Michelangelo: The Prophets and Sibyls

This labour’s making me deformed and bloat

Like a distended, goitre Lombard cat

(Or one in any country, come to that),

Hoisting my belly up beneath my throat.My beard waves in the air; my memory’s case,

The skull, rests on my nape; so like a thrush,

I go puff-breasted, with my well-filled brush

Dribbling a rich mosaic on my face.My kidneys in my belly now reside,

The arse is clenched to act as counterweight,

My feet move sightless, shuffling to and fro.

In front there is a tautening of my hide

Which gathers loose behind, such is my state—

Pulled head to heel, strung like a Syrian bow.

(Translation by Richard Andrews of a sonnet by Michelangelo)

This lecture is the first of three devoted to the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel; its main subject is therefore the revolutionary art of Michelangelo.

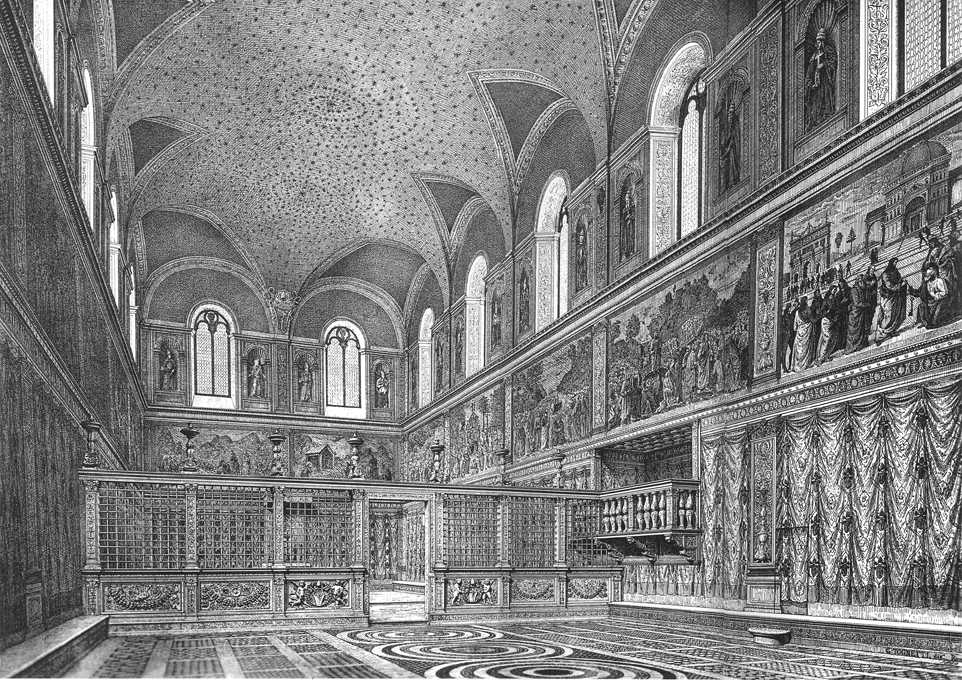

(The upper part of this photograph gives a good idea of the relationship of the vault to the biblical narratives from the 1480s on the south wall at the point reached at the end of the previous lecture.)

We will proceed sedately, however—beginning with a substantial discussion of the general design of this vast expanse of more than 8,000 square feet of painted plaster (more than 750 square metres) preceded by a quick glance at a few of the main achievements in Michelangelo’s earlier career.

And before we get properly started, I would like to throw in a few words about the medium of fresco and emphasise one essential fact about the chronology.

It is important to keep in mind that Michelangelo painted the ceiling in two distinct phases. He began in 1508, at the east end, which, in the Sistine Chapel, was the area where the laity assembled; and he unveiled the first half in 1509 or 1510.

It was only after a significant gap (when the pope seems to have run out of money), that he returned to fresco the west end—the altar end in the Sistine Chapel—working much faster than before, and making the human figures significantly bigger now that he was able to judge their impact at floor level.

The English noun ‘fresco’, I remind you, implies that the artist applied his colours to a freshly plastered area of a wall or ceiling. (The Italian noun is affresco, a nominalisation of the adjectival phrase al fresco.)

The wet plaster would begin to dry out after about six hours, that is, at the end of a normal day’s work; and the size of the area to be plastered and frescoed on any given day varied in accordance with the complexity of the task (one can paint sky quicker than faces or hands).

In order to work with the necessary speed, the outlines of the figures were enlarged from an original drawing (disegno) onto large sheets of heavy paper (not just carta, but cartone, hence ‘cartoon’) so that the figures would be of the desired scale.

The main outlines of the figures in the composition were pricked out with a pin; the cartoon was held against the damp plaster; and coal dust was forced through the pinholes to transfer the lines onto the surface.

Clearly, both the transfer from the cartoon and the application of the pigments had to be done from a temporary scaffolding (probably more precarious than the one used by the restorer in the photograph).

Hence work on a ceiling (not just a wall) was particularly uncomfortable; and work on a vault as high and as wide as that of the Sistine Chapel was not only arduous but dangerous.

We can empathise with these conditions thanks to Michelangelo’s own sonnet on the subject (which I placed without comment on the title page) and thanks to the lightning sketch of himself at work, which he drew in the margin of the manuscript.

(The brilliant translation by my friend and colleague Professor Richard Andrews captures a great deal of the expressively colloquial—not to say vulgar—style of the Italian.)

As you can read again at your convenience, Michelangelo laments that his belly is in his throat, his beard jutting up to the sky, the paint dribbling into his face, and his skin stretched in front and wrinkled behind. He also complains (in a three-line coda to the sonnet, addressed to a friend whom he invites to ‘defend his honour’) that his painting is ‘dead’, partly because he is not in a ‘good place’, and partly because he was ‘no painter’ anyway:

La mia pittura morta

difendi ormai, Giovanni, e ’l mio onore,

non sendo in loco bon, né io pittore.

One of the signs, incidentally, that he was not a professional painter (like Perugino, Botticelli, Rosselli, Ghirlandaio and Signorelli) is that he did not work as the head of a full team of apprentices and journeymen. He must have had some assistance (if only in the handling of the cartoons), but he certainly executed all the human figures himself, not just the faces of the most important figures in the foreground, as a professional painter might have done.

Michelangelo was first and foremost a sculptor. More than that: by the time he started work on the ceiling in 1508, he was thirty-three years old and generally recognised as the greatest sculptor of his time.

He was far from an unknown quantity and he was already on his third visit to Rome. Indeed, the story of his life up until that point could be called ‘A Tale of Two Cities’: Florence and Rome.

(The detail from a fresco by Vasari shows Florence in about 1530, while the map of Rome dates from just after Michelangelo’s death.)

It will be worth our while, therefore, to spend a little time thinking about his earlier career, and looking at half a dozen or so of the early works to let you ‘get your eye in’.

I shall be extremely selective and perfectly happy if you retain no more than the general notion that there are two main features which make his contribution to the Sistine Chapel so radically different from that of his predecessors: first, that he was primarily a sculptor, who had been strongly influenced by some recently discovered statues from classical Rome; and second, that he had been greatly stimulated by his rivalry with Leonardo da Vinci.

Michelangelo was born in 1475, the second son of a family that was socially respectable, but a little less well off financially than it had been. His mother died when he was six, and he spent much of the next four, highly impressionable years in the stone-cutting yard next to the family farm, outside Florence, at Settignano (the wife of the owner having been his wet nurse).

When he was ten years old, his father remarried and the family went to live in the city, in the area near Santa Croce. Michelangelo went to a grammar school for three years, until at the age of thirteen he was apprenticed as a painter in the workshop of Domenico Ghirlandaio—who, you remember, was one of the four artists who frescoed the walls in the Sistine Chapel and who at that time was busy on frescos in the Church of Santa Trinita in Florence.

Two years later Lorenzo de’ Medici (the man with dark hair whom you see in this detail from the Santa Trinita fresco) tried to encourage the art of sculpture by making his own private collection available, and letting young men work there under the supervision of a former pupil of Donatello. And so, at the age of fifteen, Michelangelo began to frequent this informal school, where he rapidly made an impression and was admitted to the Medici household.

He spent a great deal of time in that household over the next two years and he came under the direct influence of a very distinguished circle of people. These included not only Lorenzo himself—42 years old, de facto ruler of Florence, and a distinguished vernacular poet—but also the three famous men whom Ghirlandaio painted in another Florentine church: Ficino, the philosopher and translator of Plato (second from left); the humanist and Dante scholar, Cristoforo Landino; and the man whom we now regard as the greatest poet of that age, Angelo Poliziano (facing us, in the centre).

I use this second portrait group as a way of driving home three essential points. Michelangelo was influenced early on by Florentine Platonism. He knew Dante’s Commedia by heart (already a complete education). He himself wrote poetry—good poetry—in various literary genres.

Nevertheless, Michelangelo was first and foremost a cutter of stone, as you can tell from this unfinished marble relief-panel (about twenty inches high), carved when he was just eighteen.

(There is so much that is prophetic of his future development here. Sixteen heads are crowded into the tiny frame. The overlapping bodies—be they centaurs or male nudes—are twisting or crouching as they avoid or inflict violence (two of them are wielding huge stones). The vertebrae and dorsal muscles of Queen Hippodamia (in the centre) are no less expressive than the faces and pectorals.)

Relations with the Medici grew less intimate after the death of Lorenzo in 1492 and under the growing influence of Savonarola, which contributed to the exile of the Medici family early in 1495. However, it was in Florence that Michelangelo carved a sleeping Cupid, now lost, and sold it as a genuine antique to a dealer who sold it on to a Roman cardinal, Raffaele Riario, a nephew of Pope Sixtus.

When Riario discovered the forgery he demanded his money back from the dealer, but was so impressed by the sculpture that he invited Michelangelo to Rome, where he remained from the age of twenty-one to twenty-six, that is, from 1496 to 1501.

In Rome, under Pope Alexander VI (the Borgia pope), the major influence seems to have come from more and better antique sculpture.

Cardinal Riario, his sponsor, was a famous collector; and it is his collection that still forms the core of the Vatican Museum.

Cardinal Giuliano della Rovere, his future patron, owned the famous statue of Apollo (known as the Apollo Belvedere) which had been unearthed on his land in the 1480s; and Michelangelo’s response to this direct influence was a garden statue of Bacchus (carved in 1497) who is as tipsy or ‘bacchic’ as Apollo is ‘apolline’, but no less beautiful in body; and who is supported by a mischievous satyr sinking his teeth into a bunch of grapes, of whom you will see many descendants in the Sistine Chapel.

The next five years (1501–1506) were spent in Florence again, where the puritanical regime, associated with Savonarola, had been replaced by a more moderate but still anti-Medici republican party.

It was they who, in effect, commissioned Michelangelo to execute a colossal statue, eighteen feet high, to stand outside the seat of government and to symbolise the values of true republicanism which had now been restored.

His response was, of course, David (completed in 1504), perhaps the most famous heroic male nude in the world.

However, the most important stimulus to his development in this period came not from politics, but from intense rivalry with Leonardo da Vinci.

Leonardo had returned to Florence in 1500, at the age of forty nine, after eighteen years away in Milan; and he was amazing the Florentine public with his new figure groupings, which combined extremely complex poses for the individual figures with a greater and more subtle unity of composition.

You can see something of this in his two attempts to portray three generations of the Holy Family—the Christ-child, his mother, and his grandmother, St Anne.

The individual figures twist or spiral upwards in what later came to be called the ‘figura serpentinata’; and the whole group aspires to the condition of a pyramid.

The two pictures are of course just as well known to the whole world as Michelangelo’s David.

The upper image here is the preliminary drawing on heavy paper (‘cartone’), known simply as the Cartoon, which is now in London.

You can feel something of Michelangelo’s earliest response to Leonardo (even though he is working in stone) in a four-foot high statue that he carved for some Florentine merchants working in Bruges.

The influence is particularly evident in the placing of a taller-than-usual Jesus, standing between Mary’s knees, and in the complex twist of his body (eyes looking down, right arm swung across and left thigh flexed).

More important for our purposes, however, is his attempt to actually outdo Leonardo—in Leonardo’s own preferred medium of paint—in a roundel he executed for the wealthy Doni family.

You will recognise at once the pyramidal grouping and the twisting ‘serpentine’ forms. (Mary is in an exquisitely difficult and uncomfortable pose that Michelangelo would later use for Eve; while Joseph is crouching, knees apart, as though in some kind of Cossack dance.)

At the same time it must be said that the outlines in the tondo are as sculpturesque and highly polished as Leonardo’s are painterly, soft, and lost in shadow; and that Michelangelo’s palette is as bright and clear as Leonardo’s is sombre and ‘smoky’.

There is not time to tell you about the direct confrontation between the two giants in 1505, when they were each working in the Council Chamber of the Republic on massive wall-paintings representing scenes of battle.

But I would invite you to look carefully at the two sides of a sheet from his sketch book which summarise Michelangelo’s interests, and document his skills in drawing, during these five years in Florence. (This single piece of paper is a microcosm of his art.)

In the centre of the first drawing (softly drawn in chalk, experimentally), you can pick out the expressive, back view of a a virile male nude, reaching upwards. On either side there are two rapid sketches for the pose of the Christ child in the Bruges Madonna (one seen from the from the front, the other from the rear). And last not least a superbly confident, detailed, sharp-edged, pen-and-ink study of the visible muscles in a left leg, possibly drawn from a statue; Michelangelo knew his anatomy.

In the second drawing, there is a very pale right leg in the centre and (horizontally, on the right) a lightning pen-and-ink sketch for the composition of the Bruges Madonna. The most revealing, however, are the figures on the left.

This is a worked-up study (with hatching and shading) for a complex group of soldiers (in a lost battle scene in the Council Room), where the extravagant pose of the figure who is being lifted in the air is inspired by the Apollo Belvedere, and the wonderful foreground nude is clearly a later version of the nude in the upper drawing, as you can confirm by a glance at the positions of the two right legs. (This is how a sculptor draws.)

It was when the cartoons for the huge fresco in Florence were ready that Michelangelo was summoned back to Rome for the second time.

The command came from the pope, by then two years into his pontificate, sixty-two years old, and burning with ambition to outdo all his predecessors.

He was a nephew of Sixtus IV and he had the same family name: Della Rovere (‘of the oak’).

When he was elected Pope, he chose the name of Julius—the Second, leaving little room for doubt as to the real identity of the First in his own mind.

You may remember him as the dominant figure in the Vatican Library fresco from the 1480s, at a time when he was still a cardinal.

He lost nothing of his imperious habit of command even as an older man, as is confirmed in the portrait of him—even though in reflective mood—by Raphael, shortly before his death in 1513.

Looking ahead now, in late 1505, he wanted Michelangelo to execute a much more imposing tomb for himself.

It, too, was to go into St Peter’s. But it was to be in white marble. And it was to be a free-standing structure in three tiers, like a wedding cake (as you can see in this reconstruction sketch).

Measuring thirty-six feet by eighteen, with over forty life-size figures round the four sides of the monument, it was a simply marvellous commission. Michelangelo himself personally supervised the quarrying and transport of the marble.

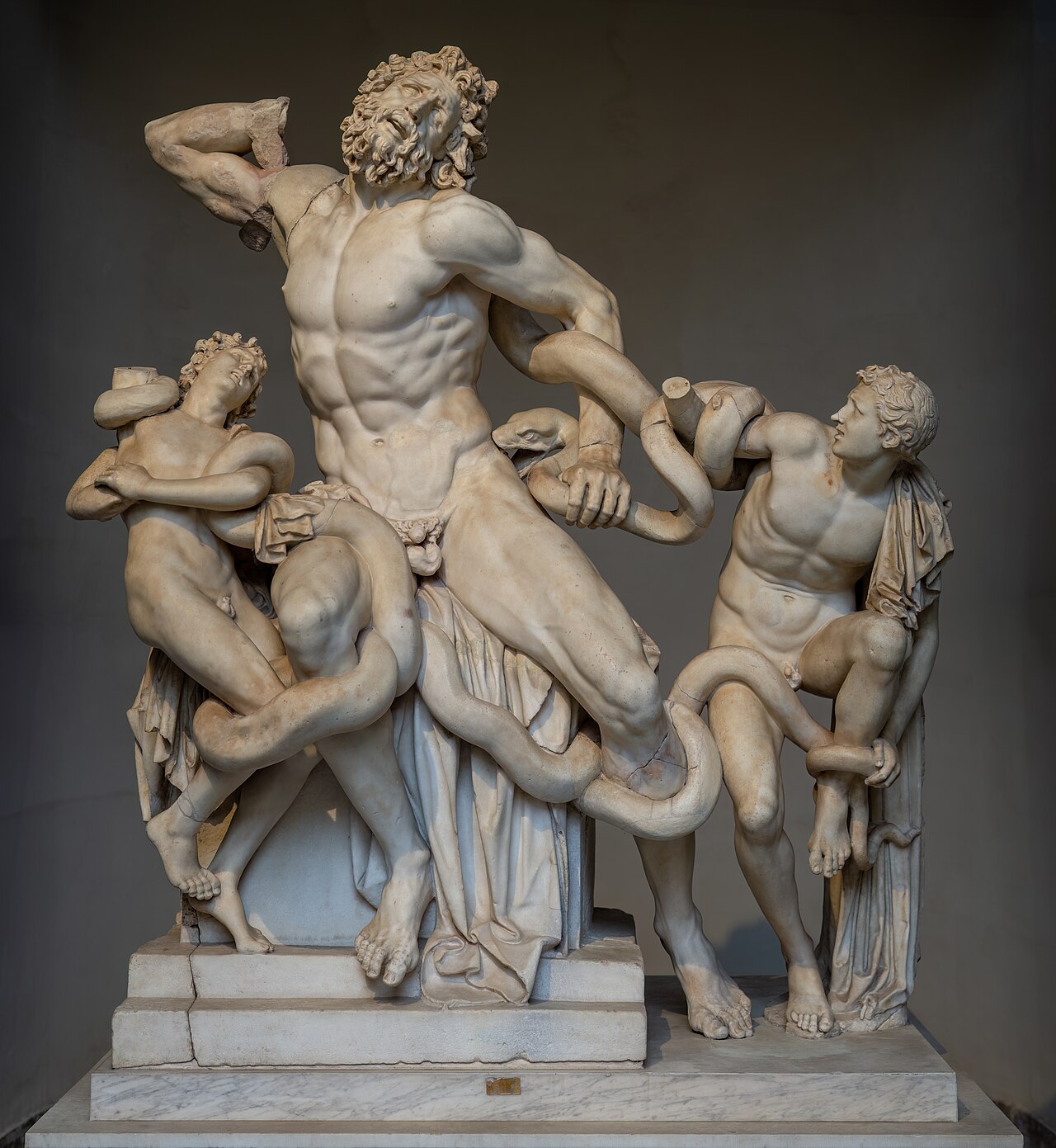

His sense of excitement was increased by the challenge arising from the chance discovery, in January 1506, of the famous antique group, representing Laocoön and his sons in the coils of two sea serpents.

Michelangelo must have studied the figure of the father very closely, because he would find inspiration here for the rest of his life (as we shall see in later lectures). So, notice the rib cage, the prominent nipples, the thicker waist, the strong ‘valley’ down the centre of his chest, the immensely powerful muscles in the left arm and leg, and the pressure brought to bear on the left toe.

We possess nothing that Michelangelo might have carved in the first flush of enthusiasm for his commission, but we know from his drawings that he was already visualising figures of the kind he was to execute a few years later (in 1513 and 1514).

These include the so-called Dying Slave (now in the Louvre), and Moses, who did finally take his place on a much more modest monument to the Pope in a smaller church.

The Slave was intended for the lowest level of the monument; and it is worth remembering that, technically speaking, this is a telamon, that is, a hybrid between a standing statue and a supporting column.

Alas, for all Michelangelo’s high hopes, the plan went sour almost before he had set to work.

Julius decided that old St Peter’s would not be big enough for his tomb, and in that same year of 1506, he resolved that the old basilica would have to be demolished, and that an entirely new church, worthy of the city in scale and architecture, would have to be erected on the same sacred site—thereby setting in train a long and infinitely costly project, which was mentioned in the first lecture of this series.

Michelangelo felt increasingly ignored and slighted by the pope, and only a few months later, in the summer of 1506, he simply ran away. There followed a battle of wills—which the pope won, hands down—which was succeeded by a period of penance, when Michelangelo was forced to cast a colossal bronze statue of Julius to stand in the city of Bologna (it was later melted down to make cannons).

We pass on, then, to the year 1508, when Michelangelo was summoned to Rome for the third time—not to continue work on sculptures for the tomb, but to redecorate in fresco the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, because the original decoration of the 1480s (possibly, just stars in a blue heaven) had been damaged by the appearance of cracks.

‘Making good’. What a come-down!

He accepted the commission unwillingly, protesting that he was a sculptor not a painter—but as you have seen from the roundel, and from the drawings, he was a simply marvellous draughtsman.

He must have reconciled himself to the task very soon when he realised that he would be able to develop, in one of the most prestigious buildings in the world, most of the ideas he had been forming for the architecture of the tomb—challenging antiquity in a vast range of idealised human figures, grouped and in isolation, standing and seated, clothed and unclothed. Hence, the rest of this lecture will be devoted to the painted architecture and the painted sculptures in his design for the ceiling as a whole.

Please keep in mind, then, the idealised male nude and the patriarch seated on his throne, while we remind ourselves of the shape and layout of the ceiling as it was when Michelangelo arrived in 1508.

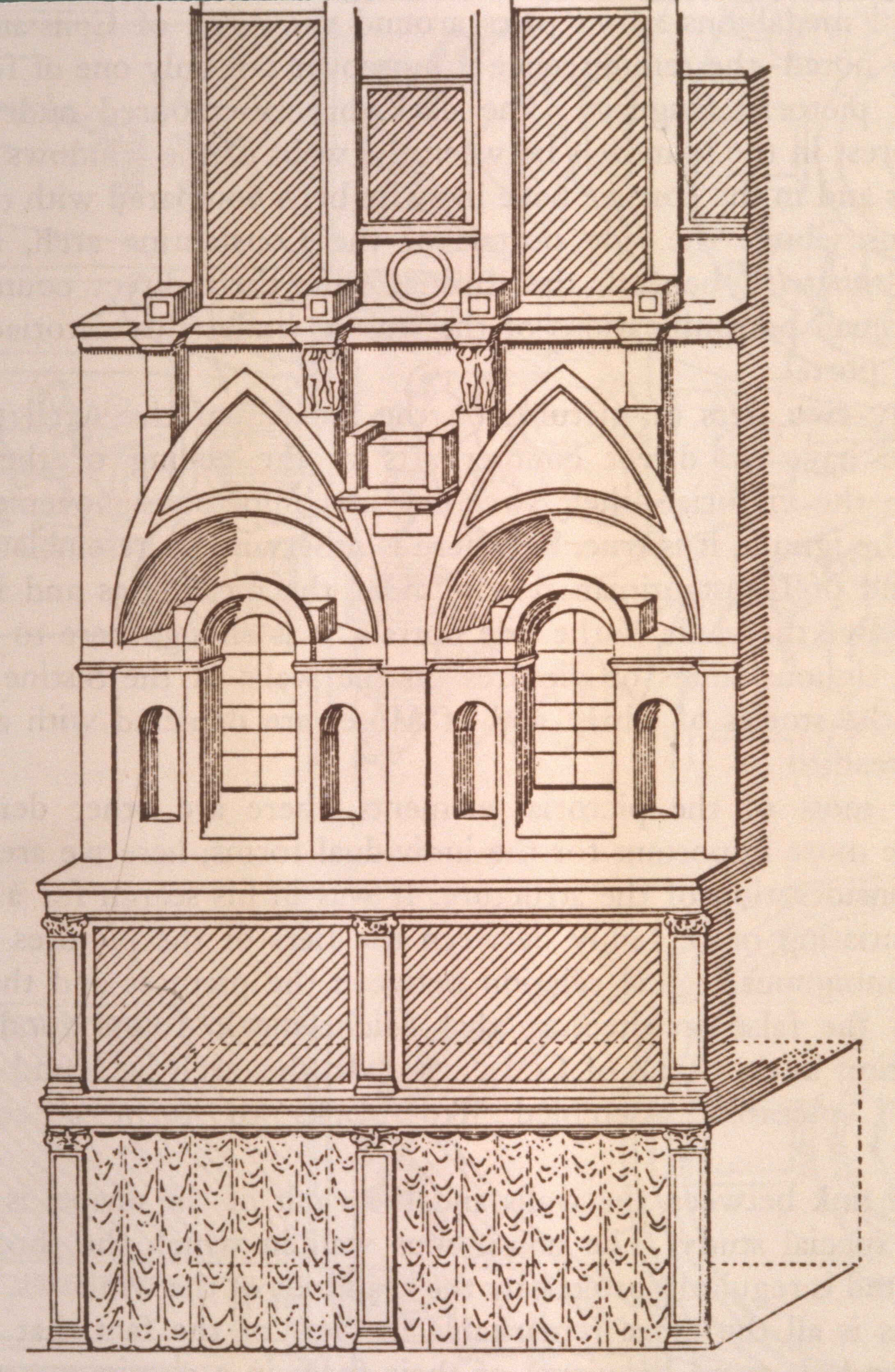

The ceiling is a vault, constructed with ribs and arches of the kind you see here in a church in Naples, which were exposed by bombing in World War Two.

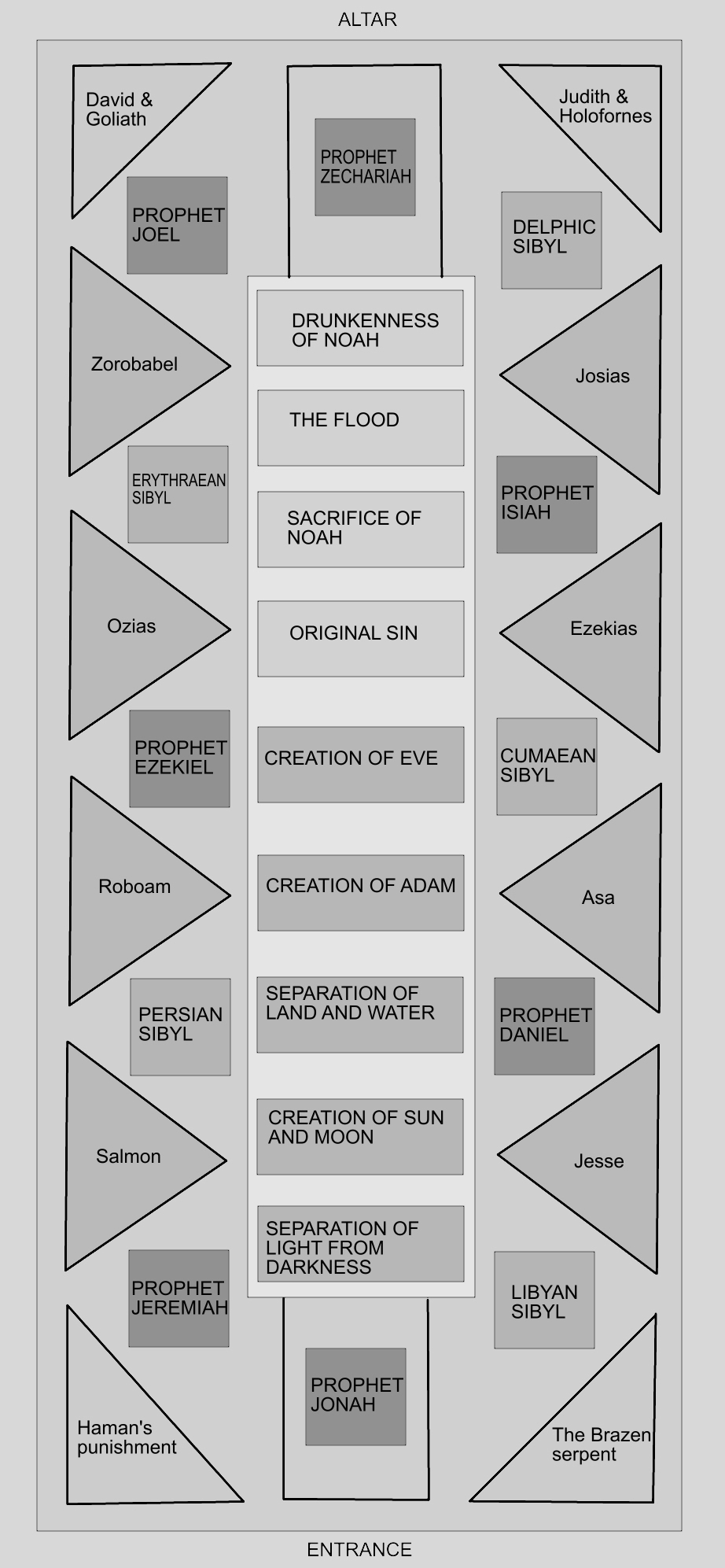

The architectural ‘skeleton’ was plastered over to form a smooth barrel vault, the weight being carried down between the windows in an area which (following custom) I shall refer to as ‘pendentives’.

Notice that the windows are surrounded by a crescent-shaped area, still in the vertical plane, called a ‘lunette’; and that the four central windows on each of the side walls are topped by a triangular area, curved in section, cutting into the flatter curve of the main vault (I shall call them ‘spandrels’).

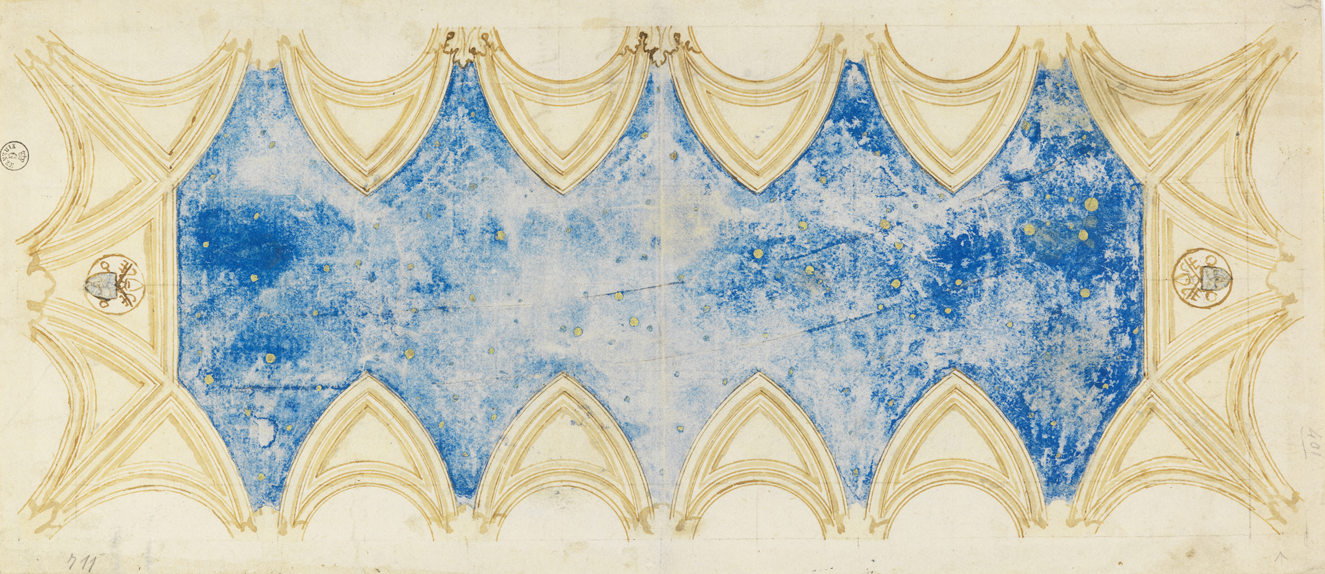

In the corners, there are broader ‘double spandrels’, uniting the lunette above a window on the end wall with that above the first window on a side wall; the result being that there are only five pendentives on each of the side walls, as you can confirm by counting the blue ‘pyramids’ in the design for the original decoration in the 1480s.

There was, of course, one pendentive on each of the end walls (they are not coloured blue in the drawing), making twelve pendentives in all.

From 1485 until about 1505, the year in which large cracks had to be repaired, all these different areas on the ceiling would have been decorated as you see in the drawing and the nineteenth-century reconstruction.

The main barrel vault and the twelve pendentives were painted in blue, possibly studded with stars; while the vertical lunettes, and the curving spandrels, were painted in some unspecified neutral colour.

Our next task is to look briefly at some other ceilings, more or less contemporary, so that we can assess which elements in Michelangelo’s solution were original, and which traditional, and so that we can see how the minds of the artist and his patron would have been working.

It was perfectly normal practice to paint a smooth barrel vault blue, and to decorate it with stars; and it was just as commonplace to paint the single figure of an apostle or a prophet in the spaces defined by the groins of a pointed Gothic vault.

The lower image shows the vaulting over the altar in the church of Santa Croce in Florence, conveniently tilted; and you will notice how the painter respects and emphasises the shapes provided for him by the architect.

(In a contemporary palace, however—that is, a late fifteenth-century secular building—the ceiling might have been richly ‘inlaid’ or coffered; and hence there was clearly a temptation to simulate this kind of pattern in the medium of fresco.)

These two images are photographs of a library (built in memory of Pope Pius II on the flank of the cathedral in Siena), which was decorated by Pintoricchio in the early 1500s. (Its decorative scheme forms the subject of the last lecture in the Siena series.)

There are no windows in these walls, but the shape of the room is strikingly similar to the Sistine Chapel.

In the first photo, notice the pendentives, spandrels and lunettes; and, in the second, notice how the artist has covered the vault with a carpet-like design of interlocking rectangles of different sizes.

Many of these rectangles (they are known as quadri riportati in Italian, ‘paintings carried up high’) contain figures of gods and men.

But the figures are all very small, so that the effect is undisturbing and more or less unchanging from any angle of vision.

In Raphael’s case, however, the human figures are much more prominent within the abstract, geometrical designs; and it soon becomes painfully obvious that there is no one viewpoint from which all these figures will appear the right way up.

If you twist your head (or rotate the second image through 90°) in an attempt to make Abraham stand upright, then Jacob will be dreaming upside down.

(It is of course true that one does not normally lie on one’s back in the centre of the floor: one only glances up for a few seconds at a time, and the effect is not usually disturbing. But keep the point in mind.)

In the three examples we have just considered, there was certainly an attempt to simulate other decorative materials—stucco or mosaic—but there was no attempt to disguise the architectural reality.

This was not good enough for more sophisticated patrons; and already back in the 1470s, Mantegna had decorated a state room in Mantua (the one that came to be known as the ‘Camera degli Sposi’) in such a way that the true vaulting is disguised, and there seems to be a little cupola, with an oculus open to the sky through which people are peering in.

However, the trouble with any trompe l’œil painting that actually contradicts the true planes of the surface on which it is painted, is that the illusion only works from one viewing point, and can look pretty weird or awful from any remote point.

Please keep all these factors in mind as we return now to the Sistine Chapel as it was in the year 1508.

The pope seems to have counted up the pendentives, found there were twelve, remembered his counting rhymes (‘eleven for the eleven who went to Heaven, and twelve for the twelve apostles’), and suggested that twelve apostles should be enthroned in the pendentives.

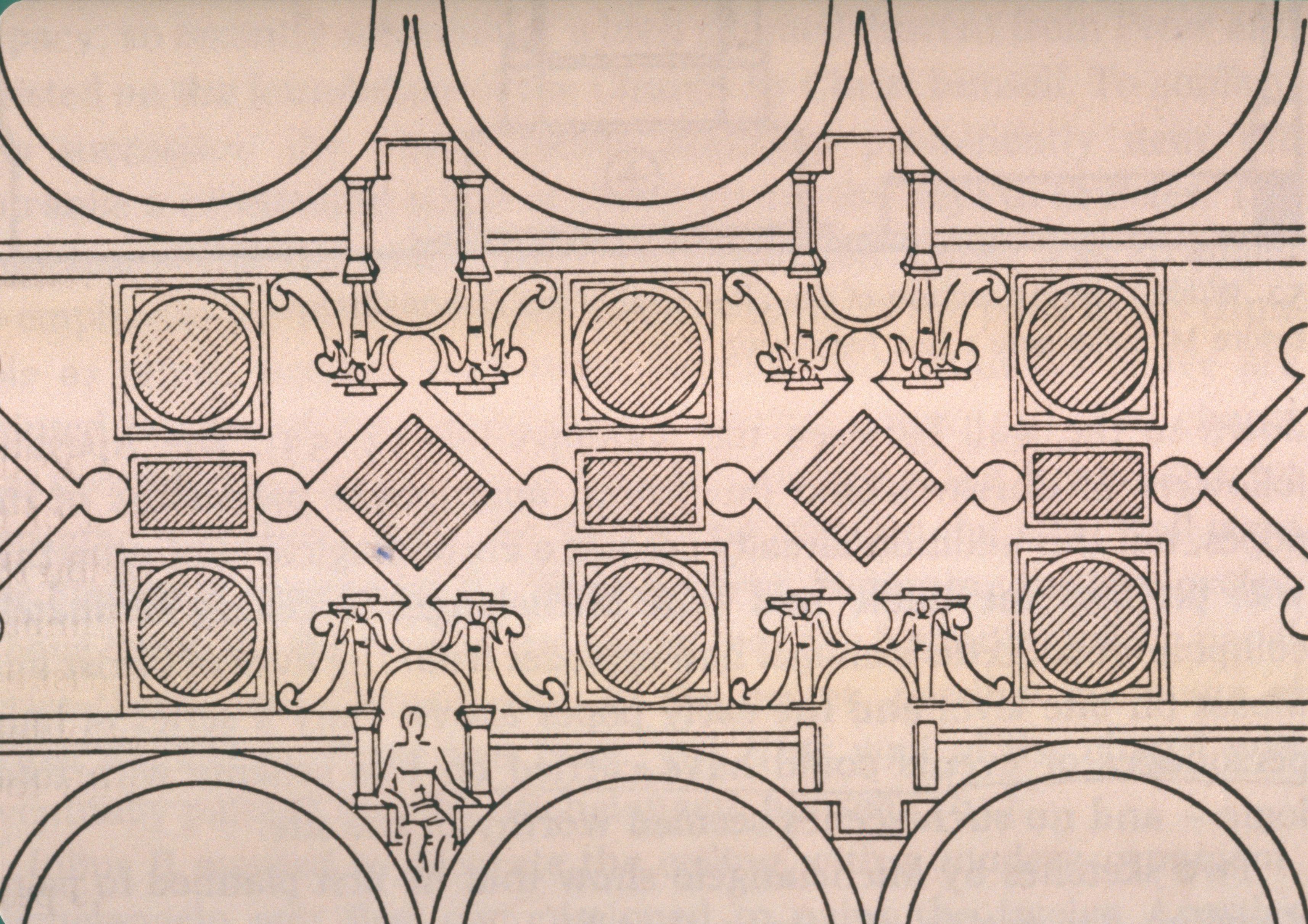

Judging from Michelangelo’s later account, and more importantly, from his first doodling (in red, on the left of the sheet), he seems to have begun by combining this very medieval idea with the geometrical approach we found in Pintoricchio.

He placed a prophet, on a handsome throne, in the pendentive. Above the elaborate pediment over the throne, he placed a small lozenge, with balls at each corner; and on each side, there was a bigger circle inscribed in a square, topped by a small rectangle.

Draw the whole thing out more tidily, and the design would have been something like you see in the very helpful diagram.

Focus hard on the thrones, the seated prophet, the lozenges with balls, the circles in the squares, and the tiny rectangles between them.

However, Michelangelo must have felt that this would be too ‘bitty’, and would leave him no opportunity, or room, to depict human figures other than the apostles.

At some point, then, he decided to join up the little squares and rectangles over the central windows to form large rectangles, each of which would carry a narrative painting (of the kind we just saw in Raphael), with figures that would be clearly visible from the floor nearly sixty feet below; while the adjacent area (the original lozenge) could be redesigned to contain a smaller rectangle with fewer figures, but all in the same scale.

As a result, pure geometry gave way to a decision to treat the centre of the ceiling as a picture gallery, with nine separate narrative scenes, arranged as you can read them in the diagram and see them in the tilted photograph.

Notice in the photograph that all nine narrative scenes can be ‘read’ with the figures the same way up (the right way up!), from a position near the entry wall, looking along the chapel towards the altar—exactly as you can read all the titles in the diagram, starting from the bottom of the page.

They do not pretend to be anything other than pictures stuck on the ceiling (quadri riportati).

There is no illusionism. And when you are looking at the nine scenes in the biblical story (as we shall do in the next lecture), it is best to close your eyes to everything else, except perhaps the prophet Jonah, over the altar.

All the other figures on the ceiling, however, do involve the perspectival complexities we met in the ‘Camera degli Sposi’; that is to say, they are painted illusionistically to suggest a setting and architecture which are different from that of the chapel—a building with higher walls, no curvature, and open to the sky between the horizontal cross beams.

If you want to experience the effect intended by Michelangelo properly, you must collaborate—and use your legs.

You must go to the altar end of the chapel, take up a position on one side, close to the wall, and look up at the two bays opposite.

Then you must cross to the other side, and repeat the process.

Then you must move along the chapel towards the entrance, taking up at least three more distinct viewing points on each side, and always looking up and across.

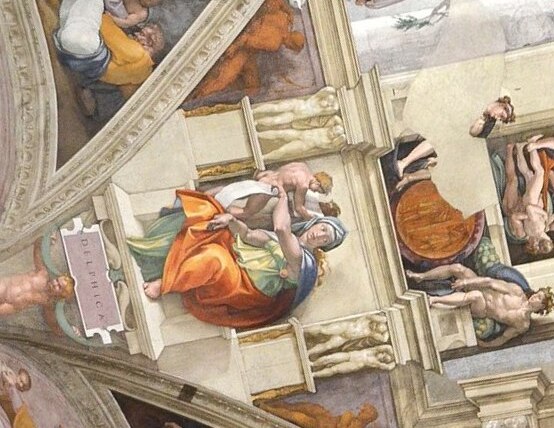

The Delphic Sibyl is not meant to appear as she does in the upper image—almost toppling down on you—but as though she were seated, comfortably in the vertical plane, as you see her in the lower.

If you play Michelangelo’s game, what you will see is a complex and convincing architectural setting, illustrated in the helpful diagram: a setting which provides different niches, areas, or supports for all the figures which do not take part in the narratives, and which extends both the real and the fictive elements of the architecture of the original design of 1485.

Before I take you through the diagram however, I must stress that Michelangelo was faithful to the original design in another way. All his figures (outside the narratives), and all the new architectural features, are painted as though they were illuminated by the natural light coming from the pair of windows that used to be over the altar.

Our diagram must represent the North wall—that is, the wall on your left as you face the altar—because the shading indicates that the light is falling from left to right.

Let us begin, then, by revising—very briefly—the main facts which were explained in the previous lecture in this series, in order to see how the new elements were meant to fit in with what was already there.

The lowest band shows the simulated tapestry from 1485, which is divided by simulated pilasters and topped by a simulated cornice. The next area (shaded diagonally) is occupied by the narrative frescos of scenes from the life of Jesus (on this north wall, and of Moses, on the opposite wall), also painted in the 1480s.

Note that the cornice above the narratives is a real one, projecting into the chapel; and, of course, the windows are real.

The niches (resembling little sentry boxes) flanking the windows are once again simulated (being painted to suggest a depth sufficient to accommodate the simulated statues of the first thirty popes) and are topped by another real cornice.

All these features belong to the original decorative scheme.

Now we may move on to examine the areas frescoed by Michelangelo which are shown in the upper part of the diagram.

So, before we proceed, please look at the same diagram for the last time to locate the lunettes above the windows; the triangular spandrels; and the fictive thrones in the pendentives.

All the details illustrating the next section, by the way, are deliberately taken from the east end, which in the special case of the Sistine Chapel, is the end furthest from the altar.

In other words, they are all taken from the first phase in the execution of the vast enterprise, before the unveiling to the public (which enabled Michelangelo to judge the effect of his design from the floor), and before a long pause in the work, as mentioned earlier.

In the upper image here (belonging to the south wall, with the light falling from right to left), the moulding round the window really does project a few inches into the Chapel.

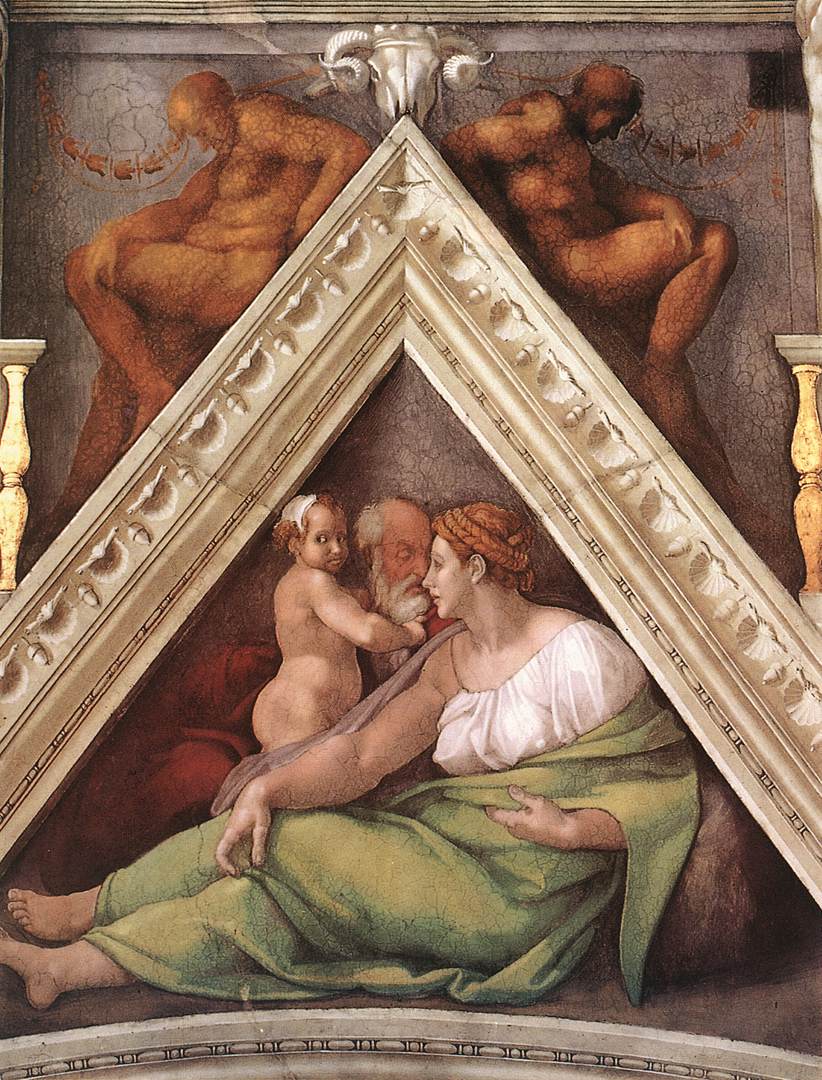

The lunette (which is indeed in the vertical plane) is painted to suggest that the space it contains is just deep enough—say two feet or so—for people to perch on either side of the window.

(These figures are among the Ancestors of Christ, whom we shall study in the fifth lecture; and their names are always spelled out in the elaborately framed, central ‘noticeboard’.)

The curving section of the spandrel above the lunette is given a deeper floor space, apparently about six feet deep, such that one figure can now sit behind another in a family group, resting, for all the world like a Holy Family on the Flight to Egypt.

(These, too, are among the Ancestors of Christ).

Immediately above each spandrel, where the tip of its simulated stucco frame meets a simulated cornice, there is always a simulated ram’s skull—a motif from classical architecture.

To either side of the ram’s head (against a purple ground, in every case), there are simulated bronze statues, suggestive of wild men or satyrs.

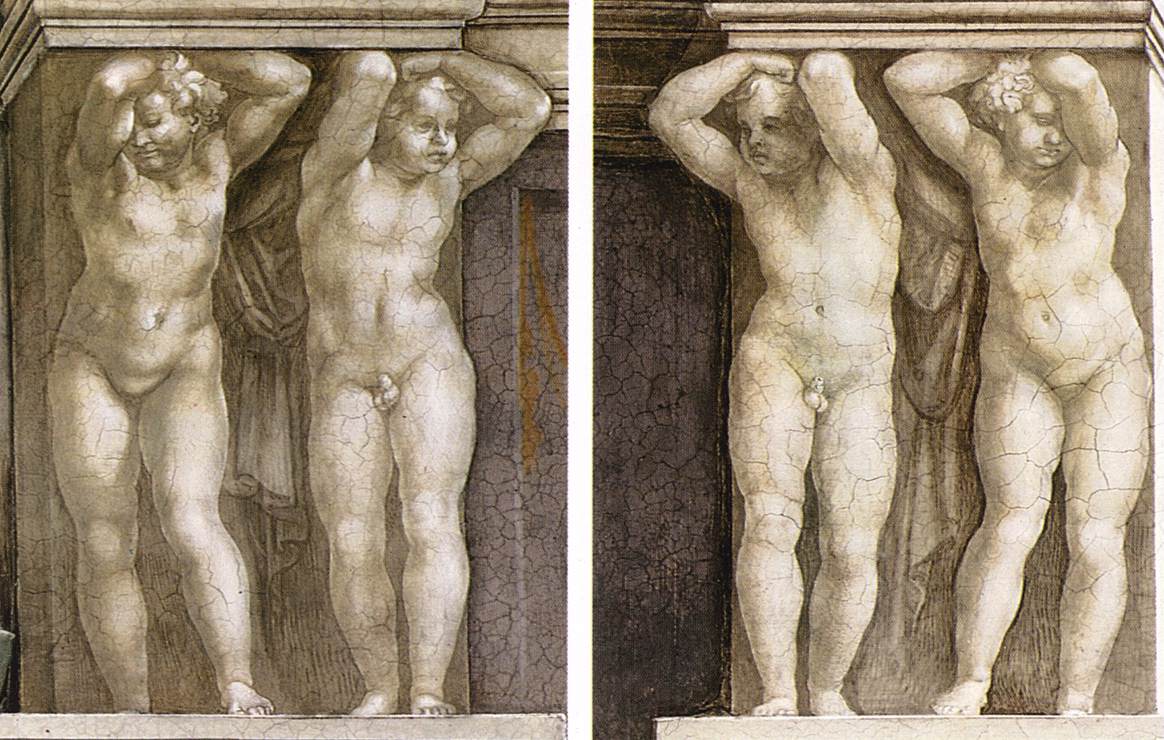

The poses are varied for each bay, but the body of each figure in a given pair is a mirror image of the one on the other side, pricked onto the wall from the same cartoon in reverse.

Alongside the spandrels, the prophets’ thrones are painted in such a way that the side pillars seem vertical when seen from the appropriate viewing point (although in reality, they are on the steeply curving pendentive).

They are always painted in such a way that the seat of the throne seems to project into the chapel space (whereas the lunettes and spandrels were made to seem like recesses).

The seated figure is a Hebrew prophet (in this case Isaiah); but ignore him for the time being and focus on his throne in the lower image.

Notice how the pilasters are divided at the half-way point. The lower half is a plain plinth, set between two gilded banister rails. The upper half is formed by a pair of simulated marble statues of two putti, acting as telamons (in principle, exactly like the so-called ‘Slaves’ in the abandoned project for the pope’s tomb).

Once again, each member of the pair of putti is a mirror image of its neighbour (the outline having been transferred to the wall from the same cartoon), even though there is a different pose for each of the twelve thrones.

We come now to the most daring piece of illusionism.

The pillars of the throne seem to support a continuous cornice (of simulated stone) more or less at the point where the curve of real ceiling begins to flatten out. But above the columns of the throne, there seem to be two low projections—like stumps or foot stools—which are painted as though they were still rising in the vertical plane.

On these projections, there are life-sized figures, flesh-coloured, naked, and apparently very much alive, who are also to be understood as rising in the vertical plane, although they are in fact painted on the flat part of the vault, and not foreshortened from below.

Each pair of nude figures is supporting, by means of a piece of cloth stretched between them (sometimes large enough to form an improvised cloak), a roundel which is painted to resemble a bronze medallion, with a narrative scene shown in apparent relief and painted in grisaille.

If you look closely at the top of the detail, you will see another recurrent feature—acorns among oak leaves, alluding to the emblem of the della Rovere or ‘oak’ family, to which Pope Julius and his uncle Sixtus belonged.

This wide-screen image demonstrates how most of the features we have been examining fit together.

Ignoring for a moment the Delphic Sibyl seated on her throne, let your eye travel left beyond the paired statues in bronze and the huddling Ancestors of Christ, and you will take in the Prophet Isaiah on his throne, with pairs of telamons half way up its marble pilasters, and its stumps, extending above the stucco cornice, on which two (invisible) nudes are holding the medallion above him.

I have now shown you virtually all the recurrent, pattern-making figures in Michelangelo’s design, and the different architectural settings provided for them.

Since I am sure that this is the best way to appreciate the many ‘themes and variations’, let us mentally move a few paces to the right—with our backs still to the South wall—and revise what you have just learned by looking at the throne to the right of Isaiah, starting at the top this time, and moving downwards.

Above the throne sit the nudes, supporting an (invisible) medallion by means of a piece of purple cloth (notice the fingers of his right hand), half revealing and half displaying a very prominent ‘swag’ of acorns.

Directly below the nudes and their medallion, the broad, classical marble throne thrusts itself out into our space, offering a shallow seat for a prophet—in this case a female prophet of the Gentiles, that is, one of the Sibyls. (The one you are looking at is the Sibyl from Delphi, identified as Delphica). On the arms of the throne are pairs of marble putti acting as telamons (that is, apparently supporting the fictive cornice).

Remember, too, that all the figures I have just shown you are modelled as though the light were falling from left to right, because they are all on the North wall.

I have not said anything yet about the conceptual organisation of the ceiling, which will be the subject of the next lecture. But whereas the fifteenth-century narrative frescos are not really intelligible until you have done your biblical homework on the stories and understood the parallels between the Old and New Testament scenes and the political message embodied in these parallels, you could do a great deal worse on a first visit to the Chapel than follow the strategy I have just outlined.

Try it when you go. Take up four successive positions on each side, look at a pair of bays on the opposite wall and examine them systematically, scanning up and then down, in order to take in all the variations of the figures in their unvaried architectural setting.

Now that we have got an idea of the layout, we must look at some of the individual figures.

These include a number of images that were to change the course of Western art because they changed perceptions about the nature of man, about the relationship of body and mind, and about the relationship of Christianity and classical civilisation.

I shall concentrate on representatives of the two groups which relate most closely to the sculptures which Michelangelo had planned for the tomb of Pope Julius: the enthroned patriarchs or prophets, and the so-called ‘Slaves’.

We begin with some of the twenty ignudi (nudes) above the thrones, of whom you see another in this first image. (It too comes from the eastern half of the chapel—the half that Michelangelo frescoed before he had a chance to see the total effect from the floor.)

The ignudi have been interpreted in an extraordinary number of different ways: psychologically, as sublimations of Michelangelo’s presumed homosexual feelings; culturally, as expressions of Renaissance Platonism and the struggle between the spirit and the flesh; theologically, as manifestations of the human spirit before the time of the Written Law; rather cautiously, as angels (Michelangelo only once represented an angel with wings); pedagogically, as Michelangelo’s complete guide to human anatomy, especially the muscle groups; or as his complete guide to the art of foreshortening and the art of ‘contrapposto’, which he had rediscovered in the statues of the ancient world (‘contrapposto’ being defined rather economically by Chambers Dictionary as ‘a pose in which the hips, shoulders and head are all in different planes’).

Of these generalisations, the one which I personally find most helpful is that all the ignudi are attempts to ‘complete’ an ancient Roman torso, the so called Torso Belvedere, which Michelangelo is known to have greatly admired.

As with the Laocöon, he seems to have drawn the bust from all possible sides and angles, and treated it like the stem of a Latin noun, onto which he would tack the various case-endings (mens-a, mens-am, mens-ae etc.) in the shape of arms, legs and heads.

Bear all these possible interpretations in mind, then, as we look at the last eight nudes to be painted—in the freer, bolder style of 1511 and 1512—the ones which stand over the two pairs of thrones nearest the altar wall.

We begin with a pair on the south wall, as the fall of the light confirms.

I will not attempt to ‘interpret’ these eight figures, but merely invite you to look at them closely—directing your attention to the amazing difficulty, originality, and sheer variety of their poses.

Bear in mind that, in each case, their bottoms are supposed to be resting on the very low plinths, that one arm should be holding the cloth that supports a medallion, and that one leg should act as an ‘anchor’, on or near the base of the projection.

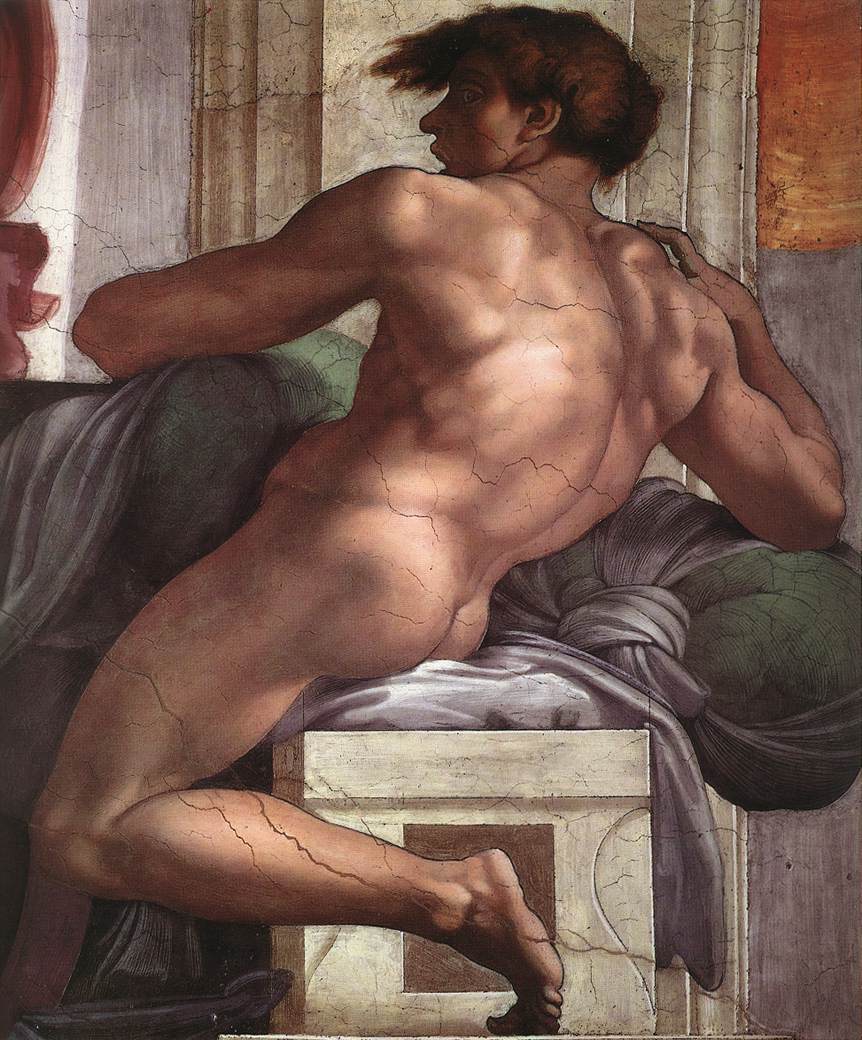

The left hand nude immediately contradicts this expectation. Both arms are swung across the body, away from the medal, and both legs swing in the other direction. The improvised cloak billows in a mysterious wind, concealing the long curling hair over the distinctively ‘epicene’ features.

His partner is seen in profile and is not really seated at all. His left leg is flexed as he pushes down on his big toe. He twists to reveal his broad shoulders and a powerfully muscled back deriving from the Torso Belvedere. His right elbow is doubled up almost impossibly (look at the forefinger), and his short hair is blown forward over a face which is decidedly less refined.

Cross the chapel now to look at the pair on the opposite wall, with a corresponding reversal in the direction of the light.

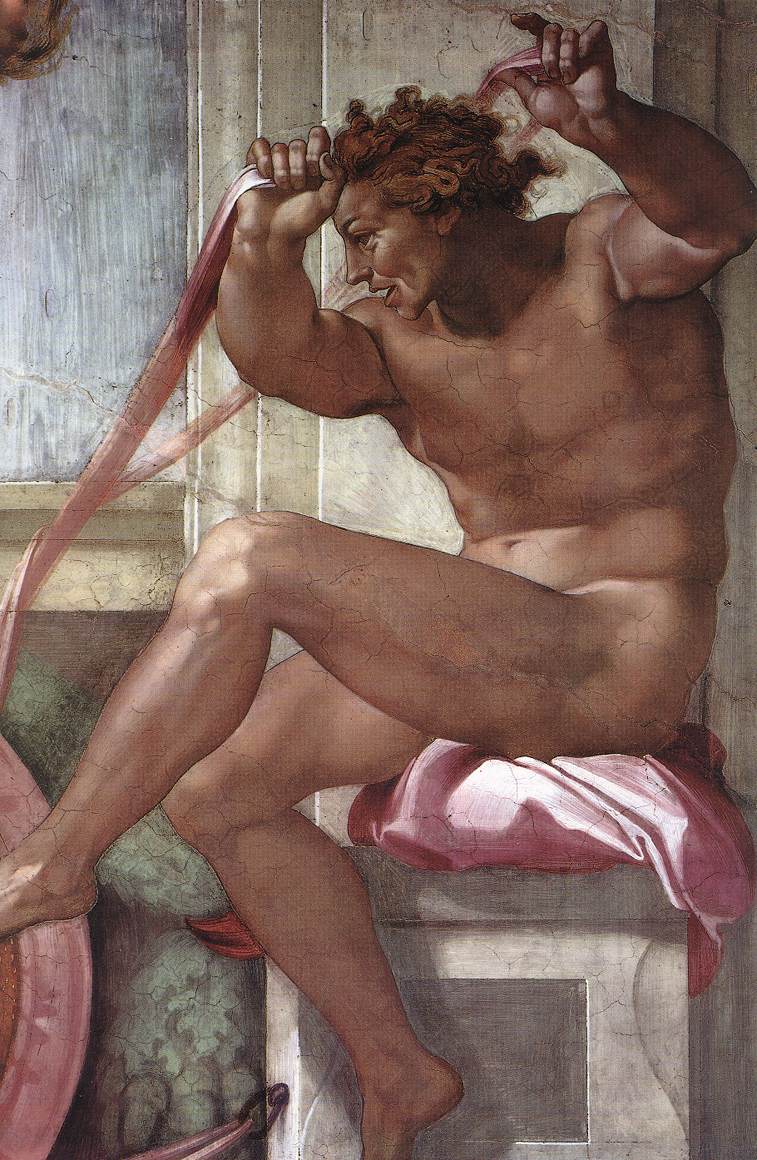

The left hand figure stares at us with an enlarged eye. The lips are thick, the hair tousled, the right arm folded behind him to reveal a weight-lifter’s back (again from the Torso Belvedere) and a prominent nipple (from Laocöon). The right leg is doubled up, lifting the buttocks quite clear of the plinth; while we can only just see the fingers of the left hand, which tightens the fabric that supports the medallion.

His partner certainly has his eye fixed on the medal, but he seems to be trying to twitch the piece of cloth free (a delightful touch of Michelangelo’s humour).

His mouth is open and both arms are raised towards us, the right forearm being grotesquely enlarged by the foreshortening; and the chest is thereby fully exposed.

Both legs are clearly visible, the lower one braced to give firm support.

Staying on the north wall this time, we move to the throne nearest the altar.

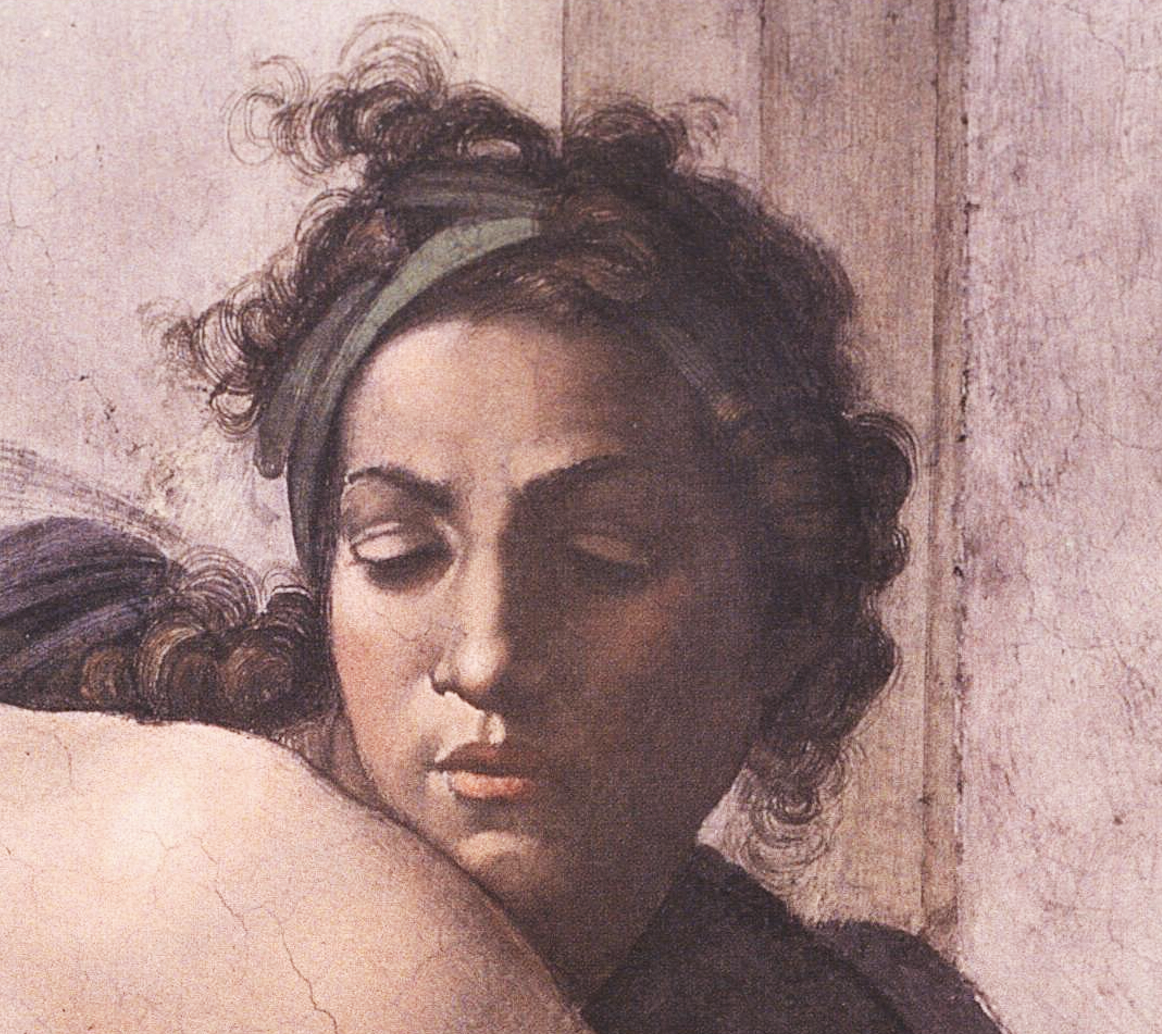

The left-hand nude has both feet anchored; he is sitting essentially sideways and leaning sideways too, with his right upper arm almost horizontal, creating a wonderful sweeping line from hip to elbow, while not exaggerating the powerful muscles.

His head is disturbingly small, epicene and erotic (the eyelids are lowered, the full lips almost pouting).

It is set oddly on the shoulders and turned vigorously to its right, so that it is presented full-face; and the spiralling strands of wispy hair are held in place by a most elegant ‘sweat band’ placed above the striking Y of the nose and eyebrows:

His partner comes closest to the standing position of all the ignudi, such that we follow the line of his left leg, side and upper arm almost in the vertical plane; whereas the line defining the other side of his body could hardly be more complex.

His right leg is doubled beneath him, with the calf squashed flat; the right arm lowered and folded to reveal the back of the hand, as though he were playing a violin. His head rocks away to expose the area beneath the chin; the eyes are apparently seeking his reflection in a mirror.

Moving over now to the south wall—again close to the altar—we find the body most closely modelled on the Torso Belvedere.

The left leg is bent back like a hurdler’s, the chest and head are leaning forward and to the side; the right arm (‘impossibly’ foreshortened to show a colossal elbow joint) is apparently about to empty a sack of coal, rather than hold acorns.

His partner, finally, is the most serene and the most seductive of all the ignudi.

His right foot is hooked coyly behind the left knee, the chest revealed by the advancing left arm. Both hands are relaxed, with curving fingers; and the head is turned against the body to reveal, under another ‘sweat band’, a Grecian profile (a strikingly androgynous beauty) and a huge eye apparently seeing nothing, lost in private contemplation.

We come, at last, to the twelve enthroned figures—seven Prophets and five Sibyls—in order to consider them in their own right. (You have already seen Isaiah and the Delphic Sibyl, but simply as incumbents of a throne.)

I will not say anything in this lecture about their role in any overall conceptual plan, except that it was standard practice to portray Hebrew prophets in a scheme of this kind, and that the choice of the seven males (once this number has been determined) is not in the least surprising.

The four so-called greater prophets—Isaiah, Jeremiah, Ezekiel, and Daniel—were almost bound to be there. And among the twelve minor prophets, two of them had special claims to be on the end walls: Zachariah and Jonah.

Let us begin with them and register the astonishing difference in style between the greybeard and the youth—the first having been painted in 1509, the second, after the long interruption, in 1512.

Zachariah prophesied Christ’s entry into Jerusalem on an ass at the beginning of Holy Week, on Palm Sunday, and he is therefore placed over the entrance.

He sits in profile, voluminously robed, reading intently, while two putti (the source of his inspiration) stand quietly behind him, one with his arm round the other.

Jonah, on the other hand, was particularly associated with the Resurrection of Christ, commemorated on Easter Day at the end of Holy Week; and he is therefore placed directly over the altar.

His legs are bare and dangling, his naked left arm is swung across (the forefinger pointing behind him), his body sprawls backwards in a dizzying tour de force of perspective (contradicting the concave curve of the ceiling).

His head is thrown back and his eyes seek inspiration from heaven (not from the storm-tossed putti).

Two distinct moments in his dramatic story are recalled (2:10 and 4:6–10). He shares his throne with the diminutive whale, who has just spewed him from its belly; while he is already seated beneath the fig tree which gave him shade.

It was not unusual, in this period, to include some of the Sibyls—that is, the prophetesses known to the Greeks and Romans, who by medieval times, had become twelve in number, like the apostles, and who were each credited with a prophecy of some part of the Christian revelation.

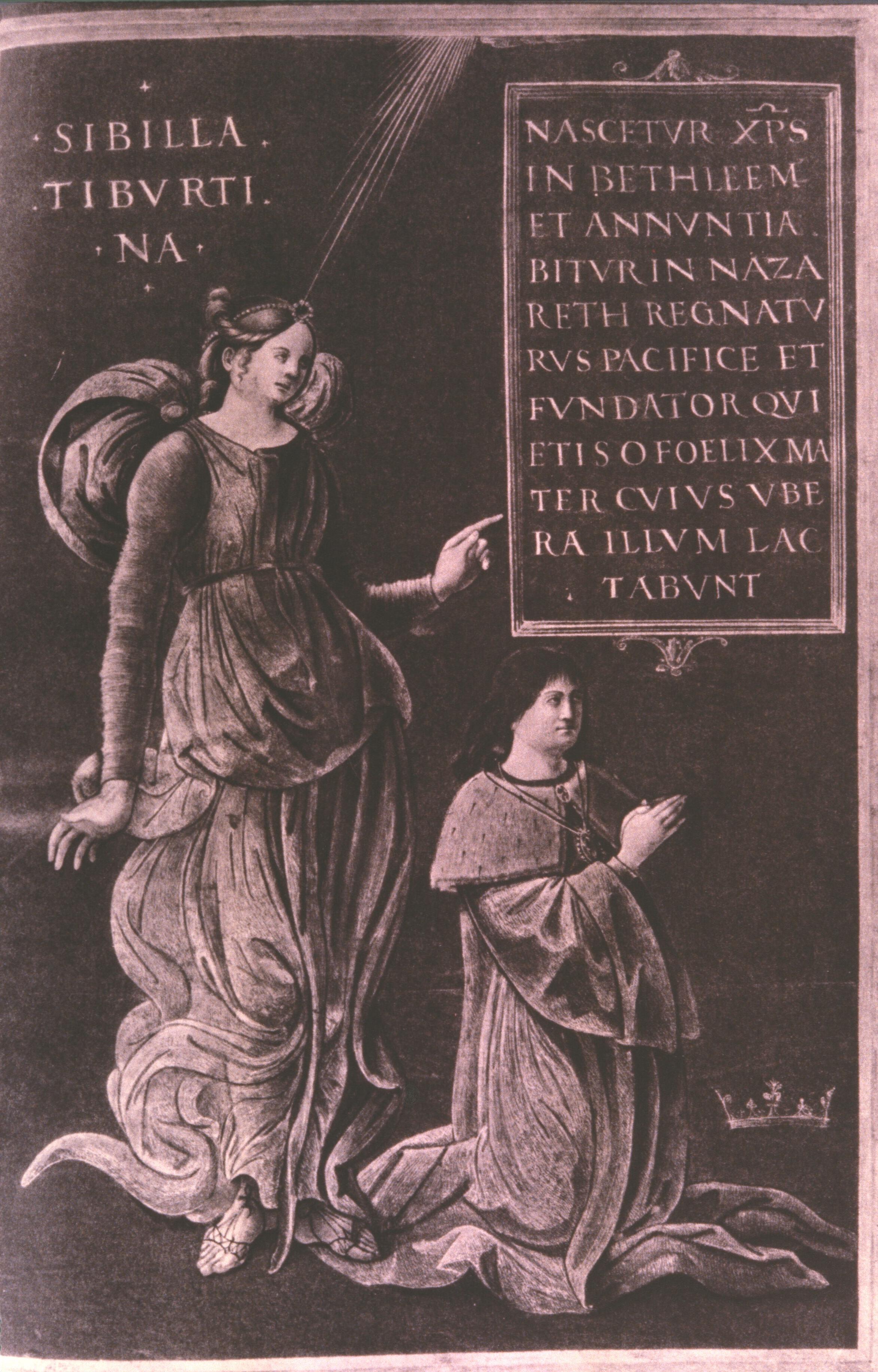

(As a single, pertinent example, I show you, in the upper image, a Sibyl—proudly displaying her prophecy—painted by Michelangelo’s first master, Domenico Ghirlandaio, in Florence, in the early 1490s.)

In the case of the Sibyls, too, the inclusions and exclusions (when choosing five out of the twelve) are not particularly puzzling.

The Delphic Sibyl (whom we saw in context earlier), was the priestess of Apollo par excellence, and simply had to be there.

Notice the three dazzlingly bright colours of her headdress, mantle and chemise; the arm held horizontally across the body to display her prophetic scroll in the vertical position (with the words visible only to her); her head alert, with the unseen ear absorbing the words of the putto behind her; and her wide eyes (Mary’s eyes in the Doni Tondo) gazing sideways, lost in concentration.

The Tiburtine Sibyl (the Sibyl from Tivoli) might well have been included because she was closely associated with Rome and the Capitol.

(You see her as a slender maiden in this fifteenth-century image, duly labelled, and duly pointing to the words of her prophecy, in splendid contrast to the art of Michelangelo.)

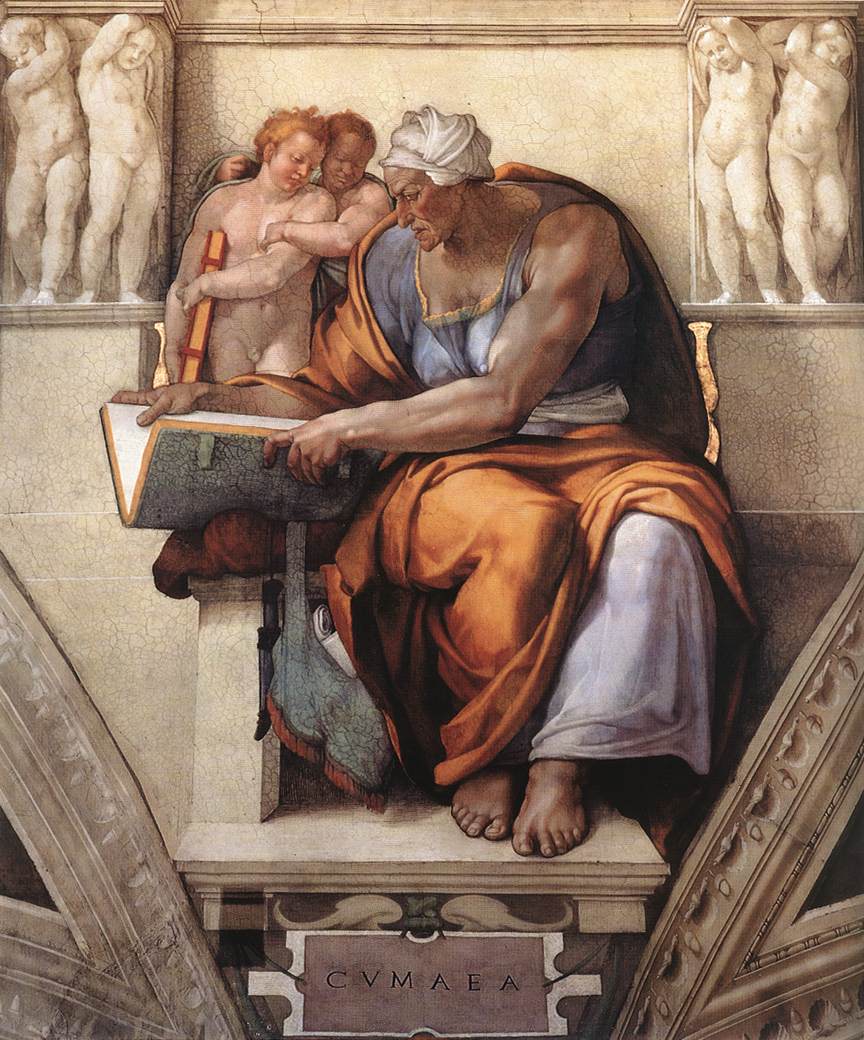

But to have chosen her would have caused an ‘overlap’ with the Cumaean Sibyl, who was even more closely associated with Rome through the story of Aeneas and the legend of the Sibylline Books.

She simply had to be in the chapel; and she has become one of Michelangelo’s most famous creations.

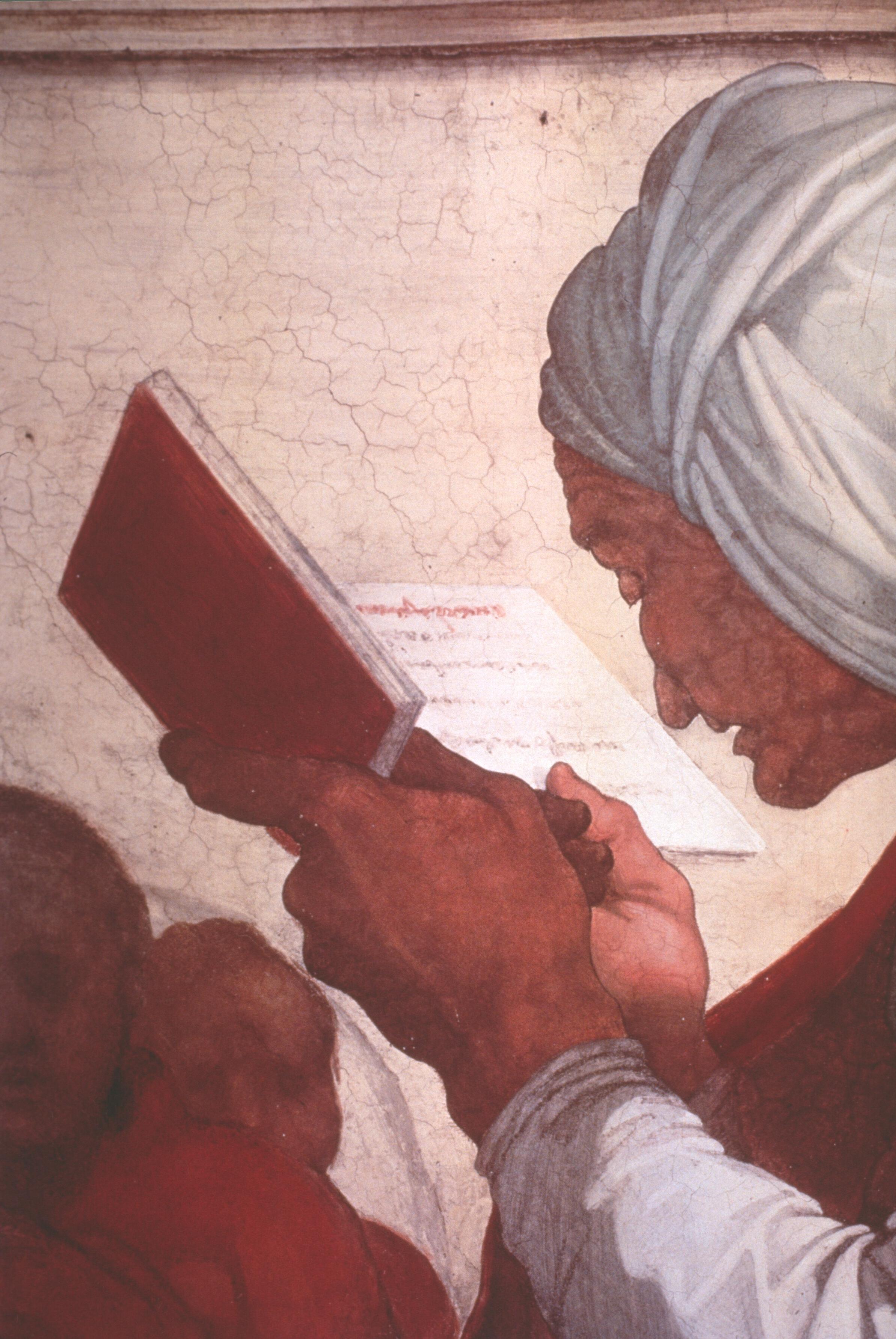

Notice her male body (she would certainly be tested for possible use of steroids today), her massive girth but tiny head, and her old face seen in profile, while she holds her Book open (allowing the two charming putti to read the relevant prophecy).

I have allowed you a quick glimpse of five of the twelve enthroned figures so far, and you will have been registering the differences in age, sex, characterisation.

As we look at the remaining figures, I would ask you to focus in particular on one problem of representation common to them all. The thrones are enormously wide; and Michelangelo clearly set himself the task of finding ever more effective ways of posing both prophets and sibyls in such a way that they would fill the space convincingly and imposingly.

The last four figures to be painted are those nearest the altar wall. There are two young and two old, two female and two male; and in each case Michelangelo, returning to the chapel late in 1511, tackled the compositional problem in a new way by making them significantly bigger.

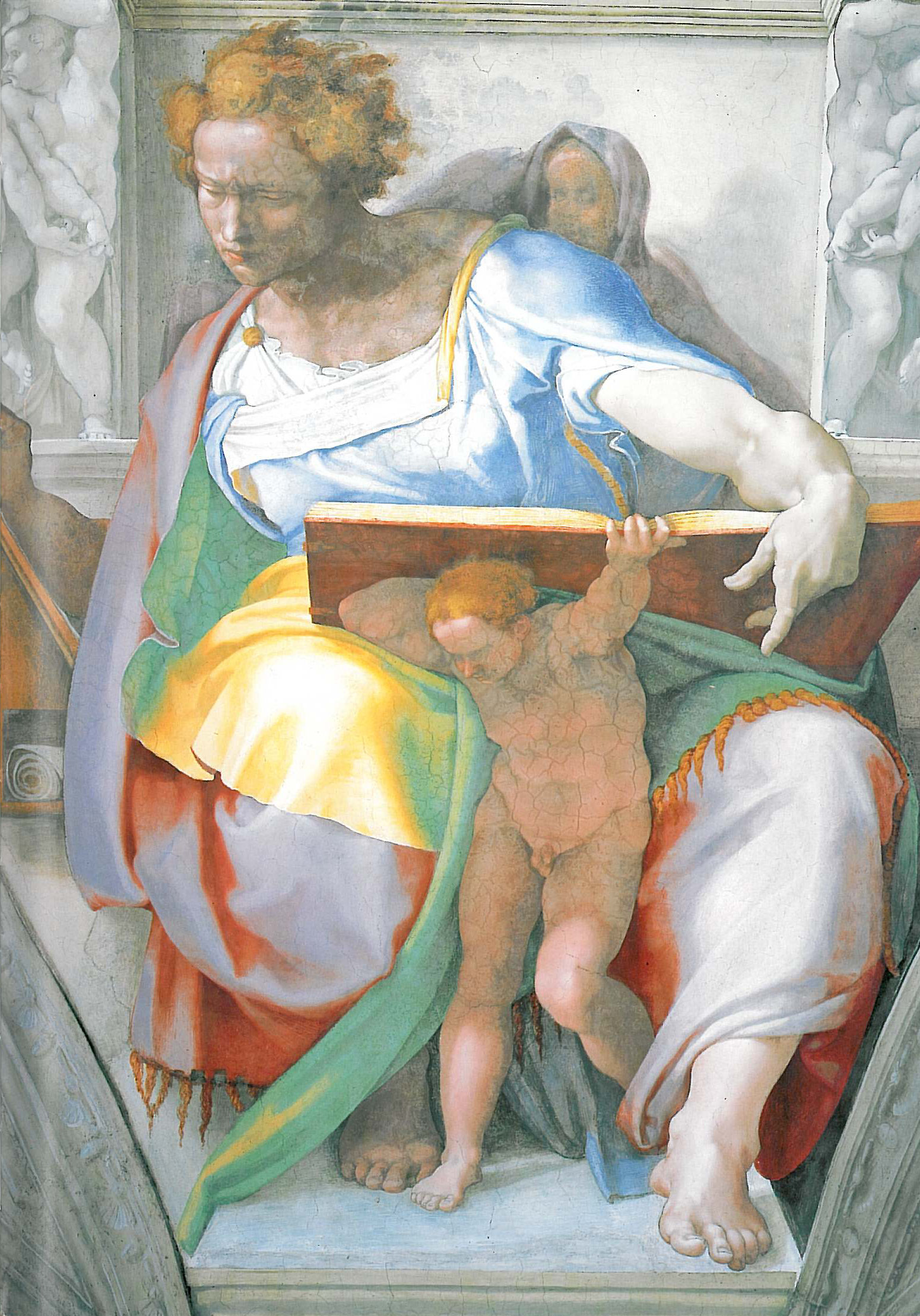

Daniel is on the north wall (the light falling from left to right). His knees are spread to support the enormous folio volume (which is wide open, unlike the Cumaean Sibyl’s book). He is helped in this task by one of his two attendant putti who is standing between his knees—a ‘hybrid’, so to speak, of the the infant Christ at Bruges and one of the marble telamons on the sides of the throne.

Daniel fills the space by throwing out his left arm, while his head looks in the other direction as he tries to capture the prophetic words which are being spoken by the other putto (who is almost concealed by his grey hood).

Her features are almost hidden by her oriental headdress and by the angle at which her head is presented. (But look at the wrinkles, the huge eyelid, the nose-tip, the toothless mouth and the pointed chin), as she peers short-sightedly (but clairvoyantly) into the tiny octavo volume (with just five lines of writing below the rubric).

Diagonally opposite her, looking down directly at the altar, is the most energetic of the sibyls—the Libyan.

She fills the width of her throne by twisting her body to take down the biggest volume of them all from the shelf behind her, forcing open her unlaced bodice as she does so, but exposing a quintessentially male back and shoulders, as we know from the preliminary drawing.

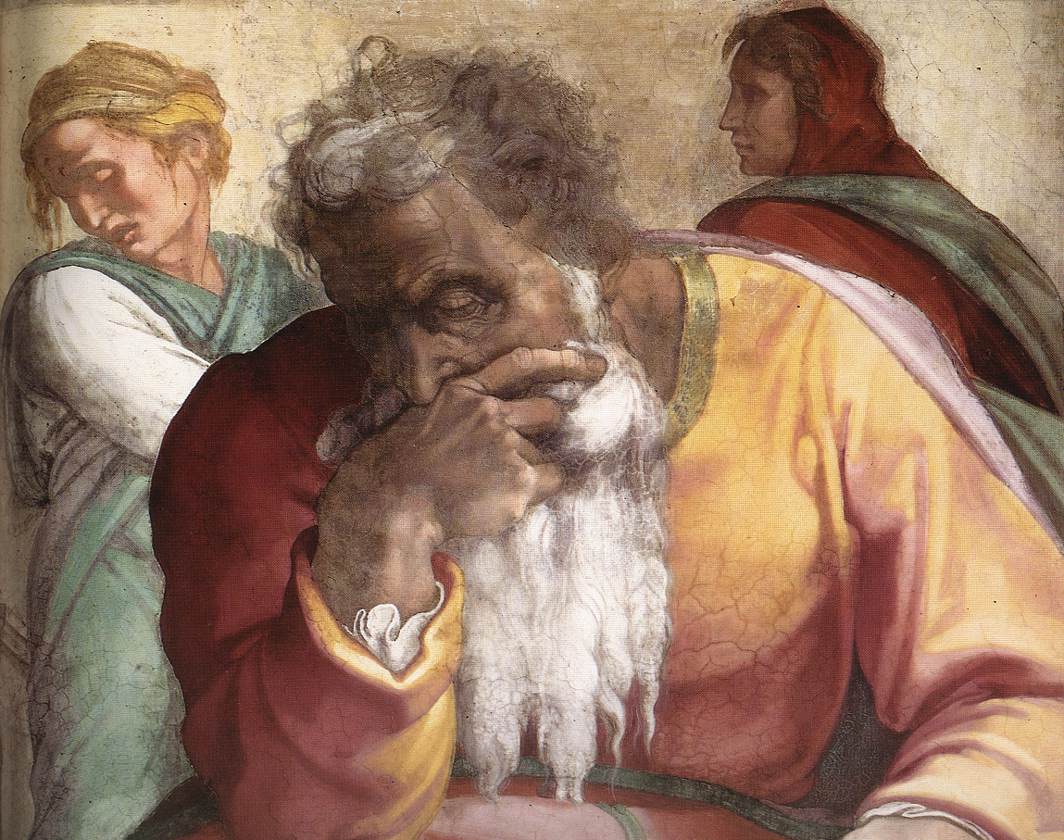

Our final image simply has to be the brooding figure of Jeremiah.

His throne is narrow, so he is sitting square on; his legs are crossed and his feet are tucked underneath him to push the knees wide. There is no book to read or replace. His left arm is limp, the hand relaxed. His right elbow rests on his knee, so that his huge hand (with two arthritic knuckles) may support his nose and cover his white-bearded mouth. He is looking not at the wall, nor at the altar, but down in our direction.

But of course, he does not see us at all, since he is lost in brooding contemplation of the Vision which found expression in the ‘Lamentations of Jeremiah’.

The detail offers a perfect way to bring this lecture to a close, because the features are half way between those of God the Father and an idealised self-portrait of the artist, as he would become when an old man.