Master of the Osservanza: The Life of St Anthony Abbot

In this lecture, we move forward more than a hundred years, to look at two cycles of paintings from the decade between 1435 and 1445. Neither can offer a life-changing experience (as, in their different ways, Duccio, Simone and Ambrogio were able to change our perceptions of religion, art and politics); but the unfamiliar paintings have great charm and extend our knowledge of the social and cultural context of Sienese art.

The Black Death hit the city of Siena in 1349, killing between three fifths and two thirds of the inhabitants, so that only about 15,000 survived.

It was Discord and War that were to rule in Siena after the plague, rather than Justice, Concord, and Peace.

The rich merchant families that had dominated the republic under the constitution of the ‘Nine Governors’ were overthrown in 1355 by a group from within the ‘popolo’, who installed twelve magistrates, drawn from the minor guilds. In 1368 there was a coup d’état by the nobles; but there was a quick counter-revolution which was followed by a period of fourteen years during which government was dominated by artisans belonging to the lower classes.

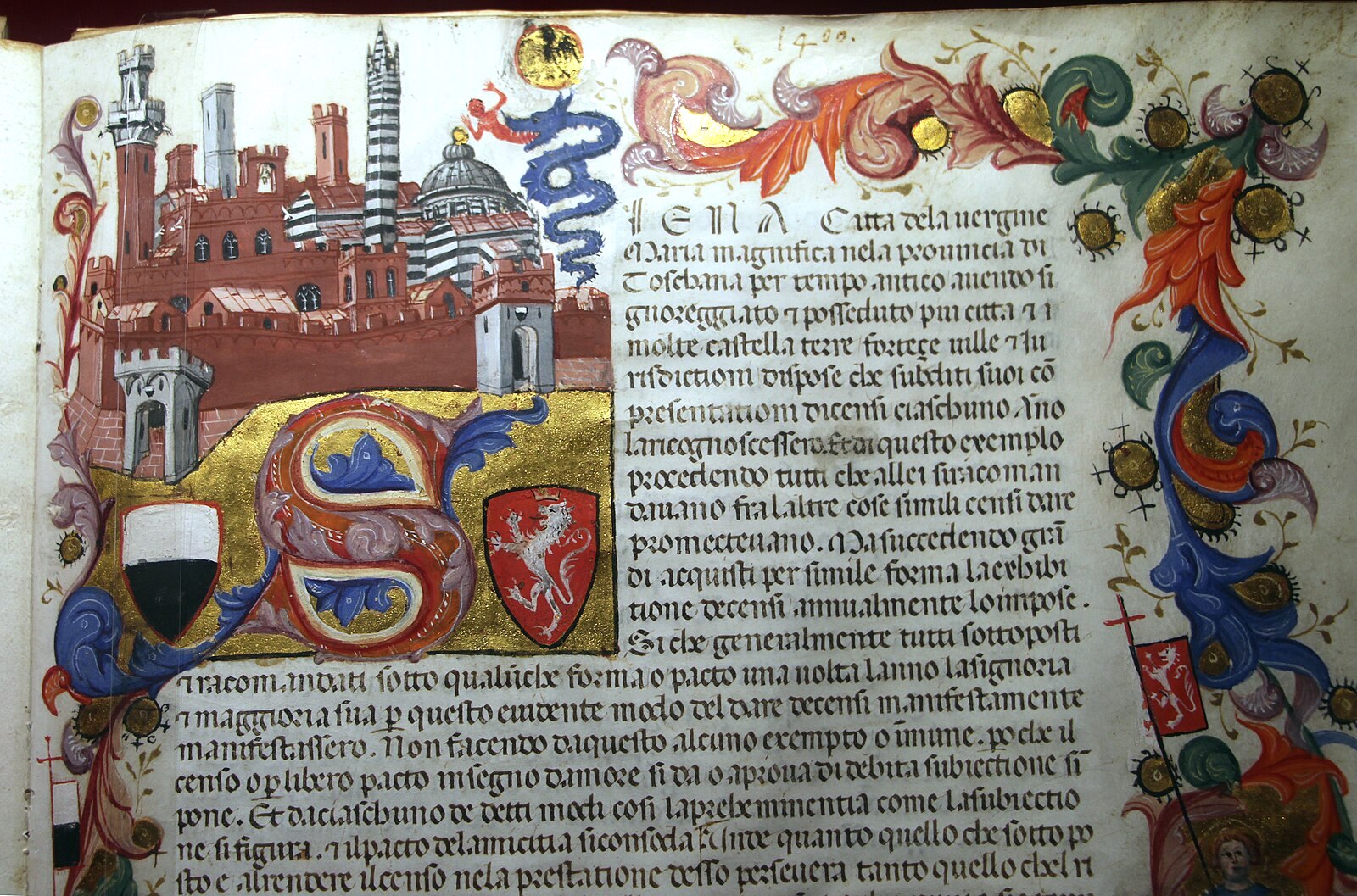

After this, in 1390, the Sienese accepted the lordship of the Duke of Milan for fourteen years. (Hence the little miniature on the opening page, dating from the year 1400, displays not only the towers and the emblems of the Commune and the ‘People’ of Siena, but the Viper of the Visconti family in Milan.)

After the death of Gian Galeazzo Visconti in 1404 (a watershed in Italian politics), Siena became independent again, and there were prolonged internal battles between five groupings of families—each called a Monte, literally, a ‘mountain’—which took their names from the various constitutions that had been tried and overthrown during the fourteenth century, viz.: The Nobles, The People, The Nine, The Twelve, and The Reformers.

One could not participate in Sienese political life in the fifteenth century unless one were a member of one of the 350 families who made up these five Monti and who formed and dissolved coalitions as quickly as the parties in the Italian Chamber of Deputies in the second half of the twentieth century.

Having called your attention to a considerable ‘decline and fall’ after the prosperous and stable years of the government under the Nine, I must remind you of what remained unchanged.

The Sienese Republic survived as such right down until 1557. It kept control of its immediate hinterland or ‘contado’ (as you can see in the political map of Italy in about 1480). And most of the buildings of medieval Siena remained as they had been in about 1330.

I should also stress the continuing importance of Catholic Christianity in the daily life of the city.

Religion penetrated all levels of society in many different forms, from state ceremonial at one extreme to ‘born again’ evangelism at the other, and from mysticism to practical acts of charity.

The Commune, as a whole, periodically re-dedicated itself to the Virgin, as you can see in a panel painted ‘in the time of the Earthquakes’ in 1450.

There were thirty-six parish churches and several convents and nunneries, as well as numerous confraternities of laymen. The guilds all had their own patron saint and religious observances.

The Dominicans and Franciscans had built two colossal churches, as had the Carmelites; and the Siena gave birth to two saints in this period, who—unlike Ansano or Crescenzio in Duccio’s Maestà—have acquired enduring, international fame.

The second was St Bernardino, a Franciscan, who was born in the year of Catherine’s death and died in 1444.

He was a charismatic preacher who tried to persuade his fellow countrymen to bury their differences and wear a badge with the name of Jesus (IHS) rather than the sign of their individual Monte. (You see him in action in the Campo, with the Palazzo Pubblico behind.)

Many of his vivid sermons survive, and offer a rich and detailed picture of life in Siena in his lifetime.

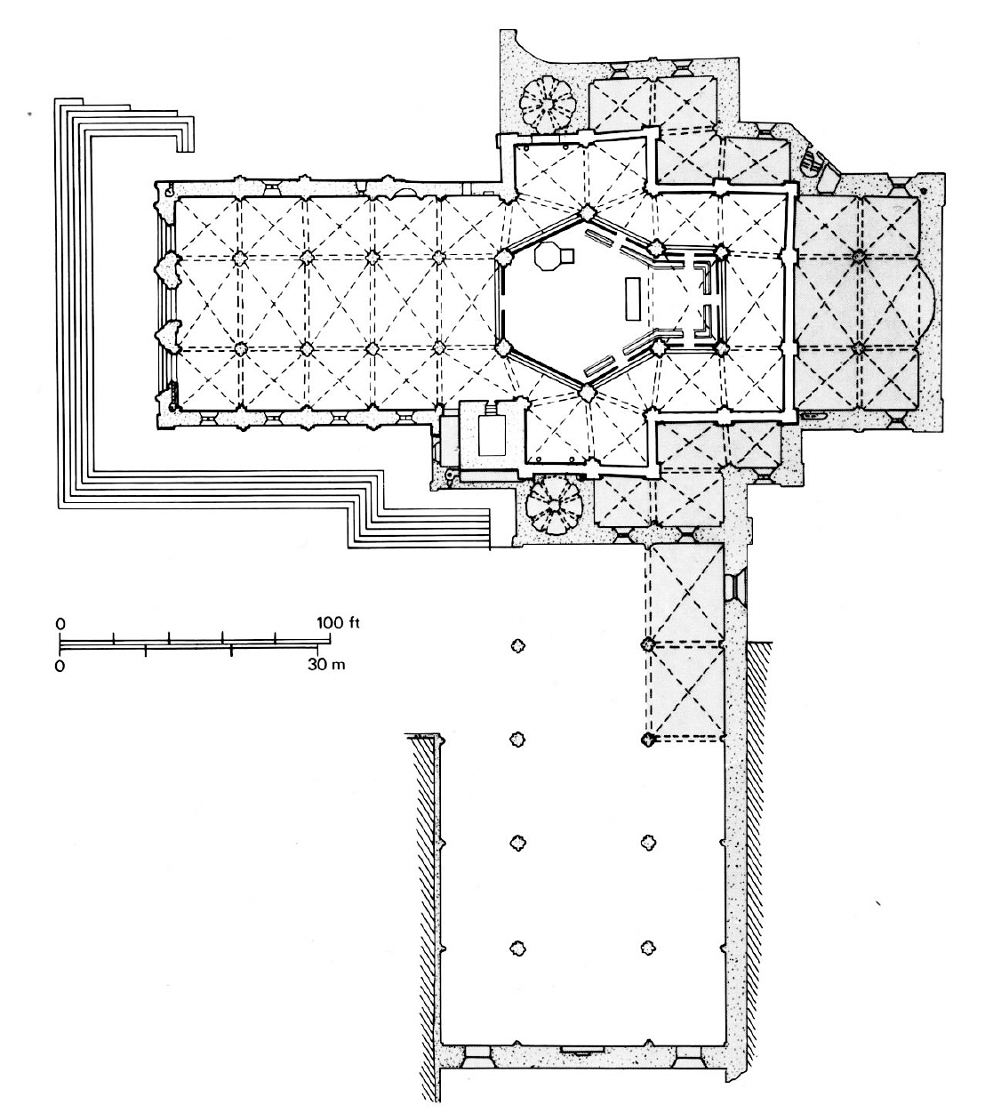

In the fifteenth century, however, there was nothing to compare with the amazingly ambitious plan, conceived before the Black Death, of enlarging the Cathedral in such a way that the existing building would have become no more that the transept of the new.

The project was never completed, but the wall and arches that survive enclose one of the most beautiful spaces in the whole of Siena.

After this glance at the Cathedral, we can turn to another continuing success story—an institution which traced its origins back to the days when the Bishop of Siena was head of the Commune.

It had flourished under the rule of the Nine Governors; and enjoyed a new lease of life in the fifteenth century.

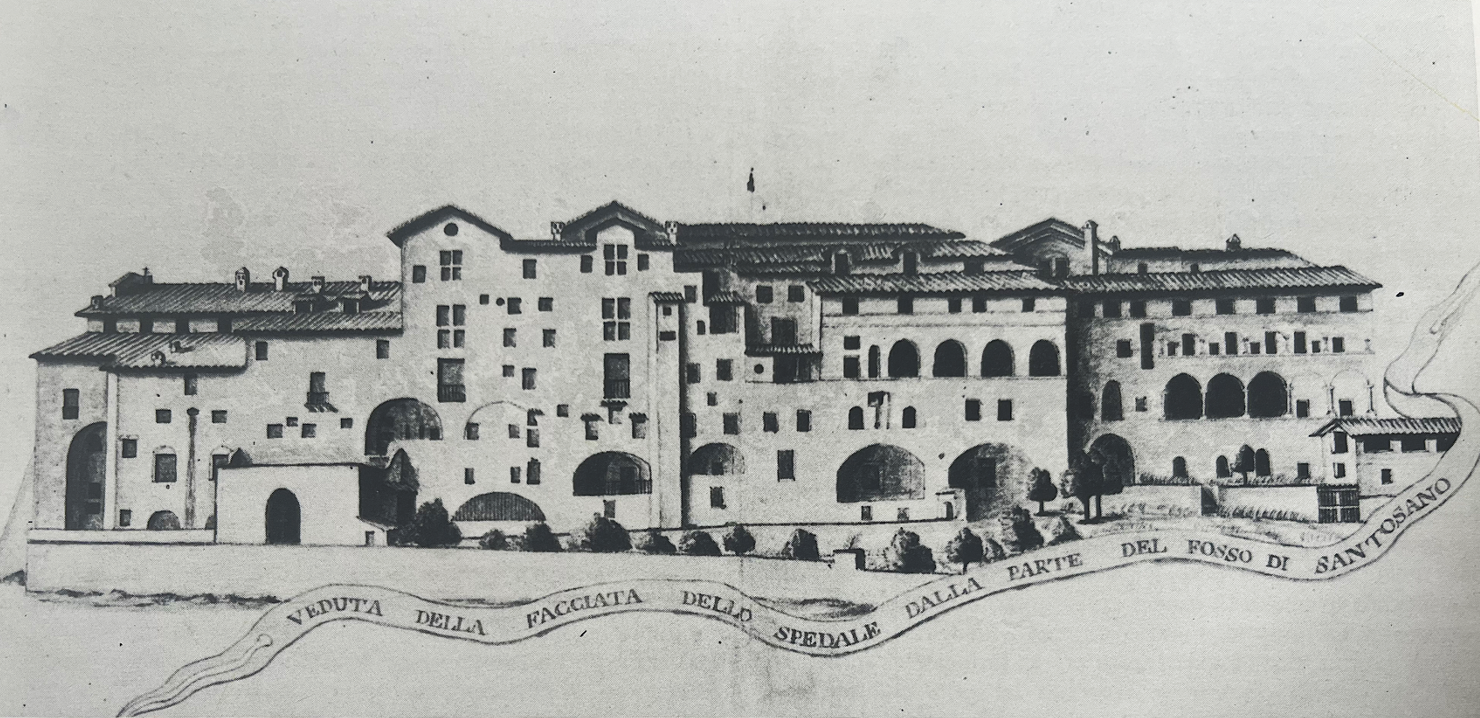

This is the Hospital: ‘lo Spedale di Santa Maria della Scala’.

It stands right in front of the Cathedral and has a deceptively modest façade.

This extraordinary institution, the envy of all Europe in the fifteenth century, was administered by the cathedral clergy. But after a power struggle in the late twelfth century, lay members had acquired control of the huge assets (it owned vast lands in the contado), through which it provided a free Health Service and a Social Security Service, far in advance of anything in Britain until the coming of the NHS.

It acquired its definitive statutes at the beginning of the fourteenth century, under the Nine; and at the beginning of the fifteenth century, the Commune intervened more actively, asserting the right to appoint the Rector.

Two of these Rectors proved to be men of outstanding ability; and it was the second of them, Giovanni Buzzichelli, who decided in the late 1430s to redecorate what is called the ‘Pellegrinaio’.

This is an imposing room on the side facing the Cathedral; and as its name suggests, it served to accommodate the numerous pilgrims (‘pellegrini’) who travelled to and from Rome along the ancient Via Francígena (which was traced out on a map in the first lecture of this series).

The room also did duty as a hospital ward, but its new decorations were clearly intended to impress the outsiders, and to make them aware of the history and the activities of the Hospital where they found themselves.

I hope they will impress you.

As was usual, the bays were reserved for the descriptive and narrative frescos, which, again as was usual, start about seven feet above the ground.

Those on the left wall deal with the early history of the Hospital, which was reputedly founded by gentleman called Sorore back in the third century AD.

The figures ranged across the foreground of the first fresco distract our attention from a prophetic dream (at the top of the central arch) granted to the mother of the legendary founder, but the distraction is of no importance.

We do not need to know anything about the story here, since all the interest lies in the representation of the architecture, which should hit you like a sledgehammer between the eyes, both because of the style of the building represented and because of the system of perspective.

Painted in the 1440s, it could scarcely be more different from Ambrogio Lorenzetti’s empiricism of a hundred years earlier.

The artist here is always known by his sobriquet, Vecchietta. He was born c. 1412 and was apprenticed to one of the most conservative Sienese painters of his age, a man twenty years his senior, Sassetta. (We shall see some of Sassetta’s works later.)

But everything here shouts Florence.

The perspective employs the simple but comprehensive geometry codified in the ‘legitimate construction’ of Alberti’s Della Pittura (1436). And the many classicising details in the painted church show familiarity with the buildings of Brunelleschi. (The design of the nave and aisles is even said to reflect his plan for the church of Santo Spirito in Florence.)

The second fresco is dated to 1441 and is by the principal artist in the room, Domenico di Bartolo (c. 1400–1445).

He had certainly been in Florence and the North in the 1430s and in this street scene he too shows an astonishing command of the new, single-vanishing-point perspective.

Once again, I shall virtually ignore the story in the foreground, which deals with the enlargement of the hospital in the eighth century.

Enough to say that the curly-headed young man on the white horse (which is apparently about to trample on the workman laying the paving slabs) is none other than the Bishop of Siena.

I would ask you to dwell for a moment on the fantastic building in the centre: a hexagonal baptistry in five distinct tiers topped by a cupola, which is almost a parody of the cathedral in Florence (then nearing completion) in its polychrome fusion of the Gothic and the Classical. Its crazy collection of details make it almost as exciting as a Tower of Babel.

From the point of view of social history, however, we ought to look at the right hand side, where the labourers are checking the stones for size and sorting through the bricks brought by the mule, before having them carried up the scaffolding to the bricklayers working at the top, either in a basket, or in buckets on a winch.

The fresco that follows is by Priamo della Quercia (c. 1400–67), another Sienese artist of the same generation, best known for his miniatures in a codex of the Divine Comedy.

The rounded arches and the details of the monumental architectural interior recall that of the first scene, although with different proportions.

In the foreground we see a Rector of the hospital being invested in his robes by a prominent local saint from the early fourteenth century known as Beato Agostino Novello (we shall return to him later).

The remaining scene of the left wall was placed out of chronological sequence to give it greater prominence.

The figure enthroned on the left is Pope Celestine III, who in the 1190s granted autonomy to the Hospital, making it independent of the Cathedral.

The artist is Domenico di Bartolo again, and again he is using the new Florentine perspectival system to create effects which are weirdly provincial.

We turn to now to the opposite wall to look at the scenes of contemporary life in the Hospital. These were all painted by Domenico di Bartolo and were executed two to three years earlier than those we have looked at so far.

The first fresco documents the activities that we would expect to find in a ‘Hospital’ today—the care of the sick.

The huge ward has a high ceiling, similar to those still found in the real wards of the same building.

Quilted canvas screens, and a sort of wire cage, separate the beds of the unseen ‘in-patients’ at the rear from the Reception Area and the A & E clinic in the foreground.

In the foreground, we are witnessing a visit of inspection from a group of soberly clad officials, accompanied by a nobleman in an amazingly tall hat (a mazzocchio), which is perhaps why there are two doctors in attendance, both in their best clothes.

A male nurse is bathing the feet of the man in the foreground who has been involved in an accident which has left his right thigh bleeding from an ugly wound; his ‘mules’ are on the red tiled floor.

To the right, a dog snarls at a cat, and agitated porters are bringing in another stretcher on their shoulders. A burly friar has pushed back the cloth from a free-standing basin (with its top tilted towards us in the old-fashioned way) and is about to administer the last rites to the unconscious man stretched on the bed behind him (by contrast, a remarkably modern piece of foreshortening).

The second scene records another important part of the activities of the Hospital—provision for the poor, and, specifically, the distribution of alms and whole loaves (as had been laid down in Pope Celestine’s statutes).

In the background, at the street door, an official is distributing rolls, while a healthy-looking mother supporting a lusty baby, walks towards us with a shopping-basket full of bread. Matrons escort the gift of a large basket of used clothes ‘for Oxfam’; while in the centre a young (and very ‘academic’) nude is being helped to draw on a handsome blue robe (although the solemnity of the scene suggests the reception of a novice into the hospital community).

The oriental splendour of the headgear and the coats worn by the nobleman and his page on the left are a reminder that Pope Eugenius IV had been in Siena for five months during the mid-1430s, at a time when there were intense diplomatic contacts with the Greek Orthodox Church.

We must not neglect the architectural setting—clearly a faithful representation of a very public space just inside the entrance of the hospital, allowing a glimpse of the façade of the Cathedral opposite.

In the narrow chapel between the balconies, notice the elaborately gilded Gothic altarpiece and glazed terracotta reliefs in the arch above (of a kind we associate with the Della Robbia brothers in Florence).

On now to the third and best known of the documentary scenes.

We are in the female quarters and the setting is at once more intimate and much grander.

Look at the polychrome tiles in the rich pattern on the floor or at the very expensive carpet on the right. And notice, too, the classicising columns, rounded arches (with two archetypal Late Gothic openings to the right), relief busts, and shell motifs which all reflect the art of Florence in this period.

The fresco represents two moments at the very beginning and end of the care of orphaned or abandoned children—which is surely the single most striking feature of the Hospital’s statutes and activities.

At one time they had more that 300 foundlings in their care, under what sounds like a humane and caring regime.

To the right we come to the happy conclusion.

One of the girls who has reached marriageable age is restored to the community outside by being given in marriage (with a generous dowry) to a respectable young man.

We see the moment when he places the ring on her finger, while prosperous matrons give the ceremony their blessing, and still unmarried girls look on eagerly from a balcony behind.

The final scene in the cycle shows the thrice-weekly Meal for the Poor—that is, food served ‘on the premises’ on Sundays, Wednesdays and Fridays, as opposed to the ‘take away’ you saw earlier.

The scene is easy to read and the fresco has been badly affected by damp, so I will do more than invite you to look down the prodigious length of the hall under its barrel-vaulted ceiling, opening onto a colonnade of similar length.

I hope I have not exaggerated the artistic merits of this cycle—but also hope to have said enough to make you want to go and pay homage to a noble, civic institution which put to shame many nation states in later centuries.

The cycle of frescos in the Ospedale, four legendary and four documentary, were painted between 1438 and 1444. In the second half of this lecture, I want to show you another eight paintings, this time forming a narrative cycle, that were painted in the same years –although they could hardly be more different in scale, medium and style.

They offer a happy blend of the forward-looking and the backward-looking. So, to help you distinguish the ingredients, I would like to fill in the missing years in the history of Sienese art since the 1330s, by singling out just two new names and showing you half a dozen masterpieces in the local style, so that you may pick up the trajectory that leads from the Sala della Pace to our altarpiece.

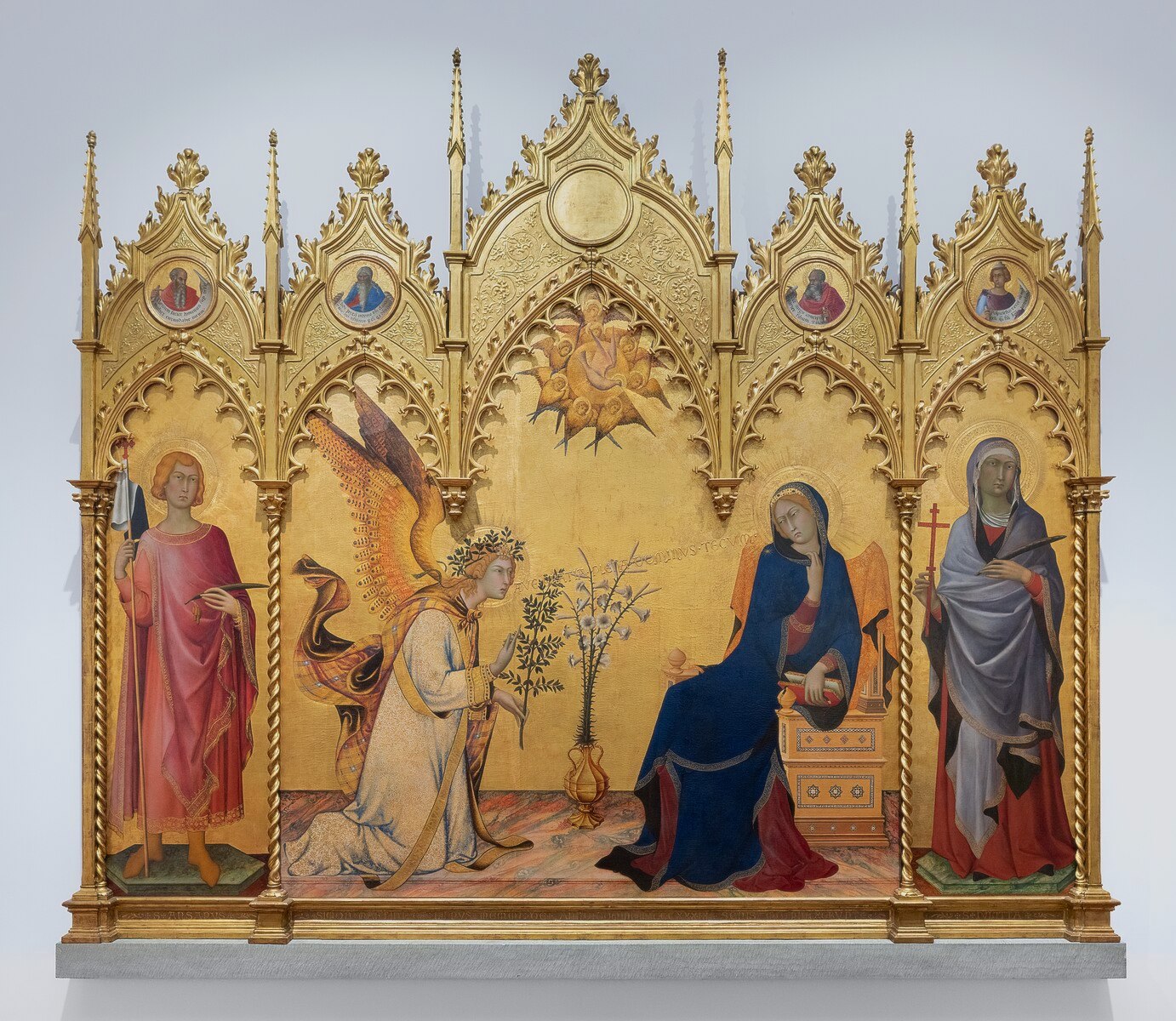

What you see here is Simone Martini’s famous Annunciation (now in the Uffizi in Florence), which was painted in 1333 and stood, universally admired and venerated, then as now, on the altarpiece in the chapel of St Ansano, in the left transept of the Cathedral of Siena.

It is a large devotional painting intended for the whole congregation, and measures about nine feet high to the top of the pinnacles.

Here you can enjoy another work by the same artist, but only about three feet high.

It was painted in the same decade but is in the more intimate style appropriate for a predella, (it was in fact painted for the side of an altarpiece in the Sienese church of St Augustine).

The panel represents a miracle by the local saint mentioned earlier, Beato Agostino Novello, who died in 1309.

The saint swoops down like Superman on seeing a little boy fall from a balcony when a plank gives way. He seizes the plank which is about to fall on top of the boy and crush him, keeping it suspended in mid-air until the boy has time to escape to safety. (The same boy is shown twice—first, falling, then restored to his family.)

Enjoy the colours, as you did in Duccio; note the steep diagonals of the empirical perspective; and notice, too, how the very simplified representation of the houses and overhanging balconies does nevertheless suggest a real street in fourteenth-century Siena, of the kind we saw in the first lecture of the series.

This next work is by Pietro Lorenzetti, the younger brother of Ambrogio. (The painting may date from the 1320s, but more probably from the 1340s, and certainly before 1348, when Pietro died during the Black Death.)

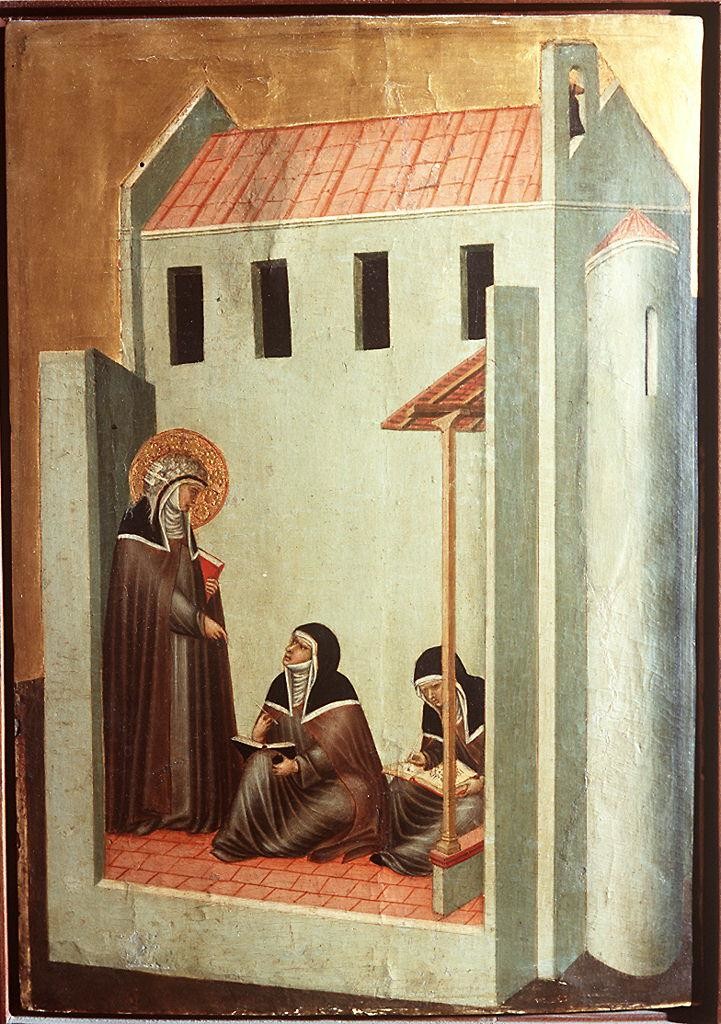

It is a reassemblage of most of the panels that made up his altarpiece for the convent of another recent local saint, a homely and practical Tuscan woman from the Vallombrosa near Florence who died in 1310.

She had a late vocation, separated from her husband, founded an order of nuns, called the Ladies of Faenza, and took the name ‘Humility’, ‘Umiltà’.

Let us look at two of the panels, each about 16 inches high.

The first panel shows the saint herself overseeing the transport of the stones for the building of her new convent.

Enjoy those smooth colours again, look at the sharply observed details of the bricklayer with his trowel and the foreman with his plumbline, above; and notice once again how the buildings recede on the diagonal.

The other is one of my favourites—so simple and so still. It shows the saint dictating her memoirs, standing in her now completed courtyard.

Register the double diagonals for the church (to the left) and the porch (to the right), with the apse of the church being twisted round in the archaic style for us to see it better.

The tiny human figures are surprisingly ‘volumetric’ and Giottesque (especially, in the observation of the fall of the pleats in the heavy fabric of the nuns’ habits: vertically, in the standing figure; then, diagonally across the knees of the scribe, who is looking up; then, almost horizontally in the nun who is reading.)

The next small panel looks for all the world like a simplified painting of a wooden model. It offers an aerial view that captures the very essence of a Tuscan walled city near the sea.

It has been traditionally ascribed to Ambrogio Lorenzetti; but recently a number of experts have attributed it to Stefano di Giovanni, known as Sassetta, who lived from 1392 to 1450 (a hundred years later than the Lorenzetti brothers).

The possibility that it could have been painted either c. 1340 or c. 1440 is really the main point of my little exercise in ‘infilling’.

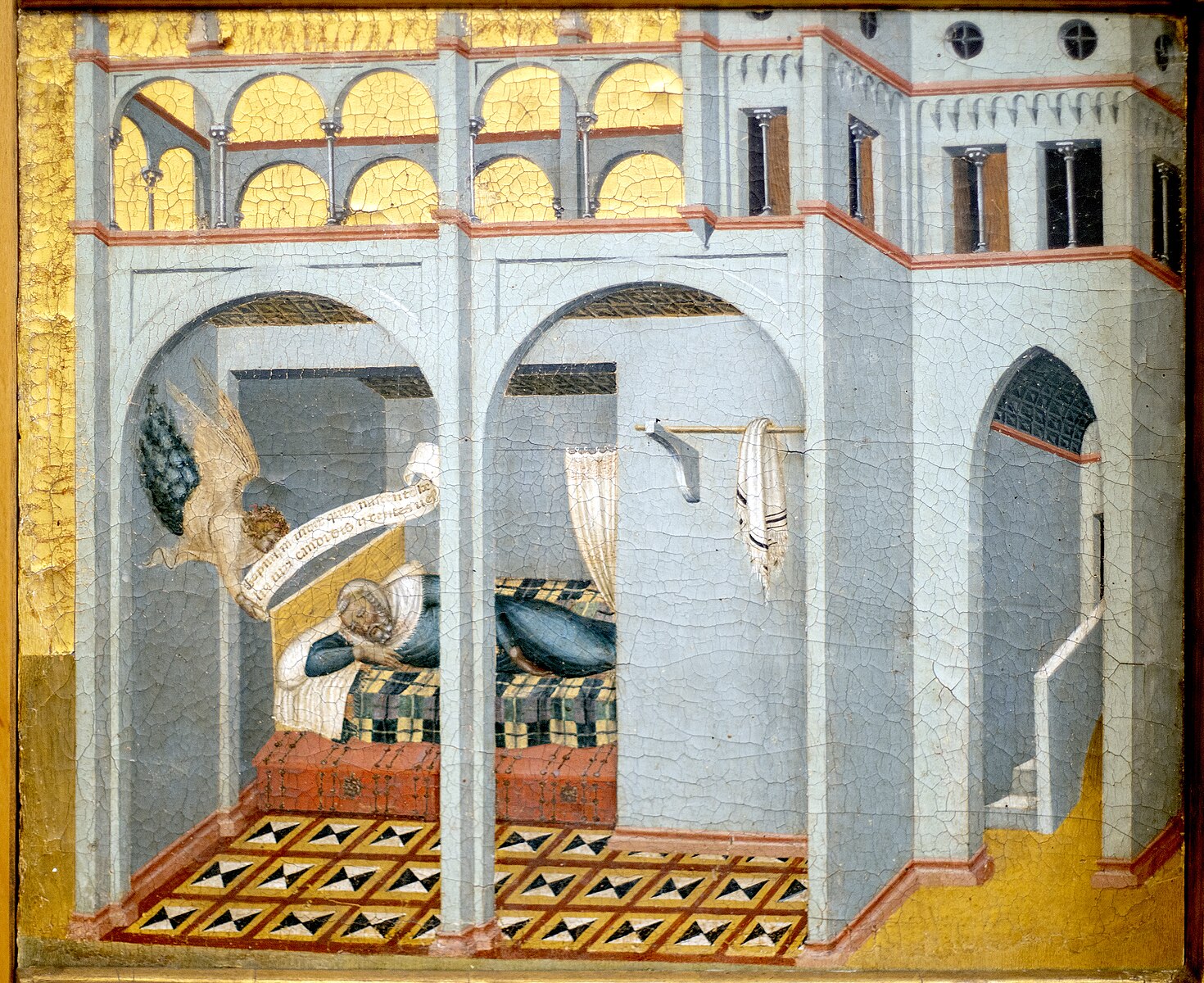

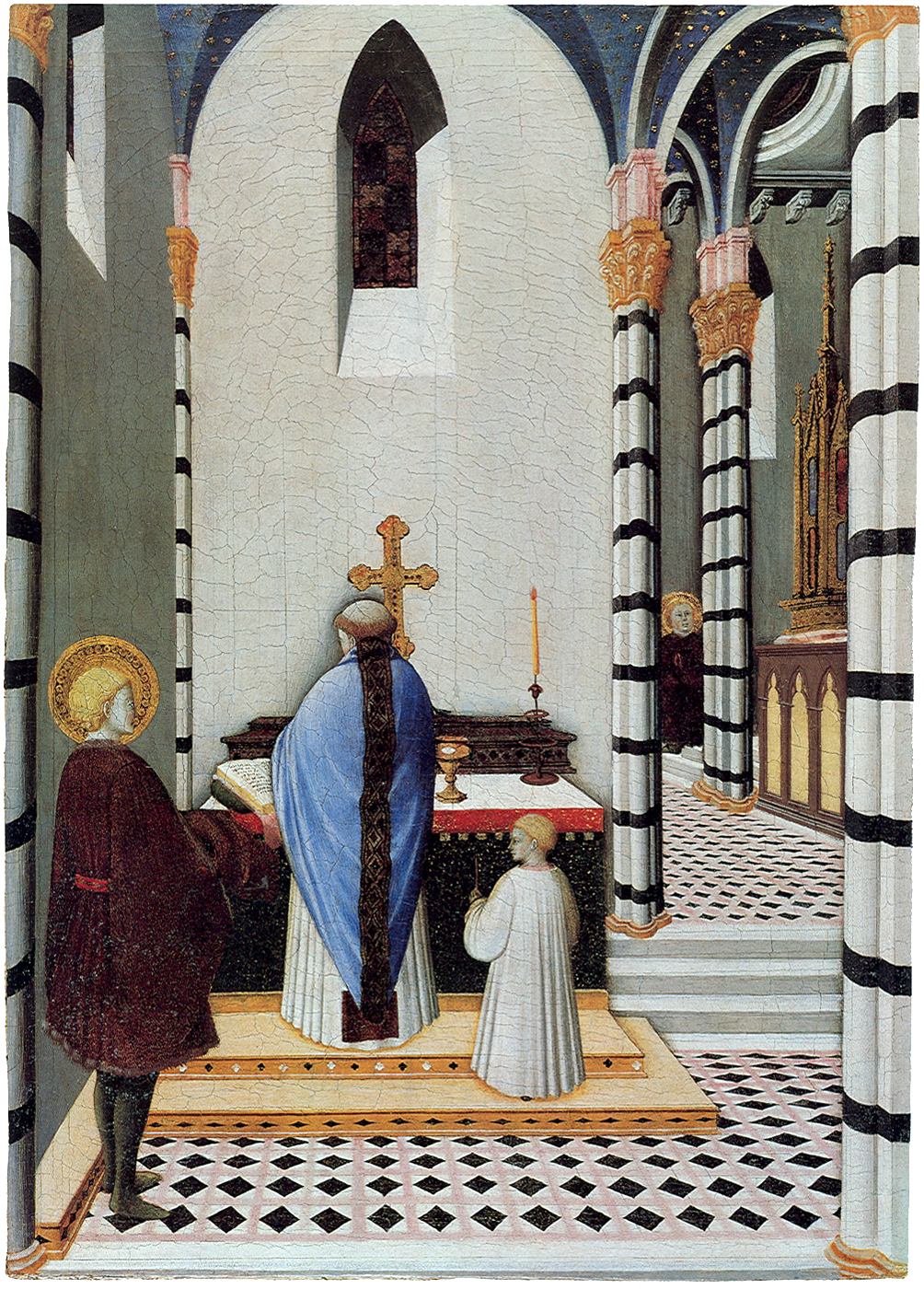

In the same spirit, let us compare another panel by Sassetta (dated 1423–28) with one of similar size by Pietro Lorenzetti, signed and dated 1328.

Both of them were originally commissioned for the same Church of the Carmelites in Siena—Pietro’s, for the predella over the main altar; Sassetta’s, for the chapel of the Wool Guild. The first shows the prophetic dream of the (legendary) founder of the Carmelites. The second shows St Thomas Aquinas at prayer.

You can see at a glance Sassetta’s debts to the conventions observed by his great predecessor fully a hundred years earlier. Notice the smooth colours and the area of gold ground representing the sky; the division of the surface into three by the simple bays of the architecture; the ‘suggestion’ of a greater, unseen space obtained by showing a glimpse through the narrow arch on the right; even the way the orthogonals of the rather primitive perspective recede to a point outside the picture. (The representation of the tiles on the floor and the quilt on the bed is almost startlingly ‘archaic’.)

But Sassetta establishes a far greater depth in his interior scene, thanks to the very up-to-date perspective, which leads the eye back convincingly to the well in the courtyard, and, more strikingly, down the length of the narrow library with its four desks one behind the other.

In the tiny area over the altar (about a square inch of paint), you can see that Sassetta gives us a meticulously detailed account of a Gothic polyptych, showing a Madonna and Child flanked by two saints on each side, with a Christ in glory above, from which a dove is flying out and down to the kneeling St Thomas.

After painting a famous and very advanced altarpiece for the Cathedral in Siena in 1432 (the ‘Madonna of the Snow’), Sassetta executed another even more ambitious altarpiece for the Church of St Francis in Borgo San Sepolcro, the home town of Piero della Francesca.

It belongs to the years 1437–1444, that is, the same period as the frescos in the Ospedale by Domenico di Bartolo.

Seven of the eight narrative scenes from the side of the altarpiece have ended up in the National Gallery in London; and here you see a panel, just over three feet high, combining the first two significant events in the Life of St Francis:

On the left, Francis is giving away his cloak. (Notice how he is tugging the luxurious garment inside out in his urgency, which also accounts for the agitated folds of the shot-silk lining.)

On the right, he is dreaming that the Lord wants him to become a soldier in the literal sense of the word (instead of a champion of the Church).

The style is conservative. Sassetta is close to his Sienese roots in his palette, in the slender human figures and columns, and in the presentation of the bed in the alcove with its chests and star-spangled headboard. Nevertheless, he achieves a certain amount of depth by his correct ‘diminishing’ of the model-like church behind the wall on the hill. And the toy castle in the sky (seen by Francis in his dream) is a charming fusion of poetry and geometrical precision.

We will look at another of the panels from this altarpiece later on, but we are ready now to look at the narratives to which the title of this lecture alludes: The Life of St Anthony Abbot.

The artist is thought to have been a pupil or colleague of Sassetta; and he is thought to be the same man who painted a triptych in the church of the Osservanza, less than two miles to the east of Siena.

It is from this one work that he takes the name by which he is known to art historians: the Osservanza Master (‘Il Maestro del Osservanza’). We know nothing about him for certain, and the other works I shall mention are assigned to him on purely internal, stylistic evidence.

The panels telling the story of St Anthony were brought together for the first time since their dispersal (as a result of nineteenth-century vandalism) in 1988, in an exhibition in New York; and we owe a huge debt to the superb catalogue of the exhibition edited by Keith Christiansen.

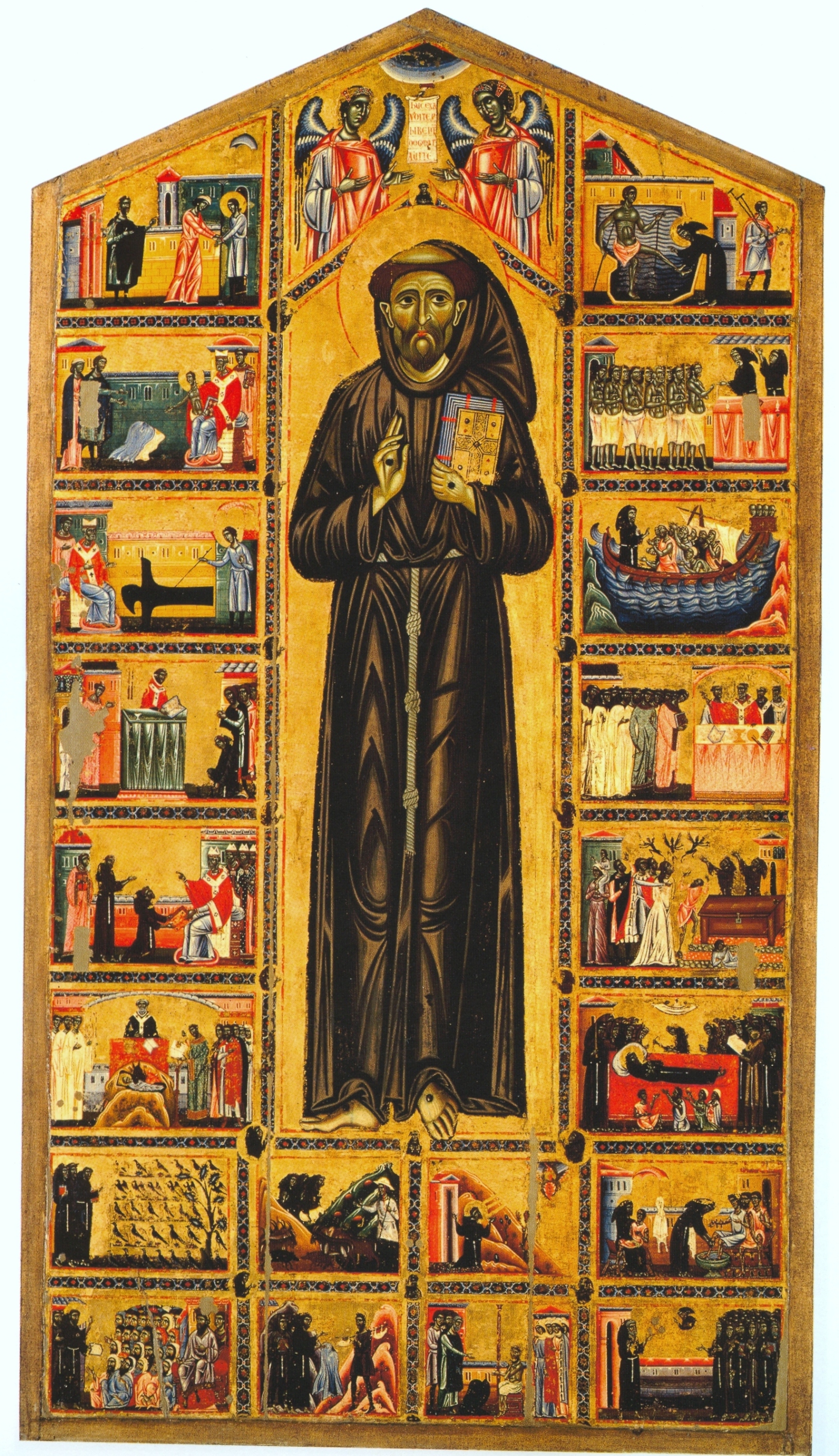

Summarising the carefully nuanced conjectures of the experts, we can say that the eight panels probably lay to either side of a life-size figure of St Anthony, forming an altarpiece (of the kind we have seen several times in these lectures) which combined a large scale public image with smaller intimate ones for the clergy. (You are reminded of the layout of the Bardi Dossal in Florence.)

In our case, there would have been three panels up each side, and two, slightly more ‘horizontal’ in shape, above and below; and the story unfolded from the bottom to the top.

It was probably commissioned by a noble family called the Martinozzi, who in the year 1427 endowed a chapel dedicated to St Anthony in the church of St Augustine in Siena, not far from the Campo.

The painter shows familiarity with the landscape surrounding two Augustinian hermitages about seven miles to the south west of Siena, which were closely associated with Beato Agostino Novello (the ‘Blessed New Augustine’, whom we have already encountered) and therefore with a reformed ‘observant’ movement among the Augustinian canons.

In short, our story is about a third-century saint who lived in Egypt, but it was intended for the edification of an Augustinian community in or near Siena in the early fifteenth century; and we shall see that it is as topical and contemporary in style as the panels we glanced at by Simone Martini and Pietro Lorenzetti, which were also devoted to very little known and very local ‘beati’: Agostino Novello and Umiltà.

It would seem that the whole altarpiece was designed by one man (the Osservanza Master), but that some of the scenes were actually executed by another partner in the workshop, and that some areas were left to assistants.

St Anthony Abbot was born in 251 near Memphis in Egypt, and he lived to a very advanced old age, dying in the year 357. He was an important figure in the history of Christian monasticism, and as such he was very often represented in religious art, where he is always shown as an old man holding a staff with a T-shaped handle (the Cross having often been represented in this shape).

His life story was first told by one of his disciples, Athanasius, in a work well known to St Augustine, who much admired Anthony. His story was retold in Latin by the author of the Golden Legend in the 1260s, and then again in Italian by a Pisan Dominican called Cavalca in the early fourteenth century; and this last version seems to have been the direct source used by the artist.

Cavalca declares that Anthony’s piety was evident from an early age: ‘Whether at home or at church, he practised prayer and thanked God with a full heart and love’. In the first scene of the pictorial narrative (which must have been placed at the bottom the altarpiece, on the left), we see him attending Mass during a reading of the Gospel of St Matthew.

The text was chapter 19, verse 21: ‘If you will be be perfect, go and sell what you have and give to the poor’. ‘Hearing these words’ says Cavalca, ‘as if pronounced by God, not by a man, and imagining that God addressed them for and to him, Anthony took this commandment to heart’.

The main pleasure in the painting lies in the rapt stillness, the absolute immobility of the three figures alone in the vast cathedral, the palpable silence (the saint has taken his shoes off). But there are two points to notice about the architecture.

First, the height of the painted church is as remarkable as its great depth.

And second, the interior is inspired by the real architecture of the nave of the Cathedral in Siena: notice the alternate bands of black and white marble, the pink capitals, and the circle of the cupola over the crossing.

The second scene would have been placed immediately above the first, and the story follows on without a break.

‘Anthony returned home, turned over his land to the people of his village, sold his possessions, and distributed the proceeds among the poor’.

If you look carefully, you can see the haloed saint twice. Before he ‘distributes the proceeds’ in the foreground, half his face is shown in profile (with half a halo), as he comes down the stairs, clutching a money-bag in his hand.

Notice that everybody is in contemporary dress, and that the beggars are faithfully copied, not from ancient Memphis, but from the streets of Siena (one of the beggars is blind and holds his little guide dog on a leash). So too are the widow and her boys, and the barefooted man, of distinguished appearance, dressed in black.

It is also immediately obvious that the building in the background is closely observed from the kind of fifteenth-century palazzi we saw earlier.

In the same spirit, notice all the realistic details: the potted tree on the balcony, the hooks for the awnings in summer, the tethering eye for the horses, the barrel of water, the pile of grain, and, on the wall, the coat of arms of the Martinozzi, the family who presumably commissioned the paintings. (What you see may well have been a pretty faithful representation of their palazzo.)

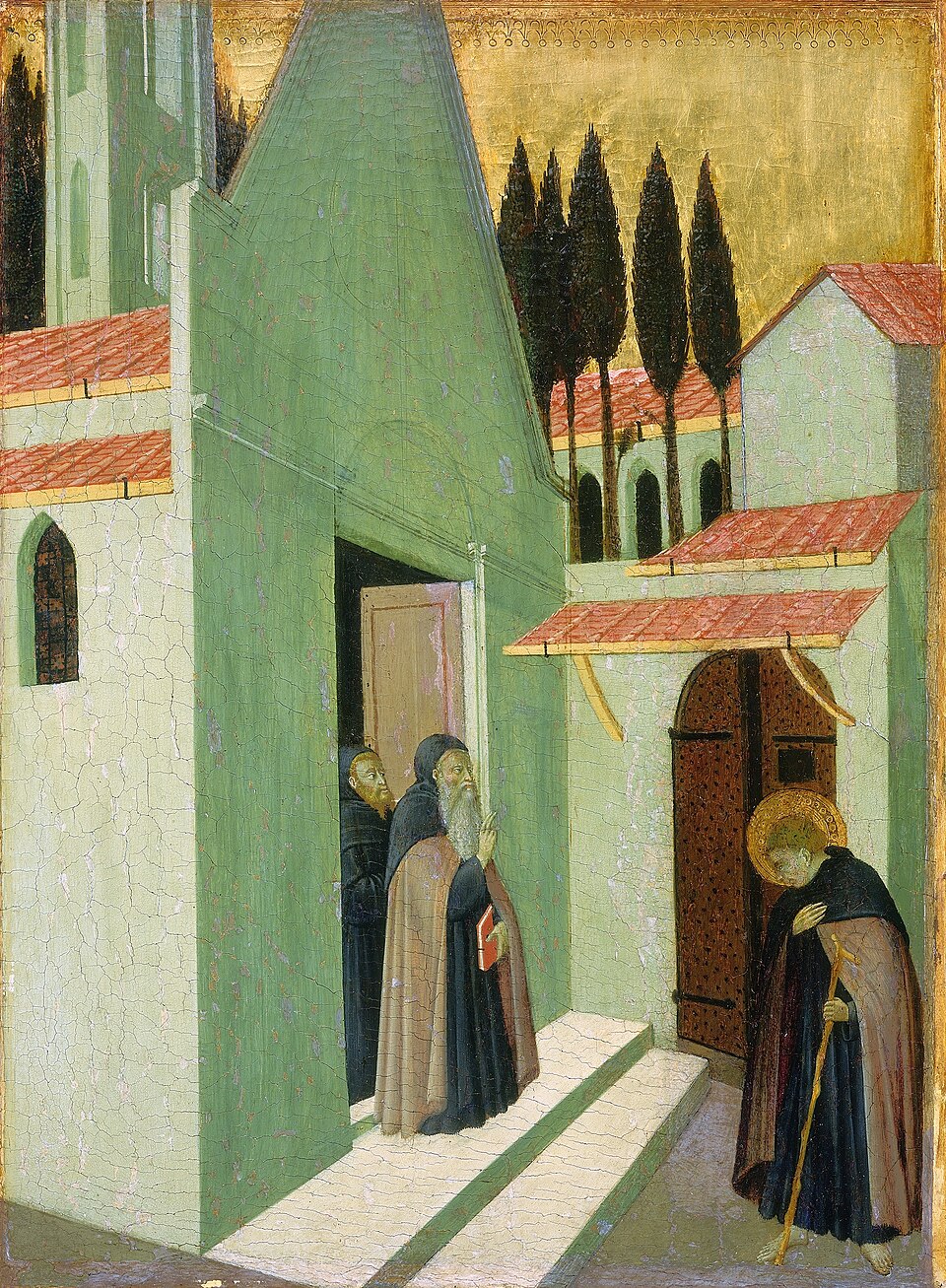

The third scene was also on the left of the altarpiece, immediately above the second.

In Cavalca’s Life of the Saint, we read that Anthony found an old hermit outside the city, and resolved to live by his example. Then, much later, at the age of 35, he decided to live a solitary life—to live ‘alone’ (which in Greek is ‘monachos’: hence ‘mónaco’ in Italian and ‘monk’ in English). He returned to the same hermit, urged him and his fellows to follow him into the desert—and left on his own!

The fact that Anthony is represented as a young man suggests that this was the original meeting, but his attitude, the presence of the T-staff, and the fact of the hermit’s giving his blessing suggest the later leave-taking.

The perspective differs in effect from the previous scene where the significant wall of the palazzo lay parallel to the picture plane. Here we are shown a boldly oblique view of the façade of the church; and in this case, the artist is concerned to suggest space rather than define it. We are invited to imagine the space beyond the windows and doors in the inner courtyard, as we interpret the clues provided by the tops of the cypresses, the upper storey of the cloister, and the bottom of the campanile.

Christiansen’s catalogue states that the building resembles the Augustinian hermitage at San Leonardo al Lago; and this hypothesis fits in well with other evidence about the probable commission and with the artist’s clear intention to make his story as ‘up to date’ and ‘relevant’ to his audience as he possibly can.

According to Cavalca, Anthony had no sooner decided on a life of abstinence and discipline in the desert than ‘he was beset by temptations of the flesh, and the Devil appeared to him in the guise of a woman’. (You can see that the Devil took considerable pains with his seductive disguise—except that he forgot to conceal his bat-like wings.)

Anthony is mature now, bald and bearded, occupying space more confidently than in scenes two and three (a fact which, according to the experts, points to a different hand at work, a hand perhaps more under the influence of Sassetta).

He makes a gesture of ‘Get thee behind me, Satan’, and clutches his robe to his T staff, to reveal a crucifix hanging at his girdle.

The building is much more schematic—almost a pictogram—but this is precisely because it is not a church, but a cell in the wilderness, a romantically coloured ‘bothy’, or Alpine ‘rifugio’.

The charm of the picture lies in the lunar wildness of the landscape. Three stylised hills are divided by a pebbled path, there are ilexes scattered in the foreground and forming a grove in the distance; and above them, very high, the sky forms a curve as though reflected in a convex mirror, or, more probably, so as to suggest the first of the heavenly spheres, an effect heightened by the bands of clouds and clear sky.

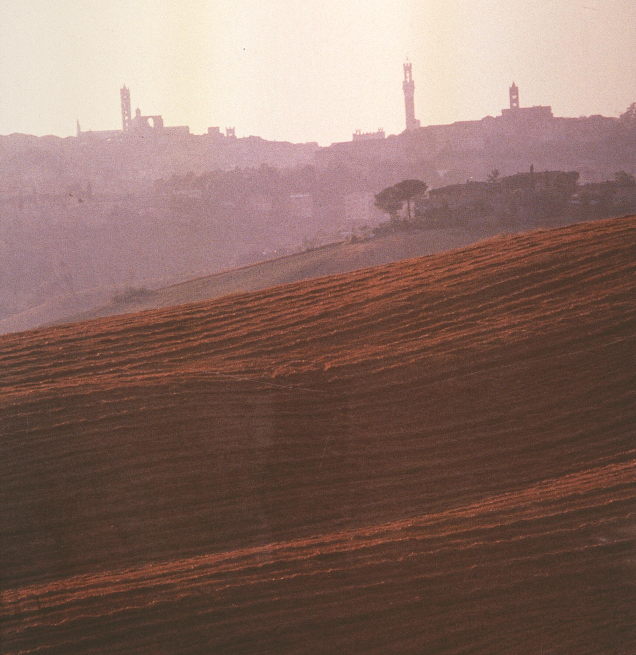

(The hills may seem drastically over-simplified; but the photograph reminds us that there are not dissimilar landscapes within sight of Siena to this day.)

Moving over to the other side of the main image on the original altarpiece, we come to the second of Anthony’s three trials in the wilderness. After the wiles of the temptress in disguise, the devil sends in four demons—two of them still airborne, like jet fighters on a punitive, strafing raid.

Cavalca places the episode immediately after Anthony’s departure from the monastery of the hermit; and the artist clearly intends us to understand that the church, campanile, cloister and cypresses are the same as those in the third panel, seen from a totally different angle and at a great distance. (There are ilexes again, as sharp in the distance as in the foreground; three simplified hills, but laid out so that they recede to the left; and a pebbled path, sweeping in a very easy curve this time, emphasising the direction of the aerial attack.)

The nearest of the flying devils holds a snake; two others, talon-footed, stand over the saint and drub him with big sticks. Anthony’s staff has fallen to the ground and he himself has been knocked over; but he scowls resolutely and refuses to be ‘counted out’.

It is all distinctly crude in conception and execution, as will become apparent if you glance at the panel illustrating the same subject by Sassetta.

(You may like to note in passing the difficulty that art historians face when they attempt to group anonymous works together and ascribe them to one Master. On the one hand, they want to link the scattered panels to form a cycle, and to assign this cycle to the anonymous painter of a surviving altarpiece (in our case that for the Osservanza); on the other, they want to distinguish at least three different hands!)

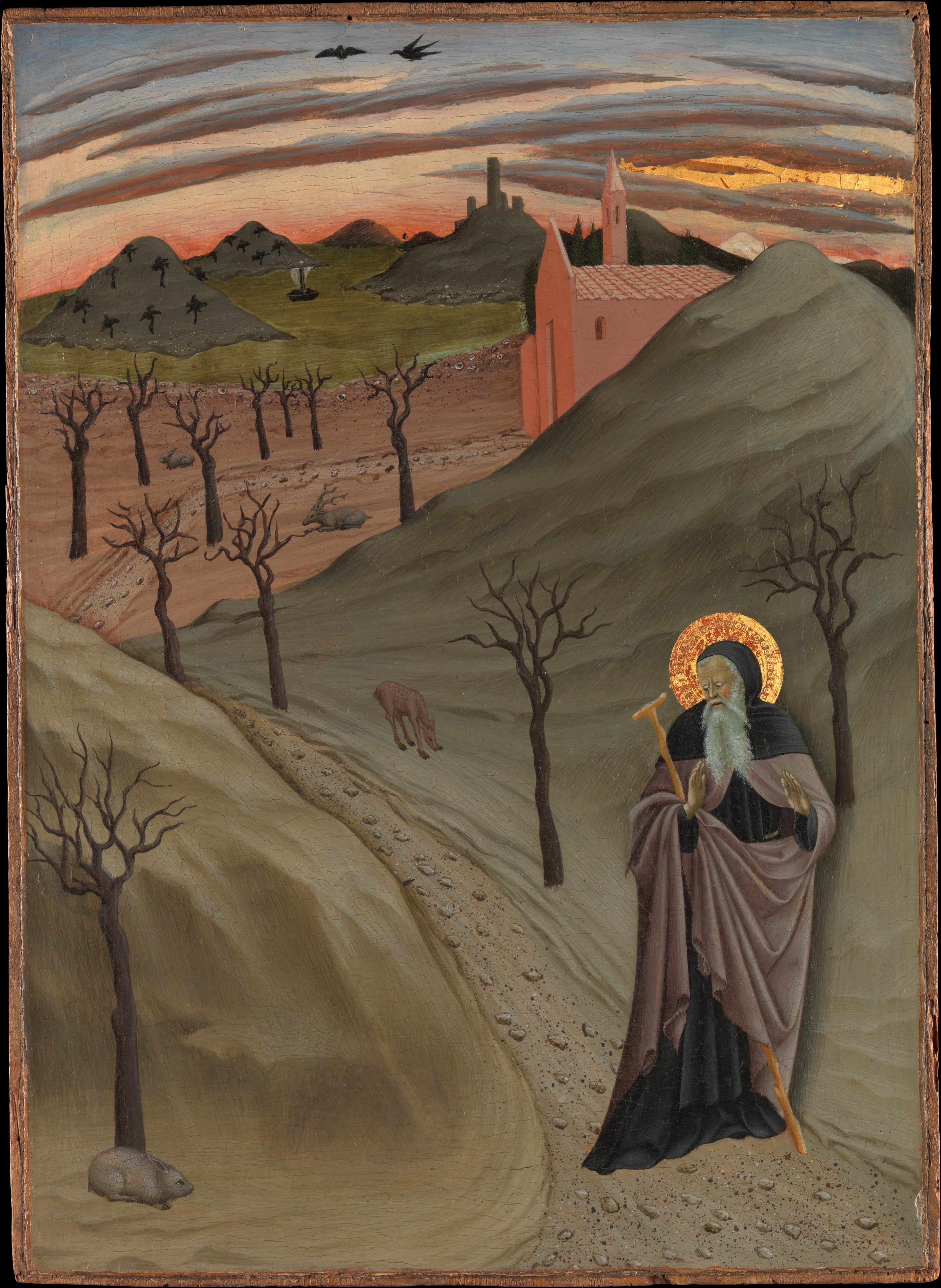

We pass now to the third of Anthony’s temptations in the desert, which, in Cavalca’s narrative, takes place soon after he left the hermit’s monastery, but is here represented as occurring when he was already an old man.

Unlike the earlier scenes, where you could work out what was happening from the painting itself, the situation is far from perfectly clear until you read the story.

The devil has tempted Anthony first with a silver plate (not illustrated), and then with a heap of gold, ‘from which he fled as though from a fire’.

You can sense his astonishment in his gaze and the double-handed gesture, which results in him letting go of his T-staff (it stays upright, in the crook of his elbow, but only because it is caught in the complex folds of his cloak).

This is one of the most admired panels in the little cycle, so let us take in the whole surface, starting from the top.

Once again, there are clear bands—of sunset colour, clouds and birds—in the sky (or heavenly sphere). Again, too, there are distant hills and the towers of a fortress in the contado; then a lake with a sail, and a pink building which we may reasonably interpret as the hermit’s cell of the fourth scene.

The pebbled path curves (leaving a wolf to the right, and a rabbit or ‘coney of the desert’ to the left), then dips, vanishes and reappears (dividing a stag and another coney).

The essence of this symbolic landscape, however, lies in the stunted, gnarled and leafless trees anticipating photographs of Flanders during the First World War.

The seventh scene is still set in the wilderness. The chapel on the skyline is pink, and is probably meant to be the same cell we have seen twice before. The trees presumably stand for ilexes once again, and perhaps for the ‘ilex grove’ (‘il lecceto’ in Italian) at the Augustinian hermitage of that name. You will notice too that travel in the wilderness is facilitated by the same kind of stony path.

For the first time since the opening two scenes, our hero appears more than once in the same frame: setting out on a journey (with his-T staff used like Dick Whittington, to support the weight of his pack); stopping to ask the way from a passing centaur; and embracing St Paul the Hermit in the foreground. (Notice the overlapping halos.)

The story (from St Jerome, retold by Cavalca) relates how Anthony had a dream when he was already 90 years old, revealing that he was not the first desert hermit, because this honour belonged to Paul, who was already 113 years old.

In the same dream, he was told to seek out the older man and do him honour.

He was helped on his journey by a satyr and a wolf, as well as by the centaur you see; and we are told that he met and embraced Paul near a rocky cave.

The main interest here is in the unusual story-line, but do take a look at the design of a similar cave in the second little painting, to understand the kind of stylistic evidence that leads the specialists to argue the case for an attribution.

(The panel comes from the predella of the altarpiece of the ‘Osservanza’, from which our anonymous painter derives his nom de plume.)

We move on to the final scene, which represents, as so often in such a saint’s life, the funeral of our hero.

The attendant clerics are represented rather woodenly, with vacant expressions and unnaturally bell-like robes. Once again the chief interest lies in the representation of architecture.

As in the second scene (the one in the courtyard), the main wall of the church is parallel to the picture plane. Under the foreshortened soffits of the ceiling, you see the rounded arches of the window vanes in the clerestory, the wall being given its character by the five ‘bands’ of coloured stone (much as we saw in the Cathedral, and much as we find in so many of the main churches in Siena and elsewhere in Tuscany).

The artist does exploit perspective to define space (in the foreground and in the transept), but, as in the courtyard-scene, he prefers to get his effects in the fourteenth-century way—by suggestion.

He flings open both wings of the main door open to reveal the cypresses in the cloister, which has a window in its rear wall hinting at greater depths beyond; and he uses an arch to frame an arched door, half-open, to disclose a cupboard in the sacristy, which has one of the two doors open to hint at its contents.

I have been lucky enough to spend the whole of my academic career in Cambridge; and I cannot conclude the lecture without mentioning a very beautiful work, attributed to the Master of the Osservanza, in the manuscripts collection of the Fitzwilliam Museum, where you will find this lovely miniature, about ten inches high, cut from an Augustinian choir-book by another nineteenth-century vandal.

It illustrates, on the left, the funeral of St Monica, and, on the right, the departure of her son, St Augustine, who is setting sail from Carthage to Rome.

(It would seem that there was a renewed interest in Saint Monica in the early fifteenth century, as a result of which her body was removed in 1431 from Ostia to Rome itself. This miniature was probably executed for one of the Augustinian communities in or near Siena, mentioned above).

Notice, on the left, the arches of a funerary chapel in the early Renaissance style, but proceed immediately to enjoy the Sienese poetry of the scene on the right.

A medieval caravel, like the ships used by Columbus, is completely filled by just two laymen and seven Augustinian canons (the one with the halo must be Augustine). The bearded master of the vessel is holding the sheet lightly in his left hand, as if he were sailing a dinghy. It is a ‘fairy ship’ on a ‘fairy sea’.