I am going to begin this series with a true story.

I was flying across Canada some years ago, sitting in an aisle-seat reading, when the man across the gangway caught my eye as I looked up, and asked if I was an ‘engineer’ (I looked honoured, but blank), and specifically a computer engineer (I looked even more honoured, but even more blank).

When I asked him why he thought I might belong to his profession, he pointed to the open page in my book and said he had taken it for a ‘circuit diagram’—something ‘bursting with information’.

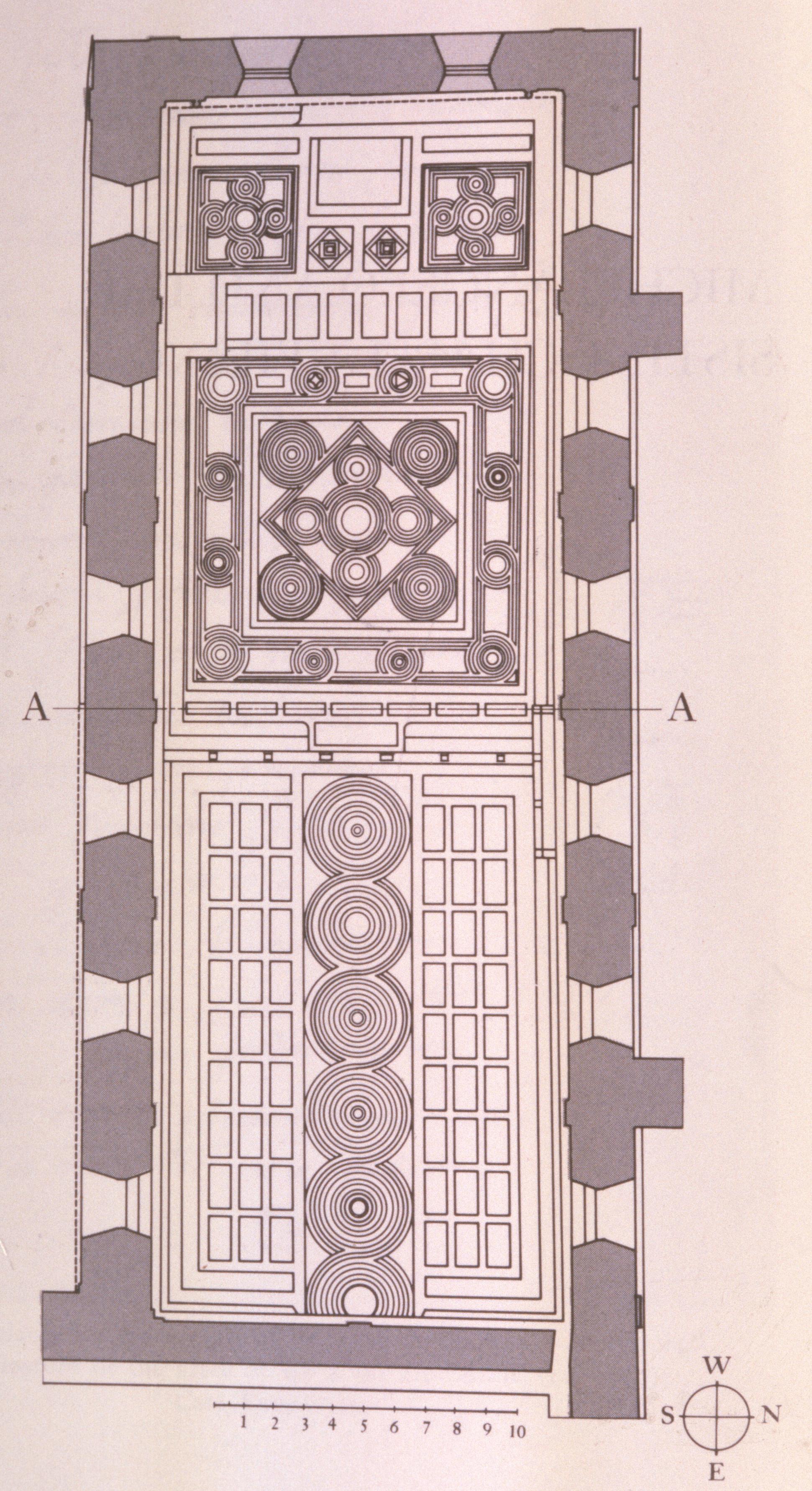

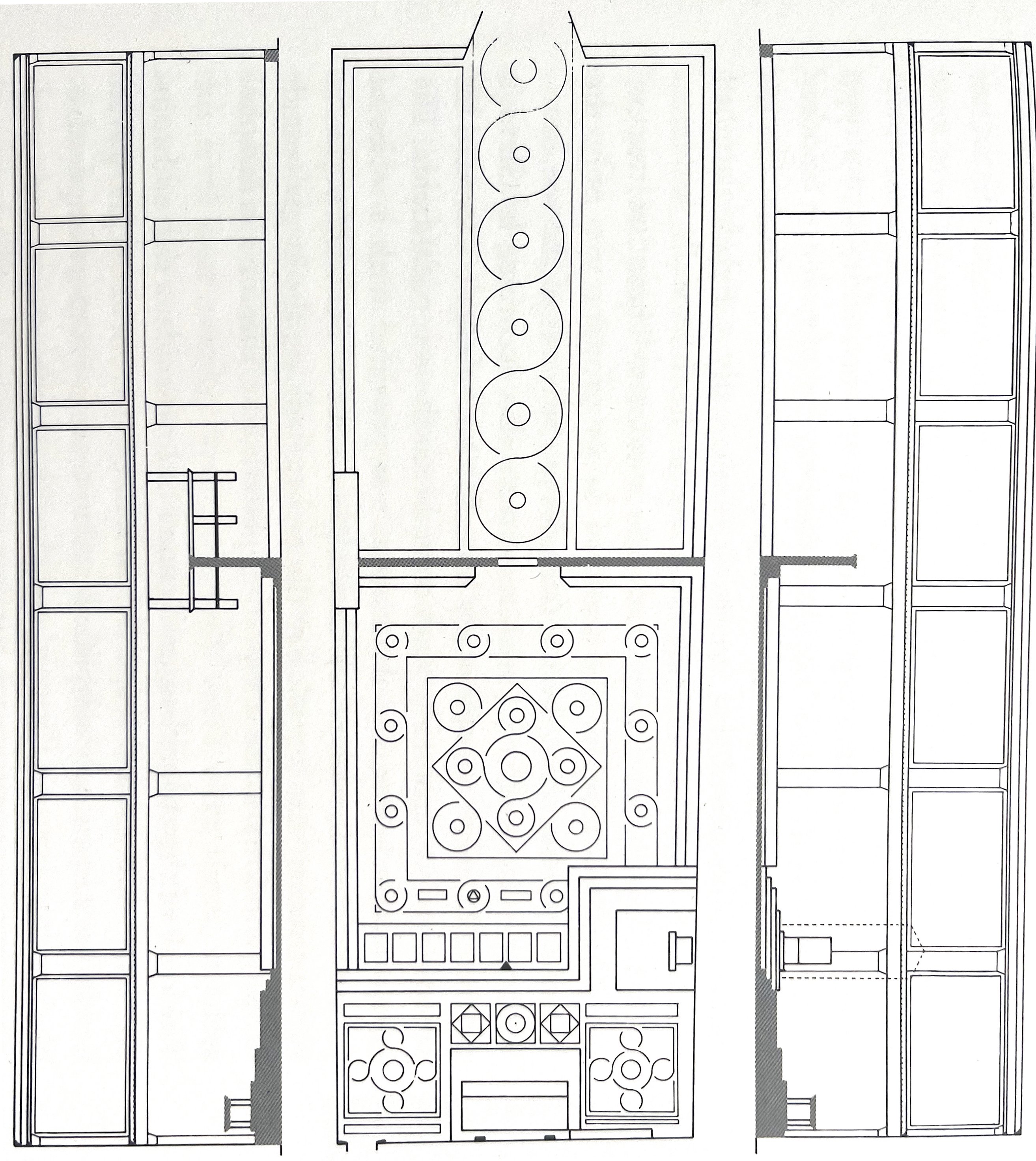

I was absolutely delighted, because the diagram represents the pattern on the floor of the Sistine Chapel (half of which you can see in the photograph here).

And it happens to be true that everything in this chapel is ‘bursting with information’—even the floor—once you have mastered the code and learnt the basic vocabulary.

As you may well know from first-hand experience, the impact of the frescos on the ceiling and walls—with all those hundreds of life-size and over-size figures—is almost unbearably overpowering and confusing.

So our first task is to grasp in outline the six main elements in the design. (Please do not make any conscious effort to retain the details in the following, rapid survey. The names, dates and titles will be summarised for your convenience in a Table in a moment or two and fleshed out in the other lectures in this series.)

Running along the centre of the ceiling, and in the sloping corners, there are stories from the Old Testament painted by Michelangelo.

These narrative paintings are framed on the lower parts of the vault by twelve marble thrones (five on each side, and one at each end). Each throne is surmounted by two male nudes and occupied by a gigantic prophet or sibyl. These too were painted by Michelangelo.

(Confine your gaze to the five thrones along the lower line of this worm’s-eye-view photograph, where the figures are the right way up.)

The triangular spandrels and the lunettes above the windows depict the Ancestors of Christ. Once again, they are by Michelangelo.

Immediately underneath the lunettes, alongside the windows, we find the work of earlier painters.

These are imaginary statues of the first thirty canonised Popes (from the time of St Peter to the conversion of the Emperor Constantine). They are clad in full ‘pontificals’, complete with papal tiara; and they stand within fictive niches, whose rounded arches are occupied by a shell-motif.

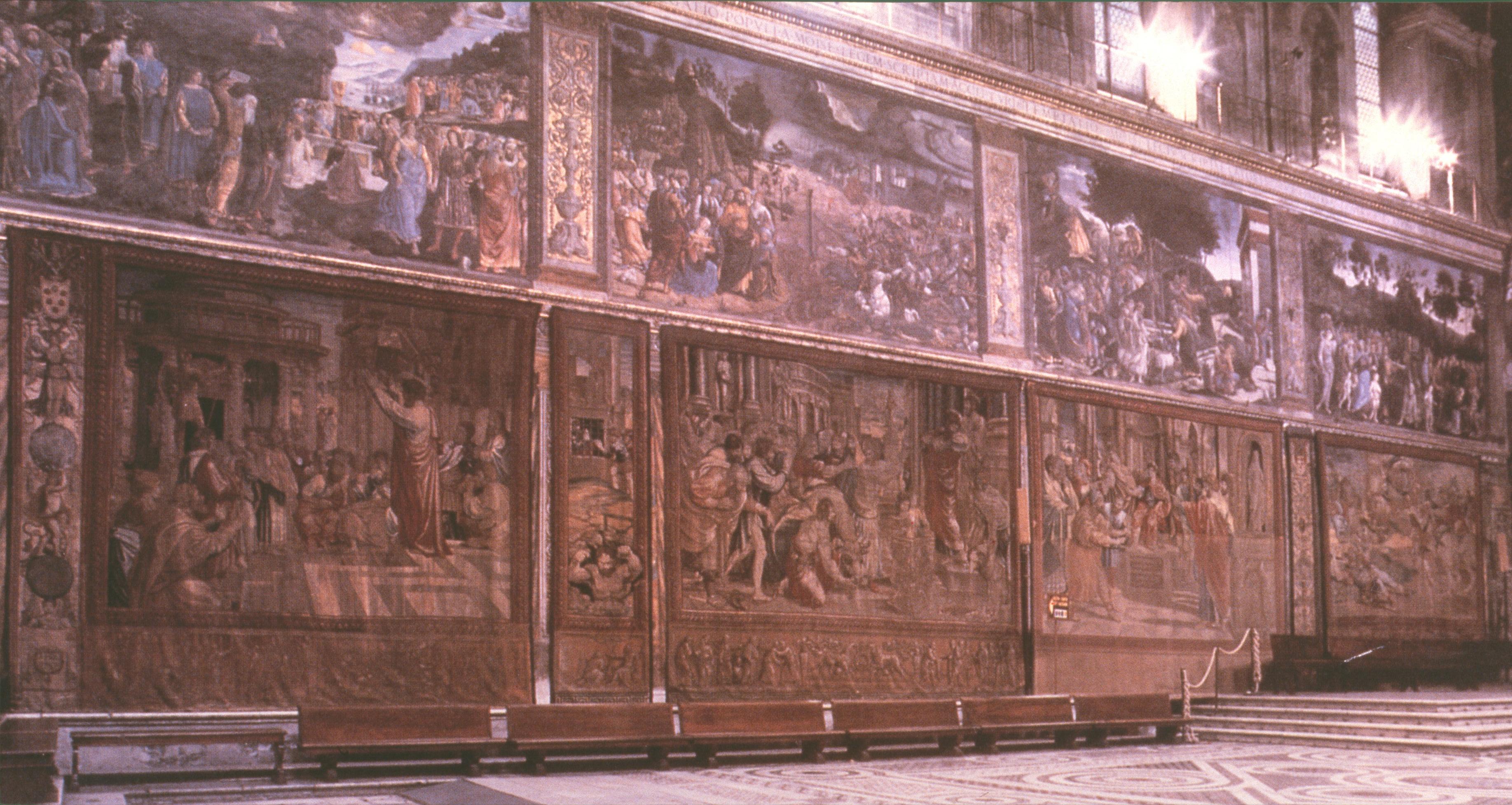

Below the popes are two complex narrative-cycles devoted to parallel scenes in the Life of Christ, (visible in the upper photograph) and in the Life of Moses (visible in the lower).

There is a gap of about fourteen feet between the floor and the Lives of Moses and Jesus, and in this area the wall is painted to simulate curtains or hangings which are framed by fictive pilasters, decorated with grotesque motifs.

These fictive features are what you will see when you visit the Chapel as a tourist on a normal day (if the crowds allow you to see anything at all at ground-level).

But on major feast days, the area was intended to be covered by real tapestries, woven to designs by Raphael, telling the stories of St Peter and St Paul. It is these tapestries that you are shown in the photograph.

(As you can see, and as you would expect, the tapestries of the Acts of the Apostles are matched in their proportion and design with the frescos of the Parallel Lives above them.)

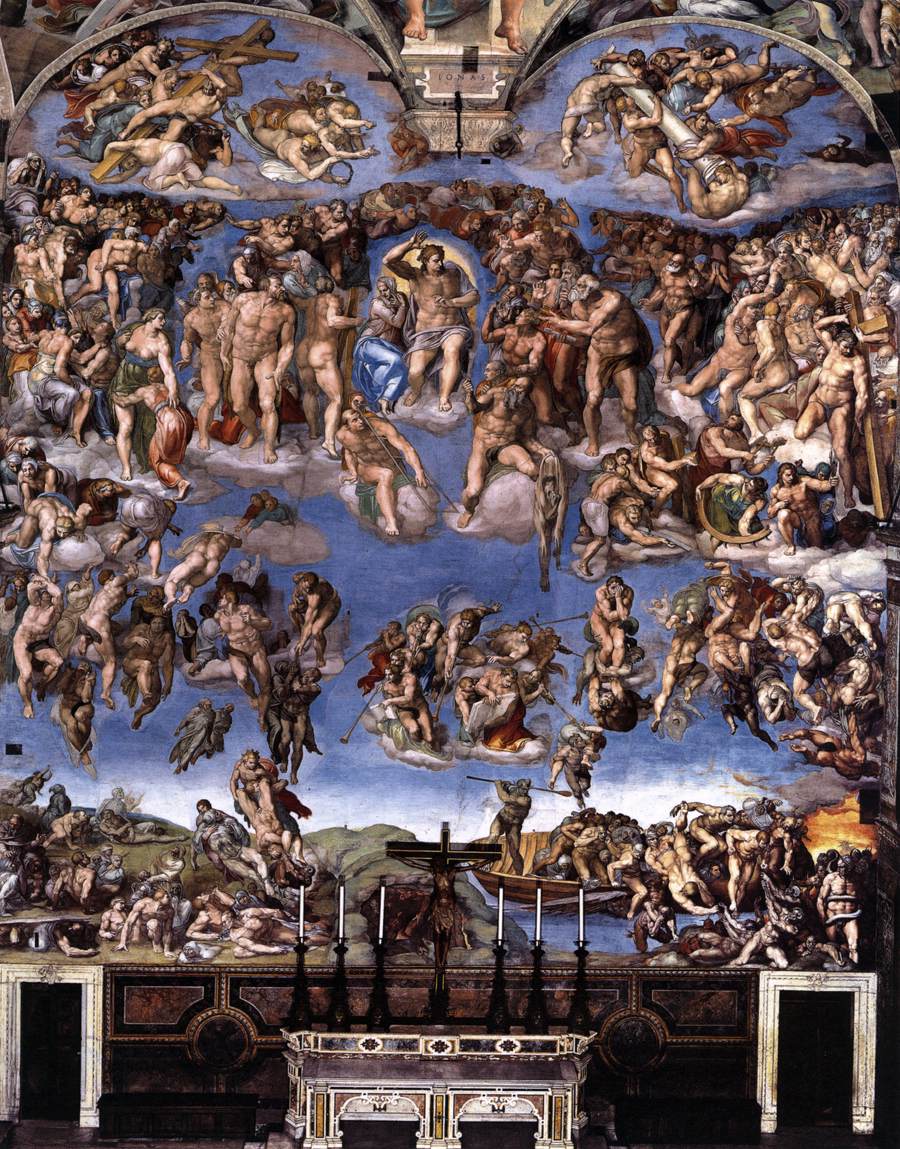

Finally, on the altar wall, comes the most notorious ‘afterthought’ in the history of European Art.

The existing Ancestors, Popes, Parallel Lives and fictive Tapestry on the altar wall were obliterated when Michelangelo returned after an interval of twenty-five years to paint the Second Coming of Christ on the Day of Judgement—the single, pulsating fresco which dominates and dwarfs every figure on the other three walls and almost eclipses his own earlier work on the vault.

On the next page you will find a Table summarising the information with which you have just been bombarded.

(The ‘bombardment’ is not casual. It is intended to make you appreciate the force of a vulgar but expressive two-word reaction to the first impact of the Chapel, uttered by a young American Rhodes Scholar who was visiting the monuments of Europe with an ‘Under 26-Seven-Day-Travel-Anywhere’ rail ticket in the company of my eldest son: ‘Total Mind-fuck!’)

Please do no more than register the layout, key names and key words at this point, and return to the Table at your convenience whenever you feel the need to revise.

Main Elements of Christian Iconography in the Sistine Chapel

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Area | Periodisation and Kind | Subject of the Frescos | Artist | Date of execution | |

| 1 | Centre of Ceiling | Narratives from the Beginning to the First Turning Point |

Creation—Fall—Noah | Michelangelo | 1509–13 |

| 2 | Lower ceiling | Prophecies of the Main Turning Point |

Prophets and Sibyls | Michelangelo | 1509–13 |

| 3 | Wall above windows | Genealogical

links to the Main Turning Point |

Ancestors of Christ | Michelangelo | 1512–13 |

| 4a | Wall beside windows | Institutional

links (ex officio) from the third to fourth Turning Point |

Popes AD 34–330 | Perugino, Botticelli | 1481–85 |

| 4b | Wall below windows | Narratives of the Main Turning Point and its Prefiguration |

Parallel Lives of Jesus and Moses | Perugino, Botticelli et al. | 1481–85 |

| 5 | Lower wall | Narratives of the Third Turning Point |

Parallel Acts of Peter and Paul | Raphael | 1516–21 |

| 6 | Altar Wall | The Day of Judgement | Michelangelo | 1534–41 | |

You are facing quite a challenge in the remaining lectures of this series. It is a tall order. You thought you had agreed take part in a Marathon and realise you are being asked to climb Mount Everest.

There are four sequences of figures (popes, ancestors, prophets and slaves), four cycles of narrative paintings and one cataclysmic ‘closing ceremony’. They were executed by at least seven artists, working for four different popes over a period of six decades.

Nevertheless, all the images in the Chapel (whether they be representational, dramatic or narrative) can be fully enjoyed only when they are understood as parts of a single, complex statement—a single affirmation of the authority of the Bishop of Rome in a very troubled period.

Conflict was already simmering in the middle of the fifteenth century, during the lifetime of Pope Pius II (the subject of the final lecture in the Siena series).

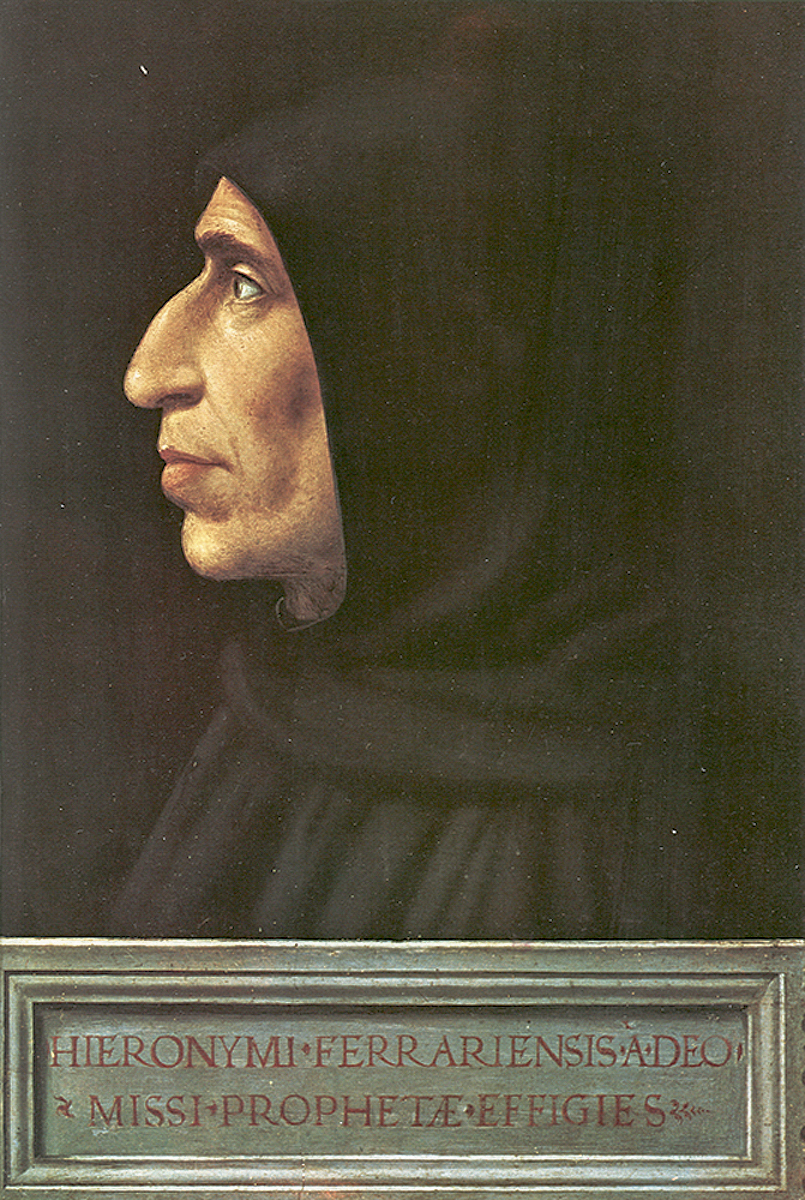

It began to boil and bubble at the time of the confrontation between Savonarola and Pope Alexander VI in the 1490s.

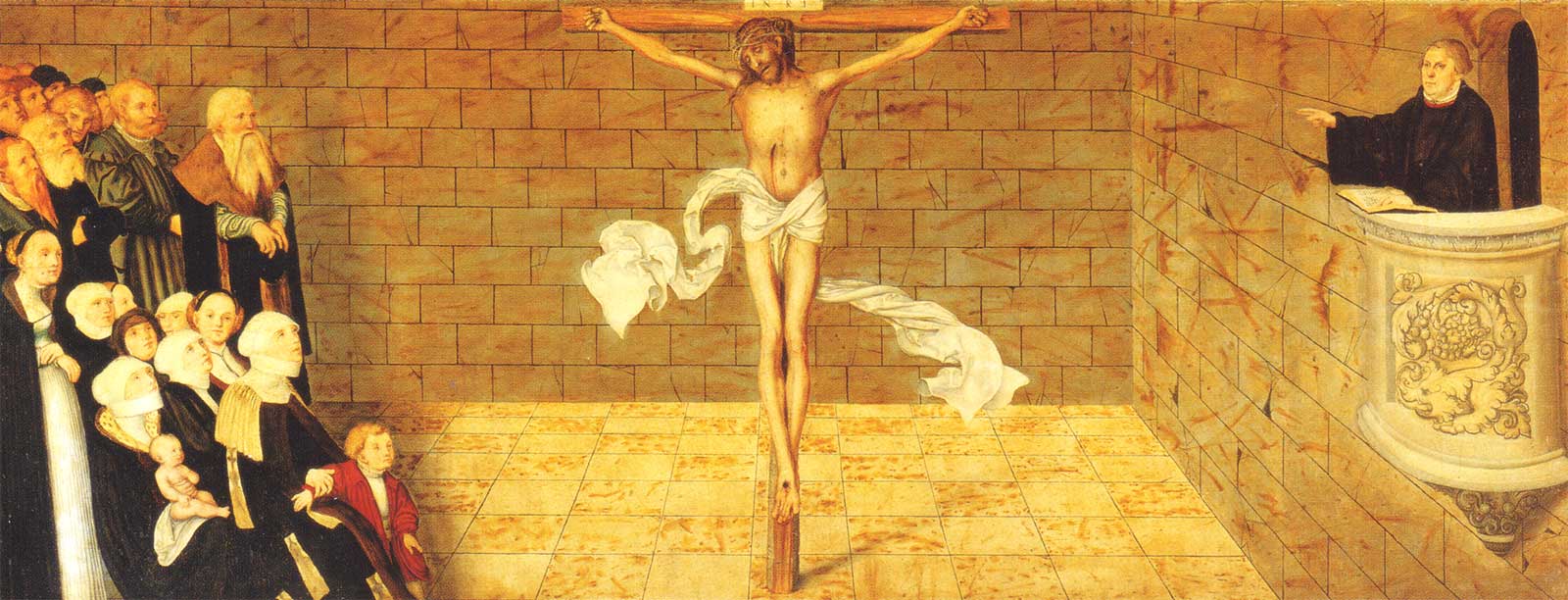

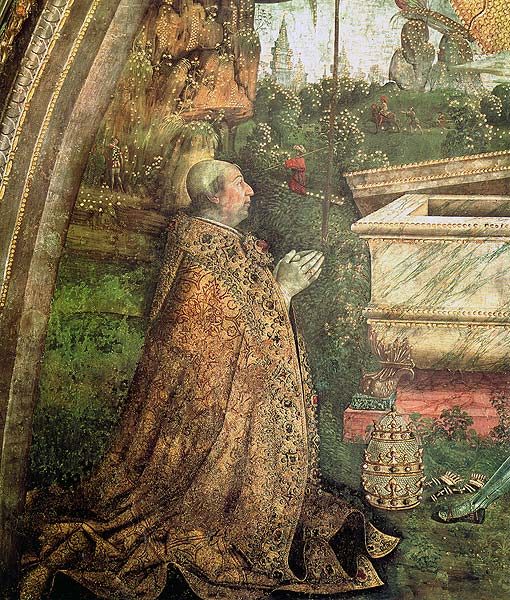

The pot would finally boil over (or, better, the smouldering volcano would finally erupt) in the early years of the sixteenth century, which witnessed the start of the struggle between the forces embodied in the two men whom you saw on the opening page, the men who have come to symbolise the Reformation and the Counter Reformation respectively: Luther (as seen by Cranach), and Paul III (as seen by Titian).

For the rest of this lecture I shall be trying to make you aware of the most important contexts which ought to govern our deciphering of the messages encoded in the Sistine Chapel.

As a first step, I show you three photographs.

The first enables you to relate the inside of the building to the outside.

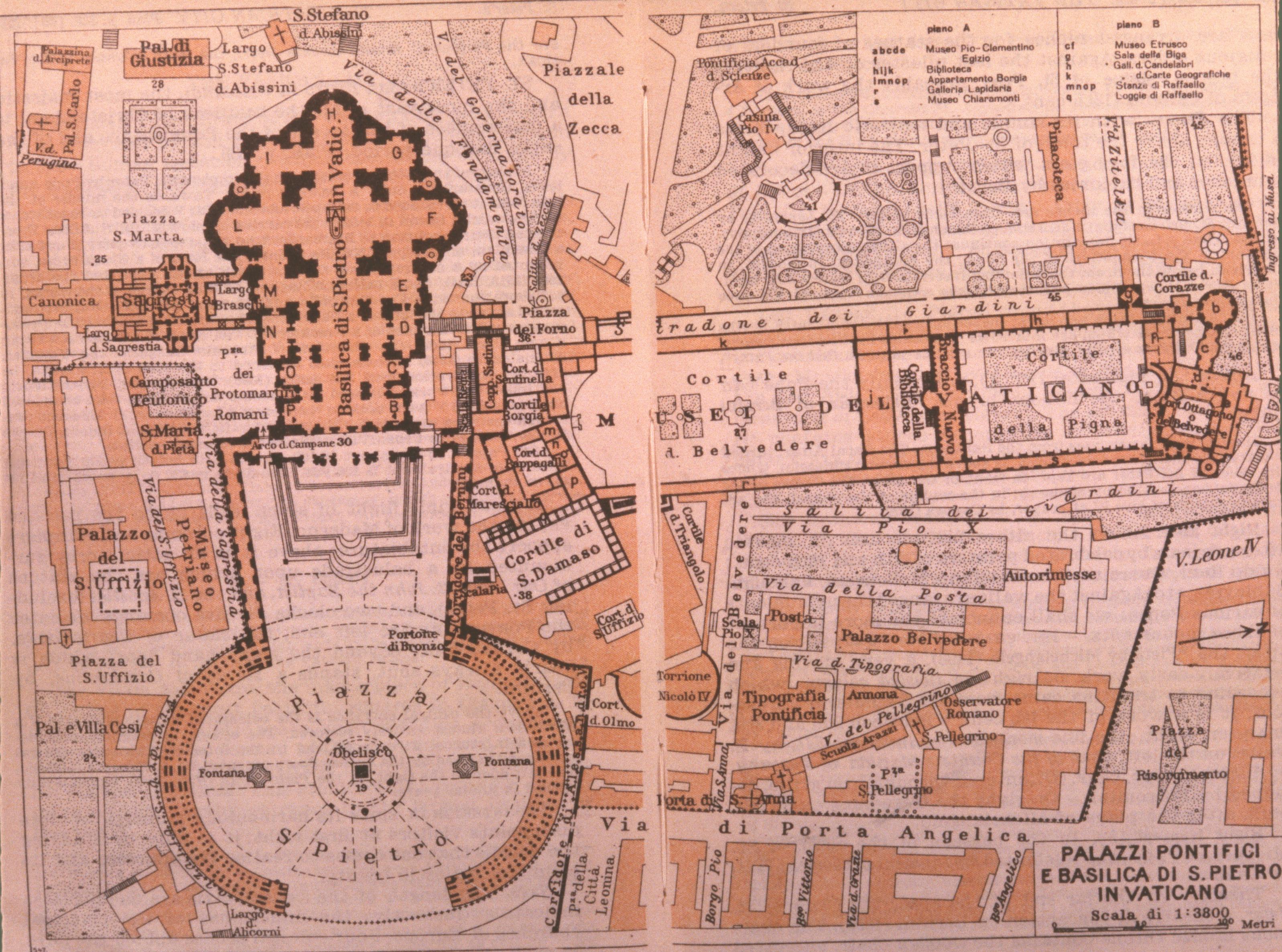

The second allows you to visualise the place of the Sistine Chapel among the courtyards that make up the palace of the popes on the north flank of St Peter’s.

The third invites you to think about the place of St Peter’s within the city of Rome.

Rome is both the physical environment of the chapel and also the embodiment of the most important myth it is trying to express.

The two buildings in the photographs have come to symbolise the two components of that myth.

The Colosseum, begun under Nero in the first century, is the largest and most famous monument of Imperial Rome; while St Peter’s is the largest and best known monument of Christian Rome.

We must bear in mind that, to a man like Dante writing in the early 1300s, it had seemed clear that the city of Rome had been destined by God, in two separate ordinations, to be the ‘head’ of the whole world—caput mundi, the world ‘capital’.

For him, it was the divinely appointed seat of the Emperor, who was to be the supreme arbiter of temporal affairs; and the divinely consecrated seat of the Primate of the ‘Catholic’ or ‘Universal’ church, who had supreme responsibility for the spiritual well-being of mankind.

Obviously, I cannot even begin to sketch the complex relationship between Empire and Church—or between rhetoric and reality—in the thousand years that lie between the conversion of Constantine (when Christianity became the official religion of the state) and the time of Dante. But for our purposes, it is probably enough to remember three main points:

- more often than not, the relationship between the two supra-national institutions was one of conflict and tension, rather than the harmony postulated by Dante—especially when the popes laid claim to supreme authority in temporal affairs as well;

- the city of Rome was relatively prosperous and was expanding during the later twelfth and thirteenth centuries, when the power of the papacy was at its height;

- the fourteenth century, however, saw the weakening of both institutions, the virtual severing of their ties with Rome, and the economic decline and stagnation of the city.

But the buildings of the past—or their ruins—remained; the myth lost nothing of its power; and the story of Rome in the period that concerns us—1450 to 1540—is the story of the return of the popes to the city, a vast programme of rebuilding and new building in emulation of the ancient monuments and churches, and an attempt to combine the two components in the myth of Rome—the Imperial and the early Christian—into a single symbol of the pope’s claim to possess universal authority.

Geographically, Rome lies in a coastal plain (much of it then ill drained), with a hinterland of not very fertile hills and mountains.

It has no port, unlike Venice or Genoa; and its only advantages are that it lies in the very centre of Italy, at a convenient crossing point of a major river, the Tiber, which runs essentially from north to south.

After another one thousand years or so, in or around 1400, historians estimate that the population had shrunk to a mere 25,000.

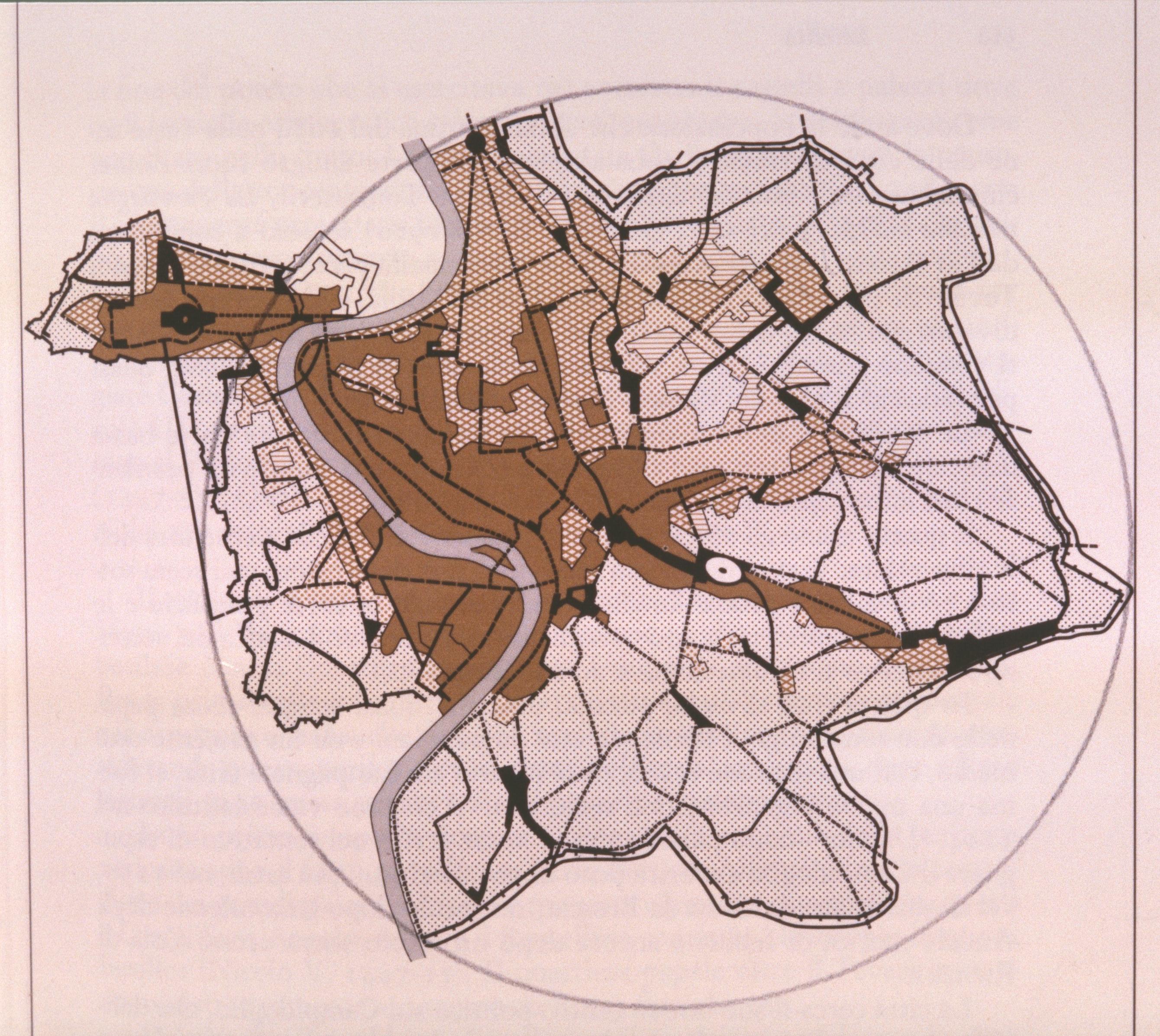

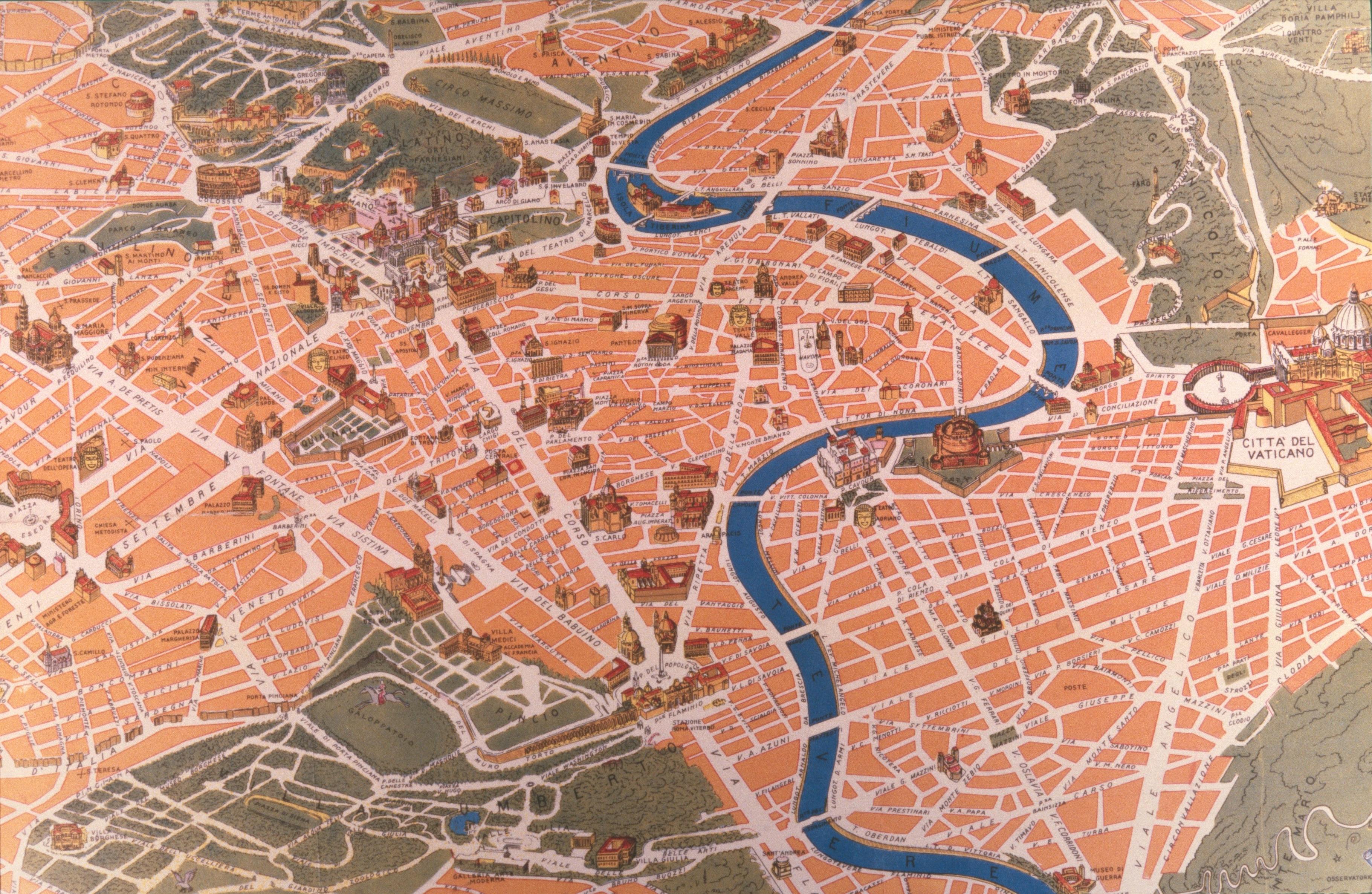

They drew their water from the river once again, and lived in typical medieval streets in the three zones coloured in brown in this map: that is, on the flat ground between the hills and the river; ‘across the Tiber’, in the area still called ‘Trastevere’; and also, further north on the same side, within the ninth-century wall that enclosed St Peter’s.

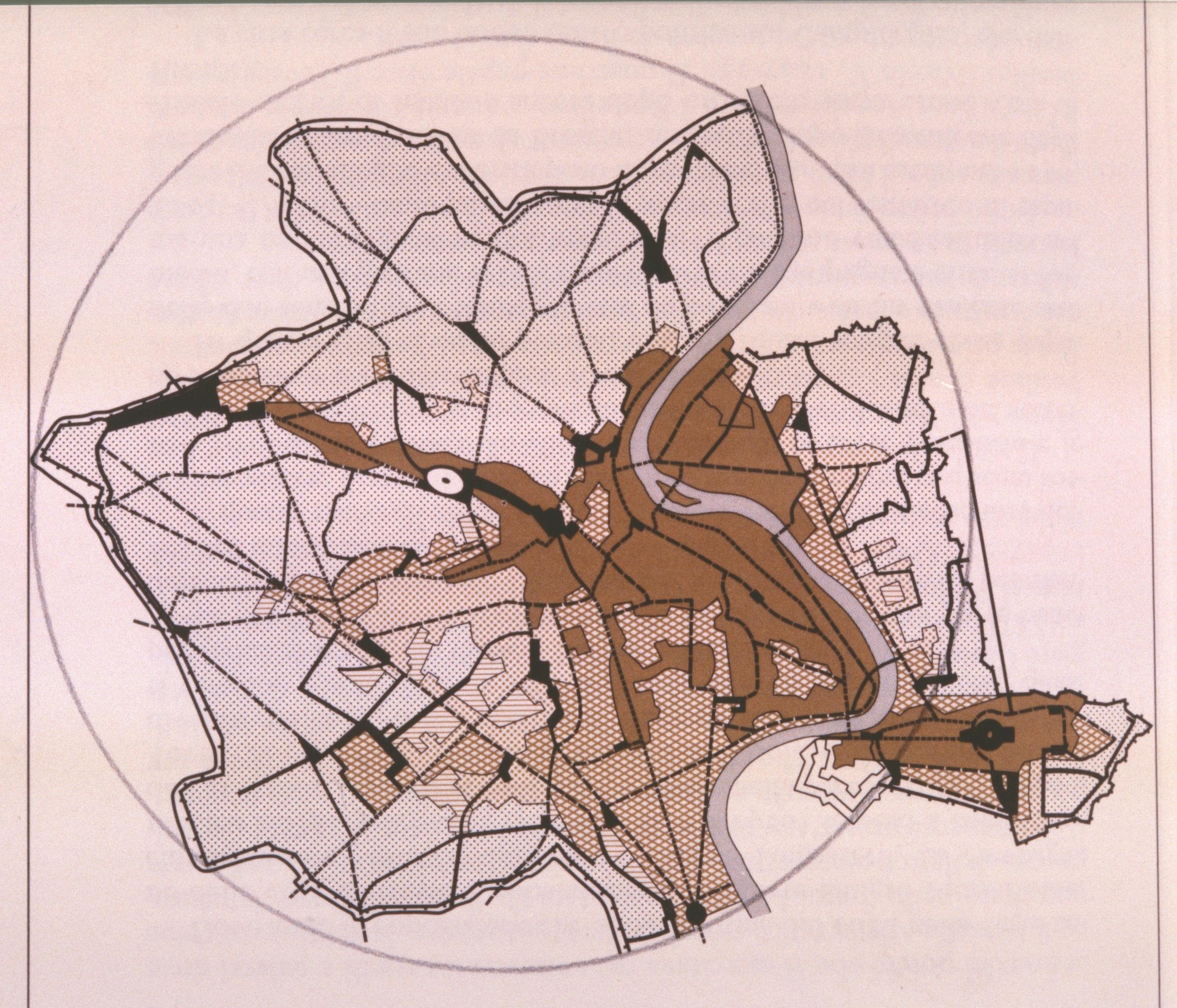

I show you the same map upside down—that is, with south at the top and Trastevere on the right.

This is the way you would see Rome as a pilgrim coming from the north, and this is how the fifteenth-century maps were drawn.

Notice that the shape of the whole does not change all that much, because it all fits rather snugly into the circle I have added to the map, centring the point of my compasses near the Forum.

To drive the point home, I repeat the fifteenth-century image, placing it on the same page as part of a modern tourist plan.

This, too, is drawn in perspective; this, too, places south at the top; and this, too, includes little stand-up buildings, like the houses and hotels on a Monopoly board.

When it is the right moment, you will enjoy the chance to identify the relative positions of the most famous classical monuments, which still strike the imagination of modern tourists with the same force as they struck the barbarian pilgrims whom Dante evokes in a famous simile (Paradiso 31, 31).

When you return to this lecture, you will find it instructive and enjoyable to pick out Castel Sant’Angelo and its bridge;

the Pantheon and the column of Marcus Aurelius;

the Capitoline Hill, the Colosseum and the Arch of Constantine,

the Aurelian wall and the aqueducts.

Without regard now to their relative positions, let us enjoy a quick review of the most important surviving monuments, since they still symbolise so much of the majesty that was Rome and the splendour of classical civilisation.

The enormous Castel Sant’Angelo, topped by its ‘holy angel’, was originally built by the Emperor Hadrian in the first half of the second century AD, as his mausoleum.

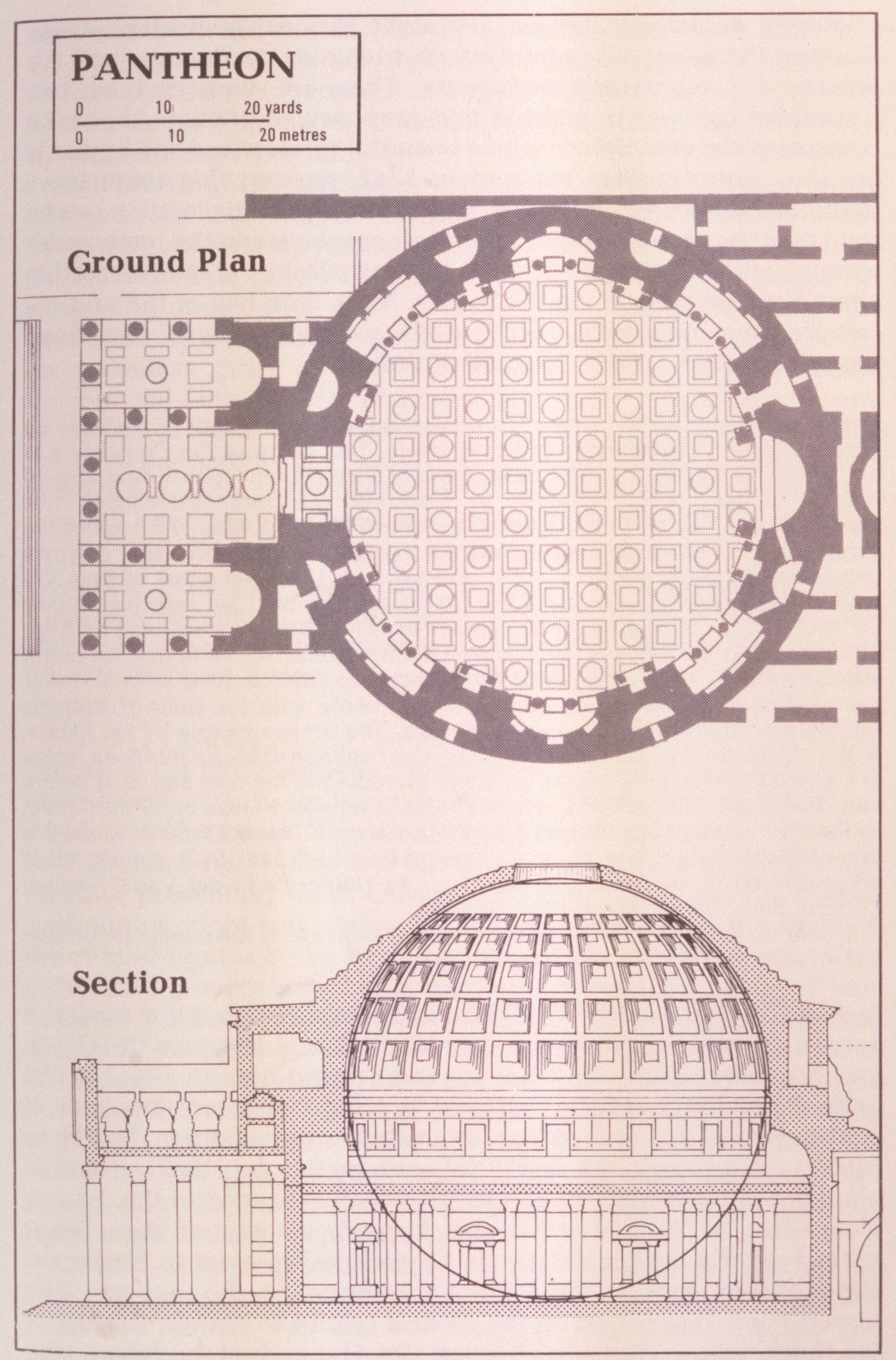

It was in Hadrian’s time, too, that the Pantheon (the ‘Temple of All the Gods’), received its definite form, with its striking circular ground-plan and circular section.

(You will not be surprised to learn that when the Pantheon was adopted as a Christian church, dedicated to the Virgin, it was called ‘Round St Mary’s’, Santa Maria Rotonda.)

The upper photograph shows part of the column of Marcus Aurelius (dating from the end of the second century AD), with its astonishing twenty-one spirals in a continuous frieze of relief sculptures representing a single, imaginary triumphal procession. (The spirals are always clearly indicated in fifteenth-century representations.)

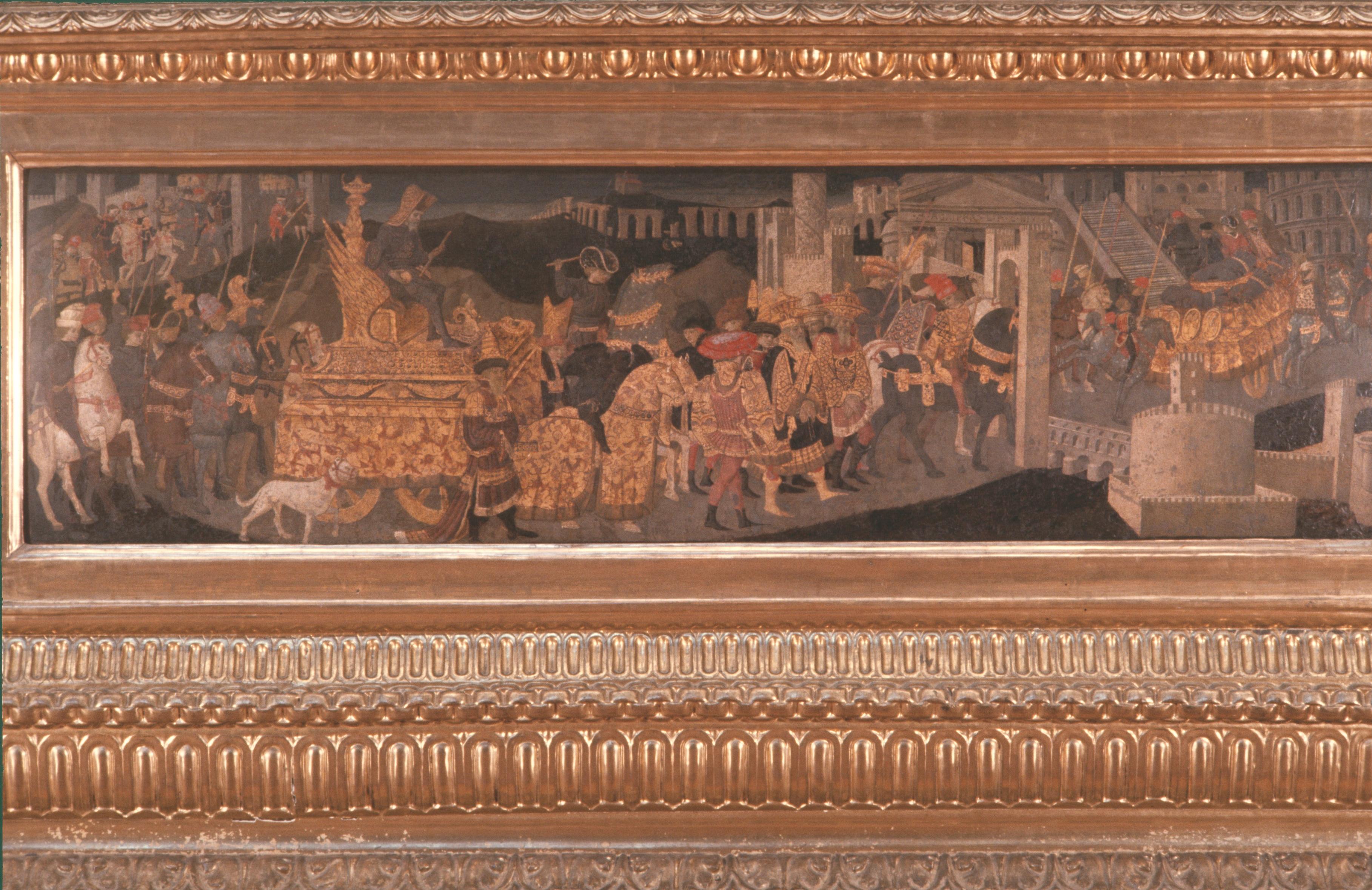

The most charming confirmation that these were indeed the ancient buildings that captured the essence of ‘the glory that was Rome’ for travellers in the middle of the fifteenth century is to be found in this panel from the Fitzwilliam Museum, which is now displayed in a modern imitation of a chest or cassone.

Its chief interest for us lies in the right half of the painting, which you can see reasonably clearly in the detail.

The triumphal procession of Scipio is approaching Rome from the north.

It makes its way past the aqueduct in the campagna and enters the city through a gate in the Aurelian wall, leaving Castel Sant’Angelo on the right bank of the Tiber.

It continues past the spiralling reliefs on the column of Marcus Aurelius and past the Pantheon (labelled Santa Maria Rotonda) to the foot the Capitol (note the flight of steps up to Ara Coeli).

The architectural capriccio is completed by the Colosseum (labelled Coliseo) on the extreme right.

Meglio di così si muore!

We must not forget, however, that most of the travellers who entered the city from the north were Christian pilgrims (known from their destination as ‘romei’ or ‘Romeos’). They came every year in a steady stream to visit the countless sacred shrines with their precious relics of martyrs and other saints; and they came in their tens of thousands each Jubilee Year to ensure full remission of their sins by visiting the Seven Basilicas of Rome.

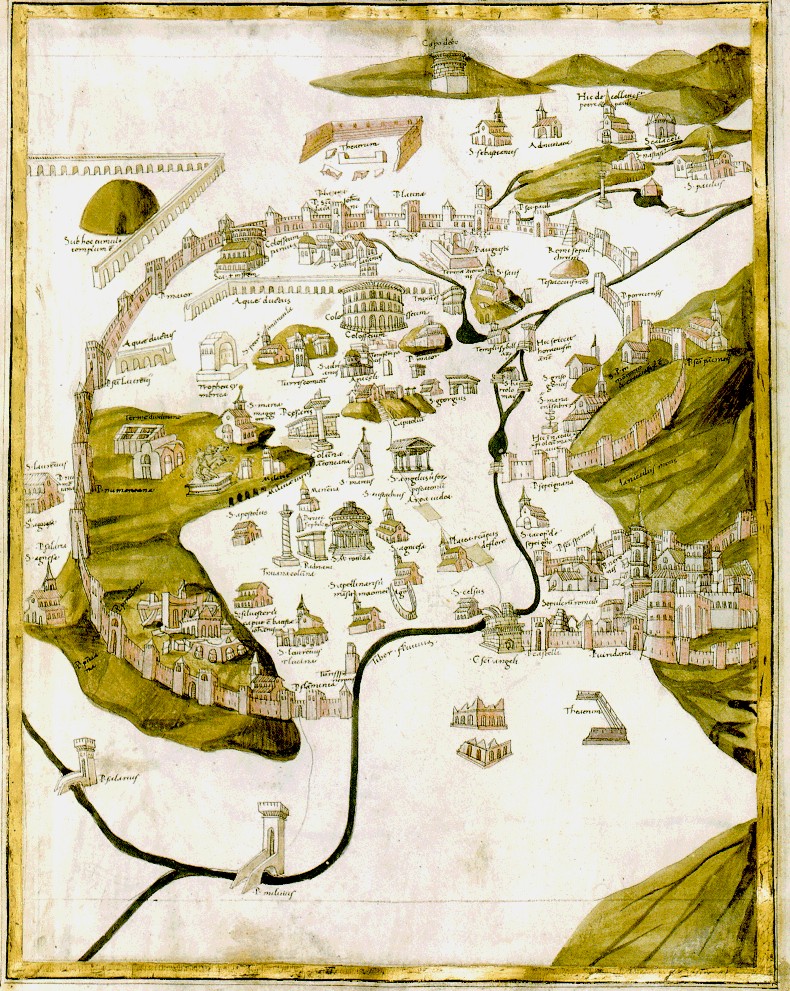

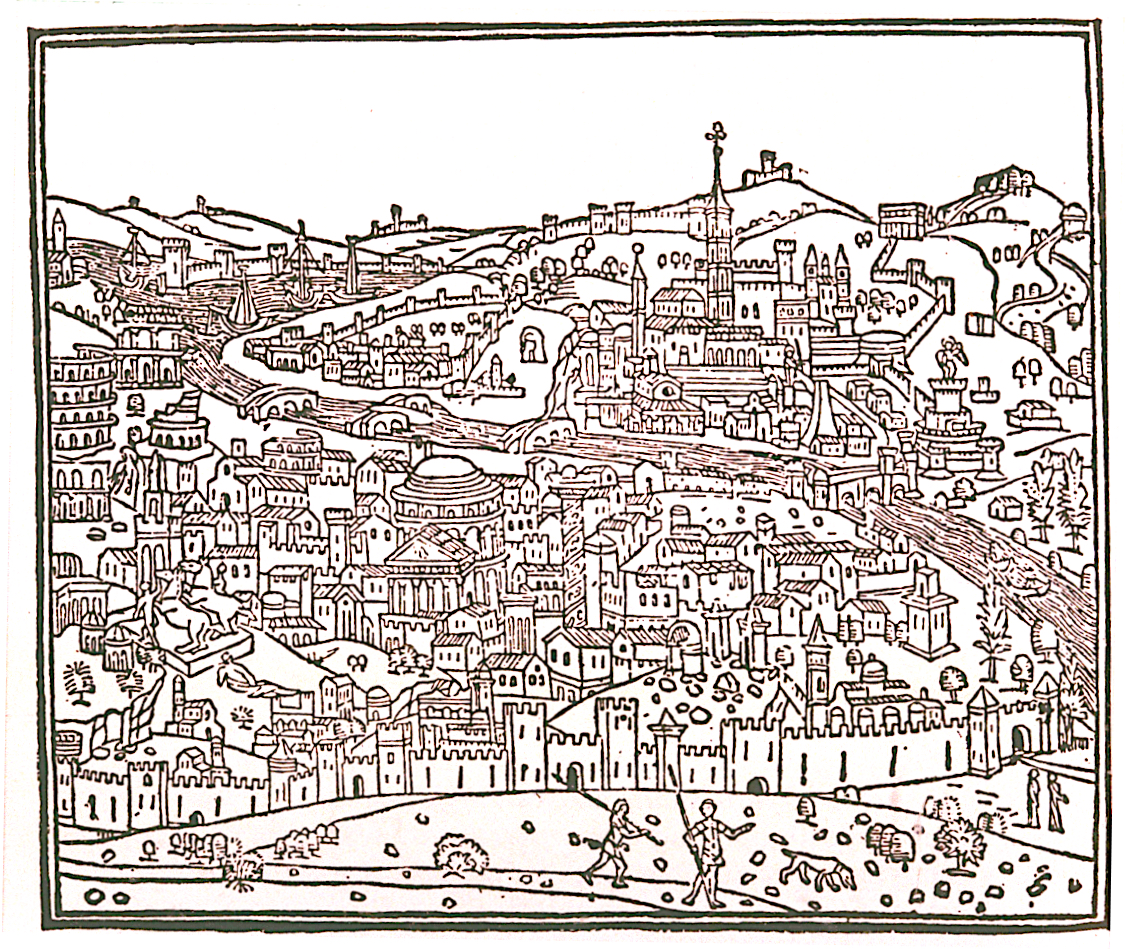

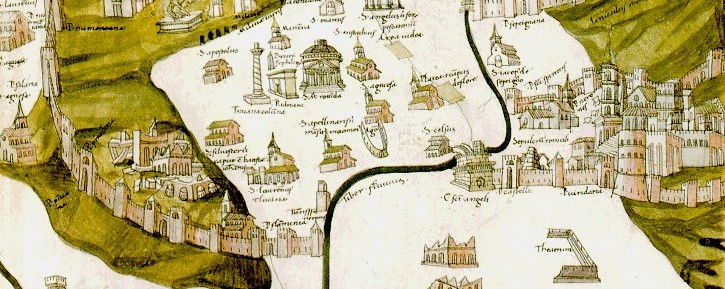

This very beautiful, and more specifically Christian, plan of the city dates from 1469.

South is at the top of the map again, so that St Peter’s and Castel Sant’Angelo are again placed across the river on the right of the plan.

The Colosseum and Santa Maria Rotonda are easy to locate.

The Tiber and the curve of the Aurelian walls are shown with remarkable clarity.

All the Basilicas had precious relics, but by far the most important of the seven was the one that the emperor Constantine had caused to be built over the tomb of Simon Peter, the ‘first’ of the apostles. This was, quite literally, the church which Christ said he would ‘build’ on the ‘rock’ (petra) that was ‘Peter’.

It was the tomb of St Peter, under the crossing, which had made Rome second in point of holiness only to Jerusalem.

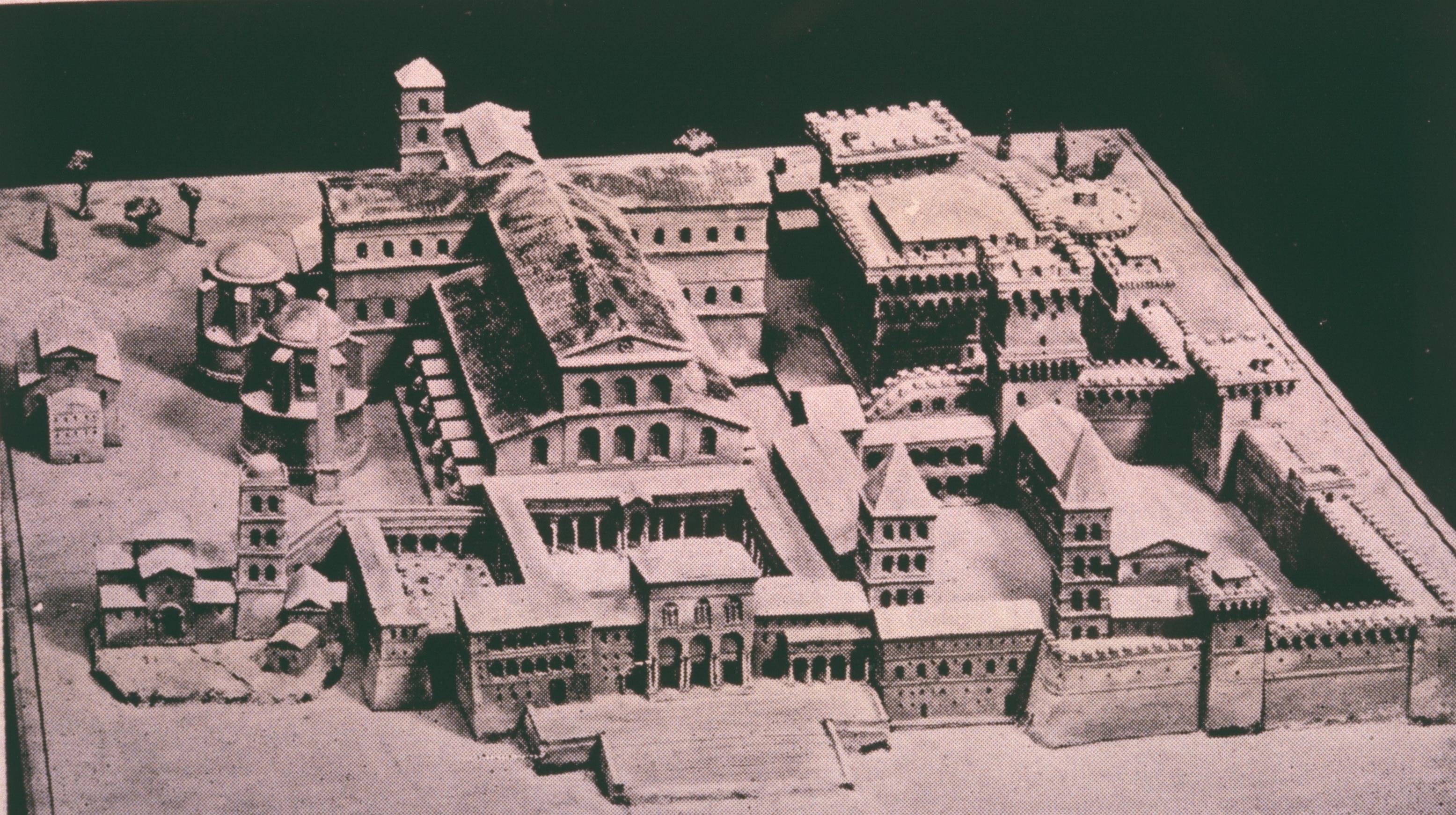

The black-and-white photograph of a model shows Old St Peter’s as it was in the period that concerns us—the last years of the fifteenth century and the first three decades of the sixteenth. You can see the building which was reconstructed as the Sistine Chapel in the group to the right of the basilica.

We shall come back to old St Peter’s and the Vatican Palace later on, but we must now leave the physical and mythical context of ancient Rome and of early Christian Rome, in order to glance at the history of the papacy in the hundred and fifty years before Pope Sixtus was elected in 1471.

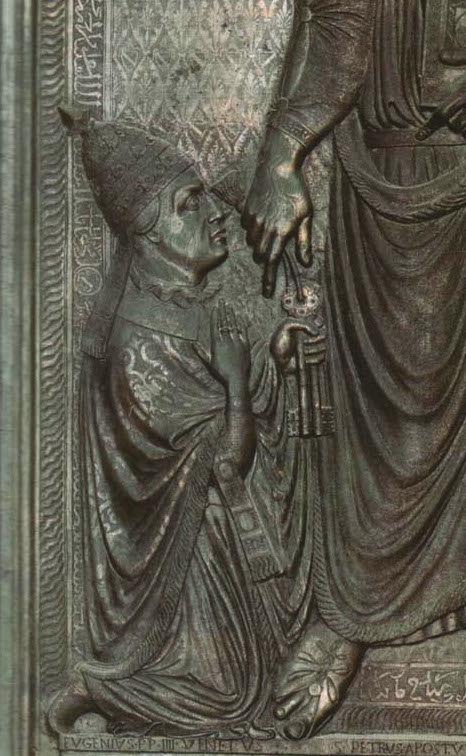

In the year 1300, pope Boniface VIII inaugurated the first Jubilee Year. (This is the event commemorated in a faded fresco in St John Lateran).

And if you were to read his famous Papal bull of 1302, Unam sanctam ecclesiam, you would be left with the impression that the papacy had never been so strong, or so intransigent in its claim to universal, political authority.

Similarly, if you were to read Monarchia, Dante’s political treatise, and the open letters he wrote to the newly elected Holy Roman Emperor, Henry VII, only ten years later, you would think that the empire, too, was still a European force.

But Henry’s expedition to assert his authority in Italy ended in military defeat and death in 1313.

(The surviving statues of his elaborate funerary monument are in Pisa.)

And the popes had already transferred their administration to Avignon in 1300, largely because they could not guarantee their personal safety, or that of their officials, in the turbulent commune of Rome.

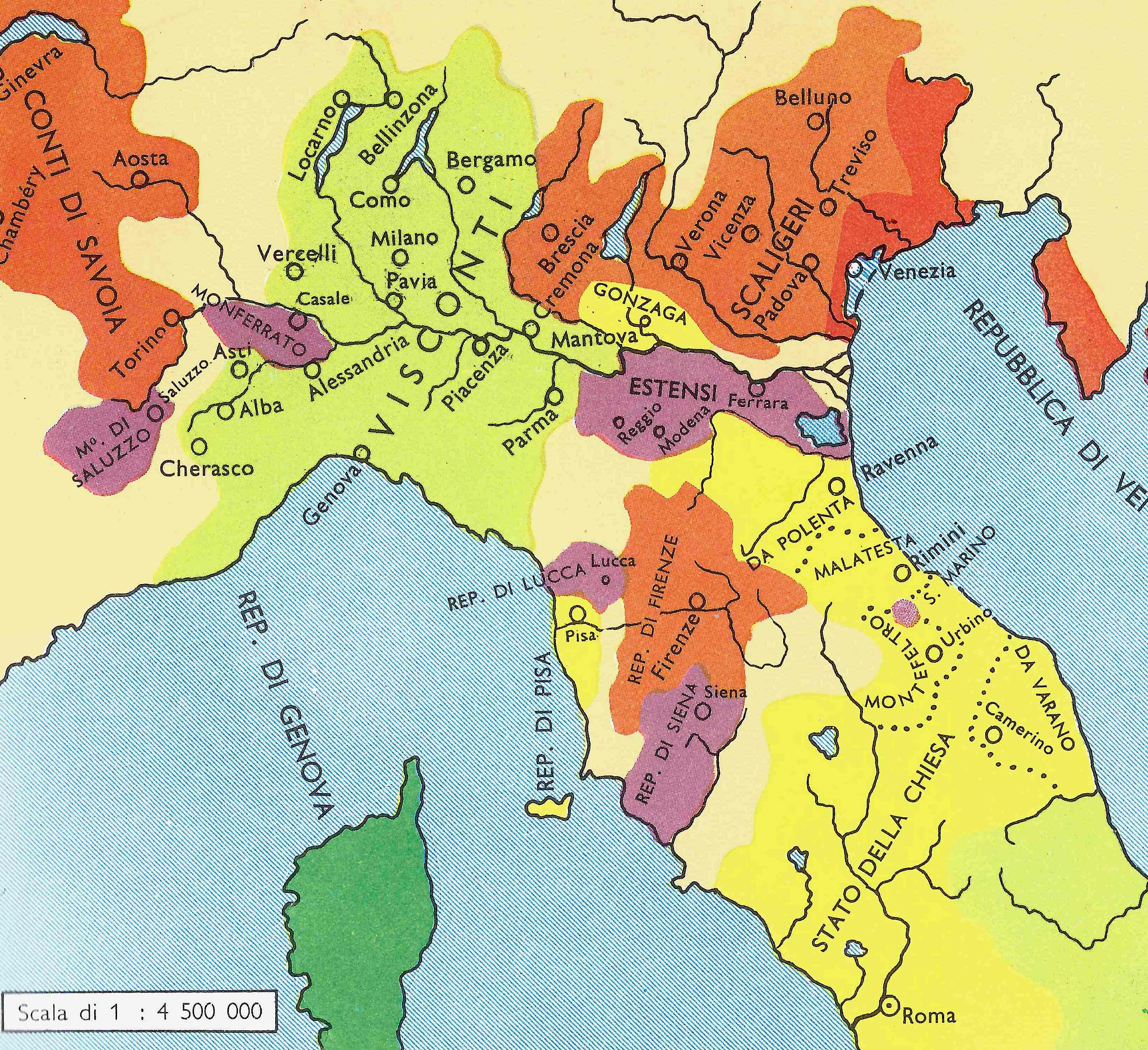

In theory, the pope was not only head of the universal church—with a large revenue deriving from the tithes of Europe—but also the temporal ruler or overlord of a huge area in central Italy, coloured yellow on this map.

In theory, too, the various ‘lords’, who ruled the states in the north of Italy, owed feudal allegiance to the Holy Roman Emperor.

In practice, neither pope nor emperor was in Italy—let alone in Rome—for more than a few weeks at any time between 1315 and 1365.

Many intellectuals, chief among them Petrarch, urged the popes to return to their rightful home—but when, in 1378, one of them, Gregory XI, was in Rome for long enough to die there, disaster ensued.

The cardinals, in conclave, elected an Italian, who took the name of Urban VI.

(The relief sculpture on his tomb proclaims that he derived his authority from St Peter).

But when the cardinals returned to Avignon, they declared that they had been acting under duress, and they elected another Frenchman as the true pope.

Each pope named his own college of cardinals who elected successors, with the result that for the next thirty years there were rival popes, one securely in Avignon, one precariously and intermittently at Rome, each with their European backers.

This came to seem an increasingly intolerable scandal, with the result that a number of cardinals from both sides called a General Council of the Church at Pisa in March 1409.

They elected a third pope, which was even more intolerable, such that another General Council was summoned in 1414 at Constance, just across the border from north-east Switzerland, this time with more political ‘clout’.

After nearly four years, the Council persuaded the Roman and Pisan popes to abdicate, and they elected a member of a Roman noble family, the Colonna, as Martin V, in November 1417.

Martin was a vigorous man and a local, with local influence.

He returned to Rome in 1420, and for the next eleven years he began the task of asserting the Pope’s political authority in the city and the Papal States, and started on the long task of repair and rebuilding.

His successor, Eugenius IV, was not a local.

He was forced to call a third council at Basel, and to abandon Rome as his seat because of local unrest for the ten years between 1433 and 1443.

You can see from the Table that Nicholas is only four pontificates away from Sixtus, and that only sixteen years separate the death of the one from the election of the other.

I will not attempt to characterise the different personalities and political priorities of these four men, but—before we come on to Sixtus—something must be said about the challenges they all had to face.

| Table of fifteenth-century Councils of the Church and Popes | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

Pisa Constance Basel (Florence) |

1409 1414–18 1431 (1439) |

Martin V Eugenius IV Nicholas V Calixtus III Pius II Paul II Sixtus IV |

(Rome) (Venice) (Florence) (Aragon) (Siena) (Venice) (Liguria) |

1417–31 1431–47 1447–55 1455–58 1458–64 1464–71 1471–84 |

The first and most dramatic challenge was the rapid advance of a rival religion, Islam, which was being carried towards Eastern Europe by the Ottoman Turks.

It was this threat that had led the Byzantine Emperor, John Palaeologus VIII (here portrayed in a famous medal by Pisanello) to come to Italy with his leading churchmen to seek an accommodation with the West.

But he and his successor were to be no match for the Sultan, Mehmet II (here in a portrait by Gentile Bellini), who assumed power in 1451.

It was under his command that the Turks captured Constantinople in 1453, sending out refugees and shock waves across Europe.

We must remember, therefore, that mid-century popes had to devote a good deal of time, energy and finance in trying to organise new crusades to halt, or to drive back, the infidel.

To some extent, of course, the military threat of the Ottoman Empire tended to make Christians and Christian rulers close their ranks.

It strengthened the popes in their relationships with the rulers of northern Italy and northern Europe, where they were trying to reassert their political authority.

It helped them in their efforts to harness the pressures for reform within the Church (pressures that had begun with a demand for regular General Councils whose decisions would be binding on the pope, but later took the more extreme form of a repudiation of the Bishop of Rome, in a process that we know would lead to the creation of independent, national churches in the following century).

The popes, however, were also feudal overlords of vast areas in central Italy; and to some extent they found themselves on the same footing as the king of Naples, the dukes of Ferrara and Milan, and the leading citizens in the republics of Florence and Venice.

Like them, they entered into bewilderingly short-lived alliances against other rulers, hiring mercenary soldiers (no Italians did their own fighting), and wheeling and dealing for short term gains in a way that we now find almost incredible.

Lastly, the popes had to assume direct responsibility for the governance of the city of Rome itself, which you see here in a woodcut from the year 1490.

They had to repair the city defences against possible attacks by the Turks—or by armies hired by the rulers of other Italian states!

They had to enforce law and order in a notoriously anarchic community and to improve the flow of traffic in order to make better provision for the tens of thousands of pilgrims who would come to Rome in the Jubilee Years of 1450 and 1475.

Finally (and this is where our story really begins), they felt the need to restore the city to its ancient splendour, by rebuilding the monuments of Christian Rome—the Rome of the martyrs—and by building new palaces, public buildings and churches in a style that would recall the surviving monuments of Imperial Rome.

They wanted Rome to look like, and thereby to become, the ‘head of the world’—caput mundi—a city that would be worthy to be the ‘seat’ or ‘see’ of the pope and that would reinforce his claim to be the absolute head of the Christian community and the supreme arbiter of European politics.

The process of restoration and repair had begun with Pope Martin V, while the first coherent plans for new buildings were drawn up by Nicholas in the early 1450s.

Sustained progress, though, came only in the 1470s, during the pontificate of Sixtus IV; and this progress was very much the direct result of his activities as ‘pope and patron’.

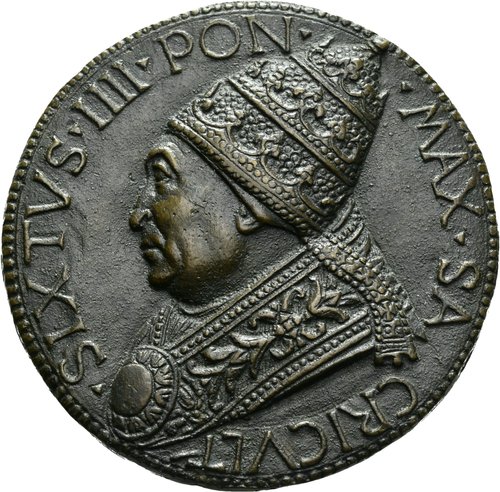

Sixtus is a splendid example of how it was still possible for a man of humble origins to rise to the highest position in the Church, thanks to intellectual vigour and administrative talent, and how it was then impossible for such a man to exercise authority without recourse to the style and methods—the Realpolitik—of the secular rulers of the day.

He was born in 1414 in Liguria, in north-west Italy, very close to the town of Savona, which he regarded as his birthplace.

He was christened Francis, and for most of his life called himself Francesco da Savona.

His family was of the very minor nobility and not in the least prosperous; and he owed his education to the generosity of a relative in Savona called Paolo Riario. He joined the order of his name saint—the Franciscans—and he went on to study philosophy and theology in the University of Padua in the north east, where he became a lecturer in logic and philosophy by the time he was thirty, in 1445.

He seems to have been a gifted teacher, but his greatest gifts were as an administrator, and by the age of fifty (in 1464), he had risen to be Minister General of the whole Franciscan order.

Success in this role brought him a cardinal’s biretta just three years after that (in 1467), and a palace in Rome, where he began to show signs of political realism by obtaining benefices that would secure his financial base.

His reputation as theologian, administrator and man of personal integrity allowed him to emerge as pope in the conclave of just eighteen cardinals who met in 1471.

He assumed the name of Sixtus, in honour of an early pope who had been martyred in Rome, and immediately surrounded himself with officials from his native Liguria.

Sixtus also appointed members of his own family as cardinals—the two most prominent being Pietro Riario, who became the archetype of the Renaissance cardinal as conceived by Hollywood, and Giuliano della Rovere, whom you see below towering over his seated uncle, in a detail from a famous fresco which we will look at later.

Pietro died only four years later, having squandered huge sums of money.

Giuliano survived to become a pope in his turn, taking the name of Julius.

(He was the man who would persuade Michelangelo to paint the vault of his uncle’s Chapel—but this is to run ahead of ourselves…)

Our next task is to take note of some of the main events in Sixtus’s reign, and to see how he faced up to the challenges of the papacy.

He took his duties very seriously as a crusader and leader of Christendom against the Turk, making a substantial contribution to a joint fleet which harried the coast of Asia Minor and captured the port of Smyrna in 1473.

The medal, which you see again here, was struck in 1481 to commemorate papal success in driving the Turks from the toehold they had gained in Italy when they captured Otranto in 1480.

The lower image (strongly characterised, showing him bareheaded and older) is not a medal but a silver coin, of the kind known as a ‘testoon’ or ‘testone’, because it bears the head or ‘testa’ of a ruler.

It is significant, because Sixtus was apparently the first pope (and indeed one of the first Italians) to issue currency with his head shown in profile, in imitation of the classical Roman emperors.

Hence this is an image of the pope as imperator, or Caesar.

Sixtus was no less assertive in his role as overlord of the papal states, and in so doing he came very close to destroying the relatively stable balance of power established by the treaties of Cremona and Lodi in 1454, which had left northern Italy dominated by Milan, Venice, and Florence under the Medici.

He appointed another favourite nephew, Girolamo Riario, to be captain-general of the papal forces; and, in particular, he wanted to make Girolamo the direct ruler of the little city of Imola, near Bologna, at the foot of a crucial trade route across the Apennines, linking Florence with the Adriatic ports.

He tried to borrow money from his bankers to purchase the lordship of Imola from the duke of Milan. But Sixtus banked with the Medici family, who were then headed by the twenty-five year old Lorenzo.

Lorenzo refused to advance the money, doing his best, indeed, to frustrate the scheme.

Sixtus switched his bank account to another Florentine bank, run by the Pazzi family, who did put up the money in 1473.

Relations between Rome and Florence got worse and worse. Girolamo married a daughter of the duke of Milan in 1477; and in April 1478, he and his uncle were parties to a plot, involving the Pazzi family, to murder Lorenzo and his younger brother, Giuliano, during a High Mass in the cathedral of Florence.

Giuliano was in fact killed, and the reverse of this medal expresses the ‘public grief’ or luctus publicus. Lorenzo, on the other hand, was only wounded; and he survived to rally support and to hang several of the conspirators, including the archbishop of Pisa.

This led to a full scale war between Lorenzo and the pope, who found an ally in the King of Naples, Ferrante, a rather tough pragmatist, as you can infer from the portrait bust.

Things went badly for Florence, until in December 1479, Lorenzo went personally to Naples to negotiate with King Ferrante, and persuade him to abandon the pope.

It was at this juncture, early in 1480, that the Turks landed at Otranto and slaughtered the inhabitants—something which also helped to cool everybody’s heads and led to an end of the internal war. This war was followed almost immediately by yet another one—enough has been said to suggest the flavour of Sixtus’s activity as a politician.

Of course, Sixtus himself did not sail with his galleys against the Turks, nor lead his mercenaries into the field against the Italians—he would have spent many hours a day on his duties as head of the Church.

(He was also a scholar and a theologian, whom Raphael would later portray in the company of Dante, as you can see in the detail.)

He had to stand firm against the Conciliarists, and against some very pressing demands that he should summon another General Council of the Church.

He canonised his fellow Franciscan, the thirteenth-century theologian and minister-general Bonaventura and declared himself in favour of the doctrine of the Bodily Assumption of the Virgin Mary.

He was also a noted patron of music, and of literature, painting, and building.

This famous fresco (of which we saw a detail earlier on) shows him in the Library of the Vatican, on the day when he entrusted the collection of books to the humanist, Plátina, who wrote a history of all the popes, including Sixtus, down to the year 1474.

What concerns us most of all, however, was the activity commemorated in this medal, where he has once again taken off the papal tiara, in order to look more like an emperor.

The reverse of the medal is inscribed with the words cura rerum publicarum and commemorates his activity in promoting building works.

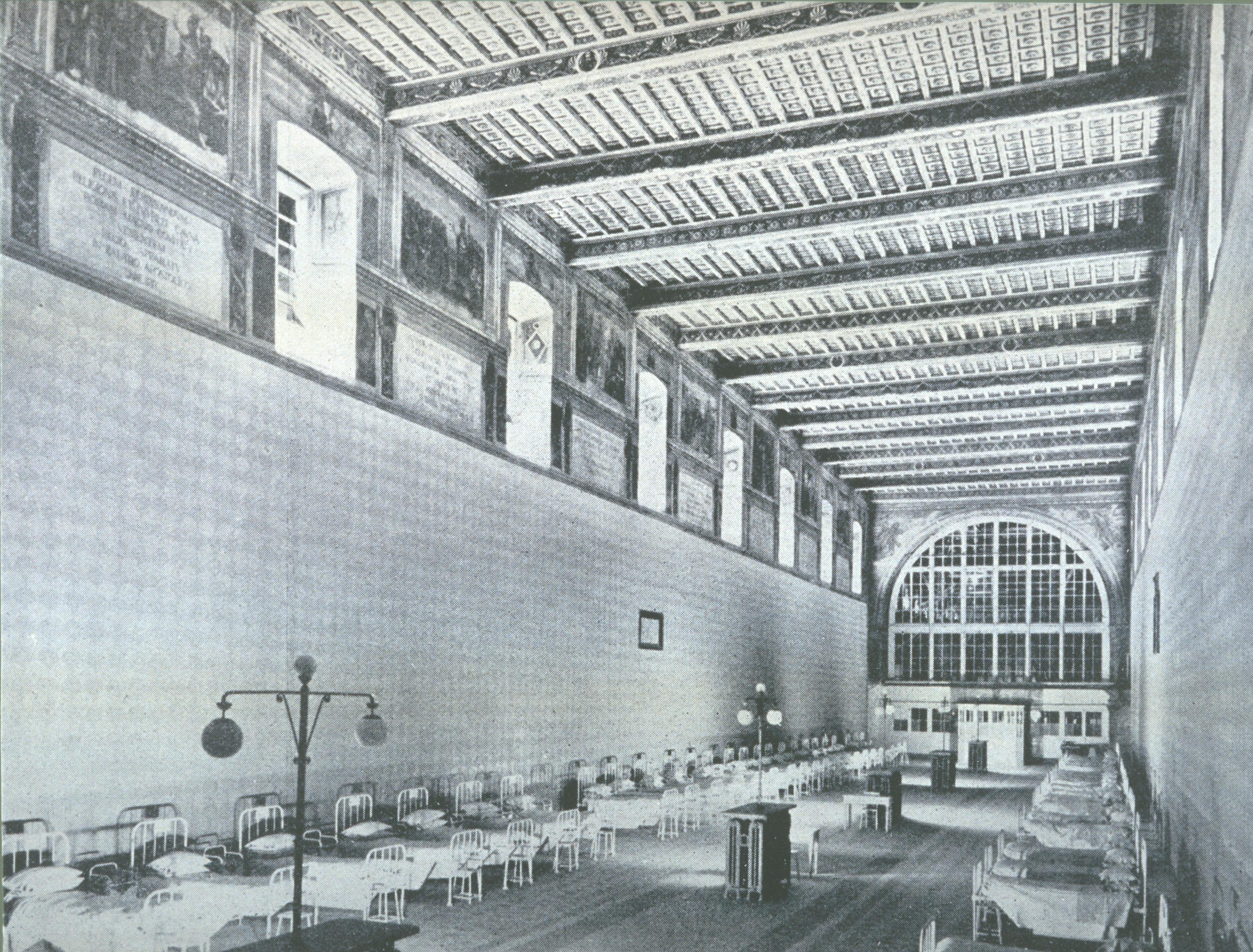

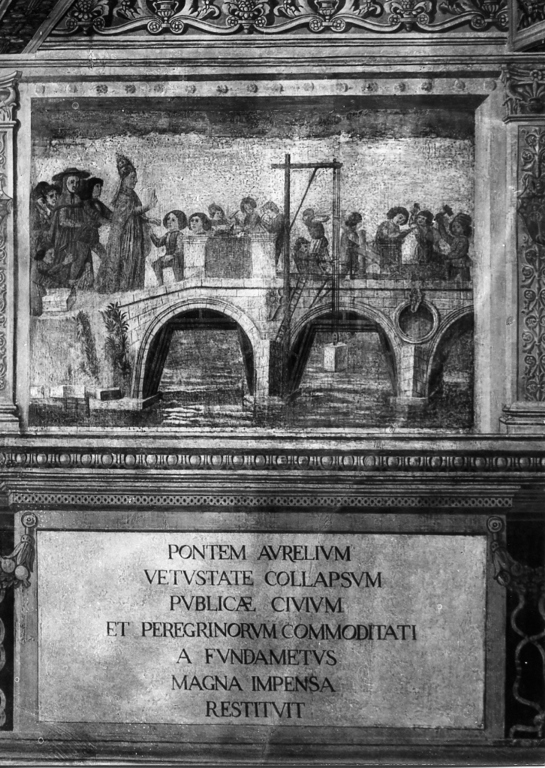

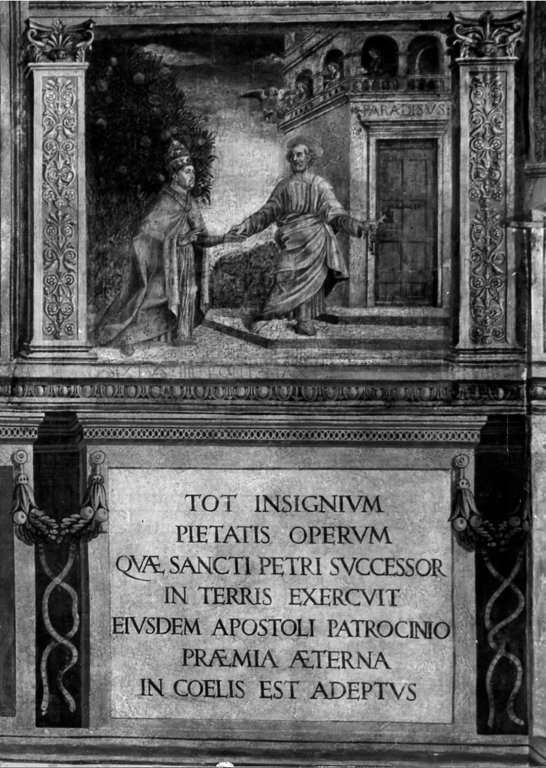

Soon after Sixtus’s death, the walls of the ward were decorated with frescos which depict the events of his life and of his pontificate.

(Their artistic quality is as low as the quality of the photograph, but they too have an important story to tell which could not be told more effectively.)

One of his major public works was the repair, ‘for the convenience of both citizens and pilgrims’, of the ‘Aurelian bridge, which had collapsed through old age’.

Quite rightly, the bridge still bears his own name—the ‘ponte Sisto’.

He cared very deeply for his building programme, as we can infer from the penultimate scene in the fresco-cycle on the walls of the main ward in the Ospedale di Santo Spirito.

You see him kneeling before God as his Judge, with the Virgin and St Francis to intercede on his behalf, justifying his earthly existence by pointing to the bridge, the two churches, and the hospital itself.

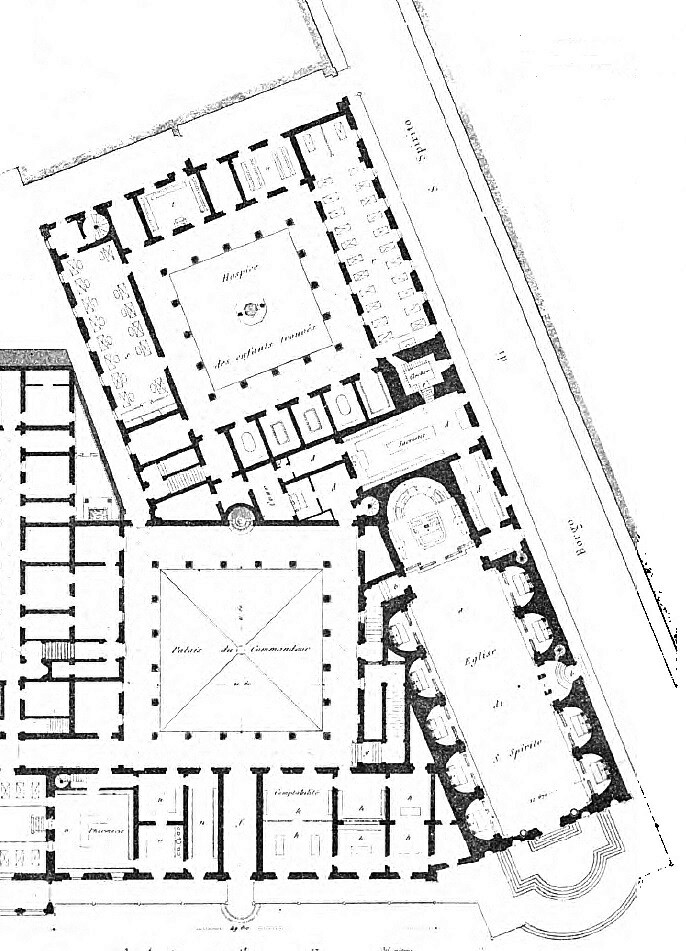

Posterity has decided that Sixtus’s most important project was the rebuilding of what was then called the ‘Great Chapel’, Cappella Magna, immediately alongside the Basilica of St Peter’s.

You can just make it out in the detail from the map made in the year 1469, where St Peter’s has a tower and blue-ish roof, while the ‘old chapel’ is the barn with buttresses alongside.

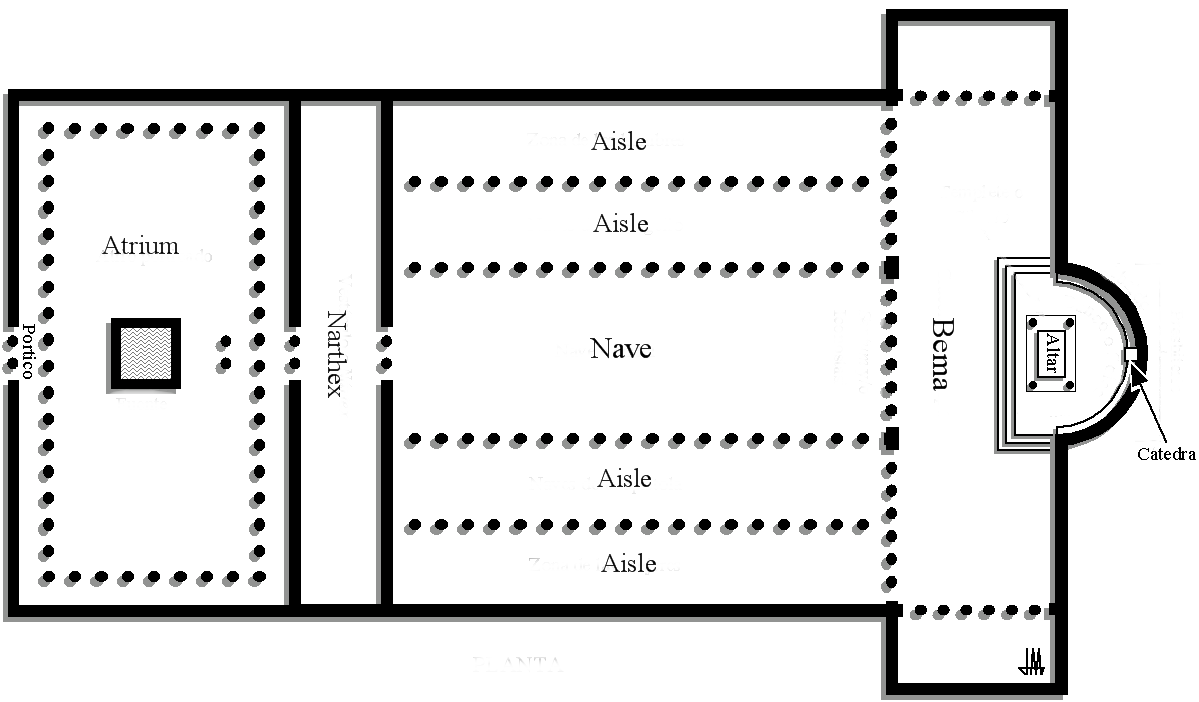

The ground plan of the old basilica has been reconstructed in this diagram, which shows that it had four aisles in all, two on either side of the nave.

The point to remember, however, is that the High Altar, placed in the crossing, was built over the tomb of St Peter, who, according to tradition, had been crucified head down in Rome, at a point less than a mile away.

The Basilica of St Peter’s, then, was a shrine; and the vast building was designed to accommodate huge numbers of worshippers and pilgrims.

The pope would have celebrated his personal daily devotions in his own intimate private chapel; but there was also need for a chapel of medium size, to be used on special days (of which there were 42 in the liturgical year).

On these days, all the two hundred members of the so called ‘Papal Chapel’, ranging from fifteen-or-so cardinals down to chamberlains and secretaries, as well as all the visiting envoys and grandees in Rome, totalling another two hundred people or thereabouts, would come together coram papa (in the presence of the pope) in one grand building for ceremonies of peculiar splendour and solemnity.

This was when the pope was seen as pope, surrounded by his ‘court’; and, as you will have deduced, the building in question was the so-called ‘Great Chapel’, which lay close to, and parallel with, the nave of the basilica.

This building had become ruinous for the same reasons as old St Peter’s—that is, because it was built not ‘on rock’, super petram, but on sand.

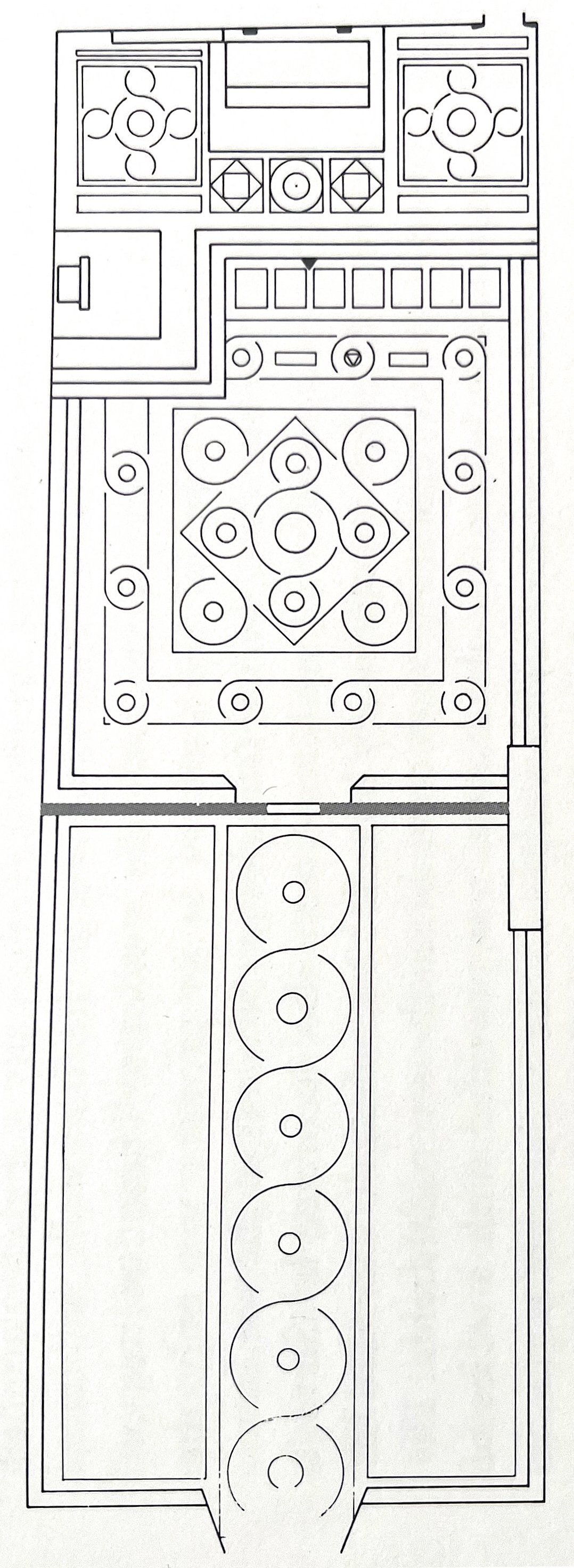

Sixtus had the chapel demolished in 1477, replacing it—in the astonishingly short space of three years—with an enormous brick structure built on the same, slightly irregular site.

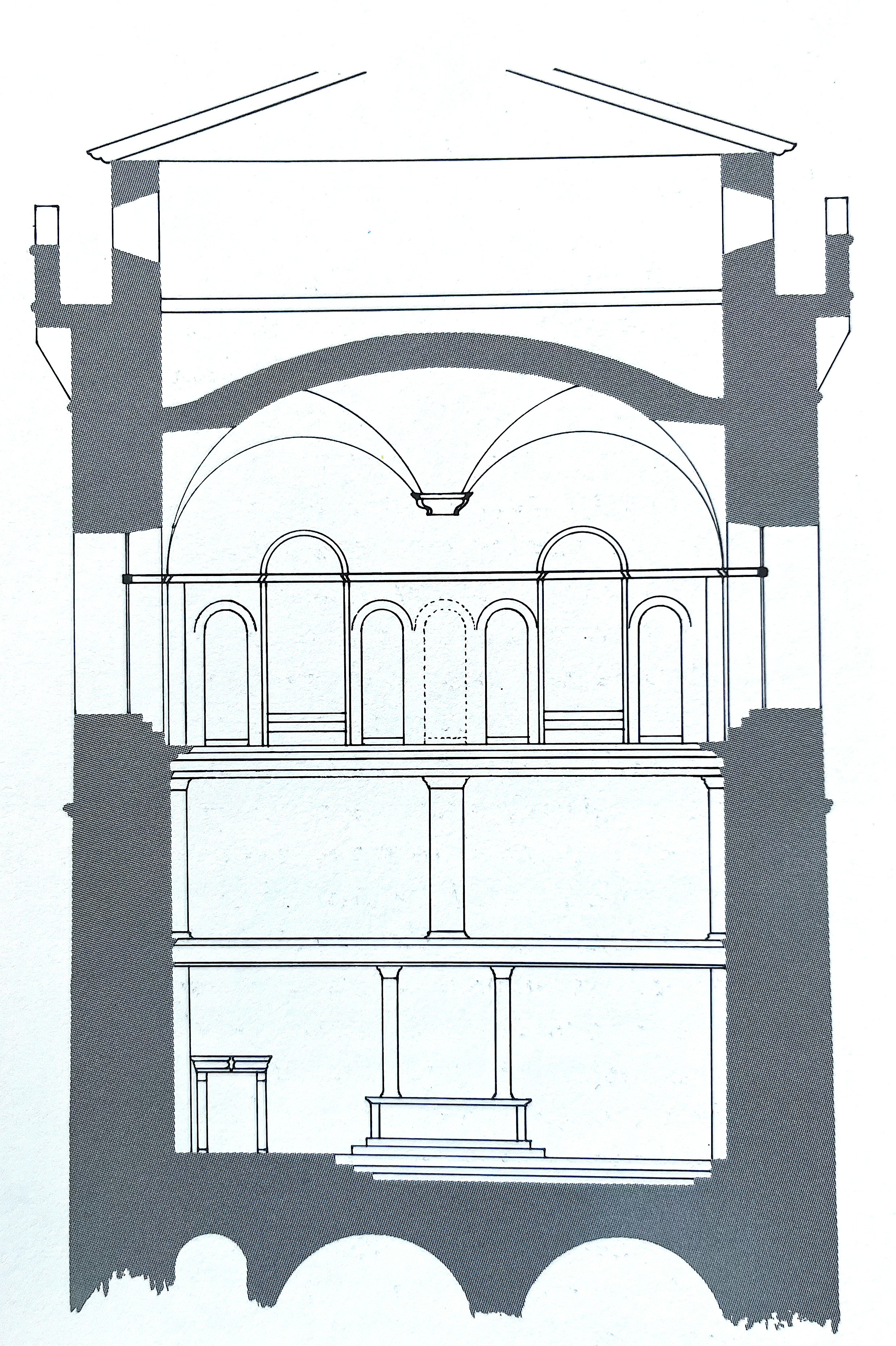

Your first impression is entirely correct. It is very tall.

And you must remember that the interior (which you see here in section) rises above some very substantial vaults, and is topped by a further vast space in the roof.

It has the dimensions of a fortress; and it was indeed fortified with battlements (as you can see in this reconstruction of its original appearance). Soldiers could be stationed behind the parapets to repel attackers.

In other words, the new chapel shared the functions of the ‘keep’ in a medieval castle.

It offered an inner line of defence; and was designed to protect the pope from physical attack, whether from the Roman people and local aristocracy, from soldiers employed by a neighbouring state, from the French or Spaniards—or from marauding Turks, who might land at the port of Ostia, at the mouth of the Tiber, just 20 miles away.

As I said at the beginning, everything in this chapel is ‘bursting with information’, some of it being of a very practical kind.

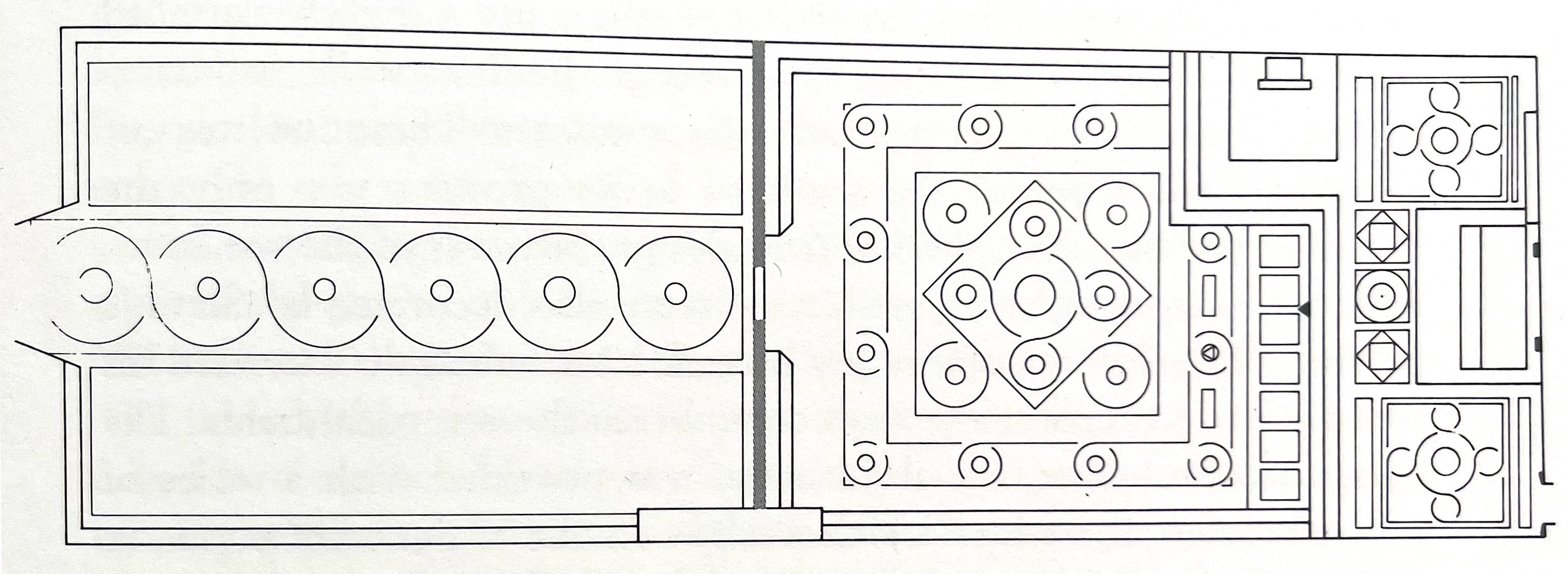

For instance, I can now explain that the marble screen in the chapel (shown by the heavy black line in the diagram) was originally placed in the centre, and separated the members of the ‘Papal Chapel’, or papal ‘establishment’, from non-members.

The altar is placed centrally, while the pope’s throne is positioned one step higher, to the left, as you can see in the late fifteenth-century miniature.

The square area inscribed with small circles defined the position of the special wooden seats for the cardinals, who sat on the three sides (as you see in the miniature).

The central corridor (vestibulum), meanwhile, was reserved for secretaries, who sat on the floor facing the pope.

The circles forming a continuous double spiral define the processional route, which had to be kept clear of visitors in order to allow the pope and his train to enter and leave, as they did twice in the course of each mass.

The circle nearest the entrance was distinguished in colour (being made of red porphyry, as it had been in very early Christian churches); and it was here that the pope—or any other visitor—would kneel upon entering the chapel.

Some of the other information encoded here, though, is more symbolic in character; and we may now use the same diagram as a ground-plan, revealing the main proportions of the chapel.

It has six window embrasures on each side, forming six equal bays; and it is these that constitute the ‘module’, or unit of measurement.

All the dimensions and proportions of the building are derived from the factors of six: three, two and one.

So, the length is six modules; the width is two modules; and the height is three modules; while the screen was originally placed to divide the chapel into three plus three.

Why this insistence on six and its factors? In part, it is because six is a so-called ‘perfect number’, meaning that it is the sum of its proper divisors: 1 + 2 + 3 = 6.

This, it was believed, was the reason why the Lord chose to create the Universe in six days.

There is also a probable allusion to the name chosen by Francesco da Savona when he became pope. Sixtus—like Septimus or Octavian—derives from the ordinal number, and it does indeed mean ‘sixth’.

However, there is another and more important symbolic reference encoded in these dimensions.

Each bay is about eight and a half yards wide, which corresponds to ten biblical cubits.

And if you turn to the Bible (I Kings 6:2), you will discover that ‘the house which King Solomon built to the Lord’ (i.e. the Temple in Jerusalem) ‘had sixty cubits in length, and twenty cubits in width, and thirty cubits in height’.

Thus, the dimensions of the new Great Chapel are those of Solomon’s Temple in Jerusalem. And no small part of Sixtus’ message is that he, as Pope, is both heir to the Sacred King, who caused the Temple to be built, and heir to the High Priest, who officiated in that building—all this, within the new Order, instituted by Jesus, in fulfilment and substitution of the Old.

But messages encoded in architectural dimensions and on tessellated floors are of necessity less complex and less immediately accessible than those which can be conveyed through well-chosen paintings of human protagonists.

Hence Sixtus had the chapel designed from the outset to include a continuous broad band, fourteen feet above the floor (visible to everyone even when the chapel was packed), wide enough to accommodate a series of huge narrative frescos which would assert his claims to supreme authority more powerfully in pictorial form.

These frescos, by a team of several artists working in the 1480s, form the subject of the second lecture.