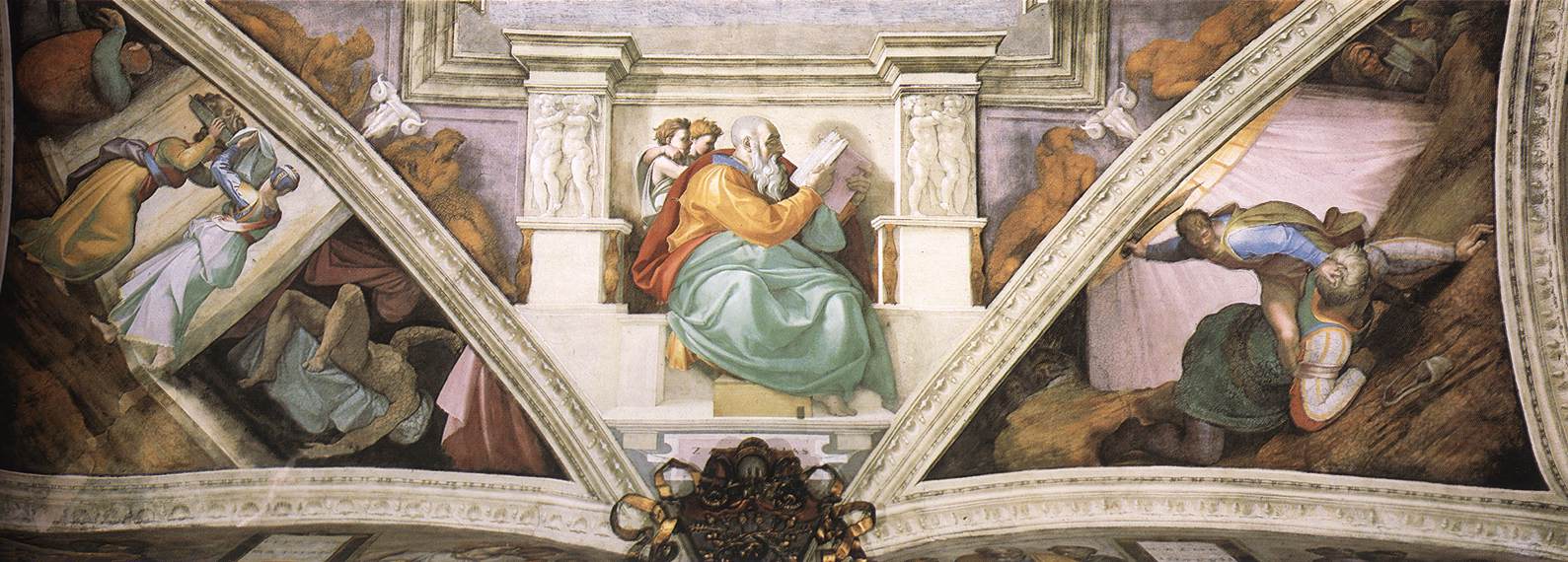

I asked you go on looking at the area containing the prophet Isaiah and the Delphic Sibyl until you played Michelangelo’s game, connived with him, suspended disbelief, and saw the top of the wall and the ceiling itself straighten up and become a complex piece of classical architecture.

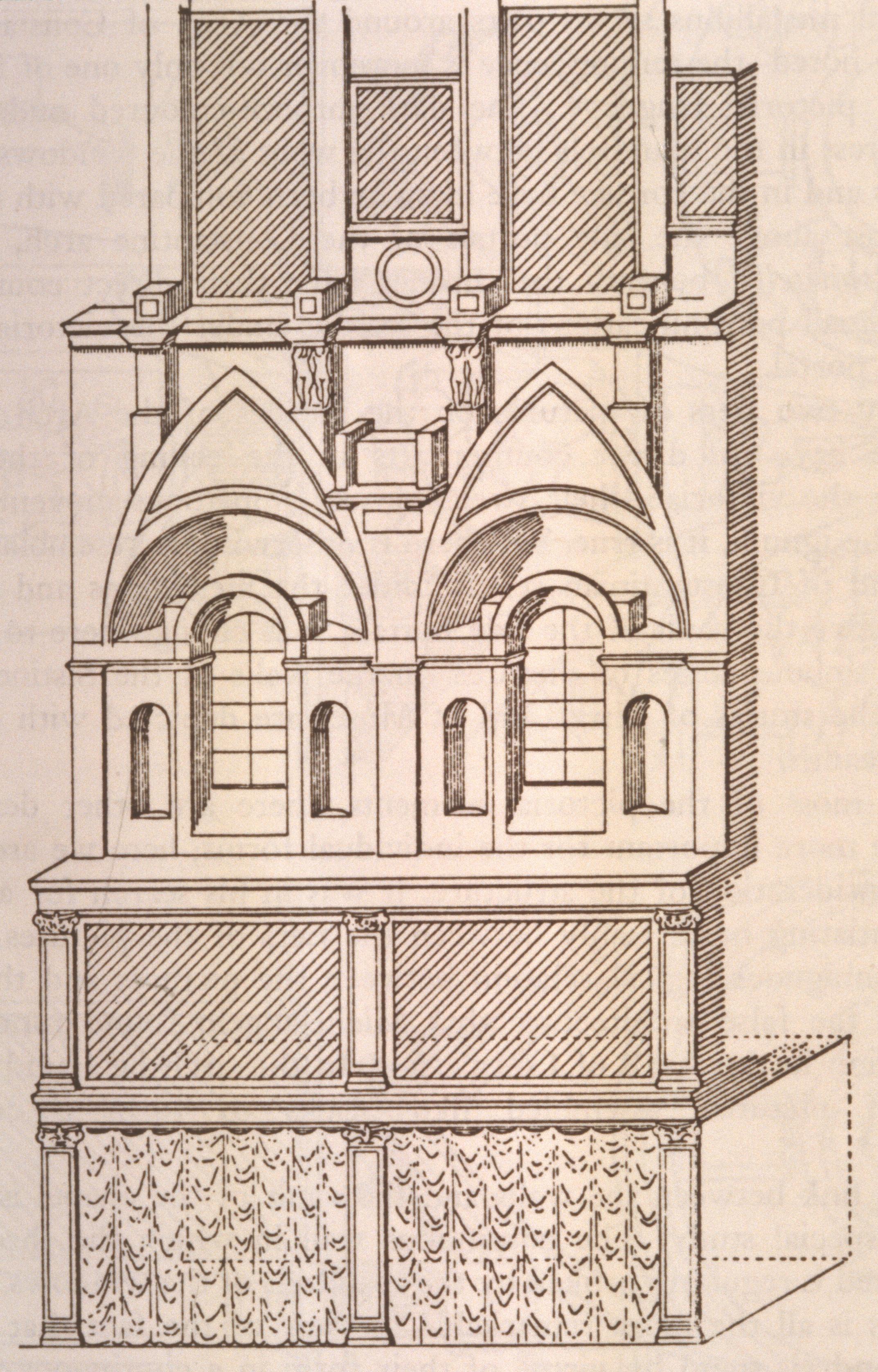

Just to be absolutely clear—the wall you see in the diagram is genuinely vertical as high as the top of the windows, and had been frescoed in the 1480s.

Michelangelo makes it seem to go on rising in the vertical plane, by painting lots of half-size bronze and marble statues that seem to act as supports for a cornice at the top, and apparently hollowing out two series of recesses in this fictive wall (the shallow lunettes and the slightly deeper spandrels) where human beings can squat or perch, and apparently constructing two series of projections from the fictive wall (the thrones and the ‘bollards’ above them), big enough for very large human beings to sit in extravagant poses, either with their clothes on, or with their clothes off.

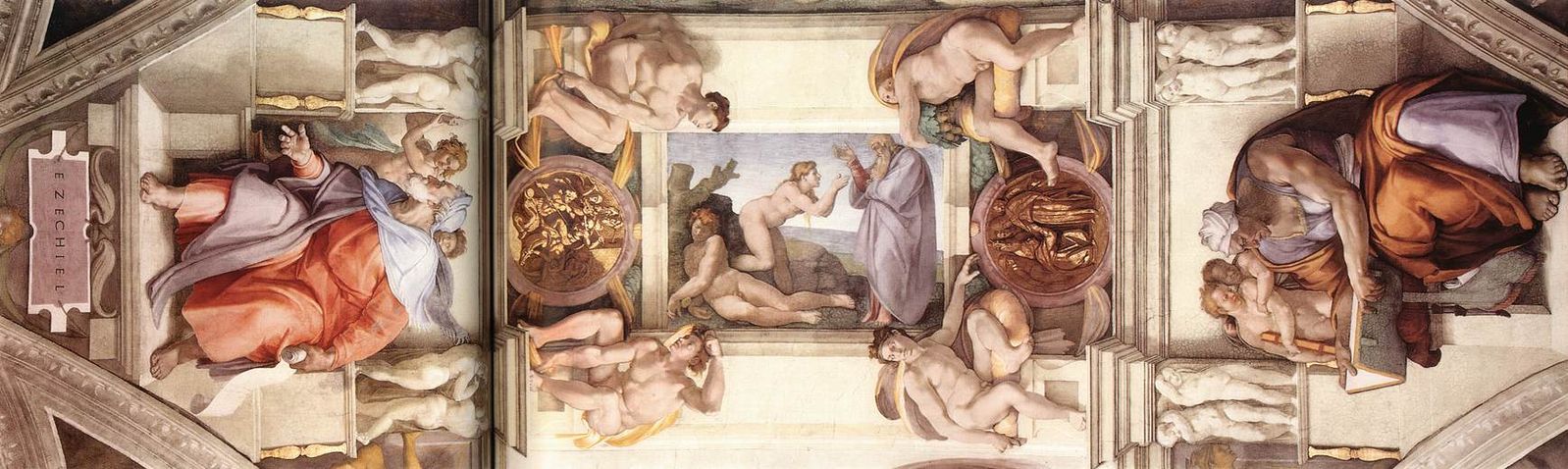

In the middle section of the previous lecture, we did some careful homework on the basic elements in the complex pattern of this fictive architecture by looking at many images from the eastern end of the Chapel—the end where Michelangelo began work, and which he frescoed from 1508 to 1510.

In the final section, we paid close attention to the poses of the prophets and sibyls who occupy the fictive thrones at the western end, which Michelangelo painted between 1511 and 1512, including the Libyan Sibyl, nearest the altar (whom you see again here).

In this lecture, we are going to begin by looking at the more or less horizontal part of the ceiling, studying the narrative paintings in the order in which the stories are told in the Bible.

This means you will be standing (mentally) with your head tipped back like Michelangelo when he did the painting, walking backwards away from the altar in order to focus on the next scene, and therefore going against the order of execution from the relatively more accomplished and bolder, to the relatively more youthful and naive.

As you examine each episode, I shall be trying to help you understand the reasons behind the choice of the scenes, how they relate to each other, and how they were made to fit in with the existing paintings of the first thirty Popes and the Parallel Lives of Moses and Jesus on the walls (discussed in great detail in the second lecture).

The relationships may seem a little complicated at first, but I want to stress that the conceptual scheme is not all that complex, nor all that unusual, and that you do not have to believe everything you may have read about sophisticated patterns of thought deriving from Florentine neo-Platonism, or from ‘The Pagan Mysteries of the Renaissance’, or from the more wild-eyed interpreters of the Bible.

Indeed, I think you will find the scheme quite easy once you have grasped the relationship implicit in the fact that we used to give all our dates as either BC or AD, and once you have grasped the relationship implicit in the Christian treatment of the Jewish Sacred Books as an ‘Old’ Testament, preparing for the ‘New’.

Michelangelo’s task on the ceiling was like completing a play of which the second act and the fifth (the stories of Moses and Jesus) already existed, and for which everybody knew the broad outline of the missing parts.

Essentially, we can divide Michelangelo’s contributions to the whole drama into two parts.

First—and deservedly most famous—Act One, running along the whole length of the centre of the ceiling.

There are nine narratives which deal with the Creation, the Fall, and the early history of man’s relations with God in the period between the Fall and the birth of Moses, when there was no Law to regulate that relationship, a period culminating in the separation of the Jews and Gentiles.

The Second Act was already in place—on the south wall—in the story of Moses and the giving of the Written Law to the Jews (principally, the Ten Commandments). So, too, was Act Five—on the north wall—in the story of Jesus, the Son of God and Redeemer of Mankind, who brought the Evangelical Law to the whole world.

Michelangelo’s other contributions constitute Acts Three and Four of the sacred drama; and they deal with people and events that link Moses with Jesus.

The people and events are divided into four distinct sub-groups, placed in four distinct zones of the ceiling; and the four distinct links might be labelled: Prophecy, Prefiguration, Repetition and Genealogy.

(They are set out here, for convenience of reference, but there is no need to commit them to memory.)

On the thrones: individual Jews and Gentiles who prophesied the coming of the Redeemer. |

In the huge corner-spandrels: historical events that prefigure the Redemption. |

In the tiny medallions, held by the nudes: events in Jewish history that re-echoed the Fall or re-affirmed the Written Law. |

In the spandrels and lunettes: individuals who linked the patriarchs genetically with the parents of the Redeemer, i.e. the Ancestors of Christ, listed in the first chapter of St Matthew’s Gospel. |

To put it another way: well over half the figures we shall study in this lecture, and nearly two-thirds of the painted surface on the ceiling, derive from the first nine chapters of the Old Testament and from the first chapter of the New.

The choices are so far from being unusual that all the major characters from the Old Testament who appear on the ceilings and walls of the Sistine Chapel had already been represented by Lorenzo Ghiberti in the ten diminutive panels of his Gate of Paradise, cast in bronze for the Baptistery in Florence, installed in 1452, but conceived as early as 1425.

Let us cast the quickest of glances at one of Ghiberti’s panels. (The Gate of Paradise is the subject of a whole lecture in the Florence series.)

Michelangelo’s first three scenes (those closest to the Altar Wall) are an amplification of just one relatively insignificant area in Ghiberti’s first panel. (The detail comes from the sky, and, as the photograph makes clear, it is in very low relief: technically speaking, this is stiacciato, ‘squashed flat’; in modern Italian, ‘schiacciato’).

It shows God the Father—bearded and in a wizard’s hat—framed by concentric circles representing the heavenly spheres of medieval cosmology, and accompanied by a host of angels, whose robes billow out to express their descending flight.

It is obvious that Ghiberti (and the iconographical tradition within which he was working) was influenced by the phrase in Genesis 1:2, which in the King James Version is translated as ‘the spirit of God “moved” upon the face of the waters’.

In Latin, this is ‘ferebatur super aquas’, which it would be natural to translate as ‘was “borne” or “carried” above the waters’: hence the hovering position.

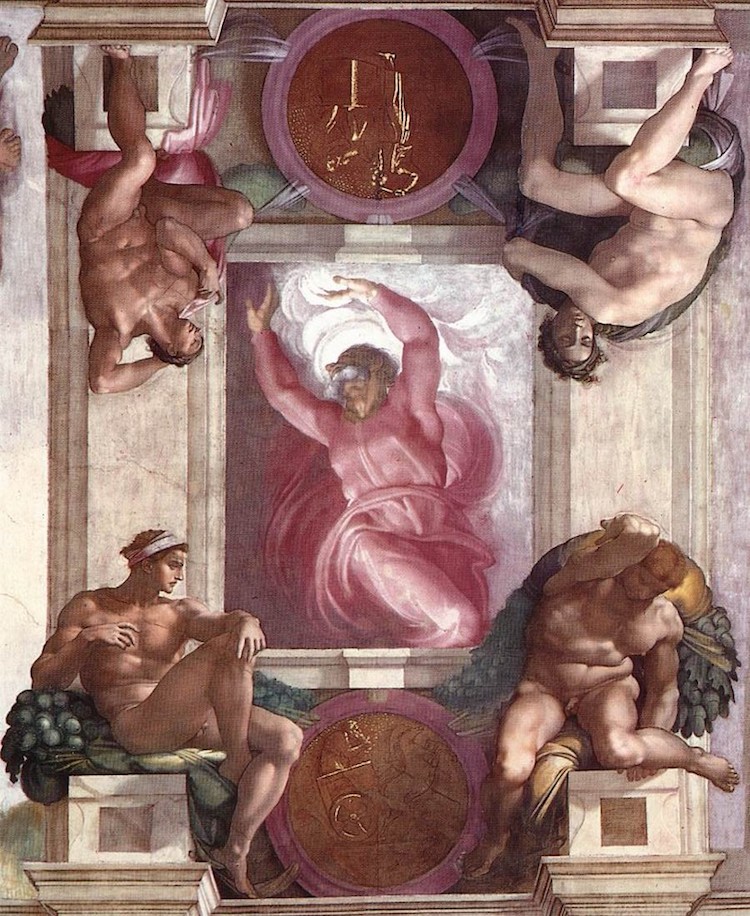

With Ghiberti’s sixty-year-old panel in your mind, then, take up your position in the centre of the chapel, face the altar (doing your best to block out the fresco of the Last Judgement), look up at the prophet Jonah on his throne in the central pendentive, and follow the direction of his gaze towards Michelangelo’s first scene on the ceiling.

This is one of the two ceiling pictures that absolutely demands to be seen from the floor, about sixty or seventy feet below, when you really do get the impression that God is ‘hovering above you’.

The angle of vision is as difficult and original as Ghiberti’s was easy and predictable.

You can see God’s neck and Adam’s apple, and the under edge of his beard, but only a suggestion of his eye and nose.

The implied movements are helical—in fact, a double helix about the same axis, because the swirl of the robe implies an earlier movement anticlockwise, whereas the hips and the legs have just gone clockwise, while the torso is now twisting anticlockwise again.

All this is in order to give the two arms maximum ‘purchase’, as the right hand thrusts, like a swimmer’s, against the murkier area, and the left hand is about to pull into the ‘clearer water’.

This is the moment described in Genesis 1:4, when God, having said ‘Let there be light’, ‘separated the light from the darkness’.

I doubt whether even Leonardo ever produced a ‘more painterly’ and less ‘sculptured’ outline than this superbly free brushwork. And yet the inspiration came from sculpture, because the face, rib-cage, nipples, and central ‘gully’ derive from the classical Laocoön, which we looked at in the previous lecture.

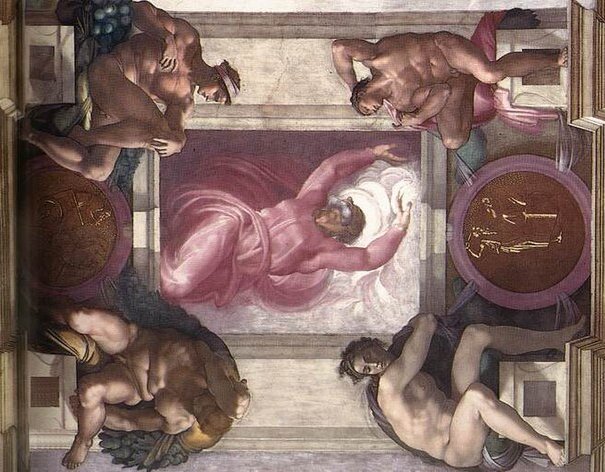

Now you must retreat a little (or raise your head still more acutely) in order to take in the second scene.

It is one of the four larger narratives on the ceiling.

It presents two separate images of Jehovah—advancing and retreating—which are much clearer in outline, but even more daring than the first.

The scene to the left must be intended to represent the labours of the third day (Genesis 1:9–13), when God ‘let the Dry Land appear’, ‘called the Dry Land “Earth”’, ‘and said: “Let the Earth put forth vegetation, plants yielding seeds, and fruit trees bearing fruit…”’

We scarcely register the plant-life (the leaves resembling those of an ash tree, rather than the oak we might have expected), as we look at this most amazing of all the expressive ‘rear views’ in the chapel—and of all Michelangelo’s feats of foreshortening.

We see Jehovah seemingly sprinting away from the ‘starting blocks’, his right arm reaching forward, the fingers tensed, the left hand pulling backwards, and already creating enough wind to sweep his hair back, to set the robe flying, and to expose his buttocks.

The scene to the right of the fresco illustrates the labour of the fourth day (Genesis 1:14–19), even though the composition of the painting invites us to read it before the other side (arrival preceding departure).

Here Jehovah is accompanied by angels (as he was in Ghiberti).

He is hurtling from right to left, upwards and forwards.

At the very moment when Michelangelo released his metaphorical shutter, he rears up his chest, twists his torso to his left through an angle of almost ninety degrees, and stabs forward with his right forefinger (almost like Lord Kitchener in the famous recruiting poster) to create the sun, ‘the great light that rules the day’—thereby causing one of the angels to shield his eyes from the glare (look at the cast-shadow over the angel’s closed eyes!)

Simultaneously, he flings back the forefinger and thumb of his left hand to create the moon (the silvery mass which is just visible), making one angel duck in alarm, while the other clings onto his turban.

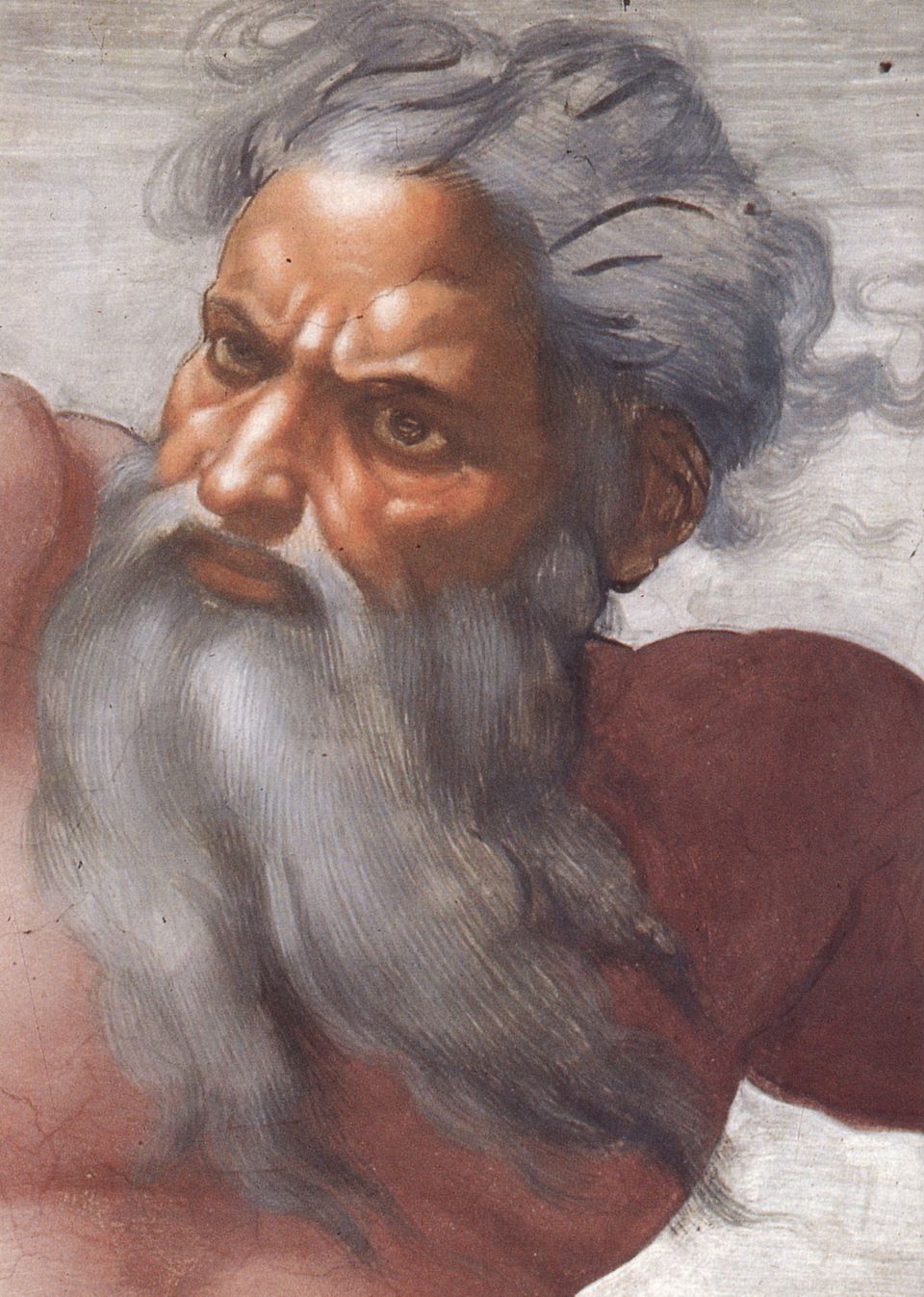

In this fresco, we do see God face to face, so let us close in.

The lobes of his forehead bulge like two eggs in eggcups above the beetling brows and fiercely autocratic eyes.

This is a God who has no need of a rod of authority (as he had in Ghiberti), and who makes us understand why the Book of Genesis could comment, laconically, ‘and it was so’ (et facta est ita).

(The cleaning in the 1980s confirmed the astonishing zest and confidence of Michelangelo’s brushstrokes in rendering the hair and beard, especially where they dissolve into the air.)

Retreat a little further from the altar now, and crane your neck to see the foreshortened figure of God swooping down on you from the confines of another small rectangle.

The scene is generally, but not universally, understood to represent the work of the second day (Genesis 1:6–8), when God ‘separated the waters which were under the Firmament from the waters which were above the Firmament’.

It is here that Michelangelo is closest to Ghiberti, even though he shows only three angels and they are only peeping out from the ‘tunnel’ formed by God’s robe (which might vaguely recall the concentric spheres of the Gate of Paradise).

But, unlike Ghiberti’s, Michelangelo’s God really does seem to ‘hover’ above you when you are in the chapel.

His gesture of ‘separation’ is drawn with amazing confidence from a very difficult angle (look at the right arm).

And, in the context of the chapel, the gesture seems to express a benediction—an interpretation, perhaps, of the last verse of the first chapter in Genesis:

‘God saw everything that he had made, and behold it was very good’.

You have stepped backwards yet again, and you should be positively gawping as you stare up in astonishment.

You seem to have known the image all your life and yet—if all is going well—you should seem to be looking at it for the first time ever.

Before you turn the page, enjoy the whole fresco for a moment as an element in the design of the ceiling and in the glory of its full width. (It really is as broad as the rectangle in the previous scene together with the purple medallions on either side.)

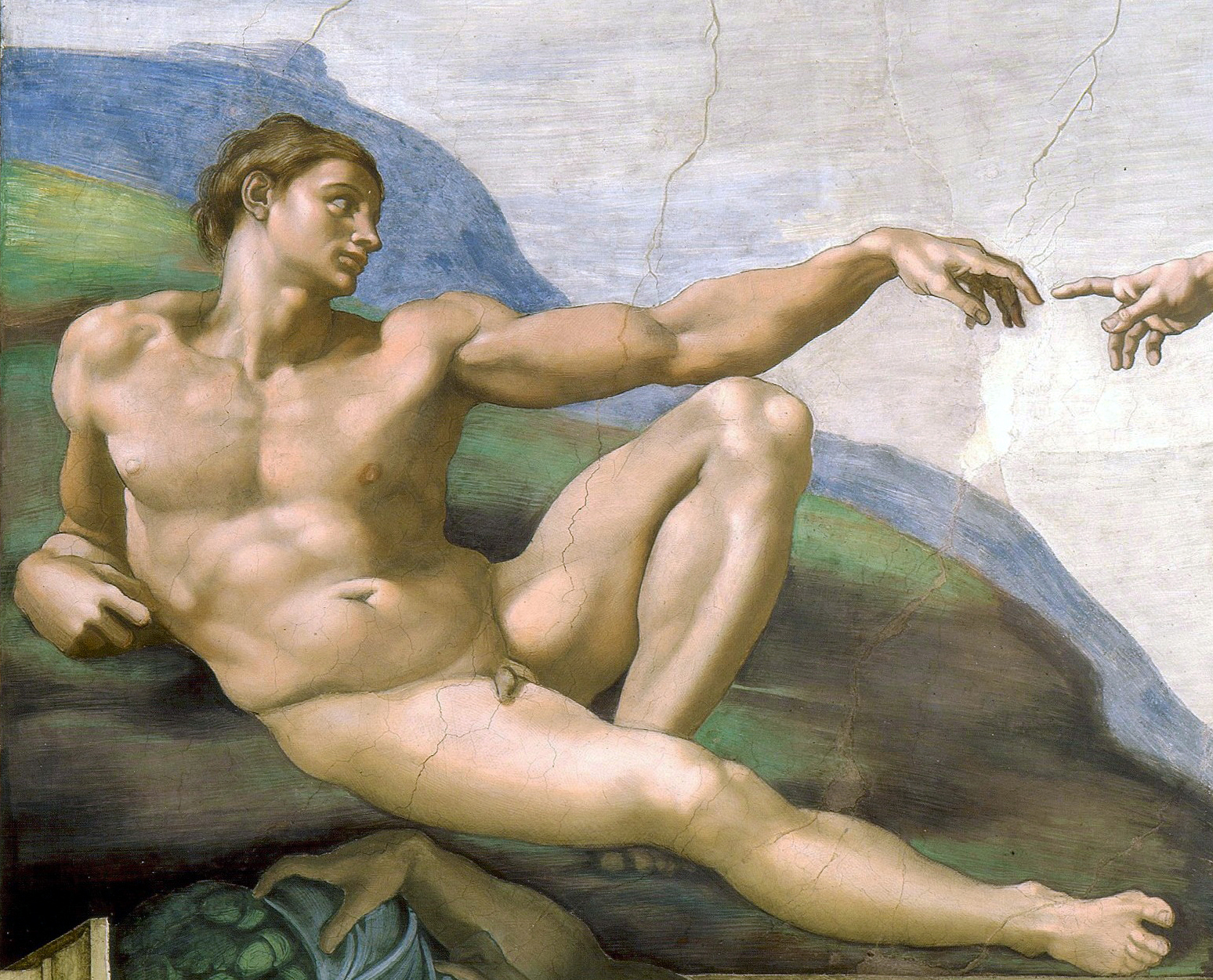

Recognise Jehovah and his angels in the sky. Remember my presentation of the male ignudi in the previous lecture (where I was trying to analyse their poses as if their heads, arms and legs were all ‘inflections’ added to the ‘stem’ of the classical Torso Belvedere). And make a quick mental note of Adam’s pose (reclining, with the left knee strongly flexed, as it supports his extended left arm).

Then resume reading to deepen your understanding via a couple of new insights deriving from the text of the Bible and two earlier examples of the iconographical tradition.

We have arrived at the group of narratives which occupy the centre of the ceiling.

(Once again, the three scenes are framed in rectangles of unequal size, but here the sequence is ‘large-small-large’, rather than ‘small-large-small’.)

This second triad is still devoted to the Work of Creation (opus creationis), as described in the opening of the Book of Genesis, but we come now to the Making of Man.

(Before we glance at the Latin of the second chapter, it may be helpful to absorb the following note about a word-play in the original which is lost in any translation.

‘In Hebrew, the word “Adam” (אָדָם) generally means “man” or “human”. It can refer to humanity as a whole or a specific individual, particularly the first man in the Bible. The word is also linked to the Hebrew word for “earth” or “ground,” “adamah” (אֲדָמָה).’)

The words to notice in the Latin are formare and limus, inspirare and spiraculum, vita, vivere and fieri (‘to become’, the infinitive of factus est).

Limus does mean ‘clay’ of the kind used by a sculptor when ‘moulding’ a terracotta head. Formare can and does mean to ‘shape’ a piece of pre-existent matter into an artefact, and the verb could be used of a sculptor chiselling away at a block of marble.

Michelangelo and Ghiberti might have used this pair of words every day of their professional lives to refer to their normal task (in Italian, limo and formare).

There is an etymological link between the noun ‘breath’ (spiraculum) and the verb ‘to breathe into’ (in-spirare). And we know that something ‘has come to life’ (vita), or has ‘become living’ (vivens) when we see it can ‘breathe’.

וַיִּיצֶר֩ יְהוָ֨ה אֱלֹהִ֜ים אֶת־הָֽאָדָ֗ם עָפָר֙ מִן־הָ֣אֲדָמָ֔ה

וַיִּפַּ֥ח בְּאַפָּ֖יו נִשְׁמַ֣ת חַיִּ֑ים

וַֽיְהִ֥י הָֽאָדָ֖ם לְנֶ֥פֶשׁ חַיָּֽה׃

Et formavit igitur Dominus Deus hominem de limo terrae

et inspiravit in faciem eius spiraculum vitae

et factus est homo in animam viventem.

(And the Lord God formed man of the clay of the earth: and breathed into his face the breath of life, and man became a living soul.)

Literally speaking, of course, Michelangelo could never have ‘breathed life’ into the ‘face’ of a body he had sculpted so that it ‘became a living soul’ (although, metaphorically speaking, this is precisely why we revere him for his handiwork). Only God can create something ‘in his own image’—a being who is not just alive and sentient, but a rational creature capable of knowing the truth as true, and capable of the knowledge of good and evil; self-aware and capable of judging his own actions as being wrong or ‘right’; capable of slithering like a serpent or standing ‘upright’ on his own two feet.

But this was the miracle that Michelangelo was called on to represent. (There was an additional challenge in that he would risked bathos if he had attempted to portray the biblical text literally—i.e. in a scene resembling ‘artificial respiration’, ‘mouth to mouth’.)

In reality, of course, he was working within the conventions of an ancient visual tradition; and the best way to assess his artistic ‘creativity’ will be to compare his solution with two earlier interpretations of the scene, taken from the recent, Florentine past.

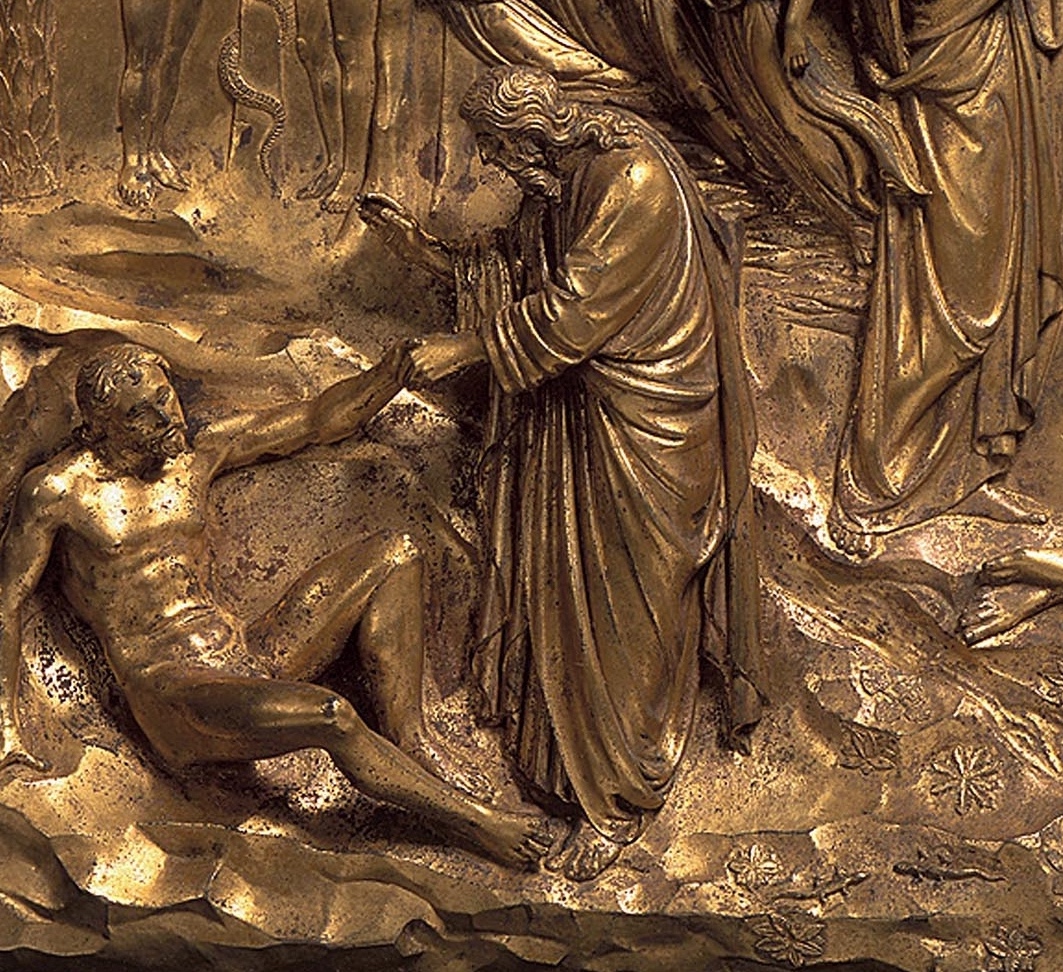

In the tiny detail from the first panel of the Gate of Paradise, God is standing on the ground before Adam, his right arm raised in benediction, his left hand firmly grasping Adam’s languid left hand, ready to lift him to his feet (so that he will walk ‘upright’ and ‘uprightly in the ways of the Lord’).

In the same period (c. 1420–25), Paolo Uccello adopts virtually the same iconography in the Florentine church of Santa Maria Novella. Like Michelangelo, he is painting in fresco and like Michelangelo he is vigorously sculpturesque. His God is more dynamic than Ghiberti’s (he is not standing but stepping forward, his left foot raised as his weight comes down on the right). But Adam’s pose is almost identical in the reversed composition.

So what does Michelangelo keep from tradition, and what does he modify?

He retains Adam’s traditional pose (seated on the ground with one knee flexed). But he also finds inspiration in classical sculpture—specifically, in a typical Roman statue of a river god. Look closely at the two images here, and take note of the reclining posture, the placing of the right elbow and relaxed hand, the twist to the torso (bringing it parallel to the plane of the picture), the left elbow resting on the knee.

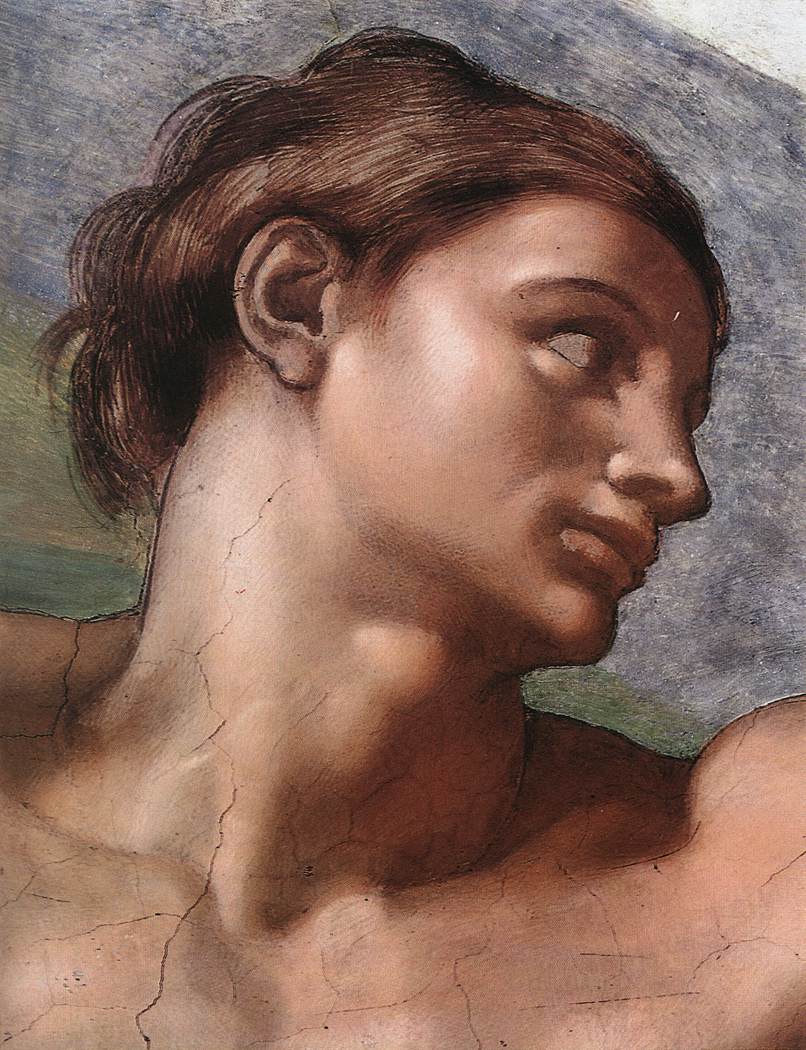

He also makes his Adam as beautiful and as virile as he can (for, as you may remember from the previous lecture, not all his nudes are beautiful, and not all his beautiful nudes are virile).

Adam’s head, in particular, with his wide-open, innocent eye (reminiscent of Mary in the Doni Tondo), is worthy of the claim made in the first chapter of Genesis that God created Man ‘in his likeness and image’: creavit Deus hominem ad imaginem suam, ad imaginem Dei creavit illum (1:27).

Most important of all, Michelangelo replaces the standing or walking Jehovah (found in Ghiberti and Uccello) with yet another version of his flying Jehovah, making him hurtle in horizontally from the right, like a classical sky god, his bare arm extended beyond the red mass of his robe (packed with angels), the sense of direction and speed being intensified by the fluttering ribbon and by the supporting angel, flying under the robe.

The ‘shutter’ on Michelangelo’s metaphorical ‘camera’ has captured the instant immediately before the two hands touch—one alert, progenitive, the other relaxed, receiving, open.

A moment later, the surfaces will come into contact, the ‘circuit’ will be complete, the ‘current’ will flow, and Adam will become—as Genesis has it—a ‘living soul’, a human, a creature with a mind.

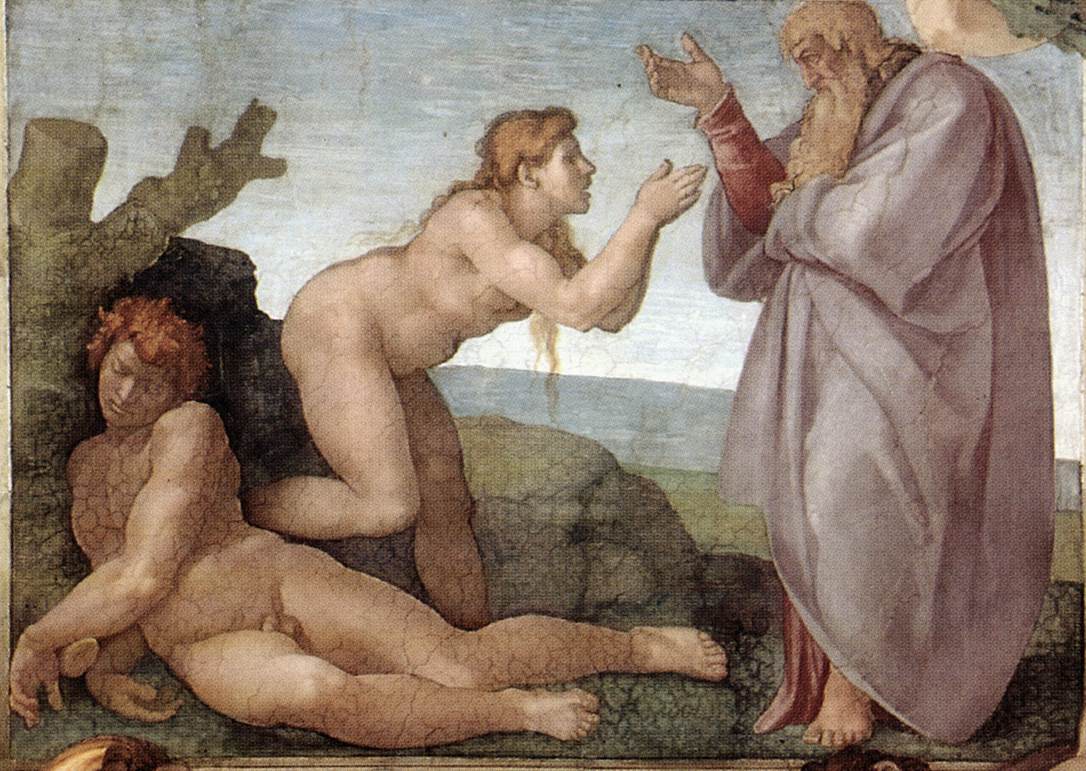

The next scene shows how ‘the Lord God built (aedificavit) a rib taken from Adam’s side into a woman’. (In this case the artist cannot avoid directly illustrating the words of the Bible: ‘aedificavit Dominus Deus costam quam tulerat de Adam in mulierem’ (2:22).)

I am deliberately placing the scene in its immediate visual context to emphasise a point made in the previous lecture, namely, that you should not try and look at the narratives from the same position and at the same time as you look at the ignudi—and, more important, to remind you that the scene is very much smaller than its predecessor.

The enlargement here should come as a stylistic shock, because the Creation of Adam was painted when Michelangelo resumed work on the ceiling after an interval of several months, whereas the Creation of Eve belongs very much with the frescos of the first phase. (Apart from the change of scale, Adam’s face is not even remotely related to the one we have just studied).

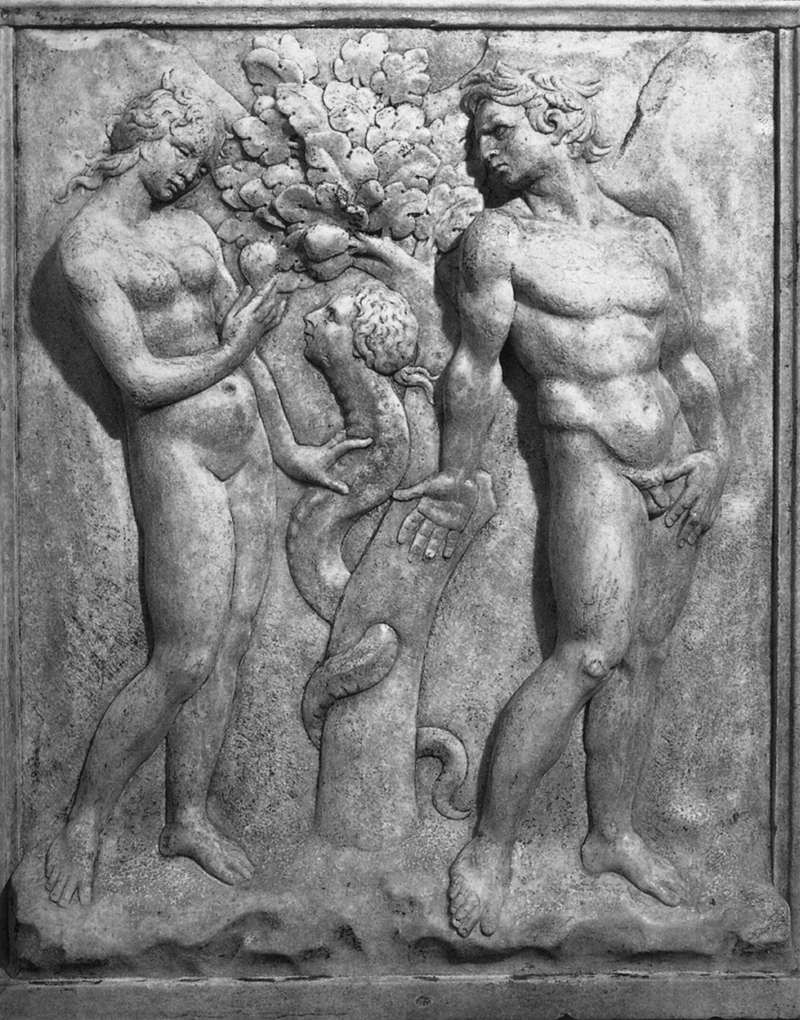

Michelangelo keeps much closer here to the models provided by relief sculptures from the early fifteenth century, as you can confirm from the small panel by a Sienese sculptor, Jacopo della Quercia (dating from c. 1425, on the façade of the church of St Petronio in Bologna, where Michelangelo had been working just before he came to Rome for the third time).

You can see the compositional debt immediately. In both cases, God is standing, bare-footed, in profile, while his right hand draws the ‘woman’ from the rib of the sleeping Adam, who is semi-recumbent, with his left arm swung across his body.

You can also see the differences. There is no physical contact between God and Eve in Michelangelo. Her body is well-rounded, and she crouches awkwardly in adoration (while Jacopo’s is slender, modest, graceful and beautiful).

In the marble relief, Adam is treated almost like a rag-doll; while in the fresco, his body is indebted to statues from classical Rome. In Jacopo, God’s mantle is an agitated mass of curvilinear folds, expressive, but mostly unmotivated—pure ‘International Gothic’. Michelangelo’s heavy woollen garment, by contrast, hangs with something of the massive simplicity we associate with the art of Giotto in Padua, 125 years before Jacopo’s time.

On now to the second larger-sized scene in the central triad—the scene ‘Of Man’s First Disobedience and the Fruit / of that Forbidden Tree’:

Once again, the ground, sky and rocks are as schematic as they would be in a relief sculpture. The Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil is given extensive but simplified foliage in the form of gigantic fig leaves. It has a robust trunk, around which there coils (as was traditional) the serpentine body of the Tempter—who has a woman’s thighs, breasts and head.

The two figures on the left are superbly characterised and contrasted. Adam is powerful and thick set. He stretches up decisively, grasping the branch, to pick the fruit for himself; while Eve reaches up more languorously (despite the masculine arm), seeking eye contact with the Tempter and accepting the fruit from his outstretched hand.

(A brief glance at the corresponding panel by Della Quercia will help to evaluate Michelangelo’s originality. In the wonderful earlier version, both our parents are standing; Adam warns and remonstrates on the other side of the tree; while Eve restrains the ardent Satan, and takes the fruit for herself).

On the other side of the fresco, retribution follows immediately, as the Cherub expels our Parents from the Garden of Eden at sword point.

Notice how Adam goes under protest, but with some residual dignity; while Eve cowers, unseductive now, haggard and ugly.

The scene is undeniably powerful; but many people have felt that Michelangelo falls short of the understated despair that Masaccio had caught in his even more famous imagining of the Expulsion (again, in Florence, back in the 1420s).

The composition of the whole fresco, on the other hand, is superb. Enjoy the central placing of the tree, the balancing of the two figure-groups, and above all the rhythm of the arms—reaching, offering, accepting, pushing, demurring and thrusting forth.

Michelangelo is apparently unprecedented in uniting the two scenes in one frame; and there is little doubt that he intended to suggest the form of the Cross—the Cross, on which Adam’s sin would be punished and expiated; the Cross, which legend said was fashioned from a tree that grew from a seed of this same Tree of Knowledge.

(If you are intrigued, you will find a whole lecture on the Legend of the True Cross (as painted by Agnolo Gaddi and Piero della Francesca) in the series devoted to Florence.)

We are about to leave the story of Adam and Eve in order to examine the final group of three narratives on the ceiling (once again, in a sequence of small, large, small), which deal with the story of Noah.

It is therefore a good moment to offer you the chance of a little revision concerning the design of the Ceiling as a whole.

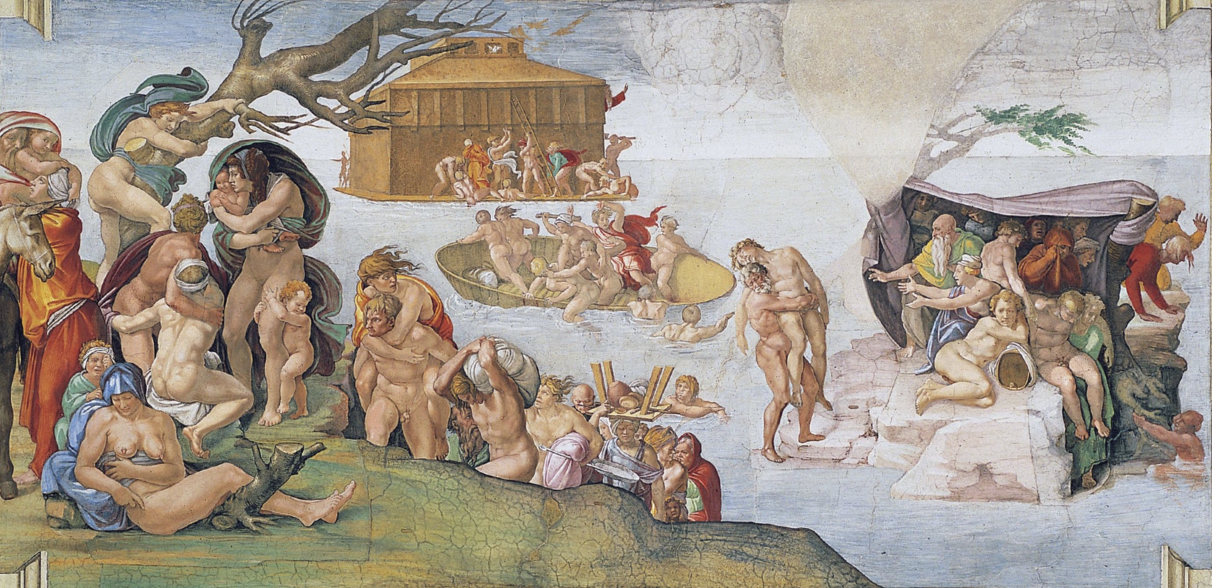

The story of Noah is one of a second divine punishment, but a punishment with a difference: among the whole of mankind, a single family is to be ‘saved’ from destruction in the Universal Flood by finding refuge in the Ark, a vessel that was regularly interpreted as a prefiguration of the Christian Church.

It is impossible to make sense of the narrative unless we follow the sequence of events as told in the Bible, so we must begin with the largest of the three scenes, which illustrates chapters six and seven of Genesis and deals with the Flood.

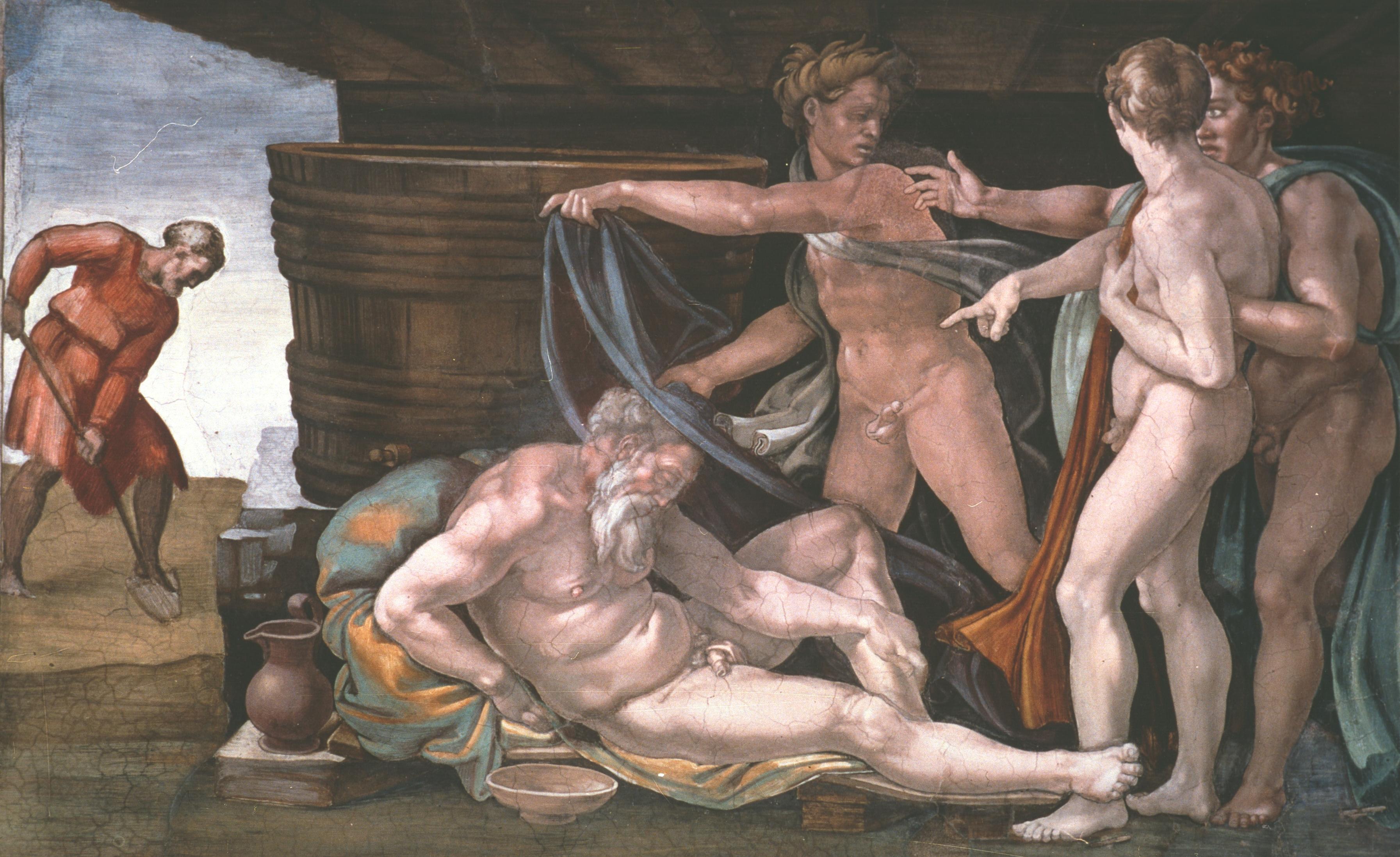

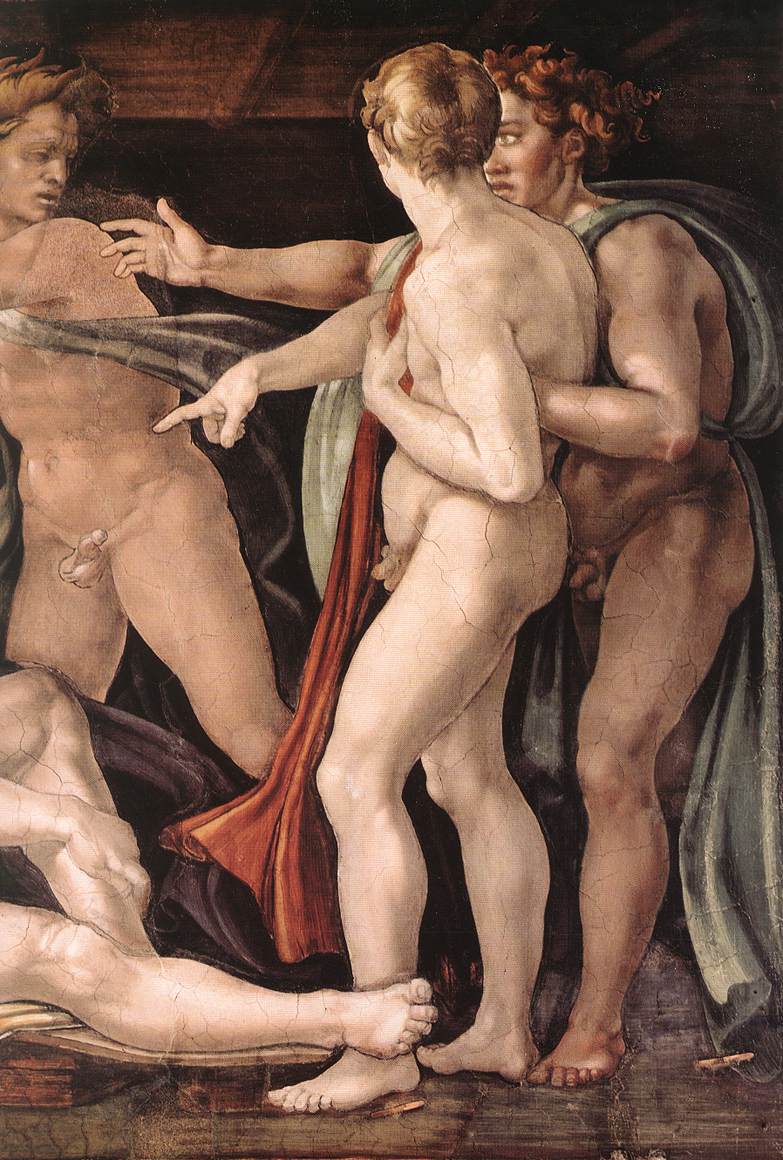

(The two smaller scenes are less familiar today, but they were clearly an important part of the story for interpreters in the fifteenth century; and all three episodes in the Sistine Chapel had been represented in a single panel by Ghiberti on the Gate of Paradise. The Ark is shown as the pyramid in the centre; Noah’s Sacrifice is on the right; and the so called Drunkenness of Noah is on the left).

With one exception (Noah, whose arm and profile are barely visible), everyone you see in this fresco is doomed.

Those who are predestined to be saved are already inside the Ark, which floats safely on the waves, just as the Church (which it prefigures) will survive the advance of Islam and the Protestant challenge.

The doomed react in different ways, as human beings always will in the face of disaster.

Some try to force their way onto and into the Ark; others try and scramble aboard another smaller craft which is totally unable to carry them to salvation.

(It would not be difficult to allegorise this, but concentrate instead on the fear and violence shown by those who want to save their own skin at any price and are prepared to ‘repel boarders’).

On the moss-covered mound in the left foreground, others have become refugees, carrying their belongings up the hill from the waters, sheltering the children from the wind, or trying to climb a tree. And yet, all these people too are doomed to damnation. They will not find the promised land. Mankind will not find ‘safety’ until another Man (a Second Adam) climbs upon another, very different tree.

(It seems almost inappropriate to add the comment that the expressive backs of the three ascending male nudes are as fine a sculptural group as Michelangelo never got round to carving…).

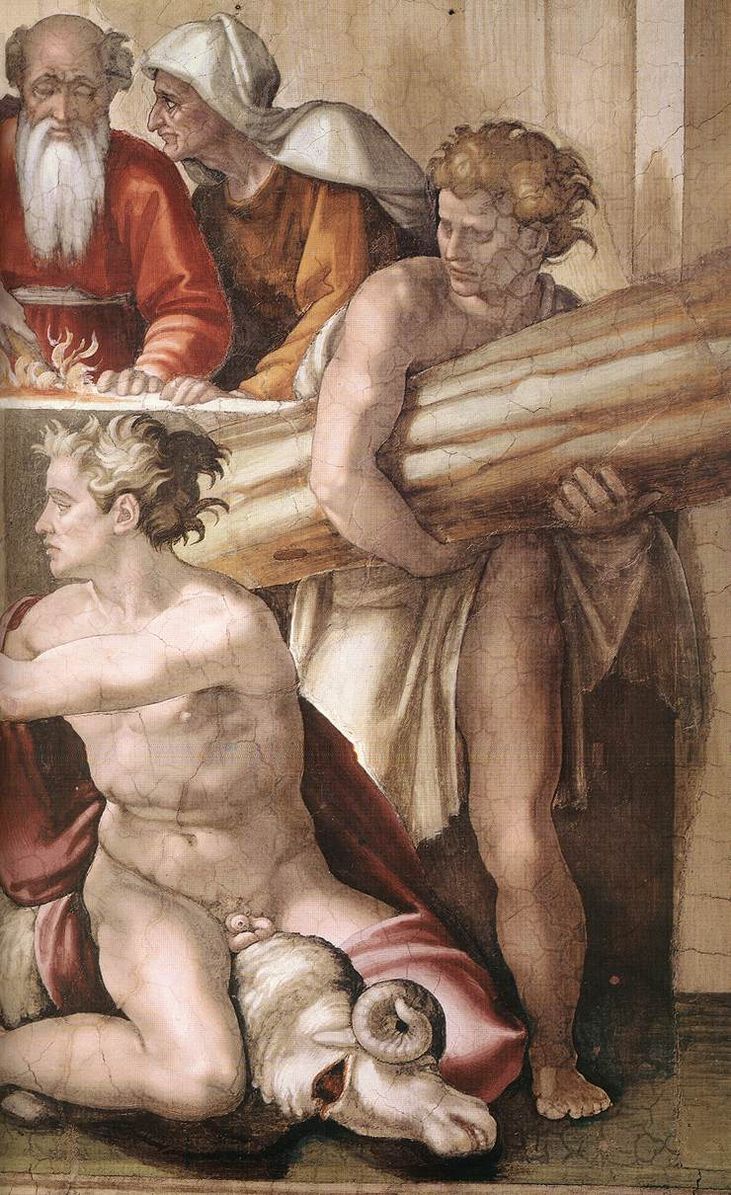

The first of the smaller scenes is somewhat less familiar.

It is taken from the eighth chapter in Genesis (8:16–19), after Noah had ‘gone forth from the Ark, and his sons and his wife and his sons’ wives with him, and every beast…and every bird…’.

Noah, we read, ‘built an altar to the Lord and took of every clean animal…and offered burnt offerings on the altar’ (8:20).

For the theologians, it constituted an important stage in the chain of events preparing the way for the Atonement.

On the left of the scene, which is composed very much like a low-relief sculpture, you can see ‘clean-living’ horses and an ox waiting their turn.

On the right, a sturdy son brings up a ram to share the fate of its companion, whose throat has already been cut. Another sturdy youth brings on a bundle of staffs to feed the fire, while behind the altar Noah and his wife look at the flames ascending and point to the sky, where we know that ‘God set a rainbow in the cloud’ (9:13–17) as the sign of a covenant with Noah and his descendants—a covenant (described at great length in chapter nine of Genesis), that ‘never again shall there be a flood to destroy the earth’.

It is not yet a promise to redeem mankind. But Noah’s ‘acceptable sacrifice’ has led, at least, to a promise not to wipe us out utterly.

The final episode is narrated in the second half of chapter 9 and occurs immediately after the Sacrifice.

It tells of divisions between brothers, of conflicts to come, and of a divine retribution (which Pope Julius may have welcomed as a prefiguration of the fate awaiting those who denied proper respect to the Pontiff).

In Genesis 9:20, we read that ‘Noah was the first tiller of the soil. He planted a vineyard; and he drank of the wine; and he became drunk and lay uncovered in his tent.’ (The point of the story is that Noah exposed his genitals, as you can plainly see.)

(It is interesting to note in passing that Michelangelo follows Ghiberti’s panel very closely here in his depiction of the beamed roof of the hut, the huge vat of wine, and the jug, and also in the ‘river god’ pose of Noah, who has been overpowered by wine.)

To return to the text of Genesis: ‘Ham saw the nakedness of his father, and told his two brothers outside’ (9:22).

By doing so, he had clearly broken a taboo, because ‘Shem and Japeth took a garment, laid it upon both their shoulders, and walked backward and covered the nakedness of their father; their faces were turned away, and they did not see their father’s nakedness’ (9:23).

The upshot (9:24–27) was that Noah laid a curse on Ham and his descendants—a curse which would be used as an excuse by the European descendants of Japeth to indulge in the slave trade of Africans well into the nineteenth century.

At this point, we must recapitulate the argument of the whole Chapel and the relationship between the nine narratives we have just examined and the fourteen Old Testament scenes on the rest of the ceiling, not to mention the stories of Moses and Jesus on the walls.

Michelangelo’s first six episodes (from the Creation to the Fall) were essential to the ‘plot’ in that they described the ‘crime’, that has to be not so much ‘solved’ as ‘expiated’ by the end of the story.

The three relating to Noah are, in a sense, a repetition of the original crime and its punishment. But they also point forward to the solution.

The salvation of Noah and his family, and God’s covenant with him, anticipates the giving of the Written Law to the Jews under Moses, which, in turn, prepares for the giving of the Evangelical Law to all mankind through Jesus.

There is a similar relationship of ‘bad news’ and ‘good news’ between the other two groups of Old Testament stories painted by Michelangelo.

The scenes in the ten medallions—supported, you remember, by the nudes, seated above the thrones are drawn from the historical books that make up the first half of the Old Testament.

They illustrate further ‘Falls’, in the shape of specific infractions of each of the Ten Commandments, which lie at the heart of the Written Law.

Each act of defiance or disobedience was duly punished by Moses’ successors in the office of High Priest, in much the same way that Moses crushed the rebellion of Korah.

Hence these much neglected medallions are very much part of the papal message addressed to the proto-Protestants in the North of Europe; and it is not without relevance that the prophet Nathan (who rebukes the kneeling King David in the lower image) is dressed like a pope in full pontificals.

The medallions, to put it another way, offer a significant selection of the ‘bad news’; and they exemplify the innumerable ‘backslidings’ of the chosen people, which in turn occasion the innumerable lamentations and exhortations of the Hebrew prophets, whose writings make up most of the second half of the Old Testament, and who are represented on the thrones below the medallions, as we saw in the previous lecture.

The ‘good news’, on the other hand, is to be found in the message of hope in the Messiah, whose coming was foretold by those prophets.

The same message of hope was believed to be encoded in the very history of the Jews, who survived and triumphed against all the odds—first in the Wilderness, then in the wars against the indigenous peoples of the Promised Land, and then in the time of the invasions by the Assyrians and Persians, and their subsequent deportation to Babylon.

The four corner spandrels illustrate four of the most famous of these triumphs, in which victory was clearly due to the Lord’s intervention, because the human instrument of deliverance was so manifestly weak.

Since we have followed Michelangelo’s nine narratives from the west wall to the east, let us turn round to face that wall and look up into the left corner.

In this case, the human vehicle of deliverance is a woman, a beautiful widow called Judith, who made her way to the camp of the Assyrian general, Holofernes, won his confidence, got him drunk, and, instead of letting herself be seduced, cut off his head with his own sword.

If you ‘read’ the figures from right to left in the inverted triangle, you will see the decapitated corpse of Holofernes, sprawled on the bed, with right leg and left arm hanging over the side.

The maidservant crouches like a caryatid (a female telamon) under a tray supporting the gigantic head. Judith twists, in a superb rear view, glancing back at the corpse, as she prepares to cover the head with the cloth and make her escape with it beyond the sleeping guard.

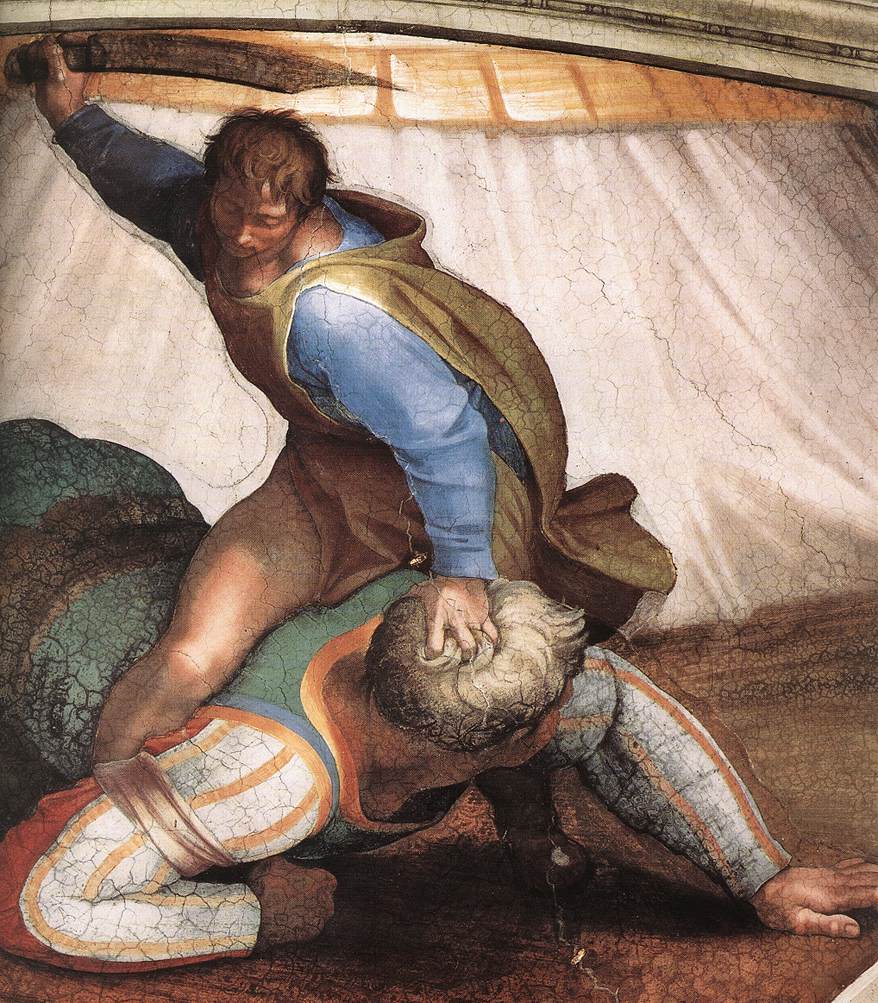

The theme of a decapitated enemy, whose gigantic head will be carried in triumph, provides a thematic link to the scene in the right corner of the entry wall which comes much earlier in the Bible.

Here the enemy is one of the ‘invaded’ rather than an ‘invader’, and the hero is not a woman, but a mere stripling.

David has stunned Goliath with stones from his sling (which is lying in the foreground). He now stands astride the half-recovered giant (who looks rather like a huge turtle), and is about to use his victim’s own scimitar to cut off his head.

The two figures form an upright triangle, which somehow fits into the inverted triangle of the spandrel itself; and a supernatural light shines from above (look at David’s thigh and Goliath’s head in the detail) to illuminate the brilliant colours of the sleeves.

We must now walk right down the chapel back to the Altar Wall, where we find, in the corner spandrel on our left the story of the deliverance of the Jews at the time of their second ‘exile’—deliverance from a plot, hatched by Haman, chief minister of the Persian king, to have them all massacred.

There is no time to tell the long story of the two scenes shown in the background, or of the courage shown by the Jewish queen, Esther—a recognised ‘type’ of Mary—in pleading the cause of her own people. Nor is there time to tell how Haman was hanged on the very tree he had prepared for the Queen’s guardian, Mordecai (who sat at the gate of the palace, and refused to do him reverence).

Notice, however, that whereas the Bible speaks of hanging, on a gallows, Michelangelo shows us a crucifixion, on a St Andrew’s cross, itself placed on a diagonal, so that Haman seems to spring out at us (the pose deriving once again from Laocoön’s struggle with the serpents). The main conceptual point, though, is that Esther, the instrument of salvation, was a ‘mere’ woman, and that the Virgin Mary was also a ‘mere’ woman.

The idea of ‘crucifixion’ and a common debt to the Laocoön link the story of Haman to the fourth corner-spandrel—the last to be painted, but the earliest in the Bible story, since it concerns the Israelites in the Wilderness, while they were still under the rule of Moses.

Discontent and rebelliousness have been punished by a plague of serpents who (as in the Laocoön group) coil round the victims, while the victims themselves are writhing into the most extraordinary contortions, in what is probably Michelangelo’s single most complex, and single most influential composition.

Deliverance, in this case, came when God told Moses to set up a brazen image of a serpent on a pole (which you see close to the centre and top of the spandrel).

(You will recognise the visual allusions, first to Satan, coiled round the Tree of Knowledge, and second to the Cross, of which the Brazen Serpent was a well-known ‘prefiguration’ or ‘type’.)

The point of the story is that all those who turned to gaze at the brazen serpent (as shown in the lower detail) were cured of their snake bites, that is, of the spiritual poison left by the ‘Adversary’, Satan.

From the four isolated narratives in the corner spandrels, which prefigure Jesus’ triumph over sin on the Cross, we now come to the non-narrative but strictly sequential and unbroken chain of human causes, which connect Abraham—the patriarch whose story is told in the Bible immediately after that of Noah—with Joseph of Nazareth, the carpenter whom Jesus knew as his father.

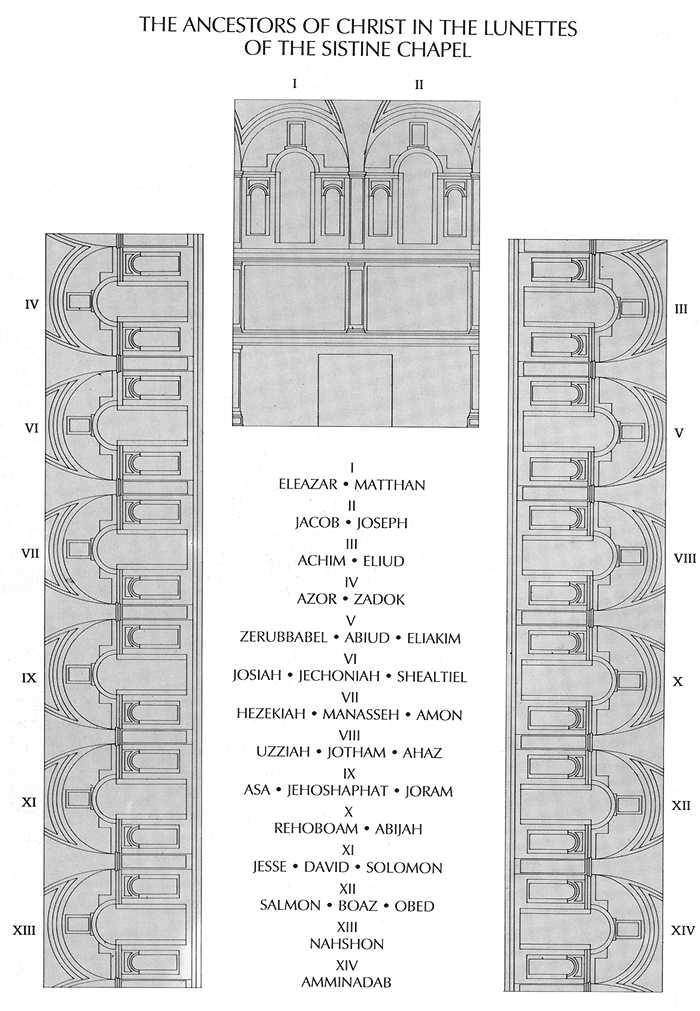

In short, we come to the Table of the Genealogy of Christ—the ‘Ancestors of Christ’, who are represented in the lunettes and triangular spandrels above the windows.

This is a good moment to mention two other important, formal connections between Michelangelo’s scheme and the existing frescos of the 1480s.

You may remember that the popes and the stories of Moses and Jesus are not to be read in sequence along each wall, but ‘antiphonally’, across the chapel, ‘left, right, left, right’.

This is also how you are meant to read the sequence of the Ancestors (as listed in the first chapter of the Gospel according to Saint Matthew).

In other words, to get the sequence of names in the right chronological order, you must keep moving away from the altar (against the order in which Michelangelo actually painted them), and change sides after every window.

Michelangelo also respected his predecessors in that he represents the fall of light consistently in each fresco as though it came from the original windows in the West Wall—from left to right on the North Wall, and from right to left on the South Wall.

The first pair of lunettes was originally above the two windows on the Altar Wall, but the windows were bricked in and the lunettes destroyed by Michelangelo himself, at the time when he came to paint the Last Judgement.

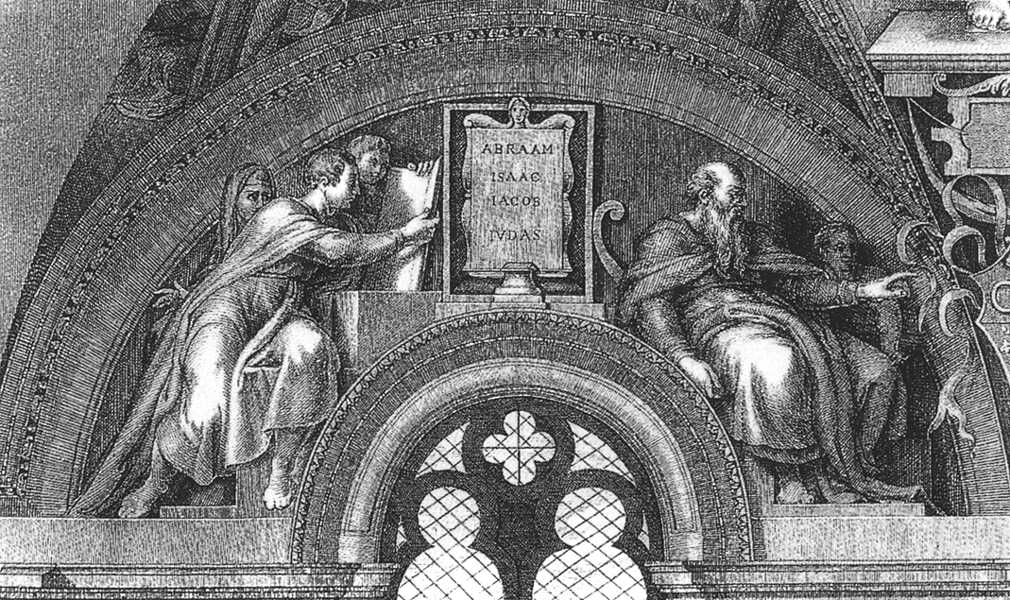

We know, however, from an early engraving that the ‘Book of the Generation of Jesus Christ’ (Liber Generationis Jesu Christi) began in the left lunette with the resonant names of four patriarchs whose deeds occupy so much of the Book of Genesis (Liber Generationis). (Their names are given in the second verse of the Gospel of Matthew: Abraham was placed next to the centre with the infant, Isaac; and to their left, Jacob and Judah.)

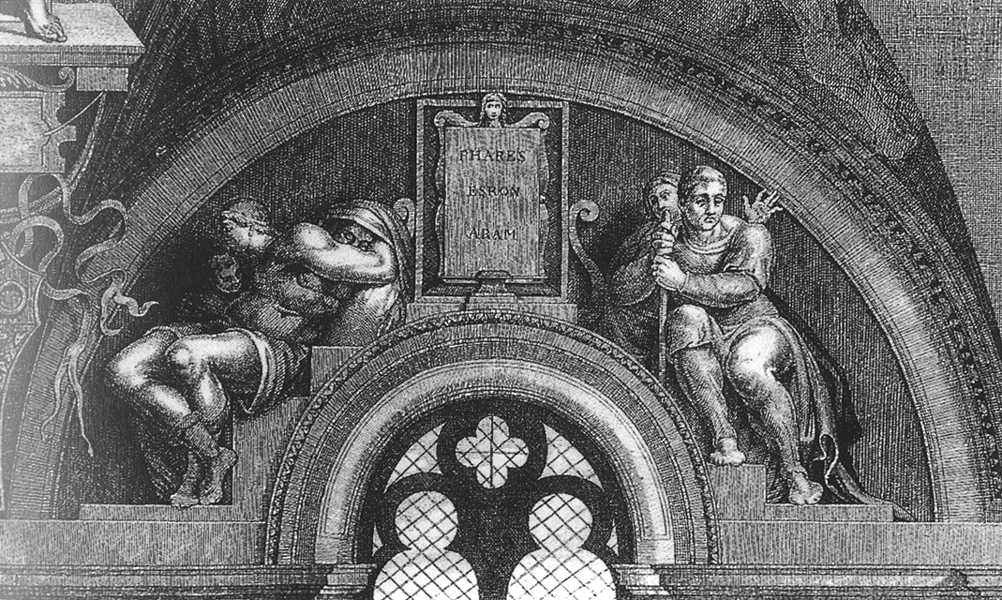

The right lunette on the same wall represented the three totally unresonant names given in verse three.

I will not offer any comments on these engravings, but merely ask you to keep in mind the characterisation and the position of Abraham—who is shown near the middle of the wall, seated, facing the centre, bearded and balding.

The first surviving lunette is on the South wall (the ‘Moses wall’), on your left as you face the altar.

Here we see one of the two ancestors named in verse four, Aminadab. (His shadow is clearly indicated as being cast to the left by the imagined source of light in the altar window to the right.)

Aminadab sits, wearing earrings and some saucy headgear, dressed in a coat of many colours, looking out at us as though he were trying to suppress the thoughts of ‘generation’ aroused by his lady. (After the cleaning in the 1980s, she became almost as seductive in colour as she always had been in her pose. Look at the way she holds her heavy, blonde hair away from her with her left hand, while combing it with that huge African comb.)

To find his son Nahshon (also named in verse four), we have to cross to the lunette opposite him, on the North wall (which therefore has the imagined source of light as falling from the left, and throwing shadows to the right).

His lady, too, seems to be engaged in self-adornment; and he too seems to be intent on looking the other way. But, as you see, Michelangelo rings the changes. Nahshon is shown in profile, hatless, revealing the curls in his most elaborate coiffure; his coat is much longer and it is scarlet all over; and his yellow-stockinged leg rests on a block, as he tries to keep his mind on his studies.

Even in these two lunettes, with just four figures, you can see how inventive and resourceful Michelangelo could be in filling this almost impossibly awkward shape.

This resourcefulness became even more necessary on the remaining windows on each wall, because the artist now had to squeeze figures not only into the lunettes, but into the spandrels above.

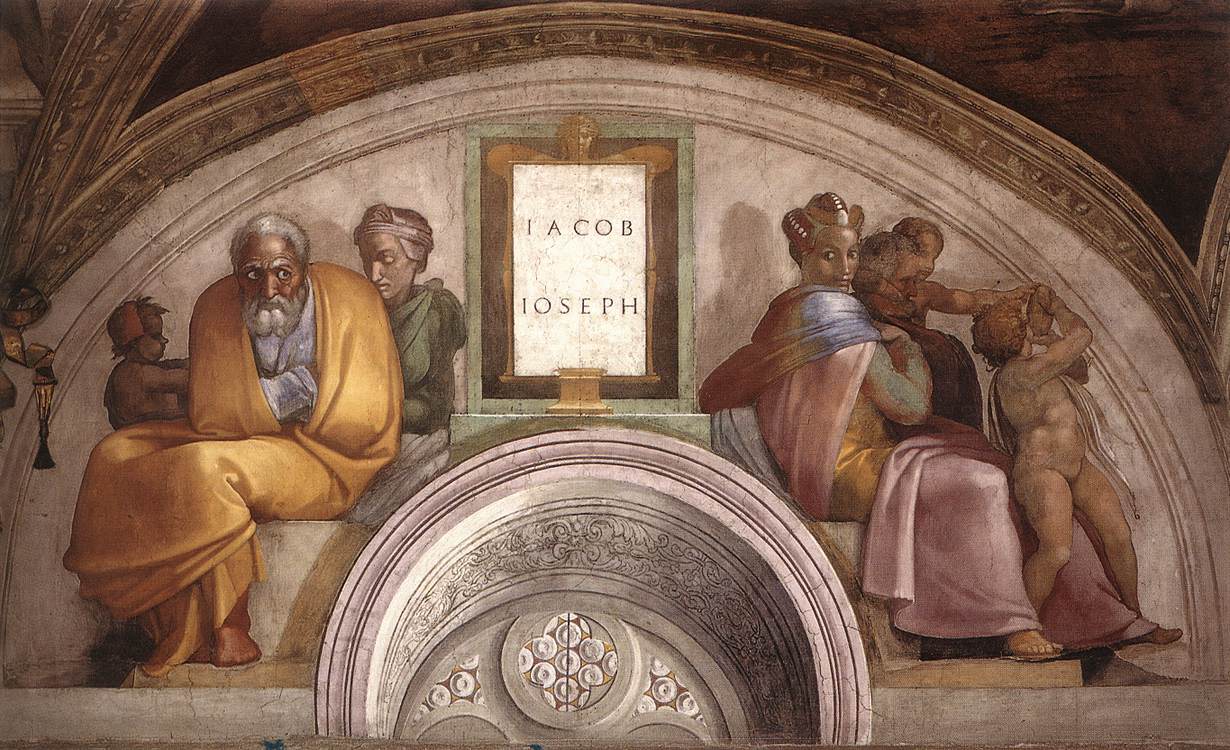

(As noted in the previous lecture, the spandrels are imagined as offering a slightly deeper recess than the lunettes. They always show a mother, seated on the ground with an infant, who is fairly prominent; while the father, if present, is usually relegated to the background; with the result that each group makes us think of the Holy Family resting on the Flight to Egypt.)

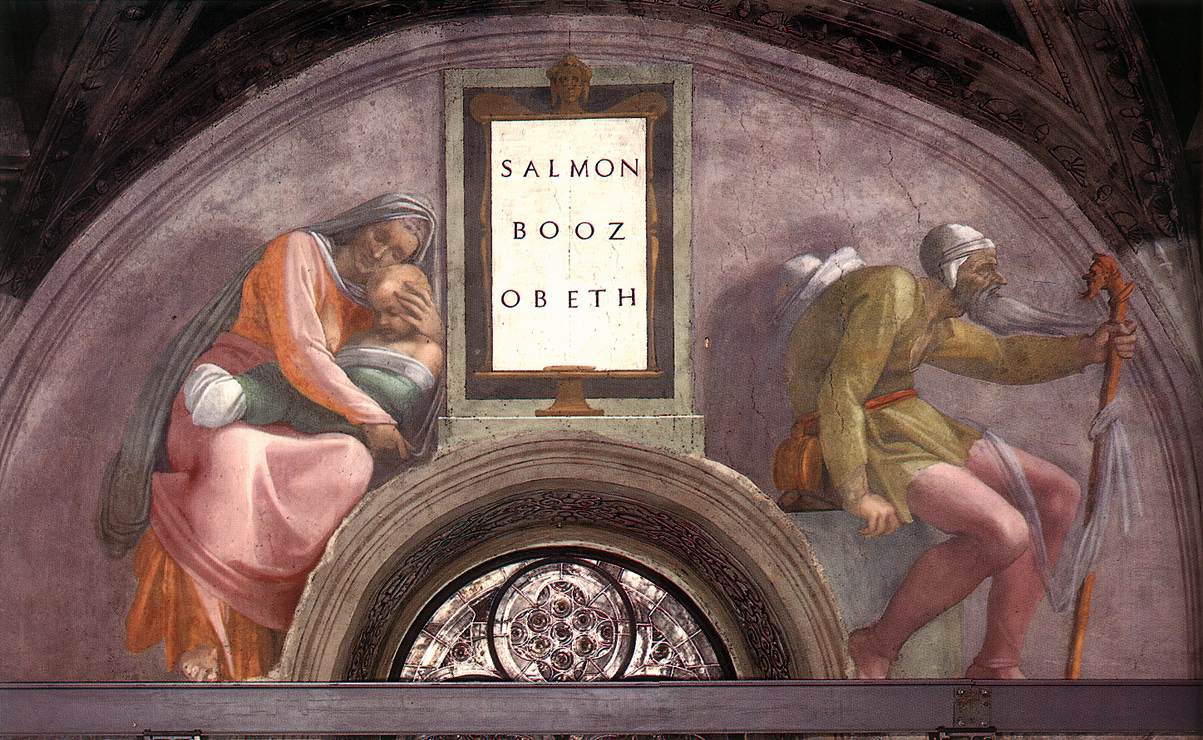

In the first spandrel on the south wall, we find the three male Ancestors named in verse five. The mother is cutting a thread, but seems almost to be getting out the sandwiches, while son and husband peer over her knee and shoulder to see what there is for lunch—the whole intimate scene being transformed into a high Renaissance pyramid of forms, as ‘patented’ by Leonardo, which fits effortlessly into the triangular recess.

The child is Salmon (as you can read in the name plate in the lower image), who is otherwise unknown to fame. But the two characters in the relevant lunette will be known to you from the Book of Ruth (and from poems by John Keats and Victor Hugo): they are Boaz, the aged farmer, and the Moabite, Ruth, who came as an immigrant to glean ‘the alien corn’, and married Boaz, by whom she had a son called Obed.

Ruth is a very loving study as she drifts into sleep, cradling the baby after having given it the breast.

Boaz, by contrast, is treated with affectionate irony. His broad hat is on his back and his water bottle at his waist; his legs are bare; his long beard juts out over his arm, which is gripping his pilgrim’s staff; and the handle of the staff is carved as a caricature of its owner. (Both have also been construed as caricatures of Michelangelo’s patron, Pope Julius II!)

Obed begat Jesse, for whom we have to look quite hard in the next spandrel on the North wall, where he might be the father, or he might be the son.

This is the Jesse whom you may know from medieval representations of the ‘Tree of Jesse’; but since there is no time for what would have to be a long digression on the ‘ancestor par excellence’, we will pass straight on to the next ‘big names’ in the lunette immediately below.

They (as the plaque informs us) are David and Solomon; Solomon being the son that David begat on the wife of Uriah the Hittite, having first arranged for her husband to be sent into the front line to be killed: in other words, the mother is none other than Bathsheba. Michelangelo presents her as David’s wife (as she eventually became), no longer young, and virtuously spinning to remind us that she had been the totally innocent party in David’s adulterous plan.

David himself (for he it must be on the left) seems to ignore his latest son at his side, lost in the feelings of remorse that found expression in the Penitential Psalms (specifically in Psalm 51, written, according to the rubric, ‘after he had gone into Bathsheba’). Or perhaps he is already lamenting the death in battle of ‘Absalom—my son, my son’.

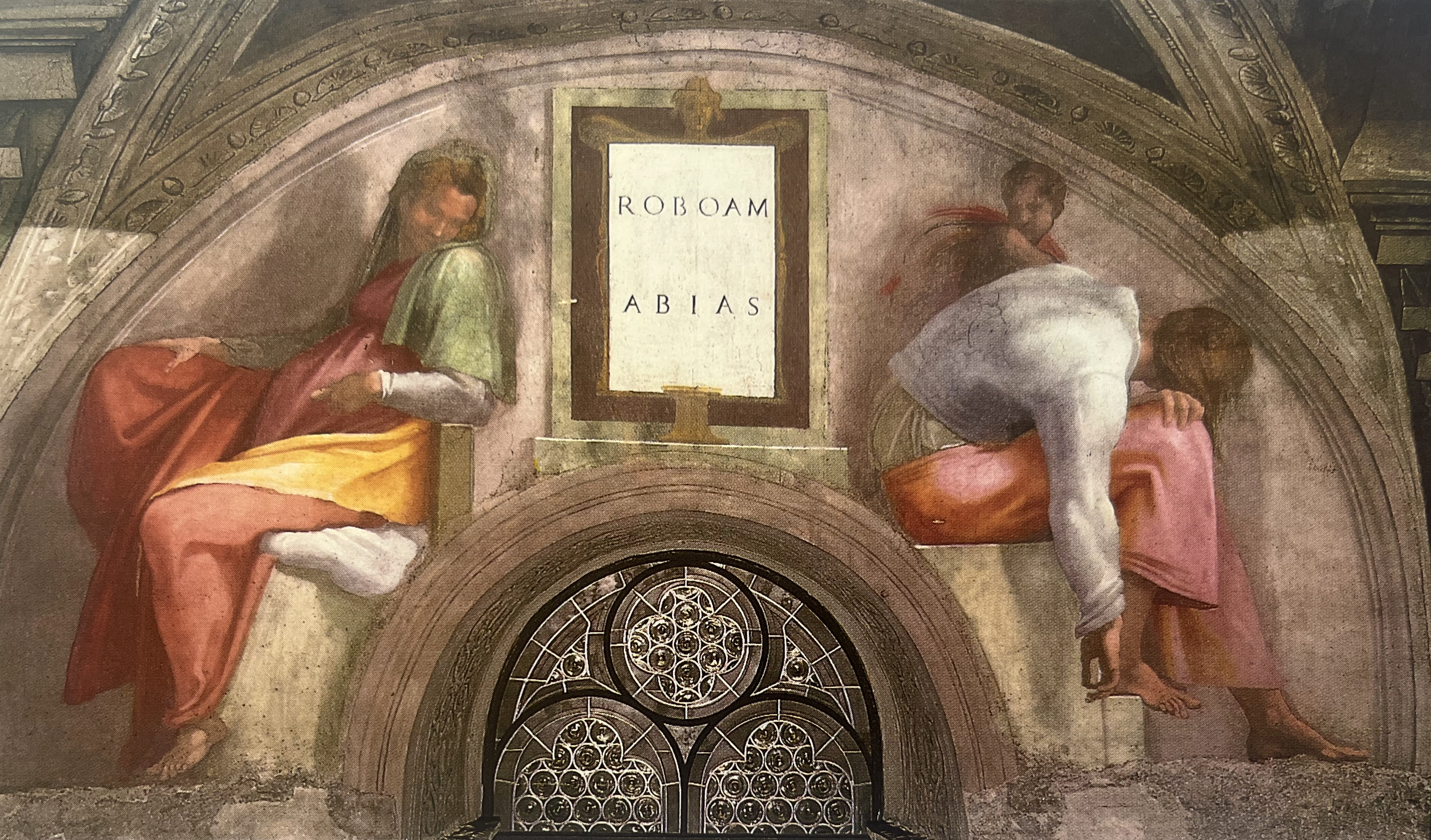

The next spandrel (on the opposite wall) is dedicated to Solomon’s reprobate son, Rehoboam, and to his son, Abijah, of whom we know nothing but the name (we have now reached verse seven).

The answer to the question ‘Who is who?’ in the lunette (one of the most pleasing of the whole sequence) remains unclear. The exhausted mother-to-be (her pose suggests that she is seven months pregnant) has nodded off with her head against the wall and her elbow resting on the ledge. The father (notice the trousers) has been completely overpowered by sleep. His head on his knee, his face is turned away, his arm hangs limply; and he is unrouseable by the child, who is very like one of the genii whom we find accompanying the prophets and sibyls.

We return once more to the North wall, where the spandrel is again dominated by a mother crouching in profile—this time deeply asleep.

She is the mother of Asa, who, as we learn in verse eight, was the father of Jehoshaphat (whom I take to be the figure on the left).

He is lean, with a hooked nose, pointed chin, and prominent Adam’s apple. He is wearing ‘tracksuit trousers’, elasticated at the ankle over his ‘trainers’; and he is making careful, legal notes on his knee—his name means ‘God is judge’—under the splendid shot silk of his cloak.

Jehoshaphat was the father of Joram, who is presumably the eldest of the three children, the one standing on the right, rather than the one with fair hair (who seems rather old to be taking the breast) or the exuberant baby, who flings himself horizontally to hug his mother round the neck. (Well may she close her eyes in exhaustion!)

You have now seen all the Ancestors in the western half of the Chapel (frescoed by Michelangelo in the second phase) and you know in what spirit to approach them, and how much there is to enjoy. Every fresco has an element of spontaneity and unpredictability. (One of the many discoveries made during the cleaning process of the 1980s was that Michelangelo painted each lunette in just three days, working without cartoons, directly on the wet plaster, defining everything by brushwork and colour.)

No one, it seems, had ever painted all forty-two generations before Michelangelo, just as no composer had ever composed a setting of the whole text before Josquin des Près in his motet for four voices, Liber generationis.

Josquin held a post in the Vatican choir during this period; and I have dedicated a whole lecture to the achievement of these two giants, which will appear in a separate series on this site in 2026. It will end with a performance of the motet synchronised with the illustrations: Son et Lumière with a vengeance!

I make no apology therefore for omitting the next fourteen generations (who appear on the side walls at the eastern end) and bringing our survey to an end with a brief glance at the pair of lunettes over the entrance.

Here they are, side by side, exactly as you see them in the chapel, with the cast shadows meeting in the centre of the wall.

This is the fifteenth lunette in the cycle, and we have reached verse fifteen in Matthew’s Gospel, which names the great-grandfather and grandfather of Joseph as Eleazar and Matthan.

There are two complete families here.

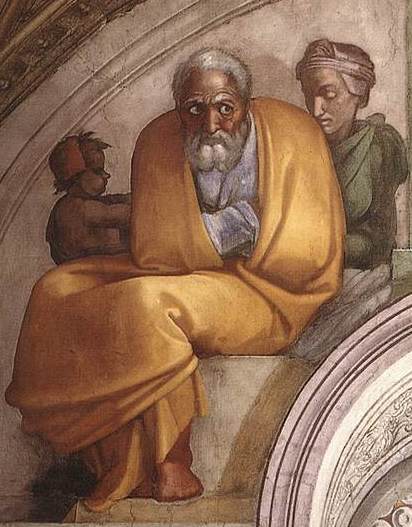

To the left, the baby is being bounced on his mother’s knee, kicking back her skirt to reveal its lining, and exposing her white petticoat and purple stocking. The dark-skinned, short-haired father is relegated to the background, from where he looks on in alarm.

On the right, dominating the foreground, the father is younger, fair-skinned, blonde—and something of a poseur.

His self-conscious profile and his raised arm and leg resemble those of a classical river-god; but there is a rather unclassical ‘sweet disorder in his dress’. His red robe falls from his shoulder to expose the white, square-necked chemise (with a long tail emerging negligently between his legs); and his right leg is held in position across the other knee to reveal the brilliant colours of his shot-silk hose.

There are two complete families in the final lunette as well; and once again, the family on the outside is dominated by the mother.

She is a young and decidedly ‘dusky’ daughter of Jerusalem, with the boldest taste in colours—yellow, olive, pink, and blue—most wonderfully highlighted by Michelangelo.

On the other side of the tablet with the names, we find Joseph of Nazareth (who is placed exactly opposite, and in line of sight with, the first of the Ancestors, Abraham, where he used to sit at the other end of the chapel, over the altar).

He is anxious-looking, warmly-dressed, huddled, his arms concealed beneath the robe, and—more important—he is wearing the traditional colours of blue and yellow that identify him in countless Nativity scenes in Christian Art.

QED.