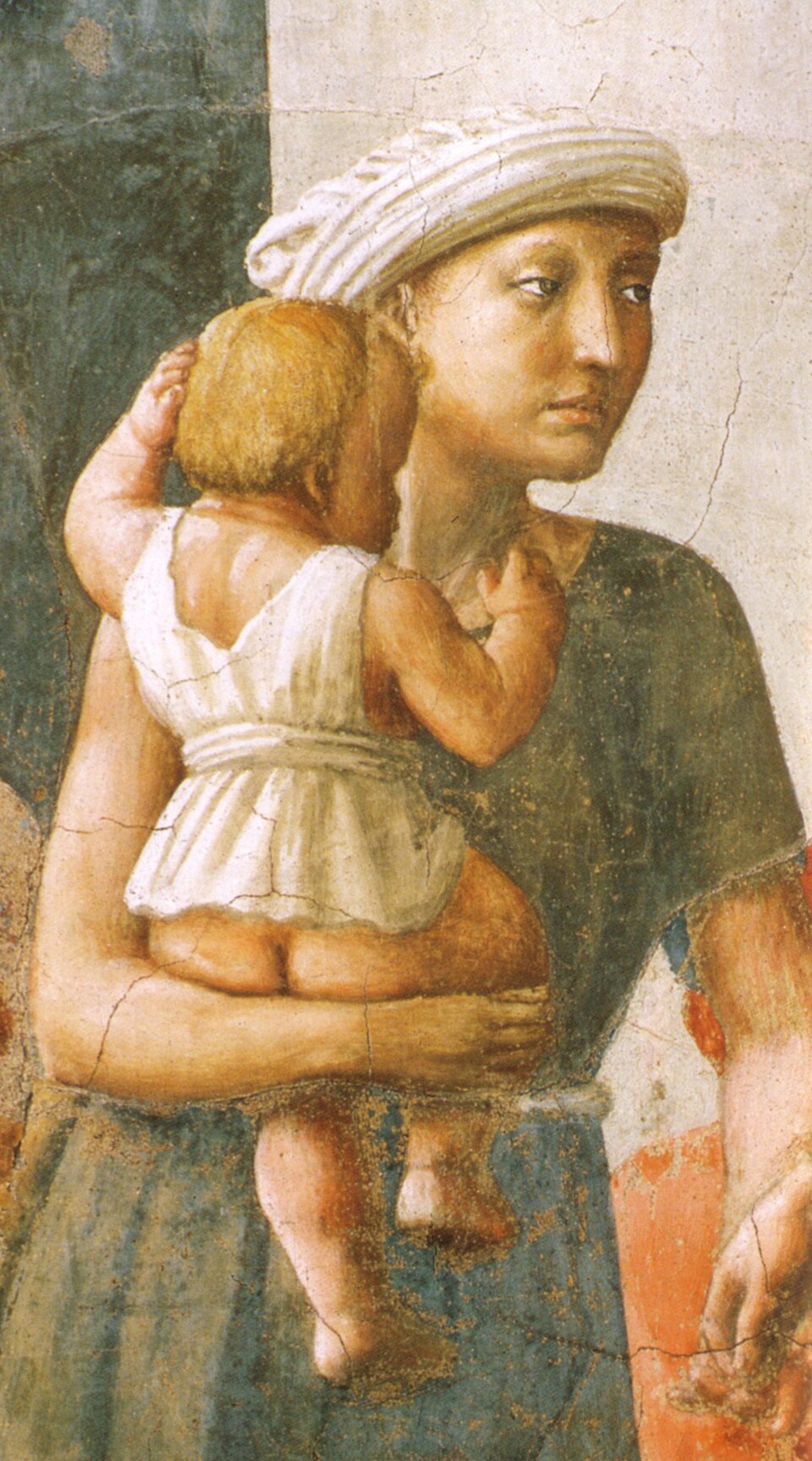

But any prize for relief-modelling ought to be awarded to the young woman with her bare-bottomed child, both of whom strongly recall the Madonna and Child whom we saw in the altar piece from Pisa. (We are hardly aware of the corpse of Ananias on the ground at Peter’s feet.)

We must press on to the scene on the left of the altar, which follows without a break in the fifth chapter of Acts.

‘Now many signs and wonders were done among the people by the hands of the Apostles.…And more than ever believers were added to the Lord, multitudes both of men and women, so that they even carried out the sick into the streets, and laid them on beds and pallets, that, as Peter came by, at least his shadow might fall on some of them.

The people also gathered from the towns around Jerusalem, bringing the sick and those afflicted with unclean spirits, and they were all healed’.

What you see is Peter’s shadow, apparently cast by light from the central window, falling from right to left across the three sick men. The first is already giving thanks for the miracle; the second is rising; the third is looking up, just after the shadow has passed.

The miracle is made even more miraculous, because it is seemingly unwilled by Peter himself.

The scene on the left of the fresco is usually said to illustrate an earlier episode (in chapter 3 of the Acts), in which Peter heals a man who had been lame from birth. (The wording certainly seems to have exercised some influence.)

Peter directed his gaze at the man, with John; …and he took him by the right hand and raised him up and immediately his feet and ankles were made strong.

If this is the correct interpretation, we would still be in Jerusalem, and the loggia on the left would represent the ‘Gate of the Temple which is called “Beautiful”’ (3:2).

However, the wording of the preamble in the Golden Legend, which I mentioned earlier, lends force to the alternative interpretation, namely, that we have moved into Judaea and Samaria, and that we are in the little town of Lydda, twenty-five miles east of Jerusalem.

Witnessing the healing of a man called Aeneas, who had been paralysed for eight years:

Peter said to him, “Aeneas, Jesus Christ heals you; arise and make your bed”. And immediately he rose.

The episode involving Aeneas is told towards the end of chapter 9 in Acts and is followed immediately by what is unquestionably the scene to the right, which also makes sense of the two men in the centre. For chapter 9 continues:

Now there was at Joppa a disciple named Tabitha…She was full of good works and acts of charity. In those days she fell sick and died; and when they had washed her, they laid her in an upper room [in our fresco, it is the ground floor].

Since Lydda was near Joppa, the disciples, hearing that Peter was there, sent two men to him entreating him, “Please come to us without delay.”

So Peter rose and went with them. And when he had come, they took him to the upper room. All the widows stood beside him weeping, showing coats and garments which Tabitha made while she was with them. But Peter put them all outside and knelt down and prayed; then turning to the body he said, “Tabitha, rise.” And she opened her eyes, and when she saw Peter she sat up.

The detail clearly shows the ‘coats and garments’, mentioned in the text, as well as the two widows.

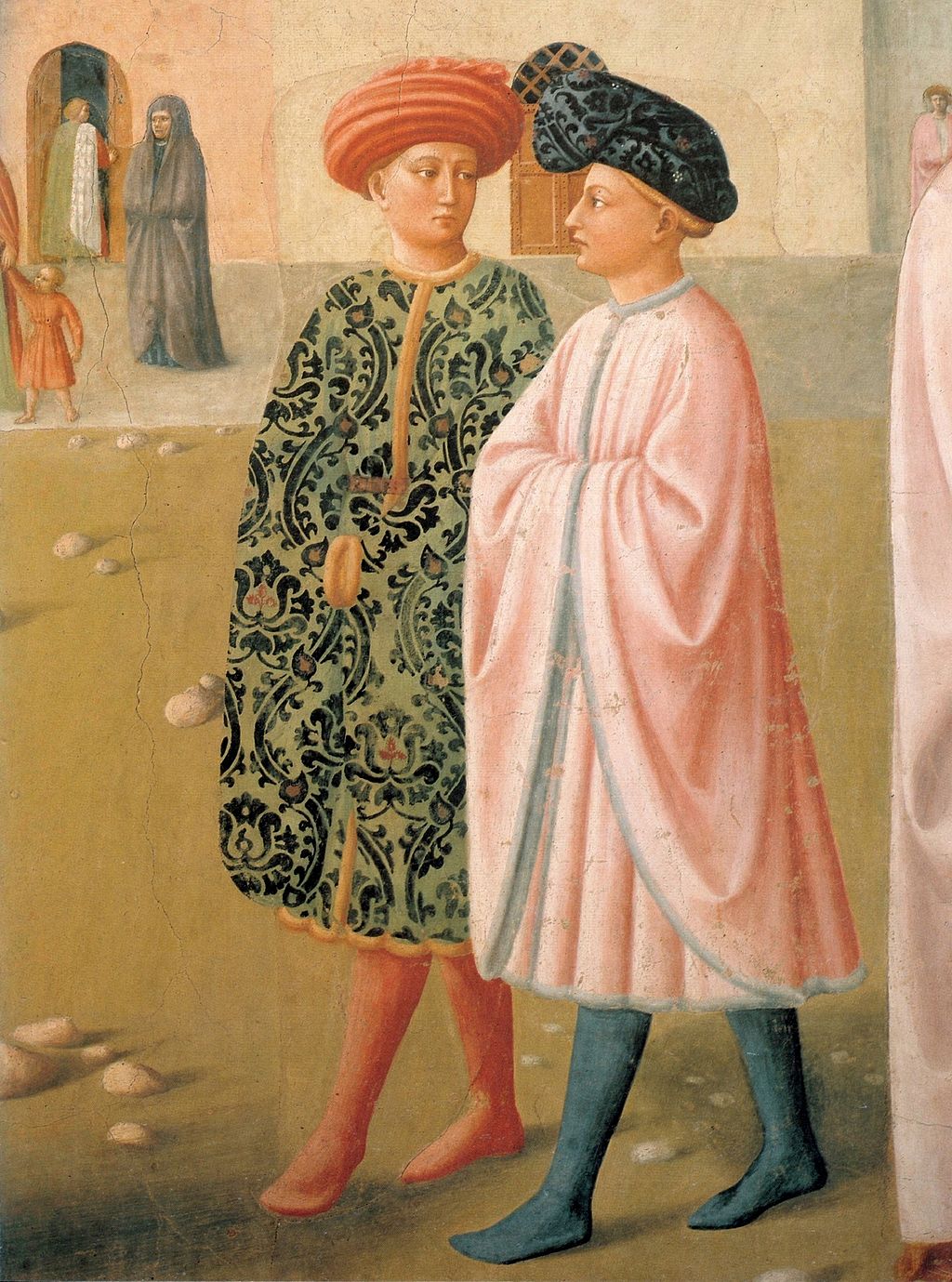

It is almost an insult to your recently acquired skills to point out that all the figures in the fresco must be by Masolino—you have only to look at Peter’s head as he says ‘Rise’; or at the placid, round faces of the two young men in their fashion-plate hats.

So, let us go straight down to the lower tier on this wall, beginning with the little scene lying at the bottom of the entry arch – where the artist is neither Masaccio nor Masolino, but Filippino Lippi, who completed the cycle some sixty years later.

The story is told in the Golden Legend in the entry for February 22nd, a lesser feast of our saint, known as ‘The Chair of Peter’.

St Peter has left Judaea and Samaria and has come to Antioch (in the southernmost corner of modern Turkey). There, his refusal to stop preaching has led the prefect Theophilus to throw him into prison, in irons, and without food or water.

St Paul comes to Antioch and presents himself to Theophilus ‘as a skilled artist, able to carve in wood or marble, and to paint on canvas’.

Paul locates Peter in prison and brings him food and water. Then he intercedes for his release, arguing, among other things, that Peter would be useful, since—as we have just seen— ‘he could cure the sick and raise the dead’.

To all this Theophilus replied: ‘These are but idle tales, my dear Paul; for if this man could raise the dead, he could surely rescue himself from prison!’

In the event, however, Theophilus agrees to release Peter, provided that ‘he restores my son to life, who has been dead these fourteen years’.

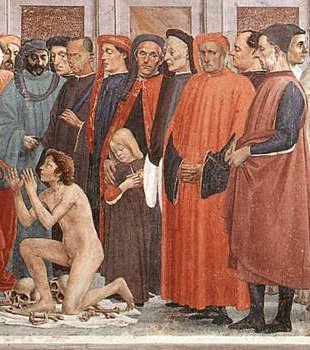

This is the challenge that Peter accepts in the scene in the left half of the main fresco.

While St Paul kneels and prays—it must be Paul because of his halo—St Peter raises the young man from the dead (notice his skull and bones on the ground).

The spectators remain remarkably calm as they witness the miracle; and this may be in part because the artist is reflecting the scepticism shown by the author of the Golden Legend himself, who, having completed the story, continues as follows:

‘But we must admit that this miracle seems very unlikely to us, not only because of the fourteen years which God is supposed to have allowed the dead man to spend in the tomb, but also because of the ruse and the falsehood which the story attributes to St Paul.’

I used the generic term ‘artist’ advisedly, because this is the fresco which Masaccio had to abandon half-finished in 1427, never to return. Most critics concur that the figures on the left (from Theophilus to the bareheaded figure in red) were painted by him, while those in the centre of the fresco, including the resurrected youth, were done by Filippino Lippi in the 1480s.

(We shall see in a moment that Masaccio had already painted the distinct scene on the right of this long fresco, but I am going to reserve discussion of that scene for my finale.)

I shall now interrupt the course of the story in order to present, very briefly, the long fresco on the opposite wall, the whole of which was painted by Filippino Lippi (although the episode and the pictorial layout were quite clearly part of the original design).

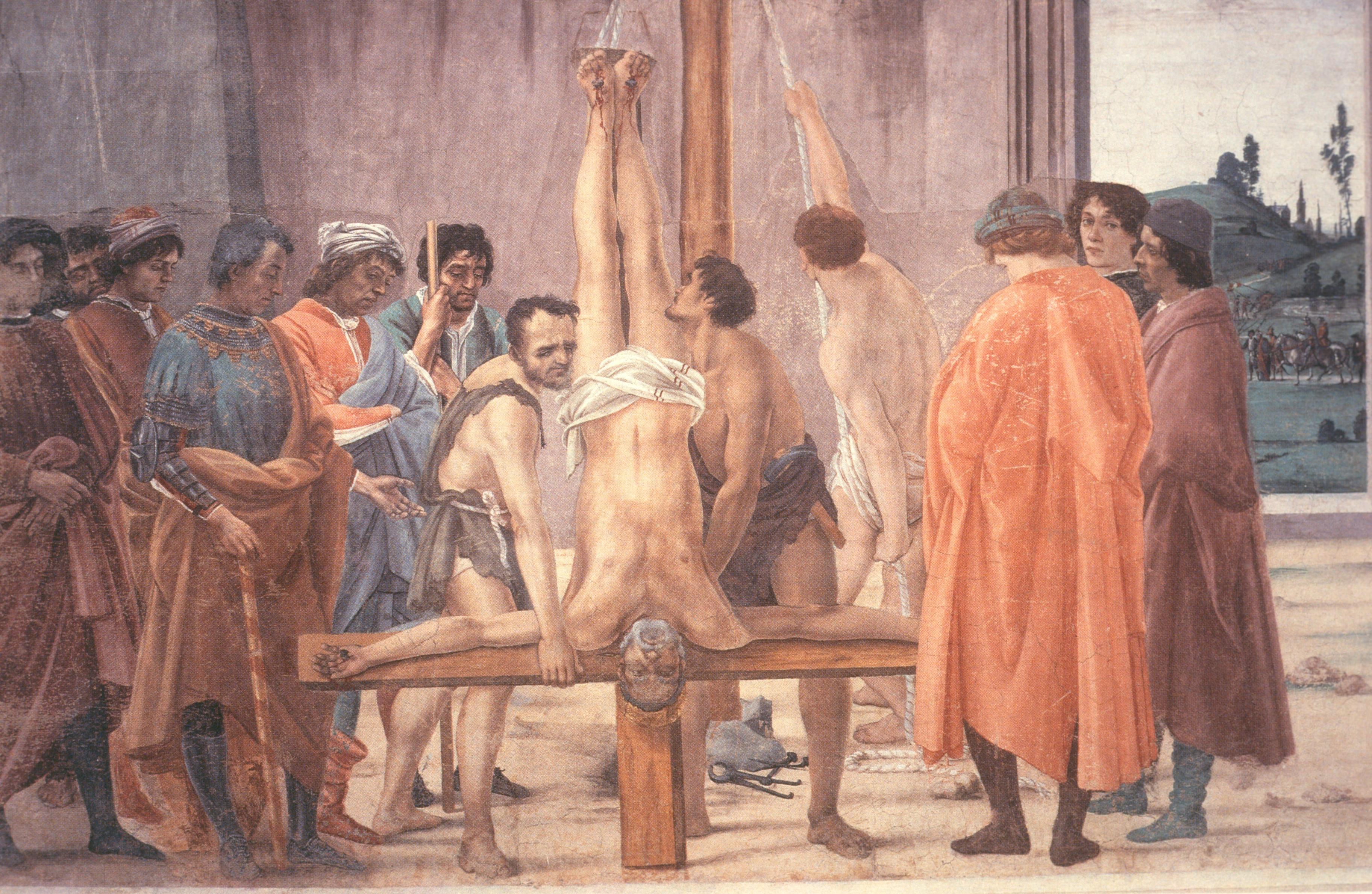

The two successive moments—trial and execution— are taken from the Golden Legend in the entry for June 29th.

The scene has shifted from Antioch, where Peter remained for seven years, to Rome; and the story of his life ends with the grisly climax to the twenty-five years he spent in the capital of the empire.

In the first scene (on the right), Peter and Paul appear in the presence of another autocratic ruler, seated on a throne.

This time he is the Emperor Nero, and the two apostles have been summoned before him as a result of their long-standing confrontation with a charlatan called Simon Magus, a kind of ‘witch doctor’, the authentic part of whose story is told in chapter 8 of the Acts of the Apostles.

(Paul and Peter are identified by very discreet halos, whereas Simon’s headgear and features bear some resemblance to those of Dante Alighieri in the standard iconography of the late fifteenth century. The young man on the extreme right is taken to be a self-portrait of Filippino.)

Peter and Paul are both sentenced to death. Paul, being a Roman citizen, is to be beheaded, while Peter, as an alien, is to die by crucifixion.

It is his crucifixion—upside down—which is shown in the left-hand scene.

In the original conception of the cycle, the representation of Peter’s crucifixion must have been intended to come as the climax of the whole story.

The relevant sentences in the Golden Legend run as follows:

When Peter came in sight of the Cross, he said: “My Master came down from heaven from earth, and so was lifted up on the Cross. But I, whom he has named to call from earth to heaven, wish to be crucified with my head towards the earth and my feet pointing to heaven. Crucify me head downwards, for I am not worthy to die as my Master died”.

And so it was done.

Having done our duty by the Brancacci family who commissioned the cycle and saw it through to its long-delayed conclusion, let us return to Antioch in the long fresco on the other wall, and to Masaccio, who did survive long enough to paint the figures in the place of honour nearest the altar.

There is not really any ‘story’.

It is simply an illustration of the last sentence in the tale of the resuscitation of the long-dead son of Theophilus:

Theophilus and the entire populace of Antioch were finally converted to the Lord, and erected a magnificent church, in the middle of which they raised a high throne for Peter, whence he could be seen and heard by all.

Masaccio links this legendary event to the church of the Carmelites in Florence (itself ‘a magnificent church’) by showing three members of that order in their white habits kneeling or standing near the throne.

The portrait head of the Abbot—mature, experienced, wide-eyed, tight-lipped—is a very fine psychological study. But, of course, posterity has tended to linger on the three portraits on the other side of the throne, the ones we glanced at in the introductory pages of this lecture—three of the greatest names in the history of the visual arts: Brunelleschi, Alberti, and Masaccio himself.

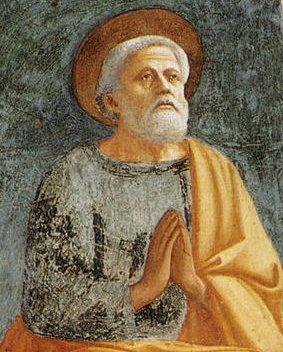

It is only fair, though, that our final image should be of St Peter himself, ‘lifted up in name and in power’, as the author of the Golden Legend puts it (quoting from the Psalms), and ‘set high’ on the chair of Antioch.

His noble face, beautifully modelled, is lit from right to left with the imagined light seeming to come from the real daylight, streaming in from the altar window.

His body and head are drawn from a low viewpoint so that St Peter may seem to loom over the worshippers in the Chapel.

Filippino’s image for the narrative climax of the cycle was disappointing, but Masaccio, shortly before his death, had provided a perfect pictorial climax.