This ‘Story from Siena’ used to form part of an altarpiece on the high altar of the Cathedral.

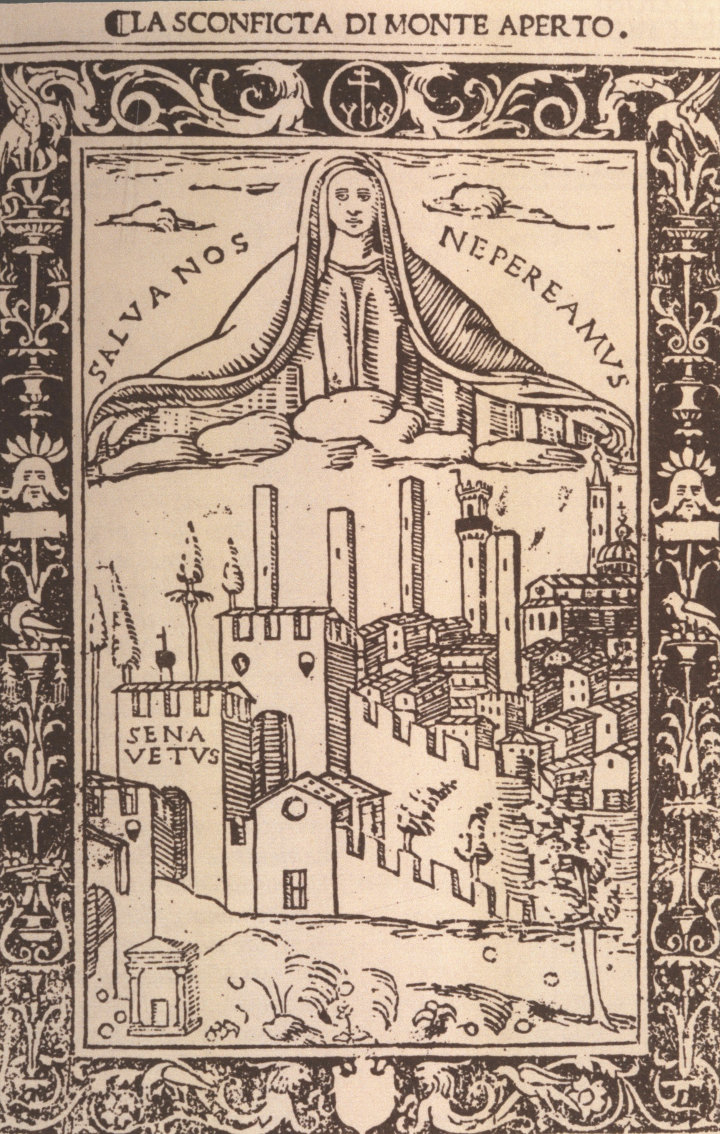

As was noted in the previous lecture, the Cathedral was dedicated to the Virgin Mary; and in 1260, just before a decisive victory over Florence, at Montaperto, the whole city—clergy, nobles, and ‘popolo’—had re-dedicated itself to the Virgin.

Both of them were painted between 1275 and 1285, but still retain the combination (which we saw in the 1215 altarpiece) of a large, public image (respectively, St John the Baptist and St Peter) which is visible from the back of the Church, and small narratives scarcely a foot high, visible only to the celebrant. We shall look at one panel from each, to remind ourselves of the state of the art of painting in Siena in about 1280.

The detail from the first shows the newborn John the Baptist being presented to his mother Elizabeth in the presence of two very tall and slim midwives. There is more than a hint of an attempt to create pictorial space for the actors, since the left wall is meant to be in perspective, the bed has depth, and the haloed woman (the Virgin Mary) is standing on the far side of the bed, but the artist is still essentially content to use brightly coloured ‘pictograms’ to suggest the buildings, and the whole is very characteristic of Sienese art in its love of gold and in the strong warm colours.

The detail from the second shows the ‘Calling’ of Peter (and his long haired brother, Andrew). It is marvellously simple with its stylised brown promontory on which Christ is standing, the slashes of white used to define the folds on the pink rock, the translucent green of the Sea of Galilee (in which we can see fish, clearly drawn from life), and the one-oared coracle into which Andrew is hauling up the net.

It is absolutely charming in every way and very similar in scale and colour to the scenes in Duccio’s Passion Cycle. But it is utterly unlike Duccio in its naivety.

To understand the differences between the image from 1280 and that from 1310, we have to recognise that we are now in the presence of genius, but we must also remind ourselves of the ‘mind-bending’ achievements of other artists in Italy during the thirty years that separate the two pictures. If there is a common element in the developments of those years, it is that the art of painting was trying to emulate the art of sculpture, while the sculptors were not without some influence from the painters.

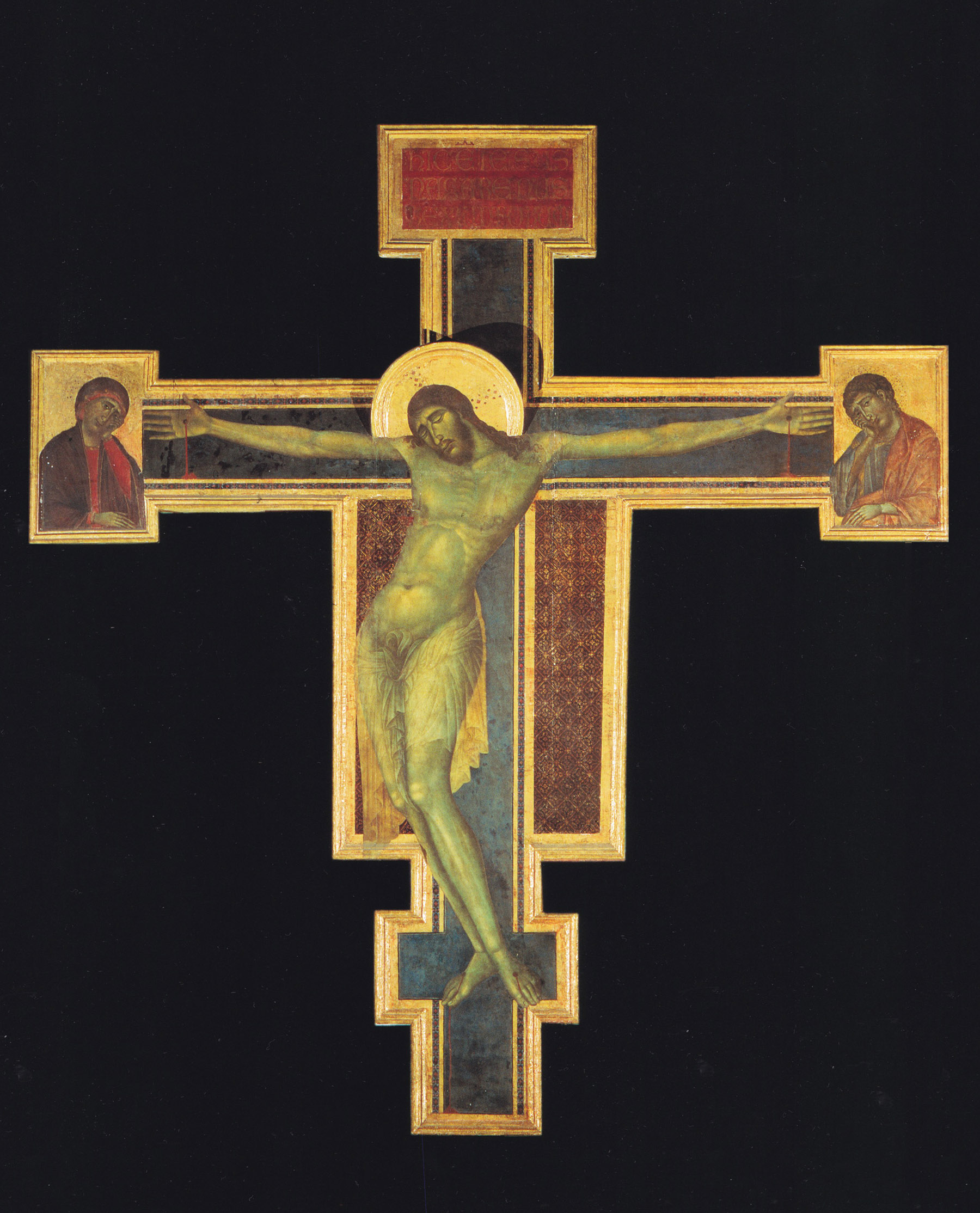

The point is very nicely made by Professor John White, who in his Pelican History of Art in Italy 1250–1400 shows us two objects as apparently distinct as a crucifix, from about 1260 (another combination of a large devotional image and little narratives, executed by Coppo di Marcovaldo, a Florentine who was captured by the Sienese at the Battle of Montaperti) and a tomb for the French Pope, Clement IV in the city of Viterbo (done between 1271 and 1274 by a sculptor called Pietro d’Oderisio).

They are quite distinct objects, but if you look at the two heads side by side in black and white, you can see that the boldly chiselled sculpture, with its strong sense of being ‘from the life’, is not uninfluenced by the painting in such details as the low forehead, the eyes, the long nose, the cheek, the set of the lips—in a rendering of the face that was to become a widely diffused type of Jesus patiens, (Jesus suffering on the cross), but was still relatively new in the 1260s.

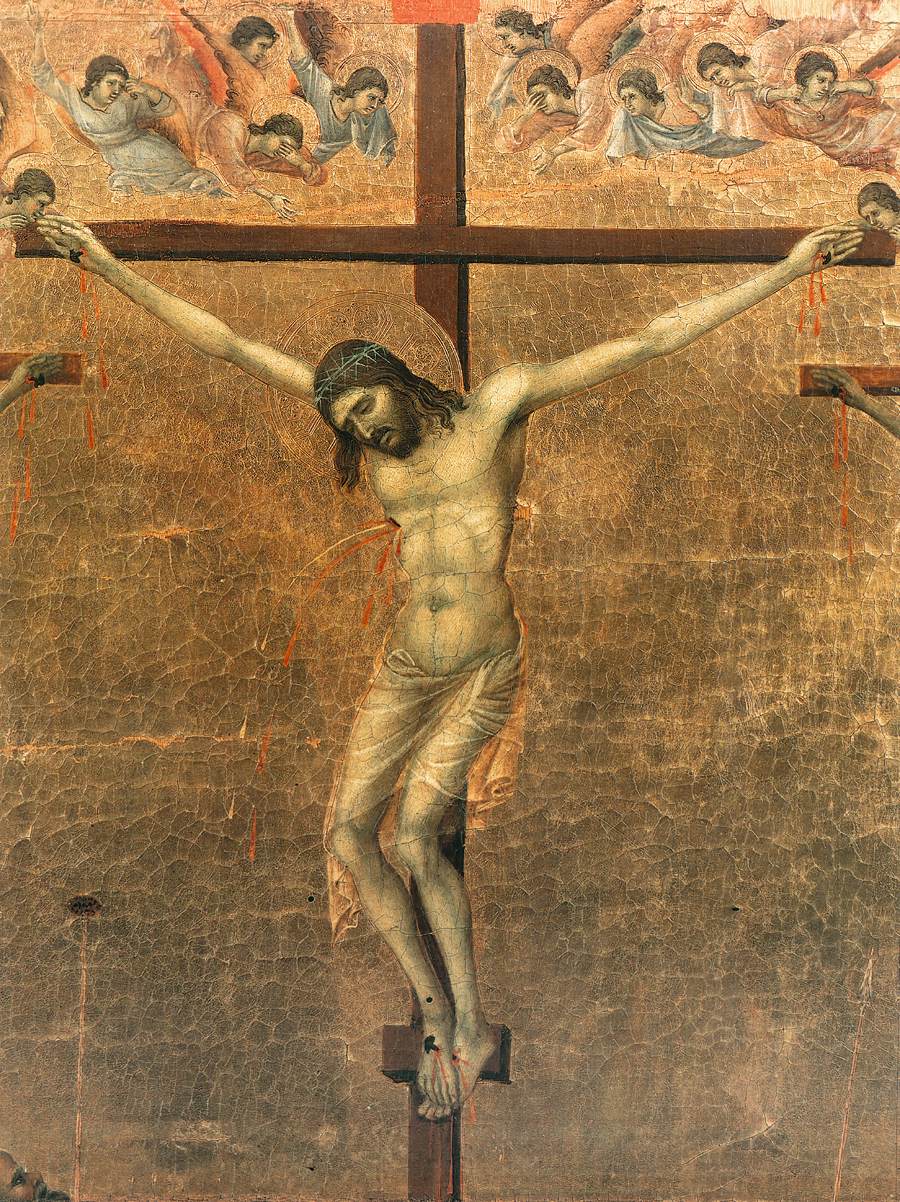

Having concentrated for a moment on the face in Coppo (c. 1260), take a good look now at Cimabue’s famous Crucifix of the 1280s—focussing on the treatment of the abdomen, the loin-cloth, the incipient ‘swing’ of the body.

You will see immediately why Dante would write that Cimabue ‘thought he held the field in painting’: the ‘mask’ is now almost a human face, the flesh is soft and round, the transparent loin-cloth rendered with marvellous delicacy.

Cimabue’s image was to be seen in the Franciscan church of Santa Croce in Florence from the mid-1280s; but in those same years, you might have stayed in Siena itself and stared at the large statues which Nicola’s son Giovanni was carving for the façade of the Cathedral.

This one has been brought indoors for protection, but you should imagine the brooding features looking straight at you—and seeing straight through you—from about 30 or 40 feet above your head. It is stone with the power of thought.

Setting out from Siena, any artist in the mid-1290s could have walked along the ‘Frankish Way’ to Rome, to see Pietro Cavallini’s work in mosaic and in fresco in two churches in Trastevere, not far from St Peter’s.

There, they would have been astonished to see a fresco showing life-sized apostles in the Last Judgement—a fresco which is quite amazingly advanced in the confident, ‘space-creating’, foreshortening of the thrones, and above all, in the highly convincing ‘relief modelling’ of both the thrones and the human figures, by means of a consistent simulation of the fall of light, as though it came from a source high up on the right-hand side, illuminating some surfaces while leaving others in darkness.

The modelling is even more more convincingly three-dimensional in the Church, because the real source of the illumination is, precisely, in the high window to the right of the painting.

From Rome, one could travel north up the valley of the Tiber and follow the development of this monumental style in the upper church of St Francis at Assisi, where a team of artists, possibly including Giotto, was painting the life of St Francis in 28 large frescos.

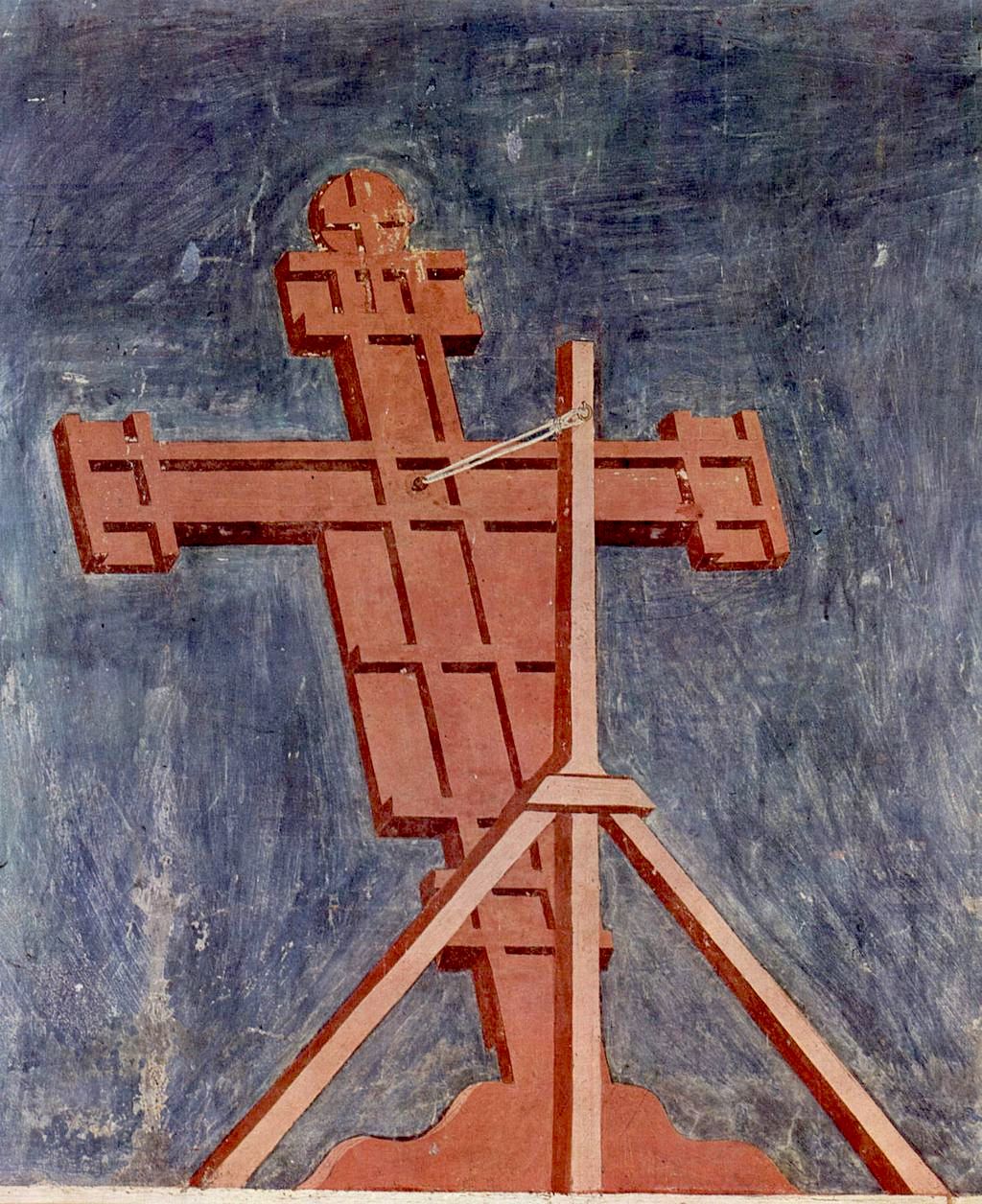

We shall study a few of these frescos in the next lecture, but I show you just one of them here in order to illustrate the astonishing advance in the creation of space by means of perspective and foreshortening.

We are in the choir of a church, looking towards the rood screen that separates us from the nave beyond. The placing of the overlapping figures, one behind the other, and the drawing of the huge lectern and the magnificent tabernacle all serve to create a depth of at least fifteen feet in the foreground of the fresco.

Even more impressive is the drawing of the rear of the pulpit (high on the left) and of the back of the crucifix, which leans away from us towards the unseen congregation in the nave, and which therefore suggests (rather than defines) pictorial depth of a kind that had never been achieved in medieval painting before.

Whether or not the younger Giotto was active in the upper church at Assisi, we know that he was the artist-in-charge of the frescos that cover every inch of the Arena Chapel in Padua, from which I show you the opening scene in the sacred story that runs continuously round the Chapel in three tiers.

Here the Virgin’s father, Joachim (identified by the halo), is being banished from the Jewish temple—defined by a pulpit and a tabernacle like those we have just seen.

He is being banished by the High Priest, and his sacrificial Lamb has been rejected.

The principal figures are convincingly solid and three-dimensional; their focussed gazes meet each other as never before in medieval art; and the anguish in Joachim’s face is conveyed without exaggeration.

You will see soon that Duccio’s altarpiece comes as a worthy climax to this succession of masterpieces.

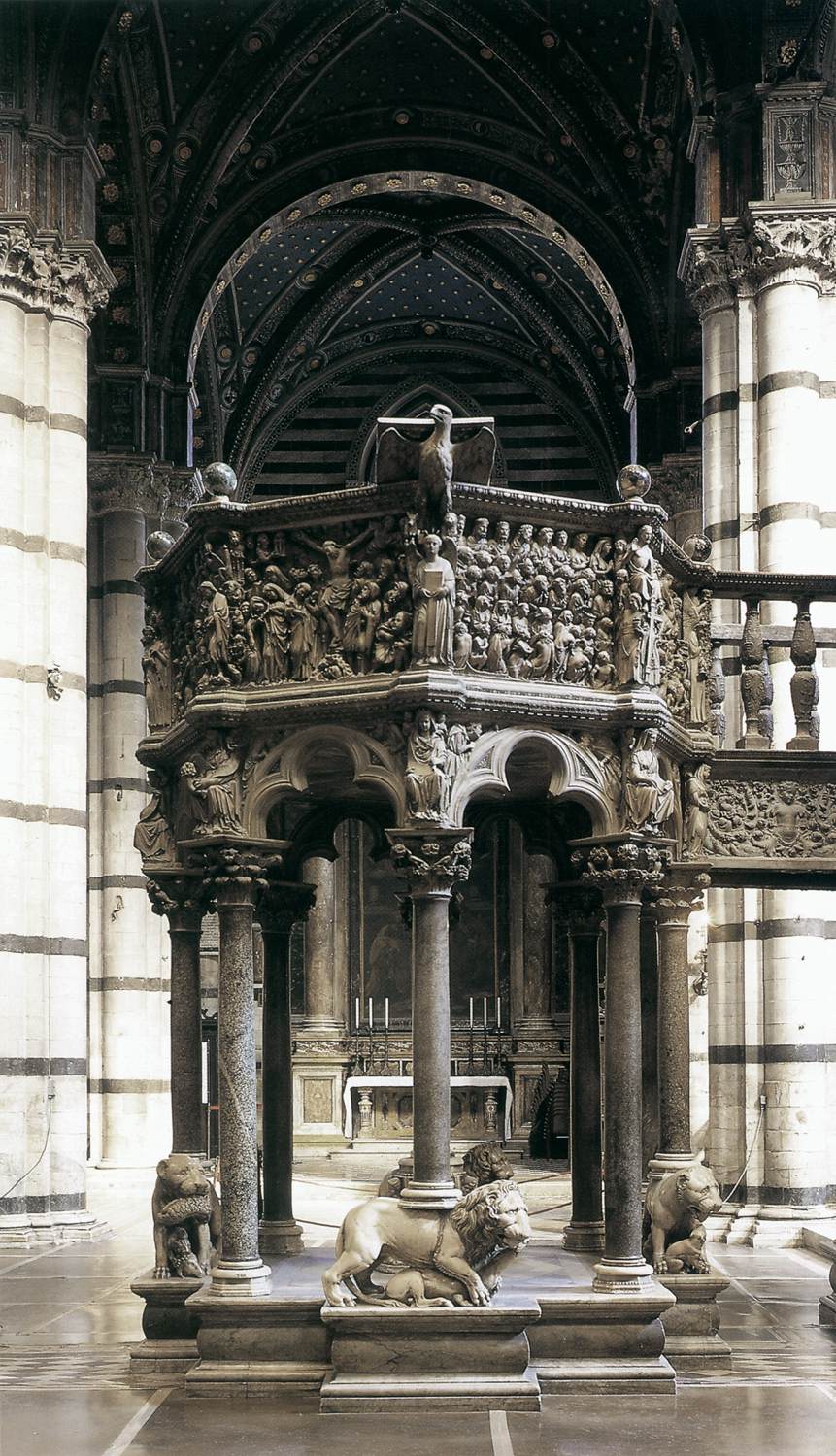

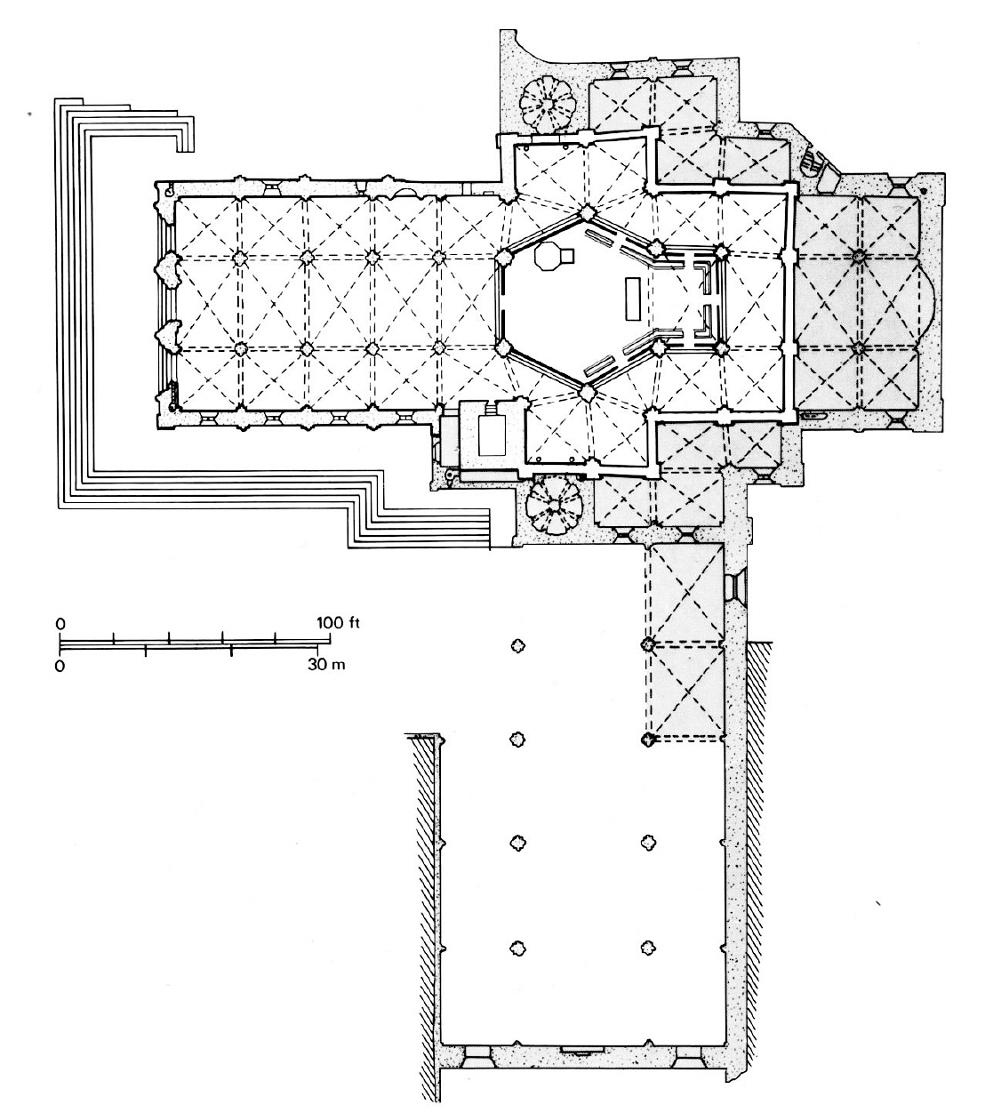

But, first, let us go back to the point where I broke off in the previous lecture—to the nave and crossing of the Cathedral of the Virgin.

At the beginning of the fourteenth century, the building did not extend much beyond the crossing, being limited to the unshaded area on the plan, so that the high altar lay very close to Nicola’s pulpit, rather than at the rear of the now extended apse.

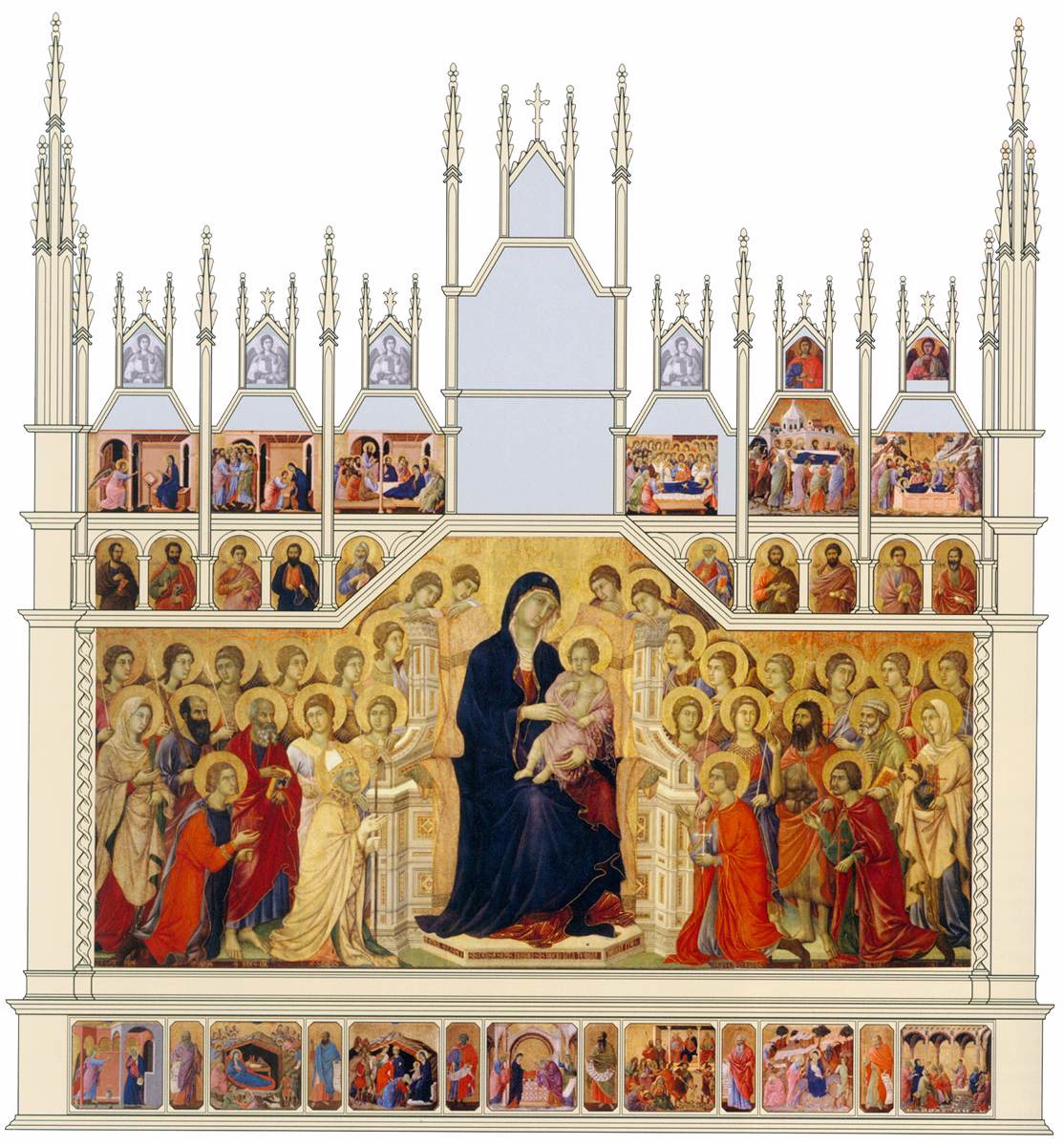

In June 1308, the most famous Sienese painter of his generation, Duccio, was commissioned to ‘construct and paint’ a gigantic new altarpiece for the altar, which he and his workshop delivered—amid vast civic celebrations—only three years later.

It was to present a huge ‘public’ image to the congregation in the nave and aisles, while the rear of the altarpiece was to be entirely covered with small narrative panels, for the instruction and pleasure of the clergy in the presbytery or ‘choir’.

The altarpiece has been dismantled for more than 200 years, the back having been detached from the front, and several of the panels dispersed (two of them have found their way to our National Gallery).

Yet the bulk of it is still to be seen, in almost perfect condition, in the cathedral museum at Siena; and the original design can be fairly confidently reconstructed, as in this photomontage of the front.

The main element in this ‘public’ surface was a single panel, fully fifteen feet across.

It shows a life-size Virgin and Child enthroned, with the four local Sienese saints (the four ‘protectors’) kneeling in intercession for the city in the front row.

In the row behind them stand major saints; and behind and above them (also surrounding the top of the throne) you can see the heads of a row of angels. In the separate rounded panels at the very top there are half-length portraits of the apostles.

As you saw in the photomontage, this central area was surrounded by lesser panels narrating scenes from the Life of the Virgin.

In the predella at the bottom are scenes from the Conception, Birth and Infancy of Jesus.

Above the apostles, there are scenes from the Last Days of the Virgin; and the empty spaces in the montage probably included her Assumption into Heaven, and her Coronation as Queen of Heaven.

I shall return in the fourth lecture to take a closer look at the front of the altarpiece, but for the moment, I would like you to dwell on the apostles, portrayed and duly named in the top row, because it is on the basis of their costumes and characterisation here that I shall be able to identify them individually in the narratives on the rear.

And, since it is her altarpiece, in her Cathedral, in her city, I should also show you Mary’s face, beautifully modelled in the round within the splendid ‘space’ created by the drawing of her headdress.

This is a good moment, too, to absorb the rhyming inscription which runs round the base of the throne:

Mater Sancta Dei

Sis causa Senis requiei

Sis Duccio Vita

Te quia pinxit ita.

Holy Mother of God

Be the cause of Peace for Siena

Be Life to Duccio

Because he painted you thus.

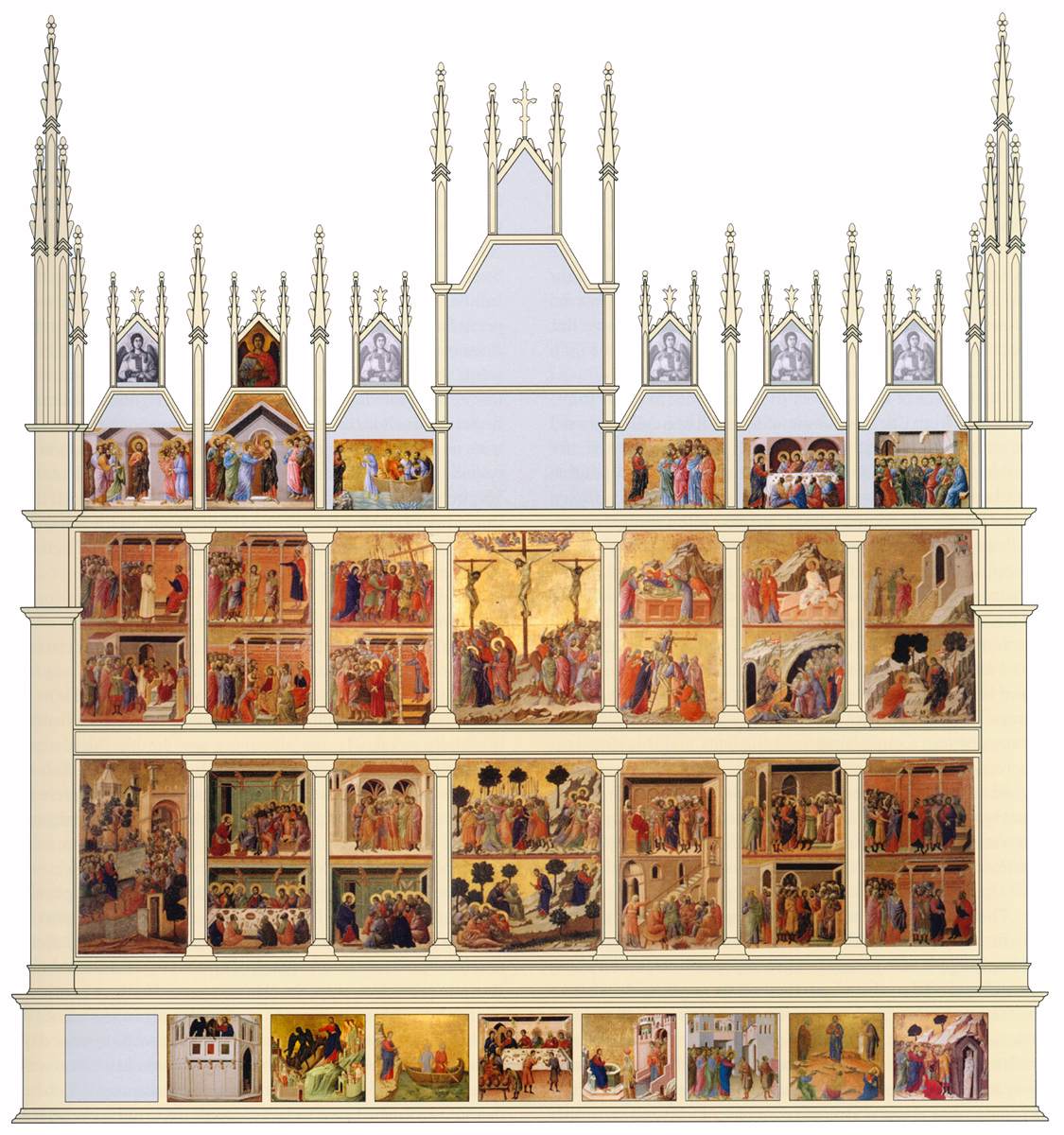

The rear side of the altarpiece has exactly the same area of painted surface; and this was devoted entirely to Jesus.

On this ‘private’ side, however, everything was scaled down to the intimate dimensions of the presbytery, and there are no life-size figures—the whole area is given over to narrative.

The sequence of the scenes is an ‘ascending’ one, beginning with Christ’s Mission and Miracles in the predella (which we shall not examine), then climbing through the Passion Cycle to reach the first two appearances of the Risen Christ (top right in the main panel).

The story continued in the six now-dispersed panels (reassembled in the upper row of the photomontage) with Christ’s subsequent appearances until the Day of Pentecost, while the missing panels (assuming the reconstruction is correct) would have shown his Ascension and a Christ in Glory as Redeemer of the World.

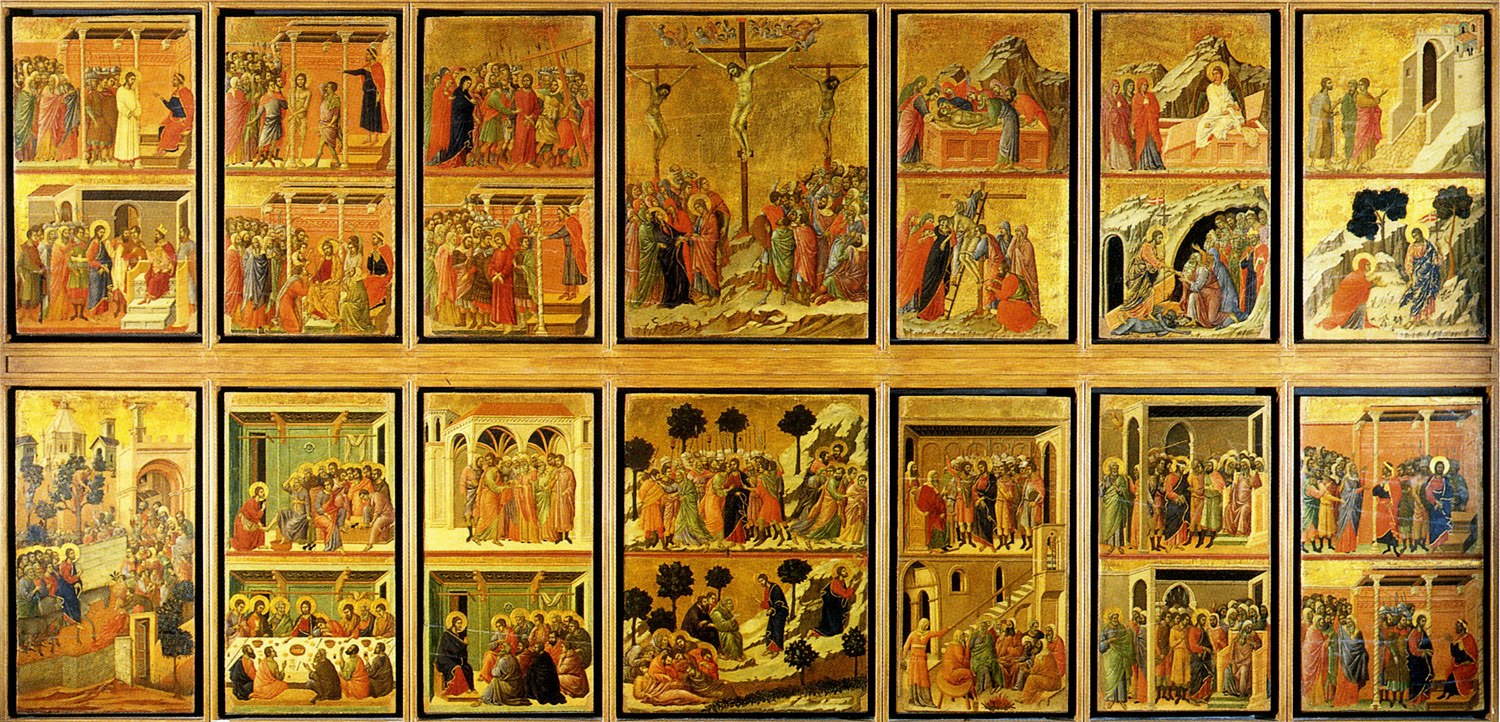

By now, you will be dying to get on with the story, but before we do, I must make a few points about the layout of the 26 scenes.

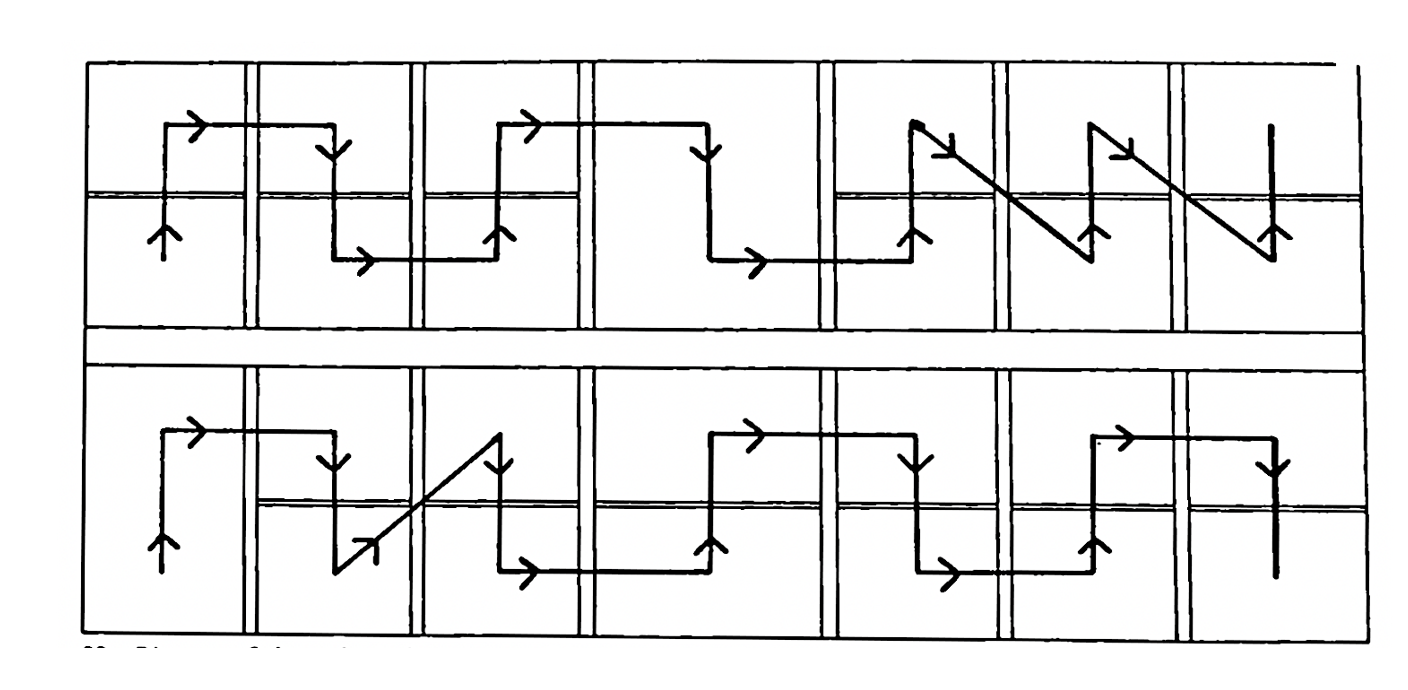

Generally speaking, they are arranged in four rows, with two blocks of three square panels (the sides being just under two feet) on either side of a broader central panel. The first oddity is that they are not really ‘panels’—that is, they are not separate pieces of wood held in a frame—because the whole surface consists of just five planks laid horizontally. The second oddity is that the broader, central panels in the upper two rows are treated as one unit. So, too, are the smaller panels on the left of the bottom two rows.

These oddities are a clue to the most unusual sequence in the scenes, because you do not read the story, as you might expect, left to right, from top to bottom, in four lines, but from left to right in vertical pairs, and from bottom to top.

If you read them in pairs, you will have no difficulty in fitting the Crucifixion into the design (and one supposes that the need to make the Crucifixion large and central, with the three crosses leading your eye up to the Ascension above, must have done a great deal to determine the overall layout).

This first scene is set on Palm Sunday, the day which was to see the fulfilment of a prophecy made by Zechariah, in which he apostrophised Jerusalem with the words: ‘Your King is coming, humble, mounted on an ass, and on a colt, the foal of an ass’.

The story is told (with minor variations) in all four gospels; and it is tempting simply to quote the words of the Biblical text which the artist was asked to illustrate. Yet to do so would be slightly misleading, because Duccio is not so much interpreting the text anew, as reinterpreting the traditional way of painting this scene—the traditional iconography—which had become established in the eastern Church centuries earlier, and had then been exported to the ‘Latin West’.

To demonstrate just how closely regulated the elements in such a well-known scene had been, and were to remain, here is a fresco from south Italy painted two hundred years earlier (in principle, it could have been five hundred years earlier).

Look at it attentively before reading the instructions laid down for a Byzantine icon painter in the so-called Painter’s Manual by Dionysius of Fourma, written many centuries later.

You will see how the later ‘description’ or ‘prescription’ fits both pictures perfectly.

The Bearing of Palms

‘A fortified town; Christ, blessing, is seated on a donkey, with the apostles behind. There is a tree in which are children, who cut down branches with hatchets and spread them on the ground. Another child climbs up the tree and looks down on Christ. Below, are other children by the donkey, some holding branches, others spreading out their garments. Outside the gates of the town, Jews themselves are holding branches; others look towards Christ from the walls and windows of the town.’

Of course, I am not claiming there are no differences at all—indeed, the main point of the comparison is to make you aware of Duccio’s innovations. But do notice that Duccio’s architecture, although far from being a mere ‘pictogram’, is still not ‘scaled’ to accommodate the human actors; and you will find that all through the cycle, he continues to treat groups of overlapping figures just as in the eleventh-century fresco, that is, as though they were rugby forwards binding down before entering the scrum, or simply moving as one block, with no sense of space at all within the group.

With that said, we may enjoy some of the differences.

Duccio’s exploitation of the vertical format (achieved by the uniting of the panels) suggests the side of a hill town: two horizontal accents are given by the low stone of the terraced walls, and by the brick of the city walls. Nevertheless, the picture has a splendid feeling of ‘ascent’ or (‘Ascension’), as your eye travels up that red cobbled road, swinging left while still climbing into the city gate, and rising up to the great hexagonal Baptistry, the splendidly anachronistic symbol of the new faith to which the journey will lead.

As I said, the architecture still is not to scale, and the perspective can go radically wrong, but Duccio shows that he was well aware of the new techniques for creating pictorial space through the convincing foreshortening of architecture. Indeed, considered in itself, the foreshortening of the Baptistry or Temple, seen from below, strikes me as extremely convincing, as well as deeply satisfying.

Or again, think about the greater degree of human involvement in Duccio, evident in the clear differentiation between individuals. For example Peter, Matthew, John and James are quite distinct in the front row of the ‘apostolic scrum’; the children and the young men are very lively, and they give way to the more prominent figures of the Pharisees, who tug at their beards and pucker their brows to express resentment.

Or look at the interaction in the group near the stone wall, with the boys reaching up to get more branches from the youth in the tree.

And notice the little stroke of genius that occurred to Duccio in mid-composition: infra-red photographs show that he had first painted a woman spectator above Christ, but then painted her out with a dead thorn bush, in order to allude to the Crown of Thorns, and the coming tragedy.

If we compare Duccio’s scene with this panel by Guido da Siena, dated about 1280, which is very similar in scale, we can see how much Duccio has innovated while still fulfilling the Byzantine specifications.

Guido’s palm trees are almost as big as the ‘pictogrammic’ city; there is no allusion to the coming suffering and triumph; and the human figures are vivid but naive.

Duccio now moves straight to the human drama of Christ’s betrayal, arrest, appearance in courts of law, and execution. (Thus the next scene shows the Washing of the Feet on the following Thursday.) This part of the story is told in almost unprecedented detail; for there are nineteen scenes which take us three-quarters of the way through the cycle.

The action takes place indoors in a green-panelled room, this being the upper room of the inn chosen by Jesus to celebrate the Passover; and we ought to look at the interior as an interior for a moment, dwelling on the perspective (impossible only 20 years earlier) in the representation of the side-walls, the doors, and the soffits in the ceiling, all creating the effect of a shallow stage set—with the picture-frame acting as the ‘proscenium arch’. Notice too how the open door hints at further space beyond, and how the towel is deliberately draped (a favourite device in those years) to insist on its ‘three-dimensionality’. The depth achieved is very shallow—the set is too small for the actors, rather like in an amateur production in a village hall—but there is real space.

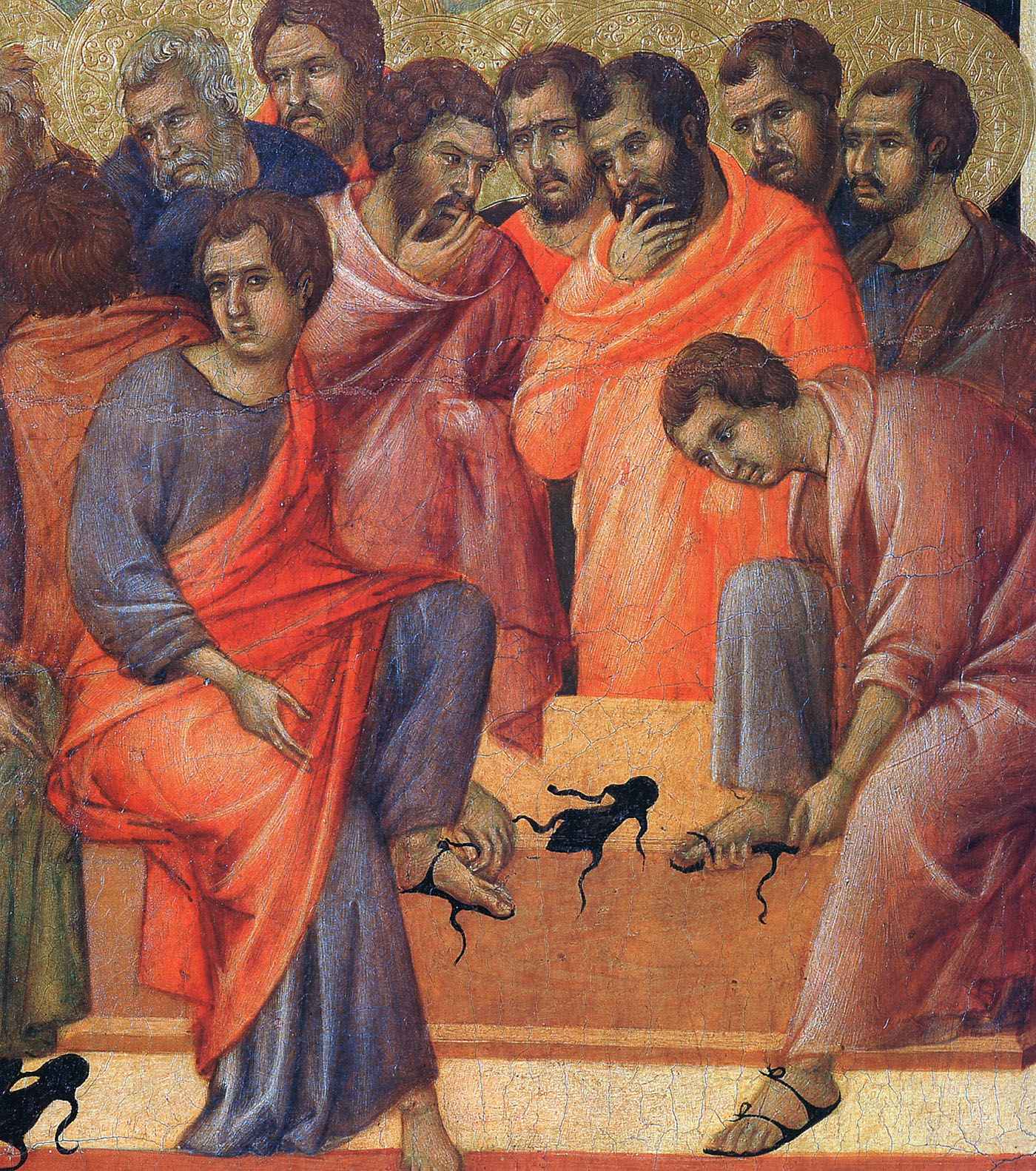

Duccio keeps his eye fairly closely on the text of St John’s Gospel, Chapter 13, where it is reported that Jesus is filled with foreknowledge of the End: ‘Jesus rose, laid aside his garments, girded himself with a towel, poured water into a basin, and began to wash the disciples’ feet. But when he came to Simon Peter, Peter said: “Lord, you shall not wash my feet”.’ What we see, as laid down in the iconographic tradition, is the moment of Peter’s protest (he has lifted his hand), which is coupled with Christ’s subsequent reproof: ‘If I do not wash you, you have no part in me’, and, pregnantly: ‘You are not all clean’.

The remaining apostles form a scrum, or perhaps a loose ‘scrimmage’, but their reactions are well diversified.

Andrew and Matthew share the amazement of their fellow greybeard; Bartholomew and Simon, the middle-aged pair, ponder on the allusion to ‘uncleanness’. Thomas, the doubter, is tying his sandals back on, while the other younger man, John, pauses to meditate on Jesus’s words as he unstraps his sandal.

The group is also unified by a clear line of ascent, which is reinforced by the deliberate representation of the discarded sandals, which are shown as ‘beetles’ (symbols therefore of ‘uncleanness’ or of ‘treachery’), and as though they were climbing up and out of this scene into the one on its right, which will show Judas selling his master for thirty pieces of silver.

The next scene, immediately below, takes place in the same green room; and by the way, this concern to underline the ‘unity of place’ is another new feature of the early 1300s.

It shows the Last Supper, a scene for which the iconographic tradition laid down that there should be: ‘A room with a table in it, with loaves and plates of food, and a jug of wine and a cup’.

You can see that Duccio relishes the opportunity for some still-life painting, tilting the tabletop, in the now rather old-fashioned way, to display the pattern of the cloth, the Paschal Lamb on its dish—seen from above—and a fairly convincingly foreshortened jug.

The Byzantine specification goes on to require that Jesus should ‘sit at table with his apostles, with John, on his left, lying in his bosom, and Judas, on his right, reaching towards a plate and looking at Christ’.

Duccio—thanks to the new control of space—can put Judas on our side of the table, but he still keeps with tradition in preferring the account given in the Gospel of St John. Whereas St Matthew dwells on the blessing of the bread and wine (the proto-Eucharist), John reports Christ’s words, ‘Truly, I say to you, one of you will betray me’; and John goes on to tell how Jesus identified the traitor by passing to Judas ‘a morsel of bread dipped in wine’.

Notice how naturally Judas is separated from his neighbour, Andrew, to the right; and how their balancing poses and hand gestures establish the base of a triangle for the main action—a triangle which goes not only upwards to its apex in Christ, but back across the table into space. Once again, this exploration of depth for the purposes of narrative is something quite new in these years.

The next scene lies immediately to the right in the bottom row, and is relatively rare in a Passion Cycle.

Set in the same green room, it illustrates the long discourse in the Gospel of John (Chapters 14 to 17), during which Jesus tells Peter that ‘the cock will not crow till you have denied me three times’.

There are some lovely psychological studies in the ‘scrum’ who are listening to their ‘coach’, all intent, but with well diversified gestures: for example, Philip pushes his fist up to his throat, while Andrew plucks his beard.

Meanwhile Jesus sits by the open door through which he will go to Gethsemane, his cloak already pulled round him against the cold, as he urges his disciples to ‘love one another even as I have loved you’.

The scene changes to a courtyard with a no less striking change in colour, from green to pinks and greys. We are in front of a ‘loggia’, which does not enclose the actors in any way, but is of considerable interest spatially. It preserves the convention (one which would last until the 1430s) that allows you to see the front elevation of a building ‘flat on’, and yet simultaneously see the side wall opened out. Yet the panel is very ‘advanced’ indeed in the convincing foreshortening of the vaulting, which is seen from below and from the left.

Let us come to the action. Judas stands (in his green and red costume) in front of a compact group, who are significantly without halos—a group dominated by the High Priests, Caiaphas, dressed in green, and Annas, dressed in red.

The group have ‘put their heads together’ and offered Judas thirty pieces of silver if he will lead soldiers to a quiet spot in order to arrest the troublemaker, and if he will identify Jesus among his companions. I am sorry not to include a close-up of the heads, showing their shifty and malevolent expressions, but I hope you can sense the tension in Judas’s back and in his hands as he receives his ‘reward’.

Passing to the broader central panel in the bottom row, we see another change in location, again reinforced by a dramatic change in colour: the Garden of Gethsemane is set under a gold sky, with white rocks, rising from left to right; and it is identified as a garden (as the Painter’s Manual prescribes) by the presence of trees—orange trees, as you can see in the foreground.

It is of course the same night, following the Last Supper.

Jesus has left the main body of the disciples to sleep; and we see them close packed, as always, wrapped in their cloaks, ‘dead to the world’, in spite of their uncomfortable positions.

Particularly striking are young Philip in the foreground, abandoned, with his head thrown back, and old Matthew, hunched forward.

Jesus asked three of the disciples—the ones who had witnessed his Transfiguration, Peter, John and James—to go with him ‘and to keep watch’, while he went to pray, in an agony of spirit, that ‘this cup might be taken from him’.

An angel appeared to ‘strengthen him’, but when Jesus returned he found the three fast asleep; and he had to rouse them (this is the moment represented in the centre of the panel), with the reproach: ‘Could you not watch with me this one hour?’

‘While he was still speaking, Judas came, and, with him, a crowd with swords and clubs’; and after Judas had identified him with a kiss, Jesus was seized.

As usual, the figures form an overlapping group; but here it is more than usually complex. In the sky above, we see the lances and torches (it is night time), which are specified in the Painter’s Manual, instead of the ‘clubs and swords’ in the text.

Below them, we see a dozen ‘Roman’ helmets, then the beards and head dresses that identify the priests and scribes.

On the left, we see Peter, who, with his usual impetuosity, slices off the right ear of the High Priest’s servant (notice the colour of his clothes, ochre over red). To the right, a soldier seizes and is about to strike Jesus (both these elements being required in the pictorial tradition), while the centre contrasts the open violence on the flanks of the scene with violence masquerading as love—in the kiss.

The two faces here are not as memorable as Giotto’s in Padua, but there is a clear difference in intention. Giotto allows the eyes to meet in order to dwell on the reproach; Duccio focuses his attention on Jesus as a peacemaker: the gesture of his hand is the gesture by which he healed the servant’s ear.

On the right of Duccio’s scene, there is a second group for which he must have looked to Byzantine models, since it is apparently the first time in Western art that we see an illustration of the laconic verse: ‘Then they all forsook him and fled’.

‘Flee’ they certainly do, whatever their age—with old Andrew in the rear, then middle aged Simon, young Philip, and even the ‘best-loved disciple’, John:

Moving now to the pair that lie to the right of the central panels, we come to another bold innovation in the layout, which once again emphasises the need to link the registers vertically and which offers the possibility that the two scenes are taking place simultaneously, because this pair is not divided by the frame.

The story is told in John 18:12 and Matthew 26:57, where we read: ‘They seized Jesus and led him to Annas, the father-in-law of Caiaphas. But Peter followed at a distance as far as the courtyard of the High Priest and going inside he sat with the guards, who had made a charcoal fire, because it was cold; and Peter stood and warmed himself’.

In the room above, we are shown Jesus before Annas, standing patiently, his hands bound, while the High Priest’s servant (dressed, you remember, in red and ochre) joins the others in accusations of blasphemy. In the courtyard, below, with its external staircase (conveniently tilted for us), we see Peter seated among the guards.

We won’t delay on the upper group—because the pictorial interest lies in the lower scene, where the maid points an accusing finger at Peter, saying: ‘You also were with Jesus the Galilean’.

Here Peter is making the first of the three denials predicted by Christ, as he holds up his hand, saying: ‘I don’t know what you mean’.

It is a charming excuse for some local detail: a realistic small fire, an amazingly unrealistic view of the stool, the guards leaning forward to warm their hands, and Peter simultaneously lifting his hand in denial while trying to toast his bare feet at the fire.

The next scene in the lowest register also forms a pair with the one above it.

In this case the loggia, distinguished in colour, represents the house of Caiaphas.

The accusations against Jesus continue, and we have reached the point where Jesus breaks silence at last to admit that he does claim to be ‘the Christ’.

At this, Caiaphas is said to have ‘torn his mantle’, exclaiming: ‘You have heard the blasphemy’. The remark leads all present to agree that Jesus should be condemned to death.

To the left, outside the loggia, we see Peter denying all knowledge of the ‘Galilean’ for a second time.

Punishment begins immediately in the paired panel above.

For the first time, violent hands are laid on Jesus, because ‘the men who were holding Jesus mocked him and beat him; they also blindfolded him, saying: “Prophesy, who is it that struck you?”’ (Luke 22:63).

It is an ugly moment, certainly, but not so painful as the scene on the left, again outside the loggia entrance.

Here Peter is denying all knowledge of the ‘Galilean’ for the third time, at which moment the cock crew, and Peter ‘remembered the word of the Lord…and went out…and wept bitterly’.

We have now ‘upped and downed’ our way through the whole of the lower register: Entry—Washing of Feet—Last Supper—Discourse to Disciples—Judas’s Pact—Betrayal—Gethsemane—House of Annas (and First Denial)—House of Caiaphas (Second and Third Denials)—Pilate’s Palace.

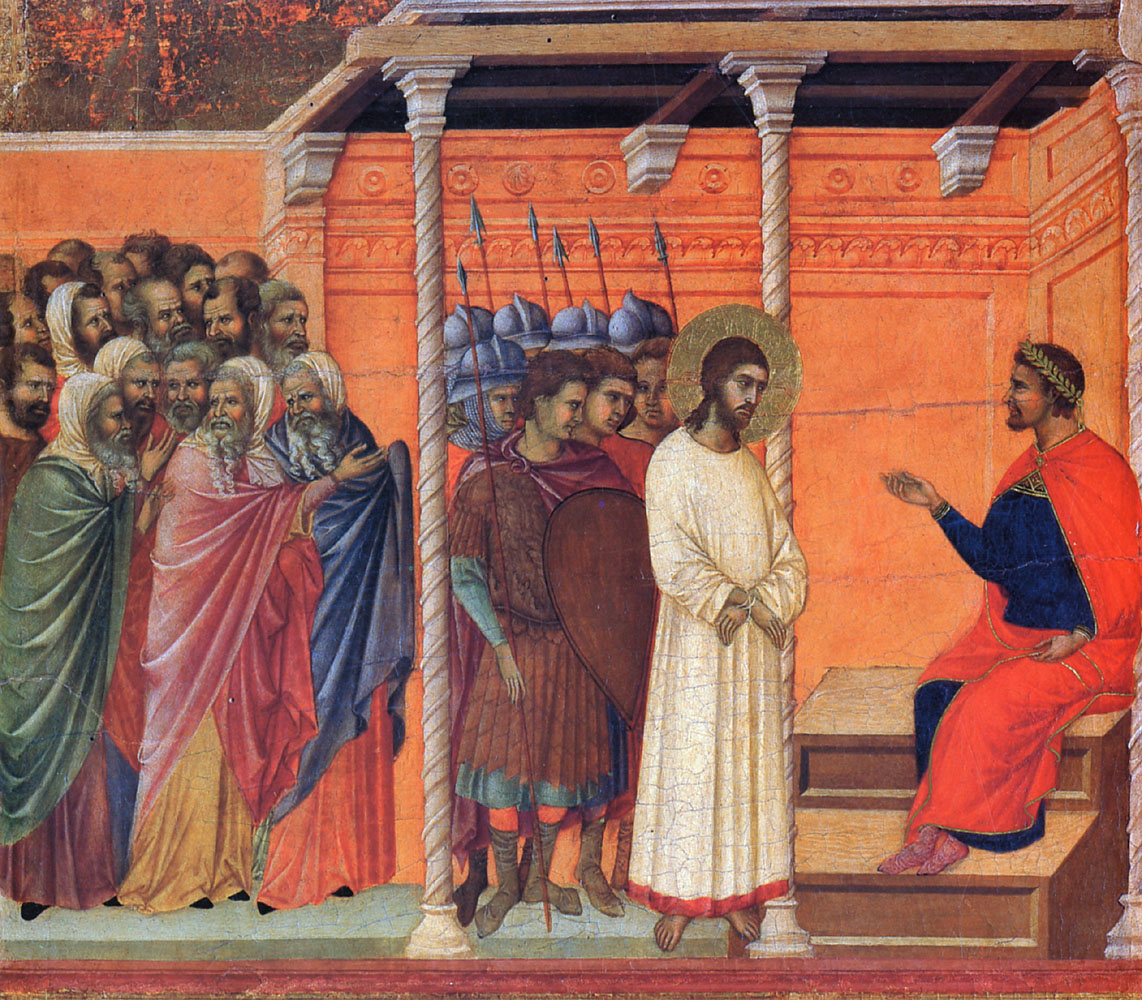

The next section will be dominated once again by indoor scenes, specifically courtroom scenes, including four more set in Pilate’s red and pink palace.

The first of these, however, is actually located in the palace of King Herod, the Tetrarch, to whom Pilate had sent Jesus on learning that he was a Galilean, and therefore subject to the Jewish ruler.

Notice the crown on Herod’s head and the attendant who is proffering a white robe. This is the ‘gorgeous apparel’ which the soldiers will contemptuously put on Jesus before he is taken back to Pilate.

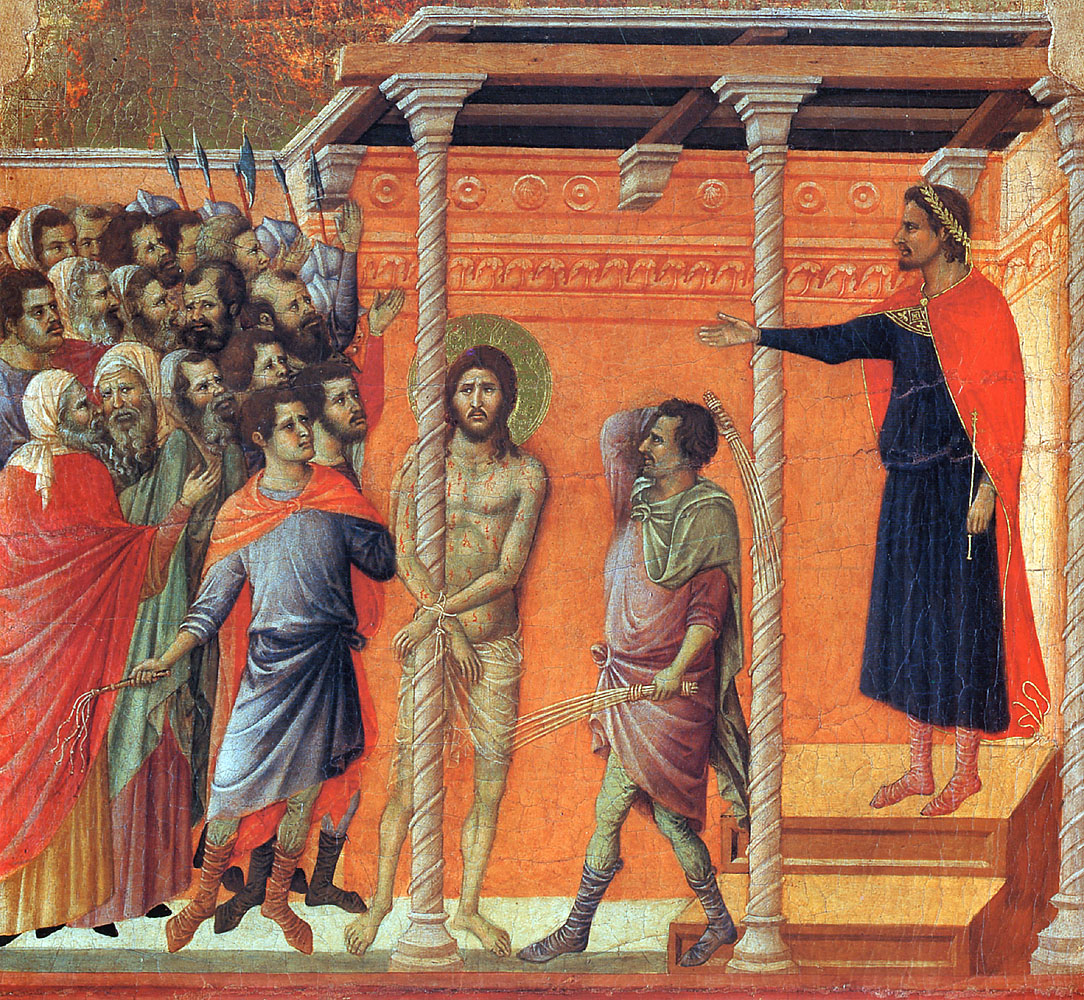

Pilate gives in to the demands of the crowd, and so we come to the grizzly preliminaries to the judicial execution.

In the upper panel, Pilate stands and gives orders that the prisoner be stripped, tied to a column and flogged (the word ‘flagellation’ does not convey what the cat-o’-nine-tails is doing).

Below comes the ritual humiliation and derision. Pilate looks on while his soldiers clothe the condemned man in a ‘purple cloak’—Duccio makes it ‘bright’, which is the normal meaning of the Latin word ‘purpureus’. They plait a crown of thorns and place it on his head, put a reed in his right hand, and kneel before him in mock homage, saying: ‘Hail, King of the Jews’, while spitting on him, and striking him on the head with the reed.

The last scene to be set in Pilate’s praetorium is in the third row, next to the central panel.

Here, Pilate ‘takes water and washes his hands before the crowd, saying “I am innocent of this man’s blood”’, while the soldiers strip Jesus of his robe, put his own clothes on him (indeed, he is back in his red robe) and lead him away to be crucified.

All the remaining scenes will be out of doors, under a golden sky.

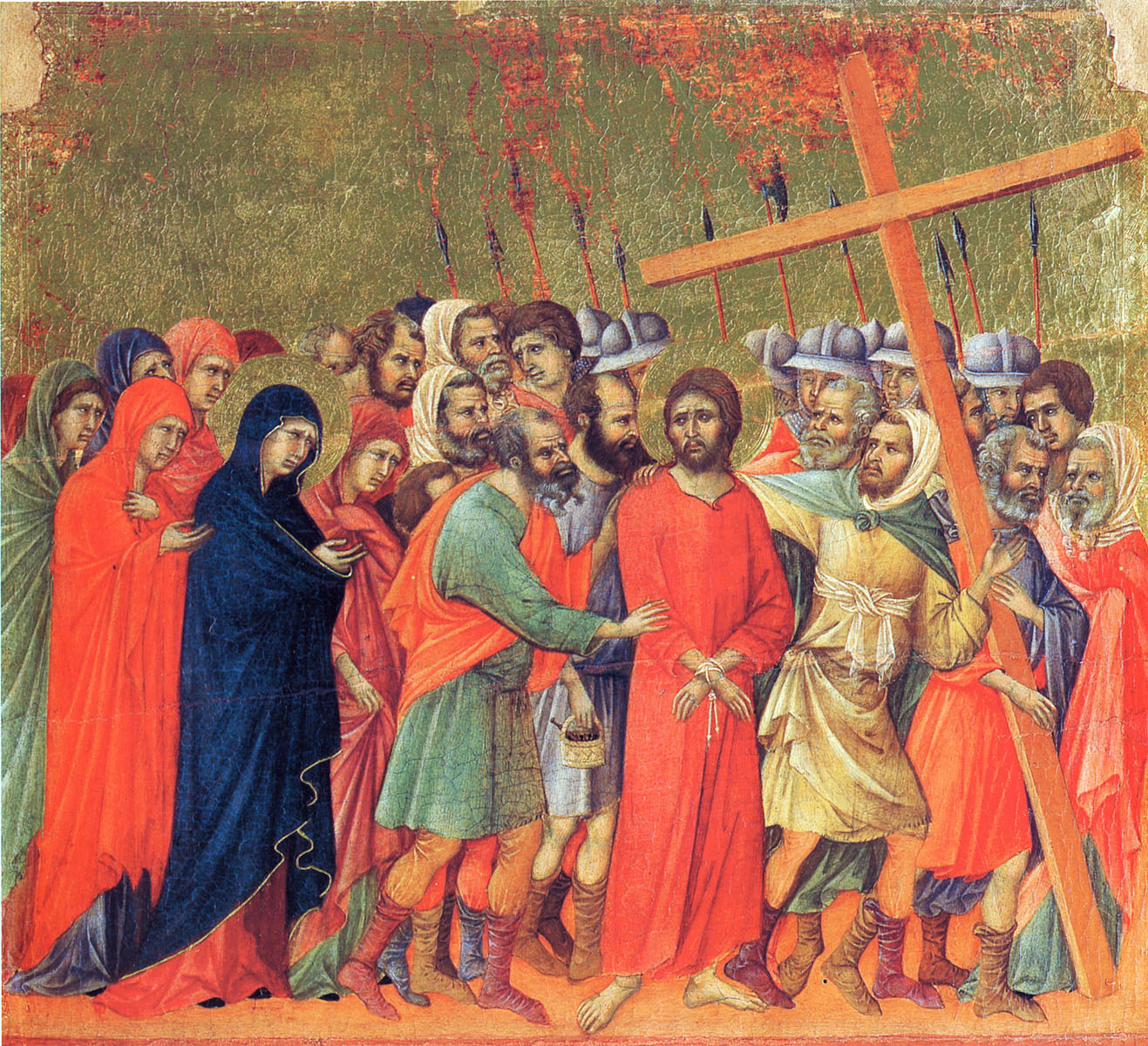

The first of these is the Way to Calvary.

‘As they were marching out, they came upon a man of Cyrene, Simon by name, and they compelled him to carry the Cross’.

It is a requirement of the Painter’s Manual that Simon be grey-haired, with a short beard, and wearing a short garment.

Duccio’s figures form a single crowd, with no clear caesurae and no space to either side, but notice how the angle at which Simon is carrying the cross contrasts with the absolute verticality of the slim figure of Jesus, and notice how colour is used to contrast the long red robe worn by Jesus, the ordinary, contemporary dress of the three executioners who flank him (one of whom is carrying a basket of nails), the traditional dark-blue robe of the Virgin Mary and, behind her, Mary Magdalene in scarlet.

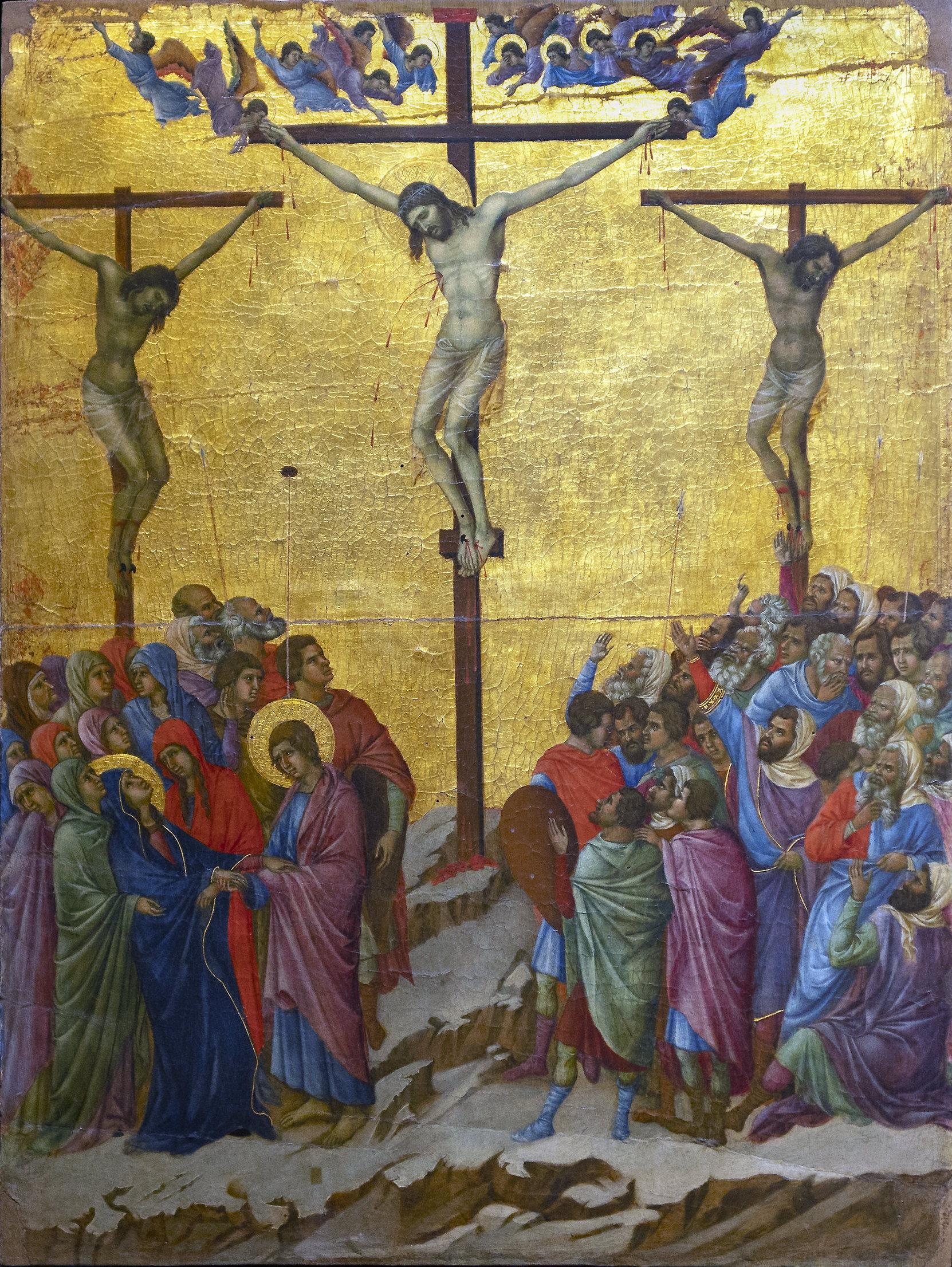

The crowds are placed well to each side in order to reveal the whole cross and the redeeming blood flowing from the side of the Man of Sorrows, who is considerably enlarged with respect to the other figures.

The sky is filled with grieving angels.

(You might well want to scroll back to the introductory pages at this point in order to compare Duccio’s almost lyrical representation of the slender body of the Redeemer with the starker, more stylised images painted by Coppo and Cimabue.)

We come now to the final six scenes, which begin with the removal of Christ from the cross.

Duccio is following the Byzantine tradition fairly closely in the first panel; and it is instructive to quote from the Manual again:

The Deposition

The Cross erected; a ladder is leaning against the Cross and Joseph climbs up it. He holds the body of Christ round the waist and lowers it down. The Virgin standing below receives it in her arms and kisses the face. Behind the Virgin are the women carrying spices and Mary Magdalene who takes the hand of Christ and kisses it. Nicodemus, half-kneeling, pulls out the nails in Christ’s feet with pincers.

Every detail in the Manual is there; but Duccio still shows a measure of independence from tradition by giving John a very active role.

In the next scene, all the figures are bowed in grief as the three men—John, Joseph and Nicodemus—lower Christ’s body into his tomb, while the Virgin (I quote again from the Manual): ‘kneels over him, kissing his face, and Mary Magdalene throws up her arms high to either side’ in a ritual gesture of lament.

Then, suddenly, the mood changes, just as it does every year from Good Friday to Easter Sunday.

The same sepulchre appears in front of the same stylised mountain, but the cover of the tomb is lifted, and an angel, ‘in raiment white as snow’, tells the Three Marys that Jesus has risen from the dead.

We are down to just four actors here, and it is one of the least demanding compositions in the whole cycle. But it is masterly in the women’s very restrained gestures of alarm and in the studied nonchalance with which the Angel maintains his balance on the sloping cover, while pointing vigorously across his body with his free arm.

Contemporaneously, in the lower panel, here, we see the Risen Christ. His red and blue robes are striated with gold, and he carries a cross and a banner with a cross.

He has ‘laid low’ the Gate of Hell, and ‘trodden down Beëlzebub’. (The sprawling devil has a human head, a furry body, a short, black wing and a lion’s paw.)

He reaches out his hand to deliver Abraham, Sarah, David, and other prominent prophets and patriarchs—it is the moment of the Harrowing of Hell.

And so we come to the final scenes in our story, showing the first appearances of the Risen Christ. (His six later appearances were represented in a row of separate panels, now dispersed, placed above our unified Passion Cycle, as you saw in the photomontage.)

Dressed in the same robes of glory, carrying the same banner and cross, in a similarly rocky landscape (the rocks climbing powerfully to the right), Jesus reveals himself to Mary Magdalene, but begs her ‘not to touch him’, ‘noli me tangere ’.

In the very last episode, two of the disciples—who have all been absent from the story (with the exception of Peter), since they ran away at the time of the Betrayal—are walking to the village of Emmaus, about twelve miles from Jerusalem, ‘talking of the great events’.

Jesus catches up with them, and walks with them, but they fail to recognise him—not surprisingly, since he is not in his familiar blue and red, but disguised as a medieval pilgrim, with a staff in his hand, his sunhat on his back, and wearing a hair shirt.

It is the simplest composition in the whole cycle, naive in its almost pictogrammatic buildings and the cobbled road, lighthearted in its colour and mood. The last of the thirty-six scenes is therefore a very good place to bring the lecture to an end. Despite his countless innovations, Duccio, in 1311, has remained faithful to the spirit of his late thirteenth-century predecessors.