Raphael: The Acts of the Apostles (Cartoons)

In this lecture, we come to the tapestries which were intended to be hung round the lower part of the Sistine Chapel on special Feast Days.

Since the tapestries only go round one half of the chapel, there will be ample time to pick up some of the themes of earlier lectures, to recall some crucial developments in the ten years between 1503 and 1513, and to look at the evolution of two earlier pictures by Raphael in order to become familiar with his style.

The most able of all Sixtus’s nephews, Giuliano della Rovere, was elected pope in 1503. (Raphael’s portrait of him was made in the last year of his life.)

He assumed the name of Julius II; and he was not unhappy to leave the impression that the first Julius was not so much a fourth-century saint as the man who ‘came, saw and conquered’

This first Julius had assumed the title of pontifex maximus, ‘supreme pontiff’; and, for his part, the second Julius saw himself as a general, and emperor or ‘Caesar’.

Even the beard you see in Raphael’s portrait is a homage. Caesar once let his beard grow, swearing not to shave until he had avenged a military defeat—and Julius has done the same.

Pope Julius made war throughout his ten year reign.

In 1506, he targeted cities within the papal states.

In 1508–9, he attacked the Republic of Venice, allying himself with the Spanish and the French, who by now controlled the South of Italy and the Duchy of Milan respectively.

Then, in 1511–12, he made war against the French, allying himself this time with the Venetians and the Spanish in a ‘Holy League’.

Even in this last campaign, he was personally in the field, in winter time, at the age of sixty-nine.

Julius showed the same mixture of determination and aggression in his resolve to continue the task, begun by his uncle, of rebuilding and improving the city of Rome.

Sixtus had been responsible for founding the Hospital of Santo Spirito (the large building in the foreground here), for rebuilding one of the bridges over the Tiber, and upgrading two churches dedicated to the Virgin. All these are shown in this charmingly naïve fresco, in which St Francis and Mary are pointing them out to God as they intercede on the pope’s behalf.

It had been almost impossible to get through the narrow medieval streets on the city side of the Tiber, between the bridge that his uncle had repaired and the bridge nearer St Peter’s—so Julius simply demolished buildings in a straight line, roughly parallel to the river, to create what is still called the ‘Via Giulia’.

Another striking piece of improvement took place in the years 1488–92, after Pope Innocent VIII had built a summer palace (with a view from its terrace, a ‘Belvedere’) well to the north of the main Vatican Palace. (You can make it out near the top of these photos).

In 1505, Julius hired the veteran Milanese architect, Bramante, to erect two gigantic wings to link the new building with the existing residence, forming the Cortile del Belvedere.

Bramante was by then in his sixties, and had been active in Rome for some time.

In 1502 he had been commissioned to build a small shrine in a tiny courtyard, very close to the church of St Peter in Montorio (about half a mile south of the Vatican), on the very spot where St Peter had been crucified.

His solution was the famous little temple, or ‘tempietto’, a miniature temple in the round, with a cupola and classical columns, which, despite its miniature scale, came to epitomise the style of the High or Roman Renaissance, as opposed to the Florentine or Early Renaissance (Christopher Wren is all there in potentia).

Not surprisingly, then, when Julius took the decision to demolish the basilica of Old St Peter’s, it was Bramante who was appointed as architect for the new church.

Bramante died in 1514, and his plan underwent many changes during the long period of construction to which this engraving bears witness (the drum of the Fabrica Nova is rising behind the nave and portico of Old St Peter’s). But the present cupola (completed to designs by Michelangelo) gives you a fair idea of his original intentions, or at least the spirit of them.

In the previous lecture, I explained how Julius summoned Michelangelo to Rome in 1506 to work on the abortive scheme for his tomb, and again in 1508, to fresco the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel.

In that same year 1508, he moved his personal apartments to a higher storey in the Vatican Palace and decided to have these rooms suitably decorated in fresco. Taking the advice of Bramante, he employed, and soon gave a free hand to, a young painter—just twenty five years old—called Raffaello Sanzio.

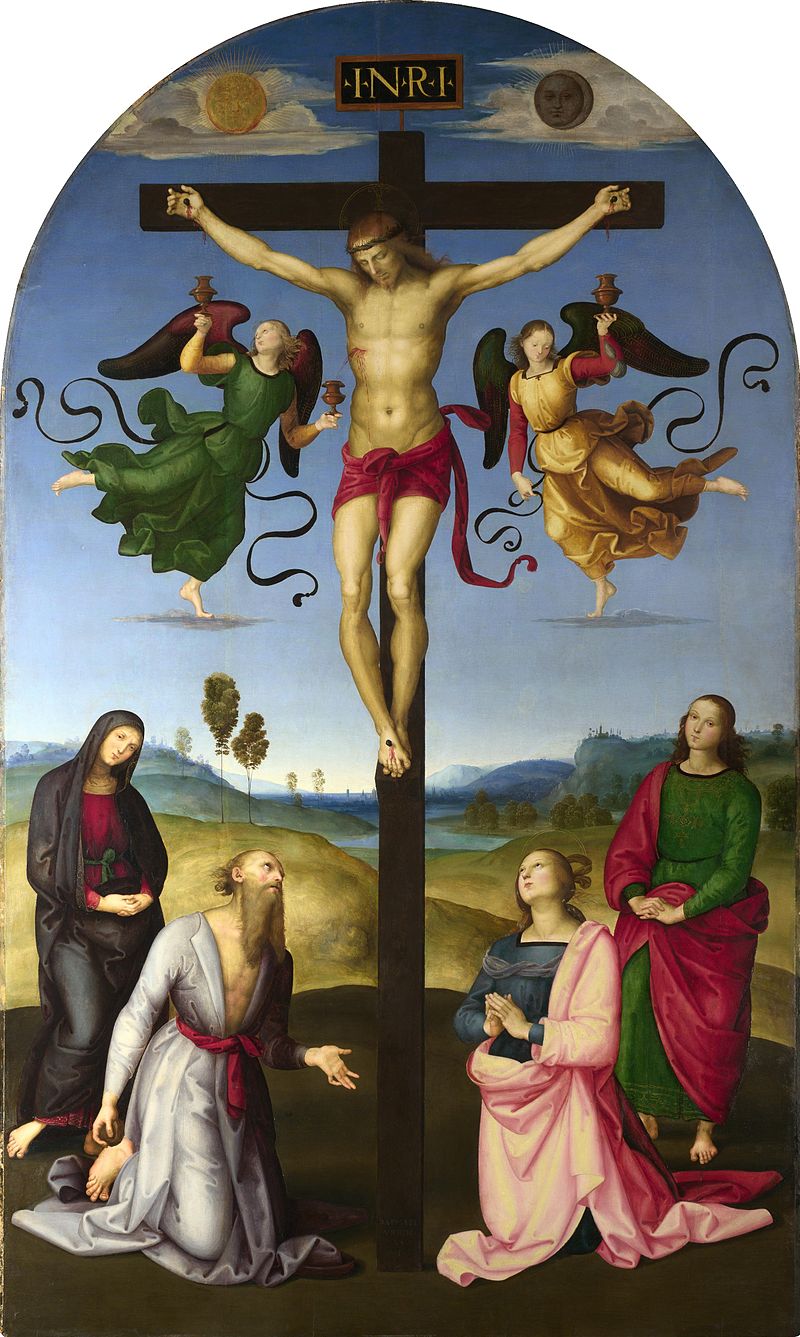

The son seems to have been apprenticed to Perugino (who had been the senior artist among the four teams who worked on the frescos for the walls of the Sistine Chapel).

By the age of seventeen or eighteen, he could paint this huge altarpiece, which is also in the National Gallery, in a brilliant and assured pastiche of Perugino’s style.

From the age of twenty to twenty five—that is, from 1504 to 1508—Raphael seems to have been mostly in Florence, painting busily and evolving rapidly under the joint stimulus of the fifty-year-old Leonardo and the thirty-year-old Michelangelo, trying to emulate both of them in their common endeavour, that is, in the greater complexity and difficulty of the poses of individual figures, and in the greater unity of their compositions.

The best way to feel ourselves back into his mind and approach in the period just before he came to Rome is to look at the evolution of a single altarpiece, which is signed and dated 1507.

It is roughly six feet square and represents the ‘Bearing of the Body of Christ’, but is usually known as ‘The Entombment’.

The square format was determined by the original location, and the subject was no doubt dictated by the patron—a grieving mother from the ruling house in Perugia, who wanted to commemorate her son, who had been murdered in the year 1500.

In its final form you see a landscape in the style of Perugino (with three diminutive crosses on the skyline), and two highly un-Perugino-like groups of figures in the foreground.

To the left and in the centre, a bearded man and a very striking, beardless youth, are carrying the body of Christ, helped (or hindered) by St John, Joseph of Arimathea, and Mary Magdalene (all discretely haloed). To the right (as is not untypical in a Crucifixion), the Virgin has fainted, supported by the Holy Women.

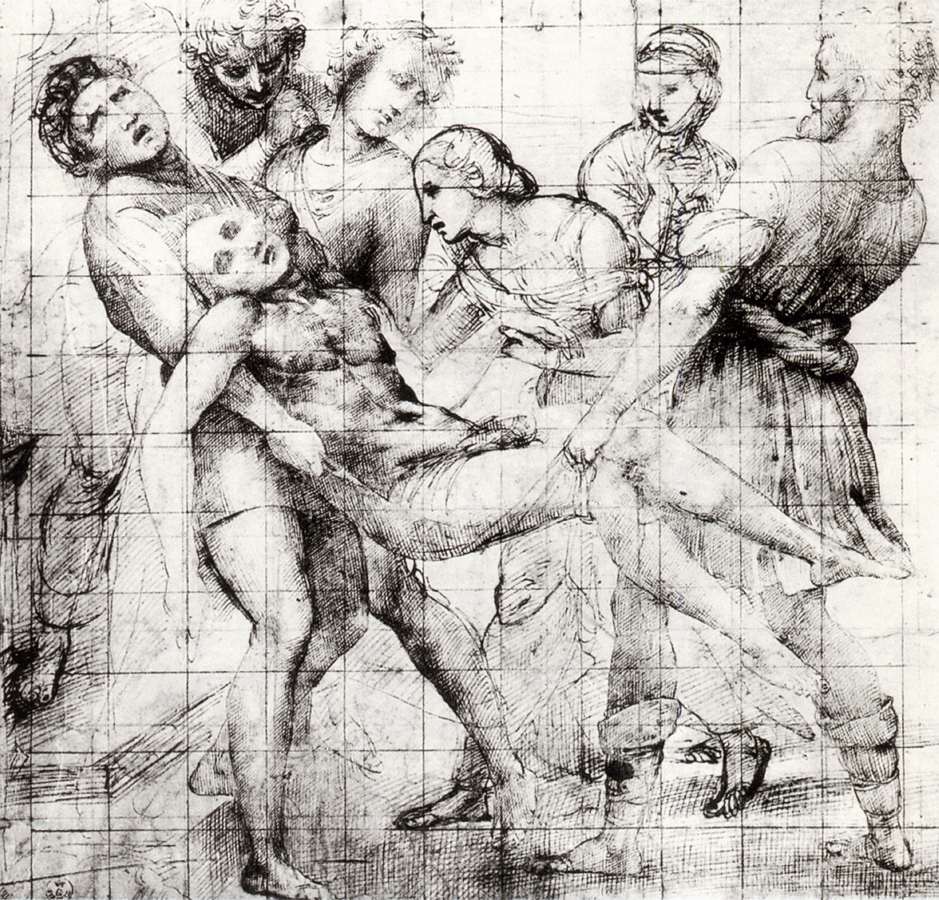

However, we know from a long series of sketches that this composition was far removed from his first thoughts, so let us take a look at four of the surviving drawings.

The earliest, now in the Ashmolean Museum at Oxford, shows that he began by combining a Pietà (Mary’s lament over the body of Jesus) with the motif of the swooning mother, to form a satisfying V. The women are to the left and the men to the right; the landscape is already hinted at, and the square format already given.

Then Raphael saw and drew a classical relief-sculpture (perhaps the very one illustrated here), representing the carrying of the body of Meleager.

The panel had been singled out for special comment in Leo Battista Alberti’s Della pittura (1436) for the way in which the artist had represented the lifeless body as being ‘dead down to its very fingernails’.

The composition must have seemed too stiff and horizontal, so he went back to his original V motif, making the bearers take all the weight. (One now comes forward, and the other begins to lean away.) The men are now to the left, Mary Magdalene is the woman in the centre, stooping to kiss Jesus’ hand, and the Virgin is shown still approaching from the right.

In a very late version—we know it is late because it is already ‘squared’ for enlarging onto a cartoon—Raphael is feeling for the masses and volumes of his figures.

The left-hand bearer has got further underneath the body; the right-hand one, even more burly and Michelangelesque in physique, leans further back; the heads of John and Joseph of Arimathea have come closer together; and now it is Mary Magdalene who has clearly just rushed up to the side of the body, as in the final painting.

Even from this version, there was still a long way to go to the final painting. (Joseph and John will be reversed, as too will the ages of the bearers, since the one on the left gains a beard while the one on the right becomes a young Greek god. The living heads become more intensely emotional; the dead head, much ‘deader’; and the V will return, heightened by the landscape.)

There is a lot more one could say about the influence of Leonardo and Michelangelo in the group of women, but by now you have seen enough to ‘pick up Raphael’s line of flight’, so to speak, and to have gained some insight into the working methods of a perfectionist.

He will always seek inspiration in classical sculpture and in the paintings of his great contemporaries; he will always compose the figures ‘polyphonically’, so that every adjustment to one figure entails adjustments to another.

Faces and gestures must convey emotion, and the whole effect is not just theatrical, or operatic, or melodramatic, but like a still from a ballet—or perhaps like the moment in the game of ‘Statues’ when the music suddenly stops and everyone in the room has to freeze.

At this point we must move on to the papal apartments in the year 1508, and, in particular, to the cross-vaulted room, about twelve paces by ten, which has come to be called the ‘Stanza della Segnatura’, where Raphael was working in exactly the same period as Michelangelo was frescoing the ceiling of the chapel about one hundred yards away.

There are four main frescos—one on each of the roughly semicircular walls—and their message is hardly less complex or universal than that of the Sistine Chapel. They offer a celebration of poetry, law, philosophy and theology, through the portrayal of their most illustrious representatives. The whole room asserts three things: that mankind needs legislators and poets, theologians and philosophers; that the revealed truths of Christianity are compatible with the discoveries of human reason; and that the highest values of ancient Rome are flourishing again in the Christian Rome of 1500.

There is no time to discuss in detail Raphael’s art in more than one of the frescos, so let us simply ignore the vaulting and the two smaller walls (representing Law and Poetry).

We may also take the representation of Theology more or less for granted—we are, after all, in the apartments of a pope.

It is relevant, however, to note the prominence of Pope Sixtus IV in his gorgeous robes among the theologians in the foreground, and the conspicuous placing, on the flanks of the saints in heaven, of Saints Peter and Paul.

All these figures (‘on earth, as it is in Heaven’) are united in their contemplation of the Eucharist, and presumably all united in their affirmation (which the Protestant churches would soon deny) that the consecrated wafer on the altar—the centre of the whole composition and of the perspective system—is not just a symbol of the body of Christ, but is miraculously transubstantiated into that body.

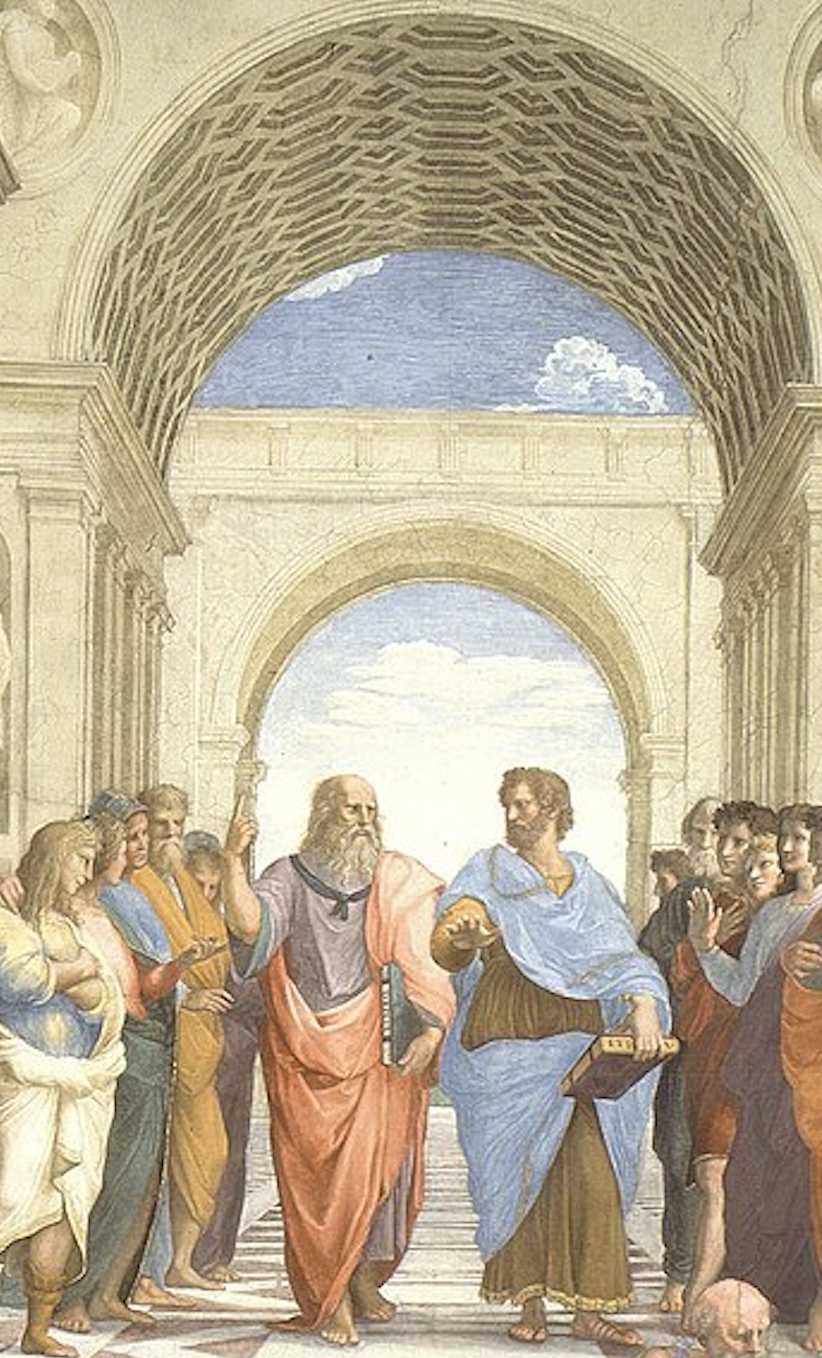

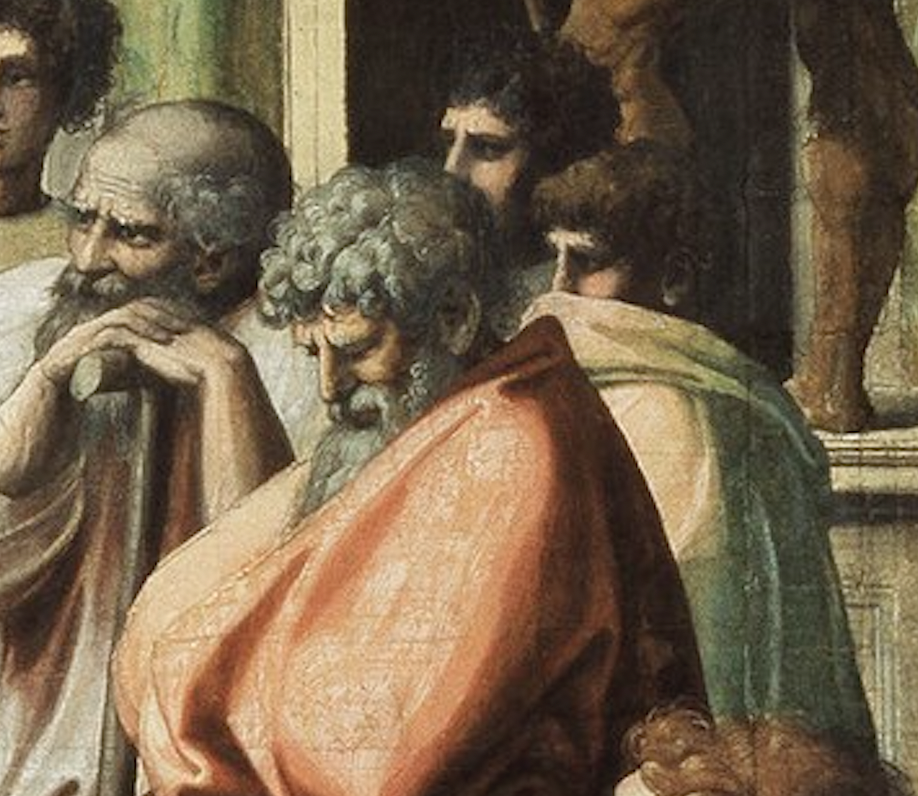

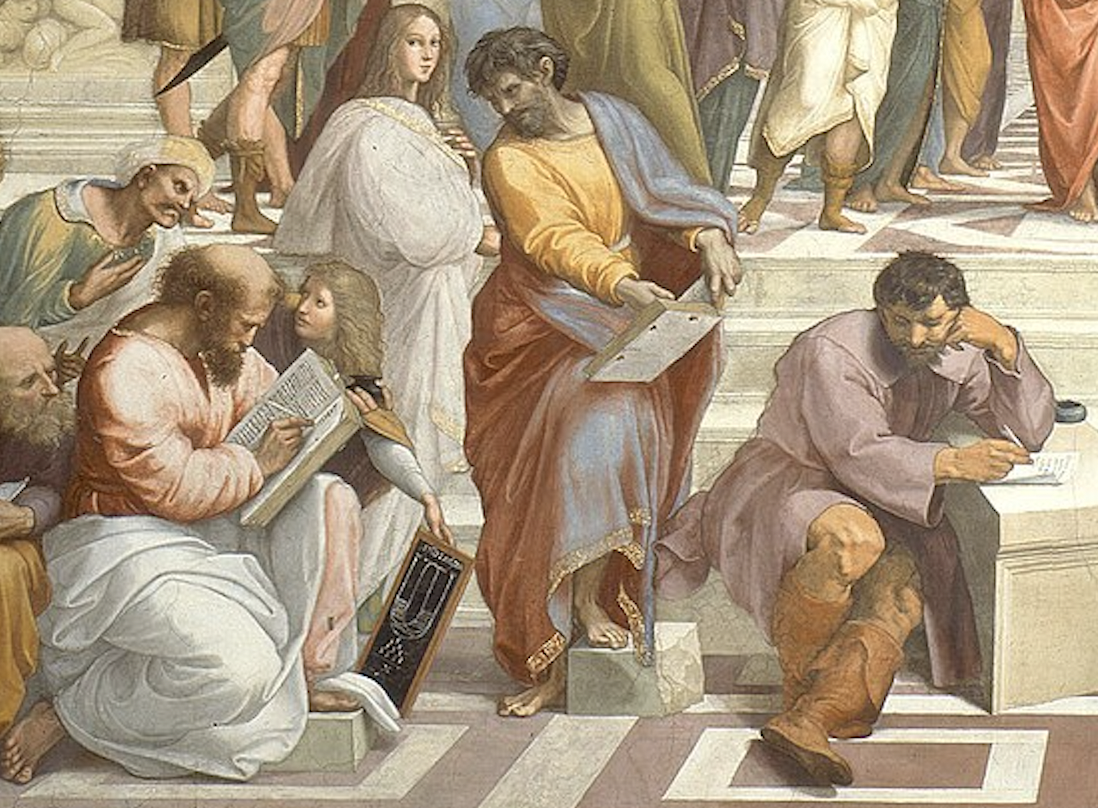

Instead, we shall focus on the remaining large fresco, about twenty-five feet across, conventionally known as the School of Athens.

The ideal of reconciliation—of synthesis and harmony—which inspires the whole room, is at the very heart of this fresco too. Raphael is trying to show that all the different branches of learning, and all the different schools of antiquity were parts of one common enterprise, which is expressed in the visual harmony of the whole composition.

Hence the ‘loners’ of philosophy are accepted—if suitably isolated—whether they speak with the sceptical voice of Diogenes (sprawling bare-legged on the steps) or with the dark paradoxes of Heraclitus (resting his elbow on a block in the central foreground) who is not so far away from another pre-Socratic, Pythagoras (crouching on the left), who is here identified with music and with the proportions of harmony.

The pagan philosophers Epicurus and Averroës (turbaned) are admitted to the congregation, even though they both denied the immortality of the soul.

Zoroaster and Ptolemy (with his back to us) stand in the right foreground, each holding a globe, one celestial, the other terrestrial.

Euclid finds pupils who are perhaps just a little over the top in their enthusiasm for the theorem that he is demonstrating on the slate—this group being the most studied and ‘balletic’ group in the whole composition.

However, without systems of proportion, there would be no classical architecture; and without geometry, there would be no theory of perspective, and hence no pictorial representations of classical architecture.

Architecture and perspective, in fact, join forces pictorially to single out and unite the two acknowledged giants among ancient philosophers.

Aristotle holds the Ethics, and gestures to this world; and Plato holds the Timaeus (a dialogue on creation), and points to the heavens. The Renaissance dream of reconciling the philosophies of Aristotle and Plato—of Minerva and Apollo—never found a more influential expression.

The painted architecture would be significant, though, even if this great atrium were totally deserted—for the same reasons that led me to devote the first lecture in this series to some of the monuments of pagan Rome and early Christian Rome.

The values of ancient civilisation are embodied in the statues of their gods, in the proportionately regulated verticals and horizontals of Greek architecture, and in the coffered barrel-vaulting of Roman engineers. Yet what you see in this fresco is a modern re-creation, a contemporary building, because the three great vaults were inspired by the designs that Bramante had produced for the new St Peter’s.

So, the Stanza della Segnatura offers a synthesis of Aristotle and Plato, of all philosophy and theology, of the old and the new; and this is why it is so satisfying to learn that Raphael included portraits of the four greatest living artists: Leonardo as Plato; Michelangelo as Heraclitus; Bramante as Euclid; and himself, modestly, as an onlooker.

Julius died in February 1513, and he was succeeded a month later by the thirty-eight-year old second son of Lorenzo de’ Medici, Giovanni, who took the name of Leo X. (Raphael’s amazing chalk-drawing is a study for his portrait of the new pope.)

He was as mild and book-loving as the portrait suggests; and contemporaries hoped that he would play Augustus to his predecessor’s Julius, by ushering in an Age of Peace.

He continued in Julius’ wake, however, by pressing on with the rebuilding of St Peter’s. (It was fund-raising for this enterprise that provoked his first confrontation with Martin Luther.)

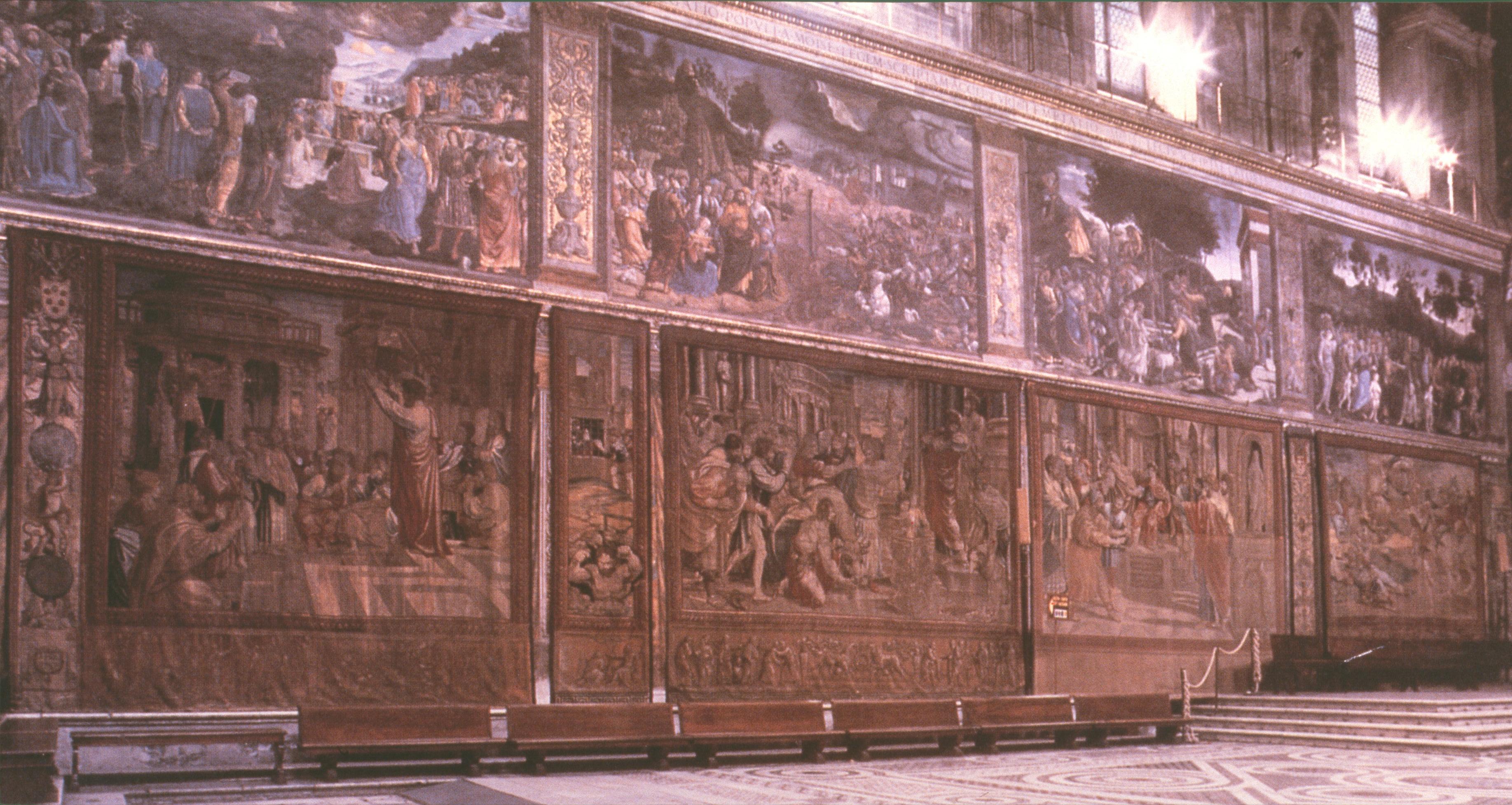

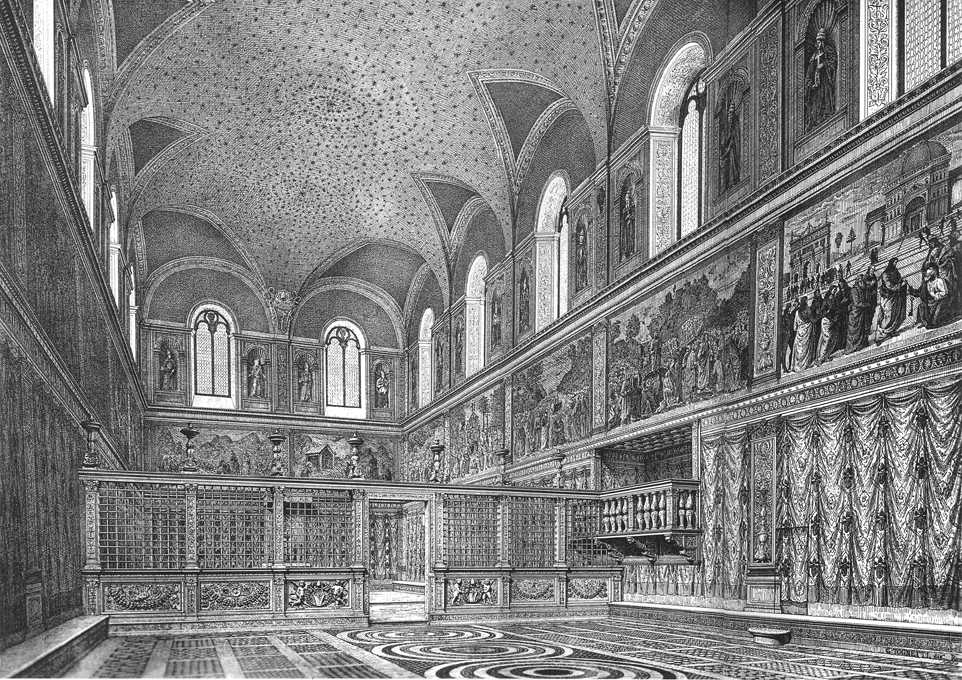

He was also faithful in spirit to Julius when he decided that the Sistine Chapel stood in need of some tapestries for the western half (the sanctuary), to be displayed on major feast days.

The tapestries would have seemed desirable, no doubt, for two main reasons, visual and conceptual. There was a need to provide a ‘counterweight’ to the ceiling which was now top-heavy, thanks to Michelangelo’s gigantic figures. And there was a need to plug the last gap in the ‘argument’ of the whole chapel.

Using the analogy of a neo-classical play, I suggested in the previous lecture that Michelangelo had ‘filled in’ three missing ‘acts’ in the ‘drama’ of Redemption. He had provided, so to speak, a first act before the existing Moses cycle (which forms Act 2), followed by third and fourth acts between the Moses cycle and the Christ cycle (which forms Act 5).

It now seemed appropriate to ‘extend’ the subject of the play so that it would include the the first thirty Popes, who had been painted in fresco in the on the walls of the Chapel (alongside the windows).

The popes would become, so to speak, the dramatis personae in Act 7 of the revised play, while a newly written Act 6 would focus on the Acts of the Apostles, and specifically on the actions of Peter and Paul, both of whom had suffered martyrdom in Rome.

Once the main decision had been taken, a whole series of other decisions followed almost automatically.

The ‘Acts’ would run as far as the screen dividing the Chapel, and they would be portrayed in tapestries of the same width as the narrative frescos on the wall above them (as the faded photograph makes clear).

A suitable woven border would also be provided to match the pilasters between those frescos.

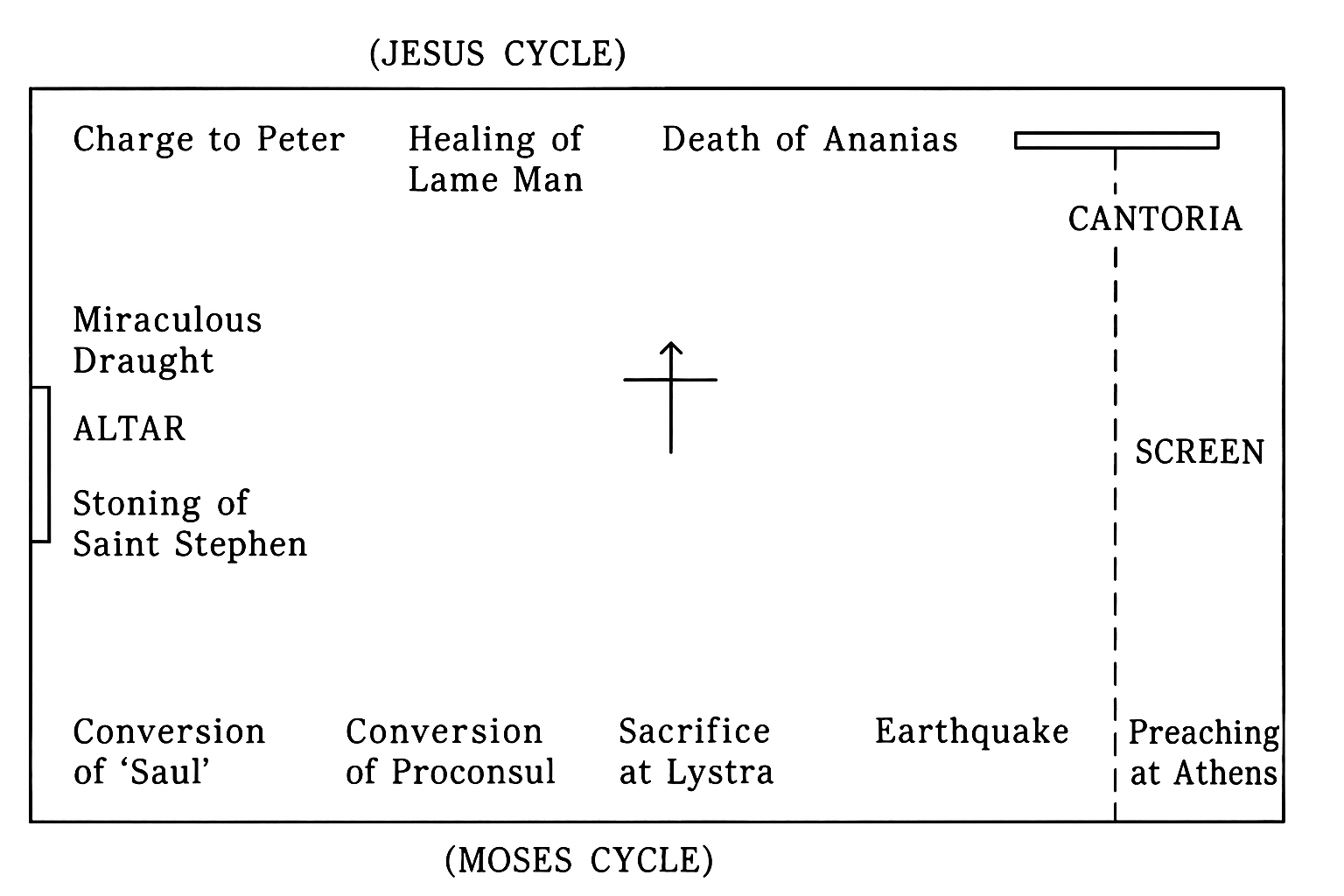

The sequence of the narratives was to begin in both cases on the Altar Wall, and proceed away from it to the right and to the left, such that the Acts of Peter (the first of the Apostles) would lie underneath the Jesus cycle, and those of Paul underneath Moses.

But the scenes would be chosen to establish precise parallels in each case between the activities of the two apostles, in order to encourage a reading ‘right, left, right, left’, just as we found in the arrangement of the thirty Popes, and the Ancestors of Christ, and the ‘Parallel Lives’ of Moses and Jesus.

Once again, the fall of light within the tapestries would be imagined as coming from the Altar Wall, and therefore from left to right on the North wall, and from right to left on the South.

You will see from my rather crude diagram that there is one notable exception to what has just been described—one notable asymmetry.

There is an extra tapestry in the Pauline cycle, which, in its original position, would have hung outside the screen, in the part of the Chapel open to the laity. (The tapestry in question is visible on the left of the photograph on the previous page.)

We will come back to the reasons for this at the end of this lecture.

The decisions about the contractors were no less straightforward.

The tapestries would simply have to be woven by specialists in Brussels; and the designs would be entrusted to Raphael and his team. In other words, Raphael would produce drawings—just as he did for the Entombment—which would eventually be enlarged to full-sized ‘cartoons’ for use by the weavers.

In principle, the procedures were almost exactly the same as in the creation of a fresco. (What you are looking at here is a surviving fragment of the cartoon for the centre of The School of Athens.)

In practice, however, there were three important differences between fresco and tapestry.

First, the cartoon had to be perfectly clear, without any pentimenti (‘changes of mind’). Hence, there would be no opportunity for second thoughts and last-minute improvisations, such as the introduction of the figure of Michelangelo (representing Heraclitus), into the foreground of the fresco of The School of Athens.

Second, the cartoon would have to be coloured, to give indications to the weavers.

Third, and most important, the cartoon would have to be drawn in reverse—as a mirror image of the desired effect.

If you want the tapestry to appear as in the upper detail, you must draw and colour what you see in the lower detail.

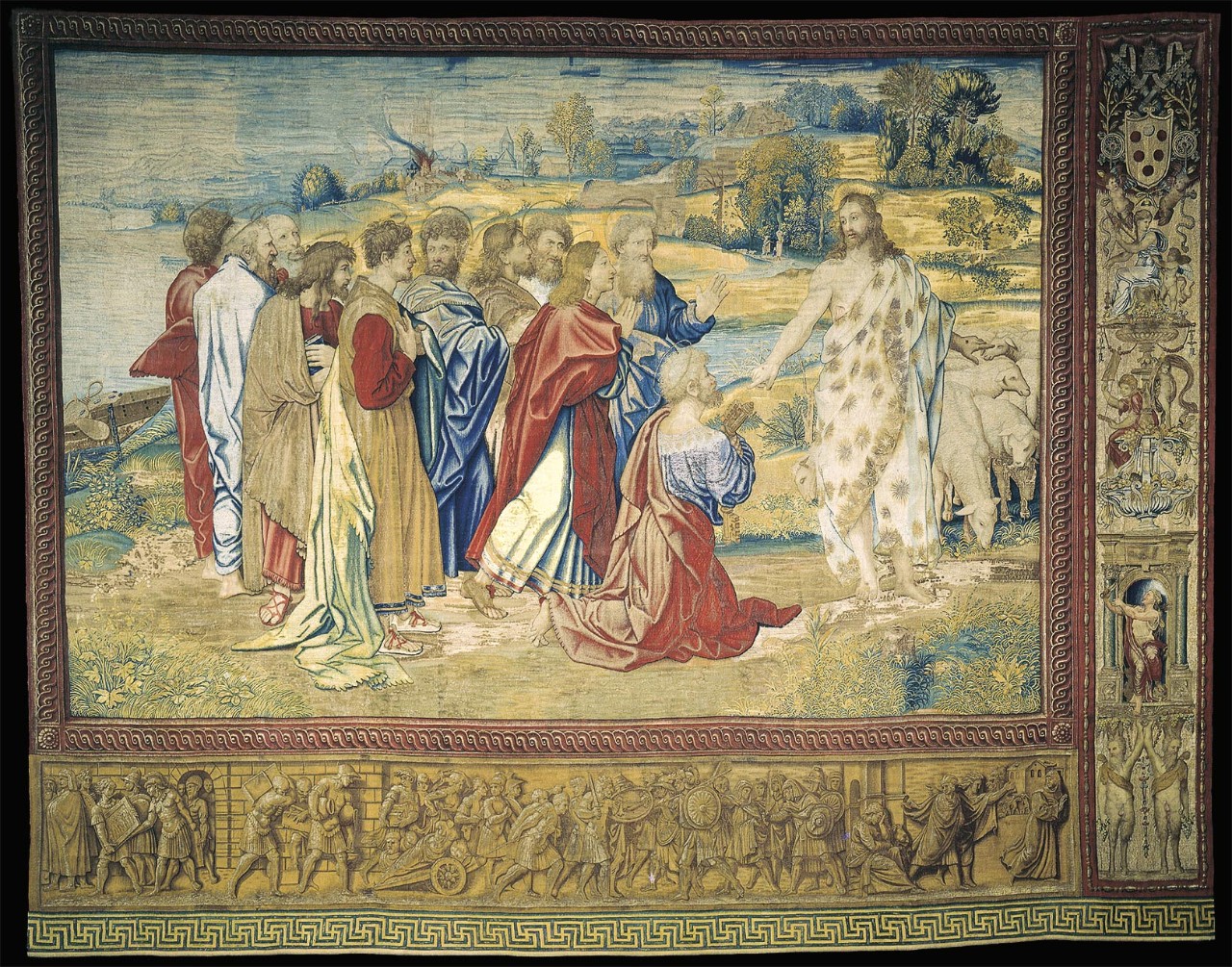

This pair of details demonstrate just how amazingly sensitive the tapestry medium could be. And if the finished tapestries—the ones actually delivered to the Chapel—were still in such perfect condition as what you see here, I would not bother with Raphael’s cartoons at all. (In fact, the detail is taken from a later weaving, using the same cartoons.)

Sadly, the Vatican tapestries, which are now on permanent display in the Pinacoteca, are both faded and abrased (and the photograph you see here is taken from a later weaving, now in Mantua).

For this reason, I am going to concentrate on the surviving Cartoons, which are now on permanent loan from the Crown in the Victoria and Albert Museum in London.

However, I am going to reproduce them in this lecture as mirror images (‘flipped’ horizontally, as we now say); and my commentary will dwell on their original purpose and their original context in the Sistine Chapel. In other words, I shall present them as ‘Parallel Lives’ of the two most important Apostles—so that we can come as close as possible to the intentions of Raphael and the Pope’s advisors.

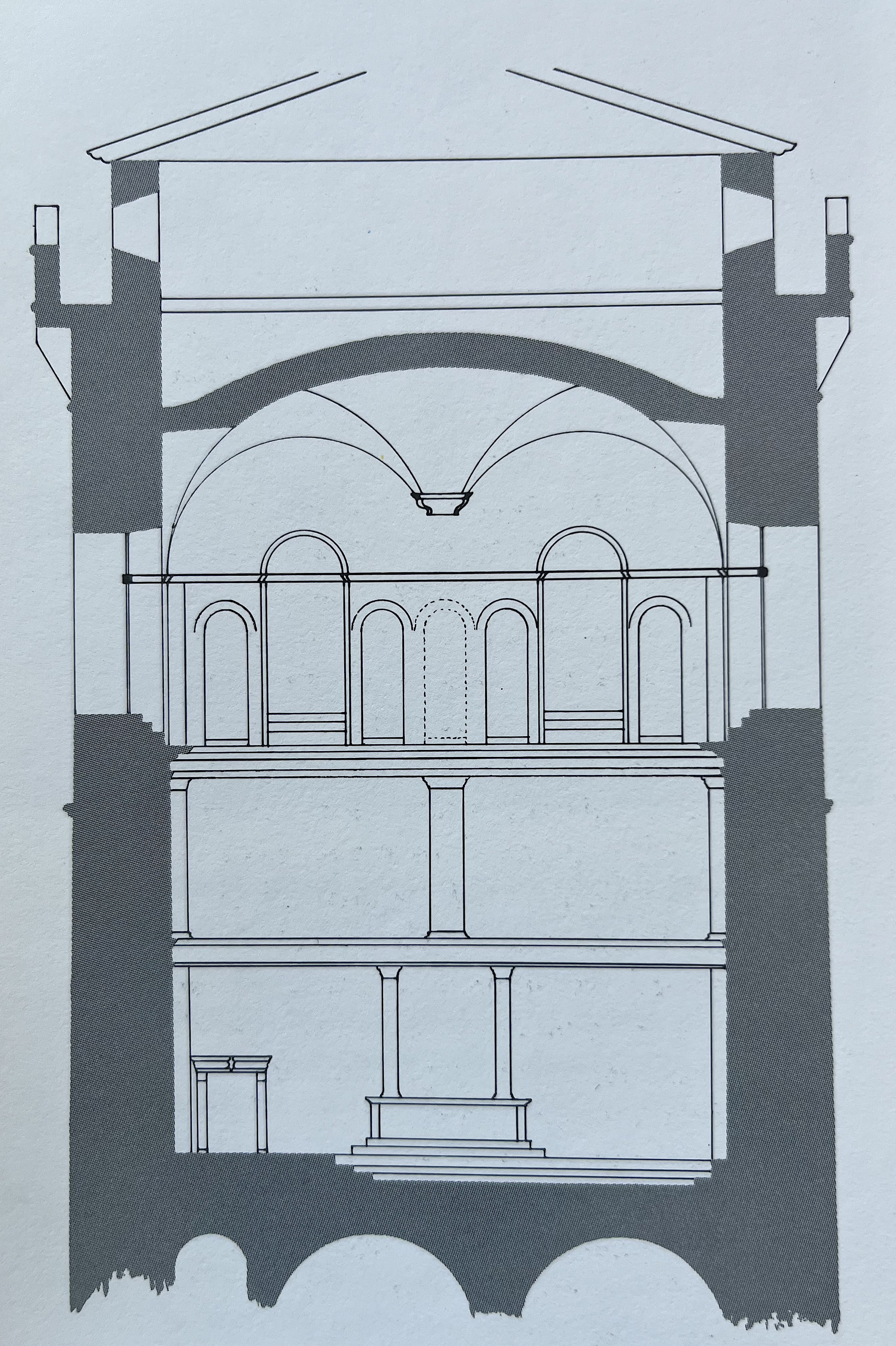

This most elegant diagram shows a cross-section of the Altar Wall in the Sistine Chapel, as it was in the year 1515.

Perugino’s first fresco in the Christ cycle (an Adoration of the Shepherds) lay to the right of the second tier in the diagram (i.e. below the windows). The same artist’s original (wooden) altarpiece lay between the pilasters in the centre of the lowest tier.

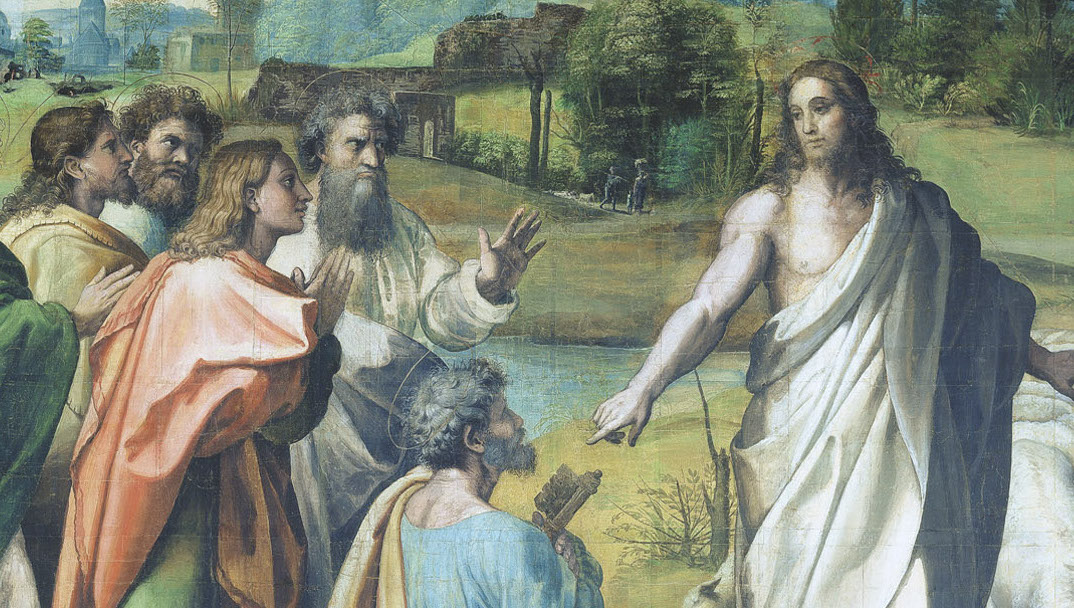

The image here is the first of Raphael’s cartoons, ‘flipped’ on the page in order to produce a mirror image of the original in which the figures and the lighting appear as they do in the tapestry.

(It is a virtual reality; but in one important way, it is more ‘real’ than what you might go and see tomorrow in the V&A.)

The size is about ten feet by thirteen feet; and the story it represents is usually entitled The Miraculous Draught of Fish. It is based on the account in the Gospel of St Luke, chapter 5, of the first significant meeting between Christ and Simon Peter.

The scene is Lake Gennesaret. Jesus preached to the people on the shore, and then said to Peter and Andrew:

“Put out into the deep and let down your nets for a catch”.…When they had done this, they enclosed a great shoal of fish; and as their nets were breaking, they beckoned to their partners in the other boat [James and John, sons of Zebedee] to come and help them. And they came and filled both the boats, so that they began to sink. But when Simon Peter saw it, he fell down at Jesus’s knees, saying, “Depart from me, for I am a sinful man, oh Lord”, and Jesus replied: “Do not be afraid, henceforth you will be catching men”.

In the second lecture of this series, we saw how Ghirlandaio had represented the same event (following the Gospel of St Matthew, chapter 14) in his one surviving fresco from the 1480s, on the North wall of the Chapel, but had relegated the boats to the middle ground of his painting, since he wanted to show the Calling of the Apostle as a solemn ceremony on the shore of the lake.

We know from a surviving sketch that Raphael, too, began by having a few large figures on the near shore, and placing the boat in the distance, very small, in the background, to the right.

Then he had the brilliant idea of using, as it were, a ‘telephoto lens’.

If you can accept the anachronistic analogy, you will understand why there only seems to be no water between the shore and the distant boats; and you will simultaneously see why the figures look unnaturally crowded together and far too big for the nearly sinking skiffs.

A further comparison with the foreground figures in Ghirlandaio’s ceremony on the shore can serve to highlight some of the most important qualities in Raphael’s art—the qualities we noted in the Entombment and in the School of Athens.

There are just six figures in Raphael—three to a boat—but there is an astonishing variety of movements, types and expressions, and a superb ‘choreography’ in the composition. (I use the term ‘choreography’ advisedly, because everything seems more like a ballet than real life.)

Zebedee, seated at the steering-oar, in profile, in a river-god pose, stares sideways, setting the group in motion. The energy increases and begins to travel along John’s back, arms and hair; it accelerates in James’s wind-swept cloak and the swing of his beardless head; and it climbs to the massive, fully bearded figure of Andrew, his hair blown forward, his arms spread in wonder.

The energy rekindles in the clearly separated figure of Peter, his arms swung forward (with highlights on right hand and elbow) as he says “I am a sinful man”; his head tilted back, his short beard jutting. And the implied movement is finally stilled in the slender, fully clothed figure of Christ, turning slightly inward, his right hand gently raised in benediction, the left arm relaxed on his knee.

The carefully paired younger men reaching down for the heavy nets and exposing their massive muscles (duly simplified for the weavers) demonstrate, in their physical type and in their poses, how completely Raphael had absorbed the influence of Michelangelo. (You would never suspect that this man had been trained by Perugino!)

The three cranes in the foreground, however, were probably painted by one of his chief assistants, who specialised in animals and birds (you may think that their poses offer an affectionate parody of Jesus, Peter and Andrew). The same assistant probably drew the numerous species of fish, which are marvellously detailed and accurate.

Raphael himself almost certainly handled the landscape of the distant shore, which is modelled on the Vatican hill (with its ninth-century wall and towers). The landscape also alludes (in an architectural caprice) to the three chief buildings sponsored by Pope Sixtus: Santa Maria della Pace, Santa Maria del Popolo, and the Hospital of Santo Spirito.

The first scene in the cycle devoted to St Paul was intended to hang on the other side of the altarpiece.

(The cartoon has been lost).

The thematic parallel with The Miraculous Draught does not really consist in anything other than the fact that the Martyrdom of Stephen is the first occasion on which our apostle is introduced by name; but Raphael has done his best to make some compositional rhymes.

For example, St Stephen echoes the pose of Peter in the lift of his head, as he gazes up to Jesus (who appears in the heavens at top right); the figure in the left foreground reaches down (just like John); while his companion rises up (rather like Andrew). The young man (negligently attired) seated on the right and turning slightly inwards, is very like Jesus in the other tapestry.

It is clearly he who has given the order for the ritual stoning of the first martyr; and this is therefore our first glimpse of the hero of the second cycle—none other than Saul of Tarsus, who had been a savage persecutor of Christians before his conversion and before his name was changed to Paul.

The landscape in this second tapestry is in fact continuous with that of the first, to which it would have been adjacent.

This continuity is significant, because the action follows immediately on a second Miraculous Draught of Fish. And what you see here is a similar crucial moment when a kneeling Peter is singled out by Jesus as the leader of the apostles.

The difference is that, this time, the scene takes place after Christ’s Resurrection.

You can tell this from the nail-marks in his hand and from the fact that he is dressed in a white garment (echoing the burial shroud). The implication was not lost on the weavers, who used masses of gold wire to create the striations of ‘glory’ which you can see in the tapestry itself.

(My reasons for choosing to flip the cartoons throughout the lecture are particularly clear in this juxtaposition.)

Having re-enacted the earlier miracle—on shore this time, after breakfast—Jesus asks Peter three times: “Do you love me?” Three times he gets the answer: “Yes”; and three times he says: “Feed my sheep” (the Latin Pasce oves is often used as the title of the cartoon).

The picture shows these purely metaphorical sheep quite literally, just as it also shows the purely metaphorical keys, which Jesus had given to Peter in the episode which had already been painted by Perugino—in the very bay of the wall where this tapestry would have been displayed (see lower detail).

The composition is not so satisfying as in the first scene, but even here the phalanx of apostles is articulated into two groups by the sixth apostle (in the green cloak) who turns around to his neighbour.

There is also another surge of energy (quieter now), moving from left to right, which becomes increasingly apparent in the greater intensity of gaze and gesture in the apostles nearest Christ (in the second detail).

Christ’s ‘two-way gesture’ is as mild as that of Michelangelo’s God (separating light from darkness, on the ceiling immediately above) was authoritarian.

The tapestry was designed to assert the special relationship between the Son of God and the metaphorical ‘Rock’ on which he had promised to ‘build his church’ (‘Tu es Petrus et super hanc Petram aedificabo ecclesiam meam’, Matthew 16:18).

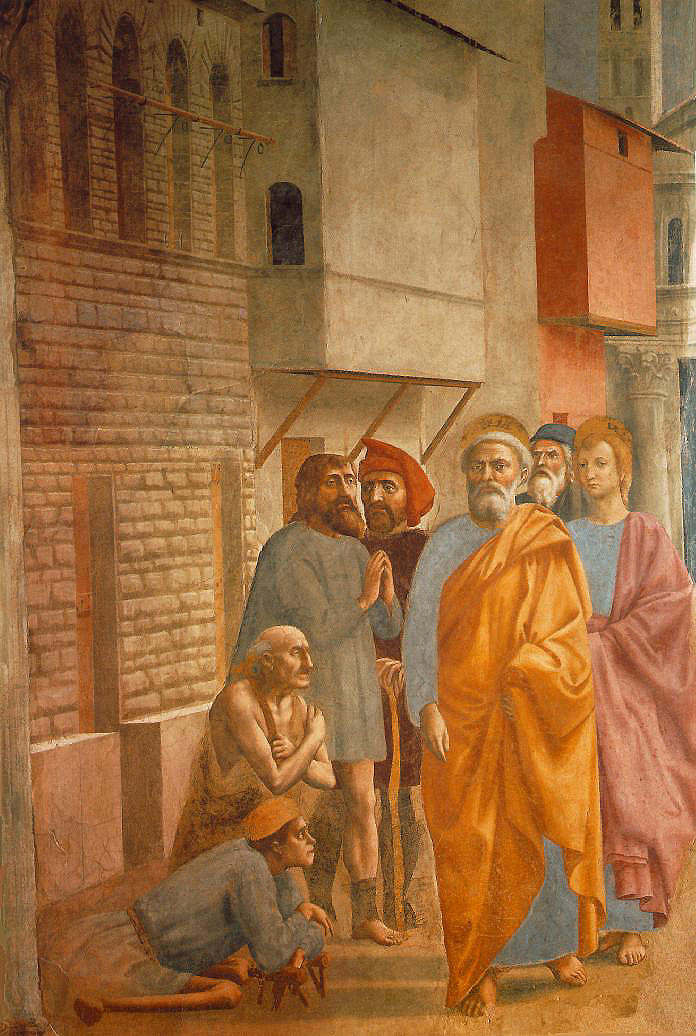

So, for our final detail from Raphael’s cartoon (duly flipped), let us focus on Peter, the hero of this cycle, represented now in his traditional colours of blue and yellow: a massive figure, with simple, heavy folds in his robe—folds which seem to have been inspired by a scene from Masaccio’s famous Peter cycle in Florence.

The second ‘singling out’ of St Paul (or of Saul of Tarsus) is infinitely more dramatic than the Feed my Sheep.

Sadly, however, only the tapestry survives; so once again I will keep commentary to the absolute minimum.

As Saul of Tarsus rides with his men towards Damascus, a light flashes from Heaven, he falls to the ground, blinded, and a voice says: “Saul, Saul, why do you persecute me?” (Acts. 9:3–9).

There are no visual rhymes with the second scene in the Peter cycle, but Raphael knows that the tapestry would hang on the South wall, and he immediately establishes that vigorous sense of movement from right to left—away from the Altar wall—that will characterise the whole Pauline cycle, just as it did in the case of the Moses cycle on the wall above these tapestries.

The next scenes in both cycles are devoted to the first recorded miracles by the protagonists.

The tapestry for Peter was to be hung below the Botticelli fresco on the North wall, the one which purports to show the three Temptations of Christ in the Wilderness (Matthew chapter 24) but gives pride of place to a Blood Sacrifice taking place in front of the Temple in Jerusalem.

I am showing Botticelli’s fresco—which I discussed in the second lecture of this series—to remind you that the façade of the Temple (in his vision) was inspired by that of the real Basilica of Old St Peter’s (which had been the real model for the façade of the Hospital of Santo Spirito, founded by Pope Sixtus IV, the uncle of Julius II).

Peter’s first miracle was the Healing of the Lame Man, which took place in the Golden Gate in front of the Temple of Jerusalem (whose dimensions, you may remember, are the same as those of the Sistine Chapel).

What you see here—flipped—is Raphael’s cartoon for the central tapestry of the three tapestries that were displayed in the western half of the Chapel, the part reserved for the officiants.

Compositionally, the cartoon itself is divided into three by the twisted columns of the so-called ‘Gate Beautiful’ in the Temple; and the main action is represented in the centre.

The story is told in chapter 3 of the Acts of the Apostles, immediately after the Descent of the Holy Spirit at Pentecost:

Peter and John were going up to the temple at the hour of prayer…and a man lame from birth, whom they laid daily…at the Gate Beautiful…asked for alms.

Peter said: “I have no silver and gold, but I give you what I have. In the name of Jesus of Nazareth, walk”. And he took him by the right hand and raised him up; and immediately his feet and ankles were made strong. And all the people…were filled with wonder…

We have already noted that Raphael had looked to Masaccio’s Peter cycle in the Brancacci chapel in Florence as a model for the massive figure style of Peter and the other major figures; and you can sense a similar debt to Masaccio’s version of the same miracle.

However, the differences are even more revealing. Whereas in the Masaccio we have a realistic, contemporary street scene in Florence and a feeling of stillness, Raphael crowds his scene with no fewer than four rows of exotic columns (believed to be archaeologically exact), which have the same curves and movements as his human figures.

Once again, it is their gestures, and the grouping, which carry the action from the left. Focus on the man’s profile and arm, the turn of the young mother’s head, and the rising, ‘kneeling’ figure of the cripple who seems to support the healing movement of Peter’s right arm.

In the middle section, this movement may seem to change direction because of the downward gesture of John’s massive arm and the direction of his gaze. But the effect is countered, in this centralised composition, by the rising of the cripple, and then, from the right, by the rush of the man half hidden by the column, the calm advance of the young women, and the complex poses of the two dancing putti. (Just try to imagine these boys in Masaccio’s street in Florence!)

The first miracle by St Paul was designed to hang opposite. It too has an indoor setting, and it too is powerfully centralised by the architecture, with its complex arches and openings to the right and the left, the perspective lines on the tiled floor, and the centrally-placed throne.

Yet in this case the architecture is classical, not oriental, for this is the courtroom of a Roman proconsul (hence the bay leaf on his brow); and the miracle involves not healing, but blinding, as the energy travels from right to left—away from the Altar Wall—from Paul to Elymas.

The story is told in Acts, chapter 13; and the scene is set in Cyprus, in the town of Paphos. Paul (or Saul, still, for the last time) has been summoned to preach by the Roman proconsul, who is described as ‘a man of intelligence’.

Elymas, the magician…withstood him, seeking to turn the proconsul away from the faith. But Saul…filled with the Holy Spirit, looked intently at him and said: “You son of the devil…. behold, the hand of the Lord is upon you, and you shall be blind…for a time”. Immediately, mist and darkness fell upon him and he went about seeking people to lead him by the hand. Then the consul believed.

I show you the tapestry so that you can read the inscription (the weavers were not fooled by Raphael’s failure to ‘reverse’ the inscription):

It says: ‘L. Sergius Paulus, proconsul of Asia, embraces the Christian faith by the preaching of Saul’.

(It was after this episode that Saul took the name of Paul.)

The expression on the proconsul’s face, his upraised hands, the legs placed to suggest he is about to spring to his feet, are those of a man who has been converted by a marvel.

His pose also has a compositional function, though, as it serves to carry the action from right to left in the direction of the strong shadows cast on the floor, and away from the source of energy in the massive, in-turned figure of Paul. A supernatural force surges up through the folds of his mantle to his enlarged hand which launches the miraculous power so that it strikes poor Elymas, making him recoil as well as grope.

The gestures of the seven hands in this final detail from the Conversion of the Proconsul may be studied at your leisure as a microcosm of all Raphael’s aspirations as storyteller and ‘choreographer’.

(As for their execution, remember that he wanted to simplify everything as a guide for the the weavers. The hands in the cartoons are deliberately not in the same league as those in his drawings).

For our immediate purposes, however, we need to do a little rapid revision with the aid of my diagram.

The titles of the cartoons remind you that we have studied, on the north wall (in the top line): the Miraculous Draught of Fish, the Charge to Peter (alias ‘Feed my sheep’), and the Healing of the Lame Man; and on the south wall: the Stoning of Stephen, the Conversion of Saul, and the Conversion of the Proconsul.

The layout in the diagram reminds you that each scene in the ‘Petrine’ sequence is matched—thematically and compositionally—with its opposite number in the ‘Pauline’ sequence.

The composition places the figures further away from the spectator than in the Blinding of Elymas, but the story is once again concerned with the transmission of spiritual energy of a destructive, punishing kind.

The apostles (led by Peter) now have many followers. They have agreed to sell all their possessions and give everything they have to the community; and ‘distribution was made as each had any need’.

(On the left, they bring; on the right, they receive.)

The story is told in Acts chapters 4 and 5:

But a man named Ananias, with his wife Sapphira, sold a piece of property, and he with his wife’s knowledge kept back part of the proceeds, and brought only a part, and laid it at the apostle’s feet.

But Peter said “Ananias, why has Satan filled your heart to lie to the Holy Spirit…?”

And when Ananias heard these words, he fell down and died, and great fear came upon all who heard of it.

The message is the same as that of the fresco in the fifteenth-century Moses cycle concerning the rebellion of Korah: those who defy Peter and his successors will ‘perish utterly’.

Notice that Ananias sprawls back to the left, against the ‘direction’ of this wall, but the main ‘shock wave’ of energy does go from the left towards the recoiling youth and young woman on the right in the most balletic movement in the whole sequence.

(These two details may also be revisited as microcosms of Raphael’s aims and aspirations as a narrator and choreographer.)

We have now completed our study of the cartoons dealing with Peter; and we must return to the Pauline cycle, which is longer by an extra narrow strip and a whole scene.

To understand the reasons for this, we must return in imagination to the Sistine Chapel in 1515 (of which you are reminded again in this superb nineteenth-century reconstruction of the original layout).

As the engraving suggests, the beautiful marble screen used to divide the area exactly in half, with three window bays in each part.

The screen used to intersect the balcony used by the singers (the ‘cantoria’) which you can see on the right of the reconstruction, dividing it so that roughly one third lay on the papal side and two thirds on the side of the laity.

To balance this ‘cantoria’, a very narrow tapestry was commissioned to go inside the screen, and one extra, large tapestry was commissioned to hang outside—and in a moment, you will see how brilliantly this necessity was turned into a virtue.

A preliminary word or two of explanation is required, however, because the last two major scenes in the Pauline sequence do belong very much together; and they combine to re-express the themes of the ‘Stanza della Segnatura’ and the themes of the first lecture in this series—that is, they are the expression of attempts made by successive popes of the Renaissance to harmonise Christianity with the best elements in classical civilisation.

Peter’s activity was directed primarily at the Jewish communities, whereas Paul concentrated on the pagans or Gentiles; and the last two full-sized cartoons show him dealing with that pagan world in its two most characteristic manifestations.

He will be faced, first, with popular idolatry in a provincial city of Asia Minor, and then by more sophisticated philosophers in the intellectual capital of the ancient world, Athens.

The title of this cartoon is The Sacrifice at Lystra.

Look, first, at the classical buildings, the marble statues, and the ritual of pagan sacrifice (painstakingly reconstructed from the best evidence available in 1515), in the little city of Lystra in Asia Minor.

The story is told in chapter 14 of the Acts of the Apostles.

Paul has just healed a man who was lame from birth (his crutches being visible on the ground) and: ‘When the crowds saw what Paul had done, they said: “The gods have come down to us in the likeness of men”. They called Barnabas Zeus, and Paul Hermes’.

(You can see the statue of Hermes, with his caduceus, on the pedestal in the centre.)

‘They brought oxen and garlands to the temple of Zeus, and they wanted to offer sacrifice. But when Barnabas and Paul heard of it, they tore their garments, and rushed out, crying “Men, why are you doing this. We also are men, of like nature with you, and we bring you good news”’.

Notice that the main surge of the action is from left to right, because Paul is here meeting opposition, and not overcoming it.

Once again, though, he is placed on the extreme right; and although his arms are not outstretched (as they were in the Conversion of the Proconsul, and will be again in the final scene), the cast shadows and the apostle’s spiritual energy still move away from the altar, from right to left.

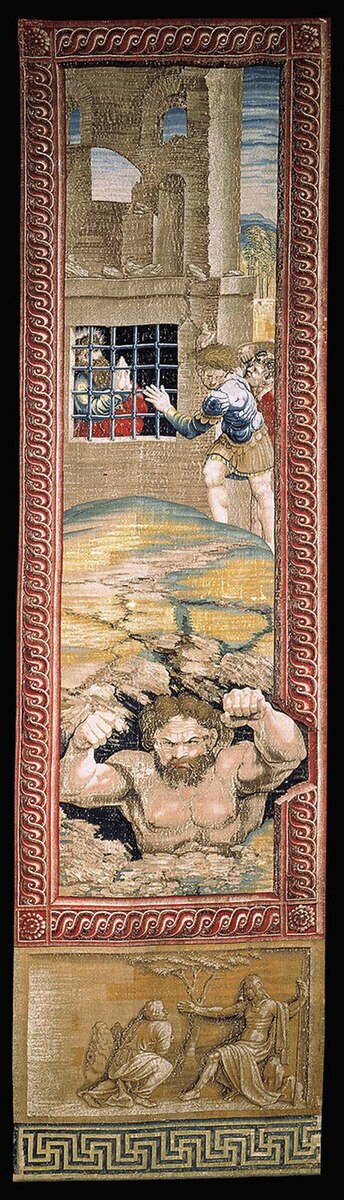

I will not delay on the little strip that was intended to hang just inside the marble screen.

The cartoon is lost, but the tapestry affords a moment of light relief. The story comes from Acts, chapter 16, after Paul has been beaten and thrown into prison. (His is the face behind bars in the grille.)

‘About midnight…there was a great earthquake, and the foundations of the prison were shaken’.

(Incidentally, Paul refused to escape: the point of the episode is that the jailer was converted by his behaviour. The ‘pugilist’ among the broken flagstones at the bottom of the tapestry is a representation of the Earth Giant who caused the ‘significant tremor’.)

Imagine yourself now on the eastern side of the screen, standing in the area where the final tapestry in the Pauline sequence was intended to be hung.

Paul has come to Athens, which is symbolised above all in the round temple—a ‘tempietto’ (like Bramante’s tiny San Pietro in Montorio).

Indeed, he has come to the very heart of Athens, the Areopagus, named after the war god, Ares (Mars), whose bronze statue you see in rear-view, with spear and shield, in front of the temple.

Paul has come to beard the lion in his den, so to speak; that is, he has come in order to preach to men worthy of his intellect—Epicureans and Stoic philosophers.

Paul has taken up his position, right, nearest the altar, so that he seems to be talking to the laity in the Sistine chapel as well as to the Athenians in the tapestry.

He has raised both his arms to irradiate a benign spiritual energy; and he is preaching one of the shortest, most densely argued, and most persuasive of all sermons in the long history of the genre (Acts, 17:22–31).

He begins by quoting an altar-inscription and he ends with two lines of poetry in Greek. He insists that there is only one God, creator of all things, who wants all mankind, all over the inhabited world, to search for him in his creation and in their own souls. And he ends by asserting Christ’s Resurrection.

Here are the sentences most relevant to our cartoon:

“You Athenians, I see that in every respect you are very religious. For as I walked around looking carefully at your shrines, I even discovered an altar inscribed, ‘To an Unknown God’ (22).

What therefore you unknowingly worship, I proclaim to you (23).

The God who made the world and all that is in it, the Lord of heaven and earth, does not dwell in sanctuaries made by human hands.…It is he who gives to everyone life and breath and everything (22–25). He made…the whole human race to dwell on the entire surface of the earth, and he fixed the ordered seasons and the boundaries of their regions (26), so that people might be lured to seek God,…though indeed he is not far from any one of us (27), for in him ‘we live and move and have our being’—as even some of your poets have said: ‘For we too are his offspring’ (28).

‘When they heard of the Resurrection of the Dead, some mocked’, ‘but others said: “We will hear you again about this”. Some joined him, and believed, among them Dionysius the Areopagite, and a woman named Damaris.’

In the figure and the pose of Dionysius—middle aged, burly, kneeling, adoring—there is more than a hint of Peter kneeling before Jesus at the beginning of the whole cycle; while the two philosophers in the upper detail are clearly pondering over the strange conclusion of the sermon.

There are hosts of other details I would like to dwell on (not least, the portrait of Pope Leo among the listeners; for he it was who commissioned the tapestries). But I prefer to round the lecture off at this point by restating its main themes and the main thrust of the complex argument embodied in almost every feature of the decorations in the Sistine Chapel between 1485 and 1525.

This can be done, very economically, by simply juxtaposing excerpts from the Latin text of St Paul’s homily to the Athenians alongside The School of Athens and the final Tapestry Cartoon (displayed here as it was when it left Raphaels’ workshop on the way to Brussels and as it can be seen in the Victoria and Albert Museum).

St Paul: ‘Quae est haec nova doctrina?’ (Acts 17:18–28, excerpts)

Quidam autem Epicurei, et Stoici philosophi disserebant cum eo

(18).…Et apprehensum eum ad Areopagum duxerunt, dicentes: ‘Possumus

scire quae est haec nova, quae a te dicitur, doctrina?’ (19).

Stans autem Paulus in medio Areopagi, ait: “Viri Athenienses (22)…,

praeteriens enim, et videns simulacra vestra, inveni et aram, in qua

scriptum erat: IGNOTO DEO. Quod ergo ignorantes colitis, hoc

ego annuncio vobis (23).

“Deus, qui fecit mundum, et omnia quae in eo sunt, hic caeli et terrae cum sit Dominus, non in manufactis templis habitat (24), nec manibus humanis colitur indigens aliquo, cum ipse det omnibus vitam, et inspirationem, et omnia (25).

“Fecitque ex uno omne genus hominum inhabitare super universam faciem terrae, definiens statuta tempora et terminos habitationis eorum (26), quaerere Deum si forte attrectent eum…, quamvis non longe sit ab unoquoque nostrum (27).

In ipso enim vivimus, et movemur, et sumus: sicut et quidam vestrorum Poetarum dixerunt: Ipsius enim et genus sumus.” (28)