Botticelli: Parallel Lives of Moses and Jesus

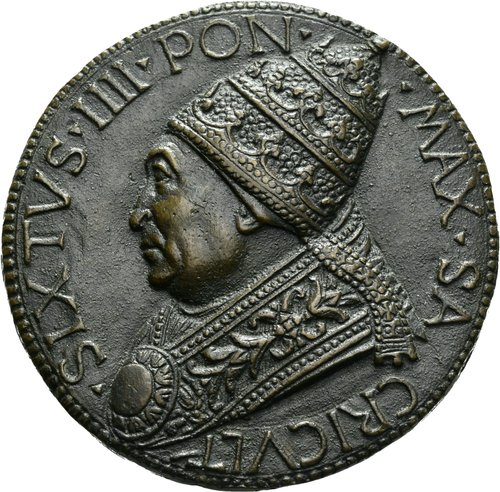

The first lecture was mostly devoted to the context—geographical, mythical, historical and ideological—of the rebuilding by Pope Sixtus IV in the late 1470s of the ‘Great Chapel’ next to St Peter’s, the chapel which has come to bear his name.

I began by glancing at the general layout of the paintings in the chapel and ended by considering, in a little more detail, the practical information encoded in the floor and the symbolic information encoded in the dimensions (‘sixty cubits long, twenty cubits wide, and thirty cubits high’, in homage to the Temple of Solomon).

In this lecture, we are going to look at the earliest group of paintings in the chapel, those that were planned with it, and for which the building was intended to be a vehicle—that is, the frescos which cover the walls from the floor up to the cornice near the top of the windows.

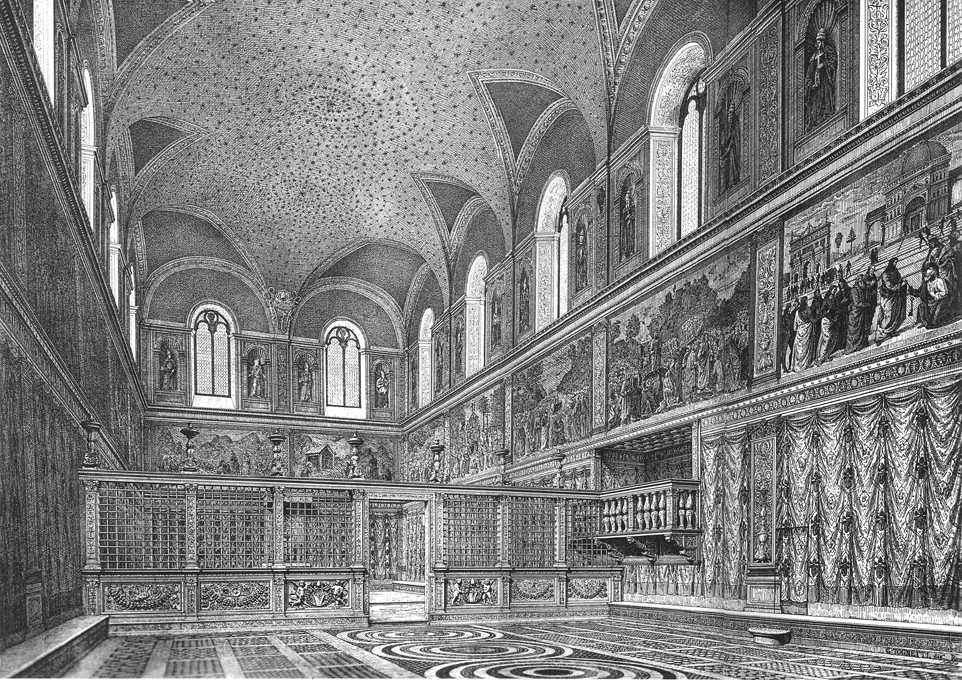

Let us begin by using this nineteenth-century engraving which offers a reconstruction of the chapel in its original form, in order to free our minds of the later contributions made by Michelangelo (on the ceiling, lunettes and altar wall).

The ceiling was originally painted blue (the colour of the ‘sky’ or ‘heaven’—‘cielo ’); and it may well have been ornamented with stars, as suggested in the engraving. It did not have any human figures.

The lowest section of the wall (the first fourteen feet or so, up to a stone cornice) was also free of human figures; and, as was typical, it was painted to simulate woven hangings or curtains.

The repeated motif in these fictive hangings (clearly visible in this coloured detail) contains a double allusion to Pope Sixtus: first, in the papal tiara and keys which are his badges of office; and, second, in the oak tree, which alludes emblematically to the family name of the pope—della Rovere, ‘of the oak’.

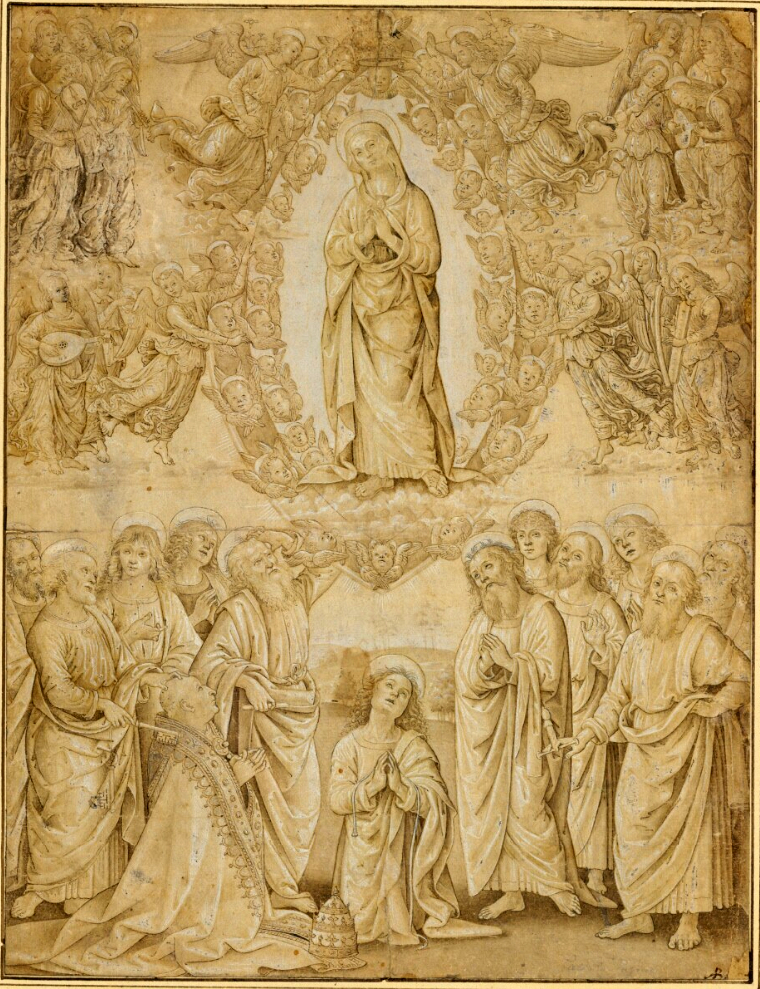

In the centre of the altar wall, however, the simulated fabric hangings gave way to a simulated wooden altarpiece, later obliterated by Michelangelo, of which we possess a fairly careful copy (or indeed perhaps a final study).

This represents the bodily Assumption of the Virgin—a doctrine which Sixtus had himself promulgated—reminding us that the chapel was dedicated to Mary, as ‘Assunta’.

It also has a portrait of Sixtus, as donor, kneeling on the left.

The section of the wall between the windows (of which there were two on the end walls, and six on each side) was painted with simulated statues, life-size and foreshortened from below, each standing in a simulated niche and representing the first thirty popes, all of whom had been canonised as martyrs.

The sequence runs from the time of the first pope, Simon Peter, the ‘rock’ of the Church (who, you remember, is buried about a hundred yards away), down to the time of Constantine, when Christianity was recognised as the religion of the state, and when persecutions came to an end.

We cannot be sure of the original layout of the altar wall (although it certainly had two windows as shown in the engraving). The most recent reconstruction suggests that Jesus would have appeared in the centre, flanked by Peter and Paul (who was also martyred in Rome), with the first two popes, Linus and Cletus, in the corners.

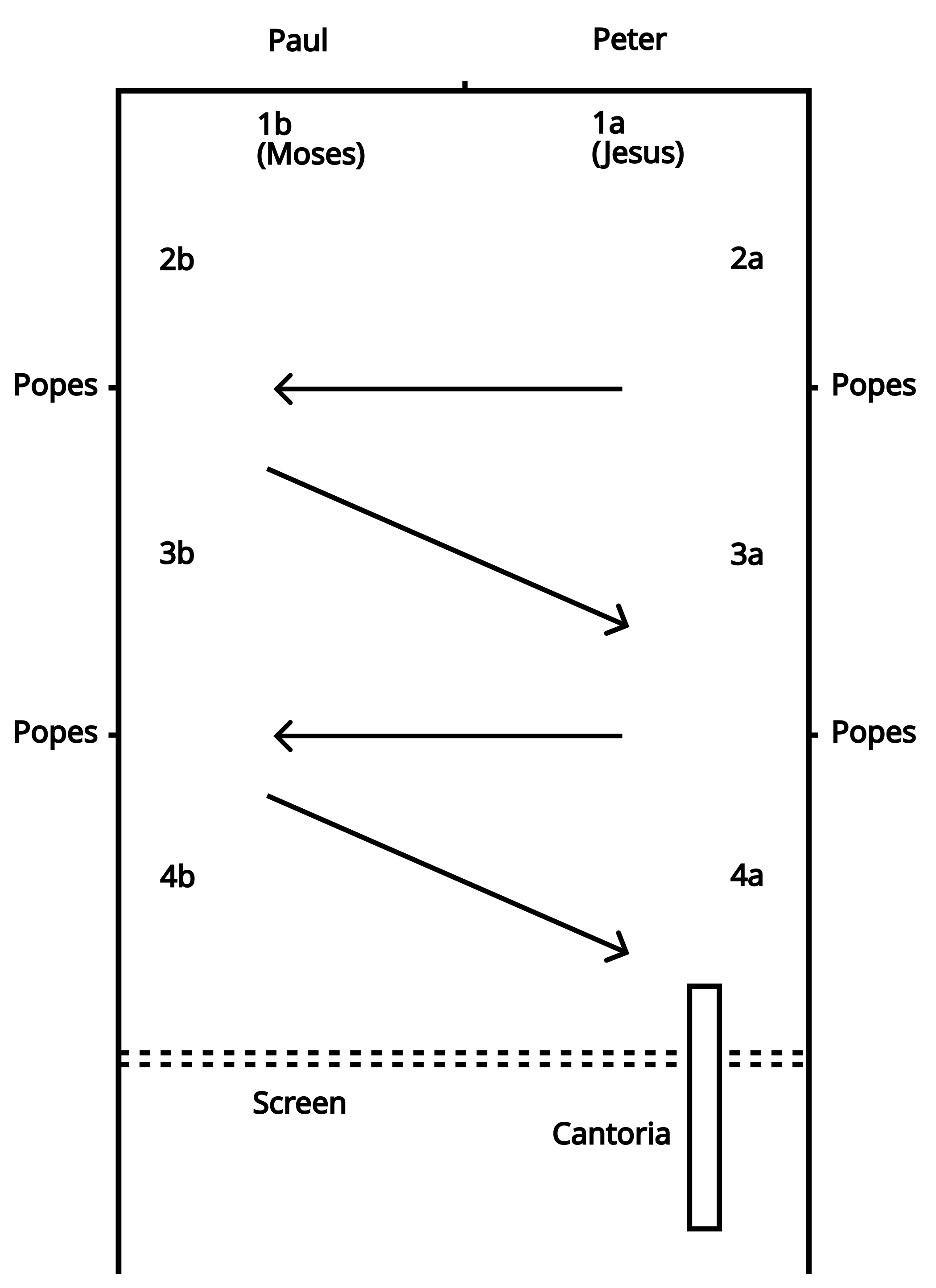

What we do know for certain, however, is that the sequence of popes—all of whom are duly labelled—does not run continuously round the chapel, but goes ‘right, left, right, left’ away from the altar wall, as illustrated by the arrows in my primitive scheme.

Artistically, these statues or portraits are not particularly interesting (you can judge the quality in this composite image).

However, the ideological argument is perfectly clear.

The authority of the present pope derives—in unbroken march (left, right, left, right) from Linus, the man appointed as his successor by Peter, down to the present day—Peter himself being the man appointed by Christ himself to be his Vicar on Earth.

Notice, in passing, the papal tiaras and the full pontificals, because these will be linked ‘retrospectively’ to the robes of the Jewish High Priest in the narrative paintings below.

Underneath the popes, in the central band of the wall, come the most important paintings, the ones which will concern us for the remainder of this lecture.

These are the narrative frescos; and they too have a simulated setting, because the frames are meant to be like window-frames, and you are to imagine that you are looking through the window at the scene outside.

Each one is just over twenty feet wide and about thirteen feet high, and each one has a very prominent title, in Latin, placed above.

Originally, there were sixteen of these frescos—eight to the north of the central line (on your right as you face the altar, which is at the West end), showing scenes from the life of Christ, and eight to the south, or left, dealing with the life of Moses.

They are not ‘simple’ narratives, however, because the Latin titles demand that each scene is to be paired with the one directly opposite, such that you should read them in the same sequence as the popes. And the precise parallels, spelt out in the titles, are based on the premise (then universally accepted, and in no way controversial) that Moses was a ‘figure’ or ‘type’ of Christ, meaning that certain historical events in his life ‘prefigured’, and were ‘fulfilled’ by, equally historical events in the life of the Messiah or Saviour.

As you can imagine, finding eight such major parallels (and a host of minor ones as well) involved a certain amount of ‘juggling’ or distortion to both lives. This distortion is compounded by Sixtus’s more polemical, and not universally accepted attempt, to extend the parallels in such a way as to link Moses and Jesus not only with each other, but with the reigning Pope—that is, all three are to be seen as Lawgivers and enforcers of the Law, and as supreme heads of a necessary priesthood whose power is not limited to the spiritual sphere.

If we were to extend the metaphorical line connecting each episode in the Moses cycle with its partner in the Jesus cycle, that line would lead straight to the Pope in every case. In other words, the choice of episodes and the pairings was determined retrospectively by the requirements of papal propaganda.

It is for this reason that I shall read the frescos ‘antiphonally’ in this lecture, rather than as two independent, straightforward narratives.

What matters is not the sequence down the length of the chapel, but the links across the chapel.

Having explained the layout and the argument of the ideological programme, I should now make a few general points about the painters.

Sixtus, you remember, was an old man in a hurry. So he hired four separate workshops to work simultaneously, each being responsible for one whole bay at a time. (Working from the top down, they would paint, first, the two popes, then the narrative fresco with its Latin title on a decorated frame, then the fictive curtains).

The oldest was Cosimo Rosselli (born 1439).His team executed more frescos than any of the others.

As you can see from this altarpiece, now in the Fitzwilliam Museum, he was stiff, rather archaic and simply not very talented. He is instantly recognisable by the elongated proportions of his standing figures.

The second was Botticelli (born 1446), a genuine myth maker, with a wonderful nervous energy of line and great panache, as you can see in the Adoration of the Magi from the year 1475.

(It happens to contain three posthumous portraits of members of the Medici family as the three Wise Men; and, no less important, a self-portrait at the age of thirty, in the foreground figure on the right in the ochre robe.)

The third was Domenico Ghirlandaio (born 1448), who was close to the epicentre of Florentine taste around 1480. Fluent, graceful and compliant, he had, however, clearly absorbed a great deal from Flemish oil-painters like Hugo van der Goes (look at the shepherds in the foreground).

He was Michelangelo’s first master…

The fourth was Perugino (born 1446), an Umbrian who had trained in Florence. He loved sombre colours and became best known for his oil-painting. His main limitation was that he was simply too ready to give the public what the public wanted—hence, he used a very limited range of sentimentalised stereotypes for his sacred figures. You can see virtually all of them in this triptych, now in our National Gallery.

He was Raphael’s first master…

Despite their differences, however, all four painters were typical fifteenth-century professionals, accustomed to working with a team of assistants, ready to collaborate with another team, and patiently accepting the conditions dictated by the patron.

In the case of the Sistine Chapel—seemingly, taking their lead from Perugino, who was responsible for the original altar wall and the first bays on each of the side walls—they accepted the choice of episodes laid down by Sixtus’ advisors, and they accepted the (by now rather old-fashioned) convention whereby the principal character or characters could appear in several different episodes within a single frame.

The artists were all willing to put numerous portraits of members of the ‘papal chapel’ among the ‘spectators’, who would be ranged prominently across the foreground of each scene.

They agreed on a common scale for these foreground figures and a common height for the horizons; and they agreed to use a lot of gold for the highlights (again a rather old fashioned detail) in order to give greater splendour and to make the frescos more visible by candlelight.

Finally, the four teams all agreed to represent the fall of pictorial light in every fresco as though it came from the original two windows on the altar wall, which (in the case of the Sistine Chapel, is the west wall).

These windows would have admitted the most natural light in the late afternoon, which was the time when all the major services were celebrated in the chapel.

So, in this fresco (from the Life of Jesus), which lies on the north wall, the left side of the face or body is lit, while the right side is in the shade. (This is very clear in the detail.)

Whereas, in the frescos in the parallel scene (from the Life of Moses), on the opposite wall, light will seem to fall from right to left.

We are ready now to look closely at the first surviving fresco in the Life of Jesus (bearing in mind that the series had begun with a Nativity, later overpainted, on the altar wall).

The original measures about twenty feet across, and is placed about fourteen feet above the ground.

The Latin title, above the fresco, says:

The Institution of the New Regeneration in the Baptism of Christ.

The figures in the foreground and centre derive from the traditional iconography of a Baptism. Jesus stands in his loin cloth in the shallow river Jordan, while St John pours water over his head from a basin, and God the Father appears in a ‘glory’ in the sky, sending down a dove (representing the Holy Spirit) to illustrate the words: ‘This is my beloved Son, in whom I am well pleased’.

Traditional, too, are the other figures waiting their turn for baptism, the angels who kneel holding their bath towels, and the tree stump that is putting forth a new shoot.

The setting, however, is very much of its time, being a rather lovely example of late fifteenth-century landscape, or more specifically, a lovely Perugino landscape. There is quite a lot of sky (beautifully graduated towards the horizon); fern-like trees; and an impressionistic lake, set among convincing hills, appearing blue from the distance.

To either side, there are relatively more stylised hills, or rather, cliffs, providing a dark ground which sets off the bright colours of the costumes in the two subordinate episodes, which are picked out in these two details.

To the left, you see John the Baptist, first, preaching repentance of sins, and then, walking towards the river Jordan; while to the right, Jesus, who is now clothed, is preaching a sermon concerning the remission of sins.

There are some lovely ‘passages’ (as they would have said in the eighteenth century) among the foreground groups, where you can enjoy closely observed contemporary costumes, some excellent portrait heads (of far greater interest than the sacred figures), and a clear rhythm in the grouping, which (as you can see in the upper detail) guides the eye from the left towards the centre, by a gesture or a glance.

There is a particularly pleasing family portrait in the group to the right—a father, flanked by two sons in their early teens (still with long ringlets) and other slightly older brothers behind (their hair shorter under the caps), who affectionately embrace their father and brother.

We may move now to the parallel scene on the opposite wall, entrusted, as you can see, to the same artist. You can sense immediately the unity of treatment in the placing of horizon, the sky, the dark green of the landscape, the volcanic cliffs, the distant lake in the valley (here moved off centre), the bright colours of the costumes, the two sacred figures confronting each other in the centre, and the groups to the left and right in the foreground.

It is the scene in the right foreground which gives its title to the painting and establishes the link between Moses and Christ, the Old Law and the New.

Just as Christ began his ‘Mission’ (or his task of ‘Regeneration’, as the Latin of the title has it) by allowing himself to be baptised, so Moses began the earlier regeneration by allowing his son to be circumcised, according to the laws of the Jewish people.

The title of this fresco is:

The Observance of the Old Regeneration by Moses through Circumcision.

To obtain the necessary parallelism, the theologian responsible had to take liberties with the sequences of the chapters in the Book of Exodus.

The scene in the upper detail occurs in Chapter Four; but the full significance of the story will only become clear when we study the adjacent fresco, which is derived from Chapters Two and Three.

For the time being, it is enough to know that Moses married a non-Jewish wife called Zipporah, and was living in Midian.

He had accepted the Lord’s charge to obtain the freedom of the Jews from slavery in Egypt, but his half-Midian son was still uncircumcised at the moment when he took his leave of his father-in-law, Jethro, and set out for Egypt again.

(The leave-taking is shown in the tiny background scene in the first detail; the start of the journey in the second.)

In the Greek Septuagint translation of Exodus 4:24 we read that ‘an angel of the Lord met him and sought to kill him’. (Look at the position of the angel’s arms, as he prepares to strike Moses in the centre of the whole composition).

(In the Latin of the Vulgate, incidentally, there is no mention of an angel. The subject of the sentence is simply ‘the Lord’.)

At this point, ‘Zipporah took a very sharp stone, cut off her son’s foreskin, touched Moses’ feet with it and said: “Surely you are a bridegroom of blood to me”’.

Typologically, it is important to know that the boy is called Gershon (which was known to mean ‘Stranger’, ‘Outsider’), and that Zipporah, the Midian wife, was regularly interpreted as a ‘prefiguration’ of the Church of the Gentiles.

Jesus, by accepting Baptism, would validate the ‘Church of the Jews’; while Zipporah had in a sense validated the Church of the non-Jews, by circumcising her son.

The next pair of frescos are by Botticelli and his team.

Once again we must return to the south wall, and begin by examining the later episode from the New Testament, the episode involving Jesus.

A literal translation of the Latin title would be:

The Temptation of Christ, the Evangelical Legislator.

But a genuine translation would be something like: The Trials of Christ Who Gave the Law of the Gospels.

Matthew’s Gospel specifies no fewer than three such ‘trials’ (in the sense of ‘puttings to the test’) and Botticelli boldly ranges all three ‘temptations’ right across the top of his fresco.

First (in the upper detail), the Devil, Satan—dressed as a religious, but with bat’s wings—is trying to persuade Jesus to change some stones into bread.

Next (in the centre of the whole fresco) he is urging Jesus to cast himself down from the Temple, to demonstrate that his Father’s angels would come to his rescue.

In the lower detail, Satan has just failed in his third temptation (a vision of political power over the whole earth), and Jesus is now hurling him down from the mountain—the Devil’s habit flying off to reveal female breasts, a tail, a great deal of animal hair, and talons.

Behind them, three angels come and ‘minister to Jesus’, as St Matthew says—bringing an incongruously elegant picnic on a nicely laid table. (There is, of course, a deeper meaning—as there is in almost every such detail throughout the Chapel. Here the bread and wine are ‘prefigurations’ of the Institution of the Eucharist later in the cycle.)

In Botticelli’s narrative, the same three angels reappear on the left of the composition, guiding Jesus down from the mountain to witness the scene that dominates the centre of the foreground.

As we shall see in a moment, it is a religious ceremony of immense importance to the argument of the Chapel, a ceremony of ‘handing over’ (traditio).

The High Priest of the Old Order (dressed in full ‘pontificals’, as it were) faces a youthful acolyte (dressed in white) whom we readily understand to be a representative of the New Order.

They stand in front of an altar in front of the Temple of Jerusalem.

And it was of course this Temple which dictated the dimensions of the Sistine Chapel as a whole.

Botticelli modelled his vision of the Temple partly on the façade of the old basilica of St Peter’s (which lay alongside the Great Chapel, as explained in the previous lecture), and partly on the façade of the Ospedale di Santo Spirito, a few hundred yards away, which had been rebuilt by none other than Pope Sixtus (as was also explained in the previous lecture).

The copy is not an exact one. But notice the pediment with its circular ‘rose’, the four pairs of windows, and, below, a larger central arch, flanked by two pairs of lesser arches.

And while we are on the subject of allusions to the pope, we should not miss the oak tree, with its leaves suitably magnified against the sky, referring once again to the family name of Pope Sixtus—della Rovere, ‘of the oak’.

The ceremony we are called on to witness seems to be a recurrent, daily blood-sacrifice (rather than a single historical event). The High Priest, who wears a ‘tiara’ like his papal successors, sprinkles blood onto the blazing altar (from the bowl held by the young acolyte), using a branch of hyssop, wrapped round with scarlet wool, as specified in Leviticus 14:4, 7. (All these and other details were lovingly reconstructed on the best scholarly evidence then available.)

The sacrifice is placed so prominently in order to make two main points.

First, it suggests that Jewish priests had an indispensable role under the Old Law, and further, that a Catholic priesthood has an indispensable role in administering the sacraments.

(There is some tantalising evidence that this acolyte is intended to be Jesus himself, because one of the apocryphal gospels relates that, as a youth, he became a priest at the Temple.)

There is also a clear pictorial suggestion that we are witnessing the transition from the old ritual to a new spirit of ardour and love. This would be in accord with the second main function of the scene, which is to underline the argument of the Epistle to the Hebrews—a crucial text, at that time still attributed to St Paul—which describes at length the relationship between the Old Law and the New Covenant, insisting that the Old Law, which did demand burnt offerings and blood sacrifices, has been made superfluous by the supreme, once-for-all blood sacrifice of Jesus on the cross.

The fresco, then, is freighted with an exceptionally heavy theological cargo.

But we must not neglect the pleasures of what we can see ‘on deck’—the vigour of the girl, hurrying on with a basket of ‘clean living’ hens, for example; or the faces of the witnesses, who are much more involved emotionally in the action than is the norm in all the other frescos—with the exception of the little boy in black, who cannot resist peeping out at the ‘camera’.

On the right of the foreground, do take a moment to enjoy the group with the girl bringing wood for the sacrifice. (It is supposed to be cedar wood, but the leaf is clearly that of an oak.)

Notice a very young, very glum-looking cardinal; the symbolic boy with his symbolic grapes, treading on the serpent twined around his leg; and the girl herself, who is one of Botticelli’s very special ‘nymphs’ or ‘goddesses’.

There are two more superb portraits in the group behind her.

The man with the rod of authority is almost my favourite head in the whole chapel (Michelangelo included). And some say the head of the young Jew is a portrait of Botticelli’s pupil, Filippino Lippi—but however that may be, his eloquent eyes are certainly be touched by an intuition of the ‘New Order’.

We move on now to the ‘Parallel Scene’ from the Moses cycle on the opposite wall.

It too was painted by Botticelli, and it is even more crowded with figures and rapid action.

There are, in fact, no fewer than seven scenes from the early life of Moses; and he appears, always dressed in saffron and green, no fewer than seven times.

All the episodes are narrated in the Second and Third Chapters of Exodus; that is, before the circumcision scene we have already examined.

The action unfolds from right to left, away from the altar, and the biblical story on the right of the fresco runs as follows:

‘One day when Moses was grown up, he went out to his people and looked on their burdens; and he saw an Egyptian beating a Hebrew. He looked this way and that, and, seeing no one, he killed the Egyptian…and hid him in the sand’.

‘When Pharaoh heard of the matter, he sought to kill Moses, but Moses fled and stayed in the land of Midian. And he sat down by a well’.

‘Now the priest of Midian had seven daughters…and they came and drew water, and they filled the trough to water their father’s flock. Shepherds came and drove them away, but Moses stood up and helped them; and he watered their flock’.

We see Moses twice in the detail, first driving the shepherds away, and then watering the sheep by using a very advanced pulley-wheel.

The act of gallantry led to his courtship and marriage of Zipporah, and then to the birth of his son.

In short, the scenes on the right of the fresco explain why Moses fled to Midian, and how he acquired a half-Jewish son; and thus they provide most of the prehistory for the first fresco in the cycle.

The scenes which lie to the top left are those which justify the title of the fresco and establish the link with the ‘Trials of Christ’ on the opposite wall, because the rubric above the picture runs:

The Temptation (= ‘Testing’) of Moses, the Giver of the Written Law.

In this case, however, the agent who administers the ‘Test’ is not Satan, but God himself.

The story (in Exodus 3) goes like this:

Moses was keeping the flock of his father in law; and the angel of the Lord appeared to him in a flame of fire out of the midst of a bush, and lo, the bush was burning, but it was not consumed.

God called to him out of the bush: “Moses, Moses”. And he said: “Here am I”.

Then God said: “Do not come near; put off your shoes from your feet, for the place in which you are standing is holy ground”.

Then God said: “I am the God of Abraham…”

In the rest of the chapter he gives the reluctant Moses his charge, namely, to return to Egypt and to set the Jews free.

The beginning of that journey towards freedom—the ‘Exodus’—is shown in the left foreground, where Moses, now confirmed as a leader and carrying the staff of authority given him by the Lord, walks at the head.

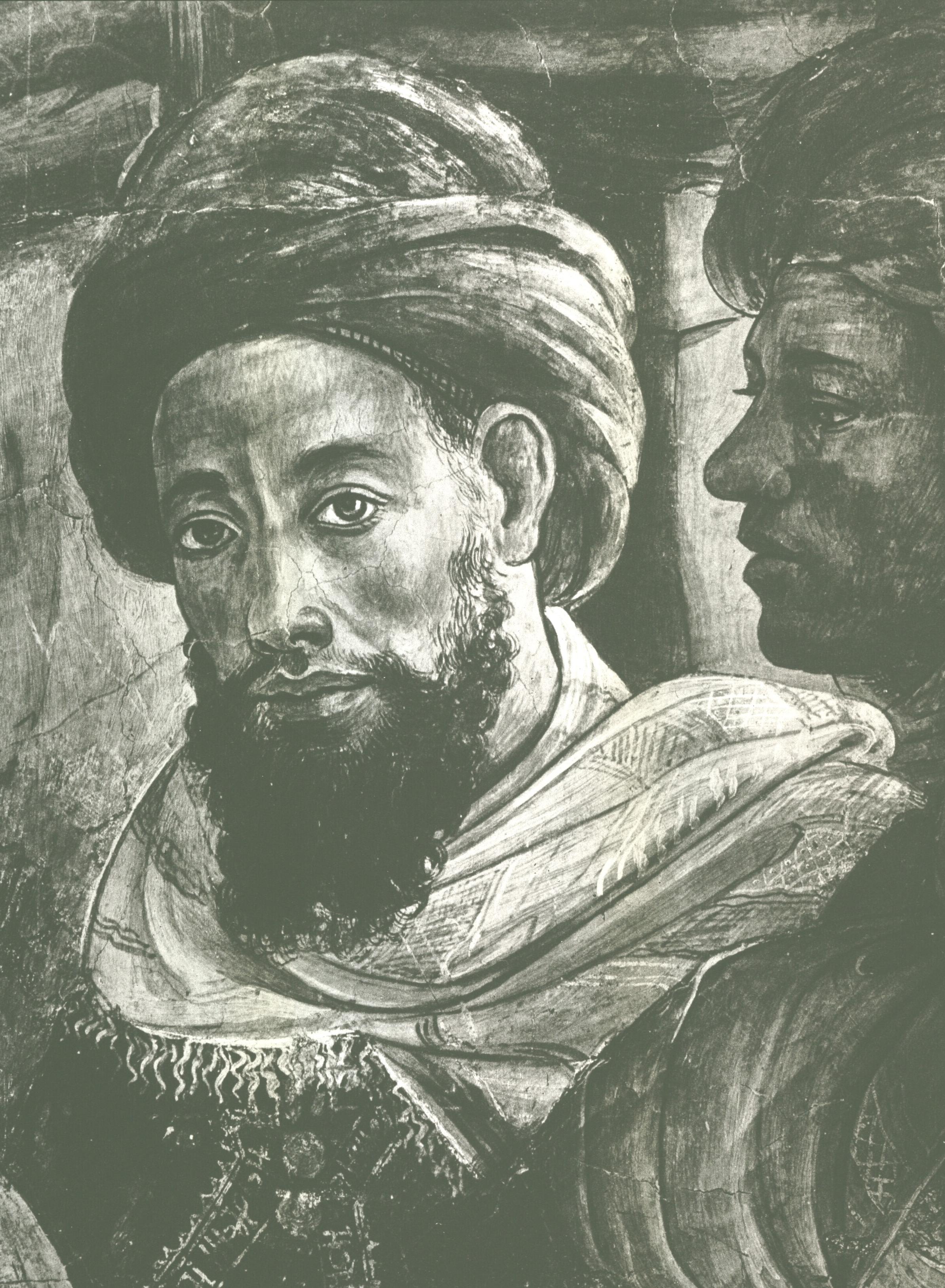

The faces in this area are particularly fine, as you can see in the bearded Oriental man with a turban, and in Moses himself, with those hooded, eloquent eyes.

For the next pair of frescos, it will be convenient to begin by looking at the Moses episode, which in this case is particularly well known.

So let us follow the Israelites on their Exodus (from right to left, as always on this north wall), to the point where they have reached the Red Sea, the Egyptian frontier, and miraculously crossed ‘in the midst of the sea on dry ground’.

They are now gathered on the further shore and are about to resume their journey into the Wilderness.

The artist is clearly not Botticelli.

The story began top right in the tiny scene outside the walled city of Rameses, where Moses obtained his ‘exeat’ from the Pharaoh.

The subsequent forced march, and the miraculous crossing of the Red Sea are recalled pictorially in the column (shown in the water) and the cloud (here turned into a storm cloud), because the Bible specifies that ‘the Lord went before them by day in a pillar of cloud…and by night in a pillar of fire to give them light’.

The main scene on the right of the foreground shows the moment of triumph described in Exodus chapter 14, when the waters of the Red Sea (there can be no doubt about the colour), which had miraculously divided to allow the Israelites to cross over, suddenly flowed together again, and engulfed the 600 chariots of the Egyptian army who were engaged in what would now be called a ‘hot pursuit’.

The painter is the least talented of the four, Cosimo Rosselli (you will have noted how clumsily he represents the eddies in the sea or the cloud formations). But he certainly revels in the depiction of sinking horses and despairing men; and his contribution has many things to enjoy when considered as an illustration of a ‘war comic’.

The immediately intelligible following scene in the same fresco comes from the next chapter in Exodus.

It shows how ‘Miriam, the prophetess, sister of Aaron, took a timbrel in her hand and sang a song of thanksgiving’.

Please focus for a moment, however, on the standing figures on the extreme left, because it is on them we must concentrate if we want to understand the title of Rosselli’s fresco, which is:

The Congregation of the People who are about to accept the Written Law.

(Latin uses an elegant future participle, ‘legem scriptam accepturi ’.)

It may seem a distinctly odd title, but it is scarcely less so than the almost identical one for the corresponding picture in the Christ cycle, which has the title:

The Congregation of the People who are about to accept the Evangelical Law.

Although the stories represented are very different indeed, the two teams have clearly agreed on a strong ‘visual rhyme’ to link the pictures, by allowing the centre of their compositions to be dominated by an expanse of water: the Red Sea, in one case, and the Sea of Galilee in the other.

The artist here is Domenico Ghirlandaio, and this is the only one of his frescos in the chapel to survive.

In the background, in the centre, you can see the Calling of the Apostles.

As he walked by the Sea of Galilee, [Jesus] saw two brothers, Peter and Andrew, casting a net into the sea, for they were fisherman. And he said to them: “Follow me, and I will make you fishers of men”. Immediately they left their nets and followed him.

In the foreground, Peter, resplendent in his traditional yellow and blue (together with Andrew, more soberly attired), kneels to receive this charge in a more ceremonious manner.

(His pose anticipates the later scene—a scene to be crucial to papal propaganda—where Christ gives Simon Peter the two keys.)

This central group is nicely isolated by the open wedge of the Sea of Galilee; and Ghirlandaio does achieve a little poetry in his typical, late-quattrocento landscape.

But perhaps we should dwell instead on the bystanders, who are given such importance in the title of the picture—Congregatio populi—because these onlookers give Ghirlandaio scope for some splendid portrait heads, as you can see.

(Notice however that the grouping of the figures is not so varied as in Perugino; and their emotional involvement in the scene they are witnessing is nothing like as intense as it was in Botticelli.)

We are half way through the cycle now, and it is time for a little revision.

On the south wall, we have looked at the Institution of Baptism, the Trials of Jesus, and the Gathering of the People in readiness to receive the Evangelical Law; while on the north wall (not illustrated) we have seen the Observance of Circumcision, the Trials of Moses, and the Gathering of the People in readiness to receive the Law of Moses.

You may remember from the previous lecture that, in the original layout, the marble screen crossed the chapel at this point on the wall in order to separate the laity from the members of the ‘papal establishment’, who assembled at the altar end of the chapel.

We are ready now for the pair of scenes which were clearly among the most important in the conceptual scheme, and which are undeniably linked together in the Bible: namely, the Giving of the Old Law, and the Giving of the New.

Once again, it will be better to tackle the New Testament scene first.

This fresco is entitled:

The Promulgation of the Evangelical Law by Christ.

The main scene shows Jesus delivering the Sermon on the Mount (or, perhaps, the Sermon on the ‘Mound’).

He is blessing the meek, the poor and the humble, and he is pronouncing the Beatitudes which embody the new law of love.

In the area of the foreground to the right, Jesus is seen for a second time in the scene of the Healing of the Leper (who is suitably ‘scabby’, as you see in the upper detail)—this being the only one of Christ’s miracles to be represented in the Chapel.

The fresco is by Cosimo Rosselli again, as you will have guessed from the elongated proportions of the human figures, if nothing else.

There is little that requires comment.

He does what the Pope required of him; and he does it competently. Do not miss, though, the clear differentiation of the main groups—the intentness of the seated women and the more animated discussion among the apostles behind.

In the lower detail you should register the no less symbolic sun (rising over a run-of-the-mill landscape); the walled and turretted township, nestling on the hillside with a plethora of gloriously anachronistic gothic spires; and the huge birds in the sky. (They would have to be pterodactyls at the implied distance, but Rosselli is not hampered by any rigid respect for the new principles of geometrical perspective. Nor indeed were the other three teams.)

Rosselli is also the artist in the complementary scene on the south wall, entitled:

The Promulgation of the Written Law by Moses.

Considered as a composition, the fresco is more than a bit of a muddle—although Rosselli does preserve the normal foreground ‘frieze’ of almost life-size human figures, and he rhymes the central mountain with the one in the fresco opposite, just as he had the Red Sea with Ghirlandaio’s Sea of Galilee.

The children of Israel are still in the Wilderness (you can see their bell-tents in the campsite on the left). The mountain is, of course, Mount Sinai.

Moses climbed the mountain three times in all. The first ascent (described in chapters 19 and 20 of Exodus) culminated in his hearing the Ten Commandments.

What we are shown in the upper part of this fresco is the second occasion, described in chapter 24, when the Lord summoned Moses to him, saying: “I will give you tables of stone with the Law and Commandment”. (In other words, he was giving the written law, the lex scripta.) ‘And the glory of the Lord settled on Mount Sinai like a devouring fire; and Moses was upon the mountain forty days and forty nights, accompanied only by Joshua’.

The Lord then ordered the sons of Levi to kill the idolators ‘and there fell of the people that day about three thousand men’ (upper detail).

After that, Moses pleaded with the Lord for mercy for his ‘stiff necked people’, and the Lord ordered him to climb the mountain for a third time, taking with him two tables of stone, on which the Lord wrote the Law once again with His own hand, and ‘renewed His covenant’.

With this, we come to the final episode within the same fresco (in its proper place, on the left of the composition, and therefore furthest from the altar) which shows the moment of Moses’ return.

‘When Moses came down from Mount Sinai with the two tables of the Testimony in his hand, he did not know that the skin on his face shone because he had been talking with God, and all the people of Israel were afraid to come near him’.

Notice how the standing woman and the kneeling man are shielding their eyes from the radiance.

The next pair of frescos are the most political and polemical, and the most closely connected with papal propaganda in a period when (as we noted in the first lecture) the supreme authority of the popes was being challenged by another ‘stiff necked people’, in the form of Northern Conciliarists and proto-Protestants.

The titles speak explicitly of a ‘challenge’, a ‘threat’, a ‘conturbation’—as you can read in the title over the fifth fresco in the Moses cycle (on the right of the pair in this photograph).

In the first scene (where it belongs, on the right of the composition on the Moses wall) a party of Jews, who want to return to Egypt from the Wilderness, try to kill Moses by ritual stoning.

(The story is told in chapter 14 of Numbers, verses 6, 9 and 10.)

As the detail shows, Moses is repeating the violent gesture he made when breaking the Tablet of the Law, while Joshua (in yellow and blue) tries to restrain the young Jew, as required in the text.

(He has plucked the stone from the right hand of the assailant; but there are still two other stones visible, one of them being gripped with particular savagery.)

The scene in the centre is a direct challenge to the priesthood—an attempt by unconsecrated laymen to usurp the powers vested in Aaron and the sons of Levi.

A man called Korah, and two brothers, called Dathan and Abiram, accuse Moses of deceiving them and of making himself a ‘prince’ over them, ‘exalting himself and Aaron above the assembly of the Lord’.

Their rallying cry is: ‘All the congregation are holy’ (they are, we might say, the proto-Congregationalists or proto-Quakers).

Moses orders them to appear before the Tent of Meeting, commanding everyone to take his censer, and to put incense on it. The censer belonging to the High Priest, Aaron, swings out freely, but the unsanctioned use is punished by the Lord, who scatters the rebels with emanations of power from Moses’ rod.

(Particularly vivid is the detail of the leader’s head, he being unable to cling on to his twisting thurible.)

Having isolated the rebels in their pavilions, Moses demanded a special death for them as a sign of the Lord’s anger.

‘And as he finished speaking…the ground under them split asunder and the earth opened its mouth and swallowed them up…. and they went down alive into the pit’ (16:31); except the two sons of Korah, who were saved, and are shown standing on a cloud (26:10).

The ‘parallel’ fresco on the opposite wall is by Perugino.

The title again speaks of a ‘Conturbation’; and the diminutive figures in the middle of the vast piazza are engaged in two distinct challenges to Jesus, one on the left and one on the right.

Let us deal with these two background episodes first.

The second episode is a more sophisticated attempt to embroil Jesus with the Roman authorities.

It is the story of the Tribute Money (reported in Matthew chapter 17), where Jesus asserts that, strictly speaking, he is under no obligation to pay taxes to an earthly ruler, but then immediately proceeds to conjure up a coin—not ‘out of a hat’, but from a fish’s mouth—in order to satisfy the tax collector of Capernaum.

The challenges to Jesus are clearly less important than those massive symbols of Roman authority represented by the buildings, which gain in impact thanks to the fully developed system of perspective.

We know they must be colossal because of the scale supplied by the human figures and because the correct, proportionate ‘diminution’ of the horizontal lines between the paving stones enable us to measure the distance from the foreground.

Perugino’s vision of the Temple in the centre is modelled not on Old St Peter’s (or on the hospital of Santo Spirito), but on the typically octagonal baptisteries of the New Evangelical Law, and—more specifically—on Brunelleschi’s cupola for the cathedral of Florence and on the façade of the Roman Pantheon (alias Santa Maria Rotonda), which we glanced at in the first lecture of this series.

Perugino’s Temple is flanked by no fewer than two triumphal arches, making a double rhyme with Botticelli’s arch on the opposite wall, and carrying, between them, a single even more important inscription, celebrating Pope Sixtus IV and asserting one of the main themes of the Chapel.

The inscription takes the form of a Latin elegiac couplet, with the hexameter on the left and the pentameter on the right.

Put together, the two inscriptions read:

Immensum Salomonis templum tu hoc quarte sacrasti, Sixte, opibus dispar, religione prior.

You consecrated this immense temple of Solomon, oh fourth Sixtus, in wealth unequal [to Solomon], but before him in point of religion.

The whole of the foreground is occupied by the scene of Christ giving Peter two enormous keys, illustrating the famous word-play and metaphor (Matthew 16) used by Jesus when Peter had for the first time recognised him as the ‘Son of the Living God’.

‘You are Peter (Petrus), and on this rock (super hanc petram) I will build my Church. I will give you the keys to the Kingdom of Heaven, and whatever you bind in earth shall be bound in Heaven, and whatever you loose on earth shall be loosed in Heaven’.

As we have noted several times, the popes claimed that this supreme power was vested in the unbroken line of Peter’s direct successors, and only in them.

Hence, the biblical word-play might be described as the QED of the papal ‘theorem’. And that is why the claim is given such prominence in the pictorial layout, and why the figures of Jesus and Peter are given such weight by the Roman architecture behind them.

Remember, too, that the fresco occupies a dominant position in the west half of the Chapel, directly over the place (marked on the floor) where the pope would be enthroned during a service, as you can see in the miniature.

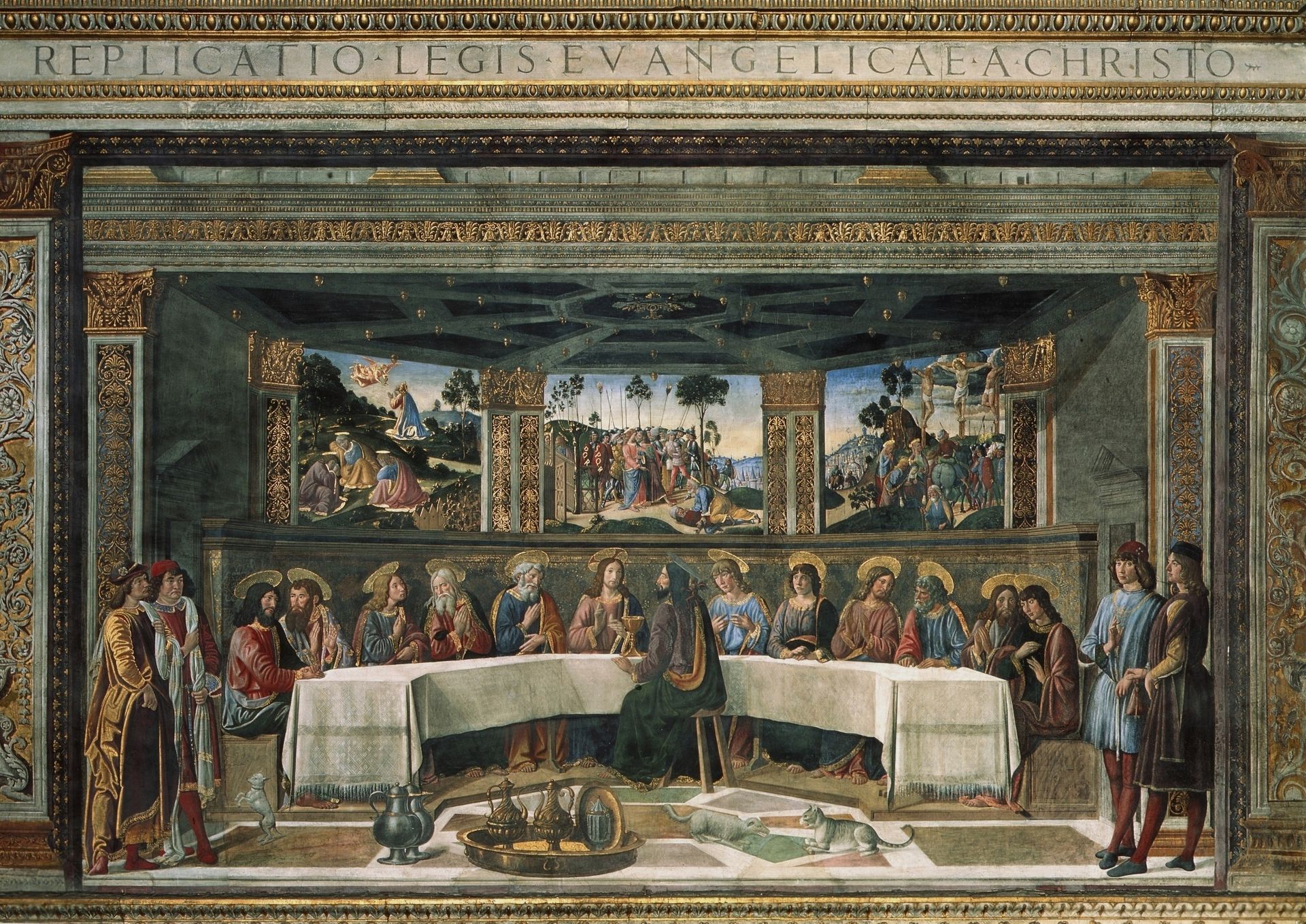

The last surviving fresco in the Christ cycle is quieter.

It is by Cosimo Rosselli (as you might easily infer from the proportions of the young men standing on the right).

The Latin titulus is easily legible above the fresco. Literally translated, it runs:

The Replication (Reiteratio) of the Evangelical Law by Christ.

The reiteratio occurs, as you can see, during the Last Supper. The artist has been instructed to combine two moments in the Gospel narrative when Jesus first breaks bread (‘Take, eat, this is my body’) and then offers a cup of wine to his disciples: (‘Drink of it all of you; for this is my blood of the covenant, which is poured out for many, for the forgiveness of sins’).

(It is worth recalling that Jesus and the disciples had met in the upper room of an inn to celebrate the Jewish Passover, the central feast of Judaism, observed by Jews since the time of Moses; that his two commands here initiated the central feast, the central communion, of the New Order; and that many of the fiercest theological disputes between Protestants and the Papacy would turn on the precise meaning of the words: ‘This is my Body’ and ‘This is my Blood’.)

The fresco is simply following the traditional iconography for a Last Supper by placing the traitor, Judas, on our side of the table (black-bearded, green-haloed, with a diminutive devil at his back). But Rosselli has, most unusually, used the three windows in the room to remind us of the following scenes in the sacred drama.

The montage shows the the Agony in the Garden, the Betrayal and Arrest, and, on the right, the Crucifixion, the blood sacrifice that rendered all the Jewish sacrifices superfluous.

In the main scene on the right, then, Moses is enthroned in the open air, on a very low mound, holding his staff of authority in his left hand, while he reads out the written law (as he did on several occasions, according to the Book of Deuteronomy).

At his feet is a chest (the ‘Ark of the Lord’) with its lid open to display the original Tables of the Law, graven on stone (which the Ark had been constructed to preserve).

(The Ark also displays a gold cup, containing the Manna, prefiguring the chalice in the Last Supper).

The audience, with whom we (the faithful laity) are meant to identify, include three very striking figures: the old man, listening intently; the young mother, suckling her baby; and, most remarkably, the classical nude, who represents the ‘Stranger in the Midst’ (that is, a non-Jew), allegorically interpreted as a ‘Figure’ of the Church of the Gentiles.

In the background, very high (on a mountain not a mound, as you can see in the lower detail), an angel is showing Moses a glimpse of the Promised Land, where he will never set foot. He is shading his eyes and leaning quite heavily on his staff . He has carried out his charge.

When he has descended (in the major scene in the left foreground), he hands over his staff of authority to the kneeling Joshua (as Christ would hand the keys over to Peter).

In the final, diminutive, background scene, Moses has died and been laid out in his shroud for burial in a valley in the land of Moab.

Before he was buried, however (according to a later legend), there was a struggle for his body between the Devil and the Archangel Michael. This is the subject of the adjoining fresco (on the altar wall) which was originally executed by Signorelli, but was completely repainted after damage in the sixteenth century.

The same fate befell its companion on the other half the same wall (a Resurrection and Ascension, originally by Ghirlandaio).

We do not know what the Latin titles were, and I will not attempt to offer any commentary on the two sixteenth-century frescos (outrageously different in style) which we see today.

Instead, you are invited to ‘revise’—to ‘see again’—the west end of the chapel, where our tour began.

Continue to ignore the vault, but let your eyes work their way down the walls, from the fictive statues of the popes beside the windows, to the Latin tituli over the first three narratives in each of the Parallel Lives, and, last not least, the elaborate spirals in the inlaid patterns on the floor.

Remember: everything is ‘bursting with information’.